FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS MESTRADO EXECUTIVO EM GESTÃO EMPRESARIAL

AN EVALUATION OF THE IMPACT OF NETWORKING

EVENTS FOR SUCCESSFUL STARTUPS IN SÃO PAULO AND

NEW YORK

D

ISSERTAÇÃO APRESENTADA ÀE

SCOLAB

RASILEIRA DEA

DMINISTRAÇÃOPÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS PARA OBTENÇÃO DO GRAU DE MESTRE

FABIO FLAKSBERG Rio De Janeiro – 2016

FABIO FLAKSBERG

AN EVALUATION OF THE IMPACT OF

NETWORKING EVENTS FOR

SUCCESSFUL STARTUPS IN SÃO

PAULO AND NEW YORK.

Master's thesis presented to Corporate International Master's program, Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública, Fundação Getulio Vargas, as a requirement for obtaining the title of Master in Business Management.

Advisor: Carmem Pires Migueles

Rio de Janeiro 2016

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV

Flaksberg, Fabio

An evaluation of the impact of networking events for successful startups in São Paulo and New York / Fabio Flaksberg. – 2016.

82 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas, Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa.

Orientadora: Carmen Pires Migueles. Inclui bibliografia.

1.Empreendedorismo. 2. Planejamento empresarial. 3. Planejamento estratégico. I. Migueles, Carmen Pires. II. Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas. Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa. III. Título.

I dedicate this work to my father and my mother, who tirelessly supported and

encouraged my education from my very first words during my childhood through to my Master’s program. And to my wife for the inspiration, patience and love during the long path of

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to thank all Corporate International Masters professors who led my colleagues and I through a lifetime experience by sharing with us their knowledge, insights, cultural perspectives and inestimable time during this outstanding program.

I would like to give special thanks to my supervisor Carmem Pires Migueles, who patiently supported me during all times and contributed by offering several sharp and knowledgeable advices. Without your guidance, this work wouldn’t be possible. Moreover, I want to thank all the entrepreneurs and CEOs from startups both in São Paulo and New York who gave me the opportunity to conduct the survey that constitutes the core of this work. Furthermore, I’m very grateful to all the preeminent professionals who generously offered me their time by participating in the valuable interviews that enrich this study.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

INTRODUCTION... 13

1.1 São Paulo and New York Overview ...14

1.2 Contextualization and Relevance of the Problem ...16

1.3 Research Objectives ...18

1.4 Structure of this Thesis...20

2

RESEARCH QUESTION AND OBJECTIVE... 20

2.1 General Objective ...20

2.2 Specific Objectives ...21

3

THEORETICAL REFERENCES ... 21

3.1 Network Data ...21

3.2 The Pillars for a Successful Startup Environment ...22

3.3 The Emic Approach...25

3.4 The Cultural Difference that Drives Productivity...25

3.5 Startup Definition...26

3.6 Networking ...27

3.7 Networking Event Definition...28

4

METHODOLOGY... 28

4.1 Research Approach ...28

4.2 Bifocal Analysis...30

4.3 Quantitative Research ...30

4.4 Delimitation of the Universe ...30

4.4.1 Sample: ...30 4.4.2 Economic Criteria:...31 4.4.3 Operational Criteria: ...32 4.5 Qualitative Research ...35 4.6 Interviews ...36 4.6.1 São Paulo...36 4.6.2 New York ...40

5

ANALYSIS OF THE RESEARCH RESULTS ... 44

5.1 São Paulo Survey ...44

5.1.1 Respondents overview ...44

5.1.2 Questionnaire outcome...45

5.2 New York Survey ...58

5.2.1 Respondents’ overview ...58

5.2.2 New York Survey Highlights...59

6

DISCUSSIONS and CONCLUSION... 64

6.1 Critics of Networking Events...65

7

LIMITATIONS, CONTRIBUTIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 67

7.1 Limitations...67 7.2 Contribution ...67 7.3 Future Research ...68

8

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 70

9

APPENDIX ... 74

LIST OF FIGURES

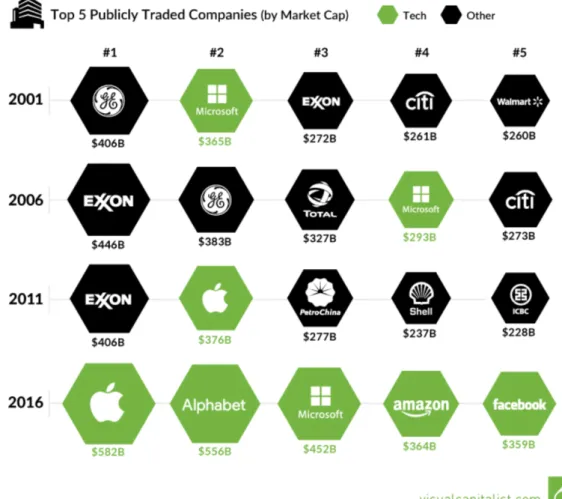

Figure 1 – 2025 Competitiveness Ranking Table Figure 2 – Largest Companies by market cap

Figure 3 – Domains of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Figure 4 – Boulder’s entrepreneurial System Components Figure 5 – The Lean Startup System

Figure 6 – Link NYC Figure 7 – LinkNYC

Figure 8 – LinkNYC at Manhattan

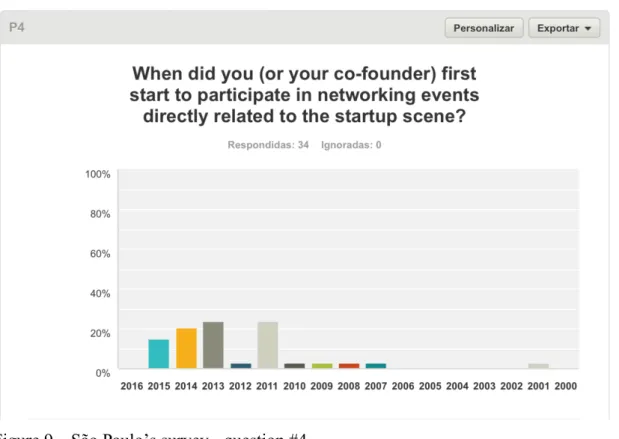

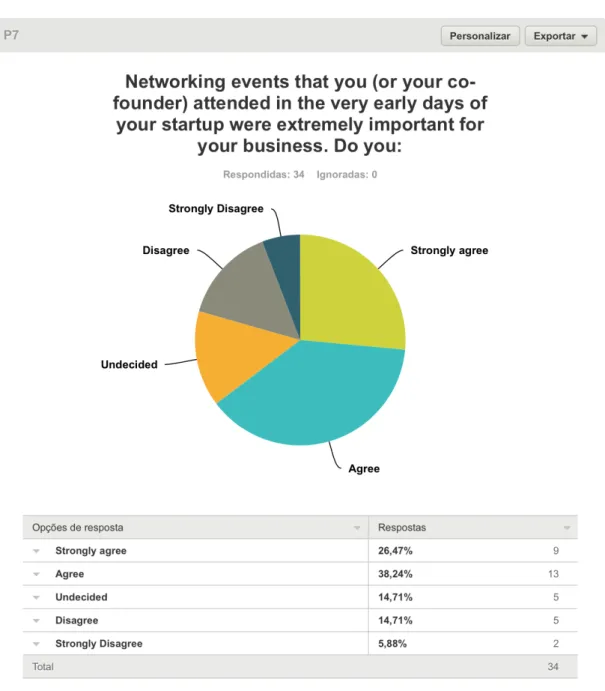

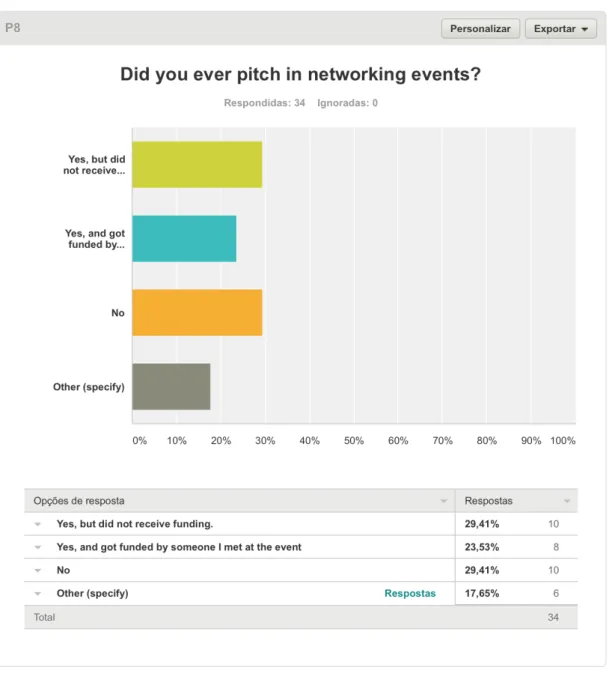

Figure 9 – São Paulo’s survey - question #4 Figure 10 - São Paulo’s survey - question #5 Figure 11 - São Paulo’s survey - question #7 Figure 12 - São Paulo’s survey - question #8 Figure 13 - São Paulo’s survey - question #12 Figure 14 - São Paulo’s survey - question #18

Figure 15 - São Paulo’s survey – Significant events’ outcomes

Figure 16 - São Paulo’s survey – Objective facts as events’ outcomes for startups Figure 17 - São Paulo’s survey - question #11

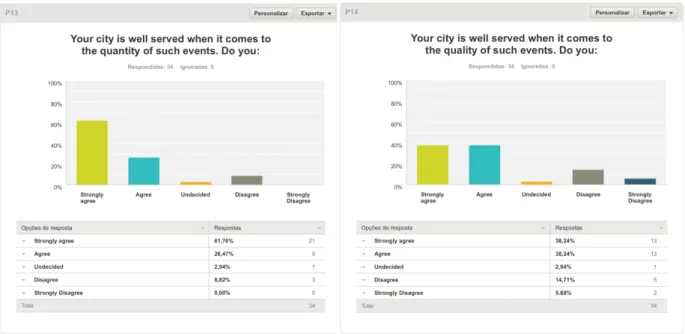

Figure 18 - São Paulo’s survey - question #13 and question #14 Figure 19 - São Paulo’s survey - question #15

Figure 20 - São Paulo’s survey - question #16

Figure 21 - São Paulo’s survey - question #17 Figure 22 – New York’s survey - question #7

Figure 23 – New York’s survey – Significant events’ outcomes

Figure 24 – New York’s survey – Objective facts as events’ outcomes for startups Figure 25 – New York’s survey - question #11

Figure 26 – New York’s survey - question #18 Figure 27 – Questionnaire

LIST OF ABREVIATIONS

B2B Business-to-Business

B2C Business-to-Customer

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CIPE Center for International Private Enterprise COO Chief Operation Officer

CTO Chief Technology Officer

CYS Chief Youth Servant

GDP Gross Domestic Product

FOMO Fear of missing out

Fintech Financial technology

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

NY New York

SP São Paulo

VC Venture Capital

ABSTRACT

In recent years, influenced by successful and high-profile benchmarks, entrepreneurship has transitioned from a definition for an unconventional professional with an idea to a mainstream career for millions of college graduates and experienced risk-takers. Therefore, this thesis analyzes the influences of networking events as critical resources for the success of startups in São Paulo and New York. Based on a survey conducted with more than 80 startups in both cities, and a series of interviews with several entrepreneurial ecosystem leaders, this thesis empirically shows the positive results that founders/CEOs receive by attending networking events. Furthermore, this thesis indicates some gaps as well as some opportunities regarding startup-related networking events that can foster the entrepreneurial ecosystem in both cities. Although numerous academic papers and research have identified the most important resources for creating, fostering, and consolidating an entrepreneurial hub, understanding the role of networking events will shed light on this specific subject.

13

1 INTRODUCTION

The catalyst that motivated me to write this thesis began in the fall of 2015. Based on an idea for a service that can be extremely valuable for tennis players, I decided to research how to build a technology startup from scratch and study the basics of entrepreneurship.

I come from São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city and Latin America’s largest business hub. Unfortunately, Brazil is not a well-known tennis destination, which inspired me to develop the business in the world’s largest tennis market: the United States. In this regard, two technology hubs immediately came to mind: Silicon Valley (given its world-famous resources for entrepreneurs) and New York (due to its booming technology and entrepreneurial ecosystem), after which New York was selected.

During my first months in New York, in order to learn about startups, entrepreneurship, and to enhance my network, I started attending networking events. In fact, I attended such events every day in order to learn as much as possible from experienced individuals and to make new connections in the field.

This experience was extremely valuable. After attending the events for several months, my understanding of how startups and entrepreneurship functioned significantly increased. Subsequently, the following questions were raised:

Are these events valuable for everyone that attends them? Were they really taking advantage of all of these events? Is it true that entrepreneurs should attend many of these events?

Do these events cause entrepreneurs to lose their focus on their startups, clients, and goals?

From these questions emerged the initial hypothesis for the present thesis; that is, networking events are important for entrepreneurs. However, a more in-depth study was warranted in order to understand how entrepreneurs determine which outcomes from the events are useful for their particular goals. Since I come from São Paulo, where entrepreneurism is receiving increasing relevance, I believe it would be useful

14

to understand the importance of such entrepreneur-related events for startups in the city and compare it to the results among the New York-based startups.

1.1 São Paulo and New York Overview

São Paulo, the largest city in South America (and in the Southern Hemisphere), is home to more than 11,6 million inhabitants (SEADE, 2016). As Latin America’s “main destination for business,” its metropolitan area population is the 10th largest in the world, while it is ranked 15th when considering its GDP. In addition, São Paulo’s metropolitan area is the 3rd largest GDP among developing countries, just after the

Chinese metropolitan areas of Beijing and Shanghai.

São Paulo (including its surrounding neighborhoods) is Brazil’s most important economic hub (Euromonitor, 2016), and it generates approximately 25% of country’s total GDP. The city’s labor productivity levels surpass the average for the rest of the country by a significant margin (104% in 2013), thus highlighting São Paulo’s position as Brazil’s leading financial and business center.

According to InvesteSP (2016) Sao Paulo includes 34% of all higher education institutions in Brazil, and it is responsible for 86% of the country’s investments in science, technology, and innovation. In addition, “Hot Spots 2025,” a report published by the “Economist” magazine (2013), ranked São Paulo 36th among the 120 cities that were considered as “benchmarks the future competitiveness.” It is important to note that New York was ranked 1st in this listing. Moreover, the report stated the following:

“São Paulo, Brazil’s commercial and financial capital is the most improved city in the Index. The city leapfrogs from the bottom half of the table today to 36th place in 2025. A young and rapidly growing workforce, a good telecommunications infrastructure, and the city’s openness are behind the surge in its competitiveness. Well-established democratic transitions and stable democratic institutions underpin its attractiveness for firms and people.” (page 06)

15

16

However, is the technology startup ecosystem in São Paulo as developed as that in New York? According to the U.S. Department of Commerce (BEA, 2015), the greater New York metropolitan area has produced $1.5 trillion dollars in GDP in 2014 alone, which is equivalent to the world’s 12th largest economy (Florida, 2014). New York was also ranked 2nd by Forbes in its 2014 listing of the World’s Most Influential Cities. Furthermore, a report from the Zicklin School of Business (McCarthy, K. 2014) accurately illustrates the importance of technology for New York:

“The New York City economy is continuing to expand because of growth in two major sectors: tourism and technology. Employment in these technology-driven, creative industries have grown twice as fast as the economy as a whole and are continuing to add jobs at a much faster rate. Today, employment in the TAMI sectors accounts for approximately 10% of total payroll employment in New York City, making it almost as large as financial services. And it is projected to continue adding jobs at a faster pace over the next several years. Fortunately the New York City economy has become more diversified over the past two decades and is not as reliant on financial services as it was in the early 1990s.” (page 04)

Overall, New York’s population of 21 million inhabitants is similar to that of São Paulo. However, it $69.9 thousand per capita GDP is by far larger than São Paulo’s $20.6 thousand (Global Metro Monitor, 2014)

1.2 Contextualization and Relevance of the Problem

The technological revolution started with the invention of the microprocessor by Intel in 1971 and the personal computer (PC) in the late 1970s. From these phenomena, combined with affordable, global Internet-access, emerged a new type of entrepreneur that focused on opportunities created by technology.

Over the past two decades, the business environment has changed dramatically and at an incredibly fast pace, especially since computers and Internet access have become readily available and affordable for companies and individuals. Traditional jobs, such as typists, switchboard operators, and file clerks (all common roughly 30 years earlier), simply disappeared from companies (Nazarian, A. 2014). The disappearance

17

of such positions, combined with the new technology that was available, led to the creation of new professions and business roles.

One of the most exciting opportunities that appeared as a consequence of this massive technology popularization was the freedom that people had to follow their professional insights, identify market opportunities, and develop new products and businesses. In other words, it was an era in which anyone could become an entrepreneur.

A few decades earlier, any professional that wanted to start a new company would have to face significant constraints such as knowledge restricted to academia; industrial equipment that required huge investments; final markets and customers that were not easy to access (especially overseas); credit from banks and other financial institutions that was not readily available. However, many studies have demonstrated an upward trend among U.S. companies, which, starting from the late 1970s began to shift from large firms to the emergence of small businesses (Brock and Evans, 1989; Acs and Audretsch, 1993). This process fostered the entrepreneurial economy in which performance is related to innovation and the emergence/growth of innovative ventures (Audretsch and Thurik 2001; Kirchhoff, 1994).

Despite such advances, the environment for new ventures has changed dramatically, due to the relative ease of acquiring information through the Internet. Since anyone with a computer can basically start a new business, the costs of starting a technology company have dropped considerably. According to Compass’ Global Startup Ecosystem Ranking 2015, the cost of product development has fallen by a factor of 10 over the past decade. The instant global connection has also made it fast and easy to access new markets and customers. In addition, raising funds has become easier since the banking industry has developed and new sources (such as crowd-funding) have emerged.

The astonishing success of innovative companies, such as Facebook, Whatsapp, Airbnb, Tinder, Snapchat, and Instagram, are motivating a significant number of young (and not so young) entrepreneurs to “try their luck” at starting a new tech

18

company. In this regard, as stated by Kacou (2001), entrepreneurship is nothing but the productive combination of innovation, initiative, risk, and capital.

Transforming and constantly improving the technology startup environment is crucial for any city that desires to be among the top places for a “new tech industry” and the home to entrepreneurs/companies that will lead the economy in the upcoming years. Studies have shown that a community’s entrepreneur support network, i.e., the organizations and institutions that make up its “ecosystem,” are critical for new firms to succeed (Motoyama and Watkins, 2014). For entrepreneurs to thrive, “a supportive ecosystem of intertwined factors ranging from infrastructure to financial access is mandatory” (Nadgrodkiewicz, 2014). Furthermore, the better the entrepreneurial environment is for startups, the greater their chances of succeeding and transitioning from small, ambitious, and early-stage companies into consolidated innovative enterprises that generate jobs, foster innovation, and create wealth for both stakeholders and the community.

1.3 Research Objectives

Among the many variables that impact a technology startup, the environment in which it is situated is one of the most important catalysts for success. In addition, startup hubs are much more likely to produce successful ventures, since many investors live in these hubs (and prefer to invest locally), and the top talent tends to move to such hubs to promote their businesses (Polovets, L. 2015) and gain access to funding, technical infrastructure, taxes and legal incentives, office space (and housing), staffing, incubator programs, etc.

The goal of this thesis is to understand how startup-related networking events (promoted by the community) influence successful startups in New York and São Paulo. Comparing the tech environment in both cities should provide a comprehensive understanding of what is occurring in this relatively new field. The “newness” of the subject makes it tremendously challenging on the one hand, but it is deeply relevant on the other, since the startups of today are meant to be the leading corporations of tomorrow.

19

The world is already witnessing a major change in the most valuable companies. Traditional industrial giants in the oil and banking industries that used to lead the rankings are being rapidly surpassed by revolutionary tech companies, some of which have been founded by college students, as seen in Facebook.

Figure 2 – Largest Companies by market cap. Source:

20

1.4 Structure of this Thesis

The structure of this thesis is as follows. First, it reviews the theoretical references and literature regarding entrepreneurship, startups, and the conditions required for a preeminent entrepreneurial environment. Based on prior relevant academic studies and other trusted sources (e.g., multilateral institution’ reports), this thesis contextualizes the most important concepts related to entrepreneurship.

Second, it highlights the importance of networking events and specifically focuses on how networking is occurring in startup ecosystems, specifically those in New York and São Paulo. Third, it presents quantitative and qualitative data obtained through questionnaires and interviews with the top management of several successful startups and other important ecosystem personalities.

Fourth, it analyzes the results under the entrepreneurial prism in order to identify the gaps, opportunities, and challenges. Finally, it presents the conclusions as well as suggestions for future studies.

2 RESEARCH QUESTION AND OBJECTIVE

New York and São Paulo, both of which play leading roles in their countries as the most vivid, wealthy, and powerful metropolitan areas, have become leaders in providing startups with a stimulating environment for innovation. Thus, this thesis examines the importance of networking events for startups and demonstrates the most important benefits of such events, according to the sample of founders/CEOs.

2.1 General Objective

The general objective of this thesis is to understand the impact of networking events for startups in New York and São Paulo by underlying the main similarities/differences between them. From reading this thesis, any researcher/entrepreneur will be able to understand the “pros and cons” of startup networking events in each of the aforementioned cities. In addition, this thesis

21

underlines the successful initiatives and actions (both private and public) that have worked in one city and suggests how it might also work in the other.

2.2 Specific Objectives

The comparison of the networking events for technology startups in São Paulo and New York will focus the main impacts of such events. The purpose of this thesis is to research these topics in order to make a reliable comparison between the two cities.

The rationale behind the selection of this subject is that a solid and mature environment is one of the most important drivers to boost a tech company. Moreover, having an organic and dynamic technology cluster is considered by some of the best and most successful entrepreneurs as a major catalyst for startups to fulfill their potential and achieve their most ambitious goals.

Finally, this thesis underlines the outcomes of attending such events, based on the interviews with startup founders and top management. The overall goal is to determine if the general perception that “events are important” can be translated into “crystal-clear” information for startups, especially in regard to long-term success.

3 THEORETICAL REFERENCES

3.1 Network DataAccording to Hanneman and Riddle (2008), there is a conceptual difference when analyzing network data; that is, conventional data focuses on actors and attributes, whereas network data focuses on actor and relations. Hanneman and Riddle also stated, “The difference in emphasis is consequential for the choices that a researcher must make in deciding on research design, in conducting sampling, developing measurement, and handling the resulting data.” In addition, they emphasized that the tools are the same for network analysis as they are for other social scientists, but “the special purposes and emphases of network research do call for some different considerations.”

22

3.2 The Pillars for a Successful Startup Environment

Entrepreneurship is a powerful ingredient for generating jobs, fostering innovation, and unleashing the creative potential of the new generation born during the technological revolution. In addition, entrepreneurship is inspiring wealth creation and increasing competitiveness, thus leading to better products/services and opening new markets.

As entrepreneurship relevance has grown exponentially over the past years, its definition has also received significant attention. An insightful analysis of this phenomenon was presented by Audrestsch (2007), who stated, “The entrepreneurial society has emerged as the pro-active and positive response to globalization, where change is the rule and innovation the source of competitiveness, growth, and jobs.” Moreover, Bettecher (CIPE, 2014, page 07) concluded that “entrepreneurship drives economic change and innovation while at the same time expanding opportunity,” while the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (a global reference trusted by several key international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank and the World Economic Forum) defined entrepreneurship as “any attempt at new business or new venture creation, such as self-employment, a new business organization, or the expansion of an existing business, by an individual, a team of individuals or an established business.”

A widely accepted framework for understanding the critical factors of a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem was designed by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The list consists of six main factors: (1) regulatory framework; (2) market conditions; (3) access to finance; (4) creation and diffusion of knowledge; (5) entrepreneurial capabilities; and (6) entrepreneurship culture.

The Babson Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Project, developed by Babson College (one of the most entrepreneurship-driven educational entities in the United States), also introduced a useful framework that they called the “Domains of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem.”

23

Figure 3 – Domains of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. Source: Babson College.

Another important study on entrepreneurial ecosystems was conducted by Neck et al. (2004) in Boulder County, Colorado. Neck identified six important elements as the most important ones, based on a survey of more than 180 founders and informal interviews conducted with five well-regarded venture capitalists. The six factors include: incubators, spin-off firms, formal and informal networks, physical infrastructure, and culture (Figure 4).

24

Figure 4 – Boulder’s entrepreneurial System Components. Source: Neck et al.

In addition to the conventional pillars that most of the theoretical references have mentioned, it is important to emphasize what Robert Litan (CIPE, 2014), Director of Research for Bloomberg Government, stated: “There is a virtuous cycle here: entrepreneurial success breeds more success, attracting individuals and capital to entrepreneurial pursuits.”

25

3.3 The Emic Approach

The methodological approach used on this thesis will be described on the following section. It is important, though, to briefly mention that this study started from a broad perception that networking events were important to successful founders/CEOs. And from that perception emerged the idea of conducting an exploratory approach to research the subject in details.

On section 7.3, this thesis suggests further studies that should be considered on this field. In this matter, it is relevant to highlight that the “Emic Approach” could be appropriate for future research. In regard to this “emic approach” Willis (2007) on the Foundations of Qualitative Research in Education from Harvard Universitystated:

“In taking an emic approach, a researcher tries to put aside prior theories and assumptions in order to let the participants and data “speak” to them and to allow themes, patterns, and concepts to emerge. This approach is at the core of Grounded Theory.” (page 101)

Since this specific research topic (i.e., networking events for startups) has not yet been theorized (given its newness), this approach could be the most favorable one available. In this regard, Borgatti (1996) stated the following:

“Although not part of the grounded theory rhetoric, it is apparent that grounded theorists are concerned with or largely influenced by emic understandings of the world: they use categories drawn from respondents themselves and tend to focus on making implicit belief systems explicit.” (page 02)

3.4 The Cultural Difference that Drives Productivity

There is a major cultural difference that should be highlighted in order to understand the events dynamics in New York and in São Paulo.

In Brazil, there is a behavioral pattern that Sergio Buarque de Hollanda described in his work titled, “Raízes do Brazil,” as “homem cordial” (“cordial man”). As per Boff’s (2014) description, “Sergio Buarque understands cordiality in the strictly

26

etymological sense: that which comes from the heart. Brazilians are ruled more by the heart than by reason.”

This cultural Brazilian trend makes the dynamics for networking events significantly different from those of the United States. More specifically, Brazilians need to create some empathy or a sense of intimacy with someone that they had just met before discussing any business-related activities. Initially, this Brazilian characteristic may seem unimportant for the present thesis, but it is extremely meaningful since networking events are only held for a limited amount of time. Thus, the more useful, productive, and straightforward a participant can be during a certain amount of time, the greater the possibility that he/she can achieve a certain outcome. In this regard, Americans are more likely to “jump” into an objective and productive conversation faster than their Brazilian counterparts. As a result, such productivity might lead to better outcomes, especially in events where the key to success is directly related to efficiently networking with as many attendees as possible.

3.5 Startup Definition

The term “startup” is not a new one, but since the mid-1980s, its significance and popularity have greatly increased. Blank and Drof (2012) provided one the best definitions for a startup; that is, “A startup is an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model” and that “A business model describes how your company creates, delivers, and captures value.”

Essentially, a startup is an organization disrupting an existing market based on the introduction of a new technology, a new product/service or by introducing a new doing-business approach. The lean methodology (Ries, 2011) consolidated the framework of a typical startup flow and set the tone for startup development.

27

Figure 5 – The Lean Startup System. Source: The Lean Methodology

Startups are, by definition, “scalable,” which means they are built to exponentially grow at an extremely fast pace. However, they have a much higher risk of failure in comparison to traditional small businesses. According to a study by Compass (2015) the possibility of success for traditional small businesses in the first two years is 75%, whereas the failure rate for startups during the same time period is also 75%

3.6 Networking

Significant literature has focused on the concept of networking and its impact on managers’ careers. Among the numerous studies, Borgatti and Foster (2003) and Brass and Burkhardt (1992) underlined the benefits associated with networking behaviors such as better pay, promotions, and the ability to be more effective and influential (Cohen & Prusak, 2001).

In their work on networking and organizations, Brass, Galaskiewicz, Greve, and Tsai (2004) highlighted the relevance of networking: “Network ties transmit information and are thought to be especially influential information conduits because they provide salient and trusted information that is likely to affect behavior.” In regard to organizations, McCallum (2008) indicated that they benefit from networking by

28

improving access to financing and potential strategic partners, while lowering turnover rates.

3.7 Networking Event Definition

For the purpose of this thesis, the term “networking event” is an organized meeting promoted by any organizer/entity with open/limited attendance of at least 10 people. In this case, private meetings, business meals, small conference groups, and academic classes were not considered as “networking events.”

Regarding the survey sent to the sample of entrepreneurs and founders/CEOs (that will be detailed on the upcoming chapters of this thesis), the following disclaimer was introduced:

Networking events related to startups and entrepreneurship are events such as meet-ups, hackathons, pitching events, master classes, seminars, webinars, happy hours, etc. Private meetings and educational programs are not considered networking events.

4 METHODOLOGY

This thesis includes a methodology based on the “exploratory model,” and it does not focus on creating a model to research the hypothesis in full statistical complexity and certainty.

The exploratory approach was chosen in order to perform a broader analysis of the literature (both academic and non-academic), and to conduct interviews (presented on chapter 4.6) to better understand the variables that were previously unclear.

4.1 Research Approach

In this thesis, the formal scientific construction is Sistematicity (Migueles, C. 2016) since the theme is treated in a broad manner, and there is no intention to explain it all. In addition, entrepreneurship is the subject of focus, which is a relatively new research field with limited research on designated methods (Florica Tomos et al.,

29

2015), especially those regarding networking events for startups. In addition, Tomos et al (2015). indicated the following:

“Across different research fields, there was an emergence of innovative ways of mixing quantitative and qualitative research methods, and an effort to form the foundation of a new research method–mixed method research (MMR).”

Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) presented their definition of mixed methods as follows: “Mixed methods research is formally defined here as the class of research where the researcher mixes or combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques, methods, approaches, concepts or language into a single study.” Even though there are quantitative traditions deeply related to certain business and management disciplines, mixed methods research is still being applied and reported within business and management fields (Cameron, 2011).

Furthermore, the present thesis is based on information obtained by both quantitative and qualitative research methods. Regarding the quantitative prism, the data was gathered from research on the technology industry, including industry reports, magazines, government data, and information generated by startup associations. Quantitative data was also generated through a questionnaire that was developed in order to foster insights and answers regarding this subject and sent to the top managers of startups in both cities.

Concerning the qualitative prism, referring to various information sources and conducting a series of interviews generated valuable data for this thesis. Mildred Patten (2015), in the book titled, “Proposing Empirical Research,”i stated that “the

purpose of qualitative research is to gain in-depth understanding of purposively selected participants from their perspective.” For the qualitative research in this thesis, the main sources included the following (see the Appendix for more detailed information):

Government

Faculty in FGV, ESADE, and Georgetown (especially professors involved in entrepreneurship)

30 Startup CEOs Startup top-management Startup Associations

Entrepreneur’s forums and meetings Venture-capital funds

Lawyers’ firms familiar with the startup scene

4.2 Bifocal Analysis

In regard to addressing the proposed subject, it is important to shed light on the relevance of what Coviello (2005) referred to as the “bifocal approach.” This approach emphasizes the necessity to interpret data from two perspectives: qualitative and quantitative. Coviello also suggested that the following: “Since networks encompass both qualitative and quantitative dimensions, network research methodologies should be able to accommodate both ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ data.”

This bifocal analysis aligns with the mixed method research approach (described in the previous section).

4.3 Quantitative Research

To better understand the impact of networking events as catalysts for startups’ success, this thesis conducted a survey with founders/CEOs of startups based in São Paulo and New York.

4.4 Delimitation of the Universe

4.4.1 Sample:

In order to quantitatively understand the impact of networking events as catalysts for startups’ success, this thesis created a filter to select the startups’ founders/CEOs that would participate in this survey.

31

In this process, this thesis considered that an eligible, successful startup was a venture that fulfilled at least one of the following economic criteria and one of the following operational criteria. Startups that fulfilled at least three of the criteria were also accepted for this survey, even if they only concentrated on the economical or operational prisms.

4.4.2 Economic Criteria:

1) Received at least US$300,000 in investments. This criterion reflects the attractiveness that a startup has for the angel-investor community and venture capitalists. Raising capital is a milestone for every startup. Thus, being able to successfully complete this task was set as a criterion.

2) Achieved an economic break-even point. Being able to set up a startup and reach the break-even point is a significant accomplishment that only a small percentage of entrepreneurs achieve. This is the reason why this criterion was conceived.

3) Achieved “exit for the early-investors.” When early-investors can generate a successful “exit” from their investors, this means that these investors had a return over the capital invested, and that the startup value is increasing. This was the rationale for including this criterion.

4) Generated at least US$500,000 in revenues in 2015. This was one of the most objective criteria in the list. Startups are sometimes incapable of generating orders and revenues. Thus, setting up a revenue benchmark was included as a criterion.

5) Reached a US$10 million (or above) market valuation. Pre-revenue and pre-traction startups are difficult to value. Founders usually struggle to set their valuation before such data is generated. However, there is a market consensus pointing out that early-stage startups’ valuation can range from US$1.5 million to US$5 million. This was the reason why this thesis set a US$10 million valuation as a criterion.

32

4.4.3 Operational Criteria:

6) Filed at least five patents. Patents are a clear sign that a company is working hard on innovations as well as research and development. Thus, the first criterion was created to embrace such companies.

7) Employs 10 people or more. One can say that companies with a large number of employees might fail. However, it is unlikely to see a successful business with a small headcount. In addition, having a payroll with 10 people or more usually indicates that the company is capable of managing its finances and paying its professionals.

8) Established three (or more) years ago. This criterion was set in order to embrace companies that are surviving in the fast-changing startup environment. Being at least three years of age demonstrates that the startup management is resilient and capable of surviving.

9) Received significant coverage by the mainstream press. For this criterion, the word “mainstream” was used to avoid second-class media and paid press. Mainstream press usually (but not always) focuses on relevant businessmen and companies. Thus, this criterion was included as a measure of success.

10) Considered as one of the top three competitors in the specific market. Any company that managed to reach the top-3 position in its market is likely to be successful. Some companies can be positioned in a “winner-takes-all” market, but there is usually room for more than one competitor, and being in the top 3 is a considerable achievement by a startup.

As stated earlier, a questionnaire was developed and sent to the founders/CEOs (and C-level managers) of more than 150 São Paulo- and New York-based startups. Any questionnaire that did not fulfill the suggested filter was discarded.

The startups (represented by its CEOs/founders and C-level managers) that returned and qualified to participate in this survey were as follows:

33

São Paulo:

Omnize Software – CEO Trustvox – CEO SouGenial – CEO Verios – CEO Linte – CEO RankMyApp – Founder Ponte21 – CTO ZUP – Founder CarreiraBeauty – Founder Kitado – Founder Fhinck – CEO Inviron – CEO Athenas – CEO

Minuto Seguros – CEO Ventrix – CEO

Elefante Verde – CTO Moneto – Founder & CEO Clicksign – CEO

Smartbill – CEO Omie – CEO Izio – CEO Medicinia – CTO

34

Parafuzo – COO

Broou e Numooh – Co-Founder VRMonkey – CEO

Memed – COO

ComparaOnline – Director Confirm8 – CEO

Bongolog Logistica – Co-Founder Worldpackers – CEO

Nexoos – Co-Founder & CEO One Sports – Co-Founder Cubee – Co-Founder Evnts – CEO

New York:

InList – Founder and CEO Dressometry – CEO X.ai – CTO

AirHelp – CEO YieldBot – CEO

Findmine – Founder and CEO Troops – Co-Founder

IrisVR – Co-Founder and CTO Homepolish – Co-Founder

35

Sols – CEO

Scopio – Founder & CEO Wade & Wendy – Co-Founder Vestwell – Founder & CEO Wellth – CTO

Latam Founders – Founder AllTheRooms – Co-Founder Sailo – Co-Founder

Teckst – Founder & CEO

Youthful Savings – Founder & CYS RapidSOS – CEO

The Room Ring – Co-Founder

4.5 Qualitative Research

A series of interviews with preeminent personalities in the entrepreneurship environment was conducted in order to discuss the subject of this thesis as well as understand their opinions regarding the results from the quantitative research.

These interviews offer a different perspective from the one extracted from the survey, since the participants were not startup founders (or top managers), but individuals from governmental offices, managers for class associations, venture capitalists, event organizers, incubator leaders, etc..

Since the entrepreneurial environment is a combination of all of these entities and the people that lead them (as described in Chapter 3), listening/analyzing the inputs of these professionals would help us better understand the subject as well as bring new perspectives that can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the subject in question.

36

4.6 Interviews

The interviews were conducted in order to understand how key people in São Paulo and New York analyze their respective events.

The interview process followed the same structure. First, the interviewees were invited to comment about the startup scene in their cities, from a general perspective. Second, the interviewees were encouraged to mention the main “pros and cons” for startups in their respective cities. Finally, the interviewees were asked to analyze the events that occur in their respective cities, especially regarding their quality, quantity, and their importance for startups.

The interviews in São Paulo were conducted personally. New York interviews were conducted via teleconference. Interviews were done between June and August 2016 and the average interview time was 45 minutes.

4.6.1 São Paulo

In this thesis, the following individuals were interviewed:

Tony Celestino: Managing Director for Tech Stars in São Paulo. Celestino leads the

strategy to support the growth of the Brazilian startup and innovation ecosystem by empowering hundreds of community leaders through various startup programs.

Celestino stated that he is a true believer of the impacts that networking events have on startups. Being part of the startup scene for several years and serving as a Regional Director for Tech Stars (one of the world’s largest accelerators and incubators in the world), Celestino sees a boom (both in quantity and quality) in the networking events in São Paulo.

Michel Porcino: Director for São Paulo Negocios and Tech Sampa. Created by São

Paulo City Hall, Tech Sampa’s goal is “to attract new ventures (mainly startups) with high growth potential, provide a support framework for the various stages of development, and connect the new companies with other tech-startup excellence centers worldwide”.

Porcino stated that São Paulo’s tech scene is growing rapidly and that the city is a major hub for entrepreneurship. He understands that the city offers many events, and

37

that the number of events should continue to grow in the upcoming years. Part of his job is connecting people, companies, and mentors as well as making São Paulo an attractive hub for innovation. Thus, he strongly believes in the power of these events on increasing the success rates of startups.

Fernando Tomé: Institutional Relations at Circuito Startup Brasil, a business network

that supports entrepreneurs and builds startups. Tomé stated that São Paulo is Brazil’s “Silicon Valley” and consequently, it is the country’s natural hub for entrepreneurship and startup development. As a leading personality in Brazil’s entrepreneurship ecosystem, he reported that startups from all over the country need to spend some time in São Paulo before undergoing international expansion.

Tomé also revealed some frustrations when discussing the general entrepreneur’s profile. He mentioned that a significant portion of those that approach the scene are not actually entrepreneurs. In other words, they are just “checking out the scene,” regardless of whether they have an idea of what it takes to be successful. He also reported that the local entrepreneurship community needs much more education, knowledge, and consistency in order to become “real” entrepreneurs. This is why Tomé sees opportunities for his company to help potential entrepreneurs become real one by providing mentorships and establishing connections.

Santiago Fossatti: Principal at Kaszek Ventures, “the leading Latin American venture

capital firm investing in high-impact tech entrepreneurs.” Led by Nicolas Szekasy, MercadoLibre’s former CFO, and Hernan Kazah, MercadoLibre’s co-founder, the firm “actively supports its portfolio companies through value-added strategic guidance and hands-on operational help, leveraging its partners’ successful entrepreneurial backgrounds and extensive network.”

Fossatti stated that his company attends networking events for marketing purposes. When asked if they had ever invested in a company (or an entrepreneur) after meeting the representative at a networking event, he stated that it had never occurred. However, he mentioned that networking events are good for those who are somewhat unfamiliar with entrepreneurship, and reported that the CEOs of Kaszek’s portfolio companies would only attend networking events as speakers. He did add that some of their staff members attend the events in order to recruit talent.

38

Flavio Pripas - Head of Cubo, one of the main hubs for startups in São Paulo. Cubo’s

mission is to foster the Brazilian startup ecosystem by inspiring, educating, and connecting what they call “great people” in the local tech scene. Pripas stated that Brazilian entrepreneurs are critical to the country’s future and they can improve people’s everyday lives. Thus, the venue promotes the intersection of entrepreneurs, mentors, academic research, investors, and corporations in order to increase the potential for successful ventures.

Pripas reported that Cubo offers approximately a dozen events each week, and mentioned that they occasionally host up to four events in the same day. However, he stated that the quality was not always the same, especially since Cubo is generally not in charge of the companies/entities that participate in the events. In fact, most of the time, Cubo simply provides their offices or their auditorium free of charge in order to foster the ecosystem.

Pedro Englert: CEO and investor at Startse. For Englert, the local ecosystem is still

amateur at best. He stated that there are some good clusters, but the ecosystem, as a whole, is not effectively connected. He understands that there is a lack of consistency in the ecosystem and that the community needs more education and knowledge. According to Englert, São Paulo is going through a process in which the quantity and quality of networking events are rapidly increasing. He also stated, “we might not be there yet, but we are getting closer and closer to have an appropriate quantity of networking events in São Paulo.” On the other hand, he mentioned that there is a lack of quality in these networking events and he emphasized that, out of São Paulo, in Belo Horizonte and Santa Catarina, there is a lack of events and an entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Raul Juste Lores served as the Washington, D.C. Bureau Chief of Folha de São Paulo

(Brazil’s largest newspaper) from 2012 until 2015. Previously, he had the same role in New York, where he was involved in the technology and entrepreneurship scenes. At Folha, he was also the Beijing correspondent for almost three years. Besides China, he also covered Asia (from Iran to Japan) from 2007 to 2010. He was also the Business Section Editor (both print and online) from 2010 to 2012.

39

Lores stated that there is a major cultural issue for entrepreneurship in Brazil and São Paulo, when compared to the United States and New York. He stated that one of most important aspects was the emphasis that universities (both professors and the entities themselves) place on entrepreneurship and research. In this regard, he mentioned that, in the United States, it is extremely difficult to find a university that does not foster entrepreneurship among its students. However, in Brazil, there is the opposite scenario; that is, only a few top universities strongly emphasize entrepreneurship as a career option and a major path to development. He stated that, at the moment, we should be seeing large universities produce graduates that generate hundreds of startups each year, but this is not the case.

Lores also stated that the startup and entrepreneurship events in São Paulo are usually reaching out to the same crowds, even though there are some different hubs such as Cubo, Google Campus, and Oxigênio. That being said, he mentioned that there is a demographic problem in São Paulo, since the majority of entrepreneurs are coming from upper-class families and top-notch universities, which means that those from the lower and middle-class do not represent a considerable fraction of the entrepreneurs in the country. According to Lores, this lack of representation has led to another problem; that is, since the “prism” of opportunities and ideas from the entrepreneurs are always the same, more diversity is necessary to inspire different startups to emerge.

Another difference Lores mentioned was the quantity and quality of the events. He reported that, in New York, there are many different subjects covered by these events, while in São Paulo, most of them involve pitching ideas and mentorships. In addition, the entrepreneurial ecosystem is much younger in Brazil than in the United States. He also stated that, in the United States, it is common to find people between 18 to 25 years old with an amazing entrepreneurial background, whereas, in São Paulo, the entrepreneurs are usually older.

Finally, he mentioned that accepting failure (as a natural result of being an entrepreneur) is also a major difference between the two cultures. More specifically, Americans (in most cases) understand and still respect you upon failure, and the legal structure allows you to continue on and “reinvent” your career. In Brazil, failing is a

40

disgrace and the loss of respect is a natural outcome. Moreover, one may face judicial troubles for years after the event. According to Lores, “it can be a nightmare.”

4.6.2 New York

Marcos Dinnerstein is the Editor for Digital.NYC, the so-called “official hub of the

tech and startup ecosystem in New York City.” Digital.NYC is a “public/private initiative, sponsored by the Mayor’s Office and the NYC Office of Economic Development, in partnership with IBM, Gust, and more than a dozen prominent tech and media companies in New York City”. As Editor of Digital.NYC, Dinnerstein describes his job as connecting everything; that is, people to information, people to opportunities, and people to people.

Digital.NYC’s mission is to be the one-stop location in which one will find everything necessary to support and nurture the tech and startup community in New York. Dinnerstein started by talking about the entrepreneurial strength in New York and its most famous and largest meet-up, NYTech, which is also the largest in the world. When asked about the quality of the events in New York, he did not hesitate to say that they are usually at a high level.

Dinnerstein highlighted the efforts to embrace computer science for all initiatives in New York. In this regard, they are attempting to add computer science courses to classrooms, with strong support by Mayor De Blasio. Another significant effort is the LinkNYC program in which kiosks (installed throughout the city streets) provide free, high-speed Wi-Fi, phone calls, device charging, and a stationary tablet that has access to city services, maps, and directions. In this regard, he stated, “They are still in beta stage; that is, the initial stage. However, it is significant initiative and I am sure that they will make it a great one.” In September 2016, there were more than 400 kiosks installed throughout the city. The overall goal is to have 7,500 kiosks installed by 2020.

41

Figure 6 and 7 – LinkNYC.

Source: http://www.theverge.com/2014/11/17/7235481/new-york-city-to-provide-free-gigabit-speed-public-wi-fi-for-everyone

Figure 8 – LinkNYC at Manhattan

Source: http://www.theverge.com/2014/11/17/7235481/new-york-city-to-provide-free-gigabit-speed-public-wi-fi-for-everyone

42

At the end of the interview, Dinnerstein mentioned that networking is essential, and learning from others and exchanging information/ideas is equally important. He also stated that networking is what makes cities much more powerful than rural areas. Large companies, such as Microsoft, Google, and IBM, are supporting free tech training and making their spaces available to support groups. Such companies can be perceived as contributing members to an effective ecosystem. Finally, when asked about some negative points for entrepreneurs in the city, Dinnerstein mentioned that housing was one of New York’s major problems. Due to the extremely expensive real estate, he hoped that more affordable options could help entrepreneurs.

Erik Grimmelmann is the President of New York Tech Alliance, an entity that was

formed as a result of a merger between the New York Tech Meetup and the New York Technology Council. With more than 60,000 members, the New York Tech Alliance’s mission is to “represent, inspire, support, and help lead the New York technology community and ecosystem to create a better future for all.”

Grimmelmann, given his privileged position, has a deep understanding and knowledge about New York’s tech and entrepreneurial scenes. He stated that “innovation comes to New York wave after wave, continuously,” and that one of the main benefits for startups in the city is the proximity to clients. Since he strongly believes that companies should be near its customers, it is natural that the city has become a hub for entrepreneurship. In addition, he mentioned that technology is even being applied in non-tech industries such as real estate, fashion, fintech, healthcare, media, etc. According to Grimmelmann, “New York has all of them.”

He also emphasized that entrepreneurs find some of the most important ingredients that they need to succeed: money (angels, VCs, private equity firms), workspaces, lawyers, accountants, advertising, students (at least “500,000,” in his words), talent, and organizations. Regarding networking events, he stated that New York “has dozens of them happening every day” and that the city is home to more than 1,800 active meet-ups and organizations that continuously stimulate the industry. In his words, “excitement and inspiration are here.” Moreover, he mentioned that, given New York’s natural vocation as an immigrant destination, the city also benefits from the diversity of the population since such individuals bring a lot of entrepreneurial spirit, innovation, and dynamicity.

43

When questioned about any negative aspects that New York-based startups might face, his answer was similar to that of Dinnerstein; that is, “New York City is expensive and some people find it too crowded.” Although he stated that the city has a fierce competition for talent, he did add that “this is not only our problem, but it is a concern of everywhere else.” Finally, he mentioned that some industries, such as pharma and biotech, are not as developed. .”

Reza Chowdhury is the founder and CEO at AlleyWatch. As reported in the

company’s profile, AlleyWatch is “a news, culture, and technology media property dedicated to startup news, opinions and reviews, investment and product information, events reported, experienced, seen, heard and overheard in New York and beyond.” In addition, AlleyWatch has become “the first read and largest publication for venture capitalists, angel investors, entrepreneurs, accelerators, incubators, startup employees, thought leaders, event organizers, corporate executives, academics, city officials, PR/press and tech enthusiasts.” Based on my experience in New York, this description is correct since practically everyone in the city follows AlleyWatch’s news, articles, and events.

Chowdhury also mentioned that New York City’s entrepreneurial ecosystem had a boom after the 2008 financial crisis. As widely known, former mayor Michael Bloomberg focused on creating an environment to foster innovation and entrepreneurship, which was a turning point for the city. In addition, the city has tremendous expertise in many traditional industries such as finance, media, advertising, fashion, real estate, etc., so one characteristic of the New York entrepreneurs is that they tend to focus on real problems for existing industries, which is a major difference from Silicon Valley, where innovation is aimed toward changing traditional human behaviors.

He also stated that New York startups are more focused on results and cash generation than other entrepreneurial hubs. Regarding the city’s qualities, Chowdhury highlighted the capital availability, the diversity, the open environment, and the collaborative people. He added, “Another great thing for startups is that they are only a few blocks away from their clients.”

Regarding the negative aspects for entrepreneurs, they were similar to those mentioned earlier; that is, the city is extremely expensive for housing, office space,

44

and talent. In some cases, it is almost prohibitive. An additional challenge for startups in New York was recruiting engineering professionals, “since they are not as abundant as they might be in Boston, for instance..”

Talking more specifically about the networking events themselves, he did not show that much enthusiasm. He stated, “Events are great for knowledge sharing and networking. But sometimes I ask myself if people are building real business in those events. Maybe they are too social and less needed from the educational perspective.” He also mentioned that it is easy to eat lunch/dinner for free at these events, and some people actually do it every day. So, in order for events to be valuable for entrepreneurs, they have to know who is inside the room or it could be a waste of time. He concluded by adding, “I do not believe that these events are tremendously important. Warm intros and good references can be much more efficient.”

5 ANALYSIS OF THE RESEARCH RESULTS

5.1 São Paulo Survey5.1.1 Respondents overview

Between August and September 2016, 51 startups in São Paulo replied to the questionnaire.

Out of the 51 startups that responded, 28 (54.9%) fit the requirement of accomplishing one operational criterion and one financial criterion, while six companies (11.8%) accomplished three of the criteria (regardless of whether they were all operational or financial), thus totaling 34 startups (66.7%). Since the remaining startups (33.3%) did not fulfill the criteria, their answers were not considered in this thesis.

Among the startups that qualified to participate in this survey, the responses came from CEOs (52.9%), founders (29.4%), and other C-level employees (17.7%).

45

5.1.2 Questionnaire outcome

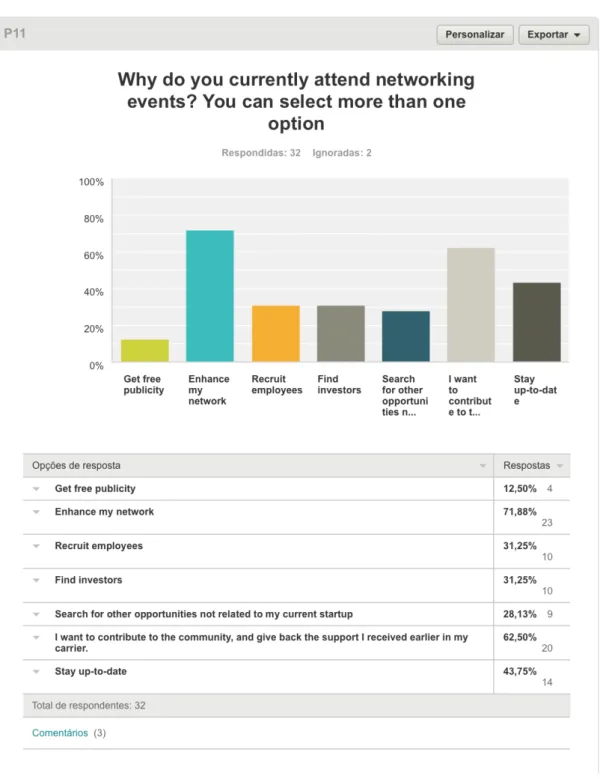

Among the data obtained from the survey, the most valuable are presented in the following sections.

Events held during the startups’ early days

Figure 9 – São Paulo’s survey - question #4

Since São Paulo’s startup scene is fairly new, 58.9% of the respondents started participating in them from 2013 and on. If 2011 is included, then the percentage increases to more than 80%. This describes the newness of São Paulo’s ecosystem, especially if compared to benchmarks such as Silicon Valley, New York or Tel-Aviv.

46

Figure 10 - São Paulo’s survey - question #5

In addition, 41% of the respondents that attended events during the early years of their startups had a specific goal. However, the information that one can learn from this question is that there was not one entrepreneur that was motivated to attend such events presented by academia. This subtle detail explains how incipient entrepreneurship is within academia in Brazil. In fact, it would not be surprising if a significant share of the respondents mentioned “academic reasons” if this survey was

47

conducted in countries where entrepreneurship and universities had strong connections. Another interesting finding was that more than one-quarter of the participants’ “entrepreneurial feelings” motivated them to attend such events in order to search for new ventures.

Figure 11 - São Paulo’s survey - question #7

This question identifies the first pattern regarding how entrepreneurs generally feel about such events. By combining the responses of “agree” and “strongly agree,” 65% of the respondents believed that these events were extremely important for their

48

businesses. Conversely, only 20% of the participants disagreed (or strongly disagreed) with the proposed statement.

Figure 12 - São Paulo’s survey - question #8

Figure 12 offers valuable information about the importance of such events for startups in regard to raising capital. Among all of the companies, 23% have raised funds due to events in which they have pitched their businesses. In addition, two entrepreneurs that have chosen “other” as an option stated that they raised money directly from individuals that they met at these events, which brings the statistics to 10 out of 34 (29.4% of the respondents).

49

Furthermore, if the startups that never attempted to raise money through these events (i.e., those that answered “No” to this question) are not taken under consideration, then 10 out of 24 (41.7%) actually succeeded in raising capital through such events.

The perceived importance of these events

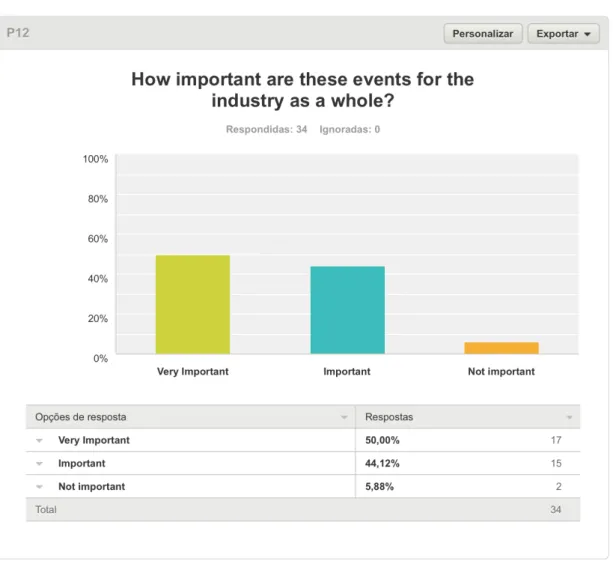

Figure 13 - São Paulo’s survey - question #12

This question demonstrates a close-to-unanimous view that unites founders, CEOs, and C-level managers; that is, they consider such events important for the industry as a whole. Furthermore, half of the respondents considered them extremely important. Even though this response is somewhat expected (due to their relevance), it is still surprising to find that 5.88% of the respondents did not consider the events important to the industry.

50

Figure 14 - São Paulo’s survey - question #18

This chart (Figure 14) presents some controversial data, especially when compared to the previous chart (Figure 13). Although approximately 95% of the respondents believed that the events were important/very important to the industry as a whole, 38.2% disagreed (or strongly disagreed) with the statement that events are clearly a success trigger for startups. In fact, only one participant strongly agreed with this statement. It is important to note that, despite not being close-to-unanimous (as it was for the previous question), more than 60% of the respondents agreed with this statement.

51

Survey’s key question

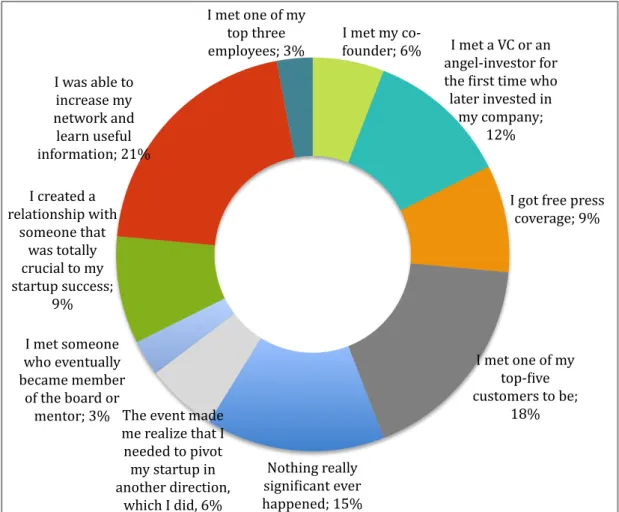

The purpose of this survey was to identify whether networking events are actually important for startups’ success. This was the main reason why this particular question was selected as the highlight of the survey.

What was the most significant outcome for you (and/or your co-founder) from attending a networking event?

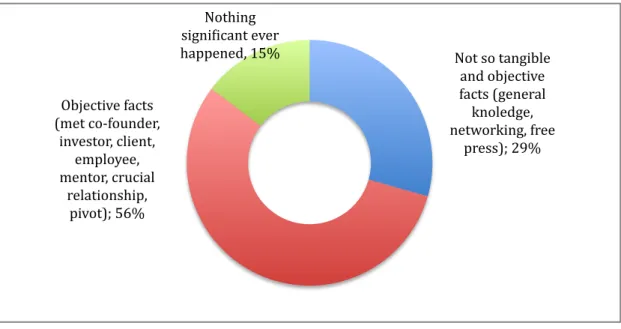

Figure 15 - São Paulo’s survey – Significant events’ outcomes

By presenting the aforementioned question, the purpose was to guide the respondents to think objectively about the outcomes of attending such events and how they were critical for their success.

I met my co-founder; 6% I met a VC or an angel-investor for the Dirst time who later invested in my company; 12% I got free press coverage; 9% I met one of my top-Dive customers to be; 18% Nothing really signiDicant ever happened; 15% The event made me realize that I needed to pivot my startup in another direction, which I did, 6% I met someone who eventually became member of the board or mentor; 3% I created a relationship with someone that was totally crucial to my startup success; 9% I was able to increase my network and learn useful information; 21% I met one of my top three employees; 3%