DOI: 10.1111/1746-692X.12149

What Prospects for the Brazilian Ethanol

Sector?

Quelles perspectives pour le secteur brésilien de l’éthanol ?

Welche Aussichten gibt es für den brasilianischen Ethanolsektor?

Otavio Mielnik, Felippe Serigati and Céline Giner

Brazil is the second largest producer of ethanol in the world. Brazilian ethanol is derived from sugarcane and is mostly used domestically as a transportation fuel. This article looks at the influence of Brazilian energy policies and biofuel policies on domestic ethanol supply and demand and considers the consequences of the economic and political crisis on the sector. It provides insights on the medium- term development prospects for the Brazilian ethanol industry. It considers the opportunities associated with the favourable Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emission reduction profile of Brazilian ethanol and with the development of co- generation and advanced cellulosic biofuels. It would appear that prospects for the Brazil-ian ethanol sector are potentially strong but dependent on governmen-tal commitments.

Brazilian ethanol and domestic

energy and biofuel policies

The past and recent developments of ethanol supply and demand in Brazil have been strongly related to the political environment in place. The blending of ethanol with gasoline in Brazil dates back to 1931. In 1975 in response to the first crude oil crisis, the Brazilian government created the National Alcohol Programme, ‘Proálcool’, which enacted the obligatory blending of ethanol with gasoline for transportation fuels in order to increase the country’s energy self- sufficiency.The introduction in 2003 of flex- fuel vehicles contributed to the recent development of the Brazilian ethanol

industry. Flex- fuel vehicles currently represent more than 88 per cent of light vehicle (mainly automobile) sales in Brazil. Flex- fuel vehicles can run on hydrous ethanol E100, consisting of about 95 per cent ethanol and 5 per cent water; or on gasohol, a mix of gasoline and anhydrous ethanol. In 2015, the government mandated mix of ethanol in gasohol was increased; the

gasohol currently available at the pump to Brazilians is E27, i.e. a mixture of anhydrous ethanol at 27 per cent and gasoline at 73 per cent. The automobile fleet uses E27 or E100 while diesel is the main fuel for commercial freight and agricultural vehicles.

Domestic Brazilian ethanol demand has two main components: a mandate- driven demand related to the mandatory proportion of ethanol in gasohol and a price-driven E100 demand. In addition, biofuel mandates and other support meas-ures to the biofuel sector in the United States and the European Union created a relatively modest international demand for Brazilian ethanol.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of Brazilian ethanol demand and of pure gasoline demand between 2003 and 2015. It also presents the evolution of the mandatory blending of ethanol in

gasohol. E100 has a lower calorific content per unit (21 GJ/M3) com-pared to E27 (29.2 GJ/m3). Brazilians would choose to purchase E100 rather than E27 when its pump price is less than 70 per cent of the E27 price. Given the trend in the ratio of E100 to gasohol pump prices over the past 15 years, it appears that E100 has been a better choice than gasohol for much of the period. However, during the 2011–14 period, gasoline prices – controlled by the state- owned energy company Petrobras – were kept at a lower level than interna-tional prices in an attempt to contain inflation. As a result, the relative price of ethanol was increased, which in conjunction with the rise in the international sugar price harmed the competitive position of E100 (Almei-da et al., 2015).

Figure 2 presents a decomposition of the average E100 and E27 pump prices. It illustrates that the E100 and E27 pump prices are, as expected, directly related to the wholesale prices of ethanol and gasoline as well as to the levels of Federal and State taxes. Since 2013, the differentiated state and federal fuel taxation system has been more favourable to E100 compared to E27 as taxes have been increased for gasoline and decreased for ethanol. Wholesale prices of transportation fuels take into account the distance to the major fuel production centres. Ethanol, for example, is cheaper in the Sao Paulo region where most of the ethanol is produced. Since 2015, in order to generate revenues for Petrobras, which currently faces financial distress and a corruption

scan-“

Le brésil a un rôle

majeur à jouer au

niveau mondial.

dal, fossil fuel prices were set at levels above international prices leading to improved competitiveness for E100.

The economic crisis has

weakened the ethanol sector

Brazil’s macroeconomic prospects have been deteriorating since 2014. The country faces a deep recession, growing unemployment and higher inflation. Moreover, regulatorybarriers to entrepreneurship, poor infrastructure as well as low industrial productivity and investment are affecting the country’s economic and social performance. Uncertainty about the future of the Brazilian economy has consequences for the transporta-tion sector and also the sugar and ethanol industries through various channels, such as the reduced demand for cars and gasoline and the relative taxation of gasohol and

hydrous ethanol. The current rela-tively low international price environ-ment for crude oil and the financial constraints faced by Petrobras suggest that the Brazilian market for petro-leum products faces a transition process: investments in the exploita-tion of deep- sea oil reserves off the Brazilian coast have been cut and gasoline demand might increasingly need to be met with imports. The economic crisis has also had consequences for the Brazilian ethanol sector. Over the last decade, Brazilian ethanol companies have used debt financing to meet the strong expected increase in ethanol demand. However, ethanol demand in the domestic and the foreign markets has not followed the anticipated growth path for a number of reasons, including the domestic and international economic crises and changes in the biofuel policy environment in place around the world. Many sugar and ethanol companies have used debt financing to build or upgrade production facilities, often borrowing from foreign creditors and denominating their debts in US dollars. The decline in the value of the Brazilian Real over the course of 2015 and at the beginning of 2016 has Figure 2: Decomposition of average Brazilian E100 and E27 pump prices (US$/

litre, December 2015)

Source: Preços dos combustíveis no Brasil, Paulo César Ribeiro Lima, Consultoria Legislativa,

Câmara dos Deputados, Brasília, 2016. 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 E27 E100

Distribution & Marketing State Tax

Federal Taxes

Wholesale Price of ethanol Wholesale Price of gasoline Figure 1: Evolution of Brazilian ethanol and gasoline demand between 2003 and 2015

Source: OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016.

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Pure Gasoline use Anhydrous ethanol fuel use E100 fuel use Mandatory ethanol blending in gasoline (2nd axis) Billion Litres

imposed a significant burden on these companies. According to Rabobank (2016), the sugar and ethanol industry debt has grown sharply over the last two seasons (Figure 3).

The high debt of ethanol firms reduced the rate of sugarcane field renewal leading in turn to lower productivity. The need for liquidity also created a preference for produc-ing ethanol at the expense of sugar as payment for ethanol tends to be made relatively quickly compared with sugar (ISO, 2016). In the course of 2015, however, domestic prices of sugarcane derived products increased faster than production costs. For the

first time in four years, the average profit margin of the sugarcane industry (total revenues less total expenses) was positive. However, financial conditions of many indebted less competitive Brazilian sugar- ethanol mills continued to deteriorate leading to some closures. According to UNICA (2016), among the 450 installed ethanol plants, 80 are already disabled and approximately 70 face bankruptcy.

Despite the depreciation of the domestic currency, the exports of products derived from sugarcane have not expanded over the last two years. Indeed, an increase in policy

incentives in favour of domestic ethanol demand has meant that most of the ethanol production increase was used domestically. In addition, the disconnection between domestic and international prices of ethanol – due to Petrobras fuel pricing policy – has offset the effects of exchange rate variations with the result that Brazilian ethanol is more expen-sive than US ethanol (Almeida et al., 2015).

Short- to medium- term prospects

Financial and political conditions are likely to have short- term implications for Brazilian sugar and ethanol produc-tion. For example it would appear difficult, even for economically robust companies, to finance sugarcane field renewal and machinery investments. In addition, given uncertainties about the future value of the Brazilian Real, foreign banks currently avoid purchas-ing Brazilian debt.The Brazilian ethanol sector is at a crossroads. Petrobras financial constraints may lead to a new balance in the Brazilian transportation liquid fuel market with a significant role for ethanol. The sector is restructuring with the closure of many sugar- ethanol mills in recent years and likely mergers and acquisi-tions favourable to the most competi-tive companies in the Sao Paulo region. Ethanol development in Brazil over the medium- term will be related to future prospects for the Brazilian economy, government fuel pricing policies, exchange rate developments, and changes in domestic and interna-tional biofuel policies.

The projections for the Brazilian ethanol market that are presented in the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016 are based on the assumption that the mandatory proportion of ethanol in gasohol will be kept at 27

“

Brasilien spielt

weltweit eine

bedeutende Rolle.

”

Figure 3: Sugarcane industry net banking debt (R$/sugarcane ton)Source: Rabobank (2016). 17 27 46 62 51 60 77 90 99 136 143 2005 /06 2006 /07 2007 /08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013 /14 2014/15 2015/16

Sustainability criteria and GHG reduction objectives are of increasing importance in the political agendas of major biofuel producing countries.

per cent and that the differential taxation system favourable to E100 will remain in place. In that context, Brazilian ethanol production is expected to increase by about 20 per cent over the next 10 years to meet the country’s demand for E100 and E27. It should rise to almost 35 billion litres by 2025. Net exports are projected to remain limited, given modest export opportunities in major consuming countries.

Investments in new technology

and additional revenues needed

for future growth

The current size of the Brazilian biofuels industry owes much to the existing mandates and to the political incentives favouring ethanol rather than gasoline. The Brazilian ethanol industry is asking for commitments from the government towards its long- term development. The sector needs cash flow to recover from the crisis as well as greater political certainty and investments to allow for the development of new technologies and innovations. Blending mandates set by the government will continue to play an important part in the further development of Brazilian ethanol demand.

Tax instruments are already used, mostly at the State level, to favour E100 rather than E27. There is some ongoing pressure on the government to reintroduce the national CIDE tax that was applied to fossil fuels between 2002 and 2012, designed to promote a price differential favourable to E100 (FGV, 2016). FGV has

undertaken an analysis of the impacts of a reintroduction of CIDE on E100 production net returns; this suggests that E100 economic profitability would benefit from a CIDE reintroduction with net returns from ethanol produc-tion increasing by between 3 and 20 per cent depending on the tax level.

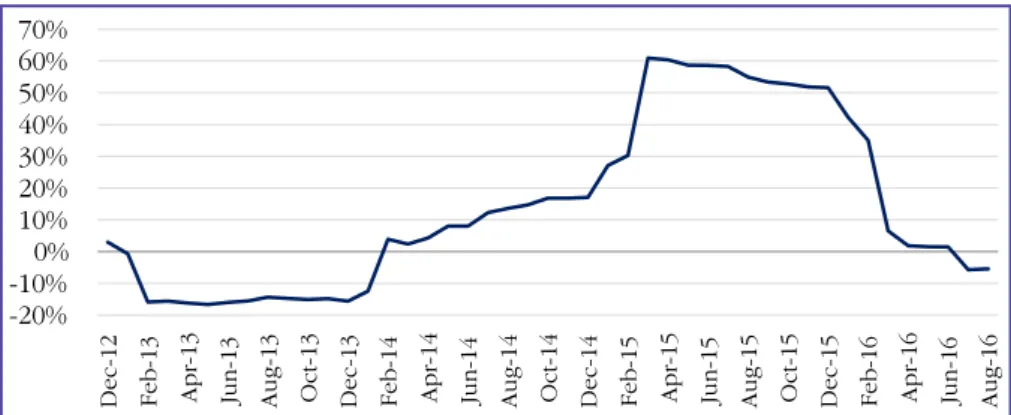

Co- generation, the thermal generation of electricity from bagasse, a byprod-uct from the sugarcane crushing process, could develop in the Sao Paulo region and increase the profitability of the ethanol sector. Co- generation could complement the Brazilian power supply system, which is heavily dependent on hydroelec-tricity. This development would require the connection of more ethanol mills to the grid and improve-ments in the terms of the contract for electric power resulting from co- generation. The new government has recently strongly increased the regu-lated price of electricity as illustrated by Figure 4. Co- generation can in that context compete with other sources of electricity.

Since 2011, the Brazilian federal government has supported the development of the ethanol industry through its Programme on Technologi-cal Innovation for the Sugar Industry. The programme finances the develop-ment of advanced ethanol production facilities, of improvements in co- generation efficiency and fosters the use of byproducts. Advanced ethanol production currently takes place on a small scale in three plants and should, according to plans, represent up to 1 per cent of Brazilian ethanol produc-tion by 2025 (EPE, 2015). Further development is likely to be sought as Brazil has ratified the Paris COP21 Agreement on Climate Change and committed to a 37 per cent reduction in GHG emissions by 2025.

Advanced ethanol in Brazil is likely to be based on sugarcane waste, a biomass feedstock that does not

compete directly with food. The development of large- scale innovative production facilities requires long- term investment and policy commitment. Economies of scale are crucial for reducing costs. In the medium- term, competition among possible alterna-tive uses of sugarcane residues – for the production of advanced biofuels or for power generation – could arise.

Promotional opportunities for

Brazilian ethanol on international

markets

Sustainability criteria and GHG reduction objectives are of increasing importance in the political agendas of major biofuel producing countries. According to recent studies (e.g. Edwards, 2014 and Valin et al., 2015), when land use change effects are taken into account, the GHG emis-sions from sugarcane based ethanol are about 50 per cent lower than the emissions of conventional fuels. Advanced biofuels based on sugar-cane waste have the potential to perform even better.

The Brazilian government in the future may use the emissions argu-ment to promote freer trade of sugarcane based ethanol as it has the best GHG emission reduction profile of all biofuels currently available on a large scale. This could make a difference in terms of ethanol export opportunities to the European Union given the sustainability criteria it has recently adopted. In the United States, the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS2) already defines sugar- cane based ethanol as an advanced biofuel.

Figure 4: Residential electricity prices in Brazil from December 2012 to August 2016 (% change, 12 months moving average)

Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

-20% -10% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% Dec-12 Feb-1 3 Apr-13 Jun-1 3

Aug-13 Oct-13 Dec-13 Feb-1

4 Apr-14 Jun-1 4 A ug-1 4

Oct-14 Dec-14 Feb-1

5 Apr-15 Jun-1 5 A ug-1 5

Oct-15 Dec-15 Feb-1

6 Apr-16 Jun-1 6 A ug-1 6

“

Brazil has a major

role to play

worldwide.

Government commitments are of

key importance

The Brazilian ethanol sector has suffered from the economic crisis. The sector is currently restructuring

and less competitive mills are likely to cease operations. The Brazilian government has recently sent strong signals towards the ethanol sector: mandatory blending obligations were increased and taxes are more

favour-able to ethanol than to gasoline. Revenues from ethanol production will grow as co- generation and the use of byproducts develops. It is expected that domestic ethanol demand will remain sustained in the medium term. To enable further GHG reduction in the transportation sector, investments are needed to develop competitive and innovative large- scale advanced ethanol production facilities in the country. Brazil has a major role to play worldwide because of its important sugarcane production capacity. Opportunities are likely to arise but will depend on governmen-tal policy commitments in Brazil and around the world.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Fernando Blumenschein for his comments, suggestions and for his help in devising the final scope of the paper.

Otavio Mielnik, Project Coordinator at FGV Projetos, Fundação Getulio Vargas, Brazil. Email: otavio.mielnik@fgv.br

Felippe Serigati, Agribusiness Centre of São Paulo School of Economics, Brazil. Email: felippe.serigati@fgv.br

Céline Giner, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Email: celine.giner@oecd.org

Further Reading

JJ Almeida, E., Oliveira, P. and Losekan, L. (2015). Impactos da contenção dos preços de combustíveis no Brasil e opções de mecanismos

de precificação. Revista de Economia Política, 35(3): 531–556.

J

J AgroANALYSIS (2016). Perspectivas do Mercado Internacional, 36(5).

J

J Cardozo, N.P. (2016). Perspectivas para a Safra 2016/17 - Região Centro/Sul. 1a Reunião Canaplan, AgroANALYSIS, 35(12). J

J Edwards, R., Larivé, J.-F., Rickeard, D., and Weindorf, W. (2014). Well-to-Wheel Analysis of future Automotive Fuels and Powertrains

in the European Context, Well-to-Tank - Version 4a, Summary of energy and GHG balance of individual pathways, JEC Technical

Reports (Brussels: EC). Available online at: https://iet.jrc.ec.europa.eu/about-jec/sites/iet.jrc.ec.europa.eu.about-jec/files/documents/ report_2014/wtt_report_v4a.pdf.

J

J Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (2015). Plano Decenal de Expansão de Energia 2024. (Ministério de Minas e Energia. Empresa de

Pesquisa. Energética. Brasília: MME/EPE).

J

J FGV (2016). The Brazilian Biofuels Industry: Recent Evolution and Major Trends. FGV Projetos Report. (FGV: Rio de Janeiro). J

J FGV IBRE (2016). The Brazilian Economy (FGV: Rio de Janeiro). J

J International Sugar Organisation (2016). Monthly market report. MECAS, (London: ISO). J

J OECD/ FAO (2016). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016-2025 (OECD Publishing: Paris). Available online at: https://doi.

org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2016-en.

J

J PECEGE/CNA (2016). Perspectivas para a Safra 2016/17: custo de produção de cana-de-açúcar, etanol e bioeletricidade no Brasil. 1a

Reunião Canaplan 1a Reunião Canaplan 2016: São Paulo.

J

J Rabobank (2016). Aspectos Econômico-Financeiros Fundamentais – Safra 2016/17. 1a Reunião Canaplan 2016: São Paulo. J

J UNCTAD (2016). Second Generation Biofuel Markets: State of Play, Trade and Developing Country Perspectives (United Nations:

New York).

J

J UNICA (União da Indústria de Cana-de-Açúcar) (2016). Coletiva de imprensa: Estimativa Safra 2016/2017 (ÚNICA: São Paulo).

Available online at: http://unica.com.br/download.php?idSecao=17&id=10968146.

J

J Valin, H., Peters, D., van den Berg, M., Frank, S., Havlik, P., Forsell, N., Hamelinck, C., Pirker, J. et al. (2015). The land use change

impact of biofuels consumed in the EU: Quantification of area and greenhouse gas impacts (ECOFYS Netherlands BV: Utrecht).

summary

Summary

What Prospects for the

Brazilian Ethanol

Sector?

Brazilian ethanol is derived from sugarcane and is mostly used domestically as a transportation fuel either pure or mixed with gasoline. Brazilians will fill their cars with pure ethanol when its pump price in energy equivalent is lower than the price of gasohol, the mandatory mixture of ethanol and gasoline. Over the last decade, Brazilian ethanol companies have used debt financing to meet the expected increase in domestic and international ethanol demand, which did not fully realise. With the current economic crisis, the ethanol sector, the second largest worldwide, is

restructuring and seeking additional earning opportunities; co- generation and valorisation of by- products are likely to develop. Political commitments towards the ethanol sector through mandatory blending obligations or the fuel taxation system are strong. Domestic ethanol demand should thus remain sustained in the medium term. In addition, sugarcane-based ethanol has the best GHG emission reduction profile of all biofuels available on a large scale. Advanced ethanol based on sugarcane derived biomass has the potential to perform even better; here Brazil has a major role to play in the future. However massive flows of investments are needed to develop competitive and innovative large- scale advanced ethanol production facilities in the country.

Quelles perspectives

pour le secteur brésilien

de l’éthanol ?

Au Brésil, l’éthanol est dérivé de la canne à sucre et est

principalement utilisé en interne comme carburant pour les transports, soit pur, soit mélangé à de l’essence. Les brésiliens remplissent le réservoir de leurs véhicules avec de l’éthanol pur lorsque son prix à la pompe en équivalent énergie est inférieur à celui du mélange obligatoire d’éthanol et d’essence, le gasohol. Au cours de la dernière décennie, les compagnies brésiliennes productrices d’éthanol ont employé le financement par la dette pour répondre à la hausse attendue de la demande d’éthanol au niveau national et international, sans y parvenir totalement. Avec la crise économique actuelle, le secteur de l’éthanol, qui occupe le second rang mondial, se restructure et cherche à diversifier ses sources de revenu; la co- production et la valorisation des sous- produits devraient se développer. Les engagements politiques envers le secteur de l’éthanol, obligation de mélange ou la fiscalité sur les carburants, sont forts. La demande nationale d’éthanol devrait donc se maintenir à moyen terme. En outre, l’éthanol tiré de la canne à sucre possède les meilleures performances en termes de réduction des émissions de gaz à effet de serre parmi tous les biocarburants disponibles à grande échelle. L’éthanol avancé à partir de la biomasse dérivée de la canne à sucre a le potentiel d’être encore meilleur; le Brésil a, dans ce domaine, un rôle majeur à jouer dans l’avenir.

Cependant, des investissements massifs sont nécessaires pour développer dans le pays des usines de production d’éthanol avancé qui soient

concurrentielles et innovantes à grande échelle.

Welche Aussichten gibt

es für den

brasilianis-chen Ethanolsektor?

Brasilianisches Ethanol stammt aus Zuckerrohr und wird hauptsächlich als Reinkraftstoff oderBenzinbeimischung im inländischen Verkehr genutzt. Wenn der Preis von reinem Ethanol je Energieeinheit niedriger ist, als der Preis von Gasohol (einer vorgeschriebenen Mischung aus Benzin und Ethanol), tanken Brasilianer ihre Autos mit reinem Ethanol. Im letzten Jahrzehnt haben brasilianische Ethanolfabriken vermehrt Fremdkapital eingesetzt, um das erwartete Wachstum der heimischen und internationalen Ethanolnachfrage decken zu können. Allerdings blieb der tatsächliche Nachfrageanstieg hinter den Erwartungen zurück. Aufgrund der Wirtschaftskrise befindet sich der brasilianische Ethanolsektor, der zweitgrößte der Welt, derzeit in einem Restrukturierungsprozess und versucht zusätzliche Einkommensmöglichkeiten zu erschließen. Hierzu zählen die Vermarktung von Strom aus der Kraft- Wärme- Kopplung und die

Aufbereitung von Nebenprodukten. Die politische Unterstützung für den Ethanolsektor durch

Beimischungsquoten oder

Steuererleichterungen ist hoch. Es ist daher davon auszugehen, dass die inländische Ethanolnachfrage mittelfristig konstant bleibt. Zusätzlich hat Ethanol aus Zuckerrohr die höchste Treibhausgasminderung von allen kommerziell verfügbaren

Biokraftstoffen. Für Biokraftstoffe der zweiten Generation könnte die Effizienz der Treibhausgasminderung noch vorteilhafter für die Rohstoffbasis Zuckerrohr ausfallen. Vor diesem Hintergrund wird Brasilien künftig eine bedeutende Rolle auf dem

Ethanolmarkt spielen. Allerdings sind massive Investitionen im Land

notwendig, um wettbewerbsfähige und innovative Produktionsanlagen für Ethanol der zweiten Generation im kommerziellen Maßstab zu entwickeln.