C

LINICAL

AND SEROLOGIC STUDY OF CUBAN

CHILDREN WITH DENGUE

HEMORRHAGIC FEVER/DENGUE SHOCK

SYNDROME

(DHFIDSS)~

M. G. Gzxw.zh, 2 G. Koz~rZ;~ E. Marthex, 4 J. Bravo, 5

R. River&, 6 M. Soler, 5 S. VZzquez, 5 and L. Morier 5

B

ACKGROUND

Halstead, in a review of the literature (l), gives an account of pre-

1980 data on dengue hemorrhagic fe-

verldengue shock syndrome (DHFIDSS)

in different parts of the world. Al- though the pandemic character of this problem was pointed out in earlier works (I), from the 1950s until 1981 it

remained confined to South-East Asia, where it affected mainly children.

Following a small outbreak of classical dengue in 1945 (2), no dengue virus activity of any kind was recognized in Cuba until 1977, when an epidemic

’ This article will also be published in Spanish in the 2 B&tin de la O&iza Sanitanb Panamericana, vol. 2 103, search program on dengue hemorrhagic fever carried 1987. The study reported here was part of a re-

.

s out by the Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine s

in Havana, Cuba, with financial support from the In- ternational Development and Research Center in Ot- .x tawa, Canada.

G PI

a * Chief, Arbovirus Department, Pedro Kouri Institute 3 of Tropical Medicine, Havana, Cuba.

3 Director, Pedro KourI Institute of Tropical Medicine, Havana, Cuba.

4 Vice-Director, William Soler Children’s Hospital,

occurred that was caused by dengue-1 virus (3). This epidemic, characterized by a clinical picture of classical dengue, lasted into 1978; thereafter, dengue-1 remained in circulation with low ende- micity (4).

From May to October 1981 another epidemic occurred that was caused by dengue-2 virus. This outbreak caused cases with severe clinical pictures

of DHFlDSS (5), In all, 344,303 cases

were recorded, including 10,312 that were severe and 158 (101 in children

and 57 in adults) that were fatal (6). Al- though the afflicted included both chil- dren and adults, the highest incidence of severe and fatal cases occurred among children four and five years old. No se- vere or fatal cases occurred among chil- dren one or two years old (6).

A campaign to control and eradicate the vector mosquito A.&es

aegypti followed on the heels of the out- break and allowed the disease to be eliminated in a little over four months. Since then the vector house indices have

Havana, Cuba.

270

s Research Worker, Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine, Havana, Cuba.

remained at very low levels (on the order of O.OOl), and no clinical cases of den- gue have been confirmed since 10 Octo- ber 1981. This circumstance has facili- tated retrospective studies that have provided reliable data.

The work described here ex- amined the clinical picture found in a group of children clinically diagnosed as having DHFIDSS. It also sought to deter-

mine whether secondary-type dengue infections in these children placed them at relatively great risk of developing the severe clinical form of the disease.

As far as we know, this is the first well-documented study of the dis- ease in a Caribbean setting and popula- tion; hence, it may be considered a starting point for description of DHFl DSS in the region, as well as a source of very useful data for comparison with current information about the disease in other regions.

M

ATERIALS AND

METHODS

The study sample consisted of 124 children diagnosed as having

DHFIDSS, grades III and IV, according

to the criteria of the WHO Advisory Committee on DHF (7). All of these children were admitted to the Centro Habana and William Soler pediatric hospitals (two large health centers) dur- ing the 1981 epidemic. A blood sample was taken from each child in April 1983, 18 months after the epidemic ended, and the child’s clinical record was re- viewed. The blood was collected by fm-

ger-tip puncture on two Nobuto type A filter papers (Toy0 Roshi International, Tokyo, Japan). Each sample was dried, placed in a sealed plastic bag, and stored at - 20°C until antibody tests were per- formed. The dried blood was then eluted to produce a serum dilution of 1: 30 (8).

Each sample was tested for antibodies to dengue-1 and dengue-2 by plaque reduction neutralization us-

ing LLCMK~ cells (9). The virus strains

employed were isolated in Cuba during the 1977 (dengue-1) and 1981 (dengue- 2) epidemics (3,s). A child was deemed to have a primary infection when the test showed over 50% plaque reduction against only one dengue virus, and a secondary infection when the test showed over 50% plaque reduction against both dengue viruses.

RE

SULTS

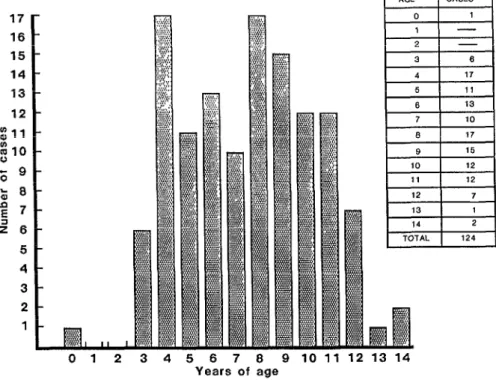

One hundred twenty-two children (98 % ) were found to have neu- tralizing antibodies against both den- gue-1 and dengue-2. Figure 1 shows the age distribution of the 124 patients studied (it should be emphasized that

only one patient was less than 3 years T old). The youngest child, who was four 2 months old, exhibited a primary-type

antibody response to dengue-2. 2 z: The bulk of the study chil-

dren were four to 11 years old. As Table

2

1 shows, the group consisted about equally of boys and girls. However, the

g . Table 2 data indicate that 86% of the G children were white, 8% were mulatto, Q and only 6 % were black. Comparison of

these figures to the ethnic distribution

,i 8 of the Cuban population indicates that

the frequency of severe disease was 8 significantly higher among whites

FIGURE 1.

17 16

15 14 13 12 g11 g10 % 9

k 6 2 7 z 6 5 4 3 2 1

Years of age

TABLE 1. Sex distribution of the study children.

Study children

Sex NO. (%I

M 60

F 64

Regarding the clinical disease symptoms exhibited, fever-either alone or accompanied by other manifes- tations such as vomiting or nausea-was the most common reason for hospital- ization .

The study subjects were gen- erally hospitalized at least 24 hours be- fore shock occurred. (In most cases

shock was observed four or five days af- ter the onset of symptoms.) The period of hospitalization ranged from five to 15

days, with most of the children being hospitalized for six to 10 days.

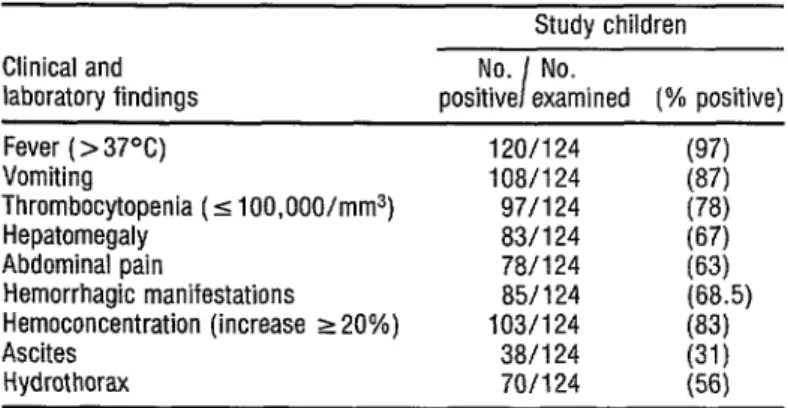

Table 3 shows the main clini- cal and laboratory findings. Clinically, the children showed high rates of fever, vomiting, and hepatomegaly. Manifes- tations such as hydrothorax and ascites were frequently found in the children with severe clinical pictures. Throm- bocytopenia was observed in 78% of the patients and hemoconcentration in 83%.

TABLE 2. Racial distribution of 123 of the study childrena

Race

Study children

No. (%I

Racial distribution of the general Cuban populationb

WJ)

White Mulatto Black Asiatic

Total

106 (66) 10

7

12:

I:; 1%“’ (0.1)

(100) (100)

a The race of one of the 124 study children was not recorded. b Eased on the 1981 census.

TABLE 3. Principal clinical and laboratory findings obtained from examina- tion of the 124 study children.

Study children Clinical and

laboratory findings

No. No. I

positive examined (% positive)

Fever ( > 37°C) 120/124

Vomiting 108/124

Thrombocytopenia (5 100,000/mm3) 97/124

Hepatomegaly 83/124

Abdominal pain 78/124

Hemorrhagic manifestations 85/124

Hemoconcentration (increase ~20%) 103/124

Ascites 38/l 24

Hydrothorax 70/124

g:;

(78)

;:;I (68.5)

(83)

(31)

(56)

TABLE 4. The frequency of the various hemor- rhagic manifestations found in 85 of the 124 study children.

Study children

Hemorrhagic No. No.

I

(%

manifestations positive examined positive)

Petechiae Hematemesis Melena Ecchymoses Epistaxis

62/124 37/124 lo/124

g/124 I;;

11/124 (9)

subjects), the most frequent manifesta- tions being petechiae and hematemesis. Regarding possible associations with asthma (Table 5), 21.5 % of the chil- dren were found to have a personal his-

toy of asthma, while 36% were found

TABLE 5. The proportions of 88 study children ex- amined who were found to have a personal or family

history of asthma. .

4; t3

Children with personal or D

family asthma histories 8

Asthma c

histories No. W)

Personal 19 (21.5)

to have a family history of this ailment. (Asthma is typically found in 11% of the Cuban child population.)

D

ISCUSSION

AND

CONCLUSIONS

DHFIDSS is observed mainly

in South-East Asian and Western Pacific areas where two or more dengue virus serotypes are circulating in an endemic fashion (1). The first studies conducted in Thailand by Nimmanitya et al. (1969) and Halstead et al. (1970) (10, 11) showed that secondary-type infec- tion constituted a risk factor for devel- opment of DHFIDSS. However, there were a few reports of severe clinical pic- tures in patients suffering from primary infections (12, 13).

Because only two dengue vi- rus serotypes have been circulating in Cuba over the last 40 years (during the

1977 and 1981 epidemics) (3, 51, retro- spective serologic studies in patients with clinically diagnosed DHFIDSS

grades III and IV can help to determine whether or not secondary-type infection was a factor predisposing to severe evo- lution of the disease in such patients. Of the 124 children with DSS included in this study, all but two yielded a second- ary-type antibody response.

Rosen (1982) (14) has pointed

out the convenience of comparing the prevalence of primary and secondary an- tibody responses in Cuban patients who suffered from DHFIDSS with the preva- lence to be expected on the basis of the share of the population infected with

dengue-1 virus in 1977. In this regard, Cantelar et al. (1981) (13) have reported

that after the dengue-1 epidemic, 44.46% of the Cuban population had hemagglutination-inhibition antibod- ies to dengue virus. If this figure is ac- cepted as valid, then it appears that the percentage of DHFIDSS study subjects with dengue-1 antibodies (98%) was over twice that found in the general population. This finding therefore tends to confirm the importance of pre- existing antibodies as a risk factor. Simi- larly, Diaz et al. (16) studied a group of

104 adult patients in whom DHFlDSS

was diagnosed during the same epi- demic; only two patients showed pri- mary-type infections.

It is also important to note that of the 101 fatal DHFlDSS cases in

children, no case was found in any child one or two years old. Secondary-type in- fections would be very difficult to ex- plain in such children, because they were born principally in 1979 or 1980, years when the circulation of dengue-1 virus in Cuba was very low (17) I

In a pattern similar to that re- ported in the literature (18) , most of the

afflicted study children were four to 11 years old. It also seems relevant to note that severe disease cases were found in adults during this epidemic, an unusual development probably ascribable to the fact that Cuban adults as well as chil- dren were susceptible to a second den- gue infection (6).

All of this calls attention to the four-month-old infant who was one of the two study subjects with a primary dengue-2 infection. In this case the de- velopment of shock could be explained by the presence of passive maternal anti- bodies (18), although this circumstance

could not be confirmed, since it was not possible to take a blood sample from the mother.

The occurrence of four other fatal cases in children under six months old might be explained the same way (this could not be confirmed for lack of blood samples from their mothers). In any event, the occurrence of severe dis- ease during the first six months of life in the Cuban epidemic (6) differs from what has been seen in South-East Asia, where cases typically occur between six and 12 months of life (18).

This difference appears re- lated to maternal antibody titers. In Cuba, where dengue virus circulation has been restricted to two serotypes in two epidemics, the level of maternal an- tibodies should be lower than the level of maternal antibodies in endemic areas where several dengue virus serotypes are permanently and simultaneously circu- lating. Hence, antibody levels appropri- ate for contracting dengue and develop- ing severe symptoms could have been reached in our newborns at an age sev- eral months younger than that when those same levels were reached in chil- dren from endemic areas of South-East Asia and the Western Pacific Islands.

A preponderance of DHFIDSS

in females over four years old has been documented by Halstead (I, 18,J. This preponderance had been ascribed to a stronger immunologic response among females than among males. No such preponderance was seen in our study, however, the numbers of boys and girls with severe symptoms being about equal. Similarly, no female preponder- ance was found by Martinez et al. (1984)

(19) among 249 children admitted to the William Soler Hospital with DIG/ DSS during the 1981 epidemic, nor was any found among the 101 children who died of DHFlDSS (‘6).

It is of course possible that so- cial practices or other factors could pro- duce greater exposure to the virus among girls over four years old in the

areas with endemic DHFIDSS. Such ex- posure could explain the higher preva- lence of the disease among females in this age group.

Although it has not been possible to correlate DHFIDSS with racial

factors, it had been known that the prevalence of dengue infection among non-natives is much lower than the prevalence among natives in South-East Asia (1). However, this has been corre- lated with less exposure of the non- native population to the Aedes aegypti vector. Furthermore, it had not been possible to report on severe disease pat- terns among whites and blacks (al- though a 1967 report by Russell et al. (20) described a fatal DHFIDSS case in a white U.S. child), because severe cases were generally restricted to areas where those racial groups are scarce.

In our study, the preponder- ance of DHF~DSS cases in white children was found to be statistically significant when compared to the ethnic distribu- tion of the Cuban population at large. This pattern, which parallels that found in both adult patients and subjects with fatal cases (21), indicates that the white race might be especially susceptible.

Conversely, in black popula- tions the frequency of DHFlDSS was much lower than what would have been s expected. At present there are no find- 2 ings that rule out the possibility that the 5 black race may exhibit a certain resis- tance to the disease. In Africa, dengue

2

epidemics are infrequent, although the virus is quite frequently isolated from g

vectors (22, 23). .

< Q 3 4 E 3

Studies conducted in our lab- oratory (24) have demonstrated a faster multiplication of dengue-2 virus in cul- tures of human peripheral blood mono- cytes from white donors when these were treated with subneutralizing con-

centrations of antibodies.

Halstead (1979) (25) has said that microbial stimuli such as those in- dicated by a history of previous infec- tions, chronic disease, and metabolic disorders would play a significant role in enhancing dengue infection in man. Among our group of DHFIDSS patients, a personal or family history of bronchial asthma was found at a significantly higher frequency than it was found among the child population at large. In addition, it has been found that diabe- tes mellitus was a risk factor for develop- ment of fatal DHFlDSS cases among Cu- ban adults (6). These and other as yet unidentified risk factors are also likely to be present in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific Islands.

In this regard, it is important to note the results obtained by Wiharta et al. (X9, who demonstrated increased dengue virus multiplication in cultures of human peripheral blood monocytes when these were pretreated with bacte- rial or parasitic components. This rate of multiplication was higher when subneu- tralizing concentrations of dengue virus antibodies were added to the cultures. h

5

This suggests that parasitic or bacterial infections, along with secondary-type .

3 dengue infection, could increase the risk G of developing severe symptoms. Study *g of this matter in areas with endemic DHFIDSS would be of interest.

3 2

Following sudden onset with fever and vomiting in the 1981 epi-

2 n, demic, shock typically occurred on the

276

fourth or fifth day of the disease-being preceded in many cases by abdominal pain and petechiae. Contrary to what was observed in adults (16), the pres- ence of shock in children did not usually lead to a fatal outcome when rapid and appropriate treatment was applied (27, 28).

In general, the laboratory data and hemorrhagic manifestations found among our study children were similar to those found among 13 chil- dren with fatal DHFIDSS during the epi- demic (29), although the symptoms were more marked among the latter.

Among other things, 92% of the chil- dren with fatal cases had upper digestive bleeding, and all of them had thrombo- cytopenia and hemoconcentration.

The WHO Technical Advisory Committee on Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (7) includes among the diagnostic criteria for DHFIDSS the presence of thrombocytopenia (equal to or lower than 100,000/mm3) with concurrent hemoconcentration (an increase of 20 % or more). However, our study found that thrombocytopenia and hemocon- centration were not reported in 22% and 17% of the patients, respectively. This could have been due to the early treatment established for our patients- most of whom were hospitalized 24 hours before shock occurred-or to pro- curement of laboratory blood samples after normal platelet and hematocrit levels had been restored.

in 87.5 % of a group of study children with DHF. In 72 fatal cases reported in children during the Cuban epidemic, thrombocytopenia was documented in 97% of the cases and hemoconcentra- tion in 96% (32).

All patients in whom severe disease was suspected were hospitalized early. This measure permitted early and appropriate treatment, and also made it possible to learn about clinical evolu- tion of the condition. In general, this early hospitalization, combined with intensive treatment, made it possible to keep the number of fatal cases to a minimum.

In general, where cases had a fatal outcome appropriate measures taken to prevent or control shock were not as successful as expected. In these cases, homeostatic changes appeared so rapid and profound that it was not pos- sible to save the patient.

A

CKNOVULEDGMENT

The authors are grateful for the assistance and advice of Professor S. B. Halstead.

S

UMMARY

A study was made of 124 children afflicted with dengue hemor- rhagic fever / dengue shock syndrome

(DHFIDSS) grades III and IV during the

1981 dengue-2 epidemic in Cuba. Nearly all (98 % ) of these children

yielded a secondary-type serologic re- sponse to the neutralization test, indi- cating prior dengue-1 infection. The composition of the study group indi- cated that children between four and 11 years old were those most likely to be af- flicted with severe symptoms.

No predilection for boys or girls emerged, but white children ap- peared significantly more likely than black or mulatto children to develop

DHFIDSS.

In most cases, shock occurred four to five days after the initial onset of symptoms, often being preceded by ab- dominal pain. Fever, vomiting, and hepatomegaly were the clinical manifes- tations most commonly found among the study children. Hemorrhagic mani- festations were found in 85 (68.5 %) of the study children, petechiae and hema- temesis being predominant. An unusu- ally large percentage of the study chil- dren (2 1.5 % ) were found to have a personal history of asthma.

In general, the study findings tended to confirm that infection with dengue-1 some time before infection with dengue-2 was closely linked to de- velopment of DHFIDSS. Also, the per-

centage of study children with a history of asthma supports the theory that this

and other sorts of antigenic stimuli can -T increase the risk of developing DHFIDSS. 2

The roughly equal sex ratio 5 of the study children contrasted with a 2 female predominance observed else- $j where among children with severe symptoms. This suggests that the latter E predominance could be due to social be- l

havior patterns rather than to differ- 3 ences in the immune responses of boys 3 and girls. At the same time, the fact 3 that most of the study children were 8 white suggests that whites may be more 8 likely than blacks to develop severe symptoms.

RE

FERENCES

1 Halstead, S. B. Dengue haemorthagic fever: A public health problem and a field for te- search. Bull WHO 58:1-21, 1980.

2 Pittaluga, G. Sobte un btote de dengue en la Habana. Rev&a de Medicina Tropical y Para- sitoiogl, Bacten’ologia, Clinica y Laboratorio

11:1-3, 1945.

3 M&s, P. Dengue fever in Cuba in 1977: Some laboratory aspects. In: Pan American Health

Organization. Dengue in the Caribbean,

1977. PAHO Scientific Publication 375.

Washington, D.C., 1979, pp. 40-43.

4 Kouti, G., M. G. Guzm&n, J. Bravo, M. Ca- lunga, N. Cantelat, M. Solet, L. Motier, A. Fetnandez, and R. Fetn%ndet. El dengue he- mott%gico en Cuba: Algunos aspectos epide- miol6

mia 3 ices, clinicos y vitol$icos de la epide- e fiebte hemottPglca de1 dengue ocuttida en Cuba en 198 1. Paper presented at the V Foto de la Academia de Ciencias de Cuba. Havana, 1982.

Kouti, G., P. M&s, M. G. GutmBn, M. Solet, A. Goyenechea, and L. Motiet. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba, 1981: Rapid diagnosis of the etiologic agent. Ball Pan Am Health Organ 17:126-132, 1983.

Kouti, G., M. G. Guzman, and J. Bravo. Deneue hemott&ico en Cuba: Ct6nica de una ipidemia. Bar Of Sanit Panarz 100:322- 329, 1986.

World Health Organization. Guide for Diag-

nosis, Treatment, and Control of Dengtce

Haemorrhagic Fever: Technical Advisory

Committee on Dengue Huemorrhagic Fever fir the South-East Asian and Western Pacific

Regions (Seconded.). Geneva, 1980.

Sangkawibha, N., S. Rojanasuphot, S.

Ahandtik, S. Vitiyapongse, S. Jatanasen, V. Salitul, B. Phanthumachinda, and S. B. Hal- stead. Risk factors in dengue shock syn- drome: A tospective epidemiologic study in Rayong, T k adand. Am JEpidemiol120:653- 669, 1984.

Halstead? S. B., S. Rojanasuphof, and N. Sanggawtbha. Original antigenic sm in den- gue. Am J Trop MedHyg 32:154-156, 1983.

10 Nimmannitya, S., S. B. Halstead, S. N. Co- hen, and M. R. Matglotta. Dengue and chi- kungunya virus infection in man in Thailand,

11

12

1962-1964: I. Observations on hospitalized oatients with hemotthaeic fever. Am 1 Trob

hedHyg 18:954-971, r969. - -

Halstead. S. B. Observations related to pathogenisis of dengue hemorrhagic fever: VI. Hvnothesii and discussion. Yale I Biol

Med4x350-362, 1970. ”

Barnes, W. J. S., and L. Rosen. Fatal hemot- thagic disease and shock associated with pti- maty dengue infection on a Pacific island. Am J Trap Med Hyg 23~495-506, 1974.

13 Kubetsk$ T., L. Rosen, D. Reed, and J. Ma- taika. Clmtcal and laboratory observations on patients with primary and secondary den type 1 infections with hemorrhagic man f es- tations in Fiji. Am J Trop Med Hyg 26:775- 783, 1977.

14 Rosen, L. Dengue: An Overview. In: Viral Diseases in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. Academic Press, Sydney, Australia, 1982, pp. 484-493.

15 Cantelat, N., A. Fetngndez, M. L. Albert, and B. Perez BaIbis. CitculaciBn de dengue en Cuba, 1978-1979. Revista Cubana de Me- dicina Tropic& 33~72-78, 1981.

16 Diat, A. Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine. Havana. Cuba. Personal commu- nication, ‘1985.

17 Kouti, G., M. G. Guzmiin, and J. Bravo. Why dengue hemottha

An integral analysis. 19 rans R Sot Trop Med ic fever in Cuba? III. Hyg 81, 1987 (in press).

18 Halstead, S. B. The pathogenesis of dengue: Molecular epidemiology in infectious disease.

AmJ Epidemiol114:632-648, 1981.

19 Martinez, E., B. Vidal, 0. Moteno, E. Guzmgn, B. Doualas. and S. Peramo. Den- gue hemorrcigico en el r&o: Estudio c&ico-

bato&ico. Editorial Ciencias Msdicas, Ha- iana, 7984, pp. l-130.

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

Bravo, J., M. G. GuzmPn, and G. Kouri. Whv deneue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba? II.

Individud risk factors”for dengue hemor-

rhagic feverldengue shock syndrome (DHFI

DSS). Tram R Sot Trap MedHyg 81, 1987 (in

press).

Robin, Y., M. Cornet, G. Heme, and G. le Godinec. Isolement du virus de la dengue au SEngal. Ann ViroL (Inst Pasteur) 13 1E: 149- 154, 1980.

Roche, J. C., R. Cordellier, J. P. Hervy, J. P. Digoutte, and N. Monteny. Isolement du 96 souches du virus dengue 2 a partir de mous- tiques captures en Cote-D’Ivoire et Haute- Volta. Ann Viral (Zmt Pasteur) 134E:233- 244, 1983.

Morier, L. Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine, Havana, Cuba. Personal commu- nication, 1986.

Halstead, S. B. Immunological Enhancement of Dengue Virus Infection in the Etiology of Dengue Shock Syndrome. Paper presented at the Third Asian Congress of Pediatrics in Bangkok, Thailand, November 1979.

Wiharta, A. S., H. Hotta Sujudi, T. Matsu- mura, M. Hommam: and S. Hotta. Dengue virus multiplication m cultures of peri heral blood monocytes from Indonesian an x Japa- nese residents, in relation to effects of para- sitic and bacterial components and anti-den-

gue antibodies. ICMR Annals (Kobe

Univerrity) 14:105-115, 1984.

Rojo C., M., M. Carriles D., C. Coto H., L. M. LahozB., C. BoschS., B. AcostaP., M.

28

29

CaIder6n S., A. Saavedra M. 1 R. Marrero R., and M. Rodriguez A. Dengue hemorrsgico: Estudio clinico de 202 pacientes pedikricos. Rev Cabana Pediatnit 54:519-538, 1982.

Riveron, R., R. Carpio, A. Gonzalez, S. Valdes, E. FernPndez, 0. Zarragoitia, G. Abreu, E. Hernandez, and G. Mil%n. Fiebre hemorrGgica de1 dengue en Cuba. Estudio de 783 pacientes egresados de1 Hospital Pedid- trico Docente de Centro Habana, Junio- Septiembre 1981: Parte II. Generalidades y cuadro clinico. Acta M&?ca Dominicana 6:145-150, 1984.

Guzman, M. G., G. Kourl, L. Morier, M. So- ler, and A. Fernandez. A study of fatal hem- orrhagic dengue cases in Cuba, 1981. BuL? Pan Am Health Organ 18:213-220, 1984.

30 George, R., and G. Duraisamy. Bleeding manifestations of dengue haemorrhagic fever in Malaysia. Acta Trop 38~71-78, 1981.

31 Wallace, H. G., T. W. Lim, A. Rudnick, A. B. Knudsen, W. H. Cheong, and V. Chew. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in Malaysia: The 1973 epidemic. Southeast Asian Journal of

Tropical Medicine and Public Heahh 2 : l- 13, 1980.

32 Bravo, J., et al. Unpublished data.