Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro

Retrospective study of keratoma lesions

Dissertação de Mestrado Integrado em Medicina Veterinária

Joana Sofia Terra e Pereira

Orientador: Professor Doutor Mário Pedro Gonçalves Cotovio

ii

Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro

Retrospective study of keratoma lesions

Dissertação de Mestrado Integrado em Medicina Veterinária

Joana Sofia Terra e Pereira

Composição do júri:

Presidente: Professora Doutora Maria da Conceição Medeiros Castro

Fontes

Arguente: Professor Doutor Filipe da Costa Silva

Orientador: Professor Doutor Mário Pedro Gonçalves Cotovio

iii

Declaração:

Nome: Joana Sofia Terra e Pereira

C.C: 13853001

Telemóvel: (+351) 918959707

Correio Eletrónico: joanaterrapereira@gmail.com

Designação do Mestrado: Mestrado Integrado em Medicina Veterinária

Título da dissertação de Mestrado em Medicina Veterinária: Retrospective study of

keratoma lesions

Orientador: Professor Doutor Mário Pedro Gonçalves Cotovio

Ano de Conclusão: 2017

Declaro que esta dissertação de mestrado é o resultado de uma pesquisa e trabalho pessoal efetuada por mim e orientada pelo meu supervisor. O seu conteúdo é original e todas as fontes consultadas estão devidamente citadas no texto e mencionadas na bibliografia final. Declaro ainda que este trabalho não foi apresentado em nenhuma outra instituição para a obtenção de qualquer grau académico.

Vila Real, Julho de 2017 Joana Sofia Terra e Pereira

iv

v

Agradecimentos

Ao meu orientador, Professor Doutor Mário Cotovio, pela sua disponibilidade, tempo, energia e paciência. Sem o qual não seria possível terminar este trabalho.

To the University of Gent and everyone there that in some way helped me with my thesis: Professor Frederik Pille for all the support and great ideas about keratomas; Michäel that helped me with the translation of all the data; Werner that did the questionnaire; Anna that was the best buddy anyone could have and helped me a lot with the bibliography; and all the others who made part of this amazing experience.

Aos meus pais, que me apoiaram quando decidi mudar de curso e seguir este sonho, tornaram tudo isto possível e foram dois verdadeiros pilares durante estes 6 anos.

À Luísa, pela amizade incondicional, por toda a motivação, companhia e força, nos bons e maus momentos. E também pela ajuda preciosa na análise de dados.

À Beatriz, por ser uma força da natureza e por garantir que esta tese tem o melhor inglês alguma vez escrito por mim.

Às outras meninas, Laura, Benedita e Catarina, por apesar de longe, estão sempre presentes.

Aos amigos que fiz em Vila Real, em especial à Sofia, com a qual vivi e convivi e com a qual espero continuar a conviver.

Ao Sargento Vilela e família, por me ensinarem o que é a equitação e por me mostrarem que é a trabalhar que realizamos os nossos sonhos. E claro, à grande família que é a Escola de equitação do Carmo de onde levo amigos para a vida, que sempre me incentivaram a seguir em frente.

À Sofia, que durante estes 6 anos foi sempre a amiga inacreditável de todos os momentos.

A todos aquele que não foram mencionados, mas que de uma forma ou de outra me ajudaram a concretizar este sonho.

vi

Abstract

Keratomas are the most common hoof neoformation diagnosed in horses. They are the result of abnormal proliferation of the squamous epithelial cells, producers of horn. It is thought that this proliferation is caused by chronic insult to the hoof caused by recurrent abscess, white line disease, and hoof cracks, for example. There is no breed, gender or age predisposition for the development of this lesions. Being an expansive lesion, the keratoma will exert pressure on the hoof laminae and distal phalanx, resulting on the horse presenting lameness.

After diagnosing the lesion, the treatment of choice is the excision of the abnormal hoof tissue. The total or partial excision can be performed according to the case. If all the abnormal tissue is removed the prognosis is good.

This thesis primary objective is to study the particularities of keratoma or keratoma-like lesion. The study consists on the review of 21 cases, from the University of Gent large animal hospital, diagnosed and treated for keratoma lesions between 2008 and 2016. The records of this horses were reviewed regarding age, breed, gender, clinical history, clinical findings, affected leg, grade of lameness, and digital pulse. The radiographic studies of the horses were also reviewed, and the register of type of anaesthesia and hospitalization complications was made. A telephone questionnaire was performed to collect information about the outcome of each horse after the partial excision of the lesion. In this questionnaire information like activity, housing, shoeing, time of recovery and hoof growth, complications, and recovery were collected.

In this review of 8 years, 52% of the animals presented clinical history of hoof abscess and 87% had radiographic findings compatible with the presence of a keratoma lesion. Fifty percent of the horses developed an abnormal hoof conformation after the resection, but only 20% did not return to soundness. Recurrence of the keratoma was higher than expected, with 60% of the horses displaying recurrence 1 to 4 years after the excision. The high rate of recurrence could be due to incomplete resection of the lesion.

vii

Resumo

O queratoma é a neoformação do casco diagnosticada com mais frequência em cavalos. Resulta da proliferação anormal das células do epitélio estratificado, produtoras de casco. Pensa-se que esta proliferação anormal seja causada por agressão crónica dos tecidos do casco, por exemplo, por abcessos submurais, doença da linha branca ou fissuras do casco. Não existem raças, idades ou géneros predispostos para o desenvolvimento destas lesões. Uma vez que são lesões expansivas, vão exercer pressão nas lâminas do casco e na falange distal, resultando no aparecimento de claudicação.

Depois de diagnosticado, o tratamento preferencial é a excisão dos tecidos anómalos. A excisão parcial ou total do casco deve ser realizada de acordo com a lesão e o animal em causa. Se todo o tecido anómalo for removido o prognóstico é bom.

O objetivo primário desta tese é o estudo das particularidades dos queratomas e lesões semelhantes. Este estudo consiste na revisão de 21 casos, do hospital de grandes animais da Universidade de Gent, diagnosticados e tratados para lesões de queratoma, entre 2008 e 2016. Os registos destes cavalos foram revistos em relação a idade, raça, género, história clinica, achados clínicos, membro afetado, grau de claudicação e pulso digital. Os estudos radiográficos também foram revistos, e o tipo de anestesia e complicações durante a hospitalização foram registados. Foi realizado um questionário por telefone de forma a recolher informação sobre o resultado da excisão parcial da lesão para cada cavalo. Neste questionário informações como atividade, tipo de alojamento, tipo de ferração, tempo de recuperação e crescimento do casco, complicações e recidiva, foram recolhidas.

Nesta revisão de 8 anos, 52% dos animais apresentaram história clinica de abcessos do casco e 87% tinham alterações radiográficas compatíveis com a presenta de queratoma. Cinquenta por cento dos cavalos desenvolveu conformação de casco anormal após a excisão mas só 20% mantiveram a claudicação. A recorrência das lesões foi mais alta do que esperado, com 60% dos animais a apresentar recorrência 1 a 4 anos após a excisão. Esta elevada taxa de recorrência pode ser devia a uma incompleta ressecção das lesões.

viii

Index

1 Bibliographic Review ...1 1.1 Introduction ...1 1.2 Aetiology ...2 1.3 Pathologic Anatomy ...2 1.4 Histology ...4 1.5 Physiopathology ...5 1.6 Clinical Signs ...5 1.7 Differential Diagnosis...6 1.8 Diagnostic...7 1.8.1 Perineural anaesthesia ...8 1.8.2 Radiography...8 1.8.3 Other methods ...9 1.9 Treatment ... 11 1.9.1 Conservative ... 11 1.9.2 Surgical ... 11 1.9.3 Anaesthesia ... 14 1.9.4 Bandaging ... 15 1.9.5 Post-Operative care ... 15 1.9.6 Shoeing ... 16 1.10 Prognosis ... 17 2 Objectives ... 183 Material and Methods... 19

3.1 Evaluation of the case ... 19

3.2 Keratoma excision ... 19

3.3 Postoperative care... 21

ix 4 Results ... 22 4.1 General characteristics ... 22 4.2 Clinical Results ... 22 4.2.1 History ... 22 4.2.2 Clinical Findings ... 23 4.3 Radiographic Results ... 24 4.4 Treatment proceedings ... 25 4.5 Questionnaire results ... 26 4.5.1 General characteristics... 26 4.5.2 Outcome results ... 26 5 Discussion ... 28 6 Conclusions ... 32 7 Bibliography ... 33

x

Figure Index

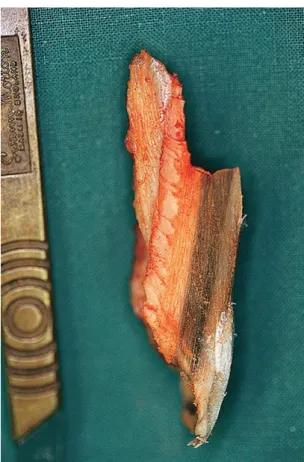

Figure 1 - Cylindrical keratoma.………. 1

Figure 2 - Tubular keratoma………... 3

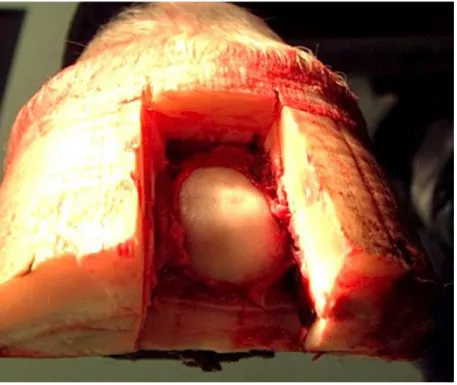

Figure 3 - Spherical keratoma inside the hoof………. 4

Figure 4 - Histologic image of a keratoma………... 5

Figure 5 - Deviation of the white line ………. 7

Figure 6 - Radiographic image of P3………. 8

Figure 7 - Total Resection of a keratoma……….. 12

Figure 8 - Radical resection of multiple keratoma lesions……….. 12

Figure 9 - Window for partial resection of keratoma ……… 13

Figure 10 - Partial resection of keratoma with solar window……….. 14

Figure 11 - Metal bridge to provide stability after resection……… 16

Table Index

Table 1 - Weight in kilograms and age in years……….. 22Table 2 - Relation between the clinical findings and the location of the lesions……… 24

Table 3 - Days of hospitalization……… 25

Table 4 - Time of recovery and time of hoof growth in months………. 26

Table 5 - Association between recurrence and foot affected………. 27

Graphic Index

Graphic 1 - Summary of the clinical history of the horses included in this study………. 23xi

Abbreviations List

CT- Computed Tomography DP – Dorsopalmar view

D55Pr-PADIO - Dorso-proximal palmaro-distal oblique with 55º view LM – Lateromedial view

MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging P3- Pedal bone/distal phalanx PMMA - Polymethacrylate

STIR – Short Tau Inversion Recovery (in MRI) T1 – Short Repetition Time and Echo Time (in MRI) T2 – Long Repetition Time and Echo Time (in MRI)

Warmblood BWP – Belgian Warmblood Horse (Belgisch Warmbloed Paard )

Warmblood KWPN – Royal Warmblood Horse of the Netherlands (Koninklijk Warmbloed Paard Nederland )

Warmblood SBS – Royal Belgian Sport Horse Warmblood SF – Warmblood Selle Français

1

1 Bibliographic Review

1.1 Introduction

Keratomas result from the abnormal proliferation of keratin tissue and squamous epithelial cells, the producers of horn, creating focal areas of abnormal corium (Eastman, 2015; Turner, 2016). They are a benign keratin-containing soft tissue mass that develops between the hoof wall and the distal phalanx (Redding, 2007), generally located in the inner surface of the coronary band, hoof wall, or sole (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015b). Keratomas, though the most frequently diagnosed mass involving the equine hoof, are a rare condition (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a).

This horn defect that develops in the inner aspect of the hoof wall has a size variation from a few millimetres to 2-3 centimetres. It may extend only a short way up the hoof wall or reach from cornet to sole (Knottenbelt and Pascoe, 1994). There is a classic form, cylindrical with a protrusion parallel to the horn tubules (figure 1), and a spherical form that has been described anywhere in the hoof (Fürst and Lischer, 2006).

It is debatable whether keratomas are a genuinely neoplastic state, with some authors regarding it as non-neoplastic epidermal or follicular cysts (a theory supported by their histological appearance) (Valentine, 2006; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a).

Figure 1 - Extracted cylindrical keratoma. Image kindly provided by the University of Gent

2

1.2 Aetiology

It is thought that keratomas are produced by germinal epithelial cells in response to chronic irritation of the coronary band, dorsal laminae or solar corium by pressure, injury, abscess formation, or chronic pododermatitis (Redding, 2007; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). When the coronary band or the laminae suffers trauma or local inflammation there can be formation of scar tissue that will gradually grow distally inside the hoof capsule, forming the keratoma (Fürst and Lischer, 2006). Some cases have developed without history of previous injury and with unknown initiating cause (Knottenbelt and Pascoe, 1994; Baxter et al., 2002; Fürst and Lischer, 2006; MacDonald, 2006; Redding, 2007). There is a speculation that there could be a progression to squamous cell carcinoma (Durham and Walmsley, 1997; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). It is also described as a complication of the arthroscopic surgery of the dorsal distal interphalangeal joint for treatment of extensor process fragments, in case of damage to the coronary band or the attachment of the common digital extensor tendon (Boening, 2002).

Growth usually begins near the coronary band, but may extend to the solar surface anywhere along the white line (Baxter et al., 2002). The majority of the lesions are found in the dorsal aspect of the hoof wall (Fürst and Lischer, 2006). The coronary band seems to be the most common site of origin, and on rare occasions these lesions arise from the sole (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a).

There has not been found any breed or gender predisposition (Moyer, 1999; Eastman, 2015), and it has been reported in horses from various ranges of age (Baxter et al., 2002; Valentine, 2006; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). Although various studies and case reports, describe the lesions in various breeds such as: thoroughbreds, thoroughbred-crosses, ponies, hanoverians, clydesales, arabians and warmbloods. (Boys Smith et al., 2006; McDiarmid, 2007; Gasiorowski, Getman and Richardson, 2011; Greet, 2016; Rowland et al., 2016). Forelimb keratomas are more common than hind limb ones (Moyer, 1999; Eastman, 2015).

1.3 Pathologic Anatomy

Usually keratomas are slow-growing solitary lesions, even though multiple masses have been reported (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). In a recent publication there is a description of a biaxial keratoma detected in radiographs and confirmed histologically, in a 15-year old Clydesdale mare (Rowland et al., 2016). Also in the publication of Greet, (2016) it is suggested that multiple keratoma lesions might not be as rare as we think because it is not uncommon to find a small spherical keratoma underlying a cylindrical (figure 2) one once it has been removed.

3 Keratomas typically arise just distal to the coronary band; where they present as a raised lesion on the dorsal or lateral hoof wall, if sufficiently large to cause hoof deformation. As they grow downwards, the lesion might be found at any location from the coronary band to the solar surface. Usually they are found in the toe or quarters and in some cases lameness is not present until it actually reaches the weight-bearing surface (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). A keratoma was reported in the corium of the frog in a case report by McDiarmid et al. (2007) and there are also reports of keratomas proximal to the coronary band located on P2 by Gasiorowski et al., (2011). These last ones were unusually mineralized and therefore visible radiographically. The mineralization and the unusual location suggests that the lesions are not always caused by hoof irritation or trauma and that keratomas can be observed out of the hoof capsule (Gasiorowski, Getman and Richardson, 2011; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a).

As referred before, keratomas have a wide size variation and multiple forms, the spherical form (figure 3) is mostly found near the toe region (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). Generally the central material is grey, tan, yellow, white or brown and friable. It may have a concentrically laminated appearance resembling an onion (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a).

4

1.4 Histology

Standard staining with haematoxylin and eosin may be used for diagnosis (figure 4). Samples can also be stained for collagen (Masson’s trichrome) or keratin (Ayoub-Shklar) (Rowland et al., 2016). A cyst wall composed of proliferation of a well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium that is keratinized centrally characterizes histological examination of the lesions, this epithelial layer may be thin in some cases. When the keratoma is located at the coronary band, partial mineralization of the keratin debris can happen and can be visible radiographically. Associated to these lesions may be inflammation and granulation tissue formation. The adjacent primary epidermal lamellae of the hoof wall can present flattened and distorted, blunted or absent (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). In a study by Boys Smith et al.,(2006) focal bacterial colonization is reported.

In Tatarniuk et al.,(2013) the author states that hyperplastic and hyperkeratotic laminar lesion may represent the early stages of keratoma growth.

Figure 3 - Spherical keratoma inside the hoof. Adapted from Greet, 2016

5

1.5 Physiopathology

Because the keratomas are expansive lesions and the hoof is rather a hard structure, there is pressure exerted on the hoof laminae and distal phalanx, which can lead to inflammation and lysis of the bone (Fürst and Lischer, 2006; Redding, 2007). As time progresses there is more pressure exerted in the pedal bone creating initially a small area of osteoporosis that with time elongates causing pressure necrosis (Kaneps, 2004). When the hoof does not have a normal architecture, bacterial colonization of the region surrounding the lesion can happen, leading to the development of submural abscesses (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003).

As the defect increases in size, lameness gradually develops with the horse shifting the weight way from the lesion (Hickman, 1985). If large enough, a keratoma that occurs between the distal phalangeal bone and the hoof wall will create sufficient pressure on sensitive hoof lamellae and bone to result in significant continuous or intermittent lameness. In one case diagnosed on a mule, there was a secondary pathological fracture of P3 extending from the solar to articular surface (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a).

1.6 Clinical Signs

Clinical sings are variable and depend on the size of the keratoma, but according to some authors initial lesions are an uncommon cause of lameness (Redding, 2007). Progressively developing lameness is often the presenting complaint (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003) and it is often seen before the distortion of the coronary band or hoof wall becomes

Figure 4 - Histologic image of a keratoma. Keratinocytes in sheets with multifocal accumulations of keratin (white

6 obvious (Baxter et al., 2002). This lameness can occur due to pressure exerted in the sensitive laminae or by a disruption of normal hoof architecture (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). By the time horses are presented for lameness exam it is typically 3/5 or 4/5 (Eastman, 2015). This mild to moderate lameness depends on the degree of the damage. Severe lameness is usually caused by disruption of the normal hoof architecture with subsequent abscess formation. The lameness may become progressively worse as the keratoma grows and takes more space in the hoof capsule (Redding, 2007).

Drainage from the white line or coronary band can also be observed in some cases (Kaneps, 2004).

1.7 Differential Diagnosis

There are many hoof conditions that present the same clinic signs than the keratoma. These can be divided in neoplastic and non-neoplastic.

Neoplastic:

-Squamous cells carcinoma, second most common tumour of the hoof, but histological characteristics of squamous cell carcinomas include a lack of organisation and invasion of the laminar corium (Rowland et al., 2016);

-Anaplastic malignant melanoma; -Osteosarcoma;

-Sarcoid; -Canker.

(Baxter et al., 2002; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015b)

Non-neoplastic: -Abscess;

-Intraosseous epidermoid cyst (usually without wall or sole destruction);

-Exuberant granulation tissue-Focal Osteomyelitis (no sclerosis is observed on radiographs); -Distal Phalanx Fracture;

-Suppurative pododermatitis (gravel); -Severe bruising of the hoof.

(Moyer, 1999; Pascoe and Knottenbelt, 1999; Ross and Dyson, 2003; Kaneps, 2004; Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015b)

7 Other neoplastic conditions are usually associated with more severe lameness (Ross and Dyson, 2003)

1.8 Diagnostic

Clinically it is very difficult to identify a keratoma. The only indication might be just a distortion of the white line (figure 5). In some cases fistulous tracts between the coronet and the sole or hoof wall develop and mimic a subsolar abscess, causing lameness (Knottenbelt and Pascoe, 1994; Baxter et al., 2002). If there is a history of recurrent abscesses localized in the same area, keratoma should be suspected (Redding and O’Grady, 2012).

A careful inspection of the hoof sole is essential through trimming and cleaning. The white line should be checked for abnormal configuration where typically the lamellar horn is replaced by tubular horn and scar tissue. This tissue displaces the white line in the direction of the sole (Fürst and Lischer, 2006).

Sensitivity to the hoof testers can vary, depending on the location of the mass, but usually there is a painful response given when pressuring the lesion (Moyer, 1999; Baxter et al., 2002; Eastman, 2015). Sometimes, can be identified incidentally during foot paring and shoeing (Pascoe and Knottenbelt, 1999)

Figure 5 - Deviation of the white line towards the center due to the presence of keratoma. Adapted from Redding and O’Grady, 2012

8

1.8.1 Perineural anaesthesia

The location of the mass and pain will determine the type of nerve block that will improve the lameness (Moyer, 1999). Lameness is localized at the foot and usually an abaxial sesamoid nerve block is necessary to improve the lameness, since the origin of the keratoma is generally at the toe (Redding, 2007; Eastman, 2015). The palmar digital nerve block can also improve lameness associated with the keratoma if the lesion is at the quarters, and can improve slightly a lameness originated in a toe region (Baxter et al., 2002; Redding, 2007). A unilateral palmar digital nerve block typically improves lameness associated with keratoma at the quarters in the affected side (Ross and Dyson, 2003; Redding and O’Grady, 2012).

1.8.2 Radiography

Standard 65-degree dorsopalmar views are useful to identify the lesion (Redding, 2007; Redding and O’Grady, 2012). Typically keratomas are seen on a dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique view; additional oblique views may be required for better visualization (Butler et al., 2000) such as: dorsolateral-palmaromedial oblique or dorsomedial-palmarolateral oblique views (Ross and Dyson, 2003).

The lesions are more easily seen at the solar margin of the pedal bone (Butler et al., 2000). In most cases, the mid or distal aspect of the dorsal surface of the distal phalanx is involved (Farrow, 2006).The classic radiographic image of a keratoma (figure 6) is a smoothly demarcated radiolucent defect in the solar margin of P3 (Butler et al., 2000; Little and Schramme, 2007; Eastman, 2015).

Figure 6 – Radiographic image of P3. Dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique view. Soft tissue defect in the midline and half-moon defect on P3. Classical image of

9 A keratoma can not be seen itself because it has the same radiodensity as the surrounding horn (Schramme and Labens, 2013). Deep bone cavitation with associated cortical thinning and expansion resembling a bone cyst are often present (Farrow, 2006). In more advanced cases a circular lytic area, often with sclerotic borders, can be recognized (Fürst and Lischer, 2006).

The bone underlying the keratoma is frequently sclerotic which differentiates it from pedal bone infection (Butler et al., 2000). Usually there is no new bone formation associated with the lesion, unlike other tumours that are associated with remodelling of adjacent bone (Butler et al., 2000). When the keratoma involves the solar margin is often mistaken by osteomyelitis or by localized bone reabsorption secondary to hoof abscess (Farrow, 2006).

Care must be taken to differentiate the toe lesions from the notching (crena marginalis) that occurs at the centre of the tip of P3 in numerous normal horses (Moyer, 1999; Ross and Dyson, 2003).

In some cases, keratomas are an incidental finding on a radiographic study (Moyer, 1999). On the other hand, the absence of radiographic findings does not rule out the possibility of keratoma (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). In a study by Anderson, (2013) radiographs failed to reveal keratomas in half of the cases (5/10) and in another study by Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012) 28% of horses had radiographs with no notable abnormalities but subsequently had a keratoma diagnosed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

1.8.3 Other methods

Lesions are not always appreciable on radiograph, so other diagnostic methods can be used, such as: ultrasound at the coronary band, nuclear scintigraphy, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging.

Ultrasonography of the keratoma has been reported and a hypoechoic, well-delineated soft tissue mass between the hoof wall and the articulation of the distal and middle phalanx has been described (Reef, 1998; Baxter et al., 2002). Ultrasound can not differentiate keratoma for other neoplasm formations (Rowland et al., 2016) and it’s main disadvantage is the limitation to tissues at the level of the coronary band (Mair and Linnenkohl, 2012).

If there is doubt in the clinical significance of the radiographic findings, nuclear scintigraphy may be helpful because such lesions usually are associated with focal increased uptake of radiopharmaceuticals due to bone remodelling (Ross and Dyson, 2003; Redding and O’Grady, 2012).

Another way to delineate the margins of a keratoma is a digital venogram that uses contrast radiography to assess the vascular status of the foot. This procedure can be done standing

10 under sedation, combined with an abaxial sesamoid nerve block. The contrast used is diatrizoate meglumine (Rucker, 2010).

Keratomas can be adequately evaluated with both CT and low field MRI. MRI is used more often because it is more readily available compared to CT, but it has been shown that CT is more sensitive at detecting boundaries of keratomas (Perrin et al., 2011; Rowland et al., 2016). On MRI, keratomas are showed as a mass similar to the keratinised hoof wall (Turner, 2016) with a hypointense or heterogeneous mixed signal intensity both in T1 and T2 and weighted images and hypointense in STIR sequences (Mair and Linnenkohl, 2012). According to Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012) most keratomas present a rounded outline and in only some cases the outline is irregular. It should be taken in account that the appearance of a hypointense signal void within the hoof wall may be confused with the artefact produced by magnetic susceptibility effects from metal fragments from the shoes and clenches. Because of inadequate water content, the hoof capsule is not evident on MRI images and the attachment of the keratoma to the hoof capsule can not be reliably identified (Getman, Ross and Richardson, 2011).

On CT scans, the lesion appears as a mass originating from the hoof wall, which is isoattenuating to the hoof wall and causes a semi-circular region of osteolysis in the adjacent distal phalanx (Porter and Werpy, 2014). According to Getman, Ross and Richardson, (2011) CT requires less technical skill to acquire images and repeat imaging once the markers are in place, and is also quicker than MRI. The biggest disadvantage of CT is the risks of general anaesthesia. CT of the limbs can be done standing, but is not available everywhere and there has to be a rigorous case selection because it bears a big risk to the equipment (Debrosse et al., 2008). Contrast enhanced computed tomography could also be used, since it allows comprehensive characterisation of keratomas, determining: location, vascularization and evolvement extent of lamina and pedal bone affected. Contrast accumulation is related to hypervascularity and contrast attenuation at the lesion suggests compression of the vasculature, lesions with compression of vascularity are expected to take more time healing (Anderson, 2013).

Both CT and MRI allow the exact location of the defect to be determined (Porter and Werpy, 2014); both methods might also be useful for surgical guidance to the approach of the keratoma, especially if the location is not easily detected. They can be used to identify surgical landmarks before the removal of the defect, facilitating surgery and reducing anaesthetic time (Redding, 2007; Perrin et al., 2011; Eastman, 2015), this way the post-operative recovery time can be shortened (Getman, Ross and Richardson, 2011).

Diagnostic is made presumptively based on the clinical signs, but only histological evaluation can confirm the diagnosis of keratoma and rule out other conditions (Eastman, 2015).

11

1.9 Treatment

1.9.1 Conservative

The conservative treatment consists in trimming the hoof and good hygiene. In early stages the extremity of the lesion is pared to relieve pressure by the shoe; this measure is only palliative and does not stop the keratoma from growing (Hickman, 1985).The effects of conservative treatment are temporary because it is not always possible to prevent the formation of hoof abscesses, and it consists of meticulous hoof care and good hygiene (Fürst and Lischer, 2006).

1.9.2 Surgical

An early surgical approach is advised (Fürst and Lischer, 2006). The surgical removal of the lesion with the debridement of all the abnormal tissue and removal of the areas with secondary infection is the treatment of choice (Redding, 2007; Eastman, 2015). The removal of the abnormal growth has to be complete, otherwise incomplete removal frequently results in a high incidence of recurrence; in all cases a tourniquet placement at the level of the fetlock is advised (Baxter et al., 2002). After surgical removal, histopathology is highly recommended to confirm if the mass is a keratoma (Rowland et al., 2016).

Two methods of gaining access to the abnormal tissue have been described (Baxter et al., 2002; Honnas, 2011), total or partial resection of the lesion: the partial resection is the preferred technique because hoof wall stability can be maintained, there is less complication rate and shorter convalescent time according to a study made by Boys Smith et al., 2006.

1.9.2.1 Total Resection

In this method a hoof wall flap is created by making two parallel vertical cuts into the hoof wall down to the sensitive laminae on either side of the keratoma, a third cut is made distally at the base of the mass and a final cut can be made proximal to the mass (figure 7). A motorized burr, a cast cutting saw or an osteotome can be used to make the cuts. The hoof wall is then gasped distally and reflected proximal to expose and remove the abnormal lesion (Baxter et al., 2002). The keratoma is usually easy to excise from the underlying corium; if the lesion has caused reabsorption of the bone, the third phalanx should be curetted and any discoloured surrounding soft tissue should be debrided (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). During all the procedure care should be taken not to damage the coronet band. After the mass is removed the soft tissue and bone are debrided in order to leave healthy margins (Baxter et al., 2002).

12 Although with worse prognosis than the partial resection, there is a report by Greet, (2016) in which a radical resection (figure 8) was made because the horse had 3 lesions within the hoof capsule and it recovered completely after 7 months, which supports that the surgical technique should be chosen upon the clinical findings (Boys Smith et al., 2006)

Figure 7 - Total Resection of a keratoma. Adapted from Smith et al., 2006

Figure 8 - Radical resection of multiple keratoma lesions. Adapted from Greet, 2016

13

1.9.2.2 Partial Resection

Aggressive hoof wall resection extending from just below the coronary band distally to the solar surface has traditionally been the procedure of choice. But retrospective investigation reveals that a smaller or partial resection (figure 9) greatly reduces the complications and horses return to full work faster.

This approach is created through the hoof wall overlying the keratoma: radiographic guidance can be used to determine the optimum approach, but CT or MRI are the best methods to determine the exact location of the lesion. By using this guidance we can guarantee less complications and more precision as mentioned before (Redding, 2007; Eastman, 2015). The affected area should be curetted until the tissue surrounding the defect is healthy, to reduce the incidence of recurrence (Honnas, 1997; Eastman, 2015).

Some authors defend the creation of a second window (figure 10) at the solar surface if a partial resection is preformed, improving access to the keratoma and allowing ventral drainage (Eastman, 2015). This second window can be created with a Dremel tool or a trephine. The Dremel tool can be used to access and remove the entire keratoma (Redding, 2007).

The disadvantage of this method is that the location of the keratoma must be documented. This can be done by gross observation and confirmed by radiographic documentation with metal objects used as markers; the major advantage of this approach is relative lack of disruption of the hoof wall. Additional stabilization of the hoof wall is usually unnecessary (Baxter et al., 2002).

Figure 9 - Window for partial resection of keratoma. Image kindly provided by the University of Gent

14 In some instances it is necessary to approach the keratoma from the sole, though this approach may cause excessive granulation tissue and pain as complications (Moyer, 1999). Supracoronary approach for the removal of keratoma has been described in a case report by Gasiorowski et al., (2011). This technique maximises post-operative hoof wall integrity, but has only been described in masses located more proximal rather than distal. This case report suggests it can be used in any hoof keratoma, but there is not a lot literature describing it yet.

1.9.3 Anaesthesia

The resection of the hoof wall may be performed standing (under regional anaesthesia and sedation) or under general anaesthesia (Baxter et al., 2002; Eastman, 2015), this decision should be made according to the patient’s temperament and extent of the lesion (Baxter et al., 2002).

In the standing procedure, anaesthesia of the foot is provided by blocking the palmar or plantar digital nerves at the abaxial level of the proximal sesamoid bones; 3 - 4ml of local anaesthetic are injected on either side of neurovascular bundle that can be palpated along the abaxial border of the proximal sesamoid bones. The efficiency of the anaesthesia should be check with a hoof tester (Moyer, 1999; Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003; Moyer, Schumacher and Schumacher, 2007).

Figure 10 - Partial resection of keratoma with solar window. Image kindly provided by the University of Gent.

15 In both procedures the foot is prepared as an aseptic surgery using the standard techniques, haemostasis is achieved by wrapping a roll of vetrap or a tourniquet firmly around the fetlock joint to compress and occlude the palmar digital arteries against the proximal sesamoid bones (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003).

The advantages of performing the removal under general anaesthesia are a more comfortable position for the surgeon and the immobility of the patient (Fürst and Lischer, 2006).

1.9.4 Bandaging

At the end of the excision the foot should be wrapped in a sterile bandage in such way as to make the bandage impervious to environmental contamination (Baxter et al., 2002). The bandage should be changed the day after the surgery and the site should be inspected for residual necrotic tissue. The resected defect should be packed with gauze sponges to improve comfort. These gauze sponges can be soaked in antiseptic and antimicrobial solutions (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003), such as diluted povidone iodine, gentamicin sulfate or metronidazole (Rowland et al., 2016). If the bone underlying the keratoma has been exposed, iodine should not be applied until a healthy bed of granulation tissue has covered the bone (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). After having granulation tissue, gradually increasing the concentration of iodine applied to the surface of the defect may be used to enhance cornification (Baxter et al., 2002).

The bandage should be changed every 3-4 days (Fürst and Lischer, 2006). The foot should remain bandaged for 3-4 weeks until cornification of the exposed corium is complete (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). If a substantial amount of hoof wall is removed, hoof casts can also be used to guarantee stability (Rowland et al., 2016).

1.9.5 Post-Operative care

During the first week after surgery, phenylbutazone is usually indicated to relieve the pain that results from the hoof wall removal. The horse should be confined to a stall for 4-6 weeks in early post-operative period (Fürst and Lischer, 2006), followed by gradually increasing the exercise amount (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). Antibiotics are generally not necessary because infection does not typically accompany the keratoma (Turner, 2016). Some authors defend regional limb perfusions with 2–2.5 g amikacin during surgery and post operatively for 3–4 days (Rowland et al., 2016).

Complications include the formation of exuberant granulation tissue at the resection site, hoof wall instability, recurrence and hoof cracks. By doing a partial resection instead of a complete resection this complications are greatly reduced, as referred before, and these horses need less time to recover to complete work. In case of secondary infection, a regional limb perfusion

16 with antimicrobials should be performed, with a tourniquet at the level of the fetlock. Depending on the grade of secondary infection, continued systemic and local antibiotics can sometimes be indicated (Eastman, 2015).

1.9.6 Shoeing

After the removal of a keratoma the shoes applied should have wide branches for support and a light bar to prevent movement of the shoe. The hoof will grow at a faster rate than the others so a generous and long shoe should be placed to prevent the hoof from shifting from it (Van Nassau, 2007).

If an extensive resection of the hoof wall is done, it can create great instability at the proximal margin. The hoof should be stabilized with a shoe with wide clips on either side of the resected defect. A small metal plate bridge (figure 11) can be placed to provide stability, and let the hoof grow out, when it reaches the distal region it should be removed. A shoe without clips can be placed once the proximal portion of the resected defect grows out to the hoof surface (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003; Eastman, 2015).

If the hoof wall resection extends proximal towards the coronet, a metal strip that spans the defect can be attached to the hoof wall within 6,35 mm to 9,50 mm sheet metal screws to further stabilize the foot. Without this, the proximal portion of the resected hoof may become unstable, resulting in the development of exuberant granulation tissue and pain. The screws

Figure 11- Metal bridge to provide stability after resection. Available in: http://www.hendersonequineclinic.com/pictures/keratoma/

17 can be covered with hoof acrylic to prevent them from backing out. The metal strip is left in place as the hoof grows and reaches the weight-bearing surface. The shoe is to be changed every 6-8 weeks (Baxter et al., 2002).

The stabilizing shoe should be maintained until the hoof defect has grown out distally in the hoof wall. This process occurs generally over a period of 6-12 months. Stall rest is recommended until the hoof defect is healed enough to allow hoof reconstruction that can be done with polymethylmethacrylate resin (PMMA) that may allow for a faster return to performance. The acrylic is applied when the exposed laminar tissue is completely cornified and there is no evidence of lameness or radiographic changes in the defect (Baxter et al., 2002; Redding, 2007). Alternatively to waiting for cornification to reconstruct the defect, antibiotic-impregnated PMMA can be used to repair fresh hoof wall defects, thereby avoiding the delay required in allowing the defect to cornify (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003).

1.10 Prognosis

For a successful resolution, the keratoma must be completely removed up to its origin and support has to be given in the hoof wall. The prognosis of the surgical treatment is significantly better than the conservative treatment (Fürst and Lischer, 2006). With the complete removal of the affected tissue and sufficient time for the defect to heal, the prognosis for full athletic use is excellent. According to Baxter et al., (2002) there was a study in which 6 of 7 horses were sound 1 year after the surgery with no recurrence of keratoma. Adequate stabilization of the hoof defect and complete removal of the lesion are the most important factors for the outcome (Baxter et al., 2002). Besides recurrence horses may also develop chronically abnormal hoof wall formation or third phalanx osteomyelitis (Moyer, 1999).

Recurrence was not registered 1-11 years following resection with wide margins, but it may follow incomplete excision. This incomplete excision is particularly likely at the coronary band, where there is concern regarding permanent damage of the coronary corium (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). The rate of recurrence is relatively high, but it is not certain whether it is a result of failure to remove the entire lesion or genuine recurrence (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a). Recurrence is more likely in ill-defined keratomas (Mair and Linnenkohl, 2012).

18

2 Objectives

The present study has the main goal of evaluating the particularities of keratoma lesions in a group of animals, in particular the outcome of the keratoma partial resection. Other

objectives are:

To study the causes and development of keratoma lesions; To study the epidemiology of keratoma lesions;

To identify the most common clinical signs of a keratoma lesion;

To relate the clinical history and clinical signs with the presence of a keratoma lesion; To evaluate the radiographic characteristics of a keratoma;

To recognize a radiographic image of a keratoma;

To study the therapeutic options if a keratoma lesion is diagnosed; To evaluate the outcome of the treatment;

19

3 Material and Methods

This study was done at the Gent University Equine Hospital in Gent, Belgium from September to December 2016. Only horses diagnosed and treated for keratoma and keratoma-like lesions that were already out of hospitalization were included in this study. The medical records from 21 horses that were presented to the Gent University Equine Hospital (Faculteit Diergeneeskunde Merelbeke) between 2008 and 2016 were reviewed. Of these 21 cases, some were accompanied during the externship.

The following information was collected: age, breed, season of diagnostic, history; affected leg, grade of lameness, presence of digital pulse, region of the hoof affected, clinical findings, radiographic findings; type of anaesthesia; treatment procedure; complications, and days of hospitalization

3.1 Evaluation of the case

After arriving at the hospital an anamnesis and a complete clinical exam were performed. Information about the actual condition and clinical history of the horses was collected in order to point the clinicians to a diagnostic path.

A complete clinical exam was made before exploring the hoof. All the parameters were taken: temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, respiratory sounds, cardiac sounds, gut sounds in all quads, lumbar reflex, skin twitch, evaluation of both jugular ingurgitation, palpation of sub -mandibular lymph nodes, presence of eye or nose discharge, colour of the mucous membranes, and capillary refill time.

After the clinical exam the hoof was examined by observation and using the hoof testing forceps. A lameness examination was performed both on hard and soft surfaces.

In the radiographic study, the projections used were the lateromedial (LM) combined either with the dorsopalmar (DP) or with the dorso-proximal palmaro-distal oblique with 55º (D55Pr-PaDIO).

After the confirmation that there was a keratoma or keratoma-like lesion the decision of excision with regional anaesthesia or general anaesthesia was made according to the temperament of the horse and the size of the lesion.

3.2 Keratoma excision

The excision was made by cutting out the defect with a hoof knife and if then drilling it out from the top to the bottom creating a tunnel and always maintaining a distal bridge of the hoof wall. A tourniquet on the leg was used to decrease the bleeding so that the surgeon had a better view.

20 As said before, this procedure was made under sedation or under general anaesthesia, depending on the case. If made under general anaesthesia the horse is submitted to a pre-anaesthetic exam.

The horse was pre-medicated with:

Romifidine: 80µg/kg

Morphine: 0,1 mg/kg

Flunixin meglumine: 1,1 mg/kg

Sodium Penicillin: 10 million I.U.

Induced with:

Diazepam: 0,06 mg/kg

Ketamine: 2,2 mg/kg

The anaesthesia was maintained with isoflurane.

During the procedure the following drugs were administered:

Anti-tetanus serum: 3mL

Procaine penicillin: 5ml/100kg

If the procedure was made under regional anaesthesia and sedation, the following sedation was administered:

Detomidine: 10-20 µg/kg

Butorphanol 10-20 µg/kg

Then the tourniquet was applied and the abaxial block performed with 2,5-5 ml of Mepivacaine for each nerve.

Generally when removing the lesion a distal bridge of hoof was left to provide stability, even when that part of the hoof was unhealthy, it would be trimmed later in a control. Iodine impregnated gauze sponges were placed at the defect and a sterile bandage would be placed to cover the hoof. In this hospital, a cast was placed in most of the cases to prevent hoof instability, only in very simple cases was a bandage placed.

21

3.3 Postoperative care

The cast was left for 3 days and then taken out for a control and replaced, changed every 5 days for the first 4 weeks. Afterwards a cast control was done after 3-4 weeks; in every control it is checked if the tissue was popping, if there were signs of infection and lameness.

All the horses were in absolute rest for 3 weeks and under antibiotic treatment, trimetroprim-sulfadiazine BID for 12 days and phenylbutazone was administered according to the comfort level of each horse.

After removing the cast, the horses stay in a dry and clean stable for 10 days, if stable rest was impossible they could be housed in a paddock but with limited space.

3.4 Follow-up

Follow-up information was obtained by telephone questionnaire to the owners. The objective was to obtain information about: horse activity, type of housing, type of shoeing; time of recovery to performance, level of performance after recovery, conformation of the hoof and time of hoof growth, recovery complications and time/existence of recurrence.

The following questions were made:

-What was the use of the horse?

-Was the horse in the pasture or in the stable before the lesion? -What was the type of shoeing before the procedure?

-Did the horse get back to the previous level of performance? -How much time did the horse take to fully recover?

-Was there any history of hoof problems before the lesion? Which ones?

-Did the keratoma ever come back? If yes, was it treated? How much time passed between the treatment and the recurrence?

-Was the hoof conformation normal after the procedure? -How much time did the hoof take to fully regrow? -Were there any complications on the recovery?

22

4 Results

4.1 General characteristics

During the period of study, 29 horses were diagnosed with keratoma or keratoma like lesions, but only 21 could be included. The other 8 could not be included due to the fact that 3 were euthanized before the treatment, mainly for economic reasons, 2 were not included in the study because access to the records or contact to owners was not allowed/available, and 3 cases were followed but could not be included in this study since they were still in treatment at the hospital.

From the 21 horses included in this study 11 (52%) were geldings and 10 (48%) were mares, there were no stallions. Eight keratomas (38%) were diagnosed over spring period, 6 (29%) during autumn, 4 (19%) during winter and 3 (14%) cases were diagnosed during summer. The most common breed found was the BWP Warmblood with 8 horses. There were other Warmblood horses: 2 SBS Warmbloods, 1 SF Warmblood, 1 KWPN Warmblood and 1 Holstein Warmblood. There was also 1 Quarter Horse, 1 Pony, 1 Paint Horse, 1 Gypsy Horse, 1 Irish Cob, 1 White Marble Horse (Boulonnais) and 2 mixed breed horses. This can be translated into 13 Warmblood breed horses, 3 Draft Horse breed and 5 from other breeds. Only 14 horses had a register of weight, with a mean of 530kg raging from 718kg and 411kg. The age range was from 3 to 27 years with a mean of 10,5 years (table 1).

Table 1 - Weight in kilograms and age in years

Weight (n=14) Kg Age (n=21) Years

Maximum 718 Maximum 27 Median 520 Median 9 Mean 530 Mean 10,5 Minimum 411 Minimum 3 4.2 Clinical Results

4.2.1 History

After reviewing the history of all the cases, 8 horses had hoof abscess history, 3 hoof cracks, 1 white line disease, and another one bad hoof conformation. The rest of the horses (n=6) presented a combination of hoof conditions: 2 had hoof abscess associated with laminitis, 1 had hoof abscess, abnormal conformation and surgical intervention to the hoof, another one had white line disease associated with surgical intervention to the hoof, another one had hoof abscess and also had surgical intervention to hoof and the last one had a hoof abscess

23 associated with a hoof crack. Two other horses in this study had no history of hoof related diseases, only sudden lameness was reported (graphic 1).

Graphic 1- summary of the clinical history of the horses included in this study, the red part (29%) includes all the horses that had more than one hoof condition combined.

4.2.2 Clinical Findings

Lameness was observed in 13 horses: 9 while trotting in the straight line (SL) and 4 presented severe lameness (present at walk). Eight of the cases in this study didn’t present any kind of lameness.

Digital pulse was present in 10 of the horses and absent on 3, but only registers for 13 cases were available. It is important to highlight that 2 horses presented digital pulsation but no lameness.

In each case only one foot was affected. The majority was on the front limbs, where 14 cases were registered, 9 on the right and 5 on the left. The other 7 cases were at the hind limbs, 3 on the right and 4 on the left. The toe region was the more affected with 19 cases and only 2 cases at the lateral quarter.

Associated with keratoma, clinically 9 cases presented a fistula with pus, 4 a defect with drainage, 4 hoof cracks, one of them full length, 2 abnormal hoof conformation, 1 abnormal hoof conformation with a fistula and, the last one, collateral leg edema.

The table 2 makes a summary of clinical findings:

5% 29% 38% 14% 9% 5%

HISTORY

Bad conformation (isolated) Combination

Hoof abcess (isolated) Hoof Cracks (isolated) Sudden Lameness

24

Table 2 – relation between the clinical findings and the location of the lesions

Affected leg Clinical findings Right Front Left Front Right Hind Left Hind Total

Fistula with pus 2 2 1 4 9

Defect with drainage 2 2 4

Hoof crack 3 1 4

Abnormal conformation 2 2

Contralateral leg edema 1 1

Abnormal hoof conformation and fistula 1 1

Total 9 5 3 4

After analysing table 2 it is possible to say that the majority of fistulas had occurred in the hind limbs (n=5 + 1, the fistula associated with abnormal hoof conformation), but there were still 4 fistulas at the fore limbs. Hoof cracks (n=3), defects with drainage (n=4), and abnormal hoof conformation (n=2) only occurred in the fore limbs. Contralateral edema of the leg was registered only in one case at the right hind as well as an abnormal hoof conformation associated with a fistula.

4.3 Radiographic Results

There were 5 cases in this study that were diagnosed just by taking into account the clinical findings within the hoof. The other 16 did a radiographic study; of these 16 horses 2 of them did not present radiographic abnormalities regarding keratoma lesions. The most common finding was osteitis of the coffin bone in 5 cases, followed by the presence of a midluscent zone in the coffin bone in 3 cases. The semilunar defect at the dorsal hoof wall was present in 2 horses and the other findings only in one horse each (graphic 2).

25

4.4 Treatment proceedings

One of the cases in this study did a conservative treatment.

Regarding the excision, 11 horses did the procedure under general anaesthesia and 9 under regional anaesthesia combined with sedation.

The time of hospitalization varied according to the needs of each patient. The longest hospitalization was of 80 days and some horses did not need to stay at the hospital after the procedure. The average time for hospitalization was of 22 days (table 3).

Table 3 – Days of hospitalization

Days of Hospitalization

Maximum 80d

Mean 22d

Median 18d

Minimum 0d

The majority of the cases (n=17) did not present any complications after the procedure or during hospitalization. There were 2 cases that developed an abnormal hoof conformation during hospitalization and 2 had recurrence when hospitalized and the keratoma had to be excised again. 31% 13% 19% 6% 6% 6% 6% 13%

Radiographic Findings

Osteitis of the coffin bone.Semilunar defect in the dorsal hoof wall Midluscent zone in the coffin bone Depression of the lateral palmar process Fistular tract in the dorsal hoof wall Semilunar defect in the dorsal hoof wall and irregular coffin bone

Midluscent zone in the coffin bone and hoof cracks

No significant radiographic abnormalities regarding keratoma lesions

26

4.5 Questionnaire results

From the 21 horses included in the present study, only 12 questionnaires had answers. The remaining owners were either not available to answer the questions, did not want to, or it was not possible to reach them. Of these 12 horses, one changed owner before the keratoma treatment recovery was complete and the other was euthanized during the treatment (by recurrence). For both these 2 horses the outcome questions could not be answered.

4.5.1 General characteristics

The majority of horses were used for recreational activities with 8 cases, 3 were jumpers, and 1 breeding mare.

The access to both pasture and stable was the preferred housing for a total of 6 horses, followed by exclusively in the pasture with 4 horses. Only 2 of the horses in this study were exclusively in the stable.

The majority of the horses had a normal shoeing (n=8), 3 of them were not shoed, and one used only front shoes.

4.5.2 Outcome results

Regarding the 12 horses with answers to the questionnaire, 2 of them could not answer the outcome questions, as mentioned before.

The majority of horses (n=8) returned to the level of performance that had before. Two horses were not sound anymore after the excision of the keratoma.

Half horses (n=5) kept a normal hoof conformation, but the other half (n=5) developed an abnormal hoof conformation.

Complications were mostly absent, only one owner reported bad behaviour because it was a foal and the recovery is made mainly through stable rest.

The time of recovery went from 3 months to 24 months with a mean time of 11 months. The time of hoof growth was very close to the time of recovery, ranging from 3 months to 24 months as well, with a mean time of 9 months (table 4).

Table 4 – Time of recovery and time of hoof growth in months

Time of recovery Time of hoof growth

Maximum 24m Maximum 24m

Mean 11m Mean 9m

Median 8,5m Median 6,5m

Minimum 3m Minimum 3m

27 There were 6 horses that presented recurrence of the keratoma lesion, 3 of them in the following year and the remaining, two, three and four years later (table 5).

Table 5 –Association between recurrence and foot affected

Right Front Left Front

Right Hind

Left Hind

Total

28

5 Discussion

The prevalence of keratomas in horses does not present any gender predisposition (Moyer, 1999; Eastman, 2015). In this study the number of geldings surpasses the number of mares, but just by one animal, which is in accordance with the bibliography. In the population of this study there were no stallions present. This can be explained by the majority of Warmblood stallions being castrated, if not used for reproductive purposes.

The age range of the cases observed was very wide, from 3-27 years, which points to no age predisposition for the appearance of keratoma lesions (Baxter et al., 2002; Eastman, 2015). Bibliography that supported any breed predisposition could not be found, but there were reports in various breeds including Warmblood lines and Draft horses. In this study the most prevalent breed was the BWP Warmblood and most horses were from a Warmblood line of breeding. This can probably be explained by the region were the data was collected, Flanders. Western Europe is the region were most Warmblood breeds were developed, and Flanders the region that breeds more BWP Warmbloods, so it makes sense that this is the most prevalent breed in the study.

History of recurrent abscesses is highly related with keratoma formation, and if it exists keratoma should be suspected (Turner, 2016). In a study by Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012) 47% revealed subsolar abscess history while in a study by Boys Smith et al., (2006) 85% horses had history of subsolar abscess. This study goes more in accordance with Mair and Linnenkohl, 2012 having only 38% of hoof abscess history. Although in the 7 horses with history of more than one hoof condition 3 had also hoof abscess, and if we take this horses into account then we have 52% of hoof abscess history. There was also history of other hoof insults such as: abnormal hoof conformation, hoof cracks, white line disease, and other combined conditions, that goes according with the bibliography where keratoma is caused by chronic irritation of the coronary band, dorsal laminae or solar corium (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015b).

According to the bibliography, some cases have developed keratoma without history of previous injury and with unknown initiating cause (Redding, 2007). The same happened to 9% of the horses in this work that only had history of sudden lameness, this result is similar to one by Boys Smith et al., (2006) where 12% had no history of hoof insult.

Regarding lameness, it can be present or absent in a keratoma and it may become progressively worse as the lesion grows (Redding, 2007). In this study, 19% of the cases presented severe lameness and 43% were lame when trotting on the straight line (hard surface). Also 38% of horses did not present any sign of lameness. This variety of lameness degrees agrees with the bibliography in which the degree or presence of lameness is dependent on the size and location of the lesion, and some horses can have the keratoma

29 without any signs of lameness (Redding, 2007). The percentage of horses that were not lame is much higher than in a study by Boys Smith et al., (2006) where in 4% keratoma was not a cause of lameness.

McDiarmid, (2007), has a case report of a keratoma of the frog where the digital pulse of the affected limb was increased. Also the presence of digital pulse is described in the presence of hoof abscess (Redding and O’Grady, 2012). The digital pulse was present in 10 horses in this work, which goes according the bibliography.

In this thesis 100% of the cases affected only one limb. There is a study by Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012), in which 95% cases were just in one leg. No other studies where found that report 2 keratomas affecting different hoofs in the same horse.

The most affected parts of the hoof are the toes and the quarters (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015b), which is supported by this study where all the cases are at the toe except two that are at the quarters.

Forelimb keratomas are more common according to Eastman, (2015). This also happened in this study, where 67% cases registered fore limb keratomas and only 33% hind limb ones. Of the fore limb keratomas, 64% where on the right and 32% were one the left. This numbers can be compared with the study of Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012) where 90% of the keratomas where at the forelimbs, 60% on the right and 40% on the left. And with another study by Boys Smith et al., (2006) in which 65% where in the front and 35% in the hind. We can conclude that for some reason right fore limb keratomas are the most prevalent.

Concerning clinical findings, the most common was a fistula with pus, which can be a more mature stage of a defect with drainage such as an abscess. Hoof cracks and abnormal conformation were also present. On case had contralateral edema of the leg, which has not been described in the bibliography, all the others had conditions related with hoof insult, agreeing with the bibliography mentioned before.

Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012) did a study were 66% of the horses had radiological evidence of a smoothly marginated area of lysis of the solar margin of P3 or pedal osteitis. While 28% showed no notable abnormalities. In the current study, 75% of horses presented radiographic findings that supported the suspicion of keratoma such as: a mildly lucent zone in the coffin bone, osteitis of the pedal bone, or a semilunar defect at the dorsal hoof wall. A fistular tract and a depression of the processus palmaris were also found each in 6% of the cases. Thirteen percent of the horses did not present significant radiographic abnormalities regarding keratoma lesions. Comparing these numbers with the previous study we had a lower quantity of cases without radiographic abnormalities, which is reported by Anderson, (2013) as much higher (50%) in his study. Our radiographic study was only done in 16 horses of a total of 21 of the population of the study.

30 One horse of this study did a conservative treatment and was one of the cases that didn’t answer the questionnaire, and it would be interesting to know what the outcome of this treatment was. The surgical removal of the lesion with the debridement of all the abnormal tissue and removal of the areas with secondary infection is the treatment of choice (Redding, 2007; Eastman, 2015). Every horse was subjected to a partial excision of the keratoma lesion which has been shown by Boys Smith et al., (2006) to have faster recovery and less complications compared to the until then traditional approach, the total excision. In this thesis, 11 horses did the procedure under general anaesthesia and 9 under sedation. General anaesthesia has the advantage of a better access and view for the surgeon as well as total immobilization of the horse while sedation combined with regional anaesthesia has lower risks for the horse (Fürst and Lischer, 2006). There is no bibliography that supports an outcome of improvement using either the anaesthesia.

While on hospitalization, 10% of the horses had to repeat the excision, recurrence can be due to the failure to remove the entire lesion (Knottenbelt, Patterson-Kane and Snalune, 2015a) and other 10 % developed abnormal hoof conformation, probably because of the use of casts. Still, comparing with Mair and Linnenkohl, (2012) in which 37% had more than one debridement, the recurrence during hospitalization is quite low.

There was no relation found between the activity, the housing, and the shoeing of each horse and the outcome of the treatment. In this study 80% of the horses returned to their previous level of performance which agrees with a case report mentioned by McDiarmid, (2007) in which 83% of the horses that underwent surgical treatment for keratoma returned to the same or higher level of performance.

There were no complications directly related to the keratoma in any case during the recovery at home. Only a foal developed bad behaviour due to stable rest following the procedure. This agrees with the bibliography, the partial resection greatly reduces the complications and horses return to full work faster (Boys Smith et al., 2006)

Although there were no complications, 50% of the horses in this study developed an abnormal hoof conformation, which could be from either having an abnormal conformation before (n=1) or for the prolonged use of the cast.

Regrowth of hoof wall may take 6-12 months (Honnas, Dabareiner and McCauley, 2003). In the study by Boys Smith et al., (2006) took 6-12 months to grow, while in this study it took a longer time in some cases, ranging from 3-24 months with a mean of 9 months. This can be related to temperature and humidity during the recovery time. The recovery time is related directly to the hoof growth, it also ranged from 3-24 months the average time was a bit longer, 11 months agreeing more with Boys Smith et al., (2006) where horses took 6-36 months to return to performance.

31 The recurrence rate was higher than expected in this study, where 60% of the horses showed recurrence in the 4 following years after the intervention. This numbers do not agree with the bibliography where 30% of recurrence is mentioned (with CT/MRI guidance) by Getman, Ross and Richardson, (2011) or by a study that didn’t found recurrence in 7 cases, 1-11 years after resection (McDiarmid, 2007). Boys Smith et al., (2006) reported 11% of recurrence, on 3 horses where 2 did a partial resection and 1 a complete resection. Histopathology could have been used to later verify if the removal was complete by examining the margins of abnormal tissue. The partial resection is more difficult, because there is less space in the hoof wall and a decreased visualization of the surgical site (Boys Smith et al., 2006) which can be an explanation for this study results.

The fact that this is a retrospective study of a rare condition on the horses hoof had the limitation of a small number of cases. Other authors such as Getman, Ross and Richardson, (2011) and Boys Smith et al., (2006) also faced this limitation. The few number of studies regarding the theme are also a limitation to compare the results.

Another limitation to this study was that not all the cases diagnosed with keratoma lesions during the time of the study were used, some cases were not used because access to information about the case was not possible. This cases could have relevant influence under the results of the study.

Finally, at the Gent University Equine Hospital in Gent there were no histopathologic analysis that confirmed that this were indeed keratoma lesions and without it we can’t prove that each space occupying lesions was indeed a keratoma.