REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

OfficialPublicationoftheBrazilianSocietyofAnesthesiologywww.sba.com.br

SCIENTIFIC

ARTICLE

Orotracheal

intubation

and

temporomandibular

disorder:

a

longitudinal

controlled

study

Cláudia

Branco

Battistella

a,∗,

Flávia

Ribeiro

Machado

b,

Yara

Juliano

c,

Antônio

Sérgio

Guimarães

a,

Cássia

Emi

Tanaka

a,

Cristina

Talá

de

Souza

Garbim

a,

Paula

de

Maria

da

Rocha

Fonseca

a,

Monique

Lalue

Sanches

aaMorphologyandGeneticsDepartment,EscolaPaulistadeMedicinadaUniversidadeFederaldeSaoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil bAnesthesiology,PainandIntensiveCareDepartment,EscolaPaulistadeMedicinadaUniversidadeFederaldeSaoPaulo,São

Paulo,SP,Brazil

cPublicHealthDepartment,SantoAmaroUniversity,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

Received7May2014;accepted26June2014 Availableonline26October2014

KEYWORDS

Temporomandibular jointdisorders; Myofascialpain syndromes;

Generalanesthesia; Intubation;

Orofacialpain

Abstract

Backgroundandobjectives: Todeterminethe incidenceofsigns andsymptomsof temporo-mandibulardisorderinelectivesurgerypatientswhounderwentorotrachealintubation.

Methods:Thiswasalongitudinalcontrolledstudywithtwogroups.Thestudygroupincluded patients whounderwentorotrachealintubationandacontrolgroup.Weusedthe American AcademyofOrofacialPainquestionnairetoassessthetemporomandibulardisordersignsand symptomsone-daypostoperatively(T1),andthepatients’baselinestatuspriortosurgery(T0) wasalsorecorded.Thesamequestionnairewasusedafterthreemonths(T2).Themouth open-ingamplitudewasmeasuredatT1andT2.Weconsideredapvalueoflessthan0.05tobe significant.

Results:Weincluded71patients,with38inthestudygroupand33inthecontrol.Therewas nosignificantdifference betweenthegroups inage(studygroup:66.0[52.5---72.0];control group:54.0[47.0---68.0];p=0.117)orintheirbelongingtothefemalegender(studygroup: 57.9%;controlgroup:63.6%;p=0.621).AtT1,therewerenostatisticallysignificantdifferences betweenthegroupsintheincidenceofmouthopeninglimitation(studygroup:23.7%vs.control group:18.2%;p=0.570)orinthemouthopeningamplitude(studygroup:45.0[40.0---47.0]vs. controlgroup:46.0[40.0---51.0];p=0.278).AtT2weobtainedsimilarfindings.Therewasno significantdifferenceintheaffirmativeresponsetoalltheindividualquestionsintheAmerican AcademyofOrofacialPainquestionnaire.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mails:cbb4680@yahoo.com.br,contato@indof.com.br(C.B.Battistella).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2014.06.008

Conclusions: In ourpopulation,the incidenceofsignsandsymptomsoftemporomandibular disorderofmuscularoriginwasnotdifferentbetweenthegroups.

© 2014SociedadeBrasileirade Anestesiologia.Publishedby ElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrights reserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Transtornosda articulac¸ão

temporomandibular; Síndromedador miofascial; Anestesiageral; Intubac¸ão; Dororofacial

Intubac¸ãoorotraquealedisfunc¸ãotemporomandibular:estudolongitudinal controlado

Resumo

Justificativaeobjetivos: Determinaraincidênciadesinaisesintomasdedisfunc¸ão temporo-mandibular(DTM)empacientesdecirurgiaeletivasubmetidosàintubac¸ãoorotraqueal.

Métodos: Estudolongitudinalcontroladocomdoisgrupos.Ogrupodeestudoincluiupacientes queforamsubmetidos àintubac¸ãoorotraquealeum grupocontrole.Usamosoquestionário daAcademiaAmericanadeDorOrofacial(AAOP)paraavaliarossinaisesintomasdaDTMno primeiro diadepós-operatório(T1),eosestadosbasaisdospacientesantesdacirurgia(T0) tambémforamregistrados. Omesmoquestionáriofoi usadoapóstrêsmeses(T2).A ampli-tudedaaberturabucalfoimedidaemT1eT2.Consideramosumvalor-pinferiora0,05como significativo.

Resultados: Nototal,71pacientesforamincluídos,com38pacientesnogrupodeestudoe33 nogrupocontrole.Nãohouvediferenc¸asignificativaentreosgruposquantoàidade(grupode estudo:66,0[52,5-72,0];grupocontrole:54,0[47,0-68,0],p=0,117)ougênerofeminino(grupo deestudo:57,9%;grupocontrole:63,6%,p=0,621).NoT1,nãoforamencontradasdiferenc¸as estatisticamentesignificativasentreosgrupos quantoàincidênciadelimitac¸ãodeabertura bucal(grupodeestudo:23,7%vs.grupocontrole:18,2%,p=0,570)ouamplitudedeabertura bucal(grupodeestudo:45,0[40,0-47,0]vs.grupocontrole:46,0[40,0-51,0],p=0,278).Em T2,os resultados obtidosforamsemelhantes.Nãohouvediferenc¸a significativanaresposta afirmativaatodasasperguntasindividuaisdoquestionárioAAOP.

Conclusões: Emnossapopulac¸ão,aincidênciadesinaisesintomasdeDTMdeorigemmuscular nãofoidiferenteentreosgrupos.

©2014SociedadeBrasileira deAnestesiologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todosos direitosreservados.

Introduction

Temporomandibulardisorder(TMD)comprisesanumberof clinical conditions involving the masticatory muscles, the temporomandibularjoint(TMJ)and associatedstructures. ThecommonsignsandsymptomsofTMDareclickingnoises in the TMJ,a limited jaw opening capacity, deviations in the movement patterns of the mandibleand masticatory muscles and TMJ or facial pain.1---3 TMD is, by far, the

mostprevalentofallchronicorofacialpainconditions.4The

prevalenceofTMDamongindividualspresentingatleastone clinicalsignvariesfrom40%to75%.2InBrazil,atleastone

TMD symptom was reportedby 39.2% of the population.5

Sounds in the TMJ and deviations in mouth opening and closingmovementsoccurinapproximately50%ofthe non-patientpopulationandareconsiderednormal,withnoneed fortreatment.6ThemostcommonsubtypeisTMDof

mus-cularorigin,7 anditischaracterizedbylocalizedpainand

tendernessinthemasticatorymuscles.8

During intubation, the TMJ rotation and translation maneuversusedby theanesthesiologisttoachieve a max-imumopening of the patient’s mouth and the atraumatic

passageof an endotracheal tube mayresultindamage to theTMJapparatusduetotheexcessiveforcesbeingapplied eithermanuallyorwiththelaryngoscope.Additionally, dam-agemayoccurduetothelengthoftimethatthestructures are in a ‘‘stressed’’ position. Orotracheal intubation has longbeenconsidered ariskfactor forthedevelopmentor exacerbationofTMDthatincludesfacialpain.9,10

Somestudieshavedescribedchangesinthestructuresof themasticatorysystemafterorotrachealintubation.These changescanbeofeitherarticular11orarticularand

muscu-larorigin.9,12,13 Incontrast,astudyshowedthatintubation

techniques do not represent a risk for the development of TMD.14 An update of the guidelines for the

manage-ment of the difficult airway by the American Society of Anesthesiologistsspecificallyrecommendsthepreoperative assessmentof theTMJfunction.15,16 However,the current

evidence in the literature is based on case reports10,17---20

andsmallstudies.9,11---13,20 Thus,the aimof thisstudy was

Methods

Thiswasalongitudinalcontrolledstudyconductedon elec-tivesurgicalinpatientsfromauniversityhospital.Thestudy wasapprovedbytheinstitutionalResearchEthics Commit-tee underthe number 00595012.1.0000.5505,and all the subjects signed the written informed consent form. We included consecutive patients older than 18 years of age whowere admittedto theintensive care unit(ICU) after elective surgeryunder generalanesthesia. Those patients weredivided into 2 groups. The study group consisted of thepatientswhounderwentorotrachealintubationfor gen-eralanesthesia,andthecontrolgroupincludedthepatients whounderwentanalternateanesthesiaprocedurewithout intubation.Inthecontrolgroup,wealsoincludedpatients inthepostoperativecarewards.Weexcludedthepatients unabletoanswerthe questionnaireortosignthe consent form,thosewithatracheostomyorusingalaryngealmask duringsurgery,thoseundergoingheadornecksurgeriesand thosewithfacialorTMJtraumaorwithprevioustreatment forTMDororofacialpain.

The demographic data, age, gender and duration of theintubationwererecorded.Afterinclusion,thepatients answeredamodifiedTMDscreeningquestionnairefromthe AmericanAcademyofOrofacialPain(AAOP).2This

question-nairehas10 objectivequestions about themost frequent TMDand orofacial pain signsand symptoms. As we could notassessthepatientsbeforesurgery,theywereaskedto answerthequestionsreferringbothtotheirbaselinestatus priortosurgery (T0)andtheir actualpostoperativestatus (T1).Questions 8and 10were notevaluatedbecausethe patientsinthestudycouldnothavethereferralconditions becauseofourexclusioncriteria.

Wealso measuredthe maximummouth opening ampli-tude of these patients with a disposable paper ruler as previouslydescribed.21Wemeasuredthedistancebetween

the upper and lower central incisors while the patients openedtheir mouths. Inprostheses userswhowere with-outthem,wemeasuredthedistancefromtherightcentral incisortotheantagonistalveolaredge,subtracting10mmif theywerepartiallyedentulous.Inthecaseofatotal eden-tulouspatient,we measuredthe distance fromtheupper to lower alveolar edge, subtracting 15mm as previously reported.22 The mouth opening wasmeasured by a single

examiner.The patientsreceived asimilarpaperrulerand instructionsforitsuse.After3months(T2),the question-nairewasreappliedbytelephone,andthemaximummouth openingwasmeasuredbythepatientunderthesame con-ditionsasatT1(withorwithoutprostheses).

Weconsideredameasurementoflessthan40mmtobea mouthopeninglimitation.23Weconsideredthepatientswho

hadoneormorepositiveresponsestotheAAOPscreening questionnairetohaveTMDsignsandsymptoms.

Statisticalanalysis

Thesamplesizewascalculatedbasedonthefrequencyof mouthopeninglimitation(<40mm).Weexpectedthat20% ofthepatientsinthestudygroupwouldhavealimitation whilenoneinthecontrolgroupwouldbelimited. Consider-inganalphaerrorof0.05andapowerof80%,usinga2-sided

test,weestimatedthatwewouldneed35patientsineach group.

Forthestatisticalanalyses,weusedaMann---Whitneytest tocomparethegeneralcharacteristicsandtheamplitudeof themouthopeningbetweenthegroups.AWilcoxontestwas usedtocomparetheamplitudeofthemouthopeningatT1 andT2withinthegroups.TheFisher’sexacttestora chi-squaretestwasusedtocompare thepresenceofamouth opening limitationandthe responsestothe questionnaire betweenthegroups.Wedidadescriptiveanalysistoreport thechangeswithinthegroups,comparingT1andT2,andthe resultswerecomparedusingachi-squaretestcorrectedby Yates.TheSpearmantestwasusedtoassessthecorrelation betweenthelengthofintubationandtheamplitudeofthe mouth openingat T1.Statisticalsignificance wasassumed atp<0.05.AlldatawereanalyzedusingSPSSsoftware11.0 forWindows(SPSSInc.,Chicago,IL,USA).

Results

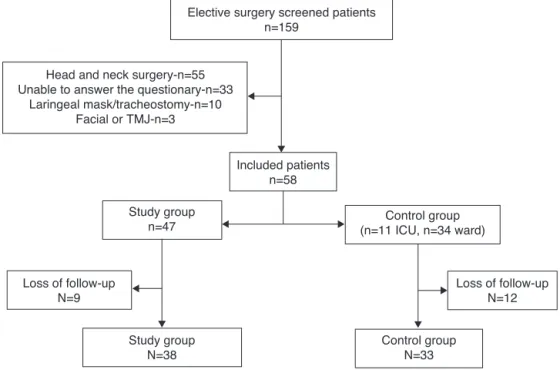

BetweenFebruaryandMay2012,wescreened159patients admitted tothe ICU, and 101 wereexcluded. Another 34 patients fromthewards wereincluded. Thus,92 patients tookthefirstassessmentatT0andT1.For21ofthem,the 3-monthfollow-upwasnotpossible.Thus,ourfinalsample wascomposedof71patients,with38inthestudygroupand 33inthecontrolgroup.The patientflowchartisavailable inFig.1.Therewasnosignificantdifferencebetweenthe groupsinage(studygroup:66.0[52.5---72.0];controlgroup: 54.0 [47.0---68.0]; p=0.117) or in their belonging to the female gender (studygroup: 57.9%; controlgroup: 63.6%; p=0.621).

There wasno statistically significant differencein the incidenceofmouthopeninglimitationswhencomparingthe studygroupwiththecontrolgroupatT1andT2.Whenwe analyzedtheamplitudeofthemouthopening,nodifference wasfoundeitheratT1orT2.Therewasnostatistically sig-nificant differencebetweentheT1andT2 assessmentsof themouthopeningamplitudesineithergroup.Theseresults areshowninTable1.Therewasnocorrelationbetweenthe lengthofintubationandtheamplitudeofthemouthopening atT1(r=0.07;p=0.671).

Therewasnosignificantdifferencebetweenthegroups intheaffirmativeresponsestoallindividualquestionsfrom the questionnaire assessment of TMD at T0, T1 and T2 (Table2).The rateof apositiveanswer wasnotdifferent whenwecomparedthestudygroupwiththecontrolgroup (T0: 19 (50.0%) vs. 11 (33.3%); p=0.155; T1: 15 (39.5%) vs. 11 (33.3%); p=0.592; T2: 19 (50.0%) vs. 15 (45.5%); p=0.702).Whenweanalyzedonlythepatientswithno pos-itive responses at T0 (study group: n=19; control group: n=22),therewasnosignificantdifferenceintherateofnew positiveresponsesatT1(5(26.3%)vs.4(18.2%);p=0.709). Similar results were found at T2 (8 (42.1%); 6 (27.2%); p=0.318).

Discussion

Elective surgery screened patients n=159

Study group n=47

Included patients n=58

Loss of follow-up N=9

Study group N=38

Control group N=33

Loss of follow-up N=12 Control group

(n=11 ICU, n=34 ward) Head and neck surgery-n=55

Unable to answer the questionary-n=33 Laringeal mask/tracheostomy-n=10

Facial or TMJ-n=3

Figure1 Studyflowchart.TMJ,temporomandibularjoint.

inelectivesurgeriescomparedwiththepatientswho under-went surgerywithout intubation. Weassessed these signs andsymptomsusingbothanobjectivemeasurementofthe mouth opening and the subjective answers given by the patientsintheAAOPscreeningquestionnaire.

Our findings areconsistent with a previous study that did not associate intubation with the onset or worsening of TMD.14 However,more recent studies have shown that

theonsetor progressionof TMDwasassociatedwith oro-trachealintubation.9,11---13Themajorityofthesestudiesdid

nothave acontrolgroup,usedasubjective assessmentof TMD and did not consider the different subtypes of TMD intheir analyses. Muscle-related conditionsrepresent the largestsubtypeamongthevariousdisordersgroupedunder theTMDdefinition,whichisresponsible for50---70%ofthe cases.In25%ofthesepatients,themasticatorymusclesare

Table1 DemographicdataandTMDcharacteristic.

Variable Studygroup

(n=38)

Controlgroup (n=33)

pa

Age,yrs 66(52.5---72) 54(47---68) 0.117

Femalegender 22(57.89%) 21(63.63%) 0.602

Typeofsurgery

Gastrointestinal 16(42.1%) 0

---Gynecological 1(2.63%) 14(42.42%)

---Urology 2(5.26%) 11(33.3%)

---Vascular 3(7.89%) 2(6.06%)

---Orthopedic 6(15.78%) 6(18.18%)

---Neurologic 6(15.78%) 0

---Thoracic 2(5.26%) 0

---Other 2(5.26%) 0

---Mouthopeninglimitation

T1 9(23.7) 6(18.2%) 0.570

T2 10(26.3%) 5(15.2%) 0.246

Mouthopeningamplitude

T1 45.0(40.0---47.0) 46.0(40.0---51.0) 0.278 T2 42.0(36.25---50.0)b 50.0(40.0---52.0)b 0.128

T1,postoperativeperiod;T2,3monthsfollow-up.Resultsareexpressedasthemedian±firstquartile−thirdquartileoraspercentages, asappropriate.

a Chi-squaretest,Student’sttestorMann---Whitneytest.

Table2 AAOPscreeningquestionnaireforTMDusedwithpatientswhounderwentgeneralanesthesiawithintubation(study) andwithoutintubation(control)beforesurgery(T0),aftersurgery(T1)and3monthsaftersurgery(T2).

AmericanAcademyofOrofacialPain---questions Groupa Rateofpositiveanswersb

T0 T1 T2

1---Doyouhavedifficulty,pain,orbothwhen openingyourmouth,forinstance,whenyawning?

Control 0(0.0) 0(0.0) 1(3.0) Study 0(0.0) 0(0.0) 2(5.3) 2---Doesyourjaw‘‘getstuck’’,‘‘locked’’or‘‘go

out’’?

Control 0(0.0) 0(0.0) 0(0.0) Study 0(0.0) 0(0.0) 1(2.6) 3---Doyouhavedifficulty,pain,orbothwhen

chewing,talking,orusingyourjaws?

Control 0(0.0) 0(0.0) 0(0.0) Study 0(0.0) 1(2.6) 0(0.0) 4--- Areyouawareofnoisesinthejawjoints? Control 5(15.1) 4(12.1) 4(12.1)

Study 8(21.0) 4(10.5) 6(15.8) 5---Doyourjawsregularlyfeelstiff,tight,or

tired?

Control 2(6.1) 2(6.1) 4(12.1) Study 3(7.9) 6(15.8) 2(5.3) 6---Doyouhavepaininorneartheears,temples,

orcheeks?

Control 1(3.0) 2(6.1) 2(6.1) Study 2(5.3) 2(5.3) 0(0.0) 7---Doyouhavefrequentheadaches,neckaches,

ortoothaches?

Control 6(18.2) 5(15.2) 12(36.4) Study 12(31.6) 11(28.9) 18(47.4) 8---Haveyouhadarecentinjurytoyourhead,

neck,orjaw?

Control --- ---

---Study --- ---

---9---Haveyoubeenawareofanyrecentchangesin yourbite?

Control 0(0.0) 0(0.0) 1(3.0) Study 0(0.0) 1(2.6) 3(7.9) 10---Haveyoubeenpreviouslytreatedfor

unexplainedfacialpainorajawjointproblem?

Control --- ---

---Study --- ---

---T0,beforesurgery;T1,aftersurgery;T2,3monthfollow-up.

aControlgroup,n=33;studygroup,n=38. b Allcomparisonswerenon-significant.

theprincipalsourceofpain.24,25Anotherrecentstudyalso

showedthat in 31.4---88.7% of all cases of TMD,it wasof muscularorigin.26Thosepatientshadpainasthemain

com-plaintleadingtoalimitationofmandibular movement.In our study,we not only included a control group but also usedthemouthopeningasourprimarymeasuredendpoint as it allowed an objective assessment of TMD. The high meanageofourpopulationmayhavecontributedtoa fail-uretodetectthesignsandsymptomsofTMD.Aspreviously reported,TMDismoreprevalentinyoungandmiddle-aged adults,7althoughtherearealsodatasuggestingthatolder

patientsmaymoreoftenhaveobjectivesignsandsymptoms ofTMD.27

Themouthopeningamplitudewasnotdifferentbetween the groups either at T1 or T2. These results are consis-tent with previous findings in which a limitation wasnot observed,9,14althoughinanotherreport,areductioninthe

maximumopeningwasfoundin66%ofpatientsthedayafter anesthesiawithintubation.13 Oneofthepossible

explana-tions for this absence of a limitation at T1 is the use of analgesicsduring the ICU stay aspainis oneof the most importantlimitingfactorsformovement.Ourmeasurements atT2werealsonotdifferentbetweenthegroups.Thelack of an association between mouth opening and intubation timereinforcestheassumptionthatthereisnodamageto theTMJandassociatedstructuresboth immediatelyafter surgeryandafterthreemonths.

TMD is considered a disease of multifactorial etiology, and several validated methods have been developed to assesspatientswithsuspectedTMD.23,28---30 However,these

criteria are extensive and difficult to apply in clinical practice. Therefore,more concise instruments have been developed tofacilitate the assessment of TMD.31---33 Given

the unfavorable condition of the patients after surgery, lyingbedriddenandrecovering,weadoptedtheAAOP ques-tionnaireasausefulandfeasiblepre-assessmentforTMD, especiallyfortheevaluationofmyogenicdisordersand mus-cle hyperactivity.34,35 Using this tool, we found that the

proportion of asymptomatic patients both preoperatively and after three months was unchanged in both groups. Consideringthehighsensitivityofthequestionnaire,these resultsaresound.Whenweevaluatedeachquestion individ-ually,weobservedahigherfrequencyofpositiveanswerson questions4,5,6and7forboththestudyandcontrolgroups. Onquestion4,regardingthepresenceofjointsounds,a pos-sible explanationis the highprevalence of jointnoises in olderpopulations27andthelackofspecificityofthis

param-eterinthegeneralpopulation.6Similarissuescanberaised

about question7asheadacheandneckpainarealsovery prevalentconditionsinthegeneralpopulation.Thesimilar incidenceinthecontrolgroupsuggeststhatthesepositive answersarenotassociatedwiththeintubationprocedure. SuchsymptomsarecloselyassociatedwithTMDbutcannot bethesoledeterminerofthedisease.

evaluationsurvey,itshouldberegardedasapre-screening and not a diagnostic tool. We also had some limitations. Wedidnotmeasurethemouthopeningbeforesurgery,and ourassessmentofthepatients’preoperativeconditionwas self-reportedbythepatientsaftersurgeryusingtheAAOP questionnaire. The mouth opening amplitudeat 3 months wasdeterminedbythepatientsthemselvesandnotbythe investigators. Although this might have resulted in some bias, this seems to be a reliable measurement, as previ-ouslyreportedbyothers.21Wealsodidnotevaluateyounger

patientsoremergencyintubations.

The present study was intended to contribute to the understandingofthesymptomaticconsequencesof orotra-chealintubationandtheincidenceofTMDinelectivesurgery patientsbecausethe literatureis scarcein thisfield.The resultsdonotpoint toanegativeeffectofthisprocedure becauseourcontrolgrouphadasimilarfrequencyofsigns and symptoms. Furtherstudies shouldbe conducted with largersample sizesandlongerfollow-upstoconfirmthese findings.

Authorship

CB Battistella, study design, conduct of the study, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. FR Machado,YJuliano,CETanaka,CTSGarbim,PMRFonseca, andMLSanches,studydesign,dataanalysis,andmanuscript preparation.ASGuimarães,manuscriptpreparation.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

WethankAmericanJournalExpertsforreviewingtheEnglish versionofourmanuscript.

References

1.Carlsson GE, Magnusson T, Guimarães AS. Tratamento das Disfunc¸õesTempomandibularesnaclínicaodontológica.1sted. SãoPaulo:Quintessence;2006.

2.DeLeeuwR.Orofacialpain:guidelinesforassessment, diagno-sisandmanagement.4thed.Chicago:QuintessencePublishing; 2008.

3.SessleBJ.Theorofacialpainpublicationprofile.JOrofacPain. 2008;22:177.

4.DworkinSF.TheOPPERAstudy:actone.JPain.2011;12:T1---3.

5.Gonc¸alvesDA,DalFabbroAL,CamposJA,etal.Symptomsof temporomandibulardisordersinthepopulation:an epidemio-logicalstudy.JOrofacPain.2010;24:270---8.

6.DworkinSF,HugginsKH,LeRescheL,etal.Epidemiologyofsigns andsymptomsoftemporomandibulardisorders:clinicalsignsin casesandcontrols.JAmDentAssoc.1990;120:273---81.

7.ScrivaniSJ,KeithDA,KabanLB.Temporomandibulardisorders. NEnglJMed.2008;359:2693---705.

8.ErnbergM, Hedenberg-MagnussonB, AlstergrenP,et al. The levelofserotonininthesuperficialmassetermuscleinrelation tolocalpainandallodynia.LifeSci.1999;65:313---25.

9.Martin MD, Wilson KJ, Ross BK, et al. Intubation risk fac-tors for temporomandibular joint/facial pain. Anesth Prog. 2007;54:109---14.

10.Oofuvong M. Bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocations during induction of anesthesia and orotracheal intubation. JMedAssocThai.2005;88:695---7.

11.RodriguesET,SuazoIC,GuimarãesAS.Temporomandibularjoint soundsanddiscdislocationsincidenceafterorotracheal intuba-tion.ClinCosmetInvestDent.2009;1:71---3.

12.Agrò FE, Salvinelli F, Casale M, et al. Temporomandibu-lar joint assessment in anaesthetic practice. Br J Anaesth. 2003;50:707---8.

13.LippM,vonDomarusH,DaubländerM,etal.Effectsof intuba-tionanesthesiaonthetemporomandibularjoint.Anaesthesist. 1987;36:442---5.

14.TaylorRC, WayWL,HendrixsonRA.Temporomandibular joint problemsinrelationtotheadministrationofgeneral anesthe-sia.JOralSurg.1968;26:327---9.

15.American SocietyofAnesthesiologists TaskForceon Manage-ment. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway:anupdatedreportbytheAmerican Societyof Anes-thesiologistsTaskForceonManagementoftheDifficultAirway. Anesthesiology.2003;98:1269---77.

16.BenumofJL,AgròFE.TMJassessmentbeforeanaesthesia.BrJ Anaesth.2003;91:757.

17.SiaSL,ChangYL,LeeTM,etal.Temporomandibularjoint dislo-cationafterlaryngealmaskairwayinsertion.ActaAnaesthesiol Taiwan.2008;46:82---5.

18.Wang LK, Lin MC, Yeh FC, et al. Temporomandibular joint dislocation during orotracheal extubation. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan.2009;47:200---3.

19.Small RH, Ganzberg SI, Schuster AW. Unsuspected temporo-mandibularjointpathologyleadingtoadifficultendotracheal intubation.AnesthAnalg.2004;99:383---5.

20.Gould DB, Banes CH. Iatrogenic disruptions of right tem-poromandibular joints during orotracheal intubation causing permanentclosedlockofthejaw.AnesthAnalg.1995;81:191---4.

21.SaundDS,PearsonD,DietrichT.Reliabilityandvalidityof self-assessment of mouth opening: a validation study. BMC Oral Health.2012;12:48.

22.Camargo HA, Ribeiro JF. Correlac¸ão entre comprimento da coroa e comprimento total do dente em incisivos, caninos e pré-molares, superiores e inferiores. Rev Odont UNESP. 1991;20:217---25.

23.DworkinSF,LeRescheL.Researchdiagnosticcriteriafor tem-poromandibulardisorders:review,criteria, examinationsand specifications,critique.JCraniomandibDisord.1992;6:301---55.

24.Cairns BE.Pathophysiologyof TMDpain --- basicmechanisms and theirimplications for pharmacotherapy. J OralRehabil. 2010;37:391---410.

25.StohlerCS.Muscle-relatedtemporomandibulardisorders.J Oro-facPain.1999;13:273---84.

26.Reiter S, Goldsmith C, Emodi-Perlman A, et al. Masti-catory muscle disorders diagnostic criteria: the American AcademyofOrofacialPainversustheresearchdiagnostic cri-teria/temporomandibulardisorders(RDC/TMD).JOralRehabil. 2012;39:941---7.

27.SchmitterM,RammelsbergP,HasselA.Theprevalenceofsigns andsymptomsoftemporomandibulardisordersinveryold sub-jects.JOralRehabil.2005;32:467---73.

28.TrueloveEL,SommersEE,LeRescheL,etal.Clinicaldiagnostic criteriaforTMD:newclassificationpermitsmultiplediagnoses. JAmDentAssoc.1992;123:47---54.

29.HelkimoM.Studiesonfunctionanddysfunctionofthe masti-catorysystem.II:indexforanamnesticandclinicaldysfunction andocclusalstate.SvenTandlakTidskr.1974;67:101---21.

31.Fonseca DM, Bonfate G, Valle AL, et al. Diagnóstico pela anamnesedadisfunc¸ãocraniomandibular.RevGauchaOdontol. 1994;42:23---8.

32.OkesonJP.AmericanAcademyofOrofacialPain.Orofacialpain: guidelinesforassessment,diagnosisandmanagement.Chicago: Quintessence;1996.

33.Stegenga B, de Bont LG, de Leeuw R, et al. Assessment ofmandibularfunction impairmentassociatedwith temporo-mandibular joint osteoarthrosis and internal derangement. JOrofacPain.1993;7:183---95.

34.Diniz MR, Sabadin PA, Leite FP, et al. Psychological fac-tors related to temporomandibular disorders: an evaluation ofstudentspreparingforcollegeentranceexaminations.Acta OdontolLatinoam.2012;25:74---81.