Revista

de

Administração

http://rausp.usp.br/ RevistadeAdministração51(2016)397–408

Technology

management

The

influence

of

innovation

environments

in

R&D

results

A

influência

dos

ambientes

de

inova¸cão

nos

resultados

de

P&D

La

influencia

de

los

ambientes

de

innovación

en

los

resultados

de

I+D

Serje

Schmidt

a,∗,

Alsones

Balestrin

b,

Raquel

Engelman

a,

Maria

Cristina

Bohnenberger

aaUniversidadeFeevale,NovoHamburgo,RS,Brazil

bUniversidadedoValedoRiodosSinos(UNISINOS),SãoLeopoldo,RS,Brazil

Received13April2015;accepted10May2016

Abstract

InBrazil,aswellasworldwide,incubatorsandscienceandtechnologyparks(ISTPs)arecontinuallyusedtofosterregionaldevelopment.However, theincongruencebetweenthegrowingnumberofISTPsandtheinconclusivenessoftheirresultsraisedpreoccupationsregardingtheireffectiveness anddoubtsonhowtheypromoteinnovation.Inspiteofthegrowingpossibilityandneedforquantitativeresearch,fewstudieshaveadoptedthis methodologicalperspective.TheobjectiveofthisstudyistoanalyzetheinfluenceofresourcespromotedbyISTPsontheresultsoftheirtenant’s R&Dprojects.Aquantitativecross-sectionaldesignwasusedinthisstudy.AhigherspecificityintheobservationandanalysisofISTPscontributed totheadvanceofliterature,sothatataxonomyofresourcespromotedbyISTPswasproposedandthekeyresourcesassociatedtoR&Dresults couldbeidentified.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords:Incubators;Scienceandtechnologyparks;Innovation;Resources

Resumo

NoBrasileno mundo,incubadoraseparquescientífico-tecnológicos(ISTPs)sãocontinuamente adotadosparafomentarodesenvolvimento regional.Entretanto,aincongruênciaentreocrescentenúmerodeISTPseainconclusividadedosseusresultadosmotivampreocupac¸õesquanto àsuaefetividadeesuscitamquestionamentossobrecomoocorreoprocessodeinovac¸ãonessesambientes.Apesardasindicac¸õesdacrescente possibilidadeenecessidadedepesquisasquantitativasparaoestudodesseshabitats,poucasinvestigac¸õesadotaramessaabordagem.Oobjetivo destetrabalhoéanalisarainfluênciadosrecursospromovidosporISTPsnosresultadosdeP&Ddasorganizac¸õesporeleshospedadas.Foi realizadaumapesquisaquantitativa,compostaporumlevantamentodecortetransversal.Omaiorgraudeespecificidadenaobservac¸ãoeanálise doambienteempíricocontribuiuparaoavanc¸odaliteraturanosentidodeproporumaestruturaparaclassificac¸ãodosrecursospromovidospelas ISTPseidentificarquetiposderecursosestãoassociadosaosresultadosdeprojetosdeP&D.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palavras-chave:Incubadoras;Parquescientífico-tecnológicos;Inovac¸ão;Recursos

Resumen

EnBrasilyenelmundo,incubadorasyparquescientíficosytecnológicos(IPCTs)soncontinuamenteadoptadosparafomentareldesarrollo regional.Sinembargo,laincongruenciaentreelcrecientenúmerodeIPCTsylainconclusividaddesusresultadosproducepreocupacionesen

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:serjeschmidt@gmail.com(S.Schmidt).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofDepartamentodeAdministrac¸ão,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸ãoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeSãoPaulo –FEA/USP.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2016.07.004

cuantoasuefectividadycuestionessobrecómoocurreelprocesodeinnovaciónenestosambientes.Aunquehayaindicacionesdequeestudios cuantitativossonposiblesynecesariosparaeladecuadoanálisisdeIPCTs,enpocostrabajosseadoptóesteabordaje.Elobjetivoenesteartículoes examinarlainfluenciadelosrecursospromovidosporIPCTsenlosresultadosdeI+Ddelasorganizacioneshospedadas.Sellevóacabounestudio cuantitativoconanálisisdesesgo.Elmayorgradodeespecificidadenlaobservaciónyanálisisdelambienteempíricocontribuyealavancedela literaturaenelsentidodeplantearunaestructuraparaclasificacióndelosrecursosdeIPCTseidentificarquétiposderecursosestánrelacionados conlosresultadosdeproyectosdeI+D.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteesunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palabrasclave: Incubadoras;Parquescientíficosytecnológicos;Innovación;recursos

Introduction

The development of incubators and science and technol-ogyparks(ISTPs) asmechanismsofpromotionofinnovation emergedintheSiliconValleyandRoute128inBostoninthe 1970s(Lahorgue,2004)andcontinuestoinspiresimilar initia-tivesaroundtheworld.TheInternationalAssociationofScience Parks (IASP) defines a science and technology park as “an organizationmanagedbyspecializedprofessionals,whosemain aim istoincreasethe wealthof its communitybypromoting thecultureofinnovationandthecompetitivenessofits associ-atedbusinessesandknowledge-basedinstitutions”.1In Brazil andaroundtheworld,ISTPshavecontinuallybeenadoptedas mechanismsforregionaldevelopment.

However,thefeaturesrelatedtotheidentityofthesehabitats and the results of their institutional objectives bring uncer-tainties.Researchers questionnot onlythe fact that thereare professionalswhoareexpertintheirmanagement(Westhead&

Batstone,1999),butalsotheproductionofinnovations(Lee&

Yang,2000;Radosevic&Myrzakhmet,2009;Westhead,1997).

WhilesomestudiesindicatesignificantcontributionsofISTPs fortheinnovationofbusinesses(Lee&Yang,2000;Lindelof&

Lofsten,2003;Squicciarini,2009;Tan,2006;Yang,Motohashi,

& Chen, 2009); other ones have not confirmedthis

proposi-tion (Chan, Oerlemans, & Pretorius, 2010; Massey, Quintas,

& Wield,1992; Radosevic & Myrzakhmet, 2009; Westhead,

1997).Conflictingresultscanalsobeobservedinotherrelated dimensionssuchasknowledge,learningandsynergybetween thecompanies.Massey,Quintas,andWield(1992)areespecially skepticalabouttheroleofISTPsinthesocioeconomic devel-opmentin someregionsof the UnitedKingdom. They argue that public policies that supportthese institutions are deeply problematic.Theseauthorssuggestthattheparksresultin frag-mented social structures, distorted economic and geographic developmentandeventechnologicalstagnation. These uncer-taintiesleadsomeauthors(Lahorgue,2004;ex.:Masseyetal., 1992)toproposethattheinstitutionaljustificationfortheir pro-liferationismimeticisomorphism(DiMaggio&Powell,1983) –or“fads”.Anotherexplanationforthismayberelatedto dif-ferentunderstandingswithregardstotheroleofISTPsandto theresultingmanagementmodelsthatarechosen.

Theincongruitybetweenthegrowingnumberofincubators andSTPsinthe worldandthe inconclusivenessof empirical

1 Extractedfromhttp://www.iasp.ws/.AccessedonJune1st,2016.

researchesmotivatesconcernsabouttheirsustainabilityandthe questioning about how the process of innovation happens in theseenvironments.Admittingthatgeneratinginnovationis fun-damentaltotheeconomicdevelopmentofregionsandthatISTPs are apotentialwaytopromoteregionaldevelopmentthrough innovation, theseinstitutionsshould– intheory– fulfill their role. Thus,althoughthe literaturedealsvery thoroughlywith the innovationbackgroundinseveralempirical environments, thecontributionofISTPsfororganizationalinnovationstilllacks aclearerdirection.Theseinnovationhabitatsarepermeatedby institutionalelementswhoseeffectsmayberelatedlessdirectly toinnovation,suchasculture,trust,willingnesstocollaborate, andothers(Hwang&Horowitt,2012).

Inacademicenvironments,casestudieshavepredominatedas amethodologicalapproach,butfewstudiesproposedtoexamine ISTPs quantitatively, despite indicationsof the growing pos-sibility(Etzkowitz&Leydesdorff,2000)andneed(Balestrin,

Vargas,&Fayard,2005)ofquantitativestudies.Amongthese,

thecomparisonbetweenbusinessesthatareinternalandexternal to these environments, assuming the homogeneity of inter-nal resources amongISTPs, dominates as anepistemological conception.Theidiosyncrasiesofthesehabitats,however, con-tradict this assumption, which, added to the difficulties of obtaining internal and external samples that are statistically comparable,leadstotheneedfornewapproaches.

This researchaims, through aquantitative survey, to con-tribute to the study of the innovation background in these environments, consideringtheinfrastructureandservices pro-moted by ISTPs as resources that facilitate the researchand developmentof newproductsandservices.In otherwords, it is not onlysufficient that the incubators and STPsexist and accommodatebusinessesfortheR&Dprocesstotakeplaceand produceinnovation.Thereareactionsthatmustbedevelopedin orderforthistohappen,suchasfacilitatingaccessto collabora-tion andresearchsupportmechanisms,promotingappropriate environmentsforsocialexchanges,amongothers.

The overall objective of this study is to analyze how the resources promoted by ISTPs influence the R&D results of organizationshostedbytheseenvironments.Therefore,amore specificlevelofanalysisisadoptedthaninpreviousquantitative studies,thussupplementingthoseandstimulatingthedebateon ISTPs,inordertounderstandthemasactivedevelopersofthe innovationprocess.

canprioritizeareasofactiontoencourageR&Dprocesses,such as seekinganddisseminatingcalls for proposals for funding, orgettingclosertothecompaniesinordertobetterunderstand theirexistingskills.Universities,whichsometimesactas man-agersof these habitats, can guide the allocation of teachers, researchersandstudentstothecompanies.Companiesmay con-ductthesearchfor mechanismstogeneratenewproducts and servicesbyselectingincubatorsorparksthatofferresourcesthat effectivelycontributetothisprocessordemandtheseresources fromtheenvironmentwheretheyarelocated.Thegovernment, inturn,canallocate public policies,for example,intheform ofcriteriaforgrantingfundstoinnovationhabitatsthatprovide accesstocertainresourcesforbusinesses.ProjectsofnewISTPs canconsidertheresultspresentedherefortheallocationofareas forsocialactivities,laboratoriesortechnicalandscientific train-ing.Ingeneral,thisresearchintendstocontributetotheactors involvedinthisprocesses.

Thisstudyisorganizedasfollows:anexplorationofliterature concerningtheinnovationbackgroundispresentedinthenext section.Themethodologicalproceduresusedtoobtaindataon theresourcespromotedbyISTPsandthosewithwhichweintend toverifythemodeldevelopedintheempiricalenvironmentare describedinthefollowingsection,followedbytheanalysisof theresultsandconclusions.

Innovationbackground

Theelementswhichfacilitateandthebarrierstoinnovation areconsiderableandhavebeenextensivelyexploredinthe lit-erature. In asummary of publications, Crossanand Apaydin

(2010) explored the innovation determinants, grouping them

intothreedistincttheoreticalmeta-constructs:innovation lead-ership,manageriallevelsandbusinessprocesses.Eachofthese constructscanbesustainedbyadifferenttheory:theinnovation leadershipby theupper echelontheory (Hambrick&Mason, 1984),themanageriallevelsbythedynamiccapabilitiestheory

(Teece,Pisano,&Shuen,1997)andthebusinessprocessesby

theprocesstheory(VanDeVen&Poole,1995).Theinnovation determinants,accordingtotheauthors,leadtoinnovationboth asaprocessandas anoutcome.The firstandthethird meta-constructswillbebrieflydescribedbelowinordertoprovidea betteradhesiontotheobjectofstudyinquestionandthe pro-posedlevelofanalysis,followedbythemanagementstrategies andthedynamiccapabilitiestheory.

The determinants of innovation related to the upper ech-elon theory were grouped by Crossan and Apaydin (2010)

in:individual (CEO)andgroup(Top ManagementTeam and Board Governance). At the individual level, factors such as tolerance of ambiguity, self-confidence, openness to exper-imentation, independence, proactivity, among others, were identified as determinants of organizational innovation. At the top management team level, the following factors were related:diversity of backgroundandexperience of the group members,tieswithorganizations inotherindustries,the edu-cational level, among others. At the board governance level, elements such as board diversity, the proportion of directors fromotherindustriesandinstitutionalshareholdingincorporate

the innovation determinants. In a review of the Hambrick and Mason’s original study (1984), published twenty years later,Carpenter,Geletkanycz,andSanders(2004)suggestthat innovation is still a strategic choice resulting from cogni-tive characteristics and values provenient from the strategic level.

Atthebusinessprocesseslevels,CrossanandApaydin(2010)

emphasizetheimportanceofunderstandingthemeaningofthe term“process”.Amongitspossiblemeanings,theauthors under-standthatitis“acategoryofconceptsoforganizationalactions, suchas ratesofcommunication,workflows,decisionmaking techniquesormethodsstrategycreation”(Crossan&Apaydin, 2010,p. 1173).Thetheory of organizationalprocesses advo-catesthatifsimilarinputsprocessedbysimilarprocesseslead tosimilaroutcomes,thentherearecertainconstantsand neces-saryconditionsfortheoutcomestobeachieved.Itispossible thatthisunderstandingexcuses,inaway,thesystemicand non-linearcharacterofinnovation,asdiscussedabove.Theanalysis categoriesthatconstitutethisconstructrepresentthemain pro-cessesthatresultininnovation.Theseprocessesweregrouped bytheauthorsasfollows:initiationanddecision(recognitionof theneedtoinnovateandthedecisionrelatingtothis), develop-mentandimplementation,portfoliomanagementforinnovation, project management and commercialization. van der Borgh,

Cloodt,andRomme(2012)usedtheProcessTheory(VanDe

Ven&Poole,1995)asthebasisforinidentifyingstandardsfor

valuecreationinbusinessecosystems.Theauthorsconcluded that ecosystemsfacilitatetheinnovation processinindividual organizationsandcreateinnovationcommunities.VanderBorgh

et al. (2012) also stress the contribution of the study to the

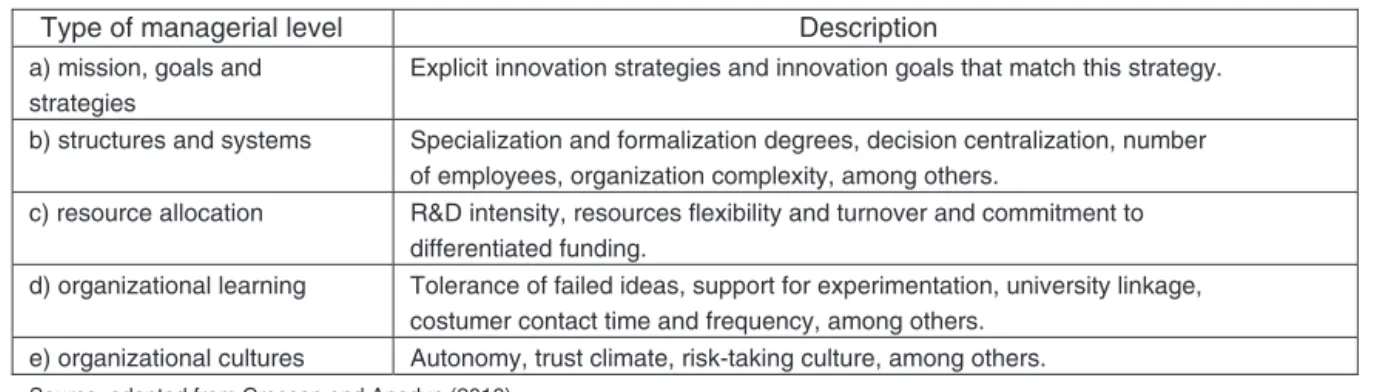

understandingofinnovationenvironments,suchasISTPs. Thedynamiccapabilities(Teeceetal.,1997),whichbacks the theoretical meta-construct relating tothe managerial lev-els,analyzes theinnovationatthefirmlevelandoriginatesin adynamicstrainoftheresource-basedview(Barney,1991).It applies,therefore,totheanalysisofinnovationresourcesatthe firmlevelandprovidesapossibilityofaconsistenttheoretical frameworkforanalyzingtheroleofISTPsregardinginnovation intennantcompanies.ThisconstructwassubdividedbyCrossan

andApaydin(2010)infivetypesofmanageriallevels,asshown

inFig.1.

CrossanandApaydin(2010)report,amongtheresultsoftheir

meta-analysis,thatstudiesdedicatedtoexploringinnovationas aprocessdo notverify their impactoninnovation outcomes, mainlyexploringtheoveralloutcomeofthefirmasadependent variable.Ontheotherhand,researchesthattreatinnovationasa resultbringtothescrutinydistinctindependentinnovation vari-ables.Forexample,thedynamiccapabilitiestheory(Teeceetal., 1997)wasexploredintheempiricalfieldbyLichtenthalerand

Lichtenthaler(2009)inacasestudyofRolls-Royce.Theauthors

Description Type of managerial level

a) mission, goals and strategies

Explicit innovation strategies and innovation goals that match this strategy.

Specialization and formalization degrees, decision centralization, number b) structures and systems

of employees, organization complexity, among others.

R&D intensity, resources flexibility and turnover and commitment to c) resource allocation

differentiated funding.

Tolerance of failed ideas, support for experimentation, university linkage, d) organizational learning

costumer contact time and frequency, among others. Autonomy, trust climate, risk-taking culture, among others. e) organizational cultures

Source: adapted from Crossan and Apadyn (2010)

Fig.1.Managementlevelsforinnovation.

Source:AdaptedfromCrossanandApaydin(2010).

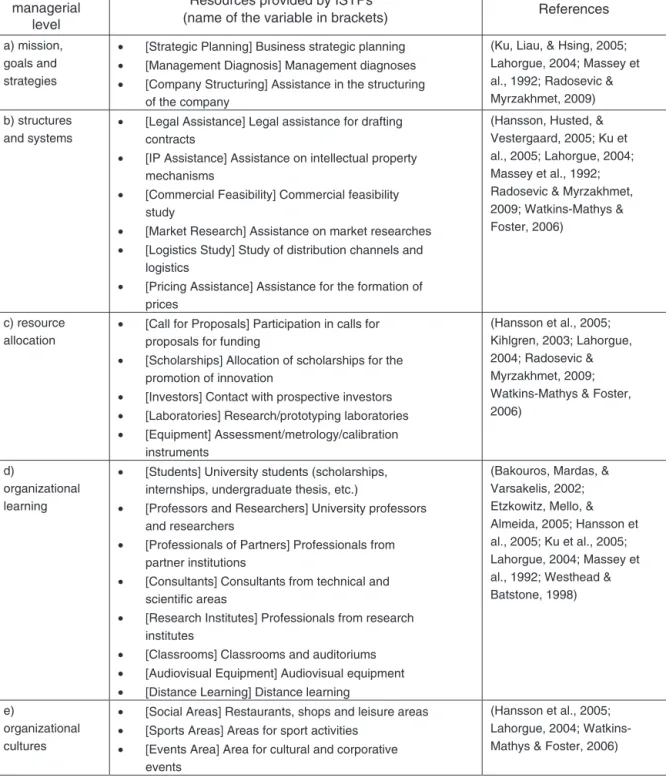

Themanageriallevelsapproachseemsmoreappropriateto thestudyproposedhere,asinnovationisanalyzedatthe organi-zationallevelandinasystematicway,fromthecontextinwhich theorganizationsarelocated.Thus,boththetheoryofstrategic levels,whichadoptsamoreindividualperspective,asthetheory oforganizationalprocesses,whichisbasedonalinear assump-tion,loserelevance.TheresourcespromotedbyISTPs,namely, theirservicesandinfrastructure,wereclassifiedaccordingtothe typesofmanageriallevels.Next,inthesectiononthemethodsof thisresearch,thewaythisclassificationhasoccurredandother proceduresadiptedinthisstudywillbedescribed.

Methods

Thisresearchischaracterizedasquantitative,consistingof across-sectional survey. Asthe literature on ISTPsdoes not classifyor organize the resourcesprovided bythese environ-mentsinasystematicway,apreliminarysurveywasperformed so astolist andclassifythem.Booksandnational and inter-national journals whichhave with incubators or science and technologyparksasobjectsof studywereconsidered, aswell as the websites of several Brazilian ISTPs. The keywords usedinthedatabasesEBSCO,ScienceDirectandScielo were extractedfrom thoseappointed by the IASP as synonyms of TechnologicalParks.Thesearchtermswere:“SciencePark(s)”, “Technology Park(s)”, “Technopolis”,“Technopole”, “Tech-nologyPrecinct” and “Research Park(s)”or their respective Portugueseterms.Inthesepapers,wesoughttoidentifythe ser-vicesandinfrastructurepromotedorfacilitatedbyISTPstothe tenantcompanies,categorizingthemaccordingtothe manage-riallevelsproposedbyCrossanandApaydin(2010).Thesearch wasstopped whentheservices andinfrastructurewhichwere foundbecameredundantinrelationtothelistthathadalready beenobtained,providingthecompletenessofthesurvey. Refer-ralstoservicesandinfrastructurewereanalyzed,summarized andorganized,resultingintheresourcesdepictedinFig.2.

Thefollowingtext,exposedinthequestionnairebeforethe resource list (Fig. 2), guided the answers: “Please indicate howmuchthefactofbeinglocatedintheincubator/park con-tributed to the access to these resources”. An ordinal scale of four points was on the right of each resource for the answers.Theoptionswere:“notapplicable”=null,0=“didnot

help”, 1=“contributed a little”, 2=“contributed reasonably” and3=“contributedalot”.

The dependent construct wasexplored inordertoaddress the results of innovation projects conducted by tenant com-panies.ThisvariablewasadaptedfromBlindenbach-Driessen,

VanDalen,andVanDenEnde(2010)withthefollowing

mea-surementitems:(a)“Thisprojectfullymettheexpectationsof ourcompany”;(b) “Theprojecthasresultedinnewproducts, servicesor processes”;(c)“Ourcompanyhasgained compet-itivenesswiththe resultof thisproject”; (d)“Theproject has contributedgreatlyourcorporateimage”;(e)“Wehavehadgreat financial resultswiththisproject”;and(f)“Wehave internal-izedalotofknowledgefromthisproject”.Thescaleusedfor theanswerwasafive-pointLikertscale,rangingfrom“Strongly Disagree”to“StronglyAgree”withoutanoptionofnullanswer, whichhasforcedtherespondenttotakeapositiononeachitem. The answers were oriented tothe managers of innovation projects of tenantcompanies, ratherthan tothe managers of ISTPs.Thiswasadoptedasameasuretopreventpossible com-monmethodbiases(Podsakoff,MacKenzie,Lee,&Podsakoff, 2003).Theaverageoftheanswerswasattributedtothe inno-vationenvironmentinwhichthebusinessislocated.Thedata collectionprocessbeganwiththeprocurementofalistofISTPs onthewebsiteoftheNationalAssociationofEntitiesPromoting InnovativeEnterprises(ANPROTEC–Associac¸ãoNacionalde EntidadesPromotorasdeEmpreendimentosInovadores).Each ofthe269incubatorsandparkswerecontactedbytelephoneand askedtoprovidealistoftenantcompanies.Thisprocessresulted inadirectoryof1004companies.Eachcompanywasalso con-tactedbyphoneandthepersonresponsiblefortheR&Dprojects wasinvitedtoparticipateinthesurveybyprovidingtheir per-sonal. Only6%oftheinviteesdidnotagree toparticipate.A previousnoticeconfirmingacceptancewassentfollowedbyan email afewdayslaterwiththe onlinesurveylink.Morethan half (61%)oftheemailssentresultedineffectivelyanswered questionnaires,withatotalof264respondentsfromtenant com-panies.ComputingtheaverageforeveryISTP,atotalsampleof 84ISTPswasachieved.

Resultsanddiscussion

Type of managerial

level

Resources provided by ISTPs

(name of the variable in brackets) References

a) mission, goals and strategies

• [Strategic Planning] Business strategic planning • [Management Diagnosis] Management diagnoses • [Company Structuring] Assistance in the structuring

of the company

(Ku, Liau, & Hsing, 2005; Lahorgue, 2004; Massey et al., 1992; Radosevic & Myrzakhmet, 2009) b) structures

and systems

• [Legal Assistance] Legal assistance for drafting

contracts

• [IP Assistance] Assistance on intellectual property

mechanisms

• [Commercial Feasibility] Commercial feasibility

study

• [Market Research] Assistance on market researches • [Logistics Study] Study of distribution channels and

logistics

• [Pricing Assistance] Assistance for the formation of

prices

(Hansson, Husted, & Vestergaard, 2005; Ku et al., 2005; Lahorgue, 2004; Massey et al., 1992; Radosevic & Myrzakhmet, 2009; Watkins-Mathys & Foster, 2006)

c) resource allocation

• [Call for Proposals] Participation in calls for

proposals for funding

• [Scholarships] Allocation of scholarships for the

promotion of innovation

• [Investors] Contact with prospective investors • [Laboratories] Research/prototyping laboratories • [Equipment] Assessment/metrology/calibration

instruments

(Hansson et al., 2005; Kihlgren, 2003; Lahorgue, 2004; Radosevic & Myrzakhmet, 2009; Watkins-Mathys & Foster, 2006)

d)

organizational learning

• [Students] University students (scholarships,

internships, undergraduate thesis, etc.)

• [Professors and Researchers] University professors

and researchers

• [Professionals of Partners] Professionals from

partner institutions

• [Consultants] Consultants from technical and

scientific areas

• [Research Institutes] Professionals from research

institutes

• [Classrooms] Classrooms and auditoriums • [Audiovisual Equipment] Audiovisual equipment • [Distance Learning] Distance learning

(Bakouros, Mardas, & Varsakelis, 2002; Etzkowitz, Mello, & Almeida, 2005; Hansson et al., 2005; Ku et al., 2005; Lahorgue, 2004; Massey et al., 1992; Westhead & Batstone, 1998)

e)

organizational cultures

• [Social Areas] Restaurants, shops and leisure areas • [Sports Areas] Areas for sport activities

• [Events Area] Area for cultural and corporative

events

(Hansson et al., 2005; Lahorgue, 2004; Watkins-Mathys & Foster, 2006)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Fig.2.ManageriallevelsforinnovationandresourcesprovidedbyISTPs.

Source:Compiledbytheauthors.

southeastregionsofBrazil.Thisconcentration,however,seems toberelativelyproportionaltothedistributionofANPROTEC membersintheseregions,suggestingthatthesampleis consid-erablyrepresentativegeographically.

For the data analysis, the developed constructs were first testedfor their validity and reliability inorder toidentify to whatextendthedataofthevariablesobtainedintheempirical environmentreallymeasuretherespectiveconstructs.Sincethe independentvariablesarenotconstitutedofconstructsthathave

alreadybeendevelopedandvalidatedintheliterature,theywere analyzedbyexploratoryfactoranalysis(EFA).

Table1

GeographicprofileoftherespondentsandofANPROTECmembers.

Region State Respondents ANPROTECmembers

N.Businesses % N.ISTPs % N.ISTPs %

North Amapá 2 0.8 1 1.2 2 0.7

Amazonas 12 4.5 2 2.4 4 1.5

Pará 1 0.4 1 1.2 6 2.2

Sum 15 5.7 4 4.8 12 4.5

Northeast Alagoas 4 1.5 2 2.4 8 3.0

Bahia 2 0.8 1 1.2 3 1.1

Ceará 6 2.3 3 3.6 7 2.6

Paraíba 1 0.4 1 1.2 7 2.6

Pernambuco 2 0.8 1 1.2 8 3.0

RioGrandedoNorte 3 1.1 1 1.2 4 1.5

Sum 18 6.8 9 10.7 37 13.8

Midwest DistritoFederal 7 2.7 1 1.2 5 1.9

Goiás 2 0.8 1 1.2 6 2.2

MatoGrossodoSul 1 0.4 1 1.2 7 2.6

Sum 10 3.8 3 3.6 18 6.7

Southeast EspíritoSanto 2 0.8 2 2.4 5 1.9

MinasGerais 29 11.0 12 14.3 28 10.4

RiodeJaneiro 24 9.1 8 9.5 29 10.8

SãoPaulo 48 18.2 19 22.6 58 21.6

Sum 103 39.0 41 48.8 120 44.6

South Paraná 20 7.6 6 7.1 27 10.0

RioGrandedoSul 62 23.5 14 16.7 34 12.6

SantaCatarina 36 13.6 7 8.3 21 7.8

Sum 118 44.7 27 32.1 82 30.5

Total 264 100.0 84 100.0 269 100.0

Source:Compiledbytheauthors.

rotatedbytheVarimaxmethodreturnedalatentdatastructure thatcanbecomparedtothatproposedbyCrossanandApaydin

(2010)onthetypesofmanageriallevels.

Table2showssimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthe

empir-icaldataandthestructureofthemanageriallevelsproposedby

CrossanandApaydin(2010).Itispossiblethatthedifferences

observedarerelatedtotheenvironmentinwhichtheoriginal structure had been proposed. On the one hand Crossan and

Apaydin(2010)suggestthattheinnovationbackgroundcomes

fromarangeofinternalresourcesoftheorganization.Onthe otherhand,thegoalherewastostudytheinnovationbackground relatingtoISTPs,referring notonlytointernalresources,but alsotothecomplementaryresourcesprovidedbythesehabitats. The dependent constructwas not included inthe exploratory factoranalysis,asitsconceptionisnotablydistinguishedfrom independentconstructs.Itsinclusionwouldinfluencethefactor loadingofotherconstructs,artificiallyinflatingtheconvergent anddiscriminantvalidities ofthe model.Thus,for parsimony issues, EFA was only performed with the independent con-structs.

Observingtheobtainedfactorloadingsandanalyzingthem in relation to the model proposed by Crossan and Apaydin

(2010),itispossibletodelineateanunderlyingstructureof

ser-vicesandinfrastructurethat correspondstothe dataobtained and that can be furthervalidated in other samples. The first EFA component converges withvariables relatedtothe allo-cation of human resources to assist the tenant companies in relation to various areas of management. Thus, both strate-gic managerial levels andthose concerning the structure and

Table2

RotatedEFAmatrix.

Typeofmanageriallevel Variable Components

1 2 3 4 5

StrucSist Marketresearch 0.873

Strat Strategicplanning 0.851

StrucSist Pricingassistance 0.849

Strat Managementdiagnosis 0.838

StrucSist Commercialfeasibility 0.836

StrucSist Logisticstudy 0.771

Strat Structuringofthecompany 0.734

Learn Consultants 0.696 0.369

StrucSist Legalassistance 0.656 0.305

Learn Classrooms 0.890

Learn Audiovisualequipment 0.755 0.379

Culture Areasforevents 0.311 0.722 0.302

Resources Investors 0.430 0.520 0.402

Resources Callforproposals 0.882

Resources Scholarships 0.855

Learn Students 0.625 0.440

Culture Socialareas 0.857

Culture Sportsareas 0.819

Resources Equipment 0.556 0.374

Resources Laboratories 0.396 0.411 0.446

Learn Professorsandresearchers 0.360 0.825

Learn Researchinstitutes 0.350 0.782

Extractionmethod:analysisofmaincomponents. Rotationmethod:VarimaxwithKaisernormalization.

Obs.:forlegibilityquestions,onlyfactorloadingshigherthat0.3orlowerthan−0.3arepresentedinthetable.

Thevariableswerethenregroupedaccordingtoeach result-ing EFAcomponent toform the constructsfor analysis. The fourvariableswiththehighest factorloadingineach compo-nentwereused.TheconstructswerethenspecifiedinaPartial LeastSquares(PLS)model.

AstheStructuralEquationModeling(SEM),thePLSallows theuse of multipledependent andmultipleindependent con-structs.Inthistechnique,smallersamplescanbeused,andthere islesssensitivetomulticollinearityandlowmultivariate nor-mality.Thus,itismoresuitableforexploratoryresearch.One ofthedrawbacksinusingPLSisthedifficultyof interpreting theloadingsofindependentconstructs,astheyarenotbasedon factorloadingsandtheirdistributionpropertiesarenotknown

(Garson,2012).Nevertheless, PLSseemedsuitable, givenits

adherencetothepurposesofthepresentstudyandtotheprofile ofthecollecteddata,andwasadoptedtocarryouttheanalysis.

Hair,Sarstedt,Ringle,andMena(2012),inareviewoftheuse

ofPLSinmarketingstudies,usedageneralruleforthesample sizeforthistechnique,whichthesampleshouldbegreateror equaltotentimesthenumberofpathsthatpointtoanyconstruct oftheoutermodel(numberofformativevariablesperconstruct) andoftheinnermodel(numberofpathsdirectedtoaspecific construct).Hairetal.(2012)indicatethat93.39%ofmarketing studiespublishedsince2000inqualifiedjournalsmeetthisrule, inwhichthepresentresearchalsofits.ThePLSmodelisshown inFig.3.

Themodelcalculationreturnedtheindicatorsofvalidityand reliabilityoftheconstructsshowninTable3.

Management assistance

Learning

Financial resources

R&D and socialization

R&D results

Specialized human resources

Fig.3.PLSmodel.

Table3

AdjustmentindicatorsofthePLSmodel.

Cronbach’s alpha (>=0.6)

Composite reliability (>=0.6)

Average variance extracted (>=0.5)

Managementassistance 0.888 0.916 0.733

Learning 0.801 0.722 0.498

Financialresources 0.801 0.872 0.635 R&DandSocialization 0.736 0.691 0.434

SpecializedHR 0.775 0.899 0.816

R&Dresults 0.806 0.873 0.632

Source:SmartPLSoutput.

Note:levelsofacceptanceaccordingtoHairetal.(2009).

Table4

Pathcoefficientsandtvalues.

Construct Pathcoefficient tvalue

Managementassistance −0.095 0.922

Learning 0.037 0.338

Financialresources 0.355 3.370

R&Dandsocialization 0.029 0.391

SpecializedHR 0.005 0.067

Source:SmartPLSoutput.

AfterassessingtheadjustmentofthePLSmodel,the relation-shipbetweentheconstructsoughttobeanalyzedforsignificance values.In thissense,Garson (2012)proposes that the signif-icance level can be calculatedusing the bootstrap algorithm, whichresultsinvalues forthe t-testof the proposed correla-tions.Thetvaluesshouldbegreaterthan1.96tobeconsidered significant.Theseresultsareshownintable4.

Financial resources were significantly associated with the resultsofR&Dprojects.Theseresourcesrefertotheassistance of the incubatoror parkinobtaining scholarships, participat-ing inprocessesfor funding andaccessing investors,andare appointedbytheliteratureasoneofthekeyelementsthat sup-port innovation, particularly inregards to high-tech start-ups

(Lahorgue,2004;Watkins-Mathys&Foster,2006).Thefindings

ofthisstudycorroboratetheliteratureinthisregard.Radosevic

andMyrzakhmet(2009)mentionthe accesstoexternal

fund-ing sourcesandthe low rentpaid bytenants as apretext for theirlocationinISTPs,whichcomplementsthefinancial moti-vationargumentforinnovation.Ontheotherhand,theliterature alsoindicateslimitationsthatareworthmentioning.Westhead

(1997),for instance,suggeststhat the expenditure of

compa-niesonR&D inparksbearsnorelationtoinnovation results,

andNegassi(2004)statesthatpublicfundingforinnovationand

collaboration produceless resultsthan privatefunding, argu-ingthatpublicfundingistargetedtolowprofitabilityareasand, therefore,haslowinterestfromprivateinvestors.Possibly,these limitationsarerelatedtothefactthatthereasonsthatdrive com-paniestoparticipateinR&Dprojectsaremoreassociatedwith theinternalizationoffinancial resourcesthantoinnovationor competitiveness(Kihlgren,2003).

Thecallforproposalsforfundingoriginatedfrominnovation environmentsandtheparticipationofcompaniesinthesecases

may induce the allocation of technical andscientific compe-tences,R&Dinfrastructureandfinancialresourcesforfunding R&D processes.Oncethe project issubmittedandapproved, teachers and researchers are allocated, laboratories are built andscientificequipmentispurchased.Thus,thekeyactorsof the processplayspecificrolesneededfor aninnovation strat-egy, within a Triple Helix model (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000):whilethegovernmentinducescontractualrelationships that contribute tostable interactions toexchange knowledge, the university acts as asource of knowledge and technology and industry is constituted as the locus for technology pro-duction.The inductionof collaborative R&Dprojects, inthis sense,wouldnotbeperformeddirectlybyinnovationhabitats, butinstitutionallybypublicpoliciesorientedtoinnovation.

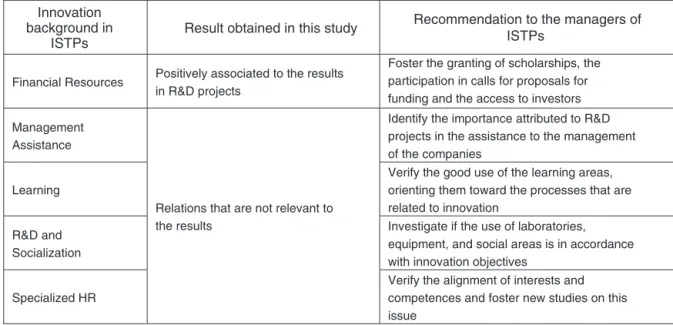

The absence of significant connections amongother inde-pendentconstructsandthedependentconstructpoints,inpart, toward the permanence of ambiguity that has already been addressed in the literature and exposed in the introduction. Assistancetomanagement,learning,R&Dandsocializationand specialized HRwerenotsignificantlyrelatedtothe resultsof R&Dprojects.Eachoftheseconstructsisdiscussedbelow.

Management Assistance: possibly,the effortsof ISTPsto assist the management of incubatedbusinessesor tenants are broader,coveringmarketissues,strategicplanning,and logis-tics,amongothers.Althoughinnovationisoftenaddressedasa strategicissue,innovationprojectsmaynothavebeenincluded inthisassistance.

Learning:theresourcesthatcontributetolearningare basi-cally constitutedof physical infrastructureresources (rooms, areasfor events, etc.).In thesurveyed ISTPs, theseareasare possiblynotbeingusedatallor,iftheyare,theirusemaynot have been related toinnovation processes. Thishappens, for example,whentheseresourcesareemployedincoursesinthe areasofmanagement,intellectualproperty,etc.

R&D andSocialization: thisconstructincludesboth those variablesthatseemtobeindirectlyrelatedtoinnovationsuchas socialareasthatfacilitateproximityandcollaborationamongthe actors,asthosethatcontributemoredirectlytothegenerationof newproductsandservices,suchasequipmentandlaboratories. Both the first andthe latterare constitutedof physical infra-structureelementsanddependonthehowtheyareusedsoasto generateinnovation.Astheydonotpresentasignificantrelation withtheresultsofR&Dprojects,theseresourcesarepossibly notbeingusedforthepurposeoffacilitatinginnovation.

SpecializedHR:professors, researchersandresearch insti-tutesprofessionalsareincludedhere.Thefacilitatedaccessto theseprofessionalsshould,intheory,contributedirectlytothe resultsofR&Dprojects.Areasofallocatedprofessionalsmay not beadheringtothe demandsofthe companies,orthat the researchers’interestsaremorefocusedonscientificpublications thanontheproductionofinnovations.Thereasonsthatexplain whythisrelationwas notfoundinthe empiricalenvironment couldbethesubjectoffutureresearch.

Someofthe resultsobtained inthisstudy arecorroborated andsomeare contrarytothe onespresented intheliterature. Among the studiesthatdiffer fromthe results obtained here,

Innovation background in

ISTPs

Result obtained in this study Recommendation toISTPs the managers of

Financial Resources Positively associated to the results in R&D projects

Foster the granting of scholarships, the participation in calls for proposals for funding and the access to investors

Management Assistance

Relations that are not relevant to the results

Identify the importance attributed to R&D projects in the assistance to the management of the companies

Learning

Verify the good use of the learning areas, orienting them toward the processes that are related to innovation

R&D and Socialization

Investigate if the use of laboratories, equipment, and social areas is in accordance with innovation objectives

Specialized HR

Verify the alignment of interests and competences and foster new studies on this issue

Source: Compiled by the authors

Fig.4.Summaryofresults.

Source:Compiledbytheauthors.

nothaveahigherallocationofresearchersthancompaniesthat areoutsidetheISTPs.Bakouros,Mardas,andVarsakelis(2002)

alsoindicatesimilarresultsinGreece.Theseauthorspointout thatthethreeparksresearchedbythemdonotusetheallocation ofresearchersorthesharingofresearchlaboratoriesassynergy elementsforthedevelopmentofcompanies.

Othermore recentstudies, however,reinforce the benefits of the allocation of university resources to R&D processes.

Hansson,Husted,andVestergaard(2005)suggeststhatthemain

differencebetweentraditionalparksandthe“secondgeneration” parks isthat the formerhasan emphasisonthe commercial-ization of the researches that are produced, while the latter emphasizestheproductionofmarketableresearch.Afterall,it istheentrepreneur,nottheresearcher,whoproducesinnovation

(Roberts,2005).LöfstenandLindelöf(2005)corroboratethis

issueinsuggestingthatspinoffsfromtheuniversitieshavemore difficultyinchannelingR&Dinvestmentsforbetterresultsthan company-originatedspinoffs.

Theresultsobtainedhereareinagreementwithalessrecent line of thought: the allocation of specialized HR to R&D projectsofcompanies,supportedbytherequiredphysicaland financial infrastructure, does not seemto contribute to R&D projects.Theaccesstotheseresourcesoutside ISTPsmaybe occurringatalevelthatisverysimilartotheinternal environ-mentof thesehabitats,thusannullingthedifferencesbetween them.

Fig.4summarizestheresultsdiscussedandtheguidancefor managersofincubatorsandscienceandtechnologyparks.

The results indicate that the influences of ISTPsin R&D resultsaddressedinthispaperarelimitedtoFinancialResources. Theconclusionsofthisresearchwillbeconstructedconsidered theseresults.Othervariablesorcharacteristicsofthose environ-mentsmaybeexploredandfacilitatefuturestudiesshouldalso beconsidered.

Conclusions

Therelationsbetweentheresultsfoundinthisstudyandwhat ispresentedintheliteraturearelimitedmainlybythedifferences inthelevelofanalysis,whichconfersanexploratorycharacter tothisstudy.Theobjectofanalysisinthisstudyiscomposedof theaccesstoservicesandinfrastructurefacilitatedbythe fact that the companiesare locatedininnovation habitats. On the otherhand,theliteraturedeals,mainly,withabroaderlevel,one that considers the incubator itselfor the parkas the research focus.ThestructureofmanageriallevelsproposedbyCrossan

andApaydin(2010)inthecontextofinnovationwasadaptedto

organizeandassociatetheresourcespromotedbyISTPstothe resultsofR&Dprojects.

Thegreaterdegreeofspecificityintheobservationand analy-sisoftheempiricalfieldproposedbythisresearchcontributedto theadvancementofliteratureinordertoproposeaframeworkfor classificationoftheresourcespromotedbyISTPsand,through aquantitativeapproach,identify whichtypesofresources are associatedwiththeresultsofR&Dprojects.

beconsidered.InGreece,forexample,Bakourosetal.(2002)

believethatthelowinnovationlevelsareduetothesmallsizeof thescienceandtechnologyparks,tothefactthattheyhavebeen implantedonlyrecentlyandtoapolicyforhostingcompanies thatistooopen,resultinginvery diversifiedcompaniesbeing acceptedastenantsintheseenvironments.InBrazil,Rauppand

Beuren(2009)alsoindicatelimitationsontheparticipationof

companies in R&D projects, in the sense that the access to researchers andthe exchange ofexperiences withother com-panieswerecitedasfacilitiesofferedbyincubatorsforaslittle as6.25%ofrespondents.Comparingtheseresultswithsuccess casestudies,asSiliconValley(Saxenian,1994)andothercases gatheredduringtheliteraturereview,institutionalvariablesmay infactberelatedtoR&Dprocesses.

Similarly,attheinter-organizationallevel,variablesthatare externaltothisresearch,asthedensityofthenetwork(Powell,

Koput, & Smith-Doerr, 1996), the diversity of businesses in

the sameinnovationenvironment, (Tötterman&Sten, 2005), thecognitivedistance(Nooteboom,VanHaverbeke,Duysters,

Gilsing,&van denOord, 2007),a historyof conflictamong

theauthors,thelackofreliabilityordifferencesofpower(Gray, 2008),thecriteriafortheselectionofcompanies(Bakourosetal., 2002)ortheservicesprovidedbythesehabitats,whichhavenot been addressed here, may also influence the results of R&D projects.

Atthe organizationallevel, it ispossiblethat coordination structuresfor R&Drelatedtomarket orhierarchy issuesgive theimpressionoflowertransactioncostsfortheactorsinvolved inthisresearchthanforintermediatestructuresbasedon col-laboration,whichwouldlimitthebenefitsofR&Dprojectsin clusters. Oakey(2007),for instance, comparesvarious forms ofclustersandtheirimpactontheR&Dmanagementinsmall high-tech companies.Basedonthis, the author indicatesthat theabilitytoworkinternallyinheavilyfocusedgroups,namely, inahierarchicalstructure,is the mainreasonfor the success relatedtoR&D of the companieslocated ininnovation envi-ronments,ratherthanthegeographicalproximityprovidedby thesehabitats. Evenif theinformal cooperationcanbe bene-ficial,the author states that the most important collaboration occursformallyinintenselycompetitivemarkets.Other orga-nizationalvariablessuch as legitimacy, reputation(Human&

Provan, 1997), skills in leading partnerships (Powell et al.,

1996),perceivedlossofcontrolorsupportorinternalconflicts

(Gray,2008)andabsorptivecapacity(Cohen&Levinthal,1990)

maybeinfluencingthecollaborativeR&Dprocess.Theresults seemtocorroboratethosefoundbyKihlgren(2003)inRussia:

ItseemsthatinRussiafirmsmightfindscienceparks attrac-tivenot becausethelocalscientificmilieuisimportantfor their operations,butbecause theseplaces offerarange of servicesandgoodqualityaccommodation.(Kihlgren,2003, p.75).

Inadditiontoorganizational,inter-organizationaland institu-tionallevels,thetemporaldimensionalsolendssubsidiestothe understandingoftheR&DprocessesinISTPs.Theshorttimeof existenceoftheseinnovationhabitatsinBrazilmaybe respon-siblefortheabsenceofmorefavorableinstitutionalconditions

thataredevelopedinthelongterm,asacultureofinnovation, predispositiontocollaboration,trust,amongothers.Thesemay influence,evenifindirectly,theresultsofinnovationprojects. Inaway,itispossiblethatBrazilianISTPsarestill“first gen-eration”.Asthisresearchmainlyencompassesnewbusinesses, buildingrelationalexperiencesthatsupporttheirreputationas toreduceuncertaintyamongpotentialpartners–andthat, there-fore,openspacefortrustamongthem–maybeincipient(Ahuja,

2000).Zollo,Reuer,andSingh(2002)suggestthatorganizations

thatlackrelationalexperiencesbenefitmorefromcapital-based partnershipssuchasjointventures.Thelongtimenormally nec-essaryforthistypeofpartnership,however,vis-à-visthesizeof thecompaniespresentinISTPsandthedynamicsessentialto R&Dprocessescanderailcapital-basedpartnerships.Hu,Lin,

andChang(2005)reinforcethispoint,suggestingthat

collabo-rationonSTPshappensoccasionally,ratherthancontinuously. Thisindicatestheneedfortemporarynetworkstopromote inno-vation.In thissense,the continuityof the relationshipallows theconstructionofarelationalexperiencethatupholdsthe rep-utationnecessary totheformationof newrelations (Axelrod,

1984;Powelletal.,1996).Thisrecursionprovidesachallenge

toinnovationinthesehabitats,especiallyforincubators,where thenecessarydynamicstoR&Dprocessesrequiresrelationsof amoretemporarycharacter.

Therefore,thelowrelationalexperienceinherenttofirmsin incubators, the relativelyrecentemergence of STPsin Brazil andthelowinterdependencenecessarytoR&Dprocessesmay indicate theexistence oflowerdensitynetworks. Abarrierto collaboration in R&D is noticed, whichsets asideany facil-itating elements present in these environments. The need to develop relationships with other firms to learn, foster skills anddevelopinnovation (Chesbrough,Vanhaverbeke,&West,

2006; Nooteboom, 2008) seemstofindinprevious relational

experiencesandreputation,preconditionsfortheirfulfillment. In additiontothe relational experience,the idiosyncrasies ofeachinnovationhabitatandthecomplexitywithwhich col-laborativeR&Dprojectsareformedanddeveloped(Etzkowitz,

Mello, &Almeida, 2005) mayindicate the existence of path

dependenciesandmakeitdifficulttocheckgeneralizable propo-sitionsthatexplainthesephenomena.AccordingtoEtzkowitz

etal.(2005),

the processismorecomplexthansimpleorganizationand technologytransfer.Thesameorganizationalmechanismcan play a completely different role ininnovation, depending upontheactor(s)thatpromoteitsintroductionandthe con-textinto whichit isintroduced.(Etzkowitzetal.,2005,p. 422).

The timedimension mayalso influence the perception of managersabouttheresultsofthesameR&Dprojects.Shouldthe resultsoftheseprojectseventuallybeconvertedintoinnovations inthefuture,theperceptionaboutthemwillbedifferent.Inthis analysis,financialresourcesmayhavebeentheexceptionasthey refertoprojectsfundedbythegovernment,whichgenerallyhave ashorterdeadlineforexecution.

theState.Fortheacademicfield, thisstudycontributestothe understandingofthecharacteristicsandresultsofISTPsby pro-vidingelementsthatstimulateanongoingdebate,constituting animportant steptowardthe understandingofthe innovation processintheseenvironments.

RegardingthemanagementofISTPs,itcangivesupportto theexecutivesbasedontheknowledgeabouttheresourcesand infrastructurethatenableamoreeffectivefosteringoftheresults ofR&Dprojects.Knowingthattheseresourcescanassist deci-sionsonwheretoconcentrateeffortsandhow incubatorsand parkscandesigntheirownstrategiesinordertopromotebetter managementpractices.Appliedindifferentculturalandsocial contexts,theoperationalizationoftheproposedframeworkcan assistinthecomparisonofdifferentinnovationhabitats.

In terms of public management, the proposed framework bringselementsforcreationanddevelopmentofISTPs poten-tially stimulating self-sustaining innovation processes and regionaldevelopment.Theresultsofthisstudycanguidepublic managementtoolstostimulatetheparticipationofcompanies, universitiesandISTPsinR&Dprojects.Moreover,the under-standingthat these environments caninfluence the results of theseprojectslaysonthemaninstrumentalperspective,sothat theseinstitutionalmechanismscanbeusedtofosterinnovation culturesanddevelopthepoorareasoftheseprocesses.

Companies,then,maydrawontheseresultstoselect innova-tionhabitatsthatarebettersuitedtotheirstrategicgoals.Services andinfrastructureofferedbyISTPsarenecessary,butnot suffi-cient,topromoteR&Dprocesses.Callsforproposalsforfunding inducebetterresultsinR&Dprojects,butinordertohave syn-ergyamongtheactors,othercharacteristicsofISTPswhichwere notcoveredinthisstudyarerequired.

Furthermore, inordertocontribute tothe advancement of literature,certainlimitationsshouldbeconsidered. Epistemo-logically, one should admit that the mere fact that IPCTs facilitateaccesstotheseresourcesdoesnotmeanthattheyare used,nor whetherthe use isappropriate. Onemust notethat themethodologicaloptionformeasuringtheeaseofaccessto resourcesprovidedbytheincubatororpark,insteadofitsactual use,wasadoptedduetotheunderstandingthatthisreflectsthe roleofIPCTsthisprocessmoreclearly, sincetheseresources areavailableandalsousedoutsidetheseenvironments.Atthe sametime,thequestionnairewouldbemoreeasilyunderstood byentrepreneurs.Thisoptionisclearlylimitedincasesinwhich theresourcesareavailablebutarenotusedorarenotused prop-erly.Thestartingpointwastheassumptionthatsuchcaseswould berare.Afterall,whywouldacompanybepartofanIPCTif nottohaveaccesstotheseresourcesandusethemintheir inno-vationprocess? Apparently, the resultsmake thisassumption worthyofanewchallengeinfuturestudies.

Anotherlimitationisthesamplesize.Searcheswithalarger sample size might assist the verification of the significance levels obtained in this study, eventually by using multivari-atestatistical methodsof amoreverifiable character,such as the Structural Equation Modeling. Furthermore, one cannot, fromtheresults,assumeacausalrelationshipbetweenthe con-structs,sincetheconditionsrelatingtothisarebeyondthescope of thisstudy.The considerationof theselimitations infuture

researchmaytobringsupplementalresultstothoseproduced here.

Finally,weconsiderthatthisworkhasresponded satisfacto-rilytotheproposedresearchhypothesisandthatitspropositions, results, difficulties and limitations encourage the search for newquestioninghorizons.Wehopetohavecontributedtothe advancement inthe understandingof thisempirical fieldthat stilllacksmoreconclusiveresults.

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

Ahuja,G.(2000).Thedualityofcollaboration:Inducementsandopportunities intheformationofinterfirmlinkages.StrategicManagementJournal,21(3), 317.

Axelrod,R.M.(1984).Theevolutionofcooperation.BasicBooks.

Bakouros,Y.L.,Mardas,D.C.,&Varsakelis,N.C.(2002).Sciencepark,ahigh techfantasy?AnanalysisofthescienceparksofGreece.Technovation,

22(2),123.

Balestrin,A.,Vargas,L.M.,&Fayard,P.(2005).Oefeitoredeempólosde inovac¸ão:umestudocomparativo.RAUSP–RevistadeAdministra¸cãoda UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,40(2)

Barney,J.B.(1991).Firmresourcesandsustainedcompetitiveadvantage. Jour-nalofManagement,17(1),99–120.

Blindenbach-Driessen, F., Van Dalen, J., & Van Den Ende, J. (2010). Subjectiveperformanceassessmentofinnovationprojects.Journalof Prod-uct Innovation Management, 27(4), 572–592. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ j.1540-5885.2010.00736.x

Carpenter,M.A.,Geletkanycz,M.A.,&Sanders,W.G.(2004).Upper ech-elonsresearchrevisited:antecedents,elements,andconsequencesoftop managementteamcomposition.JournalofManagement,30(6),749–778. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.001

Chan, K.-Y.A.,Oerlemans,L.A.G.,& Pretorius,M.W.(2010). Knowl-edge exchange behaviours of science park firms: the innovation hub case. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(2), 207–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09537320903498546

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (2006). Open innovation: Researchinganewparadigm.NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress. Cohen,W.M.,&Levinthal,D.A.(1990).Absorptivecapacity:Anew

perspec-tiveonlearningandinnovation.AdministrativeScienceQuarterly,35(1), 128–152.

Crossan, M.M., & Apaydin, M.(2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature.

Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1154–1191. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x

DiMaggio,P.J.,&Powell,W.W.(1983).Theironcagerevisited:Institutional isomorphismandcollectiverationalityinorganizationalfields.American SociologicalReview,48(2),147–160.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innova-tion: from National Systems and Mode 2 to a Triple Helix of university–industry–governmentrelations.ResearchPolicy,29(2),109–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(99)00055-4

Etzkowitz, H.,Mello,J.M.A.d.,& Almeida,M.(2005). Towards meta-innovationinBrazil:Theevolutionoftheincubatorand theemergence of a triple helix. Research Policy, 34(4), 411–424. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.011

Fornell,C.,&Larcker,D.F.(1981).Structuralequationmodelswith unob-servablevariablesandmeasurementerror:Algebraandstatistics.Journalof MarketingResearch,18(3),382–388.http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3150980 Garson,G.D.(2012).Partialleastsquares:RegressionandpathmodelingBlue

Gray,B.(2008).Interveningtoimproveinter-organizationalpartnerships.InS. Cropper,M.Ebers,C.Huxham,&P.S.Ring(Eds.),Theoxfordhandbook ofinter-organizationalrelations.OxfordPress:NewYork.

Hair,J.,Sarstedt,M.,Ringle,C.,&Mena,J.(2012).Anassessmentofthe use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research.JournaloftheAcademyofMarketingScience,40(3),414–433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Hair,J.F.,Jr.,Black,W.C.,Babin,B.J.,&Anderson,R.E.(2009).Multivariate dataanalysis((7ed.).USA:PrenticeHall.

Hambrick,D.C.,&Mason,P.A.(1984).Upperechelons:Theorganization asareflectionofitstopmanagers.AcademyofManagementReview,9(2), 193–206.http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amr.1984.4277628

Hansson,F.,Husted,K.,&Vestergaard,J.(2005).Secondgenerationscience parks:Fromstructuralholesjockeystosocialcapitalcatalystsofthe knowl-edgesociety.Technovation,25(9),1039–1049.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.technovation.2004.03.003

Hu,T.-S.,Lin,C.-Y.,&Chang,S.-L.(2005).Technology-basedregional devel-opmentstrategiesandtheemergenceoftechnologicalcommunities:Acase studyofHSIP,Taiwan.Technovation, 25(4),367–380.http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.technovation.2003.09.002

Human,S.E.,&Provan,K.G.(1997).Anemergenttheoryofstructureand outcomesinsmall-firmstrategicmanufacturingnetwork.Academyof Man-agementJournal,40(2),368–403.

Hwang,V.W.,&Horowitt,G.(2012).TheRainforest:TheSecrettoBuilding theNextSilicon.Regenwald.

Kihlgren,A.(2003).PromotionofinnovationactivityinRussiathroughthe creationofscienceparks:ThecaseofSt.Petersburg(1992–1998). Techno-vation,23(1),65.

Lahorgue, M. A.(2004). Pólos, Parques e Incubadoras. Brasilia: Anpro-tec/Sebrae.

Lee,W.-H.,& Yang,W.-T.(2000).Thecradleof Taiwanhightechnology industrydevelopment–HsinchuSciencePark(HSP).Technovation,20(1), 55.

Lichtenthaler, U., & Lichtenthaler, E. (2009). A capability-based frame-workforopeninnovation:complementingabsorptivecapacity.Journalof ManagementStudies,46(8),1315–1338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00854.x

Lindelof,P.,&Lofsten,H.(2003).Scienceparklocationandnew technology-basedfirmsinSweden–Implicationsforstrategyandperformance.Small BusinessEconomics,20(3),245.

Löfsten,H.,& Lindelöf,P. (2005).R&Dnetworksandproductinnovation patterns-academicandnon-academicnewtechnology-basedfirmson Sci-ence Parks. Technovation, 25(9), 1025–1037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.technovation.2004.02.007

Massey,D.,Quintas,P.,&Wield,D.(1992).Hightechfantasies:Scienceparks insociety,scienceandspace.London:Routledge.

Negassi,S.(2004). R&Dco-operation and innovation a microeconometric studyonFrenchfirms.ResearchPolicy,33(3),365–384.http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.respol.2003.09.010

Nooteboom,B.(2008).Learningandinnovationininter-organizational rela-tionships. In S.Cropper, M.Ebers, C. Huxham, & P. S. Ring (Eds.),

TheOxfordhandbookofinter-organizationalrelations.OxfordPress:New York.

Nooteboom,B.,VanHaverbeke,W.,Duysters,G.,Gilsing,V.,&vandenOord, A.(2007).Optimalcognitivedistanceandabsorptivecapacity.Research Policy,36(7),1016–1034.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.04.003

Oakey,R.(2007).ClusteringandtheR&Dmanagementofhigh-technology smallfirms:Intheoryandpractice.R&DManagement,37(3),237–248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2007.00472.x

Podsakoff,P. M.,MacKenzie,S.B.,Lee,J.-Y.,& Podsakoff,N.P.(2003). Commonmethodbiasesin behavioralresearch:Acriticalreviewofthe literatureandrecommendedremedies.JournalofAppliedPsychology,88(5), 879–903.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Powell,W.W.,Koput,K.W.,&Smith-Doerr,L.(1996).Interorganizational collaborationandthelocusofinnovation:Networksoflearningin biotech-nology.AdministrativeScienceQuarterly,41(1),116–145.

Radosevic,S.,&Myrzakhmet,M.(2009).Betweenvisionandreality: Promot-inginnovationthroughtechnoparksinanemergingeconomy.Technovation,

29(10),645–656.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.04.001 Raupp,F.M.,&Beuren,I.M.(2009).Programasoferecidospelasincubadoras

brasileirasàsempresasincubadas.RevistadeAdministra¸cãoeInova¸cão,

6(1),83.

Roberts, R. (2005). Issues in modelling innovation intense environments: Theimportanceofthehistorical andculturalcontext.Technology Anal-ysis&StrategicManagement,17(4),477–495.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 09537320500357384

Saxenian, A. (1994). Lessons from Silicon Valley. Technology Review (00401692),97(5),42.

Squicciarini,M.(2009).Scienceparks:seedbedsofinnovation?Aduration anal-ysisoffirms’patentingactivity.SmallBusinessEconomics,32(2),169–190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9075-9

Tan,J.(2006).Growthofindustryclustersandinnovation:LessonsfromBeijing ZhongguancunSciencePark.JournalofBusinessVenturing,21(6),827–850. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.006

Teece,D.J.,Pisano,G.,&Shuen,A.(1997).Dynamiccapabilitiesandstrategic management.StrategicManagementJournal,18(7),509–533.

Tötterman,H.,&Sten,J.(2005).Start-ups:Businessincubationandsocial capital. Incubación de Empresas y Capital Social, 23(5), 487–511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266242605055909

Van DeVen,A. H.,& Poole, M.S.(1995). Explaining development and changeinorganizations.AcademyofManagementReview,20(3),510–540. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080329

vanderBorgh,M.,Cloodt,M.,&Romme,A.G.L.(2012).Valuecreationby knowledge-basedecosystems:Evidencefromafieldstudy.R&D Manage-ment,42(2),150–169.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2011.00673.x Vedovello,C.(1997).Scienceparksanduniversity–industryinteraction: Geo-graphicalproximitybetweentheagentsasadrivingforce.Technovation,

17(9),491.

Watkins-Mathys,L.,&Foster,M.J.(2006).Entrepreneurship:Themissing ingredientinChina’sSTIPs?Entrepreneurship&RegionalDevelopment,

18(3),249–274.

Westhead,P.(1997).R&D‘inputs’and‘outputs’oftechnology-basedfirms locatedonandoffscienceparks.R&DManagement,27(1),45.

Westhead,P.,&Batstone,S.(1999).Perceivedbenefitsofamanagedscience parklocation.Entrepreneurship&RegionalDevelopment,11(2),129–154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/089856299283236

Yang, C.-H., Motohashi, K., & Chen, J.-R.(2009). Are new technology-based firmslocatedonscience parksreallymoreinnovative? Evidence from Taiwan. ResearchPolicy, 38(1), 77–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.respol.2008.09.001