Escola de Economia e Gestão

Karolina Magdalena Ryniak

The Europeanization of Polish and Portuguese Foreign and Security Policies: A Comparative Perspective

Dissertação de Mestrado

Mestrado em Relações Internacionais

Trabalho realizado sob a orientação de:

Professora Doutora Alena Vysotskaya Guedes Vieira

Professora Doutora Laura Cristina Ferreira-Pereira

DECLARAÇÃO

NOME: Karolina Magdalena Ryniak

ENDEREÇO ELETRÓNICO: karolina.ryniak@gmail.com TELEFONE: +351939537099

NÚMERO DO PASSAPORTE: ARS196074

TÍTULO DA DISSERTAÇÃO: The Europeanization of Polish and Portuguese Foreign and

Security Policies: A Comparative Perspective

ORIENTADORES: Professora Doutora Alena Vysotkaya Guedes Vieira

Professora Doutora Laura Cristina Ferreira-Pereira

ANO DE CONCLUSÃO: 2017

DESIGNAÇÃO DO MESTRADO: Mestrado em Relações Internacionais

1. É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA TESE/TRABALHO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE;

2. É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO PARCIAL DESTA TESE/TRABALHO (indicar, caso tal sejanecessário, nr máximo de páginas, ilustrações, gráficos, etc.), APENAS PARA EFEITOS DEINVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE;

3. DE ACORDO COM A LEGISLAÇÃO EM VIGOR, NÃO É PERMITIDA A REPRODUÇÃO DE QUALQUER PARTE DESTA TESE/TRABALHO

Universidade do Minho, __/__/____

ii Acknowledgments

I would love to express my sincere gratitude to all those people who supported and inspired me in writing this thesis.

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors: Prof. Alena Vieira and Prof. Laura Ferreira-Pereira for their beneficial comments, remarks and engagement through the investigation work at every stage of the thesis. Their guidance was significant to me during the writing process, especially their expertise, commitment and patience.

My obrigada goes to all of the teachers that I met at Universidade do Minho for their support and help during my academic subjects.

I would like to thank all of my friends that I met during my stay in Porto who made this place unforgettable and always supported me in tough moments. My special thanks goes to Maria Luisa- one of the most inspiring ‘teachers’ I have ever met.

My big thank you goes to my sisters and best friends at the same time: Gosia, Anka, Kasia and Aga for their unlimited support, friendship and love. I am the luckiest person to have you all.

My greatest dziękuję goes to my Parents for the enormous support during my whole life and showing me what love and being loved mean. No word can express my feelings and gratitude toward you.

The last, but not the least, my biggest MERCI goes to the love and light of my life Pouya, the familiar stranger who changed my life. For his unconditional love, never stopping to believe in me and keeping a sense of humor when I had lost mine. I would never stop saying ‘thank you’ for the things you have done for me. !مراد تتسود

iii The Europeanization of Polish and Portuguese Foreign and Security Policies:

A Comparative Perspective Abstract

This thesis aims to compare the process of Europeanization of Portuguese and Polish foreign and security policies. The theoretical framework of this study is formed by the Europeanization approach, in order to explore the dynamic processes of foreign and security policy change. Against the background of the reviewed Europeanization concept, with a particular focus on Portugal and Poland, the thesis explores the similarities and differences between both countries in order to understand the impact of their historical backgrounds and time of accession on their individual process of Europeanization. The comparison provides a perspective highlighting the impact of democratization at this stage. The Europeanization process is also analyzed while being divided into two main phases: ‘downloading’ (adaptation of the EU rules and norms) and ‘uploading’ (projection of their national preferences into the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) level). For Portugal, the ‘downloading’ stage explores the domestic adaptation and institutional changes and the ‘uploading’ phases reviews the three rotation Council Presidencies. In the case of Poland, the EU´s influence on national administrative structures during the ‘downloading’ process and promoting of the Eastern Dimension during the ‘uploading’ phase are studied. After this, the Europeanization process of both countries is compared by taking into account the different characteristics and spheres of interest, the challenges they faced, and the role of NATO in their foreign and security policies. The results of the comparison demonstrate that despite numerous differences, distinct ways of ‘uploading’ and national preferences, the Europeanization could be attained for both of them. Moreover, the analysis demonstrates that a proper uploading can only be obtained through an effective downloading process. Finally, the dissertation concludes that the projecting of national interests (vis-á-vis Ukraine in case of Poland and towards the Lusophone world for Portugal) had been achieved in full compatibility and faithfulness to NATO.

iv A Europeização das Políticas Externas e de Segurança de Portugal e da Polónia:

Uma Perspectiva Comparativa Resumo

Esta tese tem como objetivo estabelecer a comparação entre a Europeização das políticas externas e de segurança de Portugal e da Polónia. O contexto teórico deste estudo tem como base o fenómeno da Europeização de forma a explorar os processos dinâmicos de mudança nas políticas externas e de segurança. Esta tese tem início com a apresentação de uma revisão do conceito de Europeização com especial foco em Portugal e Polónia. Posteriormente, as similitudes e diferenças entre os dois países são estudadas de forma a interpretar o impato dos respetivos antecedentes históricos e datas de adesão na adaptação ao processo de Europeização. O estabelecimento desta comparação permite aos leitores compreender o impato da democratização nesta etapa. Em seguida, o processo de Europeização é dividido em duas etapas principais: a fase de ’downloading’ (adaptação às normas e leis da União Europeia) e de ’uploading’ (projecção das preferências nacionais no domínio da Política Externa e de Segurança Comum. Para Portugal, na fase ’downloading’ explora-se a adaptação doméstica e mudanças institucionais enquanto que na fase de ‘uploading’ revê-se o trio de Presidências rotativas do Conselho. No caso da Polónia, a influência da EU nas estruturas administrativas nacionais e a promoção da Eastern Dimension são estudadas durante as fases ‘downloading’ e ’uploading’, respetivamente. Em seguida, o processo de Europeização dos dois países é então comparado, tendo em consideração as características diferenciais e áreas de interesse, os desafios que enfrentaram e o papel da NATO nas suas políticas externas e de segurança. Os resultados deste estudo comparativo demonstraram que, apesar de existirem numerosas diferenças entre os dois países, distintas formas de ‘uploading’ e de preferências nacionais, a Europeização foi ser alcançada para ambos os países. Adicionalmente, foi também demonstrado que um ‘uploading’ adequado só poderá ser alcançado através de um processo de ‘downloading’ efectivo. Conclui-se também que a projecção dos interesses nacionais (relacionados com a Ucrânia, no caso da Polónia e com a Comunidade Lusófona para Portugal) foi alcançada com total compatibilidade e fidelidade à NATO.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

1. Introduction ... 10

1.1. The state of the art ... 13

1.2. Theoretical framework ... 24

1.3. Research design ... 27

1.3.1. Research problem ... 27

1.3.2. Research question ... 27

1.3.3. Research methods ... 28

1.4. Structure of the dissertation... 29

2. The Foreign and Security policies of Portugal and Poland: The Impact of Democratization .. 32

2.1 Introduction ... 32

2.2 Collapse of the non-democratic regimes and reorientation of foreign policy goals ... 33

2.3 Security and Atlanticism: Role of NATO and relations with USA ... 36

2.4 Membership to the European Union ... 39

3. Portuguese Foreign and Security Policies after EU’s accession: Examining ‘Uploading’ and ‘Downloading’ ... 42

3.1. Introduction ... 42

3.2. Domestic adaptation and institutional changes ... 43

3.3. Portugal and the development of the CFSP/ESDP: From Atlanticism to Europeanism .... 47

3.4. Uploading national policies to the EU’s agenda: Rotation Council Presidencies ... 51

3.4.1. The first Presidency 1992: ‘Learning by doing’ ... 52

3.4.2. The second Presidency, 2000: ‘at the core of the integration process’ ... 55

3.4.3. The third Presidency, 2007: ‘Stronger Europe for a better world’ ... 57

3.5. Playing the Lusophone card ... 59

3.6. Portugal and the ESDP missions ... 63

3.7. Conclusions ... 66

4. Polish Foreign and Security Policy within the EU ... 69

4.1. Introduction ... 69

4.2. Domestic dynamics after the EU enlargement ... 69

vi

4.4. Special alliances: Weimar and Visegrad Group ... 77

4.5. Poland as an Eastern agenda shaper ... 78

4.6. Projection of the Eastern Dimension to the EU: 2003-2009 ... 82

4.7. Polish contribution to the CFSP ... 89

4.8. From skepticism to pragmatism: Polish approach toward ESDP ... 94

4.9. Conclusions ... 95

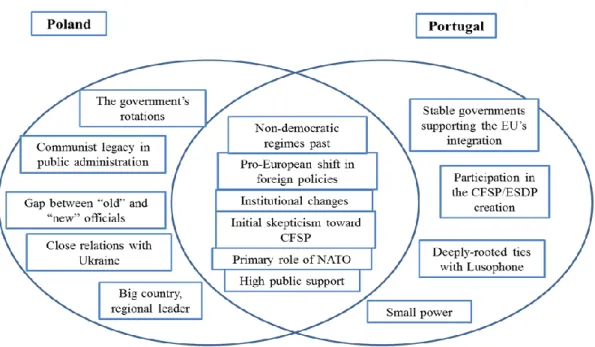

5. Portuguese and Polish Foreign and Security Policies: A Comparative Analysis ... 97

5.1 Introduction ... 97

5.2. Changes in foreign and security policies orientation ... 98

5.3. Concerns related to joining the CFSP/ESDP ... 99

5.4. National adaptation and domestic changes ... 100

5.5. Introducing national interests and preferences ... 103

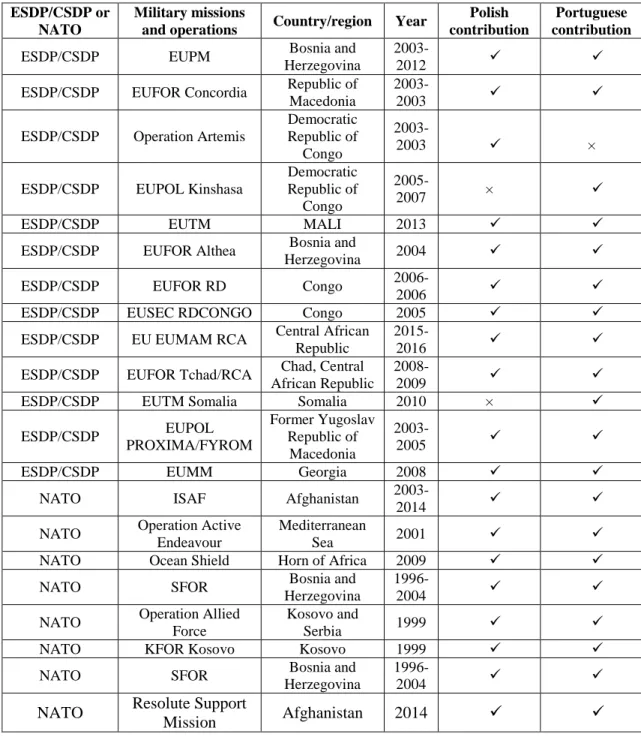

5.6. Contribution to the CSDP and NATO missions and operations ... 105

5.7. Conclusions ... 106

6. Conclusions ... 108

6.1 Main findings ... 108

vii List of Abbreviations

AAs- Associations Agreements

ACP- African Caribbean and Pacific

CEE- Central and Eastern Europe

CEECs- Central and Eastern European Countries

CFSP- Common Foreign and Security Policy

CICE- Interministerial Commission for the European Communities

COMECON- Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

CPLP- Community of Portuguese Language Countries

CSDP- Common Security and Defense Policy

DCFTA- Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area

DGAC- General-Directorate of European Communities

EaP- Eastern Partnership

EC- European Community

EEAS- European External Action Service

EEC- European Economic Community

EED- European Endowment of Democracy

EFTA- European Free Trade Association

ENP- European Neighborhood Policy

EPC- European Political Cooperation

ESDP- European Security and Defence Policy

EU- European Union

viii

KERM- European Committee of the Council of Ministers

KIE- Committee for European Integration

MES- Ukraine Market Economy Status

MES- Ukraine Market Economy Status

MFA- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

NATO- The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

PCP- Partido Comunista Português

PREC- Processo Revolucionario em Curso

PREC- Processo Revolucionario em Curso

SEA- Single European Act

UKIE- Office for the European Integration

UN- United Nations

US- United States of America

USSR- Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

ix List of Figures

Figure 1. Europeanization model based on Miskimmon (2003) ... 24 Figure 2. Similarities and differences between Poland and Portugal in the Europeanization

process... 107 Figure 3. Comparison of Poland and Portugal positions at the initial phase of the EC/EU

accession ... 110 Figure 4. Comparison of Poland and Portugal in uploading their national preferences to the CFSP/CSDP ... 111

List of Tables

Table 1. Model of Europeanization process Kaminska (2007) ... 25 Table 2. Participation of Poland and Portugal in the military missions and operation of the

10

1. INTRODUCTION

Europeanization has attracted attention of many International Relations scholars. In this area, different European Union (EU) member states’ policies, positions, and processes have been investigated from various points of view, and in different areas (Ladrech, 1994; Kassim, 2000; Bulmer and Burch, 2001; Risse et al 2001; Olsen, 2002; Dyson and Goetz, 2002; Börzel 2002; Featherstone, 2003; Miskimmon, 2007). While there is no doubt that there have been numerous changes in both internal and external policies of the states that have been chosen for analysis i.e. Portugal and Poland, these variations have been often considered case-specific, depending on the particular country in question (Schmidt, 1997; Börzel, 1999; Bache, 2005). The change of the nature of the selected countries for this study, from non-members states to becoming a part of the EU, has been associated with different complications and obstacles. In this connection, the foreign policy has been considered as a special case for representing a challenging area due to the strong intergovernmental character of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Similar to CFSP, the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) has been also debated in the context of Europeanization approach, applied to various states. Studying the mechanisms of Europeanization would need comprehensive understanding of the national security and defence policies. This includes, in particular, the role of NATO and its relationship with the EU, in the context of the Europeanization research stream. A closer attention to the Europeanization of the national foreign and security policies from this perspective seems crucial for identifying the individual character of foreign and security policies of the member states. Against this background, the focus of this research is the interdependence between the national level and the EU level in the fields of foreign, security policies, as well as the degree to which the actors are adapting themselves to the evolution of the CFSP/CSDP and how they have been trying to impact on these policies.

More concretely, this present project aims to investigate the process of Europeanization of Polish and Portuguese foreign and security policies in a comparative perspective. The selection of these two countries as case studies is firstly based on various common features that served as the basis of the comparative analysis that the present dissertation will offer. The first one is their geographical location on the fringes of the EU, i.e., on the EU’s Western and Eastern borders.

11

The second one is their Atlanticism, as reflected in their strong commitment to NATO’s activities and interests. Another common aspect is that for both Poland and Portugal, besides the ‘European option’, the centrality of NATO has always been their foreign and security policy priority. Despite the different types of regimes in Poland and Portugal, one can identify similarities in the process of transition of their foreign policies following the regime change. The democratization process that took place between 1970s and 1980s in Portugal and in 1990s-2000s in Poland, led to the foundation of the Western model of democracy. Polish accession to the NATO and EU were treated as complementary means to accomplish the security in Central Europe, an issue of special importance to Poland, given its geopolitical position and the direct proximity to Russia and Germany. Poland saw an urgent need to integrate into Western structures, notably NATO, with the aim of obtaining the hard security guarantees that could secure its position in the region which can be considered falling into a ‘grey zone of security’. In spite of different historical background and variation in terms of their size, as well as different timing regarding the EU accession, Portugal and Poland have been facing various similar challenges since their accession, which included the deepening of CFSP and CSDP against the background of their Europeanization processes. While both countries were skeptical of CFSP at the beginning, both eventually adapted well to it and came to use it as a way to fulfill their interests and increase their influence inside the EU. This is to say, Portugal and Poland have clearly managed to master the uploading of their national interests and preferences to the EU level. In this connection, the present study also investigates to what extent there is a similarity between the two countries in terms of ‘uploading’ of their specific security and defense-related concerns within the European foreign and security policy.

In order to fully understand the process of Europeanization of foreign and security policies, this research aims to study both the bottom-up and the top-down dimensions of Europeanization. Both of these dimensions will be analyzed separately; however, the main focus will be the national projection in order to see how the both countries have been able to upload their national preferences to the EU level and shape the agenda of the CFSP/CSDP. Nonetheless,

12

it is important to note that this comparative study does not take into consideration the cross-loading approach of Europeanization.1

The most prominent example of the uploading of the Polish goals on the European level was the promotion of the Eastern Dimension initiative of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), in 2007, which proved Poland to be a successful agenda-setter in EU’s policy toward countries like Ukraine, Georgia, and Belarus, and a bridge-builder between East and West. In this position, Poland has strengthened the EU efforts to support democratization of Ukraine, while acting as Kiev’s ‘older brother’. Portuguese ‘return to Europe’ in 1986, which was preceded by a long negotiation process, eventually indicated the process of pro-European reorientation in its foreign and security policies. Acting as a ‘good student in the Community classroom’, (Vasconcelos, 2000), Portugal has actively contributed to shape the EU external agenda in order to avoid its marginalization as a peripheral country and a small state power. Since the establishment of CFSP, Portugal has been an important and active player, while placing special emphasis on the strategic cooperation with the EU, NATO, and the United States. Portuguese government, too, has been successful in uploading its national foreign policy interest into the European level. Portugal’s three Presidencies of the Council of the European Union (1992, 2000 and 2007) were significant in shaping the CFPS, and have promoted an upgrade of EU´s relations with the Lusophone world. For example, the first and second EU–Africa summits and the first EU–Brazil summit, organized during Portuguese EU Presidencies of the Council are cases in point. One of the most significant achievements, however, took place during the third Presidency, which was held under the motto ‘A Stronger Europe for a Better World’. During the third Presidency term, the Lisbon Treaty was successfully concluded and signed, without any doubts contributing to a boost of the country’s strategic status, not only in Europe but also worldwide (Ferreira-Pereira, 2007, 2008). As the country became a more visible player in foreign affairs, it was easier to project its national foreign policy goals at the European level and also including the Lusophone world. The three Portuguese EU Council Presidencies provided an opportunity to shape the EU foreign policy agenda, notably to strengthen Europe’s dialogue with Latin America and Africa.

1Quite recently, considerable attention has been paid to the cross-loading approach as a further dimension of Europeanization. Some authors such as (Lenschow, 2006) argued, that Europeanization should not be seen only as a top-down and bottom-up vertical process but also as the horizontal one where the policies and concepts are transferred among states and the EU. Moreover, according to (Radaelli, 2000), in core of this approach is a process of socialization and learning amongst EU Member States, which is not controlled by any of the EU institutions.

13

Among major goals of both Portugal and Poland’s foreign and security policy goals, have always been the promotion of close ties with the United States, perceived in both countries as the major guarantor of security in Europe. Their loyalty to Washington can be seen their support of the military Operation Allied Force against Serbia during the Kosovo War in 1999 and the Operation Enduring Freedom in Iraq, in 2003. Moreover, NATO has always been a backbone of national security and collective defense for both countries, with the CSDP being considered as a complementary project to the CFSP/CSDP. In addition, Poland and Portugal took a series of initiatives in order to support the CSDP and have actively been taking part in most of the CSDP’s missions and operations.

1.1. The state of the art

“Europeanization can be a useful entry-point for a greater understanding of important changes occurring in our politics and society. The obligation of the researchers is to give it a precise meaning”

[K. Fatherstone]

The analytical approach of Europeanization has gained increased interest among scholars around the world over the last two decades, and generally perceived as a “fashionable” (Olsen, 2002), “faddish” (Featherstone, 2003), as well a “highly contested concept” (Kassim, et al’, 2000). As the Europeanization research has evolved, the term has been used to describe a variety of phenomena and processes, while a consensual and precise definition has been missing (Olsen, 2002; Kassim, 2000; Borzel, 1999, Radaelli, 2000, Mair 2004). What then, is Europeanization? And how is defined in literature? A group of scholars in this field understand Europeanization as a construction and development of the EU’s institutions of governance (Green Cowles et al 2001; Borzel 2003; Radaelli 200; Rise 2001) “that formalize and routinize interactions among the actors, and of policy networks specializing in the creation of authoritative European rules” (Bartolini, et al 1999), while placing the emphasis on the domestic impact of European integration (Graziano and Vink, 2007). Others discuss about the scope of Europeanization, arguing if it should be limited only to the impact of the EU on member states (Featherstone

14

2003; Risse et al 2001) or rather seen from a much wider perspective, taking into consideration sociological and historical conditions or intercultural dimensions (Flockhart 2007; Howell 2004).

A significant amount of the Europeanization literature has been focused on two main dimensions: top-down (downloading) and bottom-up (uploading). In the context of downloading, Europeanization is seen as a process of change in the domestic policy processes and politics of the member states level as a result of pressures coming from the EU. Ladrech (1994) provides one of the earliest definitions of the top-down approach, while seeing Europeanization as a process by which the EU is able to influence the domestic policies and institutions. Correspondingly, Buller and Gamble (2002), as well as Hix and Goetz (2000), see Europeanization as an impact of the EU governance system on the policies and behavior of the member states.

Research on top-down Europeanization also examines the importance of the goodness of fit statement. The respective argument, according to Risse et al. (2001), holds that the main factor which regulates changes in domestic polity and politics is the degree of compatibility of the arrangements between the EU and member states. In other words, if the politics and policies of the EU are fully compatible with those at the domestic level, member states are not obliged to change their legal provision, which means that the Europeanization process acquires a less challenging character. Moreover, Bache and Jordan (2006) state that Europeanization cannot even happen without such a pressure of the EU, which is conceived as a sufficient condition for successful Europeanization process. From this point of view, some ‘misfit’ (Duina 1999) and ‘mismatch’ (Heritier et al.1996) between the politics, institutions, and processes on the European level and national one have to exist (Börzel and Risse, 2003). The top-down approaches have made an important contribution to explain the changes in member states policies as a result of accession to the EU. Nevertheless, there are many scholars who criticized this approach for its excessive simplicity. Börzel (2005: 60), for instance, argues that top-down approach is focused on only one-way interaction between the EU and national policies of member states, calling them just a “passive receivers of European demands for domestic change”. In his view, this approach disregards two-way process of ‘downloading’ and ‘projecting’ of the national policies at the European level. In the same vein, Featherstone and Kazamias (2001) and George (2001) state that member states are not just inactive recipients of the EU influence, and agree that

15

Europeanization should be considered as a two-way process. Similarly, Bache and Marshall (2004) point out that the success of uploading is determined by a fruitful downloading. Other groups of scholars in this field focus their research on the bottom-up approach of Europeanization which explains how member states are able to shape and upload their policies into the European level (Bulmer and Burch, 2001; Börzel 2002; S. James 2007). For Radaelli (2003: 30), Europeanization is the

Processes of (a) construction (b) diffusion and (c) institutionalization of formal and informal rules, procedures, policy paradigms, styles, ‘ways of doing things’, and shared beliefs and norms which are first defined and consolidated in the making of EU decisions and then incorporated in the logic of domestic discourse, identities, political structures, and public policies.

In this definition, Europeanization is seen as a dependent variable plus interactive process, and goes beyond the conception of the EU influence on domestic politics. Similarly, Börzel (2005) states that in order to maximize profits and minimize the costs of the EU policies, the best way is to ‘upload’ national interests to the European level. Moreover, it may be a beneficial process for member states and will help to avoid changes and modifications in specific sectors of policy (Hang, 2011). In the same vein, Vale (2011) notes that taking into account ‘two-way’ Europeanization is useful in terms of clarifying the limitation of influence of member states, since he assumes that after uploading the national policies to the European level, they are additionally discussed and revised. Thus, member states cannot have a direct impact on the EU policy outcomes. Nevertheless, linking together the top-down and bottom-up approaches creates a huge methodological challenge for Europeanization research. If the two dimensions are seen as mutually influencing each other, the borders between independent and dependent variables are becoming fuzzy and difficult to differentiate (Alecu de Flers, 2010). In this context, Börzel (2001, 2003) points out the important role of the national governments in relation to EU institutions, describing them as a takers and shapers of the EU policies.

It is notable that some authors are focused on specific aspects of Europeanization, such as the changes in domestic institutions of member states which make the explanation too narrow and limited, while others consider wider theoretical implications while trying to employ a variety of interpretation of the term (Radaeli and Pasquiem 2007, Kassim 2000). Similarly, Dyson and

16

Goetz (2002) point out, that when it comes to a narrow usage of the term, scholars tend to bring up aspects of implementation of the EU legislation, while when talking more broadly, they emphasize policy transfer and learning inside the EU. Accordingly, Flockhart (2010) notices that many authors emphasize only political processes while excluding others. In this way, Radaelli (2000) claims that Europeanization is not easy to define, because in some way, all of the things “have been touched” by Europe, thus all these things have been Europeanized. Other discuss if Europeanization itself is an effect of integration rather a new way of creation of the European governing model (Koukis, 2001, Harmsen, 2000). Featherstone (2003) sets forward the argument that Europeanization cannot be classified as a theory, but rather a conceptual framework. Moreover, Olsen (2002) has raised a question about usefulness of this confusing term, while eventually concluding that, “It may be premature to abandon the term”.

In contrast to other policy fields, including those related with the EU’s first pillar, foreign and security policies have been much less analyzed and studied (Green Cowles, Caporaso, and Risse 2001). Several authors (Miskimmon, 2007; Tonra, 2001; Torreblanca, 2001; Wong, 2005; Gross, 2009; Aleu de Flers, 2010), however, have made important contribution to this field. According to Alecu de Flers (2010), lack of attention to the Europeanization of foreign policy can be explained by a specific character of CFSP and in particular its strongly intergovernmental character which stands in contrast with the common policies associated to the first pillar. The author also argues that the distinction between the first and second pillars in terms of Europeanization can often be misleading, because the dynamics of Europeanization may be different in policy areas in the first pillar of EU. Bulmer and Radaelli (2004) point out that there is no single logic of Europeanization beyond the communitarized / EU policy areas, which is not the case of the foreign policy that is based upon non-hierarchical and voluntary basis as there is no clear obligation of adapting EU policy into the member states. In the same vein, Kaminska (2007) and Pomorska (2011) maintain that the dynamics of Europeanization in foreign policy areas differ from other policy fields as in this specific case there is no legal pressure or procedures of implementation and the European Court of Justice does not have any prerogatives. Torreblanca (2001) indicates that we cannot classify foreign policy as just another public policy; therefore, the Europeanization of this specific matter will follow a unique trajectory. In this connection, Risse et al. (2001) suggest that one of the important factors in this process is not only the adaptation of common rules, but also the learning dynamics. Accordingly, Schimmelfennig

17

(2001) claims that learning can be successful only when national actors are able to change norms and values and the way of thinking. Some of the authors such as Dumka (2013), de Flers (2010), Pomorska (2011), and Wong (2005) emphasize the importance of the mechanisms of the Europeanization of foreign policy such as socialization and learning as the key elements for successful policy adaptation.

According to de Flers (2010:12), the way of adaptation of foreign policy is different in individual member states, which is determined by many aspects such as size, historical variables, or the “extent of a state’s foreign relation network”. This view is supported by Miksimmon (2007) and Gross (2009) who argue that the larger member states are shapers, rather than takers, of European foreign policy. In addition, Tonra (2000) holds that the impact of the EU is usually more visible on the smaller member states. In the view of Kaminska (2010), however, the size of the individual countries is less important in comparison with the skillful entrepreneurship, the capability to shape the policy-making process, and the ability to build coalitions or affective cooperation with other member states. These tools, according to Kaminska, are necessary in order to be a visible player in the EU external relations.

With the regard of the Europeanization of Polish foreign policy, the respective literature has been recently increasing (Kaminska 2007, 2010, 2014; Juncos and Pomorska, 2006; Pomorska, 2011, 2014; Rapacki 2012; Nagorski 2014; Dumka 2013). All of the cited studies emphasize the Polish adaptation and learning process, as well as its impact on the CFSP, while especially focusing on the case of the Eastern Partnership. Poland is often referred to as an example of successful Europeanization process both in terms of the national adaptation of the EU policies, as well as of the projection of its preferences onto the European level. Brennan (2005) points out the fact that Poland is the largest country that had joined the European Union in 2004 and has been an important player in the EU region and NATO strategies since then. Copsey and Pomorska (2008) move further, claiming that the EU enlargement to the East could be even called the “Polish enlargement” due to the country’s population and economic weight in comparison to other Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs). As Zaborowski (2004) claims, the closer integration with the West was caused by the regional defense reasons, especially the threat from Russia and concern to be left out in the ‘grey zone of security’. Moreover, Kaminska (2007) maintains that due to the former experience and geopolitical

18

position, Poland needed strong security guarantees, and therefore the accession to the EU and NATO was the only way to guarantee security for both the country and the region. She also highlights the difficulties of the Polish situation before the accession as a post-communist country, and its weak bargaining position soon after the enlargement in 2004, which, however, have not prevented Poland from becoming the front-runner in its successful adaptation to the CFSP. Nagorski (2014) argues that the reason of this integration, which turned out to be effective in spite of the country’s economic problems, was the ‘shock therapy’ commanded by the Finance Minister Leszek Balcerowicz. This led Poland to reduce inflation from 10 percent to 2 percent from 2001 to 2007.

In the same vein, Rapacki (2012) discusses the institutional challenges that Poland had to face as a latecomer and ‘outsider’ to the Western-type capitalist system and describes Poland as the best performer among Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)-10 countries. In his view, the institutional factors have determined the Polish success to fully transform its economy, from the planned economy into the market economy. Domestic institutions, according to Juncos and Pomorska (2006), were the key elements of the fruitful transformation that created a base which ‚would allow for projecting and receiving from EU’. The integration process enforced the formation of new administrative bodies for productive harmonization of European policies (Kuzniar, 2008). However, the institutional setting was not the only one in need of a re-evaluation: it was especially the way of thinking of the administration and political elites (Kaminska 2010). The lack of coordination and efficient cooperation among administrative bodies and well-established institutions in the area of CFSP has slowed down the decision-making process, and the inefficient professional civil service led to many opportunities to upload policy to the EU level that were missed. Moreover, the ‘communist legacy’ (Kaminska 2010), was still visible in the administrative structures, which represented a huge challenge for the successful development. Juncos and Pomorska (2006) also mention the problem of generation gap and strong politicization of public administration. Nevertheless, Kaminska (2008) argues that under the Civic Platform government, the administrative changes are visible in every government bodies related to EU issues, even though the process occurs slowly. According to Pomorska (2011), it took time for the officials in Warsaw to understand ‘the rules of the game’, but after undergoing a process of socialization, the learning process of the national representatives in Brussel has been incremental. Moreover, Juncos and Pomorska (2006)

19

highlight the importance of the role of Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) who had to face the biggest challenge of EU membership and participation in CFSP. MFA, and the diplomatic staff, had the responsibility of translating Brussel’s politics to Poland. As Kaminska (2007) noted, although at first Poland was very critical and skeptical about ESDP/CSDP, it subsequently started to actively participate in ESDP/CSDP missions in many regions in the world, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, that has never been a domain of Polish foreign policy interest. Moreover, the CFSP became for Poland “a great instrument for achieving its goals and gaining influence in the EU” (Kaminska, 2007).

During the Polish Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2011, Poland had proven to be a fast learner of the EU’s rules, especially during the pro-European Civic Platform government and the Sikorski-Tusk ‘duet’ (Pomorska and Vanhoonacker, 2012). On the one hand, according to Pomorska and Vanhoonacker (2012), the Polish presidency was well organized and managed to strike many deals inside the Council and other institutions, such as the European Parliament (EP); on the other hand , the Presidency has passed unnoticed, with the aoption of the Six Pack legislative being the biggest achievement. Pomorska and Vanhoonacker (2012) have concluded that: “While in the past it was at times of crisis when the Presidency used to catch the public eye, now it was exactly because of the crisis that the Poles remained in the shadows”.

Most of the literature on Europeanization of Polish foreign policy is a unique example of successful input to the CFSP deals with the Eastern Dimension initiative of the ENP, which Poland aims to shape. According to Kaminska (2007) and Antczak-Barzan (2015), the Eastern dimension and Poland’s ideational export to EU Eastern neighbors, especially to Ukraine, has been related to the regional security and democracy promotion and based on Poland’s own experience. Thus, Poland has acted actively as a ‘younger brother in democracy’ for the Eastern European states, while its main focus has been to stabilize the Eastern neighborhood by building alliances with the help of Western powers. Moreover, Nagorski (2014) takes into consideration the historical background of the two countries (i.e., Poland and Ukraine), arguing that it had important impact on future relations, as their starting point was very similar. Similarly, Petrova (2014) discusses that Polish leaders have, since beginning, believed that a stable Ukraine means a secure Poland, as Ukraine’s sovereignty and democratization without any doubts would result

20

in an improved stability in the region. According to the author, it was Poland that had played the central role in bringing Ukraine closer to the EU structures acting as a strong supporter of democratic reforms during the Orange Revolution in 2004. This engagement, as Pomorska (2011) argues, was one of the major achievements of Polish diplomacy and proved that Poland was able to contribute effectively to EU’s foreign policy. According to Sus (2011), it was the Eastern Partnership that meant essential success of uploading Polish national interest into the EU level. What makes it more unique is the fact that the idea of Eastern Partnership had emerged from a new member state and not from one of the ‘usual suspects’, i.e., countries such as France or Germany. That said, as Dumka (2013) claims, a fruitful relationship with Sweden brought not only the mutual cooperation and support for equal interests, but importantly gave the Polish policymakers a great opportunity to learn about the policy-making process from a more experienced counterpart. As noted by Petrova (2014), Polish democracy promotion in Ukraine successfully penetrated the elite and society of the country, especially after the engagement in the Euromaidan movement in 2014 and the prominent role of Radoslaw Sikorski, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Taken all together, these studies indicate that over the last two decades, Poland had successfully transformed from a ‘policy taker’ into a ‘policy maker’ and as a result of integration with the European structures, Poland became an important player in the European Union.

Europeanization of the Portuguese foreign policy has recently attracted attention of many scholars in this field. Portugal has been always eager to make a contribution to shape the EU external relations in order to avoid marginalization, despite its constraints in terms of economic and military resources (Raimundo, 2013; Ferreira-Pereira, 2007). Macedo (2006) and Teixeira (2005) emphasize that Portugal’s traditional foreign priorities, for many centuries, have been concentrated in the Atlantic and its overseas territories, which were considered vital to protect its sovereignty from the continental threats. Teixeira and Costa Pinto (2012) conclude that after the democratic changes and the accession to the EU in 1986, Portugal’s foreign policy acquired a strong European focus, without undermining its longstanding Atlantic roots. This is reflected in the description “of Portugal as a nation, simultaneously Atlantic and European”. Raimundo (2013) argues that Portugal, as a founder member of NATO, continued its strong engagement in the Atlantic Alliance and close cooperation with the United States. Moreover, as Ferreira-Pereira (2007) argues, during years of involvement in the European political integration process, the

21

Atlanticism and the centrality of NATO has never been seen in Portugal as a barrier in its relations with EU and particularly within the CFSP’s activities. Rather, in the Portuguese view, the CSDP and NATO should be seen as complementary projects.

Portuguese commitment to the European integration according to Vasconcelos (2000:5), was related to political reasons and perception of a peripheral position of the country. In his view “posing as a “good pupil” in the Community classroom, Portugal adopted a diplomatic approach which was highly cautious and based on defense of the status quo, and remained strongly attached to an intergovernmental outlook, on the assumption — which still exists — that Portugal’s interests were often minor or peripheral compared with the "Community average". Vasconcelos (2000) and Ferreira-Pereira (2007) describe the period after the Portuguese accession in 1986 as mostly economy-oriented. However, from the early 1990s, according to Raimundo (2012), Portugal changed its approach toward a more active and open attitude, especially regarding foreign and security policy. Robinson (2015) maintains that as a result of Europeanization, Portuguese foreign policy adapted well to the European realities, while showing an understanding of the increased interdependence and common priorities existing among the EU member states. At the same time, the country has successfully managed to bring the Lusophone matters into the European agenda.

Most of the literature on the Europeanization of the Portuguese foreign policy, investigates the role of the three Portugal-led Presidencies of the Council of the EU (i.e., 1992, 2000, 2007) as significant examples of successive uploading of the core national policies by Portuguese governments at the European level. There is a general agreement among the authors, that Portugal’s Presidencies had a crucial role in shaping the CFPS and characterizing the relations between the EU and the Lusophone world (Vasconcelos, 1996, 2000; Ferreira-Pereira, 2007, 2008, 2014; Teixeira and Costa Pinto, 2012; Robinson 2015, Magone, 2015; Cunha, 2015). The first Portuguese presidency in 1992 was described as the first “great test” and the main priority of the Portuguese foreign policy, and an opportunity to make its contribution to the European affairs and enhance the image of the country abroad (Vasconcelos, 2000; Ferreira-Pereira 2014; Robinson, 2015; Cunha, 2015). Some of the authors as Magone (2015) and Robinson (2015) argue that the second presidency in 2000 was more effective, as Portugal had learnt a lot from the previous experience and invested significant effort into developing the

22

experience and skills necessary to have a significant impact on the European integration process. The third presidency in 2007 was centered on the dialogue between the EU and Africa. The second EU-Africa Summit, as well as steps toward forging a closer cooperation with Cape Verde, were example of successful uploading of the Portuguese interests (Ferreira-Pereira, 2008; Guedes Vieira and Ferreira-Pereira, 2009). In the same vein, Robinson (2015) points out that during three Presidencies, the close cooperation between the EU and Latin America, and also Africa and the Mediterranean, has been always a core interest of Portugal, demonstrating the ability to use agenda-setting powers in connecting the national foreign policy goals with the broader priorities of CFSP. Moreover, as Ferreira-Pereira and Groom (2010) argue, the ‘Lusophone card’ in Portuguese foreign policy interests was played very successfully, which has strengthened image of the country in Europe and worldwide. Moreover, as noted by Fiott (2015), during its engagement in the development of Defense and security developments in Europe, Portugal has been using CSDP as a tool to represent its voice in the global arena; and had been actively taking part in most of the CSDP’s missions and operations, such as EUTM missions in Somalia and Mali and the CSDP anti-piracy operation ‘Atalanta’.

All of the presented studies above agree that Europeanization of Portuguese foreign policy is a success story, especially in the domain of the projection of its national interests. Moreover, the advocacy for the Lusophone countries has allowed the Portuguese foreign policy makers to develop a special role identity within the EU and effectively shape the CFSP.

This section aimed to review the existing literature on the concept of Europeanization in the foreign policy and security realm and the major scholar works related to the two case studies: Poland and Portugal. In view of all that has been mentioned so far, one may suppose that the research on the Europeanization of foreign policy is a growing body of literature and the numbers of publications are still increasing. However, many of them do not offer a clear definition on Europeanization, nor distinctions between the dimensions and mechanisms that drive Europeanization (Ladrech, 1994; Harmsen and Wilson 2000; Olsen, 2002). As there are a range of approaches, only few authors have tried to explain its exact meaning (Flochart, 2010; Hill, Wong, 2012). Moreover, some of the studies have focused mostly on the national adaptation (Bache; Knill and Lehmkhul, 2002; Bulmer, 2007; Wong, 2007 Buller and Gamble, 2002; Hix and Goetz, 2000) while overlooking the impact of national projection in EU’s

23

common policies. Also, most of the former studies in this area have mainly aimed to explore, in a brief way, the Europeanization of all member states and chose to concentrate on individual countries that play more influential role in the EU, such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom (Schmidt, 1997; Börzel, 1999; Goetz, 1995; Laderch, 1994; Bache, 2005). Among few exceptions to this tendency is the contribution of Eva Gross (2009).2 On the other hand, the peripheral countries, such as Poland and Portugal have been analyzed much less. Europeanization of the Portuguese foreign policy has been explored by scholars such as Ferreira-Pereira (2007, 2008, 2014) and (Robinson, 2015). Some scholars as Raimundo (2012, 2013) carefully investigated the impact on the EU membership on the relations with countries such as Angola or Mozambique, and therefore filled the gap in existing literature. However, most of the studies treat the Portuguese case in general terms (Teixeira and Costa Pinto, 2012) instead of paying attention to the impact of Europeanization on the national policy (Vasconcelos, 1996, 2000). In addition, some studies that do mention Europeanization end up being unsystematic in the matter of what has been ‘downloaded’ and ‘uploaded’ (Magone, 2005).

In case of the Europeanization of the Polish foreign policy, scholars have been mostly focusing on the internal transformation or domestic economic situation (Brennan, 2005; Rapacki, 2012; Dąbrowski, 2012). Recently, authors have paid more attention to the Polish potential of shaping the EU policy agenda, especially in the case of Eastern Partnership (Schweiger, 2016; Pomorska, 2014; Kaminska; 2008, 2014; Sus, 2011; Szczepanik, 2011; Dumka, 2013). Most importantly, to date, no comparative study on the Europeanization process of both Portuguese and Polish in the security and defense fields has been produced, with exception of the contribution of Chrobot (2012) 3. Yet, with respect to the latter, the present study takes into consideration the uploading dimension of Europeanization of Portugal and Poland, while the previously mentioned one only focuses on the downloading process. Overall, the present study attempts to fill in this specific gap in the literature.

2 The author explains in details the contrasting positions of France, Britain and Germany toward the foreign and security institutional framework

of the EU and their involvement in the European crisis management taking into account the military operations. According to the author, those countries had a crucial impact on the evolution of CFSP and ESDP instruments.

3 While representing the first of this kind of comparative contributions, this contribution has chosen to approach the Europeanisation as a one-way

and top-down process, in addition to treating foreign and security policies as just one part of a more general Europeanisation process. Moreover, the study did not focus on Euroatlanticism and NATO which are important aspects in the comparison of both countries.

24

1.2. Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of this study is based on the Europeanization approach, which allows understanding the dynamic process of foreign policy change in Portugal and Poland. Taking into account the analysis of the current state of the art, the present project aims to explore the downloading and uploading processes in an integrative way, rather than studying them separately. This perspective will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the Europeanization process in the two countries. Europeanization here is understood as “a process of incorporation in the logic of domestic (national and sub-national) discourse, political structures, and public policies of formal and informal rules, procedures, policy paradigms, styles, “ways of doing things”, and shared beliefs and norms that are first defined in the EU policy processes” (Moumoutzis, 2011) and ‘the impact, convergence or response of actors and institutions in relation to the European Union” (Featherstone, and Kazamias, 2001). The downloading dimension indicates the top-down process of national adaptation of the European policies and integrating choices made at the European level. At the same time, Europeanization is also a ‘bottom-up’ method of uploading domestic policies to the European level and being able to shape them.

Figure 1. Europeanization model based on Miskimmon (2003)

Downloading Uploading

Common Foreign Security of the EU

Portuguese and Polish Foreign and Security

policy

The CFSP policy-making environment

25

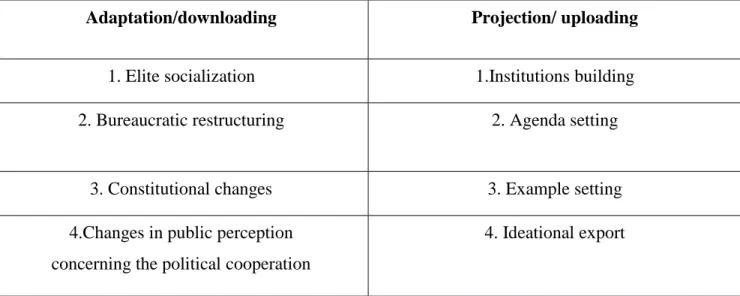

As Börzel (2003) points out, the national governments have been acting as “shapers and takers” of EU policies in the relationship between member states and the EU. In case of downloading, further analysis will follow the model introduced by Smith (2000), which identifies four main indicators of Europeanization at the domestic level: elite socialization, bureaucratic restructuring, constitutional changes, and changes in public perception concerning the political cooperation. At the ‘uploading’ level, the emphasis is placed on the Miskimmon and Paterson model (Miskimmon and Paterson 2003), which includes the dimensions of the institution building, agenda setting, example setting, and ideational export (can be seen in Figure 1). Kaminska (2007) has integrated these two models, which has eventually allowed highlighting different levels of uploading and downloading for Europeanization processes, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Model of Europeanization process Kaminska (2007)

Adaptation/downloading Projection/ uploading

1. Elite socialization 1.Institutions building

2. Bureaucratic restructuring 2. Agenda setting

3. Constitutional changes 3. Example setting

4.Changes in public perception concerning the political cooperation

4. Ideational export

Elite socialization takes place when the national elites, via interaction with the European institutions, are adopting the shared European values, promoting the European norms and “way of doing things”, coming from Brussel (Wong, 2011). It is the effect of contribution of the domestic actors in the CFSP system identified by the norms of the consultation, consensus-based decision making, and communication. The level of socialization among major decision makers is

26

considered vital for a successful decision-making on the EU level (Smith, 2000). Moreover, although their power is limited, the actions taken by the national elites may result in important costs for development and social change. Bureaucratic restructuring refers to the formation of new offices and positions inside the Member States and mechanisms that coordinate the relations with other government offices in order to fully participate in the CFSP. The deviations in the national environment are also leading to the constitutional change and may affect the transformation in the public discourse. The foreign policy collaboration may affect the public support for the CFSP, which ends in changes in public opinion of national foreign policy (Smith, 2000). The ability to shape the EU decision making process is connected to the proficiency of the high adaptation to the EU on the national institution level. The link between national and foreign is particularly visible in the intergovernmental nature of the CFSP (Kaminska, 2014). The first instrument of uploading dimension reflects the ability of the state to build the institutions in order to adapt to the new environment. Through contributions in such institutions, countries are able to pursue multilateral solutions to international challenges. The agenda setting refers to the ability of the national leaders to transfer domestic issues on the European agenda, especially during the 6-months country Presidency of the EU Council. The example setting means the ability of the state to act as an example on the specific field which is related to the capacity to serve as an expert of successful uploading of its national preferences. In the ideational export, the focus is on the process of projecting the policy objectives or new ideas, in terms of internal restructuring and also policy change (Kaminska, 2014).

The theoretical models proposed by Smith (2000) and Miskimmon and Paterson (2003) are the most suitable ones for this study’s purpose and most useful to analyze the Europeanization process in countries with such a different historical backgrounds and regional priorities. Moreover, the described models clearly distinguish both dimensions of Europeanization, in order to fully understand the key mechanisms of downloading and uploading processes. They are also useful to explain the indicators of the national adaptation process, as well as the tools and methods used by the states in order to project its national interests into the CFSP level.

27

1.3. RESEARCH DESIGN

1.3.1. Research problem

The main focus of this research is to compare Europeanization processes of Poland and Portugal in the specific fields of the foreign and security policies. In this regard, the ultimate goal of this study is firstly to identity the similarities and differences existing in the Europeanization processes of these two countries, and secondly to find out the factors that have influenced the existing differences and similarities in their trajectories.

1.3.2. Research question

In order to accomplish its objectives, the present work is steered by the following central research question:

How have Poland and Portugal been able to effectively shape the CFSP/CSDP and project their national preferences at the EU level while having to adapt themselves to the deepening in the European foreign and security policies?

This main research question is divided into a set of sub-questions in order to simplify the author’s effort to carry out a comprehensive research:

- Which changes have taken place in Poland and Portugal foreign and security policies as a result of their adaptation to the evolution of the CFSP/CSDP?

- How have Portugal and Poland been uploading their national foreign and security policy preferences to the evolving the CSDP/CSDP, particularly those ones related to their Atlanticism and relations to neighbors and historical allies?

- What are the main similarities and differences in case of downloading and uploading national preferences into the CFSP/CSDP level?

28 1.3.3. Research methods

The most suitable research method to achieve the goals and objectives of this project is the comparative analysis, which is often chosen for cross-national studies aiming to identify similarities and differences between a small numbers of states. As Poland and Portugal are two different countries in terms of their geopolitical location, as well as historical and cultural background, in addition to the regional priorities, national interests, and with different timing of accession to the EU, the comparative analysis is seen as a sufficient approach to investigate the similarities and differences of both countries. This comparison will be supported by the Europeanization as main theoretical framework of this study. In order to assure validity of relating causes to effects, a set of observations instead of a single inspection will be examined, as suggested by Gerring and Christenson (2015) for comparative studies. The orientation of the government toward the fundamental issues of history and politics will also be included in these sets of observation concerning recommendation of George and Bennett (2005). Moreover, the diversity of case studies, as well as their heterogeneity will be taken into consideration based upon the suggestion of Rihoux and Ragin (2009).

As a comparative research, this work will propose qualitative indicators for both case studies. By using qualitative indicators such as the level of accomplishment of the national adaptation and projection (administrative and institutional structure, adaptation and policy convergence, re-adjustment of geographic/regional priorities, strategy of uploading national priorities, contribution to the EU’s foreign policy making) and categorizing the criteria into sub-groups, comparison of both case studies will be performed. The qualitative strategy, in comparison to a quantitative one, emphasizes the meaning of words, rather than data collection or numbers, and reflects different ontological and epistemological positions (Bryman, 2012). Moreover, it is a suitable approach for investigating the social actors (Tuli, 2011). Regarding the data of this study, primary and secondary sources will be taken into consideration for this comparison, including official documents published by both the Polish and Portuguese governments, as well as by the EU and NATO. In relation to this, one of the main limitations of this study is the author’s lack of linguistic competence in Portuguese, a challenge that has admittedly conditioned the investigation process, but that has been addressed by recruiting to the help of native speakers,

29

which was facilitated by the author’s residence in Portugal between 2014-2017, in the framework of the Master Programme in International Relations at the University of Minho.

This work aims to investigate the Europeanization of foreign and security policies of both countries, since their accessions to the EC/EU until 2014. Thus, in terms of the time frame, the study explores the periods between 1986-2014 for Portugal and 2004-2014 in the case of Poland. Regarding the time frame, the thesis was initiated and the author had access to the published literature, interviewing the publications until 2014 (with some exceptions). However, the cultural and historical backgrounds of the studied countries are different, which has been taken into consideration. The study did not examine the recent happenings in Europe and worldwide (after 2014), such as the Ukrainian crisis and further developments in Western Ukraine (while the study briefly mentions the Polish role in and involvement into the Ukrainian crisis, in its very beginning in November 2013, these events have not been investigated in depth), government changes in both countries, Brexit process, or refugee flow. This thesis has mainly focused on particular dimensions of Portuguese and Polish foreign policies, in order to show how both dimensions of Europeanization occurred in both countries, and they were able to effectively shape the CFSP environment.

1.4. Structure of the dissertation

The presented project is organized into six chapters. The Introduction chapter provides an overview of the relevant literature and presents the basic concepts underpinning the investigation project. Moreover, the theoretical framework and the relevant research methodology are presented.

Chapter 2 starts with a brief historical background of both countries in order to understand the major changes that occurred in foreign and security policies after their democratization processes. The characterization of their contemporary foreign and security policies shall provide the backdrop against which this chapter will outline the process of Europeanization of foreign policies in both countries during the pre-accession and accession years of negotiations. Moreover, this chapter will compare the reorientation of foreign policies after the collapse of non-democratic regimes to show the similarities and differences between them and discuss to what extent this process was distinct and voluntary.

30

Chapter 3 will study the Europeanization of the Portuguese foreign and security policies. This section will take into consideration the downloading dimension, as well as the uploading dimension to investigate the Portuguese ability of projecting its national interests and shape the CFSP. In the case of uploading, this particular study will focus on the Portuguese Presidencies, as well as strong advocacy for the Lusophone world with the correlation of Atlanticism in foreign policy and security agenda.

Chapter 4 aims to explore the Europeanization of Polish foreign and security policies. The main focus will be on the national adaptation of the country to the European structures and domestic changes that have been taking place after the EU accession in 2004, as well as the national projection, in order to measure how Poland has been actively engaged in shaping the CFSP evolution. This section will investigate the Polish role in agenda setting in EU toward countries like Ukraine, Belarus, and Georgia.

Chapter 5, shall identify the differences and similarities of the Europeanization processes of the two countries, while taking into consideration both the downloading and uploading dimensions.

Chapter 6, will draw conclusions based on the former findings, as well as indicate the challenges for future work.

Despite the differences of Poland and Portugal in terms of their size, as well as the background or regional priorities, both countries have experienced similar shifts in their foreign and security policies orientation. Shortly after the collapse of non-democratic regimes in Poland and Portugal, the European option with a full compatibility to NATO became their first foreign policy priority. Warsaw and Lisbon went through many administrative changes in order to adapt to the EU’s apparatus and be able to effectively shape the CFSP. It has to be noted that the Atlantic Alliance has been always seen as the most important national security guarantor, and both of the countries were against any development in the EU that could be incompatible with NATO’s interests. Poland and Portugal were able to leave their mark in the CFSP/CSDP by introducing their national preferences into the wider agenda. Both of them realized that only through the active CFSP/CSDP engagement could Warsaw and Lisbon avoid marginalization and reaffirm their importance among other EU states. Poland has successfully managed to bring

31

Ukraine closer to Europe by introducing the Eastern Partnership (EaP) and taking various initiatives in favor of Ukraine’s future membership in the EU. Portugal has since its accession played an important role for enhancing closer relations between the EU and the Lusophone world. Through its three Council Presidencies (1992, 2000, 2007), Lisbon was able to build the bridge between the EU and its former colonies and create a crucial platform for future cooperation. Beside their limitations, both countries have actively contributed to the CSDP and NATO missions and operations and were able to go beyond their traditional zones of interest. Poland and Portugal proved to be important players in the CFSP affairs, and learned that a proper uploading can be only obtained through an effective downloading process. Both countries understood the importance of fast learning and adaptation to the rules and policies of the CFSP. Mechanisms of Europeanization, such as socialization and policy learning, affected foreign policy making environment and projection of national interests. As both dimensions are linked to each other, it can be concluded that appropriate learning of rules of the Brussel game affects the country’s performance in uploading its national preferences into the CFSP.

32

2. The Foreign and Security policies of Portugal and Poland: The

Impact of Democratization

2.1 Introduction

The Portuguese Revolution of 25th Abril 1974 and the Polish peaceful negotiations of Round Table in 1989 resulted in collapse of non-democratic regimes and led to the process of democratization and reorientation of foreign and security policies. The new leaderships, democratic transition and orientation of these countries’ toward the accession to the European Communities EC/UE resulted in a revision of geopolitical options and a redefinition of Portuguese and Polish roles in the world.

In Poland, the democratization process had a fundamental impact on the foreign policy and its redefinition. The process of transition was not an easy one, after a long period of dominance exerted by the Soviet Union and participation in organizations such as the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) 4 and the Warsaw Pact. As other members of the Eastern bloc, Poland was militarily controlled and dependent on the USSR in political and economic terms. Thus, its foreign policy was controlled largely by the Soviet Union. The transformed and independent Polish ‘return’ to Europe and to the international politics started after joining the NATO in 1991 and the EU’s Eastern enlargement (Kaminska, 2007; Kuzniar, 2008; Zieba, 2012).

The process of the European integration was challenging for Portugal, to the extent that it was preceded by a lengthy dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar, during which the country was isolated from both the European and global arena, despite its participation in the United Nations since 1955 and in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) since 1960. Moreover, the substantial change in foreign policy direction from Africa to Europe was a complex process, also due to the geostrategic location of the country. The process of negotiations and final accession coincided with an especially active period of the European integration, which eventually led Portugal becoming a part of the Iberian enlargement in 1986. As a founding

4 The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance was an economic organization under the leadership of the Soviet Union from 1949 to 1991.