Lucas George Wiessing

Epidemiology of HIV and Viral Hepatitis among People Who Inject Drugs in Europe

Dissertação de candidatura ao grau de Doutor apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto

Artigo 48, parágrafo 3º: ”A Faculdade não responde pelas doutrinas expedidas na dissertação.” (Regulamento da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Decreto Lei nº 19337, de 29 de

Corpo Catedrático da Faculdade de Medicina do Porto

Professores Catedráticos Efectivos

Doutor Manuel Alberto Coimbra Sobrinho Simões Doutora Maria Amélia Duarte Ferreira

Doutor José Agostinho Marques Lopes

Doutor Patrício Manuel Vieira Araújo Soares Silva Doutor Alberto Manuel Barros Da Silva

Doutor José Manuel Lopes Teixeira Amarante Doutor José Henrique Dias Pinto De Barros

Doutora Maria Fátima Machado Henriques Carneiro Doutora Isabel Maria Amorim Pereira Ramos Doutora Deolinda Maria Valente Alves Lima Teixeira Doutora Maria Dulce Cordeiro Madeira

Doutor Altamiro Manuel Rodrigues Costa Pereira Doutor José Carlos Neves Da Cunha Areias Doutor Manuel Jesus Falcão Pestana Vasconcelos

Doutor João Francisco Montenegro Andrade Lima Bernardes Doutora Maria Leonor Martins Soares David

Doutor Rui Manuel Lopes Nunes

Doutor José Eduardo Torres Eckenroth Guimarães Doutor Francisco Fernando Rocha Gonçalves Doutor José Manuel Pereira Dias De Castro Lopes

Doutor António Albino Coelho Marques Abrantes Teixeira Doutor Joaquim Adelino Correia Ferreira Leite Moreira Doutora Raquel Ângela Silva Soares Lino

Professores Jubilados ou Aposentados

Doutor Alexandre Alberto Guerra Sousa Pinto Doutor Álvaro Jerónimo Leal Machado De Aguiar Doutor António Augusto Lopes Vaz

Doutor António Carlos De Freitas Ribeiro Saraiva Doutor António Carvalho Almeida Coimbra

Doutor António Fernandes Oliveira Barbosa Ribeiro Braga Doutor António José Pacheco Palha

Doutor António Manuel Sampaio De Araújo Teixeira Doutor Belmiro Dos Santos Patrício

Doutor Cândido Alves Hipólito Reis

Doutor Carlos Rodrigo Magalhães Ramalhão Doutor Cassiano Pena De Abreu E Lima Doutor Daniel Filipe De Lima Moura Doutor Daniel Santos Pinto Serrão

Doutor Eduardo Jorge Cunha Rodrigues Pereira Doutor Fernando Tavarela Veloso

Doutor Henrique José Ferreira Gonçalves Lecour De Menezes Doutor Jorge Manuel Mergulhão Castro Tavares

Doutor José Carvalho De Oliveira

Doutor José Fernando Barros Castro Correia Doutor José Luís Medina Vieira

Doutor José Manuel Costa Mesquita Guimarães Doutor Levi Eugénio Ribeiro Guerra

Doutor Luís Alberto Martins Gomes De Almeida Doutor Manuel António Caldeira Pais Clemente

Doutor Manuel Augusto Cardoso De Oliveira Doutor Manuel Machado Rodrigues Gomes Doutor Manuel Maria Paula Barbosa

Doutora Maria Da Conceição Fernandes Marques Magalhães Doutora Maria Isabel Amorim De Azevedo

Doutor Rui Manuel Almeida Mota Cardoso Doutor Serafim Correia Pinto Guimarães

Doutor Valdemar Miguel Botelho Dos Santos Cardoso Doutor Walter Friedrich Alfred Osswald

Membros do Júri da Prova de Doutoramento, Programa Doutoral em Saúde Pública

Presidente: Doutor José Henrique Dias Pinto de Barros, professor catedrático da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto

VOGAIS: Doutor Don Des Jarlais, psychiatry professor of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai;

Doutora Maria Prins, professor of Public Health, of the University of Amsterdam’s Faculty of Medicine;

Doutor Julien Perelman, professor auxiliar da Universidade Nova de Lisboa;

Doutora Marta Sofia de Sousa Pinto, professora auxiliar convidada da Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educaçao da Universidade do Porto;

Doutora Ana Rita Pires Gaio, professora auxiliar da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto;

Doutora Raquel Lucas Calado Ferreira, assistente convidada da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto

Ao abrigo do Art.º 8º do Decreto-Lei n.º 388/70, fazem parte desta dissertação as seguintes publicações:

A. Artigos em Jornais revisados por pares

Wiessing LG, Houweling H, Spruit IP, Korf DJ, van Duynhoven YT, Fennema JS, Borgdorff MW. HIV among drug users in regional towns near the initial focus of the Dutch epidemic. AIDS 1996 Oct;10(12):1448-9.

Wiessing LG, Houweling H, Meulders WA, Cerdá E, Jansen M, Sprenger MJ. [Prevalence of HIV infection among drug users in Zuid-Limburg]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1995 Sep 23;139(38):1936-40. [Article in Dutch]

Wiessing LG, van Roosmalen MS, Koedijk P, Bieleman B, Houweling H. Silicones, hormones and HIV in transgender street prostitutes. AIDS 1999 Nov 12;13(16):2315-6.

Wiessing L, van de Laar MJ, Donoghoe MC, Guarita B, Klempová D, Griffiths P. HIV among injecting drug users in Europe: increasing trends in the East. Euro Surveill 2008 Dec 11;13(50):pii=19067. Wiessing L, Guarita B, Giraudon I, Brummer-Korvenkontio H, Salminen M, Cowan SA. European Monitoring Of Notifications Of Hepatitis C Virus Infection In The General Population And Among Injecting Drug Users (IDUs) - The Need To Improve Quality And Comparability. Euro Surveill 2008 May 22;13(21):pii=18884.

Wiessing L, Likatavičius G, Klempová D, Hedrich D, Nardone A, Griffiths P. Associations Between Availability And Coverage Of HIV-Prevention Measures And Subsequent Incidence Of Diagnosed HIV Infection Among Injection Drug Users. Am J Public Health. 2009 Jun;99(6):1049-52.

Wiessing L, Likatavicius G, Hedrich D, Guarita B, van de Laar MJ, Vicente J. Trends in HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among injecting drug users in Europe, 2005 to 2010. Euro Surveill 2011 Dec 1;16(48):pii=20031.

Wiessing L, Ferri M, Grady B, Kantzanou M, Sperle I, Cullen KJ; EMCDDA DRID Group, Hatzakis A, Prins M, Vickerman P, Lazarus JV, Hope VD, Matheï C. Hepatitis C Virus Infection Epidemiology Among People Who Inject Drugs In Europe: A Systematic Review Of Data For Scaling Up Treatment And Prevention. Plos One. 2014 Jul 28;9(7):E103345.

Wiessing L, Matheï C, Vickerman P, Prins M, Kretzschmar M, Kantzanou M, Giraudon I, Ferri M, Griffiths P. Tackling hepatitis C among PWID in Europe: what can we learn from HIV? In: Roundtable Discussion: How Lessons Learned From HIV Can Inform The Global Response To Viral Hepatitis. Lazarus JV, Lundgren J, Casabona J, Wiessing L, et al. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14 Suppl 6:S18.

B. Outras publicações

Wiessing LG, Toet J, Houweling H, Koedijk PM, Akker R vd, Sprenger MJW. Prevalentie en risicofactoren van HIV-infectie onder druggebruikers in Rotterdam. Bilthoven: RIVM; 1995.

http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/213220001.pdf. [Research report in Dutch]

Wiessing L, Bravo MJ. DRID Guidance Module: Behavioural Indicators For People Who Inject Drugs. Lisbon: EMCDDA; 2013 Dec.

http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_220259_EN_DRID_module_behavioural_indic ators_final.pdf

Rosinska M, Wiessing L. DRID Guidance Module: Methods of bio-behavioural surveys on HIV and viral hepatitis in people who inject drugs — a short overview. Lisbon: EMCDDA; 2013 Dec.

http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_220260_EN_DRID_module_study_methods_ final.pdf

Bravo MJ, Wiessing L. DRID Guidance Module: Example questionnaire for bio-behavioural surveys in people who inject drugs. Lisbon: EMCDDA; 2013 Dec.

http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_222624_EN_DRID_module_example_questio nnaire_27012014.docx

Wiessing L, Denis B, Guttormsson U, Haas S, Hamouda O, Hariga F, et al. Estimating Coverage of Harm-Reduction Measures for Injection Drug Users in Europe. Durban South-Africa, National Institute on Drug Abuse - National Institutes of Health - U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/?

fuseaction=public.AttachmentDownload&nNodeID=1527

EMCDDA, ECDC. HIV in injecting drug users in the EU/EEA, following a reported increase of cases in Greece and Romania. Lisbon; 2012 Jan.

http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_146511_EN_emcdda-ecdc-2012- riskassessment.pdf

I dedicate this work to all people who are excluded, left standing outside or being thrown out, not helped while in need, not accepted for who they are or facing aggression or discrimination.

I also dedicate this thesis to the peoples of Europe and the European ideal—of tolerance, respect for human rights and democratic participation—which is once again reaching beyond.

Luis Mendão, one of my most influential and admired colleagues, has kindly accepted to receive a copy in their name.

Contents

PREFACE...4

SUMMARY...6

Section 1 INTRODUCTION...18

Section 2 HIV AND VIRAL HEPATITIS STUDIES IN PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS IN THE NETHERLANDS...22

Chapter 1 HIV among drug users in regional towns near the initial focus of the Dutch epidemic...24

Chapter 2 Prevalence of HIV infection among drug users in Zuid-Limburg...28

Chapter 3 Prevalence and risk factors for HIV infection among drug users in Rotterdam...40

Chapter 4 Silicones, hormones and HIV in transgender street prostitutes...52

Section 3 MONITORING HIV AND VIRAL HEPATITIS IN PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS AT EUROPEAN LEVEL...56

Chapter 5 HIV Among Injecting Drug Users In Europe: Increasing Trends In The East...58

Chapter 6 European Monitoring Of Notifications Of Hepatitis C Virus Infection In The General Population And Among Injecting Drug Users (IDUs) - The Need To Improve Quality And Comparability...66

Chapter 7 Methods – EMCDDA toolkit for monitoring infectious diseases...76

Section 4 TRENDS IN DRUG USE AND INTERVENTION COVERAGE AS DETERMINANTS OF HIV AND VIRAL HEPATITIS INFECTION...80

Chapter 8 Estimating Coverage of Harm-Reduction Measures for Injection Drug Users in Europe...82

Chapter 9 Associations Between Availability And Coverage Of HIV-Prevention Measures And Subsequent Incidence Of Diagnosed HIV Infection Among Injection Drug Users...96

Section 5 HIV OUTBREAKS AND EUROPEAN RISK ASSESSMENT...106

Chapter 10 Trends In HIV And Hepatitis C Virus Infections Among Injecting Drug Users In Europe, 2005 To 2010...108

Chapter 11 HIV in injecting drug users in the EU/EEA, following a reported increase of cases in Greece and Romania...118

Section 6 HEPATITIS C TREATMENT SCALE-UP...138

Chapter 12 Hepatitis C Virus Infection Epidemiology Among People Who Inject Drugs In Europe: A Systematic Review Of Data For Scaling Up Treatment And Prevention...140

Chapter 13 Tackling hepatitis C among PWID in Europe: what can we learn from HIV?...180

Section 7 DISCUSSION...186

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS...202

PREFACE

This thesis reflects my work since the early 1990s on the epidemiology of HIV and viral hepatitis among people who inject drugs. I started working in the HIV/AIDS area as a data manager at the Municipal Health Services (GGD) in Amsterdam, soon moving to a junior research post at the

National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in Bilthoven, the Netherlands, in the first few years combined with a research position at the University of Amsterdam, before finally settling in the beautiful city of Lisbon, Portugal, at the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA).

I would like to thank my first colleagues and supervisors at the GGD, Frits van Griensven and Paul Veugelers, for the trust they gave me right from the start. I remember this somewhat depended on providing a quick software solution in SPSS to a small problem they had not been able to solve for two weeks and that Frits handed to me on my first day in office, clearly as a test. I owe to Paul that very first job, for which he tipped me and which would turn out to be defining for my future career. At the RIVM I worked during seven years under the expert and pleasant supervision of Hans Houweling, who took me on Frits’ recommendation, and allowed me soon to grow from a data manager to a junior researcher, analysing and writing up my own data and organising my own studies. In the first three years this position was combined with research on nutritional epidemiology (the Dutch famine birth cohort study) under the equally expert and pleasant supervision of Bertie Lumey at the Academic Medical Center of the University of Amsterdam. I have good memories of the fun and interesting discussions and our joint intellectual quests for understanding and learning epidemiology and statistics in those early days of pc-based multivariate analysis (including jokey attempts at log-adjusting the odds ratio to make it zero-centered and more intuitive, resulting in the not-so-world-famous Wiessing odds ratio (WOR), or writing a little timer routine in the programming language ‘Basic’ to warn us of our looming burnt toast). I would like to extend my thanks to the other great colleagues I was lucky to have had at RIVM, all of whom have moved on to become highly respected experts in their fields. Their collegial support and friendship spanned from nervous preparations for conference presentations to our rather variable success in RIVM sailing regatta’s, or our joint organisation of the quite madly fun regular social events of the CIE team (Centre for Infectious Diseases Epidemiology) including some nearly-botched attempts at ballroom dancing and/or ‘wadlopen’ (google it). I am unable to list all those wonderful colleagues here, but would especially like to thank Hester de Melker, my office mate, for her kindness and patience, and Mirjam Kretzschmar, for our incredibly interesting explorations and stimulating collaborations in

mathematical modelling, under her highly expert leadership, which would extend far into my European years. Here also I would like to thank my true mentor Hans Jager, who introduced me and supported my contributions to his pioneering European work in HIV/AIDS, based on the central idea of bringing the best experts together from a wide range of disciplines and building a range of results around their own interests and strengths. This gave me a blueprint on how to start organising my own European projects several years later at EMCDDA, some of these again building on his expert advice and senior leadership.

After I had carried out some ten epidemiological studies in different risk groups (though mostly in people who inject drugs) of HIV/AIDS in the Netherlands, my good friend and top EU Commission expert in nuclear physics Alejandro Zurita pointed me to a job advertisement in Lisbon, for an epidemiologist in the drugs field at an unknown new EU Centre. Applying at first out of curiosity — the potential free weekend trip to Lisbon for the interview was not an handicap — I quickly became more seriously interested and convinced that my future bosses, Richard Hartnoll and Georges Estievenart, were genuinely interested in setting up high quality European epidemiological monitoring and research in the field of drug use. I want to thank Richard for his trust in my

capabilities and his expert advice whenever I felt stuck or in need of discussing a new idea to bring the work of the Centre forward in those early days of its existence. I want also to thank Georges for his confidence in a young Dutch epidemiologist with little international experience. When I had to interrupt my PhD work in the Netherlands to move to Lisbon, Georges promised me that the Centre would ‘accommodate’ me to pursue finishing it in my new post. Despite the huge work load in those early years which eluded any practical implementation of this promise, I do thank him for his kind intentions and giving me the hope that it would still one day be possible to close that chapter and aim at new targets. I want to thank the EMCDDA0, our new Director Alexis Goosdeel, and the Reitox National Focal Points for making this work possible and for their colleagial support through all those years. Finally, I want to warmly thank my colleague and friend Prof. Henrique Barros, of the Institute of Public Health at the University of Porto, for inviting me annually to give a lecture in his Master’s course on infectious diseases and, during the pleasant evening dinners afterwards, to repeatedly nudge me into believing that I could actually pull together my published work and still finalise my PhD at the University of Porto after all those years.

The work here described – as well as all the other work that could not be included but similarly shaped my career – has fully depended on my collaboration with many, many experts and friends, in Europe and globally, many of whom deserve my utmost respect and gratitude for the time and advice and work they have provided for our joint projects. They are listed as co-authors and

collaborators as well as mentioned in the specific acknowledgements of the following chapters (and in the publications not here included, often under their leadership), and where necessary in more detailed descriptions of the different author contributions to each piece of work.

As required by the University of Porto, I declare that, on each of the following chapters of this thesis, I have played a central and most often leading role in terms of conceiving, planning, organising, data gathering, analysing and writing up of the work described.

Lucas Wiessing

SUMMARY

Abstract

Bio-behavioural survey methods to monitor HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in people who inject drugs were developed and applied, both at national level (the Netherlands) and and at European level (the European Union). The European level monitoring included innovative elements such as measuring intervention coverage (opioid substitution treatment, needle and syringe programmes), HIV risk assessments and using hepatitis C data as an ‘early warning’ HIV risk indicator. These methods supported an early national response during two large HIV outbreaks in Greece and Romania, two countries that had low intervention coverage. Other findings include: Imprisonment is associated with a high risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs, potentially also following release, suggesting that finding alternatives to incarcerating people who inject drugs would be beneficial. Despite a long-term strong decline in HIV cases among people who inject drugs across Europe, both HIV and HCV transmission continue in this group. This includes large outbreaks of HIV and high levels of HCV. In some countries prevention coverage remains insufficient or is unknown. Data from some countries suggest a strong association between HIV levels and coverage of opioid substitution treatment and needle and syringe programmes. Data to guide the scale-up of hepatitis C treatment in people who inject drugs across the European Union are of variable quality and in some topic areas scarce. However, where available, they suggest that diagnosis and treatment rates of people who inject drugs remain poor.

Global summary

This thesis presents my work on the epidemiology of HIV and HCV among people who inject drugs (PWID), one of the key transmission groups for both infections. It describes a number of studies carried out in the context of the development of a monitoring system to guide policy on this public health problem. This work started at national level in the Netherlands then continued at European level, by bringing together national level systems and working intensively during many years with experts from over 30 countries.

The work described in this thesis has resulted in a number of main results, which are both

methodological and epidemiological (descriptive, observational) in nature. While each section and chapter has its own particular findings and conclusions, I attempt to draw these together in the Discussion along three general lines of inquiry or research questions.

The overarching research questions in this thesis, all relating to HIV and HCV among PWID, are: 1. How can monitoring be improved?

2. What is the spread of HIV and HCV among PWID? 3. What are the implications for prevention?

Regarding the first question, I demonstrate how a system of repeated bio-behavioural surveys among PWID can be set up at national level that elucidates the epidemiology of HIV and HCV in this

marginalised group of people as well as related sub-groups (e.g. non-injecting drug users and transgender street sex workers). I also show how similar national monitoring datasets can be combined into European level monitoring. The latter demonstrates striking differences in

epidemiology and intervention coverage suggesting a strong association between the two. I propose to extend epidemiological monitoring to include coverage of interventions (opioid substitution treatment - OST, needle and syringe programmes - NSP) using population level indicators, as well as the use of HCV as a population level indicator of HIV risk e.g. to understand the risk of HIV outbreaks in PWID. Finally, this work shows the importance of proxy indicators of incidence (prevalence among young and new PWID) to understand trends in infection rates. These form a key element of recent European guidance for bio-behavioural monitoring among PWID (Chapter 7).

The different individual studies in this thesis suggest that bio-behavioural monitoring should take account of subnational variability in epidemiology, of positive but potentially also adverse effects of service provision, prison-related spread including post release, and remain flexible and open to study new situations and subgroups in the PWID target population. European monitoring should consider routinely including Eastern Europe, improve data quality and gaps including of transmission category in case reporting data, combine different methods to provide a more complete picture, use recently developed monitoring guidance for PWID. Intervention provision should be monitored on a routine basis using both population level and individual level (survey) indicators of NSP and OST coverage. Global level monitoring should combine epidemiology and intervention indicators on a routine basis. Monitoring of PWID should combine and interpret HIV and HCV indicators in conjunction to assess risks of HIV outbreaks in a timely manner and consider filling existing gaps in evidence with regard to HCV diagnosis and treatment uptake.

Regarding the second question I show how the spread of HIV among PWID in the Netherlands was distributed outside Amsterdam, extending in one study in Rotterdam to HCV among PWID and HIV among a small group of transgender street sex workers injecting hormones and silicones. At

European level I demonstrate large differences between countries and parts of Europe both in levels and trends and using different datasets (case reports, prevalence data). Data until 2011 suggest that overall HIV transmission has been falling across Europe, although large outbreaks have still occurred in 2011 in Greece and Romania, and smaller ones in other countries since. HCV prevalence has not shown important declines and appears to continue spreading in young and new injectors in many countries. Importantly, trends in HCV among PWID are likely to reflect injecting risk behaviour and may predict increases in HIV transmission. The work in the Netherlands has contributed to a general understanding of the epidemiology of HIV at national level. The work at European level has provided a first consolidated overview of the spread of HIV and HCV among PWID in Europe and is likely to have supported national and European policy making since the mid-1990s. However, large gaps in data quality, comparability and availability remain.

The different individual studies suggest that important heterogeneity in HIV prevalence among PWID may exist within countries, that attendees of prevention services may in some cases have higher levels of HIV infection, that HIV infection may be associated with imprisonment, including after release, that transgender street sex workers may have high levels of HIV and frequent contacts with men who have sex with men (MSM) but not with PWID and that trends in Eastern Europe showed no

signs of declining, unlike the trend in the EU/EFTA area. PWID are likely to be an important risk group for HCV infection in Europe, with rates of 40-100% PWID among notified cases in different countries. It was further found there are important differences in the spread of HIV among PWID between selected countries globally and the EU and they appear to be strongly associated with intervention (NSP, OST) coverage. Overall the rate of newly reported HIV cases of PWID has declined in the EU, however large outbreaks have occurred in Greece and Romania and smaller ones in other countries. HCV prevalence increased prior to the HIV outbreaks suggesting it may reflect HIV risk of a

population and provide an early warning indicator for potential outbreaks. The outbreaks occurred in a context of low or declining harm reduction coverage, suggesting a potential causal link. In Romania, the increase may have been further linked to a rise in the injection of synthetic cathinones, whereas in Greece immigrant populations and the economic recession may have played an additional role. HCV incidence data are scarce and often not recent, but where available they suggest high levels of new infections among PWID. HIV coinfection among HCV infected PWID is highly variable and reflects the epidemiology of HIV among PWID in the EU.

On the third question, my work suggests that in the Netherlands prevention may have been

implemented in time to stop the spread of HIV in some smaller cities outside Amsterdam, but not in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Southern Limburg. In Rotterdam, prevention coverage appeared to be high. However, NSP provision may also have been insufficient in some areas (e.g. Southern Limburg) and in that region adverse effects could even not be ruled out (possibly by concentrating HIV-infected PWID in a situation of insufficient provision of sterile syringes). While the precise mechanism of these findings could not be clarified in this study, they imply that it is of high importance to ensure that NSP cater fully to the needs of their clients, providing high coverage and high quality service, to avoid potential adverse effects. Specific high-risk groups such as transgender street sex workers should be offered tailored services for their needs. The Rotterdam study (Chapter 3) highlights the importance of imprisonment as a risk factor with possible implications for law enforcement aspects of drug policy. At European level the work suggests associations between coverage of interventions (OST, NSP) and HIV spread among PWID. Regarding HCV it appears that many countries may have low availability and quality of data on the epidemiology and interventions (diagnosis, treatment uptake) to guide a massive treatment scale-up among PWID, as is indicated by the availability of new highly effective treatments. In Europe, where data are available, the coverage of OST and NSP appears to vary widely between countries, with some countries clearly providing less than optimal levels (see Discussion, Global Figures 1,2). The methods used to estimate coverage are subject to important limitations, such as their dependence on the quality and availability of population size estimates of the target population. Still however they are likely to provide useful information to guide prevention policy by highlighting countries with very low coverage. Countries with large outbreaks of HIV had documented low levels of intervention coverage, providing some support to the relevance of coverage estimates. EMCDDA methods for coverage monitoring consist of combining administrative data (numbers of syringes provided, numbers of opioid users entering OST) with population size estimates. These methods have been adopted globally by the WHO(1;2)(1;2)(1;2)(1;2)(1;2)(1;2)(1;2) (1;2)(1;2)(1;2)[1;2].

From the analysis of this material three further questions emerged, they are: 4. What is the risk of new outbreaks of HIV among PWID in Europe? 5. Is the European Union prepared to scale up HCV treatment of PWID?

6. What can we learn from the HIV and HCV epidemics among PWID for intervention best practice?

Regarding question 4, a European risk assessment developed by myself suggested that several more countries may be at risk of future HIV outbreaks given increasing prevalence of HCV, for example in Hungary(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)(3;4)[3;4], as well as low coverage of NSP and OST. Regarding question 5, it appears that only few countries in the EU have invested in monitoring and estimating essential elements of the HCV epidemic and treatment cascade for PWID, including incidence, chronicity, HIV co-infection, genotypes, access to diagnosis and treatment and burden of disease (Chapter 12). It seems likely that overall the EU is not sufficiently prepared to scale up HCV treatment for PWID.

Regarding question 6, it is clear that the HIV/AIDS epidemic and its public health response provide an important model for responding to HCV. This includes the concept of a multi-sectorial approach, with involvement of all stake holders including civil society organisations representing the interests of PWID and people living with HIV. It also includes the “treatment as prevention” concept i.e.

treatment of active injectors to reduce onward transmission, using modelling studies to estimate the effect of policies and to enhance epidemiological information (e.g. by estimating the number

undiagnosed or investigating different intervention scenarios), improving behavioural information in epidemiological studies (both cohort and cross-sectional), monitoring intervention coverage and performing targeted studies on barriers for implementation, looking at interrelationships between HIV and HCV (e.g. co-infection and HCV as an injecting risk indicator). Three points can be mentioned as conditions for effective HCV policies: 1) a strong focus on universal treatment access, including for active PWID; 2) a strong information base by evaluating epidemiological and behavioural monitoring and assessing if they are fit for purpose; 3) embedding HCV interventions in wider multifaceted and integrated care systems that are tailored to specific risk groups, e.g. by combining drug treatment and antiviral treatment for PWID.

The work here described has important limitations. These include that data collected from PWID is not from random samples that can be assumed representative for the target population but necessarily are based on convenience samples and data from routine services. This problem is compounded at European level as the data monitored by the EMCDDA are even more often from routine services than the studies described in Section 1, which are partly based on street recruitment of PWID. Since the latter were performed, more sophisticated recruitment methods have become available such as respondent driven sampling, which could not be used in the work here described. However, it is unlikely that this has strongly influenced the results and there have been mixed experiences with these newer methods. When describing the European situation also often there are missing data or old data for some or multiple countries, thereby clearly limiting the quality of the assessments which can only be based on those countries that provided data. This problem is even stronger for some indicators that are more difficult to obtain even if more useful such as prevalence in young PWID and in new PWID.

In conclusion, this thesis shows that repeated bio-behavioral surveys are important to understand the spread of bloodborne infections, risk behaviours and prevention coverage among PWID. It also proposes and discusses methods to bring together data from a large number of countries in a large region and thus establish monitoring at the international level. Some of these methods have been

subsequently adopted at the global level by the UN, suggesting that they may have merit. However, despite improved monitoring in Europe of HIV and among PWID, data are often still lacking or of low quality, transmission continues to occur in some cases evidenced by large outbreaks of HIV and prevention coverage remains low in several countries. This suggests that there is a continued need to better understand how to support countries in responding to the joint epidemics of drug use and infectious diseases.

Further detail by section and chapter

Below follows a more detailed summary interpretation of each section and chapter, with the findings of each study presented in boxes to the right (see also boxes and

references at the end of each chapter).

In Section 2 it is shown that bio-behavioural surveys among PWID are feasible and can provide meaningful and valid estimates of HIV prevalence as well as elucidate risk factors for infection. The work described in the Netherlands provided an important complement to the cohort studies already being carried out in Amsterdam, by providing cross-sectional snapshots of HIV spread and risk factors in other cities across the country. In Section 2 four out of the ten studies that I planned, coordinated and carried out in the Netherlands are described (Chapters 1-4, all study reports are available online (5)).

The first study (Chapter 1) showed a dramatic difference in HIV prevalence among PWID outside Amsterdam (0-3%) as compared to Amsterdam (30%), despite higher levels of injecting and sexual risk behaviour outside Amsterdam. This suggests that HIV was first introduced and rapidly spread in Amsterdam, and although prevention measures were implemented later outside Amsterdam this was still in time to prevent similar rapid spread in those smaller towns. The higher levels of risk behaviour outside Amsterdam suggest that reductions in risk behaviour may have been larger in Amsterdam, possibly due to the higher visibility of the AIDS epidemic during the 1980s.

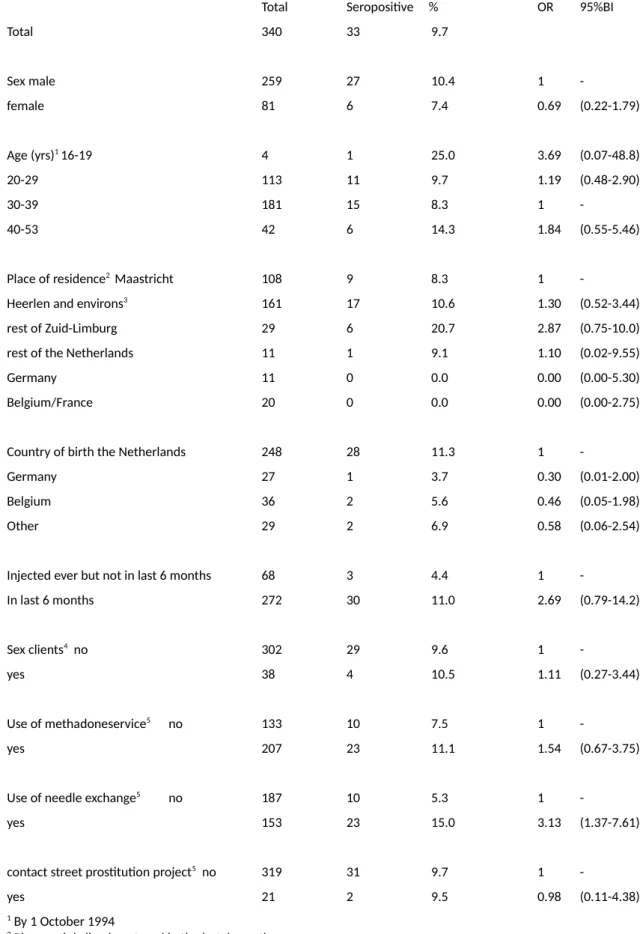

The second study (Chapter 2) found relatively high prevalence (10%) in the Southern region of the Netherlands and an unexpected positive association with NSP attendance, which in multivariate analysis could not be explained by selection on higher risk. This means that, unless the analysis was unable to fully remove such bias (‘residual confounding’), it cannot be ruled out that HIV actually spread more efficiently among those attending the NSP. This could for example happen if there was still insufficient coverage of syringes among the NSP attenders and if they had closer networks (e.g. due to attending the service), however data to look into this was not available in the study. These results are

Findings Section 2

• Chapter 1: Low prevalence (0-3%) in three regional towns outside Amsterdam, despite a higher level of injecting and sexual risk behaviour • Chapter 2: First finding of high HIV prevalence (10%) among PWID outside Amsterdam. No infections among non-PWID. Higher HIV prevalence among current PWID attending a NSP, despite adjustment for multiple potential confounders, including borrowing used syringes in the last 6 months.

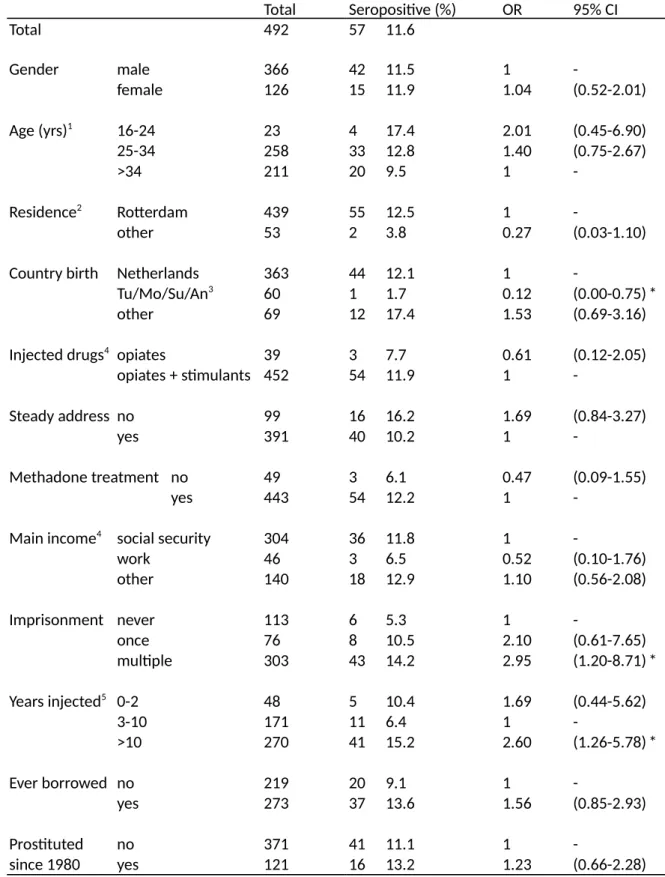

• Chapter 3: High prevalence (12%) among PWID in Rotterdam, the second largest city in the Netherlands. A strong trend association between HIV infection and a history of

imprisonment. First estimate of PWID population size in a city in the

Netherlands using indirect estimation methods.

• Chapter 4: We found an HIV prevalence of 8% (three infected) among 38 transgender street sex workers in Rotterdam, as well as high self-reported levels of recent primary syphilis infection. Drug use and drug related risk behaviours were low. Condom use was high with clients but low with steady partners.

very atypical and have to be interpreted with extreme caution; however, they indicate that studies evaluating service impact must consider the possibility of potential adverse effects.

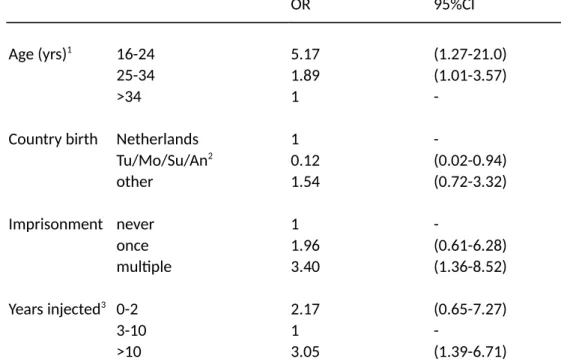

The third study (Chapter 3) was performed in the second largest city of the Netherlands, finding a relatively high HIV prevalence (12%) as well as a strong trend association between HIV infection and a history of imprisonment, adjusting for other variables. These results suggested that (repeated) imprisonment may have been an important risk factor for HIV infection in this population. This could be due to either infections occurring in prison (6), or after release, or alternatively if imprisonment was a confounder for other injection related risks, not captured by the study (however note that the results were adjusted for a number of variables including needle sharing frequency). A later study in Amsterdam suggested that PWID in prison in the Netherlands hardly inject or share needles despite frequently using heroin and cocaine (7). More recent studies have suggested that PWID are exposed to higher risks after release from prison (8). Thus, it seems more likely that, although a history of imprisonment is a direct risk factor for HIV infection (and not a confounder) this risk is not occurring inside prison but immediately after release. If this is the case, then prevention inside prisons will have a limited effect (and could in the case of NSP even be counterproductive (7)) while preventing imprisonment of PWID might have far stronger public health effects. This is further supported by similar results with regard to mortality after prison release (9). Recent data suggest that an

association between HIV and prison history continues to exist in many EU countries (see Discussion, Global Figure 3) (10).

The fourth and final study of Section 2 (Chapter 4) concentrated on a small but potentially important risk group of transgender street sex workers in the city of Rotterdam, finding a high HIV prevalence (8%) but low drug use and drug related risk behaviours. This study shows that it is possible to find meaningful information from hard to reach risk groups for HIV when using risk group sensitive recruitment approaches, even if this was an ad hoc additional objective developed after the start of the main study (described in the previous paragraph, Chapter 3). The results suggest that

transgender street sex workers are not likely to form a ‘bridge’ for HIV infection between PWID and the general population. However, they are themselves at high risk of HIV infection through sex work with men who have sex with men (MSM) and they may transmit infections from this high-risk group to the heterosexual population. Studies as the one described in this chapter may provide key information for developing risk group specific prevention measures e.g. tailored low-threshold services and social support for this group.

In Section 3 this thesis turns from national bio-behavioural studies to the European level. The first study used both case reporting data and bio-behavioural prevalence studies in PWID (similar to those in Section 1) to describe the spread of HIV and HCV in this risk group across the WHO European region. It found large differences in prevalence and trends between the Western and Eastern parts of Europe. While in the EU a continuous decline is visible in the most affected countries (and overall), in Eastern Europe the trends were still up. In the EU/EEA several countries showed declines in new diagnosed cases (Estonia, Portugal) but some also increases (Latvia, Bulgaria, Sweden, UK) between 2001 and 2007. HIV prevalence declined in four countries at national level (Bulgaria, Germany, Spain and Italy) although in two of those increases were recorded at sub-national level (Bulgaria, Italy) and in one, Lithuania, prevalence increased at the national level. In four other countries, although national level data appeared stable and low, at least one sub-national sample showed an increasing trend (Belgium, Czech Republic, Slovenia and United Kingdom). In addition to the prevalence in full

samples of PWID, the prevalence in those under age 25 provided further indication of ongoing transmission, with high levels (over 5%) found in several countries: Spain (national data, 2005), Portugal (national data, 2006), Estonia (two regions, 2005), Latvia (national and in two cities, 2002-03), Lithuania (one city, 2006) and Poland (one city, 2005). Overall these data indicated the potential for increases in transmission among PWID in various countries of the EU, despite a generally

declining trend, in strong contrast to the generally increasing trends in Eastern Europe. A second study (Chapter 6) in Section 3 describes hepatitis C notification data in the EU, its limitations as an indicator of incidence or prevalence and its potential use as an indicator of the relative distribution of infection among the different transmission

groups and routes. Data reported to the EMCDDA from 17 countries suggested that all countries require laboratory

confirmation. Case definitions were provided by all countries, but varied, and did not always seem to be consistent with the EU case definition. Overall, the national surveillance systems seemed to differ considerably in the definition of HCV infection, thus strongly limiting the comparability between countries, even though the data might still provide useful information on trends over time. For a majority of HCV cases reported, the risk factors were unknown or not available for surveillance purposes thus severely limiting their interpretability. It was concluded that there are considerable problems in comparing and interpreting the available notifications data, especially when used as an indicator of true incidence of HCV infection, due to the very large proportion of asymptomatic infections, coupled with under-diagnosis, underreporting and the differences in national notification systems. It was proposed to follow changes in proportions of specific transmission categories over time (e.g. the percentage PWID among cases), rather than absolute counts or population rates, to provide more comparable information on trends in hepatitis C infection among different risk groups.

The third chapter in this section (Chapter 7) briefly describes a toolkit developed at the EMCDDA to support countries in carrying out bio-behavioural studies and report them to the European level (the actual toolkit can be found online) (11-15). Together with an expert panel and a small number of key colleagues I coordinated the development of European consensus guidance for 1)

behavioural indicators 2) an example questionnaire to construct those indicators 3) study and recruitment methods. While the three actual guidance modules are too large and detailed to be included in this thesis, Chapter 7 provides an overview of the main elements of the guidance. In a separate report, not here included, the results of a survey to the expert panel are described in which they scored different options for indicators on quality and feasibility (16). Chapter 7 represents a first European consensus study to agree on

Findings Section 3

• Chapter 5: This study

combined data on newly reported HIV diagnoses in PWID with HIV

prevalence data in PWID. It showed that trends in Eastern Europe are very worrying in both types of data. It also showed that some countries

experience recent transmission, despite general stable prevalence. • Chapter 6: This study provides the first European overview of data and methods on HCV notifications. It finds that methods are very

heterogeneous and data difficult to interpret. It proposes to use a relative measure of the proportion of PWID among cases with known risk information, rather than absolute numbers or population rates. It finds that PWID are a large category of cases in many countries, and often the largest category, although the data should be interpreted with caution. • Chapter 7: This study used a large panel of experts to develop consensus guidelines on 1) behavioural indicators 2) example questionnaire to construct those indicators 3) study and recruitment methods.

a large number of behavioural indicators, questionnaire and question formats as well as recruitment and study methods. The modules are currently being used by a large number of countries to report data to EMCDDA as well as a basis for national bio-behavioural studies among PWID. Innovative elements from this European work are being adopted at global level, for example, the indicator on testing history proposes to exclude those who did not need to be tested from the denominator (e.g. because they already knew being positive) which idea is currently being taken up in a similar format by UNAIDS (17).

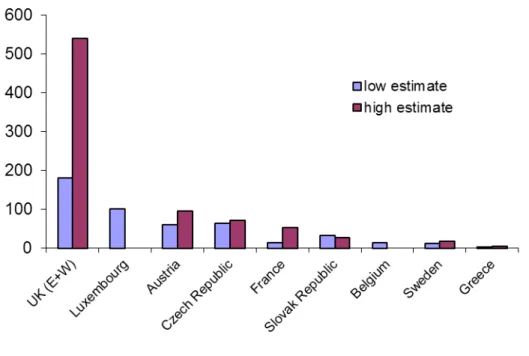

The following section, Section 4, takes again a broader perspective, looking at coverage indicators for interventions as a key indicator of successful implementation of public health measures. At the time this work was developed (2000) this was an innovative approach as harm reduction measures were hardly measured in quantitative terms. Over the years this has become a key indicator of EU monitoring of harm reduction implementation and has been adopted at international level. Chapter 8 describes available data on the prevalence of injecting

drug use and availability or provision of syringes and needles through specialised NSP and combines these two data sources into an indicator of NSP coverage. Estimates need to be interpreted with caution due to in some cases large uncertainty intervals and use of different methods for the population size estimates. However, they suggest that some countries have very low NSP coverage. Similar indicators have been developed for OST. This indicator of NSP coverage has been adopted by the WHO at the global level (1;18). Chapter 9 extends the intervention coverage indicators to include the coverage of OST. It compares the incidence of diagnosed HIV infections and the coverage of opioid substitution treatment and needle-and-syringe programs between the European Union and 5 middle- and high-income countries. Despite the small sample size it finds a strong trend association between diagnosed incidence and intervention coverage. Countries /regions with greater provision of both prevention measures in 2000 to 2004 had lower incidence of diagnosed HIV infection in 2005 and 2006, suggesting that these prevention measures may have had an effect on diagnosed

incidence. Even without assuming this effect, the paper documents important regional differences in coverage of two evidence-based

measures to control HIV among PWID as well as very large differences in the incidence of diagnosed HIV infection among PWID. Both indicators used to measure coverage that were developed by the EMCDDA and applied in this chapter and the previous one (Chapter 8) have subsequently been adopted in other global assessments as well as in WHO guidelines (1;18).

Section 5 of this thesis describes two studies of new HIV outbreaks among PWID in the EU (Greece, Romania). The first study (Chapter 10) describes trends in HIV case reporting and HIV and HCV prevalence data among PWID at European level until 2011 and evaluates the risk of HIV outbreaks, proposing to use HCV trend data as an early indicator of HIV injection risk. This proposal is based on earlier work coordinated by the EMCDDA (including the conception of the idea by EMCDDA of using

Findings Section 4

• Chapter 8: This study used a newly developed monitoring system of PWID population sizes to estimate coverage of NSP, by combining administrative NSP data as a numerator and the population size estimates as the denominator. • Chapter 9: This study compares the incidence of reported HIV cases among PWID and prior intervention coverage (NSP, OST) between the EU (27 countries) and selected countries globally (Australia, Canada, US, Russia and Ukraine). Despite the small sample size it finds a strong trend association between diagnosed incidence and intervention coverage.

HCV as a risk indicator which was contracted out to a modelling expert (19-21)). This idea has been taken up at international level for example by the CDC (22). The study found increasing risk indicators in various countries other than Greece and Romania. Trends in newly diagnosed HIV infection rates were up in Estonia, Iceland, Latvia and Lithuania. Bulgaria and Sweden showed temporary increases which again levelled off. HIV prevalence declined in seven countries (Germany, Spain, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Portugal and Norway). Only one country (Bulgaria) reported increasing HIV prevalence, in the capital city, Sofia, consistent with the increase in newly diagnosed infections. In Italy, although the national trend in HIV prevalence was in decline, an increase was reported in one region (Veneto, data until 2009). The increases in HIV transmission in Greece and Romania reported in 2011 were not observed in HIV prevalence or case reporting data before 2011. Data from samples of young PWID (aged under 25 years) indicated ongoing HIV transmission in six countries (Estonia, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Spain), with prevalence levels above 5% in 2005–2010, and in one country (Bulgaria), where prevalence in young PWID increased in 2005–2010. HCV prevalence data, an indicator of HIV risk, increased in five countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece and Romania); Italy reported increases in two of the 21 regions in parallel with an

overall decline at national level. Data on HCV prevalence in young PWID (under age 25) confirmed increases in Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus and Greece, while in addition an increasing HCV prevalence among new PWID was reported in Greece (nationally and in three regions). The data for Greece are consistent with modelling work suggesting that HIV outbreaks may be preceded by increases in HCV prevalence, given the common injecting transmission route, and thus HCV may be an important early warning indicator for population level HIV risk. This paper also documented important differences in OST and NSP coverage between countries in the EU. The second study (Chapter 11) focuses on the HIV outbreaks in Greece and Romania, developing a tool to assess the risk in countries using a combination of different indicators (a risk assessment). Increases in HIV case reports or prevalence among PWID were reported by six countries as compared to 2008-2010. Seventeen countries reported no changes, four reported fewer cases or lower prevalence, and two did not have information available to assess a change. Countries reporting an increase in the most recent year from which data were available (2011 or 2010) were Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Romania. In Bulgaria, HIV case reports for PWID increased by 8.9% up to October 2011 in comparison with 2010, although 2011 data were only available for Sofia. At national level, an increase in the number of case reports for HIV among PWID was already documented in 2009 in Bulgaria. In Luxembourg, drug surveillance data showed an increased HIV infection prevalence in current PWID from 4.3% in 2009 to 8.1% in 2010 (no data available for 2011). However the proportion of all HIV cases who have injection drug use as a transmission route declined from 6.3% in 2010 to 3.6 % in 2011, as

Findings Section 5

• Chapter 10: This study

documents increasing trends of HIV in Iceland, the three Baltic countries and Bulgaria until 2011. It combines HIV notifications and HIV and HCV prevalence data, showing that HCV prevalence increased in Greece and Romania prior to the HIV outbreaks. This suggests that HCV is a timely indicator of HIV-related injecting risk. Although the EMCDDA had previously proposed this idea and commissioned modelling work to test it in cross-sectional prevalence data (11;12), this is the first time the usefulness of HCV as an early warning indicator is confirmed longitudinally in the context of two actual HIV outbreaks. • Chapter 11: Two countries, Greek and Romania, reported large outbreaks of HIV among PWID. The EMCDDA circulated the Greek outbreak alert at European level. It also developed a risk assessment method, based on indicators of HIV, HCV and prevention, to assess the vulnerability of EU countries to future HIV outbreaks.

of November. In Italy, case reporting data for one region has increased, however the average national prevalence of HIV infection among PWID continues to decline. Lithuania reported more than two times the number of HIV cases in 2009 and 2010 (180 and 153 respectively) as compared to 2008 (95 cases), but also reported increased testing among PWID in 2010. In addition to HIV case or

prevalence increases, reports from some countries where data are available indicate a potential risk for HIV transmission in the PWID population with changes in drug use patterns, from mostly heroin in 2009 to more stimulant use (Austria, Greece, Hungary, Romania); increased HCV rates among PWID (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Romania); low coverage of opioid substitution treatment (Cyprus, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia) or low coverage of needle and syringe programmes (Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia and Sweden). This risk assessment has recently inspired similar risk assessments in the US. The risk assessment method that I personally developed and proposed in Chapter 11 has been separately published as an academic paper (23) and was later re-applied (24).

The final section (Section 6) of this thesis, turns to what is perhaps the largest public health problem associated with drug use at the moment, hepatitis C. A systematic review is presented that collated data from the EU member states on seven different areas related to HCV among PWID. The areas included epidemiological information (incidence, chronicity, co-infection, genotypes and disease burden) as well as intervention assessment (proportion undiagnosed, proportion entering

treatment). In this section also comparisons are drawn between HIV and HCV in terms of both public health responses, in particular what we may learn from the HIV response, which started earlier, to inform the response to HCV. Recent developments in treatment success make this the most timely and relevant topic for PWID, who are likely the largest transmission

group in Europe (see Chapter 6). The work here described aims to contribute to improving hepatitis C treatment delivery to PWID by 1) assessing data quality and availability on key aspects to guide hepatitis C treatment policy in PWID and 2) discussing how hepatitis C treatment strategies for PWID can learn from the long experience with HIV.

The first study (Chapter 12) discusses the European data situation with regard to monitoring a HCV treatment scale-up among PWID. Looking at data availability and quality in 27 EU countries on seven areas it finds that overall data availability is variable and important limitations existed in comparability and representativeness. Nine of 27 countries had data on HCV incidence among PWID, which was often high (2.7-66 /100 person-years, median 13, Interquartile range (IQR) 8.7–28). Most common HCV genotypes were G1 and G3; however, G4 may be increasing, while the proportion of traditionally ‘difficult to treat’ genotypes (G1+G4) showed large variation (median 53, IQR 43–62). Twelve countries reported on HCV chronicity (median 72, IQR 64–81) and 22 on HIV prevalence in HCV-infected PWID (median 3.9%, IQR 0.2–28). Undiagnosed infection, assessed in five countries, was high (median 49%, IQR 38–64), while of those diagnosed, the proportion entering

treatment was low (median 9.5%, IQR 3.5–15). Burden of disease,

Findings Section 6

• Chapter 12: This study reviews the literature on a range of indicators on HCV in PWID in Europe,

complementing routine monitoring by the EMCDDA, to guide HCV treatment policies. It shows that data are of variable quality and in some areas scarce, however, diagnosis and treatment rates of PWID remain poor across the EU.

• Chapter 13: The case for full access to antiviral treatment for PWID is becoming as pertinent as it has been for HIV since the mid-1990s. HCV treatment coverage monitoring is not in place and needs to be

implemented. There is a need for multifaceted and integrated

interventions for PWID, one of which is the treatment of HCV infection.

where assessed, was high and will rise in the next decade. It concluded that key data on HCV epidemiology, care and disease burden among PWID in Europe are sparse but suggest many undiagnosed infections and poor treatment uptake. Stronger efforts are needed to improve data availability to guide an increase in HCV treatment among PWID.

The second study (Chapter 13) discusses what we can learn from HIV to improve our response on hepatitis C in PWID. It argues that given high HCV transmission coupled with low levels of diagnosis and treatment among PWID, as well as rapid developments in treatment effectiveness, the case for full access to antiviral treatment for PWID is becoming as pertinent as it has been for HIV since the mid-1990s. It states that the combination of observational (cohort and bio-behavioural) and modelling studies has proven essential for our understanding of epidemiology, intervention best practice and policy options with regard to both HCV and HIV in PWID (21;25) and that a stronger investment in multidisciplinary studies using country-specific data with the aim to support national policies is greatly needed. It concludes that PWID have many specific needs that extend beyond HCV, including for example shared risk factors for HIV and other infectious diseases, a high risk of death and often serious social, somatic and psychiatric co-morbidity and legal problems. These call for multifaceted and integrated interventions, one of which is the treatment of HCV infection, and that sound public health policies need to integrate both specialist and generalist expertise and data systems with regard to PWID in Europe to be as effective as possible.

Section 1

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

HIV and HCV remain at the forefront of global public health issues. Despite large advances since the HIV epidemic was first described, its global impact remains high and effective prevention is still very much needed, with recent reports suggesting that the international public health response may again be losing ground (26). HCV infection is also increasing in importance due to 1) the longer term natural history which will still lead to peak disease burden in the future and 2) important improvements in treatment recently, which make it more urgent to diagnose and treat larger numbers of patients. In Western Europe (the EU) both infections are highly concentrated in high-risk groups such as PWID, MSM, sex workers and, to a lesser extent, migrants, while transmission in the general population remains low. Thus, prevention and treatment need to focus on high-risk groups to provide an efficient and effective public health response.

In order to guide prevention and treatment decisions, data are needed. These include descriptions of the public heatlh problem (here HIV and HCV among PWID) that are sufficiently detailed to inform decisions on interventions. Then, data are needed again to evaluate whether the interventions have had the desired effect, whether they need to be sustained and if adjustments are needed. The ongoing data collection process on public health problems in the population is often called ‘monitoring’ or ‘surveillance’, where the former is often understood to limit to describing and analysing the problem (e.g. if other actors are responsible for intervening) and the latter may also include active intervention within the surveillance system itself (e.g. outbreak intervention).

In this thesis I will summarise my work done on monitoring HIV and HCV prevalence and incidence in people who inject drugs (PWID), one of the key risk groups for both viruses. My research has focused around developing and implementing monitoring through repeated bio-behavioural prevalence surveys in PWID, both at national level in the Netherlands (Section 2) and at the European level (Sections 3-6). While the different sections and chapters focus on different aspects of HIV and HCV among PWID, an important innovative aspect of my work is that this monitoring extends to the inteventions themselves (by developing population level indicators of coverage of OST and NSP). This approach has not only been adopted by the EMCDDA collaborating countries in Europe but it has also been followed by other studies and guidelines at the global level (1;2;18).

Throughout the thesis and in the Discussion (Section 7), I aim to discuss both methodological

questions (monitoring at national and EU level) as well as epidemiological ones (description of the joint epidemics of HIV, HCV and drug injecting; analysing risk factors and intervention coverage). Each paper in this thesis has its own particular research question and objectives, relating to its own particular outcomes and conclusions. To answer the overarching research questions of this thesis, I summarise and further interpret the specific study findings in a box at the end of each chapter. In the Discussion section I then try to give an integrated analysis of all results.

Research questions

The overarching research questions in this thesis, all relating to HIV and HCV among PWID, are: 1. How can monitoring be improved?

2. What is the spread of HIV and HCV among PWID? 3. What are the implications for prevention?

Section 2

HIV AND VIRAL HEPATITIS STUDIES IN PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS IN

THE NETHERLANDS

Findings

Chapter 1: Low prevalence (0-3%) in three regional towns outside Amsterdam, despite a higher level of injecting and sexual risk behaviour.

Chapter 2: First finding of high HIV prevalence (10%) among PWID outside Amsterdam. No infections among non-PWID. Higher HIV prevalence among current PWID attending a NSP, despite adjustment for multiple potential confounders, including borrowing used syringes in the last 6 months.

Chapter 3: High prevalence (12%) among PWID in Rotterdam, the second largest city in the Netherlands. A strong trend association between HIV infection and a history of

imprisonment. First estimate of PWID population size in a city in the Netherlands using indirect estimation methods.

Chapter 4: We found an HIV prevalence of 8% (three infected) among 38 TSP in Rotterdam, as well as high self-reported levels of recent primary syphilis infection. Drug use and drug related risk behaviours were low. Condom use was high with clients but low with steady partners.

Chapter 1

HIV among drug users in regional towns near the initial focus of the Dutch

epidemic

Wiessing LG, Houweling H, Spruit IP, Korf DJ, van Duynhoven YT, Fennema JS, Borgdorff MW. AIDS 1996;10:1448-9. (See (27) under Global References)

In Europe, most HIV seroprevalence studies on injecting drug users (IDU) have been conducted in large cities and found high levels of infection [1,2]. Few studies have reported on the spread of HIV to IDU in less urbanized regions or to non-IDU [3,4]. HIV infection in non-IDU indicates sexual

transmission, which is potentially a threat for the general population. In Amsterdam, the

seroprevalence among IDU has been about 30% since 1986, whereas a seroprevalence of 5% was found in non-IDU from Surinam or the Antilles [5-7]. In this study we describe the spread of HIV and the levels of risk behaviour among IDU and non-IDU in regional towns near Amsterdam.

Anonymous HIV seroprevalence surveys were conducted in Arnhem, Deventer and Alkmaar, regional towns located 40–100 km from Amsterdam, in 1991–1992. Frequent users of ‘hard drugs’ (heroin, cocaine, methadone or amphetamines) were recruited in methadone care centres and ‘on the streets’. Each participant provided a blood or saliva sample and was tested for anti-HIV antibodies. Blood samples in Arnhem were also tested for anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) core and surface antigens (aHBc/HBsAg) and anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV). In Arnhem, the survey seroprevalence was compared with data from an ongoing laboratory-based HIV surveillance. This surveillance comprises the results of all routine HIV testing in the Arnhem region (about 850 000 inhabitants) since 1990, with

information on transmission category [8]. In all surveys, self-reported risk behaviour was collected in face-to-face interviews. Drug users were classified as IDU if they reported ever having injected drugs. Results were compared with survey data from Amsterdam [1].

HIV seroprevalence was 0-3% among the 282 participating IDU and 0% among the 265 non-IDU outside Amsterdam. The Arnhem laboratory-based seroprevalence was 4.6% among 263 IDU, and showed no increase up to 1994. In the Arnhem survey data, we found a positive association between self-reported injecting and sexual risk behaviour and a history of HIV testing [9]. This suggests an upward bias in the laboratory-based seroprevalence. Seroprevalences of anti-HBV and anti-HCV were high among the IDU, confirming past or current high levels of injecting risk behaviour

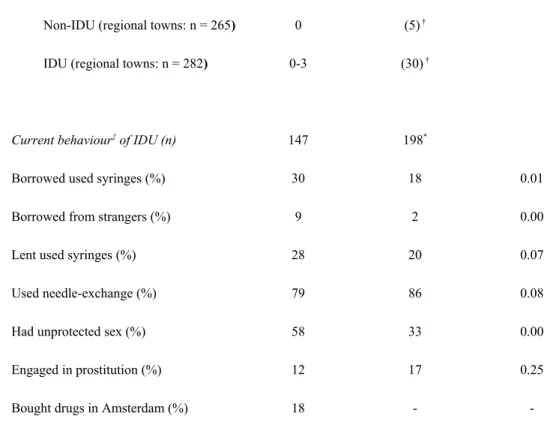

(anti-HBc/HBsAg: 43% among IDU and 6% among IDU; anti-HCV: 66% among IDU and 5% among non-IDU). In the interviews, 55% of the IDU reported ever having borrowed used needles or syringes and 52% reported injecting in the last six months. Comparing current risk behaviour with data from Amsterdam showed a higher level of injecting and sexual risk behaviour outside Amsterdam (Table 1). In addition, drug-related trips to Amsterdam were frequent, as 18% of IDU had bought drugs in Amsterdam in the last 6 months.

Table 1. HIV seroprevalence and self-reported behaviour of non-injecting drug users (non-IDU) and IDU in three regional

towns near Amsterdam (Arnhem, Alkmaar, Deventer, 1991–1992) compared with Amsterdam (1993)*.

---Regional

towns Amsterdam P (χ2)

---HIV seroprevalence (%)

Non-IDU (regional towns: n = 265) 0 (5) †

IDU (regional towns: n = 282) 0-3 (30) †

Current behaviour‡ of IDU (n) 147 198*

Borrowed used syringes (%) 30 18 0.01

Borrowed from strangers (%) 9 2 0.00

Lent used syringes (%) 28 20 0.07

Used needle-exchange (%) 79 86 0.08

Had unprotected sex (%) 58 33 0.00

Engaged in prostitution (%) 12 17 0.25

Bought drugs in Amsterdam (%) 18 -

-

---* For a description of the Amsterdam survey see Papaevangelou and Richardson [1]. † Seroprevalence of IDU in Amsterdam

is from [1,5,6]; seroprevalence among non-IDU (only from Surinam or the Antilles) from Fennema et al. [7]. ‡ Reported

over last six months, only from IDU who injected in last six months (Amsterdam: IDU who injected in last two months).

The Dutch prevention approach concentrated on ‘harm reduction’, starting needle and syringe exchange programmes in Amsterdam as early as 1984 [10], and in Arnhem, Alkmaar and Deventer around 1989. This was too late to prevent a high seroprevalence in Amsterdam but may have been in time for the peripheral towns. It has been found that the timeliness of AIDS prevention, relative to the introduction of HIV, is probably a strong determinant of the level at which HIV seroprevalence stabilizes in a drug user population [11]. The level of injecting and sexual risk behaviour has dropped markedly in Amsterdam since 1986, and it has been concluded that prevention was effective there [5,6,12]. It is likely that a reduction in risk behaviour also occurred outside Amsterdam, as prevention measures were similar. The higher levels of risk behaviour outside Amsterdam, instead of being

inconsistent with successful prevention, may therefore indicate a smaller reduction in risk behaviour, being in line with the later onset of prevention or the lack of visible AIDS cases in these drug user populations. However, longitudinal risk behaviour data to examine this hypothesis are not available outside Amsterdam before 1991.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the spread of HIV from drug users in Amsterdam to these peripheral towns has been very limited. Therefore, the risk of further spread to the general

population seems minimal outside Amsterdam. It seems likely that prevention efforts have helped to avert a large HIV epidemic in these towns. However, with the relatively high levels of risk behaviour, limited spread of HIV still remains possible. It is therefore important to closely monitor HIV

prevalence among IDU. At present we are conducting HIV surveillance using repeated serosurveys among IDU in six towns. Based on these data we are developing stochastic models to explore the risk of a future rise in HIV prevalence among drug users in the Netherlands.

References

1. Papaevangelou G, Richardson SC. HIV prevalence and risk factors among injecting drug users in EC and COST countries. In: AIDS research at EC level. Edited by Baert AE, Koch MA, Montagnier L, Razquin MC, Tyrrell D. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 1995:73-82.

2. Richardson C, Ancelle-Park R, Papaevangelou G. Factors associated with HIV seropositivity in European injecting drug users. AIDS 1993, 7:1485-91.

3. Follett EAC, McIntyre A, O'Donnell B, Clements GB, Desselberger U. HTLV-III antibody in drug abusers in the West of Scotland: The Edinburgh connection. Lancet 1986, i:446-7.

4. Lardelli P, de la Fuente L, Alonso JM, Lopez R, Bravo MJ, Delgado-Rodriguez M. Geographical variations in the prevalence of HIV infection among drug users receiving ambulatory treatment in Spain. Int J Epidemiol 1993, 22:306-14.

5. van den Hoek JAR, van Haastrecht HJA, Coutinho RA. Risk reduction among intravenous drug users in Amsterdam under the influence of AIDS. Am J Public Health 1989, 79:1355-7.

6. van Ameijden EJC, van den Hoek JAR, Mientjes GHC, Coutinho RA. A longitudinal study on the incidence and transmission patterns of HIV, HBV and HCV infection among drug users in Amsterdam. Eur J Epidemiol 1993, 9:255-62.

7. Fennema JSA, van den Hoek JAR, Huisman JG, Coutinho RA. HIV-prevalentie onder Surinaamse en Antilliaanse druggebruikers in Amsterdam. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1993, 137:2209-13.

8. van Duynhoven YT, Houweling H, Wiessing LG, Esveld MI, Nieste HL, Katchaki JN. Laboratory-based HIV surveillance with information on exposure: importance of discriminating person-Laboratory-based from test-based results. Int J STD AIDS 1996, 7:117-22.

9. Wiessing LG, Houweling H, van de Akker R, Katchaki JN, Servaas JHJ, van Rossum JMA. Voluntary testing intravenous drug users are selected with respect to risk. IXth International Conference on AIDS, Berlin, June 7-11, 1993 [abstract PO-C15-2921].

10. Buning EC, Coutinho RA, van Brussel GHA, et al. Preventing AIDS in drug addicts in Amsterdam. Lancet 1986, i:1435.

11. Des Jarlais D, Friedman SR, Ward TP. Harm reduction: a public health response to the AIDS epidemic among injecting drug users. Annu Rev Publ Health 1993, 14:413 50.

12. van Ameijden EJC, Watters JK, van den Hoek JAR, Coutinho RA. Interventions among injecting drug users: do they work? AIDS 1995, 9(suppl A):S75-S84.

FINDINGS OF THIS STUDY What is known?

High prevalence (30%) of HIV among PWID in Amsterdam What is new?

Low prevalence (0-3%) in three regional towns outside Amsterdam, despite a higher level of injecting and sexual risk behaviour.

Interpretation

The HIV epidemic has not reached high levels in these smaller regional towns. This can be due to better and more timely (including in relative terms, due to later introduction of HIV) prevention or other factors such as network characteristics of the PWID population (e.g. less tight connections between groups). Higher risk behaviours than in Amsterdam suggest that risk behaviours in Amsterdam may have declined in response to the high spread of HIV.

HOW DOES THIS STUDY ANSWER THE QUESTIONS OF THIS THESIS? How can monitoring be improved?

This study piloted behavioural surveys among PWID in the Netherlands in regional towns. The epidemiology of HIV can strongly differ between these towns and a larger capital city. Monitoring should take account of potentially important sub-national variability.

What is the spread of HIV and HCV among PWID?

Important heterogeneity was found between surveys in Amsterdam and in three regional towns in the Netherlands in 1991-1993, both in HIV prevalence (30% vs. 0-3%, respectively) and in risk behaviours (higher outside Amsterdam).

What are the implications for prevention?

NSPs were started in 1984 in Amsterdam and around 1989 in the regional towns studied here. It seems likely that prevention efforts have helped to avert a large HIV epidemic in these towns.