Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System

Rubens Penha Cysne **

Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria ***

July 1997

Addresses for Contact:

Rubens Penha Cysne

Escola de Pós Graduação em Economia da Fundação Getulio Vargas

Praia de Botafogo 190, 110. andar, Sala 1124 Rio de Janeiro -RJ -Brasil

Diretoria de Pesquisa

Telephone: +55-21-552-5099

Fax: +55-21-536-9409

e-mail: rubens@fgv.br

Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria IBRE/CECON

Fundação Getulio Vargas

Praia de Botafogo 190, 9° andar, Sala 923 Rio de Janeiro -RJ -Brasil

Telephone: +55-21-536-9299

Fax: +55-21-551-2799

e-mail: laurof@fgv.br

Rubens Penha Cysne is Research Director at the Getulio Vargas Foundation Graduate School of Economics and Director of its State Reforro Studies Center .

••• Lauro Aávio Vieira de Faria is Chief Editor of the magazine Conjuntura Econômica and former Superintendent of Economic Projects

and Studies for the Securities Exchange Commission (CVM).

This paper belongs to the set of papers from CERES -State Reforro Studies Center ofEPGEJ FGV.

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System

I • Macroeconomic Aspects of the Financiai System

1.1 Introduction

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

The Brazilian financiaI system needs to move towards a greater autonomy of a currency controlling agency, more efficient bank supervision (preventive) and self-determined by the market, less instability in the rules of the game, the existence of more technically defensible deposits insurance mechanisms, increase in the portion of credit allocated by market mechanisms, reduction in the taxation and lower reserve requirements charged on deposits, a public debt with greater facility for the monetary policy (involving an extension of its profile and less use of securities bound to short term interest), as well as a more active and less concentrated capital market (whether in terms of stock or stock holders).

As a basic condition for the Brazilian financiaI system to perform its duties satisfactorily, however, there is still an urgent need to adjust public accounts, which have deteriorated substantially during 1995 and 1996.' Without this, the Central Bank will continue to see itself endogenously obliged to continue regulating and operating to provide the govemment with cheaper funds.

1.2- Development Funding

An important item to be discussed is the question of financing the overall national infrastructure, bearing in mind the need to revive the development processo Taking into consideration the relative price of capital goods, it is found that between 1971 and 1982 the gross formation of fixed capital in Brazil was equal to 21.6% of the GDP. Between 1983 and 1988 this figure dropped to 17.2% of the GDP. More recently, between 1989 and 1994, the gross fixed capital formation was a scanty 14.8% of the GDP. In the three periods, the average GDP growth rates were 6.4% between 1971 and 1982, 3.4% between 1983 and 1988 and 1.1 % between 1989 and 1994, respectively. To again be in a growth situation it is necessary to have favorable expectations and a retum to public saving.

Govemment savings (calculated on real interest) has been negative in recent years, having dropped from 6.4% of the GDP between 1970 and 1974 to -1.9% of the GDP between 1990 and 1994. The drop of 8.3 percent in the GDP has been continuous, bearing in mind the figures of 5.3% between 1975 and 1979, 2.0% between 1980 and 1984, and -1.2% of the GDP between 1985 and 1989. It is interesting to see how the drop in govemment savings during the 1970s to the period of 1990-1994 (from 6.0% to -1.9% of the GDP) is practically equal to the drop in gross capital formation for the same period (from 21.6% to somewhere around

14.8% ofthe GDP).

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

The average profitability of the central govemment as a major stockholder in state-owned companies was only 0.4% over the invested capital between 1988 and 1994. By the end of 1994, the central govemment held R$ 88 biIlion of capital in stock in state-owned companies. The sale of such stock with a respective repurchase of the debt, working with an interest rate of 15% per year, would produce an annual net savings of2.0% ofthe GDP. Not to mention privatizations by the states and revenue from concession auctions. Moreover, these calculations do not include the higher tax collection from the increase in productivity and profits of privatized companies. This increase in productivity is evident when compared with the productivity on the govemment's risk capital of 0.4% a year and the 500 largest companies, which between 1988 and 1994 gave an average profitability on net equity of7.6% a year.

Another more politicaIly complicated form of increasing public savings, but with great impact, is by reforming the social security. In this sense, the reform should be at least partly ruled by the capitalization mechanism. The federal govemment' s expenditure with the National Social Security Institute (INSS) and the central govemment's inactive assets rose from 4% in 1989 to 7.8% of the GDP in 1995, largely due to the increases in benefits stipulated by the 1988 Constitution.

The social security reform is important not only because it wiIl permit the recovery of govemment savings, after the difficult transition stage from the old to new system (which may be mitigated by instituting a mixed system), but also by encouraging private savings. Chile successfuIly increased its savings rate from 13.8% ofthe GDP in 1987, when the social security reform was implemented, to 21.2% in 1994.

It is also worth mentioning the positive effects ofthese reforms (social security and equity) in the sense of reducing the public debt risks and its financing costs. In particular, it is also found that the National Treasury, consolidated to the Central Bank, has incurred losses as a result of the accumulation of approximately R$ 60 billion reserves in Central Bank assets, reducing public savings. Such reserves are funded by liabilities which yield a variation of about 11 % a year over the doIlar. On the intemational market, the reserves are invested at rates of 6.5% a year, costing the Central Bank something around 4.5% a year to maintain them. This is an annual cost of R$ 2.7 billion. The govemment regards this cost, which was higher in 1995, as an insurance premium for the Real Plano A premium which may also be reduced after the macroeconomic fundamentaIs of the Real Plan are on the proper course.

Comments on lhe Brazilian Financiai System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

11 -

Performance in Saving RatesBefore trying to assess the Brazilian savings for each sector, we must bear in mind a problem conceming the form of calculating the national accounts in Brazil by the IBGE Foundation, which uses only nominal interest accounting, in detriment to a more suitable procedure, which would be to evaluate the different macroeconomic aggregates belonging to the national accounts also on a real interest basis. When attempting to assess the contribution of each sector (family and corporate, govemment and intemational) in Brazil to form savings, we reach, as a result of the normally high inflation and consequent restatement on the public debt, overestimated private sector gross savings and underestimated govemment savings. This fact is clearly shown in the following graph which shows the performance of these two variables over the years. A clear broadening of the skew trend between those two different series when inflation increases in the last years of the period under study, basically due to using nominal interest in ca1culating the division of income between each of these sectors. In the last years of the series it is seen that the increase in private savings is absorbed by reduced govemment savings ..

GRAPHII.l

Performance in Time of Private and Govemment Savings

O,51-;::==========:::;---~

--Govt.Savings/GOP

0.4 - • • PrivaIs Savings/GOP

0,3

0,2 Ir- .. "

...

'-.-'

-.""--."

...

-

...

,.'

-.--"

....

"..,

..

' 0,1-0,1

.. ~

I •

,

,

'

,

\ • A

I U ..

- 0 , 2 . . 1 . . . - - - " " ' - - - '

1947194919511953195519571959196119631965 1967196919711973197519771979198119831985 198719891991 1993 Years

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System

TABLE 11.1

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

A verage Saving Rates in Brazil as % of the GDP

.9,73%0. .:0.78% 0,54%

·3.~9%

13,?3%

15;9$0/0

17,83% 22.67%

72 o 17 8° 1 47° 1

o

°0Sources: National Accounts System - 1939-1947/1969, 2nd ed., Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV), 1973; Historical Statistics ofBrazil, VoI. 3, IBGE, 1986; Aries Project - FGV.

As a complement to graph TI. 1 , a drop of 9 percent of the GDP is c1early seen in table TI.2 1.2 under government savings from the 1970s to 1980s, when inflation rose steadily as the private

sector gross savings rose during the same period.

Assuming an absence of a monetary illusion, the govemment' s contribution to forming the country's total savings would be much better measured in real interest accounting. For theoretical considerations in this respect, see, among others, Simonsen & Cysne (1989 or 1995).

The problem of using nominal or real interest can be overcome in table TI.l if we stay with

domestic savings, which corresponds to the sum of government savings with the private sector gross savings. It is found that domestic savings increased in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, when it then reached the rate of 19.2% of the GDP. In the eighties domestic savings dropped to 18.9% of the GDP, presenting, nevertheless, a slight recovery in the first four years of the nineties, when it reached 20.2% of the GDP.

International savings as a percentage of the GDP rose slightly in the fifties in relation to the

last three years of the forties, dropped in the sixties and then rose substantially in the seventies when it was 3.5% of the GDP. This trend was reversed in the next two decades, when

international savings dropped back to 2.0% of the GDP in the eighties and was practically

zero in the first four years of the nineties. 1995 features another backward trend with intemational savings of 3.5% of the GDP.

Moving on to total savings, a persistent increase is seen in the averages in each decade until the end of the seventies, when it was 22.7% of the GDP. Since the eighties, however, Brazil's

total savings showed a downward trend which continued into the first years of the nineties.

Comments on lhe Brazilian Financiai System

IH- Performance of the Brazilian Financiai System

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

At least five basic tasks must be expected of the financiaI system in any economy. Two of them are attributed to the monetary financiaI system, formed by the Central Bank and commercial banks which receive demand deposits. These are the settlement functions and the management function of the money supply. The other three tasks are attributed to the financiaI system as a whole, and so the efficient intermediation of resources between the economic agents is included, facilitating allocative and productive efficiency, protection against risk and cut in costs in the event of mergers and market takeovers, which increase corporate administrative efficiency.

It is known (King & Levine, 1993b) that higher degrees of financiaI intermediation are normally positively associated with the rise in productivity. The problem is that the Brazilian financiaI system has cost annually somewhere around 13.9% of the GDP (average for

1990-1994, while in 1995 there was a drop to 8.3% of the GDP, IBGE data), quite a high figure when compared to those of such stable economies as the United States and Germany, where this cost does not normally exceed 5% of the GDP. It is worth seeing if this high cost has been paid for through the efficient performance of the five aforementioned tasks.

With the exception of the settlement task, very well performed in Brazil, bearing in mind the strong market stimuli in this sense when inflation was high, the answer to the four other requisites is not very positive. Let us start with the question of money stability.

In this particular item, our performance has always been poor with regard to inflation rates and money spread in Brazil. The fact that Brazil, since the 1950s, shows an average welfare cost of inflation of 3.1% of the GDP (Simonsen & Cysne, 1994) and an inflationary transfer of 4.2% from the non-banking sector to the banking sector of the economy leaves no room for doubt: the institutional design of the Central Bank since its creation has not been successful, needs to be modified and the institution given greater autonomy.

It is found particularly that only 2.2 % of the aforementioned 4.2 % of the GDP refers to inflationary taxation, the rest going to the commercial banks. In other words, historically, the Central Bank inflicted on the country a cost of 3.1 % to collect 2.2% of the GDP.

Cornrnents on the Brazilian FinanciaI Systern Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

It is also clear that the central bank to which you need to give autonomy is not the Brazilian kind, which has too many attributes, but is rather the classic type, restricted to its functions as the banker of the govemment (not eXclusive) and of the banks, depository of BraziI's intemationaI reserves and which manages the money suppIy.

Let us now move on to the financiaI system's third task, that of intermediating savings for investments. In this sense, the negative assessment begins when observing the following fact: between 1971 and 1982, BraziI's gross formation of fixed capital was equal to 21.6% of the GDP; between 1989 and 1994, this dropped to 14.8% of the GDP, a drop of seven percent. Something, therefore, is fundamentally wrong with the Brazilian economy in the past few years. Would the origin of this ailment be in our financiaI system, precisely in so well remunerated a sector, with a high concentration of human capital? No, not the origin but rather the instmment. The troubles obviously originate in the increase in govemment spending not destined for capital formation. On this basis, the financiaI system becomes a vehicle operated in order to reduce the cost of covering the public deficit, bearing in mind its low financing capacity by the market.

This point is evident when it is seen that, in a period equal to that which we have just mentioned above, govemment savings showed the same drop, that is seven percent of the GDP. Govemment savings (calculated at real interest) was around 5.0% of the GDP in the 1970s, having fallen to somewhere around -2.0% of the GDP between 1990 and 1994. In other words, the drop in gross capital formation is easily explained by the increase in excess consumer spending, subsidies, interest payment and social security transfers over the total tax revenue.

The mIes which guide the Brazilian financiaI system's operation have usually been made taking as the ultimate guiding element an offset to the problem of imbalance in public accounts. This problem can arise in any other country, but it is endogenous and particularly a.ccentuated in Brazil for two reasons;

i. the lack of limits in re-issuing Temporary Measures, which has made this legal instmment potentially more detrimental than the Decree Law (the latter was approved by lapse of time while the former was re-issued by lapse oftime);

ii. the Central Bank's reduced autonomy, causing this institution to usually be led to legislate and operate and obtaining resources for the govemment as a background.

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System

IV . State and Federal Bank Reforms

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

There are several theoretical arguments to explain why public companies tend to be more inefficient that private companies. The absence of any bankruptcy risk would hinder an administrative takeover by a more competent team. Greater job stability would reduce the employees' efforts which can be monitored indirectly. Moreover, the Iack of administrative flexibility would lead to a slower pace in the buying and selling operations, implying larger stocks, hence higher costs, in addition to grasping less market opportunities.

As theoretical arguments may always be queried, albeit sometimes without much deference to common sense, it is worth giving some empiricaI examples in the case of the public financiaI sector.

According to Andima & IBGE (1997), in 1995 the size of the public financiaI institutions, measured by the share in the GDP, was 3.20%, and of the private 3.59%, that is, the public representing 47% and the private institutions 53% of the total. It might then be expected that, with the drop in inflation since July 1994, the financiaI marketability assistance to the official and private bank sector would folIow the same trend. This, however, does not occur. According to data published in the Central Bank BulIetin of ApriI 1997, between July 1994 and January 1997 the stock of financiaI marketability assistance to the official banks Ieaped from R$ 4.2 billion to R$ 44.1 billion, while financiaI assistance to the private banking sector leaped from R$ 0.01 billion to R$ 27.0 billion.

In other words, the financiaI assistance provided after the Real (not to be confused with subsidy) was approximately R$ 40 billion for official banks and R$ 27 billion for the state banks. Therefore, the official banking sector, which represents only 47% of the total added value in the financiaI intermediation, was responsible for approximately 60% of the financiaI assistance provided by the Central Bank.

In a short parenthesis, it is important to note that of such variations in the Central Bank asset accounts of R$ 40 billion and R$ 27 billion respectively, Central Bank non-performing fund transfers to the banking system do not apply, but rather loans, capitalization andlor assets exchange of the bank portfolio for securities issued by the Central Bank. The possible subsidies involved depend on the exchange conditions of the securities taken in relation to their market values, a fact which we do not intend to discuss here.

Secondly, although, as we have seen, only 47% of the value added by the financiaI system originates in the public sector, official IBGE figures for 1995 show that the public financiaI institutions are responsible for approximately 62.5% of alI wage eamers' remuneration in the financiaI sector.

Such data is compatible with third party evidence, obtained from studies carried out by Cysne

& Soares (1996), who show personnel expenses in relation to the eamed in come of 46.0%,

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Certainly such differences are not explained just by the differentiated sub-contracting practices.

In the specific cases of public banks, however, the major problem for Brazil does not lie in microeconomic efficiency but rather in the threat to macroeconomic stability. State govemments, knowing that the Central Bank of Brazil cannot suddenly start operating as a central bank that says no, use the state banks to tax the other states on a competitive basis. Just as in the case of the disputes over ICMS (V AT) reduction, a lack of direction in centralized coordination leads to a decrease in social security for the country as a whole. The federal govemment, on the other hand, does not act with the energy that the situation demands, given the imbalance of the federal banks. The challenge of such banks did not end with the need to adapt to a less inflationary situation. From now on, there is the further challenge of competing with intemational banks, which makes the outlook of the public financiaI institutions even gloomier.

The foregoing history of streamlining the state banks makes it clear that political streamlining agreements are generally not adopted when such institutions are under the control of the states.

Both the Lending Support Program (PAC), instituted by a vote of the National Monetary Council 233/83, of 07.20.83, specifically to solve problems of the Rio de Janeiro, Ceará, Santa Catarina, Goiás, Pará, Amazonas and Alagoas state banks, and the FinanciaI Recovery Program (PROREF) of 1984, instituted by the CMN vote 446/84 of 04.04.84, are proof of this. Such programs foresee not only adjustments in the state banks (closing branches, downsizing, reassessing the banks' asset operations, as well as changes in their capitalization by the state govemments), to offset the help they would receive from the Central Bank, but also penalties (CMN vote 232/86, of 09.04.86) for those who would not achieve the agreed goals. The results were by no means encouraging. Few of the state institutions which were involved in either the PAC or PROREF showed significant improvement. Most continued operating in a similar fashion to that which had caused their liquidity problems. The agreed requirements to close down deficit branches and recovering past due loans were simply not met. Since then, several other failed attempts by adjustment programs are part of the historical evidence that the Central Bank does not have political powers to enforce the agreements made with the states.

v .

The Capital MarketV.I. General Aspects

Cornrnents on the Brazilian FinanciaI Systern Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Commission (CVM, Law 6385176), a regulating body specifically focusing on the capital market, in order to restore the trust shaken with the 1971 crash. CVM aims explicitly to regulate, oversee and encourage development of the securities market; and c) the increase in compulsory resources through institutional investors. The govemment make it obligatory to invest in stock and debentures of part of the technical reserves of the insurance companies and pension funds; created specialized subsidiaries, managed by BNDE, in order to subscribe the private sector's stock issues and permitted intemational investment through investment companies regulated by Decree Law 1401175.

The first positive results of such measures appeared in mid-1983, when the market foresaw the end of the recessive cyc1e which had begun in 1981. The total business volume grew 103% in 1984, 113% in 1985 and 36% in 1986, in real terms, again approaching the 10% mark of the GDP which had not been achieved since 1971 (table V.l).

TABLE V.1

Volume of Business on the Stock Market (US$ million)

198 2.834 216 2.412 29 82 5.573 3

81 ?~l;~l~; ~.;~'; ;;~32,Y

.. '!4.Zl1.·.

<?i(.C, x~O, <;:>... /<13t;::;: ':;"'6.326

8 2.168 92 2.977 669 188 .6.094 3

83

,-dli

N <:, .4$;' :'.;j" ?:::~~ .·.l;~ ... ;:213;~,;:,:,s

.f)Q78 5.556 1.220 1.241 1.441 828 10.286 4

)2':666.

1,94$ ;:;~3T' ". ;4.716 1~?59 2(.917 ·::~r..

858 18.681 3.443 146 7.399 146 .29.815 9

87 {).412 " 407 51 3;;104

76'.

,10.102 388 12.789 304 4.756 213 18.067 5

89 13.966 ,'>',

212 2.083 792 17?H4' 4<.

9 4.956 81 448 95 5.581 1

91 19~OO2;: <.:'.,

ti<1

:2,199 ..ndiJ:

.7ll.31~92 18.122 nd 2.697 nd 23.753

93 'i7~10r.· ';:nd: ;l~~265. .·.· .• ·nd. '.39590

9 59.677 17.669 87.864

4:;

Note: 1995 until July.

Source: CVM Monthly Newsletter, various numbers ..

Commenls on lhe Brazilian FinanciaI Syslem

TABLE V.2 Stock Issue (US$ million)

1980 252 397 649 81'1,$7 ','33. ..>2~0

82 224 245 469

83 92 '. 1Sl 249;

84 140 390 530 85 ... :h~;;i,;}4.1f· i;s85

86 223 975 1198 87 '165, ;~i,225; 39.0<·. 88 211 318 529

89. "7262

·;:L

·4~ ... :. ..1$8 ..90 325 450 775

9({;;, 2(jtu ~~?;;{~ 60~;.:.

92 257 686 943

93 >~;".~; ;;:';;307,' ~~1 .

94 1178 1412 2590

9M447

'·7L.f574;X<2Ó21;<

40,5 1,6

42~~.;·O.7'

38,7 1,2 "'34.3 . 0;'1. .

46,1 1,2 5f;~,b;: . ·.,ti'IO .

60,7 2,0

"'~,3 :.:·.Ô;5~;

94,8 0,6

f1.UE..P;7

91,7 0,8

'ªª,O.·

,··~.O.t<95,0.1,0

97·;Q?..;;O,9

106,2 2,4

'1'1;1;,6 ·:;'UI;;;

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Sources: CVM Monthly Newsletter, Central Bank Bulletin, IBGE National Accounts, various numbers.

Between 1987 and 1991, the capital market was seriously harmed by galloping inflation and a drop in the economy's growth rate. Three new quotation crashes had the effect of keeping the small and middle investors away from the stock market for good. Between mid-1986 and late 1987, due to the disastrous Cruzado Plan, the São Paulo stock exchange (lbovespa) recorded a real drop of 83%. In June 1989, due to the excessive concentration and leverage of positions of a powerful group of investors, this rate fell 54%. In 1990, due to recession and a drastic tightening of liquidity caused by the Collor Plan, Ibovespa fell 64% in real terms.

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System

TABLE V.3

Debenture Issues (US$ million)

83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 806 ,!iJ;'9:n", 284 if,;;S:,g14 195

4.5/·

97 ,!~~ 1.75269~. 34;3 ..

299 46,1

"~~.$. ~7;8

139 60,7

';i~,::tl;, '<,~~,3>;L:

.

628 3.253

,"y"'''''''ú,:., ,,' ,: <;}~ :f:4~~;c' , ííJ:~, 94,8

110

4'll:

55

S~~ ,

916

,', 'f.qp

339

~i~;1l43 "

91,7

94 1.430 1.874 3.304

d~3i(f'·~ ;.~>;

95,0 97,tf L

106,2 95 ii 16',275*"960,::'7.235 ," 111;6 Note: 1995 until July

4,l

4,5

,<-i~l~: L;~,: 0,6 "i:O.2;] 0,2 "wt, " 3,4 1,0 1.q;. 0,4 ~(.,4,(k, 3,1

:$5 A

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Sources: CVM Monthly Newsletter, Central Bank Bulletin, IBGE National Accounts, various numbers.

After this criticaI period, the securities market recovered and had a boom apparently with new characteristics. In fact, they seem to have diminished the volatileness and cyc10thymia which were until recently their strongest characteristics. Ibovespa rose 205%, in real terms, in 1991, and 97% in 1993, but lost only 8% in 1992,3% in 1994 and 21% in 1995. The business volume on the stock market reached the record of 12.6% of the average GDP, in the 1993-94 period. Primary issues of stock, debentures and promissory notes continued the upward trend since 1992 and reached a record of around 8.3% of gross domestic savings in 1995. This was despite the slowing down in the rate of activities in the domestic economy and problems of financing on the international market.

These positive results can be related to three factors. First, the capital market was opened up to international investors, in order to acquire resources supported on strict technical analysis and taking advantage of the increased flow of capital towards the emerging economies. International investments in such a market began, as we see, in 1974 and have been released since then. By 1991 they were only permitted in collective forms - investment companies and funds - but since then, foreign individual and corporate investors have been permitted to participate (Appendix N of Central Bank Resolution 1832/91) (Faria, 1993). Secondly, the capital market has benefited from the structural reform process which had accelerated since 1990, particularly through the privatization of state-owned companies. Thirdly, there was the dramatic drop in inflation as a result of the Real Plan which is c1early a factor of price and business volume stabilization on the stock market.

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

be called upon to play a role whose economic importance cannot be doubted. This is what has been happening in the world, as can be seen in table V.4.

TABLE V.4

Stock Market Indicators of Selected Countries (US$ million)

2.399 635

,:f83à,~é./382;j .

33 348 892

:;:;1;1.19$

':;':'~61~àekx?1 Ô~1~4 ':~:>.. 5;263í:~t17;:eá];,,~!~6 48 14

4, '151" .·8/'

5 45 20

120

.Yl~5':.;) .

12

35

"8

<1Ó4< 40 !406

0 ' 2 . 9 : : 2 , '

ta.

.• <37,'1 139 44

./ji1!i.65;;i., .;~i!20

2 107 116

",,;)b ",. u:,:~· 9

-f:L"

,',,11j:1, ,';(24i?,

o

58 72':.3S.!

";·;'973:'(:·.'

";.616>':;'

Sources: IFC Emerging Markets Factbook 1993; IFSIIMFVM

=

market valueVT = transaction volume

NE = number of open companies

42

37

.',55<;:.·'

58

13 329

7;;'

2St),

.!40 290

.>136.:185

72 1()0

The capital markets of emerging countries such as Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, India, Chile, Mexico and South Africa, at a similar leveI of development as Brazil, have shown remarkable growth since the early 1980s. In 1992, the volumes negotiated on their stock markets were equal to 40%,35%, 130%, 72%, 7.1 %,5.4%, 13.4% and 7.7% of the respective GDPs and the market value of alI their open companies was 36.9%, 120%, 54.6%, 58.0%, 23.2%, 78.4%, 42.2% and 145.2% of these GDPs. Brazil was at the bottom of the list, having negotiated a volume of only 5.28% of the GDP on the basis of a market value of the open companies of 11.9%. There is, therefore, ample room for growth.

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System

V.2. Analysis of Primary and Secondary Stock Markets

Primary Stock Market

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

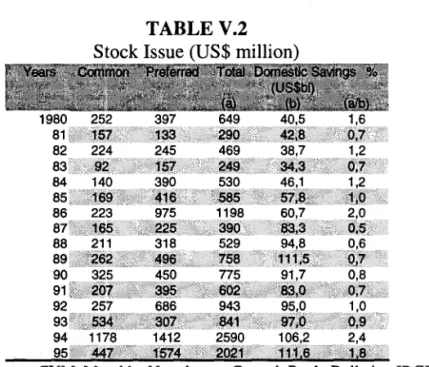

Table V.2 above shows the small scope of the primary stock market in relation to the savings requirements of the Brazilian economy. Primary stock issues as a percentage of the gross domestic savings were, on average, only 1 % between 1980 and 1994.

The lack of vitality of the primary stock market has several explanations and mention may first be of the typical Brazilian businessman's aversion to risk, expressed in the tradition of the c10sed family company, unwilling to absorb new partners into its capital. A study performed by CVM (Mendes, 1987) discovered in 1987 that Brazilian open companies were on average controlled with around 70% of the common stock in the hands of the controlling parties. This fact can be compared with what happens, for example, in the North American corporations where the voting stock is very widely scattered and it is not uncommon for the largest stock holder to have only 5% of the voting capital. Another reluctance to issuing stock is because of the way interest and dividends are taxed, which we will discuss herein below.

Secondly, on the side of the investor, there is the unequal competition of fixed income securities. In the past, they would promise to pay full restatement, which was considered an advantage in relation to the stock. Current1y, restatement no longer exists, but it is evident that real interest rates such as those we have seen since 1991, fluctuating between 15% and 25% a year, tax net, are another setback to acquiring shares.

Thirdly, there was (and still is) the problem of lack of credibility of the intermediaries which was particularly felt by the middle and small investors, usually individuaIs, as they were rarely respected (inc1uding in the matter of guaranteeing reliable execution of trading orders) by the broker houses and distributors.

Fourthly, primary stock issues have been prejudiced by the instability of the Brazilian economy.

Lastly, there is the question of the high cost of going public for the companies.

Since the early 1980s, the number of open companies has continued in a steady downward trend. They have dropped from 1,152 in 1983 to 839 in 1993 (currently they are 874). Less than 200 of them participate actively in the capital market and only 50 shares may be considered as having suitable liquidity on the stock market.

For the primary stock market to grow in size, there must be, first and foremost, a better perception of the market on behalf of the small saver. Measures to reduce the cost of going public would also be important. Other suggestions are given below.

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

The concentration of the market has increased in recent years and is expressed in various forms. First, there is the concentration of business in a few shares, in general, of state-owned companies. This was to be expected, since such companies have a low bankruptcy risk and control the markets where they operate. In 1980, the five most negotiated shares were responsible for 31 % of the total business volume; in 1994, this percentage rose to 67% (table V.5). 1980 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93,; 94

TABLE V.S

57

·:;~tl9

58 (íl; ...

55

;.~. 59 75

... ,i~64~;

63 ';19 80 1$:, 75 77

·7~';i ..

78

';\;;81 74

;1~

.'

85

~3;

84

9r" 94

':.92 .

91 Source: CNBV Annua! Report, severa! numbers.

Similarly, in 1980, of the 50 shares most negotiated on the demand market, 52% were issued by state-owned companies; in 1994, this percentage rose to 74% (table V.6).

1980 81 '.i· 82 83 84 85 86 87" 88 89 90 91 . 92 93 94 52 .~." 65

:.'

... ~ ... 51 ~6 38 48, ... 59.... 42:2' ...

49

f,74 ...

76

~1i4',' .

74 TABLE V.6 37 .J~27 25

·";42

45 45 .. 58 '.;51 405& ..

49';?~,5 " 23,4 ':i;g~ 26 11 1();" 10

... ;::,10'·;;

4

2;

4

". 1 1

2

2

fi O,5i 0,6 ·;ido

o

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

By the end of 1995, Telebrás trading represented more than 60% of the total business volume on the São Paulo Stock Exchange.

Secondly, there is also concentration at the investor leveI. Institutional investors, pension funds, in particular, namely employees of state-owned companies, hold investments in stock equal to 24% of the market value of the open companies. As a considerable portion of shares on the Brazilian market is to be found in the hands of the controlling interest (46%, on average between July/84 and Dec/85 (10)), the participation of such portfolios in the value effectively in circulation is c10se to 40%.

Thirdly, there is a concentration in the sector of financial intermediaries. Between 1980 and 1995, the number of broker houses and distributors dropped but the overall number of banks (commercial and multi pIe ) rose. In other words, it is very probable that the market is more dominated than before by bank brokers instead of independent broker companies which, in theory, would be more interested in the stock market rather than the fixed income market.

Fourthly, there is regional concentration. The number of stock exchanges has continued the same but the concentration of business in São Paulo is patently obvious. While in 1980 São Paulo Stock Exchange negotiated 48% of the Rio de Janeiro Stock Exchange, this percentage increased to 692% in 1995. The other stock exchanges are and always have been of lesser importance.

Market concentration is detrimental since, as there is a high number of poor1y marketable shares, abnormal price movements are given more potential (manipulations) and volumes (artificial marketable conditions) as well as comers and squeezes on derivative markets (control of a supply of securities on the demand market by a group of investors and the adoption of high forward positions at the buying end). These phenomena compete to reduce the competition and, therefore, the allocative efficiency of the stock market.

The lack of trust occurs for various reasons.

First, too volatile a past itself frightens off most investors, even individuaIs who are experienced in the twists and tums of the financiaI system.

Secondly, there is a tradition of the intermediaries' poor1y attending the small and middle investors. Such investors generally operate only in times of bounty but, during these booms, many intermediaries are only interested in trading large orders.

Thirdly, it is acknowledged that there is insufficient enforcement of the negotiating rules and minority stockholder rights by the self-regulating institutions (the stock exchanges) and CVM. CVM has, in fact, had difficu1ty in obliging many open companies to at least perform the minimum, that is, sending it a quarter1y report which they are obliged by law to do.

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System

The following suggestions for enforcement are a result of the above:

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

1- Improve enforcement by the CVM, both with regard to the prudential regulation and overseeing of the stock market relating to the stockholder/company relationship, particularly respecting the rights of the minority stockholder. The objective must be to create a free market, competitive and efficient. As discussed below, CVM stagnated as the market grew and became more sophisticated. There would, therefore, be a need for it to keep apace with such progresso This would in volve amendments to Law 6385/76, and training and technological upgrade programs should also be considered (involving increased computer installations), bearing in mind a better monitoring of the market.

2- Establish the right to recess in cases of a company merger, amalgamation or split, under the terms of Law 6404/76. In order to do so, it is necessary to revoke Law 7958/89 which eliminated such a right.

3- Eliminate the accounting gaps which make it easy to draw up balance sheets which do not reveal a company's real situation and make it obligatory to provide a complement of the statement and changes in its financiaI position with the cash flow.

4- Dirninish the unstabilizing legal activism of the Executive.

5- Privatization of state-owned companies. In addition to improving the management of such companies, contributing to reducing the public deficit and diminishing one of the concentration factors of the stock market, privatization could aim at broadening the stock base, which has been successful in several countries, especially England.

6- Reactivate the Capital Market Development Committee (CODIMEC). CODIMEC's experience in organizing the stock market by writing prospectuses, publishing books and periodicals and providing courses on the capital market was generally positive. Its c10sing down in 1990 was due less to any faults it might have had than to an unfavorable macroeconomic conjuncture which caused drawbacks to its financing agencies (stock exchanges, ANCOR, ABRASCA, ANBID etc., in short, the various market institutions). A new committee should set up an aggressive marketing strategy, not forgetting those individual investors who withdrew after the 1986 crash, Iinked to the collapse of the Cruzado Plano

In the case of institutionaI investors, the following measures should therefore be adopted:

First, it must be the duty of CVM or some other independent regulatory agency to be created to perform prudential regulation and the routine overseeing of all institutional investors with regard to their investments in capital market securities. It is obvious that the autarchy must have the necessary means to carry out this task efficiently.

Comments on the Brazilian Financiai System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Comments on the Brazilian FinanciaI System

Bibliographic References

Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

ALLEN, Franklin (1996); "Innovations in FinanciaI Markets: Impact on FinanciaI Intermediation". Artic1e presented at the seminar on Policy-Based Finance and Altematives for FinanciaI Market Development,

ANDIMA & IBGE, (1997) "Sistema Financeiro: Uma Análise a Partir das Contas Nacionais" (1990 1995) ANDIMA publishers, Rio de Janeiro

Banco Central do Brasil, List of FinanciaI Institutions, several editions.

Banco Central do Brasil, Annual Report, several editions.

BARRO, R. (1991), "Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries", Joumal of Political Economy Vol 82.

CVM, Monthly Newsletter, several numbers.

CYSNE, Rubens P. (1990a) "Contabilidade com Juros Reais, Déficit Público e Imposto Inflacionário" Pesquisa e Planejamento Econômico, vol 20 number 1, April 1990.

CYSNE, Rubens P. (1994) "Imposto Inflacionário e Tranferências Inflacionárias no Brasil", Ensaio Econômico EPGE nO 219, Anais do Encontro Nacional de Economia da ANPEC, Belo Horizonte, 1993 and Revista de Economia Política, vo1.l4, no. 03, July-September 1994.

CYSNE, Rubens P. & COSTA, Sérgio G. S. (1996): "Reflexos do Plano Real sobre o Sistema Bancário Brasileiro", Ensaio Econômico da EPGE no. 279, June 1996.

DE LONG, B. & L. Summers (1991) "Equipment Investment and Economic Growth", Quarterly Joumal of Economics.

EDWARDS, S. (1994) "Why are Latin America's Saving Rates so Low?" Conference on Growth in Latin America, Bogotá, Colombia.

FARIA, Lauro V. (1996) - " Análise de Mercado de Capitais Brasileiro" - Paper prepared for JKS Consultoria Associados, Mimeo.

Comments on lhe Brazilian FinanciaI System Rubens Penha Cysne Lauro Flávio Vieira de Faria

Intemational Monetary Fund, (1993) International FinanciaI Statistic Supplement, 1972, Yearbook, VoI. XL VI.

KING, Robert & Ross Levine (1993a): "Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might Be Right" Quarterly JoumaI ofEconomics 108 (August): 717-37

KING, Robert & Ross Levine, (1993b) "Finance, Entrepreneurship and Growth" paper presented at the conference: How Do National Policies Affect long Term Growth?, World Bank, Washington, D.

c.,

February.LEES, F., BOTTS, J. & CYSNE, Rubens "Banking and FinanciaI Deepening in Brazil", The Macrnillan Press Ltd., London , 1990.

MASCIANDARO, Donato & Guido Tabellini. (1988). In Hang-Sheng Cheng (editor), "Monetary Policy in Pacific Countries". Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

PAPAGEORGIOU, Demetris. (1992)"Bancos Estaduais: Experiências e Perspectivas", Banco Central, Anais do Congresso sobre Bancos Estaduais, Rio de Janeiro.

P ASTORE, Affonso Celso (1990 and 1991) ; "A Reforma Monetária do Plano Collor" p. 157-174 in Faro, Clovis (org.); Plano Collor: Avaliações e Perspectivas, Rio de Janeiro: LTC, 1990 and Revista Brasileira de Economia, VoI. 45, Special 1991 edition.

SIMONSEN, Mário H. & Cysne, Rubens P. (1989 or 1995) "Macroeconomia" Editora Ao Livro Técnico in the 1989 edition and Editora Atlas and Getulio Vargas Foundation publishers, in the 1995 edition.

SIMONSEN, Mário H. & Cysne, Rubens P. (1994) "Welfare Costs of Inflation: The Case of Interest Bearing Money and Empirical Estimates for Brazil" , Mimeo EPGE.

VITTAS, Dimitri (1996); The World Bank; "Policy-Based Finance: Applications of East Asian Lessons to the Americas". Artic1e presented at the seminar Policy-Based Finance and Altematives for FinanciaI Market Development, BNDES - Rio de Janeiro, BraziI, February.

000080774