w w w . r b o . o r g . b r

Original

Article

The

WHO

Surgical

Safety

Checklist:

knowledge

and

use

by

Brazilian

orthopedists

夽

Geraldo

da

Rocha

Motta

Filho

a,b,∗,

Lúcia

de

Fátima

Neves

da

Silva

c,d,e,

Antônio

Marcos

Ferracini

b,f,

Germana

Lyra

Bähr

c,g,haShoulderandElbowSurgeryCenter,InstitutoNacionaldeTraumatologiaeOrtopedia,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

bDepartmentofOrthopedicsandTraumatology,UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

cInstitutoNacionaldeTraumatologiaeOrtopedia,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

dEscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública,Fundac¸ãoOswaldoCruz,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

eFundac¸ãoGetúlioVargas,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

fOrthopedicsandTraumatologyService,HospitalSanRafael,Salvador,BA,Brazil

gAudenciaSchoolofManagement,Nantes,France

hUniversidadeFederaldoRiodeJaneiro,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received7August2013 Accepted16August2013

Keywords:

Patientsafety Medicalerrors Surgicalprocedures Operative

Checklist

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:TheresearchexaminedBrazilianorthopedists’degreeofknowledgeoftheWorld HealthOrganizationSurgicalSafetyChecklist.

Methods:Avoluntarysurveywasconductedamongthe3231orthopediststakingpartin

the44thBrazilianCongressofOrthopedicsandTraumatologyinNovember2012,usinga questionnaireontheuseofWHOSurgicalSafetyChecklist.Astatisticalanalysiswasdone uponreceiptof502completedquestionnaires.

Results:Amongthe502orthopedists,40.8%reportedtheexperienceofwrongsiteorwrong patientsurgeryand25.6%ofthemindicated“miscommunication”asthemaincauseforthe error.35.5%oftherespondentsdonotmarkthesurgicalsitebeforesendingthepatientto theoperatingroomand65.3%reportedlackofknowledgeoftheWorldHealthOrganization (WHO)SurgicalSafetyChecklist,fullyorpartially.72.1%oftheorthopedistshaveneverbeen trainedtousethisprotocol.

Discussion:Medicalerrorsaremorecommoninthesurgicalenvironmentandrepresent

ahighrisktopatientsafety. Orthopedicsurgeryisa highvolumespecialtywithmajor technicalcomplexityandthereforewithincreasedpropensityforerrors.Mosterrorsare avoidablethroughtheuseoftheWHOSurgicalSafetyChecklist.Thestudyshowedthat 65.3%ofBrazilianorthopedistsareunawareofthisprotocol,despitetheeffortsofWHOfor itsdisclosure.

©2013SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditora Ltda.Allrightsreserved.

夽

WorkperformedattheNationalInstituteofTraumatologyandOrthopedics,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil. ∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:geraldomotta@terra.com.br(G.d.R.MottaFilho).

Palavras-chave:

Seguranc¸adopaciente Errosmédicos

Procedimentoscirúrgicos Operatórios

Listadeverificac¸ão

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo: ApesquisaanalisouograudeconhecimentodoProtocolodeCirurgiaSegurada OMSpelosortopedistasbrasileiros.

Métodos: Foifeitaumapesquisavoluntáriaentreos3.231ortopedistasparticipantesdo44◦ CongressoBrasileirodeOrtopediaeTraumatologia(CBOT),emnovembrode2012,pormeio deumquestionáriosobreousodoProtocolodeCirurgiaSeguradaOMS.Apósorecebimento de502questionáriosrespondidos,foifeitaaanáliseestatísticadosresultados.

Resultados: Dentre os 502ortopedistasrespondentes,40,8% relataramter vivenciadoa

experiênciadecirurgiaempacienteouemlocalerradoe25,6%delesapontaram“falhas decomunicac¸ão”comoresponsáveispeloerro.Dototalderespondentes,36,5%relataram nãomarcarolocaldacirurgiaantesdeencaminharopacienteaocentrocirúrgicoe65,3%, desconhecertotalouparcialmenteoProtocolodeCirurgiaSeguradaOMS.Desses ortope-distas,72,1%nuncaforamtreinadosparaousodoprotocolo.

Discussão: Errosmédicosocorrem,principalmenteemambientecirúrgico,erepresentam

umaltoriscoparaaseguranc¸adospacientes.Considerandoqueacirurgiaortopédicaé umaespecialidadedegrandevolumeefrequentementedealtacomplexidade,envolveuma probabilidadegrandedeocorrênciadeerros,amaioriaevitávelpormeiodousodo Proto-colodeCirurgiaSeguradaOMS.Naamostrapesquisada,restouevidenciadoque65,3%dos ortopedistasbrasileirosdesconhecemtalprotocolo,apesardosesforc¸osdaOMSparaasua divulgac¸ão.

©2013SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublicadoporElsevier EditoraLtda.Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Theprincipleofprimumnonnocere(firstofall,donotcause harm),whichisattributedtoHippocrates,demonstratesthe concern regarding the risks in medical practice that has existedsinceancienttimes.

Medicalsocietiesaround theworld haverecognizedthe problemofmedicalerrorsandhaveledthemovementtoavoid themandestablishtheconceptsofsafesurgery.The Ameri-canAcademyofOrthopaedicSurgeons(AAOS)beganitsefforts withtheinitiativeknownasWrongSiteSurgeryinthe1980s andpublisheditspreliminaryresultsin1984.1–3In2000,a pub-licationfromtheInstituteofMedicine(IOM)withthetitle“To ErrisHuman:BuildingaSaferHealthSystem”raised aware-nessamongthepublic, the media,politicians and medical professionalsandconsolidatedtheinterestinthistopic.4

InaWorldHealthAssemblythattookplacein2002,the membercountriesoftheWorld HealthOrganization(WHO) recognizedtheneedtoreducetheharmanddistressamong patientsandtheirrelativesarisingfrommedicalerrors,and consequentlyagreed on aresolution forincreasingpatient safety,withinitsworldwidepublicpolicies.InOctober2004, WHO created the World Alliancefor Patient Safety,which, from 2005 onwards, started to define priority topics to be addressedeverytwoyears,knownasGlobalChallenges.5

In 2007–2008, the second global challenge placed the focuson improvementofsafety withinthesurgicalsetting (Safe Surgery), withthe aimof increasing the quality and safety standards for surgical care, through four important actions:(i)preventionofinfectionsatthesurgicalsite;(ii)safe

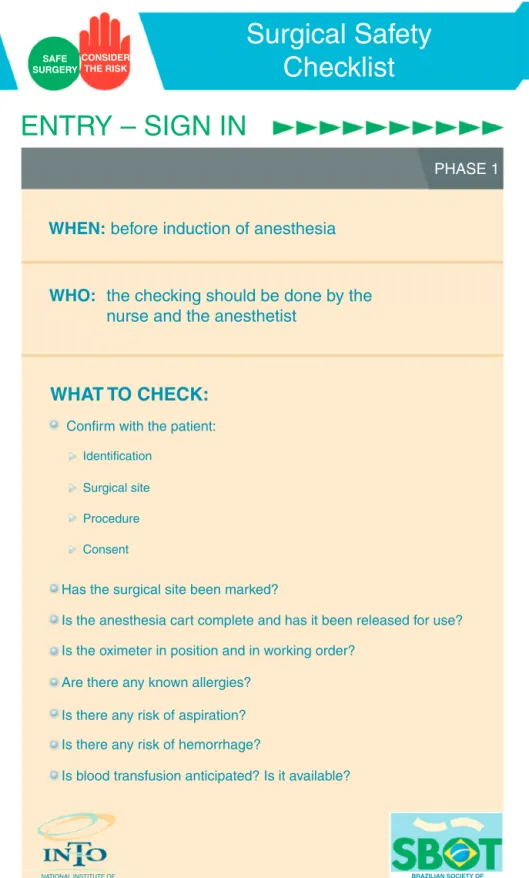

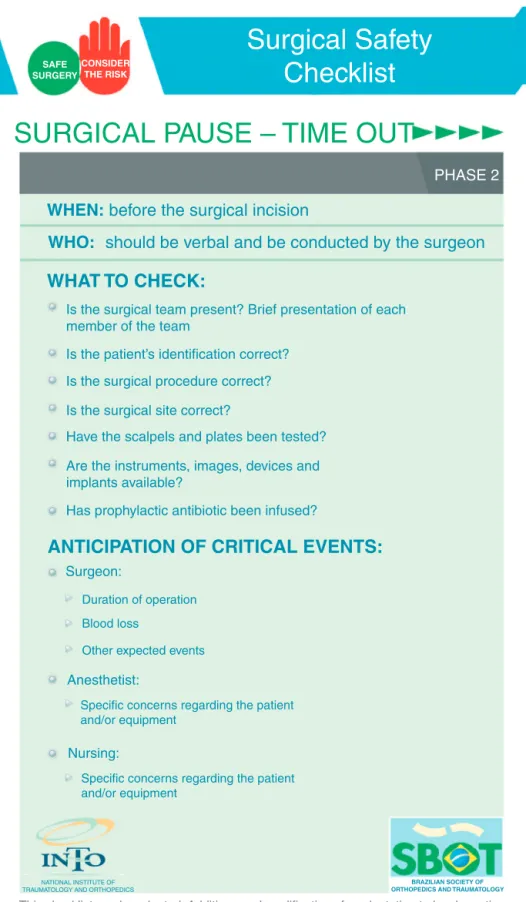

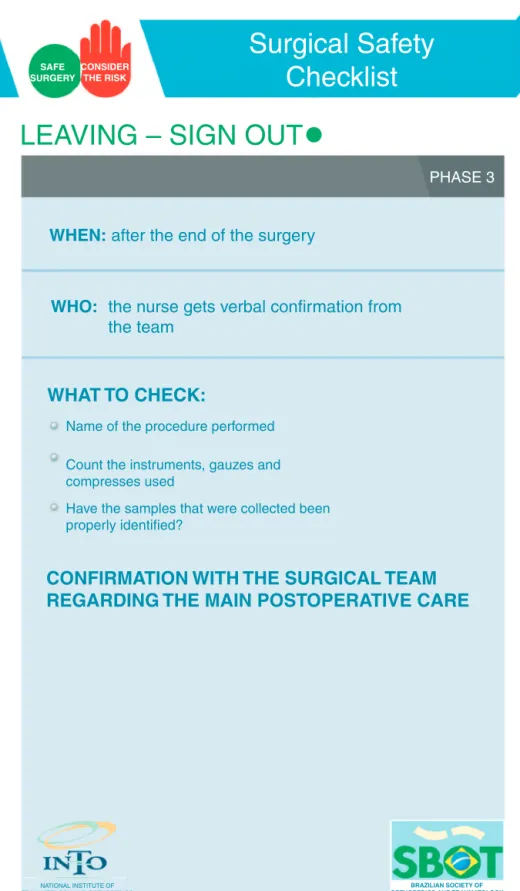

anesthesia; (iii) safe surgical teams; and (iv) surgical care indicators.4Basedontheseactions,acampaignknownasSafe SurgerySavesLiveswaslaunchedinWHOmembercountries. In2008, theBrazilianMinistryofHealthjoinedthe Safe SurgerySavesLivescampaign.Themainaimofthiscampaign wastogethospitalstostartusingstandardizedchecklists pre-paredbyspecialists,soastohelpsurgicalteamsdiminishthe errorsandharmtopatients.Thischecklistwouldhavetobe appliedtoallsurgicalprocedures,inthreephases:beforethe startofanesthesia(SignIn),beforetheskinincision(TimeOut) andbeforethepatientleavesthesurgicaltheater(SignOut)6 (Figs.1–3).

SAFE SURGERY

CONSIDER THE RISK

Surgical Safety

Checklist

ENTRY – SIGN IN

PHASE 1

WHEN:

before induction of anesthesia

Identification

Surgical site

Procedure

Consent

Confirm with the patient:

Has the surgical site been marked?

Is the anesthesia cart complete and has it been released for use?

Is the oximeter in position and in working order?

Are there any known allergies?

Is there any risk of aspiration?

Is there any risk of hemorrhage?

Is blood transfusion anticipated? Is it available?

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TRAUMATOLOGY AND ORTHOPEDICS

BRAZILIAN SOCIETY OF ORTHOPEDICS AND TRAUMATOLOGY

WHAT TO CHECK:

WHO:

the checking should be done by the

nurse and the anesthetist

This checklist can be adapted. Additions and modifications for adaptation to local practice should be encouraged.

SAFE SURGERY

CONSIDER

THE RISK

Checklist

SURGICAL PAUSE – TIME OUT

PHASE 2

WHEN:

before the surgical incision

Duration of operation

Blood loss

Other expected events

Surgeon:

Specific concerns regarding the patient and/or equipment

Anesthetist:

Specific concerns regarding the patient and/or equipment

Nursing:

Is the surgical team present? Brief presentation of each

member of the team

Is the patient’s identification correct?

Is the surgical procedure correct?

Is the surgical site correct?

Have the scalpels and plates been tested?

Are the instruments, images, devices and

implants available?

Has prophylactic antibiotic been infused?

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TRAUMATOLOGY AND ORTHOPEDICS

BRAZILIAN SOCIETY OF ORTHOPEDICS AND TRAUMATOLOGY

WHAT TO CHECK:

ANTICIPATION OF CRITICAL EVENTS:

WHO:

should be verbal and be conducted by the surgeon

This checklist can be adapted. Additions and modifications for adaptation to local practice should be encouraged.

SAFE SURGERY

CONSIDER THE RISK

Surgical Safety

Checklist

LEAVING – SIGN OUT

PHASE 3

WHEN:

after the end of the surgery

Name of the procedure performed

Count the instruments, gauzes and

compresses used

Have the samples that were collected been

properly identified?

WHAT TO CHECK:

CONFIRMATION WITH THE SURGICAL TEAM

REGARDING THE MAIN POSTOPERATIVE CARE

WHO:

the nurse gets verbal confirmation from

the team

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TRAUMATOLOGY AND ORTHOPEDICS

BRAZILIAN SOCIETY OF ORTHOPEDICS AND TRAUMATOLOGY

This checklist can be adapted. Additions and modifications for adaptation to local practice should be encouraged.

whetherthesurgicalteamhascompletedallofthetasksfor thatstage,beforeproceedingtothenextstage.6

Approximately 234 million surgical procedures are per-formedworldwideeveryyear.Aroundsevenmillionpatients presentseriouscomplicationsandonemilliondieduringor soonafterthesurgery.7Increasesinthenumbersofsurgical procedureshavebecomepossiblethroughextraordinary tech-nologicaladvances,whichhavebroughtconsiderablebenefits forpatients.Surgicalresultshaveimprovedsignificantlyand highlycomplexsurgicalprocedureshavebecomeroutine.On theotherhand,technologicaladvanceshavemadethe surgi-calenvironmentlesssafe.8

Overasix-monthperiodatonesurgicalcenterintheUnited States,amortalityraterelatingtomedicalerrorsofonein every270errors(0.4%)wasshown,and65%oftheseerrors wereconsideredtobeavoidable.9Currently,thesurgical envi-ronmentisconsideredtobehighlyunsafe,withanadverse eventratethathasbeenestimatedasoneinevery10,000 sur-gicalprocedures.Incasesoforthopedictrauma,thisraterises toonecomplicationinevery 100procedures.10 Comparison betweenthesurgicalmortalityrateandthecivilaviationrate (whichisless thanone in1,000,000exposures) showsthat healthcareisconsideredtobemoredangerous.10Inaddition tothesefactors,thereisalsothesocialandfinancialcostof theseerrors.

AccordingtodatafromtheLitigationAuthority(LA)ofthe BritishNationalHealthService(NHS),mostcomplaintsof clin-icalnegligencecomefrom surgicalspecialties. Orthopedics hasthehighestrepresentation, accountingfor29.8% ofthe cases(87 out of 292),11 and these data are underreported, giventhatmanypatientschoosenottosuethesurgeonsand hospitals.12

Even the simpler procedures involve dozens of critical stages,withverymanyopportunitiesforfailuresand enor-mous potential for errors resulting in injuries to patients: (i) correct identification of the material used; (ii) efficient sterilizationofthematerialused;(iii)safeadministrationof anesthesia;and(iv)thesurgicalprocedureitself.

Themostcriticalobstacletogoodperformanceinasurgical teamistheteamitself:thesurgeons,anesthetists,nursesand othermembersneedtohaveagoodrelationshipand effec-tivecommunication. Ateamthatworks together touse its knowledgeand skills forthe patient’s benefit may prevent aconsiderableproportionofthecomplicationsthatthreaten life.6

For this,technicalprecisionneeds tobecombined with patientsafety.Inthiscontext,correctuseoftoolsliketheWHO SurgicalSafetyChecklistmayhelpinreachingthistarget.13

Thepresentstudyhadtheaimofanalyzingthedegreeof knowledgeoftheWHOSurgicalSafetyChecklistamong Brazil-ianorthopedists.

Materials

and

methods

Thepresentstudywasofexploratoryandquantitativenature, andwasbasedonapplicationofaquestionnaireonthetopicof

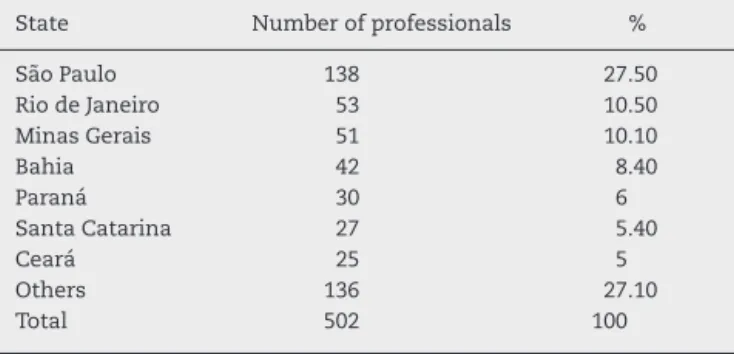

SãoPaulo 138 27.50

RiodeJaneiro 53 10.50

MinasGerais 51 10.10

Bahia 42 8.40

Paraná 30 6

SantaCatarina 27 5.40

Ceará 25 5

Others 136 27.10

Total 502 100

Table2–Professionalswhohaddonemedicalresidency inorthopedicsandtraumatology.

Residencyinorthopedics Numberofprofessionals %

Yes 433 86.20

No 62 12.40

Notstated 7 1.40

Total 502 100

safesurgeryamong3231orthopedistswhowereparticipating atthe44thBrazilianCongress ofOrthopedicsand Trauma-tology(CBOT),whichwasorganizedbytheBrazilianSociety ofOrthopedicsandTraumatology(SBOT)inSalvador(BA),in November2012.

Thequestionnairewasbasedononethatwasdrawnup bytheAmericanAcademyofOrthopaedicSurgeons(AAOS), which inturnused onecreated bythe AmericanAcademy ofOtolaryngology–HeadandNeckSurgery(AAO-HNS),with modificationstoadaptittopracticeswithinorthopedicsand traumatology.14,15

Theformsweredistributedandgatheredinbyateamfrom theSBOT.Thegroupofprofessionalswhogaveresponsesin thesurvey,whowerenotaskedtoidentifythemselves,were notselectedinaccordancewithanyspecificcriterionexcept fortheirwillingnesstoparticipateinthestudy.Thus,thesize ofthesamplewasamatterofchance.Aftertheformshadbeen gatheredin,descriptivestatisticalanalysiswasconductedon theresponses.

Results

Thenumberofprofessionalsparticipatinginthe44thCBOT was3231,whilethenumberofformsreturnedwas502,which represented15.5%ofthetotal.

Mostoftherespondents(317;63.1%)workedwithingeneral orthopedics.Amongthosewhoworkedinsubspecialties,knee surgerypresentedthelargestnumber(105;20.9%),followedby orthopedictrauma(85;16.9%)andshoulderandelbowsurgery (58;11.6%).

Table3–Incidenceoferrorsintheparticipants’clinical practice.

n %

Yes 205 40.80

No 296 59

Notstated 1 0.20

Table4–Knowledgeamongtheprofessionalsrelatingto theSurgicalSafetyChecklist.

n %

Yes 148 29.50

No 328 65.30

Notstated 26 5.20

Amongthese502orthopedists,433(86.2%)saidthatthey hadconcludedmedicalresidencyinorthopedicsand trauma-tology(Table2).

Analysisonthelengthoftimeforwhichtherespondents had been professionallyactive showed that approximately 40%ofthetotalhadbeenactiveformorethan20yearsand thatonly16.7%hadhadlessthanfiveyearsofpractice.

Inevaluatingoccurrencesoferrorsamongthe profession-als,199(39.6%)reportedhavingexperiencedanerrorwithin their practice within the last six months. These incidents experiencedatsurgicalcenters related mostlyto problems withmaterialthatwasincompleteorbecamedamagedafter thestartoftheprocedure,problemswiththeequipmentin thesurgicaltheaterandcommunicationfailures(Table3).

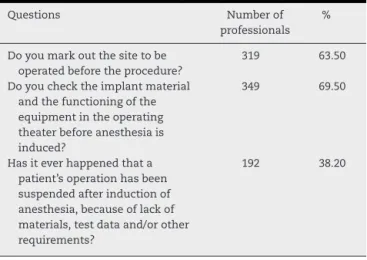

Amongtheorthopedistssurveyed,63.5%preferredtomark outtheoperationsitebeforesendingthepatienttothe surgi-calcenterand69.5%reportedthattheycheckedtheimplant materialandthefunctioningoftheequipmentinthesurgical theaterbeforetheanesthesia(Fig.4).

Although65.3%saidthattheyweretotallyorpartially unfa-miliarwiththeWHOSurgicalSafetyChecklist,37.1%saidthat theyrecognizedthischecklistasasafetybarrierforpatients, physiciansandtheinstitution.Amongtheorthopedists,72.1% reported that they had never had any training forits use (Tables4–6).

Thelastquestionontheformrelatedtotheprofessionals’ involvementincomplaintstotheRegionalMedicalCouncilor tothecourts.Itwasseenthatinvolvementwiththecourts wasmorefrequent,giventhat171respondents(34.1%)said

Table5–Otherquestionsregardingsafesurgery.

Questions Numberof

professionals %

Doyoumarkoutthesitetobe operatedbeforetheprocedure?

319 63.50

Doyouchecktheimplantmaterial andthefunctioningofthe equipmentintheoperating theaterbeforeanesthesiais induced?

349 69.50

Hasiteverhappenedthata patient’soperationhasbeen suspendedafterinductionof anesthesia,becauseoflackof materials,testdataand/orother requirements?

192 38.20

Table6–TrainingforusingtheSurgicalSafetyChecklist.

Howwereyoutrainedtousethe SurgicalSafetyChecklist?

Numberof professionals

%

Nottrained 362 72.10

Trainedbythemedicalteam 46 9.10

Bythequalityadvisorypersonnel 28 5.60

Bythenursingteam 17 3.40

Byadministrationprofessionals 17 3.40

Byriskmanagementpersonnel 12 2.40

Others 20 4.00

thattheyhadansweredthistypeofcomplaint,whereas131 (26.1%)saidthattheyhadansweredcomplaintsattheMedical Council.

Discussion

Studiesinvolvingspecificpopulationspresentlimitations.In thisstudy,weobtaineddataonalimitedpercentage,i.e.15.5% ofthetargetpopulation,andthisresultwasclosetowhatwas obtainedintheactionsundertakenbytheAAO-HNS(18.6%) andtheAAOS(16.6%).15Weusedthestandardsthatthesetwo societieshadused,withtheobjectivesofgivinggreater consis-tencytotheinformationgatheredandenablingcomparisons betweenthefindings.Inaddition,theresultsfromthisstudy maybeusefulasaninitiativeprovidingmotivationforamore detailedstudy.

Lack of annotation on proper form or… Problem with the equipment or instruments… Material for surgical use incomplete or…

Venous access at inappropriate location Problems relating to anesthesia Problems with imaging examinations

Surgery at wrong site Communication failure 13.600% 13.600% 14.100% 17.100% 22.100% 25.600% 53.300% 63.800%

butionoforthopedistsinBrazil.Likewise,specialistswhohad donemedicalresidencyrepresented86.2%ofthetotal num-berofrespondents,whichcorrespondstothenumberofSBOT memberswho generallyattendtheBrazilianCongress.The numberofprofessionalswhostatedthat,atsometimeduring theircareers,theyhadalreadyexperiencedcasesofsurgical proceduresatthewrongsiteoronthewrongpatient repre-sented40.8%ofthetotal.16IntheAAOSsurvey,errorsrelating tosurgeryperformedonthewrongsideaccountedfor59.1% oftheincidents,and56%inthestudybytheJointCommission ontheAccreditationofHealthcareOrganizations(JCAHO).

Recently,astudyevaluatingthedatabaseoftheNational ReportingandLearningService(NRLS),inEngland,was con-ductedinrelationtotheyear2008.Theauthors concluded thatthe WHOSurgical SafetyChecklist contributedtoward aligningtechnicalprecisionwithpatientsafety.6Reportsfrom Americansubspecialtysocietiesalsocorroboratethis under-standing.TheAmericanHandSurgerySocietyreportedthat 21%ofthesurgicalprocedureswereperformedinthewrong locations.17Inrelationtospinalsurgery,thisnumberhasbeen showntobeevenmorealarming,accordingtoastudybythe AmericanAcademyofNeurologicSurgeons,whofoundthat 50%oftheinformantsstatedthattheyhadperformedsurgery atthewronglevelatleastonce.18,19Astudyconductedbythe AmericanAcademyofFootandAnkleSurgeonsalsoshowed thattheincidenceofsurgeryatthewrongsitewas13%.20

Inourstudy,themostfrequenterrorcategoryrelatedto thematerialforuseduringthesurgery,whichwasincomplete orbecame damagedafterthe startoftheprocedure in127 cases(63.8%ofthetotal).Thefollowingwere alsoreported: (i)problemswiththeequipmentinthesurgicaltheater,with 106casesor53.3%ofthetotal;and(ii)communication fail-ures,with51eventsor25.6%ofthetotal.Inthefindingsofthe AAOS,indevelopedcountries, errorsrelatingtoequipment arethecommonestfailure,representing29%ofthetotal, fol-lowedbycommunicationerrors,with24.7%.15Ontheother hand,theerrorcategorythatwasmostfrequentinoursetting (incompleteordamagedsurgicalmaterial)isnotasituation withmuchrepresentationintheUnitedStates.

Amongtheorthopedistsinoursample,63.5%statedthat theymarkedoutthelocationtobeoperatedbeforesending thepatienttothesurgicalcenter.Furthermore,69.5%reported thattheycheckedtheimplantmaterialandthefunctioningof theequipmentintheoperatingtheaterbeforeanesthesiawas induced.

Although 37.1% of the respondents recognized the risk involvedinperformingsurgery andacknowledged thatthe WHOchecklistwasasafetybarrierforpatients, physicians andtheinstitution,65.3%reportedthattheywerecompletely or partiallyunfamiliar with this checklist. Moreover,72.1% mentionedthattheyhadneverbeentrainedtouseit.

Conclusions

Medicalerrorsoccurandrepresentarisktopatients’safety. ThissurveydemonstratedthatdespiteBrazil’sadherenceto

presentingtheWHOSurgicalSafetyChecklistasameansof preventingerrorsduringsurgicaltreatment,thechecklistwas unknownto65.3%ofBrazilianorthopedists.Evensomeofthe orthopedistswhowereawareofithadneverbeentrainedto useit.

Consideringthatthespecialtyoforthopedicsis responsi-bleforalargeproportionofadversesurgicalevents,among which mostareavoidablethrough usingtheWHO Surgical SafetyChecklist,itbecomesnecessarynotonlytorecognize thisasanimportanttoolforimprovingsafetywithinthe sur-gicalenvironment,butalsototrainteamsandstimulateits useamongBrazilianorthopedists.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.AmericanAcademyofOrthopaedicSurgeons.Information statement1015.Wrong-sitesurgery.2003out;2013.Available from:http://www.aaos.org/about/papers/advistmt/1015.asp [accessedon26.03.13].

2.WongD,HerndonJ,CanaleT.AnAOAcriticalissue.Medical errorsinorthopaedics:practicalpointersforprevention.J BoneJointSurgAm.2002;84(11):2097–100.

3.HerndonJH.Onemoreturnofthewrench.JBoneJointSurg Am.2003;85(10):2036–48.

4.KohnLT,CorriganJM,DonaldsonMS,editors.Toerris human:buildingasaferhealthsystem.Washington:National AcademyPress;2000.

5.WorldHealthOrganization.Worldallianceforpatientsafety: forwardprogramme,2008–2009;2013.Availablefrom:

www.who.int/patientsafety/en[accessedon16.04.13]. 6.PanesarSS,NobleDJ,MirzaSB,PatelB,MannB,EmertonM,

etal.Canthesurgicalchecklistreducetheriskofwrongsite surgeryinorthopaedics?Canthechecklisthelp?Supporting evidencefromanalysisofanationalpatientincident reportingsystem.JOrthopSurgRes.2011;6:18.

7.WeiserTG,RegenbogenSE,ThompsonKD,HaynesAB,Lipsitz SR,BerryWR,etal.Anestimationoftheglobalvolumeof surgery,amodellingstrategybasedonavailabledata.Lancet. 2008;372(9633):139–44.

8.PanesarSS,ShaerfDA,MannBS,MalikAK.Patientsafetyin orthopaedics:stateoftheart.JBoneJointSurgBr.

2012;94(12):1595–7.

9.CallandJF,AdamsRB,BenjaminJrDK.Thirty-day

postoperativedeathrateatanacademicmedicalcenter.Ann Surg.2002;235(5):690–6.

10.AmalbertiR,AuroyY,BerwickD,BarachP.Fivesystem barrierstoachievingultrasafehealthcare.AnnInternMed. 2005;142(9):756–64.

11.RobinsonPM,MuirLT.SurgicalerrorsinEnglandandWales: howcommonaretheyandareorthopaedicsurgeonsreally theworst?JBoneJointSurgBr.2011;93Suppl.3:295.

12.Noauthorslisted.NHS:Beingopen:communicatingpatient safetyincidentswithpatients,theirfamiliesandcares;2013. Availablefrom:wwwnfs.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/

?entryid45=65077[accessedon21.03.13].

14.ShahRK,KentalaE,HealyGB,RobersonDW.Classification andconsequencesoferrorsinotolaryngology.Laryngoscope. 2004;114(8):1322–35.

15.WongDA,HerndonJH,CanaleT,BrooksRL,HuntTR,EppsHR, etal.Medicalerrorsinorthopaedics.ResultsofanAAOS membersurvey.JBoneJointSurgAm.2009;91(3): 547–57.

16.TheJointCommission.Universalprotocol;2013.Available from:http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/ UniversalProtocol/[accessedon16.03.13].

17.MeinbergEG,SternPJ.Incidenceofwrong-sitesurgeryamong handsurgeons.JBoneJointSurgAm.2003;85(2):193–7.

18.WongDA.Spinalsurgeryandpatientsafety:asystems approach.JAmAcadOrthopSurg.2006;14(4):226–32.

19.ModyMG,NourbakhshA,StahlDL,GibbsM,AlfawarehM, GargesKJ.Theprevalenceofwronglevelsurgeryamongspine surgeons.Spine(Philadelphia,PA1976).2008;33(2):194–8.