FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO

PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS

Mariana Carvalho Barbosa

The Impact of Mayor Leadership on Education:

Evidence from Brazil

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV

Barbosa, Mariana Carvalho

The impact of mayor leadership on education: evidence fom Brazil / Mariana Carvalho Barbosa. – 2015.

49 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas, Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa.

Orientador: Cesar Zucco Júnior. Inclui bibliografia.

1. Políticas públicas. 2. Mulheres na política. 3. Educação e Estado. 4. Prefeitas. 5. Formulação de políticas. I. Zucco Júnior, Cesar. II. Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas. Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa. III. Título.

Mariana Carvalho Barbosa

The Impact of Mayor Leadership on Education:

Evidence from Brazil

Dissertação submetida a Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Administração.

Área de Concentração: Políticas Públi-cas, Economia Política

Orientador: Cesar Zucco Jr.

Mariana Carvalho Barbosa

The Impact of Mayor Leadership on Education:

Evidence from Brazil

Dissertação submetida a Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Administração.

Aprovada em 29 de Junho de 2015 pela comissão organizadora:

Cesar Zucco Jr.

EBAPE/FGV

Rudi Rocha de Castro

IE-UFRJ

Francisco Junqueira Moreira da Costa

Acknowledgements

To my adviser Cesar Zucco Jr., for all his teachings and thoughtful guidance.

To Octavio Amorim Neto, for mentoring me since I was an undergrad student, and for always encouraging me to pursue a career in political science.

To every staff member in EBAPE, specially Celene e Adriana, for all the help during the last year.

To the members of the jury, for accepting the invitation and for their valuable com-ments.

To all my "EBAPIANS" colleagues, with whom I’ve shared fun moments.

Last but certainly not least, to my mother Marina and my brother Cassiano, to whom I dedicate all my achievements.

Abstract

What are the impacts of female mayors on education? It is well known that in

Brazil, like in many other countries around the globe, women are underrepresented

in political posts. Understanding the impacts of this discrepancy on policy choice

and redistribution across many areas of inquiry is, therefore, an important research

endeavor. Extant literature shows a strong link between women and the economic

development of the areas they govern, specifically that they provide public goods

relevant to the needs of women constituents. However, despite the efforts to explore

the impacts of gender political leaders, we still do not know what is the consequence

of gender on policy outcomes. Exploring a rich dataset on Brazilian municipalities, I

intend to enrich the literature on the role of female politicians on politics. I employ a

regression discontinuity design using Brazilian elections and indicators on education

based on the basic education development index (IDEB), education expenditures

and local policies. I find that municipalities where a woman enters into power do

not perform better on education and do not present more investments or policies to

improve education.

Contents

1 Introduction 6

2 Literature Review 9

2.1 Theoretical Background . . . 9 2.2 Preferences and Gender Representation . . . 11 2.3 Impacts of women in politics on policy . . . 13

3 Institutional Background 16

4 Empirical Strategy 19

4.1 Data . . . 19 4.2 Identification Strategy . . . 21

5 Results 25

5.1 Education outcomes . . . 25 5.2 Education outputs . . . 29 5.3 Results on rural areas . . . 34

6 Discussion 36

7 Conclusion 38

A Appendix 47

List of Figures

1 Timeline of Events . . . 20

2 The Impact of Gender on Education Outcomes . . . 26

3 The Impact of Gender on Education Policies . . . 31

4 Balance Test - Municipal Characteristics . . . 47

5 Balance Test - Municipal Characteristics . . . 48

6 McCrary Test . . . 49

List of Tables

1 Descriptive Statistics: Difference in Means . . . 232 Effect of electing a female mayor on education outcomes 3, 5 and 7 years after elections . . . 28

3 Effect of female mayor on municipal education expenditures and agreements 30 4 Effect of female mayor on local management . . . 33

5 Effects of female mayor on rural areas - Education outcomes . . . 35

The Impact of Mayor Leadership on Education:

Evidence from Brazil

Author: Mariana Carvalho Barbosa

∗Advisor: Cesar Zucco Jr.

†June 30, 2015

Abstract

What are the impacts of female mayors on education? It is well known that in

Brazil, like in many other countries around the globe, women are underrepresented

in political posts. Understanding the impacts of this discrepancy on policy choice

and redistribution across many areas of inquiry is, therefore, an important research

endeavor. Extant literature shows a strong link between women and the economic

development of the areas they govern, specifically that they provide public goods

relevant to the needs of women constituents. However, despite the efforts to explore

the impacts of gender political leaders, we still do not know what is the consequence

of gender on policy outcomes. Exploring a rich dataset on Brazilian municipalities, I

intend to enrich the literature on the role of female politicians on politics. I employ a

regression discontinuity design using Brazilian elections and indicators on education

based on the basic education development index (IDEB), education expenditures

and local policies. I find that municipalities where a woman enters into power do

not perform better on education and do not present more investments or policies to

improve education.

∗Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas da Fundação Getulio Vargas (EBAPE-FGV)

1 Introduction

Amartya Sen, in a prominent article in theNew York Review of Books (Sen, 1990), stated that more than 100 million women were missing. If girls and women received medical care, food and social services at the same rate that boys and men received, the proportion of women would be higher in the world. Men exceed women in many aspects of economic and social life due to gender gap. And this pattern is extended also to politics, where the percentage of women in all Lower and Upper Houses worldwide is 22.1% (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2015). In executive positions, this rate is even lower, with female leaders in 28 out of 193 countries (Christensen, 2015). As presented by Duflo (2012), the relationship between women’s empowerment and development is bidirectional. In any case, enhancing the participation of women within democracies is seen as central to improving governance (World Bank, 2001). In this study, I address the impact of the gender of politicians in executive positions on public policy.

There is already a plethora of evidences showing that women and men have differ-ent preferences and priorities. Women are more altruistic (Eckel and Grossman, 2008), risk-averse (Croson and Gneezy, 2009) inequality-averse (Selten and Ockenfels, 1998) and concerned about family and children issues, like health, nutrition and education (Thomas, 1991; Thomas and Welch, 1991). Consequently, gender differences are perceived in lead-ership (Moran, 1992), accounting (Barua et al., 2010), financial decision-making (Powell and Ansic, 1997) and household decisions (Thomas, 1990). Thus, it’s only natural to expect women and men to also differ in politics and public policy. And, indeed, there is plenty of empirical evidence illustrating this difference (Chattopadhyay and Duflo, 2004; Brollo and Troiano, 2012; Pande and Ford, 2011; Clots-Figueras, 2012; Schwindt-Bayer, 2006).

defended by descriptive and substantive representations and citizen-candidate models (Besley and Coate, 1997; Osborne and Slivinski, 1996), individual preferences influence policy.

Political scientists aiming to explain political representation created two concepts: the extent to which a politician resembles the citizens represented (descriptive represen-tation) and how the politicians behavior, accordingly to the interests of a specific group (substantive representation). Increasing the first would increase the latter. In the same line of thought, citizen-candidates models designed by economists predict that if politi-cians have strong divergent opinions about a specific issue, their preferences will influence policy choices. As described by Besley and Coate (1997), due to high entry costs, the citizen decides to join politics if his/her preferences are distant enough from the status quo. In other words, if an individual characteristic is associated to political preferences, the politician’s personal attributes weight for political decisions.

In this context, education is considered a woman’s domain issue (Schwindt-Bayer, 2006). Data from Brazilian municipalities show that women are occupying public po-sitions that have direct impacts on education. Brazil has 5565 municipalities, where in 2743 women are occupying positions of education manager (Secretário da Educação)1

, who have deliberative power over education policies. In addition, approximately 70% of the presidents of municipal education councils are women (Coutinho and Fundação Joaquim Nabuco, 2012). Besides, there is a high female domination in health and edu-cation studies (World Bank, 2012). Due to a bias against girls in math and other exact sciences in primary education, an underrepresentation of women in engineering and sci-ences in higher education levels is created and they end up studying social scisci-ences in general. Thus, the evidence illustrates that women should care more about education.

Under these circumstances, I conduct an analysis on the impact of Brazilian female mayors leadership on education outcomes as well as on outputs, that is, how female political leaders allocate public funds differentially than male counterparts in similar municipalities and what policies they can implement to improve education. In Brazil, the

1

mayors have extensive powers on municipalities’ budgets and a good deal of oversight of public spending.

Using the set-up of a quasi-experimental approach that close elections provide, I com-pare municipalities where female candidates barely won the elections against a male can-didate with municipalities where they barely lost against male cancan-didates. To control for municipality-specific confounding factors, I use Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD). I focus on education outcomes, such as the Basic Education Development Index (IDEB),

and education outputs or policies, over which the mayor have discretionary power, like

municipal expenditures and municipal practices to improve local education (i.e. creating municipal education plan, councils or funds, as well as training and hiring teachers for municipal schools). In sum, I expect that the gender of local policy-makers would also have impact on education through the role of mayors in defining local policies and des-ignating the secretário municipal da educação. I aim to explore this question empirically in the context of Brazilian cities.

My results do not corroborate the theoretical expectations: In general, I do not find any differences of female mayorship on education outcomes or outputs. As motivated above, according to the classic median voter theorem, this finding is expected, given that gender or any characteristics of the representative should not impact on policy (Downs, 1957), candidates should converge to the median voter irrespectively of their own preference.

I find effects on policies for hiring new teachers for municipal schools and policies fo-cused on giving training to teachers in rural areas. The first effect is that in municipalities where the mayors are women the probability of having hiring policies decreases in 8% on average. On the other hand, in rural areas, the presence of a woman in local executive government increases the municipality’s probability of having teacher’s training in 15%. Given that they are isolated effects and significant at the 0.1 and 0.05 level, respectively, these results might simply be a product of false positive tests.

pref-erences and consequences of female presence in politics. Section 3 describes the Brazilian institutional background over which the analysis is carried. Section 4 describes the data sources and presents the empirical strategy. On Section 5, I outline the results. On section 6, I develop a discussion about the results. And section 7 concludes with some remarks on future agendas of research.

2 Literature Review

2.1

Theoretical Background

Political representation has been discussed by a sprawling literature in political science, sociology and economics. One of the most famous and straightforward definitions of political representation was offered by Pitkin (1967): to represent is simply to "make present again". This means to make citizens’ preferences and opinions "present" in the political arena. In this seminal work, Pitkin (1967) identifies four views of representation, of which two have been extensively discussed in the subsequent literature,descriptive and

substantiverepresentations. Descriptive representation is basically the extent to which the

representative is similar to those represented. For example, the main questions addressed by descriptive representation are "do black representatives represent black voters?" or "do women representatives govern in favor of women?". This concept does not denote only visible characteristics, but also shared experiences, like representatives who worked on farming can represent the interests of farmers.

(1981), in turn, states that descriptive representation is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee the represented’s policies.

The discussion goes beyond political science, and is also presented in the economics literature. Models described by Osborne and Slivinski (1996) and Besley and Coate (1997) predict that increasing political representation enhances citizen’s influence on pol-icy choices. In their models, the citizens are potential candidates and they choose to enter or not in politics, based on an entry cost. "Citizen-candidate models" predict that the politician’s identity may influence the public policies implemented by him/her due to the fact that the entry cost to politics is high and the citizens only choose to enter politics — becoming politicians — when their preferences are strong in comparison with the status quo and they can implement their priorities. The main difference between the models is the way voters cast their votes, sincerely or strategically. In my case, if women and men have different opinions or concerns related to education, the gender of the candidate should have impact on decision-making.

On the other hand, the median voter theory predicts that the identity of the candidate does not influence policy choice (Downs, 1957). The simple Downsian model predicts that gender or any characteristics of the representative should not impact policy formation: he or she opts for the interests of the median voter. In a world with perfect information, with majority vote and complete candidates credibility, parties and politicians only care about winning elections and the public policy that increases the probability of victory is the median voter’s one (the option that the majority of voters prefers).

fun-damental because gender can be seen as analogous as other cases of minorities (Htun,

2004) and the economic status of this disadvantaged groups should be improved.

2.2

Preferences and Gender Representation

Why women would govern differently from men? Experimental studies show that women and men differ in social preferences (Croson and Gneezy, 2009). In this context,

Croson and Gneezy (2009) explain that salary differences are due to the fact that women

prefer jobs which are less competitive, less risky and more focused on their well-being.

Eckel and Grossman (2008) consider studies that use three different standard economic

games - dictator, ultimatum and public goods — to compare women and men when

faced with economic decisions, finding that women tend to be more altruistic than men.

These differences are perceived also in preferences related to inequality and redistribution.

Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001), using dictator games, and Selten and Ockenfels (1998),

using solidarity games, find that women are more inequality averse than man. Alesina

and Giuliano (2011), for instance, show that women are more pro-redistribution than

men, even after controlling for political ideology.

What are women’s interests? The existing literature states that women care more about health and children education. Swers (2001) claims that female legislators

are more liberal in their policy attitudes and exhibit a greater commitment to the pursuit

of feminist initiatives of traditional concern to women, including education, health and

welfare. Thomas (1994) pursues the same line of thought, declaring that men do not share

the same priority list with women do, which includes issues pertaining to women, children

and family. Women’s issues, children and family are also female priorities according to

Thomas (1991) and Thomas and Welch (1991), who study differences in preferences

between men and women in the U.S. Congress. Lastly, Mansbridge (1999) corroborates

this hypothesis stating that sharing the same experiences, allow women to be better

prepared to represent the female interests.

In this sense, Thomas (1990) strengthens this theory using the Brazilian surveyEstudo

income and finds that income under the control of the mother has an effect between four

and seven times higher on her children consumption than the income in the hands of the

father. If we accept that women have different preferences than men, how do these get

represented by the government? Under the median voter theorem, it would suffice to

extend suffrage of women, as candidates, irrespectively of gender, would converge to the

median voter. Studying the relationship between the women’s suffrage in United States

and the access to the bacteriological revolution happening at the time, Miller (2008)

finds that the introduction of women in politics through the right to vote increased

the expenditures on public health. Additionally, Lott Jr and Kenny (1999) examine

indicators of size and scope of government and concludes that giving women the right to

vote increased the state government expenditures and revenues.

However, if differences between male and female leaders exist, then it is important

not only to enfranchise women but also to make sure they are elected. Moreover, without

female leaders it is impossible to know whether or not female leaders make a difference.

The evidence presented builds the argument that if women in power are "better for children" and we like to make children more fruitful, it is necessary to increase female representation.

But how to increase their representation? The direct way to increase represen-tation is through quotas (party quotas and legislative quotas) and reserved seats. The main difference between reserved seats and gender quotas is that the first mandates a minimum number of seats for female legislators and the second just a percentage of female candidates among candidates.

As concluded by Pande (2003), this political reservation in Indian states has increased

redistribution of resources in favor of the groups which benefit from political reservation.

Finally, Do women actually make a difference?The paragraphs above present arguments and evidence for how women have different preferences than men and ideas of

policies to increase their representation. But what are the impacts and consequences of

women in public office? Consistent with the hypothesis that women are more altruistic,

Dollar et al. (2001) using a large cross-section of countries, show that increased female

participation in parliaments leads to less corrupt government. In the Brazilian context,

Brollo and Troiano (2012) finds that men are more likely to be involved in irregularities in

public administration and to promote more political patronage than women in municipal

governments. In general, the prevailing evidence supports the conclusion that gender

identity matters for public policy (Chattopadhyay and Duflo, 2004; Pande and Ford,

2011; Schwindt-Bayer, 2006; Clots-Figueras, 2012; Brollo and Troiano, 2012).

2.3

Impacts of women in politics on policy

Women tend to be more on the left in political spectrum (Edlund and Pande, 2002).

Left-wing is traditionally related to a stronger and bigger state, and also to social policies.

Regarding evidence from settings without reservation policies, Rehavi (2007) reports that

the increase in female participation in American state legislatures is responsible for the

rise of the state expenditures on health in 15% and also in reducing the spending trend

on prison system.

Schwindt-Bayer (2006) compares Latin American congresswomen over the past 35

years and finds that women still place higher priority on children, family and women’s

issues. Nowadays, the difference is that the male and female legislators attitude toward

education, health and economy are similar. One point highlighted by Schwindt-Bayer

(2006) is that many times women are restricted to policies related to children and equaly

promotion because men dominate the political status quo and its core issues.

Many studies about the impact of female politicians on policy exploit the reservation

et al., 2009; Gajwani and Zhang, 2014; Clots-Figueras, 2012). In 1993, an amendment

to the Indian Constitution devolved more power over expenditure for village councils

and voted a reservation of one-third of the positions of village’s chief to women. Various

studies were conducted using this change as a natural-experiment. Pande and Ford (2011)

review the literature on the effects of gender quotas on female leadership and policy

outcomes and present ample evidence from India that quotas increase female leadership

and influences policy outcomes. Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004) analyzed the states of

West Bengal and Rajanstan and find that women leaders choose policies more related to

women’s needs and concerns (i.e. drinking water).

Nevertheless, there are articles that fail to find evidence of gender impacting policy

outcomes. Gagliarducci and Paserman (2012) and Ferreira and Gyourko (2011) do not

find impact of female politicians on expenditures in the context of Italian and U.S.

mu-nicipalities, respectively. Ban and Rao (2008), using the reservations in India, show that

female leaders do not perform better than male leaders in South India and, differently

from Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004), they have no evidence that women occupying

reserved seats converge to the preferences of women2

. Using Indian household surveys

instead of data provided by the government, Bardhan et al. (2009) also do not find any

effect of women reservation seats on targeting the provision of public good to women.

Still on India empirical evidence, Clots-Figueras (2012) compares female and male

candidates for states assemblies using close elections to study the impact of leader’s

gender on education outcomes. She studies the impact of female leaders in legislative

positions on education in a sample of Indian citizens between 13 and 39 years old in 1999

and 2000. Her focus is on pupil achievement discriminating the effects between boys

and girls, finding that the 10% increase of women political representation increases the

probability of a student (both girls and boys) finishing school in urban areas in 7%. No

effects of female representation are found in rural areas or on the whole sample.

Svaleryd (2009) exploring a change in the number of seats in local councils in

Swe-2

den, studies whether the level of female representation in municipal councils affects local

public expenditure in Sweden. She finds that a bigger female participation increases the

expenditures on day care centers and education over elderly expenditures.

Also studying gender effects in a municipalities context, Ferreira and Gyourko (2011)

show that, in the US cities, female mayors do not perform better than men in policy

outcomes related to municipal spending, employment and criminal rates, corroborating

my findings. They also find that women win more elections in richer cities and with

higher education levels, where they also have a higher probability of reelection.

In Brazil, there are no gender quotas for elected positionsper se. There exists an

affir-mative action requirement that 30% of candidates in every party list be women (art. 10,

paragraph 3, Law 9504/97). This affects only election for municipal and state assemblies

and the lower chamber of Congress, without such requirements for executive positions

and for the Senate. However, party quotas are not effective in electing women because

of open list electoral system. For this reason, political representation in Brazil cannot

be studied based on quotas. Instead, I use marginal elections for executive positions to

examine the impact of women in policy outcomes.

Brollo and Troiano (2012) have employed a similar design to investigate the role of

women as policymakers in Brazilian cities. They analyze the effect of female mayors on

total discretionary transfer for capital investment, health outcomes, specifically prenatal

care delivery and corruption on municipal governments. They find that the gender does

matter for these outcomes. My paper is closely related to Brollo and Troiano (2012), but

I intend to explain the effects on education. However, differently from Brollo and Troiano

(2012), my findings are consistent with previous literature. On future sections, I propose

a discussion about possible explanations for these differences in results.

More precisely, I study the impact of the mayor leadership differentiated by

gen-der on education. If women care about children issues and are inequality-averse and

pro-redistribution (and education is the main force for fighting poverty and inequality

(Machado, 2011; Barros et al., 2000)), one should expect that female policy-makers would

fe-male victory. Based on the literature presented, I formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 Municipalities governed by women should have better education outcomes, measured by Basic Education Development Index and Prova Brasil indicators.

Hypothesis 2 Municipalities governed by women should increase the education expen-ditures and agreements ("convênios") as well as have more local practices to improve

education.

In addiction, I also explore a sub-group analysis differentiating between municipalities

located in rural and urban areas. As described above, Clots-Figueras (2012) finds effects

in urban areas, justifying that the returns for education in these areas are higher. Unlike

Clots-Figueras (2012), I expect to find effects in rural areas, given that mayors in rural

cities have more information on the citizen’s demands and electing women in rural cities

may be more difficult due to gender discrimination. My hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3 Municipalities in rural areas governed by women should present higher education outcomes and more local education practices aiming to improve education

(cre-ation of educ(cre-ation plan, council, fund, and hiring and training policies for teachers)

In the next sections, I present the institutional background in which the analysis

occurred, the data used, the empirical strategy employed, the results found and finally

the conclusion.

3 Institutional Background

Brazil is a federal state composed of 27 units, further subdivided into 5,570 municipalities.

Chief executive and legislators are directly elected at all levels. Political structure of the

local levels mimics the presidential arrangement of the central government, except that

states and municipalities have a unicameral legislature. Mayors in most municipalities

are elected by a plurality system, but in those municipalities with more than 200,000

top two candidates. Municipal elections in Brazil take place every four years, two years

after the elections for president, governors, and members of Congress.

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 was written based on two elements: popular

par-ticipation and decentralization (Souza, 2001). It gives the states wide powers on policing

and criminal justice, and sharing responsibility with the federal government on health,

education and infrastructure. Accordingly, municipal governments share these obligations

with state and federal governments, however, having strong roles on public

transporta-tion, primary educatransporta-tion, health and land use. In relation to educatransporta-tion, it stated that"the Union, the states, the Federal District and the municipalities will organize, in collabora-tion arrangements, their educacollabora-tion systems"3

. In addiction, the new Lei de Diretrizes e

Bases da Educação Brasileira was established, enabling the foundation of legal provisions

to promote national education.

Although, different taxes are collected at all levels, creating a complicated system of transfers between federal, state and municipal governments, both state and municipal governments effectively depend on federal transfers for financing their activities. For example, the states collect the ICMS (tax on transactions on the circulation of goods and services) and transfer a percentage to the municipalities. In education, the main source of resources is federal. In the 1990s, the federal government, aiming at unifying the education system, created a national curriculum, a national evaluation agency and a new funding system, the FUNDEF (Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento do Ensino Fundamental

e de Valorização do Magistério). The FUNDEF would guarantee a minimum budget

for education spending for all municipalities. In the 2000s, the FUNDEF was renamed as the FUNDEB (Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de

Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação). The FUNDEB is a state level fund, formed

almost entirely by resources from state and municipal transfers linked to education. The municipalities can also establish municipal funds, created by municipal law, aiming to raise resources for specific objectives.

The main reason such instruments were created was to ensure that a certain amount

3

of money would effectively be spent in education. Resources from taxes and transfers

constitute the fund. Another option that mayors have to increase the budget is through

agreements between the local government and private or public sector (i.e. other levels

of government) to achieve a common goal – convênios. The convênios is a partnership

with obligations for both sides, in which one side transfer the resources and the other

uses them according to the agreement and presents reports of accountability.

Thus, educational budgets are relatively rigid and the mayor has the capability to

decide on educational policies and how to allocate the spending devoted to primary

education. There are administrative bureaucracies to control and implement the policies

as Secretaria de Educação. The mayors appoint the "education manager", secretário de

educação, who serves at her discretion and has direct decision power on education policy

and monitoring schools.

TheSecretaria de Educaçãohas the goal of defining the municipality education policies

and coordinating its implementation and evaluation. To improve the quality of education,

the secretário can employ mechanisms such as the municipal education plan (PME), the

municipal education councils (CME), other municipal funds, among others, established by the Constitution of 19884

. It is worth noting that education councils are important mechanisms to improve education. They are mediators and articulators between the government and the population, increasing popular participation on the decision making process. They are presupposed by the Constitution, but they are created separately in each municipality: the Secretaria de Educação proposes a committee composed by representatives from several segments of society to debate proposals about CME. Next, the law draft of CME’s creation is forwarded to the mayor, who is responsible to turn in the bill to municipal legislators. Being approved by the legislature, the Secretaria

de Educação is in charge of arranging the first election that appoints the committee

accountable for defining the functions of CME.

The federal government assesses the quality of education in different municipalities by Basic Education Development Index (IDEB). The IDEB was created in 2007 as the

4

main innovation of Education Development Plan (PDE) of the federal government. The

main goal was to create a synthetic indicator of education quality, based on based on

two important education indicators: academic passing rate obtained from School Census

and the results ofProva Brasil. TheProva Brasil measures the students’ performance on

Math and Portuguese exams at the end of school year in basic education (5th, 9th year).

The schools selected to the evaluation are those that have at least 20 students enrolled

in 5th and 9th years. Finally, the IDEB takes the average passing rate of schools and

the average of grades in Math and Portuguese test taken (Buchmann and Neri, 2008),

ranging on a scale from 0 to 10.

To investigate the impact of women mayors on education, I explore both "outcomes" and "outputs". As a measure of education outcome I use IDEB and the scores in Math and Portuguese exams. For education outputs, I examine the effects of mayorship on educational expenditures and local management practices, more specifically, municipal education plan, councils, funds and policies of training and hiring teachers. I also extend the study to a sub-group analysis, to explore the effects of female mayor only in rural and urban areas. I suppose that female mayors would behavior differently, affecting education, but my hypothesis is not confirmed. In the next section, I describe the data and empirical strategy used and the results obtained from a quasi-experiment approach.

4 Empirical Strategy

4.1

Data

In this section I describe the data used and how I combined different data sources. The outcomes analyzed are both education indicators as well as local education policies.

a woman and a man, irrespective of order and the number of candidates. This sampling is

different from Brollo and Troiano (2012), who consider only elections with two candidates,

one woman and one man, discarding municipalities where there were more than two

candidates. This lead to 626 municipalities in 2004 and 663 in 2008, in which women

won in 276 in 2004 and 269 in 2008.

As a measure of educational outcomes, I use the Basic Education Development Index

(IDEB), provided by INEP (Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais

Anisio Teixeira) . I use the Ideb index as well as Math and Portuguese exams results. I

use the Ideb for the years 2007, 2009 and 2011, examining the outcomes for 3 years after

(IDEBs 2007 and 2011) for both elections as well as 5 years after (IDEB 2009) and 7

years after (IDEB 2011) the 2004 elections.

I also gathered data on local management practices using the Instituto Brasileiro de

Geografia e Estatística, IBGE’s dataset,Perfil dos Municípios Brasileiros (Munic). Munic

carries a detailed survey about the structure and internal functioning of the municipalities’

governments. I work with the surveys related to years 2006 (for mayors who won the 2004

elections) and 2009 (for mayors who won the 2008 elections). I also use some variables

from Munic 2011, that were not available in the 2009 survey. Variables analyzed are:

the existence of municipal education plan, municipal education funds, the municipal

education council and policies focused on training and hiring teachers. A timeline of

events is sketched in figure 1.

Figure 1: Timeline of Events

2004 Ele ctio ns 2005 ID EB 2006 Mun icI 2007 ID EB 2008 Ele ctio ns 2009 ID EB Mun icII 2011 ID EB Mun icII

Additionally, to include data on public finance, I collected data from the National

Treasury,Finanças Brasileiras (Finbra), which contains information on expenditures and

revenues for each Brazilian municipality for every year since 2001. With these data, I

first year of term, in which the mayor inherit his/her predecessor’s finances. As pointed

out before, mayors have sort of influence on allocating the money destined for education.

Furthermore, I also collected data on discretionary transfers (convênios), from the

Controladoria Geral da União. Theconvênio is an instrument that defines a commitment

between two participants, eg. federal government and city hall, with a specific goal. I

use all types of convenios (ie. concluded or not) because I am interested in examining

the mayor’s effort to increase the quality and investment in education, rather than if the

money was directly spent. Thereby, it can be a proxy for mayor’s effort.

Lastly, demographic and economic data for municipalities comes from the Instituto

Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). The censuses from 2000 and 2010 provide

information about population, poverty rates, radio coverage, income levels, etc. I

aggre-gate the electoral data at the municipality level in order to merge with IDEB, Finbra

and Munic databases. Hence, I have my data organized by municipalities for the years

of 2004 and 2008. In total, there are 2556 observations, 1278 for each year. In 2004, 276

municipalities are treated (women won) and 349 are control (men won). In 2008, the

numbers are 269 and 394, respectively.

4.2

Identification Strategy

My study estimates the effect of female mayors on educational outcomes. Ideally, we

would want to compare two identical municipalities, one governed by a female mayor

and the other governed by a man. Obviously, municipalities that elect women might

be different then those that elect men, introducing selection bias in a naive estimation.

To resolve this problem it is necessary to simulate the counterfactual to determine what

would have happened to municipalities that elected women had they elected men. Thus, I

employ a regression discontinuity design (RDD) to identify causal effects. The treatment

is determined by an observed variable known as forcing variable or running variable,

which shifts the outcome of interest discontinuously at a known cutoff or cutpoint.

I use close elections where female candidates barely won or lost the elections against

(Lee, 2008; Fujiwara, 2010; Titiunik, 2009; Brollo and Nannicini, 2011; Brollo and Troiano,

2012; Boas and Hidalgo, 2011; Ferreira and Gyourko, 2011). The forcing variable is the

margin of victory, constructed from the share of votes that each candidate received. I

then subtract the votes that the female candidate received from the male’s votes and I

get the margin that varies between -1 and 1, being positive when a female candidate wins

the election and male otherwise. The cutpoint is based on margin of victory determining

which municipalities are in the control group (man wins) or treatment group (woman

wins).

The basic assumptions of the RDD are that (1) conditional on confounders, all other

variables should be continuous regarding the assignment variable and (2) ignorability,

i.e. treatment must be as good as randomly assigned conditional on observable variables.

Although we can not be sure if these assumptions are met, we can check for discontinuities

in covariates where there should be none. Indeed, there are no discontinuities as presented

in the graphs in appendix. Table 1 below displays summary statistics for municipalities,

containing characteristics from the 2000 Census, Ideb indicator for pre-treatment period

and expenditures also for pre-treatment period, the last two being baseline indicators.

From table 1 we notice the differences in means between municipalities where women

won and where women lost in all sample. Municipalities in both groups present similar

levels of female and rural populations, education, income and access to water and radio.

In general, the municipalities are small, poor and poorly educated. Together, these results

suggests that the sample is balanced.

Following Imbens and Lemieux (2008), it is also necessary to examine the density

of observations of forcing variable through McCracry test (McCrary, 2008) to check if

there is a manipulation of the treatment. If there is a discontinuity in the density of

the assignment variable at the cutpoint, this may suggest that the subjects were able to

manipulate their treatment condition, invalidating the continuity assumptions of RDD.

In elections, hardly the forcing variable would be manipulated. But in an education

setting, for example, if students are allowed to retakes exams until they pass, there will

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics: Difference in Means

Women lost Women win

N Mean N Mean Difference P-value

Population 737 19,583 539 19,730 -148 .936

Female population (%) 737 .492 539 .491 .000247 .76

Rural population (%) 733 .43 537 .421 .00896 .47

Years of study 737 3.65 539 3.64 .008 .883

Illiteracy 737 .254 539 .257 -.00302 .663

School attendance 737 .298 539 .301 -.0024 .429

Fertility 737 2.61 539 2.64 -.0267 .252

Per capita income household 737 173 539 175 -1.83 .737

Households water 737 .544 539 .548 -.00405 .758

Households radio 737 .776 539 .771 .00533 .489

Expenditure on education, pre 731 5165234 541 4807924 357,310 .431

IDEB 1 Year After Election 637 3.82 477 3.77 .0525 .428

case, I decided to report the McCrary text in figure 6 in appendix.

The most common trade-off in a RDD setting is one between bias and efficiency. When

defining the bandwidth around the cutpoint, the number of units analyzed increases,

reducing the estimated variance, or in other words, increasing efficiency. However, it

also increases the risk of bias, enlarging the chances that omitted variables will bias the

estimated treatment effect. In a more experimental approach, we may say that assignment

to treatment is "as if random" close to the threshold, i.e. the analysis gets very close to experimental design (Dunning, 2012). This would suggest using a very narrow band around the cutpoit.

Imbens and Kalyanaraman, 2009; Calonico et al., 2014b). Imbens and Lemieux (2008)

opt for a method based on cross-validation procedure, where estimating the regression

function at the boundary (tailored to the specific features of the RDD). Imbens and

Kalyanaraman (2009) and Calonico et al. (2014b) propose a fully data driven optimal

bandwidth choice not tailored to the specif features of the RDD. The former estimates by

local linear regression while the second uses local polynomial with robust bias-corrected

confidence intervals.

I do my analysis using three specifications: mean differences with narrower bandwidth

of 0.075 (Dunning, 2012); local linear regressions using the optimal bandwidth calculated

by Imbens and Kalyanaraman (2009) and polynomial model specified by Calonico et al.

(2014b) with their optimal bandwidth.

The first specification of differences of means is estimated thought the simple

regres-sion:

Yi =β0+β1Di+✏i (1)

where Yi represents education outcomes; Di is the dummy indicating treatment (i.e.

treated if margin of victory in municipality is positive).

In second approach, I formally estimate the following local linear regression, using the

optimal bandwidth calculated by Imbens and Kalyanaraman (2009):

Yi =β0+β1Xi+β2Di+β3Xi·Di+✏i (2)

where Yi stands for education outcomes, Xi is margin of victory in municipality i, Di

is the dummy indicating treatment (i.e. Xi >0) and Xi ·Di is the interaction between

margin and dummy (intercept break with trend).

In the third approach, I use the algorithm created by Calonico et al. (2014b), which

chooses the polynomial degree of best model according to data behavior.

Thus, I estimate these regressions for education outcomes (IDEB, Math, Portuguese)

also teachers hiring and training policies. Next section, I present the results for the

outcomes and outputs and then I proceed to the discussion about the findings.

5 Results

5.1

Education outcomes

In this section I describe the main results obtained from the analysis of impact of a female

candidate winning the election. I start reporting my results in table 2 for education

outcomes, based on Ideb indicators as well as on Math and Portuguese exams of Prova

Brasil. These outcomes are divided in 3, 5 and 7 years after the election, in which the

women were elected.

One important issue in RD setup is the graphic visualization. Many scholars have

been looking for ways to improve the plots showing RDD results (Bueno and Tuñón,

2015; Calonico et al., 2014a). I expose the simplest but fundamental graph for regression

discontinuity — scatterplots of the outcomes of interest on the forcing variable. This

graph is sufficient to notice that there is no discontinuity at the cutpoint, indicating that

the treatment does not have any effect.

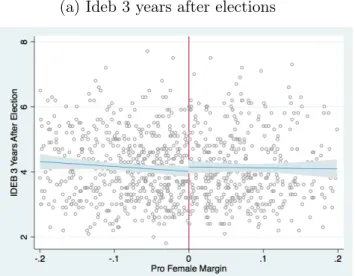

Figure 2 shows the scatterplots of IDEB. The variable on the x-axis is the margin

of victory and the red line if the cupoint 0. The bandwidth presented in the graphs is

0.2, value that include all the bands calculated by IK. I plot a linear function in blue

and confidence interval in gray. We see that there is no discontinuity in the cutpoint

for IDEB. I choose to report graphs only for IDEB outcomes, because all the outcomes

present the same pattern.

For all education outcomes, I report the results for three different specifications:

dif-ferences in means with a narrower bandwidth of 0.075, the local linear regressions with

optimal bandwidths based on Imbens and Kalyanaraman (2009) (IK) and polynomial

model for CCT optimal bandwidths (Calonico et al., 2014b). Table 2 presents the

treat-ment effect, robust standard errors in parentheses, number of observations in each

Figure 2: The Impact of Gender on Education Outcomes

(a) Ideb 3 years after elections

(b) Ideb 5 years after elections

models. We see that there is no difference in results despite the model used, i.e. for all

specifications the results are very imprecise and without defined direction. In sum, the

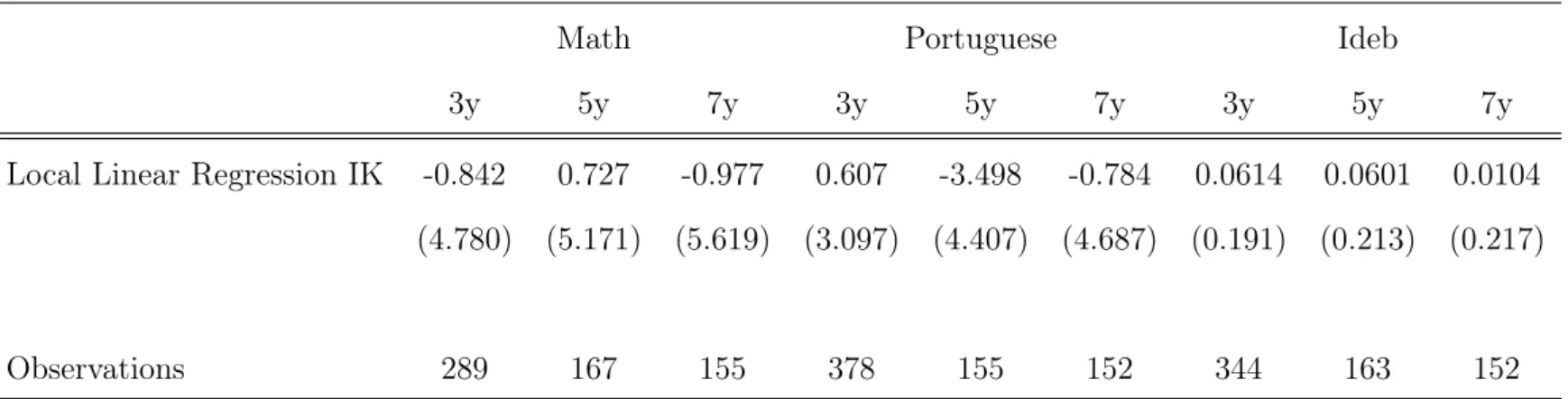

Table 2: Effect of electing a female mayor on education outcomes 3, 5 and 7 years after elections

Math Portuguese Ideb

3y 5y 7y 3y 5y 7y 3y 5y 7y

Difference in Means 1.853 -0.701 -0.353 0.624 -2.230 0.216 0.101 0.00872 0.00336 (2.228) (3.273) (3.470) (1.874) (2.560) (2.814) (0.1000) (0.134) (0.133)

Observations 462 222 221 462 222 221 462 222 221

Bandwidth 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075

Local Linear Regression IK 2.614 -0.286 -3.020 -0.0559 -4.267 -1.786 0.127 -0.0375 -0.0759 (3.372) (4.352) (4.938) (2.200) (3.747) (4.220) (0.129) (0.184) (0.198)

Observations 709 419 389 982 389 379 887 409 379

Bandwidth IK 0.129 0.184 0.159 0.255 0.159 0.152 0.198 0.174 0.152

Polynomial CCT 1.512 -1.193 -1.060 0.329 -3.638 -1.055 0.171 -0.112 -0.0661 (3.509) (5.393) (5.453) (3.002) (4.473) (4.634) (0.161) (0.232) (0.222)

Observations 776 383 392 770 376 392 744 361 382

Bandwidth CCT 0.147 0.17 0.156 0.146 0.16 0.173 0.145 0.153 0.141

Notes. I also estimate for ∆IDEB and no results were found Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

5.2

Education outputs

In this subsection, I investigate whether female mayors have an impact on education

outputs i.e. municipal expenditures on education, agreements (convênios) and municipal

practices focused on education. Table 3 presents results analyzing expenditures on

edu-cation and discretionary transfers. The effect of female mayors on expenditures are very

small and non-significant, indicating an increase in expenditures by 6.7% (difference in

means), 11.1% (IK) and 5% (CCT).

I also analyzed the variation in expenditures (∆Expenditures). In three models, the

results are very small — 0.084 for basic regression of difference in means; 0.094 using

local linear regression and 0.026 in the polynomial model. For agreements, the effect

is the same: no differences between models, with small and non-significant effect. In

sum, following the previous analysis, there is no significant effect of electing a woman on

education expenditures. This means that gender of the mayor does not matter for public

spending, consistent with Ferreira and Gyourko (2011), who also analyzes municipal

expenditures in the United States.

I proceed to the analysis of local education mechanisms that the mayor can apply to

improve education. The dependent variables analyzed are variables of local management

extracted from the MUNIC dataset. They are all dummies variables, indicating if the

municipality has an education plan, an education council or an education fund. Other

variables investigated are if the mayor did policies or programs of training and hiring

teachers and also the community participation in school management.

Figure 3 displays graphs of municipal education plan, council and funds on the

pro-female margin (i.e. bigger than zero when a woman won the elections). The blue line is

linear regression and the confidence intervals are highlighted by gray shading. We see no

Table 3: Effect of female mayor on municipal education expenditures and agreements

Expenditures ∆ Expenditures Agreements

Difference in Means 0.0667 0.0837 0.0625

(0.0803) (0.0926) (0.155)

Observations 485 469 491

Bandwidth 0.075 0.075 0.075

Local Linear Regression IK 0.111 0.0936 0.112

(0.141) (0.160) (0.273)

Observations 595 558 562

Bandwidth IK 0.095 0.092 0.086

Polynomial CCT 0.0504 0.0259 0.158

(0.121) (0.133) (0.244)

Observations 804 770 794

Bandwidth CCT 0.145 0.142 0.14

Robust standard errors in parentheses

Figure 3: The Impact of Gender on Education Policies

(a) Education Plan

(b) Education Council

In table 4, the results for all analyzed variables of local management are displayed.

A women candidate winning mayoral elections increases the probability of municipalities

to have an education plan by 2.4%; this probability increases for education councils and

funds, 6% and fund 3.3%, respectively, non-significantly.

For almost all other variables the effect is very small and non-significant as well, except

for hiring teachers. Having a female mayor decreases the probability of policy for hiring

teachers in 8%, significant at 0.1 level. Despite being significant, the coefficient is so small

and isolated, that I can assert that there are no differences between municipalities where

Table 4: Effect of female mayor on local management

Education Plan Education Council Education Fund Teachers’ training Teachers’ hiring

Difference in Means 0.0239 0.0608 0.0332 -0.0283 -0.0795*

(0.0439) (0.0431) (0.0443) (0.0331) (0.0423)

Observations 494 495 495 495 495

Bandwidth 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075 0.075

Local Linear Regression IK -0.0853 0.122 -0.0809 -0.0924 -0.0711

(0.0863) (0.0969) (0.109) (0.0726) (0.106)

Observations 458 320 324 385 327

Bandwidth IK 0.177 0.10 0.103 0.128 0.104

Polynomial CCT 0.00662 0.0662 0.00539 -0.0216 -0.0438

(0.0711) (0.0603) (0.0660) (0.0505) (0.0722)

Observations 868 1,005 900 865 790

Bandwidth CCT 0.162 0.216 0.175 0.160 0.138

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

5.3

Results on rural areas

In this section, I analyze heterogeneous results, in other words, whether the treatment

effect differs across sub-samples. In particular, I study the municipalities that are

con-sidered rural expecting to find effects in these cities. On the other hand, Clots-figueras

(2005) finds positive effect of female leaders only for urban cities. Her main justification

is that in urban areas the education returns are higher.

This categorization is based on the rate of the population living in rural areas, I

separated the groups in rural and urban using the level of 50% of the population living

in rural areas. The table 6 displays the results for municipalities only considered rural.

For education outcomes, there is no gender effect. Nevertheless, when I investigate the

consequence of female mayors on local practices for education, I find a positive effect on

teacher’s training for municipalities where women candidates are winners (increases in

15.2%). It is important to note that the significance is at the lowest level and due to the

fact that it is an isolate effect, it may be difficult to accept as a real effect. It can be a

Table 5: Effects of female mayor on rural areas - Education outcomes

Math Portuguese Ideb

3y 5y 7y 3y 5y 7y 3y 5y 7y

Local Linear Regression IK -0.842 0.727 -0.977 0.607 -3.498 -0.784 0.0614 0.0601 0.0104

(4.780) (5.171) (5.619) (3.097) (4.407) (4.687) (0.191) (0.213) (0.217)

Observations 289 167 155 378 155 152 344 163 152

Table 6: Effects of female mayor on rural areas - Local Management

Education Plan Education Council Education Fund Training Hiring

Local Linear Regression IK -0.0454 0.106 0.0746 0.152** 0.0126

(0.0976) (0.125) (0.121) (0.0674) (0.119)

Observations 374 265 273 322 274

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

6 Discussion

The results presented in section 5 oppose the majority of the literature about the policy

consequences of electing female politicians. The vast majority of the studies shows that

gender has an impact on policy choices with female leaderships making more pro-female

policies. Although the evidence is strong, some studies find no effects of gender on policies

and the study of the causal effect of women in politics is still inconclusive.

As Jayachandran (2014) addresses in her paper about the causes of gender inequality,

poor countries tend to exacerbate male roles in various forms. She presents evidence that

the ratios of female labor force participation and girls enrolled in colleges are very low,

with the effect more prevalent in sub-saharian Africa. In Latin America, the indicators

are better when compared to China and India, where what prevails is the preference for a

male child. Nevertheless, global institutions highlight the importance of gender equality

on economic development and its long path to gender parity in Latin America (Perez,

2015).

Despite these efforts and discussions, the studies of women representation on policy

decisions in Latin America are yet in an initial stage. Usually, the main effects of women

politicians are investigated in India. As pointed by Clots-Figueras (2012), gender roles

are strong in India and they are likely to shape women’s preferences. Besides that,

there are the casts systems, a strong institution that defines preferences and identities.

Thus, endogenous preferences and historical dependencies may justify affirmative action

policies.

Clots-Figueras (2012) also explores the impact of women leaders discriminating

be-tween boys and girls. Another factor that may influence is religion. In India, some

religious families do not allow girls to go to school. Consequently, the investments and

achievements in education for boys and girls are different and female leaders become an

important factor to improve girls’ education and aspirations. De facto, the seats

reser-vation in India implemented a new political institution where people change their views

Thereafter, one of the reasons that gender does not have effect on education policies in

Brazil is due to cultural and social institutions. I believe that Brazilian women also have

strong roles, but the demands and their social identities can be distinct. Differently from

India, women in Brazil arrive in office through electoral races, which might highlight the

median voter theorem effects. Women who are elected by the whole population may feel

obligated to attend the general demands. On the other side, women elected by quotas

may feel subjected to fight for demands from her group that allowed her to have achieved

a political office.

Another possible reason for the lack of results is that voters in the municipalities

of my sample do not demand policies and programs focused on education. Brollo and

Troiano (2012) find results for health policies in a similar set-up, studying small and

poor cities. Machado (2010) shows that poor people consider health more important

than education, because they underestimate the return of education and, consequently,

demand other policies than education. So, in the investigated municipalities some people

would demand other policies than education policies, like health policies as vaccination

and prenatal visits for pregnant women, as found by Brollo and Troiano (2012).

In addiction to these reasons, there are problems with short-term analysis of education

policies. The effects of education are perceived in the long-term and, thereby I do not

find results for my observations of 3, 5 and 7 years after the treatment. In relation to

municipal expenditures, the indicator used in the analysis may not be the best measure

of how the mayor spend the money. More important than analyze the amount of money

for education – that can be more or less fixed — is to explore if these resources are spent

efficiently. According to (Davies, 2007), mayors in Brazil tend to not fulfill the obligation

to spend the resources for education. He concludes that the main problem in Brazilian

education is not lack of funds, but lack of efficiency.

Albeit mayors have discretionary power over local policies, they can be

counter-weighted by the municipal council. So, mayors may not be able to implement their policies

plan without legislative support. In this case, the presence of women in local legislative

presence of female legislators in municipal councils and the relationship between female

mayors and local legislative are possible paths to explore in future research5

.

Beyond that, there is a low representation of woman in parties, candidatures and in

the Brazilian Congress. And some female politicians are fighting for being respected after

some cases of sexism in Brazilian politics. Women are discouraged to join the Brazilian

policy framework and, consequently, we do not see the potential impact that women can

have on public policy. Perhaps policies of gender quotas are a good solution to reverse

this situation.

At last, the analysis is done by a reduced-form, in which there are several consistent

stories about causes and effects. This makes harder to distinguish the effects of female

mayors. In rural areas, for example, there are different social norms that shape preferences

and people’s political behavior.

7 Conclusion

In this paper I investigate the impact of mayor’s gender on educational policies and

outcomes. To do so, I use a regression discontinuity design (RDD) applied to a rich dataset

of Brazilian municipalities to infer a causal effect. I find no significant effects of a female

mayor taking office on educational outcomes and local policies. For education outcomes,

I used the dataset based on the index of basic education (IDEB). For local education

policies, such as an education plan, a council and a fund, I collect data from MUNIC

(IBGE). I also explore the effects on expenditures and agreements("convênios") between municipal governments and other governments (state or federal) or private institutions.

No differences between female and male mayor were found on municipal education. It seems that the gender of the mayor does not affect the education policies of Brazilian municipalities. These results corroborate the median voter theorem (MVT) described my Downs (1957). Given certain conditions, the theorem deduces that politicians choose policies according to the median voter preferences. According to MVT, with the suffrage

5

of women, their demands would be met.

Whether the results found here are conclusive or not, the impact of gender on policies

is an important issue and future research is essential. Possibly there are problems in this

analysis and, thus, it could benefit from certain new elements. For instance, one could

use finer outcomes, such as microdata for schools and for more direct policies. Moreover,

I could try to investigate the effects for even longer periods of time.

Lastly, another path to follow in future research is to explore the difference between

female politicians elected by quotas or through general elections as well as to further

References

Alesina, A. and Giuliano, P. (2011). Preferences for redistribution. Handbook of Social

Economics, 1(1 B):93–131.

Andreoni, J. and Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in

Altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1):293–312.

Ban, R. and Rao, V. (2008). Tokenism or Agency? The Impact of Women’s Reservations

on Village Democracies in South India. Economic Development and Cultural Change,

56(3):501–530.

Bardhan, P., Mookherjee, D., and Torrado, M. L. P. (2009). Impact of Political

Reser-vations in West-Bengal Local Governments on Anti-Poverty Targeting. Journal of

Globalization and Development, Vol 1(1)(Berkeley Electronic Press).

Barros, R. P. D., Henriques, R., and Mendonça, R. (2000). Desigualdade e Pobreza no

Brasil: Retrato de uma Estabilidade Inaceitável.Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais,

15(42).

Barua, A., Davidson, L. F., Rama, D. V., and Thiruvadi, S. (2010). CFO Gender and

Accruals Auality. Accounting Horizons, 24(1):25–39.

Beaman, L., Chattopadhyay, R., Duflo, E., Pande, R., and Topalova, P. (2009).

Pow-erful Women: Does Exposure Reduce Bias? The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

124(4):1497–1540.

Beaman, L., Duflo, E., Pande, R., and Topalova, P. (2012). Female Leadership Raises

Aspirations and Educational Attainment for Girls: A Policy Experiment in India.

Science, (January).

Besley, T. and Coate, S. (1997). An Economic Model of Representative Democracy. The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1):85–114.

Brollo, F. and Nannicini, T. (2011). Tying Your Enemy’s Hands in Close Races: The

Politics of Federal Transfers in Brazil. IZA DP, (5698):1–20.

Brollo, F. and Troiano, U. (2012). What Happens When a Woman Wins a Close Election?

Evidence from Brazil. Working Paper.

Buchmann, G. and Neri, M. (2008). The Brazilian Education Quality Index (Ideb):

Measurement and Incentives Up-grades.Ensaios Econômicos, Escola de Pós Graduação

em Economia (EPGE-FGV), 686.

Bueno, N. S. and Tuñón, G. (2015). Graphical Presentation of Regression Discontinuity

Results. (Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2549841).

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., and Titiunik, R. (2014a). Optimal Data-Driven Regression

Discontinuity Plots. (Ses 1357561).

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., and Titiunik, R. (2014b). Robust data-driven inference

in the regression-discontinuity design. The Stata Journal, 14(4):909–946.

Chattopadhyay, R. and Duflo, E. (2004). Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a

Randomized Policy Experiment in India. Econometrica, 72(5):1409–1443.

Christensen, M. I. (2015). Worldwide Guide to Women in Leadership. From

http://www.guide2womenleaders.com/, (Date of Access: June 01, 2015).

Clots-figueras, I. (2005). Women in Politics: Evidence from the Indian states Women

in Politics. The Suntory and Toyota International Centre for Economics and Related

Disciplines Political Economy and Public Policy Series, 14(October).

Clots-Figueras, I. (2012). Are Female Leaders Good for Education? Evidence from India.

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(1):212–244.

Coutinho, H. G. a. and Fundação Joaquim Nabuco (2012). Conselhos Municipais e

Croson, R. and Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender Differences in Preferences. Journal of

Eco-nomic Literature, 47(2):448–474.

Davies, N. (2007). O Desafio de obrigar os governos a aplicarem a verba legalmente

devida em educação: os casos das prefeituras fluminences do Rio de Janeiro, Niterói e

São Gonçalo. Jornal de Políticais Educacionais, 1(1):3–20.

Dollar, D., Fisman, R., and Gatti, R. (2001). Are women really the "fairer" sex? Cor-ruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 46(4):423–429.

Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy. Journal of

Political Economy, 65(2):135–150.

Duflo, E. (2012). Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of

Eco-nomic Literature, 554:1051–1079.

Dunning, T. (2012). Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Eckel, C. C. and Grossman, P. J. (2008). Differences in the Economic Decisions of Men and Women: Experimental Evidence. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, 1(C):509–519.

Edlund, L. and Pande, R. (2002). Why Have Women Become Left-Wing? The Politi-cal Gender Gap and the Decline in Marriage. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3):917–961.

Ferreira, F. and Gyourko, J. (2011). Does Gender Matter for Political Leadership?

Jour-nal of Public Economics, forthcomin.

Gagliarducci, S. and Paserman, M. D. (2012). Gender interactions within hierarchies:

Evidence from the political arena. Review of Economic Studies, 79(3):1021–1052.

Gajwani, K. and Zhang, X. (2014). Gender and Public Goods Provision in Tamil Nadu’s

Village Governments.

Htun, M. (2004). Is Gender like Ethnicity? The Political Representation of Identity

Groups. Perspectives on Politics, 2(03).

Imbens, G. W. and Kalyanaraman, K. (2009). Optimal Bandwidth Choice for the

Re-gression Discontinuity Estimator.

Imbens, G. W. and Lemieux, T. (2008). Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to

practice. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2):615–635.

Inter-Parliamentary Union (2015). Women in National Parliaments. From

http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm, (Date of Access: June 01, 2015).

Jayachandran, S. (2014). The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries.

7(November).

Krook, M. L. (2013). Electoral Gender Quotas: A Conceptual Analysis. Comparative

Political Studies, page 27.

Lee, D. S. (2008). Randomized experiments from non-random selection in U.S. House

elections. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2):675–697.

Lott Jr, J. R. and Kenny, L. W. (1999). Did Women’s Suffrage Change the Size and

Scope of Government? Journal of Political Economy, 107(6, Part 1):1163.

Machado, F. V. P. (2010). Poverty, Inequality and Citizens’ Preferences for Social

Spend-ing: the case of Brazil.

Machado, F. V. P. (2011). Does Inequality breed Altruism or Selfishness? Gauging

In-dividuals’ Predispositions Towards Redistributive Schemes. SSRN Electronic Journal,

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women?

A Contingent"Yes". The Journal of Politics, 61(03):628.

McCrary, J. (2008). Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2):698–714.

Miller, G. (2008). Women’s Suffrage, Political Responsiveness, and Child Survival in American History. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3):1287–1327.

Moran, B. (1992). Gender Differences in Leadership. Library trends, 40(3):475–91.

Osborne, M. J. and Slivinski, a. L. (1996). A model of political competition with citizen-candidates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, (February).

Pande, R. (2003). Can Mandated Political Representation Increase Policy Influence for Disadvantaged Minorities? Theory and Evidence from India. The American Economic

Review, 93(04):1132–1151.

Pande, R. and Ford, D. (2011). Gender Quotas and Female Leadership. World

Develop-ment Report on Gender.

Perez, R. (2015). Why Gender Parity Matters for Latin America. World Economic Fo-rum, (Avaiable in: https://agenda.weforum.org/2015/05/why-gender-parity-matters-for-latin-america/).

Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The Concept of Representation. University of California Press. Powell, M. and Ansic, D. (1997). Gender differences in risk behaviour in financial

decision-making: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18(6):605–628.

Rehavi, M. M. (2007). Sex and Politics : Do Female Legislators Affect State Spending ?

Mimeo (University of California, Berkeley), pages 1–57.