O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

The influence of age on posterior pelvic floor dysfunction

in women with obstructed defecation syndrome

S. M. Murad-Regadas• L. V. Rodrigues• D. C. Furtado•F. S. P. Regadas•

G. Olivia da S. Fernandes• F. S. P. Regadas Filho•A. C. Gondim•

R. de Paula Joca da Silva

Received: 28 July 2011 / Accepted: 16 March 2012 / Published online: 18 April 2012 Springer-Verlag 2012

Abstract

Background Knowledge of risk factors is particularly useful to prevent or manage pelvic floor dysfunction but although a number of such factors have been proposed, results remain inconsistent. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of aging on the incidence of pos-terior pelvic floor disorders in women with obstructed defecation syndrome evaluated using echodefecography. Methods A total of 334 patients with obstructed defeca-tion were evaluated using echodefecography in order to quantify posterior pelvic floor dysfunction (rectocele, intussusception, mucosal prolapse, paradoxical contraction or non-relaxation of the puborectalis muscle, and grade III enterocele/sigmoidocele). Patients were grouped according to the age (Group I=patients up to 50 years of age; Group

II=patients over 50 years of age) to evaluate the isolated and associated incidence of dysfunctions. To evaluate the relationship between dysfunction and age-related changes, patients were also stratified into decades.

Results Group I included 196 patients and Group II included 138. The incidence of significant rectocele, intussusception, rectocele associated with intussusception, rectocele associated with mucosal prolapse and 3 associated

disorders was higher in Group II, whereas anismus was more prevalent in Group I. The incidence of significant rectocele, intussusception, mucosal prolapse and grade III enterocele/sigmoidocele was found to increase with age. Conversely, anismus decreased with age.

Conclusions Aging was shown to influence the incidence of posterior pelvic floor disorders (rectocele, intussuscep-tion, mucosa prolapse and enterocele/sigmoidocele), but not the incidence of anismus, in women with obstructed defecation syndrome.

Keywords RectoceleObstructed defecationAnorectal ultrasonography

Introduction

Coloproctologists are increasingly aware of the importance of new research into pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) and its etiology. Knowledge of risk factors is particularly useful to prevent or manage PFD but although a number of such factors have been proposed, results remain inconsistent [1–8]. Furthermore, the choice of an appropriate treatment approach requires a detailed knowledge of pelvic floor anatomy and a complete evaluation of the anal canal and pelvis using dynamic imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [9,10] and ultrasonography (US) with different types of probes [11–17].

Murad-Regadas et al. [16] developed echodefecography, a 3D dynamic anorectal US technique using a 360 trans-ducer, automatic scanning and high frequencies for high-resolution images to evaluate evacuation disorders affecting the posterior compartment (rectocele, intussusception, anismus) and the middle compartment (grade III sigmoi-docele/enterocele). Echodefecography was subsequently S. M. Murad-RegadasL. V. Rodrigues

D. C. FurtadoF. S. P. RegadasG. Olivia da S. Fernandes

F. S. P. Regadas FilhoA. C. Gondim

R. de Paula Joca da Silva

Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Clinical Hospital, Federal University of Ceara´, Av Pontes Vieira, 2551., Ceara´, Fortaleza, Brazil

S. M. Murad-Regadas (&)

R. Atilano de Moura 430, Ap. 200, Ceara´, Fortaleza 60810-180, Brazil

standardized and shown to be strongly correlated with defecography [16,17].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of aging on the incidence of posterior pelvic floor dysfunction in women with obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) evaluated using echodefecography.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the hospital’s research ethics committee. From August 2008 to January 2010, female patients with ODS (excessive straining, vaginal splinting and sensation of incomplete evacuation) and a Wexner [18] constipation score of[6 despite increased intake of dietary fiber (up 30 g/day for 3 months) were prospectively eval-uated using echodefecography in order to quantify poster-ior PFD (grade II or III rectocele, rectal intussusception, anal canal mucosal prolapse, paradoxical contraction or non-relaxation of the puborectalis muscle, and grade III enterocele/sigmoidocele). Paradoxical contraction or non-relaxation of the puborectalis muscle was considered evi-dence of anismus.

Patients were grouped according to the age (Group I=

patients up to 50 years of age; Group II=patients over 50 years of age) to evaluate the isolated and associated incidence of posterior PFD. To evaluate the relationship between posterior PFD and age-related changes, patients were also stratified into decades (21–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–7, 71–80,[80 years).

Patients with urinary and fecal incontinence symptoms, inflammatory bowel disease, HIV, obesity and diabetic or neurological disorders were excluded, as were subjects with a history of previous colorectal, anorectal or gyne-cological surgery or pelvic radiotherapy.

Dynamic 3D anorectal US (3-DAUS) was performed using a 3D US scanner (Pro-Focus, endoprobe model 2050 and 2052, B–K Medical, Herlev, Denmark) with proxi-mal-to-distal 6.0-cm automatic scans. Images were acquired by moving two crystals (axial and longitudinal) on the extremity of the transducer, as described in previous publications [15–17], producing a merged 3D cube image recorded in real time for subsequent multiplanar analysis.

Following rectal enema, patients were examined in the left lateral position. Images were analyzed in the axial, sagittal and, if necessary, in the oblique plane by a single colorectal surgeon (SMMR) with experience in 3-DAUS. Three scans were performed:

• Scan 1—Evaluation of the anal canal anatomy at rest. • Scan 2—The transducer was positioned at 6.0 cm from the anal verge. The patient was requested to rest during the first 15 s, strain maximally for 20 s and then relax

again, with the transducer following the movement. The purpose of the scan was to evaluate the movement of the puborectalis muscle and the external anal sphincter during straining, identifying normal relaxa-tion, non-relaxation or paradoxical contraction and prolapse of the anal canal mucosa (corresponding to the thickness of the subepithelial tissue during straining). • Scan 3—Following injection of 120–180 mL US gel

into the rectal ampulla, the transducer was positioned at 7.0 cm from the anal verge. The scanning sequence was the same as in Scan 2, visualizing and quantifying all anatomical structures and functional changes associated with defecation (rectocele and grade of rectocele, rectal intussusception and grade III sigmoidocele/enterocele) (Fig.1). Lesser grades of sigmoidocele/enterocele cannot be identified with this technique due to the position of the transducer (7.0 cm from the anal verge).

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the chi-square test. Age-related changes were evaluated with chi-square for trend, using the software GraphPad Prism version 5.00. The level of statistical significance was set atp\0.05.

Results

A total of 334 women were included in this study. The median age was 49±14.7 years (range: 17–91 years), and

the median constipation score was 9 (range: 7–15). Group I included 196 patients (median age: 43 ±6.2 years):

Sixty-nine were nulliparous, 59 had undergone one or more vaginal deliveries (median: 2; range: 1–7), and 68 had had one or more cesarean sections (median: 2; range: 1–3) without labor or vaginal delivery. Group II included 138 patients (median age: 62±7.2 years): 51 were

nullipa-rous, 50 had undergone one or more vaginal deliveries (median: 2; range: 1–5), and 37 had had one or more cesarean sections (median: 2.0; range: 1–3) without labor or vaginal delivery. The two groups did not differ signifi-cantly with regard to the distribution of parity and mode of delivery (p =0.2722).

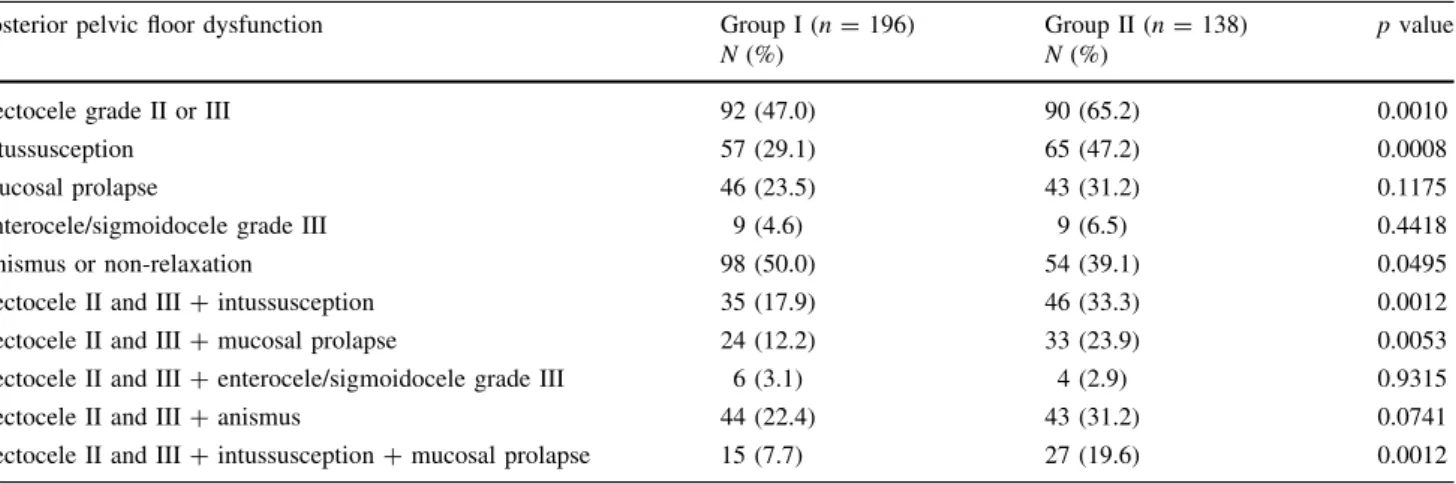

The incidence of posterior PFD in women with ODS is shown for both groups in Table1.

The incidence of significant rectocele, rectal intussus-ception, mucosal prolapse and grade III enterocele/sigmo-idocele was found to increase with age (Table2). Conversely, anismus decreased with age (Table2).

Discussion

The pelvic floor is subdivided into 3 (anterior, medium and posterior) anatomically complex compartments of muscles, ligaments, nerves and pelvic organ support structures. PFD

may therefore affect a range of different structures, pro-ducing a spectrum of isolated or associated clinical symptoms, including urinary and anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and ODS. PFD may be evaluated by a combination of clinical and radiological examinations, including defecography, dynamic US and dynamic MRI [9–22]. Recent advances in US probe technology have made it possible to conduct detailed studies on the anatomy of the anal canal and pelvic floor, and new US modalities have been developed which can evaluate all pelvic floor compartments [23–25].

Fig. 1 (Sagittal plane). Using gel in the rectum.aPatient without rectocele. Vagina is pushed downwards and backwards through the anterior rectal wall.bRectocele (grade III).EASexternal anal sphincter,IASinternal anal sphincter,PRpuborectalis muscle

Table 1 Incidence of posterior pelvic floor dysfunction in female patients with obstructed defecation syndrome by age

Posterior pelvic floor dysfunction Group I (n=196) Group II (n=138) pvalue

N(%) N(%)

Rectocele grade II or III 92 (47.0) 90 (65.2) 0.0010

Intussusception 57 (29.1) 65 (47.2) 0.0008

Mucosal prolapse 46 (23.5) 43 (31.2) 0.1175

Enterocele/sigmoidocele grade III 9 (4.6) 9 (6.5) 0.4418

Anismus or non-relaxation 98 (50.0) 54 (39.1) 0.0495

Rectocele II and III?intussusception 35 (17.9) 46 (33.3) 0.0012

Rectocele II and III?mucosal prolapse 24 (12.2) 33 (23.9) 0.0053

Rectocele II and III?enterocele/sigmoidocele grade III 6 (3.1) 4 (2.9) 0.9315

Rectocele II and III?anismus 44 (22.4) 43 (31.2) 0.0741

The patients of this study were evaluated using echo-defecography to identify the isolated or associated poster-ior PFD (rectocele, intussusception, anismus, mucosal prolapse and grade III sigmoidocele/enterocele) and plan for appropriate treatment. Using echodefecography, all anatomical structures of the posterior pelvic floor and changes during straining and voiding can be visualized in real time and multiple planes. Despite the differences in the position of the patient and the probe, echodefecography and defecography findings have been shown to be strongly correlated, even when comparing findings from different centers [16].

The incidence of significant rectocele, anismus, rectal intussusception, anismus and enterocele/sigmoidocele observed in this study for women with ODS was compa-rable to that of other series [26–28]. In our sample of patients with ODS, significant rectocele was the most prevalent form of posterior PFD.

Previous studies have focused on the correlation between PFD (e.g., urinary and anal incontinence), obstetrical trauma and age [2, 29–33], but the correlation between ODS, parity, vaginal delivery and age remains controver-sial [1, 4–8]. Several studies have found a relationship between vaginal delivery and ODS [1, 34, 35]. In other series, the incidence of posterior PFD was similar for nulliparous women and women with a history of vaginal delivery [5–7, 36]. In the present study, the objective was to determine the impact of aging on the incidence of posterior PFD in 2 different age groups of ODS patients with similar distribution of parity and mode of delivery. The confounding effect of vaginal delivery was therefore eliminated from the risk factors for PFD.

Hendrix et al. [1] reported a very high incidence of pelvic floor organ prolapse in post-menopausal women. Nevertheless, according to Dietz [4], aging plays a limited role in the pathogenesis of pelvic organ prolapse and the degree of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse is not associated with age. This contradicts the results of an epidemiological study showing PFD to be common in women and strongly associated with aging [8]. In our study, the incidence of isolated posterior PFD (such as significant rectocele or rectal intussusception), associated

posterior PFD (such as significant rectocele with rectal intussusception or significant rectocele with mucosal pro-lapse) and 3 associated pelvic floor disorders (significant rectocele associated with rectal intussusception and mucosal prolapse) was higher among women over 50 years of age. In addition, the incidence of posterior PFD (sig-nificant rectocele, rectal intussusception, mucosal prolapse and grade III enterocele/sigmoidocele) increased with age. Wijffels et al. [37] demonstrated that internal rectal prolapse grade increases with age. The higher incidence may be explained by age-related deterioration of the pelvic organ support structures. Discrepancies in published results are possibly due to differences in study population, diagnostic methods (clinical or radiological) and clinical entities.

On the other hand, changes in anal canal anatomy, internal anal sphincter degeneration and external anal sphincter atrophy have been associated with aging in nul-liparous subjects as well [38]. Thus, based on a review of the literature, while aging predisposes to PFD, the exact pathogenic mechanism is unclear. Tissue atrophy in women over 50 years of age (menopausal status) resulting in reduced distensibility [39] does, however, seem to be a key factor.

Patients with ODS and paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle and the external anal sphincter are often diagnosed with anismus—a disorder not uncom-monly associated with psychological distress [40]. In contrast, the present study found that anismus was more prevalent in younger patients and decreased over time [41]. Again, discrepancies may be due to differences in study population.

We excluded patients with urinary and fecal inconti-nence and subjects with a history of proctological and gynecological surgery to ensure that the study population was as homogenous as possible. It was therefore not pos-sible to investigate the correlation between the incidence of grade III enterocele/sigmoidocele and hysterectomy.

The relevance of our study lies in the fact that it used echodefecography to evaluate the impact of aging on the incidence of isolated and associated pelvic floor disorders in different age groups of women with symptomatic ODS Table 2 Incidence of posterior pelvic floor dysfunctions in female patients with obstructed defecation syndrome in each of the age groups

Dysfunction (%)

Age groups (years) pvalue

21–30 31–40 41–50 51–60 61–70 71–80 [80

Rectocele grade II/III 13.0 31.8 62.4 67.5 65.6 61.1 66.7 0.0001

Intussusception 26.1 22.7 33.0 38.7 56.2 61.1 83.3 0.0001

Mucosal prolapse 9.5 24.2 25.7 27.5 34.4 38.9 50.0 0.0098

Enterocele/sigmoidocele 0 7.6 3.7 2.5 9.4 11.1 33.3 0.0431

without fecal or urinary incontinence symptoms. To further determine the role of aging in the pathogenesis of PFDs in all three compartments, longitudinal studies based on clinical and radiological tests are required.

Conclusions

Aging was shown to influence the incidence of posterior PFDs (significant rectocele, intussusception, mucosa pro-lapse and enterocele/sigmoidocele), but not the incidence of anismus, in women with ODS.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A (2002) Pelvic organ prolapse in the women‘s health initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:1160–1166 2. Serati M, Salvatore S, Khullar V et al (2008) Prospective study to assess risk factors for pelvic floor dysfunction after delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 87:313–318

3. Meyer S, Schreyer A, De Grandi P, Hohlfeld P (1998) The effects of birth on urinary continence mechanisms and other pelvic-floor characteristics. Obstet Gynecol 92:613–618

4. Dietz HP (2008) Prolapse worsens with age, doesn’t it? Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 48:587–591

5. Soares FA, Regadas FS, Murad-Regadas SM et al (2009) Role of age, bowel function and parity on anorectocele pathogenesis according to cinedefecography and anal manometry evaluation. Colorectal Dis 11:947–950

6. Murad-Regadas SM, Regadas FSP, Rodrigues LV et al (2009) Types of pelvic floor dysfunctions in nulliparous, vaginal deliv-ery, and cesarean section female patients with obstructed defe-cation syndrome identified by echodefecography. Int J Colorectal Dis 10:1227–1232

7. Murad-Regadas SM, Peterson TV, Pinto RA, Regadas FS, Sands DR, Wexner SD (2009) Defecographic pelvic floor abnormalities in constipated patients: does mode of delivery matter? Tech Coloproctol 13:279–283

8. Kepenekci I, Keskinkılıc B, Akınsu F et al (2011) Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in the female population and the impact of age, mode of delivery, and parity. Dis Colon Rectum 54:85–94 9. Lienemann A, Anthuber C, Baron A, Kohz P, Reiser M (2004)

Dynamic MR. Colpocystorectography assessing pelvic floor descent. Eur Radiol 7:1309–1317

10. Dvorkin LS, Hetzer F, Scott SM, Williams NS, Gedroyc W, Lunniss PJ (2004) Open magnet MR defaecography compared with evacuation proctography in the diagnosis and management of patients with rectal intussusception. Colorectal Dis 6:45–53 11. Barthet M, Portier F, Heyries L (2000) Dynamic anal

endoson-ography may challenge defecendoson-ography for assessing dynamic anorectal disorders: Results of a prospective pilot study. Endos-copy 32:300–305

12. Beer-Gabel M, Teshler M, Schechtman E, Zbar AP (2004) Dynamic transperineal ultrasound vs. defecography in patients with evacuatory difficulty: a pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis 19:60–67

13. Dietz HP, Steensma AB (2005) Posterior compartment prolapse on two-dimensional and three-dimensional pelvic floor ultra-sound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hyper-mobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26:73–77 14. Piloni V, Spazzafumo L (2005) Evacuation sonography. Tech

Coloproctol 9:119–126

15. Murad-Regadas SM, Regadas FS, Rodrigues LV et al (2007) A novel procedure to assess anismus using three-dimensional dynamic anal ultrasonography. Colorectal Dis 9:159–165 16. Murad-Regadas SM, Regadas FS, Rodrigues LV, Silva FR,

So-ares FA, Escalante RD (2008) A novel three-dimensional dynamic anorectal ultrasonography technique (echodefecogra-phy) to assess obstructed defecation, a comparison with defec-ography. Surg Endosc 22:974–979

17. Regadas FSP, Lima Barreto RG, Murad-Regadas SM, Veras Rodrigues L, Pereira Oliveira LM (2012) Correlation between anorectocele with the anterior anal canal and anorectal junction anatomy using echodefecography. Tech Coloproctol 16:133–138 18. Agachan F, Pfeifer J, Wexner SD (1996) Defecography and proctography: results of 744 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 39: 899–905

19. Felt-Bersma RJ, Luth WJ, Janssen JJ, Meuwissen SG (1990) Defecography in patients with anorectal disorders. Which find-ings are clinically relevant? Dis Colon Rectum 33:277–284 20. Kelvin FM, Hale DS, Maglinte DD, Patten BJ, Benson JT (1999)

Female pelvic organ prolapse: diagnostic contribution of dynamic cystoproctography and comparison with physical examination. Am J Roentgenol 173:31–37

21. Marti MC, Roche B, Dele´aval J (1999) Rectoceles: value of video-defecography in selection of treatment policy. Colorectal Dis 1:324–329

22. Chen HH, Iroatulam A, Alabaz O, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD (2001) Associations of defecography and physiologic findings in male patients with rectocele. Tech Coloproctol 5:157–161 23. Groenendijk AG, Birnie E, Boeckxstaens GE, Roovens JP,

Bonsel GJ (2009) Anorectal function testing and anal endoson-ography in the diagnostic work-up of patients with primary pelvic organ prolapse. Gynecol Obstet Invest 67:187–194

24. Santoro GA, Wieczorek AP, Stankiewicz A, Wozniak MM, Bogusiewicz M, Rechbereger T (2009) High-resolution three dimensional endovaginal ultrasonography in the assessment of pelvic floor anatomy: a preliminary study. Int Urogynecol J 20: 1213–1222

25. Dietz HP (2010) Pelvic floor ultrasound: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202:321–334

26. Porter WE, Steele A, Walsh P, Kohli N, Karram MM (1999) The anatomic and functional outcomes of defect-specific rectocele repairs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181:1353–1359

27. Thompson JR, Chen AH, Pettit PMD, Bridges MD (2002) Incidence of occult rectal prolapse in patients with clinical rectoceles and defecatory dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:1494–1500 28. Renzi A, Izzo D, Di Sarno G et al (2006) Cinedefecographic

findings in patients with obstructed defection syndrome. A study in 420 cases. Minerva Chir 61:493–499

29. Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S, Norwegian EPINCONT Study (2009) Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med 348:900–907 30. Peschers UM, Schaer GN, DeLancey JO, Schuessler B (1997)

Levator ani function before and after childbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104:1004–1008

31. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI (1993) Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 329:1905–1911

33. Snooks SJ, Swash M, Mathers SE, Henry MM (1990) Effect of vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor: a 5-year follow-up. Br J Surg 77:1358–1360

34. Felt-Bersma RJF, Cuesta MA (2001) Rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception, rectocele and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 30:199–222

35. Finco C, Luongo B, Savastano S, Polato F (2007) Selection cri-teria for surgery in patients with obstructed defecation, rectocele and anorectal prolapse. Chir Ital 59:513–520

36. Dietz HP, Clarke B (2005) Prevalence of rectocele in young nulliparous women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 45:391–394 37. Wijffels NA, Collinson R, Cunningam C, Lindsey I (2010) What

is the natural history on internal rectal prolapse? Colorectal Dis 12:822–830

38. Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Lame´ris JS (2000) Normal anal sphincter anatomy and age- and sex-related variations at high-spatial resolution endoanal MR imaging. Radiology 217:395–401 39. Goh J (2002) Biomechanical properties of prolapsed vaginal tissue in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int Urogynecol J 13:76–79

40. Wald A, Hinds JP, Caruana BJ (1989) Psychological and physi-ological characteristics of patients with severe idiopathic consti-pation. Gastroenterology 97:932–937