w w w . e l s e v i e r . p t / r p s p

Original

article

Efficiency

and

equity

consequences

of

decentralization

in

health:

an

economic

perspective

Joana

Alves

a,∗,

Susana

Peralta

b,

Julian

Perelman

aaEscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública,UniversidadeNovadeLisboa,Lisboa,Portugal bNovaSchoolofBusinessandEconomics,UniversidadeNovadeLisboa,Lisboa,Portugal

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received17September2012 Accepted21January2013 Availableonline10July2013

Keywords: Decentralization Efficiency Equity Healtheconomics Incentives

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Overtherecentyears,decentralizationhasbeenadoptedinmanyhealth systems.The questionhoweverremainsofwhetherlocalactorsdobetterthanthecentralgovernment. Wesummarizethemaininsightsfromeconomictheoryontheimpactof decentraliza-tionanditsempiricalvalidation.Theorysuggeststhatthedecisiontodecentralizeresults fromatrade-offbetweenitsadvantages(likeitscapacitytocatertolocaltastes)andcosts (likeinter-regionalspillovers).Empiricalcontributionspointthatdecentralizationresultsin betterhealthoutcomesandhigherexpenditures,resultinginambiguousconsequenceson efficiency;equityconsequencesarecontroversialandaddresstherelevanceofredistribution mechanisms.

©2012EscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.Allrights reserved.

Consequências

em

eficiência

e

equidade

da

descentralizac¸ão

na

saúde:

uma

perspetiva

económica

Palavras-chave: Descentralizac¸ão Eficiência Equidade Economiadasaúde Incentivos

r

e

s

u

m

o

Apesardemuitossistemasdesaúdeteremoptadorecentementepeladescentralizac¸ão, ficapor esclarecer seos governoslocaistêm um melhordesempenho doqueos cen-trais.Esteartigosumarizaosprincipaisresultadosdateoriaeconómicasobreoimpactoda descentralizac¸ãoeasuavalidadeempírica.Adecisãodedescentralizarresultaduma arbi-tragementreasvantagens,comoaadaptac¸ãoàspreferências,eosinconvenientes,comoas externalidadesinter-regionais.Osestudosempíricossugeremqueadescentralizac¸ão per-miteganhosemsaúdemastambémdespesasmaiores,comconsequênciasambíguasem termosdeeficiência,equeasconsequênciasparaaequidade,sendocontroversas,indicam arelevânciadosmecanismosderedistribuic¸ão.

©2012EscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.PublicadoporElsevierEspaña,S.L.Todosos direitosreservados.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:joana.alves@ensp.unl.pt(J.Alves).

0870-9025/$–seefrontmatter©2012EscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.Allrightsreserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsp.2013.01.002

rev portsaúde pública.2013;31(1):74–83

75

Introduction

Overtherecentyears,decentralizationhasbeenoneofthe mainreformsadoptedinmanyhealthsystems.Strong deci-sion power of sub-central governments already existed in Scandinavian counties and in federal states like Canada, SwitzerlandandAustralia1;themostrecentdevolution

pro-cesseshavebeenobservedinNHSsystems,namelyinSpain andItaly(towardregions),andtheUK (towardWales, Scot-land,NorthernIreland).Inafewwords,moredelegation to localauthoritieswasexpectedtoimprove servicesthrough a combination of better knowledge oflocal needs, prefer-encesandproviders’characteristics,higheraccountabilityof policy-makersandefficiency-enhancingcompetitionamong jurisdictions.

These expected benefits are however far from obvious and the major question forpolicy-makers and researchers remains,that is,whether localactorsreallydobetterthan thecentralgovernment.Putdifferently,theissueiswhether decentralizationallowsfortheprovisionofbetterand equi-table health services to all citizens at an acceptable cost. Oates2wasthefirstonetosuggestthatthedecisionto

decen-tralizeresultsfrom atrade-offbetween itsadvantagesand costs.Whetherthebenefitsactuallyoutweighthecosts–the efficiency issue – is ultimately an empirical question. The literaturehas mainly focusedon overall efficiency by esti-matingtheimpactofdecentralizationoneconomicgrowth.3,4

Anotheralternativeistomeasuretheimpactof decentraliza-tiononsectoralpolicies.5Decentralizationofhealthpolicies

isrelativelyrecent;theliteratureisstillscarceandoften pro-videscontradictoryresults.Wesummarizethemaininsights fromeconomictheory ontheimpactofdecentralizationof healthpolicies, and wereview empiricalstudies that have testedsomeofthesetheoreticalassumptions.

Institutional

context

Decentralization in health care can adopt many different forms.Followingthetypology proposedbyVrangbaek,6our

maininteresthereisindevolutionorpoliticaldecentralization, throughwhichpoweris“decentralizedtolower-levelpolitical authoritiessuchas regionsor municipalities”.Other forms ofdecentralizationare also possiblewhich are beyondthe scopeofthepresentpaper.De-concentrationand bureaucra-tizationinvolvetransfersbetweenadministrativelevelsand frompoliticaltoadministrativelevel,respectively(thinkfor exampleinthePortuguesecontext,oftransferofcompetences toRegional HealthAuthorities).Decentralizationalsorefers todelegation,whichinvolvestransferringpowertomoreor lessautonomouspublicorganizationmanagement(like pub-licenterprises,forexample the “hospitalsS.A” inPortugal, FoundationTrustsintheUKorpublicinsurancecompanies inBismarckian-typehealthsystems).Privatizationitselfcan beconsideredasaformofdecentralization.

Ourfocushereisthusonthetransferofpoliticalauthority inthehealthareafromhighertolowerlevelsofgovernment orfromnationaltosub-nationallevels.7Regional,provincial

ormunicipalelectedgovernmentsmaythusberesponsiblefor

planning,organizing,deliveringandfinancinghealthservices. Multiplearrangementsarehoweverpossibleanddevolution hastakenmanydifferentformsacrossOECDcountries(fora completemappingofdecentralizationexperiencesinEurope, see Bankauskaiteet al.8). Thesizeofdecentralizedentities

is highlyvariable,from small counties in Sweden(average population31,000)tolargeautonomousregionsinSpain (aver-age population 2,444,000). The extentof competencesalso varies.Thecentralstatemaykeepresponsibilitiesinseveral domains,forinstancetheCanadianFederalstatedefines poli-ciesregarding healthpreventionand promotion, the Swiss Confederationdefinesthebasichealthbenefitpackage,and generally allcentral statesimposea seriesofmoreor less stringent regulations on quality, supply, coverage, pricing rules orbudget allocation.Akey issuewhichdifferentiates decentralizationexperiencesrelatestothefundingofhealth expendituresandfinancialautonomy.Decentralized govern-mentsmayhavethepowertoraisetaxes,orreceivetransfers dependingontheircontributiontofiscalrevenues.Theymay then befree to set the budget allocated to health and its distribution amonghealth sectors.By contrast,sub-central government levels may be financed by transfers based on risk-equalization schemes and benefit from low autonomy in defining taxrates. In the lattercase, decentralized gov-ernmentsmaythushavethepoliticalpowertodecideabout allocation of resources but do not control the amount of availableresourcesforhealth.Hencetheexpendituresideis decentralized,butrevenueisnot.

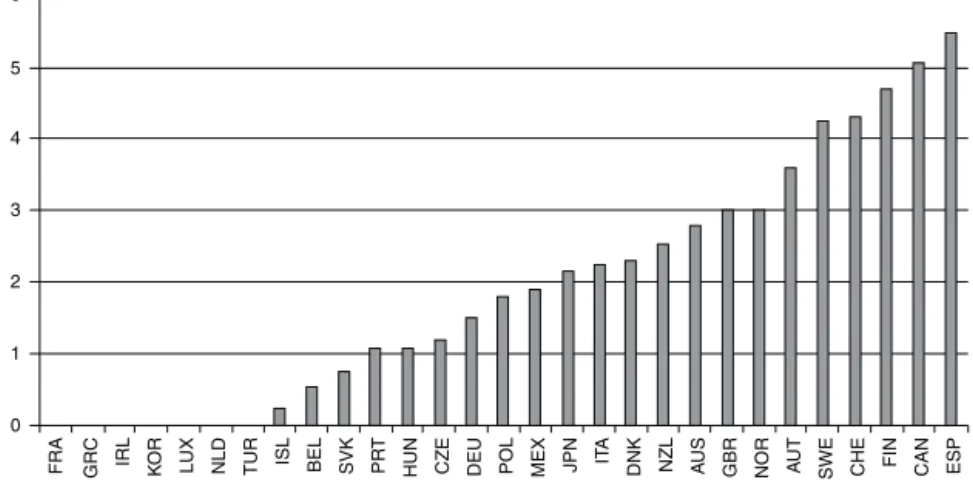

Fig. 1, extracted from Joumard et al.9, nicely describes

the degreeofdecentralizationin healthinOECD countries (wherea0scoreimpliesthatcentralgovernmenttakesmost ofkeydecisionswhilea6scoreimpliesresidualcompetences forthe centralgovernment). Countrieshaveheterogeneous sub-centralgovernments,withdifferentsize,autonomyand responsibilitiesallocated.Thecriteriatodefinethisscorehave beenestablishedbyParisetal.10,usingasurvey.Theyinclude

inparticularthesub-centralgovernments’authorityon set-ting tax bases and rates, the budget allocation for health anditsdistributionbetweenhealthsectors,thefinancingof different health services and practitioners and the setting ofpublichealthobjectives.Spain,Canada,Finland,Sweden andSwitzerlandhavehigherautonomyofsub-central govern-mentswhilePortugalisamongthecountrieswiththelowest healthdecentralization.

Notethatthedecentralizationquestion,thewaywepose it(devolutionorpoliticaldecentralization),ismorecommon inNHS-typehealthsystems.Thesesystemshavebeenusually characterizedbyhighlycentralizeddecision-making,withone singleinsurer/payerandprovider(thecentralstate),and lit-tleautonomygiventoproviders.Bycontrast,healthsystems basedonsocialinsuranceschemeshavebeen usually char-acterized,tovariousextents,bymultipleinsuranceschemes and some degree of publicly subsidized private provision. Hence,transferringpowertolocalinstitutionshascertainly respondedtoademandformoreautonomyinmorerigid NHS-typehealthsystems.

Spain,CanadaandItalyareparticularlyrelevantcasesto understandtheempiricalliteraturebecausetheconsequences of decentralization in health have been more extensively analyzed. The most decentralized country according to

6 5 4 3 2 1 0 FRA GRC IRL KO R

LUX NLD TUR ISL BEL SVK PR

T

HUN CZE DEU POL MEX JPN IT

A

DNK NZL AU

S

GBR NOR AU

T

SWE CHE FIN CAN ESP Fig.1–DecentralizationscoreforOECDcountries(extractedfromJoumardetal.9).

Joumardetal.9isSpain.Thecentralgovernmentprovidesthe

generalframeworkandcoordinatesthehealthsystemwhile AutonomousCommunities(AC)providehealthcareservices and are responsible for health planning, organization and management.11 Funds are centrallycollected and allocated

to regions bymeans ofa block central grant following an unadjustedcapitationformula.11OnlyNavarraandtheBasque

Countrybenefitfromfiscalauthority.

Bycontrast,theCanadianConfederation,composedof10 provincesand3territories,hasbeendecentralizedsincethe 19thcentury.12Healthfunding,administrationanddelivering

are competencesofprovinces,which alsodefine physician financingrulesandhospitalglobalbudgets.Howeverhealth promotion, preventionand provisiontospecific groupsare Federal competencies. Provinces are responsible for fund-inghealthcareexpenditures,basedonprovincialtaxesand transfers from the central government. Transfers depend themselvesontaxescollected atprovincial level;an equal-izationprogramwas howeverimplemented toavoidstrong differencesintransfersrelatedtodiscrepanciesinprovinces’ revenue-generatingpotential.13

Finally, the 20 Italian regions also control health care provision,althoughgeneralobjectives(likethe detailedlist ofservicestobeprovided)andmainprinciplesofthehealth systemaredefinedatthecentrallevel.Regionscandevelop regionalhealthplans,allocateresourcesandcollectrevenues freely, like setting user charges for drugs prescriptions or reimburseratesfordrugsandservicesnotcoveredatnational level. Regional authorities also enjoy financial autonomy in taxation; in practice, regional health expenditures are financedat36.7%byregionaltaxes.14Additionally, regional

healthexpendituresarefinancedbytransfersfromthecentral state (57.3% of expenditures), essentially from a so-called Nationalequalizingfund.Thisfundisbasedontheideathat allregionsmustachieveaminimumlevelofexpenditures,so thattransferstopupregions’ownrevenueincaseitisunable tofundthisminimumlevel.

Theoretical

background

Thedebateontherelativemeritsofpolicydecentralization datesbacktoTiebout,15who putforward averyoptimistic

argument for the optimality of local public good provi-sion, based on an analogy between competitive markets and competing jurisdictions. Oates,2 in contrast, suggests

that decentralization results from a trade-off between its advantagesandcosts.AccordingtoOates,theadvantageof decentralizationliesinitscapacitytocatertolocaltastes,be itbecauseofbetterinformationorsimplybecausethe cen-tral governmentcannotdifferentiatepublicgood provision. Thecostofdecentralizationstemsessentiallyfromthe pres-ence ofinter-regionalspillovers.For instance,betterhealth preventioninonemunicipalitybenefitsitsneighbors. How-ever,ifhealthpreventionisdecentralized,eachmunicipality failstotakeintoaccountthebenefitofitsinvestmentinother municipalities,andisthereforelikelytoinvestsub-optimally, leadingtounder-provisionand/orlowqualityofhealth ser-vices. WhileOates’argument that acentral governmentis unable to differentiate the provision of local public goods accordingtolocalpreferenceshasbeenchallengedsince,his mainintuitionthatthedecisiontodecentralizerestsona fun-damental trade-offbetweencostsand advantagesremains. One ofthe maincosts ofdecentralizationwhich has been analyzedintheliteratureisthefailuretoexploiteconomies of scale.16 For instance, collective purchasing of resources

(drugs,medicaldevices,equipments,etc.)orcollective admin-istrationofhealthservices maydisplay decreasingaverage costsandbethusmoreefficientlyprovidedatacentralized level.

Theinter-regionalspilloversattheheartofOates’s argu-ment,referredhere-above,areofthehorizontaltype(thatis, betweensub-centralgovernmentsofthesamelevel).Another sortofspilloverswhichmaycreateinefficienciesunder decen-tralization is the vertical ones between local and central governments. These occur if onegovernment level’spolicy decisionshaveanimpactinthepolicyoutcomesoftheother level.Thesephenomenaarehighlyplausibleinthehealthcare sector.If,forexample,sub-centralgovernmentsare respon-sible for some public health preventionprograms and the centralstatedelivershealthcare,localpolicieslikelyaffect servicesuseandcostsatthecentrallevel.Unlesssub-central governmentsarerewardedfortheiractions,theyhavelittle incentivestoprovideanoptimalvalueofprevention,whose benefitsarefullyenjoyedbythecentralstate.

rev portsaúde pública.2013;31(1):74–83

77

Recently,theliteraturehasputforwardpoliticaleconomy argumentsinfavorofdecentralization.Forinstance,itmay bethatthevoters,whoareimperfectly informedaboutthe economy,use the policiesput inplace by the neighboring politicians to impose discipline on their own local repre-sentative. In such a worldof opportunistic policy makers, decentralizationmaybeastrongmechanismtoprevent cor-ruptionor promote provision ofpublic services.17 Another

argumentisthatdecentralizationforceslocaljurisdictionsto competeformobileresources(forinstance,labororcapital) andputsadownwardpressureontaxation,thuspromptinga moreefficientuseofscarceresources(seeWilson18fora

sur-veyofthetaxcompetitionliterature).BesleyandSmart19show

thatthisneednotbethecase,sincehigherdisciplineoflocal politicianscomesatthecostofaworseselection.Indeed,it isonlywhenanopportunisticpoliticianmisbehavesthatthe votersaregiventhechancetooustherfrompowerandreplace herwithapotentiallybenevolentpolitician.Political account-abilityresultsfromatrade-offbetweenthesetwomechanisms (disciplineand selection),and further decentralization has oppositeeffectsinboth.

What can be said about the likelihood of local govern-ments being captured by special interests? Bardhan and Mookherjee20showthatthereisnotheoreticalreasonto

sup-pose that local governments are more prone to this than centralones.Theyputforwardatheoreticalmodelof proba-bilisticvotingwherecapturebyspecialinterestsresultsfroma combinationofvoterawareness,interestgroupcohesiveness, electoraluncertaintyandcompetition,districtheterogeneity andtheelectoralsystem.Theirmainconclusionisthatthe extentof captureat the locallevel is most likely context-specificandneedstobeassessedempirically.

Afewauthorshavelookedattheapplicabilityofthese argu-mentstothespecificcaseofhealthdecentralization.Levaggi andSmith21 claimthat sub-centralgovernmentsare better

informedabouttheconstraintsoflocalsupplyandabout vari-ationsindemand.Variationsindemandareobviouslyrelated firsttodifferencesinlocalneeds,forinstanceregions experi-encediscrepanciesintheprevalenceofdiseases,inbehavioral andnon-behavioralriskfactors(includinginparticular age-ingorsocialdeterminants),perhapsalsointheeffectiveness ofspecificinterventions.Henceprioritiesarelikelytodiffer accordingtoburdenofdiseaseorcost-effectivenesscriteria. Alsolocalpreferencesshapevariationsindemand,leading todifferentprioritiesandresourceallocationcriteria.Wemay thinkthatsomeregionshaveahigherconcernforinequalities inhealthandsocialdeterminants,whileothersputagreater emphasisonproviderchoiceandresponsivenesstopatients’ preferences.Thesedifferencesinneedsandpreferencesare veryclearifwecompareEuropeancountries.Discrepancies inlocalsupplyarerelatedtothe availabilityand densityof physicians, nurses, equipments, but also to differences in localpricesandpractices.Centralgovernmentshavetriedto accountforthesedifferencesinfinancingsub-central govern-ments,throughmoreor less sophisticatedrisk-adjustment schemes,butmaynotbeabletoaddresstheseissuestolocally adjustedplanningororganization.Sub-centralgovernments maybebetterequippedtorespondtolocalpreferencesand priorities,tocoordinateproviders’actionsandtoidentifythe sourcesofinefficiency.Hence,decentralizationisexpectedto

enhance qualityandresponsivenessofcarewhilereducing costs;thistheoreticalviewisattheoriginofmost decentral-izationprocesses.

As regards the potential incentivesthat favor efficiency and/orqualityinhealthcareprovision,boththetax compe-titionand theyardstickcompetition mechanismsarelikely toariseinhealthpolicies,thusleading sub-central govern-ments tocompete witheach other to provide high-quality servicesatlowuserchargesorfinancedthroughlowertaxes. First,betterandmoreefficientservicescontributetoattract mobile citizens, hence increase sub-central governments’ economic activityand fiscal revenues.Second, competition occursthroughcitizensbenchmarkingtheirdemandsonthe basisofneighborsub-centralgovernments’performance.22If

sub-centralgovernmentsare politicallyaccountable,alocal politicianprovidingpoorerservicesthanhisneighbors’ coun-terpartswouldlikelyfailre-election.Inafewwords,efficient provisioncontributestoattractivenessandcitizens’ satisfac-tion.

It isa well-known fact that decentralizationmay ham-per redistribution(see, Cremer et al.23 for asurvey of the

literature), when taxes are locally collected. Areas with high health needsare in generalthe poorer ones(thereis largeevidenceoftherelationshipbetweenpovertyandpoor healthstatus,seeMarmotReview24);underfiscal

decentral-ization,underprivilegedareascapturelower resourcesfrom taxationandbenefitfromalowercapacitytoinvestin high-qualityservicesandefficientprovision.Decentralizationthen produces differences in the quality and availability of ser-vices,chargesandoutcomes.Increasinginequityisoneofthe majorthreatsofdecentralization,evenifgood risk-sharing agreementspotentially mitigatethis effect.Inother words, the viability of decentralization depends on the existence of solidarity mechanisms between decentralized authori-ties.

Thereverseisalsopossible,i.e.,sub-centralgovernments only competing on high-quality services, leading to over-provision ofservices and high health expenditures(race to the top). This situation is more likelyto occur when fiscal decentralizationislowandsub-centralgovernmentsfacesoft budget constraints. Thismay the case, forexample, if the centralgovernmentsystematicallybailsoutsub-central gov-ernments which are excessivelyindebtedor if transfers to sub-centralgovernmentsarebasedonpastexpenditures.

Thisbringsustothefundamentalquestionofthe fund-ing oflocalpublicgoods.Indeed,variousarrangementsare possible regarding the degree of decentralization of both theexpenditureandtherevenuefunctions.25Aconsiderable

shareoflocalgovernmentfundingcomesfromcentral gov-ernmenttransfers.Thesetransferschemesmustbecarefully designedandrestonclearrules(dependonvariableswhich are noteasyforlocalgovernmentstomanipulate) soasto avoidmoralhazardleadingtoexcessexpenditures.Indeed,as thecentralgovernmentisunabletodistinguishthesourcesof highspendingbetweenhigherneedsandinefficiencies, sub-centralgovernmentshaveanincentivetohidetheirtrueneeds toobtainhigherfinancingfromthecentralauthority.

Tosumup, the theoreticalliteraturedoes notprovidea definitive answer about the impact of decentralization on healthpolicies.Thehighconcerninmanycountriesforequity

r e v p o r t s a ú d e p ú b l i c a . 2 0 1 3; 3 1(1) :74–83

Table1–Literaturereview:impactofdecentralization.

1stauthor Country Objective Periodofthe

data

Decentralizationindicator Mainresults

Zhong(2010) Canada Impactoftheintroductionofa

higherdegreeofdecentralization onequityinhealthcareutilization

1994/95 1998/99 2000/01

IntroductionofHealthandSocial Transferin1996/97,i.e.,larger blockfundingtoprovinces

Mostinequityinhealthcareuseisexplainedby variationswithinprovinces.Anincreasein decentralizationleadtoloweroveralland

within-provinceinequityinGPandhospitalservices andlowerbetween-provincevariationinGP, hospitalandspecialistservices

Scheffler(2006S.) USA/California Impactofhigherdecentralization

ofmentalhealthcareserviceson uninsuredhealthspending

1989–2000 Decentralizationofhealth,mental health,andsocialservices(greater financialflexibilityand

responsibility)fromtheCalifornia statetocounties(program realignmentintroducedtheability totransferfundsbetween programs–mentalhealth,social servicesandgeneralhealth)

Countyspendingonmentalhealthservices decreasedafterprogramrealignment.Countieswith abovemedianhealthrevenuesarelesslikelyto makeatransfertoanotherprogram.With realignment,countiesshowedthesamelevelof commitmentandsupportwithmentalhealth services,sincedivertedfundswentmainlyto mentalhealthserviceswithintherealignment programspackage

Jiménez-Rubio(2011A) 20OECDcountries Impactofdecentralizationon

healthstatus(infantmortality)

1970–2001 Decentralizationmeasuredas:(i) Shareofautonomoustaxrevenue ofSCGovertheCGtaxrevenue.(ii) Shareoftotal(autonomousornot) SCGtaxoverthetotalrevenue

Negativeandsignificantrelationshipbetweenfiscal decentralizationandinfantmortality,ifa

substantialdegreeofautonomyinthesourcesof revenueisdevolvedtosub-centralgovernments

Prieto(2012) Spain Estimatedeterminantsofregional

healthcareexpenditure,in particularthedegreeofregional autonomy

1992–2005 Regionsclusteredaccordingtothe degreeofautonomy:(i)

Expenditureandhighfiscal autonomy.(ii)Expenditureandlow fiscalautonomy.(iii)Noautonomy

GDP/capitahasmoreinfluenceonHCEinregions withhighertaxautonomy,maybedueto equalizationeffortsofSpanishNHS.

Decentralizationwithoutinequalityispossiblewith fiscalequalization.Ifhighdifferencesinwealthand weakequalizationamongregions,decentralization leadstoinequality

Bordignon(2009B.) Italy Impactofregions’bailout

expectationsonfundingbyCG; impactofregions’bailout expectationsonHCE(mid-90s), determinantsofregions’bailout expectations

1990–1999 Regions’bailoutexpectations basedonexternalconstraintsin themid-90s:countries’evaluation forenteringtheEURO(1997),index ofpublicbudgettightness, Maastrichtrules(1994)

HCEisinfluencedbyregionalfinancing,whichisin turninfluencedbybailoutexpectationsfromtheCG. Lowerexpectationsofbailingoutgeneratea strongerlinkbetweenex-antefinancingand regionalHCE.Richerandmoreautonomousregions havelowerexpectationsofCGintervention,hence theyaremorefinanciallyresponsible.TheCGisalso morepronetocutfinancingtoregionsunderlower bailoutexpectationsbecausethecommitmentto cutHCEwillbetakenseriously

Fredriksson(2008F.) Sweden Estimatecross-counties

differencesinsupportingthe “PatientChoice

Recommendation”,i.e.,counties’ willingnesstofavorornotthe patient’schoiceofspecialist

2001–2005 RecommendationbytheCGcanbe

moreorlesssupportedby counties,whichhavelarge competencesinthehealthsector

HighvariationonsupportforthePatientChoice Recommendationamongcountycouncils. Abilitytochoosehealthcareprovidervaries accordingtocounty,creatinginequalitiesinaccess tocare

r e v p o r t s a ú d e p ú b l i c a . 2 0 1 3; 3 1(1) :74–83

79

Table1(Continued)1stauthor Country Objective Periodofthe

data

Decentralizationindicator Mainresults

López-Casasnovas(2007L.-C.) 110regionsin8

OECDcountries

MeasurethedeterminantsofHCE accountingforregionaleffects

1997 Noindicatorofdecentralization

butaccountforpossibleregional differencesinHCE

Anincreaseonthepercentageofpeoplewithmore than65yearsandinthepercentageofpublichealth expendituresincreasesHCE.Betweencountries variabilityofexpendituresissmallerthanwithin countryvariations.IncomeelasticityofHCEislow andincreaseswithvariationinHCE

Costa-Font(2007C.-F.) Spain MeasurespatialspilloversinHCE

(inter-jurisdictioninteractionsin definingHCE)

2003 Compareregionswith(i)fiscaland

politicalautonomy(Navarraand Basquecountry);(ii)political autonomy(Catalonia,Galicia, Andalucía,CanariasandValencia); (iii)noautonomy

Evidenceofspatialcorrelation.HigherHCEwhen regionshavehigherpoliticaldecentralizationand evenhigheriftheyhavealsofiscaldecentralization. HigherHCEifregionandCGareruledbythesame party

Costa-i-Font(2005C.-i.-F.) Spain Measureincome-related

intra-regionalinequalitiesin self-reportedhealth,andits relationwiththedegreeof decentralization

1997 Compareregionswith(i)fiscaland

politicalautonomy(Navarraand Basquecountry);(ii)political autonomy(Catalonia,Galicia, Andalucía,CanariasandValencia); (iii)noautonomy

Overallinequalityislow.Devolutiondoesnotfavor inter-regioninequality.Bycontrastdevolution seemstofavorpro-equitypolicies:inequalityisthe highestinregionswithoutautonomy(INSALUD)

Crivelli(2006C.) Switzerland Measuredeterminantsofpublic

HCEaccountingforregional (cantons)effects

1996–2001 Noindicatorofdecentralization butaccountforpossibleregional differencesinHCE

DifferencesinHCErelatedtousualfactorsbutin particulartophysiciandensity.Strongdifferencesin HCEacrosscantonsexplainedinpartbydifferences insupply

Costa-Font(2009C.-F.) Spain ImpactofdecentralizationonHCE,

interdependencybetween neighbormunicipalitiesand measureincomeeffectatregional level

1995–2002 Indicatorsofdecentralization degreeanditsevolutionacross time,towardcurrentsituation:(i) fiscalandpoliticalautonomy (NavarraandBasquecountry);(ii) politicalautonomy(Catalonia, Galicia,Andalucía,Canarias, Valencia);(iii)noautonomy

PoliticaldecentralizationincreasesHCEintheshort termbutproducescostsavingsinthelongrun(sunk costofdecentralizationandexperienceeffects). Higherexpendituresarerelatedtohigherfiscal autonomy.Existenceofspatialcorrelation.Low impactofincomeonHCE,hencedecentralizationis notassociatedtostrongregionalinequalities

Cantarero(2005C.) Spain Measuredeterminantsofpublic

HCEaccountingforregionaleffects

1993–1999 Compareregionswith(i)fiscaland politicalautonomy(Navarraand Basquecountry);(ii)political autonomy(Catalonia,Galicia, Andalucía,Canarias,Valencia);(iii)

noautonomy

Regionalincomeandsupplyhavelowimpacton HCE,whileageingismorerelevant.Hencelower income-relatedinequalityisexpected

Jiménez-Rubio(2011) Canada Impactoffiscaldecentralization

onhealthoutcomes(infant mortality)

1979–1995 Fiscaldecentralizationis measuredastheproportionof sub-nationalhealthspendingover totalhealthexpenditure

Significantandsubstantiallylowerinfantmortality relatedtohigherfiscaldecentralization(1%increase infiscaldecentralizationdecreasesinfantmortality by10%)

Giannoni(2002) Italy MeasuredeterminantsofHCE

accountingforregionaleffects, andimpactof1992

cost-containmentreforms

1980–1995 Noindicatorofdecentralization butaccountforpossibleregional differencesinHCE

StrongimpactofregionalincomeonHCEand relevantareaclusterdifferences.Cost-containment reformsdidnotaltermostregionaldifferencesin HCEandworsenedthesituationofsomeregions belowtheaverage

T able 1 (Continued ) 1st author Countr y Objecti v e P eriod of the data Decentr alization indicator Main results Cantar er o (2008 C.) Spain Impact of fiscal decentr alization on health outcomes (infant mortality and life e xpectanc y) 1992–2003 F iscal decentr alization is measur ed as the pr oportion of sub-national health spending ov e r total health e xpenditur e Decentr alization significantl y reduces infant mortality and incr eases life e xpectanc y Di Matteo (1998) Canada Measur e determinants of HCE accounting for re g ional (pr o vinces) effects 1965–1991 No indicator of decentr alization but account for possib le re g ional differ ences in HCE HCE highl y related to per capita income (but elasticity belo w 1), a g eing and feder al tr ansfers. Reflects pr o vincial HCE reflects tr ansfers fr om CG whic h ho w e v e r do not corr ect re g ional income discr e pancies Jiménez-Rubio (2008 J.-R.) Canada Measur e income-r elated inequalities in health and health car e use acr oss re g ions (pr o vinces) 2001 No indicator of decentr alization but measur e re g ional differ ences in inequalities Health car e use inequalities ar e d rive n by betw een-pr o vinces v ariation. Inequalities in health ar e mostl y d rive n by within-pr o vinces v ariation. Differ ent results for health and health car e inequalities seem to sugg est other health determinants rather than health car e access ar e essential to e xplain inequalities HCE, health car e e xpenditur es; CG , centr al go v ernment; SCG , sub-centr al go v ernment; GP , g ener al pr actice; AC , autonomous comm unities.

inhealthisamajorargumentagainstdecentralization,unless strong solidaritymechanisms areputinplace. The contra-dictoryexpectationsaboutefficiencyrequirecarefulempirical validation.Inthesetimesofadverseeconomiccircumstances, efficiencyismorethaneveramajorissueindecision-making, andstrongevidenceisnecessarybeforeadvocatingfor decen-tralizationinhealth.

Empirical

evidence

Inordertogetanexhaustiveoverviewonempiricalevidence, weperformedasystematicliteraturereview.Weconducteda computerizedliteraturesearchinPubMed(NationalCenterfor BiotechnologyInformation,Bethesda,Maryland)andGoogle Scholar,supplementedbyasearchofquotedreferences.Text keywordsusedinthesearchincludeddecentralization, feder-alism,health,healthcare,equity,andefficiency.Werestricted ouranalysistothoseperformedinOECDcountriestoallow forrelevantcomparisons,thatis,inacomparablecontext.We onlyincludedempiricalstudiesabout theimpactof decen-tralization,henceexcludingtheoreticalstudies,studiesabout legislation or about political or organizational aspects of decentralization,editorialsandliteraturereviews.Thesearch waslimitedtoEnglish-languagearticlespublishedfrom1995 toJuly2012,whendecentralizationinhealthhasbecomea rel-evantandappliedpolicyoptioninOECDcountries.Oursearch allowedcollecting17papers,whosemaincharacteristicsand resultsaredisplayedinTable1.Studiesweredividedaccording todistinctanalyzes,basedonthemostrelevant decentraliza-tionoutcomes,namelyinequalitiesinhealthandhealthcare, healthexpendituresandhealthoutcomes.

Inequalityinhealthandhealthcareuse

Theconsequencesofdecentralizationoninequalitywerethe mainissueanalyzedbyZhong13,Jiménez-Rubioetal.1,

Costa-i-Font26andFrederikssonandWinblad27.Zhong13foundthat

in Canada inequalities in health care use (overall, within provincesandbetweenprovinces)decreasedafter decentral-ization. Mostinequalitywasexplainedbywithin-provinces variation,whilebetween-provincesvariationsdidnotmuch contributetoinequality.13Bycontrast,Jiménez-Rubioetal.1

also using data from Canadian provinces observed that income-relatedinequalitiesinhealthcareuseresultedfrom between-provincesvariationswhileincome-related inequali-tiesinhealthwererelatedtowithin-regionvariations.While Zhong13 used an overall inequity measure, Jiménez-Rubio

etal.1 usedanincome-relatedone,whichpossiblyexplains

the discrepantresults.TheresultsbyJiménez-Rubio etal.1

certainlyquestiontheequalizationschemeacrossprovinces; the redistributionoffundsfrom richertopoorer provinces does notseemtoavoidinequityinhealthcareuse related tobetween-provincevariations(forexample,healthcareuse islowerinQuebecthathasalower-than-averageincomeper capita). Asthe author emphasizes, advocates of decentral-izationwouldhoweverconsiderthesedifferencesasrelated to different preferences, hence legitimate. Income-related inequityinhealthwasmostlyrelatedtodifferencesbetween rich and poor people within provinces, here questioning

rev portsaúde pública.2013;31(1):74–83

81

the efforts by provinces to reduce inequalities (would a centralgovernmentbemorecommittedtoreduceinequityin health?).

For Spain, Costa-i-Font26 found a small overall, within

and between regions income-related inequality in health, althoughsomewhathigherinregionswithlowerautonomy. The author explains this difference by the greater role of theprivatesectorinthoseregions.Healsoemphasizesthat decentralization may have favored equity due to a high commitment of regions to achieve this objective, which corresponds to a high citizens’ concern. Finally, Fredriks-son and Winblad27 studieda specific reform toward more

providerchoiceinSweden, wherehealthcareuseishighly decentralizedatthe county level. Theauthor showed that whilesomecountiessupportedthereformthroughfavoring choice,othersimplementedadministrativebarriersagainstit. Therefore,autonomyondecisionmaking(regardingprovider choice) resulted on inequalities between people living in differentSwedishcounties.

Healthexpenditures

Inequalityrelatedtodecentralizationwasalsoobserved indi-rectly, through examiningthe impact of regional GDP per capitaonhealthcareexpenditures.Indeed,agreaterimpactof regionalincomeonhealthcareexpenditurewouldmeanthat richerregionsspendsignificantlymoreonhealththanpoor ones,hencecreatinginequalitiesinhealthcareuse.Although all studies using regional data conclude that health care expendituresdonotvarymuchwithincome(theelasticitywith respecttoincomeisbelowone),resultsare contrastedand varybetweencountries. For Spain,Prietoand Lago-Pe ˜nas28 foundapositiverelationbetweenincomeandpublichealth expenditures only in regions with higher fiscal autonomy. Regions without fiscal autonomy benefitted from national equalizationeffortsandthereforemanagedtoachievehigh levelsofhealthcareexpendituresdespiteoflowerincome.The lowimpactofincomeonhealthcareexpendituresinSpain wasconfirmedbyCantarero,Costa-i-FontandMoscone.29,11

ThesameconclusioncouldbedrawnforCanada,21although

theimpactofincomeonhealthexpenditureswasgreaterthan inSpain.Usingaspecificindicator,DiMatteoandDiMatteo30

showedthepositiveimpactoffederaltransfersonhealthcare expenditure. That is, federaltransfers certainly reducethe impactofregionalincomeonexpendituresbutdonotfully correctregionalincomediscrepancies.Thepictureis some-whatdifferentinItaly,whereregionalincomehadastrong impactonhealthcareexpenditures.31 Theauthorsshowed

alsothatcost-containmentmeasureshavenotaltered cross-regional differences in health care expenditures and have evenworsenedtheminsomecases.ForSwitzerland,Crivelli etal.32observedalargeimpactofphysiciansupply,whichis

highlyvariable acrossregions,onhealthcareexpenditures. Hencecross-regionaldifferencesinhealthcaresupplymay alsobeasourceofinequalityacrossregions.Finally,usingdata from110regionsof8OECDcountries,Lopez-Casasnovasand Saez33showedalowelasticityofhealthcareexpenditurewith

respecttoincome.However,theimpactofincomewashigher acrossregionsincountrieswithhigherinter-regionalincome

inequalities,leadinginturntohigherdiscrepanciesinhealth careexpenditures.

SchefflerandSmith34,Costa-i-FontandMoscone11,

Costa-i-FontandPons-Novell22addressedtheimpactof

decentral-izationonhealthexpenditures,whileBordignonandTurati35

examinedtheimpactoftheinteractionbetweencentraland sub-centralgovernments.SchefflerandSmith34showedfor

California that spending on uninsured patients decreased withthehighercounties’autonomyinallocatingfundsacross health and social programs. Costa-Font and Pons-Novell22

observed that Spanish regions with both political and fis-calautonomyhadhigherhealthexpendituresascompared to regions without autonomy or with political autonomy only. Costa-i-Font and Moscone11 observed however that

decentralization increased expenditures only in the short run, producing savings in the long run. They argued that firstly decentralization increased health care costs due to sunkcosts;then thiseffectwasminimizedinthe longrun by an experience curve, that is, learning-by-doing allowed reducing costs.Regarding assumptionsfrom economic the-ory, Costa-i-Fontand Moscone11 alsoshowedtheexistence

of spatial correlation ofhealth care expenditures between neighborjurisdictions,sustainingtheassumptionof horizon-tal spillovers.Thisresultmay hencebeduetocompetition betweenneighborjurisdictionstoincreaseattractivenessor duetopoliticiansbeingjudgedbasedontheneighbor coun-terparts’actions.

Finally,BordignonandTurati35 used1990sItalian

adjust-ment processimposed byanexternalentity(theEuropean Union)tounderstandtheroleofexpectationsandthe strate-gicinteractionsbetweenthecentralstateandregions,using dataonhealthcareexpenditures.Regionsexpectingthatthe central governmentwillintervene incaseofdebtsoftened their budget constraints and the relationship between the fundingtheyreceivefromthecentralgovernmentandhealth expenditureswaslower.Bycontrast,duringexternal adjust-ment,thecentralgovernmentwasperceivedasmorestringent and the link between funding and expenditures became stronger.Andthe centralgovernmentwas alsomoreprone tocut fundingtoregions becauseit knewits commitment nottobailoutwouldbetaken moreseriously.Interestingly, authors showed that more autonomy lead to more finan-cially responsible policies because expectations of bailout werelow.Thispaperthusemphasizedthattransfer mecha-nisms,whicharealwayspresentindecentralizedcountries, createdincentivesthatmaybemoreorlessdetrimentalfor efficiency dependingon how theyare designedand putin practice.

Healthresults

Results about the impact of decentralization on health outcomesarescarcebutconsistentacrossstudies. Jiménez-Rubio12,36 andCantareroandPascual37 agreeonidentifying

a positive relationship between fiscal decentralization and healthresults,measuredthroughinfantmortality.Cantarero and Pascual37usedanalternativemeasureofhealthstatus

(lifeexpectancy)whichconfirmedthepositivecontributionof decentralizationtohealthstatus.

Conclusion

Althoughtheeconomicsliteraturehaslargelydiscussedthe impactofdecentralization,empiricalresultsremain scarce, inparticularregardingdecentralizationinhealth. Neverthe-less,decentralizationofhealthpoliciesandfundinghasbeen largelyimplementedinvariouscountriesandisgenerally con-sideredasarelevantoptiontoimproveefficiencyinhealth care.7

Our review of the literature allows draw preliminary conclusions,basedonrelativelyrecentdecentralization expe-riences,inparticularinCanada,Italy,SpainandSwitzerland. Firstandforemost,devolutionofpolitical(andfiscal) author-itytosub-governmentlevelsseems toincreasehealthcare expendituresbutalsoimprovehealthoutcomes,mainly mea-suredthroughinfantmortalityrate.Accordingtoeconomic theory, decentralization may foster competition between jurisdictionstoincreaseattractiveness,andincreasepressure onlocalgovernmentsbecausecitizensevaluatetheir perfor-mancebasedonneighborcounterparts’actions.Theempirical literaturesuggeststhatenhancedcompetitionpromptslocal decision-makerstoincreasehealthcareexpenditures(raceto thetop)andnotthereverse inorder todecrease taxes(race

tothe bottom),with afavorableimpact onhealth. Thecase ofSpainisparticularlyenlightening,whichshows thatthe increase inhealth careexpenditures has been the highest inregionswithfiscalautonomy.Thisresultmayreflectthe highpeople’sdemandforhigh-qualityhealthservices,andthe higherresponsivenessoflocalauthoritiestothispreference. Thehigherhealthcareexpendituresunderdecentralization mayhoweverreflectalsohighercosts,relatedforinstanceto duplicationofinputs(twoneighborregionsofferingsimilar serviceswhichcouldbeshared),diseconomiesofscale,orthe sunkcostsassociatedtoimplementationofalocalhealth pro-visionscheme.Tosomeextent,adverseincentivesmayplay someroleifsub-centralgovernmentsarenotfullyfinancially responsiblefortheirexpenditures.Inparticular,moral haz-ardmayexistifsub-centralgovernmentsexpecttheirdebts beingcoveredbythecentralstate(bailout)oriftheirbudget dependsmorelargelyfromtransfersfromthecentralstate. Inafewwords,decentralizationdoesnotappearatfirstsight asameanstocontrolorreducehealthcareexpenditures,but asanincentivetoprovidebetterandpossiblymoreexpensive services.Theefficiencyconsequencesarethusambiguous,as itisunclearwhetheradditionalbenefits–measuredthrough averyreduced numberofindicators–areworthadditional costs.

Regarding equity, empirical results are ambiguous and certainlyrelatedtothespecificcountries’ context.Inequity in health and health care is low in Spain, where health expendituresarealsopoorlyrelatedtotheregionGDP/capita. Additionally, inequity in health careseems tobe lower in moreautonomousregions,sothatdecentralizationmayhave favoredequity.InCanada,income-relatedinequityinhealth careisrelatedtobetween-provincesinequalities.InItalyand Switzerland,thereisastrongrelationshipbetweenregions (resp.cantons)incomeandhealthcareexpenditures, result-ing in a large heterogeneity in health care expenditures. These resultsmay certainlybe relatedto lower equalizing

mechanisms inthese twocountries coupledwitha higher fiscal autonomy. Note also that different decisions across regions,namelyaboutphysiciansorequipmentsupply,also potentiallycreatedifferences/inequityinhealthcaredelivery. To conclude, solidarity mechanisms across sub-central authorities are relevant to avoid the emergence of large inequalitiesacrossregionsinhealthcaredeliveryand expend-itures. However, redistribution offunds alsoreduces juris-dictions’ financial responsibility, with possibledetrimental consequencesonexpendituresandambiguousconsequences on efficiency.Thislastaspectisofparticularimportanceif jurisdictions compete with each other for providing high-qualityservicesandnotthroughloweringtaxrates.

Funding

This investigation was funded by the Fundac¸ão para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through the project PTDC/EGE-ECO/104094/2008.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarethattherearenoconflictsofinterests.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.Jiménez-RubioD,SmithP,DoorslaeE.Equityinhealthand healthcareinadecentralisedcontext:evidencefromCanada. HealthEcon.2008;17:377–92.

2.OatesW.Fiscalfederalism.NewYork:HarcourtBrace Jovanovich;1972.

3.IimiA.Decentralizationandeconomicgrowthrevisited:an empiricalnote.JUrbanEcon.2005;57:449–61.

4.Rodriguez-PoseA,EzcurraR.Doesdecentralizationmatterfor regionaldisparities?:across-countryanalysis.JEconGeogr. 2010;10:619–44.

5.GalianiS,GertlerP,SchargrodskyE.Schooldecentralization: helpingthegoodgetbetter,butleavingthepoorbehind.J PublicEcon.2008;92:2106–20.

6.VrangbaekK.Towardsatypologyfordecentralizationin healthcare.In:SaltmanRB,BankauskaiteV,VrangbaekK, editors.Decentralizationinhealthcare.Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill.OpenUniversityPress;2007(European ObservatoryonHealthSystemsandPoliciesSeries).p.44–62. 7.BankauskaiteV,SaltmanRB.Centralissuesinthe

decentralizationdebate.In:SaltmanRB,BankauskaiteV, VrangbaekK,editors.Decentralizationinhealthcare. Maidenhead:McGraw-Hill.OpenUniversityPress;2007 (EuropeanObservatoryonHealthSystemsandPolicies Series).p.9–21.

8.BankauskaiteV,DuboisHFW,SaltmanRB.Patternsof decentralizationacrossEuropeanhealthsystems.In:Saltman RB,BankauskaiteV,VrangbaekK,editors.Decentralizationin healthcare.Maidenhead:McGraw-Hill.OpenUniversity Press;2007(EuropeanObservatoryonHealthSystemsand PoliciesSeries).p.23–43.

9.JoumardI,AndréC,NicqC.Healthcaresystems:efficiency andinstitutions.Paris:OECDPublishing;2010(OECD EconomicsDepartment.WorkingPapers;769). 10.ParisV,DevauxM,WeiL.Healthsystemsinstitutional

rev portsaúde pública.2013;31(1):74–83

83

Publishing;2010(OECDEconomicsDepartment.Working Papers;50).

11.Costa-i-FontJ,MosconeF.Theimpactofdecentralizationand inter-territorialinteractionsonSpanishhealthexpenditure. EmpirEcon.2008;34:167–84.

12.Jiménez-RubioD.Theimpactofdecentralizationofhealth servicesonhealthoutcomes:evidencefromCanada.Appl Econ.2011;43:3907–17.

13.ZhongH.Theimpactofdecentralizationofhealthcare administrationonequityinhealthandhealthcarein Canada.IntJHealthCareFinanceEcon.2010;10:219–37. 14.FerrarioC,ZanardiA.FiscaldecentralizationintheItalian

NHS:whathappenstointerregionalredistribution?Health Policy.2011;100:71–80.

15.TieboutC.Apuretheoryoflocalexpenditures.JPolitEcon. 1956:64–416.

16.HaimankoO,LeBretonM,WeberS.Transfersinapolarized country:bridgingthegapbetweenefficiencyandstability.J PublicEcon.2005;89:1277–303.

17.BelleammeP,HindriksJ.Yardstickcompetitionandpolitical agencyproblems.SocialChoiceWelfare.2005;24:155–69. 18.WilsonJD.Theoriesoftaxcompetition.NatlTaxJ.1999;52:269. 19.BesleyT,SmartM.Fiscalrestraintsandvoterwelfare.JPublic

Econ.2007;91:755–73.

20.BardhanPK,MookherjeeD.Captureandgovernanceatlocal andnationallevels.AmEconRev.2000;90:135–9.

21.LevaggiR,SmithPC.Decentralizationinhealthcare:lessons frompubliceconomics.In:SmithP,GinnellyL,SculpherM, editors.Healthpolicyandeconomics:opportunitiesand challenges.London:OpenUniversityPress;2004.

22.Costa-i-FontJ,Pons-NovellJ.Publichealthexpenditureand spatialinteractionsinadecentralizednationalhealth system.HealthEcon.2007;16:291–306.

23.CremerH,PestieauP.Factormobilityandredistribution.In: VernonHendersonJ,ThisseJ-F,editors.Handbookofregional andurbaneconomics.Vol.4.Amsterdam:Elsevier;2004.p. 2529–60.

24.InstituteofHealthEquity.Marmotreview:fairsociety, healthylives:strategicreviewofhealthinequalitiesin

Englandpost2010.London:InstituteofHealthEquity; 2010.

25.OECD.Taxingpowersofstateandlocalgovernment.Paris: OECDPublications;1999.

26.Costa-i-FontJ.Inequalitiesinself-reportedhealthwithin SpanishRegionalHealthServices:devolutionre-examined? IntJHealthPlannManage.2005;20:41–52.

27.FredrikssonM,WinbladU.Consequencesofadecentralized healthcaregovernancemodel:measuringregionalauthority supportforpatientchoiceinSweden.SocSciMed.

2008;67:271–9.

28.PrietoDC,Lago-Pe ˜nasS.Decomposingthedeterminantsof healthcareexpenditure:thecaseofSpain.EurJHealthEcon. 2012;13:19–27.

29.CantareroD.Decentralizationandhealthcareexpenditure: theSpanishcase.ApplEconLett.2005;12:963–6.

30.DiMatteoL,DiMatteoR.Evidenceonthedeterminantsof Canadianprovincialgovernmenthealthexpenditures: 1965–1991.JHealthEcon.1998;17:211–28.

31.GiannoniM,HitirisT.Theregionalimpactofhealthcare expenditure:thecaseofItaly.ApplEcon.2002;34:1829–36. 32.CrivelliL,FilippiniM,MoscaI.Federalismandregionalhealth

careexpenditures:anempiricalanalysisfortheSwiss cantons.HealthEcon.2006;15:535–41.

33.López-CasasnovasG,SaezM.Amultilevelanalysisonthe determinantsofregionalhealthcareexpenditure:anote.Eur JHealthEcon.2007;8:59–65.

34.SchefflerR,SmithRB.Theimpactofgovernment

decentralizationoncountyhealthspendingfortheuninsured inCalifornia.IntJHealthCareFinanceEcon.2006;6:237–58. 35.BordignonM,TuratiG.Bailingoutexpectationsandpublic

healthexpenditure.JHealthEcon.2009;28:305–21. 36.Jiménez-RubioD.Theimpactoffiscaldecentralizationon

infantmortalityrates:evidencefromOECDcountries.SocSci Med.2011;73:1401–7.

37.CantareroD,PascualM.Analysingtheimpactoffiscal decentralizationonhealthoutcomes:empiricalevidence fromSpain.ApplEconLett.2008;15:109–11.