A Work Project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master’s Degree in

Management from the Faculdade de Economia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

National Meta-Stereotyping in the Wake of the

Euro Crisis:

A Two Cluster Analysis of Adjustment, Meeting Satisfaction and

Altruistic OCB in the European Institutions of Brussels

Julia Charlotte Reichert

3034

A Project carried out with the supervision of:

2

Abstract

The present study investigated national meta-stereotypes discussed in terms of social

categorization processes and its relationship to adjustment, meeting satisfaction and altruistic

OCB behaviour within the European Institutions. A study among European officials was

conducted to firstly investigate content patterns of meta-stereotypes of two diverging cultural

clusters. This demonstrated that the Latin Europe cluster depicted paternalistic

meta-stereotypes, while the Germanic cluster illustrated envious meta-meta-stereotypes, which was

derived from the content dimensions warmth and competence. The study argues that this can

partly be ascribed to the recent Euro crisis. Secondly, the non-stereotypical dimension of each

cluster predicted adjustment to the other group, respectively. Adjustment in turn, mediated the

relationship between stereotypes and altruistic OCB behaviour. Future studies on

meta-stereotype should examine the factors leading to the adjustment to the outgroup.

3

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 4

Literature Review ... 6

Hypotheses ... 9

Paternalistic and Envious Meta-Stereotypes ... 9

Meta-Stereotypes, Meeting Satisfaction, Adjustment and Altruism ... 11

Methodology ... 14

Sample and Procedure ... 14

Measures ... 16

Results... 17

Discussion ... 20

Practical Implications for Organizations ... 25

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research ... 26

Conclusion ... 27

References ... 27

Appendix ... 30

4

Introduction

The recurrent emergence of stereotypes against groups and its respective far-reaching

implications for society are illustrated by current and past events. At present for instance,

Muslims are heavily stereotyped and prejudiced, given the observed frequency of terror attacks

from Islamic extremists’ groups. Consequently, a seemingly one-size-fits-all mentality is displayed to this religious group, implying the assumption that all Muslims must be terrorists.

One might come to the conclusion that society did not learn from its past mistakes. Throughout

history have religious, social or racial groups been stereotyped and prejudiced and thus been

segregated, oppressed or even slaughtered. Also the recent Euro crisis and thereof resulting

fears have left its marks, such as labelling countries, which were more affected by the crisis as

“lazy”. The apparent gap of economic performance and well-being between these countries

such as Greece, Portugal or Italy and countries less affected by the crisis, like Germany, the

Netherlands and the UK has driven a wedge between these two groups, which may not come

in handy when a unified European Union would have to be more vital than ever in crises times.

Therefore, in order to learn from past mistakes, it is paramount to understand what the concept

of stereotyping is and internalize what consequences they might bring to the well-being of

organizations that work with many different EU nationalities.

A stereotype refers to “a widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a

particular type of person or thing”1 and may be described as a “specific belief about groups”

(Vescio & Weaver, 2013: 1). Stereotyping could be described as the process of classifying a

person according to one’s own group characteristics (Vescio & Weaver, 2013). An inherent, as

well as apparent classification and subdivision into different groups, which is widely evident

to apprehend is the affiliation to a certain nationality. In this context, it is the same old European

story: Others characterise northern Europeans as efficient, organized and often humourless,

1Definition of “Stereotype” from the online Oxford Dictionaries.

5

while in the wake of the Euro Crisis Southerners are recently labelled as lazy, too easy-going

but likeable. While academic research has made it apparent that stereotyping can have

detrimental implications for group functioning such as anxiety and hostility (Tsui, Egan, &

O’Reilly, 1992), which in turn can increase the conflict experienced within a (work) group,

such as relational conflict (Jehn, Chadwick & Thatcher, 1997), Vorauer, Main & O’Connell (1998) have also discovered substantial effects of meta-stereotypes on the emotional level of

intergroup relations. Meta-stereotypes “refer to individuals’ beliefs about how their group is viewed by particular different groups” (Vorauer et al., 1998: 917). Meta-stereotypes have so far not been studied in the context of the European Union or Europe as a whole. A relevant

addition to the current state of research for meta-stereotypes is the integration of an analysis of

the behavioural level, as stereotyping also operates on this dimension (Rosado, 2015). The

behavioural level within stereotyping often involves the tendency to discriminate, however

might in turn also affect the selfless concern for others and therefore the altruistic behaviour in

a work environment. Another question arising when investigating meta-stereotypes is if they

follow the same mixed content patterns than so-called “other-stereotypes”. Hence, the aim of this study is to investigate the mixed content pattern of meta-stereotypes for two diverging

cultural clusters (Germanic and Latin Europe cluster) and to further examine its relationship to

affective behaviour toward other nationality groups, such as altruism, meeting satisfaction and

adjustment.

Firstly, an extensive literature review of the various areas within the concept of stereotyping

will be presented, as well as its relating theory. Hypotheses on the relationship of

meta-stereotypes to adjustment, meeting satisfaction and altruism follow in the third part. The

methodology, including the sample, questionnaire and procedure is described in the fourth part

of this study. The fifth part consists of the description of the statistical results of the SPSS

6

adjustment, meeting satisfaction and altruism follows as a sixth part. The study ends with

limitations of this study, recommendations for further research and wraps up with a conclusion

and an organizational take-away.

Literature Review

The stereotype literature is very rich in scope, as stereotyping may be applied to all kinds

of social groups. Further, the process of stereotyping involves predominantly other-stereotypes,

where most of the existing academic research has focused on, as well as meta-stereotypes,

which will be the focus of this study.

In order to thoroughly understand what the concept of stereotyping is, it is useful to

establish in which social theories it has its roots, as well as investigate relating concepts. The

process of stereotyping, including meta-stereotyping and self-stereotyping is greatly related to

the process of social categorization, which is derived from Social Identity Theory (SIT)

originally proposed by Taijfel and Turner in the late 1970s in the area of social psychology. In

essence, SIT describes how individuals associate themselves to a social category, which may

range from nationality to political party adherence. These often salient social category

attributes then determine the self-perception according to these category features (Hogg, Terry

& White, 1995). The self is thus perceived through means of a social category membership.

McLeod (2008)2 explains that these social groups are fundamental for the self-esteem and the

composition of our social identity. Thus, SIT states that individuals perceive themselves as a

personal self through the belonging of a specific social group.

Van Knippenberg, de Dreu & Homan (2004) argue that social category diversity, which

includes nationality diversity, elicits a social categorization process. Given the review of SIT

this study argues that the process of stereotyping activates a social and/or self-categorization

2Definition of “Social Identity Theory” from SimplyPsychology.

7

process by proxy, as it represents a mechanism for evaluating the self against other group

members (Vescio & Weaver, 2013). It may further be claimed that stereotyping illustrates a

cognitive bias, because stereotypes, as well as general social categorization processes depict a

cognitive tool of the mind to intrinsically establish a belonging to a certain (social) group in

order to define the individual self, which is essentially systematic in itself (Ashmore & Del

Boca, 1981). Here, the term “bias” designates that a judgement is made without basing it on

objective grounds, eventually leading to an “unfair, illegitimate or unjustifiable response”

(Hewstone, Rubin &Willis, 2002: 576). Indeed, a concept highly related to stereotypes and

prejudices is the so-called intergroup bias, also referred to as in-group favouritism. Simply put,

the mind splits our social surrounding in “we” and “them”, which is also denoted as the in- and

outgroup (McLeod, 2008). The intergroup bias specifies this social categorization process as a

systematic pattern of favouring the in-group over the outgroup (Hewstone et al., 2002), where

salient categorizations, such as nationality diversity may lead to such intergroup bias (Van

Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). The social cognition perspective points out that

categorization processes occur in intergroup interactions (Judd, 2005). Thus, having

established that stereotyping represents a form of basic categorization, which is elicited by a

cognitive bias (Ashmore & Del Boca, 1981); stereotyping may very well lead to an intergroup

bias, which cannot be feasible for multinational organizations.

Much of the pertaining stereotype and prejudice literature of the 20th century has focused

on (new) racism theories, following America’s black and white history, as well as World War

II’s antisemitism (Vescio &Weaver, 2013). Other prominent concepts include sexism, where

leading scholars have focused on women being wholly discriminated in the workplace, as well

as being prevented to be promoted to organizational leaders (Eagly, Makhijani, & Klonsky,

1992; Glick & Fiske, 1996; Cuddy, Fiske & Glick, 2004; Heilman, 2001). Ageism, in which

8

2005), which ultimately influences interpersonal relations with younger people and affect the

labour market, is another theme that reoccurs in the stereotype area.

The investigation of national stereotypes has been widely carried out in the

Asian-American content context (e.g. Lin et al., 2005) by for example examining the differences of

strategic decision making between American and Asian leaders in the academic field of

Management and Leadership styles (e.g. Martinsons & Davison, 2007). The carried out

research of national stereotypes within Europe, specifically the European Union is however

scarce. A prominent study in this specific scope is certainly Pettigrew and Meertens’ (1995)

investigation of subtle and blatant prejudice in Western Europe, which cross-examines

prejudice of e.g. Germans against Turks, French toward North-Africans and Dutch against

Surinamers, eventually being able to present a more exact interpretation of the effects of

prejudice against immigrants (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). The scarcity of research for

national stereotypes within the European Union acts as motive for this work project.

Further, Fiske, Cuddy & Glick’s (2002) study of stereotype content has set a milestone in the area of social psychology and has since then marked a new chapter for investigating

stereotypes of all kind. Their study (2002) established that stereotypes are classified along the

lines of two content dimensions, namely competence and warmth, which are respectively

inferred from the perception of the level of status and competition toward the in-group. Most

stereotyped groups follow a mixed content pattern, meaning that they score high on either one

of the dimensions, while only achieving a low level on the other dimension (Fiske et al., 2002).

Take the often stereotyped group of feminists as an example: Usually, they are characterized

as high in competence but low in warmth, e.g. feminists are said to be envious. In contrast,

housewives will follow a paternalistic stereotype content pattern in that they are mostly seen

9

The idea that the emergence of stereotypes is linked to social status is not a completely new

insight. Conversely to Fiske’s et al. (2002) stereotype content model, Vorauer, Main &

O’Connell (1998) investigated how so-called high- and low status groups believe they are

perceived by their counterpart and thus introduced the term meta-stereotype. Meta-stereotypes

“refer to individuals’ beliefs about how their group is viewed by a particular outgroup rather

than to individuals’ own personal belief about their group” (Vorauer et al. 1998: 917), which

would be denoted as a self-stereotype (Hogg & Turner, 1987). The negative meta-stereotypes

anticipated by high status groups on how they are seen by low status groups led to the

emergence of negative emotions during intergroup interactions, such as a lower self-esteem,

which will eventually decrease the willingness to share personal information or to give

intragroup feedback (Vorauer et al., 1998). Lower status groups held considerable stronger

meta-stereotypes than did high status groups, however both group’s meta-stereotypes were quite consistent in relation to their group identification and personal values (Vorauer et al.,

1998). Vorauer’s et al. (1998) low status groups may be associated with Fiske’s et al. (2002)

low competence and high warmth groups (e.g. housewives) with regard to content, while high

status groups might be linked to high competence and low warmth groups.

Hypotheses

Paternalistic and Envious Meta-Stereotypes

Stereotypes arise out of the communication and interchange with outgroups and are the

result of an intrinsic but basic intention for the interaction: the evaluation of the outgroup’s goals and magnitude of impact toward the in-group (Fiske et al., 2002). The evaluation of intent

about the outgroup might be characterised as an act of placation and leads to the equilibration

of the threat of competence or the thereof lack, which eventually results in the equilibrium of

mixed stereotypes in content (Fiske et al., 2002). Paternalistic groups, that are incompetent are

10

that are competitively threatening (e.g. socioeconomically successful) will be assigned as

asocial and socially cold (Fiske et al., 2002).

This might be a process that is followed unconsciously, however might equally be

reproduced when attempting to appraise the outgroup’s evaluation of its own ingroup, i.e. when applied to meta-stereotypes. On the one hand thus, this “give and take” process might work both ways, because we ascribe the same pattern of cognitive way of reasoning and perceiving

to members of our outgroup or on the other hand, because we copy and repeat what the cliché

stereotypes assign us to think. Either way, it is assumed that meta-stereotypes of the own group

follow the same content pattern as stereotypes against other groups, i.e. meta-stereotypes are

either paternalistic or envious in nature and might therefore be particularly powerful in

predicting behaviour toward the outgroup (Wakefield, Hopkins & Greenwood , 2012). This is

assumed, as meta-stereotypes have been found out to be eliciting specific behaviour toward the

outgroup (to avoid confirming potential stereotypes) or an avoidance of behaviour (i.e. help

seeking) when they were dependency-related in content nature (Wakefield et al., 2012).

Extending the assumption of two types of meta-stereotypes toward the two subgroups of

crisis-affected and less crisis-crisis-affected countries, it is reasonable to believe that crisis-crisis-affected

countries appraise less crisis-affected countries as envious and less crisis-affected countries

believe affected countries are seen as paternalistic in nature. The rationale behind this follows

Fiske et al. (2002) arguments of mixed stereotypes. On the one hand, since Germany, the

Netherlands, Belgium and Austria have had relative economic success in the course of the Euro

crisis, which ultimately makes them competitively threatening, they might describe themselves

as socially undesirable as seen by the crisis-affected countries. The economic success also leads

them to believe that outgroups perceive them as more competent, capable and efficient but

however, in return as less warm, insincere and less well-intentioned (Fiske et al., 2002) and in

11

Portugal, Spain, Italy and France that had to endure the opposite economic outcome of the Euro

crisis might believe that less crisis-affected countries perceive them as incompetent, inefficient

and even unintelligent or more dependent on others (Wakefield et al. 2012). This competitively

unthreatening character might lead to a self-appraisal of warmth, good-natured and friendliness

in the eyes of the outgroup (Fiske et al., 2002). Thus, more affected and less

crisis-affected countries are presumed to appraise themselves significantly different in terms of

competence and warmth in the eye of the opposite cluster. These predictions and assumptions

result in the following first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Less crisis-affected countries (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Austria) will depict envious meta-stereotypes, while more crisis-affected countries (e.g. Portugal, Spain, Italy and France) will demonstrate paternalistic meta-stereotypes.

Meta-Stereotypes, Meeting Satisfaction, Adjustment and Altruism

It is widely known that stereotypes, which are held about outgroups, can be quickly

re-evaluated, adjusted or even completely abandoned in the course of an intergroup interaction,

because of information that is gathered about the individual of the other group (Locksley et al.,

1980). This deeper insight, e.g. that a member of an outgroup does not actually behave as

prejudiced beforehand, might lead to discard the stereotype. Thus, the evaluated outcome of

the interaction with the outgroup might turn out more favourable than previously assumed, as

"negative expectations" are not met.Consequently, in multicultural work environments where

meeting and working with colleagues who are demographically different becomes paramount,

the satisfaction outcome of a meeting is presumed not to be highly correlated with pre-existing

stereotypes about others. Chen and King´s study (2002) on communication satisfaction and the

existence of positive vs. negative and neutral age stereotypes confirms this assumption. Only

positive age stereotypes led to a higher communication satisfaction and lower dissatisfaction

(King, 2002). Moreover, if stereotypes are readily disregarded after a first interaction with the

12

likely to help them in times of need as their demographically similar peers. Hence, altruism

might likewise not be related to other-stereotypes, as they can quickly be abandoned.

Altruism, which is the “willingness to do things that bring advantages to others, even if

it results in a disadvantage for yourself”3, also called the "good soldier syndrome" (Organ,

1988), as well as meeting satisfaction might however be very well related to meta-stereotypes.

Altruistic organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) is characterised by conscientiousness,

sportsmanship and courtesy and is believed to positively impact organizations (Organ, 1988),

as well as increase job satisfaction (Donovan, Brown & Mowen, 2004). This rationale of the

relationship between these two variables and meta-stereotypes might stem from the fact that

meta-stereotypes are not so easily revised, as the information exchange is much more

impenetrable (Vorauer et al., 1998). The revision of meta-stereotypes would have to imply to

directly inquire the outgroup about their beliefs of their respective outgroup member (Vorauer

et al., 1998) and this might only occur when the two interacting people are already fairly close

and friendly with each other. Similarly, Vorauer et al. (1998:917) argue that “much of the potential aversiveness of intergroup interaction” lies in the “individual’s sense of the impressions that are formed of them rather than in the impressions they form of the outgroup

member”. Also other researchers seem apt to assume that individuals who contemplate that

they are being judged show distorted behaviour within the interaction, because of a feeling of

loss of control in how they are perceived (Rothbaum, Weisz & Snyder, 1982). This sense of

loss of control and the preoccupation of individuals’ perception of being negatively stereotyped

might lead them to a less positive behaviour (Snyder & Wicklund, 1981). Therefore, the

existence of meta-stereotypes might have the consequence of a distorted altruistic behaviour

toward the outgroup member, as well as an unsatisfying meeting with the outgroup member.

3Definition of “Altruism” from the online Cambridge Dictionary.

13

This effect might occur because the impressions that are formed in meta-stereotypes

are more associated with the self-concept (Vorauer et al., 1998), which is in line with the SI T

and may therefore weigh more heavily in social categorization processes. Rogelberg et al.

(2010) suggested in their study that meeting satisfaction plays ultimately a key role for job

satisfaction. Hence, meeting satisfaction may greatly influence individuals’ willingness to

selflessly contribute to others’ well-being within the logic of when overall job satisfaction is high, a higher level of commitment and OCB is engaged (Talachi, Gorji, Boerhannoeddin,

2014). Therefore, the effect of meeting satisfaction may also be assumed as a mediating one

between meta-stereotypes and altruism, as it may be argued that meta-stereotypes lead to a

decreased meeting satisfaction, which as a consequence lead to less altruism.

A possible factor, which may in hindsight compensate for or even impede a negative

effect of meta-stereotypes on distorted interactions and behaviour toward the outgroup could

be the adjustment to the outgroup. The degree of adjustment to members of the outgroup is

characterised by how accustomed individuals are while interacting, socializing and speaking

with them, also outside of the work environment (Black & Stephens, 1989). Thus, the more

often outgroups interact in a fruitful manner, the more adjusted they will be to one another.

Black and Stephens (1989) investigated the relationship between expats’ intent to stay abroad with their degree of adjustment to the expat community. Among other factors, it was found that

the more adjusted expats are, the easier it is to retain them. Moreover, it is suggested that

workers seek to minimalize sources of negative affective responses, while retaining positive

ones (Black & Stephens, 1989). Adjustment, which is hypothesized to be another measure for

affective responses (Black & Stephens, 1989), may act as a mechanism to do so. From these

findings, it seems reasonable to assume that adjustment in its very nature might also act as a

14

in the following two hypotheses and are visualized in a conceptualized diagram in Figure 1

below:

Hypothesis 2a:Adjustment mediates the relationship between meta-stereotypes and altruism

Hypothesis 2b:Meeting Satisfaction mediates the relationship between meta-stereotypes and altruism

Methodology

Sample and Procedure

The participants of this sample constituted of EU officials or individuals holding some form of

contractual relation (e.g. permanent officials, contract, temporary or interim staff, trainees,

seconded national experts and parliamentary assistants) with three different EU institutions,

i.e. the European Commission, the European Parliament and Eurocontrol (the European

Organization for the safety of air navigation). The specificity of this sample was chosen for

reasons of its multinational character and the guarantee of reaching various different and for

the study relevant EU nationals. Since all eight relevant nationalities are employed in the EU

institutions, it could therefore be given that all targeted nationalities and countries would be

represented in the sample. A total of 254 respondents completed the survey, of which 36 had

to be excluded. Of the 218 remaining respondents two clusters were administered. These two

clusters were formed on the basis of the GLOBE framework. The GLOBE study postulated

that 62 countries could be subdivided into regional clusters based on cultural similarities and

15

differences (House et al., 2004). Here, two clusters fitted this study’s objective to separate more crisis-affected countries from less crisis-affected countries, supported by cultural differences

of the GLOBE study: The Latin Europe cluster, where Italy, Portugal, Spain and France are

aggregated by means of the Roman culture and the Germanic cluster, consisting of Germany,

the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria, pooled on the basis of the shared Germanic language

and Germanic culture (House et al., 2004). Respondents’ nationalities were distributed as follows: German=55, Dutch=33, Belgian=47, Austrian=1, Italian=32, Portuguese=17,

Spanish=19, French= 14, yielding a total of 136 respondents for the Germanic cluster and 82

for the Latin Europe cluster, which resulted in proportions of roughly 0.6 for the Germanic and

0.4 for the Latin Europe cluster. In terms of descriptive statistics, the sample of respondents

was highly balanced out in its age, which ranged from 18 to 65 or higher. The most frequent

age range, however, was 45 to 54 attaining roughly a percentage of 27%. Furthermore, the

sample was composed of 53% of male and 47% of female respondents. Type of employment

consisted in the largest part (55%) of permanent officials (e.g. MEPs, assistants, administrators,

secretaries, etc.), followed by contract- (17%) and temporary staff (12.5%).

Respondents were instructed that the survey’s aim was to get insights on how different nationalities believe their own nationality is perceived, as well as help to evaluate possible

effects on collaboration with their colleagues.

Moreover, respondents completed a developed questionnaire that consisted of nine

questions, which was partly distributed face to face in the European Parliament mid October

2016. Qualified members of the European Parliament (MEP´s, n=382) were directly emailed

with a request to fill out the questionnaire, while potential other recipients from the EC and

Eurocontrol were reached by sending the survey via mail to a circle of acquaintances, which

distributed it further to colleagues. As this study’s objective was to test specific relationships

16

asked which nationality they had in order to lead them to the corresponding adapted questions.

This was done with an “if” condition in Qualtrics, as respondents from the Germanic cluster

were supposed to think about meta-stereotypes sourcing from the Latin Europe cluster and vice

versa. The options for the nationalities to choose from only consisted of the ones important for

this study, which belong to the specified clusters (e.g. German, Belgian, Dutch, Austrian and

Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, French). Respondents belonging to another nationality had the

option “other” and were immediately directed to the end of the survey. Since it seemed difficult

to think about meta-stereotypes sourcing from a whole cultural cluster, one proxy or

representative was chosen for each cluster, i.e. Germans for the Germanic cluster and

Portuguese for the Latin Europe cluster. Therefore, the second question read as follows for

respondents from the Germanic cluster: “to which extent do you think the Portuguese see the

[respondent’s own nationality] as…?” and “to which extent do you think the Germans see the [respondent’s own nationality] as…?” for the Latin Europe cluster

Measures

Meta-stereotypes: The second question of the questionnaire was designed to test if

meta-stereotypes from the two clusters were either paternalistic or envious in stereotype

content nature. Thus, respondents were asked to rate on a 5-point likert scale (1=not at all,

5=very great extent) to which extent their nationality group was perceived in terms of the

constructs warmth (e.g. friendly, well-intentioned, trustworthy, warm, good-natured, sincere)

and competence (e.g. competent, confident, capable, efficient, intelligent, skilful) by the

opposite cluster in order to measure meta-stereotypes. The scale to measure warmth and

competence was adopted from the stereotype mixed content model by Fiske et al. (2002).

Reliability tests of the scales for the variables warmth and competence were performed, where

Cronbach’s alpha was higher than 0.7 for most nationality groups. Concerning warmth, alphas

were problematic for the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Austrians and were as follows: French

17

Belgian = 0.76, Dutch = 0.77, Austrian = n/a and German = 0.79 for the Germanic cluster. The

scale for competence did not satisfy reliability for the Spanish and the Austrians (i.e. French =

0.86, Spanish = 0.65, Italian = 0.83, Portuguese = 0.89, Belgian = 0.75, Dutch = 0.75, Austrian

= n/a and German = 0.77).

Meeting satisfaction: The scale of meeting satisfaction was taken from the study

developed by Rogelberg et al. (2010) and contained six items. Again, a 5-point likert scale was

adopted, ranging from 1=not at all to 5=very great extent. Cronbach’s alpha was not high

enough for both clusters (Latin Europe: α=0.48, Germanic:α=0.58).

Adjustment: Adjustment was measured on the basis of Black and Stephens’ (1989)

expatriate’s adjustment scale, where some items had to be dropped, resulting in four final items.

This variable was also measured measured on a 5-point likert scale (1=not at all, 5=very great

extent). Reliability was sufficiently established for both cluster (Latin Europe: α=0.87, Germanic: α=0.78).

Altruism: Finally, the scale of altruism was adopted from Chattopadhyay’s study (1999) on the influence of demographic dissimilarity on OCB and only included those items

that were concerned with the social dimension of the OCB concept. It was measured on a

5-point likert scale (1=not at all, 5=very great extent) and also here, reliability of scales was given

for both clusters (Latin Europe: α=0.93, Germanic:α=0.89).

Results

Hypothesis 1 was set up to test if meta-stereotypes belonging to the two clusters

established by the Globe framework follow the same mixed content model than

other-stereotypes proposed by Fiske et al., (2002). For this to be true, meta-other-stereotypes of the Latin

Europe cluster should depict high warmth but low competence, while the Germanic cluster

must illustrate high competence and low warmth. Further, an independent samples t-test was

2-18

tailed significance level of below 0.05 (sig = 0.000) for both warmth and competence.

Therefore, there is a statistically significant difference between the mean of the extent to which

the Germanic and Latin Europe cluster believe they are perceived in warmth and competence.

The group statistics of the t-test revealed that the Germanic cluster believes on average that

they are perceived to a great extent (x̅ = 3.9) as competent from the Latin Europeans, while the Latin Europe cluster only believes that they a seen as somewhat competent (x̅ = 2.9)by the Germanics, which supports hypothesis 1. Appraisal for warmth however, although being

statistically different for both clusters, does not illustrate such a strong discrepancy. It is rated

on a higher level (x̅ = 3.6) by the Latin Europe cluster and as considerably lower (x̅ = 3.2) by the Germanics, which supports hypothesis 1 as well.

In order to investigate patterns, a correlation matrix was performed in SPSS to see

significant relationships between the outcome variables (see Appendix for exhibit 1 and 2).

Again, to see differences in the two clusters, the data set was split on the basis of nationalities.

Further, to test hypothesis 2a and 2b Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS was used, which is a regression-based approach. Model 4 of Hayes’ developed templates (2013) for testing moderating and mediating effect served as a conceptual basis for the analysis, where

warmth constituted X for the Germanic cluster and competence as X for the Latin Europe

cluster. Adjustment served as M (mediation variable) and altruism as Y (outcome variable) in

both clusters. Meeting Satisfaction was included as covariate in both cluster analyses for

controlling variables, while competence, age and gender were covariates in the Germanic

cluster model. Warmth, as well as age served as a control statistic in the Latin Europe model.

Gender was not included in this cluster, as it did not correlate with any of the outcome variables,

e.g. warmth, competence, meeting satisfaction, adjustment and altruism when filtering for

19

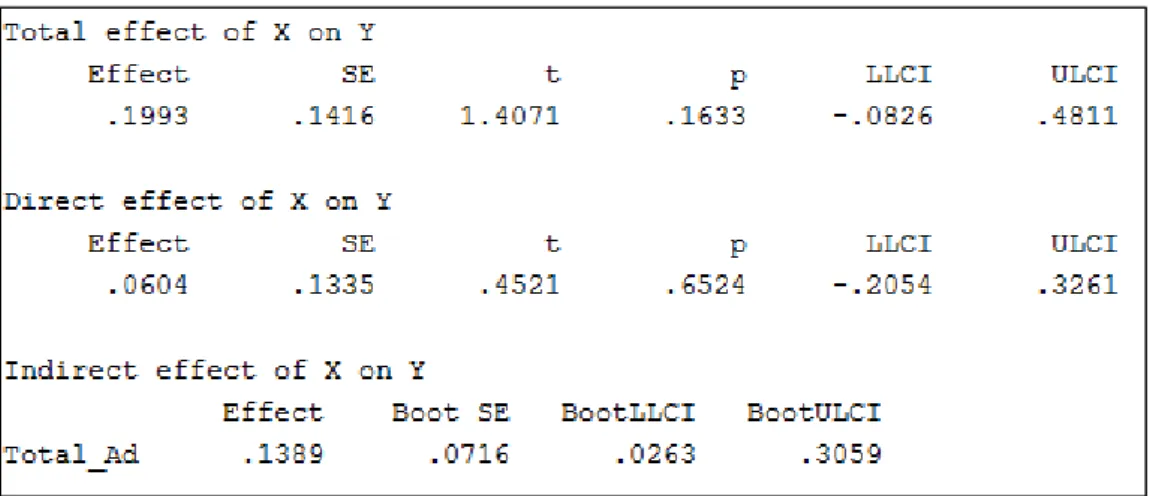

The different paths (A, B, C) for model 4 within the Latin Europe cluster resulted in

first evidence for a mediation effect of adjustment on the relationship between competence and

altruism in that competence was significantly related to adjustment (A = .30; LLCI .05, UCLI

.64), which in turn was significantly related to altruism (B = .29; LLCI .21, UCLI .59).

Competence and Altruism (C = .19; LLCI -.08, UCLI .48) were not significantly related. The

results for the Latin Europe cluster of Hayes’ PROCESS model 4 of the total, direct and indirect

effects are shown in Table 2. When applying the bootstrapping method, the results of the

indirect effect of X on Y illustrate evidence for adjustment indeed acting as a mediator between

warmth and altruism (BootLLCI .03, BootULCI .31), giving support for hypothesis 2a. The

control variables meeting satisfaction and warmth were not significantly related to the variables

of competence and altruism, and the confidence intervals were containing zero as a central

point. There is thus no support for hypothesis 2b.

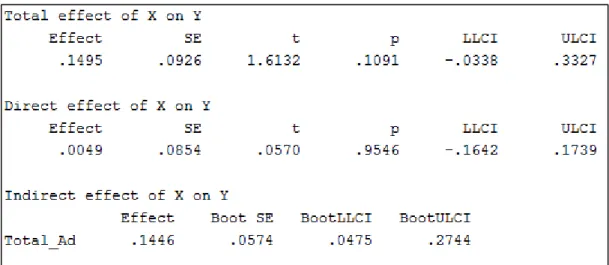

Similarly, the Germanic cluster analysis showed a mediation effect of adjustment on

the relationship between warmth and altruism. Also here, there is a significant relation between

warmth and adjustment (A = .36; LLCI .15, ULCI .69), a significant relationship between

adjustment and altruism (B = .29; LLCI .26, ULCI .51) and a non-significant direct relationship

between warmth and altruism (C = .00; LLCI -.03 ULCI .33). Likewise, the bootstrapping

lower and upper confidence interval of the indirect effect (BootLLCI .05, BootULCI .27)

20

highlights the mediation effect of adjustment by not containing zero as a central point (see

Table 3), supporting hypothesis 2a for the Germanic cluster. Again, the control variables

competence, meeting satisfaction and age were not significant and confidence intervals

included zero, which demonstrates no support for hypothesis 2b within the Germanic cluster.

Discussion

This study firstly confirms that meta-stereotypes indeed follow the same content pattern

than other-stereotypes by Fiske et al. (2002), namely that meta-stereotypes are believed to be

located at the dimension of warmth and competence. Individuals assume that outgroup

members perceive and evaluate them by means of being either highly competent or highly

sociable, while scoring low levels on the opposite dimension. This study demonstrates that

affected Euro crisis countries, which are aggregated in the Latin Europe area by the GLOBE

study on the basis of similar cultural traits (e.g. Portugal, Spain, Italy and France) adopt a

paternalistic meta-stereotype content pattern: Latin Europeans believe they are seen as highly

warm in character but fairly incompetent by their Germanic counterpart. The study further

illustrates that Germanics think Latin Europeans evaluate them as very competent but not as

sociable, i.e. Germanics adopt an envious meta-stereotype content pattern. Secondly, this study

depicts that the Latin European dimension of competence predicts the extent to which Latin

21

Europeans adjust to their Germanic colleague. The extent of Latin European adjustment to

Germanics in turn, predicts the level of altruism toward Germanics. Conversely, the Germanic

dimension of warmth is related to the Germanic adjustment to their Latin European colleagues,

which again predicts Germanic altruism to Latin Europeans. Meeting satisfaction, as well as

demographic control variables had no effect in both models.

The measured meta-stereotypes, as well as its content pattern might serve as evidence

for social categorization processes on account of the Euro crisis. This insight represents an

important part of this work project as it prevails as vital proposition for this study. This is

because Van Knippenberg and Schippers (2007: 525) argue that few scholars have presented

“direct evidence of social categorization processes”. They note that academic research in the

field has only concluded that diversity in many forms may elicit categorization processes (Van

Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). Furthermore, Van Knippenberg et al. (2004: 1015) propose

that categorization processes occur “to the extent that the identity implied by the categorization is subjectively threatened or challenged”. In this context, they define challenges as “unequal status of subgroups and competitive interdependence between subgroups” (Van Knippenberg

et al., 2004: 1015). The measured meta-stereotypes of this study serve as direct evidence for a

social categorization process as it is argued that the Euro crisis has created two subgroups

within the European Union, namely the crisis-affected countries and the less crisis-affected

countries. Furthermore, the Euro crisis has created a perception of unequal status and a

competitive interdependence contingent on financial resource allocation and ultimately the

maintenance of a common European currency, the Euro, which is in line with Van

Knippenberg’s et al. (2004) definition for a group’s challenged identity.

The measured meta-stereotypes are underlying findings of this study to complete

prevailing voids in the academic research field of social categorization processes, as claimed

22

of unequal status resulting from the Euro crisis back up the proposed claim of evidence for

social categorization processes in that it provides reason for a challenged and threatened

identity in the wake of the Euro crisis and by that giving more evidence for an actual social

categorization process. Lastly, the grouping into two different clusters served as a

methodological procedure to concretely capture the two proposed subgroups, recently emerged

from social categorization on the account of the Euro crisis. The classification was thus not

arbitrary in that it differentiated countries having a different economic success, as well as

grouping them into a similar cultural cluster.

Moreover, the results of this study are twofold, because of the nature of respondents in

the research design. Firstly, the staggering existence of meta-stereotypes in such a multicultural

work environment is in line with the previous assumptions of the cumbersome disposal of

meta-stereotypes (see Vorauer et al., 1998) and shows that no one is exempt from feeling

stereotyped, even when working in a prestigious multinational institution. Meta-stereotypes are

therefore difficult to abandon in that the stagnancy of the information exchange creates lengthy

scanning and confirmation processes. In other words, it is unhandy to simply ask or even

convince the counterpart of their existing outgroup stereotypes. Furthermore, this is because

meta-stereotypes concern our self-perception and image and should thus preferably be as

accurate as possible in order to confirm and be consistent with them (Vorauer et al. 1998)

However, this becomes more and more difficult, as the outgroup would have to be influenced

and convinced of a potential inaccuracy. More importantly, (meta)-stereotypes are in its very

nature inaccurate as contemplated by many researchers (e.g. Campbell, 1967 or Ashton &

Esses, 1999). This inaccuracy and the very nature of (meta)-stereotypes is argued to lead to

clear social categorization processes, which may even transform into intergroup bias. The

mixed content and the affiliation of this study’s clusters to paternalistic and envious patterns

23

fortified by the recent Euro crisis, as argued by this study. Economically successful groups

assume they are envied for this success and are therefore written off as unsocial, while

economically unsuccessful groups believe they must be pitied for it, albeit appreciated for their

social competence (see Fiske et al., 2002).

More important is however, the effect of meta-stereotype content on adjustment, which in

turn predicts altruistic behaviour. Surprisingly, there is no direct relationship between warmth

and altruism within neither cluster, which could have been explained by the self-fulfilling

prophecy bias and social stereotypes (Snyder, Tanke & Berscheid, 1977). The self-fulfilling

prophecy is a false prediction that involuntarily becomes true because of the very terms and

expectations of the prophecy (Merton, 1948). The dimension of warmth seems particularly apt

to be consistent with altruistic behaviour, as these variables are concerned with social

competence. The self-fulfilling prophecy bias explains how this would work. If an individual

believes that they are seen as more warm, such as being friendly, sincere or well-intentioned,

this individual might respond to these meta-stereotypes in the way of really acting and behaving

more selflessly towards the outgroup to fulfil this expectation. In this sense, paternalistic

meta-stereotypical groups would have shown a positive relationship with altruistic behaviour.

Conversely, someone that thinks he is evaluated as asocial or less sympathetic will indeed

behave in this same way. He might believe that he is anyway perceived as cold-hearted by the

outgroup and may therefore unconsciously want to match this belief by reacting cold-hearted.

Hence, envious meta-stereotypical should have been predicted to show a negative relationship

to altruism. However, it is not quite as simple. Quite the contrary, it is the unremarkable and

less salient dimension of content, which drives individuals to be more adjusted to the outgroup,

which then can lead to selfless altruistic behaviour, e.g. warmth for the Germanics and

competence for the Latin Europe cluster. This is aligned with research on selective

24

the quality that normally is not attributed to their group (Biernat, Vescio & Green, 1996).

Remarkably, it is this this unattributed trait that predicts individuals to be more adjusted to their

outgroup and in turn be more altruistic to the member of the outgroup. Consistent with the

selective self-stereotyping literature, this demonstrates that it is not the stereotypical trait, but

the non-stereotypical quality that is highly descriptive for a particular group (Biernat et al.,

1996). In other words, if a Germanic thinks he is seen as quite warm (thus, contradicting to

the overall’s stereotypical perception of the group), it is only then that this attribute leads him

to be more adjusted to a Latin European colleague, which successively makes him behave more

altruistically. In contrast, the Latin European will feel more adjusted and behave selflessly

toward the Germanic, when he believes that he is seen as fairly competent. This effect is an

examined response to the “negative in-group characterization threat”, which occurs when an

in-group fears to be exposed to negative attributes (Biernat et al., 1996). Therefore, at a first

step, meta-stereotypes that do not correspond to the usual expectation of the in-group only have

a positive effect on altruistic behaviour toward outgroup colleagues when the individual is

confident and adjusted to the outgroup. The notion of the non-attributed quality on adjustment

is also aligned with theories on group conformity and valuation and appreciation within the

group, where conformity and high appreciation of a group member is only granted when the

member is also highly valued by other groups (Emerson, 1962). Therefore, in order to be

adjusted and helpful toward other groups, it is necessary to evaluate the factors that influence

individual’s beliefs about the own group. Thus, adjustment means exhibiting and believing in the qualities that are normally not attributed to your group to a certain extent. The effect of

adjustment on altruism is aligned to the theory that adjustment fosters outgroup affiliation and

might therefore have an effect on job satisfaction (Black & Stephens, 1989).

Lastly, meta-stereotypes might not have had an effect on meeting satisfaction, as

25

time, efficiency and effectiveness of the meeting or length of the meeting (Dennis, Haley &

Vandenberg, 1996). It might be also be argued that when group outcomes are overly negative

(such as group conflict), is this ascribed to differences of the group (e.g. see Jehn, Northcraft

& Neale, 1999). Pelled´s study (1996) suggests that visible diversity, such as race, influence

the level of emotional and task conflict. Positive outcomes such as meeting satisfaction might

not be assumed to be related to visible demographic differences within working group as they

are encountered in meetings in multinational organizations.

Practical Implications for Organizations

The finding that meta-stereotypes follow the same content pattern as stereotypes has

some practical implications, as well as the results in relation to adjustment and altruism. In this

sense, the way we think about other individuals, applies also to the appraisal and evaluation we

believe others make about us. We tend to divide these evaluations into two dimensions, namely

warmth and competence, which are closely linked to the appraisal of the extent of competition

threat. Organizations should be aware of the fact that meta-stereotypes are not easily abandoned

and exist even in the most multi-national institutions, where working with other nationalities

comes naturally, as well as where speaking three different languages is a given. Further, the

EU institutions that should thrive for a psychological safety environment, in which nationalities

alongside with its implied stereotypes must not play a role. However, they do play a role in that

EU officials perceive meta-stereotypes by differently feeling evaluated by other nationalities.

In a highly professional work environment however, this should not be the case. Thus, the

effective coping with meta-stereotypes demonstrates itself as the only option for mitigation.

This may come in several forms, such as raising awareness and facilitating communication for

information exchange. A simple workshop, where meta-stereotypes are firstly discussed and

outlined and where secondly, implications for working with each other are reviewed may breed

26

Adjustment is fostered by the non-stereotypical dimension of the group. Organizations

must be aware that meta-stereotyping ultimately has an effect on categorization, thus

self-esteem should be enhanced and negative characterisation threat should be mitigated. Morover,

adjustment facilitates altruism, which may stimulate OCB and therefore job satisfaction.

Hence, organizations should foster adjustment in order to profit from positive consequences,

such as altruistic behaviour.

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

Limitations of this study present themselves firstly on the basis of the respondent’s design. EU officials are by nature more adjusted to their co-workers that do not belong to their

own nationality, stemming from their long-lived experience in this multi-cultural work

environment. Respondents’ were mostly permanent contract officials, who spoke up to five languages. Furthermore, especially the sample size of the Latin European cluster was critically

low. It can further be argued that France did not completely belong to the crisis country cluster.

Moreover, respondents adhered predominately to the socialist’s party, which might have influenced this study’s results. Finally, it has to be kept in mind that respondents worked mostly

in political and institutional environments (except for Eurocontrol). The question arises if the

results are transferable to businesses and other organizational settings.

The basic idea of this study was to extent the knowledge of meta-stereotypes to a

behavioural level. Further research could imply validating these results in another setting or

induce other behavioural variables. Empirical work should focus and develop the area of the

interaction process of the two clusters and study the exact factors leading to adjustment, such

as overcoming language barriers, etc. Furthermore, the effect of meta-stereotypes on other

organizational variables such as trust or intergroup conflict might give businesses and

27

Conclusion

The main findings of this study were that meta-stereotypes follow the same content pattern

as other-stereotypes. Furthermore, the Euro crisis has led to social categorization processes in

the form of meta-stereotypes, which divided crisis countries into a paternalistic content pattern,

while non-crisis countries remained at the level of an envious content pattern. Organizations,

such as the EU institutions have to make sure that these social categorization processes do not

create a bigger wedge between the two defined clusters as has done the crisis on its own.

Finally, a driving factor for adjustment to other nationalities is the non-attributed quality of the

own group, which relates to selective self-stereotyping. However, the insight that adjustment

to the outgroup mediates the effect of meta-stereotypes on altruistic behaviour toward the

outgroup demonstrates that there is an opportunity to mitigate potential intergroup biases and

self- or social categorization processes.

References

Ashmore, Richard D., and Frances K. Del Boca. 1981. "Conceptual approaches to stereotypes and stereotyping. " In: Cognitive Processes in Stereotyping and Intergroup Behavior (pp. 1-35), ed. D.L Hamilton. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Ashton, Michael C., and Victoria M. Esses. 1999. "Stereotype accuracy: Estimating the academic performance of ethnic groups" Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(2): 225-236.

Biernat, Monica. Theresa K. Vescio, and Michelle L. Green. 1996. "Selective self-stereotyping." Journal of personality and social psychology, 71(6): 1194

Black, Stewart J, and Gregory K. Stephens. 1989. "The Influence of the Spouse on American Expatriate Adjustment and Intent to Stay in Pacific Rim Overseas Assignments." Journal of Management, 15(4): 529-544.

Campbell, Donald T. 1967. "Stereotypes and the perception of group differences." American Psychologist, 22(10): 817-829.

Chattopadhyay, Prithviraj. 1991. "Beyond Direct and Symmetrical Effects: The Influence of Demographical Dissimilarity on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. " The Academy of Management Journal, 42(3): 273-287.

Chen, Yiwei, and Brian Edward King. 2002. "Intra-and Intergenerational Communication Satisfaction as a Function of an Individual´s Age and Age Stereotypes. " International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(6): 562-570.

Cuddy, Amy J.C., and Susan T. Fiske. 2002. "Doddering but dear: Process, content, and function in stereotyping of older persons." In Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons, ed. Todd D. Nelson: 3-26. Cambridge, M: The MIT Press.

Cuddy, Amy J.C., Susan T. Fiske, and Peter Glick. 2004. "When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn't cut the ice." Journal of Social Issues, 60(4): 701-718.

Dennis, Alan, Barbara Haley, and Robert Vandenberg. 1996. "A meta-analysis of effectiveness, efficiency, and participant satisfaction in group support systems research. " ICIS 1996 Proceedings, 20.

28

Donlon, Margie M., Ori Ashman, and Becca R. Levy. 2005. "Re‐vision of older television characters: A stereotype‐ awareness intervention." Journal of Social Issues, 61(2): 307-319.

Eagly, Alice H., Mona G. Makhijani, and Bruce G. Klonsky.1992. "Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis." Psychological bulletin, 111(1): 3-22.

Emerson, M. Richard. 1962. "Power-Dependence Relations. "American Sociological Review, 27(1): 31-41.

Fiske, Susan T., Amy J.C. Cuddy and Peter Glick. 2002. "A Model of (Often Mixed) Stereotype Content: Competence and Warmth Respectively Follow From Perceived Status and Competition." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6): 878-902.

Glick, Peter, and Susan T. Fiske. 1996. "The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism." Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(3): 491-512.

Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. "Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach." Guilford Press.

Heilman, Madeline E. 2001. "Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women's ascent up the organizational ladder." Journal of social issues, 57(4): 657-674.

Hewstone, Miles, Mark Rubin, and Hazel Willis. 2002. "Intergroup bias." Annual review of psychology, 53(1): 575-604.

Hogg, Michael A., and John C. Turner. 1987. "Intergroup behaviour, self‐stereotyping and the salience of social categories." British Journal of Social Psychology 26(4): 325-340.

Hogg, Michael A. Deborah J. Terry, and Katherine M. White. 1995. "A Tale of Two Theories: A Critical Comparison of Identity Theory with Social Identity Theory." Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4): 255-269.

House, Robert J., Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta. 2004. "A Nontechnical Summary of GLOBE Findings" In: Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage publications

Jehn, Karen A., Clint Chadwick, and Sherry M.B. Thatcher. 1997. "To Agree or Not To Agree: The Effects of Value Congruence, Individual Demographic Dissimilarity, and Conflict on Workgroup Outcomes." International Journal of Conflict Management, 8(4): 287-305.

Jehn, Karen A., Gregory B. Northcraft, and Margaret A. Neale. 1999. "Why Differences Make a Difference: A Field Study of Diversity, Conflict, and Performance in Workgroups. "Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4): 741-763.

Judd, Bernadette Park Charles M. 2005. "Rethinking the Link Between Categorization and Prejudice Within the Social Cognition Perspective." Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(2): 108-130.

Lin, Monica H., Virginia S.Y. Kwan, Anna Cheung, and Susan T. Fiske. 2005. "Stereotype content model explains prejudice for an envied outgroup: Scale of anti-Asian American stereotypes." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1): 34-47.

Locksley, A., Eugene Borgida, Nancy Brekke, and Christine Hepburn. 1980. "Sex stereotypes and social judgment. " Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 39(5), 821-831.

Martinsons, Maris G., and Robert M. Davison. 2007. "Strategic decision making and support systems: Comparing American, Japanese and Chinese management." Decision Support Systems, 43(1): 284-300.

Merton, Robert K. 1948. The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy. The Antioch Review, 8(2): 193-210.

Organ, Dennis W. 1988. "Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier syndrome. " Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com.

Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Roel W. Meertens. 1995. "Subtle and blatant prejudice in Western Europe." European journal of social psychology, 25(1): 57-75.

Pelled, Lisa H. 1996. "Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: An intervening process theory." Organization science, 7(6): 615-631.

29

Rosado, Caleb. 2015. "The Undergirding Factor is Power: Toward an Understanding of Prejudice and Racism. Critical Multicultural Pavilion. Retrieved from http://www.edchange.org/multicultural/papers/caleb/racism.html

Rothbaum, Fred, John R. Weisz, and Samuel S. Snyder.1982. "Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control." Journal of personality and social psychology, 42(1): 5-37.

Snyder, Mark, Elizabeth D. Tanke, and Ellen Berscheid. 1977. "Social perception and interpersonal behaviour: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9): 656.

Snyder, Melvin L., and Robert A. Wicklund. 1981."Attribute ambiguity." New directions in attribution research, 3: 197-221.

Talachi, Rahil K., Mohammed B. Gorji, and Ali B. Boerhannoeddin, 2014. "An Investigation of the Role of Job Satisfaction in Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior." Collegium Antripologicum, 38(2): 429-436.

Tsui, Anne S., Terri D. Egan, and Charles A. O'Reilly III. 1992. "Being Different: Relational Demography and Organizational Attachment." Administrative Science Quarterly: 549-579.

Turner, John C., and Katherine J. Reynolds. 2011. "Self-Categorization Theory" In The Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume Two, ed. Paul A.M.Van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski, E. Tory Higgins: Sage Publications

Van Knippenberg, Daan, Carsten K. W. De Dreu, and Astrid C. Homan. 2004. "Work Group Diversity and Group Performance: An Integrative Model and Research Agenda." Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6): 1008-1022.

Van Knippenberg, Daan, and Michaela C. Schippers. 2007. "Work group diversity." Annual Review of Psychology, 58: 515-541.

Vescio, Theresa K., and Kevin Weaver. 2013. Oxford bibliographies. Psychology. Prejudice and Stereotyping. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Vorauer, Jacquie D., Kelley J. Main, and Gordon B. O'Connell. 1998. "How Do Individuals Expect to Be Viewed by Members of Lower Status Groups? Content and Implications of Meta-Stereotypes." Journal of personality and social psychology, 75(4): 917.

30

Appendix

31