w w w . j c o l . o r g . b r

Journal

of

Coloproctology

Original

Article

Assessment

of

subjective

well-being

and

quality

of

life

in

patients

with

intestinal

stoma

Geraldo

Magela

Salomé

a,∗,

Sergio

Aguinaldo

de

Almeida

b,

Bruno

Mendes

a,

Maiume

Roana

Ferreira

de

Carvalho

a,

Marcelo

Renato

Massahud

Junior

aaUniversidadedoValedoSapucaí(UNIVÁS),PousoAlegre,MG,Brazil

bHospitalMunicipalDr.ArthurRibeirodeSaboya,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received14February2015 Accepted3March2015 Availableonline2July2015

Keywords:

Stoma Ostomized Qualityoflife Colostomy Ileostomy

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:Toinvestigatethesubjectivewell-beingandqualityoflifeinpatientswith

intesti-nalstoma.

Method:ThisstudywasconductedatOstomizedPeople’sPoleofPousoAlegre.Datawere

collectedintheperiodbetweenDecember2012andMay2013,afterapprovalbytheEthics CommitteeoftheUniversidadedoValedoSapucaíunderopinionNo.23,277.The partici-pantswereselectedbyaconveniencenon-probabilitysampling.Thefollowinginstruments wereused:aquestionnaireondemographicsandstoma;aSubjectiveWell-beingScale;and aQualityOutcomeScale.

Results:RegardingtheFlanaganQualityofLifeScale,16–22pointswereobtained,indicating

thatthesepatientssufferedchangesintheirqualityoflife.Regardingthescaleofsubjective well-beinginthreedomains:positiveaffect–43(61.40%)individuals;negativeaffect–31 (44.30%)individuals;andlifesatisfaction–54(77.10%),allsubjectsobtainedascoreof3, characterizinganegativechangeinthesedomains.ThemeanFlanaganQualityofLifeScale scorewas26.16,andthemeansforthedomainsincludedintheSubjectiveWell-beingScale were:positiveaffect:2.51;negativeaffect:2.23andlifesatisfaction:2.77,indicatingthatthe intestinalstomauserswhoparticipatedinthestudyhadnegativefeelingsrelatedtotheir ownself-esteemandtothelossofqualityoflife.

Conclusion:Patientswithintestinalstomawhoparticipatedinthisstudyhadachangein

theirqualityoflifeandinsubjectivewell-being.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.All rightsreserved.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mails:geraldoreiki@hotmail.com,gsalome@infinitetrans.com(G.M.Salomé). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2015.03.002

Avaliac¸ão

do

Bem-estar

subjetivo

e

da

qualidade

de

vida

nos

pacientes

com

estoma

intestinal

Palavras-chave:

Estoma Ostomizado Qualidadedevida Colostomia Íleostomia

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo: Avaliarobem-estarsubjetivoequalidadedevida nospacientescomestoma

intestinal.

Método: EsteestudofoirealizadonoPolodosEstomizadosdePousoAlegre.Osdadosforam

coletadosnoperíodocompreendidoentredezembrode2012emaiode2013,apósaprovac¸ão peloComitêdeÉticaemPesquisadaUniversidadedoValedoSapucaísobparecern◦23.277. Aamostrafoiselecionadadeformanãoprobabilística,porconveniência.Foramutilizados sequentesinstrumentos:questionáriosobreosdadosdemográficosesobreoestoma;Escala deBem-estarsubjetivoeaEscaladeQualidadedeResultados.

Resultados: Comrelac¸ãoàEscaladeQualidadedeVidadeFlanagan,alcanc¸ou-seentre16

a22pontos,revelandoqueessespacientesapresentavamalterac¸ãonaqualidadedevida. Comrelac¸ãoàescaladebem-estarsubjetivonostrêsdomínios:afetopositivo–43(61,40%) indivíduos;afetonegativo–31(44,30%)indivíduosesatisfac¸ãocomavida54(77,10%),todos osindivíduosobtiverampontuac¸ão3,caracterizandoalterac¸ãonegativanessesdomínios. AmédiadaEscaladeQualidadedeVidadeFlanaganfoi26,16,easmédiasdosdomíniosda EscaladeBem-estarsubjetivoforam;Afetopositivo:2,51;Afetonegativo:2,23esatisfac¸ão comavida:2,77,configurandoqueessesindivíduoscomestomaintestinalqueparticiparam doestudoapresentaramsentimentosnegativosrelacionadosàprópriaautoestimaeàqueda naqualidadedevida.

Conclusão:Ospacientescomestomaintestinalqueparticiparamdesteestudoapresentaram

alterac¸ãonaqualidadedevidaenobem-estarsubjetivo.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda. Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Inthiscentury,theincreaseinlifeexpectancy,the globaliza-tionandtheeffectsofurbanizationmeanthattheBrazilian populationwasexposedtomultiplehealthproblems,among which cancer, trauma and chronic degenerative diseases standout.Duetotraumaorother conditions,forexample, cancerandurinarytractdiseases,someindividualsmayneed anemergencysurgeryinvolvingthemakingofsometypeof stoma.Insome cases,theremay beinorder technological resources,suchastheimplantationofprostheticandorthotic devices,tosavethepatient’slifeortoprovideabetterquality oflife.1–3

Ostomy,orstoma,isawordofGreekorigin.Theostomy may represent limitation with respect to the person’s life project,especiallyinthecaseofelderlypeople.Inthispost operatoryprocess ofadaptation, ostomized people start to givea new meaningto their condition, looking aftertheir self-careandtheirnewcareenvironment.Thus,the environ-mentischaracterizedbyalliancesanddynamicassociations, convergencesandestrangements,freedom,dependenceand interdependence,overcomingand acceptancemechanisms, limitsandpotentialities.4–6

When receiving an intestinal stoma, the patient begins tolose controlwithrespecttothe eliminationoffecesand gases,asaresultofstomaopening;this promotesastrong emotionalimpactforostomizedpeople,because thestoma causesbodyscheme,self-imageandself-esteemchanges,also

determining other disorders associated withthese factors. Such changes cause various disorders in their lives, with whichthesepeople mustliveandthat impairtheirquality oflifeandsubjectivewell-being.7,8

Fromthemomentwhenthedoctortelltoapatientthat he willbe submitted to asurgery foran intestinal stoma, this patient starts to suffer in advance, showing anxiety, dissatisfaction withlife, and embarrassment.Furthermore, theseindividualsfeel unhappywhenfacedwiththe neces-sarychangesintheirhabitsand,consequently,thesignificant interferencein theirquality oflife. Oftenthe confirmation ofastomaisaneventthatalsoaffectsfamilymembersand theirsocialrelations,andagreatemotionalandpsychological impactmayaffecteveryoneinvolved.9,10

Inadditiontotheproblemsfacedbythosewhoare under-goingsurgery(reportedabove),ostomizedpeopleareexposed toaseriesofsocialconstraints,suchasthepossibilityof out-gassingandexcrementleakageduetothelackofvoluntary control,andalsobyflawsinthesafetyandqualityofthe col-lectionbag.Thus,thesepeopleareafraidofpublicexposure. Typically, suchproblems canbe understood from physical, psychological,socialandspiritualdimensions.11

Theassessmentofsubjectivewell-beingofostomized peo-pleshouldbeseenasagreatergoodtobemaintainedand/or restored,sothatthesepeoplecanlivehappilyandinharmony intheirlifecontext.Therefore,medicine,nursingandother alliedsciences,throughtheprofessionalswhomakeupthe supportstaff,shouldsparenoeffortsothatabetterquality oflifeforthesepeoplewillbetheoutcomeoftheassistance offeredthroughoutallstagesoftreatment,frompreoperative phasethroughthepostoperativeperiod,andintheguidelines forhospitaldischargeandhowtodealwiththisnewreality. Thus,thisstudyaimedtoevaluatethesubjectivewell-being andqualityoflifeofpatientswithintestinalstoma.

Methods

Thisisaclinical,primary,descriptive,analytical,and prospec-tivestudy.

This study was conducted at the Center of Ostomized People, city of Pouso Alegre. Data were collected between December 2012andMay 2013, afterapprovalbythe Ethics Committeeofthe Universidade doVale doSapucaí, under opinion No. 23,277. The participants were selected by a convenience non-probability sampling.Data collectionwas conductedbytheauthorsthemselves,afterthesigningofa freeandinformedconsentformbyallsubjects.Patientsaged less than 18 years withanintestinal stomawere included in this study. On the other hand, patients with demen-tia syndromes and other conditions that prevented them fromunderstandingandrespondingtoquestionnaireswere excluded.

Threedatacollectioninstrumentsforthisstudywereused. First, aquestionnaire ondemographics and on stomawas applied;as asecond instrument,the SubjectiveWell-being Scalewasused;andthethirdonewastheFlanaganQuality ofLifeScale.

TheSubjective Well-beingScaleisdividedinto two sub-scales.Thefirst subscalecomprises componentsrelated to affectiveandnon-affective emotions.Itiscomposedofthe items1–47;21itemsarerelatedtopositiveemotionsand26 items are related to negative emotions. For each item the respondentcanassign avaluefrom 1(notatall), 2(abit), 3(moderately),4(enough)to5(extremely).Thesecond sub-scaleconsistsofitems48–62,describingjudgmentsrelatedto theevaluationofsatisfactionordissatisfactionwithlife;these itemsmustbeansweredonascalewhere1means“completely disagree”;2,“disagree”;3,“donotknow”;4,“agree”,and5, “fullyagree.”Thetotalscoreofeachsubscaleisobtainedby addingtheanswersofeachitemdividedbythetotalnumber ofitemsinthesubscale.Thenumber3representsthemedian point.WiththeuseoftheSubjectiveWell-beingScale,three resultsareobtained,andareindependentlyassessed:positive affects,negativeaffectsandlifesatisfaction.Thus,highscores ofthefirstsubscale,representedbyscores>3,indicatepositive affects;andscores<3,negativeaffects.Ontheotherhand,in thesecondsubscale,scores>2representsatisfactionwithlife. Allsubscaleshavegoodinternalconsistency(positiveaffects: 0.95;negativeaffects:0.95;satisfactionwithlife:0.9).13

TheFlanagan Qualityof Life Scale14 conceptualizes the

quality of life based on five dimensions: physical and

materialwell-being;relationshipwithothers;social, commu-nityandcivicactivities;personaldevelopmentandfulfillment; andrecreation.Thesedimensionsaremeasuredby15items, wheretherespondenthas7responseoptions,rangingfrom “very dissatisfied”(score1)to“verysatisfied”(score7).The maximum score achieved in assessing the quality of life proposed by Flanagan is 105 points, with 15 points being the minimum score, reflecting a low quality of life. It is worth noting that the scale is self-administered; however, someolderpeopleinvolvedinthisstudyreceivedassistance from researchersintheiranswerstothis instrument,given that thesepeoplehad physicallimitationsashand tremor, impairedvisualandhearingacuity,andloweducationallevel. TheFlanaganQualityofLifeScalewasdevelopedforuse intheUSAandhasnotbeenvalidatedfortheBrazilian cul-ture;however,Hashimotoetal.translatedtheinstrumentinto Portugueseandapplieditonostomizedpatients.

Thescalewasappliedtoarelativelylargeand heteroge-neousrandomsample;theseauthorsfoundhighreliabilityfor thisinstrument.Thentheyusedthescaleinastudyinvolving elderlypeople,14whenagoodlevelofreliabilitywasfound–a

factorthatcontributedtothedecisiontousethisinstrument inthisstudy.

Inthestatisticalanalysis,thefollowingtestswereused:the chi-squaredtestforsocio-demographicvariablesandforthe “relatedtoostomy”variable,todetermineifthedistribution wasproportional,thatis,ifthesamenumberofsubjectswas allocated toeach variablecategory.Kruskal–Wallis testand Spearmancorrelationwerealsousedonthescalevariablesof SubjectiveWell-beingandonFlanaganQualityofLifeScale. Forallstatisticaltests,significancelevelsof5%(p<0.05)were considered.

Results

Mostparticipantswere agedabove60 yearsold,male gen-der,retired,earned1–3minimumwagesandattendedsupport groups.Twenty-one(30%)ofthe respondentswere illiterate and19(25.10%)couldreadandwrite.Thirty-eight(54.30%)of respondentswereinvolvedwithsupport/membershipgroups. Mostoften,thecausethatledpatientstoacquireostomy wasaneoplasm;andpermanentcolostomywasthetypeof ostomy used. Mostofthe subjects were nottold thatthey wouldreceiveastoma.Furthermore,nostomademarcation orirrigationwastaken.Regarding thetypeofcomplication, 34(48.60%)haddermatitis;14(20%)retractionand13(18.60%) prolapse. With respect to the diameter of the stoma, 34 (48.60%)measured20–40mmand23(32.90%),40–60mm.

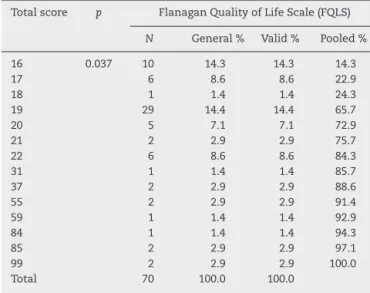

According toTable1,it wasobservedthat theFlanagan QualityofLifeScale(FQLS)reached16–22points;thisscore revealsthatthesepatientsshowedqualityoflifechanges.

Table2shows that,withrespecttothe Subjective Well-beingScale,thefollowingdomains:positiveaffect–43(61.40%) subjects; negative affect – 31 (44.30%) subjects; and satis-faction with life – 54 (77.10%) subjects attained a score 3, indicatingthattheseindividualsshowedanegativechange intheseareas.

Table1–ResultsobtainedwiththeFlanaganQualityof LifeScaletotalscoreinpatientswithintestinalstoma.

Totalscore p FlanaganQualityofLifeScale(FQLS)

N General% Valid% Pooled%

16 0.037 10 14.3 14.3 14.3

17 6 8.6 8.6 22.9

18 1 1.4 1.4 24.3

19 29 14.4 14.4 65.7

20 5 7.1 7.1 72.9

21 2 2.9 2.9 75.7

22 6 8.6 8.6 84.3

31 1 1.4 1.4 85.7

37 2 2.9 2.9 88.6

55 2 2.9 2.9 91.4

59 1 1.4 1.4 92.9

84 1 1.4 1.4 94.3

85 2 2.9 2.9 97.1

99 2 2.9 2.9 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Kruskal–WallisandSpearmantests,p≤0.05.

Table2–Resultsobtainedinscorefordomainsof Well-beingSubjectiveScaleinintestinalstomasubjects.

Domain p SubjectiveWell-beingScale

N General% Valid% Pooled%

Positiveaffect

1 0.003 7 10.0 10.0 10.0

2 20 28.6 28.6 38.6

3 43 61.4 61.4 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Negativeaffect

1 0.057 15 21.4 21.4 21.4

2 24 34.3 34.3 55.7

3 31 44.3 44.3 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Lifesatisfaction

1 0.002 9 182.9 12.9 12.9

2 7 10.0 10.0 22.9

3 54 77.1 77.1 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Kruskal–WallisandSpearmantests,p≤0.05.

Table3–ResultsobtainedinmeanscoreofSubjective Well-beingScaleandofFlanaganQualityofLifeScalein intestinalstomasubjects.

Descriptivelevel Positive

affect

Negative affect

Life satisfaction

SubjectiveWell-beingScale

Mean 2.51 2.23 2.77

Median 3.00 2.00 3.00

Standarddeviation 0.676 0.783 1.103

FlanaganQualityofLifeScale

Mean 26.16

Median 19.00

Standarddeviation 19.897

Kruskal–WallisandSpearmantests,p≤0.05.

ofSubjectiveWell-beingScalewere:positiveaffect:2.51; neg-ativeaffect:2.23;andlifesatisfaction:2.77,indicatingthatour ostomizedsubjectshadnegativefeelingsrelatedtotheirown self-esteemandlossofqualityoflife.

Discussion

Withregardtosociodemographiccharacteristics,itwasfound that52 subjects(74.30%)were maleandmostwere elderly, over60years,characterizinganelderlypopulation.These find-ingsagreewithanumberofstudieswhosesubjectsweremale andagedover60.15–19

As formarital status, the study showed that there was a prevalence among married, 34 (48.60%), followed by 22 (31.40%) widow(ers), and 14 (20.00%) separated. Thisresult showstheimportanceoffamilyinvolvement,especiallythe partner,ontherecoveryofanostomizedpatient.

Intermsofage,themostaffectedgroupwasthe popula-tionover60years.Aboutthisfinding,itisimportanttopoint out that the elderly have unique biological characteristics andaremorevulnerabletochronic-degenerativediseases,for instance,cancer.20Inastudy,theauthorsstatedthatthe

inci-denceofstomacomplicationsismultifactorial,involvingfrom themakingofthestoma,itslocation,andobesity,with influ-enceofage.Thus,whenthesefactorsareassociatedwiththe physiologicalchangesoftheagingprocess,agreater vulnera-bilityoftheelderlyintheincidenceofstomacomplicationsis seen.21

Astoeducationlevel,itwasnotedthatmostpatients(47; 67.14%)wereilliterate. Thisresultrevealsaworrisome pro-file inregard tocitizenshipand respectforrights, because it is knownthat the lower the educationallevel, the more unfavorableisthelinguisticcapitalofthepatienttoquestion professionalsabouthis/herhealthproblems,thecarebeing providedandhis/herinherentrights.Itisworthtopointout thatthissituationdoesnotaffecttheperformanceofthe pro-fessionals inface of these people, because the interaction amonguser,serviceandhealthprofessionalshasovercome the difficultiesimposed bythis variable.21 Inreviewing the

respondents’ profession,it wasobservedthat “retiree”was theprofessionalstatusthatstoodout(50;71.40%),followed bythoseworkingatthetime(14;20.00%).Thesefindingsare inlinewithdatafromotherstudies.18,22–26Oneofthesocial

consequences ofostomized patients isthe role and social status changes in face ofhis/her family and society. After surgery,mostoftentheostomizedperson(whichuntilthen wasworking)becomesaretiree;withthat,he/shestopsbeing thefamilyprovider,thusbecomingdependentinrelationto his/hercare.18

Inthisstudy,theinvestigatorsreportedthatthe exterior-ized bowelsegments were colostomiesandwithrespectto bowel loop externalization time, surgery was definitive. In 52patients(74.30%),thecausesformakingthestomawere attributedtocancer;andmoststomatameasured20–40mm; thesedatacoincidewiththefindingsofotherstudies.26–29

preventthereconstructionofboweltransit,consideringthat diseasesofthegastrointestinaltractleadtoaradicalsurgery in many of these cases, resulting in a temporary or even definitive ostomy.30 With regard to the typeof system, 48

(68.60%)patientsusedtwo-piecedevices,whilein44(62.90%) anirrigationwasnotperformed.

Itisworthnotingthatwhenpatientswereaskedaboutthe completionofdemarcationinthepreoperativeperiod,mostof thepatientstoldthattherewasnodemarcation.This proce-dureisextremelyimportant,giventhataconvenientlocation facilitatesself-careandtherehabilitationprocess.Therefore, whenperformingthephysicalexamination,thecarermustbe awareofthestomapositioningsite,andthedemarcationof thestomamustbemadebeforesurgery,inordertopreventor minimizepossiblestoma-andperistomalareacomplications. Onthatoccasion,itisalsoimportantthatthenurseeducate thepatientsandtheirfamiliesaboutself-care.29–31

Withregardtocomplications,36(48.60%)respondentshad dermatitis;14(20.00%)retractionand13(18.60%)prolapse.In addition,48(68.60%)patientswerenottoldthattheywould haveanintestinalstoma.Oneshouldalsoconsiderthatsome complicationsincreasewithageandwithfailuretoperform stomademarcation.Sincethedemarcationhasnotbeendone inthispopulation,whichispredominantlymadeupofolder people,itcanbesaidthatthisfactrepresentsoneofthefactors thatmayhavecontributedtotheoccurrenceofcomplications suchasthosecited,thusconfirmingthefindingsinother stud-ies.

Usually,dermatitidesareinjuriesresultingfromimproper useofcollectors,morepreciselybyanexcessivecuttingofthe holeoftheprotectivebarrierrelativetothestoma,leavingthe skinexposedtotheactionofeffluent; orbyaninadequate indicationoftheequipmentforthetypeofstomaused. Col-lectorsandadjuvantequipmentavailableonthemarketmust bepresentedtothesmallestdetailtoostomy patients.The equipmentusedinsomeservicesisrecommendedin accor-dancetotheresultsoftheassessmentcarriedoutatthetime; butastimegoesby,areplacementmaybeneeded.Hencethe needforcontinuousassessment.31,32

Ontheotherhand,thepresenceofprolapseanddermatitis atthesametimereferstotheonsetofthesecondcomplication asaresultfromthefirstone;thatis,dependingonthedegree ofexternalizationoftheintestinalloop,thismaybe expos-ingtheskintoeffluentandexcessivesecretionofmucusand, therefore,decreasesthelowadhesivenessofthebag,which facilitatesexcrementleakage.28,32,33

Therefore,inview ofthemany aspectsthat involvethe rehabilitationofostomizedpeople,nursingcareofthestoma shouldbeginatdiagnosis,ontheoccasionofsurgery indica-tionandonthedayofdemarcationofthestoma.Thus,the aimistominimizecomplicationsandsufferingsin achiev-ingself-care,andfurthermore,toobtainabetteradaptation. Manypatientsendupgettingdissatisfiedwithlifeandwith thedifficultiestodeveloptheirdailyactivities,feelingafraid toperformself-care.Suchfeelingshavetheeffectofmodifying thequalityoflife.33,34

Whentheostomizedindividualstartstorealizethatgasor odoriscomingoutthroughthestoma,andwhensome com-plicationsarise(suchasdermatitis,whichcancausepain),a needformorethanonechangeofthedevicesupervenes.Such

aneventmakesthepatientsufferbiopsychosocialchanges. Mostpatientsfeelshame,andintheendjustdonotwant,or feelunable,togoonworking,studying,andtakingpartindaily activitiesand leisure.Thisgivesrise toachangeinhis/her qualityoflifeandwell-being–andeventodissatisfactionwith theirlife.

All thesephysicalchangescanalsocausethepatientto feelthathis/herlifeworsenedandthatisdifficulttolivewith otherpeople–andthismayalsoresultinchangesinfamily relationship.

Inthepresentstudy,themeanoftheSubjectiveWell-being Scaledomainswaslow(positiveaffect:2.51,negativeaffect: 2.23,satisfactionwithlife:2.77)andthemeanofqualityoflife was26.16, characterizingnegativechangesofthese dimen-sionsofSubjectiveWell-beingScaleandadecreaseinquality oflifewithFlanaganQualityofLifeScale.

Satisfaction is a complex and difficult-to-measure phe-nomenon,becauseitisastateofsubjectivewell-being.Itis thegreatestexpressionoflifeexperiencewithrespecttothe various livingconditions ofaperson.Satisfaction withlife isa cognitivejudgmentofafew specificareas inthe indi-vidual’slife,suchashealth,activitiesofeverydaylife,work, housing,socialrelationships,familyrelationshipsandleisure and autonomy; that is, aprocess ofjudgment andgeneral assessmentoflifeitself,accordingtoourowndiscretion.The judgmentofsatisfactiondependsonacomparisonbetween thelivingcircumstancesoftheindividualandonastandard establishedbyhimself/herself.Satisfactionreflects, inpart, theindividualsubjectivewell-being,thatis,thewayandthe reasonsthatleadpeopletolivetheirlifeexperiencesina pos-itiveway.35,36

“Subjective well-being”seeks to understand the assess-ment that individuals make about their own lives on the followingissues:happiness,satisfaction,moodandpositive affect;someauthorsconsiderthisasasubjectiveassessment ofqualityoflife.36

Inastudydevelopedwithostomizedpatients,theauthors concludedthattheperceptionofthesesubjectswithregard tothecollectionbagiscloselyintertwinedwiththepresence ofnegative feelings:fear, insecurity,mutilation and suffer-ing,aswellasofself-destructivefeelings.Themostcommon changes experiencedbyourintervieweesare relatedtothe maintenanceoftheirsocialnetwork(workandleisure)andto theirsexuality,becausetheyfeelinsecureandfearrejection. Itisnoteworthythat theseexistentialconflictsare genera-torsofchangesofpsychological,emotionalandsocialorder. However,thisstudy allowsustobecomeawareofhowthe process ofadaptingthis experiencewiththecollection bag happens.Thus,it isexpectedthatthe resultsofthis study could possibly represent a starting point for the develop-mentofanursingcarestrategycenteredontheclient.Given thisreality,weemphasizeself-care. Thisproposalhasbeen describedasatherapeuticalternativethatallowsthepatient toactivelyparticipateinhis/hertreatment,bystimulatingthe responsibilityforcontinuityofcareafterdischarge,whichwill contribute tothe rehabilitation process and toovercoming his/herdifficulties.37

authorshasshownthatlifesatisfactionishigherinwomen, peoplereceivingpension,peoplewhoaresatisfiedwiththe supportreceived,peoplewhosupportothers,andpeople fac-ingdirectlytheirproblemswithapositivereappraisal.Onthe other hand,positive affects also increase withsatisfaction fromthesupportreceivedandwithadirectand reapprais-ingcoping attitude,aswell aswithadecrease inavoidant coping.36

Inastudywhereintestinalstomapatientshadameanof 10.81intheRosenbergSelf-EsteemScale/UNIFESP-EPM,with regardtotheBodyInvestmentScale,themeanoftotalscore was38.79;the meanof“bodyimage”and“personal touch” domainswas7.74and21.31,respectively.Thesedatamean thatostomizedpatientshadlowself-esteemandself-image changesinallstomacharacteristicsandinsociodemographic data.Inotherwords:afteracquiringthestoma,these individ-ualshadnegativefeelingsabouttheirownbodies.34

Negativeaffectsdecreasewhensocialsupportisprovided, althoughtheyincreasewithavoidantcoping.Thisisanother reasonfornottoconsidertheindividualwithacuteorchronic woundsjustasapassiverecipientofhelpandunderstanding. The scope of their actions also contributes to their well-beingandsatisfaction.Afterall,thelesserpredictivepower ofsocialsupportandcopingstylesontheirpositiveand neg-ativeaffectsindicatesthatothervariablesareinvolvedinthe dimensionsofsubjectivewell-being ofinjured people, par-ticularlyinthoseissuesthataredirectlyconnectedtotheir functionalautonomy.38–41

Inthisstudy,itwasshowntheimportanceoftheuse,by thecarer(nurse,doctor,psychologist)involvedinthecareof ostomypatients,ofaclear,accessibleandobjectivelanguage, forbetterunderstandingbytheclient,consideringthatagood nursingcareshouldbegin preoperatively,withassessment, guidanceandcareinthenecessarypreparationoftheclient facingthesurgery.Ontheotherhand,thispreparationshould be continued throughout the period in which the patient remains withthe ostomy – which can bepermanent. The ostomizedpatientshouldbewellguided,taughtandtrained on the skills necessaryto take his/herself-care, especially regardingstomahandling,suchascleaningthe peristomal skin,specificationsandavailabilityofspecificequipmentand aidsforeffluentcollection.41,42

Patients with intestinal stoma in this study showed changesintheirqualityoflifeandsubjectivewell-being.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. TosatoSR,ZimmermannMH.Conhecimentodoindivíduo ostomizadoemrelac¸ãoaoautocuidado.RevConexaoUEPG. 2006;1(1):33–7.

2. CostaVF,AlvesSG,EufrásioC,SaloméGM,FerreiraLM. Assessingthebodyimageandsubjectivewellbeingof ostomistslivinginBrazil.GastrointestNurs.2014;12(5):37–47. 3. SaloméGM,AlmeidaSA.Associationofsociodemographic

andclinicalfactorswiththeself-imageandself-esteemof

individualswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol. 2014;34(3):159–66.

4.OliveiraG,MaritanCVC,MantovanelliC,RamalheiroGR, GavilhiaTCA,PaulaAAD.Impactodaestomia:sentimentose habilidadesdesenvolvidosfrenteànovacondic¸ãodevida. RevEstima.2010;8(1):18–24.

5.BarrosEJL,SantosSSC,ErdmannAL.Redesocialdeapoioàs pessoasidosasestomizadasàluzdacomplexidade.ActaPaul Enferm.2008;21(4):595–601.

6.LessmannJC,RibeiroJA,deSousaFGM,MarcelinoG,do NascimentoKC,ErdmannAL.Anursingacademicperspective concerningthecareenvironmentwithinthecomplexity paradigm–adescriptivestudy.OnlineBrazJNurs.2006; 5(1).

7.CesarettiIUR,SantosVLCG,FilippinMJ,LimaSSL.Ocuidarde enfermagemnatrajetóriadoostomizado:pré&trans& pós-operatório.In:SantosVLCG,CesarettiIUR,editors. Assistênciadeenfermagememestomaterapia:cuidandodo ostomizado.SãoPaulo:Atheneu;2000.p.113–31.

8.deGouveiaSantosVL,ChavesEC,KimuraM.Qualityoflife andcopingofpersonswithtemporaryandpermanent stomas.JWoundOstomyContinenceNurs.2006;33(5):503–9. 9.PetucoVM,MartinsCL.Quasecomoantes.Aressignificac¸ão

daidentidadedapessoaestomizadacomcâncer.Mundo saúdeSãoPaulo[online].2006;30(1):52–64.

10.SantosLMP,Gonc¸alvesLLC.Crianc¸ascomcâncer:desvelando osignificadodoadoecimentoatribuídoporsuasmães.Rev EnfermUERJ.2008;16:224–9.

11.MatheusMQ,LeiteSMC,DázioEMR.Compartilhandoo cuidadodapessoaostomizada.In:Anaisdo2◦Congresso BrasileirodeExtensãoUniversitária[CD-ROM].2004.Available from:http://www.ufmg.br/congrext/Saude/Saude57.pdf [accessed28.02.08].

12.GemelliLMG,ZagoMMF.Ainterpretac¸ãodocuidadocomo ostomizadonavisãodoenfermeiro:umestudodecaso.Rev LatinoamEnferm.2002;10(1):34–40.

13.AlbuquerqueAS,TróccoliBT.Desenvolvimentodeumaescala debem-estarsubjetivo.PsicTeorePesq.2004;20(2):153–64. 14.FlanganJC.Measurementofqualityoflife:currenteofart

state.ArchPhysMedRehabil.1982;23:56–9.

15.ZimnickiKM.Preoperativestomasitemarkinginthegeneral surgerypopulation.JWoundOstomyContinenceNurs. 2013;40(5):501–5.

16.NakagawaH.Stomalocationrequiresspecialconsiderationin selectedpatients.JWoundOstomyContinenceNurs. 2013;40(6):565–6.

17.NakagawaH,MisaoH.Effectofstomalocationonthe incidenceofsurgicalsiteinfectionsincolorectalsurgery patients.JOstomyContinenceNurs.2013;40(3):287–96. 18.SallesVJA,BeckerCPP,FariaGMR.Theinfluenceoftimeon

thequalityoflifeofpatientswithintestinalstoma.J Coloproctol.2014;34(2):73–5.

19.MelottiLF,BuenoIM,SilveiraGV,SilvaMEN,FedosseE. Characterizationofpatientswithostomytreatedatapublic municipalandregionalreferencecenter.JColoproctol. 2013;33(2):70–4.

20.ZilbersteinB,Gama-RodriguesJ,Habr-GamaA,SaadWA, MachadoMCC,CecconelloI,etal.Cuidadosprée

pós-operatóriosemcirurgiadigestivaecoloproctológica.São Paulo:Roca;2001.p.104.

21.MinistériodaSaúde(Brasil),SecretariadeAtenc¸ãoàSaúde. Portarian◦400,de16denovembrode2009.Brasília,DF:

MinistériodaSaúde;2009.

23.SantosCHM,BezerraMM,BezerraFMM,ParaguassuBR.Perfil doPacienteOstomizadoeComplicac¸õesRelacionadasao Estoma.RevBrasColoproctol.2007;27(1):16–9.

24.AguiarESS,SantosAAR,SoaresMJGO,AncelmoMNS,Santos SR.ComplicacionesdelEstomaydelaPielPeriestomalcom PacientescomEstomasIntestinales.RevEstima.

2011;9(2):22–30.

25.CesarettiIU,SantosVL,ViannaLA.Qualityoflifeofthe colostomizedpersonwithorwithoutuseofmethodsof bowelcontrol.RevBrasEnferm.2010;63(1):16–21.

26.OliveiraCAGS,RodriguesJC,SilvaKN.Identificac¸ãodonível deconhecimentodepacientescomcolostomiasparaa prevenc¸ãodepossíveiscomplicac¸ões.RevEstima. 2007;5(4):26–30.

27.MoraesJT,VictorDR,AbdoJR,SantosMC,PerdigãoMM. Characterizationofenterostomalpeopleassistedbythe MunicipalGeneralOfficeofHealthofDivinópolis-MG.Rev Estima.2009;7(3):31–7.

28.ChilidaMSP,SantosAH,CalvoAMB,BelloBEC,AlvesDA, GuerinoMI.Complicac¸õesmaisfrequentesempacientes atendidosemumpolodeatendimentoaopacientecom estomanointeriordoEstadodeSãoPaulo.RevEstima. 2007;5(4):31–6.

29.SonobeHM,BarichelloE,ZagoMMF.Avisãodo

colostomizadosobreousodabolsadecolostomia.RevBras Cancerol.2002;48(3):341–8.

30.SantosVLCG,CessarettiIUR.AssistênciaemEstomaterapia: cuidandodoostomizado.SãoPaulo:Atheneu;2000.

31.SaloméGM,SantosLF,CabeceiraHS,PanzaAMM,PaulaMAB. Knowledgeofundergraduatenursingcourseteachersonthe preventionandcareofperistomalskin.JColoproctol. 2014;34(4):224–30.

32.SilvaAC,SilvaGNS,CunhaRR.Caracterizac¸ãodePessoas EstomizadasatendidasemConsultadeEnfermagemdo Servic¸odeEstomaterapiadoMunicípiodeBelém-PA.Rev Estima.2012;10(1):12–9.

33.Habr-GamaA,AraújoSEA.EstomasIntestinais:aspectos conceituaisetécnicos.In:SantosVLCG,CesarettiIUR,editors.

AssistênciaemEstomaterapia:cuidandodoostomizado.São Paulo:Atheneu;2000.p.39–40.

34.SaloméGM,AlmeidaSA,SilveiraMM.Qualityoflifeand self-esteemofpatientswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol. 2014;34:231–9.

35.JoiaLC,RuizT,DonalisioMR.Lifesatisfactionamongelderly populationinthecityofBotucatu,SouthernBrazil.RevSaude Publica.2007;41(1):131–8.

36.GuedeaMTD,AlbuquerqueFJB,TróccolBT,NoriegaJAV, SeabraMAlB,GuedeaRLD.Relac¸ãodobem-estarsubjetivo, estratégiasdeenfrentamentoeapoiosocialemidosos.Psicol ReflexCrit.2006;19(2):301–8.

37.BatistaMdoR,RochaFC,daSilvaDM,JúniorFJ.Self-imageof clientswithcolostomyrelatedtothecollectingbag.RevBras Enferm.2011;64(6):1043–7.

38.SantoPFE,deAlmeidaAS,PereiraMTJ,SaloméGM. Evaluationofdepressionlevelsinindividualswithchronic wounds.RevBrasCirPlast.2013;28(4):665–71.

39.BalsanelliACS,GrossiSAA,HerthK.Assessmentofhopein patientswithchronicillnessandtheirfamilyorcaregivers. ActaPaulEnferm.2011;24(3):354–8.

40.Lourenc¸oL,BlanesL,SaloméGM,FerreiraLM.Qualityoflife andself-esteeminpatientswithparaplegiaandpressure ulcers:acontrolledcross-sectionalstudy.JWoundCare. 2014;23(6):331–7.

41.LuzMHBA,AndradeDS,AmaralHO,BezerraSMG,Benício CDAV,LealACA.Caracterizac¸ãodospacientessubmetidosa estomasintestinaisemumhospitalpúblicodeTeresina-PI. TextoContextoEnferm.2009;18(1):140–6.