Brazilian

Journal

of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

www.bjorl.org

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Oral

cancer

preventive

campaigns:

are

we

reaching

the

real

target?

夽

Renato

Paladino

Nemoto

∗,

Alana

Asciutti

Victorino,

Gregory

Bittar

Pessoa,

Lais

Lourenc

¸ão

Garcia

da

Cunha,

José

Antonio

Rodrigues

da

Silva,

Jossi

Ledo

Kanda,

Leandro

Luongo

de

Matos

FaculdadedeMedicinadoABC(FMABC),SantoAndré,SP,Brazil

Received22October2013;accepted9March2014 Availableonline19October2014

KEYWORDS

Mouthneoplasms; Headandneck neoplasms; Healthpromotion; Epidemiologyand biostatistics

Abstract

Introduction:Oral cavity malignantneoplasms havea high mortalityrate. For this reason, preventivecampaignshavebeendeveloped,bothtoeducatethepopulationandtodiagnose lesionsatanearlystage.However,therearestudiesthatcontestthevalidityoftheseendeavors, principallybecausethe targetaudienceofthecampaigns maynotconform tothegroupat highestriskfororalmalignancy.

Objective:Todescribe theprofileofpatients who availthemselvesofthe preventive cam-paign,identifythepresenceoforallesionsinthatpopulation,andcomparethatdatawiththe epidemiologicalprofileofpatientswithoralcancer.

Methods:Cross-sectionalhistoricalcohortstudyperformedbyanalysisofepidemiologicaldata ofthecampaign‘‘AbraaBocaparaaSaúde’’collectedintheyearsfrom2008to2013.

Results:Intheyearsanalyzed,11,965peopleweretreatedand859lesionswerediagnosed,all benign.Therewasafemalepredominance(52.7%),withmeanageof44years(±15.4years); 26%weresmokersand29%reportedalcoholconsumption.Itisknownthatthegroupathighest risktodeveloporalcanceris60-to70-year-oldmen,whoarealcoholicsmokers.

Conclusion:Thepopulationthatseekspreventivecampaignsisnotthemainriskgroupforthe disease.Thisfactexplainsthelownumberoflesionsandthelackofcancerdetection. © 2014Associac¸ãoBrasileira de Otorrinolaringologiae CirurgiaCérvico-Facial. Publishedby ElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:NemotoRP,VictorinoAA, PessoaGB,daCunhaLL, daSilvaJA,KandaJL, etal.Oralcancerpreventive campaigns:arewereachingtherealtarget?BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2015;81:44---9.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:renatonemoto@hotmail.com(R.P.Nemoto).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.03.002

1808-8694/©2014Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeOtorrinolaringologia eCirurgiaCérvico-Facial. PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.All rights

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Neoplasiasbucais; Neoplasiasdecabec¸a epescoc¸o;

Promoc¸ãodasaúde; Epidemiologiae bioestatística

Campanhadeprevenc¸ãodocâncerdeboca:estamosatingindooverdadeiro público-alvo?

Resumo

Introduc¸ão: Asneoplasiasmalignasdecavidadeoralpossuemaltataxademortalidade.Poressa razão,existemdiversascampanhasdeprevenc¸ãodocâncerbucal,visandoorientarapopulac¸ão ediagnosticarlesõesemestágioprecoce.Contudo,váriosestudoscontestamavalidadedessas iniciativas,umavezqueopúblicoalvoatingidopodenãorepresentaroverdadeirogrupode risco.

Objetivo: Descreveroperfildospacientesqueprocuraramacampanhadeprevenc¸ão, identi-ficarapresenc¸adelesõesoraisecompararosdadoscomoperfilepidemiológicodepacientes portadoresdecâncerbucal.

Método: Coortehistóricatransversal.Foramlevantadososdadosepidemiológicosdacampanha ‘‘Abraabocaparaasaúde’’dosanosde2008a2013.

Resultados: Nosanosavaliados, 11965pessoasforamatendidase859lesõesdiagnosticadas, todasbenignas.Apredominânciafoidosexofeminino(52,7%),commédiadeidadede44anos (±15,4anos),26%eramtabagistase29%relatavamusodeálcool.Sabe-sequeogrupoderisco correspondeahomens,entre60e70anos,tabagistaseetilistas.

Conclusão:Apopulac¸ãoqueprocuraacampanhanãoéoprincipalgrupoderiscoparaadoenc¸a, fatoqueexplicaobaixonúmerodelesõesdetectadasenenhumcâncer.

©2014Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeOtorrinolaringologiaeCirurgiaCérvico-Facial.Publicado por ElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Malignantneoplasms ofthehead andneckregionaccount for 10%ofall humanmalignanttumorsandapproximately 40% of them occur in the mouth. Oral cancer is the fifth mostcommonmalignancyaffectingmenandapproximately 275,000 new cases are diagnosed annually; it has a high mortality.1---4Themostcommonhistologicaltypeissquamous cell carcinoma,2 with a predominance of male patients; about 75%of casesarediagnosedbetween theagesof 50 and70years.5

The mainetiological factorissmoking. Therearemore than 30 carcinogensfound in tobacco andits derivatives, of which the best known are aromatic hydrocarbons and nitrosamines.6 Approximately 90% of individuals withoral cancer smoke cigarettes or pipes, or use other types of tobaccoproducts.Smokersaresixto16timesmorelikely to develop cancer than non-smokers, and 37% of treated individualswhopersistinsmokingdevelopasecondprimary tumororhavediseaserecurrence.7

Alcoholisthesecondmostimportantriskfactor. Approx-imately 75% of individuals with oral carcinoma were alcoholics, and this disease is six times more commonin theseindividualsthaninnon-consumersofalcoholic bever-ages.Thecombinationofalcoholandtobaccoenhancesthe chanceforthedevelopmentoforalcancerbyapproximately 100-fold.6Themaintenanceofhabitsaftertreatmentisalso associatedwithahigherchanceofrecurrenceand develop-mentofasecondprimarytumor.4Otherknownriskfactors include:ultravioletradiationforcancerofthelip, immuno-suppression,infectionbyhumanpapillomavirus(HPV),and poororalhygiene.6

Inmanycountries,suchasBrazil,whenpatientsare diag-nosed,theyfrequentlyalreadyhaveadvancedormetastatic

disease,which, addedtothe aggressiveness ofthe tumor itself, complicates treatment and significantly worsens prognosis.1,8Thetreatmentofthesepatientsismainly sur-gicalandoftenleadstoestheticandfunctionaldeformities, with severe impact on quality of life. For all these rea-sons, thistype of neoplasmis an importantpublic health issue.4

This isapreventable diseasewithachange inlifestyle (especially the discontinuation of smoking and drinking habits)andtreatmentofpremalignantlesionssuchas leuko-plakiaanderythroplasia.1,8,9Themostcommonlyemployed methodinscreeningforearlylesionsisvisualinspectionof theoralcavity(oralexam),whichhasaspecificityofabout 98%.8Thisisanon-invasive,fast,andinexpensivetechnique thatcanbeperformedbymedicalprofessionalsfrom differ-entfields.1

Aimingat reducing the mortalityand morbidityof this disease, several oral cancer prevention campaigns have beenlaunched,whosegoalistoeducatethepopulationat greatestriskofdevelopingthedisease(mainlyalcoholand tobaccoconsumers)andsecondarily,todiagnoselesionsat anearlystage.However,althoughitiscommonsensethat screeningandearlydetectionhavegreatpotentialin fight-ingthedisease,studieshavechallengedthevalidityofthese initiatives.Evidencerelatedtotheeffectivenessof preven-tioncampaignsisstillcontroversialandtheindividualswho areactuallyassessedduringsuchcampaignsmaynot repre-sentthetrueriskgroup,whichis oneofthemainreasons forthisdebate.1,8---11

Methods

Theoral cancerpreventioncampaign hasbeen held annu-allysince2008inSãoBernardodoCampo,stateofSãoPaulo, andiscalled‘‘Abraabocaparaasaúde’’(‘‘OpenyourMouth forOralHealth’’).Itconsistsofafreeoroscopyperformed bytrainedprofessionals(physiciansanddentists) fromthe publichealthnetworktodetectlesionsintheoralmucosa andverbalrecommendations,aswellasdistributionof edu-cational leaflets on oral self-examination and suspicious lesions.Patientsarenotselected,butratherspontaneously seekthecampaignthrough‘‘Poupatempo’’agencies(a one-stop service for citizens who need documents such as ID cards, driver’s licenses, and criminal records. Consumers canalsopayutilitybills,settledebts,anddisputecharges), whichareplacesofgreatpubliccirculation.

Patientswithoralmucosallesionswerereferredfor diag-nosticinvestigationandtreatmentin twoservices:benign lesionstotheDentalSpecialtyCenterandlesionssuspected tobemalignantorpre-malignanttotheServiceofHeadand NeckSurgery.

Allvoluntarypatientshadaformcompletedcomprising identification,demographicdata,andtheoral assessment description. Based on the information collected on this form,thedataweretabulatedandstoredinadatabase with-out identification, so they could be analyzed. Individuals whosmoked at least one cigarettedaily were considered smokers.Moreover,alcoholconsumptionreferredtoweekly or daily ingestion of alcoholic beverages, even in small amounts.Grossdatafromthe2008to2013campaignswere collected.

The numberof people assessed in each campaign was obtainedthroughthefinalreportissuedbythose responsi-blefororganizingthecampaigns.Thecharacteristicsofthe orallesionsfound(malignantorbenign)wereobtainedfrom theservicestowhichpatientswerereferred.However,only demographicdatafromtheyears2008(firstyearofthe cam-paign)and2012(thelastassessableyearofthecampaign) werequantifiedforcomparisonpurposes.Demographicdata fortheyears2009---2011campaignswerenotavailablefrom theHealthSecretariatoftheMunicipality,andthedataof thesixthcampaign(2013)hadnotyetbeentabulatedand thereforewerenotavailableforanalysis.

Results

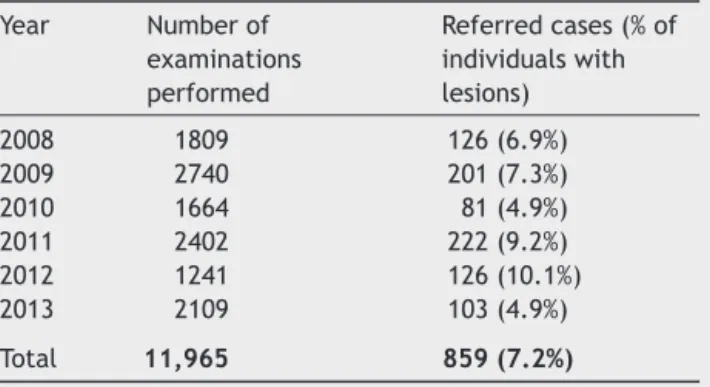

Inthesixassessableyears(Table1),11,965individualswere evaluated.Ofthese,7.2%(859individuals)hadalesionin theoral cavitythatwasconsidered benignaftera second assessmentinreferenceservices.

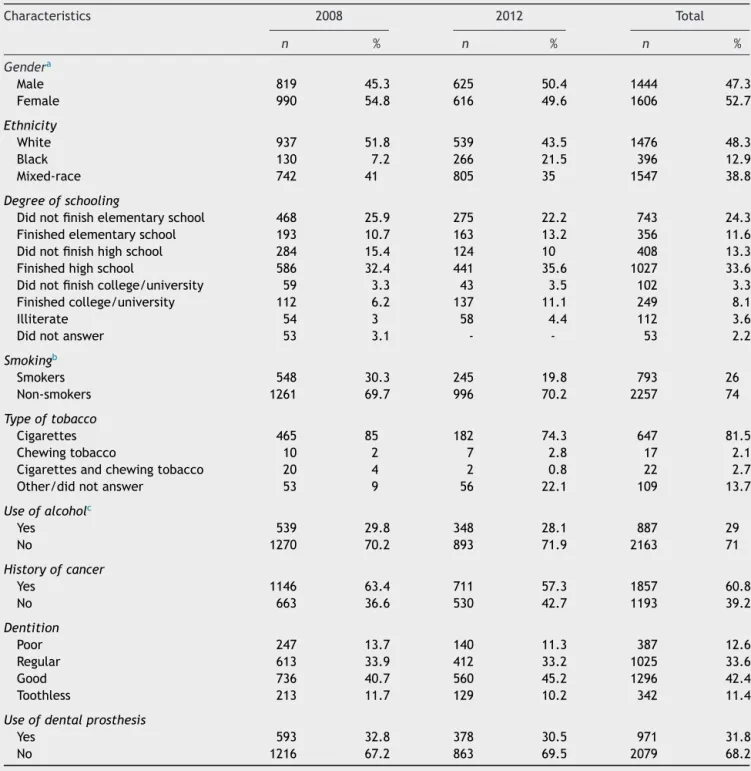

Intheyears2008and2012,1809and1241peoplewere assessed,respectively.The epidemiologicalcharacteristics observed in the individuals who sought the campaigns in theseyearsareshowninTable2.Itshouldbenotedthatthe meanagewas44.1years,withapredominanceofwomen, and 49.2% of individuals had less than 11 years of edu-cation (incomplete high school education). Smokerswere theminority(26%),withthemaintypeoftobaccoproduct beingcigarettes (81.5%),andalcohol consumerswerealso aminority(29%).Themeanperiodsofsmokingandalcohol consumptionwere21.7yearsand22.5years,respectively.

Table1 Numberofexaminationsandreferredcaseswith orallesionsduringcampaigns2008---2012.

Year Numberof examinations performed

Referredcases(%of individualswith lesions) 2008 1809 126(6.9%) 2009 2740 201(7.3%) 2010 1664 81(4.9%) 2011 2402 222(9.2%) 2012 1241 126(10.1%) 2013 2109 103(4.9%) Total 11,965 859(7.2%)

Of theassessed individuals,60.8% had apersonal or fam-ilyhistoryofcancer.Regardingtheconditionoforalhealth, 46.2%hadfairorpoordentalstatusand31.8%woreadental prosthesis.

Discussion

Thepresentstudydemonstratesthatthepopulationatrisk for developing oral cavity cancer is not being effectively reached by the prevention campaign in São Bernardo do Campo,aproblemthatmayalsobeoccurringinother Brazil-iancities.

Analyzingtheresults,weobservedthat7.2%oftreated subjectshadorallesionsreferredforinvestigation,andnone werediagnosedasoral cancerafter asecond assessment. Regarding the population that sought assessment through thecampaigns,thatrepresentsasmallnumberoflesionsin theoralcavity,noneconfirmedasoralcancer.

This finding is consistent with a literature review by Franceschi etal.,10 inwhich the proportionof individuals withsuspiciouslesionsrangedfrom1%to16%,andofthese, most weresmokersand/oralcohol drinkers.Alarge study carried out in Minnesota, in the United States, assessed 23,616individuals,ofwhom10%hadsuspiciouslesions,and of these, 12% had spinocellular carcinoma.12 The largest studytodatewasperformedinIndiabySankaranarayanan etal.,8inwhich87,655patientswereevaluated,which iden-tified5145(5.9%)suspiciouslesions,butwithonly205(0.2%) casesofcarcinomas.Thatis,inthegeneralpopulation,the numberofindividualswhoneedtobeassessedforthe detec-tionofasmallnumberofprecursorlesionsorcarcinomasis proportionallyenormous.

In public health policy, because of the financial and technicalorganizationalcomplexity,evidenceofefficacyin prospectivestudiesisofgreatimportance.8Althoughearly detectionoforalcancerleadstobetterprognosticindices, therearenotenoughunequivocaldatatosupportthe cur-rentpreventionprogramsforthepopulationingeneral.13

Table2 Epidemiologicalcharacteristicsoftheindividualsattendedtointhe2008and2012campaigns.

Characteristics 2008 2012 Total

n % n % n %

Gendera

Male 819 45.3 625 50.4 1444 47.3

Female 990 54.8 616 49.6 1606 52.7

Ethnicity

White 937 51.8 539 43.5 1476 48.3

Black 130 7.2 266 21.5 396 12.9

Mixed-race 742 41 805 35 1547 38.8

Degreeofschooling

Didnotfinishelementaryschool 468 25.9 275 22.2 743 24.3 Finishedelementaryschool 193 10.7 163 13.2 356 11.6 Didnotfinishhighschool 284 15.4 124 10 408 13.3 Finishedhighschool 586 32.4 441 35.6 1027 33.6 Didnotfinishcollege/university 59 3.3 43 3.5 102 3.3 Finishedcollege/university 112 6.2 137 11.1 249 8.1

Illiterate 54 3 58 4.4 112 3.6

Didnotanswer 53 3.1 - - 53 2.2

Smokingb

Smokers 548 30.3 245 19.8 793 26

Non-smokers 1261 69.7 996 70.2 2257 74

Typeoftobacco

Cigarettes 465 85 182 74.3 647 81.5

Chewingtobacco 10 2 7 2.8 17 2.1

Cigarettesandchewingtobacco 20 4 2 0.8 22 2.7 Other/didnotanswer 53 9 56 22.1 109 13.7

Useofalcoholc

Yes 539 29.8 348 28.1 887 29

No 1270 70.2 893 71.9 2163 71

Historyofcancer

Yes 1146 63.4 711 57.3 1857 60.8

No 663 36.6 530 42.7 1193 39.2

Dentition

Poor 247 13.7 140 11.3 387 12.6

Regular 613 33.9 412 33.2 1025 33.6

Good 736 40.7 560 45.2 1296 42.4

Toothless 213 11.7 129 10.2 342 11.4

Useofdentalprosthesis

Yes 593 32.8 378 30.5 971 31.8

No 1216 67.2 863 69.5 2079 68.2

a Meanage:42.5

±15.6years(2008);45.7±15.2years(2012);44.1±15.4years(total).

b Meantimeofsmoking:20.8

±12.6years(2008);22.6±14years(2012);21.7±13.3years(total).

c Meantimeofalcoholconsumption:18±12.4years(2008);27±17.2years(2012);22.5±14.9years(total).

arebeneficialfor thisscreening.1,10,13 Downeretal.13 also observedthatmostprogramswereconductedindeveloped countries,andhadashortdurationandasmallnumberof participants.Althoughthereareexceptions,thisaspect con-tributes to the fact that there areno incontestable data supporting campaigns worldwide,especiallyin developing countries.

Factorsthatdecreasetheeffectivenessofthecampaigns arethelackofinformationaboutthedisease,lackofcontact with the importance of prevention, geographic and/or

economicinaccessibilitytohealthservices,lackofsupport fromfamilyor society/community, andlow adherence by thetargetpopulation.8

possibletoincludedatafrom2009 to2011campaigns,for thesewerenotavailable;however,thecomparativeanalysis oftheyears2008and2012showedverysimilarrelative fre-quenciesand,itisprobablethat,theabsenceofdatafrom otheryearsdoesnotrepresentalargeinformationbias.

One way to improve public strategies of prevention campaigns is to identify the profile of participants and non-participantsin ordertoobtain themaximum possible adherenceandhelpthosewhocannotbebenefited. How-ever,fewdataareavailableonthesubject.Themainstudies on this subject were conducted in developed countries, performed by dental or general practice clinics, whose method of contact is sending letters to invite individuals toparticipatein thecampaign.This system,while useful, isineffectiveinmostdevelopingcountries,wheremuchof thepopulationat risk donothave accesstodental treat-ment,livein remoteareas awayfromlarge cities, or are notreachedbythemailsystem.8Thus,agreatereffortby nationalagenciesforbettercollectionandupdatingofdata onpreventioncampaignsisnecessary.

Thisdifficultyinreachingat-riskgroupsbeginsprecisely withthecharacteristicsofthesegroups.8,13 Themain indi-viduals at risk, smokers and/or alcohol drinkers, are not easilyconvincedtoundergoadiagnostictest.Theadherence of these individuals in oral cancer prevention campaigns isapproximately three-foldlower than thatof individuals notin the riskgroup8,13 The results of this studyindicate alowparticipationofthisgroup(approximately30%ofthe participants).13

Another negative point to be assessed is the risk of reinforcingbad habits.13 For instance, a person tested as having no oral disease may understand that he or she is not sick and thus decide not to quit smoking and/or drinking.10 Additionally, more sensitive methods help to detect oral lesions more accurately; however, the num-ber of unnecessary biopsies and their risks also tend to increase.10

Lowersocioeconomiclevelsarerelatedtopoorer medi-calfollow-up,whichcanbeanotherobstacletohealthcare, especiallyinthecase of Brazil,wheremost ofthe at-risk populationhasloweducationallevel.9 This pointwasalso identifiedin the present study,in which 49.2% of people assessedinthecampaignshadnotfinishedhighschool,with anilliteracyrateof3.6%.

Thisstudyshowedthattheprofileofthepopulationthat sought the prevention campaign does not represent the populationat risk. It is knownthatthe risk groupfor the developmentofcarcinomaoftheoralcavitycorrespondsto men(76% ofcases), age 50---70years, smokers(85%),and heavydrinkers(70%).5Inthe2008campaign,most partici-pantswerefemales(54.8%),withameanageof 42years. Smokersanddrinkersaccountedforonly30%ofthe assess-ments.In2012,thescenariowasverysimilar,suggestingthat fortheotheryears,theprofilewasprobablysimilar.These figuresarealarming,asthetargetpopulationofcancerin theoralcavityisnotbeingreachedbythecampaign.

Thisfactisevenmorealarmingifonetakesinto consid-erationthatSankaranarayananetal.,in2005,8calculated thatvisual assessmentoftheoralcavityisonlyprotective forthepopulationatrisk.

Inthatprospectivestudy,therewasnostatistically signif-icantreductioninmortalityfromoralcancerinthescreened

group,whencomparedwiththenon-screenedgroup. How-ever,amongsmokersanddrinkersonly,thechanceofdeath in the screened group decreased by a relevant 34%. The authors also stated that the visual examination has the capacitytoprevent37,000deathsfromcanceroftheoral cavity;however,toattainsuchpurposes,awiderrangeof the population at risk needstobe reached by prevention campaigns.

To decrease any obstacles and improve the effective-ness of prevention programs in the study carried out in India,8themethodsusedincludedpersonalinvitations,with evaluationsperformedduringhomevisitsbytrained profes-sionals,freeofcharge,inadditiontoprovidinginformation aboutthediseaseandtheimportanceofprevention.Inthis case,theevaluatorssoughtat-riskgroups,andthelatterdid not needtoseek assessment throughthecampaigns.This improvesthepopulationselectionandmakesthecampaign more effective by eliminating obstacles, such as limited mobilityandaccessibility,amongothers.

Toincreasethepost-detectionfollow-upofthelesion,a studybyRamadasetal.(inwhichthemethodalsoconsisted of home visits conductedby professionals) sent lettersto individualsthatdidnotattendthereferralconsultation,and visits were providedtothose thatdid notrespond tothe invitationssentbymail.

Thatstudy had the participation fromvirtually all the individuals towhomthe visualinspection ofthe oral cav-itywasoffered,andsendinglettersincreasedfollow-upby 11%.9 Chacra Jr. et al.14 studied the presence of lesions stainedin toluidineblue inmembers of Alcoholics Anony-mous groups and identified 47.7% of patients with oral lesions,andofthese,almost5%ofcasesofdysplasia.These results are also important to demonstrate that there are methods thatcan beeffective for theevaluation oflarge numbers of individuals, and that they can be adapted to achieve wider adherence by the population at risk and increasetheeffectivenessofthehomevisitstrategy.

The‘‘OpenyourMouthforOralHealth’’campaign, eval-uatedin thisstudy, hassome pointsthatmay need tobe changed. The main one is its strategy: with the current model, the population needs totravel to the examiners, allowingtheemergenceofdifficulties,suchasaccessibility, something thathome visits eliminate. Moreover,it is car-riedoutduringaspecificperiod(oneweekperyear),which maycoincidewithaperiodinwhichpatientsareunableto attend,withouthavinganotheropportunitytoparticipate. The campaign shouldtake placeat different timesof the yearifpossible,althoughallcampaignsaresubjecttothis restriction.

Perhapsthe model to beadopted should be the home visit,whichallowsgreaterparticipationandthepossibility ofdirectingthepreventioncampaigntoat-riskpopulations, asstudies have shown. However,the cost-benefitratio of mobilizing a large contingent of trained professionals to carry out the assessments must be considered. Addition-ally,thereisatendencytohaveagreaterparticipationof women,asproportionallytheyaremoreoftenathomethan men,whoareathigherriskofdevelopingthedisease.10To avoidthissituation,visitsmustbetimedinordertoperform themwhenthemenareathome.

homevisits, suchaspreventioncampaignsagainstdengue fever and Chagas disease, training of community health workerstoperformvisualinspectionoftheoralcavity,and likewise,increasingthenumberoftheseagents.By adopt-ingthestrategyofhomevisits,theexaminerscouldnotonly visitthehomes,butalsogotobars,businesses, factories, andplaceswithpopulationsathighriskofdevelopingcancer oftheoralcavity,especiallyineconomicallydisadvantaged regions.

Preventioncampaignsshouldalsoinvestinincreasingthe population’sknowledge andraisingawarenessand,in this sensethey aresuccessful.They shouldbe directedto at-riskgroupsand/ortheiracquaintancesandfamilymembers, andshould focusoneliminating tobaccoandalcohol con-sumption,aswellastheimportanceofself-examinationof themouthandadequateoralhygiene.1,2Thelackof knowl-edgeabout oral cancer, itssymptoms,and itsrisk factors areofconcern,andcorrelatewithlatediagnosisandpoor prognosis.15

Inadditiontoimplementingmorepubliccampaigns,the governmentcan play an importantrole in terms of legis-lation:cigarettesareveryinexpensiveinBrazil,compared toothercountriesintheworld,whichfacilitatesaccessto tobacco. Taking that into account,the government could increase taxation on the product, in an attempt tolimit access.

The media alsohas an important rolein this scenario. Media campaigns help to increase adherence, and the means of mass communication moreeasily reachthe tar-getpopulationofthesecampaigns.9Thus,television,radio, theinternet,social networks,newspapers,andmagazines should be further explored for both the disseminationof informationonthediseaseandformsofprevention,aswell asinformationonthe campaigns,suchasdatesand loca-tions.

Conclusion

The population that spontaneously seeks the oral cancer prevention campaigns is not the main risk group for the disease.This explainsthelow numberoflesionsdetected and the fact that nomalignancies were diagnosed. Thus, although the campaign is well structured and reaches a large numberofpeople,other formsof preventionshould bedevelopedinordertoreachtherealriskgroupfor this disease.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.SteeleTO,MeyersA. Earlydetectionofpremalignantlesions andoralcancer.OrthopClinNorthAm.2011;44:221---9.

2.Galbiatti AL, Padovani-Junior JA, Maníglia JV, Rodrigues CD, Pavarino ÉC, Goloni-Bertollo EM. Head and neck cancer: causes, prevention and treatment. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:239---47.

3.Montoro JR, Ricz HA, Souza LD, Livingstone D, Melo DH, Tiveron RC, et al. Prognostic factors in squamous cell car-cinoma of theoralcavity. Braz JOtorhinolaryngol. 2008;74: 861---6.

4.CasatiMFM,AltieriJV,VergnhaniniGS,ContreiroPF,Bedenko TG, Kanda JL, et al. Epidemiologia do câncer de cabec¸a e pescoc¸onoBrasil:estudotransversaldebasepopulacional.Rev BrasCirCabec¸aPescoc¸o.2012;41:186---91.

5.Oliveira LR, Ribeiro AS, Zucoloto S. Perfil da incidência e da sobrevida de pacientes com carcinoma epidermóide oral em uma populac¸ão brasileira. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2006;42:385---92.

6.PalmeCE,GullaneJP,GilbertRW.Currenttreatmentoptionsin squamouscellcarcinomaoftheoralcavity.SurgOncolClinN Am.2004;13:47---70.

7.Hashibe M, Boffetta P, Zaridze D, Shangina O, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Mates D, et al. Contribution of tobacco and alcoholto thehigh ratesofsquamous cellcarcinoma ofthe supraglottis and glottis in Central Europe. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:814---20.

8.SankaranarayananR,RamadasK,ThomasG,MuwongeR,Thara S,MathewB,etal.Effectofscreeningonoralcancermortality inKerala,India:acluster-randomisedcontrolledtrial.Lancet. 2005;365:1927---33.

9.RamadasK,ArrossiS,TharaS,ThomasG,JissaV,FayetteJM, etal.Whichsocio-demographicfactorsareassociatedwith par-ticipation inoral cancer screening in the developing world? Resultsfromapopulation-basedscreeningprojectinIndia. Can-cerDetectPrev.2008;32:109---15.

10.Franceschi S, Barzon L, Talamini R. Screening for cancerof the headand neck: ifnot now,when? OralOncol. 1997;33: 313---6.

11.MignognaMD,FedeleS.OralCancerscreening:5minutestosave alife.Lancet.2005;365:1905---6.

12.BouquotJE.Commonorallesionsfoundduringamassscreening examination.JAmDentAssoc.1986;112:50---7.

13.Downer MC, Moles DR, Palmer S, Speight PM. A systematic reviewofmeasuresofeffectivenessinscreeningfororalcancer andprecancer.OralOncol.2006;42:551---60.

14.Chacra J Jr, Lehn CN, Campi JPB, Dedivitis RA, Rapoport A. Detecc¸ão precoce do cancer de cavidade oral pela colorac¸ão com azul de toluidina. RevCol Bras Cir. 1994;21: 57---60.