FACULDADE DE FARMÁCIA, ODONTOLOGIA E ENFERMAGEM PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ODONTOLOGIA

JOÃO PAULO VELOSO PERDIGÃO

AVALIAÇÃO DO RISCO DE SANGRAMENTO PÓS-EXODONTIA EM PACIENTES CANDIDATOS AO TRANSPLANTE DE FÍGADO.

AVALIAÇÃO DO RISCO DE SANGRAMENTO PÓS-EXODONTIA EM PACIENTES CANDIDATOS AO TRANSPLANTE DE FÍGADO.

Dissertação submetida à Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia, da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Odontologia.

Área de Concentração: Clínica Odontológica

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fabrício Bitu Sousa

AVALIAÇÃO DO RISCO DE SANGRAMENTO PÓS-EXODONTIA EM PACIENTES CANDIDATOS AO TRANSPLANTE DE FÍGADO.

Dissertação submetida à Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia, da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Odontologia; Área de Concentração: Clínica Odontológica.

Aprovada em 01/05/2011.

BANCA EXAMINADORA

_____________________________ Prof. Dr. Fabrício Bitu Sousa (Orientador)

Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC

_____________________________ Prof. Dr. Eduardo Costa Studart Soares

Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC

_____________________________ Profa. Dra. Karem López Ortega

Ao meu pai, Ronaldo, minha mãe, Sandra, e irmãos, Rennan e Marcos (em memória), pelo apoio e incentivo durante este desafio.

À minha avó, Celina, por todas as oportunidades dadas e pela família maravilhosa que gerou.

Ao meu orientador, Prof. Fabrício Bitu, pelo conhecimento cientifico dedicado, pelas oportunidades dadas, pela amizade, paciência, incentivo e credibilidade dispensada ao longo deste convívio.

A todos os pacientes que participaram da pesquisa com a intenção de ajudar na descoberta de novos conhecimentos, a fim de proporcionar um melhor atendimento odontológico.

Aos professores, Profa. Ana Paula Negreiros, Prof. Eduardo Studart e Prof. Mário Rogério Mota, por terem contribuído com críticas e sugestões que enriqueceram muito a metodologia deste trabalho, e pelo conhecimento transmitido durante os atendimentos na Clínica de Estomatologia.

Aos colegas, Rafael Lima Verde e Saulo Batista, que contribuíram com idéias e hipóteses para a elaboração desse trabalho.

A todos os colegas do mestrado e aos colegas da estomatologia, Renata Galvão, Isabela Pacheco, Diego Peres, Malena Freitas, Carolina Teófilo e Tácio Bezerra.

A todos os acadêmicos do NEPE que auxiliaram os procedimentos cirúrgicos e contribuíram para o desenvolvimento desta pesquisa.

“Não cruze os braços diante de uma dificuldade,

pois o maior homem do mundo morreu de braços abertos.”

O transplante hepático é o tratamento padrão para pacientes com cirrose hepática e carcinoma hepatocelular. Dados do Registro Brasileiro de Transplantes (RBT) demonstraram que o transplante hepático foi o segundo órgão sólido mais transplantado em 2010. Para eliminar focos de infecção e reduzir o risco infeccioso na fase pós-transplante, esses pacientes devem passar por uma avaliação odontológica minuciosa para remoção dos focos de origem dental. No caso de procedimentos odontológicos que gerem sangramento, o cirurgião-dentista deve dar atenção especial para a hemostasia, devido, principalmente, à redução da síntese hepática de fatores da coagulação e trombocitopenia. O objetivo deste estudo prospectivo foi avaliar a incidência de hemorragia pós-operatória de exodontias em pacientes na fila de espera por um transplante de fígado. Nesse estudo foram incluídos 23 pacientes com idade média de 43,17 ± 14,62 anos com predominância da raça branca (82,6%) e do sexo masculino (60,9%). Nos 23 pacientes, 84 exodontias simples foram realizadas em 35 procedimentos cirúrgicos. Os pacientes foram divididos em dois grupos para comparação de duas medidas hemostáticas locais após as exodontias: no grupo 1, aplicou-se pressão local com gaze embebida em ácido tranexâmico, e no grupo 2, realizou-se a mesma conduta sem o uso do referido ácido. Em todos os pacientes foram utilizadas a esponja de colágeno reabsorvível e sutura em X como medida hemostática padrão. Os valores encontrados para os exames hematológicos foram: hematócrito médio de 34,54 ± 5,84% (intervalo de 21,7% – 44,4%), plaquetometria variou de 31.000/mm3 a 160.000/mm3 e o índice médio encontrado para a razão internacional normatizada (INR) foi 1,50 ± 0,39 (intervalo de 0,98 – 2,59). Sangramento pós-operatório ocorreu apenas em um procedimento (2,9%) e a pressão local com gaze foi eficaz em parar o episódio de hemorragia. Dessa forma, esse trabalho demonstra a possibilidade da realização de exodontias em pacientes com cirrose hepática com valores de INR ≤ 2,50 e plaquetometria ≥ 30.000/mm3 sem a necessidade de transfusão sanguínea e que diante da ocorrência de intercorrências hemorrágicas, o uso de medidas hemostáticas locais pode ser satisfatório.

Liver transplantation is the gold standard treatment for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The Brazilian Registry of Transplantation revealed that liver transplantation was the second solid organ most transplanted in 2010. With the purpose to eliminate foci of infection and reduce the risk of infection on the postransplant stage, these patients should undergo dental treatment to the removal of dental foci, with special care regarding the hemostasis impairment, mainly related to a reduced hepatic synthesis of procoagulants factors and thrombocytopenia. The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the incidence of postoperative bleeding after dental extraction in candidates for liver transplantation. In this study, 23 patients were included with a mean age of 43.17 ± 14.62 years, with a higher prevalence of whites (82.6%) and men (60.9%). In 23 patients, 84 simple extractions were performed in 35 dental surgical procedures. Patients were divided in two groups to compare two local hemostatic measures after tooth extraction: in group 1, local pressure after sutures was applied with gauze soaked with tranexamic acid, and in group 2, the same procedure without the tranexamic acid was performed. In all subjects, absorbable hemostatic sponges and cross sutures were used as a standard hemostatic measure. The main preoperative blood tests found were: mean hematocrit of 34.54% (SD ± 5.84%, range 21.7% – 44.4%), platelets ranged from 31,000/mm3 to 160,000/mm3, mean international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.50 (SD ± 0.39; range 0.98 - 2.59). Postoperative bleeding occurred in only one procedure (2.9%) and local pressure with gauze was effective to achieve hemostasis. Thus, this paper demonstrates the possibility of performing tooth extractions in patients with liver cirrhosis, with INR ≤ 2.50 and platelets ≥ 30,000/mm3, without the need of blood transfusion, and in case of bleeding events, the use of local hemostatic measures can be satisfactory.

1 INTRODUÇÃO GERAL ... 9

2 PROPOSIÇÃO ... 15

3 CAPÍTULO ... 16

3.1 Capítulo 1: Postoperative bleeding after tooth extraction in the pretransplant liver failure patient. ………... 17

4 CONCLUSÃO GERAL ... 38

REFERÊNCIAS ... 39

1 INTRODUÇÃO GERAL

O transplante hepático é o tratamento padrão para pacientes com cirrose hepática e carcinoma hepatocelular. Essas patologias possuem indicações semelhantes para o transplante, indiferente da etiologia, que podem ser de origem infecciosa (virais), tóxica ou imunológica, além das doenças biliares e obstrutivas. Dessas, a cirrose hepática por vírus da Hepatite C e alcoolismo crônico são as principais causas dos transplantes (GALLEGOS-OROZCO; VARGAS, 2009; O’LEARY; LEPE; DAVIS, 2008).

De acordo com o Registro Brasileiro de Transplantes, 1.413 transplantes de fígado foram realizados em 2010, representando 22,1% do total de transplantes de órgãos sólidos, atrás somente do transplante de rins com 72,3%. O Estado do Ceará foi responsável por 113 transplantes hepáticos em 2010, o segundo estado brasileiro com maior número de transplantes realizados. A equipe do Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio foi a primeira equipe cadastrada no Estado do Ceará a realizar esse transplante, sendo responsável por 91 transplantes realizados em 2010 (REGISTRO BRASILEIRO DE TRANSPLANTES, 2010).

A infecção é uma das complicações mais freqüentes e preocupantes após o transplante de fígado. Por esse motivo, os pacientes passam por avaliações em várias especialidades médicas com o objetivo de eliminar focos de infecção. Boa saúde bucal é essencial em pacientes antes e após o transplante, com o objetivo de reduzir o risco de infecção sistêmica com origem na cavidade oral (GUGGENHEIMER; MAYHER; EGHTESAD, 2005; SHEEHY et al.,1999; TENZA et al., 2009).

Alguns estudos avaliaram a saúde oral de pacientes pré-transplante hepático e encontraram higiene oral deficiente, doença periodontal avançada, cárie e lesões periapicais (BARBERO et al., 1996; DÍAZ-ORTIZ et al.,2005; NIEDERHAGEN et al.,

2003; NOVACEK et al., 1995). Trabalhos demonstram que alcoólatras tendem a

negligenciar a higiene oral como resultado de causas sociais, psicológicas e efeitos do abuso de álcool, o que leva a uma maior incidência de doenças de origem dentária (NOVACEK et al., 1995; ROBB; SMITH, 1996). As necessidades de

O diagnóstico e tratamento cirúrgico dos focos de infecção (e.g. periodontite, cistos, dentes não-restauráveis ou abscessos) são recomendados na avaliação odontológica pré-transplante hepático, apesar de esse protocolo ser até então controverso. Idealmente, o objetivo dessas medidas para eliminar focos de sepse nos maxilares é evitar uma infecção dentária pós-operatória durante a terapia imunossupressora (GUGGENHEIMER; MAYHER; EGHTESAD, 2005). Em teoria, pacientes imunossuprimidos possuem risco importante de infecção secundária de vários órgãos via hematogênica (GUGGENHEIMER; EGHTESAD; STOCK, 2003). Vários conceitos de tratamento têm sido descritos na literatura, mas não há um protocolo uniforme, e a literatura ainda é falha em provar a relação do foco de infecção nos maxilares de origem dentária e sepse pós-operatória após o transplante (GUGGENHEIMER; EGHTESAD; STOCK, 2003; LITTLE; RHODUS, 1992).

Apesar de não existir nenhum protocolo baseado em evidência para tratamento de focos de infecção de origem dental, os pacientes devem ser orientados para remoção dos focos de infecção, antes do transplante de órgãos, com objetivo de evitar complicações locais e sistêmicas pós-transplantes, como documentados em casos individuais (GUGGENHEIMER; MAYHER; EGHTESAD, 2005; SHEEHY et al., 1999; SVIRSKY; SARAVIA, 1989).

O manejo odontológico de pacientes na fila de espera por um transplante hepático, em sua maioria com cirrose, envolve algumas considerações como: o metabolismo hepático imprevisível das drogas prescritas e administradas durante o tratamento odontológico, maior susceptibilidade para infecções e desordens na hemostasia, devido à trombocitopenia ou síntese hepática reduzida de fatores da coagulação (FIRRIOLO, 2006). A remoção de raízes residuais pode causar eventos hemorrágicos, infecções e/ou dificuldades na cicatrização pós-operatória (ADAM; HOTI, 2009; THOMSON; LANGTON, 1996; WYKE, 1987).

As complicações hemorrágicas e dificuldades na cicatrização são relatadas na literatura, variando entre 15,4% e 43% (NIEDERHAGEN et al., 2003;

PLACHETZKY et al., 1992 apud NOVACEK et al., 1995). A ocorrência de

sangramento pós-operatório após cirurgia oral em pacientes anticoagulados varia entre 1,3% e 12% (BLINDER et al., 2001; WAHL, 2000), enquanto que em pacientes

saudáveis essa incidência não passa de 0,41% (ZANON et al., 2000). O risco maior

causada pelos principais fatores etiológicos, o vírus da Hepatite C e alcoolismo crônico (NIEDERHAGEN et al., 2003).

Devido a essas complicações, autores priorizam a exodontia de focos com inflamação periapical e sintomatologia dolorosa, enquanto dentes retidos assintomáticos, tratamentos endodônticos satisfatórios e dentes cariados, devem ser preservados. Niederhagen et al. (2003) recomendam realizar somente as exodontias

necessárias e adiar procedimentos eletivos para após o transplante, devido à alta taxa de complicações. Enquanto Little & Rhodus (1992) recomendam que pacientes com doença periodontal avançada, dentes com cáries extensas, ou dentes com doença periapical aguda ou crônica, em pacientes que demonstram pouco interesse ou capacidade na preservação dos dentes, são melhores tratados com remoção de todos os dentes e confecção de próteses totais.

O manejo das coagulopatias e plaquetopenias é realizado com medidas hemostáticas sistêmicas e/ou locais, com o intuito de reduzir a incidência de complicações hemorrágicas. Dentre as medidas sistêmicas estão as transfusões com plasma fresco congelado e concentrado de plaquetas. Medidas hemostáticas locais (e.g. pressão local com compressa de gaze, esponja de colágeno reabsorvível, soluções locais antifibrinolíticas, sutura, cola de fibrina e cola de cianoacrilato) também podem ser úteis em reduzir as complicações hemorrágicas associadas a procedimentos odontológicos (FIRRIOLO, 2006; RAKOCZ et al.,

1993). Blinder et al. (1999) relataram que nenhuma medida hemostática local

demonstrou ser superior a outra e que seria indiferente a sua escolha.

Uma das medidas hemostáticas locais estudadas na literatura é a esponja de colágeno reabsorvível, sutura e pressão local com compressa com gaze embebida em ácido tranexâmico. As vantagens dessa medida local são suas propriedades biodegradáveis, custo relativamente baixo, capacidade de ajudar na ativação da cascata da coagulação e possibilidade de ser aplicada em superfícies úmidas (CAMPBELL; ALVARADO; MURRAY, 2000; SAMUEL; ROBERTS; NIGAM, 1997). O ácido tranexâmico é um potente inibidor da fibrinólise, ao inibir a ligação da fibrina à plasmina, e pode ser administrado de forma sistêmica ou tópica. Esse agente antifibrinolítico é um dos fármacos mais discutidos para pacientes com alterações na coagulação sanguínea, com objetivo de reduzir o sangramento após exodontias (BLINDER et al., 1999; BLINDER et al., 2001; CARTER; GOSS, 2003). A associação

sido uma combinação comprovada em estudos recentes, pois o efeito inibidor da fibrinólise com o efeito mecânico da presença da esponja no alvéolo tem se mostrado eficaz na hemostasia após exodontias (RAMLI; RAHMAN, 2005; REICH et al., 2009). O uso do ácido tranexâmico em bochechos ou embebido na gaze tem

sido comprovado como uma medida hemostática local isolada ou em conjunto com outras medidas locais após exodontias em pacientes anticoagulados (BLINDER et al., 1999; BLINDER et al., 2001; CARTER;GOSS, 2003; CARTER et al. 2003;

ZANON et al., 2003). Entretanto, Patatanian & Fugate (2006) relataram que o

bochecho de ácido tranexâmico apresenta pouco ou nenhum efeito em reduzir a incidência de sangramento pós-operatório de exodontias em pacientes anticoagulados.

Devido ao risco hemorrágico, a avaliação pré-operatória é mandatória para garantir o sistema da coagulação satisfatório. Na avaliação pré-operatória deve-se incluir o hemograma completo, tempo de protrombina (TP), razão normalizada internacional (INR) e tempo parcial de tromboplastina ativada (TTPa) (DOUGLAS et al., 1998).

Os pacientes com doença hepática podem apresentar anemia, redução na produção de fatores da coagulação por disfunção na síntese hepática, depleção do armazenamento de vitamina K devido à desnutrição ou absorção intestinal reduzida, atividade fibrinolítica aumentada por deficiência de inibidores da fibrinólise e trombocitopenia, devido ao seqüestro esplênico relacionado à hipertensão portal e supressão na medula óssea induzida pelo álcool (O’LEARY; LEPE; DAVIS, 2009; TRIPODI, 2009). Dessa maneira, caracteriza-se que a complexidade do defeito hemostático nesses indivíduos é maior que em pacientes anticoagulados.

O hematócrito baixo, que representa um déficit na concentração de células vermelhas no sangue e pode ser encontrado nesses pacientes, tem sido relacionado ao aumento do tempo de sangramento, mesmo em pacientes com contagem normal de plaquetas (ANAND; FEFFER, 1994; EUGSTER; REINHART, 2005; QUAKNINE-ORLANDO et al. 1999; VALERI; KHURI; RAGNO, 2007). Escolar et al. (1988)

Não há um protocolo único para a realização de procedimentos cirúrgicos em pacientes com insuficiência hepática. Porém, alguns trabalhos procuram valores pré-operatórios de referência para realizar as exodontias sem aumentar a incidência de complicações hemorrágicas. A maioria dos autores realiza estudos em um modelo de pacientes que fazem uso de anticoagulantes orais e não em pacientes com insuficiência hepática. Medidas hemostáticas locais com gaze embebida com o ácido tranexâmico ou bochecho com ácido tranexâmico, após exodontias, têm eficácia em pacientes anticoagulados com INR menor que 4. Nesses estudos, os poucos casos de hemorragia existentes estavam relacionados a dentes com inflamação em tecidos moles e problemas periodontais, e as medidas hemostáticas locais foram eficazes em parar o sangramento, sem a necessidade de internação hospitalar ou transfusão sanguínea (BACCI et al., 2010; NEMATULLAH et al., 2009;

RODRIGUEZ-CABRERA et al., 2011). Al-Mubarak et al. (2007) foram além, e

relataram que exodontias simples sem suturas podem ser realizadas com segurança em pacientes anticoagulados com INR ≤ 3,0.

Ziccardi et al. (1991) e Douglas et al. (1998), dois dos poucos autores que

revisaram protocolos para o manejo odontológico de pacientes com alterações hepáticas, recomendam que em procedimentos invasivos ou cirúrgicos com TP e/ou TTPa maior que 1,5 vezes do valor padrão ou INR igual ou maior que 3,0, deve-se considerar administração de plasma fresco congelado, que provêm fatores II, V, VII, IX, X, XI, XII e XIII. Já o Hospital Universitário da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (2005) é mais cauteloso e recomenda a administração de plasma fresco congelado quando o INR for maior que 1,8. Em relação à plaquetometria, Rose & Kay (1983) foram os primeiros a recomendar a necessidade de transfusão com concentrado de plaquetas, quando a plaquetometria for menor que 50.000/mm3, e ainda são seguidos até a atualidade. Mais recentemente, Ward & Weideman (2006) relataram uma incidência de hemorragia em apenas 6% dos pacientes pré-transplante de fígado que realizaram exodontias simples, sem necessidade de transfusão em pacientes com INR ≤ 4 e plaquetometria ≥ 50.000/mm3, e com transfusão para pacientes com INR > 4 ou plaquetometria < 50.000/mm3.

Apesar da exposição acima de protocolos para avaliação pré-operatória, Tripodi et al. (2007) tentaram reunir na literatura trabalhos que comprovassem a

hepática. Segundo Tripodi et al. (2007), a deficiência de fatores anticoagulantes, que

também ocorre na doença hepática, pode balancear a deficiência de fatores procoagulantes, demonstrado pelos resultados elevados de TP/INR, e não alterar o processo hemostático nestes pacientes. Também ressaltaram que o TP não apresentou relação com sangramentos gastrointestinais e risco de sangramento, após biópsia de fígado em pacientes com doença hepática, baseada em evidência científica em mais de 20 anos.

2 PROPOSIÇÃO

2.1 Objetivo Geral

Avaliar a incidência de sangramento pós-exodontia em pacientes transplante hepático que se submeteram à exodontia sem transfusão pré-operatória para reposição de fator ou plaquetas.

2.2 Objetivos Específicos

Avaliar o efeito da compressão com gaze embebida em ácido tranexâmico no controle do sangramento pós-exodontia em candidatos ao transplante hepático.

Avaliar o efeito da compressão com gaze seca no controle do sangramento pós-exodontia em candidatos ao transplante hepático.

Comparar o efeito da compressão com gaze seca e embebida em ácido tranexâmico no controle do sangramento pós-exodontia em candidatos ao transplante hepático.

3 CAPÍTULO

Esta dissertação está baseada no Artigo 46 do Regimento Interno do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia da Universidade Federal do Ceará, que regulamenta o formato alternativo para dissertações de Mestrado e teses de Doutorado e permite a inserção de artigos científicos de autoria ou co-autoria do candidato (Anexo A). Por se tratar de pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos, o projeto de pesquisa desse trabalho foi submetido à apreciação do Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio da Universidade Federal do Ceará, tendo sido aprovado (Anexo B). Assim sendo, essa dissertação é composta de um capítulo, contendo manuscrito a ser submetido para publicação em revista científica, conforme descrito abaixo:

3.1 Capítulo 1:

“Postoperative bleeding after dental extraction in the liver pretransplant patient.”

Perdigão JPV, Almeida PC, Sousa FB.

Title: Postoperative bleeding after dental extraction in the liver pretransplant patient.

Short-title: Dental extraction in the liver pretransplant patient.

Keywords: Oral Surgery; Tooth Extraction; Liver Transplantation; Dental Care for Chronically Ill; Oral Medicine.

Authors:

João Paulo Veloso Perdigão, DDS

Postgraduate Student, School of Dentistry, Federal University of Ceará, Brazil.

Paulo César de Almeida, PhD

Research Fellow, Associate Professor, Department of Health Sciences, School of Statistics, State University of Ceará, Brazil.

Fabrício Bitu Sousa, DDS, PhD

Associate Professor, Coordinator of the Study Center in Special Care Dentistry, Department of Stomatology, School of Dentistry, Federal University of Ceará, Brazil.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr Sousa: Rua Monsenhor Furtado, s/n (2nd floor)

Curso de Odontologia – Universidade Federal do Ceará Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia

Fortaleza/CE – Brasil CEP 60.430-350 Phone: +55 85 9921-7851

Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the incidence of postoperative bleeding after dental extraction in candidates for liver transplantation. Patients and Methods: A prospective cross-sectional observational study was performed with individuals awaiting liver transplantation and referred for oral health evaluation. All the subjects with dental foci that required extraction were considered in this study. Patients were included in the analysis when the blood exams were according to: platelet count ≥ 30,000/mm3 and INR ≤ 3.0. Absorbable hemostatic sponges and cross sutures were used as a standard hemostatic measure. All tooth extractions were performed without administration of blood products (platelet concentrate, fresh frozen plasma).

Introduction

Liver transplant is the gold standard therapy for patients with end-stage liver disease, also known as cirrhosis. Chronic hepatitis C and alcohol induced liver disease are the two main causes of cirrhosis in candidates for orthotopic liver transplantation.1 According to the Global Observatory on Organ Donation and Transplantation,2 liver transplantation is the second most transplanted organ and 20,300 liver transplants were performed worldwide in 2008, while Brazil ranked fourth among the most active countries with respect to the total number of transplanted organs. Meanwhile, the Brazilian Registry of Transplantation reported 1.413 liver transplantations in 2010, which represents a rate increase of 5.9% in number of procedures compared to the previous year. The state of Ceará, located in Northeastern Brazil, is one of the main states in Brazil in which a large number of transplants is performed.3 The rising number of solid organ transplants has reached the point at which health care must be extended beyond immediate issues related to transplantation procedures.4

Infection and rejection are the postoperative transplant complications of most concern and common occurrence. For this reason, medical evaluation and treatment of the foci of infection prior to organ transplantation are recommended. Despite of the discussion in the literature about the role of oral infections in postransplant complications, dental treatment for oral foci before transplantation is a good practice in order to provide oral health to the patients along the immunosuppressive therapy after the organ transplant.5-8

tooth extraction are developed in patients in anticoagulant therapy. Recently, meta-analytic studies have concluded that dental extraction in anticoagulated patients with INR ≤ 4.0 have a low incidence of postoperative bleeding.12,13 However, as previously characterized above, the complexity of hemostasis impairment in patients with liver disease is higher than in those who are under anticoagulant therapy. The risk of surgery in patients with severe coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia (defined as INR > 1.5 and platelet count <50,000/mm3, respectively) is still uncertain.9 Ward & Weideman 14 were the only authors until today to study postoperative bleeding after dentoalveolar surgery in pretransplant liver failure patients demonstrating the influence of INR and thrombocytopenia. In that retrospective study, after performing at the maximum of 10 nonimpacted teeth extractions per dental visit, an incidence of 8% of postoperative bleeding was reported among the 25 procedures in the minimal and moderate risk groups together. The authors recommended larger studies to validate their results and to indentify other risk factors, and stated that only patients requiring more 10 dental extractions are at high risk of experiencing prolonged postoperative bleeding.14

In order to answer the lack of evidence-based science to guide the dentist in the preoperative evaluation, a prospective study was developed with patients awaiting liver transplantation and requiring sanitation of oral foci. The aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence of postoperative bleeding after tooth extraction in candidates for liver transplantation.

Patients and Methods

A prospective cross-sectional observational study was performed with 23 individuals awaiting liver transplantation and referred for oral health evaluation. All patients were liver transplant candidates. Ethical approval was obtained from the local Research Ethics Committee (REC protocol nº 025.03.10) and all of the participants signed an informed consent form that included general information about the study.

prescribed to all patients were: panoramic radiograph, complete blood count, PT, INR and PTT ratio. The liver disease and the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score were recorded from the medical files. The blood samples for the study purpose were collected within 24h before tooth extraction. Patients were included in the analysis when the blood exams were according to the following values: platelet count ≥ 30,000/mm3 and INR ≤ 3.0. The preoperative blood tests were analyzed by an independent examiner, so the surgeon did not know the blood values during the procedure. In this study, all tooth extractions were performed without administration of blood products (platelet concentrate, fresh frozen plasma). Antibiotics prophylaxis was prescribed in patients with risk for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascites or neutropenia (<1,500/mm3). The protocol prescribed was according to Firriolo (2006):1 2 g of amoxicillin in addition to 500 mg of metronidazole 1 hour before the procedure.

Patients scheduled for dental extraction were randomly divided into two groups: in group 1, local pressure after sutures was applied with gauze soaked with 250 mg/ 5 ml tranexamic acid (Transamin® Nikkho, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil) and in group 2, the control, local pressure with gauze without tranexamic acid was used. Local pressure was applied continuously for 5 minutes and repeated until hemostasis was achieved. In both groups, standard procedures were performed with the use of absorbable hemostatic sponges (Hemospon® Technew, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil) introduced into the tooth socket until it was completed filled and a 3-0 silk cross suture to keep the sponge in place. Extractions were performed under local anesthesia with mepivacaine 2% epinephrine 1:100,000 (Mepivalem® AD Dentsply, Catanduva, SP, Brazil). No more than three cartridges (5.4 ml) were used in each procedure. The number of extractions per procedure was limited due to the administration of 3 cartridges of the local anesthetic solution, and, in some procedures, the extractions were performed in different quadrant sites.

All procedures were performed in an outpatient setting by one surgeon and the surgical technique was restricted to simple extractions with the use of forceps and elevators. None of the extractions required elevation of mucoperiosteal flaps, osteotomy or odontosection. Teeth with acute inflammation, such as periodontal or periapical abscess, were not considered in the analysis due to a possible interference of the inflammation process on postoperative bleeding.

patients had medical contra-indications to acetaminophen, and, in these cases, dipyrone 500 mg was prescribed according to medical recommendations. These medications were only administrated in the event of postoperative pain, limited to 4 pills per day. This protocol for pain control was discussed and in agreement with the liver transplant team.

Postoperative instructions sheets were given and the patients orientated to apply local pressure with gauze for 20 minutes and contact the dentist in case of bleeding. In the event of bleeding not controlled by the patient, local hemostatic maneuvers with the replacement of the absorbable hemostatic sponge, re-suture and local pressure with gauze were performed by the dentist in an outpatient setting. If the previous measures did not stop the bleeding, the patient was submitted to hospital admission and administration of blood components. Follow-up was scheduled 1 week after surgery for suture removal and postoperative evaluation with a questionnaire regarding postoperative bleeding, necessity of systemic hemostatic measures and hospital admission.

Data are presented as the mean + SD. Differences between two groups were compared using Student’s t or Mann-Whitney tests. Chi-square and likelihood ratio tests were used between the categorical variables. The analyses were performed using SPSS software (v. 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences exceeding a 95% confidence interval (p<0.05) were considered statistically significant.

Results

the tooth extraction that did not allowed the postoperative evaluation after the dental procedure.

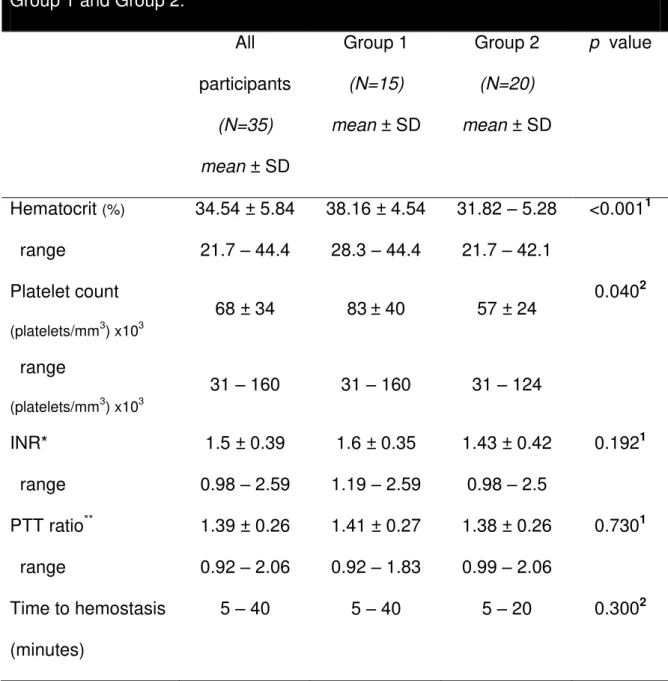

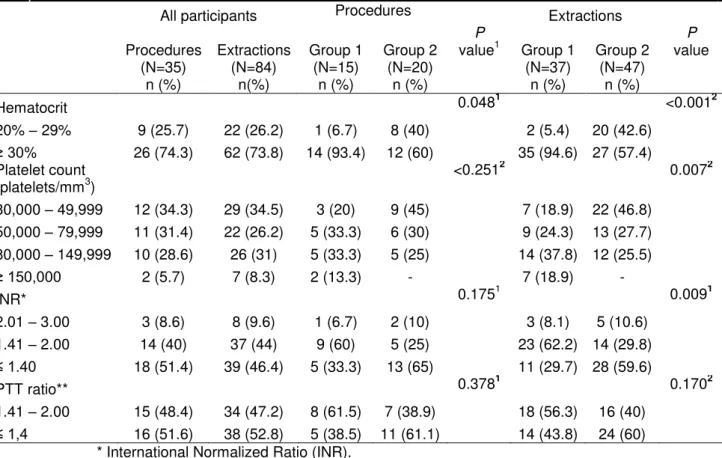

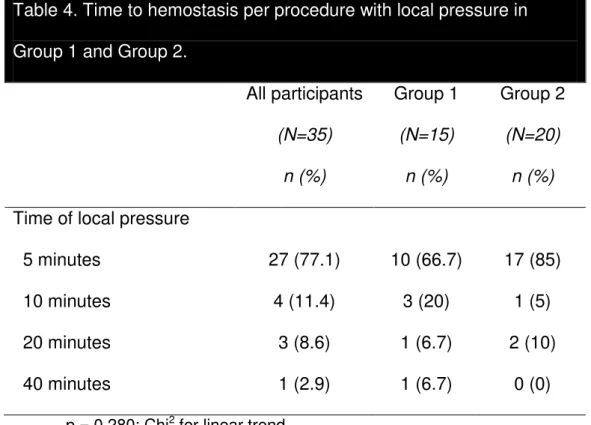

The remaining 23 patients considered in this analysis, 14 men (60.9%) and 9 women (39.1%), were submitted to a total of 35 surgical procedures to removal of dental foci. The patients were divided into two groups: 11 in group 1 and 12 patients in group 2. The mean age of all patients was 43.17 years (standard deviation, SD ± 14.62; range 20 to 67 years). The mean MELD score was 16.26 (SD ± 3.95; range 9 to 23). No statistically significant difference was found between the groups concerning the above cited characteristics. The most prevalent indication for liver transplantation was liver cirrhosis (87%) caused by viral hepatitis (30.4%) and alcohol consumption (26.1%). Other indications for liver transplantation were Wilson’s disease (8.7%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (4.3%). In the 35 procedures, a total of 84 dental foci were removed with a mean of 2.4 teeth per procedure (SD ± 1.00; range 1 to 4). The numbers of procedures between the groups were 15 in Group 1 and 20 in Group 2. Other comparisons between groups are listed in Table 1. The mean hematocrit before the procedures was 34.54% (SD ± 5.84, range 21.7 to 44.4%), with 25.7% of the procedures performed with an hematocrit less than 30%. The platelet count ranged from 31,000 to 160,000 platelets/mm3 (mean 67,888.57 ± 33,564.38 platelets/mm3), with 34.3% of the procedures performed with a platelet count between 30,000 to 50,000 platelets/mm3. The mean INR was 1.5 (SD ± 0.39; range 0.98 to 2.59), with only 3 procedures (8.6%) performed with an INR higher than 2. The mean PTT ratio was 1.39 (SD ± 0.26; range 0.92 to 2.06) with only one procedure (3.2%) performed with PTT ratio higher than 2. In four procedures, data from PTT ratio was not available, but the remaining 31 were included in the analysis. The Tables 2 and 3 show the number of procedures, preoperative blood exams ratios and range between the groups. In all tooth extractions, hemostasis was guaranteed with the use of absorbable hemostatic sponges, cross sutures and local pressure with gauze. Time to hemostasis in 77.1% of the procedures took only 5 minutes of local pressure. No statistically significant difference in the time to hemostasis was found between the two groups (Table 4). The mean duration of each procedure, from incision to suturing, was 16.25 minutes (SD ± 8.75 minutes). Statistically significant difference between groups (P<0.05) was found in the hematocrit (P<0.001) and

platelet count (P=0.04) per patient; hematocrit (P=0.048) per procedure and the

between groups. However, these were not findings of relevance and, still, would not interfere in the demonstration of a statistical significant difference in the use of tranexamic acid in the gauze used to apply local pressure.

Postoperative bleeding occurred in one procedure (2.9%) in one patient (4.3%) three days after the tooth extraction of a maxillary first molar. The preoperative blood tests of this patient were INR 2.5 and platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Local pressure with gauze for 20 minutes applied by the dentist in the ambulatory was an effective hemostatic measure.

Discussion

The prevalence of patients with liver disease requiring dental surgical intervention for oral sanitation (63.5%), found in this study, may not be addressed as a direct result of the liver disease and can be a reflection of the oral health status of the general population in Brazil, with a DMFT index of 19.6 in the population aged between 35 and 44 years living in Northeastern Brazil.15 However, this prevalence is in agreement with other studies, with the same group of patients, in a developed country like Germany, 65% and 68.4%.6,4 Anyway, the prevalence reported in this paper demonstrates the need of surgical treatment for oral foci sanitation in patients with liver disease.

The hematocrit level was recorded in order to assess if there was a relation between low hematocrit levels and increased bleeding time even in patients with normal platelet count as it was reported by previous studies.16-19 The literature describes that hematocrit levels from lower than 20% to 35% may lead to a platelet clot formation impairment independent of the platelet count.19-22 Besides the mean hematocrit values in the present study did not varied much from normal values, with only 25.7% of the procedures performed with an hematocrit lower than 30%, no bleeding episode was occurred when the procedures was performed with lower hematocrit values.

concerning coagulation blood values when evaluating the need of hospital admission and blood transfusion in patients with liver disease to perform tooth extractions.

anticoagulated patients. For this reasons, it can be said that the compression without tranexamic acid can be used as it represents a lower income to the procedure.

Despite of some guidelines concerning INR values in the preoperative evaluation, Tripodi et al 35 reported that INR have deficiencies in evaluating impairments in the coagulation cascade as anticoagulant factors, not evaluated by these tests, may also be reduced in the liver disease and can balance the deficiency of procoagulant factors. According to Tripodi et al,35 alternative tests to predict bleeding should be developed and a new international sensitivity index (ISI) for commercial thromboplastin using plasma from patients with cirrhosis instead of plasma from patients on oral anticoagulant therapy should be used. Tripodi et al 35 also suggested that the thrombin generation monitoring and thromboelastography tests may be more reliable to assess the bleeding risk in liver disease patients.

Further studies with liver transplant patients should be encouraged to help the practitioner to understand the limits of a surgical dental care intervention without the administration of blood components and not increasing the risk of postoperative bleeding. Still, it is recommended to perform these procedures in an outpatient setting only if some medical on call services is available to perform emergency local hemostatic measures or hospital admission for blood transfusion if needed.

In this study, there was no advantage of using gauze soaked with tranexamic acid to achieve hemostasis compared to the simple compression with gauze without the use of the mentioned solution. In this way, the set of local hemostatic measures with absorbable collagen sponge, cross suture and local pressure with gauze were effective to obtain hemostasis after tooth extraction in candidates for liver transplantation.

References

1. Firriolo FJ: Dental management of patients with end-stage liver disease. Dent Clin North Am 50: 563, 2006

2. GLOBAL OBSERVATORY ON DONATION AND TRANSPLANTATION. Available at: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/Pages/DataReports.aspx Accessed March 6, 2011.

3. REGISTRO BRASILEIRO DE TRANSPLANTES. São Paulo. Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgãos; Ano XVI, n. 4, Jan/Dez. 2010. Available at:

http://www.abto.org.br/abtov02/portugues/populacao/rbt/anoXV_n4/index.aspx ?idCategoria=2 Accessed March 6, 2011.

4. Rustemeyer J, Bremerich A: Necessity of surgical dental foci treatment prior to organ transplantation and heart valve replacement. Clin Oral Investig 11: 171, 2007

5. Guggenheimer J, Eghtesad B, Stock DJ: Dental management of the (solid) organ transplant patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod

95: 383, 2003

7. Guggenheimer J, Mayher D, Eghtesad B: A survey of dental care protocols among US organ transplant centers. Clin Transplant 19: 15, 2005

8. Shaqman M, Ioannidou E, Burleson J, et al: Periodontitis and inflammatory markers in transplant recipients. J Periodontol 81: 666, 2010

9. O’Leary JG, Yachimski PS, Friedman LS: Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 13: 211, 2009

10. Tripodi A. Tests of coagulation in liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 13: 55, 2009

11. Douglas LR, Douglass JB, Sieck JO, et al: Oral management of the patient with end-stage liver disease and the liver transplant patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 86: 55, 1998

12. Nematullah A, Alabousi A, Blanas N, et al: Dental surgery for patients on anticoagulant therapy with warfarin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Can Dent Assoc 75: 41, 2009

14. Ward BB, Weideman EM: Long-term postoperative bleeding after dentoalveolar surgery in the pretransplant liver failure patient. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 64: 1469, 2006

15. BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde: Projeto SB Brasil 2003: condições de saúde bucal da população brasileira 2002-2003: resultados principais. Brasília, DF,

Ministério da Saúde, 2004 Available at:

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/projeto_sb2004.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2011.

16. Anand A, Feffer SE: Hematocrit and bleeding time: an update. South Med J 87: 299, 1994

17. Eugster M, Reinhart WH: The influence of the haematocrit on primary haemostasis in vitro. Thromb Haemost 94: 1213, 2005

18. Quaknine-Orlando B, Samama CM, Riou B, et al: Role of the hematocrit in a rabbit model of arterial thrombosis and bleeding. Anesthesiology 90: 1454, 1999

20. Escolar G, Garrido M, Mazzara R, et al: Experimental basis for the use of red cell transfusion in the management of anemic thrombocytopenic patients. Transfusion 28: 406, 1988

21. Fernandez F, Goudable C, Sie P, et al: Low haematocrit and prolonged bleeding time in uraemic patients: effect of red cell transfusions. Br J Haematol 59: 139, 1985

22. Moia M, Mannucci PM, Vizzotto L, et al: Improvement in the haemostatic defect of uraemia after treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin. Lancet 2: 1227, 1987

23. Rose LF, Kay D: Internal medicine for dentistry (ed 2). St. Louis, MO, Mosby, 1983, p 425

24. Novacek G, Plachetzky U, Potzi R, et al: Dental and periodontal disease in patients with cirrhosis: role of etiology of liver disease. J Hepatol 22: 576, 1995

25. O’Leary JG, Lepe R, Davis GL: Indications for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 134:1764, 2008

27. Blinder D, Manor Y, Martinowitz U, et al: Dental extractions in patients maintained on continued oral anticoagulant: comparison of local hemostatic modalities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 88: 137, 1999

28. Bodner L, Weinstein JM, Baumgarten AK: Efficacy of fibrin sealant in patients on various levels of oral anticoagulant undergoing oral surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 86: 421,1998

29. Carter G, Goss A: Tranexamic acid mouthwash – a prospective randomized study of a 2-day regimen vs 5-day regimen to prevent postoperative bleeding

in anticoagulated patients requiring dental extractions. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 32: 504, 2003

30. Carter G, Goss A, Lloyd J, et al: Tranexamic acid mouthwash versus autologous fibrin glue in patients taking warfarin undergoing dental extractions: a randomized prospective clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61: 1432, 2003

31. Al-Mubarak S, Al-Ali N, Abou-Rass M, et al: Evaluation of dental extractions, suturing and INR on postoperative bleeding of patients maintained on oral anticoagulant therapy. Br Dent J 203: E15, 2007

33. Reich W, Kriwalsky MS, Wolf HH, et al: Bleeding complications after oral surgery in outpatients with compromised haemostasis: incidence and management. Oral Maxillofac Surg 13: 73, 2009

34. Patatanian E, Fugate SE: Hemostatic mouthwashes in anticoagulated patients undergoing dental extraction. Ann Pharmacother 40: 2205, 2006

Tables

Table 1. Number of procedures and extractions per patient in Group 1 and

Group 2.

All participants

(N=23)

mean ± SD

Group 1

(N=11)

mean ± SD

Group 2

(N=12)

mean ± SD p

value1

Number of procedures 35 15 20

Procedure per patient 1.52 ± 0.94 1.36 ± 0.50 1.66 ± 1.23 0.921

range 1 – 5 1 – 2 1 – 5

Number of extractions 84 37 47 0.574

Extractions per patient 3.65 ± 3.15 3.36 ± 2.65 3.91 ± 3.65

range 1 – 15 1 – 8 1 – 15

Extraction per procedure 2.4 ± 1.00 2.46 ± 1.18 2.35 ± 0.87 0.841

range 1 – 4 1 – 4 1 – 4

Table 2. Hematocrit, platelet count, INR and PTT ratio values per procedures in

Group 1 and Group 2.

All participants

(N=35)

mean ± SD

Group 1

(N=15)

mean ± SD

Group 2

(N=20)

mean ± SD

p value

Hematocrit (%) 34.54 ± 5.84 38.16 ± 4.54 31.82 – 5.28 <0.0011 range 21.7 – 44.4 28.3 – 44.4 21.7 – 42.1

Platelet count (platelets/mm3) x103

68 ± 34 83± 40 57 ± 24 0.040

2

range

(platelets/mm3) x103

31 – 160 31 – 160 31 – 124

INR* 1.5 ± 0.39 1.6 ± 0.35 1.43 ± 0.42 0.1921

range 0.98 – 2.59 1.19 – 2.59 0.98 – 2.5

PTT ratio** 1.39 ± 0.26 1.41 ± 0.27 1.38 ± 0.26 0.7301

range 0.92 – 2.06 0.92 – 1.83 0.99 – 2.06 Time to hemostasis

(minutes)

5 – 40 5 – 40 5 – 20 0.3002

* International Normalized Ratio (INR).

** Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT). PTT ratio value was not available in 4 subjects

and mean ± SD were calculated with the values from 31 subjects.

(1) Student’s t test;

Table 3. Hematocrit, platelet count, INR and PTT ratio ranges per procedures/extraction in Group 1 and Group 2.

All participants Procedures Extractions

Procedures Extractions Group 1 Group 2 P

value1 Group 1 Group 2

P value (N=35)

n (%) (N=84) n(%) (N=15) n (%) (N=20) n (%) (N=37) n (%) (N=47) n (%)

Hematocrit 0.0481 <0.0012

20% – 29% 9 (25.7) 22 (26.2) 1 (6.7) 8 (40) 2 (5.4) 20 (42.6)

≥ 30% 26 (74.3) 62 (73.8) 14 (93.4) 12 (60) 35 (94.6) 27 (57.4)

Platelet count

(platelets/mm3) <0.251

2 0.0072

30,000 – 49,999 12 (34.3) 29 (34.5) 3 (20) 9 (45) 7 (18.9) 22 (46.8) 50,000 – 79,999 11 (31.4) 22 (26.2) 5 (33.3) 6 (30) 9 (24.3) 13 (27.7) 80,000 – 149,999 10 (28.6) 26 (31) 5 (33.3) 5 (25) 14 (37.8) 12 (25.5)

≥ 150,000 2 (5.7) 7 (8.3) 2 (13.3) - 7 (18.9) -

INR* 0.1751 0.0091

2.01 – 3.00 3 (8.6) 8 (9.6) 1 (6.7) 2 (10) 3 (8.1) 5 (10.6) 1.41 – 2.00 14 (40) 37 (44) 9 (60) 5 (25) 23 (62.2) 14 (29.8)

≤ 1.40 18 (51.4) 39 (46.4) 5 (33.3) 13 (65) 11 (29.7) 28 (59.6)

PTT ratio** 0.3781 0.1702

1.41 – 2.00 15 (48.4) 34 (47.2) 8 (61.5) 7 (38.9) 18 (56.3) 16 (40)

≤ 1,4 16 (51.6) 38 (52.8) 5 (38.5) 11 (61.1) 14 (43.8) 24 (60)

* International Normalized Ratio (INR).

** Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT). PTT ratio value was not available in 4 subjects and

mean ± SD were calculated with the values from 31 subjects.

(1) Likelihood ratio test;

Table 4. Time to hemostasis per procedure with local pressure in

Group 1 and Group 2.

All participants

(N=35)

n (%)

Group 1

(N=15)

n (%)

Group 2

(N=20)

n (%)

Time of local pressure

5 minutes 27 (77.1) 10 (66.7) 17 (85)

10 minutes 4 (11.4) 3 (20) 1 (5)

20 minutes 3 (8.6) 1 (6.7) 2 (10)

40 minutes 1 (2.9) 1 (6.7) 0 (0)

4 CONCLUSÃO GERAL

Da avaliação dos resultados obtidos nesse trabalho, pode-se concluir que:

exodontias em pacientes com insuficiência hepática, apresentando INR ≤ 2,50 e plaquetometria ≥ 30.000/mm3, podem ser realizadas sem a necessidade de transfusão sanguínea e que diante, da ocorrência de intercorrências hemorrágicas, o uso de medidas hemostáticas locais pode ser satisfatório.

REFERÊNCIAS

ADAM, R.; HOTI, E. Liver transplantation: the current situation. Semin. Liver Dis., v. 29, n. 1, p. 3-18, Feb. 2009.

AL-MUBARAK, S. et al. Evaluation of dental extractions, suturing and INR on

postoperative bleeding of patients maintained on oral anticoagulant therapy. Br. Dent. J., v. 203, n. 7, p. E15, Oct. 2007.

ANAND, A.; FEFFER, S. E. Hematocrit and bleeding time: an update. South. Med. J., v. 87, n. 3, p. 299-301, Mar. 1994.

BACCI, C. et al. Management of dental extraction in patients undergoing

anticoagulant treatment: results from a large, multicentre, prospective, case-control study. Thromb. Haemost., v. 104, n. 5, p. 972-975, Nov. 2010.

BARBERO, P. et al. The dental assessment of the patient waiting for a liver

transplant. Minerva Stomatol., v. 45, n. 10, p. 431-439, Oct. 1996.

BLINDER, D. et al. Dental extractions in patients maintained on continued oral

anticoagulant: comparison of local hemostatic modalities. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod., v. 88, n. 2, p. 137-140, Aug. 1999.

BLINDER, D. et al.Dental extractions in patients maintained on oral anticoagulant

therapy: comparison of INR value with occurrence of postoperative bleeding. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., v. 30, n. 6, p. 518-521, Dec. 2001.

CAMPBELL, J. H.; ALVARADO, F.; MURRAY, R. A. Anticoagulation and minor oral surgery: should the anticoagulation regimen be altered? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., v. 58, n. 2, p. 131-135, Feb. 2000.

CARTER, G.; GOSS, A. Tranexamic acid mouthwash – a prospective randomized study of a 2-day regimen vs 5-day regimen to prevent postoperative bleeding in

anticoagulated patients requiring dental extractions. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., v. 32, n. 5, p. 504-507, Oct 2003.

CARTER, G. et al. Tranexamic acid mouthwash versus autologous fibrin glue in

patients taking warfarin undergoing dental extractions: a randomized prospective clinical study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., v. 61, n. 12, p. 1432-1435, Dec. 2003. DÍAZ-ORTIZ, M. L. et al. Dental health in liver transplant patients. Med. Oral Patol.

Oral Cir. Bucal, v. 10, n. 1, p. 72-76, Jan./Feb. 2005.

DOUGLAS, L. R. et al. Oral management of the patient with end-stage liver disease

ESCOLAR, G. et al. Experimental basis for the use of red cell transfusion in the

management of anemic thrombocytopenic patients. Transfusion, v. 28, n. 5, p. 406-411, Sep./Oct. 1988.

EUGSTER, M.; REINHART, W. H. The influence of the haematocrit on primary haemostasis in vitro. Thromb. Haemost., v. 94, n. 6, p. 1213-1218, Dec. 2005. FERNANDEZ, F. et al. Low haematocrit and prolonged bleeding time in uraemic

patients: effect of red cell transfusions. Br. J. Haematol., v. 59, n. 1, p. 139-148, Jan. 1985.

FIRRIOLO, F. J. Dental management of patients with end-stage liver disease. Dent. Clin. North Am., v. 50, n. 4, p. 563-590, Oct. 2006.

GALLEGOS-OROZCO, J. F.; VARGAS, H. E. Liver transplantation: from Child to MELD. Med. Clin. North Am., v. 93, n. 4, p. 931-950, July 2009.

GUGGENHEIMER, J.; EGHTESAD, B.; STOCK, D. J. Dental management of the (solid) organ transplant patient. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod., v. 95, n. 4, p. 383-389, Apr. 2003.

GUGGENHEIMER, J.; MAYHER, D.; EGHTESAD, B. A survey of dental care protocols among US organ transplant centers. Clin. Transplant., v. 19, n. 1, p. 15-18, Feb. 2005.

HOSPITAL UNIVERSITÁRIO DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA. Manual para Uso Racional do Sangue. Projeto hospitais sentinela/ANVISA. 1.ed. Florianópolis, 2005.

LITTLE, J. W.; RHODUS, N. L. Dental treatment of the liver transplant patient. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol., v. 73, n. 4, p. 419-426, Apr. 1992.

MOIA, M. et al. Improvement in the haemostatic defect of uraemia after treatment

with recombinant human erythropoietin. Lancet, v. 2, n. 8570, p. 1227-1229, Nov. 1987.

NEMATULLAH, A. et al. Dental surgery for patients on anticoagulant therapy with

warfarin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Can. Dent. Assoc., v. 75, n. 1, p. 41, Feb. 2009.

NIEDERHAGEN, B. et al. Location and sanitation of dental foci in liver

transplantation. Transpl. Int., v. 16, n. 3, p. 173-178, Mar. 2003.

NOVACEK, G. et al. Dental and periodontal disease in patients with cirrhosis: role of

O’LEARY, J. G.; YACHIMSKI, O. S.; FRIEDMAN, L. S. Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Clin. Liver Dis., v. 13, n. 2, p. 211-231, May 2009.

PATATANIAN, E.; FUGATE, S. E. Hemostatic mouthwashes in anticoagulated patients undergoing dental extraction. Ann. Pharmacother., v. 40, n. 12, p. 2205-2210, Dec. 2006.

QUAKNINE-ORLANDO, B. et al. Role of the hematocrit in a rabbit model of arterial

thrombosis and bleeding. Anesthesiology, v. 90, n. 5, p. 1454-1461, May 1999. RAKOCZ, M. et al. Dental extractions in patients with bleeding disorders: the use of

fibrin glue. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol., v. 75, n. 3, p. 280-282, Mar. 1993. RAMLI, R.; RAHMAN, R. A. Minor oral surgery in anticoagulated patients: local measures alone are sufficient for haemostasis. Singapore Dent. J., v. 27, n. 1, p. 13-16, Dec. 2005.

REGISTRO BRASILEIRO DE TRANSPLANTES. São Paulo. Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgãos; Ano XVI, n. 4, Jan/Dez. 2010. Disponível em:

http://www.abto.org.br/abtov02/portugues/populacao/rbt/anoXV_n4/index.aspx?idCat egoria=2 Acesso em: 6 mar. 2011.

REICH, W. et al. Bleeding complications after oral surgery in outpatients with

compromised haemostasis: incidence and management. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., v. 13, n. 2, p. 73-77, June 2009.

ROBB, N. D.; SMITH, B. G. Chronic alcoholism: an important condition in the dentist-patient relationship. J. Dent., v. 24, n. 1-2, p. 17-24, Jan./Mar. 1996.

RODRÍGUEZ-CABRERA, M. A. et al. Extractions without eliminating anticoagulant

treatment: a literature review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal, Jan. 2011. [Epud ahead of print]

ROSE, L. F.; KAY, D. Internal medicine for dentistry. 2.ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1983. p. 425-426.

RUSTEMEYER, J.; BREMERICH, A. Necessity of surgical dental foci treatment prior to organ transplantation and heart valve replacement. Clin. Oral Investig., v. 11, n. 2, p. 171-174, June 2007.

SAMUEL, P. R.; ROBERTS, A. C.; NIGAM, A. The use of indermil (n-butyl cyanoacrylate) in otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery: a preliminary report on the first 33 patients. J. Laryngol. Otol., v.111, n. 6, p. 536-540, June 1997. SHEEHY, E. C. et al. Dental management of children undergoing liver

TENZA, E. et al. Liver transplantation complications in the intensive care unit and at

6 months. Transplant. Proc., v. 41, n. 3, p. 1050-1053, Apr. 2009.

THOMSON, P. J.; LANGTON, S. G. Persistent haemorrhage following dental

extractions in patients with liver disease: two cautionary tales. Br. Dent. J., v. 180, n. 4, p. 141-144, Feb. 1996.

TRIPODI, A. et al. Review article: the prothrombin time test as a measure of bleeding

risk and prognosis in liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther., v. 26, n. 2, p. 141-148, July 2007.

TRIPODI, A. Tests of coagulation in liver disease. Clin. Liver Dis., v. 13, n. 1, p. 55-61, Feb. 2009.

VALERI, C. R.; KHURI, S.; RAGNO, G. Nonsurgical bleeding diathesis in anemic thrombocytopenic patients: role of temperature, red blood cells, platelets, and plasma-clotting proteins. Transfusion., v. 47, n. 4 Suppl, p. 206S-248S, Oct. 2007. WAHL, M. J. Myths of dental surgery in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy. J. Am. Dent. Assoc., v. 131, n. 1, p. 77-81, Jan. 2000.

WARD, B. B.; WEIDEMAN, E. M. Long-term postoperative bleeding after

dentoalveolar surgery in the pretransplant liver failure patient. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., v. 64, n. 10, p. 1469-1474, Oct. 2006.

WYKE, R. J. Problems of bacterial infection in patients with liver disease. Gut, v. 28, n. 5, p. 623-641, May 1987.

ZANON, E. et al. Proposal of a standard approach to dental extraction in haemophilia

patients: a case-control study with good results. Haemophilia, v. 6, n. 5, p. 533-536, Sep. 2000.

ZANON, E. et al. Safety of dental extraction among consecutive patients on oral

anticoagulant treatment managed using a specific dental management protocol. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis, v. 14, n. 1, p. 27-30, Jan. 2003.

ZICCARDI, V. B. et al. Maxillofacial considerations in orthotopic liver transplantation.