Repositório ISCTE-IUL

Deposited in Repositório ISCTE-IUL:

2018-07-10

Deposited version:

Post-print

Peer-review status of attached file:

Peer-reviewed

Citation for published item:

Delgado, M. J. & Almeida, I. D. (2018). Towards artistic education with textiles: a sustainable challenge with K-10 children. In Gianni Montagna, Cristina Carvalho (Ed.), Textiles, Identity and Innovation: Design the Future: Proceedings of the 1st International Textile Design Conference (D_TEX 2017), November 2-4, 2017, Lisbon, Portugal. Lisboa: CRC Press.

Further information on publisher's website:

https://www.crcpress.com/Textiles-Identity-and-Innovation-Proceedings-of-the-1st-International/Montagna/p/book/9781138296114

Publisher's copyright statement:

This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Delgado, M. J. & Almeida, I. D. (2018). Towards artistic education with textiles: a sustainable challenge with K-10 children. In Gianni

Montagna, Cristina Carvalho (Ed.), Textiles, Identity and Innovation: Design the Future: Proceedings of the 1st International Textile Design Conference (D_TEX 2017), November 2-4, 2017, Lisbon, Portugal. Lisboa: CRC Press.. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with the Publisher's Terms and Conditions for self-archiving.

Use policy

Creative Commons CC BY 4.0

The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes provided that:

• a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in the Repository • the full-text is not changed in any way

The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Serviços de Informação e Documentação, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL)

Av. das Forças Armadas, Edifício II, 1649-026 Lisboa Portugal Phone: +(351) 217 903 024 | e-mail: administrador.repositorio@iscte-iul.pt

1. INTRODUCTION

Textile arts in Portugal date back to ancient times but it was in the 16th century that the field of handi-crafts and textile fabrics made from wool, cotton, linen and silk grew considerably. The first domestic and family enterprises for wool wooling, fabric fin-ishing and weaving sprang up in the weavers own homes (Sendim, 2005).

The beginning of textile industrialization triggered the transition from handicraft to mass production. In Portugal, as in other parts of Europe, this also oc-curred in the late eighteenth century and the textile industry grew significantly during the Industrial Revolution. The demand for cloth grew, so brokers had to compete with others for the supplies to make it. This created a problem for the consumer because the manufactured products cost more. The solution was to massify production with the type of machin-ery that connected multiple spinning so that up to eight threads could be processed at once, and led to the use of water-powered cotton mills and mechani-cal looms (Pereira, 2017).

However, even though mechanization played an undeniable role in increasing production and profits in the textile sector, resistance to the technological revolution - the default position of many Portuguese companies - was a major constraint to production and innovation. Changes were postponed until the mid-19th century, and only then was there a

signifi-cant increase in the production and development of the textile, cotton and wool industry. The use of electrical power facilitated the establishment of spinning and weaving mills in towns and cities in the Minho region in northern Portugal. This occurred mainly in the Rio Ave valley, where there had been an ever-growing number of women workers from before the mid-nineteenth century onwards. As a re-sult, the region became the country’s textile hub. Be-tween 1881 and 1917, the Portuguese textile sector concentrated the largest number of unskilled workers in companies engaged in the wool, cotton, jute, linen and stamping industries.

While the factories brought benefits in the way of automation and mass production, they also brought the social ills and hardships associated with child la-bour and poor workplace safety, which led to lala-bour protests. By the beginning of the 20th century, the industry was still in growth mode, establishing its centre of operations in the centre and northeast of Portugal.

Although some periods of major competitive shocks have been overcome in textile and clothing companies, the current socio-economic conditions continue to pose great challenges for them. In pursuit of dynamic competitive advantages, as promotors of sustained growth, companies are now developing new activities and new ways of doing things. Tech-nical expertise, creativity, technological innovation, new fashion business models and the internalization of companies play a fundamental role in their future

Towards Artistic Education with Textiles: a sustainable challenge with

K10 children

Delgado, M.J.

1,2& Almeida, I.D.

2,31University of Lisbon, Faculty of Architecture; 2CIAUD, Portugal; 3ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon

ABSTRACT: Making art with textiles has become part of the development process of creative potential that has led to the acquisition of different types of skills strongly correlated to the success of the textile and clothing industry. There are objectives defined in the curricula of basic education and pre-school education (K10 children) that tackle the artisanal process of transforming raw textile materials: these include acquiring knowledge of textile materials, highlighting the importance of handicrafts in culture and heritage, textile arts and the development of fine motor skills. The objective of this study is to learn about the practices of K10 children using textiles in schools, and to understand how these practices contribute to the development of their creative potential with regard to the area of textiles and clothing. Integrating the activities with textiles makes sensitization to the materials and techniques of the textile arts possible, and paves the way for greater sustain-ability of this sector in Portuguese society.

Keywords: Textiles; Sustainable Artistic Education; Skill’s development; Challenge in Education; Learning Meth-ods

projections. Nowadays, the textile sector is a hub of constant discovery through smart solutions. From Citeve (1990) to Cilan (1992) to Cenit (2009), sev-eral research and development centres are working towards bringing together smart technologies and clothing (ATP, 2016).

The textiles and clothing sector should not only be brought up to date as far as technology, tech-niques and design are concerned, but it must also in-vest in training and management. As globalisation occurred more quickly in clothing than in textiles, it is up to the latter to respond as soon as possible.

In this innovation paradigm, the textile sector is a critical area, one that is playing an ever-greater role in Portuguese business and the country’s economy. It represents 10% of all Portuguese exports and 20% of Industry employment, making it dynamic and competitive in European and world markets (ATP, 2016).

Increased knowledge of skills in human re-sources, alongside a sustained dynamic textile pro-duction, highlight the importance of specialized training in the textile and clothing sector, not only in the fields of technology, innovation, processes and textile materials, but also in the areas of manage-ment and production planning. Hereafter, the design and creation of new products with high value, in ad-dition to innovation and creativity, will depend on a renewed workforce whose professional training and qualification should have strong inputs of an artistic, scientific and technological nature, as justified by the purposes and contents of the curricula of higher edu-cation in this area.

Art has never been so much part of the textile world as it is today, and the reasons for this are founded in a constant exchange between schools, exhibitions, studios and shops.

In response to such demands, art education as-sumes an important position. The arts become part of the development process of creative potential, leading to the acquisition of different types of skills essential to the success of the textile and clothing in-dustry.

The history of childhood education in Portugal reveals that a set of aesthetic experiences were in-cluded in the aesthetic education of children and young people, and that they were based on guide-lines drawn up by the Congress of Drawing of 1900 (Oliveira, 1996). They were implemented particular-ly through manual techniques using different materi-als, among which were textiles.

At present, there are objectives defined in the cur-ricula of basic education and pre-school education that tackle the artisanal process of transforming tex-tile raw materials. These include acquiring knowledge of textile materials, understanding the processes and technologies, awareness of biodiversi-ty as well as environmental awareness, the

im-portance of handicrafts in culture and heritage, tex-tile arts and the development of mobility.

The integration of activities making use of tex-tiles makes sensitization to the materials and tech-niques of the textile arts possible, and paves the way for innovative and qualified companies to maintain the sustainability of this sector in Portuguese society (ATP, 2016).

The objective of this study is to learn how textiles are being used in children's artistic education, and to understand how these practices contribute to the de-velopment of creative potential in these children with regard to the area of textiles and clothing.

2. OUTCOMES OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 The use of textiles in children’s artistic education in Portugal: an historical overview The projects and reforms that characterized the vari-ous periods of children’s education in Portugal were always associated with social values, political and religious ideologies, and the technological advances that have marked society. At the same time, media-tion between family and school has always main-tained a close relationship, combining affective val-ues with the technical and scientific valval-ues of education (Magalhães, 1997).

i) Early modern period – ca. 1500 to mid-18th Going back to the 16th and 18th centuries, sover-eignty of the Companhia de Jesus, whose objectives were to develop the intellectual, physical and moral capacities of children and young people greatly in-fluenced educational action in Portugal and Europe. This was a schooling plan based on the robust pro-gression of development and knowledge (Gomes, 1995).

ii) Late modern period – after mid-18th to WW2 In the second half of the eighteenth century, with the extinction of the Companhia de Jesus in 1759 and inspired by Illuminist thought, the Marquês de Pom-bal, First Minister of King D. José I, undertook two major reforms - one in 1772 and the other in 1795 - that marked the domain of government action in ed-ucation. These reforms influenced both the programs and the enlargement of the primary and secondary school systems, with "Minor Schools" opening throughout the country (Gomes, 1995). As far as higher education is concerned, a project was initiated with the general aim of drawing up a proposal to change the programmatic and methodological con-tents of the University of Coimbra, and to create the Faculties of Medicine and Mathematics. It was a modernization of education in Portugal that placed it alongside Europe's education systems of the time.

However, any content related to the teaching of the arts was still non-existent.

Later, in the reign of D. Maria I (from 1777 to 1815), other changes were made in educational poli-cy, which was marked by the return of religion to public education, along with approval for private schools to be opened. In 1815, and in the context of the social problems arising from the earthquake of 1755, the institution Real Casa Pia de Lisboa was founded. This institution promoted teaching females for the first time, with the opening of "girls' schools" (Oliveira, 1996).

Also in the reign of D. Maria I, measures were adopted that contributed to the progress of the sci-ences and the teaching of the arts in Portugal. The most representative in Lisbon include the constitu-tion of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon (1779) and the Aula (1781), as well as the opening of the Drawing Class of Casa Pia and the Academy of Nudes, both in 1780.

In Oporto, the Public Classroom of Debux and Drawing was inaugurated in 1779 and it is consid-ered the pioneering national institution in organized and systematic artistic teaching. Moreover, in 1860, high schools officially implemented the teaching of drawing, and only a few decades later, art education was included in trade curricula (Nóvoa, 1994; Lis-boa, 2007).

The Liberal Revolution in 1820 was a starting point for major reforms in education. Those in pow-er, recognizing how far behind public education was regarding the challenges of scientific progress, indi-cated the need for major educational changes; point-ing out that these changes should be suitable to pre-pare students, at scientific and practical levels, for careers in agriculture, industry and commerce (Pu-lido Valente, cit. by Ó, 2009).

The General Regulation of Primary Education was an outcome of the first major reform of the con-stitutional regime. This occurred in 1836, and se-cured provision of free public primary education for all. A few years later, this reform also covered sec-ondary and university education. It was ” the first of-ficial document that systematized secondary educa-tion, integrating curricular, pedagogical and administrative aspects” (Ó, 2009, p.17). Also note-worthy is the work of Almeida Garrett who, defend-ing the role of the arts in education, inaugurated the National Conservatory in Lisbon in 1836, to promote the teaching of the arts.

The year 1888 marks the creation of the women's lyceums. With the creation of these secondary schools, a curriculum for the training of young peo-ple was defined and impeo-plemented. The main goals were to develop specific competences that could lead either to the pursuance of university studies or to en-tering the world of the work. This was the end of “the false distinction between education and

school-ing, between theoretical and utilitarian teaching” (Coelho, cit. by O, 2009, p.16).

Between 1862 and 1886, schools for training teachers of primary education appeared for the first time. In Lisbon and Oporto, Commercial and Indus-trial Schools, and IndusIndus-trial Design Schools were created, marking the beginning of a special tech-nical, theoretical and practical education to prepare citizens to respond to the industrial growth needs of the country.

With regard to pre-school education, Law Nº 1106 was passed in 1880 to encourage the creation of educational institutions that would support prima-ry schools by taking in children from three to six years old and provide them with structured and con-sequential educational plans (Magalhães, 1997).

In addition to that, in 1882, the first Froebel Kin-dergarten, which followed the pedagogical currents of Europe was set up by public initiative. In the same year, the Association of Mobile Schools whose aim was to teach children literacy was created, with the wider objective being to combat illiteracy among the Portuguese population. (Cardona, 1997; Gomes, 1977, Magalhães, 1997). To achieve this goal, the João de Deus Method, one of the most effective types of material and texts ever designed to teach lit-eracy and develop reading fluency, was created (Magalhães, 1997; Rodrigues, 2014). This associa-tion proposed “to establish nursery schools or school gardens for children from 3 to 7 years of age, where the spirit and doctrine of the educational work of Jo-ão de Deus would be applied in its entirety, thus modifying the Portuguese type of nursery schools” (Gomes, 1977, p.51). The evolution in pre-school education is highlighted in the 1896 Children's Schools Regulation which, strongly influenced by the pedagogical conceptions of Froebel, Montessori, Décroly, among others, presented a program based much more on the integral development of children than on "instruction".

In the early years of the Republic (1911), and with the participation of pedagogues João de Barros and João de Deus, a comprehensive reform of the basic education system was designed, which includ-ed includ-education for children between 4 and 7 years of age. Hence, the first kindergartens were set up. These were private schools for children's education, with innovative pedagogical methods to promote sensory education, the acquisition of hygiene habits, working methods and learning (Cardona 1997).

The multiplicity of reforms initiated during liber-alism, and continued in the Republic, definitively marked the educational panorama in Portugal, with the highlight being the creation and autonomy of the University of Lisbon and Oporto (OEI – Ministério da Educação de Portugal, 2003).

The Estado Novo, which prevailed in Portugal from 1926 to 1974, made great changes in the educa-tional system and was sustained by a new political

and moral ideology. The official closure of public pre-school education in 1937 resulted in a sharp de-cline in early childhood education, (Cardona, 1997).

However, the history of children's education was always tied to family history and the history of women, and early childhood education was once again deemed the responsibility of the family and of an institution designated Work of Mothers for Na-tional Education. This institution, created in 1936, took on official responsibility for pre-school educa-tion and its role was "to stimulate the educaeduca-tional ac-tivities of the Family", "to ensure cooperation be-tween the Family and the School" and "to better prepare the female generations for their future ma-ternal, domestic and social duties" (Pimentel. 2011, p. 211).

In 1939, one single book for Elementary School learning was approved. The drawing activities at this level of education were not considered an autono-mous discipline that had objectives, competencies and defined content (Oliveira, 1996). Rather, it was considered an activity that supported themes devel-oped in other areas of knowledge through graphic records. In the context of aesthetic education for children and young people, the academic programs up to the 40s reflect the guidelines drawn up at the Congress of Drawing in 1900. These promoted de-veloping a capacity for observation and reproduction through freehand drawing, as well as the practice of invention and geometric drawing, which were both associated with decoration.

By 1942, regulation of Schools of the Primary Magisterium had been adopted, and teachers were taught to train students to memorize the representa-tion of the objects they drew from sight. The incor-poration of this exercise in the student assessment at the end of the first grade studies was a pre-requisite for access to high school. Simultaneously, the clas-ses of feminine courclas-ses promoted an aesthetic educa-tion, with the sole purpose of preparing those stu-dents for their future working life (Oliveira, 1996).

iii) Contemporary history – from 1945 to the present

In the field of artistic education, the influence of Herbert Read's theory is renowned. In his work Edu-cation Through Art, he takes up the foundations of Plato's doctrine defending that art should be the basis of education and that "every person is a proper type of artist" (Oliveira, 1996, s/p.). The first guidelines for the introduction of art into the educational pro-cess, based on the merging of all forms of artistic expression, lead to an education of the senses, that is, an aesthetic education, which should form the ba-sis of a broad conception of mans’ formation.

This influence is reflected in the creation of sev-eral centres for children's art and children's art exhi-bitions, and through the work developed by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (CGF). The CGF

also designed and support (motivationally and finan-cially) a number of pilot projects at pre-primary level such as the training and professional qualification of young people in art abroad. Similarly, the Children's Art Centers were implemented in partnership with the educational services of several museums. At this time, children's artistic education is marked by the action of Cecília Menano and João Couto, who founded the School of Art in 1949 to promote free expression in Cultural Education of children.

In the first cycle of the Technical School, the drawing program (1947) included the development of the following skills: observation, reproduction, interpretation, imagination and decoration, promot-ing manual work, free drawpromot-ing, and geometric and decorative design. In 1948, Free Drawing became part of the official program of the lyceums, support-ed by the "Compendium of drawing for the first cy-cle of Lyceums" (Oliveira, 1996).

In 1959, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, and this provided the momentum for a turning point in the artistic education of children and young people in Portugal. However, up until the 1970s, artistic output in public schools was no more than choral singing, drawing, and handicrafts.

In the following years, some structural phenome-na appeared that marked education and Art educa-tion in Portugal. Worth meneduca-tioning here is the rele-vance of the role played by Minister Veiga Simão's School System Reform Project (1971). This pro-ceeded to definitively reintegrate public pre-school education into the educational system as a preparato-ry phase for school education (Gomes, 1977), and al-so led to the approval of 8 years of free basic school education. In tandem with this reform, which simul-taneously tackled the artistic education of children, in 1971-72 the Training Course for Teachers of Art Education at the National Conservatory contributed to the aesthetic and artistic education of children (Oliveira, 1996).

In the period after April 25 1974, educational pol-icies were redefined in accordance with the socio-cultural orientations of the Revolution that were based on the principle of promoting equal opportuni-ties. The expansion of the public network of kinder-gartens was to ensure the education of children from the age of three (Vasconcelos, 2015). In the field of art education, the prevalence of posters and murals inspired by the Revolution led to the promotion of graphic communication in schools, as well as to the introduction of cartoon work.

In the first Cycle of Basic Education, new cur-ricula that integrate the artistic areas were drawn up; namely, Plastic Expression, Movement, Music, and Drama. While this emerged from the principles of integrative aesthetics, Visual Education in the sec-ond and third Cycles of Basic Education, which ex-tends to the 9th year of schooling, was oriented

to-wards aesthetics and communication, with a strong focus on cultural values (Sousa, 2003).

Within this field of changes in educational poli-cies, the Framework Law on Pre-School Education (OCEPS), published in 1977, reinforced the im-portance of this level of education and its integration into the basic education system.

In that period, artistic education at various levels of the education system was encouraged through the implementation of various projects and actions, in particular, the CAI and ACARTE (Service of Ani-mation, Artistic Creation, and Education through Art), and with the development of artistic activities and projects for children, educators, and the commu-nity.

In 1986, with the publication of the Basic Law of the Educational System in Portugal (LBSE), and with the changes introduced successively in 1997, 2005 and 2009, a review of the structure of the edu-cational system was undertaken to identify im-provement opportunities and to ensure a higher qual-ity education that would integrate aesthetic values into the curriculum (Sousa, 2003).

In the context of this evolution, the relationship between knowledge and expertise; between theory and practice; and between manual activities and ar-tistic education, are some of the dimensions that are valued in this curriculum and are considered essen-tial both for social integration and for the education-al success of students. Art became part of the curric-ula at the Pre-school and Basic Education levels, and is definitely accepted as a disciplinary area capable of promoting the development of the capacity for expression, the creative imagination and various forms of aesthetic expression, among others.

In the report of the study "Basic Knowledge of All Citizens in the 21st Century", the National Council for Education (2004) highlights the four pil-lars of education for the 21st century namely: (i) learning to know, i.e., acquiring the instruments of understanding; ii) learning to do, in order to act on the environment; (iii) learning to live together, in or-der to participate and cooperate with others in all human activities; and iv) learning to be, an essential means to integrate the previous three (UNESCO, 1996). In this report, the emphasis is on Basic Edu-cation, which is the level of education that, aimed at all citizens, is directed towards a curricular approach focused on the competences that lead to an active citizenship (Cachapuz, 2004).

2.2 Artistic languages presently in the overall Curriculum Guidelines and in the Program of the 1st cycle of Basic Education

The Pre-primary Education Curriculum Guidelines in 2016 consider pre-school education as fundamen-tal to the progress of each child's skills and learning in the transition to the first cycle, as well as "the first

stage of basic education in life" (Silva, Marques, Mata & Rosa, 2016, p. 5).

In this sense, educational intentionality is charac-terized by the construction and management of a cur-riculum that includes strategies adapted to a social context involving different actors (children, educa-tors, parents, family, professionals), and that facili-tates communication and articulation with the com-munity.

The relationships and interactions established be-tween the different players in the educational pro-cess, from a systemic and ecological perspective, are essential for the development of this process. It is in this interaction with the various contexts that the child, establishing a continuity between play and learning, gets to know new forms and artistic lan-guages that help them understand and represent the physical, social and technological world around them (Silva et al, 2016).

By playing and communicating with others, the child is not only appropriating new concepts through exploration and experimentation of the surrounding environment, but is also developing learning in the different content areas in an integrated and global way. The appropriation of multiple artistic languages allows the child to interact with others, express thoughts and emotions in a proper and creative way (Silva et al, 2016).

This approach to different artistic and cultural manifestations leads to the development of creativi-ty, symbolic representation, and aesthetic sense. Therefore, children are encouraged to experiment, to perform and to create, to develop their capacity for expression, observation, appreciation and the trans-mission of ideas.

Artistic learning and making in the children's ed-ucational curriculum can be enhanced by the explo-ration and use of different materials and techniques. Activities carried out with various fabrics, papers, textures, paints, pencils, moldable materials, natural objects and recyclable materials, among others, lead to the development of creativity and meaningful learning.

Also, the multiplicity and diversity of materials that can be used, like waste materials for example, means they can be integrated into different activities and acquire new functionalities and meanings through their construction and deconstruction, and thus further help develop divergent and creative thinking.

Nevertheless, it is possible to even further en-hance all this learning through understanding in the cultural and artistic context, with the implication of processes of observation, analysis and critical judg-ment. The approach to artisanship is a very im-portant cultural aspect of children’s education, not only for producing art but also in the acquisition of traditional knowledge concerning its use, the ethical dimensions, the family stories and traditions; all of

which can be exploited by making the interconnec-tion between different aspects of knowledge.

As Sousa affirms, "all experiences that take place in the field of arts education will be a source of knowledge, but also a source of connection and en-richment among peoples and cultures around the world” (2008, p.41).

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 The drawing up and application of the Research Instrument

From the reading of both the first cycle teaching programs and the OCEPS, we came up with a ques-tionnaire survey. The main goal was to seek infor-mation about teachers’ perceptions of the adequacy of textile art in the education of children. The ques-tionnaire was limited to 5 groups of differentiated but interconnected questions, as follows: i) socio-demographic characterization of the sample; ii) iden-tification of techniques and materials related to the textile arts that are used in an educational context; iii) perception of the relevance of the use of these techniques and materials in the acquisition of skills and abilities essential for the development and train-ing of children; iv) demonstration of the interdisci-plinary dimension of textiles; and v) recognition of the importance of including activities with textiles in pedagogical practice.

This questionnaire was structured using closed questions, which included questions adapted from the Likert scale with four levels of response, and di-chotomous questions. In this way, respondents would comment on the proposals presented, and classify them accordingly, with (1) being not at all relevant and (4) being very relevant. The option of I don’t know/I can’t answer (n/s; n/r) was also includ-ed.

3.2 Data collection

A total of 48 public and private schools from the Primary Education Cycle in the Lisbon area com-prised the deliberately non-probabilistic sample. The teachers responded in all of them. Data were collect-ed from several responses after 48 online survey submissions.

The results coming from descriptive statistical analysis were sufficient to define a very first ex-ploratory definition of textile utilization in the artis-tic education with textiles.

4. RESULTS ANALYSIS i) Profile of respondents

The sample consisted mostly of women (99%), and all the answers were considered valid. Regarding the age group, 50% of respondents were between the

ag-es of 21 and 40, 10% were between 41 and 50 years and 40% were over 50 years.

With regard to academic training, 54% of the sample had a master's degree, 29% had a degree, 9% had a bachelor’s degree, and 8% had a PhD. The doctoral degree belonged to teachers aged over 31 years. None of the teachers revealed any specializa-tion or training in the field of fine arts.

ii) Techniques and textile materials used in an educational context

Although in this exploratory survey, the data were quantitative, the analysis was qualitative because sta-tistical significance was not addressed. Therefore, the average values registered in the graphics may on-ly be interpreted in a qualitative way.

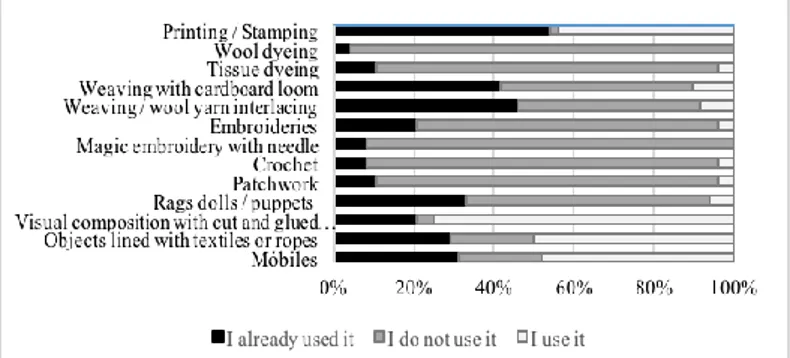

Understanding the teachers’ perceptions of expe-rience using techniques and materials related to the textile arts in an educational context, as shown in figure 1, was an important driver for future im-provement of textile utilization in an educational context, as the survey applied to the teachers’ sample shows.

Figure 1 – Techniques and textile materials used in an educa-tional context

After analysing these results (Figure 1), it is evi-dent that the teachers, in general, do not use textile manufacturing and transformation techniques, such as weaving, embroidery, and dyeing of textile mate-rials during their pedagogical practice. Only printing, and stamping on fabrics with rubber stamps are ac-tivities that approximately half of these teachers in-tegrate into their classes.

The findings highlight that textile activities gain expression only when they complement or support other techniques, such as the creation of composi-tions, mobiles, and stamps, among others.

iii) Acquisition of skills and abilities through textiles

We also studied the relevance of using these materi-als and techniques in an educational context. Thus, based on the objectives defined in the programs and curricular guidelines, the respondents were presented with a set of recognized skills and abilities that can

be developed through accomplishing activities based on textiles.

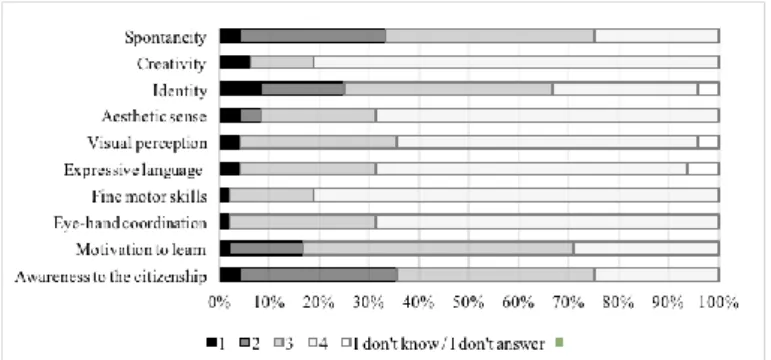

Figure 2 – Teachers’ perception of children’s acquisition of skills and abilities through textile utilisation

From our reading of the results presented in Fig-ure 2, teachers’ perception about the contribution of the materials and textile techniques associated with both sensitization and artistic education was deemed, by the majority of respondents, to be relevant or very relevant.

Materials, plasticity of materials, textures, and patterns, as well as techniques and technologies of textiles were also valued by the great majority of re-spondents as vehicles for promoting creativity, aes-thetic sense, and visual perception. Also valued were the multiplicity of expressions revealed in embroi-dery, tapestries, crochet, and knitting, among others. Just slightly more than 50% of respondents con-sidered that the traditional matrix of knowledge and knowledge associated with textiles, materials and ancestral techniques lent added value to an identity and awareness of citizenship, as well as to the theme of encouraging learning.

Activities related to the field of textile materials were highlighted by more than 90% of the respond-ents as a privileged opportunity to promote the ac-quisition of skills overall, and those associated with motor skills, namely manual eye coordination and fine motor coordination.

iv) - The interdisciplinary dimension of textiles From the perspective of integration of the different areas of expression and communication, it has been interesting to learn how the activities with textiles in classes participate and contribute to the creation of interdisciplinary work or activities (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - The interdisciplinary dimension of textiles in classes.

As shown in Figure 3, the art of textiles it is an activity that it is not promoted by these teachers. However, the specific materials and techniques of this art are used and reinvented to adapt to interdis-ciplinary contexts, such as creating garments for car-nival or to illustrate stories, among others.

v) - Inclusion of textiles in pedagogical practice Finally, it should be pointed out that almost all the respondents (99%) were peremptory in their af-firmative answer regarding the importance of includ-ing activities with textiles in their pedagogical prac-tice.

5. DISCUSSION AND FINAL REMARKS The literature review carried out in this study on children's artistic education evidenced that for sever-al decades in Portugsever-al, this dimension was not part of the curricular design of the educational system. Only in 1986, was art officially accepted as an im-portant factor for the integral formation of the indi-vidual, with its inclusion in the educational system, namely in pre-school education and basic education (Sousa, 2003).

In the analysis of current school programs, the ability to respond to certain tasks, involving cogni-tive, social and emotional abilities, shows there is a need for guidance to support training in the devel-opment of skills.

Acquisition of these skills, which is not exhausted in each cycle of study, but progresses throughout the education and training of each individual, begins early in childhood and progresses throughout life, in a constant endeavour to expand knowledge and skills.

Competencies such as these are considered fun-damental for the profitable promotion of a society oriented towards innovation and quality, and one in which knowledge and expertise are associated with knowing how to be and knowing how to do.

It is within this set of competencies that the tex-tile arts fit with regard to contributing towards de-veloping different forms of expression and commu-nication, as well as motor skills; thus giving meaning to the educational effort assumed by the teachers interviewed. Simultaneously, the textile arts can enhance the development of aesthetic sensibility, abstract thinking, creativity, and self-esteem; all of which contribute to the integral formation and con-struction of citizenship.

The empirical study showed that when associated with other activities, the textile arts are one of the main pedagogical strategies of these respondents, by allowing the child to create, communicate and ex-press themselves in different ways and in various contexts. The creation of carnival props and

cloth-ing, and other interdisciplinary activities highlights the close relationship of these materials and tech-niques with the emotional, sentimental and cognitive development of the child (Sousa, 2003).

Nevertheless, while textiles were understood as being a vehicle for children's artistic learning and sensibility through raising awareness of and bringing them closer to different artistic expressions, materi-als, techniques, and technologies, we realized that the activities associated with textiles, are currently very little implemented. It can even be observed that the specific activities of weaving and dyeing materi-als have fallen into disuse, despite the appreciation they received from almost all the respondents re-garding their inclusion in pedagogical practices.

This discussion highlights the confrontation be-tween the pedagogical intentionality of activities with textiles and practices that have been devalued. It is the devaluation of these practices that has closed the field of discovery for textiles as an art form.

In short, this study helps us to understand the dis-courses produced regarding children’s education. In addition, it allows critical reflection on the nature of knowledge considered essential in the process of de-veloping citizens in a society oriented towards the development and creation of innovative and quali-fied companies in the area of textiles.

Currently, with the strong resurgence of the tex-tile and clothing sector in Portugal, the critical re-flection that this study brings may contribute to the debate on the methodological orientations in K10 teaching.

REFERENCES

ATP (Eds)( 2016). Fashion from Portugal. Diretório 2016. Vi-la Nova de Famalicão: Multitema.

Cachapuz (2004). Saberes Básicos de todos os cidadãos do

Séc. XXI. Lisboa: CNE.

http://www.cnedu.pt/pt/publicacoes/estudos-e- relatorios/outros/793-saberes-basicos-de-todos-os-cidadaos-no-sec-xxi.

Cardona, M.J. (1977). Para a história da educação em

Portu-gal: O discurso oficial (1834-1990). Porto: Porto Editora.

Gomes, J. (1977). A educação infantil em Portugal. Coimbra: Almedina.

Gomes, J. (1995). Luís António Verney e as Reformas Pomba-linas do Ensino. In J. Gomes (ed.), Para a História da

Edu-cação em Portugal-Seis estudos. Porto: Porto Editora.

Lisboa, M. H. (2007). As Academias e Escolas de Belas Artes e

o Ensino Artístico (1836-1910). Lisboa: Edições Colibri.

Magalhães, J. 1997. Para uma história da educação de infância em Portugal. Saber (e) Educar, (2): 21-26.

Nóvoa, A. (1994). História da educação. Lisboa: Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação.

Ó, J. R. (2009). Ensino Liceal (1863-1975). Lisboa: Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação.

OEI: Ministério da Educação de Portugal (2003). Breve

Histó-ria do Sistema Educativo.

http://www.oei.es/historico/quipu/portugal/

Oliveira, E. 1996. In Pais, N. & Correia, L. (Coord). Educação

arte e Cultura. Lisboa: FCG.

Pereira, A.S. 2017. A indústria têxtil portuguesa. Lisboa: Clube do Colecionador - CTT.

Pimentel, I. (2011). A cada um o seu lugar, a política feminina

do Estado Novo. Lisboa: Editoras Temas e Debates.

Rodrigues, M.L. (org) (2014). 40 anos de politicas de

educa-ção em Portugal. Coimbra: Almedina.

Sendim, B. 2015. Breve história da indústria têxtil. Da idade

média à industrialização. Famalicão: ATP- Associação

Têxtil e Vestuário de Portugal.

http://www.atp.pt/fotos/editor2/ATP_Brochura_Comemorat iva_50_Anos.pdf

Silva, I. Marques, L., Mata,L.,& Rosa, M.(2016). Orientações

Curriculares para a Educação Pré-escolar. Lisboa: DGE.

Sousa, A. (2003). A Educação pela arte e artes na Educação:

Música e artes plásticas. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

Sousa, M. R. (2008). Música, educação artística

intercultura-lidade a alma da arte na descoberta do outro. Tese de

Doutoramento em Ciências da Educação. Lisboa: Universi-dade Aberta.

Vasconcelos, T. (2015). Percursos da Educação Pré-Escolar

em Portugal: recuperar a memória. Encontro Educação Pré-Escolar.

www.fenprof.pt/Download/FENPROF/SM_Doc/Mid.../Fen prof_jan2015.pptx