BiochemicalEngineeringJournal62 (2012) 48–55

ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Biochemical

Engineering

Journal

j o u r n al hom ep ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / b e j

The

effects

of

fluoride

and

aluminum

ions

on

ferrous-iron

oxidation

and

copper

sulfide

bioleaching

with

Sulfobacillus

thermosulfidooxidans

Tácia

C.

Veloso,

Lázaro

C.

Sicupira,

Isabel

C.B.

Rodrigues,

Larissa

A.M.

Silva,

Versiane

A.

Leão

∗UniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,DepartmentofMetallurgicalandMaterialsEngineering,Bio&HydrometallurgyLaboratory,CampusMorrodoCruzeiro,s.n.,Bauxita,OuroPreto, MG,35400-000,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received11November2011 Accepted7January2012

Available online 14 January 2012

Keywords:

Batchprocessing Thermophiles Growthkinetics Fluoridetoxicity Aluminumcomplexes Wastetreatment

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

MicroorganismsthatgrowathightemperaturescanimproveFe(II)bio-oxidationandtherebyits

tech-nologicalapplications,suchasbioleachingandH2Sremoval.Conversely,elementspresentinindustrial

growthmedia,suchasfluoride,caninhibitbacterialgrowthandironbio-oxidation.Inthiswork,the

influ-enceoffluorideonthekineticsofferrous-ironbio-oxidationwithSulfobacillusthermosulfidooxidanswas

investigated.Theeffectsoffluorideconcentrations(0–0.5mmolL−1)onbothironoxidationandbacterial

growthrateswereassessed.Inaddition,theeffectoftheadditionofaluminum,whichwasintendedto

complexfreefluorideandreducetheconcentrationofHFthroughtheformationofaluminum–fluoride

complexes,wasalsoinvestigated.Theresultsshowthat0.5mmolL−1NaFcompletelyinhibitedbacterial

growthwithin60h.Nevertheless,fluoridetoxicitytoS.thermosulfidooxidanswasminimizedbycontrol

ofthealuminum–fluorideratiointhesystembecause,ata2:1aluminum–fluoridemolarratio,bacterial

growthwassimilartothatobservedintheabsenceoffluorideions.Despiteaslowerbacterialgrowth

rate,fluorideconcentrationslessthantheinhibitoryconcentrationincreasedtheFe(II)oxidationrate.

Successfulcopperbioleaching(80–100%)fromfluoride-containingsulfideores(1%totalfluoride)was

demonstratedinthepresenceofaluminum.

© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Ferrous-ironbio-oxidationhasmanytechnologicalapplications, includingbioleaching[1], whereferriciron accountsfor sulfide oxidation.MostFe(II)bio-oxidationstudieshavebeenperformed withmesophilicmicroorganismssuchasAcidithiobacillus

ferroox-idans [2] and Leptospirillum ferriphilum [3], although moderate

thermophiles and extreme thermophiles can positively impact bioleachingbecauseoffaster sulfideoxidationathigh tempera-tures.Theelectronpathwayfromferrous-irontooxygenhasbeen proposedtoincluderusticyanin in A.ferrooxidans [4] andRuBP carboxylasesinSulfobacillus[5].

ThegrowthmediumcanstronglyinfluencetheFe(II)oxidation ratebecauseindustrial solutionsmaycontainaplethora of dis-solvedelements.Duringheapbioleaching,forexample,thegangue mineralscanenrichtheleachsolutionwithelementsthatare harm-fultothebacteria,thusimpairingferrous-ironoxidationkinetics [6]. Ojumu et al. [7] have shown the effect of increased ionic strengthonmesophilicbacterialgrowth.Inadditiontoreducing

∗CorrespondingauthorTel.:+553135591102;fax:+553135591561/1596.

E-mail addresses: versiane@demet.em.ufop.br, versiane.ufop@gmail.com,

va.leao@uol.com.br(V.A.Leão).

dissolvedoxygenconcentrations,ahigherionicstrengthreduces free waterconcentration,and thebacteria therefore losewater becauseofosmoticeffects[8].AnionsaffectFe(II)andsulfur oxi-dationdifferently,butnitrateandchloridearethemostimportant inhibitorsofmesophilicbacterialgrowth[9].Suchspeciesreduce thetransmembranepotentialandenableH+ crossingofthecell membrane,therebyloweringtheinternalcellpHandimpairing growth[10].Anotherinhibitionmechanismhasbeenproposedfor speciessuchasHF,whichareelectricallyneutralatthepHvalue wherebioleachingoccurs.Afailureofaheapbioleaching opera-tionduetothepresenceoffluorideionsontheorehasrecently beenreported[11],andthisphenomenonwasexplainedbythe fluoridechemistry.AtthelowpHlevelsofbioleachingoperations, fluorideionsareconvertedintoHF,which,unlikeF−,canpenetrate thecellmembraneanddissociateintoH+andF−.Theinternalcell pH,whichisneutral,isthenloweredbyH+,whereasfluoride com-bineswithsomeenzymes.Theoverallresultistheinhibitionof bacterialgrowth[8],and,therefore,theinhibitionofferrous-iron oxidation,irrespectiveofthebacterialstrain(mesophiles, moder-atethermophilesorextremethermophiles)[12,13].

Inbioleachingoperations,inorganicweakacidssuchasHFmay bepresentintheleachingliquordependingontheoremineralogy. Becausetheprocessingoforesandconcentratesthatcontainhigh contentsofimpuritiesarebecomingcommonplace,theindustryis

1369-703X/$–seefrontmatter© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

facingthechallengeofdealingwithsuchspecies,whichare some-timespresentinhighconcentrations[14].Meanwhile,bioleaching by moderate thermophiles has been studied because sulfide oxidationisfasterandbecausethesemicroorganismsarefoundin heapleachingoperations,wheretheheaptemperatureishigh.

Theeffectsoffluorideionsonthegrowthrateofbacteria rele-vanttobioleachinghavenotbeenextensivelyaddressed.Fluoride effectsareknowntobeovercomebythepresenceofaluminum. However,theeffectsoffluorideandaluminumonbothbacterial growthand Fe(II)oxidation bySulfobacillusthermosulfidooxidans havenotyetbeenquantified.Inaddition,noconsensushasbeen reachedregardingthemainaluminum–fluoridecomplexesformed duringbioleachingoffluoride-containingores.WhereasDopson etal.[12]andSundkvistetal.[13]havesuggestedAlF2+asthemain complex,BrierleyandKuhn[11]haveproposedAlF2+asthe pre-dominantspecies.Therefore,thispaperwasundertakentoassess theimpactoffluorideionsonferrous-ironoxidationbymoderate thermophiles.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Ferrous-ironbio-oxidationexperiments

S. thermosulfidooxidans (strain DSMZ 9293) was grown in a

mediumcomposedof0.4gL−1(NH

4)2SO4,0.8gL−1MgSO4·7H2O, 0.4gL−1K

2HPO4,2.5gL−1ferrous-iron(FeSO4·7H2O)and0.1gL−1 yeastextract, at pH1.5. Thecells were maintainedthroughout the experiments in an orbital shaker (New Brunswick Scien-tific),at 50◦C and 200min−1 and wereused astheinocula for the bio-oxidationexperiments when the potential reachedthe 580–600mV(Ag/AgCl)range.

Thebio-oxidationexperiments(duplicate)wereperformedin abaffledbioreactor(NewBrunswick Scientific,BioFlo110)with 2Lofsuspensionthatcontained10%(volume)oftheinoculum.To producethesuspension,200mLoftheinoculum(notpreviously adaptedtoeitherfluorideoraluminum)wastransferredfromthe shakertothebioreactor,andgrowthmedium(supplementedwith yeastextract)wasaddedtoproduceafinalsolutionvolumeof2L thatcontainedbetween5×106and5×107cellsmL−1.ThepHwas manuallyadjustedto1.5and keptat thisvaluethroughoutthe experiment.ApHmeter(Hanna2221)andglass-membrane elec-trodecalibratedagainstpH4.0and7.0buffersolutionswasused forthepHmeasurements.ThepHwascontrolledduringthe experi-mentsbytheadditionofeitherconcentratedsulfuricacidorsodium hydroxide solution.Thetemperatureand thestirringratewere maintainedat50◦Cand300min−1 (dualRushtonimpeller,5cm diameter),respectively.Thisstirringratewasdefinedasthevalue thatproducedthehighestferrous-ironoxidationrate[15].Aeration wasprovidedbyoil-freecompressorsatarateof1Lmin−1,and 5mLsampleswereregularlywithdrawnandanalyzedfor ferrous-ironconcentrationandcellcounts.NoadditionalCO2wasaddedso thattheyeastextractwasthemaincarbonsource.

In the bioreactor experiments, both bacterial growth and ferrous-ironoxidationwereassessedinexperimentswhere fluo-rideions(NaF)wereadded.Fluorideconcentrationswerevaried from0to0.50molL−1(0–10mgL−1),inthepresenceandabsence ofaluminum(Al(OH)3)sothatthefollowingAl:Fmolarratioswere achieved:0.0:0.13;0.0:0.25;1.0:0.50;2.0:0.5and3.0:0.5,3.0:0.0.

2.2. Bioleachingexperiments

Coppersulfidebioleachingexperimentswereperformedwith twosecondaryores.Thefirstsamplecontained0.99%copper (high-grade ore), and the second contained0.73% copper (low-grade ore).Mineralogicalanalysisperformedbyopticalmicroscopyand

SEM–EDS indicated that thehigh-copper ore sample contained biotite(42.3%),magnetite(21.5%)andsilicates,especially amphi-bole(18.9%) and garnet (6.9%).In addition, thelow-copper ore containedapproximatelythesameamountofbiotite(34.9%)and amphibole(25.2%),lessmagnetite(9.5%)andmoregarnet(16.7%). Thecopper-containingmineralscomprisedbornite(36%)aswell aschalcocite(64%)inthehigh-copperore,whereasthelow-copper orecontained39%bornite,55%chalcociteand6%chalcopyrite.Both oresalsocontained0.58–0.73%chlorideand0.53–0.75%fluoride aseitherfluorite(CaF2)orfluoride-containingsilicates.Theiron andaluminumcompositionswere27.8%Feand5.0%Alinthe low-copperoreand33.7%Feand3.9%Alinthehigh-coppersample.

Thebioleachingpotentialofbothoreswasassessedin250mL Erlenmeyerflasks.Avolumeof50mLofthegrowthmedium (sup-plementedwithyeastextract)wasadjustedtotherequiredpHand transferredtotheflasks.TheamountofrequiredFe(II)wasadded asanacidsolutionthatcontained50gL−1Fe(II)(asFeSO4·7H2O). Afterwards,5goftheore(correspondingto5%(w/v)pulpdensity) wereadded,andtheflaskswereinoculatedwitha10mLaliquot ofthebacteriathatcontained1×107cellsmL−1.Finally,sufficient distilledwaterwasaddedtodilutethefinalslurrytoavolumeof 100mL.ThepHwassubsequentlyadjustedtotherequiredvalue (1.65),andtheflaskweightwasrecorded.Unlessotherwisestated 350mgL−1 and200mgL−1 Al(asaluminumsulfate)wereadded tothebioleachingtestswiththehigh-andlow-gradeores, respec-tively.Atemperature-controlledorbitalshaker(NewBrunswick) provided mixing(at200min−1).Eachflaskwassampledbythe removalofa2mLaliquotoftheleachsolution,whichwasthen used for elemental analysis. The redox potential (Digimed) (vs. Ag/AgCl reference)wasrecorded.Evaporationlosseswere com-pensatedbytheadditionofthegrowthmediumtotherecorded weight.Sterilecontrolswerealsoruninthepresenceof0.015% (v/v)methylparaben–0.01%(v/v)propylparabensolutionsasa bac-tericide.

2.3. Analysis

Cell countswere performedusinga Neubauer chamberin a light-contrast microscope (Leica). Aluminum and fluoride were analyzedbyICP–OESandionchromatography,respectively. Fer-rous ion wastitrated againsta standard potassiumdichromate solutioninthepresenceofa1H2SO4:1H3PO4solutionusingan automatictitrator(Schott-TritolineAlpha).Allchemicalsusedin thisstudywereanalytical-gradereagents(AR)unlessotherwise stated,andallsolutionswerepreparedwithdistilledwater.

StatisticalanalysiswasperformedusingtheOriginTMversion8.0 softwareprogramtodeterminethespecificgrowthrate,theFe(II) oxidationrateandtheyieldvaluesfora95%confidenceinterval. Thedatapointsusedtocalculatesuchparameterswerethosethat producedlinearregressionwithcorrelationcoefficients(r2)greater than0.95.

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. Ferrous-ironbio-oxidation

[17].Inthelag-phase,growthisessentiallyzerobecausecellsare adaptingtothenewenvironment,andnewenzymesandstructural componentsarebeingproduced.Afterthelag-phase,the bacte-rialpopulationstartstoincrease (growthphase); eventually,as nutrientsbecomedepletedorinhibitoryproductsaccumulate,the stationaryphaseisattained[17].Fluorideionshavebeenshown toimpair thegrowthof different bacterialstrains[18], includ-ingmesophilicbioleachingmicroorganisms[19].Thisresultwas alsoverifiedinthepresentworkforthegrowthofthemoderate thermophileS.thermosulfidooxidansinferrous-iron.Nobacterial growthwasobservedwithin60hduringFe(II)bio-oxidation exper-imentsperformedwith0.50mmolL−1 (10mgL−1)totalfluoride. ThisdetrimentaleffectwasobservedbecauseHFisaweakacid (pKa=3.2,at25◦Candinfinitedilution)thatexistsprimarilyasHF (98%ofthefluoride-containingspecies)atthepHutilizedinthis study(1.5). HFisa highlypermeantsolute,witha permeability throughlipidbilayermembranesthatissevenordersofmagnitude greaterthanthat ofF− [20].In acidophiles,althoughthe exter-nalsolutionisacidic,thecytoplasmicpHisneutral becausethe cytoplasmicmembrane,despiteallowingthepassageofionsand moleculestosupportmetabolism,hindersprotonsfromentering thecell.Theentryofprotonsisreducedbyaninverted transmem-branepotential(),whichcontributestotheneutralcytoplasmic pH[21].Small, uncharged molecules suchas HFcan cross the cellmembrane.Afterenteringthecell,HFdissociatesintoH+and F−,whichdecreasestheinternalpHandaffectsmicrobialgrowth accordingly[8].Growthisalsoimpairedbecausefluorideitselfcan inhibittheactivityofmanyenzymes[18].

Thedetrimentaleffectposedbyfluorideonbacterialgrowth canbeovercomebytheadditionofaluminumtothesystem[19], asdepicted in Fig. 1.Fig. 1 shows no lag-phasein the experi-mentperformedwithouteitherelement(blank).However,growth wassomewhataffectedinthepresenceof0.5mmolL−1 fluoride and2mmolL−1aluminum(Al/F=4)andalag-phasewasobserved. Whenthealuminumconcentrationwasincreasedto3mmolL−1 atthesamefluorideconcentration(Al/F=6),thislag-phase disap-peared,whichpointstothedetoxificationeffectofaluminumon fluoridetoxicity[11,12].

Attheendofthelag-phase,thebacteriaareadaptedtotheir environment,andcelldoublingstarts(theexponentialphase).If growthisnotlimited,doublingwillcontinueataconstantgrowth rate,whichcharacterizestheexponentialgrowthphase,inwhich celldoublingwillcontinueattheso-calledspecificgrowthrate(). Thisgrowthphaseappliestoclosedsystemswheregrowthisthe

0 3 6 9 12 15

15.0 15.5 16.0 16.5 17.0 17.5 18.0

blank R2 = 0.99

Al/F = 6 R2 = 0.99

Al/F = 4 R2 = 0.98

Ln (bacterial population)

Time (days)

Fig.1.BacterialcountsasafunctionoftimeforthegrowthofS.thermosulfooxidans

onFe(II)atdifferentAl/Fmolarratios.[Fe2+]

0=2.5gL−1,50◦C,10%inoculum,pH1.5,

300min−1,[F]

total=0.5mmolL−1.Blankexperiment:[Al]t=[F]t=0.

0.0:0.0 0.0:0.130.0:0.25 1.0:0.5 2.0:0.5 3.0:0.5 3.0:0.0 0.05

0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25 0.30 0.35

Specific grow

th rate (h

-1 )

Al:F molar ratio

Fig.2.Effectoffluorideandaluminumadditiononthespecificgrowthrate() duringFe(II)oxidationbyS.thermosulfidooxidans.Experimentalconditions2.5gL−1

Fe2+;0.1gL−1yeastextract;Norrisgrowthmedium,pH1.5;300min−1and50◦C.

onlyprocessthataffectscellconcentration(X)[17].AplotoflnX versustimegivesastraightlinewithslope()(Fig.1).

Thespecific growthrate ()wasdetermined frombacterial countsperformedinthebioreactor(Fig.2).Thespecificgrowth rate(0.283±0.035h−1)calculatedfortheexperimentperformed intheabsenceofbothfluorideandaluminum(blank)isconsistent withpreviousstudiesonFe(II)oxidation byS. thermosulfidooxi-dans(0.220±0.025h−1)[15].Themaximumspecificgrowthrate (max)wasdeterminedforthisbacteriumgrowninthepresence of2–20gL−1Fe(II)andthevalueof0.242h−1wasobserved[15].

As shown in Fig. 2, the presence of fluoride ions reduced the specific growth rate. At a total fluoride concentration of 0.125mmolL−1, was reduced to 0.128±0.037h−1, i.e., less than half thevalue observed in theabsence of the anion. The specificgrowthrate wasfurtherdecreased to0.085±0.028h−1 forhigherfluorideconcentrations(0.25mmolL−1),whichreflects the inhibitory effect of HF onbacterial growth [8]. When alu-minumwasalsoaddedtothebioreactor,itsdetoxificationeffect became evident.As already stated,no growthwasobserved in thepresenceof0.5mmolL−1(10mgL−1)totalfluoride.However, when 1.0mmolL−1 Al wasaddedtothis fluorideconcentration (Al/F=2),growthwasdetected,andaspecificgrowth-ratevalue of 0.091±0.034h−1 wasmeasured. Fluoride inhibition wasnot completelyovercomeatthisaluminumconcentrationbecausethe specificgrowthratewasstatisticallysimilartothoseachievedin theabsence of aluminum and at lower fluoride concentrations (0.125mmolL−1–0.25mmolL−1).Avaluesimilartothatproduced intheabsenceoffluoridewasachievedwhentheAl:Fmolarratio wasincreasedto4 (2.0mmolL−1 Al–0.50mmolL−1 F)(Fig.2). AfurtherincreaseintheAl/Fmolarratioto6(3.0mmolL−1 Al– 0.50mmolL−1F)resultedinasmallergrowthratethanwhenonly 3.0mmolL−1aluminumwaspresent.Thisparameterisagain sta-tisticallysimilartothatproducedwhennoneoftheelementswere present.TheanomalousgrowthrateobservedatAl/F=6maybe duetothepredominanceofunchargedaluminumfluoridespecies (AlF3),butthisresultrequiresfurtherinvestigation.

Thepositiveeffectofaluminumonbacterialgrowthinthe pres-enceoffluoridecanbeexplainedbyaluminum–fluoridecomplex formationEq.(1–4),whichproducesspeciesthatcannotcrossthe bacterialcellmembranes.

Al3++F−

⇆AlF2+ logˇ1= 7.01 (25◦C,I→ 0) (1)

Al3++2F−

AlF2+

AlF2+

AlF2+

AlF2+

AlF2+

AlF2+

AlSO4+

AlSO4+

AlSO4+

Al(SO4)2- Al(SO

4)2- Al(SO4)2

-0.000 0.200 0.400 0.600 0.800 1.000

2 4 6

Mol

a

r fr

acƟon

Al/F molar raƟo

Fig.3.Estimatedaluminumspeciation(molarfraction)inthepresenceofboth sulfateand fluoride ions. Conditions:25◦C, pH 1.50,infinite dilution (I→0). Totalconcentrations:0.5×10−3molL−1(fluoride);76.5×10−3molL−1 (sulfate);

44.8×10−3molL−1(ferrous-iron).Al3+,AlF

3andAlF4togetherrepresentslessthan

0.5%ofthealuminumspeciesandthereforedonotappearinthediagram.

Al3++3F−

⇆AlF3(aq) logˇ3=16.7 (25◦C,I →0) (3)

Al3++4F−

⇆AlF4− logˇ4= 19.4 (25◦C

,I→ 0) (4)

Thecompositionofthebio-oxidationsolution(aluminum,iron, fluoride and sulfate) wasused in a thermodynamicstudy per-formedtoestimatethedistributionofsolublealuminum–fluoride speciesinthesystem.Fig.3presentsthedistributionofaluminum complexesforthethreedifferentAl/Fmolarratiosstudiedinthe presentwork(atpH1.50andwith2.5gL−1Fe(II))at25◦Cand infi-nitedilution,withdataobtainedfromboththeNISTdatabase[22] andtheresultsofGimenoSerranoetal.[23].Valuesofstability constantsforthetemperatureandionicstrengthofthemoderate thermophileleachingcouldnotbefound.Therefore,actualvalues aresomewhatdifferent,butitisbelieved,however,thatthemain findingscanbeappliedtotheexperimentalconditionsstudiedhere. ThisanalysiscoversthebeginningoftheexperimentswhenFe(II) wasthemainironspecies,i.e.,ferricironconcentrationsweretoo lowtoaffectaluminum–fluoridespeciationortoformjarosite.For alltheAl/Fmolarratiosstudied,thecalculationsindicateAlF2+as thepredominantAl/Fcomplex,followedbyAlF2+(Fig.3);these resultsareconsistentwiththeworkofBrierleyandKuhn[11],who alsoindicatedAlF2+asthemainaluminum–fluoridecomplex dur-ingmesophilicbioleachingofsecondarycopperores.Nevertheless, AlF2+andAlF2+representmorethan97%ofthealuminum–fluoride complexes,andbothspecieslikelypredominateat50◦C.

Becausesulfatewasalsopresentinthereactor,Fig.3also sug-geststhatthecomplexesAlSO4+ andAl(SO4)−,whichrepresent between67%(Al/F=2)and85%(Al/F=6)ofthealuminumspecies, arealsoimportant.Thisresultis consistentwithprevious find-ings[13].Furthermore,theHFconcentrationwasdecreasedtoless than6×10−5molL−1,whichrepresentsonly12%ofthe fluoride-containing species (unlike the 98% observed in the absence of aluminum). Thedecreased HFconcentration positivelyaffected thebacterialgrowth.Insummary,fluoridecomplexationwith alu-minumreducestheHFconcentrationandpreventsfluoridefrom extensivelyenteringthemicrobialcell.

S.thermosulfidooxidansutilizesFe(II)asasubstrateforgrowth

[24]. Fig. 4 presents the Fe(II) profile in the experiments per-formedinthepresenceoffluorideandaluminum.Intheabsence ofaluminum(Fig.4a),increasedfluorideconcentrationsresulted inlongerdelays forthestartofFe(II)oxidation. Thistimespan

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 0.0

0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8

[F]tot = 0.50mmol/L

[F]tot = 0.25mmol/L [F]tot = 0.13mmol/L

[F]tot = 0.00mmol/L

(a)

[Fe

+2

] (g/L)

Time (h)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 0.0

0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8

Al:

F = 0

(0.

5mmol.L

-1F

tot

)

Al:

F = 2

Al:

F = 6

Al:

F = 4

(b)

[Fe

2+ ] (g.L -1 )

Time (h)

Fig.4. Effectoffluoride(a)andAl:Fmolarratio(b)onFe(II)oxidationbyS. thermo-sulfidooxidans.Experimentalconditions2.5gL−1Fe2+;0.1gL−1yeastextract;Norris

growthmedium,pH1.5;300min−1and50◦C.In(b),fluorideconcentrationwasset at0.50mmolL−1.

matches the lag-phase period (datanot shown), during which growthwasnotexpressiveandthereforenosubstrate consump-tionwasobserved.At0.5mmolL−1fluoride,nobacterialgrowth was observed nor was Fe(II) oxidation detected.As previously discussed,ata fluorideconcentrationof0.5mmolL−1,the addi-tionofaluminumenabledbacterialgrowth(Fig.1)andsubstrate consumption(Fig.4b);theFe(II)concentrationwasconsequently reducedwithtime.

Theyield(Y)canbedeterminedfromthechangeinbiomass con-centration(X)andsubstrateconsumption(S)[25]andtheresults areshownTable1.Higheryieldvaluesimplybettersubstrate uti-lizationbythebacteria.Inalltheexperiments,theyieldwaswithin thesameorderofmagnitude(1010cellsg−1-Fe(II)),irrespectiveof theAl:Fmolarratio.Nevertheless,theyieldwaslowerwhenonly fluoridewaspresent,whichimpliesthatenhancedmetabolic activ-ityisrequiredtosustaingrowth[16].ForSaccharomycescerevisiae, theenergy requiredtoactivatetheplasma-membraneATPases,

Table1

Effectsaluminumandfluorideadditionsontheyieldcoefficient(Y)duringFe(II) oxidationbyS.thermosulfidooxidans.Experimentalconditions2.5gL−1Fe2+;0.1gL−1

yeastextract;Norrisgrowthmedium,pH1.5;300min−1and50◦C.

Aluminum(mmolL−1) Fluoride(mmolL−1) Yield(1010cellsg−1Fe(II))

0.0 0.00 5.30±1.00

0.0 0.13 2.83±0.12

0.0 0.25 3.06±0.74

1.0 0.50 –

2.0 0.50 3.62±0.75

3.0 0.50 5.03±0.65

Table2

EffectsaluminumandfluorideadditionsontheFe(II)bio-oxidationrate.

Experimen-talconditions2.5gL−1Fe2+;0.1gL−1yeastextract;Norrisgrowthmedium,pH1.5;

300min−1and50◦C.

Aluminum(mmolL−1) Fluoride(mmolL−1) Fe2+oxidationrate(gL−1h−1)

0.0 0.00 0.179±0.019

0.0 0.13 0.323±0.047

0.0 0.25 0.426±0.042

1.0 0.50 0.118±0.009

2.0 0.50 0.128±0.006

3.0 0.50 0.146±0.014

3.0 0.00 0.140±0.009

whichpumpprotonsoutofthecell,hasbeenshowntoresultin anincreaseintherespirationratewithadecreaseincellgrowth andthuscellyield[26].Slightlyhigheryieldvalueswereobserved inthe experimentswith aluminum—aconsequence of its posi-tiveeffectonbacterialgrowth(Fig.2).Theseresultsareconsistent withthoseobservedduringferrous-ironoxidationwithA. brier-ley in two different studies. Konishi et al. [27] determined an yieldvalueof2.05×1010cellg−1inthepresenceof2.0gL−1Fe(II), whereasNematiand Harrison[28]achieved5.38×1010 cellg−1 with1.8gL−1Fe(II).

Theferrous-iron consumptionrate(d[Fe(II)]/dt)isequivalent inabsolutetermstotheFe(II)oxidationrate,andthelatterwas determinedfromtheslopeofthelinearpartoftheferrous-iron concentrationprofileshowninFig.4aandb.Thisapproachwas selectedbecausethefirst-orderkineticsmodelproposedby Franz-mann[29]didnotproducegoodfitstotheexperimentaldata.The calculatedvaluesareshowninTable2.Theferrous-ironoxidation ratewasdeterminedas0.179±0.019gL−1h−1intheabsenceof bothaluminumandfluorideions(blank);thisvalueislowerthan thatobservedbyPinaetal.[15],whodeterminedanoxidationrate of0.292±0.034gL−1h−1 inasimilarexperiment.However,this lattervalueisconsistentwiththatreportedbyWatlingetal.[30], whoinvestigatedgrowthin10gL−1Fe(II)(∼0.12gL−1h−1).It is alsoconsistentwiththegrowthofA.ferrooxidans(0.14gL−1h−1) inthepresenceof2.5gL−1Fe(II)[28],and,asexpected,higherthan thevalueobservedfor A.brierleyi(−0.053gL−1h−1)in 1.8gL−1 Fe(II)[28].

TwoadditionalimportantoutcomescanbediscernedinTable2. First,aluminumcanovercomethedetrimentaleffectposedby flu-orideions duringFe(II) oxidation by S.thermosulfidooxidans, as alreadystatedinthediscussionthatcoveredthebacterialgrowth rate.However,in theexperimentswhere thecation is present, Fe(II)oxidationratesareslightlylowerthanthoseobservedinthe absenceofbothelements(blank).Similarfindingshavenotbeen observedforthisstrain,andinhibitoryeffectshavebeenreported onlyforhigheraluminumconcentrationsandother microorgan-isms. Blight and Ralph [31] have observed a reduction in cell numbersandduplicationtimeduringferrous-ironbio-oxidation ataluminumconcentrationsgreaterthan2.7gL−1foran unidenti-fiedmesophilicculture,whereasOjumuetal.[7]observed,during Fe(II)oxidationbyL.ferriphilum,deleteriouseffectsonFe(II) oxi-dationandbacterialgrowthonlyathighaluminumconcentrations (10gL−1).

Among the results in Table 2, the effect of low fluoride concentrations on the Fe(II) oxidation rates are also note-worthy. Although the presence of fluoride induced a longer lag-phase during bacterial growth (Fig. 1), iron oxidation was faster in the presence of fluoride (Al:F ratios of 0.0:0.13 and 0.0:0.25) as soon as the exponential phase began. Iron oxida-tionreacheda rateof0.426±0.042gL−1h−1 inthepresence of 0.25mmolL−1 fluoride, whereas the rate in the blank experi-mentwas0.179±0.019gL−1h−1).Apossibleexplanationforthis behavioristheneedtoactivatecellmetabolismasaresistance

mechanismtothepresenceoflowconcentrationsoffluoride[16], forwhichthegrowthrateisdecreasedandthelengthofthe lag-phaseisextended.Itisthereforeproposedthatthedecreaseincell internalpH(causedbyHFdiffusion)forcesthesystemtopump protonsout(increasedATPaseactivity)tobalancethediffusionof theHFmoleculesintothecell.Overall,theenergyrequirementsare increased,whichresultinanincreasedsubstrateconsumptionrate withoutanincreaseinbiomassyield,asobservedinotherstudies [32].

Becausefluoridetoxicitycanbeovercomebythepresenceof aluminumduringFe(II)bio-oxidationbyS.thermosulfidooxidans, bioleachingexperiments wereperformedwithtwocopperores thatcontainedfluorideintheirgangueminerals[14].

3.2. Bioleachingexperiments

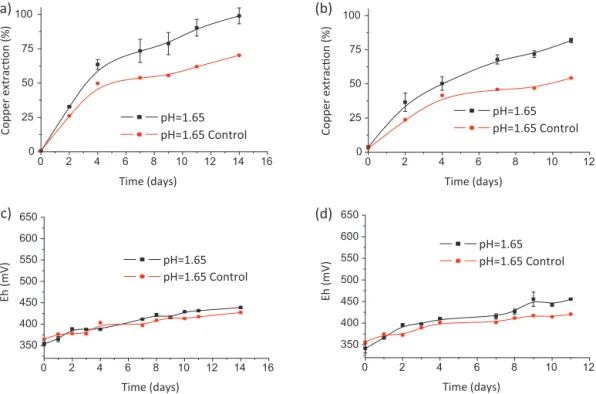

Two different secondary copper sulfide ores that comprise mainlychalcocite,borniteandchalcopyriteasaminorphasewere bioleachedwithS.thermosulfidooxidansat50◦C inthepresence of1gL−1 Fe(II)toensureafastincreaseinsolutionpotential.An externalferrous-ironadditionwaslaterfoundnottoberequired becauseirondissolutionfromtheoresprovidedenoughsubstrate forbacterialgrowth[14].Bothsamplescontainedmorethan90% cyanide-solublecopper[14],i.e.,copperthatiseasilyamenableto bioleaching[33].Becauseoftheobservedrapidferrous-iron oxi-dationbythebacterium(Fig.4),asharpincreaseinthesolution potentialwasexpectedduringtheseexperiments.Nevertheless, althoughtherewassignificantcopperextractioninboththebiotic andabioticsystems,ferric-andferrous-ironconcentrationswere similar to those achieved in the control experiment (data not shown),andpulppotentialvalueswereneverhigherthan450mV (Ag/AgCl),asshowninFig.5.Similarresultshavebeenreported duringbioleachingof achalcopyriteorethatcontainedfluoride [6].These resultsshouldbe comparedwith, for example,those observedduringnickelsulfidebioleachingwiththesamestrain, wherepotentialsashighas600mV(Ag/AgCl)wereobserved[24]. Therefore, someharmful substance might have beenimpairing bioleaching.Fig.5alsoshowsdifferentcopperextractionsfromthe high-gradeoreforboththebiotic(100%)andabiotic(75%) experi-ments.Thisbehaviorwasalsoobservedwiththelow-gradeore,but withslightlyloweryields(80%and60%forthebioticandabiotic experiments,respectively),whichmightbeduetothepresenceof chalcopyriteinthelow-gradeore[14].

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 0

25 50 75 100

(a)

Copper extracƟon (%)

Time (days) pH=1.65 pH=1.65 Control

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

0 25 50 75 100

(b)

Copper extracƟon (%)

Time (days) pH=1.65 pH=1.65 Control

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 350

400 450 500 550 600 650

(c)

Eh (mV)

Time (days) pH=1.65 pH=1.65 Control

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

350 400 450 500 550 600 650

(d)

Eh (mV)

Time (days) pH=1.65 pH=1.65 Control

Fig.5.Copperextraction(a)and(b)andsolutionpotential(Ag/AgCl)(c)and(d)duringtheexperimentswiththehigh-grade(a)and(c)andlow-grade(b)and(d)copper oresintheabscenceofaddedaluminumions.Experimentalconditions:5%solids;75–53m;pH1.65;1gL−1Fe2+;200min−1,10%Norris(v/v),0.1gL−1yeatextractand 50◦C.

Aspreviouslyshown,aluminumcanovercomethe detrimen-taleffectsoffluorideonFe(II)oxidation,althoughtheamountof aluminumdissolvedfromtheoredidnotensuresuitable condi-tionsforbacterialgrowth.Therefore,anewseriesofexperiments wereperformedinthepresenceofanexternalsourceofaluminum,

i.e., 350mgL−1 and 200mgL−1 Al were addedto the bioleach-ing tests withthe high- and low-gradeores, respectively. This externalsourceofAlensuredanAl/Fmolarratioofatleast1.5 duringbioleaching,whichwasshowntoenablebacterialgrowth onferrous-iron(Section1)andtoincreasethesolutionpotentialto

0 4 8 12 16

0 25 50 75 100

(a)

Biotic

Abiotic

Copper extraction (%)

Time (days)

0 4 8 12

0 25 50 75 100

(b)

Biotic

Abiotic

Copper extraction (%)

Time (days)

0 4 8 12 16

300 350 400 450 500 550 600

Abiotic

Biotic

(c)

Eh (mV)

Time (days)

0 4 8 12

300 350 400 450 500 550 600

(d)

Biotic

Abiotic

Eh (mV vs Ag/AgCl)

Time (days)

600mV[14].Fig.6depictsthevaluesachievedforcopper extrac-tionsandthesolutionpotentialsforbothores.Inthepresenceof aluminum,thepotentiallevelsoutinthe500–550mV(Ag/AgCl) rangewithinfivedays.Thesepotentialsareapproximately150mV higherthanthevalueobservedinthecontrolexperiments(Fig.6c andd), whichconfirms thepredictionsof Sundkvistetal. [13]. Therefore,bacterialactivitywasconfirmed.Althoughfinalcopper extractionsweresimilarintheexperimentswithout(Fig.5)and with(Fig.6)theexternaladditionofaluminum,copperextraction wasfasterinthelattercase.Forexample,forthelow-gradeore, copperextractionswere70%and50%atthefourthdayofleaching inthepresenceandabsenceofaluminum,respectively.

Theresultsshowaclearincreaseinthelag-phaseperiodwhen fluoridespecies are present duringferrous-iron oxidation by S.

thermosulfidooxidans.Becausetheproductionofferricironisthe

mainbioleachingmechanism,theonsetofmetalextractionbecame excessively longer than expected or even did not occur [11]. Notwithstanding,sub-lethalfluorideconcentrationscandoublethe ferrous-ironoxidationkinetics,whichwillresultinfastersulfide oxidation.UnliketheFe(II)oxidation,bioleachingcanbeperformed atmuchhigherfluorideconcentrationsiftheorecontainselements suchasaluminumthatcancomplexfreefluorideandreducethe HFconcentrationintheleachingliquor.Ifthepresenceof fluoride-containingmineralsisdetected,extracaremustbetakenduring bioleaching,especiallywhentheleachingsolutionisrecirculated, suchasin bio-heap-leachingoperations [19]. Althoughfluoride toxicitycanbereducedbythepresenceofaluminum,the ferrous-ironoxidationratebyS.thermosulfidooxidansisslightlydecreased inthepresenceofthecation.Therefore,thebuild-upofboth ele-mentscanleadtohighionic-strengthvalues,whichcanalsoaffect bioleaching.Under theseconditions,solutionbleedingwouldbe requiredtoreducethefluoridetoxicityaswellastheionicstrength sothatbioleachingcanbeperformedproperly.

4. Conclusions

AtthepHlevelstypicallyfoundinbioleachingoperations, fluo-rideionscanadverselyaffectthegrowthofS.thermosulfidooxidans becauseofthepredominanceofHFspeciesinsolution.The bac-terialspecificgrowthratewasdecreasedfrom0.283±0.035h−1 in experiments without fluoride to 0.085±0.028h−1 when 0.25mmolL−1totalfluoridewaspresent.Suchdetrimentaleffects canbeovercomebythepresenceofaluminum(1mmolL−1Al– 0.5mmolL−1F)whichformsAlF2+complexesthatreducetheHF concentrationand thefluoridetoxicity accordingly. This reduc-tionin toxicity resultsin specificgrowth-ratevalues similarto those observed in theabsence of both aluminum and fluoride. Despite the increase in the lag-phase period, sub-lethal fluo-rideconcentrationscatalyzeferrous-ironoxidation,whichreaches 0.426±0.042gL−1h−1with0.25mmolL−1totalfluoride.The pos-itiveeffectofaluminumonthebioleachingofcoppersulfideores that contain fluoride wasdemonstrated, and at least80% cop-perextractionwasachieved.Overall,forthoseoresthatcontain fluoride-containingminerals,bioleachingcanbeperformedif alu-minumsourcesarepresentoraddedtothebioleachingsystem.In heapbioleachingapplications,thebuild-upofaluminumand fluo-ridecanleadtofailuresduetohigh-ionic-strengthconstraints,and regularsolutionbleedingsmayberequired.

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the funding agencies FINEP, FAPEMIG,CNPqand CAPES is gratefully appreciated.The “Con-selhoNacionaldePesquisas”(CNPq)scholarshiptoV.A.Leãoisalso acknowledged.

References

[1] J.Petersen,D.G.Dixon,Principles,mechanismsanddynamicsofchalcocite heapbioleaching,in:E.R.Donati,W.Sand(Eds.),MicrobialProcessingofMetal Sulfides,Springer,Dordrecht,TheNetherlands,2007,pp.193–218.

[2] A.Mazuelos,F.Carranza,R.Romero,N.Iglesias,E.Villalobo,OperationalpHin packed-bedreactorsforferrousionbio-oxidation,Hydrometallurgy104(2010) 186–192.

[3]T.V.Ojumu,G.S.Hansford,J.Petersen,Thekineticsofferrous-ironoxidation byLeptospirillumferriphilumincontinuousculture:theeffectoftemperature, Biochem.Eng.J.46(2009)161–168.

[4] P.Ramírez,N.Guiliani,L.Valenzuela,S.Beard,C.A.Jerez,Differential pro-teinexpressionduringgrowthofAcidithiobacillusferrooxidansonferrousiron, sulfur compounds,ormetal sulfides,Appl.Environ.Microbiol. 70 (2004) 4491–4498.

[5] I.A.Tsaplina,E.N.Krasilnikova,A.E.Zhuravleva,M.A.Egorova,L.M.Zakharchuk, N.E. Suzina, V.I. Duda, T.I. Bogdanova, I.N. Stadnichuk, T.F. Kondrat’eva, Phenotypic propertiesofSulfobacillusthermotolerans:comparativeaspects, Mikrobiologiia77(2008)738–748.

[6]M.Dopson,L.Lövgren,D.Boström,Silicatemineraldissolutioninthepresence ofacidophilicmicroorganisms:implicationsforheapbioleaching, Hydromet-allurgy96(2009)288–293,doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2008.11.004.

[7]T.V.Ojumu,J.Petersen,G.S.Hansford,Theeffectofdissolvedcationson micro-bialferrous-ironoxidationbyLeptospirillumferriphilumincontinuousculture, Hydrometallurgy94(2008)69–76,doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2008.05.047. [8] I.Suzuki,D.Lee,B.Mackay,L.Harahuc,J.K.Oh,Effectofvariousions,pH,and

osmoticpressureonoxidationofelementalsulfurbyThiobacillusthiooxidans, Appl.Environ.Microbiol.65(1999)5163–5168.

[9]L.Harahuc,H.M.Lizama,I.Suzuki,Selectiveinhibitionoftheoxidationof fer-rousironorsulfurinThiobacillusferroxidans,Appl.Environ.Microbiol.66(2000) 1031–1037.

[10]I.R.Booth,RegulationofcytoplasmicpHinbacteria,Microbiol.Rev.49(1985) 359–378.

[11] J.A.Brierley,M.C.Kuhn,Fluoridetoxicityinachalcocitebioleachheapprocess, Hydrometallurgy104(2010)410–413,doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2010.01.013. [12]M. Dopson, A.-K. Halinen, N. Rahunen, D. Boström, J.-E. Sundkvist, M.

Riekkola-Vanhanen, A.H. Kaksonen, J.A. Puhakka, Silicate mineral disso-lution during heap bioleaching, Biotechnol. Bioeng. 99 (2008) 811–820, doi:10.1002/bit.21628.

[13]J.E.Sundkvist,Å.Sandström,L.Gunneriusson,E.B.Lindström,Fluorine toxic-ityinbioleachingsystems,in:S.T.L.Harrison,D.E.Rawlings,J.Petersen(Eds.), InternationalBiohydrometallurgySymposium,CapeTown,SouthAfrica, Else-vier,2005,pp.19–28.

[14]L. Sicupira, T. Veloso, F. Reis, V. Leão, Assessing metal recovery from low-grade copper ores containing fluoride, Hydrometallurgy109 (2011) 202–210.

[15] P.S.Pina,V.A.Oliveira,F.L.S.Cruz,V.A.Leão,Kineticsofferrousiron oxida-tionbySulfobacillusthermosulfidooxidans,Biochem.Eng.J.51(2010)194–197, doi:10.1016/j.bej.2010.06.009.

[16] M.E.Esgalhado,A.T.Caldeira,J.C.Roseiro,A.N.Emery,Sublethalacidstress anduncouplingeffectsoncellgrowthandproductformationinXanthomonas campestriscultures,Biochem.Eng.J12(2002)181.

[17]P.M.Doran,BioprocessEngineeringPrinciples,AcademicPress,SanDiego,CA, USA,1995.

[18]R.E.Marquis,S.A.Clock,M.Mota-Meira,Fluorideandorganicweakacidsas modulatorsofmicrobialphysiology,FEMSMicrobiol.Rev.26(2003)493–510, doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2003.tb00627.x.

[19]J.A.Brierley,M.C.Kuhn,Fromlaboratorytoapplicationheapbioleachornot, in:E.Donati,M.R.Vieira,E.L.Tavani,A.Giaveno,T.L.Lavalle,P.Chiacchiarini (Eds.),IBS09–InternationalBiohydrometallurgySymposium,Bariloche,Trans TechPublications,2009,pp.311–317.

[20] J. Gutknecht, A. Walter, Hydrofluoric and nitric acid transport through lipid bilayer membranes, BBA-Biomembranes 644 (1981) 153–156, doi:10.1016/0005-2736(81)90071-7.

[21]J.L.Slonczewski,M.Fujisawa,M.Dopson,T.A.Krulwich,CytoplasmicpH mea-surementandhomeostasisinbacteriaandarchaea,Adv.Microb.Physiol.55 (2009).

[22]A.E.Martel,R.M.Smith,NISTCriticallySelectedStabilityConstantsof Met-alsComplexes,TheNationalInstituteofStandardsandTechnology–NIST, Gaithersburg,2003.

[23]M.J.GimenoSerrano,L.F.AuquéSanz,D.K.Nordstrom,REEspeciationin low-temperatureacidicwatersandthecompetitiveeffectsofaluminum,Chem. Geol.165(2000)167–180,doi:10.1016/s0009-2541(99)00166-7.

[24]F.L.S.Cruz,V.A.Oliveira,D.Guimarães,A.D.Souza,V.A.Leão,High tempera-turebioleachingofnickelsulfides:thermodynamicandkineticimplications, Hydrometallurgy105(2010)103–109,doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2010.08.006. [25]S.Molchanov,Y.Gendel,I.Ioslvich,O.Lahav,Improvedexperimentaland

com-putationalmethodologyfordeterminingthekineticequationandtheextant kineticconstantsofFe(II)oxidationbyacidithiobacillusferrooxidans,Appl. Environ.Microbiol.73(2007)1742–1752,doi:10.1128/aem.01521-06. [26]M.E.Esgalhado,J.C.Roseiro, M.T.AmaralCollac¸o,Kineticsofacidtoxicity

inculturesofXanthomonascampestris,FoodMicrobiol.13(1996)441–446, doi:10.1006/fmic.1996.0050.

[28]M.Nemati,S.T.L.Harrison,Acomparativestudyonthermophilicandmesophilic biooxidationofferrousiron,Miner.Eng.13(2000)19–24,doi: 10.1016/S0892-6875(99)00146-6.

[29]P.D.Franzmann,C.M.Haddad,R.B.Hawkes,W.J.Robertson,J.J.Plumb,Effectsof temperatureontheratesofironandsulfuroxidationbyselectedbioleaching bacteriaandarchaea:applicationoftheratkowskyequation,Miner.Eng.18 (2005)1304–1314,doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2005.04.006.

[30] H.R. Watling, F.A. Perrot, D.W. Shiers, Comparison of selected char-acteristics of sulfobacillus species and review of their occurrence in acidic and bioleachingenvironments, Hydrometallurgy 93(2008) 57–65, doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2008.03.001.

[31]K.R.Blight,D.E.Ralph,Aluminiumsulphateandpotassiumnitrateeffectson batchcultureofironoxidisingbacteria,Hydrometallurgy92(2008)130. [32]J.C.Roseiro,M.E.Esgalhado,A.N.Emery,M.T.Amaral-Collac¸o,Technological

andkineticaspectsofsublethalacidtoxicityinmicrobialgumproduction, J. Chem.Technol.Biotechnol. 65(1996)258–264,doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4660(199603)65:3<258::aid-jctb417>3.0.co;2-2.

[33]H.R.Watling,Thebioleachingofsulphidemineralswithemphasisoncopper sulphides– areview,Hydrometallurgy84(2006)81–108.