Porto

Biomedical

Journal

h tt p://w w w . p o r t o b i o m e d i c a l j o u r n a l . c o m /Review

article

A

biopsychosocial

approach

to

the

interrelation

between

motherhood

and

women’s

excessive

weight

Ana

Henriques

a,∗,

Ana

Azevedo

a,baEpidemiologyResearchUnit(EPIUnit)–InstituteofPublicHealth,UniversityofPorto,Porto,Portugal

bDepartmentofClinicalEpidemiology,PredictiveMedicineandPublicHealth,UniversityofPortoMedicalSchool,Porto,Portugal

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received27November2015 Accepted16February2016 Keywords: Excessiveweight Motherhood Weightcontrola

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Portugalischaracterizedbyahighprevalenceofoverweightandobesityamongwomen,whoseweight increasesmostrapidlyinearlyadulthood.Individualgeneticfeaturesandbehaviours,alongwithsocial, culturalandenvironmentalfactorsinteractincomplexrelationshipswithbodyweightandwithits variationthroughouttime.Motherhoodmaytriggeranincreaseinweight,potentiallyinfluencingthe associationsbetweenexcessiveweightandseveralotherhealthdeterminants.Takingintoaccountthe qualityofprenatalcarewithinPortugal’shealthcaresystem,regardingcoverageandsuccessinimproved outcomes,wetheoreticallydemonstratewhypregnancyandmotherhoodshouldbeseenasopportunities forpreventionandwhyadeeperknowledgeabouttheinterplayofbiological,socialand psychologi-caldeterminantsofweightatthisstageoflifecanbeusefultodesignmoreeffectiveweightcontrol interventionstowardsthispopulation.

©2016PublishedbyElsevierEspa ˜na,S.L.U.onbehalfofPBJ-Associac¸˜aoPortoBiomedical/Porto BiomedicalSociety.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Women’sweightbefore,duringandafterpregnancy

Motherhoodis oneofthemostchallengingexperiences that canoccurinwomen’slifeand itcanbeconcomitantly distress-ingandmeaningful.Theseambivalentfeelingsarenotnecessarily aproblem,butmoreresearchisneededtounderstandtheir speci-ficitiesandhowtheycaninteractwithweightmanagementinthis periodoflife.Thegrowingnumber ofobesewomenworldwide hasmanyimplications,notonlyonmother’shealthoutcomesbut alsofortheirchildren,asdemonstratedbytheassociationbetween prepregnancyobesityandcertainmajorbirthdefects1andahigher

likelihoodofhavingmacrosomicinfants.2Additionally,caesarean

deliveryriskisincreasedby50%inoverweightwomenandismore thandoubleforobesewomencomparedtowomenwithnormal bodymassindex(BMI).3

Thepostpartumperiodcanbecriticalforthedevelopmentof obesityinmidlife.Evidenceconsistentlyshowsthatexcessive ges-tationalweightgain(GWG)contributestohigherpostpartumbody weight4–6andthatoverweightandobesewomenhavemorethan

doublethechancetoexceedtheweightgainrecommendations duringpregnancythanotherBMIgroups.2,7Moreover,excessive

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:alhenriques@med.up.pt(A.Henriques).

GWGisassociatedwithabdominaladiposity8yearsafterdelivery, whichmayincreaseawoman’sriskofcardiovascularandmetabolic diseases.8

Several pregnancy cohort studies from developed countries havereportedindependentdirectassociationsbetween prepreg-nancybodyweightorBMIandpostpartumweightretention.9,10

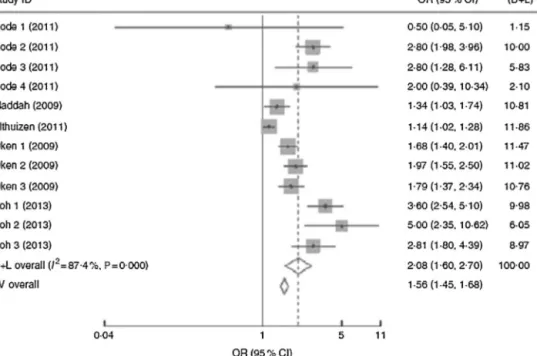

However,arecentmeta-analysisanalyzedtheassociationofGWG orprepregnancyBMIwithpostpartumweightretentionand,as illustratedinFig.1,GWG,ratherthanprepregnancyBMI, deter-minestheshorter-orlonger-termpostpartumweightretention. Whenpostpartumtimespanswerestratifiedinto1–3months,3–6 months,6–12months,12–36monthsand≥15years,the associa-tionbetweeninadequateGWGandpostpartumweightretention fadedovertimeandbecameinsignificantafter15years.11

Most studiesconducted sofarfocus onweight changeonly until thefirst year postpartum, and few studies have obtained serial measurements for longer periods to assess patterns of weightchange.Characterizationoftheinterrelationshipsbetween prepregnancybodyweight,GWG andpostpartumweight reten-tion is essential for a deeper knowledge of weight changes afterpregnancyandobesityratesinchildbearingage.Giventhe modifiable nature of this risk factor, thepreconception, prena-tal, and postpartum periods may present critical windows to implement interventions to prevent weight retention and the developmentofoverweightandobesityinwomenofchildbearing age.12

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2016.04.003

2444-8664/©2016PublishedbyElsevierEspa ˜na,S.L.U.onbehalfofPBJ-Associac¸˜aoPortoBiomedical/PortoBiomedicalSociety.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCC BY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Fig.1. Forestplotofthestudiesontheriskofpostpartumweightretentionof≥5kgforwomenwithexcessivegestationalweightgain(GWG)vs.womenwithadequate GWG.Thestudy-specificORand95%CIarerepresentedbythegreysquareandhorizontalline,respectively;thesizeofthedatamarker(greysquare)isproportionaltothe weightofthestudyinthemeta-analysis(note:weightsarefromrandom-effectsanalysis).ThecentreoftheopendiamondpresentsthepooledORanditswidthrepresents thepooled95%CI.11ReprintedwiththepermissionofCambridgeUniversityPress.

Increasingparitycontributestothelong-termdevelopmentof obesityinwomen13–15butthisrelationshipdiffersbymaternalBMI

inyoungadulthood,numberofbirths,race-ethnicityandlengthof follow-up.FindingsfromarepresentativecohortfromtheUnited StatesofAmerica(USA)showedthatblackandwhiteprimiparae andmultiparaetendedtohavegreaterBMIincreasesthan nulli-paraeover10years,thisassociationbeingstrongeramongwomen withhighBMIbeforepregnancy.However,25yearslater,thesame studyshowedthat onlyblack womenwho wereoverweight at baselineanddeliveredmorethan onechildgained significantly moreweightthanthosenotgivingbirth.16Womenoftenreport

theirobesitytobetriggeredbypregnancy–asmanyas40–50% in oneSwedish study. Yet,for 30% of thewomen in the same study,pregnancywasassociatedwithweightloss.17Additionally,

placeofresidence,ethnicity,aswellasindividualsocioeconomic position(SEP)andlifestylefactorscanconsiderablyexplain this association.18,19Allofthesedataalludetoacomplexparity–weight

relationshipforwomenwitharangeofconfoundingfactorsthatact acrossthelifecourse,withthepossibilityforfurthervariations.20

Thus, further researchis needed toconfirm the links between parityandweightgain,aswellasmoreinformationregarding con-foundersofthisassociationframedinsocialandcurrenteconomic conditions.

Theriskofweightgainisnotequalthroughoutallpregnancies. Inlargecohortstudies,whencomparingnulliparouswith primi-parouswomen,weightgainduetochildbearingwasgreatestafter thefirstbirth,andweightgainwasgreaterwithincreasingbaseline maternalbodyweight.Averageweightgainassociatedwith hav-ingafirstchildwas3–6kgamongwomenwhowereoverweight beforepregnancy,andabout1kgamongwomenwithnormalBMI. Afterthefirst pregnancy, weightgain is smallerin subsequent pregnancies.12,21,22Furthermore,multiparityispositively

associ-atedwithabdominalgirthfrompreconceptiontoseveralyearsafter delivery.21,23

Despite somedisparities, evidence supports that substantial weightgainassociatedwithchildbearingisanimportantrisk fac-torforthedevelopmentofoverweightandobesityinadultwomen.

Futurestudiesshouldidentifywomenmoresusceptibletobenefit frominterventionstopreventweightgainandwhicharethe crit-icalperiodstointervenemosteffectively:before,duringorafter pregnancy.

Theimpactofpsychosocialdeterminantsonweight,around motherhood

Sincesocial10andpsychologicalcharacteristics24haveimpact

onmaternalexcessiveweight,thepsychosocialcontextshouldbe studiedindepth.Areviewoftheimplicationsofbodyimageand socioeconomicpositionisprovidedbelow.

Bodyimage

Pregnancy,due toitsconcomitantchanges in bodysize and shape,canhaveasignificantimpactonawoman’sbodyimage.25

Thisisoftenthefirsttimeweightgainisexpectedandaccepted andsomewomenviewbodychangesastransientanduniquetothe childbearingendeavoursotheyareabletoassimilatethesechanges withoutdistress.26

Researchresultsonbodyimageinpregnancyhavebeen con-tradictory,withsomestudieshighlightingthat womenareable toassimilatethebodilychangesofpregnancywithoutanegative shiftinbodyimagesatisfaction(BIS),27,28andotherstudies

find-ingadecreasedBISduringpregnancy29andpostpartum.30Also,

prepregnancyBMIhasanimpactonBISduringpregnancy,with overweightwomenreportinganincreaseintheirsatisfactionand womenwithnormalBMIreportingadecrease.29Thosewhohad

beenoverweightbeforetheirpregnancymayviewtheirpregnancy asexcusingthemfromunpleasantcommentsorfeeling uncomfort-ableinactivitiesexposingtheirbody,suchasswimming.31

Inthepostpartumperiod,despitesomevariation,bodyimage isgenerallymorenegative,whenwomen’sconstructionsoftheir postpartumbodyindicatethatoncethebabywasborn,theyno longer perceived any excuse to not adhere to their perceived sociallyconstructedidealsilhouette.32Harrisandcolleaguesalso

foundthatwomenwhowerelesssatisfiedwiththeirbodies post-partumhadsignificantlygreaterlongtermweightgainsthanthose womenwhodisplayednoincreaseindissatisfactionwiththeir bod-iesafterpregnancy.14Onepossiblereasonforthisdisappointment

isthatwomen(especiallyprimiparouswomen)tendtoexpectthat theirbodieswillreturntotheirpre-pregnancyweightandshape shortlyafterthebirthoftheirchild.33

Arecentreviewsynthesizedtheexistingqualitativeliterature describingwomen’sexperiencesoftheirpregnancyand postpar-tumbodyimage. Hodgkinsonandcolleagues25 highlightedthat

women’sperceptionoftheirpregnancybodyimageisvariedand dependsonthestrategiestheyusetoprotectagainstsocial con-structionsoffemalebeauty.Womenoftenperceivedthepregnant body tobeout oftheircontrol andas transgressingthe physi-calmanifestationofthesociallyconstructedideal,againstwhich they tried to protect their BIS. Body dissatisfaction dominated thepostpartumperiod,emphasizingthewomen’sneedfor addi-tionalsupportatthismoment.Moreover,healthprofessionalsare reportedtofeeluncomfortableaboutdiscussingweightasanaspect ofbodyimageduetolackofknowledgeandfearofbeing consid-eredinsensitive.34However,sinceduringpregnancywomenare

morereceptivetoconversationsaboutweight-relatedaspectsof theirbodyimage,communicationskillstrainingcouldincrease pro-fessionals’confidenceinexploringwomen’sbodyimageinorder toimprovetheirweightmanagementstrategiesindependentlyof theirBMI.25

WhileitseemsclearthatBISbeforepregnancyhasa consid-erableimpactonpostpartumweightchanges,furtherresearchis neededtoassessifthissameconstructcaninfluenceweightovera longer-term.

Socioeconomicposition

Femalereproductivehealthishighlysensitivetothephysical andsocialenvironmentthroughoutlife.Womenarecurrentlyless likelytobemarriedandmorelikelytobesingleorcohabiting,35,36

morewomenareremainingchildlessorhavingfewerchildrenand theproportionofwomen’slivesspentrearingtheirchildrenhas beenreduced.37Ifsocialfactorschange,theirimpactonwomen’s

reproductivelifecanalsochange;therefore,adeepstudyofthis relation,togetherwithpsychologicalandbiologicalattributes,is stillachallengetobefaced.

MaternalSEPisknowntobeastrongcorrelateofnumerous maternalandchildhealthoutcomes.LowindividualSEP(e.g. edu-cationandincome)hasbeenassociatedwithadversepregnancy andbirthoutcomes38,39anddelayedprenatalcare.40Arecentlarge

population-basedstudycomparedthedirectionandmagnitudeof individualandneighbourhoodsocialinequalitiesacrossmultiple maternalandchildhealthoutcomes(maternalandinfanthealth statusindicators;prenatalcare;maternalexperienceoflabourand delivery;neonatalmedicalcare;andpostpartuminfantcareand maternalperceptionsofhealthcareservices)andrevealedthatSEP measureshadstrongerassociationswithoutcomesbelongingto thehealthstatusofthemotherandinfant,asopposedtotheother groups.Themagnitudeofmaternalandchildhealthinequalities washigherwhenindividual-levelSEPwasusedthanwhen con-sideringneighbourhoodSEP.Inparticular,educationshowedthe greatestgradientscomparedtohouseholdincome,neighbourhood SEP,andcombinedSEP(combinationoflowandhighindividual andneighbourhoodSEP).41

ArelationbetweenSEPandobesityhasbeenwellestablished foralongtime,42alsoinchildbearingwomen,43withthosewho

havealowerSEPbeingtheoneswithahigherriskofbeingobese. However,somespecificitiesofthisassociationconsideringyoung adultwomenremainunclear.Inadulthood,reproductionmayhave anaddedinfluenceonobesityriskinwomen,althoughresearchis

lackingonhowadultinfluencescombine,namelysocialand psy-chologicalones,forthedevelopmentofexcessiveweightinthis particularperiod.

Additionally,researchonchildhoodgrowthhaspointedtothe possibilitythatearlylifemaybeanimportantstageinthe devel-opmentofobesityandlongitudinalstudiesconsistentlyshowthat alowerSEPinchildhoodincreasestheriskofexcessiveweightin adulthood.44TheseassociationsbetweenchildhoodSEPandadult

healtharealsoobservedinthecontextofmotherhood.IntheBritish 1958birth cohortstudy,45 it wasobservedthat,as thelevelof

povertyinchildhoodincreases,theproportionofwomenhaving theirfirstbabybytheageof20alsoincreases.

Thiscontinuityindisadvantagethroughoutlifeisanimportant partofthelinkbetweenchildhooddisadvantageandpooradult health,withSEPacrosschildhoodand adulthoodemergingasa stronger predictorofadulthealth thanSEPatanyone pointin time.45

Socialtrajectoryisalifelongevolutionofthevolumeand com-positionofanindividual’scapital(social,cultural,economicand/or symbolic),combinedwithhis/herparents’assetvolumeand struc-tureandcanbedescribedasupward,downwardorstationary.46

Most of the findings concerningobesity and socioeconomic characteristicshavebeenbasedonwomen’sSEPinadulthoodbut, recently,evidenceisemergingabouttheimpactof intergenera-tionalsocialtrajectorytakingintoaccountalifecourseperspective. Inordertostudytheinfluenceofsocialclassinchildhood,young adulthoodandmiddleage,andintergenerationalmobility,onadult centralandtotalobesity,astudywasconductedusinga population-basedbirthcohort.Inwomenat53years,father’ssocialclasswas inverselyassociatedwithallmeasuresofobesity,bothadultsocial classes(atages26and43years)wereinverselyassociatedwithall obesitymeasuresatage53andwomenwithanupward intergener-ationalsocialmobilityhadlowerlevelsofcentralandtotalobesity comparedwiththosewhoremainedinthesamesocialclassastheir father.47

Changes in social circumstances,or intergenerational move-ment betweensocial classes,might entaila transitionin terms ofprioritiesand resourcesrelatedtoweightandappearance,or ashiftinexperienceofsocialnormsregardingtheappealof par-ticularbodytypes,48particularlywhenconsideredinthecontext

ofwomen whohave recentlygivenbirth.Knowing thatsociety influenceswomen’sperceptionofgoodorbadappearance,future studiesshouldbetterassessthesocialdeterminantsofBISin child-bearingwomen,consideringalifecourseapproach.

Motherhoodasanopportunityforprevention

Some authors defend that the preconception period should be seen as a privileged time for prediction and prevention of noncommunicablediseases,thus notonly improvingpregnancy outcomesandmaternalhealth,butalsopromotinglong-term ben-eficialeffectsforboththemotherandthechild.49Prepregnancy

weightlosscanreduceobesity-relatedcomplications,whichcan haveaconsiderableimpactonimprovingobesity-relatedperinatal complications–gestationaldiabetesmellitus,hypertensive disor-ders,macrosomia,andlargeforgestationalagebabies.50

Women’s health in Portugal hasexperienced a huge overall improvementsincethelate1970sandtheimplementationofthe National Health System, which ensures all citizens nearly free accesstoprimarycarecentresandpublichospitals.51Moreover,

prenatalcareisoneofPortugal’shealthcaresystem’smost suc-cessfulareas,withpractically100%coverageandadequateprenatal careinthevastmajorityofpregnancies.52However,astudy

per-formed in the north of the country showed that, whilst good prenatalsurveillanceexists,only27%ofthepuerperalwomenhad

• The romanticized image • The motherself • Type of mothering received • The influential ‘others’ • The ‘wished-for’ baby • Relationship with baby • Partner’s involvement • Self and others • Confidence in body • Labour as indicator of motherliness • Dealing with uncertainty • Information seeking Parental self-efficacy Concept of motherhood Mother-infant dyad Anticipated social support

Fig.2. Themesandsub-themesidentifiedwithinthe‘Expectationsandbeliefsaboutmotherhoodviews’.57ReprintedwiththepermissionofElsevier.

preconceptioncare.53Also,astudyperformedinmothersofthe

GenerationXXIbirthcohortshowedanadversecardiovascularrisk profilesincethepreconceptionperiod,54supportingtheideathat

interventionsshouldstartearlierinchildbearingwomen.

Thelabel“teachable moment”hasbeenusedtocharacterize lifetransitionsorhealtheventsthatincreaseperceptionsof per-sonalriskandoutcomeexpectancies,promptstrongaffectiveor emotional responses, and redefine self-concept or social roles. Inotherwords,a cognitiveresponseprecedesmotivation,skills acquisitionandself-efficacythatinturn,increasethelikelihood ofceasingadverselifestyles.Additionalkeyfactorstoconsiderare predisposingfactorssuchasage,dispositionalandcultural charac-teristicsthatmayinfluenceanindividual’scognitiveandemotional response.Pregnancyhasbeenwidelyreferred toasa teachable momentbecauseofmothers’strongmotivationtoprotectthe well-beingofthefoetusandstrongsocialpressuretoavoidunhealthy habits,suchassmokingduringpregnancy.55,56

Somepsychological issues should also be highlighted when discussing a pregnancy’simpact onwomen’s life. A qualitative studyexploredbeliefsand expectationsaboutmotherhood, and the main themes are illustrated in Fig. 2. Since a discrepancy betweenwomen’sexpectationsandrealitywasfound,a psycho-logicalpreparation for motherhoodshouldbe consideredwhen preparingwomenfortheirnewrole.Suchpreparationpromotesa sensibleimageofmotherhood,theinfant,thenoveltyofthefuture andrelationshipswithothers,anddiscussingthesethemesmaybe particularlyrelevanttowomenvulnerabletopostnatal psycholog-icaladjustmentdifficulties.57

AccordingtoastudyperformedintheUnitedKingdombetween 1998and2003,therewasasignificantreductioninsmoking, alco-holconsumptionand intakeofcaffeinateddrinkswhen women becamepregnant,althoughlittlechangeoccurredinfruitsand veg-etablesintake.58InPortuguesemothers,althoughalmosthalfof

smokersceasedtobaccoconsumptionduringpregnancy, approxi-matelytwothirdsresumedsmokingwithin4yearsafterdelivery,59

leadingustobelievethat,althoughpregnancyenhancesthe per-ceivedneedofadoptinghealthylifestyles,thatdoesnotmeanthat healthyhabitswillpersistthroughouttime.Sincefertileagewomen arepronetochangehealthyhabitswhentheyreceivehealthcare provider’sadvices,60interventionstothissegmentofthe

popula-tionshouldberestructured,focusingmoreonwomen’sintrinsic motivationsandexpectations,whichisprovedtoresultin long-lastingbehaviourchange.61

Insummary, weightmanagement before, duringand after a pregnancyhasadvantages for both mother andchild.

Monitor-ingofprepregnancyBMI,GWG,andpostpartumweightwillallow theidentificationofwomenwhoaremoresusceptibleofhaving aninadequateweightthroughoutchildbearingyears. Preconcep-tionisanimportantperiodandobesewomenshouldbetargeted forinterventionbeforetheygetpregnantforthefirsttime. Like-wise,healthcareprovidersinvolvedinthecareofpregnantwomen shouldbetrainedtoprovideamoreeffectiveapproachforweight control.

Metabolicfeaturesafterpregnancy:thehealthyobesity phenotype

The numbersregarding obesity are alarming,largely due to itsassociationwithseveralcardiovascular diseases.However, a healthyobesephenotypehasbeenrecentlyidentifiedandthese individualsappeartobeatnoincreasedcardiovascularrisk.62,63

This clinical condition,termed benign obesityor metabolically healthyobesity,isrestrictedtoauniquesubsetoftheobese pop-ulationwhich, despiteexcessive BMI, are insulin sensitive and haveanormalbloodpressure,lipid,inflammationandhormonal profile.62–66 The relevance of establishing such a phenotype is

underlinedbydatathatsuggeststhatweightlossamonghealthy obese may adversely impact their favourable cardiometabolic profile.67

Theabsenceofauniformdefinitionforthissubtypeofobesity isoneofthemainlimitationsofthistopic,withprevalences rang-ingfrom6%to37%,68–70dependingonthecriteriatodefinethe

phenotype.However,evenwhenuniquecriteriaareused, consider-ablevariabilityintheprevalenceofhealthyobesityisfoundacross differentEuropeancountries71and,tothebestofourknowledge,

therearenoestimatesforPortugal.Normally,metabolicallyhealthy obesepersonshavefamilymemberswithuncomplicatedobesity, earlyonsetobesity,fastingplasmainsulinwithinanormalrange andanormaldistributionoftheexcessfat.72Additionally,some

lifestylefeaturesareassociatedwiththismetabolicprofile,suchas moderateandhigherlevelsofphysicalactivityandhigherdietary quality.70

Somecontroversyexistsconsideringtherelevanceofthis phe-notype.Arecentsystematicreviewandmeta-analysisshowedthat, comparedwithmetabolicallyhealthynormalweightindividuals, obesepersonsareatanincreasedriskofadverselong-term out-comesevenintheabsenceofmetabolicabnormalities,suggesting thatthereisnohealthypatternofincreasedweight.73Also,another

studythatevaluatedthe3-yearincidenceofcardiometabolicrisk factorsconcludedthat anincrease inBMI duringthefollow-up

period wassignificantly associated withthe occurrence of car-diometabolicalterations.74Moreresearchconcerningthissubject

isstillneededandlongerlongitudinalanalysesshouldbeprovided inordertoclarifyiftheseindividualsareprotectedduringtheir entirelifeorwhetherhealthyobesitysimplyrepresentsdelayed onsetofobesityrelatedcardiometabolicproblems.Also,mostof thestudiesthatassessedhealthyobesityusedsamplescomprising womenabove40yearsofage66,75,76andinformationconcerning

childbearingwomenisstilllacking.

Theincreaseindepositionoffatinabdominalvisceraladipose tissue is favouredafter pregnancy,due to increasedabdominal compliance,renderingwomenmoresusceptibletoabdominal obe-sity after childbirth.13 Abdominal fat distribution, visceral and

ectopicfataccumulationarealsokeycharacteristicsforthe devel-opmentofunhealthyobesity.77 Thus,itwould beinterestingto

characterizetheobesityphenotypein womenwho hada child, toassesstowhich extenttheirobesityis healthyor is convey-ing a higher risk of CVD,thus supportingor not the need for preventiveactiondirectedatthissegmentofthepopulation. Fur-therstudiesexaminingdifferentsubtypesofobesitywillallowfor understandingobesity’s heterogeneousnaturethat couldresult inmoreappropriateweightlossrecommendations,evenamong childbearingwomen.

Conclusion

Inconclusion,theaccumulatedevidencesuggeststhatthereare severalfactorsthatcouldleadachildbearingwomantobe over-weightor obeseand a biopsychosocialapproach contributesto understandtheserelationscomprehensively.

Pregnancyhasbeenwidelyreferredtoasateachablemoment andfutureresearchshouldidentifywomenmoresusceptibleto benefit from interventions to prevent weight gain during this period,preferably,startingatthepreconceptionperiod.BIS, socioe-conomiceconomiccharacteristicsacrossthelifespanandmetabolic featuresshouldbeconsideredwhendesigningfutureinterventions forweightmanagementtargetingthisspecificpopulationand lon-gitudinalresearchisneededinordertoassessiftheimpactofthese variablesonweightisobservedthroughouttime.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

AgrantfromFundac¸ãoparaaCiênciaeTecnologiaisgratefully acknowledged(SFRH/BD/72723/2010).

References

1.CorreaA,MarcinkevageJ.Prepregnancyobesityandtheriskofbirthdefects:an update.NutrRev.2013;71Suppl.1:S68–77.

2.BrawarskyP,StotlandNE,JacksonRA,Fuentes-AfflickE,EscobarGJ,Rubashkin N,etal.Pre-pregnancyandpregnancy-relatedfactorsandtheriskofexcessive orinadequategestationalweightgain.IntJGynaecolObstet.2005;91:125–31.

3.PoobalanAS,AucottLS,GurungT,SmithWC,BhattacharyaS.Obesityasan independentriskfactorforelectiveandemergencycaesareandeliveryin nulli-parouswomen–systematicreviewandmeta-analysisofcohortstudies.Obes Rev.2009;10:28–35.

4.HeX,HuC,ChenL,WangQ,QinF.Theassociationbetweengestationalweight gainandsubstantialweightretention1-yearpostpartum.ArchGynecolObstet. 2014;290:493–9.

5.OlsonCM,StrawdermanMS,HintonPS,PearsonTA.Gestationalweightgainand postpartumbehaviorsassociatedwithweightchangefromearlypregnancyto 1ypostpartum.IntJObesRelatMetabDisord.2003;27:117–27.

6.EndresLK,StraubH,McKinneyC,PlunkettB,MinkovitzCS,SchetterCD,etal. Postpartumweightretentionriskfactorsandrelationshiptoobesityat1year. ObstetGynecol.2015;125:144–52.

7.Chasan-TaberL,SchmidtMD,PekowP,SternfeldB,SolomonCG,Markenson G.PredictorsofexcessiveandinadequategestationalweightgaininHispanic women.Obesity(SilverSpring).2008;16:1657–66.

8.McClureCK,CatovJM,NessR,BodnarLM.Associationsbetweengestational weightgainandBMI,abdominaladiposity,andtraditionalmeasuresof car-diometabolicriskinmothers8ypostpartum.AmJClinNutr.2013;98:1218–25.

9.HarrisHE,EllisonGT,HollidayM,LucassenE.Theimpactofpregnancyonthe long-termweightgainofprimiparouswomeninEngland.IntJObesRelatMetab Disord.1997;21:747–55.

10.ParkerJD,AbramsB.Differencesinpostpartumweightretentionbetweenblack andwhitemothers.ObstetGynecol.1993;81Pt1:768–74.

11.RongK,YuK,HanX,SzetoIM,QinX,WangJ,etal.Pre-pregnancyBMI,gestational weightgainandpostpartumweightretention:ameta-analysisofobservational studies.PublicHealthNutr.2014:1–11.

12.GundersonEP.Childbearingandobesityinwomen:weightbefore,during,and afterpregnancy.ObstetGynecolClinNorthAm.2009;36:317–32,ix.

13.GundersonEP,SternfeldB,WellonsMF,WhitmerRA,ChiangV,Quesenberry CPJr,etal.Childbearingmayincreasevisceraladiposetissueindependentof overallincreaseinbodyfat.Obesity(SilverSpring).2008;16:1078–84.

14.HarrisHE,EllisonGT,ClementS.Relativeimportanceofheritablecharacteristics andlifestyleinthedevelopmentofmaternalobesity.JEpidemiolCommunity Health.1999;53:66–74.

15.LuotoR,MannistoS,RaitanenJ.Ten-yearchangeintheassociationbetween obesityandparity:resultsfromtheNationalFINRISKPopulationStudy.Gend Med.2011;8:399–406.

16.AbramsB,HeggesethB,RehkopfD,DavisE.Parityandbodymassindexin US women:aprospective25-yearstudy.Obesity(SilverSpring).2013;21: 1514–8.

17.RossnerS.Weightgaininpregnancy.HumReprod.1997;12Suppl.1:110–5.

18.LeeSK,SobalJ,FrongilloEA,OlsonCM,WolfeWS.Parityandbodyweightin theUnitedStates:differencesbyraceandsizeofplaceofresidence.ObesRes. 2005;13:1263–9.

19.Wolfe WS, Sobal J, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. Parity-associated body weight:modificationbysociodemographicandbehavioralfactors.ObesRes. 1997;5:131–41.

20.MishraG,KuhD.Commentary:therelationshipbetweenparityandoverweight –alifecourseperspective.IntJEpidemiol.2007;36:102–3.

21.GundersonEP,MurtaughMA,LewisCE,QuesenberryCP,WestDS,SidneyS. Excessgainsinweightandwaistcircumferenceassociatedwithchildbearing: theCoronaryArteryRiskDevelopmentinYoungAdultsStudy(CARDIA).IntJ ObesRelatMetabDisord.2004;28:525–35.

22.RosenbergL,PalmerJR,WiseLA,HortonNJ,KumanyikaSK,Adams-Campbell LL.Aprospectivestudyoftheeffectofchildbearingonweightgainin African-Americanwomen.ObesRes.2003;11:1526–35.

23.TroisiRJ,WolfAM,MasonJE,KlinglerKM,ColditzGA.Relationofbodyfat dis-tributiontoreproductivefactorsinpre-andpostmenopausalwomen.ObesRes. 1995;3:143–51.

24.BogaertsA,DevliegerR,VandenBerghBR,WittersI.Obesityandpregnancy,an epidemiologicalandinterventionstudyfromapsychosocialperspective.Facts ViewsVisObgyn.2014;6:81–95.

25.HodgkinsonEL,SmithDM,WittkowskiA.Women’sexperiencesoftheir preg-nancyandpostpartumbodyimage:asystematicreviewandmeta-synthesis. BMCPregnancyChildbirth.2014;14:330.

26.RichardsonP.Women’sexperiencesofbodychangeduringnormalpregnancy. MaternChildNursJ.1990;19:93–111.

27.DaviesK,WardleJ.Bodyimageanddietinginpregnancy.JPsychosomRes. 1994;38:787–99.

28.BoscagliaN,SkouterisH,WertheimEH.Changesinbodyimagesatisfaction dur-ingpregnancy:acomparisonofhighexercisingandlowexercisingwomen.Aust NZJObstetGynaecol.2003;43:41–5.

29.FoxP,YamaguchiC.Bodyimagechangeinpregnancy:acomparisonofnormal weightandoverweightprimigravidas.Birth.1997;24:35–40.

30.JenkinW,TiggemannM.Psychologicaleffectsofweightretainedafter preg-nancy.WomenHealth.1997;25:89–98.

31.OgleJP,TynerKE,Schofield-TomschinS.Jointlynavigatingthereclamationof the“womanIusedtoBe”:negotiatingconcernsaboutthepostpartumbody withinthemaritaldyad.ClothTextResJ.2011;29:35–51.

32.UptonRL,HanSS.Maternityanditsdiscontents–“Gettingthebodyback”after pregnancy.JContempEthnogr.2003;32:670–92.

33.TiggemannM.Bodyimageacrosstheadultlifespan:stabilityandchange.Body Image.2004;1:29–41.

34.SmithDM,CookeA,LavenderT.Maternalobesityisthenewchallenge;a qual-itativestudyofhealthprofessionals’viewstowardssuitablecareforpregnant womenwithaBodyMassIndex(BMI)≥30kg/m2.BMCPregnancyChildbirth.

2012;12:157.

35.CopenCE,DanielsK,MosherWD.FirstpremaritalcohabitationintheUnited States:2006–2010NationalSurveyofFamilyGrowth.NatlHealthStatReport. 2013:1–15.

36.CopenCE,DanielsK,VespaJ,MosherWD.FirstmarriagesintheUnitedStates: datafromthe2006–2010NationalSurveyofFamilyGrowth.NatlHealthStat Report.2012:1–21.

37.TheEURO-PERISTATproject.Healthandcareofpregnantwomenandbabiesin Europein2010.Paris:EURO-PERISTAT;2012.

38.MorgenCS,BjorkC,AndersenPK,MortensenLH,NyboAndersenAM. Socioeco-nomicpositionandtheriskofpretermbirth–astudywithintheDanishNational BirthCohort.IntJEpidemiol.2008;37:1109–20.

39.MortensenLH,Helweg-LarsenK,AndersenAM.Socioeconomicdifferencesin perinatalhealthanddisease.ScandJPublicHealth.2011;39Suppl.:110–4.

40.Feijen-deJongEI,JansenDE,BaarveldF,vanderSchansCP,SchellevisFG, ReijneveldSA.Determinantsoflateand/orinadequateuseofprenatal health-care in high-income countries: a systematic review. EurJ Public Health. 2012;22:904–13.

41.DaoudN,O’CampoP,MinhA,UrquiaML,DzakpasuS,HeamanM,etal.Patterns ofsocialinequalitiesacrossmultiplepregnancyandbirthoutcomes:a compar-isonofindividualandneighborhoodsocioeconomicmeasures.BMCPregnancy Childbirth.2014;14:393.

42.SobalJ,StunkardAJ.Socioeconomicstatusandobesity:areviewoftheliterature. PsycholBull.1989;105:260–75.

43.WardleJ,WallerJ,JarvisMJ.Sexdifferencesintheassociationofsocioeconomic statuswithobesity.AmJPublicHealth.2002;92:1299–304.

44.HardyR,WadsworthM,KuhD.Theinfluenceofchildhoodweightand socioe-conomicstatusonchangeinadultbodymassindexinaBritishnationalbirth cohort.IntJObesRelatMetabDisord.2000;24:725–34.

45.Graham H, Power C. Childhood disadvantage and health inequalities: a frameworkforpolicybasedonlifecourseresearch.ChildCareHealthDev. 2004;30:671–8.

46.BourdieuP.Distinction:asocialcritiqueofthejudgmentoftaste.Cambridge, MA:HarvardUniversityPress;1984.

47.LangenbergC,HardyR,KuhD,BrunnerE,WadsworthM.Centralandtotal obesityinmiddleagedmenandwomeninrelationtolifetimesocioeconomic status:evidencefromanationalbirthcohort.JEpidemiolCommunityHealth. 2003;57:816–22.

48.McLarenL,KuhD.Women’sbodydissatisfaction,socialclass,andsocialmobility. SocSciMed.2004;58:1575–84.

49.HadarE,AshwalE,HodM.Thepreconceptionalperiodasanopportunityfor pre-dictionandpreventionofnoncommunicabledisease.BestPractResClinObstet Gynaecol.2015;29:54–62.

50.Schummers L, HutcheonJA, Bodnar LM,LiebermanE, Himes KP. Risk of adversepregnancyoutcomesbyprepregnancybodymassindex:a population-basedstudytoinformprepregnancyweightlosscounseling.ObstetGynecol. 2015;125:133–43.

51.BentesM,DiasC,SakellaridesC,BankauskaiteV.Healthcaresystemsin tran-sition:Portugal.Copenhagen:WHORegionalOfficeforEuropeonBehalfofthe EuropeanObservatoryonHealthSystemsandPolicies;2004.

52.LunetN,RodriguesT,CorreiaS,BarrosH.Adequacyofprenatalcareasamajor determinantoffolicacid,iron,andvitaminintakeduringpregnancy.CadSaude Publica.2008;24:1151–7.

53.PinheiroL,SilvaN,PereiraA.PreconceptionandprenatalcareinSãoMarcos Hospital,athirdlevelPortugueseHospital.SaúdeInfantil.2009;31:59–62.

54.AlvesE,CorreiaS,BarrosH,AzevedoA.Prevalenceofself-reported cardiovascu-larriskfactorsinPortuguesewomen:asurveyafterdelivery.IntJPublicHealth. 2012;57:837–47.

55.McBrideCM,EmmonsKM,LipkusIM.Understandingthepotentialof teach-ablemoments:the caseofsmokingcessation. HealthEduc Res.2003;18: 156–70.

56.PhelanS.Pregnancy:a“teachablemoment”forweightcontrolandobesity pre-vention.AmJObstetGynecol.2010;202:e1–8.

57.StanevaA,Wittkowski A.Exploringbeliefs andexpectations about moth-erhood in Bulgarian mothers: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2013;29: 260–7.

58.CrozierSR, RobinsonSM,Borland SE, GodfreyKM, CooperC, InskipHM. Dowomenchangetheirhealthbehavioursinpregnancy?Findingsfromthe SouthamptonWomen’sSurvey.PaediatrPerinatEpidemiol.2009;23:446–53.

59.AlvesE,AzevedoA,CorreiaS,BarrosH.Long-termmaintenanceofsmoking cessationinpregnancy:ananalysisofthebirthcohortgenerationXXI.Nicotine TobRes.2013;15:1598–607.

60.BombardJM,RobbinsCL,DietzPM,ValderramaAL.Preconceptioncare:the perfectopportunityforhealthcareproviderstoadviselifestylechangesfor hypertensivewomen.AmJHealthPromot.2013;27Suppl.:S43–9.

61.TeixeiraPJ, SilvaMN, Mata J, Palmeira AL,Markland D. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weightcontrol. Int JBehav Nutr PhysAct. 2012;9:22.

62.Karelis AD. Metabolically healthy but obese individuals. Lancet. 2008;372:1281–3.

63.WildmanRP.Healthyobesity.CurrOpinClinNutrMetabCare.2009;12:438–43.

64.Aguilar-SalinasCA,GarciaEG,RoblesL,Ria ˜noD,Ruiz-GomezDG,García-Ulloa AC,etal.Highadiponectinconcentrationsareassociatedwiththemetabolically healthyobesephenotype.JClinEndocrinolMetab.2008;93:4075–9.

65.BluherM.Thedistinctionofmetabolically‘healthy’from‘unhealthy’obese indi-viduals.CurrOpinLipidol.2010;21:38–43.

66.StefanN,KantartzisK,MachannJ,SchickF,ThamerC,RittigK,etal.Identification andcharacterizationofmetabolicallybenignobesityinhumans.ArchIntern Med.2008;168:1609–16.

67.Karelis AD, MessierV, Brochu M,Rabasa-LhoretR. Metabolically healthy but obese women: effect of an energy-restricted diet. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1752–4.

68.BrochuM,TchernofA,DionneIJ,SitesCK,EltabbakhGH,SimsEA,etal.Whatare thephysicalcharacteristicsassociatedwithanormalmetabolicprofiledespite ahighlevelofobesityinpostmenopausalwomen?JClinEndocrinolMetab. 2001;86:1020–5.

69.KukJL,ArdernCI.Aremetabolicallynormalbutobeseindividualsatlowerrisk forall-causemortality?DiabetesCare.2009;32:2297–9.

70.PhillipsCM,PerryIJ.Doesinflammationdeterminemetabolichealthstatusin obeseandnonobeseadults?JClinEndocrinolMetab.2013;98:E1610–9.

71.vanVliet-OstaptchoukJV,NuotioML,SlagterSN,DoironD,FischerK,FocoL, etal.Theprevalenceofmetabolicsyndromeandmetabolicallyhealthyobesityin Europe:acollaborativeanalysisoftenlargecohortstudies.BMCEndocrDisord. 2014;14:9.

72.Sims EA. Are there persons who are obese, but metabolically healthy? Metabolism.2001;50:1499–504.

73.KramerCK,ZinmanB,RetnakaranR.Aremetabolicallyhealthyoverweightand obesitybenignconditions?Asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis.AnnIntern Med.2013;159:758–69.

74.Bobbioni-HarschE,PatakyZ,MakoundouV,LavilleM,DisseE,AnderwaldC, etal.Frommetabolicnormalitytocardiometabolicriskfactorsinsubjectswith obesity.Obesity(SilverSpring).2012;20:2063–9.

75.PhillipsCM,DillonC,HarringtonJM,McCarthyVJ,KearneyPM,FitzgeraldAP, etal.Definingmetabolicallyhealthyobesity:roleofdietaryandlifestylefactors. PLOSONE.2013;8:e76188.

76.VelhoS,PaccaudF,WaeberG,VollenweiderP,Marques-VidalP.Metabolically healthyobesity:differentprevalencesusingdifferentcriteria.EurJClinNutr. 2010;64:1043–51.

77.DespresJP,LemieuxI.Abdominalobesityandmetabolicsyndrome.Nature. 2006;444:881–7.