ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Behavioural

Brain

Research

jo u r n al ho me p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / b b r

Research

report

Social

modulation

of

brain

monoamine

levels

in

zebrafish

Magda

C.

Teles

a,b,

S.

Josefin

Dahlbom

c,

Svante

Winberg

c,

Rui

F.

Oliveira

a,b,∗aISPA-InstitutoUniversitário,UnidadedeInvestigac¸ãoemEco-Etologia,RuaJardimdoTabaco34,1149-041,Lisboa,Portugal bChampalimaudNeuroscienceProgramme,InstitutoGulbenkiandeCiência,RuadaQuintaGrande6,2780-156,Oeiras,Portugal cDepartmentofNeuroscience,UppsalaUniversity,Box593,Husargatan3,75124,Uppsala,Sweden

h

i

g

h

l

i

g

h

t

s

•Zebrafishwereexposedtodifferentfightingexperiences:winning,losingandmirror-fighting.

•Winnersshowhigherserotonergicanddopaminergicactivityinthetelencephalon.

•Losersshowhigherserotonergicintheoptictectum.

•Nosignificantchangesinmonoamineactivitywereobservedinmirrorfighters.

•Monoaminesaredifferentiallyregulatedbysocialinteractionsindifferentbrainregions.

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received21May2013

Receivedinrevisedform27June2013 Accepted1July2013

Available online 11 July 2013 Keywords: Aggressivebehaviour Behaviouralplasticity Neuromodulators Serotonin Dopamine Zebrafish

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Insocialspeciesanimalstendtoadjusttheirsocialbehaviouraccordingtotheavailablesocial informa-tioninthegroup,inordertooptimizeandimprovetheironesocialstatus.Thischangingenvironment requiresforrapidandtransientbehaviouralchangesthatreliesprimarilyonbiochemicalswitchingof existingneuralnetworks.Monoaminesandneuropeptidesarethetwomajorcandidatestomediatethese changesinbrainstatesunderlyingsociallybehaviouralflexibility.Inthecurrentstudyweusedzebrafish (Daniorerio)malestostudytheeffectsofacutesocialinteractionsonrapidregionalchangesinbrain levelsofmonoamines(serotoninanddopamine).Abehaviouralparadigmunderwhichmalezebrafish consistentlyexpressfightingbehaviourwasusedtoinvestigatetheeffectsofdifferentsocialexperiences: winningtheinteraction,losingtheinteraction,orfightinganunsolvedinteraction(mirrorimage).We foundthatserotonergicactivityissignificantlyhigherinthetelencephalonofwinnersandintheoptic tectumoflosers,andnosignificantchangeswereobservedinmirrorfighterssuggestingthatserotonergic activityisdifferentiallyregulatedindifferentbrainregionsbysocialinteractions.Dopaminergicactivity itwasalsosignificantlyhigherinthetelencephalonofwinnerswhichmayberepresentativeofsocial reward.Togetherourdatasuggeststhatacutesocialinteractionselicitrapidanddifferentialchangesin serotonergicanddopaminergicactivityacrossdifferentbrainregions.

© 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Inordertooptimizethebenefitsofgrouplivingandto

min-imizeits costs,social animalsneed toadjust theexpression of

theirsocialbehaviouraccordingtodailychanges intheirsocial

environment. Thisabilityof anindividualtooptimizeits social

behaviourdependingonavailablesocial information(aka social

competence,[1]),dependsprimarilyonmechanismsthatallowfor

rapidandtransientbehaviouralchanges.Giventhespeedand

lia-bilityofthistypeofbehaviouralflexibility,suchmechanismsare

∗ Correspondingauthorat:ISPA-InstitutoUniversitário,UnidadedeInvestigac¸ão emEco-Etologia,RuaJardimdoTabaco34,1149-041,Lisboa,Portugal.

Fax:+351218860954.

E-mailaddress:ruiol@ispa.pt(R.F.Oliveira).

expectedtorelyonsociallydrivenbiochemicalswitchingof

exist-ingneuralnetworks,ratherthanonstructuralrewiringofneural

circuits[2].Inrecent yearsevidenceaccumulatedshowinghow

neuromodulatorscanchangetheactivityand even the

connec-tivity ofneuralcircuits ina waythat eachstructural circuit,as

representedbyitsconnectome,mayincludemultiplefunctional

circuits, withsomeofthem active andsome otherslatentat a

givenmomentintime[3].Differentneuromodulatoryagentsmay

interactwithspecific circuitsand alter theirfunctional

proper-ties,promotingeitherexcitatoryorinhibitorystates.Monoamines

andneuropeptidesareconsideredthetwomajorclassesof

neu-romodulators,andtheactionofbothonsocialbehaviouraswell

astheirsensitivitytoenvironmentalfactors,havebeenextensively

documented[4,5],whichmakesthemmajorcandidatesto

medi-atechangesinbrainstatesunderlyingsociallydrivenbehavioural

flexibility.

0166-4328/$–seefrontmatter © 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2013.07.012

Monoamineshavebeenimplicatedintheregulationof

moti-vatedbehaviours andamong them therole oftheserotonergic

systemonthecontrolofaggressivemotivationhasbeen

demon-strated both in vertebrate and in invertebrate species [6,7].

Interestinglytheeffectsofserotonin(5-hydroxytryptamine,5-HT)

onaggressivebehaviouraretosomeextentparadoxical.While

sev-eralstudieshavepointedoutthatpharmacologicalmanipulations

thatincrease 5-HTinhibit aggressionin a wide range of

verte-brates,fromfishtohumans[8],otherstudies,incontrast,have

showedincreasedserotonergicactivityinspecificbrain regions

duringtheexpressionofaggressivebehaviour[8–10].Moreover,

the5-HT1Aand5-HT1Breceptorsexertfunctionallyopposingroles

invariousbehaviouralandphysiologicalprocessessuchasappetite,

sexuallibido,motoractivity,andthusitisreasonabletoconsider

thatthisdivergencemayalsobepresentinaggressivebehaviour

[11–13].Therefore, therole of5-HTontheregulation of social

behaviourcannotbeputsimplyintermsofpureinhibitionorpure

facilitationofaggression,butratherasafunctionof

environmen-talcontext.Theeffects ofdopamine(DA)onaggressionarealso

paradoxical.Forexampleinmammals,whileD1andD2dopamine

receptorantagonistsreduceaggression[14],D2receptorsinthe

medialpreopticarea(mPOA)andanteriorhypothalamusfacilitate

affectivedefensebehaviour[15].On theotherhand,the

meso-corticolimbicdopaminesystemhasbeenshowntobeinvolvedin

thepreparation andexecutionofaggressiveacts[16–20].These

neurochemicalstudies linkelevated dopamineand its

metabo-litesinprefrontalcortexandnucleusaccumbensnotonlytothe

initiationofattacksandthreats,butalsotodefensiveand

submis-siveresponsesinreactionofbeingattacked[19,21].Thetransition

betweenbehaviouralstates(e.g.inhibitionorpromotionof

aggres-sivebehaviours) inboth monoaminergic systemsappearstobe

sensitivitytodifferentsocialcontexts,whichmakethese

neuro-modulatorstremendously important in the regulationof social

interactions.

The highdiversity and plasticityof social behaviour among

teleostfishmakesthemexcellentmodelsforcomparativestudies

onthemechanismsofsocialplasticity[22].Inmanyfishspecies

social systems are characterizedby reversibledominance

hier-archies, where animals have to adjust the expression of their

socialbehaviourtotheirperceived socialstatus. Inthese social

systemsrapidchangesinbehaviouraloutputoccur,drivenbythe

assessmentthattheanimaldoesofthesocialinteractionsinwhich

itisinvolved.

Inthis paperwe usedzebrafish(Danio rerio)malestostudy

theeffectsofacutesocialinteractionsonrapidregionalchanges

inbrainlevelsofmonoamines.Zebrafishwerechoseasamodel

species given their increasing use in behavioural neuroscience

researchandtheirflexiblesocialbehaviour.Zebrafishisa

group-livingspeciesthatinnatureformshoals[23]butwhenallowedto

interactinpairs,formdominancehierarchies[24].Inthisspecies

aggressioniscommonlyusedbydominantindividualstogetaccess

tospawningsitesandtoprotecttheirsocialstatusfromcompetitors

[25].Recently,ourgroupdevelopedabehaviouralparadigmunder

whichmalezebrafishconsistentlyexpressfightingbehaviourand

characterizedthestructureofthesefightsinmaledyads[26].Here

thesameparadigmisusedtoinvestigatetheeffectsofdifferent

socialexperiences(i.e.individualsexperiencingavictory,adefeat

orfightinganunsolvedinteraction)onserotoninand dopamine

levelsindifferentbrainregions.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Animalsandhousing

Allsubjectsusedinthisexperimentwereadultwild-type(AB)zebrafishbreed andheldatInstitutoGulbenkiandeCiência(IGC,Oeiras,Portugal).Fishwerekept inarecirculatingsystem(ZebraTec,93Tecniplast),at28◦Cwitha14L:10D

pho-toperiod.Watersystemwasmonitoredfornitrites(<0.2ppm),nitrates(<50ppm) andammonia(0.01–0.1ppm),whilepHandconductivityweremaintainedat7and 700Smrespectively.Fishwerefedtwiceadaywithcommercialfoodflakesinthe morningandArtemiasalinaintheafternoon,exceptonthedayoftheexperiments.

2.2. Experimentaldesign

Inthepresentstudyabehaviouralparadigmpreviouslydevelopedforthe studyofzebrafishaggressivebehaviourwasused[26].Thirty-twoadultmales (8ineachexperimentaltreatment)matchedforstandardlength(mean±SEM: 2.81±0.026cm)andbodymass(mean±SEM:0.350±0.009g)weregroupedin dyads.Therewerethreetypesofdyads:(1)realopponentfight:thefishfought withaconspecific;(2)mirrorfight:thefishfoughtwiththeirownmirrorimage; (3)nofight:thefishhadnoagonisticinteraction(Fig.1).Fromthesethreetypes ofdyads,cameoutfourexperimentalconditions:winningtheinteraction,losing theinteraction,fightinganunsolvedinteraction,orexperiencenointeraction (con-trolgroup).Subjectswerealwaystestedinpairs,inordertogivethemaccessto conspecificodours,whichwouldotherwiseonlybepresentinrealopponentdyads, thereforeavoidingconfoundingeffectsofputativechemicalcues.

Fig.1.Experimentalprocedure:(A)overnightisolationtoelicitaggression.Eachfishpairwasplacedintheexperimentaltank,andisolatedvisually,butnotchemically,by aremovableopaquePVCpartition;(B)realopponentinteraction,fishfoughtwithaconspecific;(C)mirrorinteraction,fishfoughtwiththeirownmirrorimage(greybars); (D)controlgroup,noagonisticinteractionormirrorstimulation.

Prior to the experiment,each pair was placed in the experimental tank (20cm×14.5cm×12.5cm)wheretheywerekeptovernightinvisualisolationusing aremovableopaquePVCpartition.Previousstudieshadestablishedperiodsofsocial isolationof5days[24]and24h[26]aseffectivetoelicitaggressivebehaviour. How-ever,hereweestablishedthatovernightisolationwassufficienttopromotethe consistentexpressionofaggressivebehaviour.Aftertheisolationperiod,theopaque dividerwasremovedandthefishwereallowedtointeractforaperiodof30min. Behaviouralinteractionswerevideotaped(JVC-EverioSMemory camcorder-GZ-MS215)forsubsequentbehaviouralanalysis(seebelow).

2.3. Sampling

Inordertoavoidmonoaminedegradationduringthebrainmacro-dissectionand tokeepthetimeofsamplingafterthesocialinteractionsashomogeneousaspossible acrossdyads,onlyonefishfromeachdyadwasusedformonoaminequantification. Thesefishweresacrificedimmediatelyaftertheinteractionwithanoverdoseof tricainesolution(MS222,Pharmaq;500–1000mg/L)andthespinalcordsectioned. Thebrainwasmacrodissectedunderastereoscope(Zeiss;Stemi2000)intofive areas:OlfactorybulbandTelencephalon(OB/TL),Optictectum(OT),Diencephalon (DE),Cerebellum(CB),andBrainstem(BS).Immediatelyaftercollectionthebrain tissuewasplacedondryiceandstoredat−80◦Cuntilanalysis.

2.4. Analysisofbrainmonoaminesandmetabolites

Thefrozenmacroareaswerehomogenizedin4%(w/v)ice-coldperchloricacid containing100ng/ml 3,4-dihydroxybenzylamine(DHBA,theinternalstandard) usingaSonifiercelldisruptorB-30(BransonUltrasonics,Danbury,CT,USA)and wereimmediatelyplacedondryice.Subsequently, thehomogenized samples werethawedandcentrifugedat21,000×gfor10minat4◦C.Thesupernatant

wasusedforhighperformanceliquidchromatographywithelectrochemical detec-tion(HPLC-EC),analyzingthemonoaminesdopamine(DA)andserotonin(5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine)theDAmetaboliteDOPAC(3,4-dihydroxyphenylaceticacid) andthe5-HTmetabolite5-HIAA(5-hydroxyindoleaceticacid),asdescribedby Overlietal.[10].Inbrief,theHPLC–ECsystemconsistedofasolventdeliveryas systemmodel582(ESA,Bedford,MA,USA),anautoinjectorMidastype830(Spark Holland,Emmen,theNetherlands),areversephasecolumn(Reprosil-PurC18-AQ 3m,100mm×4mmcolumn,Dr.MaischHPLCGmbH,Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany)keptat40◦CandanESA5200CoulochemIIECdetector(ESA,Bedford, MA,USA)withtwoelectrodesatreducingandoxidizingpotentialsof−40mVand +320mV.Aguardingelectrodewithapotentialof+450mVwasemployedbefore theanalyticalelectrodestooxidizeanycontaminants.Themobilephaseconsisted of75mMsodiumphosphate,1.4mMsodiumoctylsulphateand10MEDTAin deionizedwatercontaining7%acetonitrilebroughttopH3.1withphosphoricacid. Sampleswerequantifiedbycomparisonwithstandardsolutionsofknown con-centrations.TocorrectforrecoveryDHBAwasusedasaninternalstandardusing HPLCsoftwareClarityTM(DataApexLtd.,Prague,CzechRepublic).Theratiosof

5-HIAA/5-HTandDOPAC/DAwerecalculatedandusedasanindexofserotonergic anddopaminergicactivity,respectively.

Fornormalizationofbrainmonoaminelevels,brainproteinweightswere deter-minedwithBicinchoninicacidproteindetermination(Sigma–Aldrich,Sweden) accordingtothemanufacturer’sinstructions.TheassaywasreadonLabsystems multiskan352platereader(Labsystems,ThermoFisherScientific)wavelengthof 570nm.

2.5. Behaviouralobservations

Videorecordingswereanalyzedusingacomputerizedmulti-eventrecorder (ObserverXT,Noldus,Wageningen,TheNetherlands).Thezebrafishethogram[26] wasusedasareferenceandtheobservedbehavioursweredividedintoaggressive (bite,chaseandstrike)andsubmissive(freezeandflee).Aspreviouslydescribedin [26]dyadicmalefightshavetwodistinctphases:thepre-resolutionphasewhere thefightissymmetricandbothfishexhibitthesamerepertoireofbehaviours (dis-play,circle,andbite)andthepost-resolutionphasewhereallagonisticbehaviours areinitiatedbythewinnerwhereastheloseronlydisplayssubmissivebehaviours. Becausewewereonlyinterestedinthedifferentoutputofthefightswhich gener-atedifferentbehaviouralphenotypes(e.g.winnerandloser)weonlyanalyzedthe post-resolutionphase(i.e.thelast5minofthe30mininteraction).Wealso mea-suredthefightresolutiontime(timeforthesocialhierarchytobeestablished)in ordertocomparerealopponentwithmirrorinteractions.

2.6. Statisticalanalysis

StatisticalanalyseswereperformedwiththesoftwareSTATISTICAv.10 (Stat-Soft,Inc.,2011).Parametricstatisticwasusedgiventhatthevariablesmatchthe parametricparameters.Oneloserandonecontrolwereremovedfromtheanalysis, onebecausetheoutputofitsfightwasnotcompletelyclearandthesecondbecause mostofthetimeitwastrappedonthepartition,resultinginasamplesizeof7for losersandcontrolgroups,and8forwinnersandmirrorgroups.Inthebehaviour analyses,oneanimalfromthewinner,loserandmirrorgroupswasremovedfrom theanalysisduetoaproblemwiththevideorecordingswhichmadetheanalysis

impossible.AT-testwasusedtoaccessdifferencesbetweentypesofinteractions (realopponentvsmirror)andfightresolutiontime.Inthemonoaminesanalysis, foursamplesfromtheoptictectumwereexcludedduetoproblemsduringthe sam-plepreparation.Serotonin,dopaminelevelsandtherespectivemetabolites,5HIAA andDOPAC,aswellastheactivityofbothneurotransmittersasmeasuredbythe ratios5-HIAA/5-HTandDOPAC/DA,inbrainmacroareaswerelogtransformedin ordertomeettheassumptionofnormaldistribution.ArepeatedmeasuresANOVA (repeatedfactor:brainmacroareaswith5levels,independentfactor:malestatus with4levels,winner,loser,mirror,control)wasusedtoidentifythemaineffects andtheinteractionbetweenbrainareaandsocialstatusonthedifferentmonoamine measures,followedbyaposthoctestsandplannedcomparisonsofleastsquares meansbetweenthecontrolgroup(isolation)andeachofthedifferentsocialstatus. APCAanalysiswasusedtoreducethenumberofbehaviourvariablesinthereal opponentparadigm.Correlationsbetweenbehaviourandmonoamine concentra-tionswereobtainedwithPearsoncorrelationcoefficients.Alltestsweretwo-tailed andstatisticalsignificancewassetatp<0.05.

2.7. Ethicsstatement

Theanimalexperimentationproceduresusedinthisstudyfollowedthe Asso-ciation fortheStudy ofAnimal Behaviourand theAnimal BehaviourSociety guidelinesforthetreatmentofanimalsinbehaviouralresearchandteachingand wereapprovedbytheinternalEthicsCommitteeoftheGulbenkianInstituteof Sci-enceandbytheNationalVeterinaryAuthority(Direc¸ãoGeraldeAlimentac¸ãoe Veterinária,Portugal;permitnumber8954).

3. Results

3.1. Behaviour

Intherealopponentparadigmallpairsexceptone,developa

cleardominant/subordinaterelationship.Socialhierarchieswere

stableand thebehaviours exclusiveforeachphenotype. During

thepost-resolutionphase a winnernever becamea losernora

loserbecameawinner.Thebehavioursarestereotypedaccording

tosocialstatus,aggressivebehavioursinwinnersandsubmissive

Fig.2. Behaviouralresults.(A)Meannumberofaggressiveactsperformedinthe last5minofthe30minagonisticinteraction;errorbarsrepresentthestandard errorofthemean.(B)Fightresolutiontime,measuredasthetimeneededfora socialhierarchytobeestablishedinthefightingmaledyads(countingfromthefirst bitetothepost-resolutionphase);errorbarsrepresentthestandarderrorofthe mean(t-test:T=−6.39,p<0.0001).

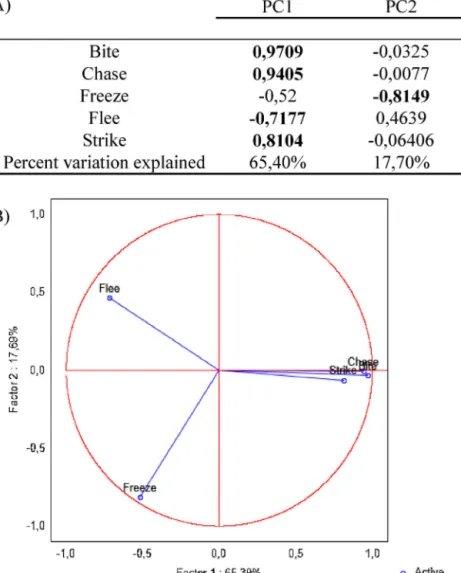

Fig.3. Principalcomponent(PC)analysisofaggressiveandsubmissivebehavioursintherealopponentparadigm.(A)Factorloadingsofthebehaviouralvariablesand varianceexplainedbyeachPC.(B)GraphicrepresentationoftheextractedPC’s:PC1representsaggressivebehaviourandPC2submissivebehaviour,whichcanbefurther dividedinactivesubmission(flee)onthepositivequadrantandpassive(freeze)onthenegativequadrant.

behaviours in losers. On theother hand,in mirror interactions

becausethefightis symmetricalong time theresulting

pheno-typeis not apparent, theynever behave likelosers orwinners,

andaggressivelevelsarekeptconstantduringthewhole

interac-tion(Fig.2).Thisdifferenceisobviousinthefightresolutiontime

(T=−6.39,p<0.0001;Fig.2B)wheremirrorfightersfightfor30min

whereas inthe realopponent interaction thefightis solved in

approximately7min,afterwhichapost-resolutionphaseis

estab-lished.

In order to reduce the number of behavioural variables in

subsequent analyses in the real opponent paradigm, a

Prin-cipal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed. Two factors,

thattogetherexplain83.1%ofthetotalvariance (Fig.3A),were

extractedthat showa clearseparation betweenaggressive and

non-aggressivebehaviours:PC1haspositiveloadingsfor

aggres-sivebehavioursandanegativeloadforsubmissivebehaviour(flee)

andexplains65.4%ofthevariation;PC2haspositiveloadingsfor

submissivebehaviourandnegativeloadingsforalltheaggressive

behaviours(bite,chase,strike) andexplains17.7% ofthe

varia-tion(Fig.3A).PC2allowsthesubsequentdivisionofsubmissive

behaviourintoanactive (flee,positive quadrant)and a passive

(freeze,negativequadrant)style(Fig.3B).Theseresultssupportthe

separationofaggressiveandsubmissivebehaviourinthereal

oppo-nentinteraction.Inthemirrorinteraction,becausethebehavioural

repertoireisrestrictedtotwobehaviours(bite,strike)noPCAwas

performed.

3.2. Brainmonoamines

Concentrationsofserotonin(5-HT),dopamine(DA) andtheir

mainmetabolites(i.e.5-HIAAandDOPAC,respectively)inthe

stud-iedbrainareasaregiveninTable1.

Therewas a treatmentand brain areamain effect for both

5-HT(repeated measuresANOVA; social treatment: F3,25=7.86,

p<0.001;brainarea:F4,100=79.39,p<0.0001,respectively)and

5-HIAA(repeated measuresANOVA;social treatment: F3,24=8.55,

p<0.001;brainarea:F4,96=50.36,p<0.0001).Theposthoc

anal-ysesrevealedthatsocialexperienceincreased5-HTand5-HIAA

levels in animals that foughtreal opponents (W/L)and mirror

imagewhencomparedtocontrolgroup.For serotonin,the

con-centrationwashigherinthediencephalon,followedbyolfactory

bulb/telencephalon,optictectumandbrainstemandthelowest

concentrationwasfoundinthecerebellum.Ontheotherhand,for

themetabolite5-HIAA,olfactorybulb/telencephalonhadthe

high-estconcentration,followedbydiencephalon,optictectum,brain

stemandfinallycerebellum.

ForDAandDOPACtherewasalsoamaineffectfortreatment

Table1

Monoamineandmetabolitesconcentrations(mean±SEM)indifferentbrainareas,anddifferenttreatments.Asterisk(*)inthemeanindicatessignificativedifferenceson specifictreatmentswhencomparedtocontrolgroup(repeatedmeasuresANOVA,*p<0.05).

Brainregion Monoaminesand metabolites

Treatment

Control Mirrorfighter Winner Loser Statistics

Telencepahlon 5-HT 3.83±1.02 6.40±0.85* 6.15±1.6 5.61±0.74 F(12,100)=2.48;p<0.01 5-HIAA 5.26±1.67 9.06±1.66* 9.98±1.64* 9.05±1.28* F(12,96)=1.17;p=0.32 DA 2.08±0.57 2.91±0.54 2.57±0.53 2.28±0.31 F(12,96)=3.11;p<0.001 DOPAC 0.46±0.16 0.78±0.20 0.68±0.08 0.54±0.11 F(12,100)=3.55;p<0.001 Diencephalon 5-HT 8.86±1.43 9.26±0.75 8.19±0.95 10.54±0.92 F(12,100)=2.48;p<0.01 5-HIAA 4.44±0.71 4.99±0.45 4.22±0.33 5.86±0.36* F(12,96)=1.17;p=0.32 DA 6.25±0.72 6.23±0.52 5.01±0.68 6.93±0.65 F(12,96)=3.11;p<0.001 DOPAC 0.53±0.08 0.67±0.06 0.52±0.04 0.83±0.09* F(12,100)=3.55;p<0.001 Optictectum 5-HT 4.19±0.34 4.11±0.36 4.04±0.22 3.55±0.28 F(12,100)=2.48;p<0.01 5-HIAA 2.37±0.25 2.11±0.39 2.69±0.26 2.87±0.26 F(12,96)=1.17;p=0.32 DA 0.92±0.07 1.13±0.17 1.01±0.06 0.83±0.08 F(12,96)=3.11;p<0.001 DOPAC 0.18±0.01 0.41±0.03* 0.28±0.02* 0.33±0.05* F(12,100)=3.55;p<0.001 Cerebellum 5-HT 0.32±0.06 1.72±0.51* 1.47±0.25* 1.08±0.26* F(12,100)=2.48;p<0.01 5-HIAA 0.92±0.49 2.17±0.60* 1.47±0.60* 1.75±0.42* F(12,96)=1.17;p=0.32 DA 0.20±0.02 1.63±0.63* 1.02±0.17* 0.72±0.17* F(12,96)=3.11;p<0.001 DOPAC 0.04±0.01 0.30±0.09* 0.15±0.04* 0.18±0.05* F(12,100)=3.55;p<0.001 Brainstem 5-HT 3.62±0.56 3.39±0.40 6.51±1.18* 4.43±1.43 F(12,100)=2.48;p<0.01 5-HIAA 2.37±0.32 2.26±0.18 3.15±0.36 3.03±0.38 F(12,96)=1.17;p=0.32 DA 2.63±0.41 2.23±0.21 4.23±0.66* 3.21±0.86 F(12,96)=3.11;p<0.001 DOPAC 0.27±0.06 0.35±0.03* 0.46±0.04* 0.41±0.08* F(12,100)=3.55;p<0.001

p<0.01)] and DOPAC levels [F3,25=8.31, p<0.001] in winners,

losers andmirrorfighters suggestingan activationofboth sys-temsinacuteinteractions.DA[F4,96=85.68,p<0.0001]distribution

acrossthebrainwasdistinct,withelevatedconcentrationsinthe diencephalon,thenolfactorybulb/telencephalonandbrainstem, andlastlyoptictectumandcerebellum.ForDOPAC[F4,100=39.09,

p<0.0001]olfactorybulb/telencephalonanddiencephalonexhibit thehighestconcentration,optictectumandbrainstemwereafter andcerebellumshowedthelowest.

Therewasa significantmain effect of brainareabut not of socialstatus intheratiosof both5-HIAA/5-HT(repeated meas-uresANOVA,brainareamaineffect:F4,88=83.38,p<0.0001;social

status main effect: F3,22=1.27, p=0.31) and DOPAC/DA (brain

area main effect: F4,68=28.53, p<0.00001; social status main

effect:F3,17=2.17, p=0.13). Theposthocanalysesrevealedthat

5-HIAA/5-HT ratios were significantly higher in the olfactory bulb/telencephalon,followedbythecerebellum,thenoptictectum andbrainstemandlastlybythediencephalon.DOPAC/DAratios weresignificantlyhigherintheoptictectum,followedbyolfactory bulb/telencephalon,thencerebellum,anddiencephalonandlastly inthebrainstem.Contrastanalysisof5-HIAA/5-HTandDOPAC/DA activityofanareabyareabasisrevealedthat5-HIAA/5-HTlevels weresignificantlyhigherinwinners’olfactorybulb/telencephalon (F=18.43, p<0.001), and losers optic tectum (F=9.92, p<0.01;

Fig.4A). Regardingthe DOPAC/DA,winners had higheractivity

levelsintheolfactorybulb/telencephalon(F=6.32,p<0.05),and

mirrorandlosersintheoptictectum(F=12.05,p<0.01andF=6.67,

p<0.05respectively;Fig.4B).Therewasalsoamarginally

non-significanttendencyforloserstohaveincreasedDOPAC/DAratios

inthecerebellum(F=3.96,p=0.06).

3.3. Relationshipbetweenmonoaminesandbehaviour

Correlationsanalysesbetweenbehaviourand monoaminein

differentbrainareasrevealedthatintherealopponentparadigm

therewerenegativecorrelationsbetween5-HIAAlevels(r=−0.70,

N=12,p<0.05)andDOPAClevelsinthediencephalon(r=−0.58,

N=13,p<0.05)andaggressivebehaviour,andbetween5HIAA/5HT

ratio in the diencephalon and submissive behaviour (r=−0.69,

N=12, p<0.05). Positive correlations were found between DA

levels in the diencephalon and submissive behaviour (r=0.60,

N=13,p<0.05)and DAlevelsin thecerebellumand aggressive

behaviour(r=0.76,N=12,p<0.01).

Inthemirrorfightingtreatmenttherewerepositive

correla-tionsbetweenbitefrequencyand5-HIAAlevelsintheoptictectum

(r=0.81,N=7,p<0.05),the5HIAA/5HTratiosinthediencephalon

(r=0.90, N=7,p<0.01)and optictectum(r=0.83,N=7,p<0.05)

andDOPAC/DAratiointhediencephalon(r=0.76,N=7,p<0.05).

Strikefrequencywasnegativelycorrelatedwith5-HTandDOPAC

Fig.4.Monoaminergicactivityindifferentbrainareasfollowinganacutesocial interaction:(A)HIAA/5-HTratio;(B)DOPAC/DAratio.Errorbarsrepresentthe standarderrorofthemean(repeatedmeasuresANOVA,*p<0.05and**p<0.01).

levelsinthecerebellum(r=−0.79,N=7,p<0.05;r=−0.79,N=7,

p<0.05)andpositivelycorrelatedintheoptictectumwithDAlevels

(r=0.77,N=7,p<0.05).Allothercorrelationswerenonsignificant.

4. Discussion

Inthecurrentstudyitisshownthatfollowinganacute

ago-nisticencounterzebrafishmalesexpresstwodistinctbehaviour

profilesdepending onthesocial status achieved: losers exhibit

exclusivelysubmissivebehaviours,whereaswinnersexpressonly

aggressivebehaviours (Fig.2A). Aftertherelative fighting

abil-ityhasbeenestablished,thedifferentbehaviouralrepertoiresfor

each social status are stable over time (at least up to5 days,

R.F.Oliveiraandco-workers,unpublisheddata).Foranimalsthat

foughttheirownmirrorimageonlyaggressivebehaviourswere

observed,withafrequencythatwasnotsignificantlydifferentfrom

thatobservedinwinnersofrealopponentfights(T-test:T=−0.84,

p=0.42).However,amajordifferencebetweenwinnersandmirror

fightersispresent,notontheirbehaviouraloutput,butratheron

thebehaviourobservedintheopponent,sinceinmirrorfightsthe

opponent(i.e.ownimageonthemirror)neverdisplayssubmissive

behaviours.Asaconsequencemirrorfightswereunsolvedfights,

ascanbedemonstratedbythefactthattheexpressionof

aggres-sivebehaviourtypicalofthepre-resolutionphaselastedforthe

wholedurationofthetrial(30min),whereasinrealopponentfights

theencounterwasresolvedinapproximately7min(afterwhich

post-resolutionbehaviouralprofileswereobserved).Therefore,the

experimentaldesignusedsuccessfullyproducedfourtypesofsocial

phenotypes:winners,losers,individualsthatexpressedaggressive

behaviourbutdidnotexperienceeitherawinoraloss(i.e.

mir-rorfighters),andindividualsthatdidnotexpressorperceivedany

socialbehaviour(control=socialisolation).Therefore,the

compar-isonofmonoaminelevelsinregionsofinterestinthebrainacross

thesefoursocialphenotypesallowstheinvestigationofthe

short-termeffectsofacutesocialinteractionsdependingonperceived

outcomebytheparticipants.

Formonoamines,we foundthat5-HTlevelsaresignificantly

higherinthetelencephalonofmirrorfighters,inthebrainstem

ofwinnersandinthecerebellumofallexperimentalgroups.The

increasein5-HTbrainlevelsinthetelencephalonandbrainstem

suggeststhatmirrorfightersandwinnersarethegroupswherethe

serotonergicsystemisfirstactivatedinresponsetoasocial

interac-tionandalthoughtheybehavesimilarly,thebrainareasactivated

aredistinctwhichmayindicatedifferentperceptionofthecontext.

Wealsofoundabrainarea(i.e.cerebellum)thatrespondstoacute

stressindependentoftheinteractionstype(i.e.anincreaseinall

groupswasseencomparedtocontrols).

For5-HTmetabolite(5-HIAA),significantincreaseswerefound

inthetelencephalonandinthecerebellumofalltreatments

(win-ner,losers, and mirrorinteraction), and in thediencephalon of

losers.Interestingly,5-HIAAlevelsinthediencephalonwere

neg-ativelycorrelatedwithaggressivebehaviourintherealopponent

paradigmsupportingthediencephalonenrolmentintheregulation

ofaggressivebehaviour.Ontheotherhand,aggressivebehaviour

(bitefrequency)waspositivelycorrelatedwith5-HIAAintheoptic

tectumformirrorfighters.Thislatercorrelationmaybeprimarily

associatedwithincreasedvisualstimulationinmirrorfighters.

Ourresultssuggestthatacuteinteractionactivated

serotoner-gicsystemincreasing5-HTand5-HIAAbrainlevelsinresponseto

differentsocialconditions.

Serotonergicactivityinturn,issignificantlyhigherinthe

tele-ncephalonofwinnersandintheoptictectumoflosers,andno

sig-nificantchangeswasobservedinmirrorfighters.Moreover,inreal

opponentfightsserotonergicactivityinthediencephalonwas

neg-ativelycorrelatedwithsubmissivebehaviourandinmirrorfights

serotonergicactivityboth in thediencephalon andin theoptic

tectumispositivelycorrelatedwithovertaggression(i.e.bites).

Giventhatsocialinteractiondidnotaffect5-HTlevelsinthesebrain

areas,5-HTactivitywasmainlydeterminedbymetabolitelevels.

Theseresultssuggestthatserotonergicactivityisdifferentially

reg-ulatedindifferentbrainregionsbysocialinteractions.Inzebrafish

threeclustersofserotonergicneuronshavebeendescribed:the

raphenuclei,theposteriortuberculum/hypothalamicpopulations

andthepretectalarea.Thetelencephalon(includingtheolfactory

bulbs)receivesprojections fromthedorsal cellsofthesuperior

raphe[27,28].Mostofthe5-HT-irfibresterminateindorsolateral

partsoftherostraltelencephalonandaminorpartcontinues

ven-trallyintotheolfactorybulb[29].Thus,theobservedincreasein

telencephalonandolfactorybulbserotonergicactivityinwinners

mayreflectanactivationofthesuperiorrapheprojectionsinthis

socialcondition.Alternativelythisincreaseintelencephalic

sero-tonergicactivitymaybedue topre-synaptic stimulationofthe

terminalareas,whichhasbeendemonstrated,bydisinhibitionof

GABAergicinterneurons,increasedglutamatergiclocalstimulation,

andglucocorticoidinfusion[30,31].

Mostof theserotonergicfibres in theoptictectum seemto

originatefromserotonergicneuronsofthepretectalcluster[29].

Pretectalnuclei,aswellastheoptictectum,havebeenimplicated

intheregulationofvisualandmotorbehaviour,multimodal

sen-soryintegration[32]andescaperesponses[33],whichmayexplain

thesignificantincreasedin subordinates orloser conditions,as

observedinthepresentstudy.Inmammals,avoidanceresponses

areobtainedfromstimulationsinaregionofthesuperior

collicu-lusthatappearstorepresenttheuppervisualfield[34].Finally,

serotonergicactivityin thediencephalonwhich mustrepresent

theactivationoftheposteriortuberculum/hypothalamic5-HT

neu-ronalpopulationswaspositivelycorrelatedwithovertaggression

(i.e.bites)inthemirrorfightsandnegativelycorrelatedwith

sub-missivebehaviourin realopponentfights,suggesting arole for

theseserotonergicpopulationsinthebalancebetweenaggressive

andsubmissivebehaviour.

Theactivationoftheserotonergicsysteminresponsetosocial

interactionshadbeenpreviouslydemonstratedforotherspecies.In

earlystagesofhierarchyformationtheserotonergicsystemappears

tobeactivatedin both dominantsand subordinates.For

exam-ple,5-HTlevelswereelevatedafter10minofsocialinteraction

inthelimbicregionsandinthelocuscoeruleusofdominantand

subordinatefightinglizardmales(inAnolis carolinensis)[35].In

rainbowtrout(Oncorhynchusmykiss)bothdominantsand

subordi-natesincreased5-HTactivityinthetelencephalonandoptictectum

3haftertheinteraction[10].Similarly,inthebicolordamselfish

(Stegastespartitus),afterachronicinteractionof5ddominantsas

wellassubordinatesshowedhigherlevelsof5-HTactivityinthe

telencephalon[36].Otherstudieshave shownthat serotonergic

activityhassimilarpatternsindominantsand subordinatesbut

thispatternseemstobetemporallyadvancedindominants[35].

Ourdatadoesnotallowsuchcomparisonsinceweonlycollectone

timepointbutwecanspeculatethatthedifferencesbetweensocial

statusinthebrainareduetoatimelinethatisactingatdifferent

speedsdependingonsocialstatus,giventhatdominantsand

sub-ordinatesexhibitalreadydifferentialpatternsof5-HTactivationa

shorttimeaftertheresolutionofthefight.

Inthedopaminergicsystemtherewasasignificantincreasein

DAlevelsinthecerebellumforallgroups,andinthebrainstemof

winners.IntherealopponentparadigmDAlevelswerepositively

correlated with aggressive behaviourin thecerebellum and in

thediencephalon withsubmissivebehaviour.For DOPAC, there

wasa significantincrease for allgroups in severalbrain areas;

optictectum,cerebellumandbrainstemandinthediencephalon

oflosers.We alsofoundanegativecorrelationofDOPACinthe

thecontributionofdiencephalonintheregulationofsubmissive

behaviour. For mirror fighters DOPAC levels in the cerebellum

werepositivelycorrelatedwithstrikes.

On the other hand, dopaminergic activity was significantly

higherinthetelencephalonofwinnersandintheoptictectumof

bothlosersandmirrorfightersandtheseincreasesweremainly

determinedbythemetabolitelevels.Moreover,theexpressionof

aggressivebehaviourwaspositivelycorrelatedwithdopaminergic

activityinthediencephaloninmirrorfights.Togethertheseresults

suggestaninvolvementofthediencephalicmonoaminergic

sys-temintheregulationofaggressiveandsubmissivebehavioursin

differentsocialconditions.Thishypothesisisfurthersupportedby

theknownroleofdifferentdiencephalicnucleiintheregulation

ofspecies-specificbehavioursacrossvertebrates.Forexample,in

thebluegillfish(Lepomismacrochirus)stimulationofthe

preop-ticregioninhibitsaggressivebehavioursandevokecourtship,and

stimulationofaregionsurroundingthelateralrecesselicits

aggres-sivebehaviourandfeeding[37].Similarly,ingoldenhamstersand

rats,theanteriorhypothalamus[38]andthenucleusaccumbens

[16]respectively,havebeenimplicatedintheregulationof

aggres-sivebehaviours,andinSyrianhamsters(Mesocricetusauratus)the

nucleusaccumbensisinvolvedinconditioneddefeat[39].

Dopaminereleaseappeartobeaffectedalsoinotherbrainareas,

asthecerebellumandbrainstem,buttherewerenosignificant

dif-ferencesinDOPAC/DAratiossinceboththeneurotransmitterand

themetabolitelevelsincreasedinparallelindicatinganincreasein

monoaminergicactivity.

Theincreaseddopaminergicactivityinthetelencephalonwhen

males successfully achieve dominant status (i.e. winners) may

be representative of social reward. A similar pattern hasbeen

previously observed in salmonids where dominant individuals

showedhigherDAactivityintelencephalonthansubordinatefish

[40].However,incontrasttoamniotes,wherethedopaminergic

mesolimbicrewardsystemislocatedintheventraltegmentalarea

(VTA),thatprojectrostrallytothenucleusaccumbens,amygdala

andcorticalareas(e.g.prefrontalcortexinmammals),fishdonot

presentamidbraindopaminergicpopulationhomologoustothe

VTA [41].In contrasts,in fishtheDA inputstothe

telencepha-lonoriginateina localsubpallial DAsystemandinDAneurons

intheventraldiencephalon,inparticularintheposterior

tuber-culum,that projecttowardsthe subpallium[42–44]. Therefore,

althoughevolutionaryitcannotbeconsideredashomologousto

themammalianVTADAneurons,infishthisascendingDApathway

maybeplayingasimilarroleinrewardbehaviourasthe

mam-malianmesostriatalDApathway.Ontheotherhand,theincreased

DAactivityobservedinlosersandmirrorfightersmustbea

con-sequenceofthedifferentialactivationofanotherDAsubsystem.

ApretectalDAcellgroup(alarplateofp1)isconsistentlyfound

inbonyfishes,amphibians,andmostamniotesexceptmammals

[41].Thesepretectalneuronsareprojectingmostlyontheoptic

tectum,inalayer-specificfashionandtheymayplayaroleinthe

modulationoftheretino-tectalvisualinput[45].Inthisregardit

isextremelyinterestingtonotethatthesimilaroptictetctumDA

activationinmirrorfightersandlosers,despitethedissimilarities

oftheirbehaviouralprofile(i.e.mirrorfightersareasaggressiveas

winners,andlosersincontrast,aresubmissive),suggeststhatwhat

isdrivingtheDAactivationinthisregionistheperceptionofthe

interaction,whichissimilarinmirrorfightersandlosers(i.e.both

areexposedtoanaggressiveopponent),ratherthatthebehavioural

outputofthefocalindividual.

Insummarythedatapresentedhereconfirmsthatacutesocial

interactions elicit rapid and differential changes in

serotoner-gic and dopaminergic activity across differentbrain regions in

zebrafish. Further studies are needed to elucidate the specific

rolesof differentneuromodulatorysubsystemin theregulation

ofsocialbehaviour.Finally,theabilityofzebrafishreportedhere

torespondtoexperimentalmanipulationsofits social

environ-ment,combinedwiththefactthatitisaspecies thatexpresses

both gregarious (shoaling) andterritorial behaviour,makesit a

promisingmodelorganisminsocialneuroscience.Incomparison

tootherestablishedmodelsinthisfield,suchascichlidfish(e.g.

Astatotilapiaburtoni[46]),zebrafishhastheaddedvalueofhaving

alargegenetictoolboxavailablethatcanbeusedtogenetically

dissectthemechanismsinvolvedinsocialdecision-making.

Acknowledgements

ThisstudywasfundedbythePortugueseFoundationforScience

and Technology (FCT, grants PTDC/PSI/71811/2006 and

PEst-OE/MAR/UI0331/2011toRFO).DuringthisstudyMTwasbeing

sup-portedbyaPh.D.studentfellowshipbyFCT(SFRH/BD/44848/2008).

Wethanktothetwoanonymousrefereeswhocontributedtothe

improvementofthefinalmanuscript.

References

[1]TaborskyB,OliveiraRF.Socialcompetence:anevolutionaryapproach.Trends EcolEvol2012;27:679–88.

[2]ZupancGKH,LamprechtJ.Towardsacellularunderstandingofmotivation: structuralreorganizationandbiochemicalswitchingaskeymechanismsof behavioralplasticity.Ethology2000;46:467–77.

[3]BargmannCI.Beyondtheconnectome:howneuromodulatorsshapeneural circuits.Bioessays2012;34:458–65.

[4]LibersatF,PflugerHJ.Monoaminesandtheorchestrationofbehavior. Bio-science2004;54:17–25.

[5]Goodson JL, Thompson RR. Nonapeptide mechanisms of social cogni-tion, behavior and species-specific social systems. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2010;20:784–94.

[6]KravitzEA.Serotoninandaggression:insightsgainedfromalobstermodel systemandspeculationsontheroleofamineneuronsinacomplexbehavior. JCompPhysiolA2000;186:221–38.

[7]HuberR.Aminesandmotivatedbehaviors:asimplersystemsapproachto com-plexbehavioralphenomena.JCompPhysiolANeuroetholSensNeuralBehav Physiol2005;191:231–9.

[8]SummersCH,KorzanWJ,LukkesJL,WattMJ,ForsterGL,OverliO,etal.Does serotonininfluenceaggression?Comparingregionalactivitybeforeandduring socialinteraction.PhysiolBiochemZool2005;78:679–94.

[9]WinbergS,NilssonGE.Rolesofbrainmonoaminesneurotrannsmittersin agonisticbehaviour andstressreactions,withparticularreference tofish. CompBiochemphysiol1993;106:597–614.

[10]OverliO,HarrisCA,WinbergS.Short-termeffectsoffightsforsocial domi-nanceandtheestablishmentofdominant-subordinaterelationshipsonbrain monoaminesandcortisolinrainbowtrout.BrainBehavEvol1999;54:263–75. [11]OlivierB.Serotoninandaggression.AnnNYAcadSci2004;1036:382–92. [12]DulawaSC,GrossC,StarkKL,HenR,GeyerMA.Knockoutmicerevealopposite

rolesforserotonin1Aand1Breceptorsinprepulseinhibition. Neuropsy-chopharmacology2000;22:650–9.

[13]JenckF,BroekkampCL,VanDelftAM.Effectsofserotoninreceptorantagonists onPAGstimulationinducedaversion:differentcontributionsof5HT1,5HT2 and5HT3receptors.Psychopharmacology(Berl)1989;97:489–95.

[14]SanchezC,ArntJ,HyttelJ,MoltzenEK.Theroleofserotonergicmechanismsin inhibitionofisolation-inducedaggressioninmalemice.Psychopharmacology (Berl)1993;110:53–9.

[15]SweidanS,EdingerH,SiegelA.D2dopaminereceptor-mediatedmechanismsin themedialpreoptic-anteriorhypothalamusregulateeffectivedefensebehavior inthecat.BrainRes1991;549:127–37.

[16]VanErpAM,MiczekKA.Aggressivebehavior,increasedaccumbaldopamine, anddecreasedcorticalserotonininrats.JNeurosci2000;20:9320–5. [17]FerrariPF,vanErpAM,TornatzkyW,MiczekKA.Accumbaldopamineand

serotonininanticipationofthenextaggressiveepisodeinrats.EurJNeurosci 2003;17:371–8.

[18]MosJ,VanValkenburgCF.Specificeffectonsocialstessandaggressionon regionaldopaminemetabolisminratbrain.NeurosciLett1979;15:325–7. [19]Puglisi-Allegra S, Cabib S. Effects of defeat experiences on dopamine

metabolism in different brain areas of the mouse. Aggress Behav 1990;16:271–84.

[20]LouilotA,LeMoalM,SimonH.Differentialreactivityofdopaminergicneurons inthenucleusaccumbensinresponsetodifferentbehavioralsituations.An invivovoltammetricstudyinfreemovingrats.BrainRes1986;397:395–400. [21]TideyJW,MiczekKA.Socialdefeatstressselectivelyaltersmesocorticolimbic

dopaminerelease:aninvivomicrodialysisstudy.BrainRes1996;721:140–9. [22]OliveiraRF.Socialplasticityinfish:integratingmechanismsandfunction.JFish

Biol2012;81:2127–50.

[23]SpenceR,SmithC.Maleterritorialitymediatesdensityandsexratioeffectson ovipositioninthezebrafish,Daniorerio.AnimBehav2005;69:1317–23.

[24]LarsonET,O‘MalleyDM,MelloniJrRH.Aggressionandvasotocinare associ-atedwithdominant–subordinaterelationshipsinzebrafish.BehavBrainRes 2006;167:94–102.

[25]PaullGC,FilbyAL,GiddinsHG,CoeTS,HamiltonPB,TylerCR.Dominance hierar-chiesinzebrafish(Daniorerio)andtheirrelationshipwithreproductivesuccess. Zebrafish2010;7:109–17.

[26]OliveiraRF,SilvaJF,SimoesJM.Fightingzebrafish:characterizationof aggres-sivebehaviorandwinner–losereffects.Zebrafish2011;8:73–81.

[27]LillesaarC,TannhauserB,StigloherC,KremmerE,Bally-CuifL.Theserotonergic phenotypeisacquiredbyconverginggeneticmechanismswithinthezebrafish centralnervoussystem.DevDyn2007;236:1072–84.

[28]LillesaarC,StigloherC,TannhauserB,WullimannMF,Bally-CuifL.Axonal pro-jectionsoriginatingfromrapheserotonergicneuronsinthedevelopingand adultzebrafish,Daniorerio,usingtransgenicstovisualizeraphe-specificpet1 expression.JCompNeurol2009;512:158–82.

[29]KaslinJ,PanulaP.Comparativeanatomyofthehistaminergicandother amin-ergicsystemsinzebrafish(Daniorerio).JCompNeurol2001;440:342–77. [30]SummersTR,MatterJM,McKayJM,RonanPJ,LarsonET,RennerKJ,etal.Rapid

glucocorticoidstimulationandGABAergicinhibitionofhippocampal seroto-nergicresponse:invivodialysisinthelizardAnoliscarolinensis.HormBehav 2003;43:245–53.

[31]BarrJL,ForsterGL.Serotonergicneurotransmissionintheventralhippocampus isenhancedbycorticosteroneandalteredbychronicamphetaminetreatment. Neuroscience2011;182:105–14.

[32]Bally-CuifL,VernierP.Organizationandphysiologyofthezebrafishnervous system.In:PerrySF,EkkerM,FarrellAP,BraunerCJ,editors.Zebrafish. Amster-dam:Elsevier;2010.

[33]HerreroL,RodriguezF,SalasC,TorresB.Tailandeyemovementsevoked byelectricalmicrostimulationoftheoptictectumingoldfish.ExpBrainRes 1998;120:291–305.

[34]SahibzadaN,DeanP,RedgraveP.Movementsresemblingorientationor avoid-ance elicitedby electricalstimulationofthesuperiorcolliculus inrats.J Neurosci1986;6:723–33.

[35]SummersCH,SummersTR,MooreMC,KorzanWJ,WoodleySK,RonanPJ,etal. Temporalpatternsoflimbicmonoamineandplasmacorticosteroneresponse duringsocialstress.Neuroscience2003;116:553–63.

[36]WinbergS,MyrbergJrAA, NilssonGE.Agonisticinteractionsaffectbrain serotonergic activity inan acanthopterygiianfish: thebicolor damselfish (Pomacentruspartitus).BrainBehavEvol1996;48:213–20.

[37]Demski LS, Knigge KM. The telencephalon and hypothalamus of the bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus): evokedfeeding, aggressive and reproduc-tivebehaviorwithrepresentativefrontalsections.JCompNeurol1971;143: 1–16.

[38]CraigFF,MelloniJrRH,KoppelG,PerryKW,FullerRW,DelvilleY. Vaso-pressin/serotonininteractionsintheanteriorhypothalamuscontrolaggressive behavioringoldenhamsters.JNeurosci1997;17:4331–40.

[39]Luckett C, Norvelle A, Huhman K. The role of the nucleus accumbens in theacquisitionandexpressionofconditioneddefeat.BehavBrainRes 2012;227:208–14.

[40]WinbergS,NilssonGE,OlsenKH.Socialrankandbrainlevelsofmonoamines andmonoaminemetabolitesinArcticcbarr,SMvelinusMpinus(L.).JComp PhysiolA1991:241–6.

[41]SmeetsWJ,GonzalezA.Catecholaminesystemsinthebrainofvertebrates: newperspectivesthroughacomparativeapproach.BrainResBrainResRev 2000;33:308–79.

[42]Rink E, Wullimann MF. The teleostean (zebrafish) dopaminergic system ascendingtothesubpallium(striatum)islocatedinthebasaldiencephalon (Posteriortuberculum).BrainRes2001;889:316–30.

[43]RinkE,WullimannMF.Developmentofthecatecholaminergicsysteminthe earlyzebrafishbrain:animmunohistochemicalstudy.BrainResDevBrainRes 2002;137:89–100.

[44]TayTL,RonnebergerO,RyuS,NitschkeR,DrieverW.Comprehensive cat-echolaminergic projectome analysis reveals single-neuron integration of zebrafish ascendinganddescendingdopaminergic systems. NatCommun 2011;2:171.

[45]Smeets WJ, Reiner A. Catecholamines in the CNS of vertebrates: cur-rent conceptsof evolutionand functional significance. In:Smeets WJAJ, Reiner A,editors. Phylogenyand developmentofcatecholaminesystems in theCNSofvertebrates. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress; 1994. p.463–81.