Revista

de

Administração

http://rausp.usp.br/ RevistadeAdministração52(2017)219–232

Human

Resources

and

Organizations

Cultural

intelligence,

cross-cultural

adaptation

and

expatriate

performance:

a

study

with

expatriates

living

in

Brazil

Inteligência

cultural,

adapta¸cão

transcultural

e

o

desempenho

de

expatriados:

um

estudo

com

expatriados

residentes

no

Brasil

Inteligencia

cultural,

adaptación

transcultural

y

desempe˜no

de

expatriados:

un

estudio

con

expatriados

residentes

en

Brasil

Inácia

Maria

Nunes

∗,

Bruno

Felix,

Lorene

Alexandre

Prates

Funda¸cãoInstitutoCapixabadePesquisasemContabilidade,EconomiaeFinan¸casBusinessSchool,Vitória,ES,Brazil

Received4February2015;accepted22November2016 Availableonline18May2017

ScientificEditor:MariaSylviaMacchioneSaes

Abstract

Developingacompetitiveworkforceabroadisarelevantchallengetoorganizationswithmultinationalactivities.Inviewofthis,addedtothe highcostsassociatedwithexpatriation,itisnecessarytoidentifythefactorsthatfacilitateasatisfactoryperformanceofexecutivesininternational assignments.Thus,thepurposeofthisworkistoinvestigatetherelationshipbetweenculturalintelligence,cross-culturaladaptationandexpatriates performance.Basedonasampleof217expatriatesfrom26countrieslivinginBrazil,theresearchrevealsapositiveassociationbetweencultural intelligenceandcross-culturaladaptation,andthelatterwithexpatriates’performance.However,thedirectrelationshipbetweenculturalintelligence andexpatriatesperformancewasnotsignificant.Theresultsalsorevealedanindirectrelationshipbetweenculturalintelligenceandexpatriates performancemediatedbycross-culturaladaptation.Thus,wesuggestthatculturalintelligenceconvertsitselfintotheabilityoftheexpatriateto betteradapttothenewculture,whichthenresultsinperformance.BasedonAllport’sContactTheory(Pettigrew,1998),whichhastheassumption thatincreasedinteractionsbetweenmembersofdifferentethnicgroupscanleadtoincreasedmutualunderstanding,reducehostilities,prejudices andtheformationoffriendshipsbetweengroupsindifferentsocialcontexts(Kim,2012;Pettigrew&Tropp,2006),wethussuggestthatthis transformationprocessisfacilitatedandpoweredbytheincreaseofinteractionsbetweenexpatriatesandthehostcountrynationals.Suggestions forfutureresearchandforpracticearepresented.

©2017DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords:Cross-culturaladjustment;Culturalintelligence;Expatriateperformance

Resumo

Criarumaforc¸adetrabalhocompetitivanoexterioréumdesafiorelevanteparadiversasorganizac¸õescomatividadesmultinacionais.Diante distoedosaltoscustosassociadosàexpatriac¸ão,faz-senecessárioidentificarfatoresquefacilitamodesempenhosatisfatóriodeexecutivosem designac¸õesinternacionais.Assim,oobjetivodestetrabalhofoiavaliararelac¸ãoentreinteligênciacultural,adaptac¸ãotransculturaledesempenho deexpatriados.Apartirdeumaamostrade217expatriados,provenientesde26paísesdiferenteseresidentesnoBrasil,oestudorevelouuma

∗Correspondingauthorat:AvenidaFernandoFerrari,1358,CEP29075-505,Vitória,ES,Brazil. E-mail:inaciamn@gmail.com(I.M.Nunes).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofDepartamentodeAdministrac¸ão,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸ãoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeSãoPaulo –FEA/USP.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2017.05.010

associac¸ãopositivaentreinteligênciaculturaleadaptac¸ãotransculturale,destaúltima,comodesempenhodeexpatriados.Noentanto,arelac¸ão diretaentreinteligênciaculturaledesempenhodeexpatriadosnãosemostrousignificante.Osresultadosrevelaram,ainda,umarelac¸ãoindireta entreinteligênciaculturaledesempenhodeexpatriadosmediadapelaadaptac¸ãotranscultural.Assim,sugere-sequeainteligênciaculturalse transformaemcapacidadedemelhoradaptac¸ãodoexpatriadoànovacultura,paraentãoresultaremdesempenho.ApartirdaTeoriadoContato deAllport(Pettigrew,1998),cujopressupostoédequeoaumentodasinterac¸õesentreosdiferentesmembrosdegruposétnicospodelevarao aumentonoentendimentomútuo,àreduc¸ãodehostilidades,depreconceitoseàformac¸ãodeamizadesentregruposemdiversoscontextossociais (Pettigrew&Tropp,2006;Kim,2012),sugere-sequeesteprocessodetransformac¸ãoéfacilitadoepotencializadopeloaumentodasinterac¸ões entreexpatriadosehabitanteslocais.Sugestõesparafuturaspesquisaseparaapráticasãoapresentadas.

©2017DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palavras-chave: Adaptac¸ãoTranscultural;InteligênciaCultural;DesempenhodosExpatriados

Resumen

Crearunafuerzadetrabajocompetitivaenelextranjeroesunimportanteretoparamuchasorganizacionesquedesarrollanactividades multina-cionales.Porelloyenvistadelosaltoscostosasociadosconlaexpatriación,esnecesarioidentificarlosfactoresquefacilitanelbuendesempe˜node losejecutivosenasignacionesinternacionales.Elobjetivoenestetrabajoesevaluarlarelaciónentreinteligenciacultural,adaptacióntransculturaly rendimientodeexpatriados.Apartirdelanálisisdeunamuestrade217expatriadosprocedentesde26países,quevivenenBrasil,puedeobservarse unarelaciónpositivaentreinteligenciaculturalyadaptacióntranscultural,ydeéstaconeldesempe˜nodelosexpatriados.Sinembargo,larelación directaentreinteligenciaculturalydesempe˜nodelosexpatriadosnoessignificativa.Losresultadostambiénmuestranunarelaciónindirectaentre inteligenciaculturalyrendimientodeexpatriadosmediadaporlaadaptacióncultural.Así,sesugierequelainteligenciaculturalseconvierteen unacapacidaddemejoradaptacióndelexpatriadoalanuevacultura,paraentoncesdarlugaralrendimiento.Conbaseenlateoríadelcontacto deAllport(Pettigrew,1998)–cuyahipótesisesdequeelaumentodelasinteraccionesentrelosmiembrosdediferentesgruposétnicospuede conduciraunamayorcomprensiónmutua,alareduccióndehostilidadesyprejuiciosyalaformacióndeamistadesentregruposendiversos contextossociales(Pettigrew&Tropp,2006;Kim,2012)–sesugierequeesteprocesodecambiosevefacilitadoyreforzadoporelaumentode lasinteraccionesentrelosexpatriadosyloshabitanteslocales.Sepresentansugerenciasparafuturosestudiosyparalapráctica.

©2017DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteesunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palabrasclave: Adaptacióntranscultural;Inteligenciacultural;Desempe˜nodeexpatriados

Introduction

The search for new markets and better conditions in the productionprocesshaveencouragedcompaniestoextendtheir bordersbeyondtheircountryoforiginandtotransfertheir pro-fessionalstooverseassubsidiaries.Thispractice,expatriation, aimstosolveproblemssuchasthelackoflocalprofessionals withtechnicalormanagementskills,and/orfacilitatethe imple-mentationofnewprojects(Lee&Sukoco,2010;Rose,Ramalu, Uli,&Kumar,2010).

Multinational companies that practice expatriation, not rarely, face problems of work stoppage, abandonment of position, earlyreturnand poor performanceof the expatriate (Wu&Ang,2011);thus,factorsaffectingtheexpatriate’sjob performancehavedrawntheattentionofresearchers(Cheng& Lin,2009;Ramalu,Rose,Uli,&Kumar,2012;Shih,Chiang, &Hsu,2010).

Thecross-culturaladaptationisconsideredasanimportant antecedentofjobperformance,determinedbythedegreeofease and/ordifficultythattheexpatriatefacesintheirpersonallifeand atwork(Lee&Sukoco,2010),and(Lee&Vorts,2010;Shay &Baack,2006).Theabilitytoadapthasapositiveimpacton thequalityoftheexpatriate’sinteractionwiththehostcountry nationalsandonthe degreeof comfortof the professionalin their workand, consequently,ontheir performance(Kraimer, Wayne,&Jaworski,2001).

Understanding the effects of cross-cultural adaptation on performance and factors influencing expatriate adaptation direct the research in this field. For example, Black (1988),

Black,Mendenhall,andOddou(1991)andBlack,Gregersen, andMendenhall(1992)presentacategorizationofthe factors that influence the adaptation of the expatriate, serving as a theoreticalsupportforotherstudiesthatexploretheimpactof specificfactors,suchasinthecaseofculturalintelligence(Ang etal.,2007;Lee&Sukoco,2010;Ramalu,Wei,&Rose,2011;

Ramaluetal.,2012).

Previousresearchalsoconsidersculturalintelligence–which istheindividual’sabilitytointeractsatisfactorilyincultural sett-ings withdistinctethnicgroups andnationalities(Ang etal., 2007),asamanifestedvariablethathasbeenpresenting posi-tivecorrelationwithcross-culturaladaptationandtheexpatriates performance(Angetal.,2007;Ramaluetal.,2011).

Studies examining the relationshipbetween cultural intel-ligence, cross-culturaladaptation andexpatriateperformance, are mostly limited to a single manifest variable and rarely analyze the relationshipbetween the threelatent variablesin a single model (e.g., Ang et al., 2007; Ramalu et al., 2011; Rose etal., 2010; Shay &Baack, 2006).Whenthis isdone, the surveys have presented divergent results. For example,

divergeas tothe effectofculturalintelligence andexpatriate performance. Therefore, further research is needed on the complexrelationshipsofexpatriateperformance.

Another aspect observed in previous studies that analyze this relationship is the existence of a selection bias, as the sample is characterized only by Asian expatriates working in multinational companies in Asia (Lee & Sukoco, 2010; Ramaluetal.,2012).Thelackofresearchinothercountriesand continents highlights the need to conduct studies containing expatriates from other countries and in various places (Ang etal.,2007;Lee&Sukoco,2010).

Wecanalsoobserveatheoreticalgap,sincethereisno thor-oughinvestigationintheliteratureregardingtheinfluencethat ahighlevelofculturalintelligencemaygenerateonthe perfor-manceofexpatriates.Ifthosewhoaremoreculturallyintelligent presentagreatercapacitytointeractindifferentenvironments andifexecutiveperformanceisbasicallyaresultofinteractions betweenagents,whyisitthatinparticularstudiesnorelationship betweenculturalintelligenceandperformanceisfound?

In Brazil the literature that investigates Brazilian expatri-ates and those of other nationalities in assignments in the country is still not largely explored (Araujo, Teixeira, Cruz, &Malini,2012;Araujo,Broseghini,&Custodio,2013;Cota, Emmendoerfer, Reis, & Silva, 2015; Kubo & Braga, 2013; Rosal,2015).QuantitativeBrazilianstudiesthatseekto under-stand the relationship between the personal background of expatriatesintheiradaptationprocessarealsoscarce(Moreira, Bilsky,&Araujo,2012),indicatingthatthisisafertilefieldfor furtherresearch.Thus,giventherelevanceofthetopicfor orga-nizationsandthegapspointedoutintheliterature,thisresearch seekstoanswerthefollowingquestion:Whatisthe relation-shipbetweenculturalintelligence,cross-culturaladaptation andexpatriateperformance?

From the above researchproblempresented, the objective of this study is toevaluate the relationship between cultural intelligence,cross-cross-culturaladaptationandexpatriate per-formanceassignedtoworkinBrazil.

This study contributes to the literature on International HumanResources by assessingthe relationshipbetween cul-turalintelligenceandexpatriateperformance,andbyexamining the mediating effectof cross-cultural adaptation inthis rela-tionship.Thediscussionofsuchrelationshipsaccordingtothe Contact Theory also adds to existing studies, by broadening theunderstandingofthecross-culturaladaptationprocessfrom theunderstandingofinterpersonal-intergrouprelationships,and howtheserelationshipscanpromotecross-culturaladaptation andenhance culturalintelligenceandexpatriateperformance. Asforpracticalrelevance,thisworkintendstocontributeinthe processofteamformationinmulticulturalenvironments, profes-sionalselectionandtrainingprocesses,increasingthepossibility ofmissionsuccess.

Theoreticalframework

Contacttheory

Closeinterpersonalrelationshipscontributetothewell-being and happiness of individuals (Novak, Feyes, & Christensen,

2011),so when the expatriate developspositiverelationships withhisco-workersandwiththelocalpopulation,he/she cre-atesanenvironmentconducivetoadaptation(Black,1988;Black etal.,1991).

Qualityinterpersonalrelationshipsaremoreeasilydeveloped amongpeoplewhobelongtothesamegroup,similarinrelation toage,raceandgender.However,itispreciselyinsituationsof greatdiversity,asinthecaseofexpatriateswhofindthemselves onmissioninanewcountry,thatcontactinterventionsaremost needed(Turner&Crisp,2009).

The barriersthat hinderthe developmentof positive inter-personalrelationships are the fruitsof feelings and opinions, simplistic ingeneral,ifnot misguided,whichis theoutcome ofasingleexperimentorapreconceivedimagebytheirsocial group,whichinturnistheresultoftheperceptionofdissimilarity relatedtorace,ethnicityandculture(Kim,2012).

Interactionsbetweengroupsrequirepeople’scognitive abil-ities such as behavioral control, self-regulation and thought suppression.Incaseswhereintergroupcontactisoflow qual-ity,permeatedbyprejudiceandstigma,i.e.,presentingahigh degreeofstress,thereisatemporaryimpairmentof cognitive abilities,increasingthe propensityofanindividualtoalower performanceinactivitiesthatrequire suchskills(Richeson& Shelton,2003).

Richeson and Shelton (2003) when investigating possible cognitiveconsequencesarisingfromintergroupcontact, iden-tifiedthatnegativeeffectsoncognitiveabilitiesresultingfrom stressful intergroup interactions may cease to exist through repeatedpositive interactionswiththe samestigmatized peo-ple,since theamountof intergroupcontact tendstocorrelate negativelywithprejudice.Otherstudiesreinforcethe proposi-tionthat interpersonal/intergroupcontactcanreduceandeven overcomethebiasesofperception(Allport,1954;Kim,2012; Pettigrew,1998;Toit&Quayle,2011;Turner&Crisp,2010).

Inthestudiesonthephenomenaofintergrouprelationships,

Allport(1954)andPettigrew(1998)proposetheContactTheory whoseassumptionisthattheincreaseofinteractionsbetween differentmembersofethnicgroupscanleadtoincreasedmutual understanding, the reduction of hostilitiesandprejudices and theformationof friendshipsbetweengroupsinvarioussocial contexts(Kim,2012;Pettigrew&Tropp,2006).

Thepositiveeffectsofintergroupcontactareenhancedwhen the interaction meets the following criteria: opportunities of interaction;individualswithsimilarsocialstatus;commongoals andobjectivesandcooperationwithinthecontactsituation;the existenceofinstitutionalsupport,supportfromtheauthorities, lawsorlocalcustoms(Allport,1954;Pettigrew&Tropp,2006). In theseconditions ofidealcontactpeopleareexpectedtobe able to reduce negative stereotypes and prejudices, discover inconspicuoussimilaritiesanddifferences(Kim,2012).

encounterscanbeextendedtoothergroups,asitispossibleto establishothercontactsettings.

Alternativewaysof direct contact(facetoface) arebeing researched, such as the prolonged contact that occurs when aningroupmemberhasacloserelationshipwithanoutgroup member.Inthissituation,themereknowledgeof thepositive relationshipofthismemberpositivelyimpactsonotheringroup members.

Theformofprolongedcontacthasbeenassociatedwithbetter intergroupattitudes, because itcanallowpeopletoindirectly experiencethepositiveeffectsofcontact,avoidingtheanxiety ornegativefeelingsthat canarisefromdirectcontact(Toit& Quayle,2011).

Anotheralternativeformofcontactistheimaginedcontact, inthiscase, itisassumed that mentallysimulating apositive encounterinaspecificsocialsituationcanproduceeffects sim-ilartothosethatwouldbeobtainedinrealexperience(Turner & Crisp, 2009,2010). Thus,this type of contact can reduce anxiety, negativestereotype and improve intergroup attitudes (Turner,Crisp,&Lambert,2007).

Theeffectoftheimaginedcontactinthechangeofattitudeis lesspowerfulthanindirectandprolongedcontact,ontheother hand,itisasimple,flexibleandeffectivemeansofpromoting morepositiveperceptionsofexternalgroups(Turner&Crisp, 2010).

AlthoughtheContactTheoryhasbeenatheoreticalsupport for numerousresearchonpositiveinterpersonalrelationships, established betweenindividuals of different ethnicandracial groups,itcanalsoserveasatheoreticalframeworkforstudies involvingothergroups(Pettigrew&Tropp,2006),asinthecase ofprofessionalswhoareassignedtopositionsandfunctionsin othercountries.

Theinterpersonalrelationships of theexpatriatedeveloped withthelocalinhabitantscaninfluencethedegreeofadaptation andenhance the capacityof the expatriateto deal satisfacto-rilywiththedemandspresentedinthisnewculture.Thus,this researchproposestoinvestigatethetypeofrelationshipbetween Cross-culturalAdaptation,CulturalIntelligenceandExpatriate PerformanceinthelightofContactTheory.

Culturalintelligence

Regardingtheindividual’sabilitytosuccessfullyadapttonew andunfamiliarculturalsettings,alongwiththeirabilitytoeasily andeffectivelyfunctioninsituationscharacterizedbycultural diversity, theterm culturalintelligenceisapplied(Angetal., 2007;Earley&Ang,2003).Itisamultidimensionalconstruct composedbythefollowingdimensions:cognitive, metacogni-tive,motivationalandbehavioral(Angetal.,2007;Ramaluetal., 2011).

Thecognitivedimensionisrelatedtothegeneralknowledge ofdifferentcultures,suchasknowledgeontheeconomic,legal andsocialsystem, andon thebasic structuresof the cultural values of different cultures and subcultures (Triandis, 2006). Suchknowledgecanbeacquiredthroughformalandinformal education,resultingfrompreviousexperiences.

The mental processes used in capturing the new cultural knowledge are given through the metacognitive dimension (Kumar,Rose,&Ramalu,2008),whichallowstheindividualto control andprocessthe informationofthe newculture (Ang, Dyne, Koh, &Ng, 2004), and to generate coping strategies (Earley,Ang,&Tan,2006).Thisculturalawarenessisreflected inplanningandmonitoringactionsandintheabilitytoperforma reviewofmentalmodelsofculturalnormsenablingthe individ-ualtoquestionculturalassumptionsandtheirmentaladjustment modelduringandaftertheinteractions(Triandis,2006).

Themotivationaldimensionreflectsthedesiretointeractwith localpeopleandtoadapttothenewculture.Inthisdimension, theabilitytochannelattentionandenergytowardlearningand thefunctioninginsituationscharacterizedbyculturaldifference ishighlighted(Angetal.,2007).

Finally,thebehavioraldimensionistheabilitytoengagein adaptivebehaviorsaccordingtocognitionandmotivation,i.e.,it representsasetofimportantbehaviorstobeusedinthedifferent situations of interaction(Kumar et al., 2008;Lee & Sukoco, 2010).

Thesefourdimensionssynthesizeskillsthatenablethe indi-vidualtobetteradapttolifeinaculturalcontextotherthanthat oforigin,sinceitenablestheindividualtopredicttheattitudes andbehaviorsexpectedanddesiredforagivenculture(Earley &Peterson, 2004;Lee &Sukoco, 2010).Thispaper outlines theinterestindiscussingsuchaconceptintheexpatriate con-text, who is an employee sent by their company on mission toothercountriesforthepurposeofcarryingoutprofessional activities(Wu&Ang,2011).Itisexpectedfortheindividual, withhighlevelofculturalintelligence,tohavegreaterabilityto identify,recognizeandreconcileculturaldifferences,by prop-erly adjustingtheirthinking,behaviorandmotivationintheir daily operations(Earleyetal., 2006).Basedonthisidea,the association betweenthe concepts of culturalintelligenceand cross-culturaladaptationisrecurrentintheliterature.

Cross-culturaladaptationofexpatriates

Cross-culturaladaptationisthedegreeofpsychological com-fortoftheexpatriatebeforethefacilitiesanddifficultiesfacedin thehostcountry(Black,1988;Lee&Vorst,2010).Considered as oneofthe mainfactorsexplainingsuccessininternational assignments,it isconceivedas aconstructcomposedofthree dimensions(Black,1988;Blacketal.,1991).

Thework-relatedadaptationdimensionreferstothe psy-chologicalcomfortoftheexpatriateinrelationtothedemandsof their newpost,e.g.:tasks,responsibility,leadership,and rela-tionship withcolleagues. Thegeneral adaptation dimension concernsthegeneralconditionsoflifeandcultureoftheforeign country,suchasfood,transportsystem,shopping,entertainment andclimate.And,thedimensionofinteractionadaptationwith thelocalinhabitantsofthecountrydealswithrelationshipswith localpeopleoutsidetheworkenvironment(Black,1988;Black etal.,1991).

addresssimilarphenomena,thesetwotheoreticalconstructs dif-ferin their nature. Whereas Behavioral Cultural Intelligence refers to the ability to adapt and emulate behaviors typical of a distinct culture (like speaking in a halting way when expressing oneself in Japanese or being moregestural when speaking the Italian language for example), the Adaptation toInteraction with localsaddresses the sense of psychologi-cal adjustmentthat the individual gets when interacting with locals. It is possible that concepts are not present simulta-neously, which can happen for example when an expatriate adjuststhevolumeoftheirvoicewhenspeakingwithItalians,but isuncomfortablewiththedegreeofinformalitywithwhichthey communicate.

Recentresearchindicatesthatcross-culturaladaptationhas culturalintelligenceasitsmanifestvariable,withitbeing consid-eredasaninterculturalcompetencethatfacilitatestheprocess of adaptationof the expatriate(Ramalu etal., 2011).Results foundinthe study byRamalu et al.(2011)show that ahigh level of cross-cultural adaptation is related tothe high level ofmetacognitiveculturalintelligenceandmotivationalcultural intelligence;aswellas thehigher level ofinteraction adapta-tionisrelatedtothehigherlevelofmetacognitive,cognitiveand motivationalculturalintelligence;andfinally,agreater adapta-tionof theworkisrelatedtothe higherlevel ofmotivational culturalintelligence.

Theeffectiveadaptationoftheexpatriateintheirnew coun-trynecessarilyinvolvestheabilitytodealadequatelywiththe stressfulsituations arisingfrom the different cultural context (Angetal.,2007;Earley&Ang,2003).Inordertoovercome theinitialstagesoftheadaptationprocessitisnecessaryforthe expatriatetolearnaboutthenewculture inordertoachievea degreeofpsychologicalcomfort.

From theContact Theoryone cansuppose,in the caseof thisstudy, thatdevelopingpositiveinterpersonalrelationships withlocal people, inside and outside of work, will facilitate the adaptation of the expatriate inthe newenvironment, just asanincreaseofinteractions, infrequencyandinthenumber ofdifferentpeoplecanenhancethelearningofthe particulari-tiesofthenewculture.Thus,thisnewknowledgereflectsasan opportunityfortheexpatriatetoreviseassumptionsand gener-alizationsaboutthelocalinhabitants,becomingmoreawareof possibledistortionsofjudgmentarisingfromprejudiceandthe pejorativestereotype(Erasmus,2010;Novaketal.,2011;Shay &Baack,2006;Toit&Quayle,2011).

In buildinganetworkof contacts withcloseinterpersonal relationships,bydevelopingnewfriendships,contributestothe well-beingofpeople(Novaketal.,2011).Weassumethatthe interactionandknowledgeresultingfromcontact,whilstit facil-itates the adaptation process, it also promotes psychological comfortand enhancestheprocess of transformingthe ability ofculturalintelligenceintobetteradaptation,asthesewillallow theexpatriatetocontrolandprocesstheinformationofthenew culture.

Thus,consideringthepropositionthatindividualswithahigh levelofculturalintelligencehaveabetterabilitytounderstand andnavigateunknownenvironments,conceptuallyspeaking,we suggestthatculturalintelligencecancontributetothelevelof

adjustmentinitsdifferentdimensions(Earleyetal.,2006).From theabove,thefollowinghypothesisisraised:

H1. Thereis asignificantandpositiverelationshipbetween culturalintelligenceandcross-culturaladaptation.

Expatriateperformance

Expatriateperformanceisamultidimensionalconstruct com-prisedbythedimensions:cross-culturaladaptation,compliance withtheinternationalassignment andperformanceduringthe assignment (Cheng & Lin, 2009; Forster & Johnson, 1996;

Schuler,Fulkerson,&Downling,1991).

Theperformanceevaluationofexpatriatestookplacethrough theperformancedimensionduringtheassignment,asthe par-ticipantsofthissurveywerestillcommittedintheirmissions, andcross-culturaladaptation isalreadyoneofthe researched constructs.Itisworthmentioningthatcross-culturaladaptation andthefulfillmentoftheassignment,arediscriminantconstructs thatpresentatheoreticalrelationshipwithperformance,butdo notconstituteit.

The dimensionof performanceduringassignmentconsists ofthefacets:production(goalsachievementsandthe manage-ment’s efficiency); management of local employees(suitable leadershiptoachievegoals);andthereadingoftheenvironment (theabilitytorelateappropriatelywithpeopleofinfluence,with thelocalgovernmentandwiththesectorsofsocietyofthehost country)(Cheng&Lin,2009).

Thenewly arrivedexpatriatefacesdifferentpolitical,legal andsocialenvironments.Thissituationgeneratesstress,fatigue andmaybeaggravatedbytheexpatriate’smaladjustment, fur-ther increasing the pressure being experienced, which will result innegativeattitudestowardthe assignmentabroadand thefeelingofdissatisfaction,negativelyimpactingthe expatri-ate’srelationshipwithworkandunderminingtheirperformance (Kraimeretal.,2001;Shihetal.,2010).

Thus, understanding the performance from the adaptation process allows us to identify the existence of relationships betweencross-culturaladaptationandexpatriateperformance. Inthisdirection,CaligiuriandTung(1999),wheninvestigating the genderdifferencesinrelationtocross-cultural adaptation, expatriateperformanceandthedesiretocompletetasks,found apositiverelationshipbetweenthe generaladaptation dimen-sionandtheself-assessmentofperformanceadaptationatwork.

Kraimeretal.(2001)andShayandBaack(2006),alsofounda positiverelationshipbetweenthedimensionsofcross-cultural adaptationandexpatriatesperformance.

Cultural intelligence is another factor that, according to the literature,has animpacton the expatriates’ performance.

andtherefore,minimizingmisunderstandingsthatmayreflecton performance.

Studies investigating the relationship between the three constructs, cross-cultural adaptation,cultural intelligenceand expatriateperformance show somedivergent results.Ramalu etal.(2011)andRoseetal.(2010)identifiedapositive relation-shipbetweenculturalintelligenceandexpatriateperformance, suggestingthatindividualswithahighlevelofcultural intelli-gencetendtoperformbetteratwork.

Ramalu et al. (2012), similar to previous authors, identi-fied in their results that the variation in the performance of expatriates that is attributable tocultural intelligence, occurs throughadirectrelationship;i.e.,culturalintelligence (indepen-dentvariable)predictsthecross-culturaladaptation(mediating variable)whichinturn,predictsexpatriatesperformanceatwork (dependentvariable),suggestingthatindividualswithhighlevel ofculturalintelligencetendtoadaptbettertothenewcultural environmentandaremorelikelytoachievebetterperformance atwork.

Ontheotherhand,resultsbyLeeandSukoco(2010),when investigating themediatingeffectof adaptation,diverge from previous studies, by showing that thereis no direct effectof culturalintelligenceonexpatriatesperformance;withitbeing necessaryfor culturalintelligencetoturn intoadaptation and culturaleffectivenessbeforetheyresultinbetterperformance. Anotherrelevantfinding,raisedbytheauthors,isthatthelevelof theexpatriate’scross-culturaladaptationdoesnotdirectly influ-encethelevelofperformanceeither,implyingthatpsychological comfortmustfirstturnintoasetofoperationalcapabilities.The divergentresults onthe typeof relationship betweencultural intelligence, cross-cultural adaptation and expatriate perfor-manceshowtherelevanceofnewstudiesinthisfield.

Compliancewiththespecificrequirementsofthetaskandthe abilitytodevelopandmaintainrelationshipswithpeoplefrom thehostcountryareessentialaspectsoftheexpatriate’s perfor-mance(Lee&Vorst,2010).Thisisthecasewithskillsrelatedto culturalintelligenceandcross-culturaladaptationsuchas:rich culturalschemesthatwillallowamorepreciseunderstanding oftheexpectationsinherenttotheirnewrole;thecompetence toknowwhenandhowtoapplytheirculturalknowledge,using theirmultiplestructuresofknowledgeaccordingtothecontext; persistenceinthepracticeofnewbehaviors;andaflexibleset of behaviorthatwill positivelyreflect theperformanceofthe expatriate(Angetal.,2004;Angetal.,2007;Kraimeretal., 2001;Lee&Vorst,2010).Therefore,wesuggestthat:

H2. Culturalintelligenceispositivelyandsignificantly corre-latedwithexpatriateperformance.

H3. Cross-cultural adaptation ispositively and significantly correlatedwithexpatriateperformance.

Methodology

Basedonthehypotheses presented andthe purpose ofthe research,whichistoevaluatetherelationshipbetweenCultural Intelligence, Cross-culturalAdaptation andExpatriate Perfor-manceinadiversifiedsample,thefollowingtopicsincludethe

Table1

Distributionofexpatriates.

Continent Country No. %

Europe Belgium 1 0.5

Denmark 2 0.9

Finland 3 1.4

Netherlands 3 1.4

France 7 3.2

Italy 7 3.2

Portugal 17 7.8

Spain 12 5.5

England 10 4.6

Ireland 8 1.8

Sweden 8 1.8

Germany 6 2.8

Norway 6 2.8

NorthAmerica Canada 8 1.8

Mexico 14 6.5

UnitedStates 43 19.8

LatinAmerica Ecuador 1 0.5

Uruguay 5 2.3

Venezuela 7 3.2

Argentina 19 8.8

Colombia 8 3.7

Peru 8 3.7

Asia China 14 6.5

Japan 10 4.6

Oceania Australia 1 0.5

NewZealand 1 0.5

description of the sample, the instrumentsfor collectingand analyzingthedata.

Sample

Thisresearchconsistsofasampleof217expatriatesof dif-ferentnationalitiesresidinginBrazilandweuseddatacollection instrumentsthataddupto41itemsandtherefore,bytakinginto account theminimum criteria, that is,the numberof respon-dentsismorethanfivetimesthenumberofassertions(Junior, Anderson,Tatham,&Black,2005).

Sampleprofile

Theresearchwasdevelopedwithadiversifiedsample, con-sistingofexpatriatesfrom26differentcountries,distributedon fivecontinents,withapredominanceofUSexpatriates(19.8%), followedbyArgentines(8.8%)andPortuguese(7.8%).The dis-tributionofexpatriatesinrelationtothecontinentsandcountries oforiginisshowninTable1.

Inthefaceofdiversity,thesamplereasonablyreflectedthe overall demographic profile of expatriates identified by the

BGRS(2012).Thecharacterization ofthesample interms of gender, age, number of children, time inBrazil, hierarchical levelandinternationalexperienceisdescribedinTable2.

Table2

Profileofparticipants.

Profileofparticipants No. %

Gender Male 193 89

Female 24 11

Agerange Upto35years 33 15

Between36and40years 40 18

Between41and45years 58 27

Between46and50years 51 24

From51onwards 35 16

Maritalstatus Married 143 66

Livingwiththeirpartner 74 34

Numberofchildren None 53 24

1child 82 38

2children 58 27

3childrenormore 24 11

TimeinBrazil Between12and24months 55 25

Between25and36months 58 27

Between37and48months 91 42

From49monthsonwards 13 6

Hierarchicallevel Managementposition 203 94

Non-managerial 14 6

Previousexperienceinexpatriation Yes 65 30

No 152 70

Measures

Theconstructsofculturalintelligence,cross-cultural adap-tationandexpatriateperformanceweremeasuredusingscales previously developed and validated, used in its original lan-guage(English),sincerespondentshaddominionoverthesame language.

Culturalintelligencewasmeasured fromthescaleby Ang etal.(2007)termedasCulturalIntelligenceScale(CQS),with 20itemsdistributedamongthemetacognitive,cognitive, moti-vationalandbehavioraldimensions.Previousstudies,such as

Kumar etal.(2008),Ramalu et al.(2011)andRamalu et al. (2012),alsoadoptedtheCQS.Thescaleincludesitemssuchas: “IadjustmyculturalknowledgeasIinteractwithpeoplefrom aculturethatisunfamiliartome”(MetacognitiveDimension), “Iknowtherulesfor expressingnonverbalbehaviorsinother cultures”(CognitiveDimension),“Ienjoyinteractingwith peo-ple fromdifferent cultures”(Motivational Dimension) and“I changemynon-verbalbehaviorwhenacross-culturalsituation requiresit”(BehavioralDimension).

Cross-culturaladaptation wasmeasuredusing thescaleby

Black(1988)andBlackandStephens(1989),havingbeenused previouslyinresearchbyLee andSukoco(2010),Jenkis and Mockaitis(2010)andPeltokorpiandFroese(2009).Thisscale consists of three first-orderconstructs: work, interaction and generaladaptation.Examplesof itemscontained inthisscale are:“Howadjustedareyoutoyourjobresponsibilities?”(Work Adaptation),“How adjustedare you toworkingoutside your company?”(InteractionAdaptation)and“Howadjustedareyou totheweatherinBrazil?”(GeneralAdaptation).

We evaluated expatriate performance using the scale by

ChengandLin(2009),previouslyusedbyWuandAng(2011). This scale reflects the theoretical framework being used,

coveringthethreeaspects/facetsoftheperformancedimension duringtheassignment,whichare:production,localemployees management andreadingthe environment.The choiceofthis measurement instrumentis due tothe fact that the scales by

BlackandPorter(1991)andCaligiuriandTung(1999),usedin previousstudies(Roseetal.,2010;Ramaluetal.,2011,2012), were inconsistent inthe degreeof adequacy of psychometric propertiesforthemeasurementoftheexpatriate’sperformance incontextualandtask-specificdimensions.Thescalecontains itemssuchas:“I’veassistedthestationedsubsidiarytoachieve the pre-determined production goal in an acceptable level” (ProductionDimension),“I’veassistedthestationedsubsidiary toeffectivelyandusefullysuperviselocalworkersinan accept-ablelevel”(ManagementofLocalEmployeesDimension)and “I’veassistedthestationedsubsidiarytofacilitatehostcountry businessmanagementwiththerelationshipoflocalinfluential people in an acceptable level” (Reading of the Environment Dimension).

Thethreescalesusedinthisresearchwereclassified accord-ing tothe Likert scaleof 7 points, inwhich1 means totally disagreeand7totallyagreeor,notadaptedandverywelladapted inthecaseofthecross-culturaladaptationscale.The hypothe-sesweretestedbymeansofastructuralequationsanalysis,with partialleastsquaresestimation.Thestructuralequations anal-ysisisastatisticaltechniquethathasrecurrentlybeenusedin researchinfieldssuchas:Moreiraetal.(2012);LeeandSukoco (2010);Shihetal.(2010)andKraimeretal.(2001).

Datacollection

establishedwiththeHumanResourcesdepartmentof53 com-panies inBrazil that perform expatriations,blogs, and social networks about expatriates in the country; participants also indicated other organizational expatriates who could partici-pateinthesurvey.Thissamplingtechnique,knownassnowball (Heckathorn, 1997), has been used previouslyin the area of expatriationstudies(e.g.,Peltokorpi&Froese,2009).

Thefirststageofcollectionoccurredbysendingthe523 invi-tationstotheobtainedemailslist.Onthe13thday,aftertheinitial communication,anintermediatenoticewassentandthe collec-tionwasclosedonthe18thdayafterthebeginningofthedata collection.Atotalof217questionnaireswerecollected, there-foreobtaininga41.5%return.Noresponsewasinvalidatednor presentedanymissingvalues.

Thedatawereobtainedfromtheexpatriates’self-assessment whentheyansweredthequestionnaires.Regardingthepossible occurrenceof biased answers,it isworth noting that quanti-tativeevaluationof such aconstructis not aneasy task,due to the subjective variables involved, and the lack of a stan-dardized instrument that eliminates the biasof the degreeof demand ofeach respondent, whetherit isthe manager orthe actualexpatriate.

Inthecaseofthisresearch,thechoicefortheself-assessment isgivenbytheprofileofthediversifiedsample,preventingfrom obtainingperformancedatafromtheresponsesoftheirmanagers and/orpeers. The useof theself-assessmentscale for perfor-mance,evenifitisself-perceivedperformance,hasbeenadopted inliteratureasinthecaseofresearchdevelopedbyCaligiuriand Tung(1999),Ramaluetal.(2011,2012),Roseetal.(2010)and

LeeandSukoco(2010).

Resultsanddiscussion

Thehypothesizedrelationswereanalyzedthroughstructural equations modeling(SEM), withpartial leastsquares estima-tionandtheSmartPLS2.0M3software(Ringle,Wende,&Will, 2005).The decisiontousethe methodisduetothe factthat itallowstheuseoflatentvariables;estimatingsimultaneously therelationshipbetweenindicatorsandlatentvariables (mea-surementmodel),andtherelationshipsbetweenlatentvariables (structural model); and treating data with non-normal distri-bution (HairJunior etal., 2005).This statistical technique is adoptedrepeatedlyinresearchinthisfieldsuchasbyMoreira etal.(2012), Lee andSukoco(2010),Shih etal. (2010)and

Kraimeretal.(2001).

Fortheidentificationofdataoutliers,weadoptedthe elim-inationcriterionfor thoserespondentswhopresented 77%of equalanswers(ESSEDUNET,2009).Therewasnoelimination duetooutliersormissingvalues.

Theresultsanalysisfollowedwiththemodelmeasurement evaluationandthestructuralmodelevaluation.

Measurementmodelevaluation

The evaluationof the measurementmodel was performed throughaconfirmatoryfactoranalysis(alllatentvariableswere linkedtoeachotherwithfactorweightingschemeestimation).

In this analysis, we observed that the Adaptation to Interac-tion andthe General Adaptation didnot presentdiscriminant validityamongthemselves.Inaddition,someitemswerehighly cross-loadedwithotherconstructs,whichpreventedthe achieve-ment of satisfactory model fit indices. Thus, we performed consecutive roundsofexclusionof assertions,until wefound acompositionthatofferedabetteradaptationtothemodel.In thisprocess,weexcludedfromthe modelthe variablesGG6, IA1,IA2,MCOG2,PM2,PRE2andPP2.

Thequalityofthestructuralmodelwasperformedusingthe

Q2testbyStone-Geisserinordertoevaluateitspredictive rel-evance (HairJunior, Hult, Ringle,&Sarstedt, 2014,p. 167). In thisanalysis, to testthe stability of the results,two sepa-rateanalyzeswith7and25omissiondistanceswereperformed (blindfoldingtechniqueperformedonSmartPLS).Asthevalues werestableinbothconfigurationsandtheQ2swerepositive,we caninfer thatthe modelwasstableandthat therequirements ofpredictiverelevanceweresatisfied.Theoptiontonotinclude goodness-of-fitasacriterionforevaluatingthemeasureof qual-ityofthemodelwasbasedontherecommendationofauthors suchasHairJunioretal.(2014,p.185)andHenselerandSarstedt (2013,p.577).

Subsequently,wealsoperformedanevaluationofthe mea-surement model based on the following criteria: convergent validity, discriminant validity, andreliability. The convergent validity evaluates the relationshipbetween the measurements of the sameconstructandisestimated, inthisresearch,from the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which identifies the general amount of variance in the indicators explained by the construct. The high degree of convergent validity indi-catesthatthemeasuresarecorrelatedandtheconceptualization adoptedisadequate(HairJunioretal.,2005).Weobservedin the results, that allfirst-orderlatent variablespresented aver-age variance extracted with value exceeding 50%, reaching the criteria proposed by Chin (1998) and Hair Junior et al. (2005),asshowninTable3.Inrelationtosecond-orderlatent variables, the same criteria were also achieved, as shownin

Table4.

In studiesdevelopedbystructural equations,thereliability evaluation of the constructmust be performed bycomposite reliability, withthisbeing a measureof internal consistency betweentheindicators.TheresultspresentedinTables3and4

meetthe criterionofvaluehigherthan0.7suggestedbyChin (1998),Henseler,Ringle,andSinkovics(2009)andTenenhaus, Vinzi,Chatelin,andLauro(2005).

Asthelastmeasureofevaluationofthemeasurementmodel weanalyzedthediscriminantvalidity,thatverifiestowhatextent thescalesmeasurewhatithasproposedtomeasure,examining the correlation betweenthe constructs andthe factorloading of theindicatorsinrelationtotheirrespectiveconstruct(Hair Junior etal.,2005).Thus,weverified that theassertions pre-sentedhigherfactorloadingsintheirrespectiveconstructsthan inanyother,whichconstitutestheoccurrenceofdiscriminant validity.Allindicatorspresentedthischaracteristic,asshownin

Table5.

Table3

Pearson’scorrelationanddescriptivestatisticsof1storderlatentvariables.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1.Generaladaptation 0.78

2.Workadaptation 0.33 0.77

3.CognitiveCI 0.24 0.66 0.86

4.BehavioralCI −0.04 0.05 0.05 0.93

5.MetacognitiveCI 0.33 0.51 0.70 0.05 0.87

6.MotivationalCI 0.09 0.12 0.14 0.46 0.09 0.88

7.Performance:management 0.63 0.39 0.29 0.00 0.31 0.2 0.80

8.Performance:readingtheenvironment 0.70 0.50 0.34 0.01 0.31 0.09 0.63 0.75

9.Performance:production 0.72 0.51 0.33 −0.02 0.35 0.03 0.62 0.70 0.83

Mean 2.69 2.75 2.79 3.33 3.05 3.73 3.61 3.18 2.71

Median 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 4.00 4.00 3.00 3.00

Standarddeviation 0.96 0.82 1.18 1.24 1.22 1.05 0.83 0.78 0.77

Averagevarianceextracted 0.61 0.59 0.73 0.86 0.76 0.78 0.64 0.56 0.68

Compoundreliability 0.88 0.81 0.94 0.97 0.91 0.95 0.78 0.79 0.81

Notea:Thesquarerootvaluesoftheaveragevarianceextractedareinbold(diagonal).

Noteb:StandardizedfactorscoresobtainedintheestimationofthemodelwiththeSmartPLS2.0M3software(Ringleetal.,2005).

werelowerthanthe squarerootof theAVE(which indicates thattheassertionsrelatemorestronglytotheirfactorsthanto theothers).AsshowninTables3and4,thesecriteriawerealso met.

EvaluationofthestructuralMODEL

TheStructuralModelAssessmentispresentedintwostages: evaluationof theeffect ofcontrol variablesandthe hypothe-sestest.Table6presentsthe resultsof twostructuralmodels, estimated to verify the effects of control variables (previous experience in expatriation, gender and time in Brazil). The justificationsfor the choicesof thesevariablesareduetothe followingfacts:

Previousexperienceinexpatriation:sincelearningin dif-ferentcontextsofexpatriationcanhelpexecutivesdevelopbetter performance strategies and a greater global business vision (Moonetal.,2012),itispossiblethatthisvariableaffectsthe performanceinexpatriation

Table4

Pearson’scorrelationanddescriptivestatisticsof2ndorderlatentvariables.

Secondorderlatentvariables 1 2 3

1.Adaptation 0.81

2.Culturalintelligence 0.39 0.67

3.Performance 0.73 0.37 0.88

Mean 2.69 3.17 3.21

Median 3.00 3.00 3.00

Standarddeviation 0.93 0.86 1.22

Averagevarianceextracted 0.65 0.54 0.77 Compositereliability 0.78 0.75 0.88

Notea:Thesquarerootvaluesoftheaveragevarianceextractedareinbold (diagonal).

Noteb:Standardizedfactorscoresobtainedintheestimationofthemodelwith theSmartPLS2.0M3software(Ringleetal.,2005).

Gender:thereisearlierevidencethatwomen,astheyhave agreaterabilitytobuildrelationships,wouldhavegreaterease adjusting tolife abroad(Cole &McNulty, 2011;Haslberger, 2010) and, as aresult of this, it is possible that such differ-encetranslatesintoabetterfemaleperformanceininternational assignments.

TimeinBrazil:thetimeinthehostcountrymaybe associ-atedwithaperformanceimprovement,giventhatastimepasses, theindividualtendstodeallesswithissuesofdiscomfortdueto theinitialstrangenessinthecountryoforiginandthus,onecan devotethemselvesmoreintenselytotheassignmentitself(Cole &McNulty,2011).Inaddition,thereisevidencethattimein thehostcountrycanimproveperformanceduetothepossibility ofbetteradaptingtothechallengesofthelocalcontextof the internationalassignment(Haslberger,2010).

InModel1,inwhichonlytherelationshipbetweenthe con-trol variablesandthe dependent variable“Performance” was evaluated,weobservedanon-significanteffectinthe depend-ent variable (inall threecases, p>0.05), withan R2 of only 0.6%.InModel2,inwhichtheothervariablescontainedinthe model wereincluded (Cross-culturalAdaptation andCultural Intelligence), the control variables remained without signif-icant relationships with the Performance (in all three cases,

p>0.05). Thus, by isolating the effects of control variables, greater robustnessandcredibility are assuredtothe hypothe-sistestperformedinthesequence.Wedidnotnoticeproblems ofmulticollinearityinanyofthemodels,sincetheVIF (Vari-anceInflatedFactor)presentedaslowerthan5(HairJunioretal., 2005).

Table5

Matrixofcrossloads.

1 2 3 4 8 9 5 6 7

1.Generaladaptation

GA 1 0.73 0.27 0.18 0.04 0.52 0.51 0.26 0.09 0.48

GA 2 0.81 0.15 0.07 −0.09 0.57 0.56 0.1808 0.05 0.52

GA3 0.85 0.19 0.12 −0.02 0.61 0.58 0.2255 0.03 0.48

GA4 0.76 0.28 0.20 −0.06 0.53 0.55 0.2647 0.03 0.49

GA5 0.72 0.39 0.35 −0.03 0.51 0.57 0.3502 0.12 0.52

2.Workadaptation

WA1 0.27 0.82 0.56 0.02 0.39 0.41 0.47 0.11 0.29

WA2 0.20 0.85 0.64 0.06 0.42 0.40 0.45 0.07 0.32

WA3 0.32 0.61 0.27 0.03 0.36 0.38 0.20 0.09 0.28

3.Cognitiveculturalintelligence

COG1 0.28 0.53 0.82 0.04 0.32 0.31 0.62 0.14 0.27

COG2 0.20 0.64 0.84 0.02 0.35 0.31 0.54 0.12 0.25

COG3 0.21 0.55 0.90 0.03 0.29 0.30 0.61 0.08 0.27

COG4 0.19 0.53 0.85 0.01 0.26 0.27 0.58 0.12 0.22

COG5 0.16 0.59 0.85 0.09 0.28 0.25 0.60 0.12 0.21

COG 6 0.19 0.55 0.87 0.08 0.24 0.28 0.64 0.12 0.26

4.Behavioralculturalintelligence

BEHA1 −0.02 0.09 0.07 0.94 0.02 0.01 0.06 0.50 0.02

BEHA2 −0.03 0.06 0.06 0.92 0.02 −0.02 0.05 0.37 0.00

BEHA3 −0.07 0.06 0.04 0.93 0.01 −0.01 0.03 0.42 −0.01

BEHA4 −0.08 −0.01 0.01 0.93 −0.02 −0.10 −0.01 0.42 −0.03

BEHA5 0.01 0.03 0.05 0.93 0.02 0.02 0.08 0.41 0.04

5.Metacognitiveculturalintelligence

MCOG1 0.31 0.48 0.62 0.04 0.31 0.34 0.90 0.07 0.29

MCOG3 0.33 0.40 0.59 0.08 0.28 0.33 0.88 0.12 0.28

MCOG4 0.24 0.44 0.63 −0.01 0.22 0.24 0.84 0.03 0.24

6.Motivationalculturalintelligence

MOT1 0.07 0.10 0.15 0.39 0.10 0.02 0.09 0.91 0.20

MOT2 0.06 0.11 0.13 0.43 0.04 0.02 0.09 0.90 0.14

MOT3 0.06 0.06 0.07 0.40 0.05 −0.02 0.04 0.85 0.14

MOT4 0.12 0.10 0.10 0.42 0.07 0.06 0.06 0.87 0.20

MOT5 0.06 0.14 0.15 0.37 0.12 0.05 0.09 0.88 0.17

7.Performance:management

PM1 0.49 0.32 0.23 0.03 0.50 0.42 0.22 0.21 0.78

PM3 0.52 0.30 0.24 −0.02 0.51 0.57 0.28 0.11 0.82

8.Performance:readingtheenvironment

PRE1 0.50 0.41 0.31 0.12 0.79 0.51 0.24 0.10 0.49

PRE3 0.56 0.34 0.25 −0.05 0.74 0.53 0.22 0.06 0.49

PRE4 0.52 0.39 0.21 −0.04 0.72 0.53 0.24 0.04 0.43

9.Performance:production

PP1 0.59 0.47 0.28 0.01 0.55 0.82 0.26 0.02 0.45

PP3 0.59 0.37 0.27 −0.05 0.61 0.84 0.32 0.03 0.57

Note1:Table5isrestrictedtopresentingthelatentvariablesoffirstorder(LV)andtheabbreviationsforeachassertion.

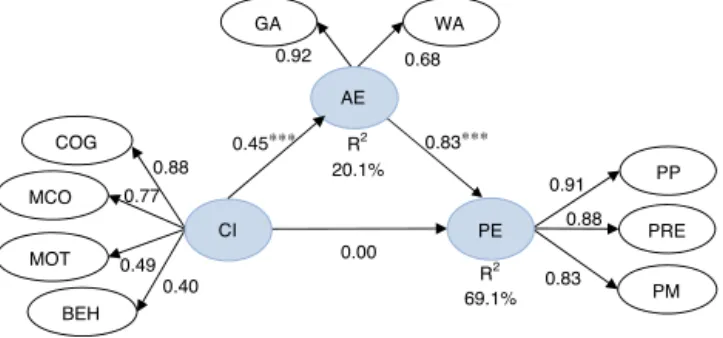

Evidenceleadstonon-rejectionofHypothesis1,whichdeals with the association between culturalintelligence and cross-cultural adaptation, since the paths coefficient between both factorswas0.45(p<0.001),andthecoefficientof determina-tion(R2)of 20.1%;thismeans that20.1%of thevariationin theexpatriatescross-culturaladaptationwasassociatedwiththe degreeofculturalintelligence.Theseresultsaresimilartothose byAngetal.(2007)andRamaluetal.(2011).

Therelationshipbetweenculturalintelligenceandexpatriate performancetreatedinHypothesis 2was rejected,presenting

a paths coefficient between the two variables of 0.00 (no-significant).ThisresultisinlinewiththosefoundbyLeeand Sukoco(2010),whointheirresearchobtainedapathscoefficient of0.18(non-significant).

Table6

Structuralmodelspredictorsofexpatriatesperformance.

Structuralcoefficient Standarderror t-value p-value VIF R2 R2adjusted

Model1(controls)

Previous experience→performance 0.049 0.065 0.749 0.454 1.1

Femalegender→performance 0.046 0.071 0.646 0.518 1.0 0.6% 0.0%

TimeinBrazil→performance −0.032 0.067 0.469 0.639 1.0

Model2(complete)

Previousexperience→performance 0.009 0.039 0.235 0.815 1.02

Femalegender→performance 0.060 0.040 1507 0.132 1.01

TimeinBrazil→performance −0.054 0.039 1370 0.171 1.01 69.8% 69.1%

Inteligênciacultural→performance −0.003 0.044 0.058 0.954 1.27

Cross-culturaladaptation→performance 0.834 0.033 25,516 0.000 1.26

Culturalintelligence→cross-culturaladaptation 0.448 0.070 6435 0.000 1.00 20.1% 19.7%

Source:Elaboratedbytheauthorsfromtheresearchdata.

Note1:ThestructuralmodelswereestimatedbytheSmartPLS3.2.0software.

Note2:TheVIF(varianceinflationfactor)wasestimatedusingtheSPSSsoftwarefromthefactorialscores.

by Ramalu, Rose, Kumar, and Uli (2010) and Wu and Ang (2011).However,unlike previousstudies,thisadds tothe lit-eraturebyincluding,inastructuralmodel,culturalintelligence asanantecedentofcross-culturaladaptationfromastudywith asamplecomposedofexpatriatesfromdifferentcontinents.

Theindirecteffectofculturalintelligenceonexpatriate per-formance via cross-cultural adaptation was 0.37 (0.83*0.45), whichmeansthat thismediationexplained13.7%of thetotal expatriate performance;this effect was also identified in the study by Lee andSukoco (2010) whichinvestigated expatri-atesfromAsiancountries(China,VietnamandotherSoutheast Asiancountries),operatinginmultinationalsinTaiwan.

However,theauthorsfoundamediationof44.1%.The differ-enceofthisresultcomparedtotheoneobtainedinthisresearch, atthesametimethatitreinforcesthefactthatculturaldifferences mediated the effect of cultural intelligence on cross-cultural adaptationandexpatriateperformance(Earley&Ang, 2003),

GA WA

PP COG

MCO

MOT

PRE

PM BEH

0.45∗∗∗ R2 0.83∗∗∗

R2 20.1%

69.1% 0.00

0.92 0.68

0.40 0.49

0.77 0.88

0.83 0.91

0.88 AE

CI PE

Fig.1.StructuralandMeasurementModel.

Note: Weused theSmartPLS 2.0.M3software (Ringle etal., 2005). The coefficientsareinthestandardizedformandaresignificant(p<0.01), Signif-icancewasestimatedwithn=217and1000repetitions,byusingbootstrap. ResultsoftheSMARTPLS:***p<0.001.

CI, Cultural Intelligence; COG, Cognitive Cultural Intelligence; MCOG, MetacognitiveCulturalIntelligence;MOT,MotivationalCulturalIntelligence; BEHA,BehavioralCulturalIntelligence;AE,AdaptationoftheExpatriate;GA, GeneralAdaptation;IA,InteractionAdaptation;WA,WorkAdaptation;PER, Performance;PP,ProductionPerformance;PRE,PerformanceinReadingthe Environment;PM,PerformanceinLocalEmployeeManagement.

alsoconfirmstheexistenceofthiseffectofculturalintelligence ontheexpatriateperformancethroughcross-culturaladaptation. Thenatureoftherelationshipbetweenculturalintelligence andexpatriateperformanceis indirect, beingmediatedin the modelstudied,bycross-culturaladaptation.Thisresultcanbe interpretedinthesensethatthesimplefactthatanindividual pos-sessesahighdegreeofculturalintelligencedoesnotguarantee, byitself,ahighprobabilitythatonewillperformsatisfactorily. Forthisrelationshiptooccur, it is necessaryfor thiscultural intelligencetobecomeabettercross-culturaladaptation.This, inturn,tendstoinfluenceabetterperformance.

TheContactTheorysupportssuchmediationinviewofthe fact that,thegreater thenumberofpositiveinteractionof the expatriatewiththelocalinhabitants,infrequencyanddiversity ofpeople,thelesserwillbethepsychologicalstressand cogni-tivefatigue,generatedbytheprejudices,theuncertaintiesand theambiguityofthenewculturalenvironment;andthegreater willbetheopportunitiesforinformallearningaboutthe intrin-siccharacteristicsofthenewcultureandforthedevelopment ofnewfriendships(Erasmus,2010;Novaketal.,2011;Toit& Quayle,2011).Suchaprepositionisreinforcedbytheideathat closeinterpersonalrelationshipscontributetothewell-beingof individuals(Britto&Oliveira,2016; Novaketal., 2011),and consequentlyforpsychologicalcomfort(adaptation).

Thus,thepositiveinteractionswiththelocalinhabitantsallow theexpatriatetoknowthenewculturebetter,contributetothe adaptationandenhancetheabilitiesinherentincultural intelli-gence(learning,understandingandknowinghowtoadapttheir knowledge andattitude inthe situation of culturaldiversity), allowingtheindividualtodealadequatelywithstress,achieving betterlevelsofadaptationand,consequently,performingtheir workwithmoreenergyandfocus,whichcanpositivelyimpact theirperformance.

Conclusion

adaptationreinforcetheimportanceofadjustingtheexpatriate tothecultureofthehostcountryforthesuccessininternational assignments. The study adds knowledge to the expatriation literature by including, in a structural model, cultural intel-ligence as an antecedent of cross-cultural adaptation from a study witha sample of expatriatesoriginating fromdifferent continents.

The direct relationship between cultural intelligence and expatriateperformancewasnonsignificant,similartothatfound inthestudybyLeeandSukoco(2010).However,becausethis study hasobtained such resultsinamore diversifiedsample, whoseexpatriatesoriginatefromfivedifferentcontinents,itis understood that thisresearchoffers an advanceinthe degree ofrobustnessreferringtothestudyoftherelationshipbetween theseconstructs.

Anotherrelevant resultfoundinthisresearchreferstothe indirectrelationshipbetweenculturalintelligenceandexpatriate performancemediatedbycross-culturaladaptation,reinforcing theargumentthatculturalintelligenceisanimportantantecedent tothesuccessoftheassignment.Thisresultunderscorestheneed toconvertthepotentialofculturalintelligenceintoacapacity forbetteradaptationoftheexpatriatetothenewculture.Inthis research,weconclude,supportedbytheContact Theory,that theprocessof transformingculturalintelligenceinto adaptive abilityisfacilitatedandenhancedby thepositiveinteractions establishedwiththelocalinhabitants.

Themainlimitationsofthisstudyareduetotherestriction ofresearchinjustthreevariables,culturalintelligence, cross-culturaladaptationandexpatriatesperformance,sincethetheme ifofgreatcomplexity.Anotheraspectistheoptionforthe self-evaluationof theperformanceconstruct,suchchoicewasdue tothe reality of the sample and, although thisprocedure has supportinthe literature,we considerthat thisprocessallows theexistenceof abiasofthe respondent,andmayimpactthe resultsof theresearch.Itisworthmentioningthatthe factof thisstudy having across-sectional design andevaluatingthe opinionofexpatriatesatagivenmomentintime,makes assess-ments of proposed relationships representa limitation of the study.

Asitisastudyofhumanbehavior,thesubjectivitythatmakes upalltheestablishedrelationshipsof theindividualraisesthe complexityoftheresearchinthesocialfield.Thus,researchon expatriates,thatinitiallydedicatedtoinvestigatetwovariables, isincreasingitscomplexityincludingnewvariablestostudies,as inthisone.Thistrendshouldremaininordertobetterunderstand the factors impacting on the individual who is on a mission overseas.

Giventhelimitationspointedout,wesuggestfutureresearch tobroadentheresearchonthefactorsthatinfluencethe perfor-manceoftheexpatriate,includingalargernumberofvariables tobestudied,such asindividualcharacteristics (e.g.,previous internationalexperience,languageabilityandpersonality)and atamacrolevel,culturaldistance.Anothersuggestionistotake otherformsofevaluatingtheexpatriate’sperformance,suchas self-assessment,suggestedbyShayandBaack(2006),inwhich the individual compares their performancewith that of their peers.

Also,asarecommendationforfutureresearch,wesuggest theevaluationofwhatexplainsthedevelopmentofcultural intel-ligence of expatriates. There is in the literature a discussion regardingtheinnateoracquirednatureofculturalintelligence (Angetal.,2004;Lee &Sukoco, 2010).Ifit isacquired,the topicbecomesofgreatimportanceforcompanieswith interna-tionalmobilityprograms,sinceitcanbedeveloped.Therefore, we suggest that the relationship between this type of intel-ligence and some possible antecedents, such as personality, personal values or previous international experience also be tested.

As practical suggestions for managers of International Human Resources, we understand that it is not enough for companiestoselectindividualsmoreculturallyintelligentfor internationalpositions,itisnecessarytosupporttheadaptation oftheseexpatriates,inordertofacilitatetheindirectinfluenceof culturalintelligenceonperformance,viacross-cultural adapta-tion,forexample,bypromotingdirect,prolongedorimaginative contactexperience,intheprocessofpreparingtheexpatriate.

We also suggest, that organizations use the CQS, since it presented satisfactory psychometric properties to measure, periodically,theculturalintelligenceof professionalswhoare candidatesforinternationalmobility,providingcompanieswith additional informationabout candidates.In thiscase, we rec-ommendthattheevaluationofthemembersoftheorganization be performed from the responses of superiors, subordinates and/or clients with whom they interact in a cross-cultural context.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

Allport,G.W.(1954).Thenatureofprejudice.Reading,MA:Addison-Wesley. AngS.,Dyne,L.V., KohC.,&Ng,K.Y.(2004).Themeasurementof cul-turalintelligence.PaperpresentedattheAcademyofManagementMeetings SymposiumonCulturalIntelligenceinthe21stCentury,NewOrleans,LA. Ang,S.,Dyne,L.V.,Koh,C.,Ng,K.Y.,Templer,K.J.,Tay,C.,etal.(2007). Culturalintelligence:Itsmeasurementandeffectsonculturaljudgmentand decisionmaking.CulturalAdaptation,andTaskPerformance.Management andOrganizationReview,3(3),335–371.

Araujo,B.F.,Von,B.,Broseghini,N.,&Custodio,A.F.(2013).Suporte orga-nizacionaleadaptac¸ãodecônjugeseexpatriados:Umaanálisepormeiode equac¸õesestruturais.RevistaGestão&Tecnologia,13(3),51–76. Araujo,B.F.V.B.,Teixeira,M.L.M.,daCruz,P.B.,&Malini,E.(2012).

Adaptac¸ãodeexpatriadosorganizacionaisevoluntários:Similaridadese diferenc¸asnocontextobrasileiro.RevistadeAdministra¸cãodaUniversidade deSãoPaulo,47(4),555–570.

Black,J.S.(1988).Workroletransitions:AstudyofAmericanexpatriate man-agersinJapan.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies.,19(2),277–294. Black,J.S.,Gregersen,H.B.,&Mendenhall,M.E.(1992).Globalassignments.

SanFrancisco:Jossey-Bass.

Black,J.S.,Mendenhall,M.,&Oddou,G.T.(1991).Acomprehensivemodelof internationaladjustment:Anintegrationofmultipletheoreticalperspectives. AcademyofManagementJournal,16(2),291–317.

Black,J.S.,&Stephens,G.K.(1989).TheinfluenceofthespouseonAmerican expatriateadjustmentandintenttostayinPacificRimoverseasassignments. JournalofManagement,15(1),529–544.

Brito,R.P.,&Oliveira,L.B.(2016).Therelationshipbetweenhumanresource managementandorganizationalperformance.BrazilianBusinessReview, 13(3),90–110.

BrookfieldGlobalRelocationServicesBGRS.(2012).Globalrelocationtrends: 2012surveyreport.NewYork:WindhamInternational.

Caligiuri,P.M.,&Tung,R.L.(1999).Comparingthesuccessofmaleand femaleexpatriatesfromaUS-basedmultinationalcompany.The Interna-tionalJournalofHumanResourceManagement,10(5),763–782. Cheng,H.L.,&Lin,Y.Y.(2009).Doasthelargeenterprisesdo?Expatriate

selectionandoverseasperformanceinemergingmarkets:ThecaseofTaiwan SMEs.InternationalBusinessReview,18(1),60–75.

Chin,W.W.(1998).ThePartialLeastSquaresapproachtostructuralequation modeling.InG.A.Marcoulides(Ed.),Modernmethodsforbusinessresearch (pp.295–336).USA:LawrenceErlbaumAssociates.

Cole,N., & McNulty, Y. (2011). Why do femaleexpatriates “fit-in” bet-ter than males? An analysis of self-transcendence and socio-cultural adjustment.CrossCulturalManagement:AnInternationalJournal,18(2), 144–164.

Cota,M.S.G.,Emmendoerfer, M.L., Reis,A.C. G.,& daSilva, L. L. (2015).ProcessodeAdaptac¸ãodeExecutivosExpatriadosnoBrasil:Um EstudoSobreaAtuac¸ãodoProfissionaldeSecretariadoExecutivoemuma MultinacionaldeOrigemAlemã.RevistadeGestãoeSecretariado,6(1), 74–98.

Earley,P.C.,&Ang,S.(2003).Culturalintelligence:Individualinteractions acrosscultures.PaloAlto,Calif:StanfordUniversityPress.

Earley,P.C.,Ang,S.,&Tan,J.S.(2006).CQ:Developingculturalintelligence atwork.California:StanfordUniversityPress.

Earley,P.C.,&Peterson,R.S.(2004).Theelusiveculturalchameleon: Cul-turalintelligenceasanewapproachtointerculturaltrainingfortheglobal manager.AcademyofManagementLearningandEducation,3(1),100–115. Erasmus,Z.(2010).Contacttheory:Tootimidforraceandracism.Journalof

SocialIssues,66(2),387–400.

EssEdunet.(2009).Recuperadoem10dez.2011.http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/ Forster,N.,&Johnson,M.(1996).ExpatriatemanagementpoliciesinUK

com-paniesnewtotheinternationalscene.TheInternationalJournalofHuman ResourceManagement,7(1),177–205.

HairJunior,J.F.,Anderson,R.E.,Tatham,R.L.,&Black,W.C.(2005).Análise multivariadadedados(5.ed).PortoAlegre:Bookman.

HairJunior,J.F.,Hult,G.T.M.,Ringle,C.M.,&Sarstedt,M.(2014).A primeronpartialleastsquaresstructuralequationmodeling(PLS-SEM). NewYork:Sage.

Haslberger,A.(2010).Genderdifferencesinexpatriateadjustment.European JournalofInternationalManagement,4(1),163–183.

Heckathorn,D.D.(1997).Respondent-drivensampling:Anewapproachtothe studyofhiddenpopulations.SocialProblems,44(2),174–199.

Henseler,J.,&Sarstedt,M.(2013).Goodness-of-fitindicesforpartialleast squarespathmodeling.ComputationalStatistics,28(2),565–580. Henseler,J.,Ringle,C.,&Sinkovics,R.(2009).Theuseofpartialleastsquares

pathmodelingininternationalmarketing.AdvancesinInternational Mar-keting,20(1),277–320.

Jenkis,E.M.,&Mockaitis,A.I.(2010).You’refromwhere?Theinfluenceof distancefactorsonNewZealandexpatriates’cross-culturaladjustment.The InternationalJournalofHumanResourceManagement,12(15),2694–2715. Kim,J.(2012).Exploringtheexperienceofintergroupcontactandthevalueof recreationactivitiesinfacilitatingpositiveintergroupinteractionsof immi-grants.LeisureSciences,34(1),72–87.

Kraimer,M.L.,Wayne,S.J.,&Jaworski,R.A.(2001).Sourcesofsupport andexpatriateperformance:Themediatingroleofexpatriateadjustment. PersonnelPsychology,54(1),71–99.

Kubo,E.K.M.,&Braga,B.M.(2013).Ajustamentointerculturaldeexecutivos japonesesexpatriadosnobrasil:Umestudoempírico/intercultural.Revista deAdministra¸cãodeEmpresas,53(3),243.

Kumar,N.,Rose,R.C.,Ramalu,&Sri,S.(2008).Theeffectsofpersonality andculturalintelligenceoninternationalassignmenteffectiveness:Areview. JournalofSocialSciences,4(4),320–328.

Lee,L.,&Sukoco,B.M.(2010).Theeffectsofculturalintelligenceonexpatriate performance:Moderatingeffectsofinternationalexperience.The Interna-tionalJournalofHumanResourceManagement,21(7),963–981. Lee,L.,&VanVorst,D.(2010).Theinfluencesofsocialcapitalandsocial

sup-portonexpatriates’culturaladjustment:AnempiricalvalidationinTaiwan. InternationalJournalofManagement,27(3),628–649.

Moon,H.K.,KwonChoi,B.,&ShikJung,J.(2012).Previousinternational experience,cross-culturaltraining,andexpatriates’cross-cultural adjust-ment:Effectsofculturalintelligenceandgoalorientation.HumanResource DevelopmentQuarterly,23(3),285–330.

Moreira,L.M.C.,de,O.,Bilsky,W.,&Araujo,B.F.V.B.(2012).Valores pes-soaiscomoantecedentesdaadaptac¸ãotransculturaldeexpatriados.Revista deAdministra¸cãoMackenzie,13(3),69–95.

Novak,J.,Kelsey,K.J.,&Christensen,K.A.(2011).Applicationofintergroup contacttheorytotheintegratedworkplace:Settingthestageforinclusion. JournalofVocationalRehabilitation,35,211–226.

Peltokorpi,V.,&Froese,F.(2009).Organizationalexpatriatesandself-initiated expatriates:WhoadjustsbettertoworkandlifeinJapan?TheInternational JournalofHumanResourceManagement,20(5),1096–1112.

Pettigrew,T.F.(1998).Intergroupcontacttheory.AnnualReviewsPsychology, 49,65–85.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of inter-groupcontacttheory.JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,90(5), 751–783.

Ramalu,S.S.,Rose,C.R.,Uli,N.,&Kumar,N.(2012).Culturalintelligence andexpatriateperformanceinglobalassignment:Themediatingroleof adjustment.InternationalJournalofBusinessandSociety,13(1),19–32. Ramalu,S.S.,Rose,R.C.,Kumar,N.,&Uli,J.(2010).Personalityandexpatriate

performance:Themediatingroleofexpatriateadjustment.TheJournalof AppliedBusinessResearch,26(6),113–122.

RamaluSri,S.R.,Wei,C.C.,&Rose,R.C.(2011).Theeffectsofcultural intelli-genceoncross-culturaladjustmentandjobperformanceamongstexpatriates inMalaysia.InternationalJournalofBusinessandSocialScience,2(9), 59–71.

Richeson,J.A.,&Shelton,J.N.(2003).Whenprejudicedoesnotpayeffects ofinterracialcontactonexecutivefunction.PsychologicalScience,14(3), 287–290.

Rosal,A.S.R.(2015).GestãodeRecursosHumanosInternacionaleo Ajus-tamentoInterculturaldoExecutivoExpatriado.PsicologiaRevista.Revista daFaculdadedeCiênciasHumanasedaSaúde,24(1),121–214. Rose,R.C.,Ramalu,S.S.,Uli,J.,&Kumar,N.(2010).Expatriateperformance

ininternationalassignmentstheroleofculturalintelligenceasdynamic inter-culturalcompetency.InternationalJournalofBusinessandManagement, 5(8),76–85.

Ringle,C.M.,Wende,S.,&Will,A.(2005).SmartPLS2.0.(beta).

Schuler,R.S.,Fulkerson,J.R.,&Dowling,P. J.(1991).Strategic perfor-mancemeasurementandmanagementinmultinationalcorporations.Human ResourceManagement,30(3),365–392.

Shay,S.,&Baack,S.(2006).Anempiricalinvestigationoftherelationships betweenmodesanddegreeofexpatriateadjustmentandmultiplemeasures ofperformance.InternationalJournalofCrossCulturalManagement,6(3), 275–294.

Shih,H.A.,Chiang,Y.H.,&Hsu, C.C.(2010).Highinvolvementwork system,work–familyconflict,andexpatriateperformance–examining Tai-waneseexpatriatesinChina.TheInternationalJournalofHumanResource Management,21(11),2013–2030.

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS pathmodeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205.

Triandis,H.C.(2006).Culturalintelligenceinorganizations.Groupand Orga-nizationManagement,31(1),20–26.

ToitDu,M.,&Quayle,M.(2011).Multiracialfamiliesandcontacttheoryin SouthAfrica,doesdirectandextendedcontactfacilitatedbymultiracial familiespredictreducedprejudice.SouthAfricanJournalofPsychology, 41(4),540–551.

Turner,R.N.,&Crisp,R.J.(2010).Imaginingintergroupcontactreduces implicitprejudice.BritishJournalofSocialPsychology,49(1),129–142. Turner,R.N.,Crisp,R.J.,&Lambert,E.(2007).Imaginingintergroupcontact

canimproveintergroupattitudes.GroupProcesses&IntergroupRelations, 10(4),427–441.