Universidade

de

Évora

X'actores

ambientais

que

afectam

a

riqueza

especíÍica

de

macrofungos

em montados de

azinho

-

Implicações

para

a

Gestão

e

Conseruação

ffi

t a\ { ', J'Rogério Filipe Agostinho

Louro

Dissertação apresentada para a obtenção do grau de mestre em

Biologia da Conseruação

Orientador: Prof.u

Dr.'

Celeste Santos-Silvaffi

-{

Évora

r20l0

ffi

E

7 ,à 'ltl''lUniversidade

de lÚvora

Factores ambientais

que afectam

a

riqueza

especÍÍica

de

macrofungos

em

montados

de azinho

-

Implicações

para

a

Gestão

e

Conservação

Rogério

Filipe

Agostinho

Louro

Dlssertação apresentada para a obtenção do grau de mestre em Biologia da Conseruaçâo

Orientador: Profl" Dn" Celeste Santos-Silva

{ts

6;3

AGRADECIMENTOS

A

realização desta dissertação não teria sido possível sem a intervenção das seguintes pessoasàs quais estou eternarnente agradecido:

Agradeço

à

miúa

orientadoraProf."

Dr."

Celeste Santos-Silva pelasvaliosas

sugestões e correcções,bem como

por todo o

tempo,

esforço,apoio

e

dedicaçãoque ao

longo

deste trabalhofoi

demonstrando.Agradeço ao Prof.

Dr.

RussellAlpizar

Jara peloterrpo

e esforço que dedicou na revisão deste trabalho e pelas úteis sugestões acerca do tratame, to estatístico dos dados.Agradeço à Doutora Isabel Santos-Silva a pronta revisão deste

tabalho.

Agradeço à

EDIA

-

Empresa para o desenvolvimento de infra-estruturas do Alqueva-

porter

permitido e financiado este estudo.

Agradeço

à

Maria da Lrrz

Calado

pela valiosa ajuda

durante

o

processo

moroso

de amostragem.Agradeço

ao meu

innão

e à

minha

mãepor todo

o

apoio, paciênciae

incentivo que

meprestaram ao longo deste trabalho.

Agradeço aos meus amigos a paci&rcia e apoio qlre me deram.

Por

fim,

gostaria de agradecer a todas as pessoasaqui

não mencionadas mas que de algumÍrorcr

Acnepecnagl.ITos.Rssuuo

AgsTRAct

INTRODUÇÃoI

1I

2 3 4 OBJECTTVOS.BTOTTC AND ABIOTIC FACTORS AEFECTING MACROF1JNGAL RICHNESS IN HOLM OAK STA}IDS OF

SounrrnxPonrucer,

..

6AssmAcr

6INrnonucnoN

6MersRIALs AND

MBUrO»S.

9Rrsur,rs...

12DrscussroN

16AcrNowr.nocMENTs...

l7

ÁnnaoB EsruDo....

LmrnerunrCrreo.

RrrBnÊucns

emlIocRÁFrces...

Auexo

18 23 24 26tr

FactoÍ€s ambieotais que afecüm ariqueza ospecífca de macroflmgoa

X'actores ambientais que afectam

I

riqueza espocíÍics de macrofungos em montados de azinho -Implicações para a Gestão e ConservaçãoRESI'MO

Ariqrcza

específica de macrofungos e os mecanismos natuÍais que a influe,nciam são aindapouco coúecidos. Foram utilizados

modelos

de

regressãolinear para

inferir

a

relação existenteente

a riqueza de macrofungos e diversas variáveis ambie,ntais.De Novembro

de2005 a

Abril

de 2007foram

amosffidas me,lrsalmelrte as espécies de macrofimgos presentesem

montadosde

azinho

(Qtercus rotundifolia Lam.) no

Parquede Natureza de

Noudar(Alentejo,

Portugal).Verificou-se que

a

riqueza

de

espéciesmicorrízicas

aume,ntacom

a classee*ia

das árvorese com

a penceirtage,m de coberto arbustivo, enquantoa

riqueza de espécies sapróbias aumentacom

as percentagens de cobertos arbustivo e herbáceo, sendo ocoberto arbustivo relevante

para

ambosos

grupos

üóficos. Pelo

exposto

anteriormente,propomos que sejam mantidas faixas e pequenas manchas de vegetação arbustiva natural e

que o

contolo

de matos seja efechrado deforrra

a manter intocada a rizosfera, manimizandodesta forma a riqueza de macrofimgos.

Palawas-chave:

iqrrcza

específica de macrofimgos, regressÍlo linear, perce,ntagemde

cobertura arbustiva, montados de azinho, Portugal.Environmental factors affec'ting macrofungal richness in holm oakstands

-

Implicationsfor

Managemenú and Conservation

ABSTRACT

Macrofimgal rictrness

is

still

poorly known and

the

natural

meçhanisms

enhancingmacrofungal

diversity

still

remain

rmclear.We

usedlinear

regressionmodels

to

infEr

therelationship between mushroom richness

and

several environme,ntal variables. Thenofore, amacrofungal inventorybased on

fruit

bodies was conduckd monthly, from November 2005to

Apnl

200?,in holm

oak

stands (Quercusrotundifulia

l^am.) onthe

Parque de Natureza deNoudar (Ale,ntej o, Portugal).

According

to

our results,mycorrhizal

richness increaseswith

nee age class and shnrb cov€tr,while

saprohophicrichness

increaseswith

shrub cover

and hçrbaceouscovetr Although,

mycorúizal and saprorophic

riúness

models

üffered

ftom

eachother,

results

seernto

emphasize

trat

úrubs

areof

tlre

upmost importancefor

bothmycorúizal

and saprotrophic maorofiurgiin

holm

oak stands. Thuswe

proposethat

strips and patchesof

natural

shrubbyvegetation

úould

be maintained and shnrb control methodsúouldkeep

the rhizosphere intactin

orderto

enhance macrofungal richness.,

FactoÍ$ amblentais çe afectam ariçeza específica de macoofimgooINTRODUÇÃO

A

necessidade de protegere

conservar a biodiversidadee

os recursosnatrais

temvindo

aassumir

um

papel

de

destaque,uma

prioridade

e

uma

preocupação generalizada nacomunidade

científiça"

face às

constantes ameaçase

impactos

negativos

inerentes

àinsustentabilidade dos padrões de consumo

e

alteragões arnbientais que resultam directa ouindirectame,nte do aumento da população humana (RSPB 2003). Há

muito

que a maioria dosestudos

e

actividades relacionadas

com

a

protecção

da

Natureza

e

conservação daBiodiversidade incidern quase exclusivarne,nte sobre as comunidades faunísticas e florísticas,

menosprezando

a import&roia,

rJrqrezae

diversidade do micobiota,bem

como dos factoresque ameaçarn as comrmidades

micológicas.

Ditosamente, esta tendência estáa

inverter-se, tendo-se registado nas últimas décadasum

orescente interesse pelo recurso micológico,factor

que

tem

atraído

mais

investigadorespara esta

áreae

conseque,nteme,ntepromovido

arealização

de mais

estudos sobretaxonomiq

distribúção, biologia

e

ecologiados

firngos.Contudo, diversas entidades empenhadas

na

conservação domicobiota,

de queo

EuropeanCouncil

for

the Conservation ofFungi

é exemplo, continuama

alertar paru a necessidade de aumentaro

conhecimento da diversidade micológica, nomeadamerrte afuavés de"checklists"

locais, estudos prolongados e elaboração de *Red

Lists",

eÍl

particular nos países onde afalta

de estudos base é evidente (p. ex. Albânia, Grécia e Portugal) (Senn-hlet et a12007).

Importa ainda considerar a gestão do habitat oomo uma ferramenta esse,ncial no delineame,nto

de

estratégias paraa

conservação dos recursos micológicos(Molina et al

2001).

SegundoAmold

(2001), a conservação insitu

das comrmidades micológicas deverá passar emprimeiro

lugarpela

conseroaçãoe

gestâo adequada dos seus habitats.No

entanto,no

nosso País, a inclusão do micobiota em planos de conservação está ainda longe de se tornar uma realidade.É

reconhecido o papelfulqal

que osfiingos

desempenham aonível

do

eqúlíbrio

da cadeiatrófica

de

vários

ecossistemas,assegurando

a

reciclagern

da

matéria org&rica

edisponibilizando

nutrientespara as

espécies vegetais existentes (sapróbios),eliminando

asespécies vegetais me,nos saudáveis (parasitas), favorece,lrdo o crescimento e desenvolvime,nto

de

várias

espéciesvegetais,

na

medida

em

que lhes fomecem

nutrie,ntes essenciais(principalmente fósforo

e

azoto)e ágw

e as protegem de agentes patogénicos (micorrízicos)(Alexopoulos

andMims

1979,Smith

and

Read 2008). Paraalém

do

seu relevantç papelecológico,

muitos

dessesfungos produzem

estnrturas reprodutoras-

cogumelos-

múto

apreciadas

pelo

seuvalor

gastronómicoe

actualmente consideradoscomo

um

importanteÍecurso florestal

não-lenhoso. Seno

passado,a

colheita de

cogumelos representava umaFac'toee ambientaisque aftotam a riqueza específica de oacrofungoo

actiüdade

oultural$taizafu,

e umavaliosa

fonte de rendim€,nto apems para as populações locais(Arnold

2008, Garibay-Orijel etal

z}Og),hoje em dia caberá também aos proprietários gerir sustentavelmente este Íecurso, como preüsto no Código Florestal(MADRP

2009).Em Portugal,

o

conhecimento sobre a ecologia e diversidade dos macrofungos está longe deigualar

a

informação

existe,ntesobre

a

flora

e

fauna

com que

interage

e coúita.

Este desconhecimento deriva, em grande medida, das particularidades do método de estudo destes organismos: precariedade das fruüficações (órgão mais fiável para uma idenüficação segtra), sazonalidadecom que fiutificam,

complexidade

no

recoúecimento das

espéciese

nataxonomia de

alguns grupos,tudo isto

agravadopelo

insuficiente númerode

micologistas (Moore etaI2001).

A

necessidade decoúecer

as comunidades de macrofiingos,bem

como os factores que asafectam

positiva

ou negativame,nte évital,

pois este grupobiológico

esüí sujeito a umaforte

pressão humana, motivada pela colheita das suas esüuturas reprodutoras (cogumelos).

Sabe-se que são inrlrreros os frctores

bióticos

e abióticos que influenciam a presença efrutificação

dos maçrofungos. Cada

um

desses factores revela-se mais ou menos importante depende,ndo das características das especies e dos grupostróficos

a que pertencem. Os factores climáticosa

pm

de outros agentes abióticos, nomeadamente, edáficos(tipo

de solo,pH,

teor de matériaorgânica)

e

geomorfológicos

(altitude,

exposição, inclinaçãodo

terreno), condicionam

apresença e a produtividade dos macnofungos (Villeneuve et

al

1989, Brunner etal l992,Baar

1996,l-aganà et

al

1999, Kernaghan and Harper 2001, Kranabetter and Kroeger 2001, Bonetet

al

2004).

Vários

autores defendem

a

exist&tcia

de

uma

forte

correlação

enhe

ascomunidades de macrofungos e a composição e estrutura das comunidades vegetais (Laganà

etal

1999, Bonetetal2004,Richard

etaTzüM,Kernaghan

etaI2003).

Outros strgerem ainda que o controlo de matos, as mobilizações do solo e o pastoreio afectam a disnibuição espaciale

temporal dos

macrofungos (Courtecuisse2001,

Pilz

andMolina

2001,Wiensczyk

et

al

2002).Importa

pois,clarificar

quais os factores que influe,nciam directame,nte as comrmidadesde macrofirngos, de forma a promover medidas de gestâo zustentável para este recuÍso.

ObjeAivos.' De forma a fundamentm estratégias de conservação e gestão pam as comrmidades

de macrofungos

em

montadosde

azirúo, no

Sul

dePortugal,

secom

o

presemteestudo

identificar quais

os

factores

arrbie,ntais (relacionadoscom

a

vegetação,solo

egeomorfologia do

t1rr*o)

queinfluenciam

a riqueza específica de macrofirngosna

área doParque de Nattueza de Noudar

(PNN)

e

averiguar a existência de relações lineares e,nte osFactores ambientaisque afectam a riqueza específica de macrofungos

desenvolvida

cúminando

na

redacção

do

artigo

"Biotic

and

úiotic

factoÍs

affecting

macrofungal richnessin holm

oak

standsof

SouthernPortugal",

enquadrado nesta tesepor

uma introdução geral e considerações finais.Aücionalmente,

aprese,nta-se a lista das especies consideradas no âmbito do tratamento de dados efectuado (Anexo).Área

deEstudo: O

elevado pote,ncial ecológicoe

paisagísticodo

Parque de Natureza deNoudar, contando com mais de 400 espécies vegetais e uma fauna diversa e abundante @orto

2006)

motivou

a sua escolha paraa

elaboração do prese,nte estudo. Situadono

concelho de Barrancos,dishito

de Bejao PNN

(Fla.

1) e,ngloba uma áreatotal

de 994,5 ha e encontra-sedelimitado a norte/noroeste pelo rio

Ardila

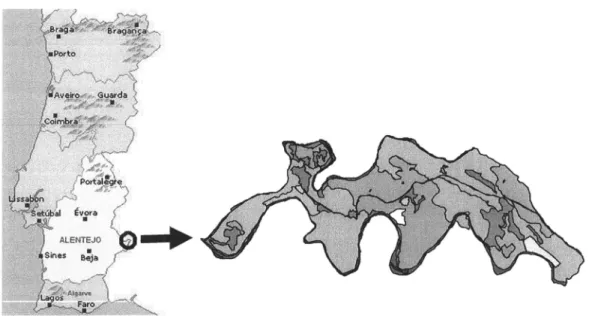

e a sul pela ribeira de Múrtega.Fig.

1. Área do Parque de Natureza de Noudar e respectiva localizagão em PortugalInserido numa

área classificadada

Rede Natura2000, forma

um

conjuntoecológico

comoutras

áreas proüegdasem

Espanha,com as q;riis faz

fronteira,

nomeadarnentecom

osParques

Naturais

da

SErra

de

Arace,nae

Picos

de

Aroche,

Serra

Norte

e

Serra

de Hornachuelos. Relativarnenteao

e,nquadramentogeológico, integra-se

na

7-onada

OssaMorena,

uma

das

grandes unidades

paleogeográficasque dividem

o

Maciço

lbfuico,

constituído por formações das Eras Pré-Câmbrica e Paleozóica.Na

área do PNN predominamos

"Litossolos

dos

climas

de

regime xérico",

de

xistos

ou

grauvaques,

surgindoFactoúçs anbientris que afeotam ariqueza específica de macmfrmgos

frequenteme,

te

associadosa

afloramentos rochososde xistos ou

grÍuvaques (Piçarraet

al2001).

O

PNN

enquadra-sena

área

do

macrobioclima

Mediterrâneo,bioclima

Pluüestacional

Ocefuiiço.

A

temperatura média anual do ar é de 15,8t

e a precipitação anualde

525,6nm,

ocorre,Írdo quase exclusivame,lrtena

estaçãomais

fria.

O

período seco@<2T) é longo

eprolonga-se geralme,rte de Jrmho a Setenrbro.

A

especie arbórea dominante é aaziúeira

(Queransrotundiftlia

L*.),

ocupando cerca de 70%

dafueatotal

doPNN,

formando povoarnentos com densidades arbustivas variáveis.De

acordo

com

Gomes

(1999)

os

azinhais

e

montados

enquadram-senas

formações .$zro bourgaeana-Qaercetumrotundifolia

e Asparagoalbi-Rhannion

oleoides, surgindo nas zonasmais

degradadasformações

da

classe

CistoJanndulaea.

Nos

montados abertos,

sãocaraoterísticas

as

pastagensde

üevo-subte,rrâneo (Poetea bulbosae)e

as

comunidades de Tuberarietea, zujeitas a pastoreio por gado bovino.Num

estudo previamente efectuado(Louro et

al

2009)

foram identificadas 162 espécies de macrofungos, para todos os biótopos presentes noPNN.

Destas, foram referidas pelaprimeira

vez77

espécies para a regrão do Alentejo e 8 para Portugal. Registou-se ainda a presença de 6 espécies consideradas raras na Península Ibérica, nomeadamente Agaricusporplryrizon

Orton,Ileodictyon

gracile

Berk.,

Lactarius

camphoratus(Bull.)

Fr., Lepiota oreadiformls

Velen.,Lancoagaricas melanotrichzs

var.

melanotrichns (Malençon

and-Bertault) Trimbach

e Phaeomarasmius erinacans(Pers)

Scherff.

ex

Romagn.. Adicionalmente registaram-se asespécies Amanita verna

(Butl.)

Lam., Cortinarius orellanus Fr.,Qnoporus

castanazs@ull.)

QuéI. e Hygrocybeconica

var.. conica (Scop.) P.Kumm.),

consideradas como potencialme,lrte ameaçadas(SMM

2008).Factorcs amhientais Ere afecrom a riçreza específica de maotofimgos

Biotic

and

abiotic factors affecting macrofungal

richness

in

holm

oak stands

of

Southern

Portugal

Rogério F. Louro I

Celeste

M.

Santos-SilvaInstitute of Mediterranean Agricultural md Environmental Sciences

Biology Deparhen! University of Érorc Apartado 94

7 OO2-S 5 4 ÉVORA, PoÍtugal

lConesponding

author: rog.louro@gmail.com

Ábsffact:

We used linear regression models to infer the relationship between macrofungal richnessand several environmelrtal variables, in holm oak stands. Therefore a macrofirngal inventory based on

fruit

bodies,was

conducted monthly,from

November 2005to April

2007,tn

pwe

Quercusronndifolia Lam stands on the Parque de Natureza de Noudar, located in Alentejo Province, Porhrgal. According to ouÍ rcsults, vegetation characteristics were the best descriptors of macrofungal richness

in

the studied area. Thus, mycorrhizal richness increases with tree age class and shrub oovetr, whilesaprotophic richness increases

with

shrub cover and herbaceous cover. Although, mycorrhizal and saprohophic richness models ditr€red from each other, results seem to ç,mphasize that shrubs me of theupmost importance

for

both

mycorrhizaland

sap,rotophic macrofungiin

holm

oak

montadoecosystems.

Key Words: microfimgal richness, linear regression, shrub covsr, holn oak stands, Portugal.

INTRODUCTION

Montado

ecosystemsare

Mediterraneâil ssvannah-like

rangelands characterisedby

the

p̀senceof

an opentee

stratum (40-50 treesper ha) mainly

composedof

evergreen oaks(Quercus

rotunddolta

Lam

or

Qtercus

suberL.)

(Gallardo

2003,Azul

2010). The

rmder-canopy stratum is generally comprised of pastures and agricultuml fields

in

a rotation schemethat includes fallows,

with

Mediterranean shrubsartificially

kept atlow

de,nsities (Carreiraset

Ll2006,

Pereira and Fonseca2003, Pecoet

aL2006,Pinto-Correia1993).

These ecosysterns have resultedfrom

a fransformation púocess of theoriginal

cork oak andholm

oak fo,rests,by

human activities, and are maintainedby

constant human intervention(Aztil

2002). Montadoecosysüems

ocsupy exteÍrsive

areas

in

southem Porfugal

and

are

the

most

commonagroforesty

systernsin

theAlelrtejo

Province (Porttrgal)(DGF

2001,Azul

2010). Montadosare

known

to

simultaneouslyprovide

multiple

goods and services(Vogiatzakis et

al

2406)

and

to

sustain avery high biodiversity

(Plieningerard

Wilbrand 2001), thus representing anFactores ubieúis çe afecüm a riqueza especlfica de macrofrrngos

example of ecologically sustainable agroforestry systÉ,m

(Azul

2002).Montado ecosysteÍns are

§ryically

managedfor

three main purposes: forestry, agriculture, aúrdextensive graz.ng @ereira and Fonseca2003), Cork removal and acom production have been

traditionally

accompaniedby mixed

livestock raising atlow

stocking de,nsiües andby

arablesystems

with

long-period rotations and

closednutient

cycles,without

extemal inputs

of

fodder, fertilizers

and

agro-chemicals

(Plieninger

and

WilbraÍld 2001).

Nevertheless,socioeconomic and land use changes over

the

secondhalf of

the twentiettr ce,lrttrry, such asintensive graang,

mechanizationof

agiculture

and

rural

desertification, resulted

in

soil

degradation,

tee

scarce,ress,lack

of

regeneration and shrub encroachment that may increaseconsiderably

the

rislc

of

forest fires,

pests and

diseases(Ferreira 2001,

ICN

2006).

For

instance, shrub clearing was

customarily

carriedout

manuallyonly

within

selected patches,minimizing

the damaged area. However, due topublic

forestry subsidies and motor powered machinery, shrub clearingis

nowadaysfar more

intensive, producing a more homogeneous and intense disturbançe (Perez-Ramos etaI2008).

Macrofungi

are arnong the most important organismsin

both natural and semi-natural forestecosysterns.

Without saprotophic

fungi, theprimary

decomposers of wood andlitter

(tlobbie

et

al

1999, Robinson et al 2005, 7-elleret

ad2007),Dffiy nutient

cycleswould

be drastically alte,red and forest ecosystemproductiüties

greatly reduced (Ricklefs andMiller

2000). Others, such asmycorrhizal

fungi are capableof

establishingslmbiotic

associationswith

the rootsof

most plant species, aiding in plant

nutient

and wateracqüsition

@runner 2001, Hartnett andWilson

20V2,Gúdot

et

aL2003, Smith and Read 2008), altering the competitive relationshipsamong

plants

of

different

species(Kennedy

et al

2003,

Egerton-Warburtonet

al

2007),protecting

their

hosts

from soil

pathoge,lrs (Amaranthus 1998,Harhett

and

Wilson

2002,

Smiú

and Read 2008) andfrom

environmental extemes (Amaranthus 1998, Smith and Read2008), and

play

an important rolein

the sequestrationof

Cin

soil (Treseder andAllen

2000).Even pathogenic

ftngi

enhance forestdiversity by

killing

&ees thatlatter

can become snags and logs that can be used by avariety

of other organisms(O'Dell

etal

1996).However, the importance

of fimgi

goesfar

beyond their fimdamentalrole in

many ecosystemfuirctions and processes since

they

influence humans and various human-related activities aswell

(Mueller

andBills

2004).Wild

mushrooms, thefruit

bodiesof

many forest macrofungi,are nowadays regarded as one

of

the

most important non-wood forest products @onetet al

2004,Garibay-Oriiel

et

al

2009).In

fact,

the fruit

bodiesof

morethan 3000

maorofungal species are consumed around theworld (Garibay-Orijel

etal

2009), and the economic valueof

some of them surlrassesby

far the valueof

timber(Arnolds

1995, Honrubia 2007).Moreoveç

Factores ambimais que efectam ariqueza espeoífica dc macroftmgos

mushrooms

sudden appeararrceand

beauty always

fascinatedpeople, making

them

alsoimportant

in

the contextof

nature conservation and manageÍnent (Süaatsma et al 2001).Most

surveys dealing

with

masofungi

are

basedon fruiting

bodies, since

fruit

bodies can

beidentified to

species and large numberof

plots can be continuously moniüored over a numberof

years (Schimt etal 1999,Dúlberg

etal

1997).The

biotic

andabiotic

factorsinfluencing

macrofungal species occuÍt€lrces and distributionsaÍe numerous and interactive (Beare et

al

1995). Plant species composition is known to be animportant

fastü

shaping macrofurtgal communities@ills et

al

1986,Bnmner

et

al

1992, Villerreuve etal

1989, Kernaghan and Harper 2001, Cavender-Bares et a12009, Jrmrpponenet

al

2010) since plants co,nstitute both habitat and energy sourcefor

most macrofungi andmany

of

themexhibit

some degreeof

plant host or substratum qpecificity(Iodge

et al 2004). Plantcommunity's stucürre is

also an influe,ntial factor determining the macrofimgal communitiesprese,nt

in

a site (Yang et al 2006). Treeor

canopy cover's influence on macrofungi has beenshown

in

many

studies,mostly

in

Boreal

forestsor

conifer trees (Villeneuve

et

al

1989,Rúling

andTyler

1990, Laganà etal

1999, Senn-klet andBieri

1999, Jansen 1991, Bonetet

al

2004, Richardet al2004,

De

Bellis

et

al

2006). Shrub cover and herbaceous cover alsohave

been shownto

influence macrofungi

occuÍreÍrce anddistribution

@úling

andTyler

1990, Richard et

al

2004), as many macrofungi are knownto

associatewith

particular shnrb species and evç,n show a certain degreeof

host specificity (Comandini et al 2006, Eberhardt etal

2009). Plus,

mostHygrophoraceae

species areknown

to

occur

chiefly

in

open,grass-dominated

sites(Ruhling and

Tyler

1990). Stand'successional changesmay

alsohave

animpact on

macrofungal communities(Keizer

andAmolds

1994, Se,nn-hlet andBieri

1999,Nordén

and Paltto 2001, Gates etal

2005,Twieg

et aI 2009),through the

establishmelrtof

new hosts and changes on the amowrt and/or

quallty of

bothlitter

and organic matter content(Lodge

et al2004) or simply

through

variationson

stand photosynthetic rates andgpwth

efficiency

@úlberg

2002, Naraet

al2003,

Bonet etal

2008). Edaphic and geomorphologicfeatues

such as soil nutrients, base saturation, organic matter, slope, aspest and altitude are alsoknown to

influence macrofungal commrmities presentin

a site@onet

eta72004, Engolast

ú

2007, Hansen 1988, Kernaghan and Harper 2001,Rúling

andTyler

1990,Twieg

etal

2009,Yang

etaI2006).

The limited

and oftetr

scatteredknowledge

on how silvicultural

treafrnentsatrect

fungalpopulations, make

it

extremely

difficult for

most

forest managenlto

integrate mushroom species,in

manageme,ntprograms (Martínez-Aragón

et

al

2007).Forest

managersneed

abetter

understandingof

how their

choioeswill

influe,ncemacrofimgal communities

andFactorcs ambieotris que afectam ariqreza especlficade macrofungos

mushoom

yields

if

they want

to

explorethis

resource(Pilz

andMolina

2001).Yet,

to

our

knowledgeonly

afew

models regarding mushrooms have been developed sofar

(Yang et al2006).

For

instance, Hansen(1988)

usedsoil

and

litter

variablesto

predict

macrofimgaloccure,nces

in

Swedish beech forests, Yang et al (2006) e'nrployed a logistic regression and aGIS

expert

systemto

model

the

fine-scale spatial

distibution

of

matsutakein

Ytmnan,southwest China, Martínez-Aragón et

al

Q007) and Bonet etal

(2008) developed predicüve equationsfor

ectomycorrhizal and selectededible

saprotrophicfilngr productiüties in

pine

forests

of

the

pre-Pyreneesmountains

of

Spain and

Dúl

et

al

(2008) used

weatherinforrration

to predict

mushroom abundancein

Norway. According

to

somearthors,

thedevelopme,lrt

of

mechanistic models based onempirical

studiesover

a broad rarrgeof

forest§pes,

stand conditions, andsite factors might facilitate

forestersto

better

evaluate habitatconditions

for

mushrooms@ilz

et

al

2001, Bonnetet

a12004,Dúl

etal

2008). Moreover,land-use changes,

particularly

in

foresüry andagiculture,

are themajor

causesof

change anddecline

of

macrofungal

diversity

in

Ernope(Senn-hlet

et

al

2007). Therefore,

sustaining appropriate forest habitatis

esse,ntialfor

sustaining mushroom diversity andyields @ilz

et al 2001).In

orderto find

simple and applicable models that can explainhow

environme,ntal conditioninflue,nces macrofungal richness

we

developed linear regression modelsfor wild

mushroom richnessin holm

oak(Querax rotundiftlia

Lam)

montado ecosystemin

Alentejo

Province, Southem Portugal.MATERIAL AND METHODS

Site

deseription.-T\e

study was conductedin holm

oak(Qtercus rotundifolia l-am)

stands on the Parque de Natureza de Noudar(PI[}$.

Located nearBarancos

(38o 08'N

and 6o59'W)

in

Alentejo

Province,Portugal. The

PNN

elrcompassesa total

areaof

994.5ha

andit

is

bordered o,n the north-west by theArdila

River and on the southby

theMírtega

stueam. Theclimate

istlpically

Mediüerranean pluviseasonal oceanicwith

a mean annual air temperafureof

15.8'C

and a mean annualrainfall

of

525.6mm.

Thedry

season isusually

from

Juneto

September

(Mendes

et

al

1991).

The

study

area

is

dominated

by

4ro

bourgaeana

-Quercetum

rotundiftlia

wtdAsparago

albi-Rhamnionoluides

formations,úhough

various elementsof

the

Cisto-lavanduleteaarc

rather freque,ntin

the most

degraded areas (Gomesleee).

Factues ambiemtais quc afecm a riqueza especlfica de macnofinges

Noveruber 2005 to

April

2007,in

33 permane,nt circular plots (250 m2 each) randomly chosenin

pnre Q.rotundifotiaLam

stands.All

observed macrofimgi epigeous spoÍocarpswithin

thesarrpling

plots were

collected

in

orderto

ensurethe

detectionof

thosetma

difficult

to

distinguish

in

thefield (O' Dell et alzüM).Identification

was done on-site at the momentof

detection, and whenever necessary specimenswere

kept

in

a

freezerat

3

"C

for

further

verification.

Represe,lrtative vouchEr collectionsfor all

observedtma

were deposited atthe

Évora University Herbarium(UEVH-

FUNGD. Each macrofungaltmon

was includedin

oneof

the

three

main

üophic

groups: saprotophic,

parasitic

or

mycorhizal,

according

to

@reitenbach and

Krânzlin

1984, 1986, 1991,1995,2000, Frade andAfonso

z003,More,no etal

1986,kânzlin

2005).

Those

taxa with more than

one

fiophic group,

depending on ecological and environmental conditions, were included in the mostlikely

trophic group.Plot chmacterization.-Envronrrrcntalvariables

were recorded at plot level and encompassedvegetation

characteristics(composition

and

structure),

soil

descriptors,slope and

aspect(TegLE

I).

Vegetation cover was calculated separatelyby

layer as the percentageof

canopy (tree, shnrb,herb

or

moss andlichen)

pnojection areaper

plot

area.To

estimatetree

4ge, annual ring counts were made on the cross sectisns of the Gore sâmples removed from the tree stems,at

0.5

m

height

with

an

increme,ntborer. Tree

ageswere

groupedinto

5

classes,respectively: 10-19 years, 20-29 years, 30-39 yearsl,

4049

years and 50-59 years. Diametersat breast height were measured

with

a tree calliper at 1.30 m height. Soil sarrples (4 replicates perplot)

were collected,using a

5

cm diametersoil

probe.Soil

organic matter content was calculated by weight differe,nce afterignition

(550'C

for

5 h in amuffle

fumace§abertherm

L9lC6).

Soil pH measureme,lrts were donein

an aqueous solutionof

l:2

(earttr:distilled water)

using a pH meter (Metuohm 691). Soil§pe

was consultedin

Portugal soil map(SROA

1973), lett€rs no.44-A

and44-8,

scale 1:50000, and was groupedin

5 classes ranging betweem 0.2 and 1. He,nce 0.2 was athibuted úo the shallower leptosols whereas the most evolvedluvisols

correspondedtol.

Statistical Analysis.-Envfuonme,ntal

variablesnormality

was

assessedusing

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Square

root

andlogarithmic

transformations wene usedto

achievenormality

when

necessary. Leve,ne'stests w€re

e,mployedto

assessthe

variance

homocedasticity assumption.fire

strength

of

the

linean association amongthe

depe,lrdentvariables (total

macrofimgal richness,

mycorrhizal

richness

and saprotophic

richness)

and

independent variables(Tarm I)

was quantified using the Pearson product-momelrt correlation coefficient.ll

Foctues ambientois que afectam a riçeza específicade macrofungos

EEEEEEg§EEEfiEEEE

ui

a B S

=

ü

o.i

r

oi

ct P d I H I

-.ioo(oo=oer\ooooo=oo

eoHox$oHoou.)Noxoo

O€O-ÊOOee\Ov-) eYíON-ioF-oR+dooo++oBcid

.t .ír t\

93

!l É \o

rô ôr ('r É §: § \o

o\88R+{F8RSã§Çõ3SN

..:oodãEóddôioôiaN§r-o

oo

oeu.)oot-oôloooooooo

o r.l t\ o (> N o \o (> o o Ê (ã o o o

qqqedqqqqqqqq<jqtq

r"l o g\ o o sf o o cn o F k.l Ô \o N o

É(ô

ooPPPrnF(noooooEgo

oç=xxo\ochoÉoNoo)<o

o cô 1. Y

=

r^ c'! q q q o! \o o ; Y t

c.;

o

=

R I,/i

o ci + o

od

vi a

Si

3

o

ü§n§[§fiEEÊf;üE$§§

e.i

€i

=

I § d o

o-

c"i

o ci vi 3 ãi =

€,§b

ÉEsssEEsggs§.§.#]

àEE-l

Bl

ɧÊs§ãEsg§§,ÊB,i

Êl

rãü(36EtrÉ

ãEIEEt

õrl

I E a Ex

6 É E ÉlE

É

rn o Eo ã 6 .t, í)E

É 6 !) 0 ÉI

Ê

() a lDn

0) -cr'cl I 6 d C) aD GI a or

o o, c)'o

E, E çr) É á d) t Ê oÀ

aÀ o E o.o

(D o) o o. ht€

C)E

o o (t) k ÍÀ o .Cl 6l 6l GI É (D É cl o É ril E É É-,'FactorGs mbientais que decÍm a riquea espeoífica de mauofirngos

The

thresholdvalue

for

deciding

on

Íedundancy arnong independent variables was setto

asignificant

correlationcoefficient

of

around0.6.

Stepwisemultiple

linea

regression analysis was then conductedto idenüff

the setof

independe,nt variables that bçtter explainvmiation

in

the response variables. Variable additions to the models continued

until

the significance levelof

F'values drop below the entry value (P < 0.05). Among all models computed we chose the ones

with

the

bestadjusünent

namelythe

oneswith:

highest adjusted coeffrcientof

determinationG'uj),

negligible residuals autocorrelation @urbin-Watson coefiEcientvalue

near2)and

with

anormal

residualsdisüibuüon.

AII

calculations were performedwith

SPSS 15.0for

Windows(SPSS Inc., Chicago,

IL).

RESI]LTS

Throughout

the

studyperiod a

total

of

lll

tma

belongtragto

57 genero were accountedfor,

encompassing79

saprotrophic

and

38

mycorrhizal macrofimgi. Members

in

the

order Agaricales comprised 81%

of thetotal identified

tma

(Ftc. 2).At

the genuslwel

Entoloma(6

sp.),Inocybe

(7

sp.),

Lepiota

(6

sp.),

À[ycena(7

sp)

and

Russula(s

sp)

were

the

mostrepresented genera 00 EO 70 ú €eo

$ro

E à40 .a Eao = 20 ío 0*d.P'/d"/

d/-//ry^C

Hc.

2. Species richness of several macrofirngal orders thnoughoú the study periodAround

9

Yoof

the

total

identified

Íara úowed a

widespread ocsuÍÍence, namely, Astraeus hygrometricas (Pçrs.) Morga,o, Gymnopusdrlnphilus (Bull.)

Murill,

Laccwia

laccato (Scop.)Cookg

LycoperdonatropurpneunYiltad.,

Lycoperdonp*latum

Pers., Iúycenapura

(Pers.) P.Kumm., Pmasola

mricoma

(Pat.)Redhea{ Vilgalys

and Hopple,Psathyrella

spadiceogrisea(Schaetr)

MaiÍe,

Psilocybe crobula

(Fr.)

Sing€r,Sclerofurma

verrucossurn(Bull.)

Pers. andFactores mbiGútaisque afectmr ariçrczaespeclfca de mcrofrntgos

Tubwia

romagnesiaruArnolds.

In

conüast,27

Yoof

the

total

identifred taxa

appearedonly

once

in

one plot, during the study period.None significant linear

corÍelations werefound

betweensoil

descriptors, slopeor

aspect andany

dependentvariable

(totat

macrofungal richness,mycorrhizal

richnessand

saprotrophicrichness).

In

what regards the vegetation characteristics, shrub cover, numberof

sbnrb species,mean shrub

height

herbaceous cover andlitter

height showed shonglinear

associationswith

some dependent

variables

(Teme

II).

Additionally,

a

large number

of

correlations amongvegetation characteristics

were

also

formd.

For

instance,

highly

significant

correlations(P<0.001,

n:33)

were found betweenúrub

cover and respective§, meanúÍub

height (0.114),úrub

species number (0.776) and meanlitter

height(0.7il).

Although

the large numberof

correlations among stand characteristics was expected,it

limited

the number

of

variablesto

be usedin

the models dueto

collinearity problems. Hence,only

thefollowing

variables were usedin

the multiple

linear regression analysis:tree

cover,tee

age class,úrub

coveÍ, aspect, slope, soil pH and organic matter content.Taslr

II. Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient @-values). Dependentvariables: mycorrhizal richness

(Mr),

saprofophic richness (Sr),total

macrofirngalrichness

(Tr).

* rqrese,nt significant correldions at P < 0.05 and**

at P < 0.001.Variables

Tr

NIT SrTree qge class Trce cover

Shrub cover

Horbaoeous cover

Mean tneo height Mean shrub height

Mean herbaceous height

Shrub species number Mean litterheight

Soil organio matter content Soil pH

Soil humidity

Moss and liohen covetr

Aspect Slope Soil type 0.395* 0.204

0.638**

-0.360 0.065 0.227 -0.342 0.467*0.493**

0.085 -0.115 -0.436 0.505 0.024 -0.072 -0.238 0.381 0.090 0.149 0.182 0.1470.479**

0.346*-0.382*

0.203 -0.203 -0.315-0,24t

-0.133 -0.266 0.429 0.188 -0.045 0.2580.746**

-0.678**

-0.158 0.479* -0.4810.608**

0.708**

0.243 -0.031 -0.273 0.158 -0.097 -0.045 -0.410FactoÍes mbientais qrn aftcam a riqueza específ ca de mamofimgos

The best adjusted models are

úown

in

TInLB

III.

Shrub cover, hee age class and herbaceouscover

were

the most significant

explanatoryvariables

of

total

macrofimgal richness. For

mycorrhizal

richness the best setof

explanatory variables wasúnrb

cover andüee

age class,whereas

for

saprotrophic richness rryasúnrb

covetrand

herbapeouslcover.

All

regressionsforcefully

passedthrough

the origin

sincethe

constantalways

showeda

significance

value higher than 0.05 inall

regressions.TasLE Itr. Multiple linear regression models for the anatysed response variables. Ty - Tree age class, Cs - Shnrb cover, Ch - Herbaceous cover

Response Variables Model summary

Rz

P-ValuesTotal maorofirngal richness (Tr)

Mycorrhizal richness (Mr) Saprotophic richness (Sr) Tr = 0.177Cs + 1.435Ty + 0.068Ch Mr=0.123Cs+0.739Ty Sr=0.058Cs+0.096Ch 0.94E 0.830 0.929 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001

In

orderto

examine exactlyhow

the

numberof

macrofimgal speciesvaried

in

regardto

the explanatory variables,we

plotted

the

response variablesas

a

function

of

each independentvariúle,

while

maintaining the other factors equal to their mean(Flc.

3,A-C).

Accordingto

ourresults

úrub

cover

exert more

influence

on

mycorrhizal

richnessthan on the

number

of

saprotrophic species. Thus,total

macrofimgal richness augmentwith úrub

cover seeÍnsmainly

athibutable

to

its

influence

on

mycorrhizal

richness.In

regardto

tee

age class,botfr total

macrofungal and mycorrhizal richness increaselinearly

with ree

age. Nevertheless, theformer

rises more steeply fhan the laÍer, possibly due to a positive, but not linear, saprohophic richness response

to

tee

age class. Herbaceous covetr,on the

other

handpositively

influences

bothsaprotrophio and

total macrofimgal

richness. However,the

less pronounced slopeon

thetotal

macrofimgal richness linear equation seerulto point out

a negative effectof

herbaceouscovet

on mycorrhizal richness.

Factü€s mbienAis que deorem ariErzaespeoíficade macroffmgos

A

25 0 20 20 G at aa*ts

t ê L atÉro

z

0 25 20 l5 0 0 a) I !) EI 0 li. c i. atê

Ez

5B

4íJ60

Shrubcovcr(7o) 3the

age chss4060

Ecúaccous cwer(Vo) 80 100 5 6 80 100 0 5 25 0 0 I 2 4C

20 e É) CIârs

b. c L oÊro

Itz

5 0 20FIG.3. Macrofimgal richness

(o-

total"

[

-mycorúizal,

A-

saproüophic) as a fimction of shnrb covor (À),tee

age class @) and herbaceous cover (C) accoding the equations shown onTeglp

III.

Fachúps ubienuis gue afectu a riquezr específica de mocrofungm

DISCUSSION

Many

authors consider edaphic and geomorphologicat features asimportant

factors a,ffectingthe macrofungal communities present

in

a site. However neither edaphionor

geomorphologic variables werelinearly

correlatedwith

mactofirogal ricbnessor

were included

in

any

of

the models computed.It

is

possible that those variables are only relevantin

awider

spatial scale, and therefore our results are merely a reflectionof

the naÍrolv spectreof this

sfudy, or perhapsthe

relationúip

betweenthem

and macrofungal richnessis

other thanlinear. On the

contrary vegetation descriptors seemedto

zuitably

explain the variationin

the macrofiugal

richnessof

the studied area.Rezutts

úowed

that

macrofimgat richnesswas

strongly relatedto

both tree

age and under-canopy vegetationcover

andthat the

numberof

macrofungal species increaseslinearly

with

them.

Yet, total

macrofungal,mycorrhizal

and saprotrophic richness modelsdiffer form

each other.Concerning

mycorrhizal

richness,resúts

úowed

that

it

only

increaseslinemly with

tree

ageand

with

the

percentageof úrub

coveÍ.

Concerninghee

age, recentworks

proposethat

thesuccessional changes effects

on

stand photosynthetic rates andgrowth efficiency may explain

the

variation

onthe

abundanceof

ectomycorrhizas and theirfruit

body production

(Dúlberg

2002,Nara

et alz003,Bonet

et al 2008). Asfor

shrub coveÍ's influence on mycorrhizal richness,Richard et al (2004)

working

in

an old-growth Mediterraneanforeit

dominatedby

Quercusilex

L.,

formdboú

ectomycorrhizal andsaprotophic

richness positively correlated ta Arbutusurudo

L.

density.

Also,

Comandini

et

al

(2006)

recognizedmore

than 200 fungal

speciesto

be associatedwith

Cisras spp. (the most abundant shrubtmon in

our study area),which

pointsout

the importance

of úrubs

as potential hostsfor

macrofungiin

Mediterranean forest eoosystems. Furthermore, accordingto

some authors, microenvironmental conditions such aslight,

moistureand

temperature encompassedby

densercanopy oover can

enhancemycorrhizal

divetsity

(KÍanabett€r andKroeger

2001,Bonnet etaL2004,

Santos-Silva etal

2010).In

asimilar

way,we propose that

is

also plausible that misroenvironmental conditions underúrubby

vegetationmay

allow

theestabliúment

of those mycorrhizal speoies that prefer shadier aÍeas, especiallyin

cases where tree density is

low.

Saprotrophic richness increases

linearly

with

shrub and herbaceouÍt coveÍ. Resourceavailability

is probably the more

likely

explanationfor

the linearrelationúip

between saproúophic richnessand

úrub

cover. Saprotrophicfimgr

areintimately

associated tothe

substatefrom

which

theyfee{,

and mâny show preferencefor

a specific shrublitter

(Robertset

al 2004). Moreover, theFac'toúes ebiêoteis qu€ a&cüm a riqueza sspecífica de maclofungoo

amount and

quality

of

available plantlitter

are knownto

alter the composition andstucture

of

decomposercommunities

(Wardle and Lavelle

1997,Wardle

et

al

2006). Thus,

it

seems possiblethat

shrubcontibution

to

úe

amount andquality

of

soil

litter in

ourplots

may have favoured saprohophic richness aswell.

As for

herbaceouscover,

Maggi

et

al

(2005) found

that

it

can affeot

microenvironmentalconditions at soil surface,

proüding

shade, increasing soil moisture content and thusproüding

agreater

protection

from

heat.

This may explain the

increasein

saprotrophicrichness,

as microenvironmental conditions are beüeved to directlyinpact

the fruitbodies transpiraüon rates(Kenmghan

and Harper 2001) and

consequently constrain mushroomproduction.

Substatespecificity also

oanexplain

someof

the

variation

in

saproúophic richness.In

fact,

severalhundred saprotrophic basidiomycete

fimgr

aÍe

moÍEoften found

in

grasslands(Griffith

andRoderick 2008),

or

areknown

to

occur mostly

io op"rt

grass-dominated sites(Ruhling

andTyler

1990). Additionatly, cattle's

presenceis

frequent

associatedto

open

areas whereherbaceous

cover

dominates.This probably

enablesthe

occurrenceof

many

coprophilousor

subcoprophilous macrofungi, usually linked to herbivorous dung.

In

summary,with this

studywe

aimedto

develop simple and accurate macrofungal richnessmodels

to

aid

nafire

conservation managercand

forestersto

better

undetstandhow their

decisions can

affect

macrofungal richness. Our results are therefore encouraging becausethey

demonstratethat

macrofirnsal richness

variations can

be

fairly

explained

by

vegetationcharacterisücs

that

can bereadily

influencedby

silvioultural

interventions.We

alsoúow

that

shrub cover is probably of the upmost importance

for

macrofimgal richness.If

we considerthat

in

this

ecosysüem shrubs are usually clearedout or

artificially

kept

atlow

densitiesto

preventthe

risk of

forestfiles,

new strategies may haveto

bç deüsedin

orderto

successfully man4gemacrofimgal ricbness.

This work is

a contributionto

the knowledgeof

fungal ecologyin

holm

oak montado

ecosystemsand furttrer

studies

in

other forest t),pes

with

different

stand characteristics arestill

necessaryin

orderto

fully

understand the natural mechanisms affecting macrofimgal richness.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research

was

supportedby EDIA (Alquwa

Infrastnrctures Development Enterprise).We

are grateful to PbD. Russell

/úprzrr

Jarafor

discussion on statistical analysis and to PhD.Isúel

Factores mbientais que afechm a riqueza específioa de nasroftuges

LITERATT'RE CITED

Amaranthus MP. 1998. The importancê and conservafion

of

ectomycorrizal fungat diversrtyin

forest ecosystems: lossons from Europe and the Pacific Northwest.In:

Gen. Tech. Rep. PNWGTR- 431. Portland. U.S. Deparünent of Agriculture, Forest Service. Pacific Northwest Resoarch Station. pl-15.

Arnolds

E.

1995. Conservation and managementof

naturalpopolrtiom

of

ediblefimgi.

Canadian Journal of Botany 7 3(l):987498.

Azul

AIv[, Sousa JP, Agsrer R, Martín MP, Freitas H. 2010. Land use practices and ectomycorrhizal fungal communities from oak woodlands dominded by Qaercus suberL. considering dÍought scenarios.Mycorrhiza 20:73-88.

Azul

AM.

2002. Díversidadede

fungos ectomicorrízicffrem

ecossistpmasde

Montado [Doctoraldissertationl. Coimbra, Porhrgal. Universidade de Coimbra.77í p.

Beare

MII,

Coleman DC,Cross§

Jr.DA,

Hendrix PF, Odum EP. 1995.A

hierarchical apprroach to evaluatingúe

sifficance

of soil biodiversity to biogeochemical cycling. Plant md Soil 170:5-22.Bills

G, Holtzmann G,Miller O.

1986. Comparison of ectomycorúizal basidiomycete communitiesin

red spruce versus northern hardwood forests of West

Virginia

Canadian Journal of Botanyil:76F768.

Bonet J, Fischer C, Colinas C.2004. The relationship betwee,n forest age and aspect on tho productionof

sporooarps of ectomycorrhizal fungt in Pímts sylvestris forests of the central §renees. Forest

Ecolory

and }úanagement 203 :l 57 -17 5.

Bonet J, Pukkala T, Fischer CR,

Palúí

M,

Martínez-'AragónI

Colinas C. 200&. Empirieal modelsfor

predicting the production

of wild

muúrooms in Scots pme(Pimn

sylvestrts L,) forests in the Celrtral$menees. Annals of Forest §cience 65(2):206.9 p.

Breitonbach

J,

trfuânzlinF.

1984. ChamFignonsde

Suisse,Tome

l:

Les

Ascomycêtes. Lucerne.MycologiaEd.313 p.

Breitenbach J,

Krâülin

F.

1986. Champignons de Suisse, Tome 2: Champignons sans lamos. Lucerne. MycologiaEd.4l2p.

Breite,lrbach J, KÍânzlitr F. 1991. Champignons de Sússe, Tomo 3: Bolets et champignons à lames lêne partie. Lucerne. Mycologia Ed. 360 p.

Breitenbach

I

KrenzünF.

1995. Champignons de Sússe, Tome 4: Champignons à lames2tu

partie.Luoerne. Mycologia Ed. 368 p.

Breitenbach J, Krânzlin F. 2000. Champignons de §uisse, Tome 5: Champignons à lames

3tu

partie.Luoerne. Mycologia Ed. 338 p.

Bruoner

I,

Brunner F, Laursen G.1992. Characterization and comparison of macrofimgal communiüesn

n, Alrustmuiftlia

and an Álnuscrisry

forest in Alaska. Canadian Journal of Botany 70:1247-1258.Brunner

I.

2001. Ectomycorrhizas:their role

in

forest ecosystems under the impactof

acidifring

pollutants. Perspectives in Plant Ecolory, Evolúion and Systematics

4(l):13-27.

Carreiras

JMB,

Pereira JMC, Pereira JS. 2006. Estimaüonof

fiee

canopÍy coverin

wergreen oak woodlands using remote sensing. Forest Ecolory and Mamagement 223:45-53.Cavender-Bares

J,Izzn

A,

Robinson R, Lovelock CÊ^ 2009. Changesin

ectomycorrhizal community structureon

two

containerizedoak

hosts across an experimental hydrologic gradient. Mycorrhiza L9:133-142.Faotdes mbientais 4re &cta,m ariquua específca do mamofiutgps

Comandini O, Contu lrd, Rinaldi AC. 2006. An overview

of

CfuÍas eotomycorrhizalfung.

Mycorrhiza l6:381-395.Dahl

FA" Galteland!

GjelsvikR

2008. Statistical modellingof

wildwood mushroom abundance.Scandinaüan Journal of Forest Research 23Q):2a+-V19.

Dúlberg

A, Jonsson L, Nylund 18.1997. Species diversity and distibtltion of biomass above and below ground among ectomycorrhizal fungr in a old-growth Norway spruce forest in south Sweden. Canadian Journal of Botany 15 :1323-1335.Dúlberg

A.

2002. Effectsof

fire on

ectomycorrhizal fungtin

Fennoscandian boneal forests. SilvaFennica

36(l):6H0.

De Bellis T, Kernaghan G, Bradley R, Widden P. 2006. Relationships between stand composition and ectomycorrhizal community structure in boreal mixed-wood foresB, Mcrobial Ecolory 52:11Ç126. DGF. 2001. Inventfuio Florestal Nacional: Porhgal Continental, 3o Rsvisão. Lisboa. Direcç,ão-Geral das

Florestas.233 p.

Eberhardt U, Beker HJ, Vila J, Vesterholt J, Llimona X, Gadjieva R. 2009. Hebelorn species associated

with Crsrn§. Mycological Rssearch

ll3

:153-162.Egerton-Warburton

IÀI,

Querej@JI, Allen MF.

2007. Common mycorrhizal networks provide apotential pathway for the transfer of hydraulically lifted water between plants. Joumal of Experimental Botany 58(6): 1473-1483.

Engola APO, Eilu G, Kabasa JD, Kisovi L, Munishi PKT, Olila D.2007. Ecolory of edible indigenous müshrooms ofthe lake VitoriaBasin (Uganda). Reserirch Journal of Biological Soiences

2(l):62-ó8.

Ferreira

DB.

2001. Evolução da paisagem de montadono

Alentejo Interiorao

longodo

séc)O*

Dinâmica e incidências ambientais. Finisterra 36(72):179-193.Frade B, Alfonso A.2003. Atlas fotogrrófico de los hongos de la Península Ibérica. León. Celarap Ed.

547 p.

Gallaldo

A.

2003. Effect of tree canopy on tho spanial distribution of soil nutientsin

a Mediterraneandehesa. Pedobiologia 47

:ll7

-125.Garibay-Orijel

&

Córdova J, Cifue,ntes J, Valenzuela R, EsEada-TorresA,

KongA.

2009.Integrating wildmuúroorls

use into a model of zustainable management for indigenous community forests. ForestEcolory aod I!{anagement 2582122-13

l.

Gates

GIú,

RatkowskyDÀ

Grove SJ. 2005.A

comparisonof

macrofungiin

yormg silvioulhrralregenemation and maturp forest at the Warra LTER Site in the southern forests of Tasmania. Tasforests

t6-.127-152.

Gomes

L.

1999. Herdade daCoitadiúa

-

Flora e Vegetação. Relatório complementar realizado pela Naturibérica para aEDIÀ

Empnesa de Desenvolvimento e Infra-estuturas do Alqueva.4l

p.GÍiffith

GW, RodericklC 2008. Saprofophic basidiomycetes in grasslands: distibution and fimction.In:Boddy

L,

FrarHandI

Van

Wost P, eds. 2008.Ecolory

of

Saprotnophio Basidiomyoete. Kew. The British Mycologioal Society. Elsevier. p 27 5-297.Guidot A, Debaud J-C, Effosse A, Marmeisse R. 2003. Below-ground distribution and persistence of an

FactoÍes mbiemtaisque &cüm a riqum específica de mrcÍofingos

Ilanse,n PA. 1988. Prediction of macrofungal occrrrence

in

Swediú beech forests from soil and littervariable models. Vegetatio 7

8:3144.

Harhett DC, Wilson GT. 2002. The role

of

mycotrhizasin

plant commtmity süucture and dlmamics: Lessons from grasslands. Plant and §oil 2442319-331.Hobbie EA" Macko

SÀ

ShugaÍtH.

1999. Insights into nitrogen and carbon dlmâmics of ectomycorrhizaland saprotuophic fimgr from isotopic evidence. Oecologia llE:353-360.

Honrubia M.2OO7. Aprovechamientos micológicos

y

desarrollo sostenible.In:

Junta de AndaluciqConsejeria de Medio Ambiente, Ed. World Fungt 2007. Proceedings of the first world confercnce on the conservation and sustainable use of wild fungi. Cordoba, Spain. p 46.

ICN. 2006. Plano Sectorial da RedeNatura 2000. Instituto de Conservação daNaturezq Lisboa. [online] URL: http://www.icn.pt/psrn2000/caÍacterizaoao_valores_naturais/habitatV9340.pdf.

Jansen

AE.

1991, The mycorrhizal status of douglasfir

in The Neúerlands: its relationwith

stand age,regional facto,rs, atmospherio pollutants and

tee

vitality.

Agriculture, Ecosystems and Envircnment35@-3):t9t-208.

Jumpponen

A,

LonesIJÇ

IvÍattox JD, Yaege C. 2010. Massively parallel 454-sequencingof

fungal communitiesn

Querats spp. ectomycorúizas indioates seasonal dynamicsin

urban and rural sites.Molecular Ecolory 19(1

):al-53.

Keizer PJ, Arnolds

E.

1994. Successionof

eotomycorrhizal fungtin

roadside verges planted withcommon oak(Qtwcus robtn L.) in Dr,enúe, theNetherlands. Mycorrhiza 4:147-159.

Keonedy PG,

lnb

AD,

BrunsTD.

2003. Thoreis

high

potentialfor

the

formationof

common mycorrhizal networks betrreen understorey and canopy treesin

a mixed evergreÊn forest. Jotrnalof

Ecolory 91:1071-1080.

Kernaghan

G,IlarperK.

2001. Community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungr across an alpine/subalpineecotone. Ecography 24(2): I 8 1-l 88.

Ikanabetter JUI, Kroeger P. 2001. Ectomyoorrhizal mushroom response to partial cuüing

in

a western hemlock-

western redcedar forest. Canadian Joumal of Forest Research 3l:978-987.KÍânzlin F. 2005. Champignons de Suisse, Tome 6: Russulaceae. Luçerno. Mycologia Ed. 319 p.

Laganà

A,

Loppi S,

h

DominicisV.

1999. Rolationship betnveen environmental factors and the proportionsof

fungpl trophic groupsin

forest ecosystemsof

the oenüal Mediterranean area. ForestEcolory and Management 124:145-151.

Iodge

DJ, Ammfuati JF,O'Dell

E, Mueller GM. 2004. Collecting and describing macrofimgi.In:

G.Mueller G, Bills G, Foster

M

eds. 2004. Biodivosity of Fungi - Inventory and Monitoring Merthods. SanDiego. ElsevierAcademic Press.

p

128-158.Maggi O, Persiani

AM,

CasadoMA,

Pineda FD. 2005. Effects of elwation, slope position and livestock exclusion on microfuirgi isolated from soils ofMediterranean grasslands. Mycologia 97(5):98ç995,Martínez-Aragón

J,

BonetJA

FischerC&

ColinasC.

2007. Productivityof

ectomycorrhizal andseleoted edible saprotrophic fungr

in

pine forestsof

the

pre-$nenees mountains, Spain: h,edictive equations for forest managsment of mycological resources. Forest Ecolory and Management252:239-256.