ConstruCtion and Validation of a Questionnaire on language learning MotiVation

Larisa Nikitina* and Zuraidah Mohd Don Faculty of Language and Linguistics University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Loh Sau Cheong

Faculty of Education, University of Malaya Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract. This article describes the steps and phases involved in constructing a ques-tionnaire on the motivation to learn a second or foreign language (or L2 motivation). It evaluates psychometric properties of the instrument by performing exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Participants in this study were 194 students. The results of the exploratory factor analysis indicated that four dimensions formed the construct of L2 motivation, namely Instrumental orientation, Integrative orientation, Commit-ment and Effort. The findings from a subsequent confirmatory factor analysis vali-dated the four-dimensional structure. The conclusions reached by this study as well as the steps and phases involved in the development of research instrument on L2 motiva-tion could be informative for educators interested in issues related to language learning motivation and useful for future scholarly investigations of L2 motivation.

Keywords:language learning (L2)motivation, socio-educational model of L2 moti-vation, questionnaire design, questionnaire validation.

Introduction

Motivation is one of the most researched constructs in studies on psychology and education. Since the pioneering studies by Robert Gardner and Wallace Lambert (1959, 1972) motivation to learn a second or foreign language (or L2 motivation) has become a prominent topic in educational research. A deeper understanding of the language learners’ motivation has a substantial peda-gogical value. This is because a good grasp of the nature of L2 motivation and

motivational ebbs and flows could aid language educators in devising better and more effective pedagogical strategies.

Due to its complex nature, L2 motivation has been defined and opera-tionalized in various ways and instruments employed by researchers aimed to investigate different facets of this construct. However, as Dörnyei (2007: 102) observed, “questionnaires that yield scores with sufficient (and well-docu-mented) reliability and validity are not that easy to come by in our field”. The present article aims to address the problem concerning a lack of empirically-based evidence. A specific research question that guided this study was: Will the newly-developed questionnaire on L2 motivation have adequate psycho-metric properties as far as reliability and validity are concerned?

This article describes the process of designing and validating a question-naire on L2 motivation and gives a detailed description of the phases and steps involved in the questionnaire construction. By doing so, it hopes to address the need of language educators for some guidelines concerning the develop-ment of research instrudevelop-ments to assess various psychological constructs that are important in the course of learning and teaching an additional language. Such expertise could be a valuable addition to the professional knowledge of language teachers.

The Concept of Motivation in Psychology

Motivation remains “one of the most elusive concepts in the whole domain of the social sciences” (Dörnyei, 2001: 2). Researchers recognize that the most important component of this construct is action (Leontiev, 1971). As Ryan and Deci (2000: 54) asserted, “to be motivated means to be moved to do something”. An important aspects of a motivated behaviour is the pursuit of a goal, which is known as a motivational ‘orientation’ (Gardner & Lambert, 1972; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

As Ryan and Deci (2000: 54) put it, “orientation of motivation concerns the underlying attitudes and goals that give rise to action – that is, it concerns the why of actions”. There are two widely-accepted motivational orientations: ‘intrinsic motivation’ and ‘extrinsic motivation’. Intrinsic motivation refers to “doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable”, while extrinsic motivation takes precedence when people are “doing something be-cause it leads to a separable outcome” (Ryan & Deci, 2000: 55).

Socio-educational Model of L2 Motivation

the effort exerted to achieve this goal. In research on foreign language educa-tion, the goals to learn a new language are known as ‘integrative orientation’ and ‘instrumental orientation’ (Gardner & Lambert, 1959). It should be noted that though Gardner and Lambert (1959, 1972) differentiated integrative and instrumental orientations in their early studies, this was done only for the purpose of measurement. The two motivational orientations should not be considered as a dichotomy (Gardner, 1985).

Since the publication of Gardner and Lambert’s (1959, 1972) studies, in-tegrative orientation has been one of the most disputed and widely-researched concepts in studies on L2 motivation. Over the decades, definitions of inte-grative orientation have expanded to include attitudinal dispositions on the part of language learners toward the target language country, its culture, language and native speakers of the target language. Nowadays, as Gardner (2010) points out, integrative orientation or integrativeness is recognized as a complex and multilevel concept. More commonly, integrative orientation involves a favourable interest in the target language country, its culture and native speakers (Gardner, 2010).

DEvELOPMENT OF THE qUESTIONNAIRE

ON L2 MOTIvATION

Designing and validating a questionnaire involves qualitative and quantitative phases. In the qualitative phase, the first author conducted a thorough review of the relevant literature, identified constructs and measures to be included in the questionnaire, formulated questionnaire items and sought experts’ opinion as to which of the proposed constructs and pre-selected items should be included in the research instrument. This process was in accordance with literature on questionnaire development (Colton & Covert, 2007; Rasinski, 2008).

The instrument developers paid a special attention to the following two points. First of all, considering criticisms that studies on L2 motivation have not always been grounded in the “real world domain” of the language class-room (Crookes & Schmidt, 1991: 470), special attention was given to ensuring that the resulting instrument has pedagogical and educational value. Secondly, a special care was accorded to the cultural appropriateness of the constructs’ operationalizations and to the wording of the questionnaire items. In order to effectively address these two concerns, the researchers heeded advice given by Onwuegbuzie, Bustamante and Nelson (2010: 63) and consulted the “key informants, which include those on whom the instrument will be adminis-tered” and also foreign language educators.

THE qUALITATIvE PHASE OF INSTRUMENT CONSTRUCTION

OPERATIONALIZATION OF RESEARCH CONSTRUCTS:

THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The socio-educational model of L2 motivation developed by Gardner and Lambert (1959, 1972) and refined by Gardner (1985) guided the conceptual stage of the instrument construction, while relevant studies on motivation in the field of psychology (Ryan & Deci, 2000) informed about pertinent meas-ures that need to be considered for the inclusion in the research instrument. In order to develop a questionnaire that would yield valid and reliable data the instrument developer reviewed and consulted questionnaires employed in previous empirical investigations done in various educational contexts, in-cluding Malaysia (Ainol & Isarji, 2009; Dörnyei & Czisér, 2012; Gardner, 1985, 2004; Kouritzin, Piquemal & Renaud, 2009; Nikitina & Furuoka, 2008; Ryan, 2009).

As an outcome of the literature review process, three relevant motiva-tional constructs or measures were identified. These measures and their op-erational definitions are as follows:

(1) General motivation (6 items): effort and commitment that students are willing to expend to learn the target language (TL) in order to achieve their learning goals;

(2) Instrumental orientation (5 items): language learners’ perceptions of the TL utility and their intention to use the TL for pragmatic purpos-es, such as future studipurpos-es, travel, employment or obtaining financial benefits;

(3) Integrative orientation (5 items): language learners’ intention to learn the TL in order to communicate with the TL speakers and their favourable interest in culture, worldviews and ways of life of the TL speakers. (For the full set of questionnaire items on L2 motivation please refer to the Appendix).

Questionnaire Validity and Cultural Appropriateness

The most acknowledged methodological issues concerning instrument valid-ity are face validvalid-ity, content validvalid-ity and construct validvalid-ity. Face validvalid-ity is described as the degree to which an instrument appears to measure the con-struct of interest, while content validity is “the degree of which an instrument is representative of the topic and process being investigated”; lastly, construct validity is the “degree to which an instrument actually measures” the pro-posed constructs of interest (Colton & Covert, 2007: 66–68; Rasinski, 2008). The former two types of validity are established in the qualitative phase of instrument construction, while the latter is quantitatively gauged by a set of statistical procedures in the quantitative phase.

In the qualitative phase researchers need to consider the cultural appro-priateness of the measures and items to be included in the instrument. As rec-ommended by methodologists (Onwuegbuzie, Bustamante & Nelson, 2010), the instrument developer consulted views of the key informants, namely Ma-laysian foreign language learners at the tertiary level, concerning language learning motivation. Earlier exploratory investigations were important sourc-es of information (Nikitina & Furuoka, 2005; Pogadaev, 2007).

Drawing an Items Pool and Establishing Face

and Content Validity

The next step was to list all the potential questionnaire items for each of the three constructs in this study, namely, general motivation, instrumental ori-entation and integrative oriori-entation. Collections of questions or statements to be included in a questionnaire are known as “item pools” (Colton & Covert, 2007). The initial item pool in this study consisted of 59 items.

The items appeared to make a good fit with the relevant constructs, which established the face validity of the instrument. However, some items were found to be very similar, e.g. the statement “I would like to learn as many languages as possible” selected from a study by Dörnyei (2001) was similar to “I would really like to learn many foreign languages” in Gardner’s (2004) questionnaire. This fact indicated that the item pool construction stage had reached a sufficient saturation level. In order to achieve a concise instrument, only one of the matching items was retained for further consideration. As a result, the number of statements in the item pool went down to 26.

supplied with a short preface that explained purposes of the study and a sec-tion that sought demographic informasec-tion about the participants.

THE qUANTITATIvE PHASE: ESTABLISHING INSTRUMENT’S

RELIABILITy, UNDERLyING STRUCTURE

AND PSyCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES

Data Collection

The questionnaire was distributed to 194 students (26.8% male and 73.2% female). They were learning one of the following languages: French, German, Italian, Portuguese (both Brazilian and European varieties), Russian and Spanish. The participants were in their first semester of the target language study in University of Malaya. All of them had voluntary chosen to learn a foreign language as an elective course. The students were told that their an-swers would be treated as confidential. The return of the completed question-naires was considered as an implied consent to participate in the study.

Reliability analysis and exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

First of all, the reliability or internal consistency of the three scales measuring L2 motivation was assessed based on Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients. Then the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed. The main purpose of EFA was to establish the underlying structure of the students’ L2 motivation, and to assess the validity of the constructs.

Prior to conducting the EFA, suitability of the data set for this statisti-cal procedure was checked (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006). For this purpose, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling ad-equacy and the Bartlett’s chi-square test of sphericity were performed. The suitability of the dataset on L2 motivation for the EFA was confirmed. The KMO coefficient at .851 was above the meritorious .80 range for this index. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2=979.167; p<.01), which

indicated that sufficient correlations existed among the variables.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

struc-tural models. This was done in a number of previous studies in behavioural sciences (Gardner, Tremblay & Masgoret, 1997; Jöreskog as cited in Steiger, 1994; Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006).

There is another argument to consider. Psychometric qualities such as validity and reliability are recognized as the property of samples rather than the property of instruments (Osborne, 2014). This entails the proposition that if scales are strong for one sample they may not be strong for another sam-ple. As van Prooijen and van Der Kloot (2001: 780) noted, “if CFA cannot confirm results of EFA on the same data, one cannot expect that CFA will confirm results of EFA in a different sample or population”. Besides, “scales need to be evaluated in the particular population or data that they reside in” (Osborne, 2014: 112). To ensure a ‘full circle’ of investigation, the current study performed the CFA on the same dataset as the EFA.

This study adopted the CFA guidelines proposed by Hair et al. (2006). First of all, construct reliability (CR) was established in order to assess internal consist-ency of the variables. This step is needed because Cronbach’s alpha, which is a widely-employed estimate for construct reliability, can be underestimated (Hair et al., 2006: 777). The next step was to assess construct validity (Cv) for each factor, including convergent validity (or the extent to which the items forming one construct share a high proportion of variance) and discriminant validity (or the extent to which one construct is truly unique and different from others).

FINDINGS OF STATISTICAL TESTS

Results of the Reliability Test

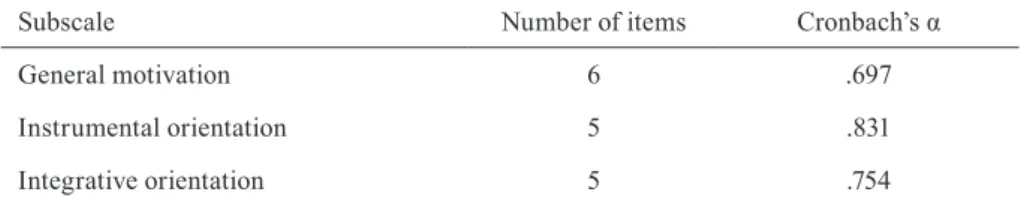

The findings from the reliability test that estimated Cronbach’s alpha (α) are shown in Table 1. According to Hair et al. (2006) and Dörnyei (2007), Cron-bach’s α values between .60 and .70 are acceptable in exploratory research and in studies in the Social Sciences disciplines.

Table 1: Cronbach’s alpha of L2 constructs

Subscale Number of items Cronbach’s α

General motivation 6 .697

Instrumental orientation 5 .831

Integrative orientation 5 .754

Findings from the Exploratory Factor Analysis:

The Underlying Structure of L2 Motivation

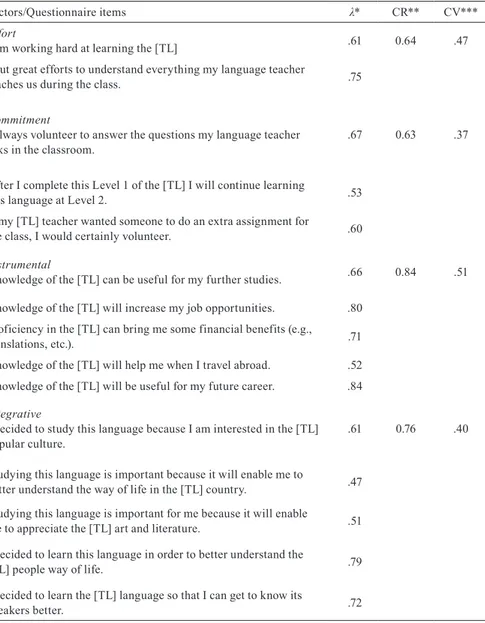

The EFA extracted four factors or dimensions from the data on students’ L2 motivation. One of the 16 items submitted to the analysis had to be removed due to a low communality. The extracted four factors explained approximately 61% of variance, which is satisfactory in the Social Science research (Hair et al., 2006). The underlying structure of L2 motivation was clearly delineated: it consisted of four latent dimensions or factors. All but two of the question-naire items had a single high loading exceeding .40 on only one factor. These two items were retained in the factors where their loadings were above .50.

Next, reliability of the measures (or internal consistency of the factors) was established based on the Cronbach’s α values. The procedure yielded four fac-tors instead of the three originally proposed: the “General motivation” scale was divided into two factors labelled “Commitment” and “Effort”. All four factors had acceptable levels of internal consistency: Factor 1 “Instrumental orienta-tion” had Cronbach’s α=.831; Factor 2 “integrative orientaorienta-tion” had Cronbach’s α=.754. Factors 1 and 2 contained the items that had been originally linked to this motivational construct by the researchers. Further, Factor 3 “Commitment” had Cronbach’s α=.637, and Factor 4 “Effort” had Cronbach’s α=.630.

The separation of the construct of L2 motivation into the four latent fac-tors is sensible. The Facfac-tors 1, 2 and 4 supported the main theoretical un-derpinnings of Gardner’s (1985) model that proposes that L2 motivation in-corporates learning goals (i.e., instrumental and integrative orientations) and requires effort to achieve these goals. Factor 3 substantiates the practitioners’ perspective on L2 motivation that recognizes commitment as an important component of L2 motivation. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the con-struct of L2 motivation in this study consisted of instrumental and integrative orientations (or learning goals) plus effort and commitment to achieve these goals. In the following step, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is performed using AMOS computer software in order to confirm this hypothesis and eval-uate psychometric properties of the instrument in a more rigorous manner.

Findings from the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

because it will enable me to better understand the way of life in the [TL] country” was below the recommended benchmark of .50.

Table 2: L2 motivation factors, their loadings and psychometric estimates

Factors/questionnaire items λ* CR** Cv***

Effort

I am working hard at learning the [TL] .61 0.64 .47

I put great efforts to understand everything my language teacher

teaches us during the class. .75

Commitment

I always volunteer to answer the questions my language teacher

asks in the classroom. .67 0.63 .37

After I complete this Level 1 of the [TL] I will continue learning

this language at Level 2. .53

If my [TL] teacher wanted someone to do an extra assignment for

the class, I would certainly volunteer. .60

Instrumental

Knowledge of the [TL] can be useful for my further studies. .66 0.84 .51

Knowledge of the [TL] will increase my job opportunities. .80 Proficiency in the [TL] can bring me some financial benefits (e.g.,

translations, etc.). .71

Knowledge of the [TL] will help me when I travel abroad. .52 Knowledge of the [TL] will be useful for my future career. .84

Integrative

I decided to study this language because I am interested in the [TL]

popular culture. .61 0.76 .40

Studying this language is important because it will enable me to

better understand the way of life in the [TL] country. .47 Studying this language is important for me because it will enable

me to appreciate the [TL] art and literature. .51 I decided to learn this language in order to better understand the

[TL] people way of life. .79

I decided to learn the [TL] language so that I can get to know its

speakers better. .72

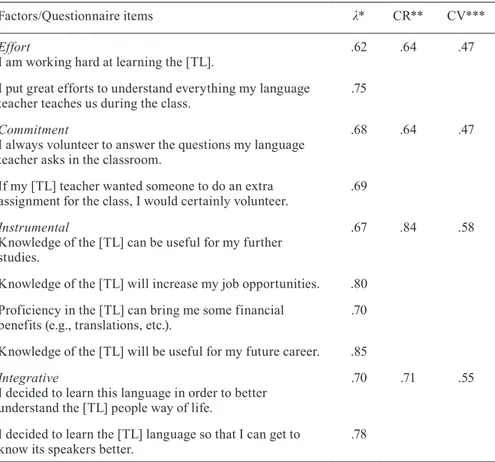

As to the requirements concerning discriminant validity, they were mostly fulfilled except for the integrative orientation–commitment pair of constructs. Based on these findings, items with standardized loadings below .65 were re-moved from the questionnaire in order to improve psychometric properties of the instrument. The CFA performed once again on the reduced dataset and its findings are reported in Table 3. As the results show, psychometric properties of the revised instrument have improved considerably; even though the Cv estimate for the “Effort” (.47) and “Commitment” (.47) factors was lower than the recommended level of .50, it was below the benchmark by only a small margin of .03 points. Furthermore, the discriminant validity of the instrument was good.

Table 3: L2 questionnaire items, their loadings and psychometric estimates

Factors/questionnaire items λ* CR** Cv***

Effort

I am working hard at learning the [TL]. .62 .64 .47 I put great efforts to understand everything my language

teacher teaches us during the class. .75 Commitment

I always volunteer to answer the questions my language teacher asks in the classroom.

.68 .64 .47

If my [TL] teacher wanted someone to do an extra

assignment for the class, I would certainly volunteer. .69 Instrumental

Knowledge of the [TL] can be useful for my further studies.

.67 .84 .58

Knowledge of the [TL] will increase my job opportunities. .80 Proficiency in the [TL] can bring me some financial

benefits (e.g., translations, etc.). .70 Knowledge of the [TL] will be useful for my future career. .85 Integrative

I decided to learn this language in order to better understand the [TL] people way of life.

.70 .71 .55

I decided to learn the [TL] language so that I can get to

know its speakers better. .78

Overall, the findings from the second round of the CFA provided empirical evidence in support of a solid internal structure for each of the four L2 moti-vation factors and good psychometric properties of the reduced questionnaire scales measuring L2 motivation.

Discussion and conclusions

The present study has described the steps and phases involved in constructing a questionnaire to assess L2 motivation and tested psychometric qualities of the resultant instrument. Besides attending to a purely ‘technical’ aspect of de-veloping and validating a questionnaire on psychological constructs involved in the process of language learning, this study highlights the importance of ensuring that the resulting instrument has pedagogical relevance and edu-cational value. This was achieved by incorporating the language educators’ views on L2 motivation as recommended by Crookes and Schmidt (1991).

The findings of the EFA gave empirical support to viewing L2 motiva-tion as comprising two distinct learning goals (i.e., instrumental and integra-tive orientations) and the effort expended to pursue these goals. These results concurred with the conclusions in the earlier studies (Ainol & Isarji, 2009; Nikitina & Furuoka, 2008). Regarding integrative orientation, the relevance of which in the context of foreign language learning has been questioned by some researchers (Nikolov, 1999), the findings revealed its distinct presence in the students’ L2 motivation. Based on the EFA results, integrative orienta-tion incorporated the language learners’ appreciaorienta-tion of a TL country’s art and literature, their desire to gain a deeper knowledge about and a better un-derstanding of the TL speakers and their wish to understand the ways of life in the TL country. Similar findings were reported in the earlier studies (Niki-tina & Furuoka, 2005; Pogadaev, 2007). However, during the CFA procedure, which involves a more rigorous evaluation of an instrument’s psychometric properties, the number of items forming integrative motivation was reduced from five to two. Such a drastic reduction did not occur in the case of the items forming instrumental motivation: four of the original five items were retained. This finding indicates that integrative orientation could be a more elusive component and that capturing the properties of integrative orientation is a more challenging task.

other pedagogically important indicators of L2 motivation must be included in research instruments to measure L2 motivation if these instruments are to have educational and pedagogical relevance.

There are some limitations to this study. Firstly, it has focused on the learners of European languages. Future studies may want to explore whether the four-dimension structure of L2 motivation would be sustained among learners of English language. Secondly, the participants in this study had vol-untarily chosen to learn a foreign language. Further research would be needed among students who learn a foreign language on a compulsory basis. Despite these limitations, the questionnaire has sufficient psychometric properties. Moreover, the instrument presented in this article accommodates not only psychologists’ but also educational practitioners’ viewpoints concerning the nature and determinants of L2 motivation. For this reason the instrument has value for educational research and pedagogical practice.

It is hoped that the description of the questionnaire development process offered in this study, as well as the resultant instrument and the information on its psychometric properties, would be informative for researchers and edu-cators interested in issues related to language learning motivation and that this study could be useful for future scholarly investigations of L2 motiva-tion in various educamotiva-tional contexts. Developers of future instruments on L2 motivation may want to include additional variables that are relevant for their specific educational settings and that have a good potential to inform and enhance foreign language pedagogical practice.

References

Ainol, M. Z. & Isarji, S. (2009). Motivation to learn a foreign language in Malaysia. GEMA: Online Journal of Language Studies, 9(2), 73–87.

Colton, D. & Covert, R. W. (2007). Designing and constructing instruments for social re-search and evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Crookes, G. & Schmidt, R. W. (1991). Motivation: Reopening the research agenda. Language Learning, 41(4), 469–512.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Harlow: Longman.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford: OUP.

Dörnyei, Z. & Czisér, K. (2012). How to design and analyze surveys in second language acquisition research. In A. Mackey & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 74–94). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. Gardner, R. C. & Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second language

acquisi-tion. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 13, 266–272.

Gardner, R. C. & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learn-ing. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C. (2004). Attitude/motivation test battery: International AMTB research project. Ontario, CA: The University of Western Ontario, Canada. Retrieved October 10, 2012 from http://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/englishamtb.pdf

Gardner, R.C. (2010). Motivation and second language acquisition: The socio-educational model. New york: Peter Lang Publishing.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Kormos, J., Kiddle, T. & Csizér, K. (2011). Systems of goals, attitudes, and self-related beliefs in second-language-learning motivation. Applied Linguistics, 32(5), 495–516.

Kouritzin, S. G., Piquemal, N. A. & Renaud, R. D. (2009). An international comparison of socially constructed language learning motivation and beliefs. Foreign Language An-nals, 42(2), 287–317.

Leontiev, A. N. (1971). Potrebnosti, motivy i emotsii [Needs, motives and emotions]. Moscow: Moscow University Press.

Nikitina, L. & Furuoka, F. (2005). Integrative motivation in a foreign language classroom: A study on the nature of motivation of the Russian language learners in Universiti Malay-sia Sabah. Jurnal Kinabalu, 11, 23–34.

Nikitina, L. & Furuoka, F. (2008). Testing suitability of Gardner’s (1985) instrument for the Malaysian educational context. Paper presented at The IMCICON 2008International Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Nikolov, M. (1999). ‘Why do you learn English?’ ‘Because the teacher is short’. A study of Hungarian children’s foreign language learning motivation. LanguageTeaching Re-search, 3(1), 33–56.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Bustamante, R. M. & Nelson, J. A. (2010). Mixed research as a tool for developing quantitative instruments. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 56–78. Osborne, J. W. (2014). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. Create Space

Independ-ent Publishing Platform.

Pogadaev, v. A. (2007). Motivational factors in learning foreign languages: The case of Rus-sian. Masalah Pendidikan, 30(2), 149–159.

Rasinski, K. (2008). Designing reliable and valid questionnaires. In W. Donsbach & M. Traugott (Eds.), The Sage handbook of public opinion research (pp. 361–374). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Ryan, S. (2009). Self and identity in L2 motivation in Japan. The ideal L2 self and Japanese learners of English. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation,language identity and the L2 self (pp. 120–143). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Steiger, J. H. (1994). Factor analysis in the 1980’s and the 1990’s: Some old debates and some new developments. In I. Borg & P. Ph. Mohler (Eds.), Trends and perspectives in empiri-cal social research (pp. 201–223). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Tashakkori, A. & Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quanti-tative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Tkach, C. & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How do people pursue happiness? Relating personal-ity, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Journal of HappinessStudies, 7(2), 183–225.

van Prooijen, J. W. & van Der Kloot, W. A. (2001). Confirmatory analysis of exploratively ob-tained factor structures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(5), 777–792.

APPENDIx

Questionnaire sample

L2 motivation among learners of French

Mark your answer to each of the following questions. Note: 1=Strongly disa-gree (SD); 2=Disadisa-gree (D); 3=Neither disadisa-gree nor adisa-gree (N); 4=Adisa-gree (A); 5=Strongly agree (SA).

No. questions SD D N A SA

1. I decided to study this language because I am

interested in French popular culture. 1 2 3 4 5 2. I am working hard at learning the French

language. 1 2 3 4 5

3. I always volunteer to answer the questions my

language teacher asks in the classroom. 1 2 3 4 5

4. Studying this language is important because it will enable me to better understand the way of life in France.

1 2 3 4 5

5. After I complete this Level 1 of the French language

I will continue learning this language at Level 2. 1 2 3 4 5

6. If my language teacher wanted someone to do an extra assignment for the class, I would certainly volunteer.

1 2 3 4 5

7. Knowledge of the French language will help me

when I travel abroad. 1 2 3 4 5

8. I put great efforts to understand everything my

language teacher teaches us during the class. 1 2 3 4 5

9. Knowledge of the French language can be useful for my further studies, such as at the Master’s or PhD level.

1 2 3 4 5

10. I decided to learn the French language so that I can

get to know its speakers better. 1 2 3 4 5 11. Studying this language is important for me because

it will enable me to appreciate French art and literature.

1 2 3 4 5

12. Knowledge of the French language will increase

13. If the French language was not offered in University of Malaya I would try to go to this language classes somewhere else.

1 2 3 4 5

14. Proficiency in the French language can bring me

some financial benefits (e.g., translations, etc.). 1 2 3 4 5 15. I decided to learn this language in order to better

understand the French people way of life. 1 2 3 4 5 16. Knowledge of the French language will be useful

КОНСТРУИСАЊЕ И ВАЛИДАЦИЈА УПИТНИКА зА ИСПИТИВАЊЕ мОТИВАЦИЈЕ зА УчЕЊЕ СТРАНОГ ЈЕзИКА

Лариса Никитина и Зураида Мод Дон

Факултет за стране језике и лингвистику, Универзитет у малезији, Куала Лумпур, малезија

Ло Сау Чонг

Педагошки факултет, Универзитет у малезији, Куала Лумпур, малезија

Апстракт

КОНСТРУИРОВАНИЕ И ВАЛИДАЦИя ВОПРОСНИКОВ ДЛя ИССЛЕДОВАНИя мОТИВАЦИИ К ИзУчЕНИю

ИНОСТРАННОГО языКА

Лариса Никитина и Зурайда Мод Дон Факультет иностранных языков и лингвистики, малайский Университет, Куала Люмпур, малайзия

Ло Сау Чонг

Факультет образования, малайский Университет, Куала Люмпур, малайзия

Аннотация

В работе описываются шаги и этапы в конструировании вопросника для ис-следований мотивации к изучению второго или иностранного языка (Л2 моти-вации). Психометрические характеристики инструмента оценивались на осно-вании эксплоративного и конфирматорного факторального анализа. В иссле-довании учествовало 194 студентов. Результаты эксплоративного фактораль-ного анализа показали, что конструкт мотивации для обучения второму языку составляют четыре измерения: инструментальная ориентация, интегративная ориентация, посвященность и приложенные усилия. Результаты конфирма-торного факторального анализа подтвердили существование четырехизмери-тельной структуры. Выводы исследования, а также описанные шаги и этапы в развитии исследовательского инструмента для выявленения мотивации к обу-чению второму языку, могут помочь учителям, интересующимся вопросами, связанными с мотивацией к изучению иностранного языка, и имеют большую пользу для будущих исследований, в которых предметом анализа будет моти-вация к обучению второму языку.