Climate change implications on present and future public space. Modern day paradigms for urbanism and urban design: the case of Lisboa

Texto

(2) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Figure 1 - Sketch of Bairro da Bica Lisboa Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Source: Author’s Sketch. 1. “Good urban design is sustainable … this involves much more than simply reducing energy use and carbon emission. Instead it involves a much more profound basis on which to make decisions that impact the social, economic and environmental sustainability of the built environmet. It requires a holistic – sustainable place making – view that considers each dimension of urban design in terms of its impact on local and global contexts, and through associated delivery processes.” (Carmona, Tiesdell, Heath et al., 2010, p.367). 1. Document cover image source: By Noberto Dorantes – Lisbon | Plaza de Comercio| sketch draw with 200 participants | 2011 in Sketchers, U. (2012). Urban Sketchers em Lisboa drawing the city. Lisbon, Quimera. Back cover image source: Based on sketch by Florian Afflerbach – Lisbon Alfama 2007 in ibid. . II .

(3) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Public spaces can be separated into diverse typologies that provide different usages and environments. These differentiations are nevertheless interwoven by their role in nourishing urban culture, diversity and identity. This sustenance is conversely being burdened by uncertainties and contemporary preoccupations in light of climatic changes. This investigation shall analyse how the diverse typologies of public spaces shall contribute to new developing practices of urban design and planning that enforce adaptability and city life cycles. As a consequence this research shall analyse which contributions public spaces can have upon smart city preservation and growth. Relating these issues with the Lisbon case, a discussion will depict upon the development of its public realm, and how its resulting contemporary identity shall be defied by future change. Lastly, and as a result of this research, it is argued that the smart growth agenda establishes numerous goals that aid cities towards enforcing their climatic resilience. Namely, upon a selection of precedents this thesis exemplifies how urban design, urban planning, landscape architecture and architecture can improve city areas through the implementation of smart growth components.. Key Words: Public Space | Lisbon | Climate Change. III . Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Abstract.

(4) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Os espaços públicos podem ser separados em diversas tipologias que os caracterizam segundo diferentes usos e ambientes. Ainda assim, estas suas diferenças interligam-se no seu papel na cultura urbana, diversidade e identidade. No entanto, esta realidade tem vindo a ser ameaçada pelas incertezas e preocupações contemporâneas associadas às alterações climáticas Esta investigação propõe analisar como as diferentes tipologias de espaço público podem contribuir para o desenvolvimento de novas práticas de desenho e planeamento urbano enfocadas na adaptabilidade e aos ciclos de vida da cidade. Consequentemente, esta pesquisa visa analisar quais as contribuições que o espaço público pode ter na preservação e crescimento do ‘Smart Growth Agenda’. Relacionando estes aspectos com o caso de Lisboa, será ainda discutido o desenvolvimento do seu domínio público e o modo como esta identidade contemporânea será desafiada por futuras mudanças. Como resultado desta investigação por fim, é argumentado que o ‘Smart Growth’ visa vários objectivos que contribuem para as cidades melhorarem a sua resiliência climática. Nomeadamente, após uma selecção de precedentes, esta tese exemplifica como o desenho urbano, planeamento urbano, arquitectura paisagista e arquitectura podem melhorar áreas da cidade através da implementação de componentes de ‘Smart Growth’.. Palavras-chave: Espaço Publico | Lisboa | Alterações Climáticas. IV . Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Resumo.

(5) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Along the journey of writing this thesis, I would like to thank the following people for their:. Academic. João Pedro Teixeira de Abreu Costa | Pedro Filipe Pinheiro de Serpa Brandão Encouragement, time and guidance during the development of this topic and document. Maria Cabral Matos Silva Helpful and pragmatic nature. Ahmad Molla Esmail Nouri Continuous support and presence. Anabela Vieira Lopes dos Santos Continuous support and presence. Liliana Raquel Gomes Cruz Tavares Silva | Ricardo Salgueiro dos Santos Fernandes Estrela | Vítor Manuel dos Santos Francisco | José Guilherme Igreja Motivation and patience. V . Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Acknowledgments.

(6) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. ACCSP. Australian Climate Change Science Program. IAUC. International Association of Urban Climate. UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. CABE. Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. EEA. European Environmental Agency. PDM. Municipal Master Plan. SIAM. Climate Change in Portugal: Scenarios, Impact, and Adaptation Measures. CECAC. Executive Committee for the Commission of Climate Change. DGOTDU. General Directorate for Spatial Planning and Urban Development. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. List of Acronyms:. VI .

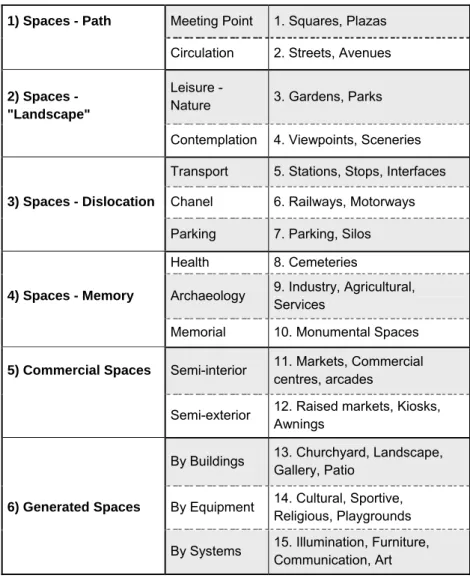

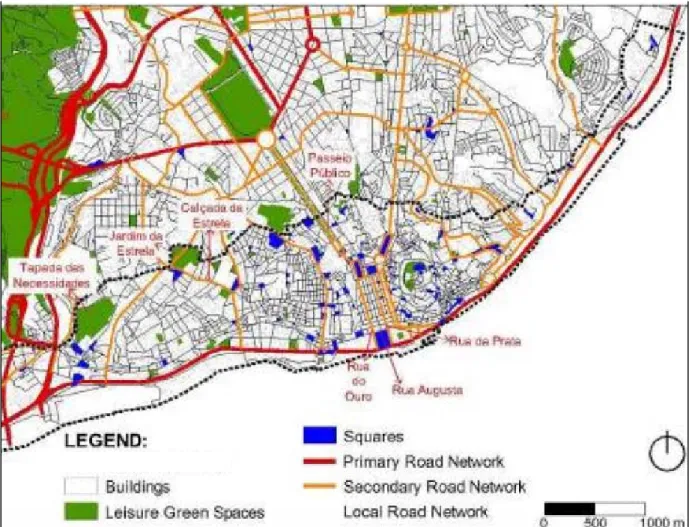

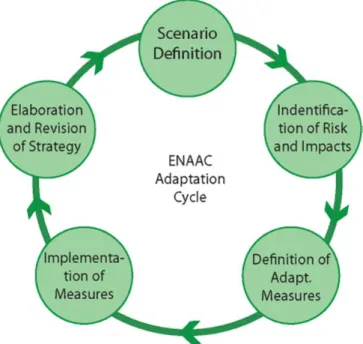

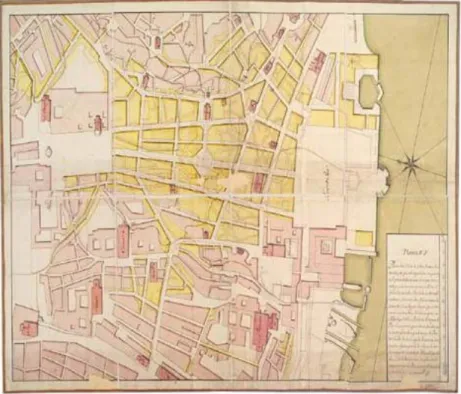

(7) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Figure 1 ‐ Sketch of Bairro da Bica Lisboa ............................................ II Figure 2 ‐ Menashe Kadishman, Installation Shalekhet (Fallen Leaves), 1997‐2001........................................................................................... 31 Figure 3 ‐ Plan Proposal by Eugénio dos Santos with the aid of Antonio Andreas to insert three major avenues that linked Rossio to the north and Terreiro do Paço to the south. .................................... 38 Figure 4 ‐ New alignment plan by Santos and Mardel ....................... 39 Figure 5 ‐ Embellishment project plan for Praça of D.Pedro IV.......... 42 Figure 6 ‐ Artists impression of the interior of Passeio Público ......... 43 Figure 7 ‐ Top: Suggested cross‐section plan of Faria da Costa for the Avenida da Liberdade profile. Bottom: Transverse Profile plan for the Avenida da Liberdade ......................................................................... 44 Figure 8 ‐ Pavement and streetscape profile design plans ................ 45 Figure 9 ‐ Drawing schematics of street furnishings as part of the public refurbishment program for the Avenida da Liberdade in 1885 by Frederico Ressano Garcia .............................................................. 45 Figure 10 ‐ (Left) Tile Panel by Carlos Botelho (Middle) Tile Panel by Rolando Sá Nogueira (Right) Detail of Tile Panel ‘The Sea’ by Maria Keil ...................................................................................................... 48 Figure 11 ‐ Present Public spaces network in Lisbon ......................... 52 Figure 12 ‐ Methodology of the ENAAC Adaptation Cycle ................. 57 Figure 13 ‐ Seasonal maximum temperature anomalies ‐ (a) winter (b) spring (c) summer (d) autumn ............................................................ 59 Figure 14 ‐ Annual and seasonal precipitation anomalies due to precipitation rates between 1mm/day and 10mm/day..................... 60 Figure 15 – Existing Daytime summer thermal patterns in Lisbon .... 62 Figure 16 ‐ Impact of Heat Shift / Humidity Shift / Pollution Shift on Human Body Analysis ......................................................................... 72 Figure 17 ‐ Park Plan with overlapped ‘meteorological maps’ .......... 73 Figure 18 ‐ 3D Renderings of the project ........................................... 74 Figure 19 ‐ Anti Heat / Humidity / Pollution Methods ....................... 74 Figure 20 ‐ Sound wave pattern inspiring the walking path within the park ..................................................................................................... 76 Figure 21 ‐ Plan, section, area designation and flora layout for the Callwood Park ..................................................................................... 77 Figure 22 ‐ Night view of the Forest ................................................... 78 Figure 23 ‐ Rendering of the park's largest clearings ......................... 78 Figure 24 ‐ 3D Render of winter view of Ephemeral Garden ............. 79 Figure 25 ‐ Illustration of the incorporation of over 100 objects within the Superkilen Park ............................................................................ 81 VII . Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. List of Figures:.

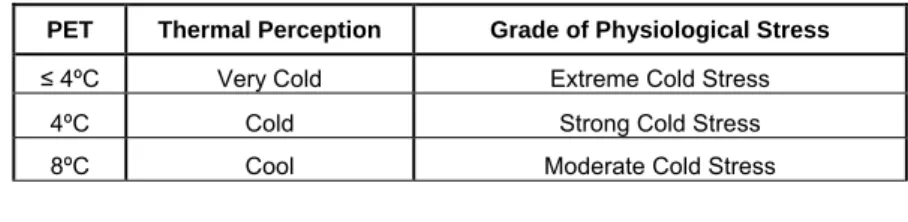

(8) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. List of Tables: Table 1 ‐ Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) ranges within different grades of thermal perception by human beings and physiological stress on human beings ................................................ 11 Table 2 ‐ Lisbonesque Public Space Typology Chart ........................... 50 Table 3 ‐ Identification parameters of Lisbonesque public spaces categories and sub‐categories ............................................................ 51 Table 4 ‐ Some expected climate change impacts (regarding temperatures) in Southern European countries and examples of possible adaptation measures ........................................................... 58 Table 5 ‐ Comparison table between the different selected precedents and Smart Growth outcomes .......................................... 93 . VIII . Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Figure 26 ‐ Rendering of the Red Square area within the Superkilen Park ..................................................................................................... 82 Figure 27 ‐ Rendering of the Black Square area within the Superkilen Park ..................................................................................................... 83 Figure 28 ‐ Rendering of the Linear Green area of the Superkilen Park ............................................................................................................ 83 Figure 29 ‐ Inventive design generators for each section of the Superkilen project .............................................................................. 84 Figure 30 ‐ Render of Gardens The Bay by Grant Associates ............. 86 Figure 31 ‐ Perspective and section of the cooled conservatories in the South Bay ..................................................................................... 87 Figure 32 ‐ Illustrations of the Supertrees during the day and at night ............................................................................................................ 88 .

(9) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Introduction ................................................................................... 1 Problem & Justification of Theme ................................................................1 Objectives of Thesis.....................................................................................2 Document Structure .....................................................................................3 Methodology ................................................................................................5 Research Scope Diagram ............................................................................6 . Chapter 1: The Burden of Climatic Uncertainty at the Local Scale ... 7 1.1 . Industrial Revolutions and Urbanisation .........................................7 . 1.2 . Trepidation within Scientific Knowledge ..........................................9 . 1.3 . Scientific Climatology & Urban Planning .......................................11 . 1.4 . Considering Locality as a Bottom-Up Approach ...........................14 . 1.5 . Chapter 1 Synopsis ......................................................................18 . Chapter 2: Identity and Social Harmony at the Local Scale ........... 20 2.1 . An Emerging Spirit of Place ..........................................................20 . 2.2 . Social Space within the Contemporary City ..................................22 . 2.3 . Chapter 2 Synopsis ......................................................................33 . Chapter 3: The Lisbon Case ........................................................... 36 3.1 . The Modernisation of Lisbon.........................................................36 . 3.2 . The Emerging of Lisbonesque and Local Public Realm ...............41 . 3.3 . Modernist Lisbon and Contemporary Public Space ......................46 . 3.4 . Chapter 3 Synopsis ......................................................................54 . Chapter 4: Considering the Climatic Impacts on Lisbon ................. 56 4.1 . Emerging Portuguese National Strategies ....................................56 . 4.2 . Chapter 4 Synopsis ......................................................................63 . Chapter 5: Planning Public Space for a Changing Climate .............. 65 5.1 . Directing Smart Growth towards the Local Scale..........................65 . 5.2 . Applying Flexibility and Adaptability Measures .............................67 . 5.3 . Innovation and Invention ...............................................................71 . 5.4 . Chapter 5 Synopsis ......................................................................89 . Conclusion .................................................................................... 94 Bibliography ................................................................................. 99 IX . Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Table of Contents.

(10) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Problem & Justification of Theme If we define public space to be “a founder of urban form, the space between buildings, that configures the domain of socialization and ‘common’ experiences, and likewise of a collective community” (Brandão, 2011, p.34, author's translation), then we must “recognise the important role that public spaces play in extreme temperatures/combating climate change” (CABE and Practitioners, 2011). Public spaces are divided into different typologies, providing different uses, environments and functions. Yet these differentiations are intertwined by their role and function of sustaining urban culture, diversity and vivacity. Irrespective of their typology, their stature in contemporary cities now has to adapt to a shift in culture, one that now “plays a role in informing human practices connected with global environmental change” (Proctor, 1998, p.239). Although the term culture is hard to define, it is argued that it is “the way in which a community of persons makes sense of the world” (Gross and Rayner, 1985, p.2). This personification however is being burdened by new uncertainties, new preoccupations, and new phenomena in light of climatic changes. This sponsors an adjustment in culture that is entrenched with preoccupations that are “direct (e.g., acute or traumatic effects of extreme weather events and a changed environment); indirect (e.g., threats to emotional well-being based on observation of impacts and concern or uncertainty about future risks); and psychosocial (e.g., chronic social and community effects of heat, drought, migrations, and climate-related conflicts...)” (Doherty and Clayton, 2011, p.265). To accommodate a new shift ‘towards a culture of sustainability’ (Varadaan, 2010) in the present socio-economic ‘third modernity’ (Ascher, 2010 [2001]) there is a need to “understand present and future risk factor dynamics, and interiorizing their unpredictability in extreme scenarios, linking security with urban quality, and managing these risks through the design of cities and their public spaces” (Costa, 2011, p.88, author's translation). Ultimately, public space is sustained by people, and “People make the city, so [we] must support their ambition to realise unique opportunities, with soul and dignity…Self-organisation is the social base for sustainability. And sustainability is an inspiring theme for the creation of social organisation.” (Ven, Gehrels, Meerten et al., 2009, p.52). If we are to maintain a fluid and harmonised relationship between people and climate change however, we need to be “focused on the relationships of things, people, forces and processes and the 1. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Introduction.

(11) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. This thesis shall suggest that to enforce a fluid and harmonised relationship between people and climate change, we need to orientate our considerations upon the future – in that “the best way to predict the future is to design it” (Fuller, 2010).. Objectives of Thesis Hypothesis: The hypothesis of this research identifies public spaces as a social domain that fosters elements such as community and culture. In a warming climate, and within a new modernity, public spaces can be used to aid adaptability and the flexibility in uncertain horizons. General Objective: To research the contributions public spaces can have upon smart city preservation and growth – an identification of how local adaptability2 and flexibility3 are to enforce city quality and social harmony. By limiting the research scope to the Lisbon case, its public realm shall be dissected in terms of its chorological development and their possible future contributions to a warming city. Specific Objectives: 1) To understand the new forms of rationality in contemporary cities that has incorporated new planning measures such as bottom-up approaches and focus on the local scale. 2) To identify the phenomenological and psychosocial aspects of identity and social harmony that are invigorated and sustained by public spaces. 3) To analyse the modernisation of Lisbon and identify the progression, development and flourishing of existing contemporary Lisbonesque public realm. 4) To identify the predicted impending climate change impacts on Lisbon; and the emerging national climate adaptation agendas relevant to the local scale. 5) To comprehend how public spaces can aid adaptability and reflexivity within a warming city thus maintaining social communality and city quality.. 2. Term that describes the way and efficiency of the local scale is to adapt to obstacles in the long term. 3 Term that describes the way and efficiency of the local scale to be flexible enough to incorporate a range of issues in the short term. 2. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. moods and spirit of place…it is this relationship focus that is essential to any really sustainable building. The gadgets – from solar panels to composting toilets – are only bits and pieces. Essential, but not in themselves enough for wholeness and harmony.” (Day and Parnell, 2003, p.33)..

(12) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Chapter 1 shall discuss the implications of how climatic uncertainty and innovative planning approaches (such as bottom-up approaches) are now dealing with contemporary paradigms. There shall be an identification of how a new modernity has encouraged a change in planning and design approaches/models. By establishing that public spaces are a vital component within the local scale, this chapter launches the question of how do public spaces sustain a “domain of socialization and ‘common’ experiences, and likewise of a collective community”? (Brandão, 2011, p. 34, author's translation); and (2) how. 3. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Document Structure.

(13) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. To answer these two questions, Chapter 2 launches an investigation on how public spaces sustain ´domains of socialisation´ and ‘common experiences’. Consequently there is an in-depth analysis of the social and psychological phenomena that are embedded within local identity and social diversity. This aims at discussing the voices from numerous authors to demonstrate the intricate ingredients needed to attain local distinctiveness and uniqueness – both at the physical and social level. Chapter 3 undertakes an in-depth historical analysis of the modernisation of Lisbon and resulting contemporary spaces. This approach is based on understanding the contemporary composition of Lisbonesque public realm as “getting to understand a place-effectively is to understand the past that has formed it. Through this we [can] learn what the place is – it’s character (genus loci). In doing so, we begin to recognise what it needs to maximise its health, what it is asking for that design can fulfil.” (Day and Colquhoun, 2003, p.5). Following the detailed analyses of Lisbon’s existing framework, Chapter 4 looks at the expected climatic impacts upon Lisbon and national climate change agendas. This suggests the necessity of transposing local climate change scenarios onto Lisbon. This, however, requires the understanding of the expected impacts, evaluation of vulnerabilities; and the launching of a strategic adaptation plan (Prasad, Ranghieri, Shah et al., 2008). As part of this adaptation plan, and as a way for Lisbon to prepare for future horizons, Chapter 5 returns to the previously established question how can we continually support emerging and maturing life cycles in order to fortify our sense of ‘collective community’ and identity in uncertain, problematic, and eventful horizons? The final chapter focuses on how we can plan public spaces for climate change, not only as a measure to sustain impending impacts – but to maintain collective community through innovative, inventive, flexible and adaptable urban design. This chapter shall illustrate examples of international case studies that: (1) effectively accommodate climatic impacts by “understand[ing] present and future risk factor dynamics, and interiorizing their unpredictability in extreme scenarios, linking security with urban quality, and managing these risks through the design of cities and their public spaces” (Costa, 2011, p.88, author's translation); and (2) strengthens socio-economic dynamics and local identity for future timeframes.. 4. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. can they continually support emerging and maturing life cycles in order to fortify our sense of ‘collective community’ and identity in uncertain, problematic, and eventful horizons..

(14) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. The research for this project was carried out by synthesising different voices, opinions and concepts from varying spheres of study. In other words, this thesis is based on secondary research in the fields of urban design, urban planning, architecture and psychosociology. Considering the hypothesis of this thesis, various research questions are proposed in order to investigate its validity and legitimacy. The different chapters have been organised to analyse each question and to formulate individual conclusions that shall be congregated into a general conclusion at the end of the document. Independent of the chapter, a thorough scrutiny will be undertaken in three areas, those being, public spaces, climate change and Lisbon. Respectively, the initial interest that initiated this research was public spaces being a ‘city-void’ that serves as an assembly of social communality and representatives of culture. This spectrum of research however requires a further focus around the analyses of how future horizons shall influence the functioning of contemporary public spaces. This necessitates the comprehension of how the chronological evolutions of cities are transposing new socioeconomic cultures upon public spaces. This originates in unprecedented contemplations of present and future risk dynamics that are influencing the balance between objects, people, and ultimately, genus loci. This shall lead the research to consider new direct, indirect and psychosocial impacts that climatic change will have on people and the environment around them.. This desk research shall focus on the following research questions: 1. Being presented with new unprecedented forms of urban living and city growth – how are new forms of rationality and reflexivity affecting the practices of urban design and urban planning? 2. How do public spaces foster a ‘domain of socialisation’ in order to achieve a consensual representation of urban identity and vivacity? 3. Taking into consideration it’s chronological and historical development, how has the modernisation of Lisbon influenced the stature and quality of contemporary urban public realm? 4. How are Portuguese national strategies evaluating vulnerabilities, and launching respective adaptation plans in light of climatic impacts? 5. How can we plan public spaces for climate change as a measure to sustain impending impacts and maintain collective community through innovative, inventive, and adaptable urban design? . 5. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Methodology.

(15) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. . . 6. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Research Scope Diagram.

(16) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. The Burden of Climatic Uncertainty at the Local Scale. 1.1. Industrial Revolutions and Urbanisation. Having entered the twenty-first century, we are presented with new unprecedented patterns of urban living. The global economic, political, and social structures are having profound impacts on the way Man fashions his lifestyle and daily regimes. Understanding how cities have modified due to the industrial revolutions requires an analysis that spans over numerous topics. Due to the multidimensional, multifaceted, and intercultural nature of cities, it is becoming continually more difficult to specifically conclude the definition of what constitutes a city. Comparatively, sociologists and anthropologists are finding the definition of ‘culture’ continually more complex; just as urbanists, urban designers/planners and architects are continually being challenged by concepts such as identity and placemaking. The transformation of cities also implies changes over time and thus requires an appreciation of the historical development of the respective city (Thorns, 2002). The urban fabric of contemporary cities has resulted from the consecutive generations of settlers that have shaped their encapsulating landscapes. Consequently part of comprehending a city, is acknowledging that its present structure is not a piece of art that has frozen in time – instead, it should be seen as a continually evolving framework that has accommodated different chronological cycles of human existence (Ascher, 2010 [2001]). One of the largest accommodations to human needs can be found in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. The industrial revolution had an unprecedented and radical impact on cities, starting with the rapid shift of countryside settlement to city inhabitation. The first revolution ushered cities into a world where manufacturing and production was the driving force of most societies and communities (Thorns, 2002). As a result, this new era required the harnessing of new resources, and forms of energy to accompany the ever-growing number of factories. Furthermore, and additional to the requirement of new resources and energy, there was an essential need for labour. This served as a catalyst to rapidly build new residential locations that were also sharply differentiated by social class (Weber, 1889). With a new labour market in place, and with the expanding industrialised city, urbanisation was a dominant process in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As an example, in 1801, 85 per cent British inhabitants still lived in rural areas. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, more people lived in urban areas and almost one third lived in towns with a population over 50,000 (Mellor, 1977). As power and wealth shifted from older merchant cities to industrialised 7. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Chapter 1:.

(17) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Similar to the early years of the industrialisation and the impacts on urban life, the later years of the twentieth century saw another set of radical transformations. The industrialised “modern system of cities based around wealth created from large commodity production for a mass market place” transformed into a “new system based around the generation of wealth from information services which are globally rather than nationally organised.” (Thorns, 2002, p.4). Nevertheless, in an era of international cooperation and competition, local identities survived and strengthened the competitive advantage as increasingly the quality, as well as the quantity, of life has become an important global issue (Thorns, 2002). As the industrial age evolved, technological advancements and practices of capitalistic interest encouraged the de-industrialisation, reindustrialisation and expansion into new areas. The focus of this capitalist based society was to ultimately boost their competitive advantage – directing their priority towards efficient labour access, price of raw materials and closeness to escalating markets. The latest transformations on cityscape that deeply affected urbanisation patterns are the arrival of knowledge and information industries. This greatly diminished the necessity to be located close to human labour and/or raw materials. Raw material many times consisted of ideas and knowledge that were to be efficiently diverged through knowledge flows with the arrival of the World Wide Web. Contrariwise, authors such as Mike Featherstone, analyse the contextual and contingent aspects of change rather than the motives for change. In other words, these authors are less concerned with predicting the pattern of change and are more attentive towards the significance attached by individuals and groups to their place – such as their home, community, neighbourhood and city (Featherstone, 1991). The thrust of transformation in developed cities has shifted away from Fordism and mass production (the original catalyst for urbanisation) towards producer and consumer services. Thorns view is once again valid here as he describes the “growth of the urban as spectacle, the greater concentration upon urban place making and inter-urban competition over the growth agenda of consumption spaces” He then ends his argument stating that we must now understand how “our sense of self and identity is created within the contemporary urban world. The impact here of changing place/space relations and the question of whether we need to secure ‘place’ to create our sense of who we are has been taken up in both academic and policy debates” (Thorns, 2002, p.7). The third industrial revolution is argued to be the current era that combines communication technology and renewable energy measures. In an industrialized world catalyzed by the previous industrial revolutions, buildings and activities within them consume 8. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. ones, migration became a characteristic phenomenon in the nineteenth century..

(18) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. It is now appreciated more than ever that “things, including buildings, looked after, work better and use less energy as well as last longer... Moreover, buildings that result from this process revere both people and place, the life of nature and of human activities.” (Day and Parnell, 2003pp. 31-2). Day’s words particularly address flexibility and the life span of not only buildings but the place amongst them. Depicting once again on the concept of loci; the interconnection between space and their adaptation to future horizons becomes a vital consideration within a new socio-economic modernity.. 1.2. Trepidation within Scientific Knowledge. Comprehending the events and scenarios that loom in nebulous future horizons is a deliberation that is strongly imprinting upon the practices of urban design and urbanism. As a consequence, these spheres of practice are continually in pursuit of effective adaptation measures to diminish the impending climatic impacts on respective cities and territories. In the present socio-economic ‘third modernity’ (Ascher, 2010 [2001]), it is becoming increasingly recognised that adaptation to climate change is unavoidable. The new challenges and paradigms invigorated by climatic change are having a consequential impact on the way urban designers and urban planners conceive urban frameworks and infrastructure. Similarly, uncertainty is also having a significant impact on scientists and their ambition to disseminate future projections and estimations. The challenges that are being debated by global scientific investigations such as “issues related to the rate (and magnitude) of change of climate, the potential for nonlinear changes and the long-time horizons” (Dessai and Sluijs, 2007, p.5) are filled with substantial uncertainties. Inevitably, these uncertainties enclosed within the scientific arena, are further hindering both urban planners and designers to apply these ambiguous projections in their own interdisciplinary sphere of practice. The encumbrance of uncertainty, nonetheless, also originates the opportunity to strengthen the pledge between scientific investigation. 9. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. almost half the energy we generate and are responsible for half the carbon dioxide emissions (Foster, 2008). Sustainability, a concept that has grown in popularity in the last decade, requires our cities to challenge the balance of this equation. In other words, there is now an ever-growing preoccupation with the location and function of buildings that considers: (1) flexibility and life span; (2) orientation; (3) form and structure; (4) heating and ventilation systems and material choices; and (5) the impact upon the energy required to construct, maintain, and travel to and from the building..

(19) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. There is a distinctive line between the definition of risk and danger (Ascher, 2010 [2001]), danger constitutes a threat to safety, whereas risk portrays an eventual and less predictable danger factor. Consequently, considering uncertainty is to consider risk factors. In a new era of modernization, risk is becoming a continually important contemplation; this is complemented with an increasing efficiency of global information divergence and dissemination. Comparatively, this information flux is accelerating the shift in culture, one that is transposed upon society’s fears and insecurities in light of future risk factors. It can be hence argued that although conceptions of risk can be initially invigorated by scientific research and discovery, the consequential results of these outputs are socially constructed. In other words, the multiplicity of choice that individuals are confronted with raises a further differentiated life ‘profilisation’ and consumer choices (Ascher, 2010 [2001]). This increases the disparity of social groups or what Andersons describes as ‘imagined communities’ discussed in the next chapter of this thesis. Subsequently, these diversifications bring new paradigms and problems to existing socioeconomic dynamics. There is now a greater need to explore need, demand and expectation of users and the now expanded and individualised ‘market’. This strongly contrasts the dynamics of previous industrial revolutions where ‘limited rational’ and mass production were the key characteristics of modernisation and urbanisation. As the evolving socio-economic dynamics are encompassing a greater social differentiation; and the divergence in professional spheres of practice is mirroring this phenomenon. Factors such social differentiation and globalization are greatly increasing the pallet of professional specification and specialization. The origin of Urban Design was a direct result of a modernizing society that needed a compromise between the practices of architecture and town planning. In the twenty-first century, concepts of urban design have further diverged into the independent and recognized arenas such as placemaking. 10. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. and urbanism (Costa, 2011). This pledge yet requires the effective communication of continual scientific outputs between the private/public sectors with investigation centres. As an example of this effective communication between these entities, one can refer to the ACCSP that are internationally recognised for their: (1) “Investing in high-quality climate change research…”; (2) “Citation of [their] publications in the Assessment Reports produced by the IPCC”; (3) “Funding scientists to contribute to important bilateral and multilateral relationships between Australia and other countries”; (4) “Supporting Australia’s participation in international research priorities through such bodies as the World Climate Research Programme…”; and (5) “supporting the Global Carbon Project, which aims to develop a comprehensive policy-relevant understanding of the global carbon cycle.” (Pullman, 2012)..

(20) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. 1.3. Scientific Climatology & Urban Planning. It has been accepted for centuries that the physical design of cities affects climatic variables such as temperature, wind patterns, humidity, precipitation, and air quality. Consequently, these variables have direct consequences on the liveability in contemporary cities (Hebbert and Webb, 2007). This suggests that urban form can enhance or reduce the quality of urban life, thus suggesting the prominence between spheres such as urban design and climatic adaptation. Previously, urban climatologists dwelled on anthropogenic issues that were also well acquainted by urban planners. Amongst others, these issues shared by the two spheres of practice were: street orientation, street width-to-height ratios, building spacing, architectural detailing in streetscapes, heat-reflectiveness from materials, the location of street trees, parks and water spaces, and finally, the effects of traffic (Givoni, 1998; Erell, Pearlmutter and Williamson, 2011). Subsequently, streetscape became a field that shared contributions from climatological considerations and design concepts. Within this field of investigation, various phenomena were objects of study such as street dimensions, the componential characteristics of the materials, the angle of the street and its geometry that determined the amount of sun-light and loss of micro-heat during the night. With the aid of technology, investigations supported more sophisticated studies such as “integrating design concepts and climatic effects with biometerological variables so human comfort levels can be estimated under different climate scenarios and design settings” (Matzarakis, Mayer and Iziomon, 1999). Table 1 - Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) ranges within different grades of thermal perception by human beings and physiological stress on human beings4 PET. Thermal Perception. Grade of Physiological Stress. ≤ 4ºC. Very Cold. Extreme Cold Stress. 4ºC. Cold. Strong Cold Stress. 8ºC. Cool. Moderate Cold Stress. 4. Table based on an internal heat production of 80 W (from the human being) and a heat resistance of clothing of 0.9 clo. These figures are established by Matzarakis and Mayer as a baseline average. 11. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. This is a direct result of rationality accompanying an ever growing society of individualization, especially one that is facing impending risks masked by the future..

(21) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Slightly Cool. Slight Cold Stress. 18ºC. Comfortable. No Thermal Stress. 23ºC. Slightly Warm. Slight Heat Stress. 29ºC. Warm. Moderate Heat Stress. 35ºC. Hot. Strong Heat Stress. 41ºC. Very Hot Extreme Heat Stress Source : (Matzarakis and Mayer, 1996). Contemporary organisations such as the IAUC have undertaken these genres of studies in order to ensure the maintenance of urban ecosystems, and human comfort in all sorts of events - including in hazardous scenarios. The objective of the organisation5 is another exemplar demonstration of the accord between scientific investigation pertaining to climate issues and urban planning. Contrastingly, although the scientific exploration of urban climatology advanced in the mid twentieth century, the same could not be said for its practical application. Due to a variety of possible reasons (such as the decline in pedestrianism) urban planning became less climatesensitive after the 1950’s. As a consequence to this discrepancy, climatic factors were poorly understood and regulated. This inevitably affected the composition of urban frameworks where: “In the name of traffic flow streets were often widened and sidewalks narrowed to the detriment of outdoor air quality. Small city blocks were consolidated to allow the construction of large-scale climate controlled buildings, blocking air circulation or creating man-made wind tunnels. The higher heat absorption capacity of man-made materials, such as asphalt and cement, boosted urban heat island effects. The impervious surfaces of buildings, roads and parking lots accelerated storm-water run-off and flood risk. Tree removal deprived streets of pollution filters and exacerbated outdoor temperature extremes…” (Hebbert and Webb, 2007, p.124) During the latter twentieth century, the communication between climatologists and urban planners continually decreased. Scientists specialising in city weather patterns knew that if these trends continued, there would undeniably be adverse effects on the liveability and quality within urban frameworks. Amongst others such as Chandler, Bitan, Giovani, the German climatologist – Helmut Landsberg stated that “the heat island is a reflection of the totality of microclimate changes brought about by man-made alterations of the urban surface.” (Landsberg, 1981, p.84). With the aid of institutional. 5. Amongst others, the IAUC have technical interest and responsibility in: (i) ‘climatology and meteorology of built-up areas’; (ii) ‘urban air quality’; (iii) ‘wind turbulence in the city’; and (iv) ‘micro-scale processes and patterns associated with urban landscape elements (buildings, canyons, parks, roads etc)’ Halpin, S. (2012). "International Association for Urban Climate." Retrieved 05/07, 2012, from http://urbanclimate.com/wp3/about-us. 12. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. 13ºC.

(22) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Escalating now from the local scale to the global scale, one can note a significant difference in climate change awareness and regulatory practice. The IPCC and the UNFCCC have had a strong impact on decision makers and policy frameworks and invigorated the creation of action plans in many leading countries. Nowadays carbon mitigation and/or adaptation to global warming are part of many international agendas with monthly initiatives being disseminated throughout the global scientific community. Although this global dissemination is imperative, it is argued that it is frequently “focussed [on] the exposure of cities to hazards that have a huge impact but low frequency. It has little to say about the high-frequency and micro-scale climatic phenomena created within the anthropogenic environment of the city.” (Hebbert and Webb, 2007, p.126). Accordingly, this has diminished the comprehension of mitigation and adaptation at the local scale. Local factors such as wind patterns, spatial patterns of sunlight exposure, pollution and its dispersal through breezes are overlooked in regional weather models. Yet it can nevertheless be argued that although less serious, these phenomena also have a ‘continual’ affect human comfort, health, and ultimately, quality of life.. The progression of scientific research and outputs are changing the way cities are being maintained and conceived. Hence the realms of scientific research are aiding the elaboration of new decisions in light of new paradigms that cities are to face in uncertain horizons. This progression is substantiating that available resources to attain a determined result can be variable in uncertain scenarios. This has radically contributed to the diversification of rationality with regards to the adaptation of means to a determined end. This theory has had an invigorating and fundamental contribution to the development of ongoing scientific research. The next chapter discusses the mental organization and ones train of thought when experiencing encapsulating contexts. The progression of research in this area of cognitive science equally opens new perspectives and paradigms. This area of investigation has expanded the understanding of experience and perception, allowing an invigorating insight into the comprehension of human thought processes. Consequently, there is an ever-growing attentiveness with how the mind grasps it’s surrounding; stimulating fairly recent focuses such as Environmental Psychology and Eco-Psychology.. 6. Including the: World Meteorological Organisation; the United Nations Environment Programme; the International Society for Biometeorology; the International Federation for Housing and Planning and the Confédération Internationale du Bâtiment. 13. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. networks6, the scientific community made extensive efforts post World War 2 to caution urban planners to anthropogenic climatic changes at the local scale. Nevertheless the warnings to climatic awareness were prominently ineffective (Hebbert and Mackillop, 2011)..

(23) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. It is undeniable that the challenge of global climate change has launched contemporary cities into a new era of unprecedented paradigms. On the other hand, it is also a fact that only recently are urban planners, urbanists and urban designers beginning to consider the full spectrum of climatology and its effects on the local scale.. 1.4. Considering Locality as a Bottom-Up Approach. Although climate change and uncertainty go hand in hand, climate change adaptation is not a ‘vague concept’ (Bourdin, 2010). Inversely, it is the concrete bond within specific localities that substantiates its preciseness (Costa, 2011); nevertheless, this means that climatic “effects cannot be downscaled from a regional weather model, they are complex and require local observation and understanding.” (Hebbert and Webb, 2007, p.125). So far, a considerable amount of research relating to ‘locality’ has been carried out through a top-down approach. This concentrates on methods of impact prediction through global models as a starting point to anticipate climate change scenarios. As these global models have little regional or local specificity, there “has been a growing interest, however, in considering a bottom-up approach, asking such questions as how local places contribute to global climate change, how those contributions change over time, what drives such changes, what controls local interests exercise over such forces, and how efforts at mitigation and adaptation can be locally initiated and adopted.” (Wilbanks and Kates, 1999, p. 601).. 14. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. As already mentioned, the diverse and seamlessly boundless theory of post-modernism raised a lot of discussion and criticism. Amongst many others, one of the topics of debate had to do precisely with the amount of diverse scientific research and theory. Considered as the ‘crises of reasoning’, the vast spectrum of knowledge was regarded as ‘over-assorted’ and many times contradictory. Yet this thesis argues that this is another clear demonstration of an expanded and a further rehearsed rationality. This expanded rationality is the gearing of a further reflexive society and thinking that encourages vital inquisitions that were never pondered before. An effective example of these new investigations tackles issues such as uncertainty, urban complexity, and societal chaos. Day addresses this very new form of thinking, one that does not deny margins of error, yet portrays a very valid point when contemplating uncertain horizons – “Even if we’re wrong about how we picture the future developing, we’re unlikely to be as far wrong as if we had never considered it.” (Day and Parnell, 2003, p. 33)..

(24) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. By shifting our glance at the local scale, and thirsting to understand how these spaces can contribute to a global climate change, we are also presented with new contemplations. Climate change presents urbanists and urban designers with new choices, and in turn, their decision shall affect the efficiency of how well a town or city can adapt. Good design solutions should aim at enhancing sense of place and identity (CABE, 2008) instead of “an after-the-fact cosmetic treatment of spaces that are ill-shaped and ill-planned for public use in the first place.” (Trancik, 1986, p. 1). Institutions such as CABE believe that adapting to climate change means making towns more resilient, and that well designed and flexible public spaces are the best tool in doing so (CABE and Practitioners, 2011). This by no means discredits that some of the catalyst propulsions for global change operate at a global scale7, yet it can also be argued that comparatively important socio-economic dynamics also arise at the local scale (Wilbanks and Kates, 1999). Focusing on the question of how the local scale contributes to global climate change, consequently, requires comprehending the “important role that public spaces play in extreme temperatures/combating climate change.” (CABE and Practitioners, 2011). This analysis nurtures further inquiries that can be addressed through a bottom-up approach: (1) how do public spaces sustain a social “domain of socialization and ‘common’ experiences, and likewise of a collective community”? (Brandão, 2011, p. 34, author's translation); and (2) how can we continually support emerging and maturing life cycles in order to fortify our sense of ‘collective community’ and identity in uncertain, problematic, and eventful horizons?. Once engrained at the local scale, the analytical discernment upon public spaces must be orientated towards people. In other words, being appreciative that public space is sustained by people and that “people make the city, so [we] must support their ambition to realise unique opportunities, with soul and dignity… Self-organisation is the social base for sustainability. And sustainability is an inspiring theme for the creation of social organisation.” (Ven, Gehrels, Meerten et al., 2009, p.52). It is indubitable that climate change requires us to. 7. Amongst others, the aid of global financial entities and the green-house gas composition of the atmosphere. Wilbanks, T. J. and R. W. Kates (1999). Global Change in Local Places: How Scale Matters Climatic Change. The Netherlands. 43: 601-628. 15. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. Similarly, and with the limitations of the top-down method being progressively established, scientific research endeavours are being carried out to improve the adaptability of global climate models. This has encouraged the climatic models to move downscale and to interchange between scales more efficiently and cohesively. As a consequence, there has been a resulting downscale analysis of emissions, climate change models and climatic impact estimations..

(25) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. According to Thomas Joseph Doherty and Susan Clayton8’s article on the ‘Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change’, they portray three classes of psychological impacts: (1) “direct (e.g., acute or traumatic effects of extreme weather events and a changed environment); (2) indirect (e.g., threats to emotional well-being based on observation of impacts and concern or uncertainty about future risks); and (3) psychosocial (e.g., chronic social and community effects of heat, drought, migrations, and climate-related conflicts...)” (Doherty and Clayton, 2011, p.265). Similarly to the burdensome weight that uncertainty has on scientists, uncertainty also encumbrance’s socio-economic dynamics. Following the root of indirect psychological impacts; concerns and uncertainty regarding the future can have deep impacts on psychosocial wellbeing. Just as there needs to be physical resilience measures that address climatic impacts, there is also a need to promote emotional resiliency. This emotional resiliency is one that shall fortify and maintain identity during both emotional and physical impacts. Ultimately, if we are to maintain a fluid and harmonised relationship between people and climate change (and in this way tackling problems originating also from uncertainty), there is the need to be “focused on the relationships of things, people, forces and processes and the moods and spirit of place … it is this relationship focus that is essential to any really sustainable building. The gadgets – from solar panels to composting toilets – are only bits and pieces, Essential, but not in themselves enough for wholeness and harmony.” (Day and Parnell, 2003, p.33) The passage into the twenty-first century raised multiple reflections upon the unprecedented progressions undertaken in the twentieth century. Modernization is, and always has been, a source of discussion and many times of hostile reactions. Yet in the last thirty years, most discussions have been focused around post-modernism, a concept “that joins a category where everything can be fit into” (Ascher 2001, p.32, author’s translation). Philosophers, sociologists, architects, and urbanists are hence deliberating on a vastly interdisciplinary society, where the professional, social, economic, and political boundaries are becoming ever more undistinguishable. It is suggested by authors such as Ascher that modern society is liberating. 8. Licensed psychologists that specialise in teaching and researching human relationships with the natural world, and environmental conservation. Also the Editor-inChief of the journal Ecopsychology and member of the American Psychological Association Climate Change Force. 16. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. “understand present and future risk factor dynamics … linking security with urban quality, and managing these risks through the design of cities and their public spaces” (Costa, 2011). Yet, and without diminishing the importance of risk management, there additionally needs to be an understanding between social dynamics and climatic adaptation..

(26) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Returning to Ascher, rationalization is one of the base processes for modernization as it continues to have a deep interrelationship with collective and individualistic actions and decisions. It leads a “’reflexivity’ of modern social life that can be defined as ‘the constant revision and examination of social practices, in light of the information respective of those very practices’” (Ascher, 2010 [2001], p.33, author's translation). What the author means by this is that using previous knowledge to study social practices is no longer sufficient, there also needs to be a permanent reexamination of communal interactions. It can be further argued that each individual, just as each community, shall be confronted with an increasing amount of dissimilar situations and/or circumstances. As Mankind faces the future, there will an increasing amount of scenarios that cannot be resolved by looking at past experiences or resolutions. This raises the imperativeness of reflexivity, one that promotes the creation of appropriate solutions that address future issues. Consequently, the ‘limited rational’ of continually relying (and depending) on typical practices or procedures is to be diminished in the modernizing city. This reflexive thinking is further ushered by an ever developing social complexity, scientific research and technological progressions.. 17. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. itself from a period of limited and simplistic rationality. Technically speaking, the envisaged characteristics of modernity are shifting, and this is having an invigorating impact on modern culture. Although culture is a difficult term to decipher, this thesis believes that it is “the way in which a community of persons makes sense of the world” (Gross and Rayner, 1985, p.2). In a ‘world’ that faces inevitable climatic impacts, contemporary cities must now adapt to a shift in culture, one that now “plays a role in informing human practices connected with global environmental change.” (Proctor, 1998, p.239). This has launched society into what is described as a new socioeconomic modernity. The steam-powered modernization of the first industrial revolution and the petrochemical mass modernization of the second industrial revolution – have now given way into a new form of modernity. A modernity that is reflexive, individualistic, and socialeconomically orientated towards the present and the future..

(27) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. Chapter 1 Synopsis. . As discussed in this chapter, the words of Thorns play an important role in establishing that our ‘sense of self’ and identity face new paradigms within the modern city. There is now a preoccupation in maintaining a ‘secure’ place whilst exposed to the continual alterations our cities are exposed to. Accompanying these changes in place/space relations, are new forms of thinking, a more elaborated rational that further considers the flexibility and the life span of cities. Amongst others, professions such as urban design and urban planning are hence now tasked with considering the future implications of their projects, plans, and proposals. This infers the analytical eye towards considering paradigms that were scarcely considered in previous centuries. In other words, and in what is considered to be a ‘third modernity’, we are presented with: (1) New socio-economic paradigms that are resultant of a maturing human rationality demanding constant revision and examination of his social practices; (2) considering the future as eventful horizons, requiring the dissemination of future projections and estimation that are grounded by the continual outputs of scientific endeavors. These factors present new paradigms when we are to consider the public spaces within the modern city, firstly, there is a need to acknowledge an emerging 18. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. 1.5.

(28) Faculty of Architecture – Technical University of Lisbon Masters in Architecture with Specialisation in Urban Planning Final Project / Dissertation A. Santos Nouri. These unprecedented paradigms that are presented upon contemporary cities however raise an array of new opportunities. Such that, there is now a keen interest both at user and professional levels to embark on maintaining city quality and public realm exuberance both now and, more importantly, in the future. To prepare for climatic impacts and being presented with issues such as uncertainty, there is now a more pivotal focus on the local scale. Although not a new concept, the focus on the local scale is a vital tool when challenged with unclear future impacts upon cities. This bottomup perspective is argued to be a way in which we can defy uncertainty and simultaneously focus on public spaces, an unblemished representation and symbol of city liveliness and quality. The next chapter shall consequently dissect various secondary resources to establish how these spaces foster a collective representation of people and fortify an underpinning representation of urban quality and vivacity.. . . 19. Climate Change Implications on Present and Future Public Space ‐ Modern Day Paradigms for Urbanism and Urban Design. cultural shift that considers aspects of sustainability orientated towards establishing well-being in the future. Secondly, overcoming uncertainty and not permitting future ambiguity to hinder professionals to continually challenge aspects such as future climatic changes..

Imagem

Documentos relacionados

The authors came to a consensus as to which studies met the inclusion criteria and submitted these to the first author (S.Z.) who then independently reviewed

“ De facto, viver (n)a universidade não é apenas realizar exames e assimilar um arsenal teórico/prático como garantia de um futuro profissional; viver implica pensar, sentir

Ao defender a transmissão de conhecimento entre professor e estudante em sala de aula, Ausubel (2003) se refere ao processo de ensino pela aprendizagem

Analisando apenas os valores apresentados para as relações do modelo entre as três variáveis latentes, a Qualidade Total exerce influência negativa na Performance, ao contrário

Uma das explicações para a não utilização dos recursos do Fundo foi devido ao processo de reconstrução dos países europeus, e devido ao grande fluxo de capitais no

O cliente é a pessoa mais importante de toda e qualquer empresa, é ele quem faz com que uma empresa tenha sucesso ou fracasso, todavia, o excesso de ofertas e preços faz com que

Com o mercado globalizado, as empresas buscam cada vez mais competitividade, por meio do planejamento da produção, este artigo apresenta um estudo de caso sobre arranjo

tations could be introduced into iPSCs using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and HDR-mediated genome editing to generate in vitro models of human disease.. 72 have