w w w . e l s e v i e r . e s / r p t o

Journal

of

Work

and

Organizational

Psychology

The

“I

believe”

and

the

“I

invest”

of

Work-Family

Balance:

The

indirect

influences

of

personal

values

and

work

engagement

via

perceived

organizational

climate

and

workplace

burnout

Lily

Chernyak-Hai

∗,

Aharon

Tziner

NetanyaAcademicCollege,Israel

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received9May2015

Accepted24November2015

Availableonline10February2016

Keywords:

Work-familybalance

Work-familyconflict

Values

Organizationalclimate

Workengagement

Burnout

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

BasedonSchwartz’s(1992,1994)HumanValuesTheoryandtheConservationofResourcesTheory

(Hobfoll,1988,1998,2001),thepresentresearchsoughttoadvancetheunderstandingofWork-Family

BalanceantecedentsbyexaminingpersonalvaluesandworkengagementaspredictorsofWork-Family Conflictviatheirassociationswithperceivedorganizationalclimateandworkburnout.Theresultsof twostudiessupportedthehypotheses,andindicatedthatperceivedorganizationalclimatemediatedthe relationsbetweenvaluesofhedonism,self-direction,power,andachievementandWork-Family Con-flict,andthatworkburnoutmediatedtherelationsbetweenworkengagementandWork-FamilyConflict. TheoreticalandpracticalimplicationsregardingindividualdifferencesandexperiencesofWork-Family Balancearediscussed.

©2016ColegioOficialdePsicólogosdeMadrid.PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.U.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

El

“creo”

y

el

“invierto”

del

conflicto

trabajo-familia:

influencias

indirectas

de

los

valores

personales

y

la

implicación

en

el

trabajo

a

través

de

la

percepción

del

clima

organizacional

y

del

agotamiento

emocional

en

el

trabajo

Palabrasclave:

Equilibriotrabajo-familia

Conflictotrabajo-familia

Valores

Climaorganizacional

Implicaciónlaboral

Agotamientoemocional

r

e

s

u

m

e

n

SiguiendolaTeoríadelosValoresHumanos(Schwartz,1992,1994)yladelaConservacióndeRecursos

(Hobfoll,1988,1998,2001),estetrabajopretendeavanzarenelconocimientodelosantecedentesdel

equilibriotrabajo-familiamedianteelanálisisdelosvalorespersonalesylaimplicacióneneltrabajo comopredictoresdelconflictotrabajo-familiaatravésdesuasociaciónconlapercepcióndelclima organizacionalyelagotamientoemocionaleneltrabajo.Losresultadosdedosestudiosrespaldanlas hipótesis,indicandoquelapercepcióndelclimaorganizacionalmediatizalarelaciónentrevaloresde hedonismo,autodirección,poderylogroyconflictotrabajo-familiayqueelagotamientoemocionalen eltrabajomediatizalarelaciónentreimplicaciónlaboralyconflictotrabajo-familia.Secomentanlas implicacionesteóricasyprácticasrelativasalasdiferenciasindividualesyexperienciasdelequilibrio trabajo-familia.

©2016ColegioOficialdePsicólogosdeMadrid.PublicadoporElsevierEspaña,S.L.U.Esteesun artículoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor:SchoolofBehavioralSciences,NetanyaAcademicCollege,Israel.

E-mailaddress:lilycher@netanya.ac.il(L.Chernyak-Hai).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2015.11.004

1576-5962/©2016Colegio Oficialde PsicólogosdeMadrid. Publishedby ElsevierEspaña,S.L.U. Thisis an openaccessarticle underthe CCBY-NC-ND license

WFC Personal values

(mainly openness to change and self-enhancement values)

Perceived Organizational Climate

Work

Engagement Burnout

Figure1. ResearchModel:TheIndirectInfluencesofPersonalValuesandWork

EngagementviaPerceivedOrganizationalClimateandBurnout.

Pastresearchhasshownthatworkmayinterferewiththefamily

andthatthefamilymayinterferewithwork(e.g.,Amstad,Meier,

Fasel,Elfring,&Semmer,2011;Frone,2000;Judge,Ilies,&Scott,

2006).Thepresentpaperpurportstomakeseveralcontributions

toadvancingtheunderstandingofWork-FamilyBalance (WFB)

antecedentsby clarifyingtherelationshipsbetweenemployees’

valuesand workengagement,and Work-FamilyConflict(WFC).

First, we assessedthe way personal values predictWFC, while

examiningwhethervaluesaffectthefavorablenessofemployees’

perceptionsoforganizationalclimateandsubsequentexperiences

ofWFC.Second,weexploredthecontributionofemployees’work

engagementviaitsinfluencesonworkburnout(for theoverall

researchmodelseeFigure1).

Work-FamilyConflict

Work-FamilyConflict(WFC)referstoanemployee’sexperience

thathisorherworkpressuresoreffortstooptimizejob

require-mentsinterferewiththeabilitytomeetfamilydemands(Frone,

2000;Judgeetal.,2006),alsoaddressedasworkinterferencewith

family (WIF)and family interferencewith work(FIW) (Amstad

etal.,2011).Work-FamilyConflictisthetermmostcommonlyused

intheliteraturetodescribethisphenomenon,althoughthetrend

todayistofocusthediscourseonWork-FamilyBalanceratherthan

Conflict.

Recentmeta-analysesofWFCpointedtoseveralworkplaceand

personal variables as its antecedentsources suchas task

vari-ety,jobautonomy,family-friendlyorganizationalclimate/policies,

role conflict and ambiguity, role overload, time demands, job

involvement, work centrality, organizational support,

family-(un)supportivesupervision,coworkersupport,individualinternal

locusofcontrol,negativeaffectandneuroticism,family

central-ity, family social support, and family climate (Michel, Kotrba,

Mitchelson,Clark,&Baltes,2011).Moreover,genderdifferences

werefound,indicatingthatworkplacefactorssuchasshiftwork,

jobinsecurity,andconflictswithcoworkersorsupervisoronthe

onehandandresponsibilityforhousekeepingorcaringforfamily

membersontheotherhandweresignificantfactorscontributingto

WFCamongmen.Forwomen,physicaldemands,overtimework,

commutingtime towork,andhavingdependentchildren were

mainWFCengenderingfactors(Jansen,Kant,Kristensen,&Nijhuis,

2003).

PastresearchhasrecognizedWFCasanimportantfactorthat

affectsnotonlyemployees’well-beingbutalsotheiremployers’

(Kossek,Baltes,&Matthews,2011;Lapierreetal.,2008),andhas

beendemonstratedtohavedetrimentalimpactondiverse

work-relatedoutcomessuchasburnout,fatigue,andneedforrecovery

fromwork(Bacharach,Bamberger,&Conley,1991;Kinnunen& Mauno,1998),productivity,workperformance,riskofaccidents,

interpersonalconflictsatwork,turnoverrates,maritalsatisfaction,

andphysical and mental healthconditions (Allen,Herst,Bruck,

&Sutton,2000;Barnett,Raudenbush,Brennan,Pleck,&Marshall, 1995;Frone,2000;Jansenetal.,2006;Judgeetal.,2006).Onthe

otherhand,whenWFCisreduced,employeesexhibitgreaterjob

satisfaction, affective organizational commitment,less turnover

intentions(Butts,Caspar,&Yang,2013),andreportgreater

fam-ilysatisfactionaswellasoveralllifesatisfaction(Lapierreetal.,

2008).Specificallyrelevanttothepresentworkistheroleof

indi-vidualdispositionsaspredictorsofwork-familyconflict.Examples

ofsuchpersonalfactorsareinternallocusofcontrol,negativeaffect,

andneuroticism(Allenetal.,2012).

Followingthislineofresearch,thepresentinvestigationsought

toshedfurtherlightontheroleofindividualpsychological

orien-tationsinWFC,borrowingthepersonalvaluesperspectivealong

withthenotionofworkengagement.Inotherwords,weaimedto

examinewhetheremployees’valuesandworkengagementmay

explainindividualdifferencesin theexperiencesofconflictand

balancebetweenworkplacerequirementsandfamilypressures.

PersonalValues

Awidelyacknowledgedtheoryofindividualvariables which

hasinspiredaconsiderablenumberofstudiesisSchwartz’s(1992,

1994) theoryof tenbasichumanvalues:“openness tochange”

values(hedonism,stimulation,andself-direction),“conservation”

values(conformity,tradition,andsecurity),“self-transcendence”

values (universalismand benevolence), and“self-enhancement”

values(achievement andpower). Thebasicvaluesexplain

indi-vidualdecision-making,attitudes,andbehavior,definedasbeliefs

chargedwithaffect,andreflectdesirablegoalsunspecifiedto

cer-taincontextsoractions,functionaspersonalstandards,andare

orderedbyimportancerelativetooneanother(Schwartz,2012).

AccordingtoSchwartz,thetenvaluesareuniversalvalues,andyet

individualsandgroupsmaydifferintherelativeimportancethey

attributetothem.Furthermore,giventhedifferentpsychological

meaningofthetenvalues,someofthemconflictwithoneanother

(e.g.,benevolenceandpower),whereasothersarecompatible(e.g.,

conformityandsecurity)(Schwartz,1992,2006,2012).Schwartz’s

valueswerefoundtohaveimplicationsonvariousorganizational

factors such as citizenship behaviors directed toward

individ-uals(OCB-I)andtowardthegroup(OCB-O)(Arthaud-Day,Rode,

& Turnley, 2012; Seppälä, Lipponen, Bardi, & Pirttilä-Backman,

2012), preferences for transformational and transactional

lead-ership behaviors (Fein, Vasiliu, & Tziner, 2011), perceptions of

relational-typecontracts(Cohen,2012),andworkplace

commit-ment(Cohen,2011).Pastresearchhasindicatedthatvaluesshould

beconsideredwhenexaminingexperiencedwork-familyconflict

(Carlson&Kacmar,2000;Smelser,1998),astheymayexplainwhy

certainindividualsaremorepronetoexperienceWFCwhileothers,

insimilarcircumstances,arenot.Forexample,materialisticvalues

werefoundtoberelatedtohigherwork-familyconflict(Promislo,

Deckop,Giacalone,&Jurkiewicz,2010),andhighWFCwasfound

amongemployeescharacterizedby“obsessivepassion”towards

work(Caudroit,Boiche,Stephan,LeScanff,&Trouilloud,2011).

Inthepresentresearch,wereferredtoSchwartz’s(1992,1994)

basichuman values. We addressedthese values as

psychologi-calpre-dispositionsthatmayincreasethepotentialtoexperience

work-family conflict. Specifically, we predicted that given the

psychological meaning embedded in the different values,

per-sonal valueswhich are egocentricand indicative ofwillingness

toachieve-opennesstochangeandself-enhancementvalues(i.e.,

hedonism, stimulation,self-direction, power, and achievement)

would be especially relevant to WFC, as such values may be

expressedinwillingnesstoexcelandremainincontrolofbothwork

andfamilydemands.Specifically,followingpastresearchon

pos-itiverelationsbetweenmaterialisticvaluesandincreasedpassion

2010),weexpectedthatthesevalueswouldpositivelypredictWFC.

Accordingly,wehypothesizedthat:

Hypothesis1.Therewillbeasignificantpositiverelationbetween

personalegocentricvaluesandWFC:employeescharacterizedby

highlevelsof hedonism,stimulation,self-direction, power,and

achievementpersonalvalueswillexpresshigherlevelofWFC

rela-tivelytothosecharacterizedbylowlevelsofthesevalues.Valuesof

conformity,tradition,security,universalism,andbenevolencewill

belessrelatedtoWFC.

OrganizationalClimate

Itis reasonabletoassumethat personalvalues donotaffect

work-family balance in isolation of organizational perceptions.

Recent meta-analyses indicated that organizational variables

indicativeof thesupportgiven totheemployees,suchas

man-agerialsupportandperceivedorganizationalwork-familysupport,

haveclearrelationswithwork-familyconflict.ThereportsofWFC

arelowerwhen theemployeesperceivethattheirorganization

caresaboutreducingwork-familyconflictsandsupportsthe

abil-itytobalanceworkandfamilydemands(Kossek,Pichler,Bodner,

&Hammer,2011).Similarly,additionalcharacteristicthatwe

con-sideredrelevanttoemployees’experienceofwork-familybalance

istheoverallorganizationalenvironment or“organizational

cli-mate”.Organizationalclimateconcernsemployees’perceptionsof

thesocial climateina workplace,relevant toitspolicies,

prac-tices,andprocedures(Schneider,2000;Schulte,Ostroff,&Kinicki,

2006),andthereforeamultidimensionalimpressionthe

employ-eesformoftheirworkplacewhich reflectstheirimpressions of

thebehaviorsthatareexpectedandrewarded(Armstrong,2003;

ZoharandLuria,2005).Specifically,LitwinandStringer(1968)

dif-ferentiatedbetweenninedimensionsoforganizationalclimate:(1)

structure-employees’feelingsabouttheorganizationalconstraints,

amountofrules,regulations,andprocedures;(2)responsibility

-employees’feelingssuchas“beingyourownboss”andnot

hav-ingtodouble-checkpersonaldecisions;(3) reward-employees’

feelingsthattheorganizationemphasizespositiverewardsrather

thanpunishments,andtheperceivedfairnessofpromotion

poli-cies;(4)risk-employees’feelingsaboutriskinessorchallengeinthe

job/organization;(5)warmth-feelingsofgeneralgoodfellowship

attheworkplace,andtheprevalenceoffriendlyandinformalsocial

groups;(6)support-theperceivedhelpfulnessofmanagersand

otheremployees,andemphasisonmutualsupport;(7)standards

-theperceivedimportanceofimplicitandexplicitgoals,and

perfor-mancestandards;(8)conflict-thefeelingthatmanagersandother

workersareopentodifferentopinions,andemphasisisplacedon

gettingproblemsoutintheopenratherthanignoringthem;and(9)

identity-employees’feelingsthattheybelongtotheorganization

andthattheyarevaluablemembersofaworkingteam.

Eachofthesedimensions,aswellasanoverallimpressionof

organizationalclimate,mayhaveimmediateinfluenceon

employ-ees’experiencesoftheabilitytobalancebetweenworkandfamily

requirements. For example, organizational climate perceptions

werefoundtoaffectemployees’levelsofstress,jobsatisfaction,

commitment,andperformance,which,inturn,haveimplications

forproductivity(Ostroff,Kinicki,&Tamkins,2003;Schulteetal.,

2006).The“support”dimension,i.e.,supervisorsupportand

orga-nizationsupport,werefoundtoberelatedtowork-to-family

con-flict(Carlson&Perrewé,1999;Kossek,Pichleretal.,2011;VanDer

Pompe&Heus,1993),andrelationswerefoundbetween

employ-ees’sharedperceptionsofanorganization’svalueandwork-family

supportanddiminishedWFC(Major,Fletcher,Davis,&Germano,

2008).Followingthislineoffindings,inthepresentresearchwe

drewontheassumptionthatnegativeorganizationalclimate

per-ceptionsreflectedinlowerjobsatisfaction,lowerproductivity,and

lowerperceptionsoforganizationalsupportmayraiseemployees’

dissatisfactionwiththeirfunctioningatwork,increasingthe

ten-sionbetweenworkandfamily,astheystrivetofulfillbothworkand

familydemands.Therefore,inthepresentresearchwepredicted

that perceivedorganizational climatewouldbeassociated with

employees’experiencesofwork-familyconflictand/orbalance.

Hypothesis2.Therewillbeanegativerelationbetweenthe

favor-abilityofperceivedorganizational climateand WFC:employees

characterizedbyunfavorableperceptionsoforganizationalclimate

willexpresshigherlevelofWFCrelativelytothosecharacterized

byfavorableorganizationalclimateperceptions.

Moreover,weassumedthatperceptionsoforganizational

cli-matewould beinitiallyaffectedbyemployees’personalvalues.

Asemployees’ values werefoundto affecttheirperceptions of

different organizational factors (e.g., perceptions of

relational-typecontractsand workplacecommitment;Cohen,2011,2012)

we expected to find that the values would also affect overall

perceptions of organizational climate. Specifically, we assumed

thatorganizationalclimatecomponents–constraints,rules,

reg-ulations, procedures, challenges, and goals, as wellas rewards,

relationswithco-workers,andfeelingsofbelongingtothe

orga-nization,mightbeaffectedbyahighlevelofegocentricpersonal

valuesemphasizingambitionandpersonalgood.Wepredictedthat

thisinfluencewouldbenegative,supposingthatsuchvaluesmay

increasetheemployee’scriticismoforganizationalpracticesand

environment.Insum,inthepresentresearch,personalvalues

cat-egorized in Schwartz’s(1992, 1994, 2012) conceptualizationas

“opennesstochange”and “self-enhancement”valueswere

pre-dictedtobeindirectlyrelatedtowork-familyconflictviaperceived

organizationalclimate:

Hypothesis3.Therewillbeanegativerelationbetweenpersonal

egocentricvaluesandthefavorabilityofperceivedorganizational

climate:highlevelsofhedonism,stimulation,self-direction,power,

andachievementwillbeassociatedwithunfavorableperceptions

oforganizationalclimate.

Hypothesis4.Perceptionsoforganizationalclimatewillmediatethe

relationsbetweenthelevelofpersonalvaluesandWFC.

WorkEngagement

Asmentionedearlier,alongwithpredispositionsderivedfrom

personal values and perceived organizational climate, in the

presentresearchwewerealsointerestedinexploringthe

influ-ences of daily workplace experiences relevant to employees’

functioning,specificallythedegreeofinvestmentintheworkplace

(i.e.,“workengagement”),andwhethertheseinfluencesonWFC

aremediatedbyburnout(seeFigure1).

Workorjobengagementmaybedefinedas“apositive,fulfilling,

workrelatedstateofmindthatischaracterizedbyvigor,

dedica-tion,andabsorption”(Schaufeli&Bakker,2004,pp.295).Inother

words,workengagementreflectsthewillingnesstoinvesteffortin

workandtopersistinspiteofdifficulties(addressedas“vigor”);

asenseofsignificance, enthusiasm,inspiration,pride,and

chal-lenge(“dedication”);andconcentrationandengrossmentinwork

(“absorption”)(Schaufeli &Bakker, 2004).Employees

character-izedbyhighworkengagementaresaidtoidentifywiththeirwork,

andtoperceivetheirworkasmeaningful,inspirational,and

chal-lenging(Bakker&Demerouti,2007).Pastresearchhasshownthat

“engagedemployees”tendtoexperiencehighpersonalinitiative,

activeapproach,andmotivationtoacquireknowledge(Schaufeli

&Salanova, 2007; Sonnentag, 2003), and that this engagement

mayamplifyemployees’performanceandorganizationalsuccess

ingeneral(Bates,2004;Baumruk,2004;Demerouti&Cropanzano,

However, work engagement was also found to have

nega-tiveconsequences. Especially relevant tothepresent study are

its effects on WFB – high work engagement was found to be

associatedwithhigher levelsof work-familyconflictdue tothe

increasedresourcesthatengagedemployeesinvestintheirwork,

suchasorganizationalcitizenshipbehaviors(Halbesleben,Harvey,

&Bolino, 2009).Drawing onthesamerationale andtheoretical

background,inthepresentresearchwealsopredictedanegative

effectofworkengagementonWFC.Yet,wehypothesized

differ-entindirectinfluenceofworkengagement,namely,viaexcessive

workplaceburnout.Weshouldnotethattheremaybeother

pos-siblevariableswhichaffectemployees’highjobinvolvement,for

exampleworkaholism.Yet,workaholismhasadifferentconceptual

meaningasitisdefinedas“. . . thecompulsionorthe

uncontrol-lableneedtoworkincessantly”(Oates,1971,p.11),oranirresistible

innerdrivetowork(McMillan,O’Driscoll,&Burke,2003).Such

def-initionsaresaidtoexcludeconsideringworkaholismasapositive

state(e.g.,Schaufeli,Taris,&vanRhenen,2008;Scott,Moore,&

Miceli,1997).Moreover,workaholismmayinitiallyimplythatthe

balancebetweenworkandfamilydoesnotexistorisinterrupted

asthebalanceisskewedtowardswork.

Inthepresentresearch,wesoughttolookatallegedly“healthy”

workinvolvementphenomena(i.e.,workengagement)that

sim-ilarly to personal values may also have negative implications

forWFC.Thetheoreticalbackgroundforthepredictionof

nega-tiverelationsbetweenworkengagement,burnout,andWFCwas

theConservationofResources(COR)theory(Hobfoll,1988,1998,

2001). COR theory emphasizes people’s willingness to acquire

andprotectresources(psychological,social,andmaterial),while

acquired resourcesare invested to obtainadditional resources.

Thestrivingtoobtainandprotectresourcesissoimportantthat

psychologicalstressoccurswhenthosearelost,threatenedwith

loss,orifindividualscannotreplenishresourcesaftersignificant

investment.Employees characterizedbyhighworkengagement

aresupposedtobepreoccupiedwithreinvestingtheirresources

intheworkplace(knowledge,skills,energy,etc.).However,work

demandsthreatenemployees’resources,andcontinuedexposure

tosuchdemandsleadstoemotionalexhaustion(Hobfoll&Freedy,

1993),especiallyasresourcelossisdisproportionatelymoresalient

than resource gain (Hobfoll, 2001). Eventually,such a state of

affairslimitsemployees’competencetomeetfamilyrequirements,

andtherefore givesrisetoexperiences ofwork-family

interfer-ence(seeHalbeslebenetal.,2009).Accordingly,weexpectedthat

thoughworkengagementmayleadtopositiveorganizational

con-sequences,itcouldalsocontributetoworkfamilyconflict.

Hypothesis 5. There will be a positive relation between work

engagementandWFC:employeescharacterizedbyhighlevelsof

workengagementwillexpresshigherWFCrelativelytothose

char-acterizedbylowlevelsofworkengagement.

Burnout

Theexperiencesofpsychologicalstressandemotional

exhaus-tionfollowinghighandcontinuedworkengagement,consistent

withthedefinitionof“workburnout”.Workburnoutisdescribed

alongthreedimensions:emotionalexhaustion,experienced

dis-tance from others, and diminished personal accomplishment

(Maslach, 1982).Burnout was addressed as the “dark side” of

workengagement,leadingemployeestoinferiorjobperformance

andsacrificingdifferentaspectsofpersonallife(Maslach,2011).

Work burnout hasdifferent negative outcomes for employees,

suchasabsenteeism (Ahola et al.,2008), chronic work

disabil-ity(Ahola,Toppinen-Tanner,Huuhtanan,Koskinen,&Väänänen,

2009),turnover(Shimizu,Feng,&Nagata,2005),poorerjob

per-formance(Taris,2006), workingsafety(Nahrgang,Morgeson,&

Hofmann,2011), andeven depressivesymptomsand decreased

lifedissatisfaction(Hakanen&Schaufeli,2012).Inthecontextof

work-familybalance,we expectedthat burnoutwould increase

theperceivedinterferencebetweenworkandfamily,particularly

givenitscharacteristicofemotionalexhaustion(Johnson&Spector,

2007).FollowingCORtheory,emotionalexhaustionsignalsthatthe

employeeisdeprivedofhisorherresources,andthereforemay

experienceincreasedtensioninanattempttomeetbothworkand

familyrequirements.Accordingly,wepredictednegativerelations

betweenworkburnoutandWFC.Finally,wehypothesizedthatas

burnoutmayconstitutethenegativeconsequenceofhighwork

engagement,itshouldbeassessedinthepresentresearchmodelas

amediatoroftherelationsbetweenworkengagementand

work-familyconflict.Insum,ournexthypotheseswereasfollowing:

Hypothesis6.Therewillbeapositive relationbetweenburnout

andWFC:thehighertheexperiencedworkburnout,thehigherthe

reportsofWFCwillbe.

Hypothesis 7. There will be a positive relation between work

engagementandburnout:highworkengagementwillbe

associ-atedwithhigherreportsofworkburnout.

Hypothesis8.Workburnout willmediatetherelations between

workengagementandWFC.

ThePresentResearch

Inthepresentresearch,weaimedtoexaminetwopsychological

pathstoexperiencesofwork-familyconflict.First,weassessedthe

“Ibelieve”path,i.e.,thewaypersonalvaluespredictWFC,while

exploringwhethervaluesaffectemployees’perceptionsof

orga-nizationalclimateandsubsequentlyWFC(Study1).Pastresearch

hashighlightedtheneedtoconsiderthefactorofvaluesin

rela-tiontowork-familybalance(e.g.,Carlson&Kacmar,2000;Promislo

etal.,2010;Smelser,1998),yetthereisrelativelylittleresearch

ontheassociationbetweenpersonalvaluesandWFC.Specifically,

asfarasweknow,nopreviousresearchhasexaminedtheroleof

basichumanvaluesinpredictingpronenesstoexperience

work-familyconflictviatheirimplicationsonemployees’perceptionsof

theirworkplaceorganizationalclimate.Second,weexaminedthe

“Iinvest”path,i.e.,theinfluencesofemployees’workengagement

onWFCviaitsassociationswithworkburnout(Study2)1.Although

pastresearchhasfoundthatworkengagementmaybeassociated

withhighreportsofWFC(Halbeslebenetal.,2009),mostofthe

studiestendtofocusonthepositiveimplicationsofwork

engage-ment.Inthepresentresearchweintendedtofurtherexplorework

engagementassociationswithwork-familyconflict,whileinvoking

theConservationofResourcestheoryperspectiveastherationale

ofourpredictionthatworkburnoutwouldmediatetherelations

betweenthetwovariables.

Study1

Inthisstudy,weaimedtoexploretherelationsbetween

per-sonalvalues,perceivedorganizationalclimateandreportsofWFC.

1Thedataforthepresentstudieswerecollectedduringtheyears2013-2014in

alargecellularprovidercompany,twohigh-techcompanies,andacommunication

Method

Participants

Theparticipants,whovolunteered totakepartinthestudy,

were242employeesoftwocompanycenters(oneismore

cen-tralasitincludesthecompany’sheadquarters,theotherisabig

center)of a largecellularprovider (129 women and 104 men,

9 participants did not indicate their gender; mean age=35.50,

SD=1.07).Thecompanyprovidesservicesofwireless

communi-cations,owns and controls theelementsnecessary to sell, and

deliverservicestotheenduserincludingwirelessnetwork

infra-structure,billing,customercare,marketing,andrepair.Fifty-seven

percentoftheparticipantsweresingle,39%weremarried,and4%

weredivorced.Forty-twopercentoftheparticipantsstatedthat

theywereemployedatthecompany’sheadquarters,26%worked

inthesalesdepartment,and32%inthecustomerservice

depart-ment.Seventy-ninepercentofthemhadalowoccupationallevel,

17%wereemployedinintermediatemanagementpositions,and

4%indicatedhighmanagerialpositions.Asforlevelofeducation,

45%oftheemployeeshadaBAdegree,27%hadapost-secondary

education,17%hadasecondaryeducation,and11%indicatedan

MAdegree.

ProcedureandMeasures2

The participants signed up for a study examining, “issues

regardingworkplaces”.Anexperimenterexplainedthatthestudy

wouldinvolveansweringquestionnaires,andthattheparticipants

wereexpectedtogivehonestanswersrepresentingtheiractual

feelingsandthoughts.Alltheparticipantstookpartinthestudy

voluntarily,theywereassuredofcompleteanonymity(the

par-ticipants didnot provide any personal information), and were

giventhepossibility towithdraw fromfillingthequestionnaire

atanytime. The questionnairestookapproximately15minutes

tocomplete.Aftercompletingthemeasures,allparticipantswere

debriefed. As we intended to assess the independent variables

indicativeofparticipants’personalvaluesandperceptionsof

orga-nizationalclimatebeforeaddressingthedependentvariable(i.e.,

experiencesofwork-familyconflict),wefirstmeasured

employ-ees’valuesandperceptionsoforganizationalclimate,andthenthe

WFCmeasurewasintroduced.

Personalvalues. To assess theirpersonal values, the

partici-pantswereaskedtocompletea57-itemquestionnairerepresenting

10motivationallydistinctvalueconstructsonaLikertscale

ran-gingfrom1(opposedtomyvalues)to9(ofsupremeimportance) (Schwartz, 1992): self-direction, 5 items, for example: “Think

upnewideasand becreative”(Cronbach’s alpha=.77, M=7.17,

SD=1.13);stimulation,5items,forexample:“Lookforadventures

andliketotakerisks”(Cronbach’salpha=.78,M=6.78,SD=1.23);

hedonism, 6 items, for example: “Seek every chance I can to

havefun”(Cronbach’salpha=.80,M=7.29,SD=1.16);conformity,

4items,forexample:“Itisimportanttomealwaystobehave

prop-erly”(Cronbach’salpha=.73,M=6.98,SD=1.36);security,7items,

forexample: “Itis importanttometolivein secure

surround-ings”(Cronbach’salpha=.70,M=6.57,SD=1.29);universalism,8

items,forexample:“Itisimportanttometolistentopeoplewho

2Asthepresenttwostudiesexploredpersonalbeliefsindicatedbyindividual

val-ues,perceptionsoftheworkplace,andexperiencesofwork-familyconflict,themost

suitablewaytocollectthedatawasemployees’self-reports.Pastworkaddressed

self-reportsasclearlyappropriateforaccessingemployees’psychologicalvariables

sinceindividualsaretheoneswhoareawareoftheirperceptions.Inaddition,we

usedwidelycitedandthoroughlyresearchedmeasureswhiledeliberatelyassessing

theirreliabilityalsointhepresentstudies(alsoseeConwayandLance,2010for

discussionontheself-reportmethod).

aredifferentfromme”(Cronbach’salpha=.80,M=7.16,SD=1.19);

benevolence,8items,forexample:“Itisimportanttometobe

loyaltomyfriends” (Cronbach’salpha=.85,M=7.15,SD=1.16);

tradition, 5 items, for example: “Tradition is important tome”

(Cronbach’s alpha=.73, M=6.98, SD=1.36); power,4 items, for

example:“Itisimportanttometobeinchargeandtellotherswhat

todo”(Cronbach’s alpha=.67, M=6.51, SD=1.31); and

achieve-ment,5items,forexample: “Beingverysuccessfulisimportant

tome”(Cronbach’salpha=.85,M=7.53,SD=1.16).

Perceptionsoforganizationalclimate.WefollowedVardi’s(2001)

implementationofa38-itemquestionnairebasedonthe

Organi-zationalClimate Questionnaire(OCQ) (Litwin&Stringer,1968),

assessing nine dimensions of organizational climate. Responses

weregivenonaLikertscalerangingfrom1(stronglydisagree)to6

(stronglyagree):structure,5items,forexample:“Thepoliciesand

organizationalstructureoftheorganizationareclearlyexplained”

(Cronbach’salpha=.76,M=4.36,SD=0.80);responsibility,4items,

for example: “Our organizational philosophy emphasizes that

peopleshouldsolvetheirproblemsby themselves”(Cronbach’s

alpha=.68,M=2.76,SD=1.01);reward,4items,forexample:“We

haveapromotionsystemherethathelpsthebestmantoriseto

thetop”(Cronbach’salpha=.74,M=3.709,SD=0.99);risk,7items,

forexample: “Thephilosophyof ourmanagementisthat inthe

longrunwegetaheadfastestbyplayingitslow,safe,andsure”

(Cronbach’salpha=.53,M=3.99,SD=0.73);warmth,3items,for

example: “Afriendlyatmosphere prevails among thepeoplein

thisorganization”(Cronbach’salpha=.67,M=3.96,SD=1.06);

sup-port,3items,forexample:“WhenIamonadifficultassignment

Icanusuallycountongettingassistancefrommyboss and

co-workers”(Cronbach’salpha=.70,M=2.78,SD=1.18);standards,4

items,forexample:“Inthisorganizationwesetveryhighstandards

forperformance”(Cronbach’salpha=.58,M=4.38,SD=0.77);

con-flict,4items,forexample:“Decisionsinmanagementmeetingsare

madequicklyandwithoutanydifficulty”(Cronbach’salpha=.38,

M=3.82, SD=0.80); and identity, 4 items,for example: “People

areproudtobelongtothisorganization”(Cronbach’salpha=.59,

M=3.25,SD=0.65).

Becauseofrelativelylowreliabilitycoefficientsoffour

dimen-sions(risk,standards,conflict,andidentity),theitemsincludedin

thesedimensionswereanalyzedseparately.Inaddition,according

tothehypotheses,anoverallmeasureofperceivedorganizational

climatewascomputed(Cronbach’salpha=.74,M=2.98,SD=0.56).

Work-familyconflict.Work-familyconflictwasmeasuredwith

a scaledeveloped by Netemeyer,Boles, and McMurrian(1996),

consistingof10itemstowhichparticipantsrespondedona

Lik-ertscalerangingfrom1(stronglydisagree)to6(stronglyagree).

Fiveitemsassessedwork-familyinterference(e.g.,“Thedemands

ofmyworkinterferewithmyhomeandfamilylife”)andfiveitems

assessedfamily-workinterference(e.g.,“Thedemandsofmy

fam-ily or spouse/partnerinterfere withwork-related activities”).A

recentmeta-analysishasindicatedthatWIFandFIWare

consis-tentlyrelatedtothesametypesofoutcomeswhileassessingboth

directionsoftheconflict(Amstadetal.,2011).Accordingly,aswe

aimedtoassesstheexperienceofaconflictinasenseofimbalance

betweenworkandfamilydemands,anoverallmeasureofWFCwas

computed(Cronbach’salpha=.89,M=2.80,SD=0.96).

Results3

Inordertoaccessthepredictedmediatedrelationshipsbetween

thevariables,wefollowedBaronandKenny,(1986)procedurefor

3Employees’genderwasassessedintheinitialanalysis.Neithermaineffectsnor

interactionswithgenderwerefound.Therefore,theresultsarepresentedforboth

Hedonism

WFC Perceived

Organizational Climate

.18**

.–17**

.–43*** Achievement

.18**

.–16*

.–42***

Self-direction

Power

.13**

.–43*** .–21**

.11

.–36*** .–40***

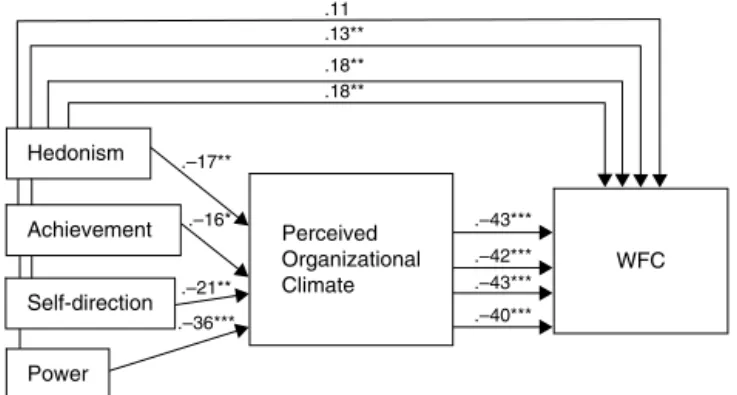

Figure2. Study1:TheRelationsbetweenValues,PerceivedOrganizationalClimate,

andWFC.

Note.Thenumbersabovethearrowsarestandardizedbetacoefficients().

*p<.05,**p<.01,***p<.001.

examiningmediation4.TheanalyseslendsupporttoHypotheses

1-4,asfollows(seeFigure2):

(1)WFCregressedonhedonism(theindependentvariable)andthe

overallmeasureofperceivedorganizationalclimate(the

sup-posedmediator):hedonismappearedasasignificantpredictor

ofwork-familyconflict,=.18,t(240)=2.79,p<.01;hedonism

significantly predictedthe perceivedorganizational climate,

=-.17, t(240)=-2.77, p<.01; and perceived organizational

climatesignificantlypredictedWFCwhilecontrollingfor

hedo-nism,=-.43,t(239)=-7.66,R2=.22,p<.001.TheSobeltest(see

Soper,2014)indicatedthatperceivedorganizationalclimate

significantlymediatedbetweenhedonismandWFC(z=2.59,

p<.01).Sincetheomissionofperceivedorganizationalclimate

fromthemodelreduced butdidnoteliminatetheinfluence

ofhedonismonWFC,theresultsrepresentapartialmediation

effect.

(2)WFC regressed on achievement and the overall measure

of perceived organizational climate: achievement appeared

as a significant predictor of work-family conflict, =.18,

t(240)=2.91, p<.01;achievementsignificantlypredictedthe

perceivedorganizationalclimate,=-.16,t(240)=-2.47,p<.05;

and perceived organizational climatesignificantly predicted

WFCwhilecontrollingforachievement,=-.42,t(239)=-7.60,

R2=.22,p<.001.TheSobeltestindicatedthatperceived

organi-zationalclimatesignificantlymediatedbetweenachievement

andWFC(z=2.35,p<.05).Theomissionofthemediatorfrom

themodelpointedtopartialmediation.

(3)WFCregressed onself-directionandthe overallmeasure of

perceivedorganizationalclimate:self-directionwasa

signif-icant predictorof work-family conflict, =.13, t(240)=1.87,

p<.05;self-directionalsosignificantlypredictedtheperceived

organizational climate, =-.21, t(240)=-3.28, p<.01; and

perceivedorganizationalclimatesignificantlypredictedWFC

while controlling for self-direction, =-.43, t(239)=-7.50,

R2=.20,p<.001.TheSobeltestindicatedthatperceived

organi-zationalclimatesignificantlymediatedbetweenself-direction

andWFC(z=2.90,p<.05).Theomissionofperceived

organiza-tionalclimatefromthemodelindicatedpartialmediation.

(4)WFC regressed on power and the overall measure of

perceivedorganizational climate:theresultsindicatedclose

to significance effect of power on work-family conflict,

=.11, t(240)=1.80, p=.07; power significantly predicted

4 ConcurrentwithHypothesis1,valuesofsecurity,benevolence,conformity,

uni-versalism,andtraditionwerenotsignificantlyassociatedwithWFC,andtherefore

werenotincludedinmediationanalyses.

the perceived organizational climate, =-.36, t(240)=-6.01,

p<.001;andperceivedorganizationalclimatesignificantly

pre-dictedWFCwhilecontrollingforpower,=-.40,t(239)=-6.47,

R2=.16,p<.001.TheSobeltestindicatedthatperceived

orga-nizationalclimatesignificantlymediatedbetweenpowerand

WFC(z=4.36, p<.001).Theomissionof perceived

organiza-tionalclimatefromthemodelindicatedfullmediation,asthe

effectofpoweronWFCwaseliminated.

Additionalanalyseswereperformedinordertoaccess

medi-ationwithspecificdimensionsandspecificitems(seeMethod

section)of perceived organizational climate. WFCregressed

on personal values, dimensions of structure, responsibility,

reward,warmth,support,anditemsrepresentingthe

dimen-sions of conflict, standards, risk, and identity. Significant

relationsappearedwithvaluesofself-directionand

achieve-ment,andthefollowing:perceivedorganizationaldimension

of“structure”,organizational“standard”item(“Thereismuch

personal criticism in this organization”), and organizational

“identity”item(“Ifeellittleloyaltytothisorganization”).

Astheregressioncoefficientsbetweenthementioned

per-sonalvaluesandWFChavealreadybeenpresented,weturn

toa shortreportofthecoefficientsbetweentheIVsandthe

mediators, and between the mediators and the dependent

variable:

(5)WFCregressiononself-directionandtheitemofperceived

crit-icism attheworkplace: self-directionsignificantlypredicted

perceivedcriticism,=.20,t(239)=3.21,p<.05;andperceived

criticismsignificantlypredictedWFCwhilecontrollingfor

self-direction, =-.23, t(238)=-3.93,R2=.07, p<.001. The Sobel

testindicatedthatperceivedcriticismsignificantlymediated

betweenself-directionandWFC(z=2.30,p<.05).Theomission

ofthemediatorfromthemodelindicatedpartialmediation.

(6)WFCregression onself-directionand theloyalty item:

self-directionsignificantlypredictedloyalty,=.23,t(239)=3.64,

p<.001;andloyaltysignificantlypredictedWFCwhile

control-lingforself-direction,=-.31,t(238)=-4.96,R2=.11,p<.001.

The Sobel test indicated that loyalty significantly mediated

betweenself-directionandWFC(z=2.96,p<.01).Theomission

ofloyaltyfromthemodelindicatedfullmediation,astheeffect

ofself-directiononWFCwaseliminated.

(7)WFCregressiononachievementandtheloyaltyitem:

achieve-ment significantly predicted loyalty, =.22, t(239)=3.56,

p<.001;andloyaltysignificantlypredictedWFCwhile

control-lingforachievement,=-.30,t(238)=-4.75,R2=.12,p<.001.

The Sobel test indicated that loyalty significantly mediated

betweenachievementandWFC(z=2.92,p<.01).Theomission

ofloyaltyfromthemodelindicatedfullmediation,astheeffect

ofachievementonWFCwaseliminated(Table1).

Study2

Wereferredtotherelationshipofpersonalvaluesandperceived

organizationalclimateassessedinStudy1asthe“Ibelieve”ofWFC,

i.e.,psychologicalpredispositions and perceptions ofworkplace

environmentthatpredictemployees’experiencesofwork-family

conflict.Afterassessingtheseinfluences,Study2aimedtoexplore

the“Iinvest”ofWFC,whichisthepredictivepotentialofemployees’

levelsofworkengagementandburnout.

Method

Participants

The participants, who volunteered to take part in the

Table 1 Study 1: Inter-correlational Matrix

Self direc- tion Stimula- tion Hedo- nism Confor- mity Secu- rity Univer- salism Bene- volence Tradi- tion Power Achie- vement Climate- structure Climate- responsi- bility Climate reward Climate- risk Climate- warmth Climate- support Climate- standards Climate- conflict Climate- identity Overall organiza- tional climate

WFC Self direction Stimulation .782** Hedonism .711** .706** Conformity .658** .598** .616** Security .652** .710** .634** .705** Universalism .704** .645** .674** .751** .745** Benevolence .679** .642** .695** .752** .713** .789** Tadition .658** .598** .616** 1.000** .705** .751** .752** Power .572** .544** .531** .457** .578** .504** .642** .457** Achievement .767** .643** .725** .684** .625** .746** .800** .684** .538** Climate structure − .175** − .080 − .114 − .211** − .108 − .151* − .234** − .211** − .171** − .162* Climate responsibility .126 − .018 .137* .078 − .119 .126 .095 .078 − .061 .121 − .131* Climate reward − .197** − .207** − .112 − .145* − .168** − .147* − .190** − .145* − .179** − .097 .153* − .043 Climate risk − .288** − .214** − .198** − .248** − .181** − .220** − .311** − .248** − .313** − .245** .251** − .082 .599** Climate warmth − .005 .016 − .032 .071 − .013 .074 − .002 .071 − .082 − .035 − .082 .285** − .229** − .041 Climate support .057 − .081 .012 .057 − .163* .051 .054 .057 − .129* .050 − .217** .498** − .190** − .033 .318** Climate standards − .385** − .310** − .234** − .271** − .215** − .253** − .331** − .271** − .300** − .343** .251** − .098 .407** .573** .036 − .154* Climate conflict − .316** − .361** − .257** − .298** − .339** − .339** − .379** − .298** − .343** − .256** .116 .032 .454** .508** − .049 − .031 .486** Climate identity .248** .092 .152* .216** .025 .251** .268** .216** .143* .257** − .298** .463** − .376** − .311** .375** .512** − .359** − .204** Overall Organizational climate − .219** − .304** − .153* − .161* − .305** − .149* − .238** − .161* − .355** − .155* .050 .510** .389** .526** .435** .498** .464** .543** .265** WFC − .166** − .057 − .238** − .180** − .015 − .175** − .163* − .180** .094 − .210** .018 − .430** .012 − .053 − .221** − .428** .044 − .010 − .313** − .307** * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

one communications company (126 women, 114 men, mean

age=34.68, SD=7.34). The high-tech companies specialize in

the development of cutting-edge technologies and incorporate

advancedcomputerelectronics.Thecommunicationcompany

pro-videscustomerswithdiversetechnology-drivencommunication

solutions,includinglongdistancecallsforfixedandmobilelines

and Internet infrastructure. Twenty-five percentof the

partici-pantsweresingle,and75%weremarried.Seventy-eightpercent

oftheemployeeswereemployedatnon-managerialpositionsand

22%indicatedmanagerialposition.Asforlevelofeducation,56%

oftheemployeeshadaBAdegree,22%indicatedanMAdegree,

19% had a post-secondary education, and 3% had a secondary

education.

ProcedureandMeasures

The participants signed up for a study examining, “issues

regardingworkplaces”.Anexperimenterexplainedthatthestudy

wouldinvolveansweringquestionnaires,andthattheparticipants

wereexpectedtogivehonestanswersrepresentingtheiractual

feelingsandthoughts.Alltheparticipantstookpartinthestudy

voluntarily,theywereassuredofcompleteanonymity(the

par-ticipants did not provide any personal information), and were

given thepossibility towithdrawfromfillingthequestionnaire

at anytime.The questionnairestookapproximately10minutes

tocomplete.Aftercompletingthemeasures,allparticipantswere

debriefed.We firstmeasuredemployees’workengagementand

burnout,andthentheWFCmeasurewasintroduced.

Workengagement.Toassessworkengagement,theparticipants

wereaskedtocompletea9-itemquestionnaire(theUtrechtWork

EngagementScale-UWES;Schaufeli,Bakker,&Salanova,2006).

ResponsesweregivenonaLikertscalerangingfrom1(strongly

disagree)to 6(stronglyagree)reflecting three dimensions:

ded-ication,3 items,forexample: “I amenthusiasticaboutmy job”

(Cronbach’s alpha=.77, M=4.34, SD=1.45); vigor, 3 items, for

example:“WhenIgetupinthemorning,Ifeellikegoingtowork”

(Cronbach’s alpha=.81,M=4.72,SD=1.05); absorption,3 items,

forexample:“Iamimmersedinmyjob”(Cronbach’salpha=.89,

M=4.78,SD=0.96).Asitisrecommendedtousetheoverallscale

as a measure of workengagement (Schaufeli et al., 2006) and

accordingtothepresenthypotheses,theoverallUWESmeasure

wasused inthepresent study(Cronbach’s alpha=.71, M=4.68,

SD=0.94).

Burnout.Employees’experiencesofburnoutwereassessedbya

16-itemquestionnaire(MaslachBurnoutInventory-GeneralScale,

MBI-GS;Schaufeli,Leiter,Maslach,&Jackson,1996),thatthe

par-ticipants answeredona 1 (never)to 6 (daily) Likertscale. The

MBI-GSmeasuresthreedimensionsofburnout:5itemsassessing

exhaustion, e.g., “I feel used up at the end of the workday”

(Cronbach’salpha=.85,M=4.51,SD=0.36);5itemsassessing

cyn-icism, e.g., “I have become less enthusiastic about my work”

(Cronbach’salpha=.75,M=4.68,SD=0.45);and6itemsassessing

professionalefficacy,e.g.,“Inmyopinion,Iamgoodatmyjob”,

areversecodeditem(Cronbach’salpha=.67,M=4.64,SD=0.29).

Burnoutisreflectedinhigherscoresonexhaustionandcynicism,

and lower scores on efficacy.According to the hypotheses, an

overallmeasurewascomputed(Cronbach’salpha=.88,M=4.62,

SD=0.65).

Work-familyconflict.Work-familyconflictwasmeasuredwith

the same scale as in Study 1 (Netemeyer et al., 1996), 10

items to which participants responded on a Likert scale

ran-ging from1 (stronglydisagree) to6 (stronglyagree).Five items

assessedwork-familyinterferenceandfiveitemsassessed

family-workinterference.Anoverallmeasurewascomputed(Cronbach’s

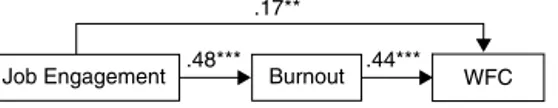

Job Engagement .48*** Burnout .44*** WFC .17**

Figure3.Study2:TheRelationsbetweenjJobeEngagement,Burnout,andWFC

Note.Thenumbersabovethearrowsarestandardizedbetacoefficients().

**p<.01,***p<.001.

Table2

Study2:Inter-correlationalMatrix.

Burnout Job engagement

Burnout

Jobengagement .481*

WFC .462** .299**

Results5

In order toaccess the indirectinfluence of job engagement

onWFCviaexperiencedburnout,wefollowedBaronandKenny,

(1986)stepsforassessingmediation.Theresultslendsupportto

Hypotheses5-8(seeFigure3).

(1)WFC regression on job engagement (the independent

vari-able)andburnout(thesupposedmediator)indicatedthatjob

engagementwasasignificantpredictorofwork-familyconflict,

=.17,t(238)=2.09,p<.01,sothathighjobengagementwas

associatedwithhighWFC.

(2)Job engagement significantly predicted burnout, =.48,

t(238)=8.38,p<.001.

(3)BurnoutsignificantlypredictedWFCwhilecontrollingforjob

engagement,=.44,t(237)=2.50,R2=.04,p<.001.TheSobel

test revealed that burnout significantly mediated between

jobengagementandWFC(z=5.48,p<.001).Theomissionof

burnoutfromthemodelindicatedfullmediation,astheeffect

ofjobengagementonWFCwaseliminated.(Table2).

Discussion

Thepresentresearchaimedtounderstandwork-familybalance

antecedentsbyexaminingtheindirectrelationsbetween

employ-ees’valuesandworkengagement,andWFC.

Study1exploredtherelationsbetweenemployees’personal

values and perceived organizational climate, and their

expe-riences of work-family conflict. We predicted that employees

characterizedby highlevelsof“openness tochange”and

“self-enhancement” values would express higher WFC than those

characterized by low levels of these values, while values of

conformity, tradition, security, universalism, and benevolence

would be less related to WFC. This prediction was generally

supported.Employees high in hedonism, self-direction, power,

andachievementexpressedhighWFC.Contrarytothepredicted

influenceof stimulation(one of the “opennessto change”

val-ues), it did not predict WFC. The results also lend support to

the indirect effect of personal values, as perceived

organiza-tional climate was found to mediate between personal values

and WFC. High levels of hedonism, self-direction, power, and

achievementwereassociatedwithlowlevelsofperceived

over-allorganizationalclimate,i.e.,relativelyunfavorableperceptions,

andconsequentlyhighWFC.Inaddition,perceivedcriticismatthe

5 Employees’genderwasassessedintheinitialanalysis.Neithermaineffectsnor

interactionswithgenderwerefound.Thereforetheresultsarepresentedforboth

femaleandmaleemployees.

workplaceandemployee’sorganizationalloyaltyitemsappeared

asmediatorsbetweenvaluesofself-directionand achievement,

andWFC.Self-directionwaspositivelyassociatedwithperceived

criticism atthe workplaceand eventually highWFC.However,

self-directionandachievementvalueswerealsopositivelyrelated

to organizational loyalty, whereas loyalty negatively predicted

WFC.

Overall, the results point to associations between personal

valuesand perceivedorganizationalclimate,and experiencesof

work-familyconflict. First, it seemsthat highegocentricvalues

relate to unfavorable climateperceptions. This may be due to

increasedcriticismtowardtheworkenvironmentvis-à-vis

per-sonalaspirations.Inotherwords,whenhighpersonalaspirations

embeddedinhedonism,self-direction,power,andachievement

valuesarenotmet,theemployeemayperceivetheexisting

orga-nizationalclimatemorenegativelycomparedtoonecharacterized

bylowerlevelsofthesevalues.Study1didnotindicatesimilar

resultswiththe“stimulation”value.Thismaybeduetoitsspecific

psychologicalmeaningandinfluence,since,althoughegocentric,

thisvaluedealswithexcitementandchallenge,whileother

ego-centricvaluesemphasizeprestige,control,independence,success,

andpleasure(Schwartz,1992,1994).Therefore,thelattervalues

haveagreaterpotentialtoclashwithorganizationalconstraints

andnormsthan“stimulation”.

Second, the resultsindicated that an unfavorably perceived

organizationalclimateclearlyrelatestohigherreportsof

work-familyconflict.Thisinfluencemaybeduetotheoverallperception

thatone’sorganizationalenvironmentislesssupportivethan

pre-ferred, and therefore the conflict, namely, imbalance between

workand family demands, is amplified. Interestingly,values of

self-directionandachievementwerepositivelyrelatedto

organi-zationalloyalty.Thisfindingseemstocontradictthehypothesized

linkbetweenegocentricvaluesandunfavorableorganizational

per-ceptions.Itmaybethatemployees’perceptionsoforganizational

loyaltyareindependentofotherclimatedimensionsinthe

con-textofvalues’implications;however,moreresearchisrequiredto

clarifytheserelations.Yet,theconsequentialassociationbetween

loyaltyandWFCwasinlinewithourpredictions,asthenegative

relationbetweenthesevariablesindicatesthatlowerloyalty(i.e.,

“unfavorable”perceptions)isassociatedwithhigherWFC.

Study2exploredthesecondpartoftheproposedmodel(see

Figure1)byexaminingtherelations betweenemployees’work

engagementandburnout, andtheirexperiences ofwork-family

conflict. Wehypothesizedand foundthatemployeeswhowere

highlyengagedintheirworkexpressedhigherWFC.Moreover,the

resultssupportedtheindirectinfluenceofworkengagementvia

workburnout–workengagementwaspositivelyassociatedwith

burnoutthatinturnpositivelypredictedWFC.Overall,theresults

ofStudy2point tothedetrimentaleffectofseeminglypositive

phenomena(i.e.,employees’effort).Highlevelsofworkinvestment

mayleadtoburnout,andthisstateofemotional(andinsomecases

physical)exhaustionmayamplifyemployees’capabilitytobalance

workpressuresandfamilydemands.

Thepresentresearchhasseveralimplications,boththeoretical

andpractical.First,fromatheoreticalpointofview,thetwostudies

indicatethattounderstandwork-familybalancebetter,weshould

addressimportantindividualdifferencesinpsychological

predis-positions.Suchpredispositionsarereflectedinvalues,whichform

personalstandardsandaffectattitudesandbehavior.Pastresearch

hasindicatedthatvaluesmayexplainwhycertainindividualsare

morepronetoexperienceWFCthanothersare(Carlson&Kacmar,

2000;Smelser,1998).Thepresentworkfollowedthisreasoningby

assessingtheeffectofpersonalvaluesviatheirassociationswith

perceivedorganizationalclimate.Whilerecentresearchhasfound

relationsbetweenmaterialisticvaluesandhighwork-family

ofbasicpersonalvalues,particularlyegocentricvalues

conceptu-alizedbySchwartzaspartof“self-enhancement”and“openness

tochange”orientations.Highlevelsofthesevalues(i.e.,hedonism,

achievement,self-direction,andpower)maybeassociated with

positiveorganizationaloutcomes.However,asthepresentresearch

reveals,theymayalsoleadtorelativelynegativeperceptionsof

organizationalclimate.Wesuggestedthatthelattermaybedueto

increasedcriticismtowardtheworkenvironmentthatsuchvalues,

indicativeofwillingnesstoexcelandcontrol,mayencourage.

How-ever,futureresearchisneededinordertoclarifythepsychological

mechanismbehindthisassociation.Eventually,andinlinewith

pastresearchpropositions(e.g.,Carlson&Perrewé,1999;Kossek,

Baltesetal.,2011;Majoretal.,2008;VanDerPompe&Heus,1993),

perceivedorganizationalclimateprojectsonWFC,sothat

nega-tiveclimateperceptionspredicthighexperiencesofwork-family

interference.

Other important individual differences are reflected in the

degreesofworkengagementandburnout.Wefollowedthe

the-oreticalframeworkofCORtheorytoexplaintheinfluencesofthese

variablesonWFC.Recentresearchhasalready foundhighWFC

amongemployeescharacterizedbyso-called“obsessivepassion”

towardswork(Caudroitetal.,2011).Thepresentresearchtakesa

furtherstepinclarifyingthenegativesideofworkengagementby

showingthatinitiallypositiveorganizationalbehaviormayincur

personal costsreflected in increasedburnout and subsequently

work-familyconflict.Apossibleexplanationofburnoutinfluences

liesinemployees’depletedresources(Taris,Schreurs,&Van

Iersel-VanSilfhout,2001;Wright&Cropanzano,1998).Thedepletionof

resourcesmakesitdifficulttomeetbothworkandfamilydemands,

makingtheemployeevulnerabletoWFCexperiences.

Onthepracticallevel,thepresentfindingshaveseveral

impli-cationsfororganizationalpractitionersandleaders.(1)Although

organizationsvaluetraitsofself-directionandachievement,the

present findings indicate that these traits may also relate to

highexperiences ofwork-familyconflict.Therefore, itis

impor-tant to raise leaders’ awareness and sensitivity to expressions

ofwork-familybalance,especially amongambitious employees.

(2) Perceived organizational climate, perceived criticismat the

workplace,andemployee’sorganizationalloyaltywerefoundto

mediatebetweenpersonalvaluesandWFC.Accordingly,

organiza-tionsshouldbeencouragedtotakestepstostrengthenpositive

impressionsof theworkplaceamong highlyambitious

employ-ees. (3) Although work engagement is another highly valued

employee’scharacteristic,workengagementpositivelyassociates

withburnoutthat inturnpredicts higherexperiences of

work-familyconflict.Organizationsshouldbeawareofthedetrimental

effectofemployees’effortsthatmayeventuallyamplifytheir

inca-pabilitytobalancebetweenworkpressuresandfamilydemands.

LimitationsandFutureDirections

Therearesomelimitationstothepresentresearch.Oneofthem

arethemeanlevelsofworkengagementandburnoutinStudy2

thatwererelativelyhigh(4.68and4.62ona1-6scale).Thismaybe

duetotheorganizationalcontextofthisstudy–theparticipants

weremainly employeesof high-tech companies.The high-tech

sectorisconsideredtobeverydemanding(Snir,Harpaz,&

Ben-Baruch,2009),andhigh-techemployeeswerefoundtoextendtheir

workhours(Sharone,2004).Therefore,itisreasonabletoexpect

reports of highworkengagement and burnout. We do assume

thatthepresentfindingsarenotuniquetoworkplaces

character-izedbyheavyinvestmentofresources.However,futureresearch

shouldaddresstheorganizationalcontextasanadditionalfactor,

byexaminingwhetheritmaymoderatetherelationsbetweenwork

engagement,burnout,andWFC.

Anothermoregenerallimitationofthepresentresearchisthe

correlativenatureofthetwostudies.Weimplementedregression

analysestoexaminetheproposedhypotheses,specificallyinorder

toaccessmediation.Thisapproachenabledustoexaminethe

indi-rectinfluencesofpersonalvaluesandworkengagement.Yet,itis

importanttorecallthatthecorrelativenatureofthepresentstudies

doesnotallowforcausalinferences.

Insum,thefindingsofthetwostudiesshowthatwork-family

balance is,indeed, closely related topersonal values and work

engagement,and thattheseeffectsareaccountedbytheir

asso-ciationswithperceivedorganizationalclimateandworkburnout.

Futureresearchshouldclarifythepsychologicalprocessbywhich

valuesofhedonism,achievement,self-direction,andpowerimpact

perceivedorganizationalclimate,andwhystimulation,although

relatedalongwithhedonismandself-directiontothe“opennessto

change”values,doesnothavesimilarinfluence.Finally,the

organi-zationalcontext(Tziner&Sharoni,2014)isanadditionalvariable

thatcanbeexaminedinfutureresearchasapossiblemoderatorof

relationsbetweenworkengagement,burnout,andWFC.

ConflictofInterest

Theauthorsofthisarticledeclarenoconflictofinterest.

References

Ahola,K.,Honkonen,T.,Virtanen,M.,Koskinen,S.,Kivimäki,M.,&Lönnqvist,J.

(2008).Occupationalburnoutandmedicallycertifiedabsence:A

population-based study of Finnish employees. Journalof Psychosomatic Research, 64, 185–193.

Ahola,K.,Toppinen-Tanner,S.,Huuhtanan,P.,Koskinen,A.,&Väänänen,A.(2009).

Occupationalburnoutandchronicworkdisability:Aneight-yearcohortstudy onpensioningamongFinnishforestindustryworkers.JournalofAffective Disor-ders,115,150–159.

Allen,T.D.,Herst,D.E.,Bruck,C.S.,&Sutton,M.(2000).Consequencesassociated

withwork-to-familyconflict:Areviewandagendaforfutureresearch.Journal ofOccupationalHealthPsychology,5,278–308.

Allen,T.D.,Johnson,R.C.,Saboe,K.N.,Cho,E.,Dumani,S.,&Evans,S.(2012).

Disposi-tionalvariablesandwork–familyconflict:Ameta-analysis.JournalofVocational Behavior,80,17–26.

Amstad,F.T.,Meier,L.L.,Fasel,U.,Elfering,A.,&Semmer,N.K.(2011).A

meta-analysisofwork–familyconflictandvariousoutcomeswithaspecialemphasis oncross-domain versusmatching-domainrelations.JournalofOccupational HealthPsychology,16,151–169.

Armstrong,M.(2003).Ahandbookofhumanresourcemanagementpractice.London:

KoganPageLimited.

Arthaud-Day,M.L.,Rode,J.C.,&Turnley,W.H.(2012).Directandcontextualeffects

ofindividualvaluesonorganizationalcitizenshipbehaviorinteam.Journalof AppliedPsychology,97,792–807.

Bacharach,S.B.,Bamberger,P.,&Conley,S.(1991).Work-homeconflictamong

nursesandengineers:Mediatingtheimpactofrolestressonburnoutand sat-isfactionatwork.JournalofOrganizationalBehavior,12,39–53.

Bakker,A.B.,&Demerouti,E.(2007).TheJobDemands-ResourcesModel:Stateof

theArt.JournalofManagerialPsychology,22,309–328.

Barnett,R.C.,Raudenbush,S.W.,Brennan,R.T.,Pleck,J.H.,&Marshall,N.L.(1995).

Changeinjobandmaritalexperiencesandchangeinpsychologicaldistress: Alongitudinalstudyofdual-earnercouples.JournalofPersonalityandSocial Psychology,69,839–850.

Baron,R.M.,&Kenny,D.A.(1986).Themoderator-mediatorvariabledistinction

insocialpsychologicalresearch:Conceptual,strategic,andstatistical consider-ations.JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,51,1173–1182.

Bates,S.(2004).Gettingengaged.HRMagazine,49,44–51.

Baumruk,R.(2004).Themissinglink:Theroleofemployeeengagementinbusiness

success.WorkSpan,47(11),48–52.

Butts,M.M.,Caspar,W.J.,&Yang,T.S.(2013).Howimportantarework-family

supportpolicies?Ameta-analyticinvestigationoftheireffectsonemployee outcomes.JournalofAppliedPsychology,98,1–25.

Carlson,D.S.,&Kacmar,K.M.(2000).Work–familyconflictintheorganization:Do

liferolevaluesmakeadifference?JournalofManagement,26,1031–1054.

Carlson,D.S.,&Perrewé,P.L.(1999).Theroleofsocialsupportinthestressor-strain

relationship:Anexaminationofwork-familyconflict.JournalofManagement, 25,513–540.

Caudroit,J.,Boiche,J.,Stephan,Y.,LeScanff,C.,&Trouilloud,D.(2011).Predictors

ofwork/familyinterferenceandleisure-timephysicalactivityamongteachers: Theroleofpassiontowardswork.EuropeanJournalofWorkandOrganizational Psychology,20,326–344.

Cohen,A.(2011).Valuesandpsychologicalcontractsintheirrelationshipto

Cohen,A.(2012).Therelationshipbetweenindividualvaluesandpsychological contracts.JournalofManagerialPsychology,27,283–301.

Conway,J.M.,&Lance,C.E.(2010).Whatreviewersshouldexpectfromauthors

regardingcommonmethodbiasinorganizationalresearch.JournalofBusiness andPsychology,25,325–334.

Demerouti,E.,&Cropanzano,R.(2010).Fromthoughttoaction:Employeework

engagementandjobperformance.InA.B.Bakker,&M.P.Leiter(Eds.),Work engagement:Ahandbookofessentialtheoryandresearch..NewYork:Psychology Press.

Fein,E.C.,Vasiliu,C.,&Tziner,A.(2011).Individualvaluesandpreferredleadership

behaviors:AStudyofRomanianmanagers.JournalofAppliedSocialPsychology, 41,515–535.

Frone,M.R.(2000).Work–familyconflictandemployeepsychiatricdisorders:The

nationalco-morbiditysurvey.JournalofAppliedPsychology,85,888–895.

Hakanen,J.J.,&Schaufeli,W.B.(2012).Doburnoutandworkengagementpredict

depressivesymptomsandlifesatisfaction?Athree-waveseven-year prospec-tivestudy.JournalofAffectiveDisorders,141,415–424.

Halbesleben,J.R.,Harvey,J.,&Bolino,M.C.(2009).Tooengaged?Aconservationof

resourcesviewoftherelationshipbetweenworkengagementandwork inter-ferencewithfamily.JournalofAppliedPsychology,94,1452–1465.

Hobfoll,S.E.(Ed.).(1988).TheEcologyofStress.NewYork:Hemisphere.

Hobfoll,S.E.(1998).Thepsychologyandphilosophyofstress,cultureandcommunity.

NewYork:PlenumPress.

Hobfoll,S.E.(2001).Theinfluenceofculture,community,andthenested-selfinthe

stressprocess:Advancingconservationofresourcestheory.AppliedPsychology: AnInternationalJournal,50,337–421.

Hobfoll,S.E.,&Freedy,J.(1993).Conservationofresources:Ageneralstresstheory

appliedtoburnout.InW.B.Schaufeli,C.Maslach,&T.Marek(Eds.),Professional burnout:Recentdevelopmentsintheoryandresearch.(pp.115–129).Washington, DC:Taylor&Francis.

Jansen,N.W.,Kant,I.,Kristensen,T.S.,&Nijhuis,F.J.(2003).Antecedentsand

consequencesofwork-familyconflict:Aprospectivecohortstudy.Journalof OccupationalandEnvironmentalMedicine,45,479–491.

Jansen,N.W.,Kant,I.,vanAmelsvoort,L.G.,Kristensen,T.S.,Swaen,G.M.,&Nijhuis,

F.J.(2006).Work-familyconflictasariskfactorforsicknessabsence.

Occupa-tionalandEnvironmentalMedicine,63,488–494.

Johnson,H.A.M.,&Spector,P.E.(2007).Servicewithasmile:Doemotional

intelli-gence,gender,andautonomymoderatetheemotionallaborprocess?Journalof OccupationalHealthPsychology,12,319–333.

Judge,T.A.,Ilies,R.,&Scott,B.A.(2006).Work–familyconflictandemotions:Effects

atworkandathome.PersonnelPsychology,59,779–814.

Kinnunen,U.,&Mauno,S.(1998).Antecedentsandoutcomesofwork-familyconflict

amongemployedwomenandmeninFinland.HumanRelations,51,157–177.

Kossek,E.E.,Baltes,B.B.,&Matthews,R.A.(2011).Howwork-familyresearchcan

finallyhaveanimpactinorganizations.IndustrialandOrganizationalPsychology, 4,352–369.

Kossek,E.E.,Pichler,S.,Bodner,T.,&Hammer,L.B.(2011).Workplacesocialsupport

andwork-familyconflict:Ameta-analysisclarifyingtheinfluenceofgeneraland work–family-specificsupervisorandorganizationalsupport.Personnel Psychol-ogy,64,289–313.

Lapierre,L.M.,Spector,P.E.,Allen,T.D.,Poelmans,S.,Cooper,C.L.,O’Driscoll,M.

P.,&Kinnunen,U.(2008).Family-supportiveorganizationperceptions,multiple

dimensionsofwork–familyconflict,andemployeesatisfaction:Atestofmodel acrossfivesamples.JournalofVocationalBehavior,73,92–106.

Litwin,G.H.,&Stringer,R.A.,Jr.(1968).Motivationandorganizationalclimate.

Boston:HarvardUniversity.

Major,D.A.,Fletcher,T.D.,Davis,D.D.,&Germano,L.M.(2008).Theinfluence

ofwork-familycultureandworkplacerelationshipsonworkinterferencewith family:Amultilevelmodel.JournalofOrganizationalBehavior,29,881–897.

Maslach,C.(1982).Burnout:Thecostofcaring.EnglewoodCliffs,N.J.:Prentice-Hall.

Maslach,C.(2011).Engagementresearch:Somethoughtsfromaburnout

perspec-tive.EuropeanJournalofWorkandOrganizationalPsychology,20,47–52.

McMillan,L.H.W.,O’Driscoll,M.P.,&Burke,R.J.(2003).Workaholism:Areview

oftheory,researchandfuturedirections.InC.L.Cooper,&I.T.Robertson (Eds.),Internationalreviewofindustrialandorganizationalpsychology(18)(pp. 167–189).NewYork:Wiley.

Michel,J.S.,Kotrba,L.M.,Mitchelson,J.K.,Clark,M.A.,&Baltes,B.B.(2011).

Antecedentsofwork–familyconflict:Ameta-analyticreview.Journalof Organi-zationalBehavior,32,689–725.

Nahrgang,J.D.,Morgeson,F.P.,&Hofmann,D.A.(2011).Safetyatwork:A

meta-analyticinvestigationofthelinkbetweenjobdemands,jobresources,burnout, engagement,andsafetyoutcomes.JournalofAppliedPsychology,96,71–94.

Netemeyer,R.G.,Boles,J.S.,&McMurrian,R.(1996).Developmentandvalidation

ofwork–familyconflictandfamily–workconflictscales.JournalofApplied Psy-chology,81,400–410.

Oates,W.(1971).Confessionsofaworkaholic:Thefactsaboutworkaddiction.New

York:WorldPublishingCo.

Ostroff,C.,Kinicki,A.J.,&Tamkins,M.M.(2003).Organizationalcultureandclimate.

InW.C.Borman,D.R.Ilgen,&R.J.Klimoski(Eds.),HandbookofPsychology: IndustrialandOrganizationalPsychology(12)(pp.565–593).Hoboken,NJ:Wiley.

Promislo,M.D.,Deckop,J.R.,Giacalone,R.A.,&Jurkiewicz,C.L.(2010).Valuing

moneymorethanpeople:Theeffectsofmaterialismonwork–familyconflict. JournalofOccupationalandOrganizationalPsychology,83,935–953.

Richman,A.(2006).Everyonewantsanengagedworkforce-Howcanyoucreateit?

Workspan,49,36–39.

Schaufeli,W.B.,&Bakker,A.B.(2004).Jobdemands,job resources,andtheir

relationshipwithburnoutandengagement:Amulti-samplestudy.Journalof OrganizationalBehavior,25,293–315.

Schaufeli,W.B.,Bakker,A.B.,&Salanova,M.(2006).Themeasurementofwork

engagementwithashortquestionnaire:Across-nationalstudy.Educationaland PsychologicalMeasurement,66,701–716.

Schaufeli,W.B.,Leiter,M.P.,Maslach,C.,&Jackson,S.E.(1996).TheMaslachBurnout

Inventory-GeneralSurvey(MBI-GS).InC.Maslach,S.E.Jackson,&M.P.Leiter (Eds.),MBIManual(3rded,12,pp.22–26).PaloAlto,CA:Consulting Psycholo-gistsPress.

Schaufeli,W.B.,&Salanova,M.(2007).Workengagement:Anemerging

psycholog-icalconceptanditsimplicationfororganizations.InS.W.Gilliland,D.D.Steiner, &D.P.Skarlicki(Eds.),ResearchinSocialIssuesinManagement:Managingsocial andethicalissuesinorganizations(5)(pp.135–177).Greenwich:CT:Information AgePublishers.

Schaufeli,W.B.,Taris,T.W.,&VanRhenen,W.(2008).Workaholism,burnout,and

workengagement:threeofakindorthreedifferentkindsofemployee well-being?AppliedPsychology,57,173–203.

Schneider,B.(2000).Thepsychologicallifeoforganizations.InN.M.Ashkanasy,C.

P.M.Wilderon,&M.F.Peterson(Eds.),HandbookofOrganizationalCultureand Climate(pp.xvii–xxi).ThousandOaks,CA:Sage.

Schulte,M.,Ostroff,C.,&Kinicki,A.J.(2006).Organizationalclimatesystemsand

psychologicalclimateperceptions:Across-levelstudyofclimate-satisfaction relationships. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 645–671.

Schwartz,S.H.(1992).Universalsinthecontentandstructureofvalues:Theoryand

empiricaltestsin20countries.InM.Zanna(Ed.),AdvancesinExperimentalSocial Psychology(25)(pp.1–65).NewYork,NY:AcademicPress.

Schwartz,S.H.(1994).Arethereuniversalaspectsinthestructureandcontentsof

humanvalues?JournalofSocialIssues,50,19–45.

Schwartz,S.H.(2006).Lesvaleursdebasedelapersonne:Théorie,mesureset

appli-cations[Basichumanvalues:Theory,measurement,andapplications].Revue Franc¸aisedeSociologie,47,249–288.

Schwartz,S.H.(2012).AnoverviewoftheSchwartztheoryofbasicvalues.Online

ReadingsinPsychologyandCulture,2,1–20.

Scott,K.S.,Moore,K.S.,&Miceli,M.P.(1997).Anexplorationofthemeaningand

consequencesofworkaholism.HumanRelations,50,287–314.

Seppälä,T.,Lipponen,J.,Bardi,A.,&Pirttilä-Backman,A.M.(2012).Change-oriented

organizationalcitizenshipbehavior:Aninteractive productofopennessto changevalues,workunitidentification,andsenseofpower.Journalof Occu-pationalandOrganizationalPsychology,85,136–155.

Sharone,O.(2004).Engineeringoverwork:Bell-curvemanagementatahigh-tech

firm.InC.FuchsEpstein,&A.L.Kalleberg(Eds.),Fightingfortime:Shifting bound-ariesofworkandsociallife(pp.191–218).NewYork:RussellSageFoundation.

Shimizu,T.,Feng,Q.,&Nagata,S.(2005).Relationshipbetweenturnoverandburnout

amongJapanesehospitalnurses.JournalofOccupationalHealth,47,334–336.

Smelser,N.J.(1998).Therationalandtheambivalentinthesocialsciences.American

SociologicalReview,63,1–16.

Snir,R.,Harpaz,I.,&Ben-Baruch,D.(2009).Centralityofandinvestmentinworkand

familyamongIsraelihigh-techworkers:Abiculturalperspective.Cross-Cultural Research,43,366–385.

Sonnentag,S.(2003).Recovery,workengagement,andproactivebehavior:Anew

lookattheinterfacebetweennon-workandwork.JournalofAppliedPsychology, 88,518–528.

Soper,D.S.(2014).Sobeltestcalculatorforthesignificanceofmediation[Software].

Retrievedfromhttp://quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm

Taris,T.(2006).Istherearelationshipbetweenburnoutandobjectiveperformance?

Acriticalreviewof16studies.WorkandStress,20,316–334.

Taris,T.W.,Schreurs,P.J.G.,&VanIersel-VanSilfhout,I.J.(2001).Jobstress,job

strain,andpsychologicalwithdrawalamongDutchuniversitystaff:Towardsa dual-processmodelfortheeffectsofoccupationalstress.WorkandStress,15, 283–296.

Tziner,A.,&Sharoni,G.(2014).Organizationalcitizenshipbehavior,organizational

justice,jobstress,andwork-familyconflict:Examinationoftheir interrela-tionshipswithrespondentsfromanon-Westernculture.JournalofWorkand OrganizationalPsychology,30,35–42.

VanDerPompe,G.,&Heus,P.D.(1993).Workstress,socialsupport,andstrains

amongmaleandfemalemanagers.Anxiety,StressandCoping,6,215–229.

Vardi,Y.(2001).Theeffectsoforganizationalandethicalclimatesonmisconductat

work.JournalofBusinessEthics,29,325–337.

Wright,T.A.,&Cropanzano,R.(1998).Emotionalexhaustionasapredictorofjob

performanceandvoluntaryturnover.Journalof.AppliedPsychology,83,486–493.

Zohar,D.,&Luria,G.(2005).Amultilevelmodelofsafetyclimate:Cross-level