iNS-II'IUT{}'ùT

CiÊNCIAS SÖi:iAil;t4S

bs

3

B!BI..IÖ],ECAI

Ril

l,

x+

oi1-7

TheDeterminants of

SmallFirm

Growth

An

inter-regional study in theUnited

Kingdom

1986-90 Richard Barkham,Graham Gudgin, Mark

Hart

andEric

Hanvey4

Spatial Policy

in

aDivided

Nation

Edited by

Richard

T.Harrison

andMark

Hart

Cities

in

Crisis

3

Regional

Developmentin

the

1990sThe

British

Isles in transition Edited by RonMartin

and Peter TownroeSocio-spatial impacts

of

the economlc cnsls

in

Southern

European cities

6

The RegionalImperative

Regional planning and govemancein

Britain,

Europe and the UnitedStates

Urlan

A.

l(annop

2

Retreat

from

the Regions Corporate change and the closureof

factoriesStephen

Fothergill

andNigel

GuyEdited by

Jörg

Knieling

and

Frank

Othengrafen

5

An

Enlarged Europe

Regionsin

competition? Edited by Louis Albrechts, SallyHardy, Mark Hart

andAnastasios Katos

1

Beyond Green BeltsManaging urban growth in the

2lst

centuryEdited by John

Herington

Êl

Routledoe

$\

raytorarranciÉroupLONDON AND NEW YORK

;

First published 201 6 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OXl4 4RN and by Routledge

7l I Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an inprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Grotrp, an infonna business @ 20 I 6 selection and editorial rnatter, Jörg Knieling and Frank

Othengrafen; individual chapters, the contributors

The right ofthe editors to be identified as the authors ofthe editorial

matter, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been assefed

in accordance with sections 77 and,78 ofthe Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any fonn or by any electronic, tnechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in

any information storage or retrieval system, without perrnission in writing

fron.r the publishers.

Trademark nolice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or

registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation

without intent to infrirrge.

British Library Cafaloguing in Publication Data

A catalogne record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Ç6agress Cataloging in Pttblicalion Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN: 978-l-138-85002-6 (hbk)

ISBN: 978- I -3 I s-72504-8 (ebk) Typeset in Times New Roman by Wearset Ltd, Boldon, Tyne and Wear

This

book is

the result of

an

international

conference funded by the

German Academic

Exchange

service

(Deutscher

Akademischer

Austauschdienst) and the German Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges

Amt).

,,;l',\\.,'i{l

/u*

;'

,;i i,,.r...1:ìi

2-.. .,,,,,

.iili;li,

-

:.,'

t,;r;i\,:iì:'

"

.A

Mtx FSC 16!ponslblo aourærFSC. C013604 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

_t

J

t

!

T

i -_;-I

Contents

List offigures

List

of tables Notes oncontributors

Acknowledgementsxvt

xviii

xix

xxviii

1

Cities

in

crisis: setting

the scenefor

reflecting

urban

andregional futures

in

timesof austerity

JÖRG

KNIELING,

FRANK OTHENGRAFEN,AND GALYA

VLADOVAPART

I

Cities

in

crisis: theoretical

framework

ll

2

The

economic andfinancial crisis: origins and

consequencesHELENA CgUIIÁ, MONTSERRAT GUILLEN, AND

MIGUEL SANTOLINO

13

3

Socio-potitical

and socio-spatialimplications

of the economiccrisis

andausterity politics

in

Southern European

cities GIANCARLO COTELLA, FRANK OTHENGRAFEN,ATHANASIOS PAPAIOANNOU, AND SIMONE TULUMELLO

27

4

Crisis

andurban

change: reflections, strategies, and approachesJöRc KNIELINc,

UMBERToJANIN

RIvoLIN, loÃo sstx,qs,

ANDGALYA

VLADOVA48

PART

ITOrigins

of the crisis and its socio-spatial impacts

on

Southern European cities

7l

5

The neoliberal model

of thecity

in

Southern

Europe:

acomparative approach

toValencia

andMadrid

JUAN ROMERO, CARME MELO, AND DOLORES BRANDIS

xiv

ContentsContenls

xv

6

Governance and local governmentin

theLisbon Metropolitan

Area:

the effectsofthe

crisis on thereorganisation

of

municipal

services andsupport for

peopleJoSÉ

LUÍS

CRESPo,MARIA

MANUELA MENDES, AND JORGE NICOLAU13

Rethinking

Barcelona:

changes experienced as aresult

of

social and economiccrisis

¡oeQuÍN

noonicusz Álvenez

239 94

L4

From

crisis to crisis: dynamics

of change andemerging

models

of

governancein

theTurin Metropolitan

Area

NADIA

CARUSO, GIANCARLO COTELLA,AND

ELENA PEDE257

7

Athens,

acapital

in

crisis:

tracing

the socio-spatialimpacts

KONSTANTINOS SERRAOS, THOMAS GREVE,

EVANGELOS ASPROGERAKAS, DIMITRIOS BALAMPANIDIS AND ANASTASIA CHANI

116

15

Urban

rescaling:

apost-crisis

scenariofor

a Spanishcity

Valencia

andits

megaregionJOSEP VICENT BOIRA AND RAMON MARRADES

278

8

A

new landscape ofurban

social movements:reflections

onurban unrest

in

Southern European

citiesFRANK

orHENcRAFeN, luÍs

DELRoMERo

RENAU, ANDTFIGENEIA KOKKALI

139

16

Urban

decline, resilience, and change:understanding how

cities and

regions adapt to

socio-economic crises THILO LANG296

PART

III

Urban

planning and the economic crisis

in

Southern

European cities

PART V

Conclusion

311155

9

Urban

planning

andterritorial

managementin

Portugal:

antecedents and

impacts

of the 2008financial

and economiccrisis

JOANA MOURÀO AND TERESA MARAT-MENDES

17

Learning from

eachother:

planning

sustainable,future-oriented,

andadaptive

cities and regionsJÖRG KNIELING, FRANK OTHENGRAFEN, AND

GALYA VLADOVA

313

157

Index 327

10

Greek

citiesin

crisis: context,

evidence, response 112ATI]ANASIOS PAPAIOANNOU AND

CHRISTINA NIKOLAKOPOULOU

11

Crisis

andurban

shrinkage

from

anItalian

perspective CARLO SALONE, ANGELO BESANA, ANDUMBERTO JANIN RIVOLIN

190

PART

IV

Crisis

asdriver

of

change?

21s

12

Potentials

andrestrictions

on thechanging dynamics

of thepolitical

spacesin

theLisbon

Metropolitan

Area

¡oÃo

selxes,

stMoNE TULUMELLo,

susANA

coRVELo,

AND ANA DRAGO

217

Ë

T

:

i :ll$

*

12

Potentials and

restrictions

on the

changing dynamics of the

political

spaces

in

the

Lisbon

Metropolitan

Area

João Seixas, Simone Tulumello, Susana Corvelo,

and Ana

Drago

Introduction

The current chapter supplies empirical evidence to extract and a

critical

analysisof how

the economic crisis and itspolitical

management has affected theevolu-tion ofEuropean

urban regions.This

will

be carried out through an analysisof

the recentevolution, both

geographical andsocio-political,

of

the main

Poftu-guese urban region, the Lisbon Metropolitan Area

(LMA).

The chapter proposes some insightsinto

the ongoing discussion about the relevanceof

territorial

andurban dimensions

to

the knowledge and interpretationof

the present Europeancrisis,

that

is, the

economic

crisis and

its

socio-political

consequences.It

emphasises the importanceof

the differentiated spatial impactsof

the crisis butalso

ofthe

pressures and conflicts resultingfrom

the intersectionofthe

reactionsof

the

different

political

stancesand

scales (Othengrafenet al., this

volume; Pinho, Andrade,&

Pinho, 201 1 ; Hadjimichalis, 201 1 ; V/erner, 2073).These are

particularly

painful

times

for

Southern Europeanterritories

and societies due to the conjunctionofthe

financial crisis and thepolitical

responsesof

the EuropeanUnion (EU)

andindividual nation

states.The

reaction was to put in place austerity measures that deeply disrupted social, economic, andterri-torial

fabrics

aswell

asthe

fundamentalsof

inclusive and

sustainably driven societies.This clearly

shows that thecrisis is no

longer,if

it

ever was,mainly

driven

by

public

andfinancial

reasons,but

it

has insteadmultidimensional

andstructural

political

bases.Amongst several contemporary

crisis

landscapes, Europeancities

are thelocus wherc

pressuresand

changes aremost evident.

A

relevant part

of

theEuropean

crisis

showsto

be theresult

of

the crashof

anold

economic order, supported onlarge

amountsof

non-securedurbanisation credit (financial,

ter-ritorial,

and environmental credit),

with

growingly

unregulated financial

markets.

At

the

sametime,

andnot surprisingly,

it

is

the urban fabrics

that witness thematerialisation of

newpolitical

andcivic

cultures.If

this

is truein

thewider

European landscape,the history

andposition of

the

Meditenanean urbanterritories

makestheir

presentrole

particularly

relevant. The

European Commission(2011) itself

recognises that citieswill

reinforce their crucial

roleas main drivers

for

transition.

Their very nature

makes

them

places

for

218

J. Seixas et al.connectivity, citizenship,

creativity,

and innovation;

all

fundamental

charac-teristics

for

facing the

challenges ahead.However, 'the

Europeanmodel

of

sustainable

urban

developmentis under threat'

(ibid.:

p.

l4):

onethat

is

notonly arising from the

upheaval

of

the crisis, but

also

from the

mainstreampolitical

andfinancial

responses to thecrisis. This

threatbrings

new pressuresto

bear on theurban

socio-economic andenvironmental

ecosystems andpar-ticularly

on the growing

spatialpolarisation, both

in

income

andin

access to urbanfunctions. Moreover,

it

hides otherdifficulties for

theeffective

develop-mentof

new modelsof

social and economic progress,in parallel

with

the needfor

ecological regeneration.This

chapterwill

study

the links

between

the

Europeancrisis, its

urbanimpacts, and the applied austerity measures, and

will

discuss selected innovativepolicies

in

their different

scales. Theselinks

will

be

studied against the back-groundof

the (re)shapingof

thepolitical

spacesof

theLMA.

Themain

hypo-thesis is that the urban trends

within

(and beyond) the crisis have to be dissectedalong three

different

dimensions. First, how the spatial impactsof

the economic recessionare transforming inclusion and exclusion pattems

within

the

urbansystem. Second,

how

related'anti-crisis' policies

are expanding those pattems, and how thepolitical

economicsfor

austerity are reshaping capacities andprior-ities at the

local

scale.Third,

how thecity's political

andcivic

realms react andreconfigure themselves,

thus

changing urbanpolitical

systems,possibly

in

anenduring way. Lisbon

will

thus be shown as anillustrative

example of the emer-genceof

new

political

culture(s), whose characteristics are especially complexand inherently contradictory. I

Beyond

this

introduction, the

text is

structuredin five

sections.In

the

nexsection, a

critical

perspective on the crisis and the applied austerity measures isintroduced, complementary

to

the understandingprovided

by

geographical andlongitudinal

analyses.

The third

section

analyses

the

context

of

political

responses to the crisisin

Portugal to give acritical

understanding ofconnections betweennational, austerity-driven

pressuresand local

reactions.

The

fourthsection includes some variables to serve as a basis

for

exploring the nature of thevarious impacts

of,

andtheir

distributionwithin,

theLMA.

In

theflfth

section, acritical

analysisof

themain

driversof

change at theinstitutional, political,

andcivic

level

will

be

conducted,before some concluding remarks

in

the

final

section.The

European crisis:

a

critical

perspective

Most of

the

Europeanpolitical-institutional

discoursesexplain

theorigins

andthe persistence

of

the Southern European componentsof

the crisis as being theresult ofdecades

ofprofligate

and under-accountablepublic

spending, connectedwith

allegedly unsustainable welfare systems(Blyth,

2013). From theseperspec-tives

arose the mainjustifications

for

the present austerity-drivenpolitical

eco-nomics, considered as the

only

way to consolidate national budgets and to createfuture conditions

for

economic recovery (Krugman, 2012).Changing dynamics of

political spaces

219According to

Blyth

(2013), the ongoing crisis should not be understood as apublic

sector one, but instead as a crisis of the private sector,which

is being paidfor by public

funds. The sovereign debt crisisis

thus seen, above all, as a con-sequenceof

the useof public

fundsin

order tobail

outfinancial

institutions and save the Europeanfinancial

system.Prior to

thecrisis,

sovereign debtin

coun-tries such as Spain and Ireland were

well

belowcritical

thresholds, amounting in 2007,to

26

and 12 per cent debt/Gross Domestic Product(GDP) ratio

respec-tively (Blyth,2013).

Other Southern European countries, such asItaly,

Greece, and Portugalhistorically

had high debts. Yet, there exist different reasons for theeconomic crisis

in

the Southern European countries andin

Ireland. These are to be found, on the one hand,in

the explosionof

large real estate bubbles and cor-respondentbanking

systems consideredas

'too

big

to

fail'

and,on

the

other hand,in

the consequencesof low

growth

since the year 2000, ageing societies, andpolitical-institutional

incapacityfor

structural changes.In

the

monthsfollowing

the

Wall

Street collapseof

2008,after the

fall

of

some

of

the so-called'too big

tofail'

banking institutions andpublic

revelationsof

malpracticein

the financial markets, far-reaching analyses on theunsustaina-bility of

thefinancial

systems cameto

the fore, togetherwith

two

mainrecom-mendations

to

national

governments:

to

sustain

and

intervene

in

bankinginstitutions at

risk,

reassuringfinancial

markets, andpreventing public

panic;and

to

launch large

amountsof

public

investmentto

allow

faster

economicrecovery.

By

the endof

2008, the EU had approved an ambitious Recovery Plan(Commission

of

the

EuropeanCommunities,

2008),

envisioning

a

€170,000million

investmentfrom

member states. However,only

afew

months after the debate about the needto

regulate markets was over, the needfor

austerity wasadvocated

by

intemational institutions,

governments,and

mainstream think-tanks(Peck,20l3).

Austerity

isa form

of

voluntary deflation

in

which

the economy

adjuststhrough

thereduction

of

wages, prices, andpublic

spendingto

restore competitiveness,which is

(supposedly) best achievedby

cutting

the state's budget, debt anddeficits.

Doing

so, its advocates believed,will

inspire business confidence.(Blyth,

2013:p.2)

However, the cuts

in

the welfare

state andthe fiscal

pressureson

the

labour market expanded inequalities andpoverty,

neitherreducing national

debts noreasing the recession and stimulating economic growth (Krugman, 2012).

Roitman (2014) explores the

naratives

about therisk of

the collapse ofpolit-ical and economic systems as the

justifrcation for

devaluation, hence austerity.If

the

curent

crisis

is

oneof

the neoliberal

economy andof

its

financialisation, austeritymay be

understood asthe

way for

neoliberalism

to

survive

its

owncrisis: 'what might

be incautiously labelled"the

system" was brazenly rebootedwith

moreor

less the sameideological

and managerial software, completewith

mostof

the bugs that had caused the breakdownin

thefirst place'

(Peck, 2013:220

J. Seixas et al.necessary

to

understand the European crisis.According to

Harvey (2005),neo-liberalism

is

aproject

for

the restructuringof

capitalism and the restorationof

the conditionsfor

capital

accumulation. However, thespecificity

of

theneolib-eral

dynamicsis

showing that

the

stateis not

being

reduced,as

in

classicalliberal

conceptions,but

rather re-engineeredin

orderto

enableparticular

formsof

competition (Wacquant,2012).A

contradictorymix

of regulation andderegu-lation patterns are therefore coexisting (Brenner, Peck,

&

Theodore, 2010; Rod-rigues&

Teles,201l):

(financial) markets are deregulated and, at the same time,nation

states interveneboth

in

financial

andeconomic

landscapesin

order

toprimarily

favour capital

accumulation,through the

managementof public

ser-vices and new forms of

public-private

partnerships.A

critical

understanding of neoliberal dynamics is relevant to understandwhy

crisis and austerity matter so much

for

cities,for two

reasons. On the one hand,the central

role of

urban (re)production andof

temitorial space restructuring has been at the heartof

the developmentof

neoclassical and neoliberal approachessince

the

1980s,a

deeply debated issue(Brenner,2004).

The vast production,and consumption,

ofurban,

suburban, and peri-urban territories is understoodby

many as a coherent and long-term strategy (Peck, Theodore,

&

Brenner, 2013).Although

there is a significant varietyin

local and regional trends, mostly relatedto

the

landscapeof

institutional,

governance, andpolitical

contexts,which

hasjustified

severalcritiques

of

the

usefulnessof

neoliberalism as

a

generalisedtheoretical concept (Baptista, 2013), some common trends

in

urban governance can be discerned, stemming around concepts such asterritorial

competitiveness,city

marketing, public-private

partnerships, outsourcing,

and

privatisation(Sager,

20ll).

On the

other

hand,many

seethe

economic

crisis

(especially

in

SouthernEurope) as

the culmination

of

long-term uneven development pathsdriven by

neoclassicalpolicy-making (Hadjimichalis,

2011;Blyth,

2013), clearlyexempli-fied

by

housingpolicies

characterisedby

the

shift from

theprovision

of

bothleasing and

public

housing to the support of private ownership (i.e. theThatcher-ite 'right

tobuy').

This, togetherwith

the erosion of welfare,forced people in the United States and elsewhere to

rely

ever more onhome-ownership as

a

substitutefor

social risk-sharing

mechanisms.Individual

efforts

to

replace

public

cash and

public

selices with

homeownershippushed home prices up to clearly unsustainable levels.

(Schwartz, 2012:

p.

53)The resulting private debt and housing bubble allowed enornous leverage

in

fin-ancial markets, hence triggering the financial bubble to burst

(Blyth,

2013).It

can be seen that the main categoriescunently

being applied to an economyin

timesof

crisis are basically the same as they were before 2008: an emphasison the need

to

aftractforeign

investmentwith

aglobally

competitive discourse,following

international

organisational trends(Oosterlynck

&

Gonzâlez,2013). Production and consumption are not solelywithin

the urban/metropolitan spaceChanging dynamics

of

political spaces

221in

theglobal

economy,but

the mainstreampolitical

agenda takesthe

city

as anodal element

for

commodity creation: urban renewal projects, real estatedevel-opment, state incentives towards homeownership, privatisation

of public

spaces, and the keyrole of financial

institutionsin

new urban regìmes (Peck, Theodore,&

Bremer,

2013).In

this

sense,it

could be argued that the interpretationof

thenature

of

the presentcrisis could

alsoimply

acritical

examinationof

tenitorial

goveürment instifutions.

Setting

the context: the austerity agenda and its impact

in

Portugal

The outbreak

of

thefinancial

crisisin

2008 marked the beginningof

a profoundchange

in

Poffuguese society andpolitics.

As far as thepolitical

responses to thecrisis are concerred,

different or

even contradictory approaches, aswell

as diÊferent

sequential phases, canbe identified

(Pedroso, 2014):policies

to

sustainthe

'system'

and to relaunch the economy, the implementationof

austerity meas-ures andfinancially

driven policies, and the developmentof

austerityto

acom-plete, and now

ideologically

driven, scale.Aligned

with

earlypolitical

reactions to the crisisby

European institutions (see previous section), the Portuguese goverrìment issuedpublic

debt guarantees to theprivate banking sector and took control

of

investment banks, whose subprime andfurther unaccounted

for

financial activities were madepublic.

A

seemingly neo-Keynesian agenda was presentedfor

the 2009 budget:2public

servants were givena 2.9 per cent wage increase, and an ambitious progranìme

of public

works was announced, mostly conceming transport infrastructure. However,by

2010,all

thatcame

to

an

end:

public works

investmentwas

stopped,tax

revenue shrank considerably, andpublic

spendingin

automatic stabilisers (namely unemploymentbenefits) increased.

As the

euro crisis was unfolding,

Portuguesepublic

debt interest rates climbed and the fiscal deficit grew. Portugal wasofficially

in crisis.As 2010 went

by,

austerity policies made their wayin,

and a sequence of fiscal adjustmentpolicies were

implemented: taxeswere

raised, pensions and publicsector salaries frozen, and

new

legislation was adoptedwhich limited

access to social benefits.In April

2011, dueto

Parliament's rejectionof

a new adjustment package, the Socialist PrimeMinister

requested extemal financial aid, and theso-called

'Troika'

of

extemal borrowers, the Intemational Monetary Fund, the Euro-pean Commission, andthe

European CentralBank,

imposeda

large-scale and severe budgetary and political-administrative memorandumon

national politics.Two

months later, aright-wing

government was elected. The full-scale austerity that allowed Portugal to access financial assistance had tobejustified

by apolitical

narrative

of

Portuguese economic andpublic policy inability. The

diagnosis wasbuilt

on a distorted representationof public

and household spending pattems that allegedly led to unsustainable national indebtedness.However, this

interpretationcould be

easily refutedby

a

closerlook

at themain figures

of

the national

debt(Abreu

et

al.,2013).

Portuguesepublic

debt rose steadily since the mid-1990s, reaching theEU's

average by 2005. However,222

J. Seixas et al.the major indebtedness happened

only

after 2008, much ofwhich

was due to theinternational

financial

crisis.At

the sametime,

it

could

be seen that household indebtedness remainedrelatively limited:

in

2010, about 63 per centof

thePor-tuguese population had

no

credit debt and 80 per centof

household debts were related to mortgage loans. Despite the current economic crisis,in

2013,only

6.6per cent

ofthose

loans reported a credit default.This

shows that the Portuguesebanking system

mainly

contracted mofigage loans to middle-class families.Over the last

decade, Porhrgal sufferedfrom

major

shocksthat

hada

pro-found

impact onits

ability

to

competeintemationally:

the adoptionof

a strongcuffency, the euro, the impacts of global liberalisation and

of

Chinese exports ontraditional

Poftuguese export markets, and theoil

shockin

the mid-2000s.All

this led to the so-called'lost

decade' (asit

was commonly termedin

the media)for

the Portuguese economy.From

2000to

2010, PortugueseGDP grew

at anannual average rate

of

1 per cent.According to

Reis and Rodrigues (201l)

the reason was that Portugal had been respondingto

extemal shocks through apro-gressive

shift

towards an economic model grounded onlow

wages and growing inequality rather than on investmentsin

sectorswith

high added value.Without acknowledging this last issue, the Troika's therapy consisted mainly

of

drastic cuts in public spending/investment as

well

as restructuring and liberalisation policies. State administration, public services, and public salaries were to be signifi-cantlycut

and reduced,public

spending on health and education was drasticallyreduced, and a programme

for

civil

service redundancies was implemented,result-ing in a reduction ofaround 50,000 posts. Poverty and inequality reduction policies,

as

well

as unemployment benefits,were

alsocut.

A

mix

of

tax

increases was imposed overwork

and pension revenues aswell

as on consumption. Fudhermore,a

vast privatisation programme was implementedin

strategic economic sectors:public transport, energy and communications, postal services, and airports.

The main social and

economic

effects

of

the

'adjustment

programme'imposed

by

theTroika

cannot be understated (Abreuet

a1.,2013):from

2011 to2013

PortugueseGDP

hasfallen

5.9

per

cent.

In

2073, private

consumption retumed to the levelit

was atin

2000 andpublic

consumptionfell

to the levelof

2002.

As far

as investment rates are conceüted, bothpublic

and private, there isno memory (i.e. no

statistical data)of

such a collapse.In

thefirst

trimesterof

2013,the

net investmentin

the Portuguese economy was 20 per cent lower thanin

1995, when this indicator was collectedfor

thefirst

time. From 201I

to 2013,national available income dropped by 4 per cent, whereas

work

income suffered a significant reductionof

9.7

per cent.3 These figurescould

be interpreted as alowering-wage

pressuretypical

for

a

recessiveeconomy,

but were

certainlyinduced both by the continuous wage cuts

in

thepublic

sector, undertaken by thegovernment since 2010, and the effects of massive unemployment.

The next section

will

focus on theLMA

for

our empirical analysis. Economic,territorial,

and socio-demographic trendswill

be presented, thus interpreting theeffects

ofthe

economic crisis and correspondingpolitical

reactions through cor-responding data analyses.Changing dynamics

of

political spaces

223The Lisbon

Metropolitan Area:

crisis

in

motion4

Economic

perþrmance

andterrilorial

effectsAs a

capital

city

of

a

centralised andrelatively small

country, the

LMA

has always been a strongholdfor

the performanceof

an entirenation (Table

l2.l).

Its

concentrationof

population, production,

and consumption has attracted themost national resources and Research and Development

(R&D)

investment. TheLMA

gathers a significant partof

Portugal's productive resources:27 per centof

thecountry's

inhabitants,5 26.2 per centof its

employment, and 37 .2 per centof

national Gross Value Added

(GVA).

The

LMA

has beenstrongly

affectedby

the economic crisis

andthe

sub-sequent austerity measures,but this

has happenedin

apparently contradictory ways, as evidentin

the trendsof

the Regional Development Composite Index6 (seeTable

12.2),when takinginto

account the yearsprior

to and after the begin-ning of the implementationof

austerity measures (2010 onwards). Thecompetit-iveness component

of

theIndex

shows a slight improvement pattern upuntil

the year 2010, clearly contradictedby

the cohesion and environmentalquality

com-ponents.

A

more careful

analysisof

the

competitiveness component helps to understandits

apparent recovery.All

variablesþer

capitaGDP, qualified

per-sonnel, exports growth,R&D

intensity, or the prevalence of knowledge intensiveactivities)

are less reactive,taking into

account theLMA

specialisation profile,7whereas

an intemal market

dependenceis

markedly

balancedby

the

exportsTable

I2.l

Some data on Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA)20t

I

Portugal LMA GVA (€ millions) Employees (thousands) Exports (€ millions) GDP %(PT:100)

Productivity (€ thousands-

2010) t49,268 3,843 42,870 100 30.7 55,483 1,369 14,r68 r39.6 38.7Source: elaboration of authors on data: INE; CCDR-LVT

Table 12.2 Regional Development Composite Index

RDCI

Competitiveness Cohesion Environmental quality Portugal LisbonMetropolitan

2011Area

2010 2008 2006 105.33 106.48 106.79 L07.2r 100 1r3.26 1 1 3.93 I 13.18 113.01 100 103.99 r04.64 r06.57 t07.78 100 98.01 100.20 100.00 100.27 100224

J. Seixas et al.profile,

thusgiving

a senseof

growth,

while

the behaviourof

macroeconomic variables is not so positive.During

thefirst

phaseof

the

economiccrisis (2007-2010),

rather moderategrowth was registered in the

LMA

before the economy started to contract: exportsectors and a

still

contained unemploymentgrowth

(8.4 per centin

2007 ; 9 .2 percent

in

2009) meant better performing variables when compared to the nationalaverage.

Also,

the predominanceof

the service sector andtourism activities in

the region seemed

to

have contributedto

balancing the economic depressors.It

was during the second phase, after 201 0, whenall

componentsof

the Index were lowered.The analysis

of

further

economic performance variables helpsto

understandthe real effects

of

the

economiccrisis

and then thoseof

the

applied austeritymeasures: major private and (especially)

public

investment drops,while

theaus-terity

discoursesgrew,

together

with

cuts

in

public

spendingto

supposedlyrestore competitiveness.

The trend

of

investmentis

evident

in

the figures

of

Gross Fixed Capital Formation,s which dropped by almost 20 per cent from 2008

to

2011.Around

65,000 companies (17.6per

cent) disappeared befween 2008and2072,

shifting

the survival rate to below the national average.The real estate and construction sector was one

of

thefirst to

sufferfrom

thecrisis, as evident

in

the dropin building

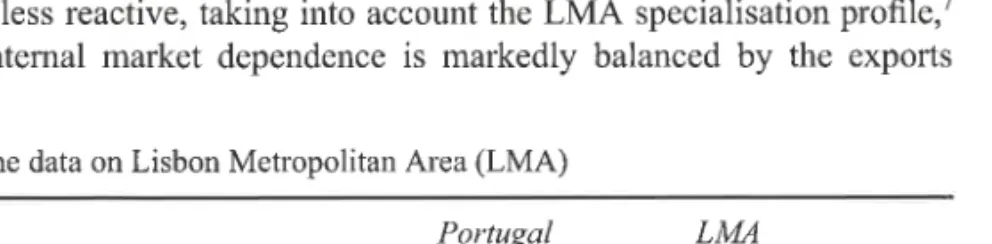

sale contracts(Figure

12.1). Today, theLMA

is

a densely urbanised system as theresult

of

several decadesof

preval-enceof

urbanisation

economics.This

is

quite

noticeable

from the

levels

of

growth

in

terms

of

inhabitants anddwelling

stock. According

to

the

census, between 2001 and 2011, a 6 per cent populationgrowth

resultedin

agrowth

of

the

built

areaof

around

14.2 per cent.After a

sustainedgrowth

in

the

early 2000s, constructionworks

in

both districts

of

the

LMA

(Lisbon

and setubal)dropped by

halfover

a few years (2007-2012).It

should be noted that thefinan-cial

breakdown interuenedin

an ongoing process(Figure

12.1): the numberof

building

sale contracts stoppedgrowing

Ln2006 becauseofthe

burstofthe

con-struction bubble and

the growing

effectivenessof

planning regulations

afterdecades

ofunregulated

urbanisation (Fernandes&

Chamusca,2014). Thecon-traction

of

thebuilding

sector strengthenedregional polarisation,

especiallyin

the setúbal district where, 'municipalities

characterisedby low

education andskill

levels,

with

structural

issues

of

social inclusion and

job

insecurity,dependent

onjob

segmentsin contraction,...

show a stronger sensibility to early effects ofcrisis'

(Ferrão, 2013:p.256,

translated).At

the sametime,

mortgage insolvencies roseby

49.5per

centfrom

2009 to2013.

Although

recentpolitical

discourses have beenpinning

the blamefor

the Portuguese crisis on families for their excessive indebtedness, the growth of private debt can largely be explainedby

the lackof

an overallpublic

housingpolicy for

decades.In

2010, housing loans accountedfor

80 per centoffamily

indebtedness, and homeownership was encouragedby

tax benefits and a state-subsidised creditsystem

for

house purchase that lastedfor

more than 30 yearsuntil

2010. Thisper-vasive system created a specific articulation,

linking

state policies,family

invest-ments/indebtedness, and credit-financial institutions (Santos, 20 I 3).Changing dynamics of

political spaces

2252004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

2012 12,000 10,000 8,000 6,000 4,000 2,0002003

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

2011Figure 12.1 Construction and real estate in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (source: authors' elaboration on data from INE).

S ocio-demographic trends

The

LMA

is ahighly

skilled region,with

the largest universities in the country, thehighest number

of R&D

centres and a considerable numberof

innovative com-panies.V/ith

16.8 per cent ofinhabitants holding higher education degrees (againsta national average

of

11.8per

cent), anda

slight

increasein

the proportionof

young peoplein

the population(from

14.9 per centin

2001to

15.5 per centin

2011),

it

is nonetheless an ageing regionwith

decliningbirlh

rates. Over the lastten years, the percentage

of

the elderly (65 and over) rosefrom

15.4to

18.2 per centof

the overall population, notwithstanding afairly

young immigrantpopula-tion.

These trends arejust

as signiflcant when lookedat from

the perspectiveof

labour

marketfigures and

their

intensified characteristics throughoutthe

crisis years.In

fact, the effectsofthe

crisis and thepolitical

responses to them are veryclear here,

with

a reductionof

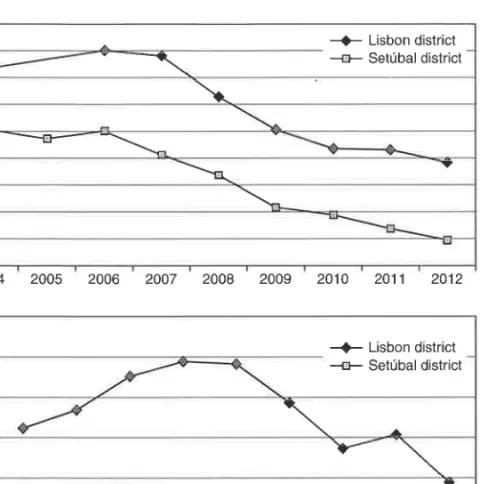

c.180,000 employees between 2008 and 2013. TheU)

:

o 3 c o o f 6 c oo

a

Ø Þc (ú :f o -c g> o (u c o o oõ

în o) c=

d] 4 4 3 ,J 2 2 1 1--<F

Lisbon distr¡ct--+-

Setúbal district\

---{l.,'--v

-\q

\*

*

Lisbon district-c-

Setúbal district\

LF

?226

J. Seixas et al.unemployment rate more than doubled

in

the 2008-2013 period(from

7.9to

lj.3

per cent), and the increase became steeper since the 2011

bailout (Figure

12.2),confirming the depressive effects

of

austerity.In

particular, the youthunemploy-ment rate grew

from

16.9 per centin

2007 to 22.7 per cent in 2010, then balloonedIo 42.4 per cent

in

2013. The figuresof

registered unemployed atpublic

employ-mentselices,

which

are updatedmonthly

andallow

trends to be captured morequickly, are consistent

with

these findings: registered unemploymentin

the LMAestarted

to

rise at alow

pacejust

after 2008, growingdrastically

after 201012011, when the cutoff

measures by central government started.Furthermore,

risk of

poverty

has beenrapidly

increasing since 2009, rapidlyinverting a slightly

positive hend traced since the beginningof

the decade as aresult

of

steady socialpolicies. According

to

the 2013

EU

Statisticsfrom

theIncome and

Living

conditions

survey, 18.7 per centof

the populationof

portugal was at risk of poverty, notwithstanding social transfersin2012,

as against 17.9 perChanging dynømics

of

political spaces

221cent

in

2009. Thegrowth is

much more significant when using a time-anchored rate(Table

123).10 Therisk

of poverty ratefor

the unemployed populationin

thecountry was 40.2 per cent

in

2012, a riseof

almost four points when compared to 2009. Under the austerity agenda, a renewed rise of asymmetry in income distribu-tion since 2010 has inverled the trends of the previous decaile, which were charac-terised by a steady reduction in economic inequalities (Alves, 2014).Even though there is no consistent data

for

poverty at the regional level, suffi-cient knowledge existsof

the fact

that urban areas have been comprehensively afflected.In

thefirst

phaseof

the crisis, there was a significant increase (approxi-mately 66 per cent) in the number of beneficiaries of Social Integration Income (SII,a social security benefit for poorer families) in the

LMA.

Since 2010, however, the austerity measuresrr have reduced these figures drastically,in

paradoxical contrastwith the growth in unemployment (Figure 12.3). Moreover, significant ageing trends among the

LMA's

population, a subsequent rise in the number of pension benefici-aries, and thelow

valueof

average pensionsin

the Social Security system (C426) (Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo,2013) makes the elderly a

highly

vulnerable social group, at highrisk of

poverty.The

deep cutsto

the

'Complemento Solidário paraIdosos'

(an important social benefit for the elderly), which the cenhal govemment has imposed since 2011, have increased the percentage ofthe population over 65 years old exposed to poverty.The

austerity measures andthe lowering

of

wages andfamily

income havealso hugely affected

mobility,

especially

in

a wide

and

dispersed urbanisedregion

like

theLMA.

TheLMA

is characterisedby

significantdaily

commutingand semi-polycentric travels:

Lisbon-City's

population

(c.

600,000

residents)-80

2007 2008 2009 201 0 2011 2012

Figure 12.3 Demographic trends

in

Lisbon Metropolitan Area (source: autho¡s'elabora-tion on data from INE).20 18 16

s14

2 0 60 40 20 20 40-60,

(t c) õ it C) c o) Ø U) 200'1 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 600,000 500,000 100,000 0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012Figure 12.2 unemployment rate and beneficiaries

of

social Integration Income(sll)

(number) (source: authors' elaboration on data from INE, II/MSESS (http:// www4.seg-social.ptlestatisticas)). 400 300 ø .9 o. (ú o) E o J 200,000

*-

Portugal--+

Lisbon Metropolitan Area 17.3'16.3

t5./

*-

Portugal-a-

Lisbon Metropolitan Area19,79 10,465 -774

x-*

Demographic balance-s-

Natural balance----

lmmigration---

Emigration 109228

J. Seixas et al.Table 12.3 Portugal indicators (EU-SILC, 2010-2013)

Source: elaboration ofauthors on data: INE/Eurostat. Po: estimated value.

almost

triples

during

working

days. Between2008 and 2010, the number

of

urban

and

suburbanjoumeys on public

transport

were

stable

while,

in

the2010-2012 period, a drop

of

23per

cent happened.It

could

be assumed that,among the reasons

for

this,

are the purchasingpower

loss causedby

the

eco-nomic crisis, the

cutbacksin

the

public

metropolitan

transportoffer,

and thesignificant fare increases (c.24 per cent

in

theperiod

2010-2012),which

in

theLMA's

case, were decided by the central government.Finally,

the emergent emigrationflows

should be pointed outfor

theirpoten-tial

consequences. Since 2010, there has been a complete inversionof

migrationtrends in the

LMA:

immigration

flows have fallen drastically (the values of 2012being

half of

thosein

2009),whilst

emigration, especially among young people, has risen abruptly.ln2012,

the numberof

emigrants was three times higher thanin

2009.In20ll,

a negative demographic balance was recordedfor

thefirst

timein

decades. These trends prefigure apotential further

consequenceof

the crisis: lossof

human capital becauseof

the increasingly ageingpopulation

andespe-cially

because of the net emigrationof

skilled and educated workers.Recent

political

and

civic

changes

in

the Lisbon

Metropolitan

Area

This

sectionwill

provide

an overviewof

parallel patternsof

socio-political andcivic

reactions, changes, and restructuring dynamicsin

theLMA.

Caught befween European and national austerity pressures and multiple local and civic differentiatedresponses, the

LMA

shows a complex,if

not contradictory,political

landscape.Between

nationøl

reforms and locøl responsesPortugal remains one

of

the mostpolitically

centralised societiesin

Europe.It

is the second most non-micro EU country (after Greece)with

the lowest proportionof

subnational(i.e.

regionalplus local)

public

expenditure.This

accountedfor

Changing dynamics

of

political

spaces

229around 15 per cent of

public

expenditurein20ll,

a numberlying well

below theEuropean

Union

averageof

c.25 per cent (Dexia

&

Conseil

de Communes etRégions d'Europe, 2012). Moreover, the regions, accounting

for

around 4.5 per cent ofpublic

expenditure, have nopolitically

autonomous governments, but are localised bodiesof

the national government (Nanetti, Rato,&

Rodrigues,2004). This centralised pattern is the main reasonfor

the constant weaknessin

the local administrations (Seixas&

Albet, 2012).The

scarce resources are now even morecurtailed

by

thefiscal

stress inducedby

the economiccrisis

and, aboveall,

by thereduction

of

national

transfers since 2010.As

a result, municipal

budgetswithin the

LMA

have

seen,

with few

exceptions, steep reductions

since 2009/2010 of20-30

per cent.12In

addition to the budget cuts, the national govemment has been carrying outfiscal

and administrativereforms

of

territorial

powerswithin

theframework

of

austeritypolicies.

First, a cut

of

municipal economic

andreal

estate taxes isenvisaged

in

the medium

andlong

term.

Second,Laws

2212012 and 75/2013represent

further

centralised steps towards thecurtailment

of

local

governmentcapacities and autonomy.

Law

2212012, regarding administrative reorganisationof

municipalities, targets expenditure cuts through theeliminationof

27 per centof

theexisting4,260

parishes.13 TheLaw

gavemunicipal

assemblies 90 days to elaborate a proposalfor

internal reorganisation and establish the parametersfor

it.

The national associationofparishes

has contested thereform,

advocating that the reorganisation should have been grounded onvoluntary

aggregations ratherthan

on

demographic parameters (AssociaçãoNacional de

Freguesias, 2012). Fourteenof

the 18municipalities in

theLMA

decided against the administrative reorganisation andtwo

(Sesimbra and Sintra) did not submit any proposalwithin

the given terms.

As

a result, aworking

group establishedby

the national parlia-ment imposed administrative restructuringon

14municipalities,

whereasin

twocases (Sesimbra and Alcochete) the

former

organisation has been kept because thesetwo

abidedby

the parameters.In

other words, protests and resistance had no effect. Lisbon and Amadora chose a different approach and outlined reorgani-sation proposals.In

Amadora, the reorganisation was basedon

a demographicstudy,

which

aimedto

achieve an equitabledistribution

of public

services, and also on a consultative process that received around 1,000 contributions (CâmaraMunicipal

de Amadora, 2012). Themunicipality

ofLisbon

had beenworking

onadministrative

reform

since 2009 and could thusforestall

the nationallaw with

its own temporal terms (see the

preliminary

study, developedby

amultidiscipli-nary scientific team

in

Mateus, Seixas,&

Vitorino,

2010). The reductionof

thenumber

of

parishes(from 53

to

24)

wasjust

one

steptowards

an

all-roundenhancement of urban governance

quality.

The main aim was to transfer compe-tences to the parishes,which

previously hadvery

little

administrative andpublic

management capability: management and maintenance ofpublic

spaces, issueof

permissions and licences, planning and management

of

neighbourhood services, andpromotion of cultural

and social programmes. Themunicipal refotm

under-went

a

consultative

process,which

received

more than 7,000

contributions (Mateus, Seixas,&

Vitorino,

2010; CâmaraMunicipal

de Lisboa,201l).

2009

2010

20tI

2012 (estimated)At risk of povefiy rate before social transfers (%)

At risk of povefty rate after social transfers (%) Time-anchored at risk ofpoverty rate (reference

income:2009) (%)

Severe material deprivation (%)

At risk of poverty population (%) Gini coefûcient

Inequality on income distribution (S80/520) Inequality on income distribution (S90/S10)

43.4 17.9 17.9 42.5 18.0 19.6 4s.4 17.9 21.3 46.9 18.7 24.7 9.0 25.3 33.7 5.6 9.2 8.6 25.3 34.5 5.8 10.0 10.9 27.4 34.2 6.0 10.7 8.3 24.4 34.2 5.7 9.4

230

J. Seixas et al.Law

75/2013 hasfour

main aims:

decentralisation, strengtheningof

muni-cipal power, backingof voluntary

associationsof

municipalities,

and promotion ofterritorial

cohesion and competitiveness. TheLaw

envisages the delegationof

competences

from

the national level

to

the local

andthe inter-municipal

one.However, metropolitan boards

(Lisbon

and Porto, institutedin

2003) andmuni-cipal

associations(instituted

in

2008) have

beenkept

as coordination

bodieswithout

actual

competences,further

resources,or

elected boards (Crespo

&

Cabral,2010). In fact, discourses about 'decentralisation' are not resultingin

anyevident measures.

Along with the national-local

confrontation about political-administrative

reforms described above, the application

of

innovative

govemance instruments can also reveal complex patternsof

institutional

and local responses to thechal-lenges

within

and beyond the crisis, aswell

aseffofts

tobuild

accountabilityfor

local expenditurein

timesof

constraint. Several instruments have beendevelop-ing,

such as Agenda 21'a (implementedin five municipalities of

theLMA),

par-ticipatory budgeting

(the most

diffused

tool,

used

by

nine

of

the

18municipalities),

and a numberof

consultative anddigital tools

for

citizen-gov-effiment communication (Lisbon, Cascais). However,

it

is not always in the moststable

fashion;

for

example,

the

recent

Portuguesehistory

of

participatory budgetingis

characterisedby

much experimentationwith

some inherentinstab-ility

(Alves

&

Allegretti,

2012). Somemunicipalities

hadto

cut budgets (Lisbon and Cascais), others have usedparticipatory

budgetingwithout

any

regularity (Odivelas, Oeiras and Sesimbra), and,in

fuither

cases, what was calledparlici-patory

budgeting hasactually

only

beenthe use

of

simple

consultative tools (Alcochete and Palmela).Lisbon-Cìty

:

betweeninnovøtion

snd contrødíctory trendsDifferent local

governmentsin

the

LMA,

in

termsof

their

partisan andideo-logical

components, have beentrying

to

develop robustpolicies

and newprac-tices

to

respondto

the crisis

and

its main

urban problems. Amongst

these,Lisbon-City

is an especially interesting case. Since 2007, efforts to be innovativehave been made possible thanks to a stable

political

background, supportedby

acentre-left govemment.

The efforts towards

sustainedreform and

political

empowerment have been shaped around the

principles

of

innovation

andparli-cipation.

In

addition to

the above-mentioned administrativereform

andpartici-patory tools, two

policy

areas can be analysed: urban regeneration and strategiesfor

fostering economic recovery.First,

a new

emphasishas

beenput on building

rehabilitation and

urban regeneration, asthis is

seen asa

cornerstoneof

planning

policy for

investor-friendly

action, andfiscal

andedification

incentives.As

aresult

of

30 yearsof

demographic contraction,

a

significant

volume

of

vacant

dwellings

(around50,000)

is

availablein

Lisbon-City,

pafiicularly in its

historic

centre.Political

discourse has, since the 1990s, emphasised the needfor public policy

thatwould

encourage

the rehabilitation

of

buildings,

but few

resultswere

achieveduntil

Changing dynamics

of

political spaces

231 recent years.With

the impact of the crisis on the construction sector, therehabil-itation

of

derelictbuildings

has become a more tangibleactivity,

bothin

public andprivate

strategies. Justrecently, the

central government introduced a new regulation(Law

5312014) to reduce technical requirements,with

the aim ofredu-cing rehabilitation

costsby

over

30 per cent(Ministério

doAmbiente,

Ordena-mento

do

Territorio

e

Energia, 2014).

ln

addition

to a

stimulus

for

therequalification

of

private dwellings, the Lisbon

municipality

has elaborated astrategic plan

for

the requalification and managementof

council housing (around30,000

flats)

with

thefinal

aim

of

transfening

ownershipof

the

stock over thenext

few

decades (UrbanGuru,20ll).

However,

political

critiques

have high-lighted therisk

thatonly

real estate investorswill

be able to respond to the chal-lenge becauseof

the credit crunch that

is

affecting

middle-classfamilies

andtheir

housing

strategies.In

fact,

regenerationpolicies

in

central districts

havealready boosted

gentrification

trends (Mendes, 2013),which

may keep growing in the near future as a consequence oftourism-friendly

policies.On the other hand, attention

paid to

grass-rootsplanning

in

Lisbon-City

wascomplemented

by

a

programme about

priority

intervention

neighbourhoods,BIPIZIP or 'Bairros

e Zotas de IntervençãoPrioritaria'.'5

TheBIP/ZIP

promotesmicro-actions

for

urban regeneration fundedby

an annualcompetitive

processand implemented

by

coalitions

of

local

grass-roots participants.Although

thescheme

is

an innovative

one,the

scarcity

of

the

already allocated funds

(€1million

ayeat,

around 0.25 per centof

themunicipal

budget) cannotfully

influ-ence the regenerationofdeprived

areas.Also,

several strategiesto

foster

economicactivity

and employment

havebeen developed,

particularly

with

the adventof

the crisis.Urban

entrepreneur-ship

support schemes have been launched: business incubators, incentivesfor

new businesses, and support

ofretail

initiatives.

The strategyofdesigning

urbanpolicies

to

attractinternational tourism

flows

has also beenat the

coreof

theefforts

of

themunicipal

govemment.Globally, Lisbon-City

suffered the impactof

aglobal tourism

recessionin

thefirst

phaseof

the crisis

(a reductionof

8.9per cent

in

the

number

of

overnight

stays

for

the period

2007-2009),

but

emerged as an important tourist destination among Europe's cities

in

thefollow-ing

years (an increaseof

19.4 per centin

the numberof

overnight staysfor

theperiod 2009-2012)

(CâmaraMunicipal

deLisboa,

2014).The town councillor

for

planning has recently launched a proposalfor

a non-tax areafor

hotels in thedowntown area

of

thecity

and amajor

investment is programmedfor

upgradingLisbon

CruiseTerminal

so thatit

can accommodate larger numbersof arivals.

New

services and economicactivities,

aswell

as new multi-sectoral approachesto

city living

itself,

are popping up, notonly

in

thecity

centrebut

in

otherhis-toric

areas.Civic