h tt p : / / w w w . b j m i c r o b i o l . c o m . b r /

Food

Microbiology

Microbiology

of

organic

and

conventionally

grown

fresh

produce

Daniele

F.

Maffei

a,∗,

Erika

Y.

Batalha

a,

Mariza

Landgraf

a,

Donald

W.

Schaffner

b,

Bernadette

D.G.M.

Franco

aaUniversidadedeSãoPaulo,FaculdadedeCiênciasFarmacêuticas,DepartamentodeAlimentoseNutric¸ãoExperimental,SãoPaulo,

SP,Brazil

bRutgersUniversity,SchoolofBiologicalandEnvironmentalSciences,DepartmentofFoodScience,NewBrunswick,NJ,USA

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received21September2016 Accepted5October2016 Availableonline27October2016

AssociateEditor:MarinaBaquerizo

Keywords:

Freshproduce Foodbornediseases Organicagriculture Pathogens

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Freshproduceisageneralizedtermforagroupoffarm-producedcrops,includingfruits and vegetables. Organicagriculture has beenon the rise andattracting the attention ofthe foodproductionsector,sinceituseseco-agriculturalprinciplesthatare ostensi-blyenvironmentally-friendlyandprovidesproductspotentiallyfreefromtheresiduesof agrochemicals.Organicfarmingpracticessuchastheuseofanimalmanurecanhowever increasetheriskofcontaminationbyentericpathogenicmicroorganismsandmay conse-quentlyposehealthrisks.Anumberofscientificstudiesconductedindifferentcountries havecomparedthemicrobiologicalqualityofproducesamplesfromorganicand conven-tionalproductionandresultsarecontradictory.Whilesomehavereportedgreatermicrobial countsinfreshproducefromorganicproduction,otherstudiesdonot.Thismanuscript pro-videsabriefreviewofthecurrentknowledgeandsummarizesdataontheoccurrenceof pathogenicmicroorganismsinvegetablesfromorganicproduction.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeMicrobiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Fresh produce is a generalized term for a group of farm-producedcrops,includingfruitsandvegetables.Thesefoods areanimportantcomponentofahealthydiet.Consumption offreshproduceiswidelypromotedbygovernmentalhealth agenciessinceitsuppliesessentialnutrientssuchasvitamins,

∗ Correspondingauthorat:UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,FaculdadedeCiênciasFarmacêuticas,DepartamentodeAlimentoseNutric¸ão

Experimental,Av.Prof.LineuPrestes,580,05508-000SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil. E-mail:danielemaffei@usp.br(D.F.Maffei).

minerals, dietary fiber and phytochemicalcompounds ata relativelylowcaloriedensity.Furthermore,theconsumption of fruitsand vegetables has been strongly associatedwith reducedchronicdiseases,riskofheartdiseaseandcancer.1–3

Alternativecroppingsystemshavebeendevelopedbecauseof society’sincreasingconcernsaboutthesustainabilityof con-ventionalagriculture,intensiveuseofchemicalproductsand theirpotentialrisktohumanhealthandtheenvironment.4,5

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2016.10.006

Organic agriculture has been on the rise and is attracting theattentionofthefoodproductionsectorinmanypartsof theworld,sinceitreviveseco-agriculturalprinciplesthatare potentiallymoreenvironmentallyfriendlyandmayprovide productswithfewagrochemicalresidues.6,7Organicfarming

practiceswhichuseanimalmanureasfertilizercanincrease theriskofcontaminationbyentericpathogenic microorgan-ismsand,consequently,posehealthrisksbecomingamajor concernforconsumersandgovernments.Furthermore,these foodsareoftenconsumedraw,increasingriskofinfectionif pathogensarepresent.8

Despitethegrowingdemandfororganicfreshproduceand itshealthbenefits,anumberoffoodbornediseaseoutbreaks havebeenassociatedwiththeconsumptionofthesefoods.8–14

However,thenumberofstudiesfocusingonmicrobialsafety oforganicallyproducedfoodsislow.Thismanuscriptprovides abriefreviewofthecurrentknowledgeandsummarizesdata ontheriskofpathogenicmicroorganismsinvegetablesfrom organicproduction.

Organic

farming

The organic sector has expanded recentlyworldwide, due topolicy supportand agrowing market demandfor these products.Organicfarmingcanbedefinedasanecological pro-ductionsystemthatpromotesandenhancesbiodiversityand biologicalcycleinsoil,cropandlivestock.Itisbasedon min-imal use ofoff-farm inputsand on management practices thatrestore,maintainandenhanceecologicalharmony.15The

processofcertificationisalsoimportantinorganicfarming. Certificationisintendedtoassuretheconsumersthata prod-uctmarketedasorganic wasinfactproducedaccording to organic production standards, which vary from country to country,basedontheircertifyingbodies.16

OrganicfarmingisregulatedinternationallybyCodex Ali-mentariusGuidelines[establishedbytheFoodandAgricultural OrganizationoftheUnitedNations(FAO)andtheWorldHealth Organization(WHO)]andbytheInternationalFederationof Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM)Basic Standards.17

AccordingtotheIFOAM,18theprinciplesoforganicagriculture

are:(i)health:organicagricultureshouldsustainandenhance thehealthofsoil,plant,animal,humanandplanetasoneand indivisible;(ii)ecology:organicagricultureshouldbebasedon livingecologicalsystemsandcycles,workwiththem,emulate them and helpsustain them;(iii)fairness: organic agricul-tureshouldbebuiltonrelationshipsthatensurefairnesswith regard to the common environment and life opportunities and(iv)care:organicagricultureshouldbemanagedina pre-cautionaryandresponsiblemannertoprotectthehealthand well-beingofcurrentandfuturegenerationsandthe environ-ment.

Main

sources

of

contamination

of

fresh

produce

by

foodborne

pathogens

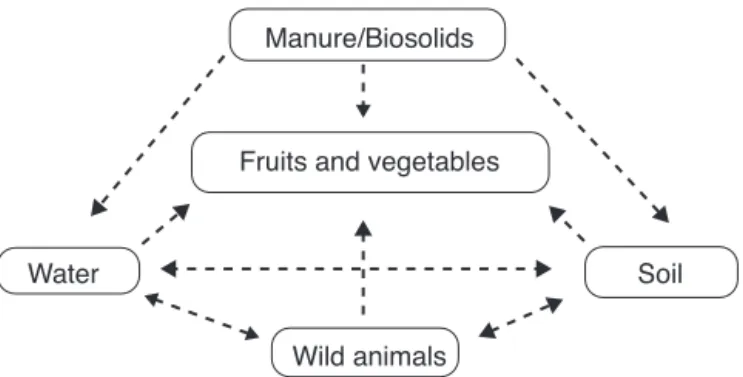

Fresh produce can become contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms duringpre-harvest (in the field) and post-harvest stages and this contamination can arise from

Manure/Biosolids

Water

Wild animals

Soil

Fruits and vegetables

Fig.1–Thesourcesandroutesofcontaminationoffruits andvegetables.

Source:ReprintedfromSant’Anaetal.20withpermission

fromElsevier.

environmental,animalorhumansources.Pre-harvestsources include soil, irrigation water, inadequately composted or raw animal manure, dust, insects, presence of wild and domesticanimalsandhumanhandling.Post-harvestsources include human handling, harvesting equipment, trans-port containers/vehicles,rinsewater, improperstorageand packaging.8,11,19,20 Fig.1illustratesthemainroutesoffresh

producecontaminationinthefield.

Thesoilisahabitatformanyorganisms,includinghuman pathogens,whichcancontaminateplantsthroughtheseeds, rootsorsurface.Bothconventionalandorganicproducecan befertilized withnaturalsourcesofnutrientssuchas ani-malmanure and plantdebris. Sinceanimal manureis the mainfertilizer typeinorganicfarming, wherenochemical treatmentagainstbacteriaisallowed,itgivesrisetoconcern aboutthepossiblecontaminationofproducewithmicrobial pathogenssuchasEscherichiacoliO157:H7,Salmonellaspp.,and

Listeriamonocytogenes.21,22 Akeystrategyusedtoreducethe

concentrationofentericpathogensinmanureiscomposting, the biologicaldecomposition oforganic matterby microor-ganismsundercontrolledconditions.23Compostcanprovide

certainbenefitstoplantswhenappliedtothesoil.If compost-ingisdoneincorrectly(i.e.fortooshortatimeorattoolow atemperature),theresultcanincreasemicrobialproliferation andriskofpathogencontamination.24,25

Theirrigationwatercanalsobeasourceof contamina-tion.Themostcommonsourcesofwaterforirrigationinclude wells,rivers, reservoirs and lakes,all ofwhichare suscep-tible tocontaminationbyhumanpathogens.Thepresence ofpathogenic microorganismsinirrigationwaterand their transfertovegetableshasbeenreported.26–28Moreover,

veg-etablecultivationinopenareasallowstheaccessofanimals (birds, insects,rodents,domestic andwild animals), which candefecateinthefieldsand,therefore,beasourceof con-tamination.StudiesconductedbyIslametal.29,30showedthat

pathogenssuchasS.TyphimuriumandE.coliO157:H7can sur-viveforalongperiodinsoil(>150days)andvegetables(>60 days)grownafterexperimentalcontaminationusing contam-inatedfertilizer(manure)orirrigationwater.

air circulation and relative humidity may be needed for pathogencontrol.Thestorageoffreshproduceunder refriger-ation(≤4◦C)isanimportantstrategytoreducethemetabolic

rate of the plant and prevent or limit the growth of pathogens.31

Pathogens

isolated

from

or

associated

with

organic

produce

Anincreasednumber offoodbornedisease outbreaks have been associated with the consumption of fresh produce recently.8–14,32AccordingtoareportbytheCenterforScience

inthePublicInterest(CSPI),freshproducewasthecauseof mostfoodborneillnessesoccurredintheU.S.between2004 and2013,including193,754illnessesfrom9,625outbreaks.33

StudieshaveisolatedpathogensincludingSalmonellaspp.,L. monocytogenesand pathogenic E. colifrom freshand fresh-cutvegetablesamplesinmanycountries.34–49 Otherstudies

havecomparedthemicrobiologicalqualityofvegetablesfrom organic and conventional production.21,22,24,50–59 Ceuppens

et al.51 assessedthe microbiologicalquality oflettuce

pro-ductioninBrazilanddetectedgenericE.colimorefrequently and at higher average concentrations in lettuce samples fromorganicfarms(23.1%and3.22logCFU/g)vs.conventional farms(16.7%and2.27logCFU/g).GomesNetoetal.52evaluated

themicrobiologicalqualityof180iceberglettucesamplesfrom conventional(n=60),organic (n=60) andhydroponic(n=60) croppingsystemsinBrazilandobservedthatsamplesfrom organicsystemswerethemostcontaminatedbothbybacteria andintestinalparasites,whilethelowestcontaminationlevel wasobservedinhydroponicallygrownlettuce.Maffeietal.24

analyzed130samplesofdifferentorganic(n=65)and conven-tional(n=65)vegetablevarieties(alsoinBrazil),andobserved thatsomeorganicvarietieshadgreatermicrobialcountswith thehighestincidenceofgeneric E.coliinorganicloose-leaf lettuce(90%ofsamplespositive).

Mukherjeeetal.55analyzed476organicand129

conven-tionalproducesamplesfromfarmsinMinnesota,USA,and foundgreaterprevalenceofE.coliinorganicvs.conventional samples.ThelargestprevalenceofE.coliwasinorganic let-tuce(22.4%ofsamples).Oliveiraetal.21 analyzed72lettuce

samplesoforganicandconventionalagricultureinSpainand foundsimilarresults,withagreaterprevalenceofE.coliin let-tucesamplesfromorganic(22.2%)thanconventional(12.5%) agriculture.Wießneretal.22investigatedtheeffectof

differ-entorganicmanuresincomparisonwithmineralfertilizeron theriskofpathogentransferinlettuceplantsinGermanyand observedthatmicrobial countstendedtobeslightlyhigher afterorganicfertilization,althoughthedifferenceswerenot statisticallysignificant(p<0.05).Althoughthesestudiesshow thatorganic producegenerallyseems tobemore contami-natedthanconventionalproduce,thiseffectwasnotseenin everystudy.

Bohaychuketal.50analyzed673freshproducesamples

col-lectedfrom Albertapublicandfarmer’s marketsinCanada (including organic produce) and observed that the levels ofE. coli in organicallyand conventionally grown produce wasnotsignificantlydifferent(p<0.05).KhalilandGomaa53

analyzed 380 samples of unpackaged whole conventional

and 84packagedwholeorganic leafygreenscollectedfrom retailmarketsinAlexandria,Egypt,andobservedthemean total bacterial count for organic samples were statistically significantly less (p<0.05) than those ofthe corresponding conventional samples and E. coli was detected in 100% of allleafygreens.Marineetal.54 evaluatedleafygreensfrom

organic(n=178)andconventional(n=191)farmsinthe Mid-AtlanticRegionoftheUnitedStates.Theyobservedthatthe farmingsystemwasnotasignificantfactorforE.coli,aerobic mesophiles orSalmonella,but with(non-statistically signifi-cant)highertotalcoliformcountsfromorganicfarmsamples. Mukherjeeetal.56conducteda2-yearstudytoevaluated

2029preharvest producesamples(473organic,911 semior-ganic, and 645 conventional) inMinnesota and Wisconsin, USA,andconcludedthatthemicrobiologicalqualityof pre-harvest produce from the three types of farms was very similar. Phillips andHarrison57 evaluatedthe microfloraof

organic(n=108)andconventional(n=108)springmixsamples obtainedfromacommercialCalifornia(USA)fresh-cut pro-ducewheremanureisnotusedinthecultivationpractices. Theauthorsobservedthatthemeanmicrobialpopulationfor conventionalsampleswasnotstatisticallydifferent(p>0.05) fromthe correspondingmeanpopulationsfororganic sam-ples. The mean population of each microbial group was significantly higher inunwashed vs. washed product. Ryu et al.58 analyzedthe microbiological quality of11 typesof

environmentally friendlyand conventionallygrown vegeta-bles sold at retail markets in Korea and did not observe significantdifference(p>0.05)inthe overallmicrobiological quality amongsamples.Tango etal.59 analyzedthe

micro-biologicalqualityof354Koreanleafyvegetablesamples(165 conventionaland189organic)andtheirresultsdidnot sup-portthehypothesisthatorganicproduceposesagreaterrisk ofpathogencontaminationvs.conventionalproduce.

OnlyCeuppensetal.,51Marineetal.,54Mukherjeeetal.55

andTangoetal.59detectedpathogenicbacteriainthefresh

producesamplesanalyzedabove.Ceuppensetal.51 isolated

Salmonellafrom oneorganic lettuce sample.Marine etal.54

isolated Salmonella from eight (2.16%) of 369 leafy greens [fourorganic(2.24%)andfourconventional(2.09%)samples]. Mukherjeeetal.55isolatedSalmonellafromoneorganiclettuce

andoneorganicgreenpeppersample.Tangoetal.59reported

positiveresultsforBacilluscereus(n=17),Staphylococcusaureus

(n=13)andL.monocytogenes(n=10)in63organicsamples,vs.3, 8and6,respectivelyforconventionalsamples.Theseauthors alsodetectedE.coliO157:H7in1outof55conventional sam-ples.

Somescientificstudieshavebeenconductedtodetermine the presenceof pathogenic bacteria exclusively in organic produce.60–67 Amongthese, onlyChanget al.,61 Loncarevic

etal.,62McMahonandWilson,64Nguzetal.65andRodrigues

etal.66detectedthepresenceofpathogenicbacteria.Chang

etal.61reportedthepresenceofE.coliO157:H7infouroutof

210organicvegetablescollectedinsupermarketandgroceries inSelangor,Malaysia.Loncarevicetal.62 isolatedL.

monocy-togenesserogroups1and4fromtwoof179organicallygrown leaf lettuce samples in Norway. McMahon and Wilson64

Table1–Incidenceofpathogenicbacteriaonorganicvegetables.

Country Pathogen Numberofsamples Reference

Total n

Positive n(%)

Brazil Salmonellaspp. 75 1(1.33) Ceuppensetal.51

Brazil Salmonellaspp. 36 1(2.77) Rodriguesetal.66

Korea B.cereus 63 17(26.9) Tangoetal.59

L.monocytogenes 63 10(15.8)

S.aureus 63 13(20.6)

Malaysia E.coliO157:H7 210 4(1.90) Changetal.61

NorthernIreland Aeromonasspp. 86 29(34.0) McMahonandWilson64

Norway L.monocytogenes 179 2(1.11) Loncarevicetal.62

USA Salmonellaspp. 178 4(2.24) Marineetal.54 USA Salmonellaspp. 476 2(0.42) Mukherjeeetal.55

Zambia L.monocytogenes 80 16(20.0) Nguzetal.65

Salmonellaspp. 160 37(23.1)

S.aureus 80 54(80.0)

Databasedonstudiesthatpresentedpositiveresults(presenceofpathogens).

including A. schubertii (21%), A. hydrophila (5.8%), A. trota

(5.8%), A. caviae (3.5%) and A. veronii biovar veronii (2.3%). These Aeromonas species were previously reported to be potentially pathogenic and responsible for gastrointestinal infectionsinhumans.68,69 Nguzetal.65assessedthe

micro-biological quality of fresh-cut organic vegetables (washed withchlorine solution at150gmL−1)produced inZambia anddetectedthepresenceofL.monocytogenes,Salmonellaand

S.aureusin20%,23.1% and 80.0% ofsamples,respectively. Rodrigues et al.66 isolated Salmonella from only one of 36

Brazilianorganiclettucesamples.

Theincidenceofpathogens inorganic vegetablesvaries according tothe study (Table 1). Salmonellaspp prevalence variesbetween0.4and23.1%,L.monocytogenesbetween1.1and 20%andS.aureusbetween20.6and80%.B.cereusprevalence canbeashighas26.9%andashighas34%forAeromonasspp.

E.coliO157:H7prevalencecanbeashighas1.9%.Sincefresh produceisoftenconsumedrawevenlowprevalenceratesmay meanincreasedriskoffoodbornediseasefromthesefoods.

Informationonfoodborneoutbreaksfromorganicproduce is limited. However, some cases involving Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) and organic produce have been reportedinthepastfewyears.AnoutbreakinvolvingSTEC O157:H7 linked to organic spinach and spring mix blend occurredintheU.S.in2012andaffected33personsfromfive states:46%werehospitalizedandtwodevelopedhemolytic uremicsyndrome(HUS).70STECO104:H4wasresponsiblefor

anoutbreaklinkedtoorganicrawsproutsinGermany,with thousandsofinfections.71,72

Control

measures

Current strategies to controlmicrobial contamination dur-ingtheproductionoffreshproduce(regardlessofcultivation method) are based on the implementation of Good Agri-cultural Practices (GAP). A GAP framework considers the implementationofbest practicesregardingworker’shealth

and hygiene, soil and water quality, sewage treatment, wildlife and livestock management, manure and biosolids management,fieldsanitationandhygiene,andharvestand transportation.20Theimplementationoffoodsafety

manage-menttoolssuchasGoodHygienicPractices(GHP)andHazard Analysisand CriticalControlPoints(HACCP)atpostharvest stepsalso helpstoreduce,eliminate or preventthe occur-rence ofhazards.The washingstep beforeconsumptionis alsoimportantasitmayreducemicrobialloadonvegetables surfaces. Washing with sanitizer may also reduce con-taminationandpreventcross-contaminationbypathogenic microorganisms.73–76

Concluding

remarks

Datasummarizedabovefromavarietyofstudiesfocusingon differentcropsanddifferentcountrieshighlightthepotential risksofpathogenicmicroorganismsinfreshproduce, includ-ing organic products. Although a number of studies have indicatedthatorganicproducemayposeagreaterriskthan conventionalgrownproduce,thistrendisnotuniversalacross allstudies.Furthereffortsareneededtounderstandand con-trol the disease riskassociated withorganic produce from harvestthroughconsumption.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.DiasJS.Nutritionalqualityandhealthbenefitsofvegetables: areview.FoodNutrSci.2012;3:1354–1374.

2.LiuRH.Health-promotingcomponentsoffruitsand vegetablesinthediet.AdvNutr.2013;4:384–392.

3.SlavinJL,LloydB.Healthbenefitsoffruitsandvegetables.

AdvNutr.2012;3:506–516.

4.BettiolW,GhiniR,GalvãoJAH,SilotoRC.Organicand conventionaltomatocroppingsystems.SciAgric. 2004;61:253–259.

5.CrowderDW,ReganoldJP.Financialcompetitivenessof organicagricultureonaglobalscale.ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 2015;112:7611–7616.

6.AzadiH,SchoonbeekS,MahmoudiH,DerudderB,DeMaeyer P,WitloxaF.Organicagricultureandsustainablefood productionsystem:mainpotentials.AgricEcosystEnviron. 2011;144:92–94.

7.WillerH,LernoudJ,eds.TheWorldofOrganicAgriculture. StatisticsandEmergingTrends.Bonn:ResearchInstituteof OrganicAgriculture(FiBL),Frick,andIFOAM–Organics International;2016.

8.BergerCN,SodhaSV,ShawRK,etal.Freshfruitand vegetablesasvehiclesforthetransmissionofhuman pathogens.EnvironMicrobiol.2010;12:2385–2397. 9.CallejónRM,Rodríguez-NaranjoMI,UbedaC,

Hornedo-OrtegaR,Garcia-ParrillaMC,TroncosoAM. Reportedfoodborneoutbreaksduetofreshproduceinthe UnitedStatesandEuropeanUnion:trendsandcauses.

FoodbornePathogDis.2015;12:32–38.

10.DoyleMP,EricksonMC.Summermeeting2007–the problemswithfreshproduce:anoverview.JApplMicrobiol. 2008;105:317–330.

11.HarrisLJ,FarberJN,BeuchatLR,etal.Outbreaksassociated withfreshproduce:incidence,growth,andsurvivalof pathogensinfreshandfresh-cutproduce.ComprRevFoodSci FoodSaf.2003;2:78–141.

12.JungY,JangH,MatthewsKR.Effectofthefoodproduction chainfromfarmpracticestovegetableprocessingon outbreakincidence.MicrobBiotechnol.2014;7:517–527. 13.LynchMF,TauxeRV,HedbergCW.Thegrowingburdenof

foodborneoutbreaksduetocontaminatedfreshproduce: risksandopportunities.EpidemiolInfect.2009;137:307–315. 14.SivapalasingamS,FriedmanCR,CohenL,TauxeRV.Fresh produce:agrowingcauseofoutbreaksoffoodborneillness intheUnitedStates,1973through1997.JFoodProt. 2004;67:2342–2353.

15.WinterCK,DavisSF.Organicfoods.JFoodSci. 2006;71:117–124.

16.VijayanG.OrganicFoodCertificationandMarketingStrategies. Agrihortico;2014.

17.TuomistoHL,HodgeID,RiordanP,MacdonaldDW.Does organicfarmingreduceenvironmentalimpacts?A meta-analysisofEuropeanresearch.JEnvironManag. 2012;112:309–320.

18.InternationalFederationofOrganicAgricultureMovements (IFOAM).ThePrinciplesofOrganicAgriculture.Bonn,Germany: Preamble.IFOAM;2005.Availableathttp://www.ifoam.org/ sites/default/files/ifoampoa.pdfAccessed06.09.16. 19.BeuchatLR.Ecologicalfactorsinfluencingsurvivaland

growthofhumanpathogensonrawfruitsandvegetables.

MicrobesInfect.2002;4:413–423.

20.Sant’AnaAS,SilvaFFP,MaffeiDF,FrancoBDGM.Fruitsand vegetables:introduction.In:BattCA,TortorelloML,eds.

EncyclopediaofFoodMicrobiology.2nded.Amsterdam: AcademicPress;2014:972–982.

21.OliveiraM,UsallJ,Vi ˜nasI,AngueraM,GatiusF,AbadiasM. Microbiologicalqualityoffreshlettucefromorganicand conventionalproduction.FoodMicrobiol.2010;27:679–684. 22.WießnerS,ThielB,KrämerJ,KöpkeU.Hygienicqualityof

headlettuce:effectsoforganicandmineralfertilizers.Food Control.2009;20:881–886.

23.MorenoJ,LópezMJ,Vargas-GarcíaMC,Suárez-EstrellaF. Recentadvancesinmicrobialaspectsofcompostproduction anduse.ActaHort(ISHS).2013;1013:443–457.

24.MaffeiDF,SilveiraNFA,CatanoziMPLM.Microbiological qualityoforganicandconventionalvegetablessoldinBrazil.

FoodControl.2013;29:226–230.

25.Suárez-EstrellaF,Vargas-GarcíaMC,ElorrietaMA,LópezMJ, MorenoJ.TemperatureeffectonFusariumoxysporumf.sp.

melonissurvivalduringhorticulturalwastecomposting.J ApplMicrobiol.2003;94:475–482.

26.ChigorVN,UmohVJ,SmithSI.OccurrenceofEscherichiacoli

O157inariverusedforfreshproduceirrigationinNigeria.

AfrJBiotechnol.2010;9:178–182.

27.IjabadeniyiOA,DebushoLK,VanderlindeM,BuysEM. Irrigationwaterasapotentialpreharvestsourceofbacterial contaminationofvegetables.JFoodSaf.2011;31:452–461. 28.OkafoCN,UmohVJ,GaladimaM.Occurrenceofpathogens

onvegetablesharvestedfromsoilsirrigatedwith contaminatedstreams.SciTotalEnviron.2003;311:49–56. 29.IslamM,DoyleMP,PhatakSC,MillnerP,JiangX.Persistence

ofenterohemorrhagicEscherichiacoliO157:H7insoilandon leaflettuceandparsleygrowninfieldstreatedwith contaminatedmanurecompostsorirrigationwater.JFood Prot.2004;67:1365–1370.

30.IslamM,MorganJ,DoyleMP,PhatakSC,MillnerP,JiangX. PersistenceofSalmonellaentericaserovarTyphimuriumon lettuceandparsleyandinsoilsonwhichtheyweregrownin fieldstreatedwithcontaminatedmanurecompostsor irrigationwater.FoodbornePathogDis.2004;1:27–35.

31.MatthewsKR.Sourcesofentericpathogencontaminationof fruitsandvegetables:futuredirectionsofresearch.Stewart PostharvestRev.2013;9:1–5.

32.SagooSK,LittleCL,WardL,GillespieIA,MitchellRT. Microbiologicalstudyofready-to-eatsaladvegetablesfrom retailestablishmentsuncoversanationaloutbreakof salmonellosis.JFoodProt.2003;66:403–409.

33.CenterforScienceinthePublicInterest.OutbreakAlert!2015: AReviewofFoodborneIllnessintheU.S.from2004–2013;2015. Availableat:https://cspinet.org/reports/outbreak-alert-2015 .pdf.Accessed25August2016.

34.AbadiasM,UsallJ,AngueraM,SolsonaC,Vi ˜nasI. Microbiologicalqualityoffresh,minimally-processedfruit andvegetables,andsproutsfromretailestablishments.IntJ FoodMicrobiol.2008;123:121–129.

35.ArthurL,JonesS,FabriM,OdumeruJ.Microbialsurveyof selectedOntario-grownfreshfruitsandvegetables.JFood Prot.2007;70:2864–2867.

36.DeLéonHB,Gómez-AldapaCA,Rangel-VargasE, Vázquez-BarriosE,Castro-RosasJ.Frequencyofindicator bacteria,SalmonellaanddiarrhoeagenicEscherichiacoli

pathotypesonready-to-eatcookedvegetablesaladsfrom Mexicanrestaurants.LettApplMicrobiol.2013;56:414–420. 37.FroderH,MartinsCG,SouzaKLO,LandgrafM,FrancoBDGM,

DestroMT.Minimallyprocessedvegetablesalads:microbial qualityevaluation.JFoodProt.2007;70:1277–1280.

38.GiustiM,AurigemmaC,MarinelliL,etal.Theevaluationof themicrobialsafetyoffreshready-to-eatvegetables producedbydifferenttechnologiesinItaly.JApplMicrobiol. 2010;109:996–1006.

minimally-processedvegetablesandbaggedsproutsfrom chainsupermarkets.JHealthPopulNutr.2014;32:391–399. 40.KovacevicM,BurazinJ,PavlovicH,KopjarM,PilizotaV.

PrevalenceandlevelofListeriamonocytogenesandother

Listeriasp.inready-to-eatminimallyprocessedand refrigeratedvegetables.WorldJMicrobBiotechnol. 2013;29:707–712.

41.MaistroLC,MiyaNTN,Sant’AnaAS,PereiraJL.

Microbiologicalqualityandsafetyofminimallyprocessed vegetablesmarketedinCampinas,SP–Brazil,asassessedby traditionalandalternativemethods.FoodControl.

2012;28:258–264.

42.MoraA,LeónSL,BlancoM,etal.Phagetypes,virulence genesandPFGEprofilesofShigatoxin-producing

EscherichiacoliO157:H7isolatedfromrawbeef,softcheese andvegetablesinLima(Peru).IntJFoodMicrobiol.

2007;114:204–210.

43.MorenoY,Sánchez-ContrerasJ,MontesRM,

García-HernándezJ,BallesterosL,FerrúsMA.Detectionand enumerationofviableListeriamonocytogenescellsfrom ready-to-eatandprocessedvegetablefoodsbycultureand DVC-FISH.FoodControl.2012;27:374–379.

44.OliveiraMA,SouzaVM,BergaminiAMM,MartinisECP. Microbiologicalqualityofready-to-eatminimallyprocessed vegetablesconsumedinBrazil.FoodControl.

2011;22:1400–1403.

45.Quiroz-SantiagoC,Rodas-SuárezOR,VázquezQCR, FernándezFJ,Qui ˜nones-RamírezEI,Vázquez-SalinasC. PrevalenceofSalmonellainvegetablesfromMexico.JFood Prot.2009;72:1279–1282.

46.RúgelesLC,BaiJ,MartínezAJ,VanegasMC,Gómez-Duarte OG.Molecularcharacterizationofdiarrheagenic

Escherichiacolistrainsfromstoolssamplesandfoodproducts inColombia.IntJFoodMicrobiol.2010;138:282–286.

47.Sant’AnaAS,IgarashiMC,LandgrafM,DestroMT,Franco BDGM.Prevalence,populationsandpheno-andgenotypic characteristicsofListeriamonocytogenesisolatedfrom ready-to-eatvegetablesmarketedinSãoPaulo,Brazil.IntJ FoodMicrobiol.2012;155:1–9.

48.Sant’AnaAS,LandgrafM,DestroMT,FrancoBDGM. PrevalenceandcountsofSalmonellaspp.inminimally processedvegetablesinSãoPaulo,Brazil.FoodMicrobiol. 2011;28:1235–1237.

49.SeoY,JangJ,MoonK.Microbialevaluationofminimally processedvegetablesandsproutsproducedinSeoul,Korea.

FoodSciBiotechnol.2010;19:1283–1288.

50.BohaychukVM,BradburyRW,DimockR,etal.A microbiologicalsurveyofselectedAlberta-grownfresh producefromfarmers’marketsinAlberta,Canada.JFood Prot.2009;72:415–420.

51.CeuppensS,HesselCT,RodriguesRQ,BartzS,TondoEC, UyttendaeleaM.Microbiologicalqualityandsafety assessmentoflettuceproductioninBrazil.IntJFood Microbiol.2014;181:67–76.

52.GomesNetoNJ,PessoaRML,QueirogaIMBN,etal.Bacterial countsandtheoccurrenceofparasitesinlettuce(Lactuca sativa)fromdifferentcroppingsystemsinBrazil.FoodControl. 2012;28:47–51.

53.KhalilR,GomaaM.Evaluationofthemicrobiologicalquality ofconventionalandorganicleafygreensatthetimeof purchasefromretailmarketsinAlexandria,Egypt.PolJ Microbiol.2014;63:237–243.

54.MarineSC,PagadalaS,WangF,etal.Thegrowingseason, butnotthefarmingsystem,isafoodsafetyriskdeterminant forleafygreensintheMid-AtlanticregionoftheUnited States.ApplEnvironMicrob.2015;8:2395–2407.

55.MukherjeeA,SpehD,DyckE,Diez-GonzalesF.Preharvest evaluationofcoliforms,Escherichiacoli,Salmonella,and

EscherichiacoliO157:H7inorganicandconventionalproduce grownbyMinnesotafarmers.JFoodProt.2004;67:

894–900.

56.MukherjeeA,SpehD,JonesAT,BuesingKM,Diez-GonzalezF. Longitudinalmicrobiologicalsurveyoffreshproducegrown byfarmersintheuppermidwest.JFoodProt.

2006;69:1928–1936.

57.PhillipsCA,HarrisonMA.Comparisonofthemicrofloraon organicallyandconventionallygrownspringmixfroma Californiaprocessor.JFoodProt.2005;68:1143–1146.

58.RyJH,KimM,KimEG,BeuchatLR,KimH.Comparisonofthe microbiologicalqualityofenvironmentallyfriendlyand conventionallygrownvegetablessoldatretailmarketsin Korea.JFoodSci.2014;79:M1739–M1744.

59.TangoCN,ChoiNJ,ChungMS,OhDH.Bacteriologicalquality ofvegetablesfromorganicandconventionalproductionin differentareasofKorea.JFoodProt.2014;77:

1411–1417.

60.BatalhaEY[M.Sc.Dissertation]Escherichiacoliprodutorade toxinadeShigaemvegetaisorgânicoscultivadosnaregião metropolitanadeSP.SãoPaulo,Brasil:FaculdadedeCiências Farmacêuticas.USP,SãoPaulo;2015,64pp.

61.ChangWS,Afsah-HejriL,RukayadiY,etal.Quantificationof

EscherichiacoliO157:H7inorganicvegetablesandchickens.

IntFoodResJ.2013;20:1023–1029.

62.LoncarevicS,JohannessenGS,RorvikLM.Bacteriological qualityoforganicallygrownleaflettuceinNorway.LettAppl Microbiol.2005;41:186–189.

63.MachadoDC,MaiaCM,CarvalhoID,daSilvaNF,Andre M.C.D.P.B.,SerafiniAB.Microbiologicalqualityoforganic vegetablesproducedinsoiltreatedwithdifferenttypesof manureandmineralfertilizer.BrazJMicrobiol.

2006;37:538–544.

64.McMahonMAS,WilsonIG.Theoccurrenceofenteric pathogensandAeromonasspeciesinorganicvegetables.IntJ FoodMicrobiol.2001;70:155–162.

65.NguzK,ShindanoJ,SamapundoS,HuyghebaertA. Microbiologicalevaluationoffreshcutorganicvegetables producedinZambia.FoodControl.2005;16:623–628.

66.RodriguesRQ,LoikoMR,dePaulaCMD,etal.Microbiological contaminationlinkedtoimplementationofgood

agriculturalpracticesintheproductionoforganiclettucein SouthernBrazil.FoodControl.2014;42:152–164.

67.SagooSK,LittleCL,MitchellRT.Themicrobiological examinationofready-to-eatorganicvegetablesfromretail establishmentsintheUnitedKingdom.LettApplMicrobiol. 2001;33:434–439.

68.IgbinosaIH,IgumborEU,AghdasiF,TomM,OkohA. EmergingAeromonasspeciesinfectionsandtheirsignificance inpublichealth.SciWorldJ.2012:1–13.

69.MerinoS,RubinesX,KnichelS,TomásJM.Emerging pathogens:Aeromonasspp.IntJFoodMicrobiol. 1995;28:157–168.

70.CentersforDiseaseControlandPrevention.Multistate OutbreakofShigaToxin-ProducingEscherichiacoliO157:H7 InfectionsLinkedtoOrganicSpinachandSpringMixBlend(Final Update);2012.Availableathttp://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2012/ O157H7-11-12/index.htmlAccessed25.08.16.

71.FrankC,WerberD,CramerJP,etal.,HUSInvestigationTeam. Epidemicprofileofshiga-toxin-producingEscherichiacoli

O104:H4OutbreakinGermany.NEnglJMed. 2011;365:1771–1780.

72.KingLA,NogaredaF,WeillFX,etal.Outbreakofshiga toxin-producingEscherichiacoliO104:H4associatedwith organicfenugreeksprouts,France,June2011.ClinInfectDis. 2012;54:1588–1594.

73.López-GálvezF,AllendeA,SelmaMV,GilMI.Preventionof

sanitizersduringwashingoffresh-cutlettuce.IntJFood Microbiol.2009;133:167–171.

74.MaffeiDF,Sant’AnaAS,MonteiroG,SchaffnerDW,Franco BDGM.Assessingtheeffectofsodiumdichloroisocyanurate concentrationontransferofSalmonellaentericaserotype Typhimuriuminwashwaterforproductionofminimally processediceberglettuce(LactucasativaL).LettApplMicrobiol. 2016;62:444–451.

75.Tomás-CallejasA,López-GálvezF,SbodioA,ArtésF, Artés-HernándezF,SuslowTV.Chlorinedioxideandchlorine effectivenesstopreventEscherichiacoliO157:H7and

Salmonellacrosscontaminationonfresh-cutRedChard.Food Control.2012;23:325–332.

76.ZhangG,MaL,PhelanVH,DoyleMP.Efficacyofantimicrobial agentsinlettuceleafprocessingwaterforcontrolof