Splendor and misery of

Epidemiology for the evaluation

of health promotion

Esplendor e miséria da

Epidemiologia para avaliação da

promoção da saúde

Louise Potvin, PhD

Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada

P.O. Box 6128, Station Centre-ville Montréal, QC H3C 3J7

Canada

Louise.Potvin@UMontreal.CA

Patrick Chabot, PhD

Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada

A previous version of this paper was presented at the V Brazilian Epidemiology Congress, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. March 23-27, 2002.

Introduction

During the past 30 years, the field of pub-lic health has been under enormous pres-sure to move toward a more “social” ap-proach to health. This is true of the two fun-damental areas of the field: researching the “causes” of disease and ill health and inter-vening to improve health. In terms of re-search, social epidemiology has broadened the traditional domain of classic epidemiol-ogy to include social determinants1 in

stud-ies looking at what causes unhealthy socie-ties2.

Given the realm of public health inter-vention, the Ottawa Charter3 and health

pro-motion were created with the specific goal of changing the way health professionals and decision makers think about health and “to transform the complex knowledge of social epidemiology into practice and at the same time be able to document an effect”4.

De-spite the growing support from research agencies and health decision makers*, both

social epidemiology and health promotion still struggle to put into practice their social and population perspectives on health. Both have yet to achieve their transformation from classical epidemiology for one, and disease prevention for the other, both being based on individualistic models of health and pub-lic health intervention. Social epidemiology has yet to demonstrate that unpacking the social determinants of health leads to a bet-ter understanding of health and health pro-motion. It also faces the need to demonstrate whether and how it improves health.

Underlying this paper is the proposition that the challenges facing both social epide-miology and health promotion are closely linked. Both areas are experiencing difficul-ties in developing a satisfying conception of the social aspects of health. Although social

* In Canada, the newly created Canadian Institute of Health Research’s mission recognizes the “social and cultural factors that affect the health of population” as one of the four pillars on which health research is founded5. In addition, the

epidemiology proposes innovative concep-tualizations of health and disease7,8,

causal-ity9 and social categories as fundamental

causes of disease10, most studies make use

of these social categories as just another layer of risk factors in predictive models11. There

is little discussion on whether these catego-ries are of the same nature as the risk factors that are usually produced by classical epide-miological studies12.

Similarly, in the realm of public health intervention, from disease prevention to health education, and to health promotion, approaches to improving population health have evolved as well as our conception of health and disease13. Although some “avant

garde” practices in health promotion are leading the way into radically new concep-tions of health and public health interven-tions, these practices still lack proper tools to reflect on their process14 and produce the

much awaited positive results that will legiti-mate public spending15.

In this paper, we propose that a careful examination of the barriers encountered by health promotion to complete its transfor-mation away from disease prevention also provides insights that will help social epide-miology achieve its own transformation away from classical epidemiology. In so do-ing we identify two epistemological blind spots that are common to health promotion and to social epidemiology. These two blind spots are reflexivity and historicity, two no-tions that contemporary social theory has developed extensively to further our under-standing of the complex relationship be-tween human practices and the social struc-ture. The former pertains to the absence of an absolute determinism between the social structure and human practices given the human capacity to reflect on its own experi-ence with abstract categories, thus creating agency and capacity to transform the struc-ture. The latter refers to the conception that at any time, the state of an object (program, health status or other) cannot be isolated from the contexts that give it meaning: its previous states and its transformation.

In addition to their relevance for an

ap-propriate evaluation of health promotion, these two notions could help debug some of the issues in the study of health and place11.

Our hope is that by achieving its own trans-formation from classical epidemiology, so-cial epidemiology will contribute to freeing the evaluation of health promotion from the models that were designed to evaluate dis-ease prevention and health education inter-ventions.

The parallel evolutions of public

health etiological models and

intervention approaches

We propose that like any organized hu-man practice, the field of public health can be modeled by its ontological, epistemological and practical dimensions. Those correspond respectively to: the nature of the object of practice; the type of knowledge practition-ers can gain regarding this object; and prac-titioners’ actions, when their action is un-derstood as a dialectical relation between theory and the empirical world (practice). In public health, the ontological dimension is represented by the object that researchers try to understand and professionals try to modify. The epistemological dimension is denoted by the knowledge paradigm that al-lows a better understanding of the object. The practical dimension comprises the ap-proaches to the intervention that are imple-mented to act upon the object.

In their view of the evolution of epide-miology, Susser and Susser16,17 suggest that

the field is undergoing a third revolution. They identify three past eras:

• sanitary statistics marked by the miasma theory;

• infectious disease marked by the germ theory;

• chronic disease epidemiology marked by a black box model of relating exposure to outcomes16.

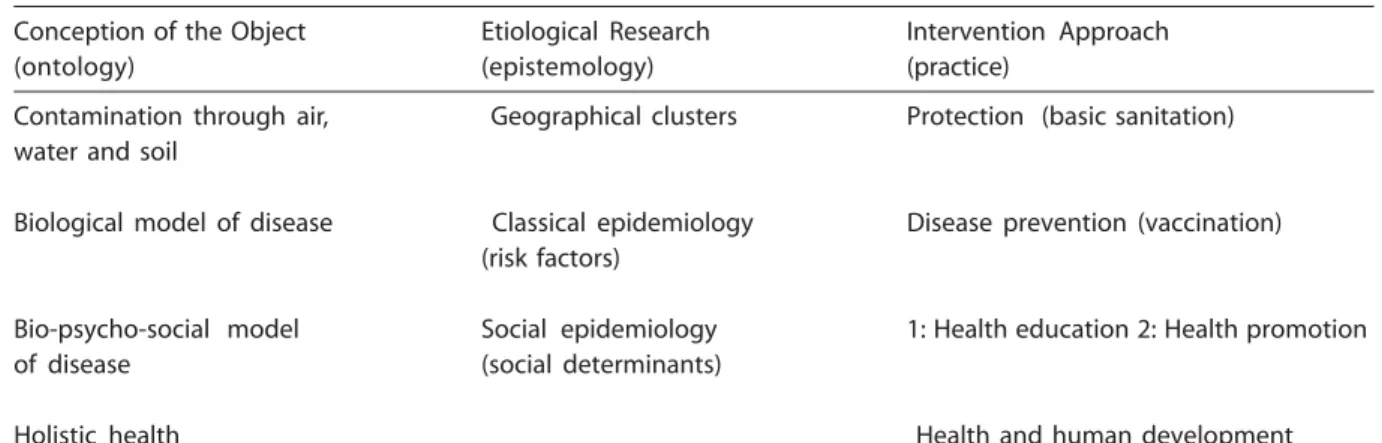

follow-ing the evolution of its contents along these dimensions, as in Table 1.

According to Rosen18, in its original

con-ception and until the hygienist movement, disease was a natural phenomenon arising from water, air and soil. It can be described through clusters of cases and acted upon by protective measures that insulate humans from contaminating sources. The elabora-tion of the statistical theory in the 18-19th centuries led to the development of vital sta-tistics as a means to keep track of these clus-ters19. With the widespread acceptance of the

germ theory, the object of public health be-came the bio-medical model of disease, in which a chain of causation progresses from infectious agents to diseases. Epidemiology was developed as the research paradigm with key concepts being exposure and risk factor. Intervention approaches adopted prevention strategies that aimed at interrupt-ing this transmission chain.

The third and current era marked by chronic diseases can be divided into an early and late period. Still keeping individual bio-logical processes at the heart of the defini-tion of diseases, the conceptualizadefini-tion of dis-ease in this bio-psycho-social model adds layers of individual and social factors. The early version is centered most exclusively on “intra” personal determinants of health behaviors, whereas the later version takes into account social factors that may support or impede these behaviors. Corresponding

to the restricted model of the early period, classical epidemiology has expanded its con-ception of causality to include multiple causes and its notion of risk factor to en-compass social categories. It remained, how-ever, mostly centered on individual risk fac-tors. In the early version, health education was added to disease prevention as an inter-vention approach. Recently, more emphasis was placed on the “distal” social environ-ments that are not “directly” in contact with individual biological processes. The push to discover how social determinants impact on the health of the general population rather than on individuals, led to a distinct devel-opment now called social epidemiology20. At

the same time attempts to design interven-tions to address those social and other non-individual risk factors and conditions con-ducted to the development of health pro-motion21.

From our understanding of this evolu-tionary process, health promotion as an ap-proach to intervention has encountered many of the limitations of the bio-psycho-social model of disease. Its actual form rep-resents a transition towards a more socially integrated approach that will more closely correspond to a holistic model of health. In-deed, several new and exciting initiatives, such the programs developed by the Aca-demic Health Centre of the Fiocruz Foun-dation to address health, poverty and hu-man development issues in the surrounding

Table 1 - Parallel evolution of the ontological, epistemological and practical dimensions of public health

Conception of the Object Etiological Research Intervention Approach

(ontology) (epistemology) (practice)

Contamination through air, Geographical clusters Protection (basic sanitation) water and soil

Biological model of disease Classical epidemiology Disease prevention (vaccination) (risk factors)

Bio-psycho-social model Social epidemiology 1: Health education 2: Health promotion

of disease (social determinants)

favela of Manguinhos22. These initiatives are

pushing for the development of a new conceptualization of the object of public health and of a more socially integrated ver-sion of health promotion.

Throughout the rest of this paper, we will show that although health promotion has already ventured into a novel model of, and a new object for public health, it is still strug-gling to break away from the bio-psycho-social model of disease. We will also exam-ine how taking into account the reflexivity and historicity of human action and public health interventions provides insight for un-packing the social aspects of health.

Health promotion and social

epidemiology as innovative

approaches in public health

Following the publication of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion3, profound

transformations marked the domain of pub-lic health intervention. Abandoning interven-tion models that were based on psycho-so-cial theories of behavior, and proposed standardized, “ready to use” educational ac-tivities aimed at shaping behaviors, public health practitioners have explored new and multiple forms of interventions. These new types of interventions are more or less ex-plicitly based on a set of values among which empowerment and citizen participation are most often quoted23. The variety of forms of

health promotion intervention can be rep-resented on a continuum with health educa-tion at one end and health promoeduca-tion at the other.

Programs that target specific health behaviors in a determined group of at-risk individuals with pre-packaged standardized activities are more typical of health educa-tion. The effects of such interventions tend to level off. They cannot be distinguished from that of secular trends after early adopters operated the changes24. As a result,

the most vulnerable sections of the popula-tion are often outside the reach of these in-terventions25. In addition, these interventions

do not prevent the influx of people who

be-come at-risk26, which is why authors have

proposed to broaden the traditional targets for public health interventions to include socio-environmental conditions that enable or impede these behaviors13. At the other

end of the continuum are those multi-facto-rial and multi-sector health promotion pro-grams based on citizen participation that tar-get capacity-building so people can trans-form those conditions that improve their health.

This evolution that led to the adoption of health promotion models for public health interventions also induced a focus on “com-munity” or more rightly so, on “local envi-ronments” as strategic settings for interven-tions13. This “New Public Health” not only

suggests that interventions should aim at making health resources locally available for citizens so healthy choices are made avail-able and valued, but also that such interven-tions should contribute to local capacity-building. Finally, these interventions should be based on the creation of new alliances for health. This means that existing social net-works should be redesigned so local actors who are not traditionally associated with health will be part of health-related coali-tions27. Two novel approaches to public

health intervention are exemplary of these principles: the ecological model28 and the

community development model29. Despite

their novelty and the integration of the so-cial and health that these approaches repre-sent, their full implementation into practice is slowed down by our conceptions of how health is socially produced. These concep-tions seldom take into account the reflexiv-ity and historicreflexiv-ity that characterize the rela-tionship between healthy human develop-ment and social structures.

Reflexivity and the ecological approach Reflexivity and the ecological approach Reflexivity and the ecological approach Reflexivity and the ecological approach Reflexivity and the ecological approach to intervention: Who has seen the agent? to intervention: Who has seen the agent? to intervention: Who has seen the agent? to intervention: Who has seen the agent? to intervention: Who has seen the agent?

The ecological approach to interven-tion28 made immense progress in public

of Medicine30. The thrust of this approach is

to focus health interventions on the individu-al’s ecosystem. Based on a systemic view of health, the ecological approach conceives of the individual as the center circle in a series of inclusive circles, each one representing an aggregation level within the environment. All the outer layers around the individual at the center form the individual’s ecosystem31.

Characteristics at a given aggregation level constrain those at all the lower levels. For example, an individual’s eating habits are determined by the food available in the fam-ily. This availability itself depends on what is on the shelves of accessible food outlets, which itself is determined by a series of poli-cies, rules, and taxation systems that are en-acted at the municipal and higher levels.

From the point of view of this ecological approach, public health intervention plays a dual role. While the intervention aims at transforming the resources and character-istics found at the higher levels of aggrega-tion, it also develops educational activities to convince people to adopt new lifestyles and behaviors13,31. Within such an approach,

en-vironmental actions are instrumental to behavioral changes.

Despite the inclusion of the social envi-ronment, the ecological model is essentially “neo behavioral”. Indeed, in this model, the individual and the modification of his or her risk factors and lifestyle constitute the prin-cipal foci of the intervention. At the end of the day, it is the modification of these behaviors and risk factors that will be used as criteria to evaluate the interventions. For evaluation purposes, when the timeframe or resources do not allow for the use of behavioral criteria, a causal chain of envi-ronmental characteristics that determine health behaviors, risk factors, and disease is constructed. The role of evaluation consists of showing that the causal environmental characteristics were changed by the inter-vention. The inference is that if the causal chain is broken at any point, the negative outcome will not materialize32,33.

The ecological approach is founded on a deterministic model of the relationship

be-tween social conditions and human action and behavior. This model is characterized by the absence of “agency” in the individual at the center of the model, “agency” being the capacity to exercise freedom and to in-duce change in the structure. This model is more consistent with the Durkheimian con-cept of the role of the social structure than with contemporary social theory. Unfortu-nately, in health promotion as in social epi-demiology, when sociology is called upon to explain how social determinants are linked to health, it is most often Durkheim’s and the structuralist school’s ideas of the early 1900s that are borrowed and adapted34.

Current sociology is essentially based on a critique of such thinking that conceives human action as a reaction to an external social structure that surrounds the indi-vidual. For neo-structuralist sociologists, the social structure is located both within and around individuals whose reflexive action (practice) transforms and reproduces the structure. This internalization of society within the individual’s own frame of refer-ence through socialization provides clues to explain how human action both reproduces and transforms the social structure. Sociolo-gists such as Touraine35, Bourdieu36 or

Giddens37 have used the concept of agency

to take into account this reflexive relation-ship between human action and the social structure. While the structure provides gen-eral constraints and opportunity for action, the particular activation of these constraints and opportunities, in turn, reproduces and/ or transforms the structure.

groups. The experimental group was exposed to clinical preventive services and the con-trol group was assigned to usual care.

Although early results have shown a sig-nificant decrease of tobacco consumption in the experimental group38, the 16-year

follow-up results showed that lung cancer mortality tended to be higher in the experimental group as contrasted with the control group39. There

are indeed multiple plausible hypotheses to explain such a finding. It is possible that mem-bers of the control group stopped smoking at a later stage, or those of the experimental group who had stopped during the preven-tion intervenpreven-tion resumed smoking later. It is equally possible that neither explanation is true. In any case, these results illustrate that interventions on simple causal chains do not produce results that are simple to interpret. Such difficulties are more likely to arise when causal chains and intervention models do not provide room for the reflexivity of the hu-man agent and the reciprocal relationship with the social structure.

Historicity in community development: Historicity in community development: Historicity in community development: Historicity in community development: Historicity in community development: When does a program start?

When does a program start? When does a program start? When does a program start? When does a program start?

Another major innovation of health pro-motion is the integration of community de-velopment approaches that make deliberate attempts to transform existing social networks within local environments. Important con-cepts such as empowerment and citizen par-ticipation imply a change in the existing rela-tionships between social agents (individuals or organizations) that share common space. Whether the goal is to increase social capital and social cohesion, or to enhance commu-nity empowerment, the means to achieve the goal is through the reconfiguration of existing social networks by creating and supporting a local forum for citizens and non health or-ganizations to discuss and act upon the con-ditions that shape their health29,40.

An advanced illustration of the forum is the community coalition for health41. These

coalitions are new organizations according to the definition provided by the French soci-ologists Michel Crozier and Erhart

Friedberg42. For Crozier and Friedberg,

or-ganizations are ensembles of operations per-formed in a coordinated manner in order to achieve objectives. This description includes loosely formalized groups such as coalitions. The formation of, and support given to, local coalitions which make concrete new partner-ships between local agents are characteristics that distinguish community development programs from social planning, the latter be-ing mostly associated with health education40.

Another important characteristic of these coalitions is the congregation of social agents not traditionally related to health, around health issues. Typically, coalitions are formed by representatives of non-governmental as-sociations, private sectors, public institutions from other sectors (for example, economic development, education), and by concerned citizens. Therefore, as an intervention strat-egy, coalition building is equivalent to creat-ing a new organization.

meeting of its own dynamism with that of the other organizations.

Thus, the evolution of a coalition cannot be planned in a strict sense for two reasons. First, even if deliberate actions by health or-ganizations could induce the meeting of sev-eral local agents as a prelude to the creation of a local coalition, the functioning, achieve-ments, and future of such a coalition cannot be subsumed by the actual circumstances and conditions in which it was created. The “pre-existing” (organizational) relationships between the coalition members, before the official creation of the coalition, also shape the coalition’s present and future. In addi-tion, refocusing on health issues regarding the relationships within the coalition, to-gether with the development of inter-organi-zational relations must be taken into account to understand coalition evolution. Thus, coa-litions are never “created” entirely de novo. Their life does not start with an external in-tervention although such inin-terventions are often the trigger of the re-organization of local networks.

Second, their capacity to project them-selves into the future, taking into account their past history and their capacity to act accord-ing to these projections, prevents a strictly deterministic, external orientation of a coali-tion. At any given time, the state of a coalition results from the convergence of its past and its projection in the future. Coalitions are re-organizations of the local action structure with the aim of reframing the meaningful re-lationships between existing social agents with reference to their past and future.

This self-referential dynamic process, like in any human organization, reproduces and generates history understood as the devel-opmental process of human time and space dimensions. Like any biography, the history of an organization is made of the events that marked both the internal processes of its evolution and its relations with other organi-zations. The elaboration of such a history, however, proceeds with a double construc-tion. First, events cannot be neutrally objectified, they must be constructed from the perceived meaningful ruptures in the

usual flow of time. Deciding, for example, that the first meeting of a coalition is an event because it marked the agreement on the mandate by all members and the function-ing of the coalition, while decidfunction-ing that the 10th meeting was not eventful because noth-ing important happened, depends on the perspective of the historian. Second, the meaning of a chain of events with regards to the evolution of the coalition is also con-structed into a coherent narrative that pro-vides a basis with which to explore the range of possible continuities and/or transforma-tions that lay ahead of the coalition.

This self-referential evolution of social systems created and supported by health pro-motion questions our usual conception of programs. One cannot conceptualize pro-grams uniquely with regards to their struc-tural dimensions and define evaluation as es-tablishing relationships between elements of that structure43 without taking into account

the transformation of these structures through time. Documenting the events that marked the evolution of this relational sys-tem and constructing a coherent narrative to interpret the system’s dynamism is as crucial for understanding health promotion interven-tion, as is the “evidence” about its efficacy.

With these two innovative practices, the ecological and the community development approaches, we illustrated that the evalua-tion and study of health promoevalua-tion programs must first take into account and then inter-pret the continuities/transformations of the program/environment system into their socio-spatial (as in society) and socio-tem-poral (as in history) perspectives. We will now demonstrate that social epidemiology is also struggling to make sense of these contextual and temporal dimensions of social transfor-mation and has yet to integrate reflexivity and historicity into its model.

Social epidemiology and the

bio-psycho-social model of disease

of health that increasingly borrows concepts and knowledge from social sciences. Since the publication of the Black Report44, the

is-sue of health inequalities has triggered a whole research program. This study showed the existence of a relationship between health status and the position in the social hierarchy. This relationship is monotonous ascendant, meaning that those at the pinna-cle of the social ladder are in better health than those immediately following them, who are themselves healthier than those just un-derneath, and so on until the most impover-ished people.

Health is not evenly distributed within a population. Inequalities are identifiable as a function of socially constructed categories such as socio-economic status, gender and ethnic groups. Health inequalities appear to be by-products of specific organizations of life and social relations45. This field of inquiry

that blends social categories together with biological outcomes, proved very fruitful to rejuvenate epidemiological research. Stud-ies in social epidemiology have burgeoned in a multitude of directions as illustrated by the wide range of subjects elaborated in the first textbook of social epidemiology, pub-lished in 20001. Health has become a social

concern46 and public health a social science47.

Health and place: Places or islands? Health and place: Places or islands? Health and place: Places or islands? Health and place: Places or islands? Health and place: Places or islands?

An area of investigation that triggers a growing interest for researchers in social epidemiology is the aggregation of health outcomes in neighborhoods or communi-ties48,49, over and above the level expected

given that similar individuals, with similar risk factors often share the same geographical space. Contextual effects50 result from the

attribution of the geographical aggregation of health outcomes to contextual or ecologi-cal characteristics of the environment51.

Thus, places or local environments can be characterized by attributes that transcend the aggregation of individual characteristics. Sally Mcintyre has coined the term “oppor-tunity structure” referring to those contex-tual characteristics that promote or impede

health52. Three groups of attributes form the

opportunity structure.

The first group is made of the character-istics of the physical environment such as climate, quality of water and food supplies, and others. The relationship between this group of characteristics and health has been known for a long time. Indeed, action on these physical characteristics forms the tra-ditional axis of intervention for public health53.

The second group is made of the local configuration of resources that promote or impede health. In addition to health care services, recent work in community health has identified a variety of resources that are associated with health54. Quality of housing,

access to recreational equipment and parks as well as restriction of youth access to to-bacco products are all examples of health promoting resources that facilitate “healthy choices”55. Our studies in particular showed

that local configuration of resources for youth tobacco smoking is associated with compo-sitional characteristics of places56 and to the

initiation of youths smoking57.

The third group of ecological character-istics pertains to the local organization of social life, to the local patterns of relation-ships between social actors and to the way social resources such as power and status are distributed; in brief, the social fabric. Recent literature abounds with studies that show ecological correlations between vari-ables such as social capital, social cohesion, community participation58 as well as many

forms of discrimination59 with health

out-comes. Most of these studies however, treat local environments as if they were discon-nected from society and from the global so-cial process.

The social structure understood as the rules and resources mobilized for the repro-duction/transformation of social action37 is

also associated with population health as shown by international comparisons46,60. For

places individuals at the center of an ensem-ble of inclusive circles and that is present both in social epidemiology62 and health

pro-motion63 reflects a truncated vision of what

“social” means. In this model social is always located outside the individual and causality always goes from superior to lower levels of aggregation.

Epidemiological models of disease cau-sation and health production do not make room for reciprocal or recursive actions be-tween the elements in the causal chains. More to the point, the fundamental epide-miological notion of “exposure” suggests a passive object that reacts to environmental conditions instead of an agent whose reflex-ive, recursive actions transform the struc-ture to which he/she belongs. Such reflexiv-ity cannot be dismissed when examining the social processes involved in the shaping of the health of populations.

Another problematic corollary of this lay-ered model of health production is the ab-sence of a historical perspective essential to understand social transformations. In these models, the structure is given, and the trans-formation dynamics by which it is continu-ously reproduced or transformed are absent. All studies addressing health and place is-sues are cross sectional, whereas contem-porary models of urban development show that the notions of space, population and time intertwine and cannot be understood inde-pendently64,65.Thus, the opportunity

struc-ture observable at a given time in a given place is not only a function of the social struc-ture but also of its history or more precisely of its historical structuring process. Taking into account the history embedded in the narratives that provide meaning to transfor-mations or continuities of human action seems indispensable to understand how the social affects health.

Conclusion

Our observation of social epidemiology through the lens of health promotion leads to the identification of two major blind spots in

public health intervention and research. Re-flexivity and historicity are two notions that need to be developed and integrated into our health models and public health interventions and evaluations, in order for health promo-tion to reflect on its acpromo-tion with relevant con-ceptual categories and for social epidemiol-ogy to unpack the relationships between so-ciety and health. It is also important that these developments occur in parallel.

Epidemiology has traditionally formed the methodological foundation for the evalu-ation of public health interventions66. The

difficulties encountered by evaluation re-searchers to elaborate relevant empirical arguments about the effects of cutting-edge health promotion projects67 may partly lie in

the limitations of the methods used, espe-cially considering their limited capacity to capture the social processes triggered and/ or modified by those interventions. Classical epidemiology has proven its strength for understanding how behaviors become risk factors involved in diseases. It is thus the methodology of choice for evaluating the behavioral outcomes of health education interventions. Social processes, however, are not of the same nature as at-risk behaviors. They only acquire and produce meaning in relation with their spatial and temporal con-text. It is this network of social relationships that needs to be captured by the evaluation of health promotion thus evading the realm of classical epidemiology.

Acknowledgements

Production of this paper was made pos-sible thanks to funding from the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and the Canadian Institute of Health Research to L. Potvin (Chair Community Approaches and Health Inequalities) and from the Quebec Council for Social Sciences to P. Chabot.

Au-thors’ participation in the 2002 Abrasco Con-ference was made possible through a Cana-dian International Development Agency grant to the Canadian Public Health Association. Editorial assistance was provided by Hoori Hamboyan. Finally, the authors thank Katherine L. Frohlich, Sylvie Gendron, and Pascale Lehoux for their comments on a pre-vious draft.

References

1. Berkman LF, Kawachi I (eds.). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

2. Kawachi I. Social epidemiology (Editorial). Soc Sci Med 2002; 54: 1739-1741.

3. WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Health Promot 1986; 1: iii-v.

4. Kickbush I. Introduction: Tell me a story. In: Pederson A, O’Neill M, Rootman I. (eds.). Health promotion in Canada. Provincial, national, and international perspectives. Toronto: W.B. Saunders; 1994. p. 8-17.

5. CIHR Backgrounder - Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Retrieved June 9, 2002, from http:// www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/about_cihr/overview/

who_we_are_e.shtml. (n.d.)

6. Federal, Provincial, Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health. Strategies for population health. Investing in the health of Canadians. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services of Canada, Cat. No. H39-316/ 1994; 1994.

7. McKinlay JB, Marceau LD. A tale of three tails. Am J Public Health 1999; 89: 295-298.

8. McKinlay JB, Marceau LD. (2000). To boldly go… Am J Public Health 2000; 90: 25-33.

9. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: Has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med 1995; 39: 887-903.

10. Link B, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav, (Extra issue) 1995, 80-94.

11. Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: How can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them. Soc Sci Med 2002; 55: 125-39.

12. Potvin L, Frohlich KL. L’utilité de la notion de genre pour comprendre les inégalités de santé. Ruptures, revue transdisciplinaire en santé 1998; 5: 142-52.

13. Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion planning.

An educational and ecological approach (3rd ed.).

Mountain View: Mayfield; 1999.

14. McQueen DV, Anderson L. What counts as evidence: Issues and debates. In: Rootman I et al. (eds.). Health promotion evaluation. Principles and perspectives. Copenhague: Who Regional Publicatios. European Series, No 92; 2001; p. 63-81.

15. International Union for Health Promotion and Education. The evidence of health promotion effectiveness. Shaping public health in a new Europe

(2nd ed.). Brussel: European Comission; 2000.

16. Susser M, Susser E. Choosing a future for epidemiology : I. Eras and paradigms. Am J Public Health 1996; 86: 668-73.

17. Susser M, Susser E. Choosing a future for

epidemiology : I. From black box to Chinese boxes and eco-epidemiology. Am J Public Health 1996; 86: 674-7.

18. Rosen G. A history of public health (expanded edition), Baltimore: The Johns Hopkin University Press; 1993.

19. Hamlin, C. Could you starve to death in England in 1839? The Chadwick-Farr controversy and the loss of the “social” in public health. Am J Public Health, 1995;85: 856-866.

20. Syme SL, Frohlich KL. The contribution of social epidemiology: Ten new books. Epidemiol 2001; 13: 110-112.

21. Green LW. Canadian heath promotion: An outsider’s view from the inside. In: Pederson A, O’Neill M, Rootman I (eds.). Health promotion in Canada. Provincial, national & international perspectives. Toronto: W. B. Saunders; 1994. p. 314-26.

23. Rootman I., Goodstadt M., Potvin L., Springett J. A framework for health promotion evaluation. In: Rootman I et al. (eds.). Health promotion evaluation. Principles and perspectives (pp. 7-38). Copenhague: Who Regional Publicatios. European Series, No 92; 2001, p. 7-38.

24. Green LW, Richard L. The need to combine health education and health promotion: The case of cardiovascular disease prevention. J Health Promot Educ 1994; 1: 11-7.

25. Davis SK, Winkleby MA, Farquhar JW. Increasing disparity in knowledge of cardiovascular disease risk factors and risk-reduction strategies by socioeconomic status: implications for policymakers. Am J Prev Med 1995; 11:318-23.

26. Syme SL. The social environment and health. Deadalus 1974; (Fall): 79-86.

27. Ashton J, Seymour. The new public health. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1989.

28. Green LW, Richard L, Potvin L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. Am J Health Promot 1996; 10: 270-81.

29. Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving healththrough community organization and community building: A health education perspective. In: Minkler M. (ed.). Community organizing and community building for health. New Brinswick: Routledge; 2001. p. 30-52.

30. Smedley BD, Syme SL. (eds.). Promoting Health. Intervention strategies from social to behavioural research. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine; 2000.

31. Richard L et al. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot 1996; 10: 318-28.

32. Nutbeam D. Achieving population health goals: perspectives on measurement and implementation from Australia. Can J Public Health 1999; 90(Suppl 1): S43-S46.

33. Nutbeam D, Smith C, Catford J. Evaluation in health education. A review of progress, possibilities and problems. J Epidemiol Community Health 1990; 44: 83-89.

34. Berkman LF, Kawachi I. A historical framework for social epidemiology. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I (eds.). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 3-12.

35. Touraine A. Le retour de l’acteur. Paris: Fayard; 1974.

36. Bourdieu P. Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique. Paris: Seuil; 1972.

37. Giddens A. The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press; e Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1984.

38. Neaton JD et al. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). VII. A comparison of risk factor changes between the two study groups. Prev Med 1981; 10: 519-43.

39. Shaten BJ et al. Lung cancer mortality after 16 years in MRFIT participants in intervention and usual-care groups. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Ann Epidemiol 1997; 7: 125-36.

40. Boutiller M, Cleverly S, Labonte R. Community as a setting for health promotion. In: Poland B, Rootman I, Green LW (eds.). Settings for health promotion. Linking theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. p. 250-79.

41. Butterfoss FD, Goodman RM, Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ Res 1993; 8: 315-20.

42. Crozier M, Friedberg E. L’acteur et le système. Paris : Éditions du Seuil; 1977.

43. Potvin L, Haddad S, Frohlich KL. Beyond process and outcome evaluation: A comprehensive approach for evaluating health promotion. In: Rootman I et al.

(eds.). Health promotion evaluation. Principles and

perspectives. Copenhague: Who Regional Publicatios. European Series, No 92; 2001. p. 45-62.

44. Townsend P, Davidson N. The Black Report. London: Pelican Books; 1982.

45. Kaplan G. Economic policy is health policy: Findings from the study of income, socio-economic status, and health. In: Auerbach A., Krimgold, BK (eds.). Income, socioeconomic status, and health. Exploring the relationships. Washington, DC: National Policy Association; 2001. p. 137-49.

46. Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy societies. The affliction of inequalities. London: Routledge; 1996.

47. Terris M. The changing relationships of epidemiology and society: The Robert Cruickshank Lecture. J Public Health Policy 2001; 22: 441-463.

48. Diez Roux AV et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 99-106.

49. Macintyre S, MacIver S, Sooman A. Area, class and health: Should we be focusing on places or people? J Soc Policy 1993; 22: 213-234.

50. Shouls S, Congdon P, Curtis S. Modelling inequality in reported long term illness in the UK: Combining individual and area characteristics. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996; 50: 366-76.

52. Macintyre S, Ellaway A. Ecological approaches: Rediscovering the role of the physical and social environment. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. (eds.). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000, p. 332-48.

53. Draper P. (ed.). Health through public policy. The greening of public health. London UK: Green Print; 1991.

54. Green LW, Ottoson JM. Community health (7th ed.). Chicago: Mosby, 1994.

55. Millio N. Making healthy public policy; developing the science by learning the art: An ecological framework for policy studies. In: Badura B, Kickbush I. (eds.). Health promotion research: Towards a new social

epidemiology. Copenhagen: WHO European series Vol 32; 1991. p. 7-28.

56. Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Chabot P, Corin H. A theoretical and empirical analysis of context: Neighbourhoods, smoking and youth. Soc Sci Med 2002; 54: 1401-17.

57. Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Gauvin L, Chabot P. Youth smoking initiation: disentangling contextual from compositional effects. Health & Place 2002; 8: 155-66.

58. Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. (eds.). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 174-90.

59. Krieger N. Discrimination and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. (eds.). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 36-75.

60. Navarro V, Shi L. The political context of social inequalities and health. Soc Sci Med 2001; 52: 481-91.

61. Curtis S, Jones IR. Is there a place for geography in the analysis of health inequalities. Sociology of Health and Illness 1998; 20(5)

: 645-72.

62. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity and health. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation; 1992.

63. Hancock T, Perkins F. The mandala of health: A conceptual model and teaching tool. Health Educ 1985; 24(1): 8-10.

64. Castells M. The informational city. Information technology, economic restructuring, and the urban-regional process. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1989.

65. Soja EW. Postmetropolis. Critical studies of cities and regions. Oxford: Blackwell; 2000.

66. Tannahill A. Epidemiology and health promotion. A common understanding. In: Bunton R, Macdonald G.

(eds.). Health promotion. Discipline and diversity.

London: Routledge; 1992. p. 86-107.