0

FUNDAÇÃO GETÚLIO VARGAS EPGE

NATHALIE GRESSLER AFONSO

CARTEL DAMAGE EVALUATION:

A CASE STUDY ON THE LIQUEFIED PETROLEUM GAS CARTEL IN PARÁ, BRAZIL

Dissertação para obtenção do grau de mestre apresentada à Escola de Pós-Graduação em Economia FGV/EPGE

Área de concentração: Economia Empresarial Orientador: José Gustavo Féres

Rio de Janeiro

1

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV

Afonso, Nathalie Gressler

Cartel damage evaluation: a case study on the liquefied petroleum gas cartel in Pará, Brazil / Nathalie Gressler Afonso. – 2017.

84 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Fundação Getulio Vargas, Escola de Pós-Graduação em Economia.

Orientador: José Gustavo Féres. Inclui bibliografia.

1. Trustes industriais. 2. Gás liquefeito de petróleo. I. Féres, José Gustavo. II. Fundação Getulio Vargas. Escola de Pós-Graduação em Economia. III. Título.

3

AGRADECIMENTOS

Aos meus pais, pelo apoio, incentivo e amor incondicional durante todos esses anos, e pela oportunidade de cursar esse mestrado.

Às minhas irmãs e ao meu irmão, pelo carinho e o convívio, e à Marjorie, pela companhia nas horas de estudo.

A todos os professores de quem fui aluna no mestrado de Economia da Fundação Getulio Vargas, que foram tão importantes na minha formação acadêmica.

Ao meu orientador e Professor José Gustavo Féres por sua grande ajuda durante todas as etapas dessa dissertação. Por ter me ajudado a elaborar e desenvolver esse tema, pelas inúmeras reuniões para discussões de idéias e revisões. Sua ajuda foi imprescindível para a conclusão desse trabalho.

4

ABSTRACT

Collusive practices used by cartels have proven to be extremely harmful to economic efficiency and social welfare. Detecting these kind of practices has become a priority within antitrust agencies around the world. Regulators are constantly after effective ways to punish companies so that the costs of colluding outweighs its benefits. These punishments usually come in the form of fines or compensation payments that are calculated based on the estimated damages caused by the colluding firm. However, detecting cartel can pose a challenge to economists; it is a data intensive and time consuming process that involves estimating a competitive benchmark to compare with the suspected collusive behavior.

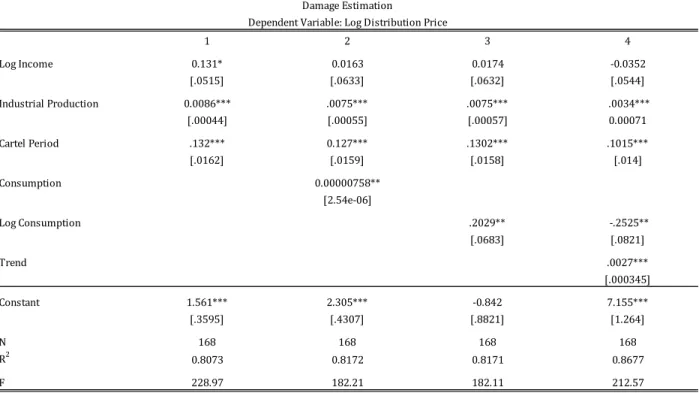

The aim of this paper is to review the methods available for cartel damage quantification and apply it on a practical case. We start this study by understanding the harm that collusive practices used by cartels cause to economy and society. We then explore the different types of empirical methodologies used in calculating the estimated damages and the trade-offs of employing them. Next, we compare how antitrust agencies operate in the United States, European Union and Brazil and discuss their roles in calculating the damages and setting an appropriate fine to an antitrust violating firm. Finally, we take make an in depth analysis of a cartel in the Liquefied Petroleum Gas distribution market from February 2003 to April 2005 in the state of Pará, Brazil, employing the multivariate before and after and the difference-in-difference approaches. We found that the price overcharge for the cartel was between 10% to 13% in the first methodology and 16% to 17% in the latter.

5

RESUMO

As práticas colusivas utilizadas pelos cartéis revelaram-se extremamente prejudiciais à eficiência econômica e ao bem-estar social. A detecção desse tipo de prática tornou-se uma prioridade das agências antitruste em todo o mundo. Os reguladores estão constantemente em busca de maneiras eficazes de punir as empresas, para que os custos do conluio superem seus benefícios. Essas punições geralmente vêm na forma de multas ou pagamentos de compensação que são calculados com base nos danos estimados causados pela empresa em conluio. Porém, a detecção de um cartel pode representar um desafio para economistas pois é um processo demorado que involve a estimação de um mercado contrafatual para ser comparado com o mercado onde se suspeita um comportamento colusivo.

O objetivo deste artigo é revisar os métodos disponíveis para a quantificação de danos de cartel e aplicá-lo a um caso prático. Começamos este trabalho estudando o dano causado pelas práticas colusórias à economia e à sociedade. Exploramos, então, os diferentes tipos de metodologias empíricas utilizadas para calcular os prejuízos estimados e as vantagens e desvantagens de cada. Em seguida, comparamos a atuação das agências antitruste nos Estados Unidos, na União Européia e no Brasil e, sobretudo, a forma em que calculam os danos e estabelecem uma multa apropriada para uma empresa que viola a legislação antitruste. Finalmente, realizamos uma estudo de caso de um cartel no mercado de distribuição de gás liquefeito de petróleo que ocorreu entre fevereiro 2003 a abril de 2005 no Pará, Brasil, empregando as várias metodologias estudadas acima e abordando as metodologias do before and after econométrico e o diferença em diferença. Verificamos que o sobrepreço estimado para o cartel se situava entre 10% e 13% na primeira metodologia e entre 16% e 17% nessa última.

6

List of Acronyms

ANP - Agência Nacional do Petróleo

CADE - Conselho Administrativo de Defesa da Concorrência DOJ - Department of Justice

FERGAS - Federação Nacional de Revendedores de Gas Liquefeito de Petróleo HHI - Herfindahl-Hirshman Index

IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IPEA - Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada LPG - Liquefied Petroleum Gas

7

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 8

Chapter 2 - Cartel Damage Evaluation: microeconomic analysis ... 10

2.1 Cartel formation in the final consumer market ... 10

2.2 Cartel formation in intermediary markets ... 12

Chapter 3 - Empirical Methods in Cartel Damage Evaluation ... 17

3.1 Trade-offs Between Empirical Methods: accuracy and practicability ... 17

3.2 Empirical Approaches for Calculating Damages ... 20

3.2.1 "Before and After" Time Series Methodology ... 20

3.2.2 Multivariate "Before and After" Approach ... 23

3.2.3 Yardstick and the Difference-in-Differences Methodology ... 24

3.2.4 Cost-plus Approach ... 27

3.2.5 Structural Models and Market Simulation... 28

3.3 Comparing Methodological Approaches ... 29

3.3.1 United States and European Union ... 32

3.3.2 Brazil ... 35

3.4 Administrative vs. Judicial: Defining their role in cartel punishment ... 37

Chapter 4 - A Case Study on Liquefied Petroleum Gas Cartel... 38

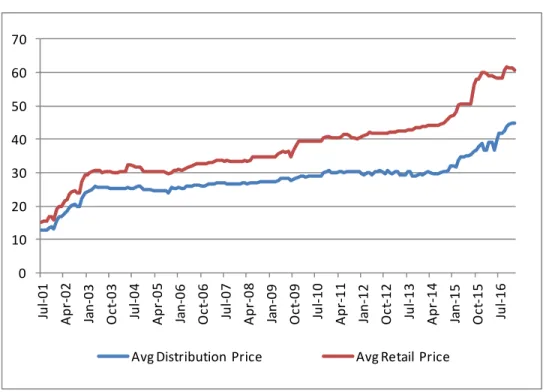

4.1 The LPG Market in Brazil: An Overview ... 38

4.2 The Case ... 41

4.3 Empirical Analysis ... 43

4.3.1 Multivariate "Before and After" Approach Applied ... 46

4.3.2 Difference-in-Difference Applied ... 48

Conclusion ... 56

Bibliography ... 59

APPENDIX A - Stata Outputs, Log files ... 62

8

Introduction

Collusive practices used by cartels have proven to be extremely harmful to economic efficiency and social welfare. The act of two or more competing firms to coordinate decisions allows them to earn higher profits than they would have in a competitive environment. By forming a cartel, firms aim at maximizing their joint profits. In such cases, the colluding firms may exercise market power by increasing price above marginal costs and consequently decreasing supply below the competitive equilibrium1. Not only does this decreases total welfare generated by the market, but it also allows cartel firms to appropriate most of the consumer surplus.

Detecting these kind of practices has become a priority within antitrust agencies around the world. Most countries have created laws that prohibit firms from coordinating with their competitors in order to decrease competition. However, detecting collusion is not so straightforward as one might think. According to Harrington (2004), there are two general ways of detecting a cartel: observing the means by which firms coordinate and observing its end result2. It is a very data-intensive and time consuming process since it involves estimating a competitive benchmark and comparing it to the behavior of the suspected infringers.

In addition, since colluding is highly lucrative when successful, it is attractive for firms to engage in the practice when they see an opportunity. In a study performed by Ivaldi et al. (2016), on average, competition authorities do not recuperate excess profits gained by cartel members, even in developed countries.3 Therefore, regulators try to find effective ways to punish companies so that the costs of colluding outweighs its benefits. These punishments usually come in the form of fines or compensation payments that are calculated based on the estimated damages caused by the colluding firm. However, imposing a penalty that is too high can have a contrary effect, undermining the firm's ability to be an efficient market player, hindering the

1 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380.

2 Harrington, Joseph E. "Detecting Cartels," Conference: Advances in the Economics of Competition Law, 2004. 3 Ivaldi, M. et al, "Cartel Damages to the Economy: An Assessment for Developing Countries," Competition Law Enforcement in the BRICS and in Developing Countries. Switzerland: Springer, 2016. pp. 103-133

9 main objective of bringing the economy back to fair competition.4 Therefore, antitrust agencies must balance these two objectives.

A lot of controversy has surfaced concerning the role of the antitrust agency in calculating the estimated damages. Some experts argue that the sole role for an antitrust agency is to implement a fine to punish the infringers. Others argue that in order to set an appropriate fine, regulators must be able to calculate the estimated damage cause by the collusion.

Calculating damages caused by a cartel is an important step in the direction of establishing an appropriate level of compensation to award the plaintiff or estimating the illegal profits obtained by the cartelized industry so to impose a fine. The nature of damages calculation will depend on the legal framework in place; each country have different provisions as regarding to who can bring a claim and to what kind of damages may be vindicated5. It will also depend on the type of data that is available and the time and human resource constraints in each case. When selecting a suitable approach to calculate estimated damages, analysts will have to aim for a method that can lead to accurate results without hindering practicality and at the same time taking into consideration the legal constraints, such as information asymmetry and burden of proof.

The objective of this paper is to review the methods available for cartel damage quantification. The text is organized in the following way: In Chapter 1 we carry out a microeconomic analysis of the effects of cartels on the economy and social welfare. Chapter 2 discusses the trade-offs of employing the different evaluation methods and takes a detailed look into the most commonly employed empirical methods in cartel cases worldwide - namely: (i) Before and After Time Series Methodology; (ii) Multivariate Before and After Approach; (iii) Yardstick Approach and the Difference-in-Difference Method; (iv) Cost-plus Approach; and (v) Structural models and Market Simulation. Following in Chapter 3, this paper will compare the strengths and weaknesses of each empirical method and how they are employed in different legislations: United States, European Union and Brazil. Finally, Chapter 4 will analyze a cartel case tried by the Brazilian antitrust agency, Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica - "CADE", in the Liquefied Petroleum Gas ("LPG") distribution market in the state of Pará, Brazil.

4 Ivaldi, M. et al, "Cartel Damages to the Economy: An Assessment for Developing Countries," Competition Law Enforcement in the BRICS and in Developing Countries. Switzerland: Springer, 2016. pp. 103-133

5 Clark, E. et al, "Study on the Conditions of Claims for Damages in Case of Infringement of EC Competition Rules: Analysis of Economic Models for the Calculation of Damages." Ashurt, 2004.

10

Chapter 2 - Cartel Damage Evaluation: microeconomic analysis

2.1 Cartel formation in the final consumer market

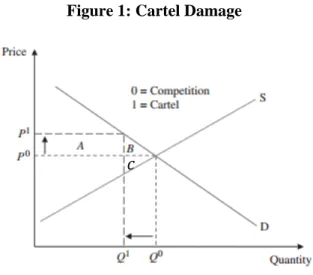

We first consider a situation where the cartelized good is sold directly to the final consumer. Cartel damages can be calculated by estimating the difference between the price actually practiced during the cartel and the price that would have been charged if the cartel hadn't existed - the so-called "counterfactual". On Figure 1 we have price represented by the vertical y-axis and quantity by the horizontal x-axis. The negative relationship between price and quantities is represented by the downward-sloping demand curve. This demand curve shows that buyers will purchase greater quantities at lower prices. The graph shows the observed prices and quantities implemented by the cartel, p1 and Q1, and the estimated counterfactual prices and quantities, p0 and Q0 that would have been observed had there not been a cartel.

Figure 1: Cartel Damage

The areas of rectangles A and B represent the total estimated damage incurred by consumers. Rectangle A represents the transfer of consumer surplus to the producer additional profits and B the deadweight loss from goods that would have been sold at p0 but are no longer sold at p1. Equation 1 illustrates a rent transfer from the consumer to the producer:

Source: Davis and Garcés (2010)

11

( 1 )

The term (p1 - p0) in equation 1 is denoted as the "price overcharge;" consumers will pay p1 instead of p0 and purchase quantity Q1 instead of Q0. In other words, consumers are charged a higher price than they would have been under competition and have a lower quantity available in the market6. By adding the two areas, you get the total damage to consumer from the cartel.

Triangle C, on the other hand, represents the deadweight loss to the producer, or what it could have sold at p0 but didn't at p1.

Deadweight loss is inefficient because it restricts the output available in the economy and pushes out of the market potential consumers, who would be willing to purchase the good at the price interval [p0, p1]. The producer also suffers with the deadweight loss, however, since the transfer in consumer surplus to the producer (area A) is always larger than the deadweight loss to the supplier (area C), the cartel is still worthwhile for them. While the deadweight loss is considered a problem by antitrust authorities, it is rarely included in the damage calculations due to the difficulty of accurately measuring it. In order to calculate the total amount of deadweight loss, one has to estimate five elements caused by the infringement: (i) the market output with the violation; (ii) the amount of the overcharge; (iii) what the market output would have been in a violation-free world; (iv) the price that would have been charged had there not been the violation; (v) the shape of the demand curve between (i) and (iii)7. In particular, items (iv) and (v) pose a seriously challenge, since they require the analyst to estimate the elasticity of demand. Some scholars argue that trebling actual damages may serve as a surrogate measure to actually calculating the deadweight loss8. Others argue that if antitrust violators are not held accountable for the deadweight loss their actions inflict on consumers and the market, the damages owed

6 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380

7 Leslie, C.R., "Antitrust damages and deadweight loss," The Antitrust Bulletin, 51(3), pp. 521-567, 2006.

8 The employment of trebling in place of actually calculating the damages caused by the deadweight loss is still a very controversial issue among scholars. While some argue that trebling damages can mitigate the effect of DWL, others argue that it does not, since it still excludes consumers that were forced out of the market. In addition, they argue that since many collusion cases are settled, trebling doesn't even take place so it does not provide full compensation for the higher prices consumers who continued to buy the product had to pay (Leslie 2006)

12 would be an insufficient deterrent9. For the purposes of this study, we will exclude the deadweight loss from the damages calculation.

2.2 Cartel formation in intermediary markets

Now, we extend the previous analysis to the context of a production chain, where the cartel is established in an intermediary market. If we consider the cartelized product as an intermediate production good, used as an input factor by a downstream firm in the production of a final good, the direct cartel effect will be reflected by an increase of the direct purchasers’ variable costs10. Assume that a firm in a competitive market sells its good to a downstream firm at a wholesale price wcomp. The retailer (the downstream firm) sells its good to its end consumer at a retail price rcomp. Assuming for simplicity that the retailer has no cost other than its input cost wcomp the firm's profit would be rcomp - wcomp.

Now, if the upstream firm decides to enter into collusive agreement setting its prices at a higher level than the competitive price as an attempt to raise its profits, that will affect its direct purchasers profit. In this case, the cost for the downstream firm will rise to wcartel and it will have to increase its retail price in order to minimize its loss.

9 Leslie, C.R., "Antitrust damages and deadweight loss," The Antitrust Bulletin, 51(3), pp. 521-567, 2006.

10 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee (2011)

13

Figure 2: Damages with two layers of downstream purchasers

This market dynamics is illustrated in Figure 2. The shaded area A represents the overcharge earned by the cartel practiced by the upstream firms. Rectangle B shows the fraction of the overcharged that is passed-on from the downstream firm to the final customer. The increase in costs of its input will make the retailer increase its price by a fraction of the overcharge so as to minimize the loss resulting from the collusive prices. It is important to highlight that the shaded area B, or the pass-on, will almost always be smaller than that of A, since retailers can only transfer a portion of the price increase to the final consumer11. The amount that will be passed on, will depend on the demand elasticity of the good; the more inelastic the product's demand curve is, the larger the pass-on will be. Rectangle C represents the output effect, or the additional profit that the retailer would have made if he could have bought the inputs from the upstream firm at the competitive wholesale price (wcomp). Lastly, the shaded area D represents the output effect for the end-consumer. It represents the additional utility that the final consumer would have gained at a higher consumption level, had there not been a collusive agreement at the upstream level. Not only does the price of the final good increase but the quantity of goods

11 Unless the demand is perfectly inelastic, the pass-on will always be smaller than the price overcharge implemented by the cartel.

14 supplied will decrease, having a serious effect on consumer's utility and total welfare12. The total harm to the final consumer is represented by the shaded areas B+D.

Although the bulk of the social costs of cartels resides in the aggregate overcharge, the potential effects of a cartel can be even larger than that. The market power gained by firms engaging in cartel activity can lead to indirect effects (also known as umbrella effects13), where non-conspiring firms are enabled to charge higher prices. Not only does it affect direct and final consumers, it may also affect the cartel's upstream supplier. A cartel may enforce lower input prices from its upstream supplier, either by reducing its overall demand or simply by negotiating price as a single entity. The upstream suppliers can pass on these worsened sale conditions to its upstream supplier and so on. It also may have an exclusionary effect on a potential competitor outside the cartel and their potential consumers.

12 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee (2011)

13 The umbrella effect is a strongly debated issue regarding the estimation of damages. The question of whether the cartel participant should be liable to pay damages to a direct buyer of an output from a non-participating seller under the argument that this seller increased price under the protection of a "price umbrella" created by the cartel raises many unanswered questions. (Clark 2004)

15

Figure 1: Downstream and upstream cartel direct and indirect effects14

Source: European Commission: OECD Competition Committee (2011)

We summarize the potential effects of a cartel into three main parts, as illustrated by Verboven and Van Dijk (2009)15. First, there is the price overcharge or price effect. The price overcharge can be translated into the decline in downstream profits due to higher costs from buying input at a higher price from the cartel. If the cartelized product is an intermediate good considered as an input factor to an end product, it will also have an effect on the final consumer. Which leads us to the second effect, the pass-on effect. This happens when downstream firms increase their price in order to pass-on to the final consumer some of their cost due to the increase in the cartel price. This decreases the damage caused to the downstream firm but leads to an indirect effect on the final consumer. It is important to highlight that in many jurisdictions, namely the US, the pass-on defense is not allowed in courts. In such cases, cartel members are held accountable for the entire

14 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011

15 Verboven, F. and Dijk, van T., "Cartel Damages Claims and the Passing on Defense." SSRN Eletronic Journal, 2009.

16 damage caused by the overprice, even if it was not entirely incurred by the downstream firm. Finally, there is the output effect: a price increase in a product from a cartelized industry will usually have a negative effect on the quantity produced. Therefore, the output effect considers the lost margins on units no longer sold due to the decrease in supply under a cartel.

As we have seen before, in most cases, the customer of the cartel may be a downstream firm that may transfer some or all of the increase in the price of their inputs to the final customer. This is called the pass-on effect. In a potential damage claim, the defendant might use this as a defense to decrease the magnitude of the damages owed to the plaintiffs. To measure the pass-on effect investigators have to be able to measure the price increase of the good that was sold from the downstream firm to the final consumer. From the point of view of the downstream firm, the price increase of the input bought from the cartel is equivalent to an increase in their marginal cost. Often, the downstream firm is only able to pass on a portion of the price increase (shaded area B in Figure 2). However, the more market power the downstream firm possesses the larger the pass-on will be16. As a general rule, the pass-on defense is not allowed in US antitrust cases. In Europe, however, it is more common to see the pass-on defense being used in courts.

Still, determining which concepts should be incorporated in the process of calculating the damages is essential. The first and foremost step requires that the antitrust authority defines the concept of "damages". The anticompetitive price overcharge has frequently been key for computing damages claims, but simply using overcharge to quantify damage might seriously underestimate the true damage caused by a cartel. Looking solely at the overcharge to the direct customer of the cartel does not take into consideration the deadweight loss and ignores the loss of total welfare. The calculation could also become more complex if one considers the potential dynamic effects. These effects might increase damages if a competitive environment could have contributed positively to technological advances. On the other hand, it could mitigate damages if the higher profits earned by the cartelized firms contributed to higher investments in R&D17.

16 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380.

17 A studied performed by Andrea Günster, Mathijs van Dijk and Martin Carree concluded that in general cartels hinder innovation by decreasing investments in R&D because there is lower incentives to invest in new products and technologies. However, in some rare cases, higher profits could contribute to R&D investments.

17 Since these effects are far too complex to be measured, they are usually ignored when calculating damages. One might also discuss if the pass-on effect could be used by defendant in attenuating the potential damage. Answering these questions is imperative in order to define the theoretical framework in which the damage calculation will take place. In this study, we will not incorporate the pass-on in the damages calculation.

Chapter 3 - Empirical Methods in Cartel Damage Evaluation

3.1 Trade-offs Between Empirical Methods: accuracy and practicability

When deciding on which approach will best be suited to estimate the damages, analyst face trade-offs that have to be taken into consideration during the empirical economic analysis. While some trade-offs are related to the economic methodology itself, others concern the legal constraints, such as the burden of proof, that will define the economic approach.

Cartel damage estimation requires the analyst to reconstruct a situation that would have occurred if there had been no infringement – the counterfactual - and calculate the price that would have prevailed had the markets been acting competitively. In order to calculate these counterfactual prices, analysts have to choose from a variety of available techniques.

The first and main concern when calculating the counterfactual in cartel cases is to be as accurate and close to the truth as possible. In order to get there, experts have to balance the trade-off between accuracy and practicality18. Quantifying the effects of a collusive conduct requires the creation of a counterfactual scenario, where you try to estimate what the prices would have been if there had been no cartel. The closer to the real world a model gets the more complex it becomes. In statistical terms, accuracy can be defined as being correct on average and precise. Being correct on average is not the same as being close to the truth; you could be greatly over or underestimating the true value of the damages in one case and still be statistically correct on

18 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

18 average. This is why one also has to consider the precision of the calculation, or how close to the truth is the estimate. Note that it is better to have a biased and precise estimate than to have an unbiased but imprecise one. The more economic assumptions that is employed in the calculation the more precise the estimation will be. However, if the assumptions are incorrect, you will obtain biased results.

This leads us to the concept of practicality19. The damage calculation process should be conducted within a reasonable timeframe and with the available resources. Antitrust authorities experience time constraints and have a limited amount of manpower that can be allocated to a specific project. Therefore, it is very important that the company makes the necessary information readily available to the authorities or economic analyst. Another key factor that helps ensure practicality is proper data submission and presentation style. Economists must provide the raw data and any adjustments made to the data and the statistical method used to derive your results so that a second expert can easily verify the results. This also facilitates the comprehension of the methodology and results by judges and lawyers. The expert must be prepared to explain the logic behind the chosen method, so the more practical the approach the easier it is to explain. The choice between accuracy and practicality will vary on a case-by-case basis and will be highly influenced on the data available. Sometimes, it will not be possible to obtain an accurate empirical estimate within a reasonable timeframe or with the available resources. In such cases, it is up to the legal system to determine how to proceed.

Finding a reasonable balance between accuracy and practicality affects how each expert tailors his economic analysis. It includes the decision of which data to use and which ones to leave out, the number of variables and which method to employ. Working with data submitted by parties involved in the investigation will most likely lead to more accurate estimations. However, working with public data not only shortens the data collection period, but also makes you less susceptible to data manipulation and allows for cross-firm comparisons20.

The number of variables to include in your analysis is also key to achieving unbiased and accurate results. Although it is important to control for factors that affect price, including all

19 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

20 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

19 demand and cost shifters, not only leads to an intensive data collection process but also may reduce the accuracy of the estimates. If the variables are highly correlated and the individual impact of each variable is not of interest in the analysis, it would be enough to include only the representative variables and control for the combined effect. On the other hand, omitting an important variable will lead to biased estimates.

Finally, in many jurisdictions, empirical economic evidence is not sufficient to prove a misconduct in cartel cases. Investigators are required to present evidence of explicit communication between infringing firms in order to meet the legal standard of proof21. In Brazil, although rare, it is possible to prosecute and condemn a cartel even when there are no concrete evidence of exchanges between colluding firms. In some few cases it has been enough to be able to demonstrate economic indicators of a collusion, however in these cases the burden of proof were much higher22. The burden of proof for proving a collusive conduct is also higher when quantifying damages but that also varies among jurisdictions. Once the antitrust authority has been able to achieve the required standard of proof, the burden of proof shifts to the defendant, who will then have to prove that the authority's assertions are wrong. When legal standards are higher, experts might be required to present more accurate results, which may lead them to rely on more than one empirical approach. This brings us back to the trade-off of practicality and accuracy.

Information asymmetry is an important element to consider when discussing the burden of proof. In cartel cases, the plaintiff does not hold all the information necessary to prove the damage; usually the defendant is the one who holds the information required to calculate the overcharge and quantify the damages of the infringement. On the other hand, the plaintiff holds the data on the pass-on that could potentially mitigate the damages owed by the defendant23. This creates a trade-off on information disclosure among the parties. Tight disclosure rules assures that both parties have access to the information they need to make their case but it also results in excessive transparency. There have been cases where excessive transparency led to tacit collusion and

21 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

22 CADE: Administrative Process no. 08012.001273/2010-24

23 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

20 higher prices post-intervention, which although not illegal also leads to anticompetitive effects. Therefore, it lies within the courts and judges to offer guidance in such matters and it will vary case-by-case.

3.2 Empirical Approaches for Calculating Damages

To understand the robustness of any economic model one has to take into account three important issues: i) the data used; ii) the assumptions made by the investigator; and iii) inferences that can be drawn from the outputs. A model is only as good as the data input used to populate it and the theory used to provide the assumptions24.

3.2.1 "Before and After" Time Series Methodology

A possible simplistic approach in quantifying price overcharge is to compute the difference between the cartel price and the perfect competitive price. Under perfect competition, assuming no fixed costs, price will be equal to marginal cost. For illustration purposes, we assume a linear inverse demand function, pt = at - bQt. In order to maximize profits, the cartel acts as a

monopolist and chooses joint production quantity such that marginal revenue equals marginal cost25.

2

( 1 )

By substituting the cartel output choice into the demand function and assuming a > c:

2 ( 2 )

24 Komninos, A., et al, "Quantifying Antitrust Damages Towards Non-Binding Guidance Courts." Oxera. 2009. 25 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380.

21 In a perfect competition world, pt = ct26, therefore the overprice per unit will be the difference

between the average price in the cartel period and the average price in free competition:

Overprice per unit = pCartel - pComp ( 3 ) Multiply equation ( 3 ) by the total quantity sold in the cartel period to get the total overcharge. The Before and After method is a time series based approach that can be understood as the empirical counterpart of the analytical discussion above. It basically compares average prices between specific periods. First, the analyst will collect the historical prices practiced by the companies participating in the cartel, both before and after the cartel began and then compare it to the prices practiced during the time the cartel was in place.

The straight-line method assumes that prices in a competitive environment would have grown or decreased at a constant rate. Then, the expert will draw a line from the point before the anti-competitive practice started to the period after the practice ended27. The difference between the actual cartel price and the counterfactual price will allow for the calculation of the damage:

Damages = (pCartel - pComp)*Qcartel

26 Note that the marginal cost in competitive equilibrium is not a given but can be calculated based on the information on cost.

27 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380.

22 Figure 2: Straight-line approach

Source: OECD

In countries where before prices are not available, a more simplistic approach can be applied. Assuming that prices are constant you can set price during infringement period equal to price after the conduct.

The Before and After method assumes that the benchmark period represents a reasonable price estimate for the counterfactual. It also provides a good estimate when the cartel is stable and the basic conditions of supply and demand do not change too much. However, the longer a cartel has been active, the less reliable this method becomes. In this case, historical prices are not the best indicative of what prices would have been under a competitive market28. Furthermore, this method disregards price change due to external factors, such as change in demand structure, costs, or in the competitive environment. In order to address such shortcomings, more sophisticated econometric models that allow to control for these factors are required29.

Another relevant issue when dealing with the Before and After model is the difficulty of determining the exact date of the beginning and end of the cartel. Many scholars claim to be able

28 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

29 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

23 to deliver a rough estimate of the period a cartel was active, but when the cartel is defined with multiple price wars and constant breakdowns and regrouping, it is impossible to determine a specific date of its establishment30. Transforming this approach into a simple regression framework using dummy variables can mitigate this problem.

3.2.2 Multivariate "Before and After" Approach

The Multivariate Approach is an advanced extension of the Before and After method. It has the advantage of not being limited to perfectly competitive markets for the price benchmark. In fact, it assumes an oligopolistic behavior of the relevant market. In this approach, the economist will run a reduced form regression of the price level on demand and cost factors that affect price but are not controlled by the cartel31. This allows the specialist to control for various exogenous influences on price, which posed a problem in the previous model. It is important to note that econometric analysis does not prove causality but it seeks to establish statistically significant relationship between the dependent variable and the other explanatory variables.

Using the dummy variable model, price is set as a dependent variable. The investigator then includes a dummy variable that will represent the period of cartel activity; Dt = 1 means Active

and Dt = 0 means otherwise. The coefficient of the dummy variable will capture the magnitude

of the unexplained increase in prices during the cartel, giving us the overcharge per period. In this model, it is important to use only relevant variables so that you do not reduce the size and significance of the coefficient, giving a result that translates into little or no damages due. One must keep in mind that the dummy variable coefficient will only capture the average price increase during the entire duration of the cartel, independent of changes in market conditions. Also, the dummy variable is not so efficient in capturing the exact period in which the cartel

30 Grossman, Peter, "Why One Cartel Fails and Another Endures: The Joint Executive Committee and the Railroad Express," How Cartels Endure and How They Fail: Studies of Industrial Collusion, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004. p. 111-129

31 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380.

24 ended. Cartels may wind down gradually and not immediately, with prices decreasing slowly as the cartel reaches its end32.

On the downside, this model requires an extensive data base and a large amount of market influence factors have to be taken into account. The analyst must be attentive to correlation among variables and must have an extensive knowledge of the relevant market and institutions.

( 4 )

= vector of demand and cost factors that affect price = dummy variable representing active cartel period

If the model results in a positive β, there is sufficient evidence for the existence of a cartel. Overall, the before and after models are practical and lead to sufficiently accurate results without requiring too much data or human resources. However, differently from the structural model that we are going to see further ahead, it ignores the deadweight loss from the calculation so that damages would be equal to the estimated overcharge.

3.2.3 Yardstick and the Difference-in-Differences Methodology

When dealing with a cartel that has not been stable throughout its existence or when supply and demand conditions fluctuated in a significant way along the years, a better way to estimate the counterfactual price is to use the Yardsticks approach. This method quantifies damages by comparing the collusive prices with the ones that were practiced in other competitive, but comparable, markets. It can be considered an extension to the Before and After model with the addition of cross-sectional comparison. First, you get the price of a related product that did not take part in the cartel and use it as a benchmark. This method is challenging because the two products must be similar in terms of demand, costs and market structure and should at least be from the same country so that institutional shocks are similar.

32 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380

25 The downside of this method is that you have to control for the variances inherent to different products or geographical market. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that the benchmark chosen is cartel-free or unbiased. If the cartel has effects on related market (umbrella effect) estimators of price effect may be biased.

Transforming the yardstick approach into a multivariate regression allows us to control for some of the factors that may influence price. The basic assumption in this model is that all differences in price that cannot be explained by exogenous factors are a result of an anticompetitive behavior and can thus be translated into overcharge.

You can also unify the Before and After approach with the Yardstick approach into a single framework known as the difference-in-difference. The difference-in-difference approach is an econometric method that uses panel data to run cross-sectional data from different periods and markets, which increase the validity of the results. If you have relevant data on various regions (some that are affected by the cartel and some that are not), the difference-in-difference method will allow you to compare the differences in both markets.

The purpose of implementing this approach is to evaluate the impact of a treatment on an outcome Y across different groups. In this case, we will be dealing with two groups: one that has received treatment, or a shock, denominated T=1, and another that does not receive the treatment, T=0, which will be our control group. The analysis will be performed in two periods where t=0 indicates the pre-treatment period, and t=1, indicates the post-treatment period33. Each individual or group will have two notations, one pre-treatment and one post-treatment. To simplify, let us have Ȳ0T and Ȳ1T as the sample averages of the outcome for the treatment group

before and after treatment, respectively, and Ȳ0C and Ȳ1C the sample averages for the control

group.

The outcome Yi can be modeled as:

∗ ( 5 )

The coefficients α, β, γ, δ are unknown parameters representing:

26 α = constant term

β = treatment group specific effect

γ = time trend common to control and treatment groups δ = true effect of treatment

The purpose of the model is to arrive at an appropriate estimate for δ, that is , given the data available.

The difference-in-difference estimator is defined as the difference in average outcome in the treatment group before and after treatment minus the difference in average outcome in the control group before and after treatment.

( 6 )

Given the unbiased estimator assumption, if we take the expectation of the estimator we get:

( 7 )

( 8 )

The estimator in Equation 7 is basically taking the average difference in outcome Yi for the pre

and post-treatment period in the treatment group and subtracting the average difference for the pre and post-treatment period for the control group.

Another way to look at the difference-in-difference estimator is as follows:

Pre Post Post-Pre Difference

Treatment Control T-C Difference

27 However, like with any other model, the difference-in-difference approach also has its downsides. Two assumptions must hold in order to guarantee an unbiased difference-in-difference estimators: i) there must be a common trend between prices from the control group and the treatment group in the periods before the shock, i.e. treatment and control groups should be expected to follow similar factor processes prior to the treatment period; and ii) treatment and control groups should not, on average, experience differential shocks in the post-treatment period. If any of these assumptions do not hold, then there is no guarantee that the DD estimator is unbiased. A second caveat is related to the control group formation. Finding a relevant and accurate benchmark, that has similar characteristics to the market in question without having been affected by a cartel is not an easy task. As we will see ahead, this discussion was brought by one of CADE's advisors in his vote concerning that LPG cartel in the state of Pará.

3.2.4 Cost-plus Approach

The Cost-based Approach uses financial information of an industry or company to calculate the counterfactual price using a bottom-up analysis. The analyst will take the relevant production costs and add a reasonable profit margin that could have emerged in an otherwise competitive market. Typically, the average costs will be calculated based on accounting data or information available from management reports.

However, it is a somewhat challenging method to employ. First, calculating an appropriate profit margin to add to the average unit cost of production can be quite difficult in practice. Also, since in most cases the accounting costs do not reflect actual economic costs it becomes extremely difficult for investigators to calculate a robust cost estimates. In addition, some may consider this method an oversimplification of the factors that affect price in a cartel-free world - it assumes that competitive costs and price-cost margin are constant when the cartel is in place34. It is also a method with high data requirement and is time consuming. However, it could be a good proxy for a counterfactual when dealing with companies in markets where there is a constant relationship between price and cost.

34 Clark, E. et al, "Study on the Conditions of Claims for Damages in Case of Infringement of EC Competition Rules: Analysis of Economic Models for the Calculation of Damages." Ashurt, 2004.

28 3.2.5 Structural Models and Market Simulation

Contrary to the yardstick, a comparator-based model, the structural model relies on a simulated-base benchmark to calculate damage. The Simulation method, also known as the "Oligopoly Model Method," as described by Clark et al (2004), aims at calculating the relevant market data on costs, price, quantities, and profits in a collusion-free world. It uses economic models based on industrial organization theory to predict the effect of the shock on prices and output35. It is worth highlighting that this approach is the only one discussed in this paper that has the capacity of measuring the deadweight loss.

The economic analyst will build an economic equilibrium model to determine prices, quantities, costs and marginal costs in a cartelized industry. Once assumptions are specified and the model is laid out, the prices that would have been under competition can be calculated and compared to those practiced during the cartel. This model also assumes an oligopolistic behavior, so it is important to decide whether you are dealing with a Bertrand or Cournot competition. This method requires information on costs, market structure and demand and a profound understanding of the market.

Even though it has an unique capacity of capturing a parcel of the damage that cannot be measured by the other models, it is a much more complicated and time consuming method. It is highly sensitive to the assumptions made about cost and demand parameters and how they affect prices. Also, since it is a data-intensive method it is sensitive to changes in its settings and parameter values. Damage quantification based on simulation methods might be closest to real-world competitive market outcomes, since they do not rely on cost data provided by defendant and are very transparent for outsiders. However, not only does it present the largest challenges for economists with regard to the high level of market knowledge that is required,36 it also faces difficulties in being validated in court as an appropriate damage calculation method. Since it is a more complex method that involves strong assumptions on a "would be" demand, it tend to be more vulnerable towards courts. Judges and other non-experts may face some difficulty in interpreting the results and the model specifications, therefore economists have to be very

35 Clark, E. et al, "Study on the Conditions of Claims for Damages in Case of Infringement of EC Competition Rules: Analysis of Economic Models for the Calculation of Damages." Ashurt, 2004.

36 Davis, Peter and Eliana Garcés, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 347-380.

29 educated with this kind of model-building and have to prepare good documentation for its replication.37

3.3 Comparing Methodological Approaches

In order to ensure the robustness of the estimates, practitioners generally apply various methodologies to assess cartel damage. In general, different methods applied to identical cartel episodes did not result in significantly different estimates.

The most common method used among the studies was the Before and After where the price during the cartel period is compared to a counterfactual price. The second most commonly employed method, accounting for 20 percent of the estimates, was the statistical modeling, including the multivariate before and after. The Yardstick approach accounted for 10 percent of the samples while the Cost Based method accounted for 3 percent.

Connor and Lande (2008)38 concluded that the Before and After time series method usually provided overcharges estimates that were higher than other econometric models applied to the same cartel episode. One possible reason for such result is that analysts using the Before and After Method may have failed to adjust for all competitive factors that influence the competitive benchmark price. The Cost-based and Yardstick approaches yielded even higher overcharge estimates. One explanation for these higher estimates is that using cost or profits fail to fully account for all competitive industry cost. In the Yardstick approach cases, analysts may have underestimated quality differences between the products.

On Lucinda and Seixas (2016)39 three different methods were tested to calculate overcharges estimates for a peroxide cartel in Brazil. Investigators arrived at similar results when applying the three distinct methodologies, however, just like in Connor's study, some led to higher

37 Doose, Ana Maria. "Methods for Calculating Cartel Damages: A Survey." Ilmeneau Economics Discussion Papers, Vol 18, No. 83, 2013.

38 Connor, J., and Lande, R., "Cartel Overcharges and Optimal Cartel Fines." Issues in Competition Law and Policy 2203, Chapter 88, 2008.

39 Lucinda, C. and Seixas, R., "Prevenção Ótima de Cartéis: O Caso dos Peróxidos no Brasil." Departamento de Estudos Econômicos do CADE, 2016.

30 overcharges estimate than others. The time series model resulted in a decrease in price of something in between 15.5 to 22 percent after the end of the cartel40. The average corresponding damage caused by the cartel was R$109.93/ton.

The second method tested was the Difference-in-Difference. In this case the investigators collected evidence on a market that could be used as a counterfactual both in South America and the United States. The price reductions for a counterfactual market in the United State was R$ 54.8/ton while the scenario with a South American counterfactual was R$ 75.2/ton. When using both markets as counterfactuals the price reduction was R$ 67.5/ton.

At last, investigators applied the structural models to estimate the overcharges for the peroxide cartel. To do so, they had to construct an equation system that reflected the supply and demand relation.

( 5 )

where,

= quantity of Hydrogen Peroxide sold = price per ton of Hydrogen Peroxide

= demand driver (production in the cardboard sector)

( 6 )

where Wt is the cost of labor and Pt = f(Qt,Wt).

The structural model resulted in an estimated damage of R$ 68.67/ton.

These results allows us to conclude that the time series model resulted in a somewhat higher overcharge than the other models.

For practicality purposes, many countries recur to more straightforward methods when determining cartel damage in cases of relatively minor economic importance. A simple method relies on results from previous cartel cases. This method takes into account the average

40 The values differ depending on the month established for the end of the carte. Three possible cartel end dates were tested.

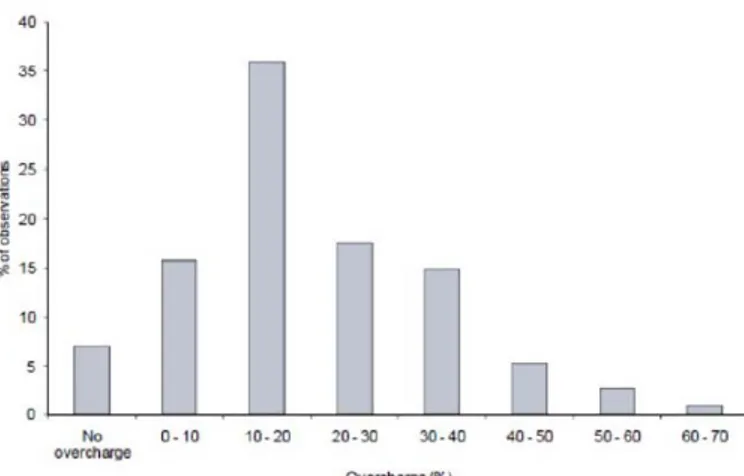

31 overcharge observed in past known cartels and apply it to any current case. There is an increasing number of data on overcharge estimation available in cartel cases which allows us to estimate the average overcharges. We can see from Figure 4 that the majority of detected cartels have an estimated overcharge between 10% to 20%.41 The empirical evidence of existing overcharge estimations suggests a high variation of overcharges across various cases, highlighting the need for case specific estimates. Given the high variation and the lack of precision of this method in determining the actual overcharge in any given case, not all jurisdictions admit it as an adequate measure of effective damage.

Figure 3: Historical overcharge estimations

The United States Sentencing Guidelines established an overcharge estimate of 10 percent of the total volume of commerce. They then doubled that amount to apply the base fine for infringing firms42. Recent studies, however, have concluded that an overcharge estimate of 10 percent is excessively low43. Surprisingly, 79 percent of the overcharges were above 10 percent and 60 percent were above 20 percent. The median cartel overcharge for all types of cartels in the period

41 Connor, J. and Lande, R., "Cartel Overcharges and Optimal Cartel Fines." Issues in Competition Law and Policy 2203, Chapter 88, 2008.

42 United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual, (Nov. 2015)

43 Connor, J., and Lande, R., "Cartel Overcharges and Optimal Cartel Fines." Issues in Competition Law and Policy 2203, Chapter 88, 2008.

32 studied was 25 percent44. This shows that the fines being currently applied on cartels are not nearly enough to hinder the practice.

In the following sections, we review the approaches that different antitrust agencies apply to cartel detection, damage evaluation and punishment.

3.3.1 United States and European Union

In the United States the Department of Justice ("DOJ") is not required to quantify the actual damages that were caused by the conspiracy in order to prove an antitrust infringement; showing actual or threatened harm to the competitive process is sufficient. Damage quantification is only required in lawsuits where plaintiffs sue for damage recovery. Since damage claims are almost always private, it does not lie within the scope of the antitrust authority to quantify that harm45. As a matter of fact, civil plaintiffs often build their case upon the DOJ’s investigations and sue companies and individuals that have already been prosecuted criminally. This allows them to use criminal fines as a benchmark for damages calculation.46

In order to avoid the complex and time consuming process of estimating the illegal gains obtained from the conspiracy, the US Sentencing Guidelines ("USSG") set the base fine for criminal antitrust violation at 20 percent of the volume of affected commerce as a proxy for pecuniary losses. According to the USSG, "[for] the purpose of this guideline, the volume attributable to an individual participant in a conspiracy is the volume of commerce47 done by him

44 This study contained 674 observations of average overcharges and included all types of cartels (price fixing, bid-rigging, etc). The investigators focused solely on injuries deriving from the transfer of income or wealth from purchasers to cartel. For the purposes of simplicity in the calculation, the study disregarded other potential harms such as umbrella effect, allocative inefficiency, less innovations, managerial slack, and non-price harms to quality and variety, among others (Connor and Lande).

45 European Commission: Policy Roundtables: "Quantification of Harm to Competition by National Courts and Competition Agencies." OECD Competition Committee, 2011.

46 Behre, Kirby et al., "International cartel investigations in the United States," The Investigations Review of the Americas 2017, Aug 2016. Accessed on April 2017 from http://globalinvestigationsreview.com/insight/the-investigations-review-of-the-americas-2017/1067471/international-cartel-investigations-in-the-united-states

47 The DOJ tends to assume that the volume of commerce affected should consider 100 percent of the sales of the good or services involved in the conspiracy. This approach is not always precise and may lead to unfairly high fines. Sometimes, only a fraction of the participant's sales has been affected by the collusive conduct. However, determining specific ways sales were affected by the violation is not only time consuming and complex, it still does not guarantee fair results.

33 or his principal in goods or services that were affected by the violation"48. The base fine level is derived from the estimate that the average gain from price fixing is 10 percent of the selling price. The USSG doubled that estimate to 20 percent in order to account for other harms inflicted on consumers such as the deadweight loss. This broad definition gives room for discussion on how to calculate the actual volume of commerce affected by the illegal conduct. After establishing the base fine, the court calculates a culpability score, based on the level of the offense and defendant's criminal history. This score is then used establish the minimum and maximum multipliers that will determine fine rage49.

When injury complained by a plaintiff is simply the overcharge, little in required under the US antitrust law. Litigants will have to estimate the counterfactual price using any defensible method they choose. The most commonly used method is the Multivariate "Before and After" Approach. The Difference-in-Difference approach is also frequently used, especially in cases where a product is simultaneously sold in different locations under both cartel and non-cartel prices. Obtaining the data to run these models does not pose a significant difficulty. Usually, the plaintiff has the data from their purchases, which makes it easier to calculate the overcharge. They can rely on public sources or obtain the necessary documents from the defendant. In addition, even if there are significant uncertainty about the extent of the damages it does not stand in the way of recovery. Although actual harm cannot be merely speculated, a reasonable inference with approximate results should suffice.

The passing on defense has not been an issue in court proceedings for at least half a decade. Since calculating the pass on complicates the litigation, it has been precluded by court. According to the Illinois Brick ruling, final or indirect purchasers could not recover overcharges passed on to them by the direct purchasers. It followed the Hanover Shoe decision, where courts made the cartel liable for the entire damages to the direct purchasers. However, this defense could be argued under state law50. In the current legislation, in theory, direct purchasers may claim the full price overcharge, whether there was pass-on or not, and the indirect purchasers may claim a part of that overcharge (that was passed on to them) duplicating a portion of the

48 United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual, §3E1.1 (Nov. 2015)

49 Doose, Ana Maria. "Methods for Calculating Cartel Damages: A Survey." Ilmeneau Economics Discussion Papers, Vol 18, No. 83, 2013.

50 Verboven, F. and Dijk, van T., "Cartel Damages Claims and the Passing on Defense." The Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol LVII, No 3, 2009. pp. 457-491.

34 damages due. In regard to the deadweight loss, no damage recovery can be claimed for input purchases not made. The Courts claimed that measuring the relevant elasticity are far too complex and they were not willing to make the drastic simplifications to the economic models in order to incorporate them51.

The European Union has a similar approach in setting fines for antitrust infringers. The EU Commission is also not required by law to estimate a precise or approximate quantum of consumer harm. Given the difficulty on quantifying harm to consumers and to competition, the Commission takes into consideration the gravity and the duration of the infringement and series of other proxies to set an approximate fine. The Commission analyzes the value of the sales generated by the company during the period of infringement with the product or service involved. Depending on the gravity of the violation they apply a fine of up to 30 percent of sales. Cartels are considered to be more grave violations and lie in the upper spectrum of the fine scale, between 15 to 30 percent52.

However, just like in the United States, consumers that were harmed by the infringement have the right to sue for damages recovery. The methods used by experts to reach an appropriate estimate for the damages incurred will vary on the applicable legal rule and the factual circumstances of the case. The most common methods used in the quantification of damages are the comparator based methods, which can be further refined by applying econometric techniques. These methods include the Before and After and Yardstick as well as the Differences-in-Differences.

Another common method is the Simulation model. Experts simulate a market outcome based on economic models of competition that replicate drivers of supply and demand conditions. However, the simulation model faces more scrutiny from courts and are often times disregarded as an appropriate method. This is due to the difficulty that non-experts face in understanding the model and its assumptions and also due to the strong assumptions that are made regarding the "would-be" demand curve in a competitive economic environment. A third common method is the Cost-plus approach.

51 Clark, E. et al, "Study on the Conditions of Claims for Damages in Case of Infringement of EC Competition Rules: Analysis of Economic Models for the Calculation of Damages." Ashurt, 2004.

52 Verboven, F. and Dijk, van T., "Cartel Damages Claims and the Passing on Defense." The Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol LVII, No 3, 2009. pp. 457-491.

35 It is important to observe that differently from the United States law, the European law allows infringers to use the pass-on defense in order to reduce the amount of damages due.

3.3.2 Brazil

Even though Brazil's competition regime has been developing into a more mature regulatory system, it is still lagging behind other major countries in terms of antitrust enforcement. Antitrust law enforcement was first created in 1994, following the opening of the Brazilian economy in the late 1980s53. It constituted of 3 agencies whose enforcement responsibilities constantly overlapped, leading to an inefficient and time consuming process. In 2011, the new Competition Law reconstructed the antitrust system, centralizing all preventive and repressive functions under one single agency, the Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Economica ("CADE"). Under the former Competition Act, antitrust violations were subject to fines of 1% to 30% of gross revenues registered by the violating firm in the year before the initiation of investigations54. However, this guideline was so broad that it led to series controversies and inconsistencies when calculating the fines. CADE sometimes considered the firm's entire revenue, whereas other times it just included the firm's revenues derived directly from the infringement. Therefore, the 2011 Competition Act narrowed down its guidelines in order to establish a closer link between fine and the amount of commerce affected. Under the new law, violations are subject to fines ranging from 0.01% to 20% of annual gross revenues registered by the company in the year before the initiation of investigations in the field of business of the infringement. This led to an open interpretation on how to define the "field of business". Some experts argue that fields of business encloses only the products and services affected by the company's anticompetitive conduct. However, a broader interpretation, usually the one antitrust authorities follow, argues that it can include other product or services that may be considered part of the same activity involved in the illegal conduct. This uncertainty on how to apply the fields of business to calculate fines leads to

53 Duarte, Leonardo Maniglia and Rodrigo Alves dos Santos, Overview of Competition Law in Brazil, "Cartel Settlements in Brazil: Recent Developments and Upcoming Challenges," São Paulo: IBRAC/Editora Singular, 2015, pp. 285-313

54 Martinez, Ana Paula and Mariana Tavares de Araujo, Overview of Competition Law in Brazil, "Anti-cartel Enforcement in Brazil: Status Quo & Trends," São Paulo:IBRAC/Editora Singular, 2015, pp. 257-274

36 risks of including unrelated businesses in the calculation and thus the application of disproportional fines.

Even though major developments in the regulatory system is still required, since 2003, hard core cartels has been gaining growing attention from antitrust authorities. Authorities implemented the leniency program and built a strong network with criminal prosecutors in order to gain access to more sophisticated investigative techniques55. To determine a fair and proportional fine the CADE takes into account a series of factors: i) level of seriousness of the infringement; ii) good faith of the defendant and its wiliness to help with the investigations; iii) gains or potential gains obtained from the violation; iv) whether or not the conduct has actually been consummated; v) level of actual or potential harm to competition, the economy, consumers and other third parties; vi) detrimental effects to the economy; vii) economic situation of the defendant; viii) recidivism (if defendant has a prior history of anticompetitive behavior, fines can be doubled). The level of fines when the case is supported with direct evidence tend to be higher. Also, payment of antitrust fines does not release defendant from having to repair damages in a potential private lawsuit56.

Besides being an administrative offense, cartel is also considered a crime punishable by imprisonment. Usually, the penalty ranges from 2 to 5 years but it may increase by up to 50% if illegal conduct caused serious harm to consumers or were active in markets essential to life. In recent years, antitrust authorities have also been encouraging damage litigation by potential injured parties leading to a surge in class actions aimed at the recovering of collective or individual damages. By encouraging victims to claim damages, the CADE is able to amplify its deterrence effect. CADE's function are restricted to preventing and repressing anticompetitive conducts, therefore it is not concerned with the measurement and quantification of actual damage that may have been caused by an offender; damage recovery is addressed in private class or individual actions. Victims of anticompetitive behavior are allowed to file suit even of CADE has decided no violation has occurred, and they do not have to wait for CADE's final decision.

55 Duarte, Leonardo Maniglia and Rodrigo Alves dos Santos, Overview of Competition Law in Brazil, "Cartel Settlements in Brazil: Recent Developments and Upcoming Challenges," São Paulo:IBRAC/Editora Singular, 2015, pp. 285-313

56 Martinez, Ana Paula and Mariana Tavares de Araujo, Overview of Competition Law in Brazil, "Anti-cartel Enforcement in Brazil: Status Quo & Trends," São Paulo: IBRAC/Editora Singular, 2015, pp. 257-274