It is commonly used to describe the phenomenon in all Basque dialects whereby, under certain circumstances, an addressee that is not an argument of the verb is systematically encoded in all (declarative) conjugated verb forms of the main clause. The research for this paper was carried out as part of EFL (Empirical Foundations of Linguistics) GD1 "Typology and Marking of Information Structure and Grammatical Relations". The Indo-European use of the so-called 'ethical dative', which is by no means unique to this language family, as it is also attested in at least two languages of the North-Eastern Caucasus, Chechen and Ingush (Molochieva 2010, Nichols 2011), can also be considered as an example of allocution, although not ( fully) grammaticalized, and has indeed been suggested as one possible source of allocution in Basque (Alberdi 1995).

As for the source of allocutive marking, in some of the languages examined in Antonov (in preparation) it seems to lie in the domain of pronouns, incorporated into the conjugated verb form of what was originally, and sometimes still is. second person dative pronominal clitic. This is a phenomenon, symmetrical to allocutivity, in which the speaker, and not the listener, is encoded in verbal forms, regardless of whether he/she is an argument of the verb. And then there are cases like Beja, where the origin of the allocutive clitic is unknown, although it could arguably have something to do with gender marking in personal pronouns (Appleyard.

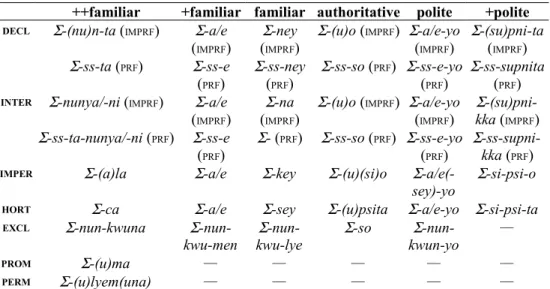

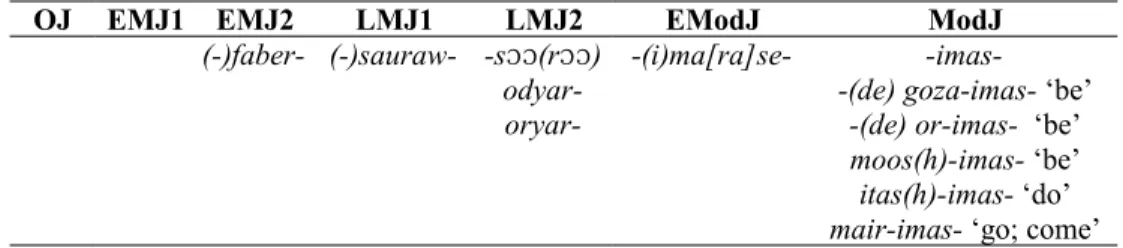

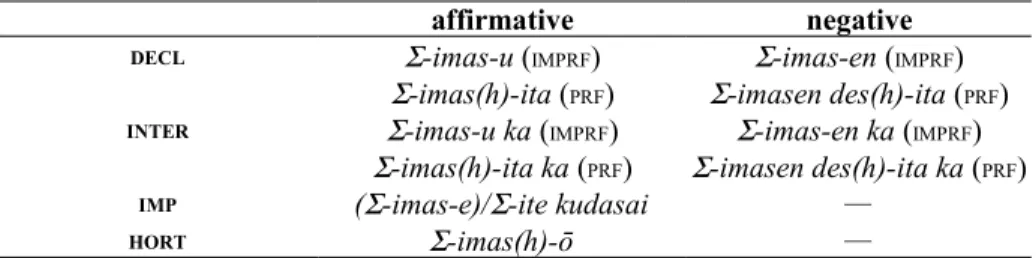

It mainly serves the purpose of expressing the speaker's respect for the listener, regardless of whether he/she is a participant in the verb or not. Modern Japanese utterances can basically be marked or unmarked for allocutivity, which in this language is associated with respect for the listener, regardless of whether he/she is a participant in the verb or not, and is marked by adding a suffix to the verb root -( i)mas - (cf. table 1 and examples hereafter). Polite style originates in elevating expression through a process of shifting the target of respect or humility from the subject of a sentence to the hearer (respect) or the speaker (humility), ultimately interpreted as a characterization of the speaking situation or the relationship between the speaker and hearer .

Given the non-obvious nature of this lack of connection, it might be useful to illustrate its proven use.

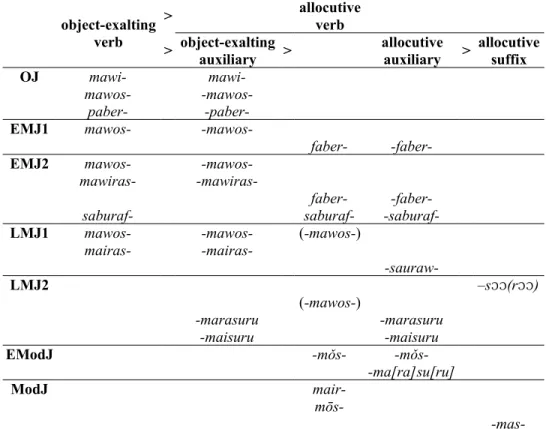

In fact, there is also a second person singular pronoun (m)(i)masi, which must be derived from this honorific, but whose referent need not be someone for whom the speaker must show respect (cf. Nevertheless, unlike In Basque and possibly Beja (cf. 4.1) it is not the case that this second-person pronoun is grammaticalized as a verb clitic in an allocutive function, since Japanese has always been an overall dependent marking language type and that the direction of derivation (verb > verbal noun > pronoun) seems much more plausible than the reverse. help?) with the meaning 'to be present'. Unlike OJ, in EMJ this verb is used exclusively as an allocutive verb and auxiliary verb (cf. Vovin.

DEM to FOC gate wide-CNV FOC. becomes-CNV-AUX:ALLOC:RSP-FIN. why be_such-ADN thing INTER do-CNV-AUX:ALLOC:RSP-HYP:ADN. The second of these, saburaf-, is attested both as an object raising verb with the meaning 'to serve (a superior) [an object raising verb]' and as an allocative and auxiliary verb (Vovin. The second of the two EMJ allocative verbs and auxiliaries passes into LMJ in to the form of the allocative suffix -sauraw-, which is later further reduced to -s (r ) ɔɔ ɔɔ (sign of the LMJ epistolary style) (Kitahara et al. 2001).

The EModJ allocative suffix ma(ra)su(ru) has its source in the object-raising verb and the auxiliary ma(w)iras- 'to give (to a superior)' already attested in EMJ (Kitahara et al. 2001). . This then develops into the EModJ allocative ending and is thus the ultimate source of the ModJ allocative ending -(i)mas-.

Evolution of allocutive markers in Japanese

3 Allocutivity in Korean

- in Old Korean

- in Late Middle Korean

- in Early Modern Korean

- Evolution of allocutive markers in Korean

As already mentioned in 3, given the insufficient attestation of Korean before the invention of the alphabet in the mid-15th century, it is difficult to assert with certainty the absence of allocative verbs and/or auxiliaries and/or suffixes. in pre-Late Middle Korean. We know that Old and Early Middle Korean had subject- and object-raising verbs and auxiliaries, just as Late Middle Korean did, but we are unable to find any trace in the textual record of any similar form with allocation before this later stage. of the language. In fact, it is preserved in the modern superpolitical allocative ending -(su)pni- which has as its source a combination of the Late Middle Korean object-.

Allocutive forms do not seem to exist in Old Korean, but due to the scarcity of documents and the complexity of the script used in the extant texts (especially in the poems of the Silla period [7c-10c] called Hyangka), it is impossible to be absolutely sure. In what follows, only the use of the allocutive and the object-elevating suffixes is illustrated, as these later yield one complex allocutive suffix in early modern Korean. Examples (26)-(28) illustrate the use of the allocutive suffix -ngi-. go-HON:MOD-NMLZ stay:HON-HON:MOD-NMLZ-DAT today. be_different-FUT-ALLOC:RSP-PRT-INTER.

It is also possible to combine both markers, the object-elevating and the allocative ending, which will later give birth to a new allocative ending, which is the direct ancestor of the modern suprapolitical (allocative) ending -(su)pni. - (cf. 3.2.4). In Early Modern Korean, the Late Middle Korean object ending is no longer used alone, but only in combination with the processive -no- and the phonetically eroded form of the Late Middle Korean allocative suffix -ngi- as a new allocative ending: -sop-no-i < sop-no-ngi (Lee & Ramsey 2011). It illustrates the use of this suffix as an equivalent of the Early Modern Japanese allocative suffix discussed above.

So we have seen that the modern, super-polite allocutive suffix -(su)pni- preserves a trace (although quite difficult to recognize) of the Late Middle Korean allocutive ending -ngi-, in a fossilized complex suffix that was initially respectful of both indicated the object as respect for the object and towards the addressee, but in the phase of early modern Korean it was already reanalyzed as a super polite allocutive suffix. It is very likely that the object-elevating suffix was subsequently reanalyzed, as in Japanese, as a show of respect towards the addressee, which, in the case of Korean, led to the disappearance of all productive object-elevating suffixes from later stages of the language. . This is all the more likely because Basque is surrounded by Romance languages, almost all of which do not have standardized variants in which this use of the dative is well attested.

In the case of Beja, the origin of the apparently optional allocutive marker is not so clear, but could possibly be related to the domain of the personal pronoun and could have as its ancestor a clitic (accusative and/or dative) pronoun, even though there is a particle of a similar kind also cannot be excluded. On the other hand, the significance of this outdated allocutive marker was almost certainly completely forgotten by the end of the LMK period. Honorary systems are usually late developments and, regardless of the question of the existence of a common Korean-Japanese protolanguage, the present markers clearly developed at a relatively recent time in the history of both languages.

The many structural similarities between Japanese and Korean may be precisely due to such contact on the Korean peninsula before the migration of Japanese speakers to Japan in the early second half of the first millennium BCE. HM Hamamatsu chūnagon monogatari (Tale . of the Hamamatsu chūnagon) (1064? ) KK Kojiki Kayō (Songs of the Kojiki) (712).