ww w . r b e n t o m o l o g i a . c o m

REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

Entomologia

AJournalonInsectDiversityandEvolutionBiology,

Ecology

and

Diversity

Constant

fluctuating

asymmetry

but

not

directional

asymmetry

along

the

geographic

distribution

of

Drosophila

antonietae

(Diptera,

Drosophilidae)

Marcelo

Costa

a,∗,

Rogério

P.

Mateus

a,

Mauricio

O.

Moura

b aDepartamentodeCiênciasBiológicas,UniversidadeEstadualdoCentroOeste,Guarapuava,PR,Brazil bDepartamentodeZoologia,UniversidadeFederaldoParaná,Curitiba,PR,Brazila

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received27February2015 Accepted9September2015 Availableonline9October2015 AssociateEditor:MárcioR.Pie

Keywords:

Developmentalinstability GeneralizedProcrustesAnalysis Geographicalvariation Geometricmorphometrics Shape

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thepopulationdynamicsofaspeciestendstochangefromthecoretotheperipheryofitsdistribution. Therefore,onecouldexpectperipheralpopulationstobesubjecttoahigherlevelofstressthanmore centralpopulations(thecenter–peripheryhypothesis)andconsequentlyshouldpresentahigherlevelof fluctuatingasymmetry.Totestthesepredictionswestudyasymmetryinwingshapeoffivepopulationsof Drosophilaantonietaecollectedthroughoutthedistributionofthespeciesusingfluctuatingasymmetryas aproxyfordevelopmentalinstability.Morespecifically,weaddressedthefollowingquestions:(1)what typesofasymmetryoccurinpopulationsofD.antonietae?(2)Doestheleveloffluctuatingasymmetry varyamongpopulations?(3)Doesperipheralpopulationshaveahigherfluctuatingasymmetrylevelthan centralpopulations?Weused12anatomicallandmarkstoquantifypatternsofasymmetryinwingshape infivepopulationsofD.antonietaewithintheframeworkofgeometricmorphometrics.Netasymmetry –acompositemeasureofdirectionalasymmetry+fluctuatingasymmetry–variedsignificantlyamong populations.However,oncenetasymmetryofeachpopulationisdecomposedintodirectionalasymmetry andfluctuatingasymmetry,mostofthevariationinasymmetrywasexplainedbydirectionalasymmetry alone,suggestingthatpopulationsofD.antonietaehavethesamemagnitudeoffluctuatingasymmetry throughoutthegeographicaldistributionofthespecies.Wehypothesizethatlarvaldevelopmentin rottingcladodesmightplayanimportantroleinexplainingourresults.Inaddition,ourstudyunderscores theimportanceofunderstandingtheinterplaybetweenthebiologyofaspeciesanditsgeographical patternsofasymmetry.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeEntomologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Anyspeciesisfacedwithavarietyofclimatesandenvironments throughoutitsgeographicaldistribution,resultingindifferent lev-elsofstressandselectivepressures(Brownetal.,1996;Bridleand Vines,2007).Thesefactorscanaffectgeneticandphenotypictraits, thusgeneratingclinesordiscontinuitiesthroughoutthe distribu-tion(HoffmannandShirriffs,2002).

Modelsof morphologicaldevelopmenthave emphasizedthe interactionofavarietyofcomponentsinanorganismto gener-ateafunctionalstructureunderasetofconditions(Klingenberg et al., 1998). However, stressing factors such as variation in nutrition,temperature,populationdensity,pollutants,andhabitat

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:marcelokosta@yahoo.com.br(M.Costa).

fragmentationcanleadtodevelopmentalinstability(DI)(Moller andSwaddle,1997;Lensetal.,1999;Hoskenetal.,2000).Giventhat suchperturbationswillbevisibleatthelevelofthephenotype,the presenceofphenotypicchangescanindicatetheextenttowhich anorganismis respondingtoitsstressors(Hoskenetal.,2000). In this context, thepattern of symmetry of bilateralstructures hasbeenwidelyusedasamarkerfordevelopmentalinstability (MollerandSwaddle,1997).Giventhatbothsidesofanorganism areunderthecontrolofthesamegeneticpathwaysduring develop-ment,onemightexpectthatanydeviationfromsymmetrymightbe theproductoflocaldisturbancesthatwouldbreakdevelopmental homeostasis(Hoskenetal.,2000;Breukeretal.,2006).

The asymmetrycan bedescribed bythe frequency distribu-tionofthedifferencebetweentheleftandtherightsidesofthe individualsofapopulation(PalmerandStrobeck,1986).In gen-eral,therearethreemaintypesofbilateralasymmetry:fluctuating asymmetry (FA), directional asymmetry (DA) and antisymme-try(AS)(PalmerandStrobeck,1986,1992,2003;Palmer,1994).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbe.2015.09.004

FAis a modelof variation in which deviations fromsymmetry are distributed close to a mean of zero, and are random and non-directional.Alternatively,deviationscanbedistributed pref-erentiallyinonedirection,thusgeneratingDA,inwhichthereisa tendencyfortheexcessivedevelopmentofonespecificsidein rela-tiontotheother,leadingtoadistributionwiththeaveragedeviates beingsignificantlydifferentfromzero(Palmer,1994).Finally,ASis foundwheneveronesideisusuallygreaterthantheother,yetthe positionofthelargersidevariesrandomlyinapopulation,leading toabimodaldistributionofthedifferencesbetweentheleftand rightsidesofthebody(PalmerandStrobeck,1992;Palmer,1994). Ofallthreetypesofasymmetry,FAhasbeenconsideredasa measureofDI,giventhatitreflectstheinabilityofanorganism tocopewithstressingfactorsandtheresultingperturbations dur-ingdevelopment(Palmer,1994;KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998). ContrarytoFA, othertypesofasymmetryarecausedinpartby eithergeneticorenvironmentalfactorsandarethereforeharderto associatewithDI,nortobeusedasaproxytomeasureit(Palmer andStrobeck,2003).However,thethreetypesofasymmetryare related,withacontinuumbetweenthem(Grahametal.,1998;Kark, 2001).Therefore,thetransitionfromFAtoDAorAScanindicate severeinstabilityduringdevelopment(Grahametal.,1998),yet theserelationshipshavenotbeenfullyunderstood.Althoughthe relationshipbetweenFAandthemechanismscausingstressisalso unclear,withsometestsprovidingconflictingresults(Hoffmann etal.,2005;VangestelandLens,2011),theFAhasbeenconsidered agoodindicatorofDIandthus,actasabiomarkerto environmen-talstress(Beasleyetal.,2013;Lazi ´cetal.,2013;Lezcanoetal., 2015).

Thepopulationdynamicsofaspeciestendstochangefromthe coretotheperipheryofitsdistribution(Brownetal.,1996;Lens

etal.,1999).Therefore,onecouldexpectperipheralpopulations tobesubjecttoahigherlevelofstressthanmorecentral popula-tions(thecenter–peripheryhypothesis)andconsequentlyshould presentahigherlevelofFA(Kark,2001).Onespatialpatternof asymmetrywasdetectedinthepartridgeAlectorischukar(Gray, 1830),whichshowedanincreaseintheproportionofasymmetric individualsinperipheralpopulations,aswellashigherlevelsofDA andAS(Kark,2001).However,inthesamegeographical region, twospecies ofEuchloebutterfliesdidnot differwithrespectto thelevelofasymmetrybetweenpopulationsinthecenterandthe peripheryoftheirranges(Karketal.,2004), suggestingthatthe responseofasymmetryinrelationtogeographicalvariationcould varydependingonthestudiedorganismanditshabitat.

Thereisstrongevidencesupportinglatitudinalvariationin sev-eralmorphological traitsin Drosophila,including bodysize and wingsizeandshape(HoffmannandShirriffs,2002;Griffithsetal., 2005). However, most of these studies have been carried out usingcosmopolitanspecies,whereaslittleisknownaboutspecies withrangesrestrictedtospecifictypesofhabitat(Griffithsetal., 2005).Oneparticularlymodelsysteminthisrespectisthe cacto-phylicspeciesDrosophilaantonietaeTidon-SklorzandSene,2001.

D.antonietaeisendemictoSouthAmericafoundfromSouthand Southeast Brazil tothe eastern edge of theArgentinean Chaco (ManfrinandSene,2006).Itsdistributionisassociatedwith frag-ments of xerophytic vegetation that include the cactus Cereus hildmannianusK.Schum(MateusandSene,2003;ManfrinandSene, 2006).ThelarvaeofD.antonietaedevelopwithinrottingcladodes, feedingontheyeastpresentin thisenvironment(Pereiraetal., 1983;ManfrinandSene,2006).

Despitetheconsiderablegeographicaldistancebetweenthese populationsandthelimitedcapacityfordispersalinD.antonietae,

Rio Grande do Sul state Santa Catarina state

Atlantic Ocean Guarapuava

Cantagalo Paraná state

Brazil

Itirapina Serrana São Paulo state

Santiago

0 100 200

km

N

Fig.1.LocationsofthesampledpopulationsofDrosophilaantonietae.Serrana(21◦14′S,47◦34′W),Itirapina(22◦16′S,47◦48′W),Guarapuava(25◦17′S,51◦53′W),Cantagalo

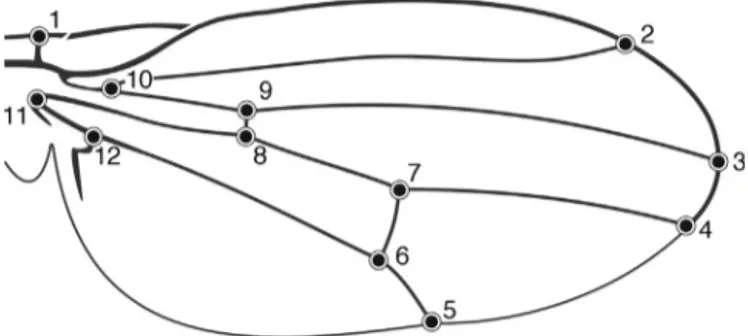

Fig.2.RepresentationofthewingofDrosophilaantonietaeindicatingtheposition ofthe12anatomicallandmarks.

thereisstilluncertaintyregardingtheirlevelofisolation(Manfrin andSene,2006;MateusandSene,2007).Localpopulationsdisplay highgeneticvariabilityandmoderategeneticdiversity,leadingto hypothesessuggestingeitheramoderatelevelofgenefloworshort periodsofdifferentiationfollowedbythemaintenanceofancestral polymorphism(MateusandSene,2007).Ingeneral,populationsof

D.antonietaearefragmentedandhavelowadditivegenetic vari-ance(MateusandSene,2007).Giventhatthefragmentationcould produceDI(Lenset al.,1999), itis possiblethat thesame sce-narioappliestothefragmentedpopulationsofD.antonietae.Also, asfragmentationoccursalongthegeographicaldistributionofD. antonietaeit isalsopossiblethatthelevelof DIvariesspatially aspredictedbythecenter–peripheryhypothesis.Ifthisscenario holds,itwouldbeexpectedtofindFAinallpopulationssampled and,also,ahigherlevelofFAinperipheralthanincentral popula-tions.Totestthesepredictionswestudyasymmetryinwingshape offivepopulationsofD.antonietaecollectedthroughoutthe distri-butionofthespeciesusingFAasaproxyforDI.Morespecifically, weaddressedthefollowingquestions:(1)whattypesof asymme-tryoccurinpopulationsofD.antonietae?(2)DoesthelevelofFA varyamongpopulations?(3)Doesperipheralpopulationshavea higherFAlevelthancentralpopulations?

Materialandmethods

Specimencollection

Wecollectedatotalof201malesfromfivepopulationsofD. antonietae,namelySerrana(n=22)andItirapina(n=40)locatedin thestateofSãoPaulo(thenorthernmostlimitofthe geographi-caldistributionofthespecies),Guarapuava(n=23)andCantagalo (n=66)locatedinthestateofParaná(thegeographicalcenterof thespeciesdistribution),andSantiago(n=50)locatedinthestate ofRioGrandedoSul(thesouthernmostlimitofthegeographical distributionofthespecies)(Fig.1).Thedrosophilidspecimenswere capturedbyclosedtraps(Penarioletal.,2008)containingbanana andorangebaitsfermentedbyyeast(Saccharomycescerevisiae).

Dataacquisitionandgeometricmorphometrics

We used the right and left wings of males of D. antonietae

asourmorphometricmarkerduetotheeaseofidentificationof homologouslandmarksformedbytheintersectionofveins,and by the extensiveunderstanding of the mechanisms underlying wingdevelopmentinDrosophila (HoffmannandShirriffs, 2002; Griffithset al.,2005).Wingswereremoved,mounted on semi-permanentslides,anddigitallyphotographedunderamicroscope. Twelve type 1 anatomical landmarkswere locatedonthe dor-salsurfaceofthewings(Fig.2)usingthesoftware TPSDig2.16 (Rohlf, 2010).Type1landmarksare characterizedby the inter-sectionofthree structuresand areformedbythejuxtaposition

of tissues (Monteiro and Reis, 1999), which in ourcase corre-spondsto theintersectionof wing veinsof D. antonietae.Each landmarkwasdigitalizedthree timesineach wingbythesame person on differentdays toallow for estimating measurement error.

Landmarkconfigurationswere superimposed using General-izedProcrustesAnalysis(GPA)(KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998; MonteiroandReis,1999).GPAbeginsbyreflectinglandmark con-figurationsfromoneofthesidesandsuperimposingthembytheir centroid(midpointof aconfigurationofanatomicallandmarks). Thesizeofthecentroid,thesquare-rootofthesumofthesquared distancesfromasetoflandmarktotheircentroid(Monteiroand Reis, 1999), is then scaled toone. Finally, each landmark con-figuration is rotated such that the squared distances between homologouslandmarksareminimized.Asaresultofallofthese cal-culations,thedistancesbetweenthesuperimposedconfigurations ofleftandrightstructurescorrespondtotheextenttowhichthey differinshape,giventhattheyareanapproximationtoProcrustes distances(KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998).

Statisticalanalyses

Shapeasymmetrywasanalyzedusingconfigurations superim-posedasdependentvariablesinaProcrustesANOVA(Klingenberg andMcIntyre,1998),suchthatthespecimenidentityconsidered asarandomeffectandsideofthebodywasusedasafixedeffect. Inparticular,theamong-speciesmaineffectstandsforindividual shapevariation,theeffectofthesideofthebodycorrespondedto directionalasymmetry(DA),theinteractionbetweenthesideofthe bodyandthespecimenidentitycorrespondedtofluctuating asym-metry(FA)andtheresidualtermcorrespondedtothemeasurement errorinthemodel(Palmer,1994;KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998; PalmerandStrobeck,2003).IntheProcrustesANOVA,thedegrees offreedomarecalculatedbymultiplyingthenumberofdegreesof freedomofeachfactorbythetotalnumberofdimensionsinshape space(KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998;MonteiroandReis,1999). Antisymmetry(AS)inwingshapewasanalyzedusingscatterplots ofthedifferencesbetweentheleftandrightsideforeach land-mark.Theformationofclustersofpointsinthisdistributionwould correspondtoabimodaldistributioninthedifferencesbetween theleftandtherightsidesandconsequentlytothepresenceofAS (KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998;PalmerandStrobeck,2003).

In each individual, shape asymmetry can be measured as thedeviationfromtheperfectsuperimpositionofleftand right configurations(Klingenberg and McIntyre,1998).Therefore, the individualnetasymmetry(NAi)wasestimatedbytheProcrustes distancebetweentheleftandrightconfigurationsofeach individ-ual(Marchandetal.,2003).Ontheotherhand,thepopulationnet asymmetry(NA)wasestimatedbyaveragingindividualnet asym-metries(NAi).GiventhatNAiscomposedofbothFAandDA,NA canbepartitionedintothosetwo typesofasymmetry(Graham etal.,1998; Marchandetal.,2003).Thepopulationestimateof DAwasobtainedbycalculatingtheProcrustesdistancebetween theaverageoftheleftandrightconfigurationsofeachpopulation (Schneideretal.,2003),whereasthedifferencebetweenNAand DAwasconsideredasapopulation-levelestimateofFA(Marchand etal.,2003).Therefore,thevaluesofindividualfluctuating asym-metry(FAi)wereobtainedbycalculatingthedifferencebetween NAiandDAofeachspecimen.

ThedifferencesinthelevelsofNAandFAbetweenpopulations weretestedusingANOVAswithNAiandFAiasresponsevariables, whereaspopulationoforiginandreplicatesaspredictorvariables. Replicates wereaddedtotheANOVAs toestimatetheeffectof measurementerroronthelevelofFA.

Table1

Analysisof shape asymmetry. Result of ProcrustesANOVA of populations of

Drosophilaantonietae.

Effect DF MS F

Population 80 0.0004897 4.45a

Individual(I) 3920 0.0001101 6.79a

Side(S) 20 0.0005663 34.94a

I*S 4000 0.0000162 4.83a

Error 16,080 0.0000034

ap<0.001.

Results

TheanalyzedpopulationsofD.antonietaeshowedboth direc-tionalasymmetry(DA)and fluctuatingasymmetry(FA)inwing shape(Table1).Thepartitioningofvarianceobtainedfromthe Pro-crustesANOVAindicated thattheeffectof theside ofthebody andtheinteractionbetweenthesideandspecimenidentitywere significant,implyingnotonlythatD.antonietaehasbothDAand FAin wing shape, but also that the level of FA is higher than theerrorterm.However, asymmetryis nothomogeneouswith respecttotheeffectofspecimenidentityandsourcepopulation. Inaddition,theanalysisof ascatterplotof differencesbetween leftandrightsidesdemonstratedthattheanalyzedpopulations do notdisplay AS.TheDA ismainly relatedto adislocation in theanterior–posteriorwingaxis,producedbylandmarks11(wing base),06(posteriorwingmargin)and02(anteriorwingmargin), andin thebase–apex axisfrommovementof thelandmark 04 (Fig.3).

Thelevelof netasymmetry(NA)– composedof thesumof FA and DA, differed only between populations of Serrana and Santiago(F4,596=27.85; p<0.05), whichdisplay thehighest and

the lowest values of NA (0.0193±0.0037 and 0.0174±0.0044, respectively),whereas the remainingpopulations had interme-diatevalues(Fig.4).Ontheotherhand,partitioningNAintoits FAand DA componentsallows for determining which of those typesofasymmetryaccountsforvariationinNAbetween popula-tions.Curiously,therewasnodifferenceinFAbetweenpopulations (F4,596=0.82;p>0.05),suggestingthatpopulationsofD.antonietae

havethesamemagnitudeofFAthroughoutthegeographical dis-tributionofthespecies (Fig.4).Therefore,thedifferencein NA betweenthepopulationsofSerranaandSantiagoisduetoDA,not FA(Fig.4).Again,populationsofSerranaandSantiagoshowedthe highestandthelowestlevelsofDA(0.0087and0.0057),whereas theremainingpopulations had intermediate values (Fig. 4).No significanteffect ofmeasurement errorwasdetectedin theNA analysis (F2,596=16.72; p>0.05), as well as in the FA analysis

(F2,596=16,72;p>0,05),suggestingthatmeasurementerrorinthis

studyisrandomanddoesnotaffecttheoutcomeofasymmetry analyses.

Fig.3.Diagramofthedifferencebetweentheshapeaveragesoftheleftwing (graylines)andrightwing(blacklines),correspondingtodirectionalasymmetry inDrosophilaantonietae.Deformationsmagnified10times.

0.020 a ab ab ab b

0.015

0.010

0.005

0

Ser Iti Gua

Population

Net asymmetry

Can San

Fig.4.Netasymmetrylevel(DA+FA)ofpopulationsofDrosophilaantonietae.DA, directionalasymmetry(lightgray);FA,fluctuatingasymmetry(darkgray);Ser, Serrana;Iti,Itirapina;Gua,Guarapuava;Can,Cantagalo;San,Santiago.Lowercase lettersdenoteshomogeneousgroups(p<0.05)accordingtoaTukeytest.

Discussion

Ourresultsindicatedthat,althoughpopulationsofD. antoni-etae showed both fluctuating and directional asymmetry, net asymmetry(NA=DA+AF)variedsignificantlyamongpopulations. However,mostofthevariationisexplainedbyDAalone,suggesting thatthelevelofFAisnotstructuredgeographicallyinD.antonietae.

Wehypothesizethatlarvaldevelopmentinrottingcladodesmight playanimportantroleinexplainingourresults.

Fluctuatingasymmetry hasbeen associatedwith geographi-caldistributionasanindicatorofdevelopmentalinstability(DI), possiblyreflectingenvironmentalchangesalongthedistribution of a species (Kark, 2001). However, the relationship between asymmetry(basedonmeasurementsoflineartraits)andthe geo-graphicaldistributionofspecieshasbeencontroversial(Jenkins andHoffmann,2000;Kark,2001;Karketal.,2004)becausesome speciesdonotshowthisexpectedspatialpatternofasymmetry (JenkinsandHoffmann,2000;Karketal.,2004),suggestingthat asymmetryvariesdependingonthestudiedorganismandits habi-tat.Jenkinsand Hoffmann(2000)foundthatthepopulationsof

DrosophilaserrataMalloch(1927)alongeasternAustraliaalsodid notshowvariationinthelevelofFAincentralandperipheral popu-lations.Likewise,ourresultsindicatethat,althoughD.antonietae

didshowFA,thedifferencesinNAbetweenpopulationsofSerrana andSantiagocanbeaccountedforbychangesinDAratherthanFA. ThissuggeststhatthelevelofFAisnotstructuredgeographically inD.antonietae,thusindicatingthatotherfactorsrelatedtothe biologyofD.antonietaemightactinoppositiontoenvironmental variationtobufferthelevelofasymmetryfoundinpopulations.

mighthave“escaped”theenvironmentalvariationduetothelife historyofthespeciesasbeingassociated withahostplant,the cactusC.hildmannianus.ThelarvaeofD.antonietaedevelopwithin decomposingtissuesinsidecladodes,feedingonyeast(Manfrinand Sene,2006).Thesecladodes mightprovideamicroenvironment (Sotoetal.,2007)whereenvironmentalvariationisbuffered,thus decreasingstressduetoenvironmentalfactors.Asimilarscenario hasbeensuggestedtoexplaintheabsenceof asymmetryalong thegeographical distributionof Euchloebutterflies (Karket al., 2004).Ontheotherhand,Gibbsetal.(2003)investigateddirectly themicroclimateindecomposingcladodesintheSonorandesert anddemonstratedthat,althoughcladodesmightbuffertosome extentenvironmentalchanges,theymightneverthelessexperience markedvariationinrelativehumidity.Moreover,thetemperature withincladodemightactuallyexceedtheexternaltemperature, whichcouldsuggestthatthesestructuresarelikelynotanefficient thermicrefugiumforDrosophila.However,theconditionsindeserts (withexposedcladode)mightnotberepresentativeofthe condi-tionsoncactifoundingalleryforestsalongtheParaná,Paraguay, andUruguayriverbasins(ManfrinandSene,2006; Mateusand Sene, 2007). In this case, rotting cladodes are“protected” by a vegetationcover,whichmightfacilitateenvironmentalbuffering andpossiblyactasaclimaticrefugiumforD.antonietae.Finally,it ispossiblethatanotherstressingfactormightbehomogeneously affectingpopulationssuchthattheyexpressasimilarlevelof asym-metry.D.antonietaeismoreviableandhasalowerdevelopment timewhenrearedinculturemediawithexudatesfromthecactus

PilosocereusmachrisiiY.Dawsonincomparisonwithmediafrom itsown hostplant,C. hildmannianus(Soto etal., 2007).Onthe otherhand,thelevelofFAinthewingofD.antonietaeishigher whenrearedinculturemediabasedonC.hildmannianusthanon

P.machrisii(Sotoetal.,2010).Thesecombinedobservationsmight indicatethatC.hildmannianusitselfcouldbeconsideredasa stress-ingfactorforthedevelopmentofD.antonietae.Asaconsequence, allpopulationsofD.antonietaewouldbeunderasimilarlevelof stress,regardlessofgeographicaldistribution,thusleadingto sim-ilarlevelsofresponseintermsofasymmetry.Thisdemonstrates thattheinteractionwithC.hildmannianuscanplayanimportant roleinthepatternofasymmetryobservedbetweenpopulationsof

D.antonietae.

OurresultsarealsoconsistentwiththepresenceofDAin popu-lationsofD.antonietae.Directionalasymmetryisnotarareeffectin Diptera(KlingenbergandMcIntyre,1998;Klingenbergetal.,1998; PélabonandHansen,2008;Sotoetal.,2010),aswellinother inver-tebrate(Grahametal.,1998;Schneideretal.,2003)andvertebrate groups(Kark,2001;Marchandetal.,2003;Loehretal.,2013).In Diptera,Klingenbergetal.(1998)suggestedthatthegeneticbasis ofDAhasbeenconservedoverevolutionarytimeduetothe exist-enceofaleft-rightaxisdeterminingthepositionofimaginaldisks (developmentalprecursorsofwings)oneachsideofthebody.In thecaseofsizeDA,PélabonandHansen(2008)carriedoutareview ofstudiesonDAin insectwings andshowedthatthedirection ofasymmetryisconsistentwithinspecies,butis notconserved athighertaxonomiclevels(including Diptera).It hasbeen sug-gestedthatbothDAandAScanbegeneratedinresponsetoahigh levelofstress,thusprovidingacontinuumbetweenthesetypes ofasymmetry(Grahametal.,1998,butseePalmerandStrobeck, 1992).Theassociationbetweendifferenttypesofasymmetryhas beenfoundinthepartridgeA.chucker(Kark,2001),wherethe pat-ternofsizeasymmetrychangesgeographically(fromthecenterto theperiphery),suchthatperipheralpopulationshavehigherlevels ofasymmetry(FA, DA,andAS) thancentralones.The relation-shipbetweenDAandDIhasalsobeensuggested forDrosophila

bySoto etal.(2010)when investigatingthedevelopmentof D. antonietaeandDrosophilagouveaiTidon-SklorzandSene,2001in culturemediabasedondifferenthostcacti(C.hildmannianusand

P.machrisii).ThepresenceofDAinwingshapewasdetectedwhen eitherspecieswasrearedonC.hildmannianusmedia,butnoton

P.machrisii(Sotoetal.,2010).ThepresenceofDAinpopulations ofD.antonietaeislikelyaproductofanevolutionarilyconserved patterninDipteraandthevariationinDAfoundinthepopulations ofSerranaandSantiagoarepossiblyrelatedtolocal(historicalor ecological)differencesbetweenthesepopulations.

Mappingtheeffectsofperturbationsonphenotypic develop-ment is a complexissue.In general,ourresultssuggested that fluctuating asymmetry in D. antonietaehassimilar levels in all populations,whichsuggestsahomogeneousperturbation.Given thatDAvariesontheedgeofthedistributionofthespecies,we hypothesizethatlocalevolutionaryeffectsondemographymight havegenerated thisdifference.Givethatthecactusisthestage wheredevelopmenttakesplace,thereisapotentialforstresstobe generatedfromthisinteraction.Thus,understandinghow asym-metrypatternsaregeneratedinthissystemwouldentailabetter comprehensionofhowtheplant/herbivoreinteractionoccursand variesbetweenpopulations.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

MC was supported by a graduate scholarship from the Coordenac¸ãode Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de NívelSuperior (CAPES).ThisstudywaspartiallyfundedbygrantstoMOMfrom Conselho de DesenvolvimentoCientífico eTecnológico (CNPq– processes 475461/2007e312357/2006)and toRPM fromSETI/ Fundac¸ãoAraucária(processes103/2005,231/2007and415/2009) andfromFINEP(processes01.05.0420.00/2003and1663/2005).

References

Beasley,D.A.E.,Bonisoli-Alquati,A.,Mousseau,T.A.,2013.Theuseoffluctuating asymmetryasameasureofenvironmentallyinduceddevelopmentalinstability: ameta-analysis.Ecol.Indic.30,218–226.

Breuker,C.J.,Patterson,J.S.,Klingenberg,C.P.,2006.Asinglebasisfordevelopmental bufferingofDrosophilawingshape.PloSone1,e7.

Bridle,J.R.,Vines,T.H.,2007.Limitstoevolutionatrangemargins:whenandwhy doesadaptationfail?TrendsEcol.Evol.22,140–147.

Brown,J.H.,Stevens,G.C.,Kaufman,D.M.,1996.Thegeographicrange:size,shape, boundaries,andinternalstructure.Annu.Rev.Ecol.Evol.Syst.27,597–623. Gibbs,A.G.,Perkins,M.C.,Markow,T.A.,2003.Noplacetohide:microclimatesof

SonoranDesertDrosophila.J.ThermalBiol.28,353–362.

Graham,J.H.,Emlen,J.M.,Freeman,D.C.,Leamy,L.J.,Kieser,J.A.,1998.Directional asymmetryandthemeasurementofdevelopmentalinstability.Biol.J.Linn.Soc. 64,1–16.

Griffiths,J.A.,Schiffer,M.,Hoffmann,A.A.,2005.Clinalvariationandlaboratory adap-tationintherainforestspeciesDrosophilabirchiiforstressresistance,wingsize, wingshapeanddevelopmenttime.J.Evol.Biol.18,13–222.

Hoffmann,A.A.,Shirriffs,J.,2002.GeographicvariationforwingshapeinDrosophila serrata.Evolution50,1068–1073.

Hoffmann,A.A.,Woods,R.E.,Collins,E.,Wallin,K.,White,A.,McKenzie,J.A.,2005. Wingshapeversusasymmetryasanindicatorofchangingenvironmental con-ditionsininsects.Aust.J.Entomol.44,233–243.

Hosken,D.J.,Blanckenhorn,W.U.,Ward,P.I.,2000.Developmentalstabilityinyellow dungflies(Scathophagastercoraria):flutuatingasymmetry,heterozygosityand environmentalstress.J.Evol.Biol.13,919–926.

Jenkins,N.L.,Hoffmann,A.A.,2000.Variationinmorphologicaltraitsandtrait asym-metryinfieldDrosophilaserratafrommarginalpopulations.J.Evol.Biol.13, 113–130.

Kark,S.,2001.Shiftsinbilateralasymmetrywithinadistributionrange:thecaseof thechucarpartridge.Evolution55,2088–2096.

Kark,S.,Lens,L.,VanDongen,S.,Schmidt,E.,2004.Asymmetrypatternsacrossthe distributionrange:doesthespeciesmatter?Biol.J.Linn.Soc.81,313–324. Klingenberg,C.P.,2011.MorphoJ:anintegratedsoftwarepackageforgeometric

morphometrics.Mol.Ecol.Resour.11,353–357.

Klingenberg,C.P.,McIntyre,G.S.,1998.Geometricmorphometricofdevelopmental instability:analyzingpatternsoffluctuatingasymmetrywithProcrustes meth-ods.Evolution52,1363–1375.

Lazi ´c,M.M.,Kaliontzopoulou,A.,Carretero,M.A.,Crnobrnja-Isailovi ´c,J.,2013.Lizards fromurbanareasaremoreasymmetric:usingfluctuatingasymmetrytoevaluate environmentaldisturbance.PloSone8,e84190.

Lens,L.,Dongen,S.,Wilder,C.M.,Brooks,T.M.,Matthysen,E.,1999.Fluctuating asym-metryincreaseswithhabitatdisturbanceinsevenbirdspeciesofafragmented afrotropicalforest.Proc.R.Soc.Ser.B266,1241–1246.

Lezcano,A.H.,Quiroga,M.L.R.,Liberoff,A.L.,VanderMolen,S.,2015.Marinepollution effectsonthesouthernsurfcrabOvalipestrimaculatus(Crustacea:Brachyura: Polybiidae)inPatagoniaArgentina.Mar.Pollut.Bull.91,524–529.

Loehr,J.,Herczeg,G.,Leinonen,T.,Gonda,A.,VanDongen,S.,Merilä,J.,2013. Asym-metryinthreespinesticklebacklateralplates.J.Zool.289,279–284.

Manfrin,M.H.,Sene,F.M.,2006.CactophilicDrosophilainSouthAmerica:amodel forevolutionarystudies.Genetica126,57–75.

Marchand,H.,Paillat,G.,Montuire,S.,Butet,A.,2003.Fluctuatingasymmetryin bankvolepopulations(RodentiaArvicolinae)reflectsstresscausedby land-scapefragmentationin the Mont-Saint-Michel Bay. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 80, 37–44.

Mateus,R.P.,Sene,F.M.,2003.TemporalandspatialallozymevariationintheSouth AmericancactophilicDrosophilaantonietae(DipteraDrosophilidae).Biochem. Genet.41,219–233.

Mateus,R.P.,Sene,F.M.,2007.Populationgeneticstudyofallozymevariationin naturalpopulationsofDrosophilaantonietae(Insecta,Diptera).J.Zool.Syst.Evol. Res.45,136–143.

Moller,A.P.,Swaddle,J.P.,1997.Asymmetry,DevelopmentalStabilityandEvolution. OxfordUniversityPress,Oxford.

Monteiro,L.R.,Reis,S.F.,1999.Princípiosdemorfometriageométrica.HolosEditora, RibeirãoPreto.

Palmer,A.R.,1994.Fluctuatingasymmetryanalyses:aprimer.In:Markow,T.A.(Ed.), DevelopmentalInstability:ItsOriginsandEvolutionaryImplications.Kluwer, AcademicPublishers,Dordrecht,pp.335–364.

Palmer,A.R.,Strobeck,C.,1986.Fluctuatingasymmetry:measurement,analysis, patterns.Annu.Rev.Ecol.System.17,391–421.

Palmer,A.R.,Strobeck,C.,1992.Fluctuatingasymmetryasameasureof developmen-talstability:Implicationsofnon-normaldistributionsandpowerofstatistical tests.ActaZool.Fenn.191,55–70.

Palmer,A.R.,Strobeck,C.,2003.Fluctuatingasymmetryanalysisrevisited.In:Polak, M.(Ed.),DevelopmentalInstability(DI):CausesandConsequences.Oxford Uni-versityPress,Oxford,pp.279–319.

Pélabon,C.,Hansen,T.F.,2008.Ontheadaptiveaccuracyofdirectionalasymmetry ininsectwingsize.Evolution62,2855–2867.

Penariol,L.,Bicudo,H.E.M.D.C.,Madi-Ravazzi,L.,2008.Ontheuseofopenorclosed trapsinthecaptureofdrosophilids.BiotaNeotropica8,47–51.

Pereira,M.A.Q.R.,Vilela,C.R.,Sene,F.M.,1983.Notesonbreedingandfeedingsites ofsomespeciesoftherepletagroupoftheGenusDrosophila(Diptera Drosophil-idae).Ciênc.Cult.35,1313–1319.

RDevelopmentCoreTeam,2012.R:ALanguageandEnvironmentfor Statisti-calComputing.RFoundationforStatisticalComputing,Vienna,Availableat http://www.R-project.org/.

Rohlf, F.J., 2010. TPSDig, Digitize Landmarks and Outlines, Version 2.16. State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, Available at http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/.

Schneider,S.S.,Leamy,L.J.,Lewis,L.A.,DeGrandi-Hoffman,G.,2003.Theinfluence ofhybridizationbetweenAfricanandEuropeanhoneybees,Apismellifera,on asymmetriesinwingsizeandshape.Evolution57,2350–2364.

Soto,I.M.,Manfrin,M.H.,Sene,F.M.,Hasson,E.,2007.Viabilityanddevelopmental timeinthecactophilicDrosophilagouveaiandDrosophilaantonietae(Diptera: Drosophilidae)aredependentofthecactushost.Ann.Entomol.Soc.Am.4, 490–496.

Soto,I.M.,Carreira,V.P.,Corio,C.,Soto,E.M.,Hasson,E.,2010.Hostuseand devel-opmentalinstabilityinthecactophilicsiblingspeciesDrosophilagouveaiandD. antonietae.Entomol.Exp.Appl.137,165–175.