CUIDADO É FUNDAMENTAL

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESTADO DO RIO DE JANEIRO . ESCOLA DE ENFERMAGEM ALFREDO PINTO

RESEARCH DOI: 10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v12.8310

DOI: 10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v12.8310 | Campos RKGG, Vieira RC, Maniva SJFC et al. | Clinical management of suspected chikungunya...

CUIDADO É FUNDAMENTAL

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERALDO ESTADODO RIODE JANEIRO. ESCOLADE ENFERMAGEM ALFREDO PINTO

R E V I S T A O N L I N E D E P E S Q U I S A

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF SUSPECTED CHIKUNGUNYA FEVER:

HEALTH PROFESSIONALS KNOWLEDGE OF BASIC ATTENTION

Manejo clínico da suspeita de febre de chikungunya: conhecimento de

profissionais de saúde da atenção básica

Manejo clínico de la fiebre de chikungunya sospecha: conocimiento de

profesionales de salud de atención básica

Regina Kelly Guimarães Gomes Campos1, Ruama Carneiro Vieira2, Samia Jardelle Freitas Costa Maniva3,

Isabel Cristina Oliveira de Morais4

How to cite this article:

Campos RKGG, Vieira RC, Maniva SJFC, Morais ICO. Manejo clínico da suspeita de febre de chikungunya: conhecimento de profissionais de saúde da atenção básica. Rev Fun Care Online. 2020 jan/dez; 12:247-252. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v12.8310.

ABSTRACT

Objective: to identify the knowledge of health professionals of family health basic units on the clinical

management of suspected chikungunya fever. Method: a cross-sectional study with 31 healthcare professionals of basic units and family health, located in the city of Quixadá-Ceará, in the months of January and February 2018. Results: almost all report to evaluate signs of severity, admission criteria and risk groups, if the patient does not show signs of seriousness does not meet criteria for hospitalization and risk conditions/or should stay in outpatient follow-up; If the patient is only a risk group, he/she must be referred to outpatient follow-up for observation; and if the patient shows signs of severity and/or admission criteria, he should receive follow-up in hospital. Conclusion: health professionals have satisfactory knowledge on the clinical management of the disease based on the guidelines of the Ministry of Health.

Descriptors: Epidemiology; Knowledge; Delivery of health care; Health professionals; Chikungunya fever. RESUMO

Objetivo: identificar o conhecimento de profissionais de saúde de unidades básicas de saúde da família sobre o manejo clínico da suspeita

de febre de chikungunya. Método: realizou-se um estudo transversal com 31 profissionais de saúde de unidades básicas e saúde da família, localizadas no Município de Quixadá-Ceará, nos meses de janeiro e fevereiro de 2018. Resultados: quase todos relatam que ao avaliar sinais de gravidade, critérios de internação e grupos de risco, se o paciente não apresentar sinais de gravidade, não tiver critérios de internação e/ou condições de risco, o mesmo deve permanecer em acompanhamento ambulatorial; se o paciente for apenas do grupo de risco, o mesmo deve receber acompanhamento ambulatorial em observação; e se o paciente apresentar sinais de gravidade e/ou tiver critérios de 1 Undergraduate Nursing Course at the Federal University of Ceará. Master in Public Health from the Federal University of Ceará.

Professor at the Catholic University Center of Quixadá

2 Undergraduate Nursing Course at the Catholic University Center of Quixadá. Nurse for the Family Health Strategy of Boa Viagem-Ceará. 3 Undergraduate Nursing Course at the State University of Ceará. PhD in Nursing from the Federal University of Ceará. Lecturer at the

Catholic University Center of Quixadá.

4 Undergraduate Degree in Pharmacy from the Federal University of Ceará. PhD in Pharmacology from the Federal University of Ceará. Lecturer at the Catholic University Center of Quixadá.

internação, ele deve receber acompanhamento em internação. Conclusão: os profissionais de saúde possuem conhecimento satisfatório sobre o manejo clínico da doença baseado nas orientações do Ministério da Saúde.

Descritores: Epidemiologia; Conhecimento; Assistência à saúde;

Profissionais de saúde; Febre de chikungunya.

RESUMÉN

Objetivo: identificar el conocimiento de la salud profesionales de unidades

básicas de salud de la familiaenel manejo clínico de só pecha Chikungunya fiebre. Método: estudio transversal con 31 profesionales de la salud de unidades básicas y de salud familiar, ubicado em la ciudad de Quixadá-Ceará, em los meses de enero y febrero de 2018. Resultados: informe casi todos para evaluar signos de gravedad, grupos de criterios de admisión y el riesgo, si el paciente no no mostrar signos de seriedad no tienen criterios para las condiciones de la hospitalización y el riesgo/unidad organizativa, debe mantenerse en seguimiento ambulatorio; Si el paciente es sóloel grupo de riesgo, el mismo debe recibir seguimento ambulatorio de observación; y si el paciente muestra signos de criterios de severidad y/o admisión, deben recibir seguimento em hospitalización. Conclusión: profesionales de la salud tienen conocimiento satisfactorio em el manejo clínico de la enfermedad basada en las directrices del Ministerio de Salud.

Descriptores: Epidemiología; Conocimiento; Prestación de atención de

salud; Profesionales de la salud; Fiebre de chikungunya.

INTRODUCTION

Chikungunya fever (CF) is an arbovirus caused by the Chikungunya virus (CHIK V), the Togaviridae family and the genus Alphavirus. It has three phases: acute, subacute and chronic. Propagation occurs by the bite of females of the Aedes Aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes infected with CHIKV. The signs and symptoms are fever, severe joint and muscle pain, headache, nausea, fatigue and rash. The initial and acute phase of the disease can progress into two subsequent stages: subacute phase and chronic phase.1

The acute phase is characterized by abrupt fever above 39ºC and severe arthralgia, headache, diffuse back pain, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, polyarthritis; rash and conjunctivitis may also be present, however less frequently. This phase lasts around three to ten days. In the subacute phase, which goes from the eighth day to the three months, the patient has an improvement in symptoms or may relapse. The chronic phase is defined when symptoms last longer than three months and is characterized by persistent joint, musculoskeletal, neuropathic pain and joint edema.2

In 2018, until epidemiological week 42, 76,711 probable CF cases were recorded in the country and an incidence rate of 36.9 cases/100,000 inhabitants; of these 54,492 (71.0%) were confirmed. The investigation of the incidence rate of probable cases (number of cases/100 thousand inhabitants), by geographic regions, shows that the Midwest and Southeast region have the highest rates, being 85.6 and 52.2 cases/100 thousand inhabitants. respectively. Among the Federative Units, we highlight Mato Grosso (391.9 cases/100 thousand inhabitants), Rio de Janeiro (196.6 cases/100 thousand inhabitants) and Pará (72.9 cases/100 thousand inhabitants). Regarding the number

To date, there is no exclusive antiviral treatment for CF. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, nimesulide, diclofenac, among others, should not be used in the acute phase of the disease due to renal complications and risk of bleeding in patients; aspirin is contraindicated in the acute phase because of the risk of bleeding; and corticosteroids should not be used at this early stage because of the risk of complications. In the subacute or chronic phase, the use of corticosteroids is indicated, and the oral medication is prednisone. In addition, in order to clinically manage the disease, the professional should be careful to identify the signs of severity and risk groups.1

Therefore, as the disease may go through several stages and may become chronic, the patient often cannot control the clinical manifestations of the evolution of the pathology in their homes, requiring the search for guidance or medication in health services, making it essential that the professionals who work there, know the disease and know how to manage each phase clinically. The basic family health unit (UBASF), being closer to the population, is the gateway to the health care network (RAS) and the nurse and the doctor are the first to have contact with the patient seeking care.

Given the above, the study is justified by the high percentage of people who can become chronic when affected by the disease and the lack of knowledge among health professionals about the phases of CF and how to manage each phase clinically, as well as guide prevention and control measures of the disease, which causes patients to return several times to the servicewith the same complaints, that could be resolved at home.

The study is important to identify the knowledge that these health professionals have about the proper clinical management of each phase of CF, encouraging the municipal health departments to develop permanent training on arboviruses, especially CF, as it is a disease, that may evolve over several stages and over long periods of symptom onset. It will also allow to improve the pre-existing knowledge of these professionals, providing a continuous and quality assistance to the population they attend daily.

Thus, the study aims to identify the knowledge of health professionals from basic family health units about the clinical management of suspected CF.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional research conducted at UBASF, located in the city of Quixadá-Ceará.

The study population consisted of health professionals (doctors and nurses) who work in UBASF of the municipality, and the sample consisted of 31 people. The following inclusion criteria were established: to be a doctor or nurse and have been working for more than three months in the municipality’s UBASF. Those doctors and nurses who were on maternity leave, vacation or out of service for some other reason during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

before or after, their care activities. Initially, each participant was presented the purpose of the study and its objectives, explaining the importance of the Informed Consent Form (ICF). After the participant’s signature, the data collection instrument was applied by interview. A form-based instrument was created, based on the MS1 Chikungunya Fever Clinical Management protocol, consisting of three parts: Part I - Socio-demographic profile of health professionals from basic family health units; Part II - Knowledge of health professionals from basic family health units about clinical management in suspected chikungunya fever; Part III - Conduct guided by health professionals from basic family health units for home care.

Data were tabulated by the researcher in a spreadsheet built in Excel 2010®, based on the variables of the form. Then, they were submitted to a statistical analysis by the EPI INFO 7.0 program, generating the percentage frequencies, which were later exposed in tables, interpreted and discussed in the context of the literature on the subject.

Research project was designed according to the ethical criteria recommended in Resolution No. 466/12 of the National Health Council, which regulates research with human beings, and approved under protocol No. 2,490,381.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The study included 31 of the 37 health professionals from UBASF in the municipality. Their sociodemographic characterization showed that most professionals were women (22; 70.7%), between 19 and 59 years old (17; 54.9%), single (16; 51.6%) and belonging to professional category of nurses (18; 58.6%) (Table 1).

When assessing the knowledge of health professionals about the risk classification in suspected CF, most report that the symptomatology of a suspected case of CF in the acute phase is fever for up to seven days + sudden onset of severe arthralgia associated with headache + myalgias + rashes (25; 80.7%); that in case of a suspected case of CF, it is important to consider the history of travel in the last 15 days to areas with the disease (26; 83.9%) and that pregnant women, people over 65, children under two years old and patients with comorbiditiesare all considered risk groups (30; 96.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1 - Health professionals’ knowledge about risk

classification in suspected chikungunya fever. Quixadá, CE, Brazil, 2018

Symptomatology of a suspected case of

acute phase CF n %

Fever for up to 7 days + sudden onset of severe arthralgia and may be associated with

headache + myalgias + rashes 25 80,7 Fever for up to 15 days + sudden onset of

severe arthralgia and may be associated with

headache + myalgias + rashes 05 16,1

All 01 3,2

Importance of Considering Travel History

Over the Last 15 Days to Areas With Disease n %

Yes 26 83,9

Not 05 16,1

Patient (s) are / are considered “risk group (s)” n %

Pregnant women 01 3,2

All 30 96,8

Source: research data (2018).

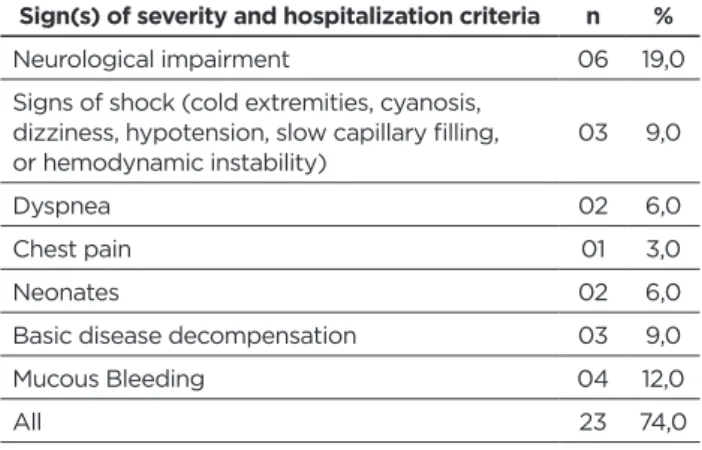

The knowledge of the health professionals of the units about the signs of severity and hospitalization criteria, in case of suspected CF, showed that all reported that the neurological impairment, the signs of shock (cold extremities, cyanosis). , dizziness, hypotension, slow capillary filling or hemodynamic instability), dyspnea, chest pain, neonates, decompensation of underlying disease and mucosal bleeding, (23; 74.0%) are signs of severity and hospitalization criteria (Table 2).

Table 2 - Health professionals’ knowledge about the

sign(s) of severity and hospitalization criteria in suspected chikungunya fever. Quixadá, CE, Brazil, 2018

Sign(s) of severity and hospitalization criteria n %

Neurological impairment 06 19,0 Signs of shock (cold extremities, cyanosis,

dizziness, hypotension, slow capillary filling,

or hemodynamic instability) 03 9,0

Dyspnea 02 6,0

Chest pain 01 3,0

Neonates 02 6,0

Basic disease decompensation 03 9,0

Mucous Bleeding 04 12,0

All 23 74,0

Source: Research data (2018).

Analyzing the knowledge of health professionals about the clinical management of patients with suspected CF, i.e. the type of follow-up that the patient should receive according to the clinic presented, almost all report that when evaluating the signs of severity, criteria for hospitalization and risk groups, if the patient does not show signs of severity, does not have hospitalization criteria and / or risk conditions, he / she should remain in outpatient follow-up (26; 83.9%); if the patient is only from the risk group, he / she should receive outpatient follow-up (27; 87.7%); and if the patient shows signs of severity and / or has hospitalization criteria, he should be hospitalized (22; 70.9%) (Table 3).

Table 3 - Health professionals’ knowledge regarding the

type of follow-up the patient should receive when assessing signs of severity, hospitalization criteria and risk groups. Quixadá, CE, Brazil, 2018.

If the patient shows no signs of severity, does not have hospitalization criteria and /

or risk conditions n %

Outpatient follow-up 26 83,9 Outpatient follow-up observation 05 16,1

If the patient is from the risk group only n %

Outpatient follow-up 04 12,3 Outpatient follow-up observation 27 87,7

If the patient shows signs of severity and /

or has hospitalization criteria n %

Outpatient follow-up 03 9,7 Outpatient follow-up observation 04 12,9 Inpatient follow-up 22 70,9

All 02 6,5

Source: Research data (2018).

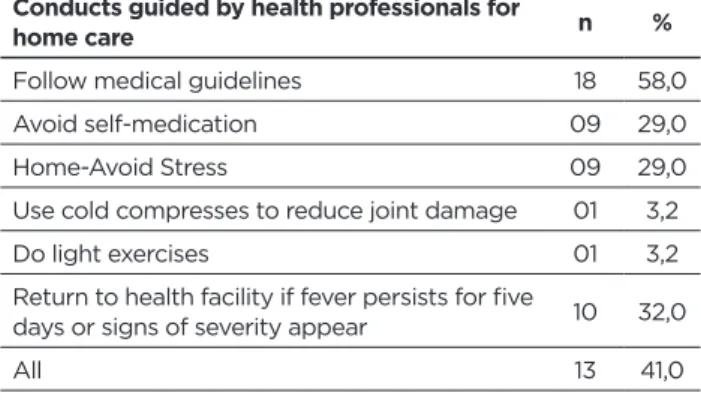

Regarding the options of home care, if the patient shows no signs of severity, has no criteria for hospitalization and / or risk conditions, many advise: follow medical guidelines (18; 58.0%) ; all possible types of conduct (13; 41%); return to the health facility if fever persists for five days or signs of severity appear, (10; 32.0%); avoid self-medication (nine; 29.0%) and rest-avoid exertion (nine; 29.0%) (Table 4).

Table 4 – Conduct recommended by health professionals for

home care, if the patient does not show signs of severity, does not have hospitalization criteria and / or risk conditions. Quixadá, CE, Brazil, 2018

Conducts guided by health professionals for

home care n %

Follow medical guidelines 18 58,0 Avoid self-medication 09 29,0 Home-Avoid Stress 09 29,0 Use cold compresses to reduce joint damage 01 3,2 Do light exercises 01 3,2 Return to health facility if fever persists for five

days or signs of severity appear 10 32,0

All 13 41,0

Source: Research data (2018).

Regarding conducts guided by health professionals for home care, if the patient is only from the risk group, the vast majority report advising: follow medical guidelines (14; 45.0%), all types of conduct (14; 45 , 0%); avoid self-medication (11; 35.0%) and rest-avoid exertion (seven; 22.0%) (Table 5).

Table 5 - Conduct recommended by health professionals

for home care, if the patient is only from the risk group. Quixadá, CE, Brazil, 2018

Conducts guided by health professionals

for home care n %

Follow medical guidelines 14 45,0 Avoid self-medication 11 35,0 Home-Avoid Stress 07 22,0 Use cold compresses to reduce joint damage 03 9,0 Do not use hot joint compresses 02 6,0 Do light exercises 02 6,0 Return to health facility daily until fever

subsides 05 16,0

All 14 45,0

Source: Research data (2018).

Sociodemographic characteristics are similarity to the research study that also found a nursing staff predominantly composed of female professionals (85.1%), with similar age group of people between 36 and 50 years (40.0%), and composed by nurses (23.0%)4; as well as another study, in which most were also women (88.6%), aged 26 to 30 years, but married (49.4%)5. This shows us a profile of young people, most often recent graduates, who enter the job market through primary care. There are many women in the health team, due to the higher prevalence of female nurses as part of the team, as shown by the research results; and an absence of medical professionals, both in FHS teams and physically in UBASF, during their working hours, much experienced during the research.

Regarding the symptoms of a suspected case in the acute phase and risk classification, the acute phase of CF begins with a sudden onset of high fever, usually around 40ºC, associated with malaise and severe polyarthralgia. Joint pain usually appears within the first 48 hours and affects about 90% of patients with the disease.6 Affected individuals may also have myalgia (60.0-93.0%), headache (40.0-81.0%) and maculopapular eruption (35.0%)7. Still, joint pain affects up to 80% of patients and persists for a long time, sometimes lasting for years.8

Regarding the dislocation of a suspected CF patient, it is important to consider the history of travel over the past 15 days to areas with virus transmission due to the easy chain of disease transmission and the ease of travel between regions of the country and the world. In addition, a patient with sudden onset fever, greater than 38.5°C, or severe acute onset arthralgia or arthritis, not explained by other conditions, being resident or having visited endemic or epidemic areas up to two weeks before the onset of symptoms or epidemiologically linked, is considered a confirmed case of CF. Therefore, this condition should be part of the assessment of the risk classification of this patient.1

As for patients in the risk group, among them, pregnant women, CF shows a direct impact on pregnancy, but still with rare reports of spontaneous abortions and mother-to-child transmission.9 A study comparing mothers suffering from CF in the perinatal period, in relation to transmitting the virus to their newborns, by vertical transmission, estimates that the prevalence of the transmission rate in this period can reach up to 85%, when occurs four to five days before delivery, resulting in severe deformation in 90% of newborns.1 Other research shows that infected mothers, from four days before delivery to one day postpartum, can transmit the virus to the newborn, estimating a transmission rate prevalence of up to 49%, with a high risk of evolution of deformities in baby’s anatomy.10

In addition, according to the risk classification, in case of a suspected case of CF, the blood count must be requested, necessarily for patients in the risk group; and transaminases, creatinine and electrolyte biochemistry for patients with signs of severity and hospitalization criteria.1

Therefore, it is noteworthy that cases with signs of severity (neurological impairment, hemodynamic instability, dyspnea, chest pain, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding and decompensation of underlying disease) or those with hospitalization criteria (neonates) should be monitored in unitswith hospital beds.11 For the discharge of these patients, it is necessary to improve their general condition, ensure the acceptance of oral hydration, and the absence of signs of severity and improvements in laboratory parameters.11

A study showed that atypical cases requiring hospitalization were described, at risk of unfavorable outcome, i.e., of the 610 adults who participated in the study and had CF complications, 37% had cardiovascular changes (heart failure, arrhythmia, myocarditis, coronary disease 24% had neurological disorders (encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, seizures, Guillain Barré syndrome), 20% pre-renal renal failure, 17% pneumonitis, 8% respiratory failure, among the most frequent causes.12

It is known that patients without sever symptoms, without risk conditions and without hospitalization criteria as well as patients with risky conditions but no signs of severity should be monitored in primary care; On the other hand, those who show signs of severity should look directly for an emergency unit (UPA) or hospital emergency, as they need to be admitted. In addition, patients in the risk group should receive outpatient follow-up with daily return guidance,until fever ceases and signs of severity are absent. Already, all neonates who show signs of severity or hospitalization criteria should be followed in hospitalization beds.1

Thus, if the patient does not show signs of severity, does not have hospitalization criteria and / or risk conditions, in addition to drug treatment for pain relief, appropriate hydration, use of hot andcold compresses to reduce joint pain should be advised, and the patient should return to the health unit if fever persists for more than five days or signs of

complications appear.1 Active exercises can be recommended, with mild intensity, to maintain the joint functions and, with caution, not to exacerbate inflammatory symptoms.13

If the patient is only from the risk group, there is evidence that rest is a protective factor to prevent progression to the subacute phase, therefore being extremely important; and activities that overload the joints should be avoided, while proper limb positioning favoring joint protection and venous return should be maintained. In many situations, the medical leave is fundamental so that the patient can, in fact, take time off work and rest properly.1

Regular physical activity shows a possible anti-inflammatory effect, helping to reduce drug consumption in cases of chronic pathologies. Still, in the same study, only 24.1% do some kind of regular physical activity, 2 to 5 times a week.14

Another survey of 43-year-olds showed that 89.7% of all subjects included in the study reported time off work; 29.1%, economic losses; 73.1%, difficulty in performing their daily activities; and 67.3%, mood swings. I.e. a reduction in quality of life due to the intensity of the symptoms presented and a lack of guidance by professionals working in health services sought by patients in the early phase of the disease were reported.15

CONCLUSION

Health professionals have a satisfactory level of knowledge of CF, knowing, in the face of a suspicious case, to evaluate important criteria in risk classification, as well as to identify signs of severity and hospitalization criteria; manage the disease according to the clinic presented; and guide home care for signs of severity, hospitalization criteria and risk conditions.

The study was important for health services to analyze how is the knowledge of health professionals who work with CF patients regarding clinical management, encouraging health departments to develop permanent training on arboviruses, especially CF, because it causes late clinical outcomes and may present in more than one phase.

This study summarized here has limitations as regards the availability and the interest of professionals from both categories to answer the questionnaire. They blamed the lack of time, said they were afraid to answer the form, others thought it was too long, and some nurses even said that only doctors could answer. There is also a shortage of studies on the subject.

The CF Clinical Management Manual is expected to be adapted to the needs of each service, improving the quality of patient care in health institutions and this study will also serve as a basis for future research on the proposed theme.

Thanks

Acknowledgments to the Secretariat of Health of the Municipality of Quixadá for their encouragement and support in conducting the study.

REFERENCES

1. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção Básica. Chikungunya: Manejo Clínico [internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017 (accessed 01 of March de 2018). http:// bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/chikungunya_manejo_clinico.pdf 2. Catro APCR, Lima RA, Nascimento JR. Chikungunya: vision of the

pain clinician. Rev Dor [internet]. 2016 Out-Dez (accessed 03 March 2018); 14(4):299-302. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rdor/v17n4/pt_1806-0013-rdor-17-04-0299.pdf

3. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Boletim Epidemiológico – Volume 49 - nº 42 – 2018. Monitoramento dos casos de dengue, febre de chikungunya e doença aguda pelo vírus Zika até a Semana Epidemiológica 38 de 2018 [internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2018 (accessed 05 March, 2018). http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2018/ outubro/26/2018-049.pdf

4. Machado MH, Filho WA, Lacerda WF, Oliveira E, Lemos W, WermelingerM et al. Características gerais da enfermagem: o perfil sociodemográfico. RevEnfermFoco [internet]. 2015 (accessed on 02 of March 2018); 6(1):11-7. http://revista.cofen.gov.r/index.php/ enfermagem/article/view/686/296

5. Corrêa ACP, Araújo EF, Ribeiro AC, Pedrosa ICF. Perfil sociodemográfico e profissional dos enfermeiros da atenção básica à saúde de Cuiabá-MatoGrosso. Rev Eletrônica Enferm[internet]. 2012 Jan-Mar (accessed 02 de March 2018); 14(1):171-80, 2012. https:// www.revistas.ufg.br/fen/article/view/12491/15570

6. Renault P, Solet J-L, Sissoko D, Balleydier E, Larrieu S, Filleul L, et al. Major Epidemic of Chikungunya Virus Infection on Réunion Island, France, 2005-2006. Am J TropMedHyg [internet]. 2007 (accessed 04 March 2018); 77(4): 727–31. http://www.ajtmh.org/content/journals/10.4269/ ajtmh.2007.77.727;jsessionid=4JpxIPZj7FCuhdCl2HevahQ7.ip-10-241-1-122

7. Waymouth HE, Zoutman DE, Towheed TE. Chikungunya-related arthritis: case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum [internet]. 2013 (accessed 06 March 2018); 43(2): 273-78. https://www. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049017213000504

8. Honório NA, Câmara DCP,Calvet GA, Brasil P . Chikungunya: uma arbovirose em estabelecimento e expansão no Brasil. CadSaúde Pública [internet]. 2015 Mai (accessed 06 March, 2018); 31(5): 906-08. https:// www.scielosp.org/pdf/csp/2015.v31n5/906-908/pt

9. Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Informação para profissionais de saúde. Febre de Chikungunya. Documento científico [internet]. Rio de Janeiro: OPAS; 2014 (accessed 07 March, 2018). https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2014/POR-CHIK-Aide-memoire--clinicians.pdf

10. GérardinP,Sampériz S, Ramful D, Boumahni B, Binter M, Alessandri J-L, et al. Neurocognitive Outcome of Children Exposed to Perinatal Mother-to-Child Chikungunya Virus Infection: The CHIMERE Cohort Study on Reunion Island. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases [internet]. 2014 Jul (accessed 07 March 2018); 8(7): 1-14. https://journals.plos.org/ plosntds/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0002996&type=printable 11. Marques CDL, Duarte ALBP, Ranzolin A, Dantas AT, Cavalcanti NG,

Gonçalves RSG, et al. Recomendações da Sociedade Brasileira de Reumatologia para Diagnóstico e Tratamentos da Febre Chikungunya. RevBrasReumatol [internet]. 2017 (accessed 07 March 2018); 57(2): 421-37. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0482500416301917?toke n=58D335E63923319ABE8333ACD3164-C55640CD5B8286D65E56-DE12F4059ECDF00EE429A6D6E1C80C5821757F8BA634B44 12. Economopoulou A, Dominguez M, Helynnck B, Sissoko D, Wichmann

O, Quenel P, et al. Atypical Chikungunya virus infections: clinical manifestations, mortality and risk factors for severe disease during the 2005-2006 outbreak on Réunion. EpidemiolInfect [internet].2009 (accessed07 March 2018); 37(4):534–41. https://www.cambridge. org/core/journals/epidemiology-and-infection/article/atypical- chikungunya-virus-infections-clinical-manifestations-mortality-and- risk-factors-for-severe-disease-during-the-20052006-outbreak-on-reunion/33DA6DD44AA27ACE3B2216FCA688A592

13. Simon F, Javelle E, Cabie A, Bouquillard E, Troigross O, Gentile G, et al. French guidelines for the management of chikungunya (acute and persistent presentations). Med Mal Infect [internet]. 2015 (accessed 09 March 2018); 45(7): 243-63. https://www.researchgate.net/ profile/Emilie_Javelle/publication/279313162_French_guidelines_ for_the_management_of_chikungunya_acute_and_persistent_

14. JORGE, M.S.G; WIBELINGER, M.L; KNOB, B; ZANIN, C. et al. Intervenção fisioterapêutica na dor e na qualidade de vida em idosos com esclerose sistêmica. Relato de casos.Rev Dor [internet]. 2016 Abr-Jun (accessed 09 March, 2018); 17(2):1 48-51, 2016. http://www.scielo. br/pdf/rdor/v17n2/1806-0013-rdor-17-02-0148.pdf

15. Alves NM. Apresentação clínica da forma crônica da chikungunya em Feira de Santana-BA [internet]. Salvador (BA): Universidade Federal da Bahia. Salvador: Bahia; 2017 (accessed 13 March 2018). https:// docplayer.com.br/54761505-Apresentacao-clinica-da-forma-cronica-da-chikungunya-em-feira-de-santana-ba.html Received in: 01/11/2018 Required revisions: 15/05/2019 Approved in: 01/10/2019 Published in: 10/01/2020 Corresponding author

Regina Kelly Guimarães Gomes Campos

Address: Rua Juvencio Alves, 660, Centro

Quixadá/CE, Brazil

Zip code: 63900-000 E-mail address: reginakelly@unicatolicaquixada.edu.br Telephone number: +55 (88) 3412-6700