Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte Centro de Biociências

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicobiologia

Comportamento e ecologia acústica da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na região Nordeste do Brasil

Marcos Roberto Rossi-Santos

1 MARCOS ROBERTO ROSSI-SANTOS

Comportamento e ecologia acústica da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na região Nordeste do Brasil

Tese apresentada à Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Psicobiologia.

2 MARCOS ROBERTO ROSSI-SANTOS

Comportamento e ecologia acústica da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na região Nordeste do Brasil

Tese apresentada à Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Psicobiologia.

Orientador: Dr. Flávio José de Lima Silva

Ficha Catalográfica preparada pela Biblioteca Central

4 É com grande respeito que dedico esse trabalho à memória de

5 Baleia... Você conheceu todos Os poderosos oceanos. O segredo dos tempos pretéritos Pode ser ouvido em seu canto.

Ensina-me sua linguagem Para que eu possa compreender As raízes da história Da gênese de nosso mundo.

Sams & Carson, 2000

6 TÍTULO: Comportamento e ecologia acústica da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na região Nordeste do Brasil

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: comportamento de canto, ecologia acústica, baleia jubarte, ruídos antropogênicos, estoque reprodutivo A, nordeste do Brasil

8 ABSTRACT:

9 humpback whale mating system are discussed. In this way, I pretend to contribute with the acoustic ecology subject and provide information to subsidize humpback whale conservation.

10 SUMÁRIO i. Resumo... ii. Abstract... iii. Agradecimentos... 1- Introdução... 1.1) Comunicação animal e ecologia... 1.2) Ruídos e impactos sonoros no ambiente marinho... 1.3) Caracterização da espécie... 1.3.1) Ocorrência e Distribuição... 1.3.2) Ameaças e Status de Conservação da espécie... 1.4) Expansão da população de baleias jubarte no Brasil... 1.5) Ecologia acústica, comportamento e seleção sexual...

2- Objetivos, Hipóteses e Predições... 2.1- Ojetivos...

2.1.1- Objetivo Geral... 2.1.2- Objetivos específicos... 2.2- Hipóteses e predições... 3- Materiais e Método...

3.1- Área de Estudo... 3.2- Coleta de Dados... 3.2.1- Cruzeiros de Pesquisa... 3.2.2- Bioacústica... 3.2.3 - Sistema de Informações Geográficas...

11 4- Resultados...

4.1-Artigo 1... Ecologia comportamental de canto em baleias jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na região Nordeste do Brasil

4.2- Artigo 2... Estrutura acústica e variação temporal do comportamento de canto em baleias jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na área de reprodução da costa do Brasil.

4.3- Artigo 3... Industria do Petróleo e poluição acústica na área de reprodução da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) no Oceano Atlantico sul ocidental.

4.4- Artigo 4... Efeitos dos ruídos produzidos pelo turismo de observação no comportamento da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) na área de reprodução na costa do Brasil

5- Considerações finais... 6- Referências Bibliográficas...

7-Anexo...

36 37

71

102

135

156 160

12

Agradecimentos

Primeiramente, às baleias-jubarte que ainda guardam o mistério de sua

mensagem no mar e refletem no seu olhar introspectivo o espelho do próprio mundo exterior.

Muitas pessoas contribuíram com a construção desse trabalho, de diversas formas. Algumas com intenso apoio, enquanto outras aumentando o desafio em concretizá-lo. Sou grato a todos, pois me deram força para vencer mais essa etapa.

Agradeço o apoio incondicional de minha família – meus pais e irmãos, e especialmente minha mulher amada e companheira Renata e nossa querida filha Moara.

Tenho o prazer de contar como membros da banca, algumas pessoas que muito colaboraram para minha formação profissional. Obrigado Jeff Podos e Emygdio Monteiro Filho pelos muitos ensinamentos, oportunidades e vivências compartilhadas. Obrigado também ao Flávio Lima pela orientação e pelo aprendizado nestes anos recentes.

Agradeço o suporte financeiro dos patrocinadores do Instituto Baleia Jubarte durante os anos deste trabalho: Petrobras Ambiental, Aracruz Celulose, Fundação AVINA e Fundação Garcia D´Ávila. Também à CAPES pela concessão da bolsa de doutorado.

William Rossiter, da Cetacean Society International, vem fornecendo inestimável apoio a muitas viagens internacionais que contribuíram com minha formação, enquanto David Janiger se tornou um grande guardião de artigos científicos fornecendo prontamente desde publicações atuais e outras de antigas datas.

Por fim, agradeço à Mãe Natureza e ao Deus Pai, por nos ensinar a respeitar todos os seres que habitam esse planeta azul.

Todos juntos somos um!

13 1. INTRODUÇÃO

A comunicação animal sempre exerceu um grande fascínio na humanidade. Na história da ciência, a civilização grega avançou muito acerca do conhecimento natural, pois integravam suas descobertas à visão global do Universo ou Cosmo. Suas perguntas sempre se dirigiam à “essência” da questão e nunca ao funcionamento, com forte característica no empirismo, enfatisando o fenômeno, como faria Johan Von Goethe séculos depois, ao invés de valorizar as medições precisas e teorias como na ciência moderna (vide anexo 1).

Assim, a ciência na Grécia impregnava-se do espírito de admiração e de veneração diante dos enigmas do mundo, onde tudo tinha um sentido. Pitágoras, pensador grego característico, acreditava que por trás da realidade material existia um mundo espiritual, cujos seres e forças plasmavam o mundo físico, permeado pelo que ele chamava de “música das esferas”: um fluir de harmonias, uma ordem de relações numéricas e proporções que teriam afinidade com a música. Ainda reencontramos tais relações, por exemplo, entre o comprimento de cordas cuja vibração produz sons considerados harmônicos. Os números não eram apenas designações de quantidade, mas possuiam um conteúdo espiritual próprio (Lanz, 2004).

14 Depois de centenas de anos, esses animais ainda nos maravilham, pelo seu modo de vida, por sua inteligência, por seus mistérios. O canto da baleia jubarte é um dos mais complexos comportamentos acústicos do reino animal (Wilson, 1975), e vem despertando fascínio tanto em admiradores quanto para o meio científico.

Embora provavelmente ouvido por marinheiros durante séculos, as primeiras gravações de canto das jubarte foram feitas por navios da Marinha dos EUA no final dos anos 1950. Os cientistas reconheceram esses sons como vindos de baleias jubarte na década de 1960,ea primeira descrição técnica do canto foi publicado por Payne & McVay (1971).

Desde então, a estrutura geral do canto, bem como as características básicas de machos cantores têm sido descritas (ex.: Tyack, 1981; Payne & Payne, 1985; Darling et al., 2006). Essas características, combinadas com observações de baleias cantando levaram a várias ideias sobre a função ou o papel do canto nas áreas de reprodução, entretanto correlações com a paisagem acústica onde se inserem essas baleias têm sido pouco abordadas. O impacto de sons antropogênicos sobre a comunicação dos cetáceos é um assunto emergente, de crescente interesse (ex: Hatch & Wrigth, 2007).

15 acústico utilizado pela jubarte. Considero aqui como conceito de ecologia acústica o estudo da relação entre os organismos vivos e o seu ambiente sônico (paisagem sonora ou soundscape), em uma adaptação de Truax (1999).

Esse trabalho está organizado em quatro artigos independentes, cada qual com sua estrutura integral (apresentação de tema, métodos, resultados e discussões), mas que se complementam para compor uma visão mais ampliada dos resultados desse tema de estudo.

No Artigo 1 – Ecologia comportamental do canto em baleias jubarte (Megaptera novaeanglie) na região nordeste do Brasil – estudo o comportamento de machos cantores em diferentes estruturas de grupo, sua distribuição espacial e possíveis relações com fatores oceanográficos, como profundidade, regime de marés e fases da lua.

No Artigo 2 – Estrutura acústica e variação temporal do comportamento de canto – descrevo a estrutura física baseado em medições de frequência e tempo dos cantos, fora da área de concentração do Banco de Abrolhos. Também comparo a complexidade do canto registrada no Banco de Abrolhos e Costa Norte adjacente.

No Artigo 3 – Indústria do Petróleo e poluição acústica na área de reprodução da baleia jubarte – caracterizo os ruídos produzidos dentro do contexto da exploração de óleo e gás no ambiente marinho da região de estudo, principalmente advindos de plataformas e embarcações petrolíferas.

16 discutir o impacto desses sons antropogênicos no comportamento das baleias durante a época reprodutiva.

Nas minhas considerações finais, trago um alinhamento entre as discussões apresentadas em cada um dos artigos.

Ainda em caráter introdutório, contextualizando o tema de comunicação animal, trago referências sobre o histórico da pesquisa na área; apresento informações sobre ruídos e impactos sonoros em ambiente marinho e trago a caracterização, a ocorrência e distribuição, as ameaças e status de conservação da espécie e a expansão da população de baleias jubarte no Brasil. Ainda introduzo conceitos sobre ecologia acústica, comportamento e seleção sexual.

Por fim, em anexo, trago uma reflexão sobre uma outra abordagem na concepção científica – a ciência Goetheana – sustentada pelo desenvolvimento da observação fenomenológica no cientista.

1.1) Comunicação animal e ecologia

17 Em contraste, para o estudo dos cetáceos vem se buscando uma perspectiva mais ampla, que inclua feições complementares de comunicação não abordadas nesta visão clássica, sendo uma delas a influência do ambiente no processo de comunicação (ver Tyack, 2000). A maioria dos sinais é modificada assim que passa pelo ambiente, desde o emissor ao receptor, o que implica em degradação inicial deste sinal, mas que resulta em informação ao receptor. Por exemplo, alguns pássaros podem estimar a distância de um indivíduo emissor pela degradação do sinal (McGregor & Krebs, 1984; Naguib, 1998).

18 1.2) Ruídos e impactos sonoros no ambiente marinho

O ambiente acústico marinho por si já é uma fonte de ruído e poluição sonora que reflete na percepção e resposta comportamental para diversos animais (McCauley et al., 2000a, 2000b; Miller et al., 2000). O ambiente acústico marinho que as baleias encontram hoje é diferente do que estavam habituadas há cerca de 50 anos atrás, principalmente em área de reprodução, onde, como animais migratórios, passam cerca de seis meses por ano.

Um grande crescimento da zona costeira mundial, resultando em grande frota de embarcações e da indústria do petróleo resultou em um ambiente onde os níveis de poluição acústica podem chegar a molestar os indivíduos, causando danos temporários ou até mesmo permanentes em sua fisiologia e comportamento (ex: Richardson et al., 1995, Johnson et al., 2007).

19 1.3) Caracterização da espécie

A baleia jubarte, Megaptera novaeangliae (Cetacea, Balaenopteridae), é uma espécie cosmopolita e distribui-se por todos os oceanos (Clapham & Mead, 1999).

É considerada um rorqual devido a presença de sulcos ventrais, estruturas que se expandem durante a alimentação que se tornam de coloração avermelhada. As principais características externas da jubarte são: número de pregas ventrais, tamanho e forma da nadadeira peitoral, equivalente a aproximadamente um terço do comprimento total do animal (figura 1), coloração e formato da nadadeira caudal (Chittleborough, 1965). A jubarte também é chamada de baleia corcunda devido à tendência de arquear o corpo quando mergulha.

20 Figura 1: A baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae), com detalhe para as pregas ventrais e grandes nadadeiras peitorais, realizando comportamento de salto, no litoral norte do estado da Bahia.

Jubartes machos e fêmeas atingem a maturidade sexual com aproximadamente 2 a 5 anos de idade e a maturidade física 10 anos depois (Chittleborough, 1965; Clapham, 1992). A única diferença anatômica externamente visível entre machos e fêmeas é a presença de um lobo hemisférico na região urogenital das fêmeas localizada logo após a porção posterior da abertura genital (True,1904).

21 filhotes começam a desmamar, tornando-se inteiramente independentes ao final do primeiro ano de vida (Clapham & Mayo, 1987).

Nas áreas de alimentação e reprodução, as jubartes apresentam organização social caracterizada por grupos instáveis e pequenos (2 a 3 animais). Grandes grupos podem, entretanto, se formar temporariamente durante comportamento alimentar, ou relacionados com a disputa agressiva entre machos durante a temporada reprodutiva (Clapham & Mead, 1999).

Os machos da espécie produzem um conjunto de sons complexos, denominados “canto”, durante a temporada reprodutiva, provavelmente com a função de atrair as fêmeas e/ou afastar outros machos (Tyack, 2000). O canto tem uma estrutura previsível, com uma série de sons (unidades), repetida ao longo do tempo nos padrões (frases), com cada frase repetida várias vezes para compor um "tema" (Payne & McVay, 1971).

Um canto típico é então composto por 5-7 temas que geralmente são repetidos em uma ordem seqüencial, durando tipicamente 8-15 minutos (embora possa variar de 5-30 minutos) e depois repete-se sobre e ao longo de uma sessão, que pode durar várias horas (Payne & McVay, 1971).

22 de vários anos, o canto é praticamente irreconhecível a partir da versão original (Payne et al., 1983). Em alguns casos, observa-se que a música é completamente outra no espaço de apenas dois anos (Noad et al., 2000).

1.3.1) Ocorrência e Distribuição

As jubartes são animais migratórios, deslocando-se anualmente das áreas de alimentação em altas latitudes, onde permanecem durante o outono e verão, para as áreas de reprodução nos trópicos e sub-trópicos, onde permanecem durante o inverno e primavera (Clapham & Mead, 1999). As áreas de reprodução da espécie são tipicamente entre ilhas e/ou associadas a sistemas coralíneos(Whitehead, 1981; Whitehead & Moore, 1982) (figura 2).

Uma população no Mar da Arábia é a única que aparentemente não migra em busca de alta produtividade das águas frias para se alimentar, sendo observada durante todo o ano em águas tropicais (Mikhalev, 1997).

23 Figura 2: Ocorrência mundial e padrão migratório da baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae).

24 Figura 3: A baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) ocupando a região metropolitana de Salvador, Estado da Bahia (Banco de Imagens- IBJ).

1.3.2) Ameaças e Status de Conservação da espécie

25 A baleia jubarte está presente em todas as listas oficiais de espécies ameaçadas, entre as quais a Lista Oficial de Espécies da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçadas de Extinção (Portaria IBAMA 1522 de 10/12/89) e no Apêndice I da Convenção sobre o Comércio Internacional de Espécies Ameaçadas da Fauna Selvagens (CITES). Segundo a IUCN (Reeves et al., 2003) e o Plano de Ação para Mamíferos Aquáticos do Brasil (IBAMA, 2001), a espécie está classificada como espécie vulnerável à extinção.

Atualmente as baleias estão protegidas da caça comercial, mas sofrem ameaças por diversas atividades desenvolvidas pelo homem como o emalhamento em redes de pesca, a poluição dos oceanos, atropelamento e colisões com embarcações e atividades relacionadas à exploração de petróleo.

1.4) Expansão da população de baleias jubarte no Brasil

26 Atualmente, a população de baleias jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) do “BSA” vem crescendo naturalmente, aliado ao resultado da paralização, na década de 1960, da caça comercial da espécie. Recentes estudos sobre modelagens numéricas (Zerbini et al, 2006, Ward et al., 2006) e avistagens ao longo da costa brasileira (Andriolo et al., 2006a,b; Rossi-Santos et al., 2008; Wedekin et al, 2010) contribuem com essa afirmação, demonstrando que a população vem reocupando áreas que historicamente já utilizaram, como, por exemplo, a Baía de Todos os Santos, onde eram abundantes no passado (Tavares, 1916; Tollenare, 1961).

1.5) Ecologia acústica, Comportamento e Seleção Sexual

27 Além disso, dentro da abordagem ecológica, abrem-se outras questões como, por exemplo, a comparação entre a concentração reprodutiva com outras áreas ao longo da costa e o contexto social-ecológico onde os machos cantam (quais os grupos sociais onde ocorrem com mais frequência, quais as características ambientais destes locais e suas prováveis relações com o comportamento de canto da espécie), que serão abordadas no presente trabalho.

2. OBJETIVOS, HIPÓTESES E PREDIÇÕES

2.1) Objetivos

2.1.1) Objetivo Geral

Caracterizar a ecologia acústica do comportamento conhecido como “canto”, da baleia jubarte, M. novaeangliae, na região nordeste do Brasil, fora de sua concentração reprodutiva no Banco de Abrolhos, entre os anos de 2005 a 2009.

2.1.2) Objetivos específicos

28 b. Descrever a estrutura físico-acústica do canto da baleias jubarte fora de

sua área de concentração reprodutiva (artigo 2);

c. Descrever e analisar as fontes de ruídos antropogênicos provenientes da indústria do petróleo no ambiente acústico utilizado pela baleia jubarte (artigo 3)

d. Descrever e analisar as fontes de ruídos antropogênicos provenientes do turismo de observação de baleias no ambiente acústico utilizado pela baleia jubarte (artigo 4)

2.2) Hipóteses

Hipótese 1: Existe uma relação entre a complexidade da estrutura de grupo no qual o macho cantor está inserido e o contexto ecológico no qual este comportamento ocorre, sendo que fora da área de concentração reprodutiva a estrutura do canto das baleias jubarte tende a se diferenciar.

Predição 1: os grupos com machos cantores apresentam estrutura social diferenciada quando inserido em um cenário ecológico distinto da concentração reprodutiva.

Hipótese 2: Existe uma relação entre a complexidade do canto e a caracterização oceanográfica no qual este comportamento ocorre, sendo que fora da área de concentração reprodutiva a estrutura do canto das baleias jubarte tende a se diferenciar.

29 Hipótese 3: Existe a sobreposição de nicho acústico, onde ruídos provocados por atividades humanas causam interferências no comportamento das baleias jubarte.

Predição 1: Os ruídos provocados por atividades humanas no ambiente marinho estão dentro da faixa de frequência utilizada pela baleia jubarte no seu processo de comunicação.

3. MATERIAL E MÉTODOS

3.1) Área de estudo

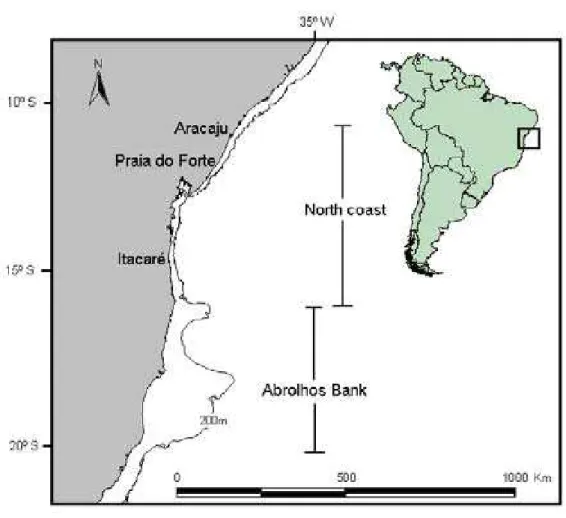

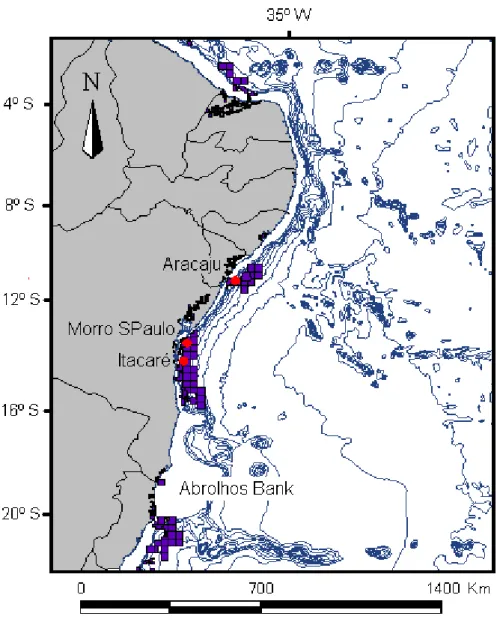

A área do presente estudo inclui o litoral do Estado da Bahia, desde Itacaré (14° S, 38° W) a Aracajú (11° S, 37° W), no litoral do Estado de Sergipe (figura 4), por ser uma região adjacente ao norte da concentração reprodutiva da espécie com facilidades logísticas nos portos de Itacaré (cerca de 300 km ao sul de Salvador), da própria capital, Salvador, de Praia do Forte, no município de Mata de São João, a 55 km ao norte.

30 crescendo em altura na direção norte e por praias de baixo declive e de maior extensão ao sul.

Dentro da área de estudo também ocorrem grandes baías e estuários costeiros, de importância para a navegação, como a Baía de Todos os Santos, no Estado da Bahia e os estuários do Rio Vaza-Barris e do Rio Sergipe, no estado de mesmo nome.

A principal característica desta região, em geral, é a presença de uma plataforma continental estreita, cuja extensão corresponde a aproximadamente 15 km (figura 4). A média de profundidade ao longo da plataforma é de 20-70 metros e a amplitude de maré varia entre 0.1 a 2.6m (Carta náutica – Diretoria de Hidrologia e Navegação DHN- da Marinha do Brasil.).

32 3.2) Coleta de dados

3.2.1) Cruzeiros de pesquisa

Para os cruzeiros de pesquisa utilizou-se uma embarcação de madeira, do tipo saveiro (caracterizada por possuir somente um mastro central) de 15 metros e motor díesel de 250 hp (figura 5).

33 A equipe de campo, composta por três observadores, permanece na proa da embarcação para cobrir um ângulo de 180° de campo visual. As observações são feitas a olho nu, eventualmente auxiliadas por binóculos, buscando-se identificar sinais de baleias (borrifo, dorsos, saltos e outros comportamentos) na superfície da água próxima ao horizonte.

Utilizamos uma ficha diária de amostragem, com os dados gerais da expedição, como duração, participantes, número de baleias avistadas, bem como os dados ambientais (velocidade e direção do vento, visibilidade, escala Beaufort do mar, profundidade, entre outros) que poderiam influenciar nas condições de avistabilidade. Para as tomadas de horário da maré correlacionada aos grupos de baleias avistados, foi utilizada a Tábua de Marés fornecida pela Diretoria de Hidrologia e Navegação (DHN) da Marinha do Brasil.

Os grupos de baleias-jubarte avistados foram registrados em outra ficha de campo, onde constam informações como coordenadas geográficas, tamanho e composição do grupo, horário da avistagem, comportamentos observados antes e durante a aproximação do barco, além de outras informações.

34 4.2.5) Bioacústica

Ao longo dos anos o equipamento de gravação variou em função do crescente avanço tecnológico que derivou nos sistemas de aquisição de áudio e vídeo digital. Entre os anos 2005 a 2007, os cantos de baleia foram gravados utilizando um sistema analógico (gravador cassete Sony TCD-5M – resposta de frequência de 24 kHz) ou, eventualmente um sistema analógico-digital (vídeo-camêra Sony VX-1000) sempre plugados ao mesmo hidrofone (HTI SSQ-94). A partir de 2008 passou-se a utilizar um sistema digital (mini-gravador digital M-Audio MicroTrack II), resultando em um ganho da resposta de frequência para 48 kHz.

Posteriormente, as gravações obtidas nos sistemas analógico e analógico-digital foram analógico-digitalizadas, exportanto os dados brutos para o programa onde seriam feitas as análises, o RAVEN 1.3 (Universidade Cornell/EUA). Os dados do sistema digital já eram obtidos em formato sem compressão (WAV), selecionado no gravador, e salvos em um banco de dados de áudio.

35 Para os cantos das baleias jubarte, também analisamos a complexidade de partes da estrutura dos cantos, agrupadas em unidades sonoras ou notas, frases e temas, seguindo a classificação de trabalhos anteriores (revisado em Tyack, 2000, Souza-Lima, 2007 e Parsons, 2008)

4.2.6) Sistema de Informações Geográficas

37 Artigo 1 – Ecologia comportamental do canto em baleias jubarte (Megaptera

novaeangliae), na região nordeste do Brasil.

Marcos R. Rossi-Santos 1,2, Elitieri Santos-Neto1, Clarêncio G. Baracho-Neto1, Sérgio R. Cipolotti1, Enrico G. Marcovaldi1, Flávio J. L. Silva2,3

Instituto Baleia Jubarte

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Universidade Estadual do Rio Grande do Norte\ Centro Golfinho Rotador

BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY (A1 – Fator Impacto 3,083)

38 RESUMO

40 BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY OF THE SONG IN HUMPBACK WHALES

(MEGAPTERA NOVAEANGLIAE), FROM THE SOUTHWESTERN ATLANTIC OCEAN

ABSTRACT

We studied the behavioral ecology involving singer humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) from Itacaré/ Bahia state (14°S, 38°W) to Aracaju/ Sergipe state (11°S, 37°W), in the Brazilian breeding ground, between 2005 and 2009 (July to October). Behavioral and ecological aspects such as group composition, spatial distribution, depth, tides and moon were analyzed, through boat surveys. We sighted 370 whale groups in 123 days, during a total of 912 hours of sampling effort. In 36 days, 29% of the groups (n=44; 82 individuals) were identified containing at least one singer male. Such groups were sighted along all the study area, mostly like alone individuals (n=21 groups, 48%), followed by groups with two (n=8; 18%), three (n=3, 7%), four (n=2, 4,5%) individuals and also groups with female-calf pairs with one escort male (n=4, 9%) or female-calf pairs plus two males (n=1, 2%). Groups with singer males were sighted in a depth range of 16 and 173 meters (mean = 54,6 ± 34,2 SD). The narrow continental shelf associated with the coastal distribution of the whales in the study area may influence in the group compositions containing singer males. So on, this work bring for the first time an ecological perspective of this recognized important singing behavior in this species, and also show the expansion of the acoustic activity, during the Brazilian breeding season, going far beyond the core area of Abrolhos Bank.

41 1) INTRODUCTION

1.1) Ecology and animal communication

The most of the acoustic signals are modified when the pass by the environment since the sender to the receiver, which transforms and depredates this signal, but even so, results in information to the receiver, as some bird species who can estimate the distance from a sender individual through the signal degradation (McGregor & Krebs, 1984; Naguib, 1998).

Furthermore, the environment may shape evolutionary changes which may result in specific vocal adaptations in close related vertebrate species, and even inside the same species, leading to differences in sound repertoire which reflect their ecological habits (Podos, 2001; Podos et al., 2004).

Dolphins and bats track their environment listening to the echoes which themselves produces, a process called echolocation (eg: Tyack, 2000). Thus, in the field of cetacean communication there are some basic questions that still could be answered, such as what are the features that make this signal unique. Those questions are crucial to understand whether these signals are elaborated and have their specific usage. Part of this subject is included in the behavioral ecology context of the present work.

42 1.2) Species Characterization

The humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae (Cetacea, Balaenopteridae), is a cosmopolitan species distributed along all the oceans worldwide (Clapham & Mead, 1999), moving every year from high latitude feeding areas, staying during the autumn and summer, to the breeding areas in the tropics, staying during the spring and summer (Clapham & Mead, 1999). These breeding areas are typically between islands and/or associated with coral systems (Whitehead, 1981; Whitehead & Moore, 1982).

In the feeding and breeding area, the humpback whale present a social organization characterized by unstable and small groups (2 to 3 animals). However, larger groups can be found during the feeding behavior or related to the aggressive competition between males during the breeding season (Clapham, 1996).

1.2.1) Ocurrence and Distribution

Nowadays, there are seven humpback whale sub-populations (or stocks) in the southern hemisphere (IWC, 1998), one of those, named by IWC “Breeding Stock A/ BSA” to migrate to the Brazilian coast, where they breed from July to November.

43

1.3) Ecology and Acoustic Behavior

The humpback whale is also known as singer whale because its unique characteristic of to exhibit a singing behavior, performed only by males, during their breeding season. Since the 1970ths, many studies described the physic structure of the songs (eg. Payne e Mc Vay, 1971; Helweg et al., 1998; Maeda et al., 2000; Arraut & Vielliard, 2004) and even their probable functions at the population ecology level, such as female attraction, male-male competition and cultural exchange (eg. McSweeney et al., 1989; Dawbin & Eyre, 1991; Darling & Sousa-Lima, 2005; Eriksen et al., 2005), however many other aspects of the acoustic ecology of the species during the singing behavior is still unknown, such as the socio-ecological context in which the males sing, bringing spatial information (eg. where do they sing?, what depth?) and variations of this context inside the breeding season.

2) MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1) Study area

44 This region is characterized by two remarkable environments, being the presence of large bays and estuaries from Itacaré to Salvador, capital of Bahia state, and by long sand beaches, with large dune formation fringing the coast line, between Praia do Forte and Aracaju (Hatge & Andrade, 2009).

Figure 1 – Study area, named North coast, located between Itacaré and Aracaju, Northeastern Brazil. For reference, southwards it is located the Abrolhos Bank, core area of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) distribution in Brazil. The line represents the 200 meters isobath, demarking the Brazilian continental shelf.

45 We carried out boat based surveys searching for whales in a determined route, approaching animals when sighted to collect data such as number of individuals, composition of the groups, behavior observed before and after approach, dive patterns, time of beginning and end of the sightings and bioacoustic recordings.

Behavioral observations followed a combined Focal Group and Ad libitum methods (see Mann et al., 2000) registering a sequence of a certain behavior during the observation time of each group, broadly employed in the cetacean studies. Behavior and group structure nomenclature and definitions followed extensive previous works worldwide (Clapham, 1996, Clapham & Mead, 1999, Clapham 2000) and locally (Engel, 1996, Lunardi et al., 2010).

2.3) Sex Determination of Individuals

Genetic studies of humpback whales worldwide have shown that singing and escorting are behavioral roles performed only by males and that a whale closely associated with a calf is its mother, an adult female (eg. Palsboll et al, 1997; Darling & Berube, 2001).

An ‘escort’ is defined as a whale that is associating with another adult whale known to be female or with a mother-calf pair. When two males are engaged in dispute behavior in the presence of a female, both are considered escorts (Herman & Tavolga 1980).

46 2.4) Geographic Information System (GIS)

For the record of the geographic position of sighted animals, with reference to the boat position, we utilized a GPS Map 76 and a GPS Map 60c (Garmin), in the way-point function. For posterior analysis and studies of the humpback whale distribution along the time in the study area, we created a GIS environment modeling, including important features such as the Brazilian coast line, bathymetry and the plotted geographic coordinates of each sighting, in a digital nautical charter, using the software Arc View GIS (version 3.1).

2.5) Dive Time

Dive time were systematically registered during 2008 and 2009 breeding seasons, utilizing a digital chronometer, in order to measure and compare breathing behavior of small groups (less than 4 individuals), to date, Alone Males (solitary), Couples, Female with calf pairs, Female with Calf plus one escort male.

47 2.6) Tide and moon analysis

We divided tidal states into 8 different classes, looking for a similar time division and fine scale during the tidal regimen. Significant differences in tide and moon phases categories were analyzed utilizing the Chi-Square test (5%).

3) RESULTS

48 Table 1: Number of boat surveys, sampling effort (hours), covered distance (nautical miles), number of sighted whales, number of groups and direct observation (hours) of humpback whales in the northeastern Brazilian coast, between 2005 and 2009.

Seasons Survey n Sampling effort (hs)

Direct

observation (hs)

Covered distance (Nm)

Whales observed

Groups

2005 17 118,5 34,7 699 104 53

2006 37 266,6 109,4 1667 317 151

2007 7 51,7 18,8 339 58 26

2008 32 235,7 96,5 1463 291 21

2009 30 240 77 981 275 119

Total 123 912,3 336,4 5179 1045 370

3.1) Distribution

49 Figure 2: Distribution of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) groups with singer males, in the study area, Brazilian breeding ground, between 2005 and 2009

3.2) Group structure

50 Figure 3: Frequency of different group structure of humpback whales with singer males, between 2005 and 2009, in the Northeastern Brazilian coast. 1 Ad = 1 adult individual, 2 Ad = 2 adult individuals, 3 Ad = 3 adult individuals, 4 Ad = 4 adult individuals, FefiEp = female and calf pair plus one escort male, FefiEpE = female and calf pair plus two escort males.

51 3.3) Behavioral observations

Alone individuals (n= 21) are generally observed floating on the surface, with slow movements and performing resting behavioral events related to diving, such as tail-up and dorsum arching, with minor frequency of snaking (tail and peduncle shaking before dive) and breaching, both noted only for 3 individuals. Couples exhibited more active behaviors than alone animals, being observed breaching (3 individuals), tail slapping (2 individuals), diving and resting (2 individuals).

Competitive groups including singer males were registered on four occasions, exhibiting active behaviors. In Oct, 1, 2005, during 40 minutes of direct observation we sighted 4 animals performing behaviors of consecutive tail-up for short dives, dorsum arching, belly exposition, breaching and bubble exhalation on the sea surface.

In Jul, 31, 2008, we sighted 3 animals during 41 minutes of direct observation showing head slapping, dorsum arching, rolling, breaching (n=13), tail-up for diving (n=12) and tail slapping (n=2). In this sighting, we observed one whale-watching zodiac boat (about 9m long with outboard engine of 250 Hp) near to the humpback group.

52 3.4) Dive time

We obtained 956 measurements for 52 humpback whale observed groups (Table 2). The time at the sea surface, indicated a general pattern of few (2-5) very short breathings (less than 30 seconds) and one longer dive (> 30 to 780 seconds).

Four groups of alone males were singing while measured, confirmed by underwater recordings. In Aug, 10, 2008, the singer male was at 51 meters deep, showing long dive patterns and performed fluke exhibition in travelling behavior. Another sighting, in Aug, 30, 2008, we observed a sequence of long dives (7 measurements > 200 seconds) of the male at 40 m deep. Again, we observed 5 fluke exhibitions in displacement behavior. In Aug, 28, we observed a singer male in active behavior with breaching and singing while showed a dive pattern of 4 dives less than 60 sec and then one long (>100sec). Depth was not registered. In the last observation, during the research cruise of Jul, 14, 2009, a singer male was in rest behavior at 36 meters deep, and the song caption was intense, suggesting the proximity to our boat. This animal presented long dives, being the maximum value registered for the total sample of 780 seconds (13 minutes), and performed the same fluke exhibition than the other observed males.

53 Table 2 – Summary of humpback whale dive time from the study area in the Brazilian coast between 2008 and 2009 *.

Group Structure # Groups Depth range (m) (D.O.) (min) (D.P) range (sec) Mean range D.P > 100sec # of measur . # measur. > 100sec Alone Males

21 8,7-126 977 2-780 134,3-780 278 59

Couples 18 49-126 810 2-660 125,6-540 389 88 FeCa

pairs

3 - 120 5-132 116-166,3 59 7

FeCa-E1 10 66-155 500 2-349 122,3-479,5 230 31

Total 52 8,7-155 2407 2-780 956 185

* Definitions: (D.O.- minutes) = Direct Observation (the time spent observing humpback whale groups); (D.P. range – seconds) = Dive Pattern – the time whales spent underwater; (Mean range D.P > 100 sec) = mean number of Dive Patterns larger than 100 seconds; (# of measur.) = number of dive measurements; (# measure. > 100sec) = number of dive measurements larger than 100 seconds; (Fe-Ca pairs) = female and calf pairs; (Fe(Fe-Ca-E1) = female and calf pairs plus one escort male.

3.5) Environmental features

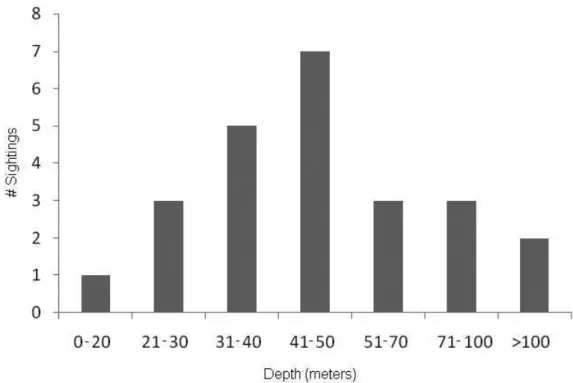

3.5.1) Depth

54 whale groups, for depth range 3 (31 to 40m) we observed 5 groups, for depth range 4 (41 to 50m) we sighted 7 whale groups, while for depth range 5 (51 to 70m) we registered 3 groups. For depth range 6 (71 to 100m) we observed 3 whale groups and for depth range 7 (> 100m) we sighted 2 groups, being one with a alone individual at 126m and a competitive group of 4 animals at 173 meters deep.

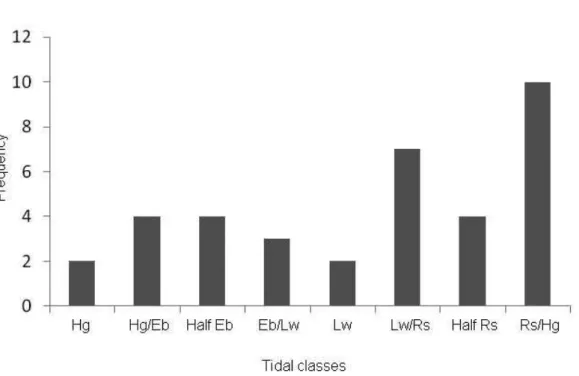

55 3.5.2) Tide

Even dividing the tidal states into time similar categories, and apparently diverse in the frequency distribution (Figure 5), the Chi-Square test showed no statistical differences between singer male occurrence in the tidal classes (Chi-Square 5% =11,55556; df = 7; p= 0,12).

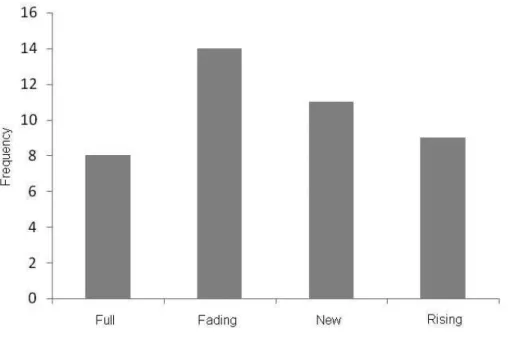

56 3.5.3) Moon Phases

Singer males were sighted in all moon phases, but despite small differences (figure 6) there was no statistical differences between the four classes (Chi-Square 5% = 2,0; df = 3 p= 0,57), indicating no evident influences of this environmental feature in the singing behavior along the study area.

57 4) DISCUSSION

During five years we found humpback whale groups containing singer males in all the extension of our study area, being about 520 km of coast. This confirm the large distribution of the humpbacks in the Northeastern region of Brazil, going farther than the core area of Abrolhos Bank, as previously commented(Rossi-Santos et al., 2008; Wedekin et al., 2010).

The lack of sightings in the stretch of coast between north of Praia do Forte to south of Aracaju may be probably due to the sampling route, always passing there during the night, because navigating conditions in those cruises, which depart from Praia do Forte to reach Aracaju during the early morning of the next day. However, the sightings north and southwards of this place attest the presence of the humpbacks, and because its high mobility we assume they do occur along all that part of coast.

Despite the singer animals being typically described as alone males (eg. Payne & Mc Vay, 1971; Clapham, 1996; Darling & Berube, 2001), singing behavior may occur in other group composition, as the occasional escort males (eg. Baker and Herman, 1984; Frankel et al., 1995; Darling & Berube, 2001), whose may sing while escorting females with or without calves. Darling & Berube (2001) also reported about 14 occasions where another male approached singer males.

58 flexibility from humpback whales in increase the chances to find a mate partner during the breeding season.

During many occasions we noted singer males typically smaller (referenced to the boat as 8-9m long animals), suggesting that young animals are using the study area as a way to search for new territories even less competitive than the core area of Abrolhos Bank, where traditionally large and old singer males utilize during the breeding season. We suggest the employ of the photogrammetry method (eg. Spitz et al., 2002) to access this hypothesis in next studies concerning body size estimation.

Humpback whale distribution in the study area may be related to ecological features such as oceanographic parameters of depth, continental shelf extension, while tide and moon seems do not influence singer male distribution.

Meanwhile, behavioral factors such as female distribution are theorized in the literature and may be determinant in the singer male occurrence during the breeding season. As humpback whale apparently do not feed in the breeding areas, females tend to move intensely, avoiding to meet with other female while, simultaneously, looking for increase their mate chances. Pos-partum ovulation, common in this species, also benefits this high mobile female behavior and these factors together result in an irregular female distribution (Clapham, 1996; Clapham & Mead, 1999).

The fact of the study area be located in a continental region, different from the most of the described breeding areas, such as the Hawaiian Archipelago, (Au, et al., 2006), South Pacific Ocean islands (Helweg et al., 1998), Panama Gulf (Olviedo et al., 2008), may result on differences in their acoustic signals.

59 provide the development of different acoustic signals that may be more efficient in a certain environment.

Further studies should develop efforts in ecological comparisons between coastal and oceanic areas which may be affecting male distribution and singing behavior in a fine scale.

We registered an increase in behavioral activity according to the increase in the group size and composition, with larger groups presenting a broader behavioral repertoire, in accordance with literature descriptions to other breeding areas (eg. Clapham, 1996) and to the same breeding stock A, in the Abrolhos Bank (Morete et al., 2007), which may contribute with the complex group structure during the breeding season and may reflex in complexity of communicative skills (Freeberg et al., 2012).

The largest dive, of 13 minutes, was found for a singer male, very similar to the results from a recent study in the Abrolhos Bank, which analyzed the same 4 group categories and registered the largest time of 13,13 minutes, coming from a singer male (Benzamat et al., 2010), indicating a probable general pattern for areas as distant as 500 km, in the same breeding stock.

Humpback whales sometimes show avoidance to boat approaching increasing their dive patterns (Hoyt, 2001). During many years researchers from both Abrolhos Bank and North Coast of Bahia state, noted that the whales in North Coast are more difficult to approach than in the core area of Abrolhos. The present data on the mean percentage of time spend by diving whales was 85% in relation to the direct observation time. This value was more than double than previous studies from the Abrolhos Bank, 42 % in Peres (2006) and 30,1% in Benzamat et al. (2010).

60 movements of whales (Wedekin et al., 2010; Baracho-Neto et al., 2012), and this could lead, in consequence, in more travelling behavior and even boat avoidance through less time in the surface.

The narrow continental shelf in the North Coast also can play a role in the dive patterns, making individuals travel more in a north-south direction to keep in shallow waters characteristic of their distribution, while in the Abrolhos Bank, the core area in the Brazilian coast, more than double of density of whales (Andriolo et al., 2006a; 2006b; Wedekin et al., 2010).

As the whole breathing behavior of humpbacks do include those very short intervals, we decided to keep them all in the analyzes, different from Benzamat et al. (2010) which only included intervals larger than 60 seconds, even considering that smaller intervals prevailed, being 68% of their sampling.

61 4.1) Mating System

Polygyny is a mating system in which one male mates with several females during a breeding season. “Lek” is defined as a traditional display site where males gather to defend small territories that lack resources useful to females, which nevertheless visit the site to mate. Therefore, lek polygyny occurs when a polygynous male use displays to attract several females to them at small display sites (Alcock, 1993).

It is well studied for other mammals such those closely related to cetaceans, the ungulates, beyond 35 bird species, frogs and even insects (see Krebs & Davies, 1993, Alcock, 1993). Clapham (1996) suggested the term ‘floating lek’ to the humpback whale mating system, emphasizing the high mobility of the singer males, in contrast with the traditional lek which present a fixed territoriality.

In the present study, we present some spatial (presence of multiple group composition) and behavioral (diverse repertoire while singing) features found that support the “lek polygyny” as the mating system for the humpback whale. The singer male distribution along the study area indicate that a broad area in the breeding ground is being utilized for displaying, refusing lek influenced by “hotspot”, in which males compete for the most attractive site to display, while fitting better to lek by “hotshot” males, which may choose any place to sing and then attract females to mate and more “satellite” males, coming to maximize their mate chances by staying as close as the hotshot male (Krebs & Davies, 1993; Alcock, 1993).

62 (Clapham, 1996). However, instead to emphasize only the male-male dominance and territoriality, Connor et al. (2000) also include a broader view in which lekking behavior is found in association with other male mating strategies, as the example of male-male combat in competitive alternatively to displaying. Tyack (2000) suggest that humpback whale song plays a role in both male-male competitions and female choice, showing attributes associated with both intra and intersexual selection.

To determine a precise mating system for the humpbacks is a complex task, once we still do not know many basic issues as the ideal breeding area size for any population. Thinking broader, the Brazilian population increase (Ward et al., 2006; Zerbini et al., 2006, Andriolo et al., 2006b) could lead to dispersion of young females, whose would attract different males, then forming the floating lek, either by hotspot or hotshot, and colonizing favorable adjacent areas.

At the same time that in the core area, the Abrolhos Bank, male arenas would be much more competitive, then causing younger males to move northwards and search for new areas to aggregate, through singing, and then maximize mate.

Furthermore, reflecting on the multi faced hypothesis of a mating system, would be important to analyze that the humpback whale population using the

Brazilian breeding ground have a sex-ratio of 1.2:1, similar to the expected rate of

1:1, determined genetically by Cypriano-Souza et al. (2010). Baracho-Neto et al.

(2012) also support the site fidelity similarity between genders through a long term

photoidentification study in Praia o Forte, same than the present study.

All these pieces together may help to create a scenario suggesting a mating

system more complex than previously reported, with more fluidity of individuals,

63 possibly influenced by some environmental features as the extent of the continental

shelf, consequently depth gradient.

Furthermore, the diversity in singer male occurrence and behavior between different group compositions could be related to the complex communicative system in humpback whales, as recently described by Freeberg et al. (2012). Future studies should include environmental and whale occurrence data in a broader temporal scale to test specifically each one of these factors and their influence in the acoustic ecology and behavior of humpback whales.

5) REFERENCES

Alcock, J. 1993. Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusets.

Andriolo, A.; Martins, C. C. A.; Engel, M. H.; Pizzorno, J. L. A.; Más-Rosa, S.; Freitas, A.; Morete, M. E. & Kinas, P. G. 2006a. The first aerial survey to estimate abundance of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the breeding ground off Brazil. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 8(3), 307–311.

Andriolo, A., Kinas, P.G., Engel, M.E. & Martins, C.C.A. 2006b. Monitoring humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) population in the Brazilian breeding ground, 2002 to 2005. IWC Scientific Committee, 12 pp.

64 Au, W. W. L., Pack, A., Lammers, M. L.; Herman, L.M.; Deakos, M.H. & Andrews, K. 2006. Acoustic properties of the humpback whale song. Journal Acoustic Society of America, 120 (2),1103-1110.

Baker, C., S., & Herman, L. M. 1984. Aggressive behavior between humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) wintering in Hawaiian waters. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 62, 1922-1937.

Baracho-Neto, C. G.; Santos Neto, E.; Rossi-Santos, M. R.; Wedekin, L. L.;

Neves, M. C.; Lima, F & Faria, D. 2012. Site fidelity and residence times of

humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) on the Brazilian coast. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, p1 of 9, doi:10.1017/S0025315411002074.

Bezamat, C.; Wedekin, L. L.; Marcondes, M. C. C; Valentin, J. L. 2010. Padrão de mergulho da baleia jubarte na concentração reprodutiva do Banco de Abrolhos, Brasil. III Congresso Brasileiro de Oceanografia – CBO’2010

Rio Grande, Brazil, 2308-2310.

Bradbury, J. W., & Vehrencamp, S. L. 1998. Principals of animal communication. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

Clapham, P.J. 1996. The social and reproductive biology of Humpback Whales: an ecological perspective. Mammal Review, 26, 27-49.

65 Clapham, P. J. 2000. The humpback whale: Seasonal feeding and breeding in a baleen whale.

Connor, R. C., Read, A. J. & Wrangham, R. Reproductive strategies and social bonds. In: Cetacean societies - Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales (Ed Mann, J., Connor, R. C., Tyack, P. L. & Whitehead, H), pp 247–269. ChicagoIL: Press.Male.

Cypriano-Souza, A. L., Gabriela, P., Fernandez, C. A., Lima-Rosa, V. Engel, M. H., Bonatto, S. L. 2010. Microstellite genetic characterization of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) breeding ground off Brazil (Breeding Stock A). Journal of Heredity, 101 (2), 189-200.

Darling, J. D. & Berube, M. 2001. Interactions of singing humpback whales with other males. Marine Mammal Science, 17, 570-584.

Darling J.D. & Souza-Lima R.S. 2005. Songs indicate interaction between

humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) populations in the western and eastern South Atlantic Ocean. Marine Mammal Science, 21, 557–566.

Dawbin, W. H. & Eyre, E. J. 1991. Humpback whale songs along the coast of Western Australia and some comparison with east coast songs. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 30 (2), 249-254.

DHN-Departamento de Hidrologia e Navegação da Marinha do Brasil. 1995. Tábua de Marés.

66 Engel, M. 1996. Comportamento reprodutivo da Baleia Jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) em Abrolhos. Anais de Etologia, 14, 275-284.

Eriksen, N., Millar, L. A., Tougaard, J., & Helweg, D. A. 2005. Cultural change in the songs of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) from Tonga. Behaviour, 142, 305-328.

Frankel, A,.S., Clark, C. W., Herman, L. M., Gabriele,C. M. 1995. Spatial distribution, habitat utilization, and social interactions of humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, off Hawaii, determined using acoustic and visual techniques. Canadian Journal of Zoology.73, 1134-1146.

Freeberg, T. M., Ord, T.J. & Dunbar, R. I. M. 2012. The social network and

communicative complexity: preface to theme issue. Philosophy Transactions Royal. Society, 367, 1782-1784.

Hatge, V & Andrade, J.B. (2009) Baía de Todos os Santos: Aspectos Oceanográficos. Editora da Universidade Federal da Bahia, 264p.

Helweg, D. A., Cato, D. H., Jenkins, D .F., Garrigue, C. & McCauley, R. D. 1998. Geographic variation in South Pacific humpback whale songs. Behaviour 135, 1-17.

Herman, L. M. & Tavolga, W. N. 1980. The communication systems of cetaceans. In: Cetacean Behavior: Mechanisms and Functions (Ed. by L. M. Herman), pp. 149– 209. New York: J. Wiley.

67 IWC. 1998. Report of the Scientific Committee. Reports of the International Whaling

Commission, 48, 55–302.

Krebs, J. R. &. Davies, N. B. 1993. An introduction to behavioral ecology. 3a ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

Lodi, L. 1994. Ocorrências de baleias-jubarte, Megaptera novaeangliae, no Arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha, incluindo um resumo de registros de capturas no Nordeste do Brasil. Biotemas, 7(1), 116-123.

Lunardi, D. G., Engel, M. H., Marciano, J. P. & Macedo, R. H. 2010. Behavioural strategies in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in a coastal region of Brazil. Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 90 (8), 1693-1699.

Maeda, H., Higashi, N., Uchida, S., Sato, F., Yamaguchi, M., Koido, T. & Takemura, A. 2000. Songs of humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, in the Ryukyu and Bonin regions. Mammal Study, 25, 59-73.

Mann, J., Connor, R. C., Tyack, P. L. & Whitehead, H. 2000. Cetacean Societies: Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales. Chicago, IL: Chicago Press.

McGregor, P. K. & Krebs, J. R. 1984. Song Learning and deceptive mimicry. Animal Behaviour 32, 280-287.

McSweeney, D. J., Chu, K. C., Dolphin, W. F. & Guinee, L. N. 1989. North Pacific humpback whale songs: A comparison of southeast Alaskan feeding ground songs with Hawaiian wintering ground songs. Marine Mammal Science, 5, 139–148.

68 region, Bahia, Brazil. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 87, 87–92

Naguib, M. 1998. Perpection of degradation in acoustic signals and its implications for ranging. Behavior. Ecology. Sociobiology. 42, 139-142.

Olviedo, L., Guzman, H. M., Floréz-Ganzalés, L., Capella Alzueta, J. & Mair, J. M. 2008. The song of the southeast Pacific humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) off Las Perlas Archipelago, Panama: preliminary characterization. Aquatic Mammals, 34 (4), 458-463.

Payne, S. & McVay, S. 1971. Songs of humpback whales. Science, 173, 585–597.

Peres, G. B. 2006. Caracterização do tempo de mergulho em baleia jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae) no Arquipélago de Abrolhos, Bahia – Brasil. Trabalho de Conclusão do Curso de Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

Podos, J. 2001. Correlated evolution of morphology and vocal signal structure in Darwin’s finches. Nature, 409, 185-188.

Podos, J. E., Southall, J. A., Rossi- Santos, M. R. 2004. Vocal mechanics in Darwin´s finches: correlations of beak gape and song frequency. Journal of Experimental Biology, 207, 607 – 619.

69 Rossi-Santos M.R., Neto E.S., Baracho C.G., Cipolotti S.R., Marcovaldi, E. & Engel, M. H. 2008. Occurrence and distribution of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) on the north coast of the State of Bahia, Brazil, 2000–2006. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 65, 667–673.

Spitz, S.S., Herman, L. M.; Pack, A. A. & Deakos, M. H. 2002. The relation of body size of male humpback whales to their social roles on the Hawaiian winter grounds. Canadian. Journal of Zoology, 80, 1938 – 1947.

Tavares, J. S. 1916. A pesca da Baleia no Brasil. Brotéria, Revista de Sciencias Naturaes: Série de Vulgarização Scientífica, 14, 69-80.

Tollenare, L.F. 1961. A pesca da baleia (pelo Recôncavo Baiano – 1817) (org Bruno, E.S. & Riedel), pp. 63-79Histórias e Paisagens do Brasil – Coqueirais e Chapadões – Bahia e Sergipe. Editora Cultrix, São Paulo.

Towsend, C. D. 1935. The distribution of certain whales as shown by logbooks of American Whaleships. Zoologica, 19 (1), 2-50.

Tyack, P. 2000. Functional aspects of cetacean communication. In: Cetacean Societies: Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales (Ed Mann, J., Connor, R. C., Tyack, P. L. & Whitehead, H), pp 270-307. Chicago, IL: Chicago Press.

70 Whitehead, H. 1981. The behaviour and ecology of the Northwest Atlantic humpback whales. Ph.D. thesis. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, 256 pp.

71 Artigo 2 – Estrutura acústica e variação temporal do comportamento de canto em baleias jubarte (Megaptera novaeangliae), na área de reprodução da costa

do Brasil.

Marcos R. Rossi-Santos 1,2, Leonardo L. Wedekin1, Elitieri Santos-Neto1, Clarêncio G. Baracho-Neto1, Sérgio R. Cipolotti1, Enrico G. Marcovaldi1, Flávio J. L. Silva2,3

Instituto Baleia Jubarte

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Universidade Estadual do Rio Grande do Norte

ANIMAL BEHAVIOR (A1 – Fator Impacto 2,926)

72 RESUMO

73 de freqüência, relacionados com características ecológicas evidentes, como a profundidade e a plataforma continental e o coro como uma parte da arena de reprodução necessária para engatilhar alguns dos comportamentos da baleia jubarte durante seu período de reprodução no Brasil.

74 Acoustic structure and temporal variation in the song of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) from the Brazilian Breeding Ground

ABSTRACT

75 behavior. We discuss about the high diversity on song form and broad frequency range related to ecological remarkable features such as depth and continental shelf, and the chorus as a part of the breeding arena necessary to trigger some of the humpback behavior during their breeding season in Brazil.

76 1) INTRODUCTION

Humpback whale song was described as the most elaborated and spectacular single display of any animal species (Wilson, 1975). The song was initially described in detail by Payne & McVay (1971) and Winn et al (1971). Extensive analyses of this unique vocal behavior have revealed that: (1) males produce stereotyped, ordered sequences of sounds for long periods, (2) at any given time, sequences produced by individuals within a breeding area are highly similar (Winn et al., 1981; Payne & Guinee, 1983), and (3) whales continuously modify these sequences over time (Payne et al., 1983; Payne & Payne, 1985). Explanations for the structural and acoustic features of humpback whale songs remain speculative. Because most researchers assume that songs are used primarily for long distance communication (Payne & McVay, 1971; Winn & Winn, 1978; Tyack, 1981; Helweg et al., 1992; Frankel et al., 1995; Cerchio et al., 2001; Darling & Bérubé, 2001), song features often are interpreted in terms of how they might facilitate the transfer of information among whales (Winn & Winn, 1978; Frankel, 1995). Additionally, song properties could reflect strategies for collecting environmental information, if components of songs are used as echolocation signals (Winn & Perkins, 1976; Winn & Winn, 1978; Frazer & Mercado, 2000; Au et al., 2001).

77 Humpback whale songs show clear structure based on aural analysis, with smaller repetitive units called “phrases” organized into larger “themes” which tend to occur in specific sequence (Payne and McVay, 1971, Guinee et al., 1983) (figure 1). The structure of song changes over the course of a winter season, yet at any given time all singers appear to be singing the same version of a song (Guinee et al., 1983, Payne et al., 1983, Payne and Payne, 1985).

The relationship between singing and seasonal gonadal activity suggests that song production plays a role in the mating system. While humpback whale song appears to be the result of strong sexual selection (Tyack, 1981, Smith, 2008), its function in the mating system remains unclear. Helweg et al. (1992) presented a detailed summary of current hypotheses regarding the role of humpback whale song, but its role is still far from certain. A number of possible functions of song have been proposed, including sexual advertisement to females (Payne and McVay, 1971; Winn and Winn, 1978; Tyack 1981, 2000), maintenance of spacing and territorial defense among singing males (Winn and Winn, 1978; Tyack, 1981; Frankel et al. 1995), inducement or synchronization of ovulation in females (Baker and Herman 1984), and a navigational “beacon” for migrating whales (Winn and Winn 1978).

Songs of humpback whales are typically recorded close to a whale in order to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio. However, when sounds are recorded at large distances from any whale, a number of whales singing may sound as in a chorus, although they do not sing in unison on the same portion of a song (Au et al., 2000).

78 Mac Vay, 1971; Winn et al., 1971), and thereafter it goes up to 15-24 kHz (Helweg et al., 1992; Au et al., 2000, 2001, 2006; Fristrup et al., 2003). Mercado et al. (2003) measured acoustic patterns in humpback whale songs recorded in Hawaiian waters during four consecutive years (1992–1995) to determine whether subcomponents of songs differ in their detectability after long-range propagation. Such analyses can provide important insights into the functions of humpback whale songs.

Singing whales most often are reported to be alone (Winn & Winn, 1978; Tyack, 1981) although there are exceptions (Baker & Herman, 1984). It is generally accepted that singing is done by males where calves are being born and seasonal gonadal activity is high (Chittleborough, 1955; Payne & McVay, 1971).

80 Figure 1: Representation of the types of structural components typically present in sequences of sounds produced by singing humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Each letter represents one sound. Each individual sound is called a unit (different letters correspond to aurally distinctive sound units). Repeated groups of units are called phrases (black lines). A theme is a set of phrases (gray line). Songs consist of repeated theme sequences within a song session (1 to 4 complete the cycle, thereafter song session starts again).

2) MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1) Study Area and Population Stock

81 Figure 2 – Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) study area off Northeastern Brazil (Breeding Stock A), divided in two regions: a southern region, the Abrolhos Bank and a northern region, named North coast, located between Itacaré (BA) and Aracaju (SE). The line represents the 200 meters isobath, demarking the Brazilian continental shelf.

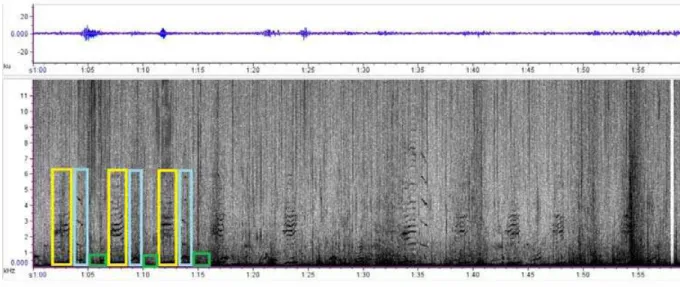

82 Analyzes were first made both by listening and by visually comparing spectrograms, which are sound graphics with x-axis on time (seconds) and y-axis on frequency (Hertz). Spectrographic analyzes were performed using software RAVEN 3.1, selecting the following frequency parameters (Hertz), relative sound intensity (dB re SNR - referenced to the Signal to Noise Ratio) and time (seconds): minimum, maximum, central frequency, frequency amplitude, energy and duration. Whenever found, the harmonics and their intervals were also measured, as well as the visual contour shape from each note.

3) RESULTS

During 6 years we obtained a record effort of more than 50 hours. From these raw data, we selected “type” songs from each sampled year, for both areas of Abrolhos Bank and the North Coast, chosen by containing all the characteristic phrases of the song from that year, as well by presents the best signal to noise ratio. In some years, like 2007, more than one song was selected, produced at different time during the breeding season, due to its high quality to extract additional acoustic information.

3.1) Acoustic parameters

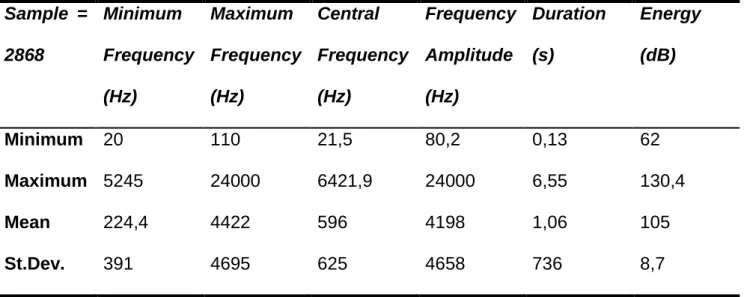

83 1). However some features are remarkable, such as the mean central frequency at low frequency (596 Hz) (figure 3) and the intense sound energy putted into sound transmission (mean= 105 dB).

Harmonics were registered in 2098, 73 % of the measured notes, varying in number of 1 to 85 (mean = 10,4). Harmonic intervals ranged from 10,3 to 4309 Hz (mean = 405).

Table 1: Acoustic parameters from the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) song (sample = 2868 notes), in the study area, Northeastern Brazilian coast.

Sample = 2868 Minimum Frequency (Hz) Maximum Frequency (Hz) Central Frequency (Hz) Frequency Amplitude (Hz) Duration (s) Energy (dB)

Minimum 20 110 21,5 80,2 0,13 62

Maximum 5245 24000 6421,9 24000 6,55 130,4

Mean 224,4 4422 596 4198 1,06 105

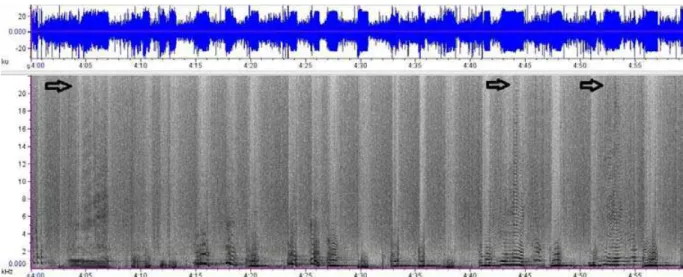

84 Figure 3: Combination of spectrograms, a sound graphic with x-axis on time (seconds) and y-axis on frequency (kiloHertz), exemplifying some of the different humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) notes with its remarkable mean central frequency around 500 Hz (indicated by black circles) Blue line graphs above represent the respective oscilograms or waveforms, sound graphics with x-axis on time (seconds) and y-axis on pressure (ku).

3.2) The humpback whale song form

85 Table 2: Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) song characteristics from the northeastern Brazil (Abrolhos Bank), between 2005 and 2008, showing recording information –file identification and day-, file duration (minutes:seconds), total number of notes, different note types, number of themes and number of singers registered in each recording file.

SONG# DAY DURATION

(m:s) TOTAL NOTES NOTE TYPES N THEMES N SINGERS

ABL 2005 26jul05 12:20 160 14 8 >3

ABL 2006a

11:20 200 16 10 2

ABL 2006b

24:12 290 21 8 2

ABL2007-1

10Jul07 20:00 151 39 12 1

ABL2007-2

16:25 220 40 15 3