The simulation shows the results in terms of deviation from the economic situation without holding the World Cup. The WC year itself should provide additional employment for the equivalent of 8,250 man-years. As part of the decision-making process for their candidacy, both the Netherlands and Belgium made forecasts of the impact of the World Cup on the economy.

In Belgium, the Federal Planning Office, at the request of the cabinet, made a review of the economic activity generated by the World Cup. Thus, only the supplementary part of the investment can be considered as an expenditure effect of the World Cup. Thus, the investment can be fully attributed to the World Cup, and it is also considerable.

The largest version amounts to 560 million euros and is based on the experience of the 2006 World Cup in Germany. In this economic analysis, we have not taken into account the amounts of investment in public infrastructure near the stadiums, as they cannot be attributed to the World Cup based on the available information (in particular the FPS Mobility and Transport information). In actual practice, it is therefore difficult to attribute any major investment in public infrastructure solely to the eventual organization of the World Cup.

Public expenditure on security

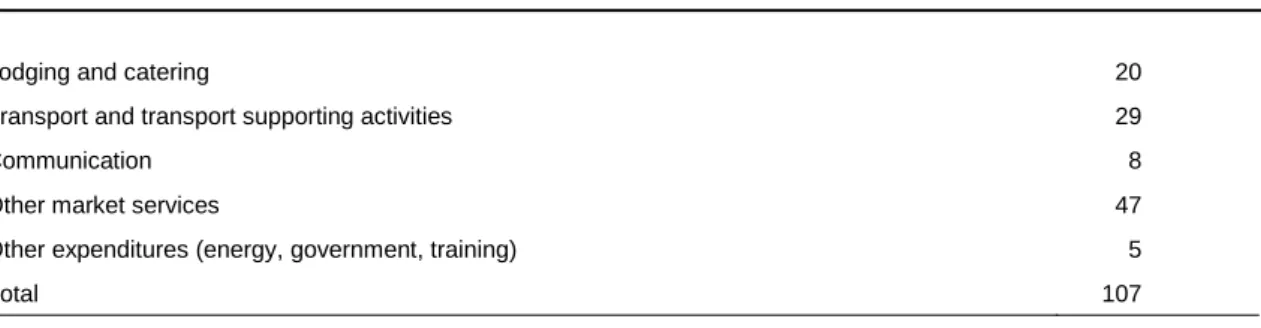

Tourist expenditure by supporters

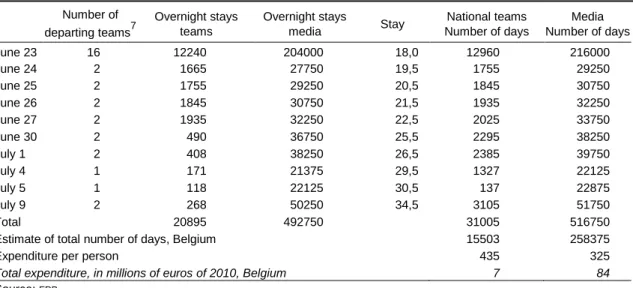

Therefore, the following derivation should not be interpreted as a definitive calculation of expected tourism effects. Therefore, it is possible that a blocking effect occurs. 2008), among others, estimates the percentage of tourists who would have also visited the host country in the absence of the World Cup. In the calculation of the effect of tourist expenses, only the visitors of 28% of the available rooms (38,000) can be included.

Based on these assumptions, only 263,000 of the 796,000 occupied seats can be included in the tourist effect. The latter accounts for 38% and therefore represents a large margin of error for the calculation of the expected tourist expenditure. According to Schütte (2008), this would account for 62% of the total effect, while the visitors of fan festivals represent the remaining 38%.

The derivation of the interval between the minimum and maximum power is discussed in the following section. The result of the baseline scenario is comparable to the result of previous research regarding the economic effects of the World Cup in 2006. According to NBTC (2008), the occupancy rate of Amsterdam hotels in the busiest tourist month of the year rises to 90%, scoring 9 percentage points above the average.

During that period, the number of available rooms halves, but the NBTC (2008) does not mention what is actually the busiest month of the year. According to the federal government (2006), they would have been almost 100% for every match of the 2006 World Cup. Part of the foreign visitors would also have booked a holiday in Belgium in the absence of a World Cup.

Finally, a more precise calculation of the expenses for the visitors to fan parties could be made. In the calculation, it is simply assumed that fanfests generate 38% of the total expenditure, in accordance with Kurscheidt et al.

Accommodation expenditure by national teams, journalists and other media representatives

Macroeconomic simulation based on input-output analysis

The principle of input-output analysis

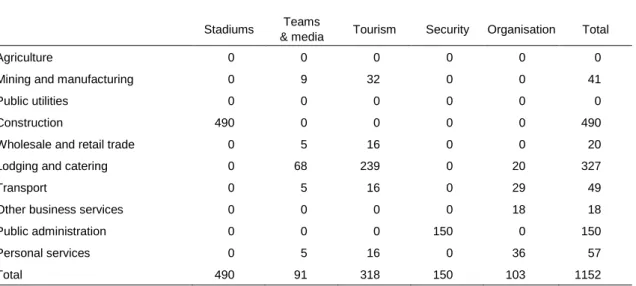

In the baseline scenario, the total spending impulse amounts to €1.15 billion, almost half of which comes from investments in stadiums spread over eight years. It also assumes that security costs for the Confederations Cup will amount to €25 million in 2017. The effects of Tables 8 and 9 must therefore be regarded as accumulative effects, indicating a sum of the expenses made during a period of eight years.

The analysis can also be applied to the expenses of teams and media and security costs, but the effect on total expenses is expected to be small. The investments in stadiums are fully attributed to the construction industry, although a small part can be attributed to business services (architects and engineers). 75% of tourist expenditure by national teams, media and supporters is attributed to hotels, bars, restaurants and possibly campsites, while the remaining quarter under industrial products (shopping expenditure of tourists), retailers' gross margins, transport and personal services ( culture and leisure).

As a result, the construction and accommodation/hospitality industry can be credited with 71% of the boost.

Economic effects of the expenditure impetus

In the starting point, the spending impulse of DKK 1.15 billion leads to EUR for a total production of 2.14 billion. EUR, which is 1.8 times the actual momentum. This factor is also called the multiplier and shows the amount of total output generated per euro of the impulse. Considering the previously mentioned investment distribution, € 1.016 billion is realized from annual shares of € 155 million up to and including 2016 and with a subsequent remainder of € 88 million.

It goes without saying, especially in an open economy like the Belgian example, that part of the supplies come from abroad. In the base scenario, this part amounts to 288 million euros with a multiplier of 0.23, which means that an expenditure incentive of 1,000 euros means the import of goods and services in the amount of 230 euros. Conversely, part of the drive itself is exports, such as tourist expenditure and organizational costs, as these are generated by foreign fans and FIFA itself.

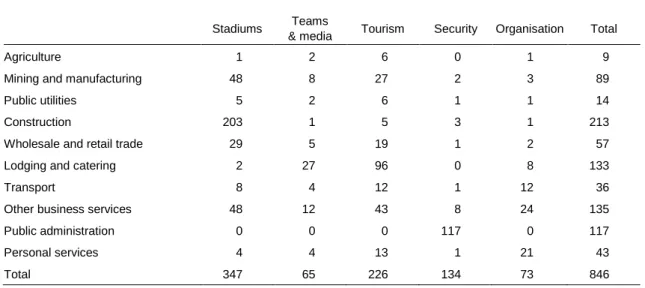

The effect on added value is realized by labour, capital and entrepreneurship deployed in Belgium, both in the industries in which the impulse occurs and in the supply industries. It represents 75% of the initial boost, or €846 million in the baseline scenario, and is the cumulative contribution to GDP realized over eight years. The main effect on the economy is value added, the main factor determining GDP.

8 The word 'equivalent' is used emphatically here because part of the effect is achieved through overtime for existing staff, such as police officers. In this context, the multiplier actually has a different dimension than other effects, as it shows the effect on employment per million euros of stimulus spending. In other words, every million spent on the World Cup leads to 11.9 job years of employment.

This large industry includes communications, banking, insurance, leasing, automation, research and professional services, among others, and could gain a total of 1,408 job years as a result of the World Cup. For the public administration, this figure is even higher, but a large part will probably be realized in the form of police overtime.

Total macrosectoral effects: results of the HERMES

- Application of the HERMES model

- Hypotheses

- Results

- Conclusion

- References

- Annex

These expenditures in the base scenario (see Table 8), which are directly attributable to the World Cup in 2018, served as input to the HERMES model in the form of exogenous shocks to the corresponding macroeconomic variables. We considered the fact that the timing of the construction work may not be synchronous in all cities due to the organization of the FIFA Confederations Cup in 2017, which, as already mentioned before, acts as a final test for the World Cup 2018. The federal for example, the government will contribute to the possible construction of a new national stadium in Brussels, but the exact amount of the contribution is not yet known.

Economic activity generated by export growth in the Netherlands (the other host country) was not simulated. The simulation shows that the macroeconomic effects will be very limited in the run-up to the tournament because they result exclusively from the construction works attributable to the 2018 World Cup. It is therefore not surprising that during the period GDP should hardly change compared to basic level.

The direct and induced effects will mainly come from the LOC's acquisition of goods and services (just over EUR 100 million in 2010 prices) and especially from the expected significant tourism expenditure resulting from the event on Belgian territory: as a reminder (see Table 13), this tourist export is estimated at just over DKK 400 million. EUR. In addition, 2018 should show a significant increase in public spending (security spending): a 0.13% increase compared to the baseline. On the other hand, and in contrast to the above-mentioned effects, which will diminish from 2019, the increase in economic activity in 2018 should have a markedly positive effect on employment, which will continue throughout the period 2019-2020.

During the run-in period, the number should be 500 units higher on average and on an annual basis compared to the baseline. During the entire period 2011-2020, the additional employment with respect to the baseline simulation should amount to 9,100 units. The smaller impact on employment compared to the input-output analysis can be explained by a larger effect on imports in the HERMES model (e.g. +0.08% in 2018) on the one hand, and the shock effect of productivity in 2018 in this model (+0.08%, see Table 14), which was not taken into account in the IOM, on the other hand.13.

The relative weakness of the macroeconomic effects is not surprising, as the total amount of expenditure related to the event in the period 2011-2018 is approximately EUR 1.1 billion. It represents a modest boost to the economy, which by comparison is smaller than the usual estimate for the Olympics - the only other major international sporting event comparable to the World Cup - in terms of both media and organizational budgets. As Sterken (2006, p. 388) already pointed out, the Olympic Games really require significantly more investments in the time before the event, both in stadiums (due to the variety of sports) and in public infrastructure.

A somewhat significant effect is predicted only for the year of GDP according to the HERMES model and 0.12% of GDP according to the IOM, which represents about 0.5 billion euros.