www.rpped.com.br

REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Frequency

of

overweight

and

obesity

in

children

and

adolescents

with

autism

and

attention

deficit/hyperactivity

disorder

Arthur

Kummer

a,∗,

Izabela

Guimarães

Barbosa

a,

David

Henrique

Rodrigues

b,

Natália

Pessoa

Rocha

b,

Marianna

da

Silva

Rafael

b,

Larissa

Pfeilsticker

b,

Ana

Cristina

Simões

e

Silva

b,

Antônio

Lúcio

Teixeira

baFaculdadedeMedicina,UniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil bUniversidadeFederaldeJuizdeFora(UFJF),GovernadorValadares,MG,Brazil

Received12March2015;accepted16June2015 Availableonline28December2015

KEYWORDS

Attentiondeficitand hyperactivity disorder;

Austisticdisorder; Pediatricobesity; Overweight

Abstract

Objective: Toassessthefrequencyofoverweightandobesityinchildrenandadolescentswith autismspectrumdisorder(ASD)andwithattentiondeficit/hyperactivitydisorder(ADHD)and theirparents,incomparisonwithchildrenandadolescentswithoutdevelopmentaldisorders. Methods: Anthropometricmeasureswereobtainedin69outpatientswithASD(8.4±4.2years old), 23 with ADHD (8.5±2.4) and 19 controls without developmental disorders (8.6±2.9) between AugustandNovember2014. Parentsofpatientswith ASDandADHD alsohadtheir anthropometricparameterstaken.Overweightwasdefinedasapercentile≥85;obesityasa percentile≥95;andunderweightasapercentile≤5.Foradults,overweightwasdefinedasa BMIbetween25and30kg/m2andobesityasaBMIhigherthan30kg/m2.

Results: ChildrenandadolescentswithASDandADHDhadhigherBMIpercentile(p<0.01)and z-score(p<0.01)thancontrols,andincreasedfrequencyofoverweightandobesity(p=0.04). Patients withASD andADHD didnot differbetween them inthesevariables,norregarding abdominal circumference. Parents of children with ASD and ADHD did not differ between themselves.

Conclusions: ChildrenandadolescentswithASDandADHDareatahigherriskofoverweight andobesitythanchildrenwithoutdevelopmentalproblemsinthecommunity.

©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:r2kummer@hotmail.com(A.Kummer). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2015.12.006

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Transtornododéficit deatenc¸ãoe hiperatividade; Transtornoautístico; Obesidade

pediátrica; Sobrepeso

Frequênciadesobrepesoeobesidadeemcrianc¸aseadolescentescomautismoe transtornododéficitdeatenc¸ão/hiperatividade

Resumo

Objetivo: Avaliar a frequência de sobrepeso e obesidade em crianc¸as e adolescentescom transtorno doespectro doautismo (TEA)e transtorno dodéficit de atenc¸ão/hiperatividade (TDAH) e em seus pais, em comparac¸ão com crianc¸as e adolescentesda comunidade sem transtornosdodesenvolvimento.

Métodos: Medidasantropométricasforamcoletadasde69pacientescomTEA(8,4±4,2anos), 23 com TDAH (8,5±2,4) e19 controlessem transtornos desenvolvimentais(8,6±2,9)entre agostoe novembrode 2014.Ospaisdos pacientescomTEAeTDAH tambémforam avalia-dosemrelac¸ãoaosparâmetrosantropométricos.Sobrepesofoidefinidocomopercentil≥85; obesidadecomopercentil≥95;ebaixopesocomopercentil≤5.Paraosadultos,sobrepesofoi definidocomoIMCentre25e30kg/m2eobesidade,IMCacimade30kg/m2.

Resultados: Crianc¸as e adolescentes comTEA e TDAH exibirammaior percentil (p<0,01) e escore-z(p<0,01) doIMC em relac¸ão aoscontroles, bemcomo frequência maiselevada de sobrepesoeobesidade(p=0,04).OspacientescomTEAeTDHAnãodiferiramentresiquanto aessasvariáveisouquantoàcircunferênciaabdominal.Ospaisdascrianc¸ascomTEAeTDAH tambémnãodiferiramentresi.

Conclusões: Crianc¸aseadolescentescomTEAeTDAHestãoemmaiorriscodetersobrepesoe obesidadeemrelac¸ãoacrianc¸asdacomunidadesemproblemasdodesenvolvimento.

©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteéumartigo OpenAccesssobalicençaCCBY(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.pt).

Introduction

Prevalenceofoverweightandobesityindevelopedcountries isalarmingandreaches31.8%ofchildrenandadolescents.1

IntheUS,despitecontinuedeffortstoreducethesepublic

healthproblems,rateshavebeenstableinthelastdecade.1

InBrazil,epidemiologicalstudieshaveshownan increased

frequency of overweight and obesity in this age group.2,3

Comparison of the 1989 National Survey on Health and

Nutrition(PNSN)andthe2008---2009ConsumerExpenditure

Surveyshowsthatoverweightfrequencyinchildrenbetween

fiveandnineyearsoldincreasedfromabout9---33%.3

Internationalstudieshavefoundanassociationbetween

overweight/obesity and psychiatric disorders in children,

such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and

atten-tion deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Nevertheless,

whetherthisassociationischaracteristicofASDandADHDor

commontobehavioralanddevelopmentalproblemsin

gen-eralremainsunclear.Furthermore,theassociationislikely

tobe bidirectional;that is, not only behavioral problems

mayleadtoobesity,butobesitymaybeariskfactorforthe

developmentofbehavioralanddevelopmentalproblems.4

Moststudiesofthenutritionalstatusofyoungpeopleand

adultswithADHDreportsahighfrequencyofoverweightand

obesity,aswellasameanbodymassindex(BMI)higherin

patientswithADHDcomparedtocontrolswithout

develop-mentaldisorders.5---7 The frequency of obesity is higherin

adultswithADHD thanin adultswithchildhoodADHD

his-tory,butwhosesymptomsremittedinadulthood.8Similarly,

obeseyoungpeoplealsohave higherfrequencyof ADHD.5

Furthermore,behavioralproblemssuchasADHDhinder

obe-sitytreatment.9

Similarly,studiesalsoreportedthatchildrenand

adoles-centswithASDaremoreoftenoverweightandobese.10---13

In ASD, weight changes have been associated with sleep

disorders,10,11 older age,11 and using food as a reward,12

amongothers.Inaddition,parentsofchildrenwithautism

are also more frequently obese.14 These factors suggest

a complex interaction between genetic, molecular, and

behavioralfactors.

Despitethesealarmingdata,therearenostudiesofthe

nutritionalstatusofchildrenwithASDandADHDinBrazil.

Inaddition,fewstudieshavecomparedtheBMIand/orthe

overweightfrequencyindifferentdevelopmentaldisorders.

In this context, the aim of this study wasto evaluate

the frequency of overweight and obesity in children and

adolescentswithASDandADHDandtheirparents.

Method

Childrenandadolescents seenin theoutpatientclinics of ASD(n=69)andAttentionDeficit(n=23)ofthePsychiatry Ser-viceoftheHospitaldasClinicas,FederalUniversityofMinas Gerais(UFMG),Brazil,andtheirparentswereinvitedto par-ticipateinthisstudy.DatawerecollectedbetweenAugust andNovember2014,andnoneofthoseinviteddeclinedto participate.AllpatientswithASDandADHDmetthe diag-nostic criteriaof the DSM-5.15 It wasconsidered thegold

standard.PatientsinASDgrouphadnoADHDascomorbidity

andvice versa.Noteworthy,some patientswithASDwere

taking methylphenidate, but medicalrecords information

indicatedthatitsusewasfor‘‘disruptivebehavior’’’(e.g.,

heteroorself-aggressiveness).Thecontrolgroup(n=19)

development, recruited from the local community. The

study wasapproved bythe Research EthicsCommitteeof

UFMGandallparticipantsand/orlegalguardiansgavetheir

writteninformedconsentbeforeenteringthestudy.

Patientsandcontrolswereinterviewedusingastructured

questionnairetocollectdemographic(ageandsexofchild

andguardians) andclinical data.Parents ofchildren with

ASDresponded totheinventorySocialandCommunication

Disorders Checklist(SCDC)16 and parents of children with

ADHD respond to the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham scale

--- version IV(SNAP-IV).17 SCDC is a self-completion

ques-tionnaire with 12 questions that assesses the severity of

behaviorsrelatedtoautisminthelastsixmonths.16

SNAP-IVis aself-administeredinstrumentthat,in itsversionof

26 items, evaluates the severity of inattentive,

hyperac-tive/impulsive,andopponent/defiantbehavior.17

All subjects included in the study had their weight

(kg) and height (m) measured at the time of interview.

BMI was calculated using the formula: weight (expressed

in kg) divided by height (expressed in meters) squared

(kg/m2).Ageandsex-specificBMIz-scoreandpercentilesof

patientsandcontrolswerecalculatedusingCDC2000growth

charts.18Overweightwasdefinedasapercentile≥85;

obe-sity asa percentile≥95; andunderweightasa percentile

≤5.Foradults,overweightwasdefinedasBMIbetween25

and30kg/m2andobesityasBMIover30kg/m2.

Subjects werealsoevaluatedfor abdominal

circumfer-ence,whichwasalsoconvertedintopercentilesaccordingto

CDC 2007---2010 graphics.19 Anthropometricmeasurements

weretakenwithparticipantsinlightclothesandbarefoot,

using a portable digital scale, wall mounted stadiometer,

andinelastictapemeasure.Waistcircumferencewas

mea-suredovertheskinintheupperpartofthelateralborder

oftherightiliumandattheendofnormalexpiration,and

thenearestmillimeterwasrecorded.20

Statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS

soft-wareversion22.0(SPSSInc.,Chicago,IL,USA).Descriptive

statisticswere usedtopresent the sociodemographic and

clinicalcharacteristicsofthesample.Associationbetween

dichotomous variables was assessed with Pearson’s

chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous

variables were expressed as mean and standard

devia-tion.Allvariablesweretestedfornormaldistributionusing

the Shapiro---Wilk test and no data had a normal

distri-bution. Therefore, the differences between groups were

compared using the Mann---Whitney test or Kruskal---Wallis

test, asappropriate.Correlations were investigatedusing

theSpearmancoefficient.Allp-valuesweretwo-tailedand

thesignificancelevelofp<0.05wasused.

Results

There was prevalence of male in the ASD (86.9%), ADHD (78.9%),and control (86.9%) groups. There wasno statis-ticallysignificantdifferencebetweengroups(p=0.66).Also, therewasnodifferenceinagebetweenindividualswithASD (8.4±4.2;range:2---18years),ADHD(8.5±2.4;range:5---15 years),andcontrols(8.6±2.9;range:5---15years)(p=0.603). Ageandsex-specificBMIz-scoreandpercentilesof con-trolsweresignificantlylowerthanthoseofpatientswithASD andADHD(Table1).Similarfindingswereseenwhengroups

werecomparedregardingweightchangeproportions,with

higherpercentageofoverweightandobesityinbothgroups

ofpatients(ASDandADHD)comparedwiththecontrolgroup

(Table1).On theotherhand,therewasnosignificant

dif-ferencebetweenpatientswithADHDandASDinanyofthe

comparisons(Table1).Regardingwaistcircumference

per-centile,groupswithASD(56.4±29.9)andADHD(65.0±18.3)

alsodidnotdiffer(p=0.453).

The severity of ADS symptoms did not correlate with

anthropometric measurements (Table 2). In ADHD group,

the BMI percentile correlated negatively with the

sever-ityof oppositionanddefiance symptomsofandtherewas

nocorrelationwithinattentionorhyperactivity/impulsivity

symptoms.

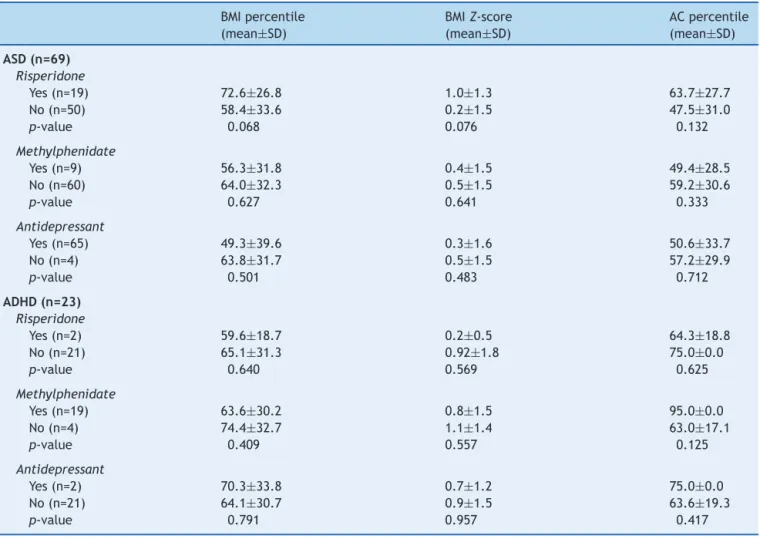

OfADHDpatients,20(87%)weretakingpsychiatricdrugs

(Table3).AmongASDpatients,26(37.7%)weretaking

psy-chiatric drugs. In ASD group, therewas a tendency for a

higher percentage of BMI (p=0.06) in participants taking

risperidone. Of the 21 participants taking risperidone, 5

(23.8%)ofguardiansspontaneouslyreportedseen a

signifi-cantincreaseinappetiteafterdruginitiation.Ofthetotal

28participantsinuseofmethylphenidate,whenfacedwith

anopenquestiononsideeffects,13(44.8%)guardians

spon-taneouslyreportedthattherewasasignificantdecreasein

appetitewiththedrug.

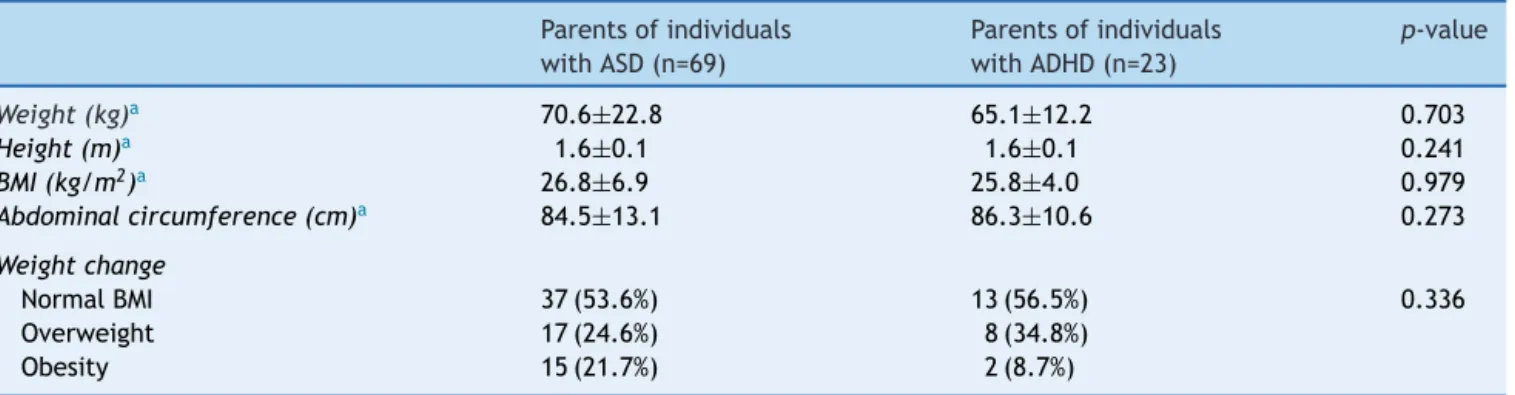

Parentsofparticipants withASDandADHD didnot

dif-ferwithrespecttoanthropometricmeasurements(Table4).

Therewas also nosignificant difference between parents

of individuals with ASDand ADHD regarding frequency of

overweightandobesity(p=0.34).

Table1 Comparisonofbody massindex(BMI) andweightchangebetween individualswithattentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder(ADHD)andautismspectrumdisorder(ASD)andcontrols.

Controls(n=19) ADHD(n=23) ASD(n=69) p-value

BMIpercentilea 35.8±28.5 64.6±30.2 62.9±32.0 0.006

BMIZ-scorea −0.55±1.13 0.87±1.42 0.49±1.51 0.002

Weightchanges 0.044

Underweight 21.0% 0.00% 6.7%

Normal 73.7% 65.2% 53.3%

Overweight 0.00% 17.5% 18.3%

Obesity 5.3% 17.4% 21.7%

BMI,bodymassindex.Boldindicatesp-valuesignificantat<0.05.

Table2 Correlationofclinicalfeatureswithbodymassindex(BMI)andwaistcircumferenceinindividualswithautismspectrum disorder(ASD)andattentiondeficit/hyperactivitydisorder(ADHD).

BMIpercentile BMIZ-score ACpercentile

ASD(n=69)

SCDC

Correlationcoefficient 0.059 0.062 −0.009

Sig.(2tailed) 0.727 0.717 0.960

ADHD(n=23)

SNAP-I

Correlationcoefficient −0.200 −0.251 −0.667

Sig.(2tailed) 0.555 0.457 0.219

SNAP-HI

Correlationcoefficient −0.230 −0.331 0.803

Sig.(2tailed) 0.496 0.320 0.102

SNAP-OD

Correlationcoefficient −0.621 −0.370 0.410

Sig.(2tailed) 0.041 0.263 0.493

AC,abdominalcircumference;SCDC,Social andCommunicationDisordersChecklist; SNAP-I,SNAP-IVinattentionsubscale; SNAP-HI, SNAP-IVhyperactivitysubscale;SNAP-OD,SNAP-IVoppositionanddefiancesubscale.Boldindicatesp-valuesignificantat<0.05.

Table3 Analysis ofassociationsbetween druguse andbody massindex(BMI)andwaistcircumferenceinindividualswith autismspectrumdisorder(ASD)andattentiondeficit/hyperactivitydisorder(ADHD).

BMIpercentile (mean±SD)

BMIZ-score (mean±SD)

ACpercentile (mean±SD)

ASD(n=69)

Risperidone

Yes(n=19) 72.6±26.8 1.0±1.3 63.7±27.7

No(n=50) 58.4±33.6 0.2±1.5 47.5±31.0

p-value 0.068 0.076 0.132

Methylphenidate

Yes(n=9) 56.3±31.8 0.4±1.5 49.4±28.5

No(n=60) 64.0±32.3 0.5±1.5 59.2±30.6

p-value 0.627 0.641 0.333

Antidepressant

Yes(n=65) 49.3±39.6 0.3±1.6 50.6±33.7

No(n=4) 63.8±31.7 0.5±1.5 57.2±29.9

p-value 0.501 0.483 0.712

ADHD(n=23)

Risperidone

Yes(n=2) 59.6±18.7 0.2±0.5 64.3±18.8

No(n=21) 65.1±31.3 0.92±1.8 75.0±0.0

p-value 0.640 0.569 0.625

Methylphenidate

Yes(n=19) 63.6±30.2 0.8±1.5 95.0±0.0

No(n=4) 74.4±32.7 1.1±1.4 63.0±17.1

p-value 0.409 0.557 0.125

Antidepressant

Yes(n=2) 70.3±33.8 0.7±1.2 75.0±0.0

No(n=21) 64.1±30.7 0.9±1.5 63.6±19.3

p-value 0.791 0.957 0.417

Table4 Anthropometricdata andfrequencyofweightchangeofparentsofindividualswithattentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder(ADHD)andautismspectrumdisorder(ASD).

Parentsofindividuals withASD(n=69)

Parentsofindividuals withADHD(n=23)

p-value

Weight(kg)a 70.6±22.8 65.1±12.2 0.703

Height(m)a 1.6±0.1 1.6±0.1 0.241

BMI(kg/m2)a 26.8±6.9 25.8±4.0 0.979

Abdominalcircumference(cm)a 84.5±13.1 86.3±10.6 0.273

Weightchange

NormalBMI 37(53.6%) 13(56.5%) 0.336

Overweight 17(24.6%) 8(34.8%)

Obesity 15(21.7%) 2(8.7%)

BMI,bodymassindex.

a Valuesareexpressedasmean±standarddeviation.

Discussion

Overweightandobesity arepublichealth problems in the generalpopulation.Theincidenceofmanychronicdiseases inadulthoodisdirectlyrelatedtochildhoodobesity.1

Obe-sity increases the risk of children having short and long

termhealthproblems,suchasdiabetes,cardiovascularand

psychosocial diseases. International studies indicate that

childrenandadolescentswithASDandADHDmaybe

particu-larlyvulnerabletosuchweightchanges.4---13Thisworkshows

thatBrazilianchildrenandadolescentswithASDandADHD

also appear tobe more proneto overweight and obesity

comparedtothegeneralpopulation.

Few Brazilian studies have investigated this issue.

Domingues evaluated 30 children in a special school of

CampoGrandeandfoundthatfour(13.3%)wereobeseand

seven(23.3%)wereunderweight.21Emidioetal.evaluated

23 autisticchildren andadolescentsand foundthat three

(13%)wereunderweight,five(21.7%)wereoverweight,and

six(26.1%)wereobse.22Althoughbothstudiesindicatehigh

ratesofoverweightandobesityinchildrenandadolescents

withASD,theabsenceofacontrolgroupsignificantlylimited

theinterpretationofthefindings.

Nascimento et al.found nodifferencein frequency of

overweight amongchildren andadolescents with

‘‘ADHD-indicative’’ and controls, or when comparing the BMI of

boththegroups.23Alimitationofthisstudyistheinclusion

of children with only ‘‘ADHD-indicative’’, without a

con-firmeddiagnosisofthedisorder.Moreover,thestudydidnot

properlysetthevariable‘‘overweight’’,aswellasdirectly

compared theBMI of the two groups, instead of

compar-ingthe adjusted percentilefor age.In contrast,Paranhos

et al. reported that all 70 children and adolescents with

ADHDevaluatedattheUniversityHospitalofBrasiliawere

eutrophic.24 However, this study also did not adequately

definedtheweightchange and didnotusethe percentile

variableand/ortheageandsex-specificBMIz-scores.

TherearefewpublishedstudiesthatcomparedBMIand

frequency of overweight/obesity between developmental

disorders. Curtin et al. performed a review of medical

records of children and adolescents in care in a tertiary

centerforneuropsychiatricdisordersandfoundafrequency

ofoverweight andobesity of,respectively, 29%and17.3%

in ADHD patients and 35.7% and 19% in ASD patients.25

The Curtin study limitation is that anthropometric

mea-surementswereobtainedfrommedicalrecords,therewas

no standardization in the form of data collection.

More-over,therewasnocontrol groupor comparisons between

groups. Chenet al.evaluated only thefrequency of

obe-sity (BMI ≥95th percentile) in children and adolescents

withchronicdesases(physical,developmental,and

behav-ioral) and found frequency of 23.4% in ASD patients and

18.9% in ADHD patients.26 The study by Chen et al. also

hasa number of limitations, such asusing data fromthe

NationalSurveyofChildren’sHealth(NSCH2003),inwhich

allinformationwascollectedbytelephone;thepossibility

ofhavingthesameparticipantwithcomorbiditiesincluding

ASDandADHDatthesametime;andnostatistical

calcula-tionforcomparisonbetweengroups.Morerecently,Philips

etal. useddata fromthe National Health Interview

Sur-vey(2008---2010)tocomparethefrequencyofunderweight,

overweight,andobesityinadolescentswithvarious

devel-opmentaldisorders.13 Obesityandunderweight weremore

commonin allneurodevelopmentaldisorders,but the

fre-quency of obesity was particularly high in the subgroup

withASD(31.8%),whereaspatientswithADHDhadalower

prevalence(17.6%).Thefrequencyofoverweightwas

simi-larbetweenthegroupswithdevelopmentaldisorders(ASD:

20.9%;ADHD:18.0%)andchildrenwithtypicaldevelopment

(18.2%).Thestudyshouldalsobeinterpretedwithcaution

becauseofitslimitations,includingthemedicaland

anthro-pometricdatacollectiononlybyinterviewingtheguardians;

non-pairingbysexbetweenthecontrolandASDandADHD

groups,therewasprevalenceoffemaleadolescentsinthe

control group13; and the high frequency of comorbidities

between ASD and ADHD (60% of ASD patients also had

ADHD).

Acommonlimitationofmanystudiesofweightchanges

inpeoplewithASDandADHDis thattheauthors useonly

theBMIasbase.Suchanapproachdoesnotallowthedirect

measurement of body composition and/or distribution of

bodyfat,theremaybeincreasedBMIbecauseofincreased

musclemass.Waistcircumferencemeasurementiseasy to

obtainandcanindicatethe presenceofvisceral adiposity

inchildren.27Inthiscontext,thepresentstudyshowedthat

groupswithASDandADHDdidnotdifferfromeachotheror

inrelationtoBMI(highcomparedtocontrol)norinrelation

TheseverityofASDandADHDsymptomsdidnot

corre-latewithweightchange.However,oppositionanddefiance

symptomsnegativelycorrelatedwithBMIpercentileinADHD

participants. Korczak et al. noted that ADHD could

pre-dictobesitylaterinlife,butaccordingtotheauthorsthis

associationwouldbecompletelyexplainedbythepresence

of behavior disorder in childhood.28 Although

opposition-defianceandbehaviorsymptomsareoftencorrelated,this

seeminglydiscrepantfindingraisesthequestionofwhether

these conditions may have differential effect on feeding

behavior(e.g.,refusaltoeatandfrequenttantrumsrelated

tofoodintheopponent-defiantdisorder).

Consistent with the medical literature, there was a

trend towards the association of risperidone intake and

higherBMI percentile in ASD patients. Increasedappetite

and metabolic alterations are common side effects of

risperidone.20Interestingly,althoughtheparentsofchildren

takingmethylphenidatehave reporteddecreasedappetite

withthissubstance,thiswasnotreflectedinlowerBMIin

ADHDchildren. Itwasnotpossible tocomparethe BMIof

ADHDchildrentakingornottakingmethylphenidatebecause

almostallofthemweretakingthisdrug.However,although

methylphenidatecommonsideeffectisdecreasedappetite,

otherstudieshavefoundnodifferenceinBMIbetweenADHD

childrenreceivingornotmethylphenidate.6,7

Finally,itwasseenforthefirsttimeintheliteraturethat

parentsofchildrenwithASDandADHDdidnotdifferinBMI,

waistcircumference,andfrequencyofoverweight/obesity.

Although nearly half of parents are overweight/obese,

unfortunatelyitwasnotpossibletocomparethemwiththe

controlgroupbecausethechildrenandadolescentsofthe

controlgroup were examined at school without the

pres-ence of their parents. Some studies suggest that obesity

in parents is a risk factor for ASD and ADHD. However,

more investigations are needed to assess factors

under-lyingthis possible association, suchasgenetic/epigenetic

influence, family habits, inflammatory changes resulting

fromobesity duringgametogenesis and pregnancy, among

others.14,29

Theseresultsshouldbeinterpretedwithcaution.Dueto

itscross-cuttingnature,onecannotinfercausalitybetween

ASD,ADHD,andhigherfrequencyofoverweightandobesity.

Furthermore,thisstudyincluded arelativelysmall

conve-niencesampleof ADHDpatientsandcontrols. Allpatients

were recruited froma singletertiary center where more

complexcaseswithmorepronouncedsymptomsofADHDand

ASDareusuallytreated,whichcouldcompromisethe

exter-nalvalidityofthestudy.Moreover,therewereasignificant

proportion of underweight children in the control group,

which highlighted a peculiarity of the sample involved in

this work. The lack of waist circumference measurement

in the controls and anthropometricmeasurement in their

parentsis alsoa limitation thatshould bementioned. On

the other hand, consecutive sampling, direct and careful

measurementofanthropometricparametersofpatientsand

communitycontrolswithoutdevelopmentaldisorders,

diag-nosisandevaluationofpatientsbyexperiencedclinicians,

sample matched bygender and age, andthe exclusionof

comorbidcasesofADHDandASDarestrengthsofthestudy

thatshouldbehighlighted.

Insummary,thisstudyshowedthatchildrenand

adoles-centswithASDandADHDfollowed-upinoutpatientclinics

areat increasedriskof overweightandobesitythan their

typicallydeveloping peers. Drugssuch asrisperidonemay

havesomecausalroleandpatientstakingthesesubstances

requireclose monitoringfor metabolic changes.However,

geneticandenvironmentalfactors(e.g.,pooreatinghabits

and sedentary lifestyle) should also be considered. We

emphasizethatobesityandoverweightaregeneralrisk

fac-torsfordisordersandresponsibleforworseningthequality

oflife.Thus,itisveryimportantthatphysiciansroutinely

assesstheweightoftheirpatientswithASDandADHDand

givethemadvisesonhealthylivinghabits.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brasil - 304272/2012-4), Fundac¸ão de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (Fapemig, Brasil - APQ-04625-10), and Coordenac¸ão de Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes, Brasil).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

Dr.IGBarbosareceivedpostdoctoralscholarshipfromCapes (Capes/DBP/CEX/PNPDNo.2039-58/2013).

References

1.OgdenCL,CarrollMD,KitBK,FlegalKM.Prevalenceof child-hoodandadultobesityintheUnitedStates,2011---2012.JAMA. 2014;311:806---14.

2.FloresLS,GayaAR,PetersenRD,GayaA.Trendsofunderweight, overweight,andobesityinBrazilianchildrenandadolescents. JPediatr(RioJ).2013;89:456---61.

3.PimentaTA,RochaR.AobesidadeinfantilnoBrasil:umestudo comparativoentreaPNSN/1989eaPOF/2008-09entrecrianc¸as de5 a9anos deidade.FIEPBull Online.2012;82.Available from: http://www.fiepbulletin.net/index.php/fiepbulletin/ article/view/2224[accessed02.04.15].

4.Khalife N, Kantomaa M, Glover V, Tammelin T, Laitinen J, EbelingH,etal.Childhoodattention-deficit/hyperactivity dis-order symptoms are risk factors for obesity and physical inactivityinadolescence.JAmAcadChildAdolescPsychiatry. 2014;53:425---36.

5.Cortese S, Vincenzi B. Obesity and ADHD: clinicaland neu-robiological implications. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;9: 199---218.

6.Holtkamp K, Konrad K, Müller B, Heussen N, Herpertz S, Herpertz-DahlmannB,et al.Overweight and obesity in chil-drenwithattention-deficit/hyperactivitydisorder.IntJObes RelatMetabDisord.2004;28:685---9.

7.FliersEA,BuitelaarJK,MarasA,BulK,HöhleE,FaraoneSV, etal.ADHDisariskfactorforoverweightandobesityin chil-dren.JDevBehavPediatr.2013;34:566---74.

9.Cortese S, Castellanos FX. The relationship between ADHD and obesity:implications for therapy. ExpertRev Neurother. 2014;14:473---9.

10.ZuckermanKE,HillAP,GuionK,VoltolinaL,FombonneE. Over-weightandobesity:prevalenceandcorrelatesinalargeclinical sampleofchildrenwithautismspectrumdisorder.JAutismDev Disord.2014;44:1708---19.

11.Broder-Fingert S, Brazauskas K, Lindgren K, Iannuzzi D, Van Cleave J. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in a large clinicalsample of children withautism. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:408---14.

12.BandiniL,CurtinC,AndersonS,Philips S,MustA. Foodasa rewardand weight statusin children with autism. FASEBJ. 2013;27:1063---111.

13.PhillipsKL, SchieveLA, VisserS,BouletS,Sharma AJ,Kogan MD, et al. Prevalence and impact of unhealthy weight in a national sampleof US adolescents withautism and other learning and behavioral disabilities. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1964---75.

14.SurénP,GunnesN,Roth C,BresnahanM,HornigM,Hirtz D, etal.Parentalobesity and riskofautismspectrumdisorder. Pediatrics.2014;133:e1128---38.

15.AmericanPsychiatricAssociation.ManualDiagnósticoe Estatís-tico de Transtornos Mentais. 5th ed. (DSM-5) Porto Alegre: ArtmedEditora;2014.

16.SkuseDH,MandyWP,ScourfieldJ.Measuringautistictraits: heri-tability,reliability,andvalidityoftheSocialandCommunication DisordersChecklist.BrJPsychiatry.2005;187:568---72. 17.MattosP,Serra-PinheiroMA,RohdeLA,PintoD.Apresentac¸ão

deumaversãoemportuguêsparausonoBrasildoinstrumento MTA-SNAP-IVdeavaliac¸ãodesintomasdetranstornododéficit deatenc¸ão/hiperatividadeesintomasdetranstornodesafiador edeoposic¸ão.RevPsiquiatrRS.2006;28:290---7.

18.KuczmarskiRJ,OgdenCL,GuoSS,Grummar-StrawnLM,Flegal KM,MeiZ,etal.2000CDCgrowthchartsfortheUnitedStates: methodsanddevelopmentNationalCenterforHealthStatistics. VitalHealthStat.2002;11:1---19.

19.FryarCD,GuQ,OgdenCL.Anthropometricreferencedatafor childrenandadults:UnitedStates,2007---2010NationalCenter forHealthStatistics.VitalHealthStat.2012;22:11.

20.NationalHealth.NutritionExaminationSurvey.Anthropometry proceduresmanual.Atlanta:CDC;2007.

21.Domingues G. Relac¸ão entre medicamentos e ganho de peso em indivíduos portadores de autismo e outras sín-dromes relacionadas. Mato Grosso do Sul: Nutric¸ão Ativa; 2007.

22.Emidio PP, FagundesGE, Barchinski MC, Silva MA. Avaliac¸ão nutricional em portadores da síndrome autística. Nutrire. 2009;34:382.

23.Nascimento EM, Contreira AR, Silva EV, Souza LP, Beltrame TS.Desempenhomotoreestadonutricionalemescolarescom transtorno do déficit de atenc¸ão e hiperatividade. J Hum GrowthDev.2013;23:1---7.

24.ParanhosCN,AucelioCN,SilvaLC,PigossiM,VieiraNC,Silva TL, et al. Transtornode déficitde atenc¸ãoe hiperatividade (TDAH)---A avaliac¸ãodopadrãonoEEGeestadonutricional de crianc¸as eadolescentes de Brasília/DF. Pediatr Moderna. 2013;49:227---31.

25.CurtinC,BandiniLG,PerrinEC,TyborDJ,MustA.Prevalence ofoverweightinchildrenandadolescentswithattentiondeficit hyperactivitydisorderandautismspectrumdisorders:achart review.BMCPediatr.2005;5:48.

26.ChenAY,KimSE,Houtrow AJ,NewacheckPW. Prevalenceof obesityamongchildrenwithchronicconditions.Obesity(Silver Spring).2010;18:210---3.

27.Mantovani RM, Rios DR, Moura LC, Oliveira JM, Carvalho FF, Cunha SB, et al. Childhood obesity: evidence of an association between plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels and visceral adiposity. JPediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24: 361---7.

28.Korczak DJ,LipmanE,Morrison K,Duku E,SzatmariP.Child andadolescentpsychopathologypredictsincreasedadultbody massindex: resultsfrom aprospective communitysample.J DevBehavPediatr.2014;35:108---17.