George Avelino Filho FGV-EAESP George.avelino@fgv.br Leonardo Sangali Barone

FGV-EAESP leobarone@gmail.com

Paper prepared for the 68th Annual Midwest Political Science Association Conference Panel: Territorial Politics: Regional Parties, Elections, and Governments.

Chicago 2010

PRELIMINARY VERSION: PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION.

Abstract

The scholarship on the accountability of local incumbents usually focuses on two main hypotheses. The first, the sub-national vote, argues that voters rely mostly on information on incumbent’s local performance. The second hypothesis, the referendum vote, argues that is voters´ decision give more weight to national aspects, particularly their assessment of the president’s performance. In this last case, the electoral fate of local incumbents would be determined by aspects outside their reach.

In this paper we test those two hypotheses for the Brazilian case using a data set on 131 governor’s elections for the 27 Brazilian states between 1990 and 2006. To our knowledge, this is the first time these two hypotheses are tested in a multiparty context, since previous studies focused mainly on two-party systems.

Our results show no support for the referendum hypothesis, as national variables did not have any effect on the probability of governors´ reelection. Among the local variables, there is a negative effect from state fiscal deficits, a result that contradicts

Introduction

In the last three decades, new democracies in Latin America experienced a strong decentralization process and an increasing participation of the sub-national levels of government in the provision of public services. However, while decentralization has been a recurrent theme on the literature on sub-national governments, governor´s accountability to state voters and what defines voters´ decision in state elections has been less debated in a comparative way.

According to the scholarship on the accountability of state governors, the electoral success of a national incumbent has a local and a national component. Voters would assess sub-national officials based on information from both local and sub-national economic performance (Rodden, 2004, Ebeid and Rodden 2006). In the economic voting literature, these components are respectively associated with sub-national voting – in this case, voters privilege information on local economic performance – and referendum voting – in this last case, voters privilege information on national economic performance and use sub-national elections to reward or punish incumbents that show partisan links with the president.

In this paper, we investigate whether these two hypotheses hold for Brazilian sub-national governments. We use a data set on 131 governors elections for the 27 Brazilian states between 1990 and 2006 to test if Brazilian voters hold state governors accountable for local or national economic performance. Do Brazilian voters use information about the economy to evaluate governor’s performance? Does the national economic performance influence state elections through partisan links between state candidates and the president?

Several theoretical and empirical reasons make Brazil an interesting case to study the accountability of state governors. On the theoretical side, following Remmer and Gélineau (2003) and Gelineau and Remmer (2006), we explore the applicability of economic voting models on sub-national governments outside the context in which it was initially developed. Economic voting models were first designed to explain national electoral results, especially in the United States (Kramer, 1971; Tufte, 1975; Fiorina, 1978; Kiewet,

1981; Abramovitz, Segal, 1996). Only more recently these models have extensively been applied to explain electoral outcomes in sub-national elections in federal systems (Peltzman, 1987; Chubb, 1988; Stein, 1990; Simon, Ostrom and Marra, 1991; Atkson and Partin, 1996; Lowry, Alt and Ferree, 1998; Ebeid and Rodden, 2001; 2006; Gélineau, 2002; Gélineau and Belanger, 2003; 2005; Remmer and Gélineau, 2003; 2005; Rodden and Wibbels, 2005; Leigh and McLeish, 2008), but still the United States remained the focus. The resilience of a theory depends mostly on its capacity to travel, that is, its capacity to explain empirical problems outside its place of birth.

Secondly, these models were applied exclusively in two-party contexts, were candidates´ parties can be easily labeled as incumbents or challengers.1 Brazil is well known for its multi-party system and we make an effort to test economic voting models within this context. Between 1990 and 2006 politicians from 15 different parties were elected for state government. Moreover, even a preliminary observation over election results will show a high level of political competition at state level; that is, the institutional environment does not provide governors incumbents with significant electoral advantages over their challengers.2

Third, state level institutions are key to understanding Brazilian politics. State governments are responsible for more than one third of the public spending, and perform an essential role in the provision of public services such as education and health. In other words, Brazilian states provide an interesting test for the capacity of policy decentralization to fulfill expectations about increasing accountability at local levels

On the empirical side, Brazil is one of the largest democracies in the world and the largest in Latin America. It has been a federation for more than a hundred years, since the birth of the Brazilian Republic in 1889.

1

This assertion is valid even for Argentina; as argued by Gelineau and Remmer (2005, p. 140), Argentinan electoral competition has been structured around two main parties: the Partido Justicialista (PJ) and UCR/Alianza (Unión Cívica Radial /Alianza).

2 State governors’ ability to manipulate fiscal policy instruments to influence voters is similar for all states.

See Santos (2001) for several case studies. The general conclusion of this comparative book is that institutional constraints on budgeting are similar to all states, with a greater influence from the local executive in the budgeting process vis-à-vis the legislative.

Additionally, there is a great variation in socio-economic variables across Brazilian states. For instance, in 2003 the GDP per capita of the two richest states Sao Paulo and the Federal District was around US$ 5500, similar to a country like the Chile or the Czech Republic; in contrast, the GDP per capita for the two poorest states, Maranhão e Piauí, was about US$ 850, which would be similar to the Cameroon or the Guinea-Bissau.3

Last, but not least, since the democratization, in 1985, Brazilian governmental institutions have been made great efforts to produce good quality data on states´ public finance.

Our results show no support for the referendum hypothesis. National variables did not show any significant effect on the probability of governors´ reelection. Among the local

variables, there is a negative effect from state fiscal deficits, a result that contradicts usual expectations on new democracies.

Data and Method

We draw electoral data for our analysis from the Tribunal Superior Eleitoral (TSE), which publishes electoral results for all the Brazilian elections. Economic and financial data are drawn from the Secretaria do Tesouro Nacional (STN-MF), Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas Aplicadas (IPEA), and from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE).

Brazil holds direct and competitive elections for state governors since 1982, even before the end of the military dictatorship. However, we decided not to include the elections previous to 1990 for some reasons. First of all, in 1988 the Brazilian Congress promulgated a new Constitution and important aspects of the relation between central and local governments changed.

Further, before 1989 presidential elections the party system passed through an intense process of party differentiation. Under the military rule, only two parties, the governmental party ARENA (Aliança Renovadora Nacional) and the opposition party MDB (Movimento Democrático Brasileiro), were legally allowed to run for legislative elections. The imposed two-party system was extinguished only in 1979, and the party system was not completely established until the mid 90´s

State and national elections for both executive and legislative branches in Brazil are held simultaneously in a four-year regular basis. The only exception is the 1990 elections, when the president had already been elected for a five-year term in 1989. Election rules are defined by a national Electoral Justice Court (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral - TSE) and do not vary among states. Reelection was not allowed for the executive branch until 1998. Except for the 2002 elections, national coalitions did not bind state level coalitions and political parties can freely negotiate regional alliances. Besides that, the main aspects of the electoral rules remained constant since 1990. Voting is compulsory in Brazil and we expect no endogenous effects of electoral mobilization.

Considering all the 27 states and elections since 1990, the data comprises a total of 134 gubernatorial elections. Three states and the Federal District did not exist or did not hold state elections in 1986. Since there were no incumbents in these states in 1990, these four states were excluded for this year.

To indentify and label incumbent party running for reelection and opposition party challenging the incumbent is much easier in a two-party then in a multi-party context. The Brazilian political system is well known for party fragmentation, high levels of electoral volatility and party disloyalty and low institutionalized political parties (Mainwaring, 1991, 1995,1999; Ames 1994, 1995, 2000; Samuels, 2000).

Ebeid and Rodden (2006) and Rodden and Wibbels (2005) conducting similar studies for other federal countries choose incumbent’s party vote share as the dependent variable. Since we have to take into account the Brazilian multi-party context, we cannot use the

incumbent’s party vote share. Instead, we used a dummy variable to indicate reelection and we considered a reelection case every time the incumbent, or the candidate supported by the incumbent’s party, won the election.4 Doing so, we avoid excluding the cases in which the incumbent party did not run for reelection but supported a local ally running for other party. In 30% percent of the state elections between 1996 and 2006, the winner party in the previous election did not ran for the state government and in 10% of these cases it did not even participated in any electoral coalition.

TABLE 1.

Brazilian State Elections from 1990 to 2006

Year

1990 1994 1998 2002 2006 Total

Incumbent governor ran for reelection for the

same party she/he was elected 0 0 13 9 11 33

Incumbent governor ran for reelection for

another party 0 0 5 0 3 8

Governor’s party participated in the election

heading a coalition 14 13 5 12 6 50

Governor’s party participated in the election

not heading a coalition 6 6 2 4 4 22

Governor supported a non-partisan ally from a party that support her/his candidacy in the

previous election 1 1 1 2 0 5

Governor supported a non-partisan ally 2 4 1 0 3 10

Governor do not support any candidacy 0 3 0 0 0 3

Total 23 27 27 27 27 131

Source: Authors, data from TSE and IUPERJ

TABLE 1, above, shows the classification of all 131 elections present in our data set. When the incumbent governor, or the candidate supported by the governor, won the election, we coded our dependent variable REELECTION as 1; otherwise, we coded our dependent variable REELECTION as 0 (zero). Since our dependent variable is binary, we used logistic regression to estimate the parameters.

4 Since electoral coalitions need to be formalized in electoral courts, it is easy to identify

In almost 70% of the cases, the incumbent governor party or the governor herself/himself ran for reelection. If we consider only the period between 1998 and 2006, when reelection was allowed, and the party system was completely established, incumbent reelection (party or governor) goes to 79%. Finally, approximately two thirds of the governors who could run for reelection did it.

TABLE 2.

Candidate that represents government continuation

Year

1990 e 1994 1998 a 2006 Total

Nº (%) Nº (%) Nº (%)

Incumbent governor or incumbent

partisan 27 54% 64 79% 91 69%

Non partisan (electoral coalition) ally 23 46% 17 21% 40 31%

Total 50 100% 81 100% 131 100%

Source: Authors, data from TSE and IUPERJ

Had we included in our analysis only the cases in which the incumbent was personally running for reelection, or even the cases in which the governors’ party is heading the supported candidate coalition, we would risk incurring in selection bias.5 We would also lose a significant number of observations. To differentiate when the incumbent is the candidate from the cases in which the governor is supporting a partisan or a candidate from an allied party, we include in all models a dummy variable called INCUMBENT which assume value 1 if the governor is personally running for reelection and 0 otherwise.

Our main independent variables are the economic results and budget performance for the Brazilian states in the election year. In the economic voting literature, income growth, unemployment and inflation rates are the most common measures of economic performance. Considering Brazil has gone through a hard period of hyperinflation, inflation rates are potentially important to explain reelection. Unfortunately, inflation data are

5 The probability of a governor, or an incumbent party, to run for reelection would be positively related to

collected only for the national level and a few metropolitan areas and we were not able to include it in our statistical model

Similarly to inflation rates, unemployment rates are not collected nationally. However, using an annually applied household survey, the PNAD (Pesquisa Nacional de Amostra de Domicílios – IBGE), we built a measure of state unemployment for all the states and electoral years. Thus UNEMP_STATE represents the state unemployment rate in the electoral years and UNEMP_NATION represents the unemployment rate for the whole country in the electoral year. We subtract UNEMP_NATION from UNEMP_STATE to calculate UNEMP_RELATIVE.

We collect GDP data for all the states and calculate income growth rates from IBGE and IPEA. INCOME_STATE represents the state income growth rate and INCOME_NATION represents the national income growth rate in the electoral years. INCOME_RELATIVE is the difference between the two of them.

All specifications include a governmental budgetary variable, named BUDGET. It represents the net difference between state government revenues and spending as a portion of the state government revenue. We also included a measure of the state capacity of generating tax revenue, named TRIBUT, which represents the state own tax revenues as a percentage of the total revenues.

Finally, we create two variables to indicate the candidate for state governor partisanship. The first one, COATTAIL is coded 1 if the candidate is a partisan of the winner candidate in the simultaneous presidential election and 0 otherwise. The other one, PRES_PARTY, indicates if the candidate is a member of the incumbent president’s party. It is coded 1 if the candidate in the state elections is a member of the presidential party and 0 (zero) otherwise.

TABLE 3. Variables Definition

Variable Description Source

REELEITO

(Dependent Variable) 1 if the governor or a supported partisan or non-partisan ally was elected; 0 if there was a government change TSE; IUPERJ

INCUMBENT 1 if sitting governor is personally running for reelection; 0 otherwise TSE; IUPERJ

COATTAIL 1 if the candidate is a partisan of the winner in the simultaneous presidential election; 0 otherwise

TSE; IUPERJ BUDGET

Budget surplus as a percentage of the state revenues (negative values

mean budgetary deficits) STN/MF

INCOME_STATE State income growth in the reelection year IPEADATA

INCOME_NATIONAL National income growth in the reelection year IPEADATA

INCOME_RELATIVE INCOME_STATE (-) INCOME_NATIONAL IPEADATA

UNEMP_STATE State unemployment in the election year

PNAD (IBGE)

UNEMP_NATIONAL National unemployment in the election year PNAD (IBGE)

UNEMP_RELATIVE UNEMP_STATE (-) UNEMP_NATIONAL PNAD (IBGE)

PRES_PARTY 1 if the candidate is a partisan of the president whose term in ending in the election year; 0 otherwise TSE; IUPERJ

TRIBUT Own tax revenues as a percentage of the state revenues STN/MF

Empirical analysis

Following previous research, we have constructed a simple model of sub-national voting. At first, we ignore the effects of the national economic performance on the state elections and assume that the governor is fully responsible for the economical results of its state. Therefore, we employ the following model:

Ln(Reelection) = β0 + β1*(Incumbent effect)ij + β2*(Coattail effect)ij + β3*(State budget) + β4*(Income)ij + β5*(Unemployment)ij + Ɛij

In the above model, we only include two state economy variables (UNEMP_STATE and INCOME_STATE), the state budget variable (BUDGET) and control variables for incumbent and coattail effects (INCUMBET and COATTAIL). We expect the state economic outcomes and budget surplus to be associated with the dependent variable REELECTION. We use both income and unemployment measures alone and jointly so we could avoid the possible effect of high correlation among them. Unfortunately we were not able to include fixed effects because some observations would be dropped due to collinearity with the dependent variable. The results for the three specifications of this model are reported in TABLE 4:

TABLE 4.

A simple model of sub-national economic vote

I II III INCUMBENT 1.336 *** 1.328 *** 1.328 *** (0.423) (0.431) (0.431) COATTAIL 0.146 0.116 0.144 (0.653) (0.651) (0.653) BUDGET 0.023 * 0.024 ** 0.023 * (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) INCOME_STATE 0.012 0.012 (0.015) (0.015) UNEMP_STATE 0.018 0.005 (0.061) (0.063) CONSTANT -0.750 *** -0.823 * -0.786 (0.273) (0.494) (0.497) N 128 128 128

Standard errors in parentheses

*** significant at 0.01; ** significant at 0.05; * significant at 0.1 OBS: dependent variable = REELECTION

As expected, INCUMBENT is significant and positive at 0.01 at all the specifications. It means that when the governor personally run for reelection the probability of winning the state elections is approximately 3.8 higher than when the governor is supporting a partisan or a non-partisan ally. In fact, 71.43% of the governors that ran for a second term were reelected. By contrast, as COATTAIL is not significant, we do not find evidence that governor candidates, who are partisans of the winner in the simultaneous presidential elections, have a higher probability of being elected. Moreover, none of the two measures

of the state economy performance, state unemployment and state income growth, is significant in any of the three specifications. Finally, budgetary surplus shows a constant and positive effect in all specifications, confirming previous results by Arvate et all (2009).

If voters use national economic performance to punish or reward president partisans in the state elections, we should test if national economic variables affect governors’ success in running for reelection. In Brazil, since 1994, the presidential and state elections occur concurrently, a context that makes expectations borne by the referendum vote approach more plausible. State governors associated with a sitting president with a good economic performance are expected to have better chances of getting reelected.

Thus, we substituted in our model the state economic performance variables for national variables (UNEMP_NATIONAL and INCOME_NATIONAL) and for the difference between the national and state economic performance (UNEMP_RELATIVE and INCOME_RELATIVE). Since we expect that only the president partisans will be affected by the national economic performance, we interacted the national economic variables with a dummy variable that indicates partisanship with the president (PRES_PARTY). Model IV in table 5, below, conforms the following specification:

Ln(Reelection) = β0 + β1*(Incumbent effect)ij + β2*(Coattail effect)ij + β3*(State budget)ij + β4*(Relative state income)ij + β5*(National income)ij + β6*(National income)ij*(Presidential party)ij + β7*(Presidential party)ij + Ɛij

As we can see in TABLE 5, the substitution of the state economic performance for the national economic performance and the relative measure does not change our results. The only two variables that seem to explain governors’ reelections are budget surplus and incumbent effect. BUDEGT is now significant at 0.05 and incumbency effect keeps its significance. Neither national nor state economic conditions impact the odds of government change in Brazilian states.

TABLE 5.

Sub-national versus Referendum vote

IV V VI INCUMBENT 1.388 *** 1.382 *** 1.412 *** (0.432) (0.474) (0.514) COATTAIL -0.170 -0.225 0.001 (0.780) (0.767) (0.893) BUDGET 0.024 ** 0.025 ** 0.024 ** (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) INCOME_RELATIVE 0.022 0.024 (0.019) (0.020) INCOME_NATIONAL -0.007 -0.014 (0.029) (0.049) INCOME_NATIONAL (*) PRES_PARTY 0.012 0.052 (0.078) (0.143) UNEMP_RELATIVE 0.026 0.044 (0.079) (0.083) UNEMP_NATIONAL -0.010 0.026 (0.103) (0.178) UNEMP_NATIONAL (*) PRES_PARTY 0.007 -0.174 (0.286) (0.525) PRES_PARTY 0.601 0.559 1.895 (0.702) -2.487 -4.038 CONSTANT -0.827 *** -0.696 -1.001 (0.281) (0.757) -1.223 N 128 128 128

Standard errors in parentheses

*** significant at 0.01; ** significant at 0.05; * significant at 0.1 OBS: dependent variable = REELECTION

Our results show that Brazilian voters do not use the national economy to decide their vote for the state level. A possible explanation is that the referendum vote requires nationalized political parties to occur. In their comparison among largest countries in the Americas, Mainwaring and Jones (2003) find that Brazil shows one of the lowest levels of party nationalization.6 Following the same authors, the only two competitive parties in the

6 For instance, according to table 2, where the authors compare party system

presidential elections, PSDB and PT, are classified among the eleven least nationalized parties in the Americas. (Jones and Mainwaring, 2003, p. 154). Apparently, the president with a good performance cannot help governors to get reelected. In fact, Ames (1994) and Samuels (2000) argue exactly the opposite, calling attention to the importance of local party organizations in the definition of national electoral competitions.

The effects of the state economy on voters’ decision on state governors’ election are not confirmed by the results either. One possible explanation for this result is that the effects of state economic outcomes may not be homogeneous in the whole country. Differences among states may interact with the independent variables of our models and produce different impacts of the economy in the electoral results. Particularly, Brazilian state governments show a large variation when it comes to their capacity to generate own revenues, and some states depend heavily on federal transfers. Following Ebeid and Rodden (2005), we interacted the state economic variables and the budgetary variable with a measure of the state capacity to generate own revenues through taxes (TRIBUT). Therefore, the first column of table 6, below, conforms the following specification:

Ln(Reelection) = β0 + β1* (Incumbent effect))ij + β2*(Coattail effect)ij + β3*(State budget)ij + β4*(State budget)ij*(Tributes)ij + β5*(Tributes)ij + β6*(Relative state income)ij + β7*(Relative state income)ij*(Tributes)ij + β8*(National income)ij + β9* (National income)ij*(Presidential party)ij + β10*(Presidential party)ij + Ɛij

As expected, INCUMBET and BUDGET remain significant at 0.01 and 0.05 respectively and with positive signals. The interaction between BUDGET and TRIBUT has a small coefficient and is significant at 0.1 only in specification VII. Income variables remain not significant in the two specifications that included them.

compared to the 0.84 showed by the US party system. (Jones and Mainwaring, 2003, p. 148)

TABLE 6.

Economic Sub-national Vote and State Autonomy from National Government VII VIII IX INCUMBENT 1.408 *** 1.897 *** 2.085 *** (0.446) (0.567) (0.631) COATTAIL -0.254 -0.659 -0.201 (0.816) (0.895) -1051 BUDGET 0.089 ** 0.085 ** 0.086 ** (0.040) (0.043) (0.043) BUDGET (*) TRIBUTE -0.001 * -0.001 -0.001 (0.001) (0.001) (0.001) TRIBUTE -0.000 0.003 0.000 (0.013) (0.014) (0.015) INCOME_RELATIVE -0.005 -0.061 (0.047) (0.057) INCOME_RELATIVE (*) TRIBUTE 0.000 0.002 (0.001) (0.001) INCOME_NATIONAL -0.015 0.012 (0.030) (0.054) INCOME_NATIONAL (*) PRES_PARTY 0.034 0.072 (0.085) (0.153) UNEMP_RELATIVE -0.924 *** -1.096 *** (0.351) (0.399) UNEMP_RELATIVE (*) TRIBUTE 0.021 *** 0.025 *** (0.007) (0.008) UNEMP_NATIONAL -0.099 -0.121 (0.113) (0.201) UNEMP_NATIONAL (*) PRES_PARTY 0.144 -0.122 (0.336) (0.583) PRES_PARTY 0.534 -0.536 1319 (0.744) (2.960) (4.561) CONSTANT -0.877 -0.388 -0.191 (0.851) (1.226) (1.724) N 128 128 128

Standard errors in parentheses

*** significant at 0.01; ** significant at 0.05; * significant at 0.1 OBS: dependent variable = REELECTION

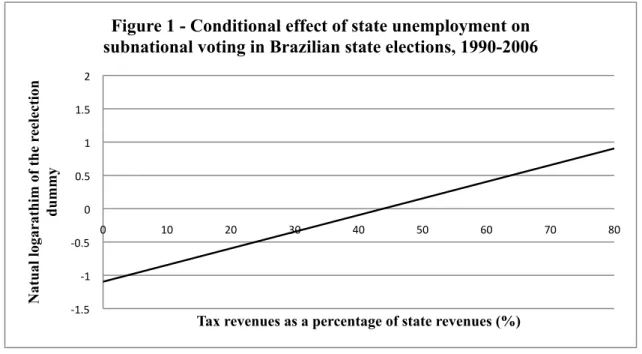

Differently from income, state unemployment has a significant impact when interacted with the tax revenues participation in the state revenues. This finding indicates that economic sub-national voting performs better in explaining state governor reelection, but its impact is not homogeneous across the country. As we can see in the FIGURE 1 below, the impact of unemployment is higher in states with less capacity to generate their revenues through local taxes (the coefficients were draw from the IX specification).

Coincidently, the impact of state unemployment is higher in the states in which the public employment represents a higher share of the total label market, such as Roraima, Amapá, and Acre. State governors can influence unemployment rates through the increase of public employment. Therefore, the economic voting approach appears to explain better the electoral fate of state governors in states in which the public employment is more representative.

As an initial test for robustness, we rerun all specifications including only observations in which either the incumbent or the incumbent’s party ran for reelection. Results from these procedures are very similar with the ones presented in this paper.

-‐1.5 -‐1 -‐0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 N atu al logar ath im of th e r ee le cti on d u mmy

Tax revenues as a percentage of state revenues (%)

Figure 1 - Conditional effect of state unemployment on subnational voting in Brazilian state elections, 1990-2006

Conclusion

Contrary to previous studies on other federations, in this paper we not find evidence that of referendum voting in the Brazil. A possible explanation for this finding is that the referendum vote approach assumes nationalized political parties, as voters should be able to identify partisan linkages between the state governor and the president. As Brazilian parties show a low degree of nationalization, the referendum vote cannot explain voters’ decision for state governor.

Instead, we find evidence that state economic and budgetary factors impact in the chances of the governors´ reelection. As Ebeid and Rodden (2005), we found that economic voting is not homogeneous among states. State unemployment reduces the changes of the

governor getting reelected in states that depends more on federal transfer due to inability of producing own revenues via taxes. Finally, we found that incumbents producing budgetary positive results are more prone to get reelected.

References

ABRAMOWITZ, Alan I.; SEGAL, Jeffrey A. (1986). Determinants of the Outcomes of U.S. Senate Elections. The Journal of Politics, Vol. 48, No. 2

AMES, Barry (1994). The Reverse Coattails Effect: Local Party Organization in the 1989 Brazilian Presidential Election. American Political Science Review, 88(1): 95-111. AMES, Barry (1995). Electoral rules, constituency pressures, and pork barrel: Bases of voting in the Brazilian congress. The Journal of Politics 57(2): 324-43.

AMES, Barry (2000) The Deadlock of Democracy in Brazil. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

ANDRADE, Regis de Castro (1998). Processo Governativo no Município e Estado. Edusp, São Paulo.

ANDERSON, Christopher J. (2000). Economic voting and political context: a comparative perspective. Electoral Studies, v. 19, pp. 151–170

ARVATE, Paulo Roberto; AVELINO, George; TAVARES, José A. (2009) Fiscal conservatism in a new democracy: Sophisticated versus naïve voters. Economic Letters, 102: 125-27.

ATKESON, Lonna Rae; PARTIN, Randall W. (1995). Economic and Referendum Voting: A Comparison of Gubernatorial and Senatorial Elections. American Political Science Review, Vol. 89, No. 1

BRAMBOR, Thomas; CLARK, William Roberts; GOLDER, Matt (2006). Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses. Political Analysis. 14:63-82.

BRENDER, Adi; DRAZEN, Allan (2005). Political Business Cycle in new versus establishes democracies. Journal of Monetarial Economics, vol. 52

CHUBB, John E. (1988). Institutions, The Economy, and the Dinamics of State Elections. American Political Science Review, vol 82 (1):133-154

EBEID, Michael; RODDEN, Jonathan (2006). Economic Geography and Economic Voting: Evidence from the US States, Britsh Journal of Political Science, vol 36 pp. 527-547

FIORINA, Morris P. (1978). Economic Retrospective Voting in American Elections: Micro-analysis. American Journal of Political Science 27:426-43.

GÉLINEAU, François (2002). Economic Voting in Volatile Contexts National and Sub-national Politics in Latin America. Phd Thesis, University of New México.

GÉLINEAU, François; BÉLANGER, Eric (2003). Economic Voting in Canadian Federal Elections. Paper presented at Canadian Political Science Association Halifax, 2003

GÉLINEAU, François; BÉLANGER, Eric (2005). Electoral Accountability in a Federal System: National and Provincial Economic Voting in Canadá. Publius, summer 2005: 407-424

GÉLINEAU, François; REMMER, Karen (2005). Political Decentralization and Electoral Accountability: The Argentine Experience, 1983–2001. British Journal of Political Science, Vol 36:133-157.

JONES, Mark; SANGUINETTI, Pablo; TOMMASI, Mariano (2000). Politics, Institutions, and Fiscal Performance in a Federal System: An Analysis of the Argentine

Provinces.Journal of Development Economics, vol 61:305-333

JONES, Mark P.; MELONI, Osvaldo; TOMMASI, Mariano (2007). Voters as Fiscal Liberals. Draft.

KIEWIET, D. Roderick. (1981). Policy Oriented Voting in Response to Economic Issues. American Political Science Review 75:448-59.

KRAMER, Gerald H (1971). Short-Term Fluctuations in U.S. Voting Behavior, 1896-1964. American Political Science Review, Vol. 65, No. 1

LEIGH; Andrew MCLEISH, Mark (2008). Are State Elections Affected by National Economy? Evidence from Australia. Draft.

LEWIS-BECK, Michael S.; PALDAM, Martin (2000). Economic voting: an introduction. Electoral Studies, vol 19: 113-121.

LOWRY, Robert C.; ALT, James E.; FERREE, Karen E.. (1998). Fiscal Policy Outcomes and Electoral Accountability in American States. American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No. 4

MAINWARING, Scott (1991). Politicians, Electoral Systems, and Parties: Brazil in Comparative Perspective. Comparative Politics 24, No. 1 (October 1991): 21-‐43

MAINWARING Scott (1995). Brazil: Weak Parties, Feckless Democracy. Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America. In: Mainwaring Scott and Timothy R. Scully, eds., Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America. Stanford, Stanford University Press.

MAINWARING, Scott (1999). Rethinking Party Systems in the Third Wave of Democratization: The Case of Brazil. Stanford, Stanford University Press.

MOURA NETO; João Silva; MARCONI, Nelson; PALOMBO, Paulo Eduardo M.; ARVATE, Paulo Roberto (2006). Vertical Transfers and the Appropriation of Resources by the Bureaucracy: the Case of Brazilian State Governments

PELTZMAN, Sam (1987). Economic Conditions and Gubernatorial Elections. The American Economic Review; May 1987; 77, 2.

PELTZMAN, Sam (1992). Voters as Fiscal Conservatives. Quaterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 107, nº2.

PIERSON, James E. (1975). Presidential Popularity and Midterm Voting at Different Electoral Levels. American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 19, No. 4

POWELL, Bingham; WHITTEN, Guy (1993). A Cross National Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking Account of the Political Context. American Journal of Political Science, vol 37 (2)

REMMER, Karen; GÉLINEAU, François (2003). Sub-national Electoral Choice:

Economic and Referendum Voting in Argentina, 1983-1999. Comparative Political Studies, vol 36 (7)

REMMER, Karen; WIBBELS, Erik (2000). The Sub-national Politics of Economic Adjustment. Comparative Politcal Studies, vol 33 (4): 419-451

RODDEN, Jonathan (2003). Federalism and Fiscal Bailouts in Brazil. In RODDEN et al. (2003). Federalism and the Challenge of Hard Budget Constraints. MIT, Estados Unidos. RODDEN, Jonathan (2004). Comparative Federalism and Descentralization; on meaning and measurments. Comparative Politics, 36(4): 481-500.

RODDEN, Jonathan; WIBBELS, Erik (2005). Retrospective Voting, Coattails, and Accountability in Regional Elections. 2005 Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

RUDOLPH, Thomas J. (2003). Institutional Context and the Assignement of Political Responsibility. The Journal of Politics, Vol. 65, No. 1

SAMUELS, David J. (2000). The Gubernatorial Coattails Effect: Federalism and Congressional Elections in Brazil. The Journal of Politics, 62(1): 240-253.

SIMON, Dennis M.; OSTROM Jr., Charles W.; MARRA, Robin F. (1991). The President, Referendum Voting, and Sub-national Elections in the US. American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, No. 4

STEIN, Robert M. (1990). Economic Voting for Governor and U. S. Senator: The Electoral Consequences of Federalism. The Journal of Politics, Vol. 52, No. 1

STEIN, Ernesto (1999). Fiscal Decentralization and Government Size in Latin America. Journal of Applied Economics, II(2): 357-91

TUFTE, Edward R. (1975). Determinants of the Outcomes of Midterm Congressional Elections. American Political Science Review, Vol. 69, No. 3