2019/2020

José Pedro Teixeira de Sousa de Sá Pinto

Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms:

A Review of Current Standards of Care

Abordagem das Neoplasias Neuroendócrinas Gastroenteropancreáticas:

Uma Revisão das Recomendações Atuais

Mestrado Integrado em Medicina

Área: Ciências Médicas e da Saúde – Medicina Clínica

Tipologia: Artigo de revisão

Trabalho efetuado sob a Orientação de:

Professor Doutor Mário Dinis Ribeiro

E sob a Coorientação de:

Doutor Diogo Libânio

Trabalho organizado de acordo com as normas da revista:

Acta Médica Portuguesa

José Pedro Teixeira de Sousa de Sá Pinto

Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms:

A Review of Current Standards of Care

Abordagem das Neoplasias Neuroendócrinas Gastroenteropancreáticas:

Uma Revisão das Recomendações Atuais

Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Review of

Current Standards of Care

Abordagem das Neoplasias Neuroendócrinas Gastroenteropancreáticas: Uma

Revisão das Recomendações Atuais

José Pedro Pintoa, Diogo Libânio M.D. PhDb, Mário Dinis Ribeiro M.D. PhDa,b

a Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto (FMUP); b Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto - Francisco Gentil (IPO-Porto)

Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Review of

Current Standards of Care

Abstract

Until recently, the management of neuroendocrine tumors was based mainly on expert opinion and on evidence obtained from small, single center, retrospective series with heterogenous groups of tumors. To overcome these limitations, several multicenter, and often multinational, societies were established for the purpose of pooling patients, resources and expertise and to develop evidence-based clinical guidelines. However, upon review of existing guidelines, discrepant nomenclatures, conflicting staging and grading systems, multiple diagnostic studies and disagreeing treatment recommendations complicate a clear-cut approach for clinical practice. Furthermore, recent advances in the fields of functional imaging, targeted molecular therapy and minimally invasive endoscopic resection and surgery have significantly changed the standards of care for neuroendocrine tumors.

The purpose of this literature review is to summarize and compare the existing standards of care in the field of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Abordagem das Neoplasias Neuroendócrinas Gastroenteropancreáticas: Uma

Revisão das Recomendações Atuais

Resumo

Até há pouco tempo, a abordagem dos tumores neuroendócrinos era baseada essencialmente em opiniões de peritos ou em séries pequenas, retrospectivas e com um grupo heterogéneo de tumores. Para ultrapassar esta lacuna, constituíram-se vários grupos multicêntricos e supranacionais que desenvolveram guias de orientação clínica. No entanto, na análise das diferentes recomendações constatam-se diversas nomenclaturas, sistemas de estadiamento, métodos de diagnóstico e tratamento, tornando difícil uma transposição clara para a prática clínica. Além disso, avanços técnicos imagiológicos, a definição de alvos moleculares terapêuticos, o aparecimento de novos fármacos e a redefinição do papel da cirurgia e procedimentos endoscópicos minimamente invasivos estão a alterar significativamente a abordagem destes tumores.

O objetivo deste trabalho é fazer uma revisão da literatura relativa à abordagem clínica dos tumores neuroendócrinos gastroenteropancreáticos.

1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are epithelial malignancies, with a predominant neuroendocrine differentiation, that arise from cells in endocrine organs or in the diffuse endocrine system. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) are the largest subset of these tumors, representing 65% of all NENs, and develop from pancreatic islet cells or isolated endocrine cells dispersed throughout the gastrointestinal mucosa1. Although

GEP-NENs are rare, representing only 0.5% of all malignancies, there has been a large increase in incidence from <0.5/100.000 person-years in 1973 to 4.7/100,000 person-years in 20121-3.

Given that the incidence of localized and regional disease has increased disproportionately to that of advanced/metastatic disease, this increase in incidence is largely believed to be due to the expanding indications and greater availability of radiological and endoscopic imaging techniques4. Perhaps due to this greater awareness of GEP-NENs, a large body of literature has

emerged over the last few years. New tumor, node and metastasis (TNM) classification and staging systems have been proposed2,5-7, refinements to the World Health Organization (WHO)

grading system have been introduced8,9, new techniques for somatostatin receptor-based

functional imaging have been developed and validated10 and several new clinical guidelines have

been proposed11-37. However, it is important to bear in mind that, due to the paucity of

prospective studies, most of these recommendations are based on expert opinion or on small, single center, retrospective series.

This article will provide an overview of the management of patients with GEP-NENs. Please consult the appended monograph for site-specific recommendations and an in-depth evidence review.

2. Clinical Presentation

GEP-NENs typically present in patients 55-75 years old3. Although historical data

suggested women were more frequently affected, the most recent data has shown a slight male preponderance when incidence is age-adjusted1. Patients of Asian or Black descent have a

remarkably higher incidence of GEP-NENs than White patients1,3. Regardless of race or gender,

the small intestinal is the most frequent site for GEP-NENs (40%)1. The appendix and rectum are

the next most common sites (20-25% each), followed by the stomach and colon (5% each)1.

Pancreatic NENs only make up about 1% of all GEP-NENs1.

Overall, GEP-NENs are indolent tumors that can be divided into functioning and non-functioning tumors, depending on whether they produce and secrete enough metabolically active hormones to produce clinical signs and symptoms11,30. Most tumors are non-functioning

especially in early stages11,30,31. Given their associated non-specific abdominal symptoms, some

of these patients may be misdiagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome31. As tumors grow and

metastasize, more pronounced and localizing symptomatology such as an abdominal mass, gastrointestinal bleeding, malabsorption, intestinal obstruction or post-prandial ischemia may arise11,18,31. Due to these non-specific findings, average time to diagnosis of these patients is

around 10 years11.

A minority of GEP-NENs are functioning tumors and will present with functional syndromes11,30. The carcinoid syndrome is a functional syndrome that occurs due to the

excessive production of serotonin and is closely associated with NENs, particularly small intestinal NENs11. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter with a very short half-life that is quickly

metabolized to the inactive 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid by the liver and, therefore, the presence of a carcinoid syndrome is usually synonymous with liver metastases and advanced disease11,13,31. Features of carcinoid syndrome include flushing, diarrhea, abdominal pain and,

rarely, wheezing due to bronchospasm11. Pancreatic NENs may present with several different

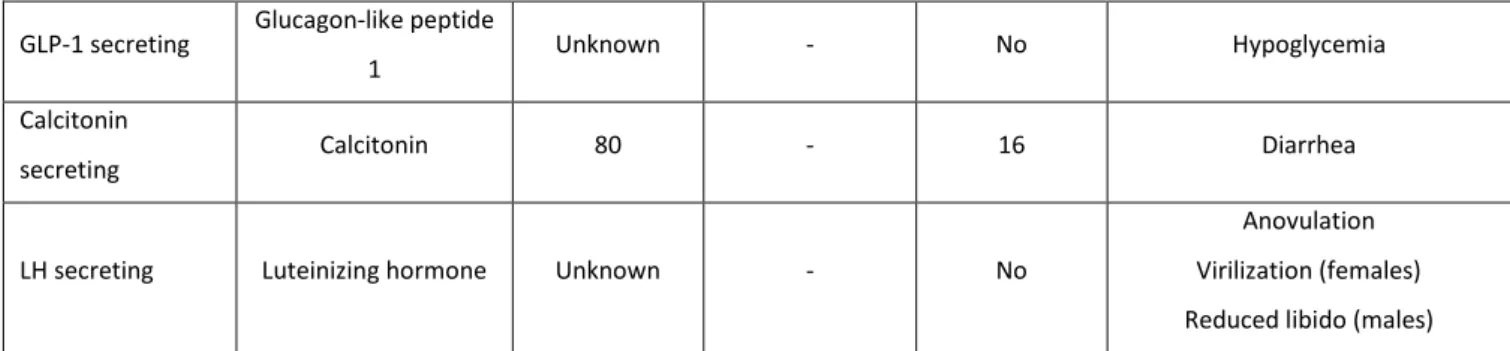

functional syndromes, depending on their cell of origin (Table 1)11,12,30. Unlike other functional

GEP-NENs, functional pancreatic tumors will usually be symptomatic even when the tumors are small and localized12,30.

As mentioned previously, the recent increase in incidence of GEP-NENs has been mostly due to asymptomatic, localized tumors found incidentally on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)4. Still, the

incidence of NENs at autopsy is still much higher (~1%), suggesting that most of these tumors are clinically silent and will not be diagnosed during the patients’ lifetime38,39.

3. Diagnostic Workup

3.1 Pathology

Histopathological analysis remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of NENs21. When

a NEN is suspected on morphological analysis, immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin and chromogranin A (CgA) is mandatory to confirm the phenotype9,21. Staining for somatostatin

receptor is not mandatory but may be useful, particularly if functional imaging is not available21.

Further immunohistochemical staining for peptide or amine hormones (e.g. insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, serotonin) may also be used to document neuroendocrine phenotype or to confirm the origin of clinical symptoms6,9,21.

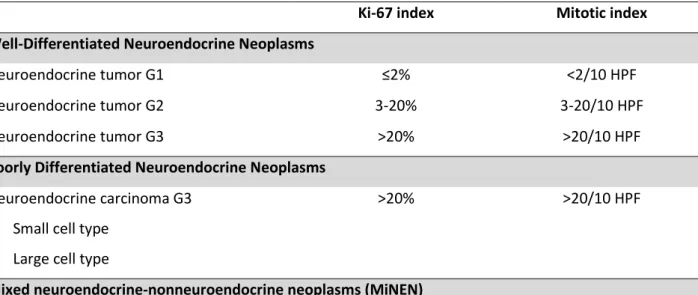

NENs should also be classified according to their morphology, into well-differentiated tumors (NET) or poorly differentiated carcinomas (NEC), and according to their proliferative

index (Ki-67 index and mitotic count), into low (G1), intermediate (G2), or high-grade (G3) (Table 2)9. Until recently, all high-grade tumors were considered poorly differentiated carcinomas but

the WHO 2019 classification introduced the term “NET G3” to reflect the fact that some high-grade tumors are more similar to well-differentiated NETs (similar morphologies, molecular alterations, clinical behavior and prognosis) than to poorly differentiated NECs8,9,40-42.

3.2 Biochemical Markers

Whenever there is a clinical suspicion of a functional syndrome, due the high specificity of hormonal assays, hormone level measurements or provocation tests should always be performed12,21,22. On the other hand, although non-functioning tumors may also have elevated

hormone levels, due to the low sensitivity of these tests, they should not be routinely performed in patients without clinical signs and symptoms of a functional syndrome11,22. Some exceptions

to this rule include routine measurement of serum gastrin in gastric NETs, routine measurement of urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in small intestinal NETs and in the work-up of hereditary syndromes, particularly, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1)12,29,30,36,37.

Besides its use in pathological exams, CgA is the most practical and effective serum marker for NENs since it can be elevated in both functioning and non-functioning tumors. High levels of CgA are rarely seen outside the setting of NENs, although false positive results may occur in the setting of chronic atrophic gastritis, proton pump inhibitor therapy or impaired renal function11,22. Still, the specificity of CgA for metastatic disease is close to 100%43. CgA levels also

play a role in the follow-up of patients with NENs (surveillance after resection and evaluation of therapeutic response).

3.3 Imaging

Following a NEN diagnosis, imaging exams are necessary to document disease location and staging. Ultrasound is generally not useful for staging most localized NENs although, given its easy accessibility and non-invasiveness, may be considered as a first-line modality in patients with suspected pancreatic NEN or hepatic metastases30,44. On the other hand, endoscopic US

(EUS) is the preferred method to locally stage gastric, duodenal, pancreatic, and rectal tumors12,14,29,30,33,36,37.

Given its high diagnostic yield, standardized reproducible technique and wide availability, abdominal-pelvic, multiphasic, contrast-enhanced CT remains a basic imaging exam for staging GEP-NENs11,21,36. MRI is generally better than CT at evaluating liver, pancreatic, bone

work-up23,36,45. In order to facilitate lesion detection, diffusion-weighted imaging is often applied to

MRI23,36.

Functional tumor imaging is an essential component of NEN imaging because it provides the highest sensitivity for nodal and distant metastasis by detecting infracentimetric lesions often missed by conventional imaging techniques10,23,36. It is also able to assess somatostatin

receptor expression (SSTR) which is often a requirement for initiation of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT)23,36. Functional imaging can be performed by two main techniques:

scintigraphy or positron emission tomography (PET)23. Both are based on the ectopic uptake of

radiolabeled (111In, 68Ga, 18F, 64Cu, 99mTc) somatostatin analogues (DTPA-OC, DOTATOC,

DOTANOC, DOTATATE) to identify well-differentiated NENs10,23. There are few comparative

studies regarding the efficacy of these tracers but, while all somatostatin analogues perform similarly, imaging protocols with 111In for scintigraphy and 68Ga for PET are generally

preferred10,23,36. A recent meta-analysis including 15 studies demonstrated a clear superiority of

somatostatin-receptor PET (SSTR-PET) over CT, MRI and scintigraphy in locating primary NETs, which prompted experts from several key working groups to recommend it as the preferred staging and pre-operative exam following a histological diagnosis10,36,46. Still, given the

importance of conventional imaging, the association of SSTR-PET with CT or MRI is strongly recommended10,23,36. Exceptionally, SSTR-PET is not routinely recommended for patients with

insulinomas, due to the characteristically low density of somatostatin receptors in these tumors47.

High-grade (G3) and poorly differentiated tumors will generally have a higher glucose metabolism and lower SSTR expression than low-grade, well-differentiated NETs23,36. 18

FDG-PET/CT may be useful in these patients particularly when a more accurate staging is expected to alter patient management13,31,36. (Table 3)

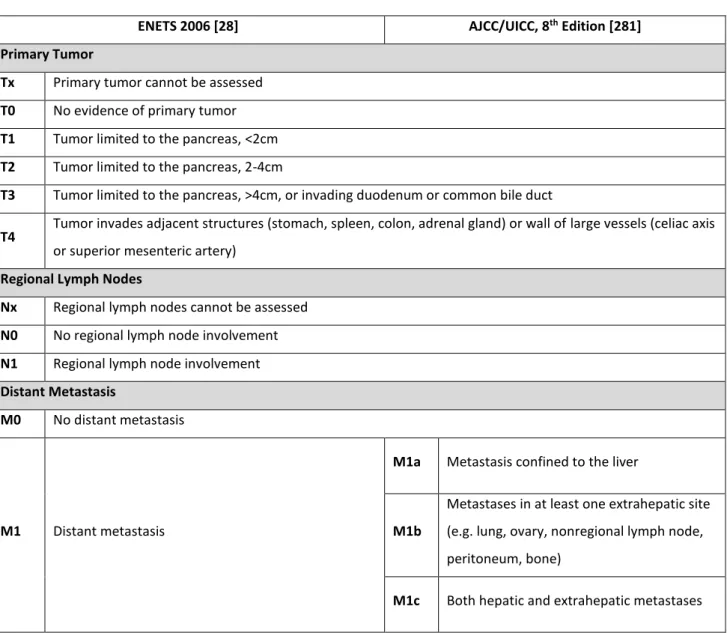

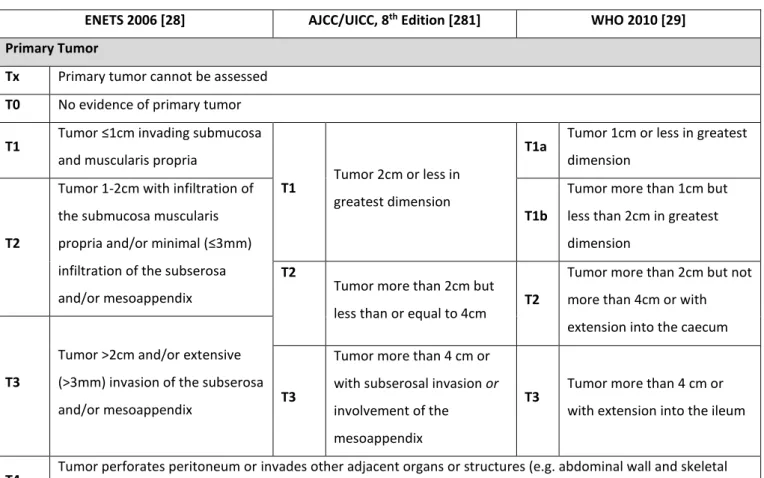

4. Staging and Prognosis

Disease stage and tumor grade are the main independent prognostic factors in GEP-NENs. Unlike tumor grade, which is evaluated similarly regardless of site or origin, the TNM staging is site specific5-8. While several TNM staging systems have been proposed over the years,

the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) system seems to be the most effective at stratifying and predicting prognosis and has been almost entirely adopted by both the WHO and the American Joint Committee on Cancer/ Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) for the majority of anatomic sites5-8. Of note, all these societies have slightly different TNM

proposes a slightly more detailed method for describing nodal and distant metastasis5-8. Unlike

NETs, NECs should be staged according to the staging system for adenocarcinomas6,7.

5. Treatment

5.1 Functional Syndromes

Medical management of symptoms will likely be required for most functional pancreatic NENs. If frequent small feedings are not enough to successfully control hypoglycemic symptoms in patients with insulinoma, diazoxide (200-600mg/day) is the most effective drug and will adequately control symptoms in 50-60% of patients12,30,36,37,48. Although somatostatin analogues

may be beneficial in the minority of SSTR-positive insulinoma patients, they may worsen hypoglycemia in the remaining patients48. Everolimus might also be of use in patients with

metastatic insulinoma and refractory hypoglycemia36,49. Patients with Zollinger-Ellison

syndrome will usually achieve adequate control of acid hypersecretion with proton pump inhibitors. H2-receptor antagonists may also be able to control symptoms but usually at higher and more frequent dosing than those required for peptic ulcer disease12,30,36,37,50. Rarer

functional syndromes, like VIPoma or glucagonoma, usually respond readily to somatostatin analogues (SSAs)12,30,37,48.

Depot formulations of octreotide and lanreotide will also adequately control symptoms in 70-90% of patients with carcinoid syndrome, and both are considered equally effective17,25,34,36,51. SSAs are the recommended first-line therapy for functional NENs although

short acting formulations, above standard doses or shorter intervals between doses might be required for adequate symptom control36,52,52. Following the results of the TELESTAR trial,

telotristat ethyl, a small molecule tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor, was found to be a safe and effective add-on therapy for patients with sub-optimal control of diarrhea despite SSA therapy and is recommended by ESMO for this indication36,54. ENETS and ESMO guidelines also suggest

that IFN-α may be useful for symptomatic control in patients with refractory carcinoid syndrome34,36.

5.2 Localized Neuroendocrine Neoplasms 5.2.1 Surveillance

Primary surveillance strategies are generally recommended for patients who present with small, non-functioning gastric or pancreatic tumors12,19,24,30,36. The largest subset of gastric

NETs (named type I tumors) are associated with compensatory hypergastrinemia due to chronic atrophic gastritis caused by autoimmune gastritis or long-standing H. pylori infection6,29,55.

Another subtype of gastric NETs (named type II tumors) are associated with dysregulated hypergastrinemia due to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome6,29,55. These tumors are usually small,

multiple, well-differentiated, non-functioning and frequently limited to the mucosa/submucosa6,55. Despite often recurring, these tumors have a very favorable

prognosis6,29,55. Thus, the majority of guidelines recommend that type I and II gastric NETs

<1-2cm do not need resection and can be managed with surveillance upper gastrointestinal endoscopies every 12-24 months16,28,30. Somatostatin analogue therapy can be considered in

these patients if they present with multiple or frequently recurring tumors12,37,56. Similarly,

non-functioning pancreatic tumors <1-2cm may be monitored with EUS assessment every 6-12 months, if patients/physicians wish to avoid a pancreatic resection12,19,24,30,36. If tumors grow to

>1-2cm, locally invade or develop regional or distant metastases, resection will be required12,19,24,30,36.

5.2.2 Endoscopic Resection

Tumors in locations with easy endoscopic access (stomach, duodenum, colon and rectum) can be safely and effectively managed by endoscopic resection provided they are well-differentiated, G1/G2, <2cm in size and with no signs of muscularis propria invasion or nodal involvement on EUS12,14,16,19,29,30,33,36,37. Ampullary/periampullary NENs are an exception since

they are usually more aggressive and should always be managed surgically, regardless of size at presentation29. Several techniques for endoscopic resection have been proposed but, given the

limited comparative data available, no specific endoscopic treatment is recommended over the rest. Overall, endoscopic submucosal dissection achieves higher complete resection rates when compared to endoscopic mucosal resection, although at the cost of increased complication rates57-61.

5.2.3 Surgery

Surgical resection with lymphadenectomy is recommended for all ampullary/ periampullary and small intestinal NENs, pancreatic NENs that do not fulfill the criteria for surveillance, and for all other localized NETs that are >2cm, G3 or have evidence of muscularis propria involvement, lymph node metastasis or local invasion12-20,24,29-37. Small appendiceal NENs

are occasionally found incidentally on appendectomies. These tumors will not require conversion to right hemicolectomy with lymphadenectomy unless they are >2cm, G3 or have evidence of nodal involvement or local invasion32. Though surgery is rarely curative in patients

evidence of nodal or distant metastasis all undergo surgical resection with lymphadenectomy15,16,35-37.

5.2.4 Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Patients with curatively resected localized G1/G2 tumors do not require any adjuvant chemotherapy16,26,36,37. Patients with resected localized high-grade tumors will require routine

adjuvant chemotherapy with either streptozotocin-based regimens, for well-differentiated tumors, or cisplatin and etoposide, for poorly differentiated carcinomas16,35,36,37.

5.3 Advanced/Metastatic Disease 5.3.1 Surgery

In metastatic disease, surgical treatment with curative intent should be offered to all patients with well-differentiated, G1/G2 disease provided: there is a resectable primary tumor, resectable liver metastases and there are no extrahepatic metastases or peritoneal carcinomatosis18,19,34,36,37. Resection of high-grade disease is controversial, but may be

considered in select patients with well-differentiated tumors (NET G3)18,19,34,36.

Currently, the precise indications for palliative liver resections are still controversial. While NANETS suggests that non-curative hepatic cytoreduction may be offered whenever feasible, the remaining societies suggest the procedure should be limited to patients who remain symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy and where a reduction of 90% of hepatic tumor burden can be achieved18,19,34,36.

Orthotopic liver transplant may be an option in exceptionally selected patients with life-threatening hormonal disturbances refractory to surgical and medical therapy or in patients with symptoms related to tumor burden24,34,36. However, there is a high recurrence rate associated

with liver transplant and it should be viewed as a palliative procedure rather than a curative procedure34.

Palliative primary tumor resections should be considered in all symptomatic patients18,19,36,37. Prophylactic resection of asymptomatic small intestinal primary tumors is

generally recommended to avoid future symptoms or complications18,24,34,36. There is no

consensus regarding prophylactic resection of primary non-functional pancreatic NENs19,24,34,36.

5.3.2 Ablative Techniques

Ablative or intra-arterial embolization techniques may be considered as a mean of relieving symptoms of NEN liver metastases or achieving local tumor control. In patients with borderline resectable liver disease, ablative techniques, such as radiofrequency ablation or

microwave ablation, may be recommended as a supplement to surgery to optimally decrease tumor burden62-64. Transarterial embolization or chemoembolization are also recommended in

patients with unresectable disease but who remain symptomatic despite medical therapy with SSAs17-19,34,37. Embolization techniques may be considered for later lines of treatment in patients

with non-functional tumors that progress despite optimal medical therapy17-19,34,37. Selective

internal radiation therapy is currently considered investigational34.

5.3.3 Antiproliferative Treatment

The effectiveness of depot octreotide and lanreotide as antiproliferative agents has been assessed in the PROMID and CLARINET trials, respectively65,66. While both are

recommended for small intestinal NENs, lanreotide is preferred in pancreatic NEN given the lack of prospective data regarding octreotide in this clinical setting12,13,17,34,36,37. Currently, either SSA

therapy or a watch and wait strategy are considered acceptable for asymptomatic patients with NET G1, low tumor burden (<10% liver tumor burden and no extrahepatic disease) and stable disease12,17,34,36,37. Patients with NET G2, high tumor burden (>25% liver tumor burden) or

progressive disease should start SSA therapy34,36. SSA therapy is generally not recommended for

SSTR-negative tumors and tumors with a Ki-67 >10%25,34,36.

Following the results of several prospective randomized clinical trials, two targeted drugs (everolimus and sunitinib) have been approved for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic NENs67-69. The combination of SSA with everolimus/sunitinib does not provide additional

benefits and this association is not recommended for antiproliferative purposes34,36.

Furthermore, due to the increased frequency of side effects, everolimus/sunitinib are currently only recommended in patients who are ineligible for first-line treatment with SSAs or who progress on SSA therapy17,25,34,36,37. Studies have also reported similar benefits of everolimus in

the setting of extra-pancreatic NENs and it is currently recommended as third-line therapy after progression on, contraindication or unavailability of SSAs and PRRT17,25,34,36,37.

5.3.4 Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy

PRRT relies on the frequent expression of SSTR by tumor cells and their avidity for SSAs to selectively deliver therapeutic radioisotopes27. No SSA is preferred over another but 177Lu is

generally preferred over 90Y given its superior safety profile and the ability to easily perform

scintigraphy and dosimetry27.

The effectiveness and safety of PRRT was verified in the NETTER-1 trial, which compared

177Lu-DOTATATE plus LAR octreotide to LAR octreotide alone in patients with small intestinal

response rates (18% vs 3% of patients) and a significant increase in progression-free survival (median progression-free not reached vs 8.4 months)70. Though the final analysis of overall

survival is yet to be performed, interim analysis point to a trend of increased overall survival70.

Serious reported side effects (grade 3/4) are mostly hematological (cytopenia, myelodysplasia, leukemia) and up to 30% of patients may develop mild renal toxicity (grade 1/2)36. Given these

results PRRT is currently recommended as second-line therapy in patients with unresectable, well-differentiated, SSTR-positive small intestinal NENs, following progression on SSAs12,34,36,37.

Since similar results have also been described in retrospective studies of PRRT in patients with pancreatic NENs, PRRT is a valid third-line option for patients with pancreatic NENs who have disease progression on SSAs and everolimus/sunitinib12,17,34,36,37. Patients with high-grade

tumors generally do not benefit from PRRT, but ENETS and ESMO suggest this therapy may be considered in patients with well-differentiated NET G335,36.

5.3.5 Systemic Chemotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy is recommended for all patients with unresectable G1/G2 pancreatic NEN that progresses on SSA therapy and everolimus/sunitinib26,34,36,37. ENETS and

ESMO further suggest that chemotherapy might be considered as first line-therapy in patients with high tumor burden or rapidly progressive disease (<6-12 months to progression)26,34,36.

Current established chemotherapeutic regimens include streptozocin-based therapies associated with either 5-fluorouracil or doxorubicin26,34,36,37. Recently, temozolomide-based

regimens, as monotherapy or associated with capecitabine, have been gaining popularity and produce similar results to streptozocin-based regimens but with a lower toxicity profile71,72.

There is no consensus on which chemotherapy regimen is best, but experts seem to favor temozolomide-based schemes based on their similar effectiveness and acceptable toxicity profile37. Conversely, outcomes of chemotherapy in patients with metastatic well-differentiated

G1/G2 non-pancreatic NENs are poor73. While some experts believe the systemic toxicity of

chemotherapy does not warrant its use in these patients, others believe that it is an important alternative in patients with progressive disease and no other treatment lines12,16,34,36,37.

Patients with high-grade tumors are often treated in analogy to patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC)26,35 with a standard first-line association of cisplatin and etoposide. Alternate

regimens substituting cisplatin for carboplatin and irinotecan for etoposide have already been validated in SCLC and studies show similar effectiveness in patients with GEP NECs74,75. Evidence

for second-line therapy after disease progression is lacking. Frequently employed strategies include reintroduction of first-line therapy, provided progression occurs after a treatment break

of at least 3 months, or oxaliplatin or irinotecan-based regimens26,34,37. Regardless of the

chemotherapy regimen chosen as second-line therapy, response rates are low74,75.

High-grade well-differentiated GEP-NENs used to be classified and treated as poorly differentiated carcinomas and, therefore, systemic platinum-based therapy (typically, cisplatin/etoposide) was often employed as first-line treatment34,35. However, tumors with

Ki-67 <20-55% always had a much lower response rate to these platinum-based regimens than tumors with a Ki-67 >55% (15 vs 42%, respectively)52. Although studies are lacking, most experts

agree that patients with NET G3 may respond more favorably to streptozocin- or temozolomide-based therapies26,35-37.

6. Follow-up

Patients who undergo curative resections of well-differentiated, G1/G2 tumors will require a follow-up every 6-12 months with biochemical testing and imaging with CT/MRI and SSTR-PET16,23,28,36,37. Patients with resected NET G3, resected poorly differentiated carcinoma or

unresectable disease require a closer follow-up every 3-6 months16,34,36,37. Although the

maximum length of the follow-up period remains to be defined, a minimum follow-up of 10 years is usually recommended16,28,36,37.

Exceptionally, patients with small appendiceal or rectal NENs may be considered cured provided they have completely resected, small, low-grade, non-invasive tumors14,19,32,33,35,37.

These patients will not require any follow-up. The follow-up of patients with type I/II gastric NENs and pancreatic NENs undergoing surveillance has been discussed previously. (Table 4)

7. Commentary

Although GEP-NENs are increasingly more frequent in clinical practice, appropriate management decisions are still challenging due to a lack of recommendations based on robust evidence. Currently, clinicians must rely heavily on their own judgement and multidisciplinary discussion to offer the highest standard of care possible to their patients. Given their rarity and heterogeneity, patients with GEP-NENs benefit with referral to specialized centers. Besides providing clinical care, these centers should collaborate in multi-institutional prospective research to produce high-quality evidence.

8. Tables and Figures

Table 1 -Summary of clinical features of functional NENs of the pancreas

Name Hormone secreted Metastases present in (%) Pancreatic involvement (%) Associated with MEN-1 (%)

Main symptoms/ signs

Common Functional Pancreatic NEN syndromes

Insulinoma Insulin <10 >99 4-5 Neuroglycopenia

Sympathetic overdrive

Gastrinoma Gastrin 60-90 25 20-25

Pain

Gastric/duodenal ulcers Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Diarrhea

Rare Functional Pancreatic NEN syndromes (>100 cases reported)

VIPoma Vasoactive Intestinal

Peptide 40-70

90, in adults

Rare, in children 6

Large volume diarrhea Dehydration Hypokalemia Achlorhydria

Glucagonoma Glucagon 50-80 100 1-20

Migratory necrolytic erythema Glucose intolerance Weight loss Somatostatinoma (SSoma) Somatostatin >70 55 45% Diabetes Mellitus Cholelithiasis Diarrhea GRHoma Growth-hormone releasing hormone >60 30 16 Acromegaly ACTHoma Adrenocorticotropic

hormone >95 Rare Rare Cushing’s syndrome

Carcinoid Serotonin 60-88 Rare Rare Carcinoid syndrome

PTH-rPoma Parathyroid hormone

related peptide 84 Rare Rare

Hypercalcemia Abdominal pain due to hepatic

metastases

Very rare Functional Pancreatic NEN syndromes (1-5 cases reported)

Renin-secreting Renin Unknown - No Hypertension

Erythropoietin

secreting Erythropoietin 100 - No Polycythemia

IF-II-secreting Insulin-like growth

factor II Unknown - No Hypoglycemia

CCKoma Cholecystokinin Unknown - No

Diarrhea Ulcer disease

Weight loss Cholelithiasis

GLP-1 secreting Glucagon-like peptide

1 Unknown - No Hypoglycemia

Calcitonin

secreting Calcitonin 80 - 16 Diarrhea

LH secreting Luteinizing hormone Unknown - No

Anovulation Virilization (females) Reduced libido (males) Adapted from Falconi et al.30

Table 2 - WHO 2017 & WHO 2019 grading system for pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms

Ki-67 index Mitotic index

Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

Neuroendocrine tumor G1 ≤2% <2/10 HPF

Neuroendocrine tumor G2 3-20% 3-20/10 HPF

Neuroendocrine tumor G3 >20% >20/10 HPF

Poorly Differentiated Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

Neuroendocrine carcinoma G3 Small cell type

Large cell type

>20% >20/10 HPF

CgA Markers Endoscopy CT/MRI/US PET Comments Gastric

Type I Yes

Gastrin, gastric pH (if necessary), Anti-parietal cell antibody,

Anti-intrinsic factor antibody, Vitamin B12 levels, H. pylori status

UGI endoscopy with gastric mapping, EUS is recommended for tumors >1cm >2cm: CT recommended Not routinely recommended

Type II Yes Gastrin, gastric pH (if

necessary) EUS recommended

>2cm: CT recommended SSTR-PET recommended Consider inherited genetic syndromes

Type III Yes Gastrin EUS recommended CT/MRI

recommended

SSTR-PET recommended

Duodenal

Yes Hormonal study as

clinically indicated EUS recommended

CT/MRI recommended SSTR-PET recommended Consider inherited genetic syndromes Pancreas Non-functioning Yes - EUS recommended FNAB may be useful in

selected patients US recommended, CT/MRI recommended SSTR-PET recommended Consider inherited genetic syndromes

Insulinoma Yes Glucose, insulin,

72-hour fasting test

EUS, if non-invasive studies are negative

US recommended, CT/MRI recommended Not routinely recommended Consider inherited genetic syndromes Gastrinoma Yes Gastrin, gastric pH (if

necessary) EUS recommended

US recommended, CT/MRI recommended SSTR-PET recommended Consider inherited genetic syndromes Other functioning tumor Yes Hormonal study as clinically indicated EUS, if non-invasive studies are negative

US recommended, CT/MRI recommended SSTR-PET recommended Consider inherited genetic syndromes Small Intestine Yes

Urine 5-HIAA Colonoscopy

recommended CT/MRI recommended

SSTR-PET recommended Appendix <2cm, G1/G2, R0 and no adverse features Not

recommended Not recommended Not recommended

CT/MRI suggested for

tumors 1-2cm Not recommended No follow-up required >2cm, G3, R1/2 or

any adverse features

Not routinely recommended

Not routinely recommended

Colonoscopy

recommended CT/MRI recommended

SSTR-PET recommended

Colon

Yes Not routinely recommended

Colonoscopy

recommended CT/MRI recommended

SSTR-PET recommended

NANETS suggests patients with tumors <2cm, G1/G2, R0 and

Table 3- Summary of initial diagnostic studies for individual primary tumor locations

no adverse features do not require additional studies Rectum <1cm, G1, R0 and no adverse features Not

recommended Not recommended Not recommended Not recommended Not recommended No follow-up required 1-2cm, G1, R0 and

no adverse features Yes

Not routinely recommended EUS recommended, Colonoscopy recommended by ENETS only CT/MRI recommended by ENETS only SSTR-PET recommended by ENETS only >2cm, G3, R1/2 or

any adverse features Yes

Not routinely recommended EUS recommended, Colonoscopy recommended MRI mandatory CT recommended SSTR-PET recommended Unknown Primary

Yes Hormonal study as clinically indicated

UGI endoscopy, colonoscopy, DBE,

VCE, as clinically indicated

Liver US-guided biopsy recommended, CT/MRI recommended SSTR-PET recommended Poorly differentiated Yes ESMO recommends routine NSE and LDH

Hormonal study as clinically indicated

Follow primary tumor location recommendation CT/MRI recommended FDG-PET mandatory if undergoing surgery, SSTR-PET may be useful in selected patients

Hereditary Syndrome Associated

MEN1-associated Yes

Gastrin, insulin, glucagon, prolactin,

somatostatin, PTH, serum glucose, serum

Ca2+

EUS recommended CT/MRI recommended SSTR-PET recommended

NF1-associated Yes Somatostatin,

calcitonin EUS recommended CT/MRI recommended

SSTR-PET recommended

Table 4- Summary of follow-up recommendations for individual tumor sites

Follow-up

interval CgA Markers Endoscopy CT/MRI/PET Comments

Gastric Type I – Resected or primary surveillance strategy 6-12ma Every visit Gastrin, iron, vitamin B12 every visit

UGI endoscopy every

12-24m Not recommended

EUS not routinely recommended, may be useful if progression or recurrence is suspected Type II – Resected or primary surveillance strategy 6-12m Every visit Gastrin, serum Ca2+, PTH every visit

UGI endoscopy every 12-24m

CT/MRI recommended every visit by ENETS only

EUS not routinely recommended, may be useful if progression or recurrence is suspected Type III – Resected ENETS: 2-3m NCCN: 12-24mb Every visit Not routinely recommended

UGI endoscopy every: ENETS: 6-12m

NCCN: 12-24m

CT/MRI/PETc every:

ENETS: 2-6m NCCN: 12-24m

EUS not routinely recommended, may be useful if progression or recurrence is suspected

Duodenal

Resected 6-12mb Every visit As clinically

indicated

UGI endoscopy every: ENETS: 6-12m

NCCN: 12-24m

CT/MRI every 12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m

EUS not routinely recommended, may be useful if progression or recurrence is suspected Pancreas Non-functional – Primary surveillance strategy ENETS 3-6ma

NCCN: 6-12ma Every visit - EUS every 6-12m

CT/MRI every ENETS: 3-6m NCCN: 6-12m Non-functional – Resected ENETS 3-6mb

NCCN: 6-12mb Every visit - Not recommended

CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m

Localized insulinoma –

Resected Once Once

Insulin, glucose, 72-hour fasting test once

Not recommended Not recommended Non-localized insulinoma – Resected ENETS 3-6mb NCCN: 6-12mb Every visit Insulin, glucose, 72-hour fasting test, every visit

Not recommended CT/MRI every ENETS: 3-6m NCCN: 6-12m Gastrinoma – Resected ENETS 3-6mb NCCN: 6-12mb Every visit Gastrin, serum Ca2+, PTH every visit

Not recommended CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m

Other functional tumor – Resected

ENETS 3-6mb

NCCN: 6-12b Every visit

As clinically

indicated Not recommended

CT/MRI every ENETS: 3-6m NCCN: 6-12m

SSTR-PETc every 12-24m Small Intestine

Resected 6-12mb Every visit Urine 5-HIAA

every visit Not recommended

CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m Appendix <2cm, G1/G2, R0 and no adverse features – Resected

6-12mb Every visit Not routinely

recommended Not recommended

CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m

>2cm, G3, R1/2 or any adverse features – Resected

6-12mb Every visit Not routinely

recommended Not recommended

CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 24m Colon

Resected 6-12mb Every visit Not routinely

recommended

Colonoscopy every 12-24m

CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m

NANETS suggests patients with tumors <2cm, G1/G2, R0 and no adverse features do not require follow-up Rectum <1cm, G1, R0 and no adverse features – Resected Once Not recommended Not

recommended Not recommended Not recommended 1-2cm, G1, R0 and no

adverse features – Resected

At least onceb

or every 12m Every visit

Not

recommended

Endorectal US once Colonoscopy every 12m

CT/MRI at least once or every 6-12m

NANETS suggests these patients do not require any follow-up

>2cm, G3, R1/2 or any adverse features – Resected

6-12mb Every visit Not routinely

recommended

Colonoscopy every 12m

CT/MRI every 6-12m SSTR-PETc every 12-24m Metastatic or unresectable disease

3-6ma Every visit As clinically

indicatedd,e Not recommended

CT/MRI every 3-6m SSTR-PETc every 18-24m NET G3/NEC

Resected 3/3m for 2-3y

6-12/6-12 for 5y Every visit

Not routinely recommended

Follow primary tumor location recommendation

CT/MRI every visit FDG-PET may be useful in select patients

Unresectable 2-3m Every visit

ESMO recommends routine NSE and LDH

Not recommended

CT/MRI every visit FDG-PET may be useful in select patients

9. References

1- Modlin, Irvin M., Kevin D. Lye, and Mark Kidd. 2003. “A 5-Decade Analysis of 13,715 Carcinoid Tumors.” Cancer 97 (4): 934–59.

2- Dasari, Arvind, Chan Shen, Daniel Halperin, Bo Zhao, Shouhao Zhou, Ying Xu, Tina Shih, and James C. Yao. 2017. “Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States.” JAMA Oncology 3 (10): 1335–42. 3- Yao, James C., Manal Hassan, Alexandria Phan, Cecile Dagohoy, Colleen Leary, Jeannette E. Mares, Eddie K. Abdalla, et al. 2008. “One Hundred Years after ‘Carcinoid’: Epidemiology of and Prognostic Factors for Neuroendocrine Tumors in 35,825 Cases in the United States.” Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 26 (18): 3063–72.

4- Oronsky, Bryan, Patrick C. Ma, Daniel Morgensztern, and Corey A. Carter. 2017. “Nothing But NET: A Review of Neuroendocrine Tumors and Carcinomas.” Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 19 (12): 991–1002.

5- Rindi, G., G. Klöppel, A. Couvelard, P. Komminoth, M. Körner, J. M. Lopes, A.-M. McNicol, et al. 2007. “TNM Staging of Midgut and Hindgut (Neuro) Endocrine Tumors: A Consensus Proposal Including a Grading System.” Virchows Archiv: An International Journal of Pathology 451 (4): 757–62.

6- Klimstra DS, Arnold R, Capella C, et al, WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System, WHO Classification of Tumors, 4th Edition, Volume 3. Lyon, France: IACR Press, 2010.

7- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, et al. (Eds.). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th edition). Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on Cancer; 2017.

8- Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J, WHO Classification of Tumors of Endocrine Organs, WHO Classification of Tumors, 4th Edition, Volume 10. Lyon, France: IACR Press, 2017. 9- WHO Classification of Tumors Editorial Board; Digestive System Tumors, WHO Classification of Tumors, 5th Edition, Volume 1. Lyon, France: IACR Press, 2019.

10- Hope, Thomas A., Emily K. Bergsland, Murat Fani Bozkurt, Michael Graham, Anthony P. Heaney, Ken Herrmann, James R. Howe, et al. 2018. “Appropriate Use Criteria for Somatostatin

Receptor PET Imaging in Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Journal of Nuclear Medicine: Official Publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 59 (1): 66–74.

11-Vinik, Aaron I., Eugene A. Woltering, Richard R. P. Warner, Martyn Caplin, Thomas M. O’Dorisio, Gregory A. Wiseman, Domenico Coppola, Vay Liang W. Go, and North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS). 2010. “NANETS Consensus Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Neuroendocrine Tumor.” Pancreas 39 (6): 713–34.

12- Kulke, Matthew H., Lowell B. Anthony, David L. Bushnell, Wouter W. de Herder, Stanley J. Goldsmith, David S. Klimstra, Stephen J. Marx, et al. 2010. “NANETS Treatment Guidelines.” Pancreas 39 (6): 735–52.

13- Boudreaux, J. Philip, David S. Klimstra, Manal M. Hassan, Eugene A. Woltering, Robert T. Jensen, Stanley J. Goldsmith, Charles Nutting, et al. 2010. “The NANETS Consensus Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors: Well-Differentiated

Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Jejunum, Ileum, Appendix, and Cecum.” Pancreas 39 (6): 753– 66.

14- Anthony, Lowell B., Jonathan R. Strosberg, David S. Klimstra, William J. Maples, Thomas M. O’Dorisio, Richard R. P. Warner, Gregory A. Wiseman, Al B. Benson, Rodney F. Pommier, and North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS). 2010. “The NANETS Consensus Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors (Nets): Well-Differentiated Nets of the Distal Colon and Rectum.” Pancreas 39 (6): 767–74. 15- Strosberg, Jonathan R., Domenico Coppola, David S. Klimstra, Alexandria T. Phan, Matthew H. Kulke, Gregory A. Wiseman, Larry K. Kvols, and North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS). 2010. “The NANETS Consensus Guidelines for the Diagnosis and

Management of Poorly Differentiated (High-Grade) Extrapulmonary Neuroendocrine Carcinomas.” Pancreas 39 (6): 799–800. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb56f. 16- Kunz, Pamela L., Diane Reidy-Lagunes, Lowell B. Anthony, Erin M. Bertino, Kari Brendtro, Jennifer A. Chan, Herbert Chen, et al. 2013. “Consensus Guidelines for the Management and Treatment of Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Pancreas 42 (4): 557–77.

17- Strosberg, Jonathan R., Thorvardur R. Halfdanarson, Andrew M. Bellizzi, Jennifer A. Chan, Joseph S. Dillon, Anthony P. Heaney, Pamela L. Kunz, et al. 2017. “The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Guidelines for Surveillance and Medical Management of Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Pancreas 46 (6): 707–14.

18- Howe, James R., Kenneth Cardona, Douglas L. Fraker, Electron Kebebew, Brian R. Untch, Yi-Zarn Wang, Calvin H. Law, et al. 2017. “The Surgical Management of Small Bowel

Neuroendocrine Tumors: Consensus Guidelines of the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS).” Pancreas 46 (6): 715–31.

19- Howe, James R., Nipun B. Merchant, Claudius Conrad, Xavier M. Keutgen, Julie Hallet, Jeffrey A. Drebin, Rebecca M. Minter, et al. 2020. “The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Paper on the Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Pancreas 49 (1): 1–33.

20- Caplin, Martyn, Anders Sundin, Ola Nillson, Richard P. Baum, Klaus J. Klose, Fahrettin Kelestimur, Ursula Plöckinger, et al. 2012. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Digestive Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Colorectal Neuroendocrine

Neoplasms.” Neuroendocrinology 95 (2): 88–97.

21- Perren, Aurel, Anne Couvelard, Jean-Yves Scoazec, Frederico Costa, Ivan Borbath, Gianfranco Delle Fave, Vera Gorbounova, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Pathology: Diagnosis and Prognostic

Stratification.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 196–200.

22- Oberg, Kjell, Anne Couvelard, Gianfranco Delle Fave, David Gross, Ashley Grossman, Robert T. Jensen, Ulrich-Frank Pape, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Standard of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumours: Biochemical Markers.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 201–11. 23- Sundin, Anders, Rudolf Arnold, Eric Baudin, Jaroslaw B. Cwikla, Barbro Eriksson, Stefano Fanti, Nicola Fazio, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Radiological, Nuclear Medicine & Hybrid Imaging.”

Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 212–44.

24- Partelli, Stefano, Detlef K. Bartsch, Jaume Capdevila, Jie Chen, Ulrich Knigge, Bruno Niederle, Els J. M. Nieveen van Dijkum, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Standard of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumours: Surgery for Small Intestinal and Pancreatic

Neuroendocrine Tumours.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 255–65.

25- Pavel, Marianne, Juan W. Valle, Barbro Eriksson, Anja Rinke, Martyn Caplin, Jie Chen, Frederico Costa, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Systemic Therapy - Biotherapy and Novel Targeted Agents.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 266–80.

26- Garcia-Carbonero, Rocio, Anja Rinke, Juan W. Valle, Nicola Fazio, Martyn Caplin, Vera Gorbounova, Juan O Connor, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Systemic Therapy 2: Chemotherapy.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 281–94.

27- Hicks, Rodney J., Dik J. Kwekkeboom, Eric Krenning, Lisa Bodei, Simona Grozinsky-Glasberg, Rudolf Arnold, Ivan Borbath, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasia: Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy with Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analogues.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 295–309.

28- Knigge, U., J. Capdevila, D. K. Bartsch, E. Baudin, J. Falkerby, R. Kianmanesh, B. Kos-Kudla, et al. 2017. “ENETS Consensus Recommendations for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Follow-Up and Documentation.” Neuroendocrinology 105 (3): 310–19.

29- Delle Fave, G., D. O’Toole, A. Sundin, B. Taal, P. Ferolla, J. K. Ramage, D. Ferone, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Gastroduodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms.” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 119–24.

30- Falconi, M., B. Eriksson, G. Kaltsas, D. K. Bartsch, J. Capdevila, M. Caplin, B. Kos-Kudla, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 153–71.

31- Niederle, B., U.-F. Pape, F. Costa, D. Gross, F. Kelestimur, U. Knigge, K. Öberg, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Jejunum and Ileum.” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 125–38.

32- Pape, U.-F., B. Niederle, F. Costa, D. Gross, F. Kelestimur, R. Kianmanesh, U. Knigge, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Appendix (Excluding Goblet Cell Carcinomas).” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 144–52.

33- Ramage, J. K., W. W. De Herder, G. Delle Fave, P. Ferolla, D. Ferone, T. Ito, P. Ruszniewski, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms.” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 139–43.

34- Pavel, M., D. O’Toole, F. Costa, J. Capdevila, D. Gross, R. Kianmanesh, E. Krenning, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Distant Metastatic Disease of Intestinal, Pancreatic, Bronchial Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of Unknown Primary Site.” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 172–85.

35- Garcia-Carbonero, R., H. Sorbye, E. Baudin, E. Raymond, B. Wiedenmann, B. Niederle, E. Sedlackova, et al. 2016. “ENETS Consensus Guidelines for High-Grade Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Neuroendocrine Carcinomas.” Neuroendocrinology 103 (2): 186– 94.

36- Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, Krenning E, Sundin A, Perren A, Berruti A, on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Committee, Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†, Annals of Oncology (2020), in press.

37- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 1.2019, NCCN.org

38- Moertel, C. G., W. G. Sauer, M. B. Dockerty, and A. H. Baggenstoss. 1961. “Life History of the Carcinoid Tumor of the Small Intestine.” Cancer 14 (October): 901–12.

39- Berge, T., and F. Linell. 1976. “Carcinoid Tumours. Frequency in a Defined Population during a 12-Year Period.” Acta Pathologica Et Microbiologica Scandinavica. Section A, Pathology 84 (4): 322–30.

40- Sorbye, Halfdan, Jonathan Strosberg, Eric Baudin, David S. Klimstra, and James C. Yao. 2014. “Gastroenteropancreatic High-Grade Neuroendocrine Carcinoma.” Cancer 120 (18): 2814–23.

41- Tang, Laura H., Brian R. Untch, Diane L. Reidy, Eileen O’Reilly, Deepti Dhall, Lily Jih, Olca Basturk, Peter J. Allen, and David S. Klimstra. 2016. “Well Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors with a Morphologically Apparent High Grade Component: A Pathway Distinct from Poorly Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinomas.” Clinical Cancer Research : An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 22 (4): 1011–17.

42- Basturk, Olca, Zhaohai Yang, Laura H. Tang, Ralph H. Hruban, N. Volkan Adsay, Chad M. McCall, Alyssa M. Krasinskas, et al. 2015. “The High Grade (WHO G3) Pancreatic

Neuroendocrine Tumor Category Is Morphologically And Biologically Heterogenous And Includes Both Well Differentiated And Poorly Differentiated Neoplasms,” The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 39 (5): 683–90.

43- Yang, Xin, Yuan Yang, Zhilu Li, Chen Cheng, Ting Yang, Cheng Wang, Lin Liu, and Shengchun Liu. 2015. “Diagnostic Value of Circulating Chromogranin A for Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLOS ONE 10 (4): e0124884.

44- Hoeffel, Christine, Louis Job, Viviane Ladam-Marcus, Fabien Vitry, Guillaume Cadiot, and Claude Marcus. 2009. “Detection of Hepatic Metastases from Carcinoid Tumor: Prospective Evaluation of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography.” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 54 (9): 2040–46.

45- Dromain, Clarisse, Thierry de Baere, Eric Baudin, Joel Galline, Michel Ducreux, Valérie Boige, Pierre Duvillard, et al. 2003. “MR Imaging of Hepatic Metastases Caused by Neuroendocrine Tumors: Comparing Four Techniques.” AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology 180 (1): 121–28.

46- Pacific Northwest Evidence-Based Practice Center. Systematic Review: Somatostatin Imaging for Neuroendocrine Tumors. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Health and Science University; 2017

47- Sharma, Punit, Saurabh Arora, Sellam Karunanithi, Rajesh Khadgawat, Prashant Durgapal, Raju Sharma, Devasenathipathy Kandasamy, Chandrasekhar Bal, and Rakesh Kumar. 2016. “Somatostatin Receptor Based PET/CT Imaging with 68Ga-DOTA-Nal3-Octreotide for Localization of Clinically and Biochemically Suspected Insulinoma.” The Quarterly Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging: 60 (1): 69–76.

48- Metz, David C., and Robert T. Jensen. 2008. “Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors: Pancreatic Endocrine Tumors.” Gastroenterology 135 (5): 1469–92.

49- Kulke, Matthew H., Emily K. Bergsland, and James C. Yao. 2009. “Glycemic Control in Patients with Insulinoma Treated with Everolimus.” The New England Journal of Medicine 360 (2): 195–97.

50- Osefo, Nauramy, Tetsuhide Ito, and Robert T. Jensen. 2009. “Gastric Acid Hypersecretory States: Recent Insights and Advances.” Current Gastroenterology Reports 11 (6): 433–41. 51- Modlin, I. M., M. Pavel, M. Kidd, and B. I. Gustafsson. 2010. “Review Article: Somatostatin Analogues in the Treatment of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine (Carcinoid) Tumours.” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 31 (2): 169–88.

52- Strosberg, Jonathan R., Al B. Benson, Lynn Huynh, Mei Sheng Duh, Jamie Goldman, Vaibhav Sahai, Alfred W. Rademaker, and Matthew H. Kulke. 2014. “Clinical Benefits of Above-Standard Dose of Octreotide LAR in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors for Control of Carcinoid Syndrome Symptoms: A Multicenter Retrospective Chart Review Study.” The Oncologist 19 (9): 930–36.

53- Al-Efraij, Khalid, Mohammed A. Aljama, and Hagen Fritz Kennecke. 2015. “Association of Dose Escalation of Octreotide Long-Acting Release on Clinical Symptoms and Tumor Markers and Response among Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Cancer Medicine 4 (6): 864–70. 54- Kulke, M. H., D. Horsch, M. Caplin, L. Anthony, E. Bergsland, K. Oberg, S. Welin, et al. 2015. “37LBA Telotristat Etiprate Is Effective in Treating Patients with Carcinoid Syndrome That Is Inadequately Controlled by Somatostatin Analog Therapy (the Phase 3 TELESTAR Clinical Trial).” European Journal of Cancer 51 (September): S728.

55- Merola, Elettra, Andrea Sbrozzi-Vanni, Francesco Panzuto, Giancarlo D’Ambra, Emilio Di Giulio, Emanuela Pilozzi, Gabriele Capurso, et al. 2012. “Type I Gastric Carcinoids: A

Prospective Study on Endoscopic Management and Recurrence Rate.” Neuroendocrinology 95 (3): 207–13.

56- Tomassetti, Paola, Marina Migliori, Gian Carlo Caletti, Pietro Fusaroli, Roberto Corinaldesi, and Lucio Gullo. 2000. “Treatment of Type II Gastric Carcinoid Tumors with Somatostatin Analogues.” New England Journal of Medicine 343 (8): 551–54.

57- Kim, Hyung Hun, Gwang Ha Kim, Ji Hyun Kim, Myung-Gyu Choi, Geun Am Song, and Sung Eun Kim. 2014. “The Efficacy of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Type I Gastric Carcinoid Tumors Compared with Conventional Endoscopic Mucosal Resection.” Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2014: 253860.

58- Sato, Yuichi, Manabu Takeuchi, Satoru Hashimoto, Ken-ichi Mizuno, Masaaki Kobayashi, Mitsuya Iwafuchi, Rintaro Narisawa, and Yutaka Aoyagi. 2013. “Usefulness of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Type I Gastric Carcinoid Tumors Compared with Endoscopic Mucosal Resection.” Hepato-Gastroenterology 60 (126): 1524–29.

59- Kim, Gwang Ha, Jin Il Kim, Seong Woo Jeon, Jeong Seop Moon, Il-Kwun Chung, Sam-Ryong Jee, Heung Up Kim, et al. 2014. “Endoscopic Resection for Duodenal Carcinoid Tumors: A Multicenter, Retrospective Study.” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 29 (2): 318– 24.

60- Suzuki, Shoko, Naoki Ishii, Masayo Uemura, Gautam A. Deshpande, Michitaka Matsuda, Yusuke Iizuka, Katsuyuki Fukuda, Koyu Suzuki, and Yoshiyuki Fujita. 2012. “Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) for Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors.” Surgical Endoscopy 26 (3): 759–63.

61- Choi, Hyun Ho, Jin Su Kim, Dae Young Cheung, and Young-Seok Cho. 2013. “Which Endoscopic Treatment Is the Best for Small Rectal Carcinoid Tumors?” World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 5 (10): 487–94.

62- Eriksson, John, Peter Stålberg, Anders Nilsson, Johan Krause, Christina Lundberg, Britt Skogseid, Dan Granberg, Barbro Eriksson, Göran Akerström, and Per Hellman. 2008. “Surgery and Radiofrequency Ablation for Treatment of Liver Metastases from Midgut and Foregut Carcinoids and Endocrine Pancreatic Tumors.” World Journal of Surgery 32 (5): 930–38. 63- Mazzaglia, Peter J., Eren Berber, Mira Milas, and Allan E. Siperstein. 2007. “Laparoscopic Radiofrequency Ablation of Neuroendocrine Liver Metastases: A 10-Year Experience Evaluating Predictors of Survival.” Surgery 142 (1): 10–19.

64- Glassberg, Mrudula B, Sudip Ghosh, Jeffrey W Clymer, Rana A Qadeer, Nicole C Ferko, Behnam Sadeghirad, George WJ Wright, and Joseph F Amaral. 2019. “Microwave Ablation Compared with Radiofrequency Ablation for Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Liver Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” OncoTargets and Therapy 12 (August): 6407–38.

65- Rinke, Anja, Hans-Helge Müller, Carmen Schade-Brittinger, Klaus-Jochen Klose, Peter Barth, Matthias Wied, Christina Mayer, et al. 2009. “Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Prospective, Randomized Study on the Effect of Octreotide LAR in the Control of Tumor Growth in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Midgut Tumors: A Report from the PROMID Study Group.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 27 (28): 4656–63.

66- Caplin, Martyn E., Marianne Pavel, Jarosław B. Ćwikła, Alexandria T. Phan, Markus Raderer, Eva Sedláčková, Guillaume Cadiot, et al. 2014. “Lanreotide in Metastatic Enteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors.” New England Journal of Medicine 371 (3): 224–33.

67- Pavel, Marianne E., John D. Hainsworth, Eric Baudin, Marc Peeters, Dieter Hörsch, Robert E. Winkler, Judith Klimovsky, et al. 2011. “Everolimus plus Octreotide Long-Acting Repeatable for the Treatment of Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumours Associated with Carcinoid Syndrome (RADIANT-2): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Study.” Lancet (London, England) 378 (9808): 2005–12.

68- Yao, James C., Nicola Fazio, Simron Singh, Roberto Buzzoni, Carlo Carnaghi, Edward Wolin, Jiri Tomasek, et al. 2016. “Everolimus for the Treatment of Advanced, Non-Functional

Neuroendocrine Tumours of the Lung or Gastrointestinal Tract (RADIANT-4): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Study.” The Lancet 387 (10022): 968–77.

69- Raymond, Eric, Laetitia Dahan, Jean-Luc Raoul, Yung-Jue Bang, Ivan Borbath, Catherine Lombard-Bohas, Juan Valle, et al. 2011. “Sunitinib Malate for the Treatment of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors.” New England Journal of Medicine 364 (6): 501–13.

70- Strosberg, Jonathan, Ghassan El-Haddad, Edward Wolin, Andrew Hendifar, James Yao, Beth Chasen, Erik Mittra, et al. 2017. “Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors.” New England Journal of Medicine 376 (2): 125–35.

71- Strosberg, Jonathan R., Robert L. Fine, Junsung Choi, Aejaz Nasir, Domenico Coppola, Dung-Tsa Chen, James Helm, and Larry Kvols. 2011. “First-Line Chemotherapy with Capecitabine and Temozolomide in Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Endocrine Carcinomas.” Cancer 117 (2): 268–75.

72- Fine, Robert L., Anthony P. Gulati, Benjamin A. Krantz, Rebecca A. Moss, Stephen Schreibman, Dawn A. Tsushima, Kelley B. Mowatt, et al. 2013. “Capecitabine and

Temozolomide (CAPTEM) for Metastatic, Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Cancers: The Pancreas Center at Columbia University Experience.” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 71 (3): 663–70.

73- Sun, Weijing, Stuart Lipsitz, Paul Catalano, James A. Mailliard, Daniel G. Haller, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. 2005. “Phase II/III Study of Doxorubicin with Fluorouracil Compared with Streptozocin with Fluorouracil or Dacarbazine in the Treatment of Advanced Carcinoid Tumors: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1281.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 23 (22): 4897–4904.

74- Sorbye, H., S. Welin, S. W. Langer, L. W. Vestermark, N. Holt, P. Osterlund, S. Dueland, et al. 2013. “Predictive and Prognostic Factors for Treatment and Survival in 305 Patients with Advanced Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (WHO G3): The NORDIC NEC Study.” Annals of Oncology 24 (1): 152–60.

75- Yamaguchi, Tomohiro, Nozomu Machida, Chigusa Morizane, Akiyoshi Kasuga, Hideaki Takahashi, Kentaro Sudo, Tomohiro Nishina, et al. 2014. “Multicenter Retrospective Analysis of Systemic Chemotherapy for Advanced Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Digestive System.” Cancer Science 105 (9): 1176–81.

Anexo

Revista Científica da Ordem dos Médicos www.actamedicaportuguesa.com 1

Normas de Publicação

da Acta Médica Portuguesa

Acta Médica Portuguesa’s Publishing Guidelines

Conselho Editorial ACtA MédiCA PORtuguEsA Acta Med Port 2013, 5 de Novembro de 2013

NORMAS PUBLICAÇÃO

1. MISSÃO

Publicar trabalhos científicos originais e de revisão na área biomédica da mais elevada qualidade, abrangendo várias áreas do conhecimento médico, e ajudar os médicos a tomar melhores decisões.

Para atingir estes objectivos a Acta Médica Portuguesa publica artigos originais, artigos de revisão, casos clínicos, editoriais, entre outros, comentando sobre os factores clí-nicos, científicos, sociais, políticos e económicos que afec-tam a saúde. A Acta Médica Portuguesa pode considerar artigos para publicação de autores de qualquer país.

2. VALOReS

Promover a qualidade científica.

Promover o conhecimento e actualidade científica. independência e imparcialidade editorial.

ética e respeito pela dignidade humana. Responsabilidade social.

3. VISÃO

ser reconhecida como uma revista médica portuguesa de grande impacto internacional.

Promover a publicação científica da mais elevada quali-dade privilegiando o trabalho original de investigação (clíni-co, epidemiológi(clíni-co, multicêntri(clíni-co, ciência básica).

Constituir o fórum de publicação de normas de orienta-ção.

Ampliar a divulgação internacional.

Lema: “Primum non nocere, primeiro a Acta Médica Portuguesa”

4. INfORMAÇÃO GeRAL

A Acta Médica Portuguesa é a revista científica com revisão pelos pares (peer-review) da Ordem dos Médicos. é publicada continuamente desde 1979, estando indexa-da na PubMed / Medline desde o primeiro número. desde 2010 tem Factor de impacto atribuído pelo Journal Citation Reports - thomson Reuters.

A Acta Médica Portuguesa segue a política do livre acesso. todos os seus artigos estão disponíveis de for-ma integral, aberta e gratuita desde 1999 no seu site www.actamedicaportuguesa.com e através da Medline com interface PubMed.

A taxa de aceitação da Acta Médica Portuguesa é

apro-ximadamente de 55% dos mais de 300 manuscritos recebi-dos anualmente.

Os manuscritos devem ser submetidos online via “submissões Online” http://www.atamedicaportuguesa.com /revista/index.php/amp/about/submissions#online submissions.

A Acta Médica Portuguesa rege-se de acordo com as boas normas de edição biomédica do international Com-mittee of Medical Journal Editors (iCMJE), do ComCom-mittee on Publication Ethics (COPE), e do EQuAtOR Network Resource Centre guidance on good Research Report (de-senho de estudos).

A política editorial da Revista incorpora no processo de revisão e publicação as Recomendações de Política Edi-torial (EdiEdi-torial Policy Statements) emitidas pelo Conselho de Editores Científicos (Council of science Editors), dispo-níveis em http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/i4a/pages/ index.cfm?pageid=3331, que cobre responsabilidades e direitos dos editores das revistas com arbitragem científica. Os artigos propostos não podem ter sido objecto de qual-quer outro tipo de publicação. As opiniões expressas são da inteira responsabilidade dos autores. Os artigos publica-dos ficarão propriedade conjunta da Acta Médica Portugue-sa e dos autores.

A Acta Médica Portuguesa reserva-se o direito de co-mercialização do artigo enquanto parte integrante da revis-ta (na elaboração de separarevis-tas, por exemplo). O autor de-verá acompanhar a carta de submissão com a declaração de cedência de direitos de autor para fins comerciais. Relativamente à utilização por terceiros a Acta Médica Portuguesa rege-se pelos termos da licença Creative Com-mons ‘Atribuição – uso Não-Comercial – Proibição de Rea-lização de Obras derivadas (by-nc-nd)’.

Após publicação na Acta Médica Portuguesa, os auto-res ficam autorizados a disponibilizar os seus artigos em repositórios das suas instituições de origem, desde que mencionem sempre onde foram publicados.

5. CRItéRIO de AUtORIA

A revista segue os critérios de autoria do “international Commitee of Medical Journal Editors” (iCMJE).

todos designados como autores devem ter participado significativamente no trabalho para tomar responsabilidade