www.bjorl.org

Brazilian

Journal

of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Encoding

of

speech

sounds

at

auditory

brainstem

level

in

good

and

poor

hearing

aid

performers

夽

Hemanth

Narayan

Shetty

∗,

Manjula

Puttabasappa

AllIndiaInstituteofSpeechandHearing,DepartmentofAudiology,Mysuru,Karnataka,India

Received5February2016;accepted20June2016 Availableonline14July2016

KEYWORDS

Frequencyfollowing response;

Acceptablenoise level;

Hearingaid performer

Abstract

Introduction:Hearingaidsareprescribedtoalleviatelossofaudibility.Ithasbeenreported thatabout31%ofhearingaidusersrejecttheirownhearingaidbecauseofannoyancetowards backgroundnoise.Thereasonfordissatisfactioncanbelocatedanywherefromthehearingaid microphonetilltheintegrityofneuronsalongtheauditorypathway.

Objectives:To measure spectra from theoutput ofhearing aid at theear canal leveland frequencyfollowingresponserecordedattheauditorybrainstemfromindividualswithhearing impairment.

Methods:Atotalofsixtyparticipantshavingmoderatesensorineuralhearingimpairmentwith agerangefrom15to65yearswereinvolved.EachparticipantwasclassifiedaseitherGoodor PoorHearingaidPerformersbasedonacceptablenoiselevelmeasure.Stimuli/da/and/si/ werepresentedthroughloudspeakerat65dBSPL.Attheearcanal,thespectraweremeasured intheunaidedandaidedconditions.Atauditorybrainstem,frequencyfollowingresponsewere recordedtothesamestimulifromtheparticipants.

Results:Spectrummeasuredineachconditionatearcanalwassameingoodhearingaid per-formersandpoorhearing aidperformers.Atbrainstemlevel,betterF0encoding;F0andF1

energiesweresignificantlyhigheringoodhearingaidperformersthaninpoorhearingaid per-formers.Thoughthehearingaidspectrawerealmostsamebetweengoodhearingaidperformers andpoorhearingaidperformers,subtlephysiologicalvariationsexistattheauditorybrainstem. Conclusion:Theresultofthepresentstudysuggeststhatneuralencodingofspeechsoundat thebrainstemlevelmightbemediateddistinctlyingoodhearingaidperformersfromthatof poorhearing aid performers.Thus,itcanbe inferredthatsubtlephysiological changesare evidentattheauditorybrainsteminapersonwhoiswillingtoacceptnoisefromthosewhoare notwillingtoacceptnoise.

© 2016 Associac¸˜ao Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia C´ervico-Facial. Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:ShettyHN,PuttabasappaM.Encodingofspeechsoundsatauditorybrainstemlevelingoodandpoorhearing aidperformers.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2017;83:512---22.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:hemanthn.shetty@gmail.com(H.N.Shetty).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofAssociac¸ãoBrasileiradeOtorrinolaringologiaeCirurgiaCérvico-Facial.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.06.004

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Frequênciaseguida deresposta; Nívelderuído aceitável;

Usuáriodeaparelho auditivo

Codificac¸ãodossonsdafalanoníveldotroncoencefálicoauditivoembonsemaus usuáriosdeaparelhosauditivos

Resumo

Introduc¸ão: Osaparelhosauditivos sãoprescritospara aliviar aperdade audibilidade.Tem sidorelatadoquecercade31%dosusuáriosrejeitamseupróprioaparelhoauditivodevidoao desconfortocomoruídodefundo.Arazãoparaainsatisfac¸ãopodeestarsituadaemqualquer localdesdeomicrofonedoaparelhoauditivoatéaintegridadedeneurôniosaolongodavia auditiva.

Objetivos: Medirespectrosdesdeasaídadoaparelhoauditivononíveldocanalauditivoexterno efrequênciaderesposta(FFR)registradanotroncoencefálicodeindivíduoscomdeficiência auditiva.

Método: Umtotaldesessentaparticipantescomdeficiênciaauditivaneurossensorial moder-ada, comfaixa etáriade 15 a65 anosforam envolvidos. Cadaparticipante foi classificado comousuáriobomoumaudepróteseauditiva(GHPouPHP)combasenamedidadenívelde ruídoaceitável(ANL).Estímulos/da/e/si/foramapresentadosemalto-falantea65dBSPL. Nomeato acústicoexterno,osespectros forammedidosnascondic¸ões semaparelhoecom aparelho.Notroncoencefálicoauditivo,FFRforamregistradasparaosmesmosestímulosdos participantes.

Resultados: Osespectros medidosemcadacondic¸ãonocanalauditivoforamosmesmosem GHP ePHP.Nonível do troncocerebral,melhor codificac¸ãoF0; energiasde F0 eF1 foram significativamente maioresemGHP doqueem PHP.Emboraosespectros doaparelho audi-tivofossemquaseosmesmosentreGHPePHP,existemvariac¸õesfisiológicassutisnotronco encefálicoauditivo.

Conclusão:Oresultadodopresenteestudosugerequeacodificac¸ãoneuraldosomdafalano níveldotroncoencefálicopodesermediadadistintamenteemGHPemcomparac¸ãocomPHP. Assim,pode-seinferirquemudanc¸asfisiológicassutissãoevidentesnotroncoencefálicoem uma pessoaque estádispostaaaceitaroruídoem comparac¸ãocomaquelesquenão estão dispostosaaceitaroruído.

© 2016 Associac¸˜ao Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia C´ervico-Facial. Publicado por Elsevier Editora Ltda. Este ´e um artigo Open Access sob uma licenc¸a CC BY (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Hearing aidis oneofthecommonrehabilitativemeasures

forindividualswithpermanenthearingimpairment.Insome

casesofhearinglosses,hearingaidscanbeusedtransitory.

However,hearing aid users often complainof background

noise resulting in rejection of hearing AID.1 Kochkin2 has

reportedthatabout31%ofthehearingaidusersrejecttheir

hearingaidbecauseofbackground noise.Variousoutcome

measures areavailable that considerbackground noise as

oneofthefactorstohaveaneffectonsatisfactionwiththe

hearingaid.Unfortunately,theseoutcomemeasuresareto

beadministeredafteraperiodofexperiencewithhearing

aid. Besides measures suchas speechin noise test, quick

speechinnoisetest, competingnoisetest,andhearingin

noisetestarebeingusedtopredictthehearingaidbenefit.3

Thoughthesetestsaresensitivetomeasurespeech

perfor-manceinnoiseandareadministeredatthetimeoffitting

hearingaid; theyfailtopredict real-worldbenefitand/or

satisfactionfromhearingAids.4Thisissueisaddressedpartly

by acceptable noise level (ANL) measure introduced by

Nabeleket al.,5 in which the client rates annoyance due

tobackgroundnoiseinthepresenceofspeech.

Nabeleketal.6demonstratedthatvalueofANLspredict

goodand poor hearingaid performerswith85% accuracy.

TheANLis notaffectedbythetypeofbackgroundnoise,5

preferenceofbackgroundsounds,7primarylanguageofthe

listener,8 speechpresentation levels,7 age, hearing

sensi-tivityand language9 contentof speechsignal andspeaker

gender.10Harkrider,11 studiedthephysiologicalcorrelateof

ANL involved at higher auditory centresutilizing

electro-physiological measurement. In individuals with low ANLs

(i.e.,greaterbackgroundnoiseacceptance),amplitudesof

waveV of auditory brainstem response (ABR), all

compo-nentsof middle latency response (MLR), andlate latency

response (LLR) were noted to be significantly prolonged

when compared to individuals who obtained high ANLs

(lowerbackgroundnoiseacceptance).Thisisduetostronger

efferent mechanism, such that sensory inputs are

sup-pressedand/orcentralafferentmechanismislessactive.12

Thus,ANLproved tobephysiologically sensitivemeasure.

However,itisinterestingtoknowthewayinwhich

ampli-fiedspeechisrepresentedphysiologicallyingoodandpoor

hearingaidperformers.

Despite advancement in hearing aid technology, some

individualsaccepthearingaidandothersmayrejectinspite

of fact that they have a similar hearing loss in terms of

degree,type,andconfiguration.Thevariabilityin

satisfac-tionfromrehabilitativedevicemightprobablybeduetothe

processingparametersofhearingaid,and/oratinteraction

betweenoutputofhearingaidanditsacousticparameters

presentstudy,outputof hearingaid isinvestigatedat ear

canalandatauditorybrainstem.

Over the decades, researchers have used probe tube

microphone(PTM)systemtomeasuretheeffectofhearing

aid processingon acousticsof speech. The PTM

measure-ment reflects the acoustic effect of the factors such as

pinna, ear canal, head and torso.14 Primarily, the PTM is

usedtooptimize/verifythehearingaidgaintomatchwith

thetargetgainatdifferentfrequenciesasprescribedbythe

fittingformula.15 Itiswellestablishedthatoutputof

hear-ingaid at theearcanal willalter amplitudes offormants

leadingtomisperception.Anexperimentwasconductedby

Stelmachowiczetal.16 whorecordedoutputofthehearing

aidattheearcanalusinglinearandnon-linearhearingaids

onthreelistenerswithmild-moderatesensorineuralhearing

loss.They carriedoutspectralanalysisontheserecorded

stimuli. The results revealed a precipitous roll-off in the

high frequency response, thus limiting the informationof

a consonant cues. On similar line, Souza and Tremblay17

conductedastudytocorrelateconsonanterrorsto

acous-tic analysis of amplified speech in subjects with mild to

moderate sensorineural hearing loss. They observed that

/da/stimuluswasconsistentlymisperceivedas/ga/.This

wasattributed to the amplitude of aided burst spectrum

of/da/whichwasfoundtobesimilartotheunprocessed

burstspectrumamplitudeof/ga/.Kewley-Port18 reported

that identification of stop consonants in the initial

posi-tion requires the spectrum of burst as the primary cue

for speechrecognition. Thus,after amplificationthe stop

consonants are more likely to have place error.17

How-ever,amplifiedconsonant-vowelcombinationoffricativeor

affricativetendstoshowmannererrors,asconsistent

mis-perception of /i/ for /di/ speech sounds19 was noted.

When theacousticoutput of hearingaid wasanalyzed, it

wasrevealedthatamplitudespectrumoffricative/i/was

similartotheunprocessed affricativespectrumamplitude

of /di/.Hence, performingspectral analysisof the

out-putof hearing aid recorded at the earcanal throwslight

on the processing parameters of hearing aid. There are

instancesinwhichacousticcuesaredistortedbutalistener

stillrecognizescorrectly.Thiscouldbeduetoredundancyor

fromthecontextualcuesofspeech.Insomeotherinstances

acousticcuesarepreservedbutalistenerfailstorecognize

speechsound.Thismaypossiblybebecauseofinsufficient

sensitivityincochleaand/orconcomitantchangesat

differ-entlevelsofauditorypathway.Hence,anevokedpotential

recordedtospeechstimulishouldbeusedtovalidate

per-ceptionregisteredatdifferentlevelsofauditorypathway.

Inthepresentstudy,evokedresponseatthelevelof

audi-torybrainstemofgoodandpoorhearingaidperformersis

investigated.

Thefrequencyfollowingresponses(FFR)hasbeen

exten-sively studied to understand the physiological processing

of speech at the auditory brainstem level. The FFR is a

phase-lockedresponsetoperiodicaspectsofstimuli,

includ-ingspeech, up to1000Hz20,21 from the neural population

of inferior colliculus of rostral brainstem.22 The FFR has

beenreliablyrecordedtoconsonant-vowelsounds/da/.23---26

Further, FFR to /da/ stimulus has been investigated in

monaural27 and binaural28 conditions; in the presence of

backgroundnoise;27 andstimulationof eitherright or left

ear.29 TheFFRwassuccessfullyrecordedusingloudspeaker

asatransducertodeliverthestimuli/da/and/si/.30From

this,it isclear thatFFRis astimuluscontingent response

thatismostrobustformid-andlow-frequencies.Thoughthe

frequencyresponseofhearingaidisupto6500Hz,theFFR

isasensitivetooltoanychangeinprocessingintheauditory

brainstem,suchthatitanswersthequestiononhow

ampli-fiedspeechsoundsareencodedinmid-andlow-frequencies

fromgoodandpoorhearingaidperformers.

Fromtheexistingliterature,itcanbeinferredthat

spec-tralanalysesofhearingaidoutputobtainedusingthePTM

giveinformationonhearingaidprocessingattheearcanal

level.Further,stimulusfromtheearcanalisrelayedtothe

auditory brainstem level and is measured using FFR. The

FFRwillhelpininferringtheneuralencodingoftheongoing

speech.Thesemeasuresgiveinsightintothewayinwhich

the speechis neurallyencoded at thebrainstem level, in

individualswithsensorineuralhearingimpairmentwhoare

classified asgoodand poorhearing aid performershaving

comparabletype,degreeandconfigurationofhearingloss.

Therefore,thepresentstudyintendstoinvestigatehearing

aid output at theearcanal todetermine extent of

alter-ationcausedbythehearingaidonthespectralparameters.

Inaddition,wayinwhichamplifiedspeechisrepresentedat

thebrainstemlevelingoodandpoorhearingaidperformers

alsoisbeinginvestigated.Theobjectivesformulatedforthe

studyweretocompare:(1)spectralchangesbetweenGHP

andPHPin unaidedandaided conditionsat theearcanal

usingthePTM;and(2)neuralencodingofspeechsoundsat

auditorybrainstemlevelinGHPandPHP.

Methods

Participants

A total of 60 participants who had bilateral moderate

sensorineural hearing loss with a flat configuration were

involved inthestudy.Flat configurationwasoperationally

defined as the difference between least and highest

air-conductionthresholdsbeinglessthan20dBintherangefrom

0.25to8kHz.31Theagerangeoftheparticipantswasfrom

15to65years.Theyhadspeechidentificationscores(SIS)

thatwasgreaterthanorequalto75%at40dBSL(re:speech

receptionthreshold,SRT).Thetestearhadnormalmiddle

earstatusasindicatedby‘A’typetympanogramwithmiddle

earpeakpressurerangingfrom+50daPato−100daPa,and

admittance ranging from0.5mL to1.75mL. The auditory

brainstem response (ABR) wasrecorded at two repetition

ratesof11.1sand90.1sat90dBnHLtoensurethatthere

wasnoretrocochlearpathology.Thelatencydifferenceof

V peakof ABR wasfound tobeless than 0.8ms between

thetworepetitionrates. Allparticipantswerenaïve

hear-ingaidusersandtherewasnoself-reportedhistoryofother

otologicalandneurologicalproblems.Theparticipantswere

further classified into Good or Poor Hearing aid

Perform-ers(GHP or PHP)usingtheacceptable noise level(ANL).6

ThoseparticipantswhoobtainedanANL scoreof≤7were

considered asgoodhearingaid performersand ascore of

≥13wereconsideredaspoorhearingaidperformers.6The

demographicdataofeach participantinclinicalgroupare

tabulatedinTable1.Thehearingthresholdsateach

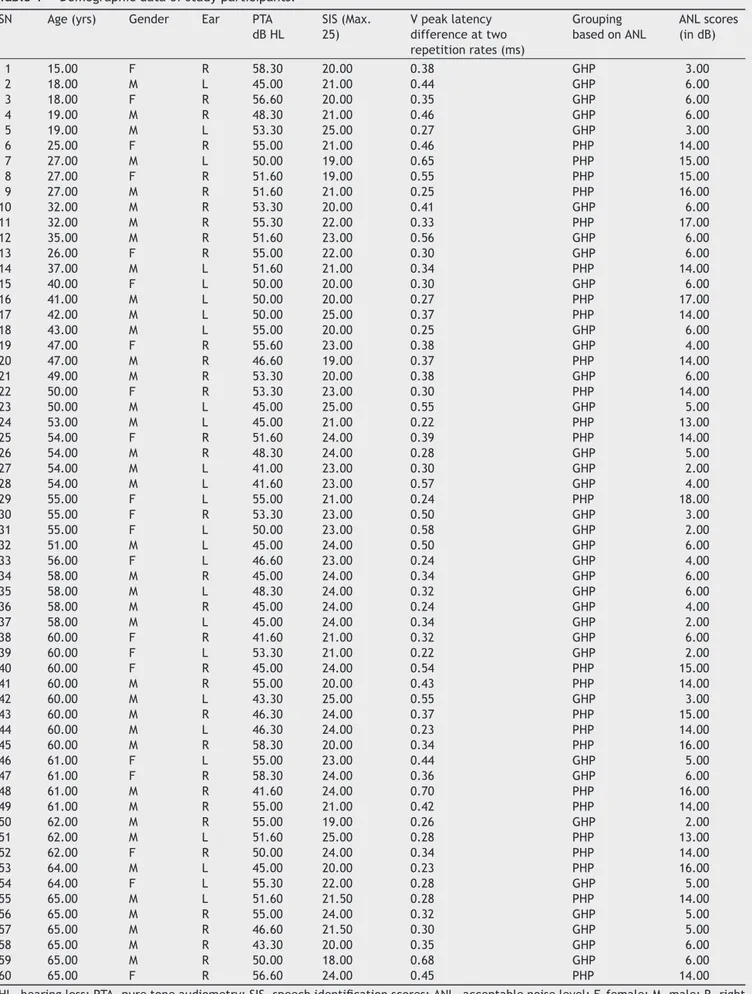

Table1 Demographicdataofstudyparticipants.

SN Age(yrs) Gender Ear PTA dBHL

SIS(Max. 25)

Vpeaklatency differenceattwo repetitionrates(ms)

Grouping basedonANL

ANLscores (indB)

1 15.00 F R 58.30 20.00 0.38 GHP 3.00

2 18.00 M L 45.00 21.00 0.44 GHP 6.00

3 18.00 F R 56.60 20.00 0.35 GHP 6.00

4 19.00 M R 48.30 21.00 0.46 GHP 6.00

5 19.00 M L 53.30 25.00 0.27 GHP 3.00

6 25.00 F R 55.00 21.00 0.46 PHP 14.00

7 27.00 M L 50.00 19.00 0.65 PHP 15.00

8 27.00 F R 51.60 19.00 0.55 PHP 15.00

9 27.00 M R 51.60 21.00 0.25 PHP 16.00

10 32.00 M R 53.30 20.00 0.41 GHP 6.00

11 32.00 M R 55.30 22.00 0.33 PHP 17.00

12 35.00 M R 51.60 23.00 0.56 GHP 6.00

13 26.00 F R 55.00 22.00 0.30 GHP 6.00

14 37.00 M L 51.60 21.00 0.34 PHP 14.00

15 40.00 F L 50.00 20.00 0.30 GHP 6.00

16 41.00 M L 50.00 20.00 0.27 PHP 17.00

17 42.00 M L 50.00 25.00 0.37 PHP 14.00

18 43.00 M L 55.00 20.00 0.25 GHP 6.00

19 47.00 F R 55.60 23.00 0.38 GHP 4.00

20 47.00 M R 46.60 19.00 0.37 PHP 14.00

21 49.00 M R 53.30 20.00 0.38 GHP 6.00

22 50.00 F R 53.30 23.00 0.30 PHP 14.00

23 50.00 M L 45.00 25.00 0.55 GHP 5.00

24 53.00 M L 45.00 21.00 0.22 PHP 13.00

25 54.00 F R 51.60 24.00 0.39 PHP 14.00

26 54.00 M R 48.30 24.00 0.28 GHP 5.00

27 54.00 M L 41.00 23.00 0.30 GHP 2.00

28 54.00 M L 41.60 23.00 0.57 GHP 4.00

29 55.00 F L 55.00 21.00 0.24 PHP 18.00

30 55.00 F R 53.30 23.00 0.50 GHP 3.00

31 55.00 F L 50.00 23.00 0.58 GHP 2.00

32 51.00 M L 45.00 24.00 0.50 GHP 6.00

33 56.00 F L 46.60 23.00 0.24 GHP 4.00

34 58.00 M R 45.00 24.00 0.34 GHP 6.00

35 58.00 M L 48.30 24.00 0.32 GHP 6.00

36 58.00 M R 45.00 24.00 0.24 GHP 4.00

37 58.00 M L 45.00 24.00 0.34 GHP 2.00

38 60.00 F R 41.60 21.00 0.32 GHP 6.00

39 60.00 F L 53.30 21.00 0.22 GHP 2.00

40 60.00 F R 45.00 24.00 0.54 PHP 15.00

41 60.00 M R 55.00 20.00 0.43 PHP 14.00

42 60.00 M L 43.30 25.00 0.55 GHP 3.00

43 60.00 M R 46.30 24.00 0.37 PHP 15.00

44 60.00 M L 46.30 24.00 0.23 PHP 14.00

45 60.00 M R 58.30 20.00 0.34 PHP 16.00

46 61.00 F L 55.00 23.00 0.44 GHP 5.00

47 61.00 F R 58.30 24.00 0.36 GHP 6.00

48 61.00 M R 41.60 24.00 0.70 PHP 16.00

49 61.00 M R 55.00 21.00 0.42 PHP 14.00

50 62.00 M R 55.00 19.00 0.26 GHP 2.00

51 62.00 M L 51.60 25.00 0.28 PHP 13.00

52 62.00 F R 50.00 24.00 0.34 PHP 14.00

53 64.00 M L 45.00 20.00 0.23 PHP 16.00

54 64.00 F L 55.30 22.00 0.28 GHP 5.00

55 65.00 M L 51.60 21.50 0.28 PHP 14.00

56 65.00 M R 55.00 24.00 0.32 GHP 5.00

57 65.00 M R 46.60 21.50 0.30 GHP 5.00

58 65.00 M R 43.30 20.00 0.35 GHP 6.00

59 65.00 M R 50.00 18.00 0.68 GHP 6.00

60 65.00 F R 56.60 24.00 0.45 PHP 14.00

GHP

0

20

40

60

Threshold (dB HL)

80

100

0.25 0.50 1

Frequency (kHz)

2 4 8

PHP

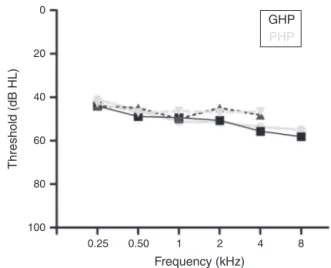

Figure1 Audiogramsofgoodandpoorhearingaid perform-ers.

hearingaidperformersaredepictedinFig.1.Thestudywas

approvedby theAllIndia Institute ofSpeech andHearing

EthicsCommitteeforResearchinHumans.Informedconsent

wasobtainedfromeachparticipant.

Stimuli

Naturallyproducedconsonantvowel(CV)tokenswere

uti-lizedastargetteststimuli.Anadultmalewithnormalvoice

wasused to record the CV tokens. The duration of /da/

and /si/ stimuli was 94ms and 301ms, respectively. For

/da/,thevoiceonsettimewas18ms,burstduration was

5ms,transitiondurationwas37ms,andvoweldurationwas

34ms.For/si/, thefricativedurationwas159.3ms,

tran-sition duration was 47.1ms and the vowel duration was

94.6ms. Both the stimuli were converted from ‘.wav’ to

‘.avg’formatusingwavtoavgm-fileofBrainstemtoolbox.

The‘.avg’formatofboththestimuliwerebandpassfiltered

from30to3000HzusingNeuroscan(Scan2-version4.4)to

knowthefunctionalrelationshipbetweentheacoustic

struc-tureofspeechandthebrainstemresponsetospeech.The

‘stimulus.avg’,waveformsandspectrogramsofthetwoCV

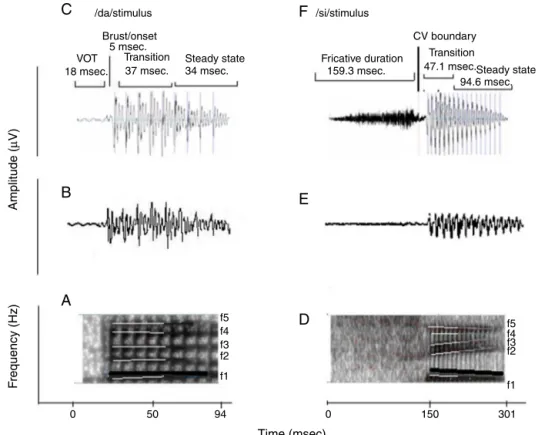

tokensaredepictedinFig.2.Table2summarizesthe

funda-mentalfrequency(F0)andthefirsttwoformantfrequencies

(F1andF2)ofthevowelcomponentof/da/and/si/stimuli.

TheonsettosteadystateF0,F1andF2withinthetransition

duration (37ms)of /da/stimulus, and frequency

compo-nentswithinthetransitionduration (42ms)of/i/ portion

of/si/stimulusweremeasuredusingPraat(version5.1.29)

software.

Further, Kannada passage developed by Sairam and

Manjula32 wasreadoutinnormalvocaleffortbyafemale

speakerwasrecordedusingAdobeAudition(version3)

soft-ware. This recorded passage was used to determine the

acceptablenoiselevel(ANL).Agoodnesstestwasperformed

inordertoverifythequalityoftherecordedKannada

pas-sage,inwhichtenlisteners withnormalhearingratedthe

passagefornaturalness.

Hearingaid

DigitalBehindTheEar(BTE)hearingaidwasusedtorecord

theoutputat theearcanalandattheauditory brainstem

responsefromeachparticipant.Accordingtothetechnical

specifications,frequencyrangeoftesthearingaidextended

from0.210to6.5kHz.Thepeakfull-ongainwas58dBand

high-frequency average full-on gain was49dB. The

func-tioningofthehearingaid wasensuredatthebeginningof

the data collectionandrepeated periodicallyduring data

collection.

Procedure

Eachparticipantwasclassifiedintogoodandpoorhearing

aidperformerusingthebehaviouralANLtest.Thetest

hear-ingaidwithcustomearmouldwasfittedtoeachparticipant

anditsgainwasoptimized.Tooptimizethehearingaidgain,

sixLing’ssyllables werepresented atacalibratedlevel of

65dBSPLthroughtheaudiometerinasoundfield.Thegain

andthefrequencyresponseofthehearingaidwere

manipu-latedfortheaudibilityofeachofsixLing’ssyllables,through

fine tuning option. To know the extent to which spectral

featurearepreservedbythehearingaid,theoutputofthe

hearingaidtoeachstimuluswasrecordedattheearcanal

usingtheprobetubemicrophonemeasure.Further,theFFR

at the brainstem level wasrecorded to each stimulus, in

bothunaidedandaidedconditions.

Acceptablenoiselevel

Acceptablenoiselevel(ANL)evaluatesthereactionofthe

listener to background noise while listening to speech.

For the measurement of ANL, the method given by

Nabelek et al.5 was adopted. Each study participant was

Table2 Fundamentalfrequencyandthetwoformantfrequencies(inHz)atthetransitiondurationoforiginalandfiltered versionof/a/and/si/stimuli.

Stimuli F0(Hz) F1(Hz) F2(Hz)

Onset Steadystate Onset Steadystate Onset Steadystate

Originalversion /a/ 135.7 131.2 519.8 556.3 1822.4 1677.7

/si/ 145.7 137.5 345.4 308.8 2268.5 2451.5

Filteredversion /a/ 135.7 131.2 519.8 556.3

/si/ 145.7 137.5 345.4 308.8

F0,fundamentalfrequency;F1andF2,firstandsecondformantfrequencies;F2,forfilteredversionisnotapplicablesincetheupper

/da/stimulus

Amplitude (

µ

V)

F

requency (Hz)

/si/stimulus

Brust/onset CV boundary

5 msec.

18 msec.

C

F

B

E

A

D

37 msec. 34 msec.

f5

f5

f4 f4

0 50 94 0 150 301

Time (msec)

f3 f3

f2 f2

f1

f1 159.3 msec.

94.6 msec. 47.1 msec.

Transition Steady state Transition

Steady state Fricative duration

VOT

Figure2 (A)and(D)arethespectrogramsof/da/and/si/stimuli.ThedarkblacksolidlineinbothstimuliindicatestheF0,

whichhasafallingpattern.Theformantfrequenciesarerepresentedbywhitelines.TheF1andF2of/da/isflatinpattern.TheF1

of/si/stimulusisfallinginpatternandF2israisinginpattern.(C)and(F)arethewaveformsof/da/and/si/stimuli.Forsound

/da/,thevoiceonsettimewas18ms,theburstdurationwas5ms,thetransitiondurationwas37msandvoweldurationof34ms. Forthesound/si/,thefricativedurationwas159.3ms,transitiondurationwas47.1msandvoweldurationwas94.6ms.

made to sit comfortably on a chair in front of the loudspeaker of the audiometer that was located at 1m distanceand45◦ Azimuth.TocomputetheANL,most

com-fort level (MCL) and background noise level (BNL) were measured.

The recordedKannada passagewasroutedthroughthe auxiliaryinput totheloudspeakerof theaudiometer. The presentationlevelsetatthelevelofSRT.Gradually,thelevel wasadjustedin5dB-stepstoestablishthemostcomfortable level(MCL)andtheninsmallerstepssizeof+1and−2dB, untilthe MCL wasestablishedreliably.After theMCL was established,speechnoisewasintroducedat 30dBHL.The levelofthespeechnoisewasincreasedin5dB-stepsinitially, andthenin2dB-steps,toapointatwhichtheparticipant waswillingtoacceptthenoisewithout becomingtiredor fatiguedwhile listening toandfollowing thewords in the story.Themaximumlevelatwhichhe/shecouldacceptor putup withthespeechnoise withoutbecoming tiredwas consideredasthebackgroundnoiselevel(BNL).Thelevelof thespeechnoisewasadjusteduntilparticipantwasableto ‘put-up-with’thenoisewhilefollowingthestory.The resul-tantlevelwastheBNL.The ANLquantifiestheacceptable level of background noise andis calculated asthe differ-ence between MCL (dB HL) and BNL (dB HL).4 Based on

the ANLs,each participantwasclassified asgood (ANLof

≤7dB) or poor (ANL of ≥13dB) hearing aid performers.4

The procedure of ANL was repeated twice and the

average of thetwo valueswasconsidered asthe ANL for

eachparticipant.

Hearingaidgainoptimization

EachparticipantwasfittedwiththedigitalBTEtest

hear-ingaidusingacustommadesoftshellmould.Thehearing

aid was programmed using NAL-NL1prescriptive formula.

The real ear measurement was carried out tomatch the

gainofhearingaidwiththetargetgainobjectively.Further,

theLing’ssixspeechsoundswerepresentedat65dBSPLto

optimizethehearingaidgain.Throughfine tuningoption,

thegainandthefrequencyshapingofthehearingaidwere

optimizedfortheaudibilityofLing’ssixsounds.

Hearingaidprocessedspeechatearcanal

Theleveloftheeachsignal (storedinpersonalcomputer)

wasvariedintheaudiometersothattheintensitymeasured

was65dBSPLinsoundlevelmeter.LarsonDavis824sound

levelmeter(SLM)waspositionedatthetestearofthe

par-ticipant.TheSLMwassetatfastweightingfunction,andit

wasensuredthatthestimuli/da/and/si/werepresented

at65dBSPL,basedonpeakamplitudelevelreadontheSLM.

Afterthecalibrationofstimuluswasensured,output

microphonemeasurement,inbothunaidedandaided

con-ditions.Theprobetube microphoneintheearcanalpicks

upthespectralenergiesatapproximatelyhalf-octavebands

from0.25kHzto8kHzforeachspeechstimulus.Thelevels

asafunctionoffrequencyfrom0.25kHzto8kHz,inoctaves,

werenoteddownforeachstimulus,intheunaidedandaided

conditions.

Acquisitionofthefrequencyfollowingresponse

Each participant was seated comfortably in a reclining

chairwitharm.The electrodesites werecleaned upwith

skinpreparinggel.Disctypesilvercoatedelectrodeswere

placed using conduction gel at the test sites. The FFR

was recorded using vertical montage. The non-inverting

electrode (+) was placed onthe vertex (Cz), the ground

electrodewasonupperforehead (Fpz)andthe inverting

electrode(−)wasplacedonnose.Itwasensuredthatthe

electrodeimpedancewaslessthan5kforeachofthe

elec-trodesandthattheinter-electrodeimpedancewaslessthan

2k.

Prior to recording, calibration of stimuli was ensured

usingLarsonDavisSystem824SLM.TheSLMwaspositioned

atreferencepoint.Itisthepointwherethetestearofthe

participantwouldbepositionedatthetimeoftesting.The

SLMwassetatfastweightingfunctionforthemeasurement.

Itwas ensuredthat both stimuli/da/ and /si/ were

pre-sentedat65dBSPL,basedonpeakamplitudelevelreadon

theSLM.

TheloudspeakeroftheAuditoryEvokedPotential

equip-mentwasplacedat 45◦ Azimuthfromtheparticipanttest

ear,locatedat thecalibratedpositionof12inchdistance.

Theheightofloudspeakerwasadjustedtothelevelof

par-ticipanttestear. Theparticipantwasinstructed toignore

the stimulus and to watch a movie that was muted and

playedthroughabatteryoperatedlaptopcomputer.He/she

wasalsoaskedtominimizetheeyeandheadmovement.

ForrecordingtheunaidedandtheaidedFFR,thestimulus

/da/waspresentedthroughloudspeakeratthe

presenta-tionlevelof65dBSPLtothetestear.ThePC-basedevoked

potentialsystem, Neuroscan4.4(Stim2-version4.4),

con-trolledthe timing of stimulus presentation and delivered

anexternal trigger tothe evokedpotentialrecording

sys-tem,Neuroscan(Scan2-version4.4).Toallowforasufficient

refractory period within the stimulus sweep, while

mini-mizingthetotalrecordingtime,an inter-stimulusinterval

(ISI)of93ms.fromoffsettoonsetofthenextstimuluswas

includedforrecordingFFRto/da/stimulus.Asimilar

pro-cedurewasrepeatedtorecordtheunaidedandaidedFFR

for/si/stimulus.However,forrecordingunaidedandaided

FFRto/si/ stimulus,an ISIof113mswasused.The order

of stimuli while testing on each participant was counter

balanced. The FFR was recorded from 1500 sweeps each

in condensationand rarefaction polarities,delivered in a

homogenoustrainusingthestimuluspresentationsoftware

Neuroscan4.4(Stim2-version4.4).

The FFR recording was initiated once a stable

elec-troencephalogram (EEG) was obtained. The ongoing EEG

was converted from analogue-to-digital with the rate

of 20,000Hz. The continuous EEG was online band-pass

CV boundary

Transition

1

0

–1

–30 6 42 78 114 150 Latency (msec)

186 222 258 294 330

Stimulus

Response Auto corelation (F0)

Brainstem tool box (F0 and F1 energies)

Amplitude (

µ

V)

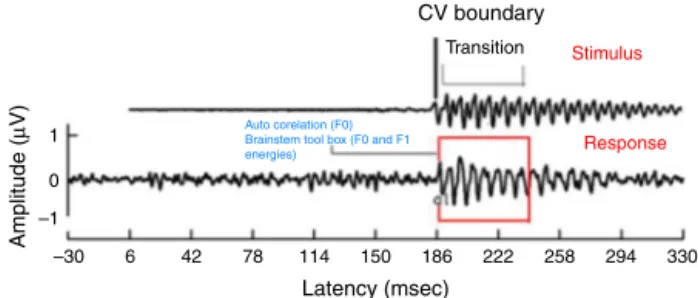

Figure3 TransitionresponseofFFRobtainedfrom/si/

stim-ulusinaidedcondition.

filteredfrom30to3000Hzwith12dB/octaveroll-off.This

wasstoredtodiscforofflineanalysis.

Dataanalyses

Theoutputofthehearingaidintheearcanalforeach

stim-ulusintheunaidedandaidedconditionswereanalyzedfor

spectra.Further,theFFRrecordedwasanalyzedforF0,F0

energyandF1energyobtainedforeachstimulus.The

con-tinuous EEGdata wereepoched over a window of 160ms

for /da/ stimulus (which included a 30ms pre-stimulus

periodanda130mspost-stimulustime).Theresponsefor

/si/stimuluswasepochedoverawindowof360ms(which

includedapre-stimulusperiodof30msandapost-stimulus

periodof330ms).Theepochedwaveformswerecorrected

for baseline. The responses were averaged and filtered

off-line from 0.030kHz (high-pass filter, 12dB/octave) to

3kHz(low-passfilter,12dB/octave).Allartefactsexceeding

±35Vwererejectedwhileaveragingtheresponseforeach

averagedresponse,inrarefactionandcondensation

polar-ity.Aminimumof1450 artefact-freeepochs wasensured.

The averagedwaveforms of rarefaction and condensation

polaritieswereadded.Further,theaddedwaveformswere

createdbyaveragingtwotrialsrecordedforeachstimulus,

inunaidedandaidedconditions.

For all the participants, the unaided responses were

absent for both the stimuli. FromFFR recorded for /da/

stimulus in aided condition, the latency of ‘V’ peak was

identifiedbyvisualinspection.ThedefaultMATLAB-codeof

autocorrelation wasutilized, inwhich arange forlatency

wasspecified toobtainF0 in theFFR i.e.,fromnoted‘V’

peaklatencytilltransitionduration.Whereas,thelatency

of‘a1’correspondingtoCVboundary30intheFFRwas

iden-tified for /si/ stimulus is shown in Fig.3. The latency of

‘a1’tilltransitiondurationwasspecifiedinautocorrelation

MATLAB codeto obtain F0 in the FFR. Further, F0 energy

andF1energyweredetermined,using‘BrainstemToolbox’

which utilizes the FFT technique (Fig. 4), from the

tran-sientresponse(‘V’peakfor/da/stimulus;and‘a1’for/si/

stimulus) tillspecified transition duration(37ms for /a/

stimulus;and47.1msfor/si/stimulus).33

Results

The spectral data obtained at the ear canal using probe

tube measurementand FFR at brainstem level were

ana-lyzedin goodandpoor hearingaid performers.Statistical

Burst/onset

A

B

VOT

1

0

–1

25

F0

F1

GHP PHP 20

15

10

Amplitude (Arbitr

ar

y unit)

5

0

500 1000 Frequency (Hz)

1500 –30 –14 2 18 34 50

Latency(ms)

66 82 98 114 130 Transition

Stimulus

Amplitude (

µ

V)

Auto-correlation-F0

Brainstem toolbox F0 energy and F1 energy

Figure4 (A)Responsecorrespondingtostimulusattransition

portionof/da/stimulus;(B)showinggrandaveragespectrum ofGHPandPHPsub-group.(B)Fundamentalfrequencyand fre-quencyoffirstformantinFFRfor/da/stimulus.

17)softwarewasusedtoperformthestatisticalanalyses.

The results obtained are discussed with respect to each

objective.

Hearingaidoutputattheearcanal

Spectral energy at frequencies from 0.25 to 8kHz (in

octaves)intheunaidedandaidedconditions,for boththe

stimuliwasanalyzed.It wasperformed todetermine

rep-resentationofenergyacrossfrequenciesat theearcanal,

in good and poor hearing aid performers. The data of

spectral energy met the assumption of normal

distribu-tion onKolmogorov---Smirnov normality test (p>0.05) and

homogeneity onLevene’s test (F<2). The spectralenergy

(0.5---8kHzinoctaves)forbothstimuliobtainedfromboth

groups,inunaidedandaidedconditions,wassubjectedto

MANOVA.The resultrevealedthattherewasnosignificant

differencebetweengroups in thespectralenergyat each

octavefrequency,inboththeunaidedandtheaided

condi-tions,for/a/and/si/stimuli.Thus,thedataofspectral

energywascombinedbetweengroups.Descriptiveanalysis

wascarriedoutseparatelyintheunaidedandaided

condi-tions.For/a/stimulus(Fig.5),atextremelowfrequency

(0.25kHz)andatextremehighfrequencies(4kHzand8kHz)

the energy in both unaided and aided conditions is

rela-tivelyminimalthanatotherfrequencies(0.5kHz,1kHzand

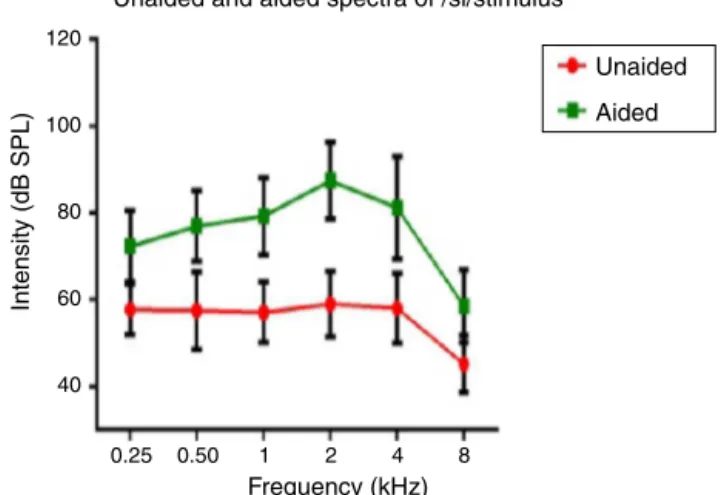

Unaided and aided spectra of /si/stimulus

120

100

80

60

Intensity (dB SPL)

Frequency (kHz)

40

0.25 0.50 1 2 4 8

Unaided

Aided

Figure5 Meanand standard deviationof intensity of/si/

stimulusasafunctionoffrequencyinunaidedandaided condi-tions.

2kHz).For/si/stimulus(Fig.6),atextremelowfrequencies

(0.25kHz)andatextremehighfrequency(8kHz)theenergy

inbothunaidedandaidedconditionsisrelatively minimal

comparedtootherfrequencies(1kHz,2kHzand4kHz).

ComparisonofFFRintermsofF0,F0energyand

F1energyingoodhearingaidperformersandpoor

hearingaidperformers

TheF0,F0energyandF1energyofFFRbetweenthegroups

foreachstimulusmettheassumptionofnormaldistribution

onKolmogorov---Smirnovnormalitytest(p>0.05)and

homo-geneityonLevene’stest(F<2)wasalsoperformed.Hence,

anindependentsamplest-testwasconductedoneachdata

ofFFRbetweenGHP(n=34)andPHP(n=24)groups.From

themeanvalueofF0ofFFR(Fig.7),itcanbeinferredthat

theF0wasrepresentedbetterinGHPthaninPHP,foreach

stimulus.Further,theF0ofFFRwascomparedbetweenGHP

andPHPusingindependentsamplestest.Theresultshowed

thattherewasasignificantbetterF0encodinginGHPthan

Unaided and aided spectra of /da/stimulus

120

100

80

60

Intensity (dB SPL)

Frequency (kHz)

40

0.25 0.50 1 2 4 8

Unaided

Aided

Figure6 Meanandstandarddeviationofintensityof/a/

P=.001

150

100

50

0

/da/stimulus /si/stimulus P=.006

GHP

Mean

±

SD of F0 of FFR

PHP

Figure7 Mean,standarddeviationandp-valueof

indepen-dentsamplest-testonF0ofFFRforeachstimulus,inGHPand

PHPgroups.

PHPfor/da/stimulus(t=3.41,p=0.001)and/si/stimulus

(t=2.84,p=0.006).

Inaddition,theF0energyandtheF1energyofFFRwas

comparedbetween GHPandPHPgroupstoeachstimulus.

FromFig.8,itwasnotedthatthemeanandstandard

devi-ationof F0 energyand F1 energy ofFFR toeach stimulus

werehigherinGHP thaninPHP.Further,toknow ifthere

wasanysignificantdifferencebetweenGHPandPHPinthe

mean the F0 energy and the F1 energy of FFR for each

stimulus,independentsamples t-testwasperformed. The

resultrevealedasignificanthigherF0energyinGHPthanin

P=.000

20

15

10

5

0

15

10

5

0

P=.000

P=.002

P=.000

Mean

±

SD of F0 energy of FFR

Mean

±

SD of F0 energy of FFR

/da/stimulus /si/stimulus

/da/stimulus

GHP PHP

/si/stimulus

Figure8 MeanandstandarddeviationofF0energy andF1

energyforeachstimulusinGHPandPHPgroups.

PHPfor/da/stimulus(t=6.80,p=0.000)and/si/stimulus

(t=6.20,p=0.000). Further,asignificant higherF1energy

wasobservedinGHPthanPHPfor/da/(t=3.11,p=0.002)

and/si/stimulus(t=5.20,p=0.000).

Discussion

Theaimofthestudywastoinvestigatetherepresentationof

amplifiedspeechattheearcanalandattheauditory

brain-stemfromthegoodandthepoorhearingaidperformers.

Effectofhearingaidprocessingonspectral parametersofspeechstimuli

Intheunaidedcondition for/da/and/si/stimuli,energy

measured at 2kHz was relatively larger than at other

frequencies (in octave). Further, there was a decline in

energyafter4kHzi.e.,anapproximately10dBperoctave

for /da/ stimulus and 12dB per octave for /si/

stimu-lus (Figs.5 and 6). This pattern of energyrepresentation

as a function of frequencies, for both the stimuli, could

be because of frequency response of microphone used in

recording the target test stimuli. In the aided condition

for /da/stimulusand /si/ stimulus,theenergymeasured

wasrelativelylessatthetwoextremecutofffrequencies,

whichisatlowfrequencybelow0.25kHzandhigh

frequen-ciesabove4kHz.Thus,atextreme frequencies,themean

energy inboth unaidedand aided conditionswas less. At

low frequency, reduced energy could be because of less

gain in that frequency region provided by the

prescrip-tive formula.34 Additionally, low energy noted in the low

frequency region of /da/ and /si/ stimulus couldalso be

becauseoffrequencyresponseofthehearingaid.Thelow

frequencycut-offofthefrequencyresponseofthetest

hear-ingaidwas0.21kHz.Athighfrequenciesi.e.,above4kHz,

theenergyreducedapproximatelyattherateof10dBper

octavefor/da/and14dBperoctavefor/si/stimulus.This

couldbethefrequencyresponseof/da/and/si/stimulus

hadenergytill4kHzasnotedfromunaidedcondition.Yet

anotherreasoncouldbethoughthefrequencyresponseof

hearingaid had0.216to6.5kHz,energyafter4kHz

grad-ually reduced per octave. Thus, remarkable energy was

notedinthefrequency rangefrom0.5kHzto4kHz.Itcan

beinferred thatthereis arelatively highamplification in

themid-frequencyregionofthehearingaidthanothertwo

extremecut-offfrequencies(lowandhigh).Informally,

par-ticipantswereinstructedtorepeatthesyllableswhichwere

randomlypresentedfor threetimes.Inunaidedcondition,

the participantswereunabletoidentify theCVtokens as

thepresentationlevelwas65dBSPL,whichfailedtoreach

audibilityrange.However,inaidedcondition,allthe

partic-ipantsconsistentlyidentifiedsyllables.Further,onspectral

analysis, it was noted that the amplitude of aided burst

spectrumof/da/wassimilartotheunprocessedburst

spec-trumamplitudeof/da/.Itwasalsoobservedthatamplitude

spectrum of fricative /si/ wassimilarto theunprocessed

fricative spectrum amplitude of /si/. This infers that

hearing aid preserves inherent speech cues at the ear

ComparisonofF0ofFFR,F0energyandF1energy

ingoodandpoorhearingaidperformers

TheFFRinbothunaidedandaidedconditionswereobtained

from all the participants. In the unaided condition, the

brainstemresponseswereabsent,asthestimuli(/da/and

/si/) were presented at 65dB SPL,which failedto reach

audibility.Intheaided condition,theF0 representationin

theFFRtoeach stimulus(/da/and/si/) remainedrobust

andsimilartothatoftheunprocessedfilteredrawstimulus.

This indicated thatpreserved spectralcontentfrom

hear-ingaidisrelayedtotheauditorybrainstemlevel.For/da/

stimulus,themeanF0ofFFRwashigherinGHP(133.46Hz)

than inPHP (128.84),such thatthe differencewasfound

tobesignificantlydifferent.ThiswastrueforF0ofFFRfor

/si/stimulusbetweenGHP(134.42Hz)andPHP(130.84Hz).

Further,theF0oftheaidedstimulusof/da/was134.95Hz

andthatfor/si/was144.74Hz.ThedifferenceinF0(inHz),

betweenencodingofF0atbrainstemlevelandF0ofaided

teststimuluswas1HzinGHPand6HzinPHPfor/da/

stim-ulus.Similarly,thedifferencenotedwas10HzinGHP and

14HzinPHPfor/si/stimulus.

The meandifferencebetween theGHP andPHPin the

encodingofF0was5Hzfor/da/and4Hzfor/si/stimulus.

ThoughthisdifferencewassignificantintheencodingofF0

betweenGHPandPHPforbothstimuli,thismaynotbring

achangeinspeakeridentity. Thisisbecause,accordingto

Iles35achangeofupto±25HzintheF

0willnotbringabout

achangeinspeakeridentity.Thefindingofthestudyisin

accordancewiththeresearchreportbyHorii36whoreported

thata differenceofgreater than25Hz inthe F0between

thesametwostimulidoes notcausedifferenceinspeaker

identity.Additionally,theintra-subjectvariabilityofF0ina

normalvocaleffortrangedbetween±9.6Hz.37Thus,itcan

beinferredthatthemeanF0ofFFRto/da/and/si/stimuli

wasneurally well represented in GHP than PHP, and that

boththegroupswereabletorecognizetheidentityofthe

speaker.

Further,itwasnotedthattheF0energyandtheF1energy

of FFR to each stimulus were significantly higher in GHP

thanPHP.ThehigherenergiesofF0andF1inGHPmightbe

duetostrongerefferentfibresthatinhibitotherharmonics

thatdonotcorrespondtofundamentalfrequency and

for-mantfrequencies.This isinaccordancewiththeresearch

reportsbyAshmore38andKnight.39Tobemorespecific,

cen-tralafferentmechanismisstrongerinthegroupofGHPsuch

thatneuronsatinferiorcolliculusfirepreciselytothe

har-monicscorrespondingtoF0andF1.Inaddition,theefferent

mechanismmightbestrongersuchthattheefferentfibres

inhibittheotherharmonicswhichdonotcorrespondtothe

fundamental frequency andformant frequencies, thereby

finetuningtheauditoryinput.Theexcitatoryandinhibitory

mechanismsofneuronsoftheunderlyingneuralgenerator

oftheinferiorcolliculusinGHPfire moreor lessprecisely

tothe correspondingF0 andF1 componentsof the

stimu-lus.Theinferenceofthepresentstudysupportsthefindings

reportedbyKrishnan.40Hedemonstratedthatefferent

audi-torypathwaysuppressesenergiesadjacenttotheharmonics

correspondingtothe F0 andthe F1 of FFR.Along withan

activeafferentpathway, theafferentauditory nerve

gen-eratestheelectricalactivity morepreciselycorresponding

to the F0 and the F1 of the stimulus. This involves the

release of neurotransmitter, thereby reducing the

trans-membranethresholdandincrease inneuralfiring. Inpoor

hearingaidperformers,thoughsimilarphysiologicalactivity

waspresent,probablyalackofprecisioninneuralactivity

dueto less sensitive afferent andweak efferent auditory

pathway,mighthavefailedtoprovidehigherenergyat

har-monicscorrespondingtoF0andF1ofeachstimulus.Thus,it

iscanbeinferredfromthepresentstudythatsubtle

physio-logicalvariationsmightbepresentattheinferiorcolliculus

oftheauditorypathwayinthepoorhearingaidperformers

withreferencetothatingoodhearingaidperformers.

Conclusion

Thoughthehearingaidpreserved inherentcuesin speech

syllables,an effectof annoyancetowardsnoise altersthe

neuralencodingat auditorybrainstemlevel. Itinfersthat

acoustic cues transferred by hearing aid are successfully

reliedat auditorybrainstem levelbut subtlephysiological

alterationswerepresentatauditorybrainsteminthose

indi-vidualswhoareannoyedfromthosewhoarenotbynoise.

Implication

Thestudypresentsanevidencetouseobjectiveapproaches

to validate the hearing aid output at ear canal and at

auditorybrainstem level. Utilization ofthe realear

mea-surementfor analyzing the hearing aid output in the ear

canalwill help in knowing the representationof inherent

speechcues.Studyingtheencodingofamplified speechin

individualswithhearing impairmentwiththeir annoyance

level demonstrates a critical role of stimulus contingent

response in the assessment of hearing aid algorithms. It

solvessome of the practical problems faced by the

audi-ologists regarding setting of amplification parameters in

providingthemaximumusableinformation.Findingsofthe

present study help the audiologist in counselling a

hear-ingaid userregarding extentof benefitderived withbest

hearingaidprescribed.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

TheauthorswouldliketothanktheDirectorandthe

HOD-Audiology, All India Institute of Speech and Hearing, for

granting permission to carry out the study. The authors

wouldalsothankalltheparticipantsofthestudyfortheir

co-operation.

References

1.Bentler RA, NiebuhrDP, Getta JP, Anderson CV.Longitudinal studyofhearingaideffectiveness.II:Subjectivemeasures.J SpeechHearRes.1993;36:820---31.

3.NemesJ.Despitebenefitsofoutcomesmeasures,advocatessay they’reunderused.HearJ.2003;56:19---25.

4.Nabelek AK.Acceptance ofbackgroundnoisemay bekey to successfulfittings.HearJ.2005;58:10---5.

5.NabelekAK,TuckerFM,LetowskiTR.Tolerationofbackground noises:relationshipwithpatternsofhearingaidusebyelderly persons.JSpeechHearRes.1991;34:679---85.

6.Nabelek AK, Freyaldenhoven MC, Tampas JW, Burchfiel SB, MuenchenRA.Acceptablenoiselevelasapredictorofhearing aiduse.JAmAcadAudiol.2006;17:626---39.

7.FreyaldenhovenMC,SmileyDF.Acceptanceofbackgroundnoise inchildrenwithnormalhearing.JEducAudiol.2006;13:27---31.

8.vonHapsburgD,BahngJ.Acceptanceofbackgroundnoise lev-elsin bilingual(Korean-English)listeners. JAmAcadAudiol. 2006;17:649---58.

9.BrannstromKJ,LantzJ,NielsenLH,OlsenSO.Acceptablenoise levelwithDanish,Swedish,andnon-semanticspeechmaterials. IntJAudiol.2012;51:146---56.

10.PlylerPN,AlworthLN,RossiniTP,MapesKE.Effectsofspeech signalcontentandspeaker genderonacceptanceofnoisein listenerswithnormalhearing.IntJAudiol.2011;50:243---8.

11.Harkrider AW, Tampas JW. Differences in responses from the cochleae and central nervous systems of females with low versus high acceptable noiselevels. JAm Acad Audiol. 2006;17:667---76.

12.Tampas JW, Harkrider AW, Hedrick MS. Neurophysiological indicesofspeechandnonspeechstimulusprocessing.JSpeech LangHearRes.2005;48:1147---64.

13.SouzaPE,TremblayKL.Newperspectivesonassessing amplifi-cationeffects.TrendsAmplif.2006;10:119---43.

14.MuellerHG.Probemicrophonemeasurement:unplugged.Hear Rev.2005;48:10---36.

15.Cunningham DR,Lao-DavilaRG, Eisenmenger BA,Lazich RW. StudyfindsuseofLiveSpeechMappingreducesfollow-upvisits andsavesmoney.JHear.2002;55:43---6.

16.StelmachowiczPG,KopunJ,MaceA,LewisDE,NittrouerS.The perceptionofamplifiedspeechbylistenerswithhearingloss: acousticcorrelates.JAcoustSocAm.1995;98:1388---99.

17.SouzaPE,TremblayKL.Combiningacoustic, electrophysiolog-icalandbehavioralmeasuresofhearingaids.Scottsdale,AZ: AmericanAuditorySociety;2005.

18.Kewley-Port D. Time-varying features as correlates of place of articulation in stop consonants. J Acoust Soc Am. 1983;73:322---35.

19.SouzaPE,TremblayKL,Davies-Venn E,KalsteinL. Explaining consonanterrorsusingshort-termaudibility.SaltLakeCity,UT: AmAcadAudiol;2004.

20.Kraus N, Nicol T. Brainstem origins for cortical ‘what’ and ‘where’ pathways in the auditory system. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:176---81.

21.Young ED, Sachs MB. Representation of steady-state vowels in the temporal aspects of the discharge patterns of

populationsofauditory-nervefibers.JAcoustSocAm.1979;66: 1381---403.

22.WordenFG,MarshJT.Frequency-following(microphonic-like) neural responses evoked by sound. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol.1968;25:42---52.

23.RussoN,NicolT,MusacchiaG,KrausN.Brainstemresponsesto speechsyllables.ClinNeurophysiol.2004;115:2021---30.

24.RussoNM, NicolTG,ZeckerSG, HayesEA,KrausN.Auditory trainingimprovesneuraltiminginthehumanbrainstem.Behav BrainRes.2005;156:95---103.

25.Johnson KL, Nicol T, Zecker SG, Kraus N. Developmen-tal plasticity in the human auditory brainstem. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4000---7.

26.Chandrasekaran B, Kraus N. The scalp-recorded brainstem responsetospeech:neuraloriginsandplasticity. Psychophys-iology.2010;47:236---46.

27.CunninghamJ,NicolT,ZeckerSG,BradlowA,KrausN. Neuro-biologicresponsestospeechinnoiseinchildrenwithlearning problems:deficitsandstrategiesforimprovement.Clin Neuro-physiol.2001;112:758---67.

28.Parbery-ClarkA,SkoeE,LamC,KrausN.Musicianenhancement forspeech-in-noise.EarHear.2009;30:653---61.

29.HornickelJ,SkoeE,KrausN.Subcorticallateralityofspeech encoding.AudiolNeurootol.2009;14:198---207.

30.HemanthN,ManjulaP.Representationofspeechsyllablesat auditorybrainstem.JIndianSpeechHearAssoc.2012;26:1---13.

31.PittmanAL, Stelmachowicz PG. Hearing lossin childrenand adults:audiometricconfiguration,asymmetry,andprogression. EarHear.2003;24:198---205.

32.SairamVVS,ManjulaP.Longtermaveragespeechspectrumin Kannada.UniversityofMysore;2002.

33.SkoeE,NicolT,KrausN.Phasecoherenceandthehuman brain-stemresponsetoconsonant-vowelsounds.In:Associationfor researchinotolaryngologysymposium.2008.

34.DillonH,KatschR,ByrneD,ChingT,KeidserG,BrewerS.The NAL-NL1 prescription procedurefor non-linear hearing aids. National Acoustics Laboratories Research and Development, Sydney:NationalAcousticsLaboratories;1998.

35.IlesMW.Speakeridentificationasafunctionoffundamental fre-quencyandresonantfrequencies.UniversityofFlorida;1972.

36.HoriiY.Fundamentalfrequencyperturbationobservedin sus-tainedphonation.JSpeechHearRes.1979;22:5---19.

37.AbbertonE.Alaryngographicstudyofvoicequality.University ofLondon;1976.

38.Ashmore JF. Afast motileresponse in guinea-pigouter hair cells:the cellular basis of thecochlear amplifier.J Physiol. 1987;388:323---47.

39.KnightRT.Distributedcorticalnetworkforvisualattention.J CognNeurosci.1997;9:75---91.