|NSTTTUTO DE C|ÊNCTAS SOCTA|S

15ÞGAü,qx

\rcoo

BIBTIOTECAEditorial

Committee Paola Pittalugø Silvia SerreliRoberto

Gambino

.

Attilia

Editors

Project Assistants Monica Johansson Laura Lutzoni

Aims and Scope

urban and Landscape perspectives

is a series which aims at nurturing theoretic refl ection on the

cirv

and rhe reruirory undro.king

ourand

*;üi;;,n"rhods

and techniques for improving our physicaland social landscapes. The main issue in the series is developed around the

projectual dimension, with the objective of visualising both the

cityìnd

trretenitory from a particular viewpoint, which singles out the territorial

¿imension a, the city,s space of communication and negotiation.

The

serieswill

face emerging problems that characterisethe dynamics

of

city development,like

the new,fresl

relations between urban societies and physical space' the right to rhe ciry, urban equiry, rhe projecr for rhe

orrrrlî"iär,

as a means to reveal civitas, signs ofnew sociai cohesiveness, the senseofcontemporary public space and the sustainability of urban development.

concerned

with

advancing theorieson

thecity,

the series resolvesto

welcome articles that feature a plurarismof disciplinari

contributions studyingformal and

informal practices on theproject tor

ttre city

uía

,""ting

conceptuar and operativecategories capabre

of

understanding and facing theproll"-,

iirrr*""i

in

the pro_ found transformations of .ontempoiaryu.Uun ìunor"up"r.

More information about this series at http:fwww.springer.com/s eries/7

906

Nature

Policies

and

Landscape

Policies

Towards

an

Alliance

-à

Editors

Robefto Gambino Attilia Peanot

Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and

Planning (DIST)

Politecnico and Università di Torino Turin

Italy

ISBN978-3-319-05409-4

rSBN978-3_319_05410_0(eBook)DOr I 0. 1 007/97 8_3 _3 19 -05 4 t0 _0

Springer Cham Heidelberg New york Dordrecht London

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955441

O Springer Inremational publishing Switzerland 2015

This work is subject to copyright.lll rights are reserved by the publisher, whether thê whole or part of the material is concemed, specifical[, the rights oi translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations,

recitation' broadcasting, reproduction on microfiläs o.ìn'uny

other physical

ilv,

""ã ìransmission or

information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation,-computer software,

or by similar or dissimilar

methodology now known or hereafter developed.i*"-pt"d

f-.

this legal reservátiooärL u.i"r "^"".pt, in connection with reviews or scholarly analysir orunut"liài rupplied specifically for the purposeof being

entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusiu" ur"-by the iurchaser'of th"

*ã*.

orpti"utionof thitrpublication or parts thereof is permirted only ,nJ". tt

" proni.i*.

;ï;;

ð;p;rîgnt Lu* or tn"Publisher's location, in its current vèrsion, and fermission for use must ui*uyrï"''outuined

from

Springer' Permissions for use may be obtained thråugh Rlghtsl-ink at the C"pv.idr,1 ði"urun"" c"nt"r.

Vìolations are liable to prosecutión under rhe respective òåpyright Law.

Th,",.": of

.generar descriptive names, register"¿ nurn"., trademarks, service marks, etc. in this

pubìication does not implv, even in.the absãnce ofa spåcific statement, t¡ut ru"r,-nì-", are exempt llgT ,hg relevant protective laws and regulations und tlrå."'ro." r."" ro. gån;.ur u.".

"-"'

while the advice and information in tñis book u." u"ii"u"¿ to be true and accurate at the date of

publication, neither the authors nor the edito¡s nor

ttr" fuãtirtl"r can accept any legal responsibility for

any errors or omissions thar may.be made. The publisúer makes

no *ur,ånry,'"^ii".s ãr imptied, with respect to the material contained herein.

Cot,er image: P_o Rjver Regional park from C¡escentino,s bridge, near Turin (Italy). Photo by Ippoliro Ostellino, 2010.

Printed on acid-free paper

Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com)

With great

affiction

we remember

Attilia

Peano

-

former

Full

Professor

in

Town and

Regíonal

Planning

at

the

Politecnico di

Torino

(DISI)

and

CEN

PPN

Director

-

and

theprecious contributions

she has given

during

the course

of her

liþ

in

thefield of

urban

planning,

landscape

planning,

and

nature

and

cultural

heritage

conservation,

being a

protagonist

in

the debate

on

thesetopics

at national

and

international

level.

Her

death (18th

August

2013)

interrupted

her

participútion in

several research

activities

which

are

still on7oin7,

and, in

particular,

in

the

international

research,

that

has been

cqrried

on by the

CED

PPN since 2010,

concerning

the

relationship

between

Landscape

policies

and

Nature

Conservation

policies.

This book

is

the outcome

of this

CED

PPN

research, and we

would

like to

dedicate

it

to

our

friend

and colleague

Attilía,

hoping in

this

way to

remember her

passion

and her

valuable guide

infacing

the subject here

presented.

xvl Abbreviations

Special Conservation Zones

Strategic Environmental Assessment Sustainable Energy Action Plan National Strategy for Biodiversity

Special Protection Areas

Sustainable Urban Metabolism for Europe project The Economics of Ecosvstems and Biodiversity

Travel Cost Method United Nations

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2008)

United Nations Environment Programme

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization European Network of Universities for the Implementation

of

European Landscape ConventionUnited Nations World Tourism Organization U.S. National Park Service

Venture Capital

\ù/orld Business Council for Sustainable Development IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas Vy'orld Database Protected Areas

V/orld Heritage Sites

World Network of Biosphere Reserves

World V/ide Fund for Nature

Zone naturelle d'intérêt écologique, faunistique et floristique/ Inventory of natural zones of ecological, faun and floristic interest Zone de Protection du Patrimoine Architectural, Urbain et PaysagerlZone of Protection for Architectural, Urban and Landscape Patrimony

Contents

Introduction:

Reasoning on Parks and Landscapes Roberto GambinoPart

I

New Paradigms2

Nature

Conservation and Landscapes: AnIntroduction

to the IssuesAdrian PhilliPs

3

Bringing

TogetherNature

andCulture: Integrating

a Landscape a,pproaõninProtected

Areas Policy and PracticeJessica Brown

4

The Place of Protected Areasin

the European Landscape:A

EUROPARC Federation Perspective'

' '

'Carol Ritchie

5

From Park-Centric

Conservation to Whole-Landscape Conservationin

the USA'

'Paul

M.

BraY6

Ecological Functions,Biodiversity

and LandscapeConservation...

'Gioia Gibelli and Riccardo Santolini

7

^Territorial

Contradiction

" "

Riccardo Guarino, P attizia Menegoni, Sandro Pignatti'

and Sirnone Tulumello

8

Legal Frameworksfor Nature

Conservation and Landscape Protection Carlo Desideri SCZs SEA SEAP SNB SPAs SUME TEEB TCM UN UNDRIP UNEP UNESCO UNISCAPE UNWTO USNPS VC WBCSD WCPA WDPA WHS WNBR WV/F ZNIEFF ZPPAUPI

t

25 JJ 43 51 59 69 1'7 xvllxix 191 201 207 2t'7 223 233 243 251 261 269 27"1 283 85 93 18

t9

20 XVIII9

Beyond Gardens and Nature Reserves: Contemporaneous LandscapesJennifer Buyck and Teodoro C. Vales

10

From

theTerritory

to the Landscape: The Image as a Toolfor

DiscoveryClaude Raffestin

Part

II

From

Nature to Landscape and Back11,

Biosphere Reserves and Protected Areas:A

Liaison Dangereuseor

aMutually

BeneficialRelationship?.

. . . .Giorgio Andrian and Massimo Tufano

12

Connecting theAlpine

Protected Areasin

a Wide EcologicalInfrastructure: Opportunities from

a Legal Point of View. . . .

.Paolo Angelini

13

Protected Areas,Natura

2000 Sites and Landscape: Divergent Policies on Converging ValuesBernardino Romano and Francesco

Zullo

14

Regional Planningfor Linking

Parks and Landscape: Innovative Issues .Angioletta Voghera

15

Landscape and ProtectedNatural

Areas: Laws and Policiesin Italy

Renzo Moschini

16

Evolution

of Concepts and Toolsfor

Landscape Protection andNature Conservation.

. . .Mariolina Besio

t7

Nature Conservationin

theUrban

LandscapePlanning.

. . . .Luigi

La RicciaProtection of

Peri-urban Agricultural

Landscapes: Vegas and Deltasin

AndalucíaRocío Pérez-Campaña and Luis Miguel Valenzuela-Montes

Linking

Landscape Protection andNature

Conservation: Switzerland's Experiencewith

ProtectedMire

Landscapes.

.Thomas Hammer and Marion Leng

Putting

the Park-Landscape Alliance to the Test: Protected Landscapes as aProving Ground

Emma Salizzoni Contents 105 119 127 131

t45

149 157 165 173 181 Contents2l

Participatory

Planning Toolsfor

Ecotourismin

Protected Areas of Morocco andTunisia: A First

ExperienceCarla Danelutti, Ángeles De Andrés Caramés, Concha Olmeda, and Almudena De Velasco Menéndez

22

Tourism

and ConserYationin

Protected Areas:An

Economic PerspectiveMassimiliano Coda Zabetta

23

Participation

and Regional Governance.A Crucial

Research Perspective on Protected Areas Policiesin Austria

and SwitzerlandNorbert Vy'eixlbaumer, Dominik Siegrist, Ingo Mose, and Thomas Hammer

24

Old

and New Conservation Strategies:From

Parks toLand

StewardshipFederica Barbera, Marzio Marzorati, and Antonio Nicoletti

25

Between Nature and Landscape: The Role ofCommunity

Towards an Active Conservationin

Protected Areas Rita Salvatore26

TheContractual Communities' Contribution to Cultural

andNatural

ResourceManagement.

. . . .Grazia Brunetta

27

The Concept ofLimits in

Landscape Planning and Design.

'

.Francesca Mazzino

28

Landscape and Ecosystem Approach to BiodiversityConservation....

Franco

Feroni,

Monica Foglia, and GiulioCioffi

29

Biodiversity

and Landscape Policies: Towards anIntegration?

A

European OverviewBianca Maria Seardo

30

From P-Arks

to P-HubsPaolo Pigliacelli and Corrado

Teofili

31

The experienceofthe

European Landscape Observatoryof

Arco Latino

Domenico Nicoletti

32

Crosscutting Issuesin Treating

the Fragmentationof

Ecosystems and Landscapes. . .XX

33

Multi-scalar

andInter-sectorial

Strategiesfor Environment

and LandscapePaolo Castelnovi

34

Urban Landscapes and Naturein

Planning and Spatial StrategiesMassimo Sargolini

35

Integrated Planningfor

Landscape Protection andBiodiversity

Conservation....

Alessandro Tosini

36

An

Assessment of the Role of Protected Landscapesin

ConservingBiodiversity in

EuropeNigel Dudley and Sue Stolton

37

Lessons Learnedfrom

U.S. Experiencewith

Regional Landscape Governance:Implications for

Conservation and Protected Areas .Daniel Laven, Nora J. Mitchell, Jennifer Jewiss, and Brenda Barrett

38

Park,

Perception and the WebCaterina Franchini and Elena Greco

39

Landscape Scenic Values: Protection and Managementfrom

a Spatial-Planning Perspective .Claudia Cassatella

40

EuropeanCultural

Routes: A Toolfor

Landscape Enhancement Silvia Beltramo4l

EconomicValuation

of Landscape at Risk:A

Critical

Review Marina Bravi and Emanuela Gasca42

Towards anIntegrated

Economic Assessment of Landscapei'r

Marta Bottero, Valentina Ferretti, and Giulio Mondini43

Protected Areas:Opportunities for

Decentralized FinancialMechanisms?....

Luca Cetara

Part

III

Experiences and Practices44

The Langhe Landscape ChangesDanilo Godone, Matteo Garbarino, Emanuele Sibona, Gabriele Garnero, and Franco Godone

45

Cultural

Landscape and RoyalHistorical

Systemin

Piedmont RegionI|¡4aÅaGrazia Vinardi

Contents

46

Regional Management Tools at Local Level: The Po andOrba

RegionalRiver Park

Franca Deambrogio and Dario Zocco

47

The Landscapesofthe

Portofino Nature RegionalPark

'

. .

. ..

.Franca Balletti and Silvia SoPPa

48

TheAlpi

Liguri

Nature RegionalPark.

.Adriana Ghersi

49

Towards thePark

of FlorenceHills

. .Gabriele Corsani and Emanuela

Morelli

50

Protected Area Planning,Institution

and Managementin Apulia

RegionNicola

Martinelli

and Marianna Simone51

TheEnvironmental

Issuein Sicity.

Ignazia Pinzello52

Revitalising theHistorical

Landscapez Tlr,e Grøngein

Southern EuropeClaudia Matoda

53

Nature, Landscape and Energy: The EnergyMasterplan of

Emilia-Romagna Po Delta RegionalPark

Anna Natali and Francesco Silvestri

54

How to Manage Conflicts Between Resources'Exploitation

andIdentity

ValuesMariavaleria

Mininni

55

Planning and Managementin

the Otranto-LeucaNature Park.

Annalisa Calcagno Maniglio and Marianna Simone56

A

Regional Planningfor

Protected Areas of Sustainable Developmentin

theMercantour

andMaritime

Alps Marco Valle and Maria Giovanna DongiovanniErratum to

Chapter 23:Participation

and Regional Governance.A Crucial

Research Perspective on Protected Areas Policiesin Austria

andSwitzerland.

. .Index.

Contents xxi 409 415 423 43r 439 441 455 461 469 419 487 E1 493 291 299 301 315 323 33134t

353 361 311 381 393 401Contributors

L{

Giorgio

Andrian

Formerly LINESCO office, Padua,ItalyPaolo

Angelini

Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea, Rome, ItalyFranca

Balletti

Departmentof

Sciencesfor

Architecture, Polytechnic School,University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

Federica

Barbera

Protected Areas Department, Legambiente Onlus, Rome, Italy BrendaBarrett

Living

Landscape Observer, Harrisburg, PA' USASilvia Beltramo

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyMariolina Besio

Deparlmentof

Sciencesfor

Architecture, Polytechnic School,University of Genoa, Genoa, ItalY

Sergio

Bongiovanni

GIS Consultant, Turin, ItalyMarta

Bottero

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin,Italy

Marina

Bravi

Interuniversity Depaftmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyPaul

M.

Bray

Albany University (Retired), Albany,NY'

USAJessica

Brown

New England Biolabs Foundation, Ipswich,MA'

USA IUCN-WCPA Specialist Group on Protected Landscapes, Ipswich,MA'

USAGrazia

Brunetta

Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin,Italy

Jennifer Buyck

Institute d'Urbanisme de Grenoble, Grenoble, FranceClaudia

Cassatella Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, Italyxxlv Contributors

Paolo

Castelnovi

ex-Politecnico di Torino, Turin, ItalyLuca Cetara

European Academy of Bolzano, Representing Office, Rome, ItalyGiulio

Cioffi

CREDIA WWF, Fiuminata,MC,Italy

Gabriele

Corsani

Department of Architecture, University of Florence, Florence,Italy

Carla Danelutti IUCN

Center for Mediterranean Cooperafion, Málaga, SpainÁngeles

De

Andrés

Caramés ECOTONO, Equipo Consultor Turismo

y Desanollo, S.L., Madrid, SpainAlmudena

De

VelascoMenéndez

ECOTONO,Equipo

Consultor Turismo y Desanollo, S.L., Madrid, SpainFranca

Deambrogio

Sportello INFOFIUME, Parco Fluviale del Po e dell'Orba, Casale Monferrato,Italy

Carlo Desideri

Institutefor

the Study of Regionalism Federalism and Self-Gov-ernment, ISSiRFA-CNR, Rome, ItalyMaria

GiovannaDongiovanni

SiTI Istituto Superiore sui Sistemi Territoriali per I'Innovazione, Turin, ItalyNigel Dudley

Schoolof

Geography, Planning and Environmental Management,University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

IUCN

World Commission on Protected Areas and Equilibrium Research, Bristol,UK

Valeria

Ferretti

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino,Turin,Italy

Franco

Ferroni

Biodiversity, Protected Areas and Agricultural Policies, WWF Italy, Rome,ItalyVTonica

Foglia INEA

Research Grant atAgricultural

SocietyLa

Quercia della Memoria, CREDIA}V\

/F, San Ginesio,MC,Italy

Caterina Franchini

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyRoberto

Gambino

Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyMatteo Garbarino

Departmentof

D3A,

Università Politecnicadelle

Marche, Ancona, ItalyGabriele

Garnero

Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyContributors

Emanuela Gasca Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and

ftunning

(DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino and SiTI Istituto Superiore sui Sistemi Territoriali per l'Innovazione, Turin, Italy 'Adriana Ghersi

Departmentof

Sciencesfor

Architecture, Polytechnic School,University of Genoa, Genoa, ItalY

Gioia

Gibelli

SIEP-IALE Italian society of Landscape Ecology,Milan,

Italy FrancoGodone

CNR-

IRPI, Torino, TO, ItalyDanilo Godone

DepartmentDISAFA

and NatRisk, Universitàdegli Studi

di Torino, Grugliasco, TO, ItalYElena Greco

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional andurban

Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyRiccardo Guarino

Diparlimento STEBICEF, Universitàdi

Palermo, Palermo, ItalyThomas

Hammer

centre for Development and EnvironmentcDE,

universityof

Bern/Switzerland, Bern, SwitzerlandJennifer

Jewiss

Department of Leadership and Developmental sciences, univer-sity of Vermont, Burlington,VT'

USALuigi La Riccia

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyDaniel

Laven

Department of Tourism Studi.es and GeographyÆuropean Tourism Research Institute,Mid

Sweden University, Ostersund, SwedenMarion

Leng

Centrefor

Development and EnvironmentcDE,

University of

Bern/Switzerland, Bern, SwitzerlandAnnalisa Calcagno

Maniglio

Department of Sciences for Architecture, Polytech-nic School, University of Genoa, Genoa,Italy

Nicola

Martinelti

A6 Lama San Giorgio Protected Area Plan, Bari, ItalyMarzio

Marzorati

ProjectLand

stewardship, Legambiente Lombardy,Milan'

ItalyClaudia

Matoda

lnteruniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyFrancesca Mazzino

Departmentof

Sciencesfor

Architecture,

Polytechnic School, University of Genoa, Genoa, ItalyPatrizia Menegoni

ENEA, Unità Tecnica AGRI-ECO, Rome,ItalyMaria Valeria

Mininni

DiCEM

UNIBAS, Potenza,Italyxxvl Contributors

Nora

Mitchell

Rubenstein Schoolof

Environment and Natural Resources, Uni-versity of Vermont, Burlington,VT,

USAGiulio

Mondini

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyEmanuela

Morelli

Department of Architecture, University of Florence, Florence,llaly

Renzo

Moschini

Gruppo San Rossore, San Rossore Park, Pisa, ItalyIngo Mose ZENARiO

-

Centerfor

Sustainable Spatial Development, Applied Geography and Environmental Planning Research Group,Carl von

OssietzkyUniversity Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

Anna

Natali

eco&eco, Economia ed Ecologia, Ltd, Bologna, ItalyGabriella

Negrini

Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyDomenico

Nicoletti

European Landscape Observatoryof

Arco Latino,

Padula,Italy

Antonio Nicoletti

Protected Areas Deparlment, Legambiente, Rome, Italy ConchaOlmeda ATECMA,

Villalba, SpainGabriele

Paolinelli

Department of Architecture, University of Florence, Florence,Italy

Rocío

Perez-CampañaEnvironmental Planning Laboratory (LABPLAM),

Departmentof

Urbanism and Spatial Planning, Universityof

Granada, Granada, SpainAdrian

Phillips

UK Countryside Commission, IUCN's World Commission, Chel-tenham,UK

þolo

Pigliacelli

Federparchi-EuroparcItalia (Italian

Federationof

Parks andNatural Reserves), Rome,

Italy

Sandro

Pignatti

Forum Plinianum, International Association for Biodiversity and System Ecology, Rome,Italy

Ignazia

Pinzello

University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy ClaudeRaffestin

Université de Genève, Genève, SwitzerlandCarol Ritchie

EUROPARC Federation, Regensburg, Germany RosannaRizzi

DiCEM

UNIBAS, Potenza,ItalyBernardino Romano

University ofL'Aquila, L'Aquila,

ItalyContributors

xxviiEmma

salizzoni

Interuniversity Department of Regional and urban Studies and Flunning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin' ItalyRita Salvatore

University of Teramo, Teramo, ItalyRiccardo

santolini

Departmentof

Earth,

Life

and

Environmental ScienceslpiSf"Ve),

CarloBo Uìiversity of Urbino,

scientific'campus"Enrico

Mattei",Urbino, ItalY

Massimo

sargotini

School of Architecture and Design,university

of camerino, Camerino, ItalyBianca

M. Seardo

Interuniversity Deparfment of Regional and urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino,Turin'

ItalyEmanuele

Sibona

Department of DISAFA and NatRisk, Università degli Studi di Torino, Grugliasco, TO, ItalYDominik Siegrist

Institutefor

Landscape andopen

space, HSR Universityof

Applied Sciences, Rapperswil, SwitzerlandFrancesco

Silvestri

eco&eco, Economia ed Ecologia, Ltd.,Bologna,Italy

Marianna Simone

MasterIUAV,

Venice, Italysilvia Soppa

Departmentof

sciencesfor

Architecture, Polytechnic school, uni-versity of Genoa, Genoa, ItalYsue

stolton

IUCN V/orld commission

on

Protected Areasand

Equilibrium Research, Bristol.UK

corrado Teofili

Federparchi-EuroparcItalia (Italian

Federationof

Parks and Natural Reserves), Rome, ItalYAlessandro

Tosini

Politecnico di Torino, Spinetta Marengo'AL'

ItalyMassimo

Tufano

The Regional Agency for Protected Areas in Lazio, Rome, Italysimone

Tulumello

Instituto de ciências Sociais, universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, PortugalLuisMiguelValenzuela-MontesEnvironmentalPlanningLaboratory

(LABPLAM),

Deparrmentof

urbanism and Spatial Planning,university of

Gra-nada, GraGra-nada, SPainTeodoro

c. vales

Institute d'urbanisme de Grenoble, Grenoble, FranceMarco

Valle

SiTI Istituto

Superioresui

SistemiTerritoriali

per I'Innovazione, Turin, ItalyMaria

Graziavinardi

Interuniversity Department of Regional and urban studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and università di Torino, Turin, , Italyxxvlll Contributors

Angioletta Voghera

Interuniversity Departmentof

Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and Università di Torino, Turin, ItalyNorbert

Weixlbaumer

Departmentof

Geography and Regional Research, Uni-versity of Vienna, Vienna, AustriaMassimiliano

CodaZabetta SiTI

Istituto Superiore sui SistemiTerritoriali

per I'Innovazione, Turin, ItalyDario Zocco

Parco Fluviale del Po e dell'Orba, Casale Monferrato, Italy FrancescoZullo

University ofL'Aquila, L'Aquila,

ItalyChapter

7

A

Territorial

Contradiction

Riccardo

Guarino, Patrizia

Menegoni, SandroPignatti'

and SimoneTulumello

Abstract

Spatial planning and environmental restoration are essential corollaries to the management of protected natural areas; however, without a sound awarenessof

the

evolutionary consistencyof

biocoenoses,the

harmonious integration between human activities and ecosystem preservation remainsan

unattainable utopia. The theorisation of a balanced welfare, inspired by the universal tendencyof ecosystems to reach a steady state, has to go along with the defection from any economic greed.

Keywords

Parks.

Protected areas.

Sustainability.

Spatial planning.

Human behaviourThe ever-increasing importance given to nature conservation

in

Europein

recent decades has brought to the setting up of a system of protected natural areas extendedto 18 Vo of the EU territory, mostly thanks to the transposition and implementation of Directives 7 g I 409 IEF;C and 92143 EEC.I

Frequently, European protected areas have

limited

extension and are close to densely populated areas characterisedby

pervasive urbanisation and infrastruc-tures. What is under protection in Europe is not a primordial nature, of which veryI

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/index-en'htm, http://natura2000.eea.europa.eu/ R. Cuarino

(X)

Diparlimento STEBICEF, Università di Palermo, Via Archirafi 38I,90123 Palermo, Italy

e-mail: guarinotro@hotmail.com

P. Menegoni

ENEA, Unità Tecnica AGRI-ECO, Via Anguillarese 301, 00123 Rome, Italy e-mail: patrizia.menegoni@casaccia.enea.it

S. Pignatti

Forum Plinianum, International Association for Biodiversity and System Ecology,

Via Lavinio 22,Rome 00183, Italy

e-mail: sandro.pignatti@ gmail.com

S. Tulumello

Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa, Avenida Professor Aníbal Bettencourt 9, Lisboa 1600-189, Portugal

e-mail: simone.tulumello@ics.ul.pt

O Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

R. Gambino, A. Peano (eds.), Nature Policies and Landscape Policies, Urban and Landscape Perspectives I 8, DOI l0.lÛ07 l9'7 8-3-3 19-054 10-0-7

7

A Territorial Contradiction 7lmainly accommodate the requests of those who look at nature protection primarily in an economic-productive way, demanding guarantees, beneflts and services.

7.1

Protected

Areas

or

Theme Parks?

As we have seen, the protection

of

naturein

Europeis

inextricably linked to the preservation of surviving fragments of our collective past, an ancestry from which we freed thanks to the recent technological and socio-economic development.Like

the historical city centres, which are protected and restored to last over time, even the protected areas are often subject to maintenance and conservative restoration. Significant differences exist between pre- and post-industrial cities, based on the juxtaposition city/nature and on the conceptofthe

urbanised area itself. In the past, cities were a closed entity opposed to the res nullius of the outertenitory

(Salzano 1998). When cities were surrounded by walls, the unknown, the unknowable and the unpredictable were kept outside.In

more recent times, urban expansion and population growth have gradually bluned thecity

boundaries,until, in

the post-industrial urban sprawl, the res nullius has çome to penetrate thecity

itself, along with a functional complexity that has made us accustomed to use, but not to know, and much less to control, many items and spaces of our daily lives.While in the past we were frightened by what was outside the city, currently, it is the specialisation

-

and functional segregation-

of

the modern urban space that intimidate us(Ellin

1996): a progressive occupationof

physical space, unable to build thecity.

Among the areas that-

at leastin

appearance-

arestill

relatively immune to such contamination, there are the natural spaces, which can be seen as abelated acceptance

of

the devastation wrought by the territorialcity:

thewildlife

reserves of modern Europe, however great, can be well intetpreted as recreational appendages of urban spaces. They are used by most of the people to relax, to do alittle

exercise, tovisit

unusual places, to buy local products and to imagine howit

v/as in the past.Oddly, the establishment ofprotected natural areas, which occufred over the past

two

decades at an unprecedented rate,is

contemporaryto

the needof

creating 'newly ufban' spaces. Think of the malls, entities that assert themselves as public venues similar to cities but without their flaws: safe, reassuring andwith

an easily recognisable spatial and functional organisation. Consider the reactionofthe

urban centres to the processes of gentrification that replicate the characteristics of a mall through a 'renewal' based on urban marketing and surveillance systems.Sometimes, these spaces are

built from

scratch:City

Walk is a pedestrian and commercial areabuilt in

the 1990sin

Los Angeles,'an

urban area painstakingly reproduced (evento

the extremeof

wedging candy wrappersinto

the pavement [. . .]) and idealized becauseit

wants to be the best essence of thecity,

completely free from the violenceofLos

Angeles' (Codeluppi 2000, our translation)'.In

other cases, are the historical centresto

be modified accordingto

profit-oriented models. Thus, manyItalian

towns have seen Çlearedtheir

social fabric,R. Guarino et al.

10

few

traces remain, but the still-surviving elementsof

a traditional cultural land-scape, richin

natural features of which tbe establishment of protected areastry

to salvage the most significant relicts'Thle new EU policies consider natural afeas as a resource to be managed through measures and initiatives aiming not only to preserve biodiversity but also to meet

the

demandsof

local

people,in

orderto

ensure the best compromise between ecosystemintegrity

unà,å"io-""onomic

development (Petermann and Ssymank2007).Thenewmanagerialparadigmisthereforebasedonacollaborative

appráach, agreedand

Jharedby

local

communitiesalong

with

all

the

other stakeholders.unfortunately, it is very difficult to find an optimal balance in the expectations

of

those who propór", who use and who manage protected areas' The risk is to invest fesources in protecting and perpetuating what we like most, making a sort of 'large-scale gardenìng,_

gardeningìt

the scaleof

landscapes-

often at oddswith

all naturaîp.o""ri=",

undoynuÃi"s,

such as the shrub encroachmentin

abandoned .angeland.,afrequentlyobservednaturalprocessthroughoutEurope'thatiscaus-ing the rarefaction of orchids very dear to man'"As

often happens,

it

is

necesiaryto

establish priorities andto

make choices. Nonetheless, about biodiversity, real and perceived, aswell

as about advisability;;

;ff;"tiìÉness of

actions taken to protectit,

there is a great variety of opinionsthatmakesdifficulttheimplementationofprogramsandtheevaluationofresults,

also dueto

some confusiãnof

roles between ecologists and planners (Guarino et al. 201l).

Knowledge about vegetation, ecoregions and ecosystem relationships

is

an essential elementin

plarining and land management (Pignatti 1994, 1995: Blasi and paolella 1995;Biondi

iOOl).lt

is

necessaryto

understand where and, more imporlantly, how much it costs (in terms of 'environmental sustainability') to invest"nårgy and resources

to counter the natural dynamics'

It-is

not

always given due imporlanceto this

knowledge base, andit

oftenhappens that,

in

choosing the management strategies, the impact on employmentof

the ,interventionist' Jpproacnis

prefened without considering that nature,in

order to remain ,uctr, stroui¿ not be excessively subject to the deterministic control by man.However,outsideprotectedareas,weedingofroadsidesandcultivationsis

practiced without hesiiation; the continuity between trophic ecosystems and agro-syrtems is compromised in order to promote all that is functional to the production systemin

the global

market.Not

eventhe

management and conservationof

protected areas escapethe

marketrules

andrequire' thus' the availability of

resources to invest. This brings usto

the obvious contradiction thatto

safeguard very limited porlions of the planet, the remaining areas are exploited withincreas-ing intensity (Guarino and Pignatti 2010)'

-As

previously mentioned, European protected areas have

a

strongly 'urban' character; this stimulates a constant search for innovative solutions in themanage-mentofsuchcomplexareas.Thewilltoproteçtnotmediatedbyathoroughand

dispassionate understanding of ecosystems can easily run into errors or end up to7

A Territorial Contradiction 73reserve

to

the framea

rather superficial aesthetic/contemplative evaluation andassess their experience mainly on the quality

of

services offered by theadministra-tors. This new realm is a city of simulations; television city and the city as a theme park (Sorkin 1992).

The 'sanctuary'

(in

Russian: zapovednik) is an exception to this general trend and, as a natural environment protected erga omnes, should be considered a positive example, although elitist and expensive, because it requires a difficult management (control of herbivores, biodiversity monitoring, etc.), which often clashes with the reluctance ofadministrators and public opinion to accept the non-usability ofareas that, to remain such, require maintenance patrolling and monitoring costs (Sessions 1995; Boreiko et al. 2013).7.2

Pandemic

Park

Foundations

So many parks have been recently founded

all

over the world! Some example are (Google search:'park'

2013): national, regional, pelagic,river,

mountain, valley,wildlife, urban, public, cultural, school, college, music, literaty, research,

technologi-cal, archaeological, Jurassic, safari, amusement, recreational, commercial, private, pocket, wind, solar, caf and even sushi park! Despite their diverse nature, all these areas share

an implicit 'need'

for

protection, fence, boundaryand

sectoriality. Accordingto Diez

(1353), theterm 'park'

derivesfrom

theLatin

word patcere (i.e. to impede): the place wherewild

animals of every kind are locked up, in order to take delight in hunting at any time. According to others, the tetm derives from the ancient Germaîwordberk(tn (modem: bergen): to cover, to save and to defend. In fact, the word perku akeady existed in Akkadian, with the meaning of defence, frontier and barrage.In

connectionwith

these conceptsis

theroot 'pork' (in

Latin: porcus),originally indicating the enclosure, the coulyard where the domestic pig (in Latin: .røJ) was kept and later designating the beast itself. The porcus stands clearly out from aper (i.e. the wild boar), which is the same beast but lives in open spaces, in freedom.

Our history

of

supporters or detractorsof

parksis

largely based on the meta-phorical contrast between a pigliving

in a closed, fenced and protected place and awild boar routing in the forest without supervision. The pig, symbol of the rational

use of animal breeding, has originated from the clever domestication of a wild boar.

Similarly, the park, a protected place, is the outcome of a metaphorical

domestica-tion

of

Dante's forest 'savage, rough, and stern/whichin

the very thought renews the fear'.2 The pristine nature, reduced to a paltry fragments, does not more .induce awe but inspires a pfotective instinct.In

the modern city, men undergo an inexo-rable fascination towards nature, and the greater the fascination, the stronger the processof

alienation againstit.

The Italian writer Calvino (1963) has masterfully represented such fascination in the short stories of Marcovaldo:2

http ://www.worldofdante.org R. Guarino et al.

72

.¿

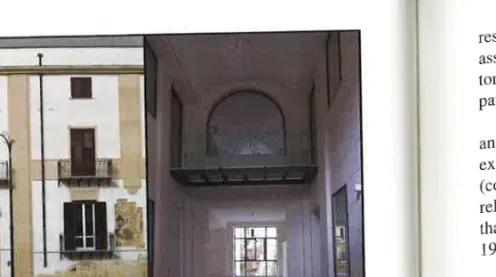

Fig.

7.1

Palazzo del Gran Cancelliere, Palermoreplaced by a space tailored to tourism requirements. connected to these processes

is the falsification

of

historical spaces, pushed towards aesthetic stereotypes con-sistent with their commercial role.It

is an example-

perhaps unintended-

the PPE (detailed executive plan) for the historic centre of Palermo releasedin

1989, which, in reaction to some types of urban speculation, requires the accurate reconstructionof entire blocks and is populating tlie city of architectures that are historically fake like the Palace of the crand chancellor in the homonymous square (Fig' 7'1), which seems a restoration but

it

is an almost entirely new building'Even more complex

is

the

situationof

Venice: thecity

wasnot

developed'against'

the

surrounding environment,which

for

a

millennium has

been maintained asa

necessary enclosurefor the city,

and providedfood

resources(fisheries)andsafetyfromexternalattacks.Betweenthecityandthelagoonhas

iemained an interactive relationship(ust

think of the importance of tides) that man has changed over the centuries wiitr ttre diverting of rivers flowing into the lagoon and the consolidation of the lidos. This has allowed the development of Venice as apolitical

and commercial centre, the developmentof

thefirst

industrial complexithe

Arsenal) and a thriving culture. Over the past two centuries, thecity

has lostthesefeaturesandin,"""-nty"u,,muchofthepopulationhasmigratedtothe

mainland, while the lagoon has been progressively depleted by erosion and pollu-tion. In this way, the oid balance between the town and the lagoon is lost: both are now (for various reasons) protected areas, but the cultural and commercial meaning

of the first and the natural one of the second are being upset'

The metaphor we have

built

seems to reveal a sad fate: protected areas, whethertheyarenaturalparks,historicalcentresorquaintvillages,arepushed_unknow.

ingiy?-

towardsa 'productive'

function; the objectto

be protected becomes a valuable frame within which to develop employment and investment, tourism and territorial marketing. In this context,viiitors

become users/consumers: they usuallyI

7

A Teritorial Contradiction 75To overcome this contradiction,

it

is necessary to design new logistic networks, integrated on a local scale. 'We urgently need a planning that links the man to histerritory and not the restorer to his object. These aims are achievable only

if

we are able to put every single man in a new position of awai'eness and responsibility.The spaces to be (re)planned

will

no longer be, as they werein

pre-industrial dmes, the resultof

unconscious, choral, attempts to best use land, resources and local materials. Theywill

be, instead, the result of a planning well integrated to the social context and to the strategic sharing of ideals and models altemative to thoseof

consumerismand

of

the global

market.So, not the retum

to

an

edenic,pre-industrial

world, but

the evolutionfrom a world

centralisedby the

global economy towards a world where global technologies and knowledgewill

be used to boost local economies, to emphasise the local diversities and to encourage the decongestion of the trade routes that underpin the current human habits, linked to products and services standardisedon a

national and, increasingly, continental scale. To do this, the planner cannot ignore the political valueof

acting on behalfof

an ethical necessity, imposedby

the not sustainable environmental and social costs of current consumption pattems.Under this perspective, even the 'sanctuary' takes on a new meaning: it does not only matter for the rarity or the particular aspect of species and vegetation layers but also

for its

value as an ethical model,a

physical space where an efficient and optimal balance is established between the external factors (climate and soil) and the local communities (bacteria, plants, animals), a living example of self-organised order, able to maintain and preservein

a steady stateall

the ecosystem functions which are needed also by the human species. The tools to convey this message are the virtual channelsof

the web and the mass media that the new planners should leam to usewith skill

at least equal to thatof

those who use them as catalystsof

global consumption patterns. The physical elements of the new landscapeswill

bemuch stronger the greater the number

of

people who believesin

and supports are-localisation of consumption habits and particularly of those related to the human

nutrition. The new landscapes

will

be more durable the greater the numberof

peoplewho

will

use their freetime to

set up the networkof

collaboration and proactive interaction thatis

functionalto

the development and maintenanceof

aparticipated, unmediated and

alive cultural

landscape (Guarino and Menegoni 2010).If

mostof

uswill

keepon

spendingour free time

in

malls,

spas and television, land protection in an integrated and systemic view risks being perceived asyet

another actionto

share passively,to be

supportedby providing a

small contribution money, without changing our habits too.In

this way, wewill

not go very far.The new way of planning should be social and tenitorial at the same time:

if

the aim is to promote, not justfor

aesthetic reasons, more sustainable landscapes, we should be able to recognisein

the parsimony of our ancestors the precursor of themoral and personal commitment

of

modern innovators.A

parsimonyno

longer imposed, as in the past, by poverty and limited resources, but by the awarenessof

how gross-

and inefficient from environmental and thermodynamic standpoint-

is74 R. Guarino et al.

The Marcovaldo's love for nature can only be felt by a city man (.. .) Dad {he children

said- are the cows like trams? Do they make stops? where is the terminus of the cows? (Calvino 1963, our translation).

7.3

Towards

a

Participated

Landscape

Beauty and harmony

of

nature, together with its effrciency, have inspired mostof

speculative thinking and art forms that have marked the human history. Human nature andits

technical andcultural

expressionsmirror the

complexityof

the phenomenonof

life.

Throughthe

centuries,rural

communities have managediheir

environment and farmed the landin

their own natural way, creating a rich diversityof

landscapes, choral representation of historical identityof

the territoryand cultural human heritage (Fig. 1 .2). We now tend to recognise

in

that modelof

development the precursorof

'sustainability'.In the past, even the human welfare was associated with a balanced and durable state of satisfaction, inspired to the ecological concept of climax'

'lhe inapa(ía of

the Greeks and the otium of the Latins are expressions of a pleasure to be enjoyed

noting wisely

the

satisfactionnot

of

one'sown

desires,but

of

his own

needs.Modern man has redefined the perception

of

welfare and simplifiedits

semantic breadth:all

parameters are set on the purchasing powerof

goods, products and services that in many cases are necessary just because they are depicted as such by the new global socio-economic order. Paradigm for this change is the gradual shift from the theorisationof

a balanced welfare, inspired by the universal tendencyof

ecosystems to reach a steady state, towards an incremental and bulimic welfare, no longer inspired by nature, but fuelled by its devastation. In doing so, the speculative power of analytical thinking has been equally simplified and increasingly bound to the binary logic of cost/benefit analyses (Menegoni et al. 2011). Cheap and perva-sive information services broadcast this new concept of welfare, emphasising in the popular imagination the gap between the 'polluted' places of our everydaylife

and the'intact'

places of protected areas.R. Guarino et al

to consume products whose packaging and transpotl costs outweigh the production costs (Patel 2009).

The challenge goes

far

beyond theability to

redesign theteritory:

it

liesin

making desirable a sober lifesiyte, aware of the environmental consequences of all oul.uJionr;

it

liesin

making"hoi""t

oriented to the re-territorialisation,i'e'

the downsizing and the localisatiãn of production districts, in close proximity to trading postsand;isposal

places; andiilies

in

favouring the most direct relationshipbetween production and consumption'

'16

References

Biondi E (2007) Paesaggio, biodiversità e sviluppo sostenibile: il case delle praterie appenniniche'

In: Finco A (ed) Ambiente, Paesaggio e Biodiversità nelle politiche di sviluppo rurale' Aracne' Rome

BlasiC,PaolellaA(1995)Progettazioneambientale.LaNuovaltaliaScientifica,Rome Boreiko

v,

parnikoza I, nurko"vskiy A (2013) Absolute "zapovednost"'- a concept of wildlifeprotection for the 2lst century. Bull Eur Grassland Group l9-20:25-30

Catvino I (1963) Marcovaldo' ovvero Le stagioni in città' Einaudi' Turin

Codeluppi V (2000) Lo spettacolo della mercã. I luoghi del consumo dai passages a Disney World' Bompiani, Milan

niezcr(tss¡)EtymologischesWörterbuchderromanischenSprachen'Scheeler,Bonn Ellin N (1996) Postmodem urbanism' Blackwell, Cambridge

Guarino'R, Menegoni P (2010) Paesaggi marginali e paesaggi mediati' Ecosc 3:32-33

Guarino R, pignani S (zotOj óiversiiaã and ùiodiveriity: the roots of a 21st century myth' Rend

Lincei

-

Sci Fis Nat 20(4):351-357Guarino R, Bazan G, vrariiá P (2011) La sindrome delle aree protette. In: Pignatti S (ed) Aree Protette e Ricerca Scientiflca. ETS, Pisa, pp 143-158

Menegoni p, Guarino R, pignarti s (2011) Èõorromia, ecologia e tecnologia: riflessioni su una "oiluivenra difficile. Natiralmente

-

Fatti e Trame delle Sci 24(2):8-12

patel R (2009) The value of nothing: how to reshape market society and redefrne democracy'

picador, London. Italian editioñ patel

R

(2010)il

valore delle cosee

le illusioni del capitalismo (trans. Oliveri A). Feltrinelli, Milanpetermann J, Ssymank

A

(2OOil Natura 2000 and its implications for th9 ¡rglection of plantsyntaxa in Germany, vøith u case-study on grasslands' Ann Bot (Rome) 7:5-18 Pignãtti S (1994) Ecologia del paesaggio' UTET' T1r1n

rilnutti s irsss j L'ecoùstema urbanãI Accad. Naz. Lincei XXI Semin. Evoluz. Biol. pp 13'l-16'l

Sizano g if SSSi Fondamenti di urbanistica' Latetza, Rome-Bari

Sessions G (1995) Deep ecology for the 2lst century' Shambhala' Boston

SorkinM(ed)(1992)variationsonaThemePark:theNewAmericanCityandtheendofthe public space. Hill and Wang, New York