www.rpped.com.br

REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Prevalence

of

excessive

screen

time

and

associated

factors

in

adolescents

Joana

Marcela

Sales

de

Lucena

a,c,

Luanna

Alexandra

Cheng

a,c,

Thaísa

Leite

Mafaldo

Cavalcante

b,c,

Vanessa

Araújo

da

Silva

b,c,

José

Cazuza

de

Farias

Júnior

a,b,c,∗aProgramaAssociadodePós-graduac¸ãoemEducac¸ãoFísica,UniversidadeFederaldaParaíba(UPE/UFPB),JoãoPessoa,PB,Brazil

bCentrodeCiênciasdaSaúde,UniversidadeFederaldaParaíba(UFPB),JoãoPessoa,PB,Brazil cGrupodeEstudosePesquisasemEpidemiologiadaAtividadeFísica---GEPEAF,JoãoPessoa,PB,Brazil

Received27January2015;accepted21April2015 Availableonline28August2015

KEYWORDS

Sedentarybehavior; Motoractivity; Obesity

Abstract

Objective: Todeterminetheprevalenceofexcessivescreentimeandtoanalyzeassociated factorsamongadolescents.

Methods: Thiswasacross-sectionalschool-basedepidemiologicalstudywith2874highschool adolescentswithage14---19years(57.8%female)frompublicandprivateschoolsinthecityof JoãoPessoa,PB,NortheastBrazil.Excessivescreentimewasdefinedaswatchingtelevisionand playingvideogamesorusingthecomputerformorethan2h/day.Theassociatedfactors ana-lyzedwere:sociodemographic(gender,age,economicclass,andskincolor),physicalactivity andnutritionalstatusofadolescents.

Results: Theprevalenceofexcessivescreentimewas79.5%(95%CI78.1---81.1)anditwashigher inmales(84.3%)comparedtofemales(76.1%;p<0.001).Inmultivariateanalysis,adolescent males,thoseaged14-15yearoldandthehighesteconomicclasshadhigherchancesofexposure toexcessivescreentime.Thelevelofphysicalactivityandnutritional statusofadolescents werenotassociatedwithexcessivescreentime.

Conclusions: Theprevalenceofexcessivescreentimewashighandvariedaccordingto sociode-mographiccharacteristicsofadolescents.Itisnecessarytodevelopinterventionstoreducethe excessivescreentimeamongadolescents,particularlyinsubgroupswithhigherexposure. ©2015SociedadedePediatriadeS˜aoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-license(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

DOIoforiginalarticle:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpped.2015.04.001

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:jcazuzajr@hotmail.com(J.C.FariasJúnior)..

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Comportamento sedentário; Atividademotora; Obesidade

Prevalênciadetempoexcessivodetelaefatoresassociadosemadolescentes

Resumo

Objetivo: Determinaraprevalênciadotempoexcessivodetelaeanalisarfatoresassociados emadolescentes.

Métodos: Trata-sedeumestudoepidemiológicotransversal,debaseescolar,com2.874 ado-lescentesde14a19anosdeidade(57,8%dosexofeminino),doensinomédiodasredespública eprivadanomunicípiode JoãoPessoa,PB.Otempo excessivodefoidefinidocomo assistir televisão,usarocomputadorejogarvideogamespormaisdeduashoraspordia.Osfatores associadosanalisadosforam:sociodemográficos(sexo,idade,classeeconômica,cordapele), práticadeatividadefísicaeestadonutricionaldoadolescente.

Resultados: Aprevalênciadetempoexcessivodetelafoide79,5%(95%IC:78,1---81,1)emais elevadanosexo masculino(84,3%)comparadocomofeminino(76,1%;p<0,001).Naanálise multivariada, verificou-seque osadolescentesdo sexo masculino, de14 a15 anosidade e aqueles quepertenciamàsclasseseconômicasmaisaltasapresentaram maioreschancesde exposic¸ãoaotempoexcessivo detela.Oníveldeatividadefísicaeoestadonutricionaldos adolescentesnãoseassociaramaotempoexcessivodetela.

Conclusões: A prevalência do tempo excessivo de tela foi elevada e variou com as carac-terísticassociodemográficasdosadolescentes.Faz-senecessáriodesenvolverintervenc¸õespara reduzirotempoexcessivodetelaentreosadolescentes,particularmentenossubgruposcom maiorexposic¸ão.

©2015SociedadedePediatriadeS˜aoPaulo.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteéumartigo OpenAccesssobalicençaCCBY(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.pt).

Introduction

Sedentarybehaviorsarelowenergyexpenditureactivities (≤1.5 metabolic equivalent--- MET), usually performed in a sittingor reclining position,including activities such as watchingtelevision, usingthe computer,sittingatschool, onthe bus,in acar,at work, talkingwithfriends,among othersimilaractivities.1Themeasureofthedailytimethat

adolescentsspendwatchingtelevision,playingvideogames andusingthecomputer,called screen time,isone ofthe most often usedmethods to assess sedentary behavior in studieswithadolescents.2

It isrecommendedthat children andadolescents dedi-catea maximum of2ha daytoscreen time.3 Thereport

fromtheHealth Behavior inSchool-Age Children(HBSC),4

carriedoutwithadolescentsaged11,13and15yearsfrom 41 countries in Europe and in North America, disclosed that56---65% of them spent 2h or moreper day watching television.DatafromtheNationalAdolescentSchool-based HealthSurvey (PeNSE),5 carried outwithninth-grade

stu-dents from public and private elementary schools in all BraziliancapitalsandtheFederalDistrict,showedthat78% ofthestudentsreportedwatchingtelevisionfor2hormore a day. A systematic review of studies withBrazilian ado-lescentsshowed that in 60% of the studies analyzed, the prevalenceofexcessivescreentimewasover50%.6

Studies onexcessive screen timeamongBrazilian ado-lescentshavebeenalmostalwaysperformedregardingtime spentwatching television,involving samples atyoung age groupsandusingdifferentcutpoints.7,8Moreover,inmost

cases, they were carried out in the south and southeast regions,reducinggeneralizationoffindings,6duetothefact

thattheseregionsareeconomicallymoredeveloped,which

promotes greater access to electronic devices (computer andInternetaccess),whichwouldstimulatetheadoptionof sedentarybehaviors.9TheNationalSampleSurveyof

House-holds(PNAD,2013),9showedthatinthesouthandsoutheast

regions the proportion of households with a computer is 52.9% and 56.5%, respectively, withInternet accessbeing present in44.6%and50.2% ofhouseholds,respectively. In theNortheast,thisprevalenceislower,with29.4%of house-holdswithacomputerand25.3%withInternetaccess.

Thehighprevalenceofadolescentsexposedtoexcessive screen time is a matter of concern because of its asso-ciation withseveral health problems, such as overweight and obesity, alterations in blood glucose and cholesterol, poorschoolperformance,decreasedsocialinteractionand lower levelsof physical activity.10---12 It isalso noteworthy

thefactthatexcessivescreentimeinadolescencecan per-sist into adulthood.13 However, the associations between

excessivescreentimemeasuresandoverweight/obesityin adolescentsarestillcontradictory.14,15Theseresultsmaybe

related tothe cut points usedto define excessivescreen time,aswellastheemployedmeasures(objectivevs. sub-jective),theagegroupsofadolescentsandtheseveralstudy designs(cross-sectionalvs.longitudinal).14,15

Regarding the possible influences of excessive screen time on the physical activity levels of adolescents, the dataarestillinsufficienttoconfirmthehypothesisthatthis behaviorsubstitutesthetimespentpracticingmoderateto vigorousphysicalactivity.11Whenidentified,theassociation

between excessive screen time and physical activity lev-elsofadolescentsshowstobeoflowmagnitudeandvaries accordingtothemeasureofphysicalactivityused.1,2

behaviors, particularly screen time, their distribution in sociodemographicstrata,aswellasscreentimeassociation withexcessbodyweightandphysicalactivitypracticelevel areimportantknowledgegapsthatneedtobefilled.Thus, thisstudyaimedtodeterminetheprevalenceofexcessive screentimeandtoanalyzeitsassociationwith sociodemo-graphicfactors,physicalactivitylevelandnutritionalstatus inadolescentsfromnortheastBraziliancity.

Method

Thisstudyispartofaresearchprojectcarriedoutin2009, entitled: ‘‘Physical activity level and associated factors amonghighschool adolescentsinJoãoPessoa, city,--- PB: an ecologicalapproach.’’ The target population consisted ofhighschoolstudents,aged14---19years,frompublicand private schools João Pessoa city,state of Paraiba, Brazil. To determinesample size,aprevalence of50%of 300min ormoreofmoderatetovigorousphysicalactivityperweek wasused,withamaximumacceptable errorofthree per-centagepoints,95%confidenceinterval,designeffect(deff) equaltotwoandadditionof30%tocompensatelossesand refusals,resultinginasampleof2686adolescents.

Sampleselectionwasperformedbytwo-stagecluster.In thefirststage,30highschoolsweresystematicallyselected, distributedproportionallybysize(numberofenrolled stu-dents),bytype(publicandprivate)andregionsofthecity (north,south,east,west).Inthesecond,135classeswere randomlyselected,proportionallydistributedbyshift (day-timeandnighttime)andhighschoolgrade(1st,2ndand3rd yearofhighschool).

Data collection occurred fromMay toSeptember 2009 and was carried out by a team of six Physical Education undergraduate students who had been previously trained and submitted to a pilot study. All information was col-lectedthroughapreviouslytestedquestionnaire,filledout bystudentsinclassandduringregularclasstime,following instructionsprovidedbythecollectionteam.

Sociodemographicvariablesanalyzedinthisstudywere gender, age in years (determined from the difference between date of birth and the data collectiondate, and categorizedas14-15,16-17and18-19year)and socioeco-nomicclass,determinedbythemethodologyoftheBrazilian AssociationofResearchEnterprises---ABEP,16which

consid-ersthepresenceofmaterialgoodsandsalariedemployeesin theresidence,aswellastheeducationalleveloftheheadof thehousehold.Thestudentsweregroupedinsocioeconomic classes A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2, D and E, and later re-categorizedas:classA/B(high),C(middle)andD/E(low).

Nutritional status was estimated by body mass index (BMI=bodyweight[kg]/height[m2]),basedonself-reported measures of body mass (kg) and height (cm). The criteria suggested by Cole et al. 17 were used to

clas-sify adolescents as ‘‘without excess body weight’’ (low weight+normal weight) and ‘‘with excess body weight’’ (overweight+obesity).

The sociodemographic variable measurement repro-ducibilitywashigh,withkappa()values≥0.89p<0,01.BMI showedanintraclasscorrelationcoefficient(ICC=0.95)and value=0.84fornutritionalstatus(withoutvs.withexcess bodyweight).

Excessivescreen timewasassessedbasedonthe mea-surement of mean daily time (hours/minutes) spent in front of television and playing videogames and/or using the computer, on weekdays and the weekend, during a typical or usual week. For the final result,the weighted meanwascalculatedfromthefollowing:summationoftime spentinsedentarybehaviorsonweekdays(Monday---Friday) multiplied by five, added to time spent on the weekend (Saturday or Sunday) multiplied by two. This result was divided by seven to obtain the mean number of hours a daythattheadolescentsspentonscreenactivities. Exces-sive screen time was defined as spending more than 2h per day in these behaviors.3 Screen time measurement

showed satisfactory levels of reproducibility (continuous measure [hours/day]---ICC=0.76; p<0,01; categorical mea-sure[≤2h/dayvs.>2h/day]---=0.52).

Physical activity was measured using a previously val-idated questionnaire (reproducibility---ICC=0.88; 95%CI: 0.84---0.91; validity---Spearman correlation=0.62; p<0.001; =0.59).18 The adolescents reported the frequency

(days/week) and duration (minutes/day) of moderate tovigorousphysicalactivitiespracticedintheweekbefore datacollectionforatleast 10min,consideringalistof24 activities,withthepossibilitytoadd twomoreactivities. Physicalactivitylevelwasdeterminedbyaddingthe prod-uctof timeby thefrequency of practicein each activity, resultinginascoreinminutesperweek.Adolescents who performed 300min or more of physical activity per week were classified as ‘‘physically active’’, and others, as ‘‘physicallyinactive’’.

Initially, descriptive statistics procedures (frequency distribution, mean, standard deviation and 95% confi-dence interval --- 95%CI) were used. The chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of adolescents showing excessive screen time as a function of sociode-mographic variable categories (gender, age, skin color, socioeconomicclass),levelofphysicalactivity(‘‘physically active’’and ‘‘physically inactive’’) and nutritional status (‘‘without excess body weight’’ and ‘‘with excess body weight’’).

Logistic regression was used to assess the association betweenexcessivescreentimeandsociodemographic varia-bles,level of physical activity and nutritionalstatus. The modelhadexcessivescreentimeasthedependentvariable (≤2h/day=0and>2h/day=1)andasindependentvariables: gender (female=1, male=2), age (14---15=3; 16---17=2, and 18---19 years=1), skin color (White=1 and non-White=2), socioeconomic class (class A/B=3, C=2, D/E=1), level of physicalactivity(physicallyactive=1;physicallyinactive=2) andnutritionalstatus(withoutexcessbodyweight=1;with excess body weight=2). In the adjusted analysis, all the independent variables were included in the model and thosewithp-value<0.20remained.The backwardmethod wasappliedtoselectvariablesin themultivariatemodel. TheHosmer---Lemeshowtest wasusedtoassessthemodel goodness-of-fit.

Table1 Sociodemographiccharacteristics,physical activ-ityand nutritional statusof highschool adolescentsfrom public and private schools of João Pessoa, northeastern Brazil,in2009.

Variables n %

Gender

Female 1653 57.8

Male 1206 42.2

Agerange(years)

14---15 1128 10.7

16---17 1438 50.0

18---19 308 39.3

Skincolor

White 930 32.5

Non-white 1929 67.5

Socioeconomicclass

AandB(high) 1161 45.8

C(middle) 1167 46.1

DandE(low) 205 8.1

Physicalactivitylevel

Physicallyactive 1444 50.2

Physicallyinactive 1430 49.8

Nutritionalstatus

Noexcessbodyweight 2321 86.8

Excessbodyweight 353 13.2

Results

Initially,atotalof 3477studentswereselectedto partici-pateinthestudy,but70werenotallowedbytheirparents or guardians or refused to participate,and 187 were not availableonatleast threevisits oftheresearchteam.Of the3220adolescentswhoansweredthequestionnaire,346 wereexcluded (231were<14 or>19yearsofage, 105did notinformtheage,5hadleftseveralunansweredquestions and5hadsometypeofphysicalormentallimitation).The finalsampleincluded2874adolescents,ofwhich57.8%were females,meanageof16.5±1.2years;54.2%wereofmiddle tolowsocioeconomicclass(C/D/E),50.2%werephysically activeand13.2%hadexcessbodyweight(Table1).

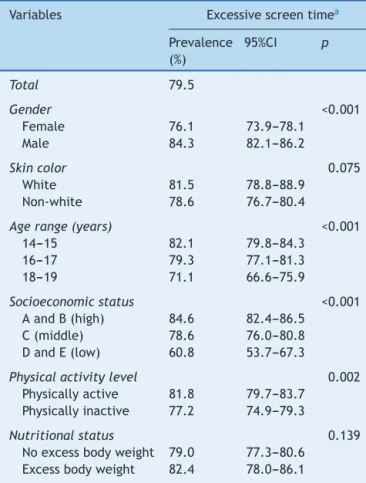

The prevalence of excessive screen time was 79.5% (95%CI: 78.1---81.1), being higher in males (p<0.001), in youngest(14---15years;p<0.001),thoseofhigher socioeco-nomicclass(p<0.001)andamongthephysicallyactiveones (p=0.002).Therewerenostatisticallysignificantdifferences between adolescentswith or without excess body weight (Table2).

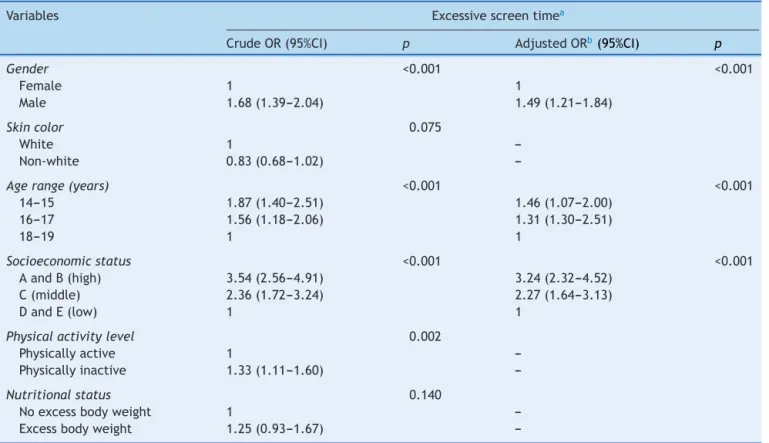

At the crude analysis(Table 3), excessive screen time wasassociatedwithgender, age,socioeconomicclassand levelofphysicalactivityoftheadolescents.Intheadjusted analysis, the level of physical activity lost statistical sig-nificance, while the other variables remained associated withexcessivescreentime.Maleadolescents,aged14---15 yearsandfromhighersocioeconomicclasses(classes A/B) had respectively 49% (OR=1.49; 95%CI: 1.21---1.84), 46% (OR=1.46; 95%CI: 1.07---2.00) and 224% (OR=3.24; 95%CI:

Table 2 Prevalence of excessive screen time and asso-ciatedfactors inhigh schooladolescents from publicand privateschoolsofJoãoPessoa,northeasternBrazil,2009.

Variables Excessivescreentimea

Prevalence (%)

95%CI p

Total 79.5

Gender <0.001

Female 76.1 73.9---78.1

Male 84.3 82.1---86.2

Skincolor 0.075

White 81.5 78.8---88.9

Non-white 78.6 76.7---80.4

Agerange(years) <0.001

14---15 82.1 79.8---84.3

16---17 79.3 77.1---81.3

18---19 71.1 66.6---75.9

Socioeconomicstatus <0.001 AandB(high) 84.6 82.4---86.5

C(middle) 78.6 76.0---80.8

DandE(low) 60.8 53.7---67.3

Physicalactivitylevel 0.002 Physicallyactive 81.8 79.7---83.7

Physicallyinactive 77.2 74.9---79.3

Nutritionalstatus 0.139

Noexcessbodyweight 79.0 77.3---80.6 Excessbodyweight 82.4 78.0---86.1

a WatchingTV,usingthecomputerandplayingvideogamesfor

morethan2h/day.

2.32---4.52) higherchance of exposuretoexcessivescreen time,comparedtofemales,olderadolescents(18---19years) and thosefrom thelower socioeconomicclasses (C/D/E). TheresultoftheHosmer---Lemeshowtest(2=8.26;p=0.22)

showedthattheconstructedmodelwaswelladjustedtothe data.

Discussion

In this study, the proportion of adolescents who showed excessivescreentimewashighandvariedaccordingtotheir sociodemographiccharacteristics.Higherchancesof exces-sivescreen timewerefound inadolescentmales,younger ones and those from the higher socioeconomic classes. Contrary to what has been speculated in the literature, excessivescreentimewasnotassociatedwithexcessbody weight and low levels of physical activity among adoles-cents.

This study showed that approximately 8 of 10 ado-lescents spent more than 2h a day on screen activities (television, computer and videogames). Similar results havealsobeenidentifiedinother national8,19 and

interna-tional studies.12,14,20 High prevalence of excessive screen

Table3 Crudeandadjustedanalysesfortheassociationbetweenexcessivescreentimeandassociatedfactorsinadolescents frompublicandprivateschoolsofJoãoPessoa,northeasternBrazil,2009.

Variables Excessivescreentimea

CrudeOR(95%CI) p AdjustedORb(95%CI) p

Gender <0.001 <0.001

Female 1 1

Male 1.68(1.39---2.04) 1.49(1.21---1.84)

Skincolor 0.075

White 1

---Non-white 0.83(0.68---1.02)

---Agerange(years) <0.001 <0.001

14---15 1.87(1.40---2.51) 1.46(1.07---2.00)

16---17 1.56(1.18---2.06) 1.31(1.30---2.51)

18---19 1 1

Socioeconomicstatus <0.001 <0.001

AandB(high) 3.54(2.56---4.91) 3.24(2.32---4.52)

C(middle) 2.36(1.72---3.24) 2.27(1.64---3.13)

DandE(low) 1 1

Physicalactivitylevel 0.002

Physicallyactive 1

---Physicallyinactive 1.33(1.11---1.60)

---Nutritionalstatus 0.140

Noexcessbodyweight 1

---Excessbodyweight 1.25(0.93---1.67)

---a WatchingTV,usingthecomputerandplayingvideogamesformorethan2h/day.

b Analysisadjustedbysociodemographicvariables,physicalactivitylevelandnutritionalstatus.

---Datashowednosignificantassociationafteradjustment(p>0.05).

suchaseconomic growththatallowedfamilies,especially middle---low income ones, to major access to television, computer,greateruseoftheInternetinleisuretime(e.g. interaction in social networks) and reduction of public spacesfor physicalactivities,combinedwiththeobserved lack of safetyin large urban centers. Astudy carried out between2001and2011withadolescentsaged15---19years inthestate ofSantaCatarinaobserveda reductionin the prevalenceofTVtimeandincreasedcomputer/videogame use.Thesechangeswereattributedtoeconomicchangesin Brazil,easieraccesstocomputers(Internetcafes,shopping malls, public places) and access to electronic media in general.21

In the present study, male adolescents were approx-imately 49% more likely to have excessive screen time, reinforcing findings of previous studies.7,8,19 One reason

forthishighprevalenceamongmaleadolescentsis mainly causedbyexcessuseofvideogamesandcomputer.20Studies

thatidentifiedahigherprevalenceofexcessivetimespent insedentarybehaviorsinfemalesmeasured,inadditionto screenactivities,thetimespenttalkingonthephone, lis-tening to music, doing homework, writing or talking.22,23

Anotherfactorthatmayexplainthesedifferencesisthecut pointusedtocharacterize excessivescreen time.14 A

sys-tematicreview6demonstratedthattheprevalenceresulting

fromtheuseofthecutpointof2hormoreoftelevisiontime washigherinmales,whilethatderivedfromthecutpointof

4hormorewashigherinfemales.6Culturalissuesmayalso

helptounderstand thesedifferences.Female adolescents aremoreencouragedtostayathomeforlongerperiodsand areraised withgreater careand todevote themselves to studiesandhouseholdchores.24 Thiswouldleadtogreater

prevalenceofsedentarybehaviors.

Increased exposure of adolescents to excessive screen timemayberelatedtotheadolescents’phaseof‘‘cultural definition’’.Upto14---15yearsold,mostoftheactivitiesare dividedbetweenschool,householdchoresandfriends.24At

thisphase,adolescentsfollowrulessetbytheirparents,who generallylimittheiractivitiestothehomeenvironment.24

Therefore,thesefactorscontributetotheincreaseduseof timeusingelectronicdevices,suchascomputer,videogames and watching television. These activities, in addition to beingamongtheformsofsocialinteractionofadolescents (throughsocialnetworks)arealsoadoptedbytheirgroups offriends, whichreinforces theadoption of these behav-iorsthroughthe social influence offriends.22 The greater

involvementwithexcessive screen timeat this agerange may indicate less social interaction and less restriction fromparentsaboutthetimespentusingcomputers,playing videogamesandwatchingtelevision.13 Anotherexplanation

activitieswouldlimitscreentimeor,logically,wouldreduce theinterestintheseactivities.

Thehigherexposureofadolescentsfromthehigher socio-economicclasses(A/B)toexcessivescreentimeobservedin thisstudymaybeassociatedwithagreaterchanceofthese adolescents having videogames and computer at home, especiallywithInternetaccess.DatafromtheNational Ado-lescent School-based Health Survey5 showed that among

students enrolled in the 9th grade of Elementaryschool, 95.5% of private school students had a computer (desk-top,netbook,laptop),comparedto59.8%ofstudentsfrom publicschools. This is supported bythe results thatwere foundincludingonlythetimespentwatchingtelevision.It wasobservedthat theadolescentsfrom classesD/Ewere more likely to watch television for more than 2h, when comparedtotheirpeersfromclassesA/B(OR=1.78;95%CI: 1.28---2.49 --- data not shown in table). These results are similartothosefound in other national studies that used themeasure of television timeasthe sedentary behavior outcome.7,8 Coombs et al. 25 observed that the

associa-tionbetween screen timeand socioeconomicclass varied according tothe type of sedentary behavior: adolescents fromlowersocioeconomicclasses spentmoretime watch-ingTVandlesstimeonothersedentarybehaviors,suchas doinghomework, drawing,using the computer or playing videogames.

It should be noted that even though this study used excessivescreentimeassedentarybehaviorindicator,the proportion of households in the state of Paraíba in 2009 that had a computer was small (19%) when compared to householdswithaTV(95.5%).26Thus,itispossiblethatthe

differences between the socioeconomic classes regarding thetypeofsedentarybehaviorassessedinthestudyresult fromthe higher access of adolescents from higher socio-economicclassestothecomputerandvideogames,while thosebelongingtothelowerclassesmayhavehigheraccess to television. Although television is still the most popu-larmeans ofentertainmentandleisure inallsocial strata and represents the largest share of screen time, future researchesshouldincludeothertypesofelectronicdevices, suchas theuse of cell phones and/or tablets,as well as Internetaccess,whicharelessfrequentinthepoorer socio-economicclasses.

Nosignificantassociationwasidentifiedbetweenexcess body weight and excessive screen time. Studies that observed a positive association between screen timeand excess body weight, in most cases, only measured the time spent watching television.27,28 A systematic review

of cross-sectional studies showed a positive association between screen time and excess body weight, but these associationswerenot identifiedin studiesusing objective measuresofsedentarybehavior.14Corroboratingthese

find-ings, a review of longitudinal studies published in 2011 concluded that there was evidence supporting the asso-ciation between screen time and excess body weight in adolescents.29 Theseresultsdemonstratethatthe

associa-tionof screentime andexcessweightcan varyaccording to the study design and used measure of sedentary behavior.

Oneexplanationfor the association between excessive screen time and excess body weight in adolescents may be related to increased consumption of unhealthy foods,

suchassoftdrinks,snacksandcandy infrontof the tele-vision and exposure to fast food ads, considering that televisionremainstheprimarymeansofcommunicationfor advertisements.30 These factorsinfluence foodintakeand

dietquality,resultinginapositiveenergybalanceand, con-sequently,increaseinbodyweight.11,27

The lack of a significant association between exces-sive screen time and physical activity levels identified in thisstudyis similartothatobservedin otherstudieswith adolescents.7,28 Physical activity and sedentary behaviors

are distinct constructs with ‘‘determinants’’, associated factors and specific health implications.2,12 In this

con-text, an individual can be physically active (i.e., meet the moderate to vigorous physical activity recommenda-tions) and still have excessive sedentary behavior time.1

Systematicreviewshavedemonstratedthattheassociation between sedentary behaviors and physical activity, when significant,showedverylowmagnitude,14,31andthat

inter-ventions to increase physical activity practice levels had no significant effects and, when they did, they showed low magnitude toreduce the timeobserved in sedentary behaviors.32,33

Martins et al. 28 found that correlated adverse

fac-tors for physical activity practice were not associated withsedentarybehaviorinadolescents.Theseresults sug-gest that excessiveexposure to sedentary behaviorsdoes not necessarily result from adverse conditions for phys-ical activity practice (lower perception of self-efficacy, less social supportand environments for physical activity practice).

This study has some limitations. The fact that self-reportedmeasures ofweightand heightwereusedis one of them, due to the possibility that the measures were underestimated,particularlyamongadolescentswithbody weight.However,self-reportedmeasureshavebeenwidely usedinstudiesoflargepopulation groups,andtheresults have shown tobevalid.34 Anotherlimitation wasthe fact

that data were not collected on the adolescents’ food consumption. Unhealthy eatinghabitsareassociatedwith sedentary behavior,aswell aswithexcess bodyweightin this population.11,30 The strengthsof thisstudy were: the

use of a representative sample of theadolescent popula-tionaged14---19yearsfrompublicandprivateschoolsinthe cityofJoãoPessoa,stateofParaíba,Brazil,andapowerto detectstatisticallysignificantoddsratiosequaltoorhigher than1.20andprevalenceofoutcomeintheexposedgroup rangingfrom20%to85%.Themeasureofsedentary behav-iorinvolveddifferentactivities,suchaswatchingtelevision, usingthe computerandplaying videogames,andnot only the time spent in front of the TV. The other strength of thisstudywasuseapre-testedquestionnairewith satisfac-torylevelsofreproducibility,appliedbyapreviouslytrained team.

Funding

Thisstudydidnotreceivefunding.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.PateRR,O’NeillJR,LobeloF.Theevolvingdefinitionof seden-tary.ExercSportSciRev.2008;36:173---8.

2.OwenN,HealyGN,MatthewsCE,DunstanDW.Too much sit-ting:thepopulation-healthscienceofsedentarybehavior.Exerc SportSciRev.2010;38:105.

3.CouncilonCommunicationsMedia.Children,adolescents,and themedia.Pediatrics.2013;132:958---61.

4.Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, et al. Social determi-nants of health and well-being among young people Health BehaviourinSchool-agedChildren(HBSC):internationalreport from the 2009/2010 survey. Health policy for children and adolescents, 6. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2012. p.1---252.

5.Brasil --- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [página na Internet]. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Esco-lar. IBGE; 2012. Available in http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/ estatistica/populacao/pense/2012/pense 2012.pdf [accessed on22.05.14].

6.BarbosaFilhoVC,CamposW,LopesAS.Epidemiologyof physi-calinactivity,sedentarybehaviors,andunhealthyeatinghabits amongBrazilianadolescents:asystematicreview.CienSaude Colet.2014;19:173---93.

7.Tenório M, Barros M, Tassitano R, Bezerra J, Tenório J, HallalP.Atividadefísicaecomportamentosedentárioem ado-lescentes estudantes do ensino médio. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13:105---17.

8.OliveiraTC,SilvaAA,SantosCJ,SilvaJS,Conceic¸ãoSI. Ativi-dade física e sedentarismo em escolares da rede pública e privada de ensino em São Luís. Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44:996---1004.

9.Brasil---InstitutoBrasileirodeGeografiaeEstatística[página na Internet]. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Síntesedeindicadoressociais;2013.Availableinhttp://www. ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/ indicadoresminimos/sinteseindicsociais2013/ [accessed on 20.05.14].

10.KangHT,LeeHR,ShimJY,ShinYH,ParkBJ,LeeYJ. Associa-tionbetweenscreentimeandmetabolicsyndromeinchildren and adolescents in Korea: the 2005 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:72---8.

11.SissonSB,BroylesST,BakerBL,KatzmarzykPT.Screentime, physical activity, and overweight in US youth: National Sur-vey of Children’s Health 2003. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47: 309---11.

12.TremblayMS,LeBlancAG,Kho ME, etal. Systematic review ofsedentary behaviourand health indicatorsin school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8: 98.

13.BiddleSJ,PearsonN,RossGM,BraithwaiteR.Trackingof seden-tarybehavioursofyoungpeople:asystematicreview.PrevMed. 2010;51:345---51.

14.Prentice-DunnH,Prentice-DunnS.Physicalactivity,sedentary behavior, and childhood obesity: a review of cross-sectional studies.PsycholHealthMed.2012;17:255---73.

15.TanakaC,ReillyJJ,HuangWY.Longitudinalchangesin objec-tivelymeasuredsedentarybehaviourandtheirrelationshipwith adiposity inchildrenandadolescents:systematic reviewand evidenceappraisal.ObesRev.2014:1---13.

16.Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeEmpresasdePesquisa(ABEP)[página naInternet].Critériodeclassificac¸ãoeconômicaBrasil. Avail-ableinhttp://www.abep.org/novo/Default.aspx[accessedon 12.05.12].

17.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standarddefinitionforchildoverweightandobesityworldwide: internationalsurvey.BMJ.2000;320:1240---3.

18.Farias Júnior JC, Lopes AS, Mota J, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC, Hallal PC. Validity and reproducibility of a physical activity questionnaireforadolescents:adaptingtheSelf-Administered Physical Activity Checklist. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2012;15: 198---210.

19.Dumith SC, Hallal PC, Menezes A, Araújo CL. Sedentary behavior in adolescents: the 11-year follow-up of the 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26:1928---36.

20.OldsTS,MaherCA,RidleyK,KittelDM.Descriptiveepidemiology ofscreenandnon-screensedentarytimeinadolescents:across sectionalstudy.IntJBehavNutrPhysAct.2010;7:92.

21.SilvaKS,LopesAS,DumithSC,GarciaLM,BezerraJ,NahasMV. Changesintelevisionviewingand computers/videogamesuse amonghigh schoolstudentsinSouthernBrazil between2001 and2011.IntJPublicHealth.2014;59:77---86.

22.SirardJR,BrueningM,WallMM,EisenbergME,KimSK, Neumark-SztainerD.Physicalactivityandscreentimeinadolescentsand theirfriends.AmJPrevMed.2013;44:48---55.

23.BauerKW,FriendS,GrahamDJ,Neumark-SztainerD.Beyond screentime:assessingrecreationalsedentarybehavioramong adolescentgirls.JObes.2012:1---8.

24.Gonc¸alves H, Hallal PC, Amorim TC, Araújo CL, Menezes AM. Fatores socioculturais e nível de atividade física no início da adolescência. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;22: 246---53.

25.CoombsN,SheltonN,RowlandsA,StamatakisE.Children’sand adolescents’sedentarybehaviourinrelationtosocioeconomic position.JEpidemiolCommunityHealth.2013:67.

26.Brasil---InstitutoBrasileirodeGeografiaeEstatística[páginana Internet].PesquisaNacionalporAmostradeDomicílios.Síntese de Indicadores Sociais; 2009. Available in http://www.ibge. gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/trabalhoerendimento/ pnad2009/pnadsintese2009.pdf2009[accessedon23.05.13]. 27.Carson V, Janssen I. Volume, patterns, and types of

seden-tary behavior and cardio-metabolic health in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:1---10.

28.MartinsMO,CavalcanteVL,HolandaGS,OliveiraCG,MaiaFE, Meneses Júnior JR. Associac¸ão entre comportamento seden-tárioefatorespsicossociaiseambientaisemadolescentesda região Nordestedo Brasil.Rev BrasAtivFisSaude. 2012;17: 143---50.

29.UijtdewilligenL,NautaJ,SinghAS,etal.Determinantsof phys-icalactivityandsedentarybehaviourinyoungpeople:areview andqualitysynthesisofprospectivestudies.BrJSportsMed. 2011;45:896---905.

30.BoulosR,VikreEK,OppenheimerS,ChangH,KanarekRB. Obe-siTV:howtelevisionisinfluencingtheobesityepidemic.Physiol Behav.2012;107:146---53.

32.Biddle SJ, Petrolini I, Pearson N. Interventions designed to reduce sedentary behaviours in young people: a review of reviews.BrJSportsMed.2014;48:182---6.

33.HardmanCM,BarrosMV,LopesAS,LimaRA,BezerraJ,Nahas MV. Efetividade de uma intervenc¸ão de base escolar sobre

o tempo de tela em estudantes do ensino médio. Rev Bras CineantropomDesempenhoHum.2014;16:25---35.