CVJ / VOL 49 / AUGUST 2008 785

Article

Comparative study of the microbial profile from bilateral canine otitis

externa

Lis C. Oliveira, Carlos A.L. Leite, Raimunda S.N. Brilhante, Cibele B.M. Carvalho

Abstract — Fifty dogs with bilateral otitis externa were studied over a 10-month period. The exudates of both external ears were obtained, using sterile swabs, and microorganisms were isolated according to standard microbio-logical techniques. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Staphylococcus intermedius was done by the agar diffusion method. There was bacterial and/or fungal growth in all of the samples. These were all polymicrobial infections. Anaerobic bacteria were not isolated in any sample. The most common pathogens isolated were S. intermedius and

Malassezia pachydermatis. A statistically significant difference (P, 0.05) was observed in the isolation pattern between the right and left ears in 34 of the 50 animals (68%). High resistance rates of S. intermedius strains to penicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and clindamycin were found. The results suggest that in bilateral canine otitis externa, each ear should be cultured separately and considered as separate units.

Résumé —Étude comparative du profil microbien des otites externes bilatérales chez le chien. Cinquante chiens atteints d’otites externes bilatérales ont été suivis sur une période de plus de 10 mois. Les exsudats externes des 2 oreilles ont été prélevés avec des écouvillons stériles et les microorganismes ont été isolés selon les techniques microbiologiques usuelles. La susceptibilité antimicrobienne de Staphylococcus intermedius s’est effectuée par méthode de diffusion sur gélose. Tous les échantillons montraient une croissance bactérienne et/ou fongique. Dans tous les cas, il s’agissait d’infections polymicrobiennes. Aucune bactérie anaérobique n’a été isolée. Les pathogènes les plus fréquents étaient S. intermedius et Malassezia pachydermatis. Une différence statistiquement significative (P, 0,05) a été observée dans les modèles d’isolement entre les oreilles droites et gauches chez 34 des 50 animaux (68 %). Des taux élevés de résistance des souches de S. intermedicus à la pénicilline, l’ampicilline, l’érythromycine, la tétracycline et la clindamycine ont été observés. Les résultats permettent de présumer que dans l’otite externe bilatérale du chien, des cultures devraient être faites pour chaque oreille et que celles-ci devraient être considérées comme des entités séparées.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Can Vet J 2008;49:785–788

Introduction

Otitis externa (OE) is the most common disease of the ear canal in dogs and it has a multifactorial etiology. Microorganisms most frequently isolated from canine OE are Staphylococcus intermedius and Malassezia pachydermatis (l), although many other agents have been described. Despite advances in thera-peutic approachs, canine OE remains, in many cases, refrac-tory to treatment because of the complexity of the etiological

agents and the emergence of resistance to antibiotics among the microorganisms involved.

Many studies have described the isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles in canine OE. Some of them have used samples collected from only 1 ear per animal (2), others have used samples collected from 1 or both ears and considered them as different samples (3). In Brazilian veterinary clinics, when a dog has bilateral OE, a sample is usually taken from the most affected ear for antimicrobial susceptibility evaluation, the results are then used to treat both ears. However, a few studies of bilateral canine OE have compared the isolation of the patho-gens involved and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from both ears (4,5). The aim of this study was to compare the isolation patterns of samples collected from both ears in cases of bilateral canine OE and to study the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of the prevalent strains.

Materials and methods

Over a period of 10 mo (2003), 50 stray dogs with bilateral OE were studied. The dogs were taken from the streets and sent to

Department of Pathology and Legal Medicine (Oliveira, Carvalho) and Department of Pathology and Legal Medicine — Medical Mycology Specialized Center (Brilhante), Federal University of Ceará, DPML/UFC 60441-750 Fortaleza-CE, Brazil; Department of Veterinary Medicine — Federal University of Lavras, Lavras-MG, Brazil (Leite).

Address all correspondence to Dr. Lis C. Oliveira; e-mail: lisveterinaria@yahoo.com.br

786 CVJ / VOL 49 / AUGUST 2008

A

RT

IC

L

E

the Zoonoses Control Center of Fortaleza City/Ceará State — Brazil. All animals showed clinical signs of bilateral OE. The criteria for inclusion were clinical signs of OE (lesions on the ear, pain, balance alterations, itch) and abnormal findings on otoscopy (hemorrhagic lesions, ulceration of the tegument, pres-ence of foreign bodies, erythema, partial or total obstruction, otorrhoea, and alteration of the morphology of the timpanic membrane).

The exudates of both external ears were obtained, using sterile swabs. A total of 100 clinical samples were collected and used for cytological examination, bacterial culture and susceptibility testing, and fungal culture. Bacteriological and fungal studies were performed in the microbiology laboratory of the Federal University of Ceará. Total transfer time to the laboratory was not more than 2 h.

For aerobic and facultative strains, the specimens were cul-tured on blood agar (Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood), mannitol salt agar, MacConkey agar, and brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Wade Road, Bassingstoke, Hampshire, UK). The cultures were incubated at 35°C–37°C for 24 to 48 h.

Samples obtained for anaerobic culture were inoculated into brain heart infusion agar — supplemented with 5% sheep blood, hemin (5 mg/mL), and menadione (1 mg/mL) — and bacteroides bile esculin agar (Oxoid). The cultures were incu-bated at 35°C–37°C in anaerobic conditions. The anaerobic environment was obtained by using a commercially available gas generator envelope for anaerobiosis (Probac do Brasil, Produtos bacteriológicos, São Paulo-SP, Brazil).

For fungal isolation, the samples were inoculated into Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA), SGA supplemented with 0.05% chloramphenicol, SGA supplemented with 0.05% chloram-phenicol and 0.05% cycloheximide, and Dixon’s agar. They were kept at room temperature for 15 d.

Bacterial species were identified by Gram morphological and biochemical characteristics, as described by Murray et al (6). Fungal isolates were identified by their macroscopic and microscopic morphology, according Sidrim and Moreira (7).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of S. intermedius was per-formed by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar, according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (8). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 was included as a quality control. The disks used (Oxoid) were amikacin (30 mg), ampicillin (10 mg), kanamycin (30 mg), cefalotin (30 mg), cefoxitin (30 mg), ciprofloxacin (5 mg), clin-damycin (2 mg), chloramphenicol (30 mg), enrofloxacin (5 mg), erythromycin (15 mg), gentamicin (10 mg), imipenem (10 mg), neomycin (30 mg), oxacillin (1 mg), penicillin (10 units), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazol (25 mg), ticarcillin (30 mg), tobramycin (10 mg), tetracycline (30 mg), and vancomycin (30 mg).

The hypothesis test for parameters p binomial distribution was used to investigate significant differences between the iso-lation profile from the left and right ears of the same animal. Differences were considered significant at P, 0.05.

Results

One hundred clinical specimens from 50 dogs with bilateral OE were studied. The most frequent clinical signs were pres-ence of lesions on the pinna (72%), hemorrhagic lesions (87%), ulceration of the tegument (80%), and foreign bodies (43%). Otoscopical examination revealed rupture of the tympanic membrane in 18% of the dogs.

There was bacterial and/or fungal growth in all samples. The agents most frequently isolated were S. intermedius and

M. pachydermatis (Table 1). A single microorganism was pres-ent in 18% of the samples. Two microorganisms were isolated in 62% of the samples, and 3 or more were present in 20% of the samples. The most frequent association observed was

S. intermedius1 M. pachydermatis (54.8%). Although, most frequently, the same species of microorganisms were isolated from both ears, some differences were observed in the association pattern between the right and left ears in 34 of the 50 animals (68%) (Table 2). This difference was considered statistically significant (P , 0.05). Results from anaerobic culture were negative for all the samples studied.

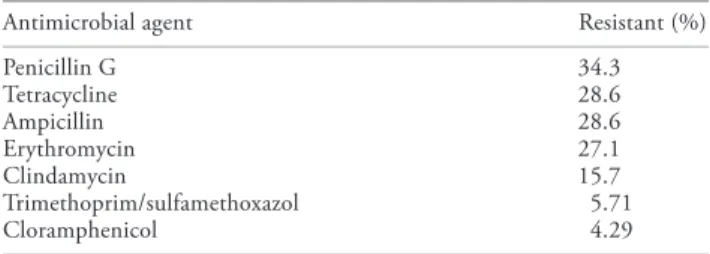

Antimicrobial resistance to at least 1 antimicrobial agent was detected in 56% of the S. intermedius strains and resistance to more than 2 antimicrobial agents was observed in 45% of all isolates. The less effective antimicrobial agents were penicillin G, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and clindamycin (Table 3).

Discussion

To the author’s knowledge, this is the 1st study in Brazil to com-pare the isolation pattern from both ears in bilateral canine OE. The results showed differences in the isolation pattern in 68% of the animals studied. This difference was statistically signifi-cant (P, 0.05). These results are very important in selecting the therapeutic approach and suggest that, in bilateral canine OE, each ear should be cultured separately and considered as a unit. This procedure should help to resolve the refractory cases of chronic canine OE.

Recently, Graham-Mize and Rosser (5) compared the isolated microorganisms and their antimicrobial sensitivity in dogs with

Table 1. Frequency with which agents were isolated in bilateral canine otitis externa

n

Bacterial isolate

Staphylococcus intermedius 70

Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus 11

Proteus mirabilis 7

Klebsiella pneumoniae 5

Staphylococcus hyicus 5

Staphylococcus aureus subsp. anaerobius 4

Enterobacter sp. 4

Pseudomonas aeruginosa 3

Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. coagulans 3

Streptococcus sp. 3

Staphylococcus sp. 2

Escherichia coli 1

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia 1

Fungal isolate

Malassezia pachydermatis 73

Candida albicans 3

Aspergillus sp. 4

Candida parapsilosis 2

CVJ / VOL 49 / AUGUST 2008 787 A RT IC L E

OE; they described a similarity between isolated microorganisms in 80% of the samples. Our results show this similarity in only 32% of the cases. This difference could be explained by geo-graphic characteristics that influence the auditory microbiota, by animal origin (stray dogs 3 pet dogs), and maybe by different criteria used to classify the OE cases.

Many studies have described the presence of S. intermedius

and M. pachydermatis as components of the normal microbiota of the canine ear and have shown their association with canine OE (1,2), and, as in this study, others have found S. intermedius

to be the bacterium most frequently isolated (9).

The predominance of polimicrobial infection in canine OE observed in this study is in agreement with that observed in previous studies (4,10).

There has been increasing interest in S. intermedius in dogs. It has been demonstrated at both the molecular and immunological levels that virulent strains of S. intermedius possess a substantial enterotoxigenic potential (11) and produce toxins with superan-tigenic properties (12). These findings become important when considering the evident zoonotic potential of this species (13).

Malassezia pachydermatis is a common component of the microbiota of the domestic carnivore’s skin. During the past

Table 2. Microorganisms isolated from bilateral canine otitis externa

Sample Left ears Right ears

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50

Staphylococcus intermedius 1 Proteus mirabilis S. intermedius 1 Malassezia pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 Klebsiella pneumoniae 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. aureus anaerobius 1 Streptococcus viridans 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis 1 Candida albicans S. intermedius

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. aureus aureus 1 K. pneumoniae S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

Enterobacter cloacae

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. aureus aureus 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. intermedius 1 Aspergillus flavus S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. intermedius S. aureus aureus

Staphylococcus coagulase-negative 1 M. pachydermatis

S. aureus aureus

S. intermedius 1 K. pneumoniae 1 P. mirabilis 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. hyicus

S. intermedius 1 P. mirabilis 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. schleiferi 1 A. flavus

S. intermedius 1 P. mirabilis 1 M. pachydermatis S. hyicus 1 M. pachydermatis

S. hyicus 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. aureus aureus 1 M. pachydermatis

Staphylococcus coagulase-positive 1 P. mirabilis 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis 1 Candida parapsilosis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. aureus aureus 1 M. pachydermatis

S. aureus aureus 1 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia 1 M. pachydermatis

Staphylococcus intermedius 1 Proteus mirabilis S. intermedius 1 Malassezia pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 Escherichia coli 1 Klebsiella pneumoniae 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. aureus anaerobius 1 Streptococcus viridans 1 M. pachydermatis 1 Candida albicans

S. aureus anaerobius 1 Streptococcus C 1 M. pachydermatis 1 Candida tropicalis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 P. aeruginosa S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 S. aureus aureus 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 Enterobacter cloacae S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 C. albicans

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis 1 C. tropicalis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius

S. intermedius 1 Aspergillus niger 1 A. fumigatus

Staphylococcus coagulase-negative 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 P. mirabilis 1 M. pachydermatis

S. aureus aureus 1 K. pneumoniae 1 Enterobacter aerogenes 1 M. pachydermatis

S. aureus aureus S. intermedius S. intermedius

S. schleiferi 1 M. pachydermatis S. hyicus 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. aureus aureus

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 Aspergillus terreus S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

Staphylococcus coagulase-positive 1 M. pachydermatis

P. aeruginosa 1 M. pachydermatis S. schleiferi 1 M. pachydermatis S. aureus aureus 1 M. pachydermatis P. mirabilis 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis 1 Candida parapsilosis S. hyicus 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

S. intermedius 1 Enterobacter gergoviae 1 M. pachydermatis S. intermedius 1 M. pachydermatis

788 CVJ / VOL 49 / AUGUST 2008

A

RT

IC

L

E

decade, Malassezia species have also emerged as increasingly important pathogens in neonates in human intensive care nurseries (14).

As expected, a high level of resistance to penicillin (34.3%) and ampicillin (28.6%) was observed, because of the b-1actamases produced by S. intermedius, similar to that described in the literature (1,2,4). The resistance of Staphylococci

strains to tetracyclines in this study, which is in agreement with that observed by Shimizu et al (15), may be a reflection of the excessive use of this drug in veterinary medicine, especially for dermatological diseases. Macrolides are widely used in veterinary medicine for the treatment of bacterial infections. Concerning the resistance of S. intermedius to erythromycin (27.1%) and c1indamycin (15.7%) in this study, these results are similar to those of some workers (16) but differ from those of others (17). This discrepancy may be due to regional differences in the use of antimicrobial agents.

This study emphasizes the need for bacterial culture, spe-cies identification, and susceptibility testing in order to choose appropriate antimicrobial agents and to improve the clinical therapeutic approach for canine OE.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Oliveira was involved in the conception and design of the project, collection of the samples, the bacterial cultures, and writing the manuscript. Dr. Leite was involved in the concep-tion and design of the project, the analysis and interpretaconcep-tion of the data, and revising the manuscript. Dr. Brilhante was involved with the fungal cultures. Dr. Carvalho was involved in the conception and design of the project, the analysis and interpretation of the data, the bacterial cultures, and revision of

the manuscript. CVJ

References

1. Kiss G, Radvayi SZ, Szigeti G. New combination for the therapy of canine otitis externa. I — Microbiology of otitis externa. J Small Anim Pract 1997;38:51–56.

2. Lilenbaum W, Veras M, Blum E, Souza GN. Antimicrobial susceptibility

of Staphylococci isolated from otitis externa in dogs. Lett Appl Microbiol

2000;31:42–45.

3. Barrasa JLM, Gomez PL, Lama ZG, Junco MTT. Antibacterial suscep-tibility patterns of Pseudomonas strains isolated from chronic canine otitis externa. J Med Vet B 2000;47:191–196.

4. Cole LK, Kwochka KW, KawaJki JJ, Rillier A. Microbial flora and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of isolated pathogens from the horizontal ear and middle ear dogs with otitis media. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;212:534–538.

5. Graham-Mize CA, Rosser EJ Jr. Comparision of microbial isolates and susceptibility from external ear canal of dogs with otitis externa. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40:102–108.

6. Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, et al. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 8th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: ASM Pr, 2003;2:113. 7. Sidrim JJC, Moreira JLB. Fundamentos clínicos e laboratoriais da

micologia médica. 1st ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan S.A., 1999:287 p.

8. NCCLS. 1997. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals; Tentative Standard. NCCLS Document M31-T. Wayne, Pennsylvania, 19087, USA.

9. Hoekstra KA, Paulton RJL. Clinical prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus intermedius in dogs. J Appl Microbiol 2002;93:406–413.

10. Nobre MO, Castro AP, Nascente PS, Ferreiro L, Meireles MCA. Occurrence of Malassezia pachydermatis and other infectious agents as cause of external otitis in dogs from Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil (1996,1997). Braz J Microbiol 2001;32:243–247.

11. Becker K, Keller B, Eiff C, et al. Enterotoxigenic potential of

Staphylococcus intermedius. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001;67:

5551–5557.

12. Hendricks A, Schuberth H, Schueler K, Lloyd DH. Frequency of superantigen-producing Staphylococcus intermedius isolates from canine pyoderma and proliferation-inducing potential of superantigens in dogs. Res Vet Sci 2002;73:273–277.

13. Teraucki R, Sato H, Hasegawa T, Yamaguchi T, Aizawa C, Maehara N. Isolation of exfoliative toxin from Staphylococcus intermedius and its local toxicity in dogs. Vet Microbiol 2003;94:19–29.

14. Chang HJ, Miller HL, Watkins N, et al. An epidemic of Malassezia

pachydermatis in an intensive care nursery associated with colonization

of health care workers’ pet dogs. N Eng J Med 1998;338:706–711. 15. Shimizu A, Wakita Y, Nagase S, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of

Staphylococcus intermedius isolated from healthy and diseased dogs. J Vet

Med Sci 2001;63:357–360.

16. Boerlin P, Burnens AP, Frey J, Ku1mert P, Nicolet J. Molecular epi-demiology and genetic linkage of macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance in Staphyloccus intermedius of canine origin. Vet Microbiol 2001;79:155–169.

17. Hariharan H, Coles M, Poole D, Lund L, Page R. Update on antimi-crobial susceptibilities of bacterial isolates from canine and feline otitis externa. Can Vet J 2006;47:253–255.

Table 3. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus intermedius

(n = 70) isolated in bilateral canine otitis externa

Antimicrobial agent Resistant (%)

Penicillin G 34.3

Tetracycline 28.6

Ampicillin 28.6

Erythromycin 27.1

Clindamycin 15.7

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazol 5.71