SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE ORTOPEDIA E TRAUMATOLOGIA

w w w . r b o . o r g . b r

Update

Article

Hamstring

injuries:

update

article

夽

Lucio

Ernlund

∗,

Lucas

de

Almeida

Vieira

InstitutodeJoelhoeOmbro,Curitiba,PR,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received17August2016 Accepted19August2016 Availableonline1August2017

Keywords:

Muscleskeletal/injuries Athleticinjuries Returntosport

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Hamstring (HS)muscleinjuriesarethemostcommoninjuryinsports.Theyare corre-latedtolongrehabilitationsandhaveagreattendencytorecur.TheHSconsistofthelong headofthebicepsfemoris,semitendinosus,andsemimembranosus.Thepatient’sclinical presentationdependsonthecharacteristicsofthelesion,whichmayvaryfromstrainto avulsionsoftheproximalinsertion.Themostrecognizedriskfactorisapreviousinjury. Magneticresonanceimagingisthemethodofchoicefortheinjurydiagnosisand classifi-cation.Manyclassificationsystemshavebeenproposed;thecurrentclassificationsaimto describetheinjuryandcorrelateittotheprognosis.Thetreatmentisconservative,with theuseofanti-inflammatorydrugsintheacutephasefollowedbyamuscle rehabilita-tionprogram.Proximalavulsionshaveshownbetterresultswithsurgicalrepair.Whenthe patientispainfree,showsrecoveryofstrengthandmuscleflexibility,andcanperformthe sport’smovements,he/sheisabletoreturntoplay.Preventionprogramsbasedoneccentric strengtheningofthemuscleshavebeenindicatedbothtopreventtheinitialinjuryaswell aspreventingrecurrence.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditora Ltda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Lesões

dos

isquiotibiais:

artigo

de

atualizac¸ão

Palavras-chave:

Musculoesquelético/lesões Traumatismoematletas Retornoaoesporte

r

e

s

u

m

o

As lesões dos músculosisquiotibiais (IT) sãoas maiscomuns doesporte e estão cor-relacionadascomumlongotempodereabilitac¸ãoeapresentamumagrandetendência de recidiva.OsITsãocompostospelacabec¸a longadobícepsfemoral,semitendíneoe semimembranoso.Aapresentac¸ãoclínicadopacientedependedascaracterísticasdalesão, quepodemvariardesdeumestiramentoatéavulsõesdainserc¸ãoproximal.Ofatorderisco maisreconhecidoéalesãoprévia.Aressonânciamagnéticaéoexamedeescolhapara

夽

StudyconductedattheInstitutodeJoelhoeOmbro,MedicinaEsportivaeFisioterapia,Curitiba,PR,Brazil. ∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:ernlund@brturbo.com.br(L.Ernlund).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rboe.2017.05.005

odiagnósticoeclassificac¸ãodalesão.Muitossistemasdeclassificac¸ãotêmsido propos-tos;osmaisatuaisobjetivamdescreveralesãoecorrelacioná-lacomoseuprognóstico. Otratamentodaslesõeséconservador,comousodemedicac¸õesanti-inflamatóriasna faseaguda,seguidodoprogramadereabilitac¸ão.Aslesõesporavulsãoproximaltêm apre-sentadomelhoresresultados comoreparocirúrgico. Quando opaciente estásemdor, apresentarecuperac¸ãodaforc¸aedoalongamentomusculareconseguefazeros movimen-tosdoesporte,estáaptopararetornaràatividadefísica.Programasdeprevenc¸ão,baseados nofortalecimentoexcêntricodamusculatura,têmsidoindicadostantoparaevitaralesão inicialcomoarecidiva.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublicadoporElsevier EditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Historically,hamstring(HS)injuriesaredescribedas frustrat-ingforathletesastheyarecorrelatedwithalongrehabilitation time; theyhaveatendency torecurand return tosport is unpredictable.1,2

Notallinjuriesaresimilar.Theyrangefrommildmuscle damagetocomplete tearofmuscle fibers.Furthermore,as withthecharacteristicsofthelesions,rehabilitationtimeis alsovariable.3,4

HSinjuriesarethemostcommoninsports.Theyarethe mostfrequently reported injuriesinsoccer, accounting for 37%ofthemuscular injuriesobservedinthat sport,which is the most popular in the world, with over 275 million practitioners.5,6

Injuryincidenceisestimatedat3–4.1/1000hof competi-tionand0.4–0.5/1000hoftraining.Ameanincreaseof4%per yearhasbeenreported;therateofinjuriesoccurringin train-ingsessionshasincreasedmorethanthatofthoseoccurring duringcompetitiveactivities.7,8

Afterthe injury, runnersneed 16 weeks,on average, to returntosportwithoutrestrictions,whiledancerscantake upto50weeks.Inprofessionalsoccer,theathleteremains,on average,14daysawayfromcompetitiveactivities.HSinjuryis themaincauseofinjuryabsence.2,7,9,10

Inadditiontosoccer,injuriesarecommoninsportssuch as football, Australian football, track and field, and water skiing. The most common trauma mechanism is indirect trauma;injuriestendtooccurduringnon-contactactivities, andrunningistheprimaryactivity.Sportsthatrequire bal-listicmovementsofthelowerlimb,suchasskiing,dancing, andskating,areassociatedwithproximalavulsionoftheHS tendons.3,11

Themyotendinousjunction(MTJ)isthemostvulnerable partofthemuscle,tendon,andbonejunction;themore prox-imaltheinjury,thelongerthereturntosportactivity.11,12

Ofallmuscleinjuries,thoseofHShaveoneofthehighest recurrencerates,which isestimatedtorangebetween12% and33%.RecurrenceisthemostcommoncomplicationofHS lesions.2,6,7

Anatomy

The HS muscle groupconsists ofthe semitendinosus(ST), semimembranosus (SM), and the long head of the biceps femoris(LHBF).Thesethreemusclesoriginateintheischial tuberosity (IT) as a common tendon, passing through the hip and knee joints; they are biarticular muscles and are innervated bythe tibialportion ofthesciatic nerve.In the posterior region ofthe thigh, the shorthead ofthe biceps femoris(SHBF),whichoriginatesintheposterolateralregion of the femur in the linea aspera and in the supracondy-lar ridge, is added to the HS group. Thus, the SHBF is a monoarticular muscle innervated by the common fibular nerve(Fig.1).2,3,5

Inananatomicalstudy ofthe HS,Van derMadeetal.11 describedthattheHSisdividedintotwoportions,upperand lower.Theupperportionissubdividedintotwofacets.The lateralfacetistheoriginofSM,whereasthemedialfacetis theoriginoftheSTandLHBF,whichalsohasoriginsinthe sacrotuberalligament.2

TheSTandSMextendtotheposteromedialregionofthe thigh,withinsertionsinthepesanserinusandthe posterome-dialcornerofthekneeandtibia,respectively.Inanagonistic pattern,thesemusclesactinkneeflexionandmedial rota-tion,aswellasinhipextension;laterally,theLHBF actsin anisolatedmannerproximally,extendingthehipand poste-riorstabilizingthepelvis.Thedistaltendonthatisinserted in thehead ofthefibula isformeddistally, afterthe addi-tion oftheSHBFfibers,whichflex theknee withthethigh inextension.1–3,5

a

c

d

b

Semitendinosus Semimembranosus

Long head of the biceps

femoris Hamstrings

Fig.1–Schematicdrawingofthehamstrings.

Clinical

picture

Clinicalpresentationofthepatientdependsonthe charac-teristicsofthelesion,whichcanrangefromstretchingofthe musclefiberstotendonrupture. Nonetheless,regardlessof strainsorruptures,proximallesionsaremuchmorecommon thandistallesions.TheLHBFisthemostfrequentlyinjured muscleand,despitethelackofconsensus,theSMis consid-eredtobethesecondmostaffectedmuscle.2,5,11

Asklingetal.13proposedtwotypesofacuteinjuries.First typeoccursduringsprinting,andaffectstheLHBF.Thesecond typeisassociatedwithexcessiveHSstretchinginmovements suchaskickinginsoccerortacklinginfootball,andmostoften affectstheSM.

Eccentriccontractionisthemuscularactioninwhichthe fibersareelongatedasaresultofanexternalforce,andatthe sametimecontracttodeceleratethemovement.Inindirect trauma,themaximumeccentriccontractionperiodappearsto presentthegreatestriskformuscleinjury;themostcommon injurysiteistheMTJ,sinceitbearsthegreatesteccentricloads.

Directtraumaisanothermechanismofinjury,especiallyin sportswithbodycontact.Itislessfrequentandismainly asso-ciatedwithlesionsofthemuscularbellies.IntheHS,delayed onset muscle sorenessis inducedbyeccentric contraction, representinganothercommonsports-relatedcondition.2,3,7

ProximalavulsionoftheHSorigincorrespondsto12%of theselesions.Itisestimatedthat9%ofthesearecomplete avulsions,whichisconsideredtobethemostserious.The typ-icalmechanismofproximalavulsioniseccentriccontraction oftheHS,asaresultofsuddenhiphyperflexion,withtheknee inextension.Thismovementismostcommonlyobservedin waterskiing.2,3,7,14

Clinically,patientpresentswithasuddenpaininthe pos-terior region of the thigh. The report of an audible click and theinability tocontinuewithphysicalactivity is com-mon.Antalgicgaitdevelopstominimizemobilizationofthe involvedmusclemassanddecreasehipextensionandknee flexion.Intheacutephase,themostcommonclinicalsignsare hematomaorecchymosisintheposteriorregionofthethigh, painfulpalpationoftheITregion,andmuscleweakness. Usu-ally,hematomavolumeiscorrelatedwithlesionseverity,but itsabsencecannotbeconfusedwithaminorlesion,sincethis signmaybelateeveninthemostseverelesions.5,7

HS strengthcan betestedthroughknee flexionand hip extensionagainstresistance.Abilateralcomparisonis indi-cated toidentifythe alterations. The “takingoff the shoe” clinicaltestisalsodescribedasameansofassessingtheHS. Thepatientisaskedtoremovetheshoeipsilateraltotheinjury inthestandingposition,withthehelpofthecontralateralfoot. Byleveragingthebackofthefootonthecontralaterallimb,the patientwillflexthekneeandtriggerpainordemonstratethe weaknessoftheaffectedmuscles.2,9

In proximal avulsion, a local gap may be palpable, but sometimesitcanbemaskedbythehematoma. Discomfort in sitting may be reported; palpation helps toidentify the locationandwhichmusclesareinjured.Completeruptureis definedastheruptureofthethreeHStendons(BF,ST,and SM).Theropesignhasbeenproposedtodifferentiatebetween partialandcompletetendonavulsion.Apositivetestis char-acterizedbytheabsenceofpalpabletensioninthedistalpart ofthe HS withthe patient inthe prone position,with the knee flexedto90◦.Avulsion canalsobeevaluatedincases ofkneeflexionagainstresistance,whentheavulsedmuscle massretractsdistally.2,5,9,15,16

Neurological clinicalexaminationshould alwaysbe per-formedincaseofHS injury.Duetolocalproximity,muscle injuriesmaybecorrelated withneurologicallesions,which may manifestwithparesthesiaormotoralterations. Inthe chronicphasesofthelesions,sciaticasymptomsmayarise.5,7 Inthe acutephase,thepain picturegreatly impactsthe clinicalevaluationofthepatient.After48h,theacute limita-tionofpainisexpectedtohavedecreased,andtheresultofthe physicalexaminationmaybemorerelevantbothfordiagnosis andforprognosis.Therefore,specificevaluationisindicated withintwodaysaftertheinjury.9

Risk

factors

ManystudieshavesoughttoidentifytheriskfactorsforHS injury.Theabilitytorecognizetheathleteswithpredisposition andthesituations thatcanleadtoinjuryisparamountfor prevention,inordertoavoidlongperiodsofrehabilitationand injuryleave.17

Amongtheriskfactors,thespecificcharacteristicsofthe muscles play an important role. HS muscle imbalance is definedbythedifferenceinmusclestrengthwhencompared withthecontralateralside,oranalterationintheratioofHS strengthtoipsilateralquadricepsstrength.Theriskofinjuryis higherwhenthestrengthdeficitbetweentheHSis>10–15%,or whenthestrengthratiobetweentheHSandthequadricepsis <0.6.However,thesevaluesmayvaryaccordingtoeachathlete andsport.3

Thesportingmotionisalsoapredisposingfactorofinjury. Athletes who anteriorly tilt the pelvis at the moment of accelerationduring the strideincrease the tension on the HS.Furthermore,iliopsoasshorteningandimbalanceofthe abdominalandlumbarmusculaturemayalsopromotepelvic anteversion,placingtheHSatamechanicaldisadvantageby increasingmuscletensionattheendoftheswingphaseofthe gaitcycle.2

Extrinsicfactorscanalsoinfluencetheprobabilityofinjury. Injuriesaremorecommonduringcompetitionsthantraining; shortpre-seasonsarealsocorrelatedwithagreater chance ofinjury.Athleteswhohavetorunduetotheirpositionsare atgreaterriskofinjury.Insoccer,injuriesonthedominant sidearemoreserious,astheyarecorrelatedwiththekicking movement.2,7,10,18

PreviousHSinjuryistheriskfactormostcommonly cor-relatedwithnewlesions.Injuryrecurrenceafterreturningto sportremainsthemaincomplicationofthispathology. Recur-renceismorecommon whenthelesion involvesthe LHBF. VanBeijsterveldtetal.17conductedasystematicreviewof11 prospectivestudiesinvolving1775malesoccerplayerswith 334HSinjuries.TheseauthorsobservedthatpriorHSlesion was significantlycorrelated withrisk fora new lesion.HS injuryrecurrenceratesarereportedtorangefrom14%to63% withintwoyearsaftertheinitialinjury.3,4,7,19

Prunaetal.20 hypothesizedthatthegeneticprofilecould explainwhysomeelitesoccerplayersaremorepredisposed toinjuriesthanothers,aswellasthereasonforthemarked timevariationintherehabilitationofinjuries.

RegardingproximalHSavulsions,completerupturestend tooccurinpatientswithpreviouslocaltendinopathy.3

Imaging

tests

Imagingtestsconfirmthediagnosisandprovideinformation fortherapeuticdecision-making.

Asafirstmodality,theradiographicstudyisindicatedfor rulingoutHSavulsionfractures,especiallyinskeletally imma-turepatients.3

Ultrasonography(US)hastheadvantageofbeing afford-ableandinexpensive;however,itisoperator-dependent.The examinationshould beperformedbetweenthe secondand

seventh daysafterthe trauma;that injurycanbedetected throughvisualizationofthehematomaandthediscontinuity ofthefibers.Itisalsopossibletomeasurethelength,width, depth,andcross-sectionalareaofthemuscleinjury.In proxi-malcases,thismethodhasgreaterlimitationstomeasurethis lesion.3,5,18

Magneticresonanceimaging(MRI)isthemodalityofchoice foridentifyinganddescribinglesions,especiallythoseof prox-imallocation.Itpreciselydefinesthesiteofinjury,itsseverity and extension, the involvedtendons, and theretractionof musclemass.3,5,21,22

ThereisstillnoconsensusontheoptimalmomentforMRI assessment.Someauthorsadvocatethatthetestshouldbe performedbetween24hand48haftertrauma,whileothers advocatethatthisintervalshouldbebetween48hand72h. ThesignsofthelesionaremainlyrecognizedinT2-weighted imageswithfatsuppressionorinshort-tauinversionrecovery (STIR);theyaremoreapparentfrom24huptofivedaysafter trauma.9

AlthoughMRIisthegoldstandardexam,13%ofHSlesions inprofessionalsoccerplayersmaynotbeidentifiedbyMRI. Thereasonforthisisstillunknown.Onehypothesisisthat thesearesmalllesionsthatarenotdetectable,anotheristhat thesymptomsmaybecausedbyotherpathologies,suchas lowbackpainorneurologicalchanges.23

For follow-upofthe injuries,MRIismoresensitivethan US.Theimageswouldbeusefulinmoreseverecasesandin theassessmentofprogressionandrehabilitation,aidinginthe decisionofreturntosportineliteathletes.In34–94%ofcases, signsofHSinjuryarestillvisibleaftersixweeks.9

Classification

Classificationsystemsareusefulforphysicians,athletes,and theircoaches,astheyguidetreatmentandprognosis.Awide varietyofclassificationsbasedonclinicalsignsandalterations inUSandMRIimagingtestshasbeenproposed.However,due tothecomplexityandheterogeneityofmuscleinjuries,there isstillnowidelyacceptedclassificationsystem.9,24,25

Inclinicalpractice,athree-degreesystemisthemost com-monly used, classifying the injury as minor, moderate, or completemuscletear.Variationscorrelatedwithimagingtests havealsobeendescribed.25,26

Peetrons27 groupedlesions intogrades,according tothe alterationsobservedintheUS.GradeIincludeslesionsthatdo notpresentalterationinthemusculararchitecture,buthave signsofedemaaroundthemuscle.GradeIIincludespartial ruptures,andGradeIIIinjuriespresent completemuscleor tendontear.

Recently,newclassificationsystemshavebeendeveloped; thesesystemsaimtobemorecomprehensiveand to stan-dardizetheterminologyofmuscleinjury,aswellastoprovide eachdegreeofinjurywithaprognosis,whichdoesnotoccur inthethree-degreeclassification.24–28

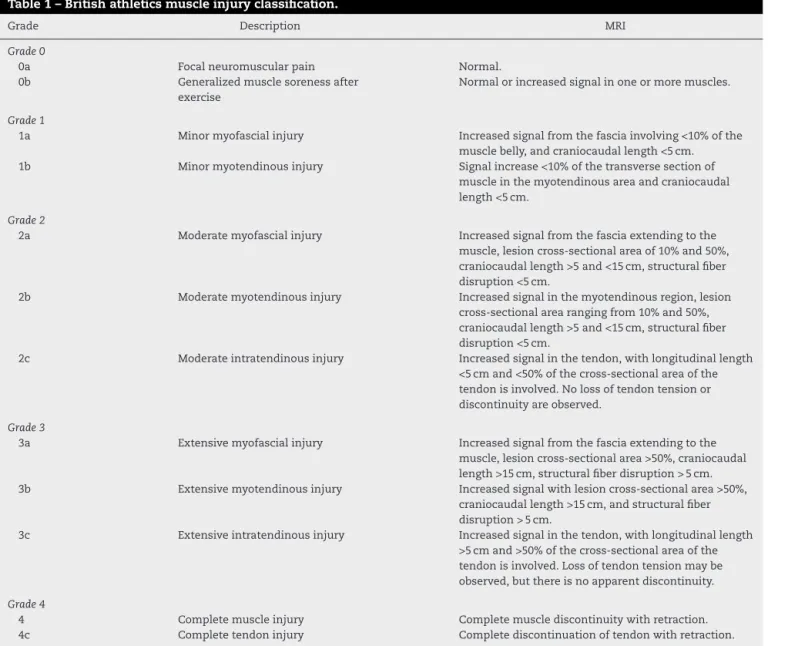

Table1–Britishathleticsmuscleinjuryclassification.

Grade Description MRI

Grade0

0a Focalneuromuscularpain Normal.

0b Generalizedmusclesorenessafter

exercise

Normalorincreasedsignalinoneormoremuscles.

Grade1

1a Minormyofascialinjury Increasedsignalfromthefasciainvolving<10%ofthe

musclebelly,andcraniocaudallength<5cm.

1b Minormyotendinousinjury Signalincrease<10%ofthetransversesectionof

muscleinthemyotendinousareaandcraniocaudal length<5cm.

Grade2

2a Moderatemyofascialinjury Increasedsignalfromthefasciaextendingtothe

muscle,lesioncross-sectionalareaof10%and50%, craniocaudallength>5and<15cm,structuralfiber disruption<5cm.

2b Moderatemyotendinousinjury Increasedsignalinthemyotendinousregion,lesion

cross-sectionalarearangingfrom10%and50%, craniocaudallength>5and<15cm,structuralfiber disruption<5cm.

2c Moderateintratendinousinjury Increasedsignalinthetendon,withlongitudinallength

<5cmand<50%ofthecross-sectionalareaofthe tendonisinvolved.Nolossoftendontensionor discontinuityareobserved.

Grade3

3a Extensivemyofascialinjury Increasedsignalfromthefasciaextendingtothe

muscle,lesioncross-sectionalarea>50%,craniocaudal length>15cm,structuralfiberdisruption>5cm.

3b Extensivemyotendinousinjury Increasedsignalwithlesioncross-sectionalarea>50%,

craniocaudallength>15cm,andstructuralfiber disruption>5cm.

3c Extensiveintratendinousinjury Increasedsignalinthetendon,withlongitudinallength

>5cmand>50%ofthecross-sectionalareaofthe tendonisinvolved.Lossoftendontensionmaybe observed,butthereisnoapparentdiscontinuity.

Grade4

4 Completemuscleinjury Completemusclediscontinuitywithretraction.

4c Completetendoninjury Completediscontinuationoftendonwithretraction.

Grade0injuriespresentnoalterationonMRI.Thisgrade representsfocalneuromuscularpainandgeneralizedmuscle paincausedbyexercise.Grade1injuriesareminormuscle injuriesinwhichtheathleteexperiencespainduringorafter theactivity.Rangeofmotion(ROM)isnormalandthestrength ispreserved.InGrade2injuries,moderatemuscledamageis observed.Theathletepresentspainduringtheactivityand must interruptit. TheROM ofthe affected limbislimited

duetopain,andmuscleweaknessisusuallydetectedupon

clinicalexamination.InGrade3,muscleinjuriesare exten-sive.Theathleteusuallysuffersanabruptpain,andmayfall. Evenafter24h,ROMisusuallyreducedandthepainpicture persists.Thereisanobviousmusclecontractilityweakness. Finally,Grade4representscompletemuscleortendontear. Theathletepresentssudden painandactivitylimitation.A palpablegap canbeperceived.Normally,thecontraction is lesspainfulthanthatobservedinGrade3injuries.26

The clinical application of the British Athletics Muscle InjuryClassificationwasdemonstratedbyPollocketal.22 in astudythatassessed65HSlesionsin44trackandfield ath-letes.Thehigherthegradeofthelesion,thelongerthetime

ofrehabilitationandthehighertherateofrelapse.Caseswith tendoninvolvement(typeC)weremoresusceptibletorelapse andhadalongerrehabilitationtime.

Table2distinguishesbetweentwomaingroupsofmuscle injuries28:injurybydirectorindirecttrauma.Withinthegroup ofinjuries duetoindirect trauma,the classificationbrings theconceptoffunctionalandstructurallesions.Functional muscleinjuriespresentalterationswithoutmacroscopic evi-denceoffibertear.Theselesionshavemultifactorialcauses andaregroupedintosubgroupsthatreflecttheirclinical ori-gin,suchasoverloadorneuromusculardisorders.Structural muscleinjuriesarethosewhoseMRIstudypresents macro-scopicevidenceoffibertear,i.e.,structuraldamage.Theyare usuallylocatedintheMTJ,astheseareashavebiomechanical weakpoints.

Table2–Munichclassification.

Typeofinjury Definition Symptoms MRI

Direct Contusion:blunttraumafromexternalfactor,withintactmuscletissue Hematoma

Laceration:blunttraumafromanexternalfactorwithmuscularrupture Hematoma

Indirect Functional Type1:overload-relatedmuscledisorder

1A:fatigue-inducedmuscle disorder

Musclestiffness Negative

1B:delayedonsetmuscle soreness

Acuteinflammatory pain

Negativeorisolated edema

Type2:muscledisorderofneuromuscularorigin

2A:spine-related neuromuscularmuscle disorder

Increasedmuscletone duetoneurological disorder

Negativeorisolated edema

2B:muscle-related neuromuscularmuscle disorder

Increasedmuscletone duetoaltered neuromuscularcontrol

Negativeorisolated edema

Structural Type3:Partialmuscletear

3A:minorpartialmuscletear:tearinvolvingasmallareaofthemaximalmusclediameter Fiberrupture 3B:moderatepartialmuscletear:tearinvolvingmoderateareaofmaximummusclediameter Retractionand

hematoma

Type4:(sub)totalmuscletearwithavulsion:

Involvementoftheentiremusclediameter,muscledefect Complete

discontinuationoffibers

thanthat observedinfunctional injuries.Withinstructural lesions,significantdifferenceswerealsoobservedinthe sub-groups(minor,moderate,andcompleteinjury);thegreaterthe severity,thelongerthetimetoreturntosport.Inthepresent study,nosignificantdifferenceswereobservedoutcomesof anteriororposteriorthighmuscleinjuries.

Treatment

MostHSlesionsaremusclestrainsorpartiallesionsattheMTJ levelthatcanbeconservativelymanagedandgenerallyresult infullrecovery.14

Intheinitialphase,treatmentaimstominimize intramus-cularbleedingandcontrolinflammatoryresponse.Analgesia, rest,icepacks,musclecompression,andlimbelevationare used.However,clinicalevidencetosupporttheuseofthese treatmentmodalitiesisstilllimited. Thebesttreatmentfor HSinjuriesisyettobeidentified.2,3,7,29

A greater emphasis on pain reduction in the first days afterinjuryisnecessary, becauseit reducesthe neuromus-cularinhibitionassociatedwithpain.Moreover,unnecessary immobilization should be avoided, as it leads to muscle atrophy. With early mobilization through stretching and strengthening exercises, a stable and functional healing is expected.4,7

The inflammatory reaction, triggered in response to injury, is responsible for the onset of tissue repair. How-ever, as a resultof the enzymes released after cell lesion, theprocessalsocausestissuedegradation,which,together with local ischemia resulting from trauma to the blood supply, increases the muscle injury by involving the adja-cent tissue and increasing inflammatory symptoms, such aspain and edema. Anti-inflammatorymedication is indi-catedtomodulatetheinflammatoryresponseandtocontrol pain,allowingearlyinitiationofrehabilitation.Non-steroidal anti-inflammatorydrugsarethemostused,andareindicated

untilthefirst48–72hofthelesion,toavoidinterferingwith tissuerepair.Afterthisphase,analgesicsareusedforantalgic management.2,3,7

Corticosteroidscanalsobeusedforinflammationcontrol, bothorally andintramuscularly.Intralesionadministration, whichmaybeguidedbyUS,isindicatedwhentheacute con-dition doesnotpresent pain improvementandthe patient has difficulty to performthe rehabilitationprogram. How-ever,localuseofcorticosteroidsmayhavedeleteriouseffects on muscle tissue,because they acton collagenbonds and decreasetissuehealing.2,3,7

Treatmentofproximalavulsions

HSlesionsduetoproximaltendonavulsionmayleadto signif-icantsequelae,suchasstrengthdeficitandinabilitytoreturn tosportspracticeatthepre-injurylevel.Surgicalrepairofthe localanatomyisindicatedtoavoidsuchcomplications, espe-ciallyinathletesorphysicallyactivepatients.Inmostsurgical techniquesdescribed,therepairisperformedusinganchors andnon-absorbablesuture.5,11,14,30

Hofmann et al.15 assessed the outcome of conservative treatmentforcompleteproximalavulsionsoftheHS.Atotal of30%ofthepatientswereunabletoreturntothepre-injury levelofsportsactivity,andalmosthalfofthemregrettednot havingundergonesurgicaltreatment.

Barnettetal.14reportedthatgood-to-excellentresultscan beexpectedinmostpatientsaftersurgicalreinsertionof prox-imalavulsionoftheHS.Theseauthorsalsoreportedahigh percentageofpatientswhoreturnedtotheirpre-injurylevel; thevastmajorityofpatientswassatisfiedwithsurgeryand wouldoptforthesametreatmentagain.

Surgicaltreatmentisthebestoptionforischialapophysis avulsionsinskeletallyimmaturepatients,avulsionswiththe HSbonefragment,andproximalavulsionsofthe entireHS complex.16,21

Thesurgeryisalsoindicatedforpatientswithactive avul-sionsinoneortwotendonsandretractiongreaterthan2cm. Inrecreationalathletesorinactivepatients, surgeryis indi-catedonlywhentheavulsionissymptomatic.2,7,11

Surgerymay alsobe indicatedin tendon injurieswhen avulsionis symptomatic, particularly in athletes or highly activepatients.Theoretically,anLHBFavulsionmayrequire surgicalrepair,sincenoothermuscleactsasanagonist,unlike theSTandMS,whichactsynergistically.5,7

Whenthediagnosisofproximalavulsionisconfirmed,the possibilityofsurgicaltreatmentshouldbeaddressedasearly aspossible,inordertorepairthelesionduringtheacutephase. Theconsensusindicatesthatreinsertionshouldideallybe per-formedwithintwoweeksofinjury. Early repairminimizes muscleatrophyandshortening,facilitatesrehabilitation(by makingitmorepredictable), andavoidssurgicaldifficulties andcomplications,suchasadhesionsbetweentheavulsed tissueand thesciaticnerve,whichformaroundtheendof thesecondweek.Inadditiontosciaticnerveinvolvement,the posteriorfemoralcutaneousnerveandlowerglutealnervecan alsobeinvolved,causingdysesthesiaandweaknessofthehip extensors.2,3,5,7,15,16,21

Injuriesthatarenotsurgicallytreatedmayevolvewith neu-ralgiaandsciatica.Surgicalrepairisalsoindicatedinthese chroniccasesandinlesionsthat,despiteconservative treat-ment,persistwithdebilitatingpainandweakness.However, itisworthemphasizingthattheneurologicalsymptomsmay persistafterthesurgicalprocedure.7,16,21

Platelet-richplasma

Myogenyis not restricted toprenatal development; it also occurs in muscle regeneration after injury. Several growth factors have been suggested as regulators of this process. Plateletsareknownfortheirroleinhemostasis,buttheyalso mediate tissueinjury repair, due totheir abilityto release growthfactors,whichleadtothestimulationofangiogenesis (responsibleforneovascularization)andincreasedmetabolic activity,withtendonandmuscletissueproliferation.31

Theindicationfor the use of platelet-rich plasma(PRP) isbasedontheconceptthatthegrowthfactorsreleasedby platelets wouldincrease thenatural healingprocess, espe-cially in tissues with low potential for cure; this claim is supportedbymanyinvitrostudies.Becauseofthepotentialto enhancethetissuerepairprocess,PRPhasbeeninvestigated aspartofthetherapeuticarsenalformanylesions,including thoseoftheHS.3,29,32

Hamidetal.29studied28patientswithacuteHSinjuries classifiedaspartialruptures.Theywererandomlyallocated fortreatment with autologousPRP combined witha reha-bilitationprogram,or forrehabilitationprogramalone. The primaryoutcomeofthestudywasthetimetoreturntosports. Theauthors alsoassessedlevelofpainandinterferenceof painovertime.Thatstudydemonstratedthatasingle injec-tionof3mLofautologousPRPcombinedwitharehabilitation program was significantly more effective in reducing pain

severity, allowingashortertimetoreturntosportafteran acuteHSinjury.

Rossi et al.33 also described a study in which a single application ofautologousPRP associatedwitha rehabilita-tionprogramwascomparedwithrehabilitationprogramalone inpartialHSlesions;theseauthorsobservedasignificantly decrease in timetoreturn tosport in thecombined treat-ment.Attwoyearsoffollow-up,nodifferenceswereobserved betweengroupsregardingrecurrencerate.

Inastudyof25HSinjuriesinprofessionalsoccerplayers, Zanonetal.32demonstratedthattheuseofPRPwassafe;the authors didnotreportadecrease inrecoverytime, butdid show asmaller scarandimprovedtissuerepairintheMRI controlimages.

Reurink et al., 34 ina randomized, multicenter, double-blindedstudywith80recreationalathleteswithHSlesions, didnotobservestatisticallyorclinicallysignificantresultsto justifytheuseofPRP.

InadditiontotheisolateduseofPRP,itsassociationshave alsobeenstudied.Inananimalmodel,Teradaetal.35 demon-stratedthatPRPcombinedwiththeuseoflosartanpromoted animprovementinskeletalmusclehealingaftercontusionby increasingrevascularizationrateandmuscleregeneration,as wellasbyinhibitingthedevelopmentoffibrosis.Losartanhas anantifibroticaction,anditisalsoawidelyused antihyper-tensive.ItsassociationwithPRPwouldstimulateangiogenesis andinhibitthedevelopmentoffibrosis.

Despitethevariousstudies,thereisstillinsufficient evi-dence to indicate the use of PRP in acute muscle injury. Due totheincreaseinpopularity, itsrealeffectivenesshas been increasinglydebated, especiallyregardingthe process ofmuscleinjury rehabilitationinphysicallyactivepatients and in athletes, thus it represents an important area of research.3,4,29,33

Currentliteratureshowspromisingpre-clinicaloutcomes, butclinicalfindingsarecontradictory.Adetailedanalysisis hamperedbythelackofstandardizationofstudyprotocols, PRPpreparationtechniques,andoutcomemeasures.31,36

Highqualitystudiesarecriticaltoconfirmthese prelimi-naryresultsandprovidescientificevidencetoindicatetheuse ofPRP.FurtherresearchisneededtostandardizePRP prepa-ration,administrationregimens(includingthevolumetobe applied),treatmentdurationandfrequency,andapplication method(blindorguidedbyUS).3,31

Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation process is based on muscle stretching and strengthening programs, since tissue healing involves muscle regenerationand fibrosis formation. Early mobility minimizesdisorganizedhealingofthefibersand,therefore, lesionrecurrence.3

Prognostic factorsrelated toalongrehabilitationperiod include muscle injury observed on MRI, extensive lesion demonstratedonMRI,recurrentHSlesions,andindirectinjury asthetraumamechanism.9

torelievepain.Musclestrengtheningisbotharehabilitation andpreventionfactor.2,10

Theprocessbeginswithconcentricstrengthening,which leadstoclinicalimprovement;openkineticchainexercisesare usedprogressivelytoinitiateeccentricstrengthening. Eccen-tricstrengtheningexercisesaremoreeffectivethanconcentric exercises, and should be performed with the muscle in a stretched,astheyhelptorestoremusclelengthafterinjury.2,4

Returntosportspractice

ReturntosportsisthedesiredoutcomeafterHSinjuries. Iso-latedlesionsoftheLHBFinvolving<50%ofthecross-sectional areaandminimumperimuscularedemaarecorrelatedwith arapidreturntosport,usuallywithinsevendays. Delayed return,afterovertwoorthreeweeks,iscorrelatedwithlesions inmultiplemuscles,MTJlesions,lesionsinvolvingtheSHBF, lesionswithacross-sectionalareagreaterthan75%,presence ofretraction,andlesionswithcircumferentialmuscleedema. Adelayintherecoveryprocessisalsoassociatedwithprimary injuryandindirectinjuryasthetraumamechanism.3,37

Thecriteriaforsportsreturnare:absenceofpain,ability to makethe respective sporting movements without hesi-tation, recovery ofstrength and stretching ofthe involved musclegroup,andtheathlete’sownconfidenceforreturning tophysicalactivity.Theassessmentofmusclestrengthcanbe determinedbytheisokinetictest.Restorationoflimbstrength comparedtocontralateral side(between90% and95%)and HS toquadriceps strength ratio between 50% and 60% are desirable.2,7

MostHSrelapses occur atthe same siteastheprimary lesions,earlyafterthereturntosport;thesenewlesionsare radiologicallymoresevere.Specificexerciseprogramsfocused on preventing new injuries are highlyrecommended after returningtosports.19

Prevention

Giventhemajorcomplications ofHS injuries, especiallyin athletes,preventionisstillbetterthantreatmentand rehabili-tationprocess,especiallyconsideringthethreatofrecurrence. Severalstudieshaveaimedtoidentifypatternsthatpredict injury,inordertoavoidorcorrectthesesituations.

Duhigetal.,38whoassessedsoccerplayersandtheirsprints usingGPSdevices,observedthatathleteswhodevelopedHS injurytraveledagreaterdistancethantheirtwo-yearaverage forhigh-speedsprinting(>24km/h)inthefourweekspriorto theinjury.

VanDyketal.10donotrecommendtheisokinetictestto determinetheassociationbetweenstrengthdifferencesand HSinjury,astheywereunabletodeterminethefactorsthat wouldidentifysoccerplayersatriskforinjuryinastudyonthe relationshipbetweentheeccentricHSstrengthandconcentric quadricepsstrengthintheisokineticevaluationof614players overfourseasons.

However,Dautyet al.39 studiedallsoccer playersinthe majorFrenchleaguebetweenthe2001/02and2011/12seasons byisokinetictesting.Accordingtothoseauthors,itispossible

topredicttheoccurrenceofHSinjurybasedontheresultsof thetestconductedatthebeginningoftheseason.

Schacheetal.40 reportedthat theasymmetricmeasures onisokinetictestsofmaximalvoluntarycontractionsofthe HSmusclesmaybeausefulclinicaltesttoidentify suscep-tibility to injury. In the case report of an elite Australian footballplayer,theHSisokinetictestdemonstratedthat,over four weeks, the asymmetrybetween the maximum volun-tarycontractionwasminimal(<1.2%);however,fivedaysprior to the injury, the side that would be affected presenteda reduction in the maximum voluntary contraction force of 10.9%.

Despite thediscrepancybetweenthe differentresultsof thestudies,withvariantmethodologies,muscle strengthen-ingisconsideredtobethemainpreventionfactor.Regarding musclestretching,littlehasbeenshownaboutits prophylac-ticfunction.However,themostenduring clinicalsignafter HS injury isthe reductionof muscleelongation; therefore, stretchingisespeciallyusefulforrehabilitatingtheprimary lesionandpreventingrelapse.HSstretchingwiththepelvisin anteriorinclinationhasbeenshowntobemoreeffectivethan thestandardstretches.2,7

Regarding muscle strengthening, Mendiguchia et al.41 reportedthatsevenweeksofneuromusculartrainingfocusing ontheHS,combinedwithsoccertraining,wasmoreeffective thanisolatedtrainingeffectiveinimprovingconcentric con-tractionforce,specificallyHSeccentricstrength.Thisresult ensuresthattheprogrammaintainstheathlete’sperformance andhelpspreventHSinjuries.

PorterandRushton42conductedasystematicreviewofthe effectivenessofeccentricstrengtheningexercisesinthe pre-ventionofHSinjuriesinmaleprofessionalsoccer athletes. Thoseauthorsconcludedthat,althoughsufficientevidenceis stilllacking,thereisscientificsupportintheliteratureforthe indicationofthispreventionmodality.

Insummary,manyauthorsagreethatanexerciseprogram foreccentricHSstrengtheningmayreducetheincidenceof injury.Theeffectivenessofthoseprogramscanbeexplained by the fact that the injury typically occurs when the HS muscles acton thedecelerationofkneeextensionthrough an eccentric contraction in the final swing phase dur-ing the stride, when they are elongated by hip flexion and knee extension. The force required for the decelera-tion is proportional to the speed and force applied in the sprint.2,4,6

Nordicflexionisconsideredtobeoneofthemosteffective exercisesineccentricHSstrengthening;ithasbeenusedwith goodresultsinprofessionalsoccerteamsandamateur ath-letes.Theexercisebeginswiththeathletekneelingwiththe thighsandtrunkaligned,atarightangletothelegs.A train-ingpartnerhelpsholdthefeetandlegsontheground.The athlete initiatestheactivity bytilting thetrunktowardthe floorasslowlyaspossible,inordertoincreasethemuscular loadduringtheeccentricphase.Whenthetrunkapproaches theground,theupperlimbsareusedtopreventthefalland push theathlete’sback,minimizing theloadingduringthe concentricphase(Fig.2).2,6

Fig.2–Nordicflexion:(a)athleteininitialkneeling

position,(b)athletemakesthetrunkinclinationmovement

towardthegroundasslowlyaspossible,witheccentric

contractionofthehamstrings.

TheyalsoshowedthattheSTisthemostsignificantly acti-vatedmuscle.Regardingtheanalysisbyelectromyography,the samegroup,inadifferentstudy,44observedthat,althoughnot selectiveforLHBF,Nordicflexionpresentedthehighestlevels ofactivationintheeccentriccontractionofthismusclewhen comparedwiththeother exercisesassessedintheir study. ThoseauthorsconcludedthattheHSmusclesareactivated differentlyduringhiporknee-basedexercises.Thus,exercises basedonhipextensionare moreselectiveinlateral activa-tion,whereas thosewithknee flexionpreferentiallyengage themedialmusculature.

Laboratoryparameterscanalsobeusedtopreventinjury. Classically, creatinephosphokinase and lactate dehydroge-naseareusedasbiochemicalmarkers.Serumlevelsdependon age,gender,ethnicity,musclemass,physicalactivity,andeven weatherconditions.Theseparametersshouldnotbeusedfor thediagnosisorprognosisoflesions,duetotheirlow sensitiv-ityandspecificity.However,anincreaseintheseparameters indicatesanincompleterecoveryfromthemuscularoverload whencomparedwiththeathlete’sbaselinemeasurements. Specialattentionshouldbegiventocorrecting factorsthat maypredisposetoinjury.9,45,46

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

ToDr.ElioSteinJuniorandtheInstitutodeJoelhoeOmbro’s physiotherapy team for kindly producing and submitting photosforthismanuscript.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.AgreJC.Hamstringinjuries.Proposedaetiologicalfactors, prevention,andtreatment.SportsMed.1985;2(1):21–33.

2.CarlsonC.Thenaturalhistoryandmanagementofhamstring injuries.CurrRevMusculoskeletMed.2008;1(2):120–3.

3.AhmadCS,RedlerLH,CiccottiMG,MaffulliN,LongoUG, BradleyJ.Evaluationandmanagementofhamstringinjuries. AmJSportsMed.2013;41(12):2933–47.

4.BruknerP.Hamstringinjuries:preventionandtreatment–an update.BrJSportsMed.2015;49(19):1241–4.

5.AsklingCM,KoulourisG,SaartokT,WernerS,BestTM.Total proximalhamstringruptures:clinicalandMRIaspects includingguidelinesforpostoperativerehabilitation.Knee SurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc.2013;21(3):515–33.

6.vanderHorstN,SmitsDW,PetersenJ,GoedhartEA,BackxFJ. Thepreventiveeffectofthenordichamstringexerciseon hamstringinjuriesinamateursoccerplayers:arandomized controlledtrial.AmJSportsMed.2015;43(6):1316–23.

7.LempainenL,BankeIJ,JohanssonK,BruckerPU,SarimoJ, OravaS,etal.Clinicalprinciplesinthemanagementof hamstringinjuries.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc. 2015;23(8):2449–56.

8.EkstrandJ,WaldénM,HägglundM.Hamstringinjurieshave increasedby4%annuallyinmen’sprofessionalfootball,since 2001:a13-yearlongitudinalanalysisoftheUEFAEliteClub injurystudy.BrJSportsMed.2016;50(12):731–7.

9.KerkhoffsGM,vanEsN,WieldraaijerT,SiereveltIN,Ekstrand J,vanDikkCN.Diagnosisandprognosisofacutehamstring injuriesinathletes.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc. 2013;21(2):500–9.

10.vanDykN,BahrR,WhiteleyR,TolJL,KumarBD,HamiltonB, etal.Hamstringandquadricepsisokineticstrengthdeficits areweakriskfactorsforhamstringstraininjuries:a4-year cohortstudy.AmJSportsMed.2016;44(7):95–1789.

11.vanderMadeAD,WieldraaijerT,KerkhoffsGM,KleipoolRP, EngebretsenL,vanDijkCN,etal.Thehamstringmuscle complex.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc. 2015;23(7):2115–22.

12.AsklingCM,TengvarM,SaartokT,ThorstenssonA.Acute first-timehamstringstrainsduringhigh-speedrunning:a longitudinalstudyincludingclinicalandmagneticresonance imagingfindings.AmJSportsMed.2007;35(2):197–206.

13.AsklingCM,MalliaropoulosN,KarlssonJ.High-speedrunning typeorstretching-typeofhamstringinjuriesmakesa differencetotreatmentandprognosis.BrJSportsMed. 2012;46(2):86–7.

14.BarnettAJ,NegusJJ,BartonT,WoodDG.Reattachmentofthe proximalhamstringorigin:outcomeinpatientswithpartial andcompletetears.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc. 2015;(7):2130–5.

afternonsurgicaltreatment.JBoneJointSurgAm. 2014;96(12):1022–5.

16.BirminghamP,MullerM,WickiewiczT,CavanaughJ,RodeoS, WarrenR.Functionaloutcomeafterrepairofproximal hamstringavulsions.JBoneJointSurgAm.

2011;93(19):1819–26.

17.vanBeijsterveldtAM,vandePortIG,VereijkenAJ,BackxFJ. Riskfactorsforhamstringinjuriesinmalesoccerplayers:a systematicreviewofprospectivestudies.ScandJMedSci Sports.2013;23(3):253–62.

18.SvenssonK,EckermanM,AlricssonM,MagounakisT,Werner S.Muscleinjuriesofthedominantornon-dominantlegin malefootballplayersatelitelevel.KneeSurgSports TraumatolArthrosc.2016;(June).

19.WangensteenA,TolJL,WitvrouwE,VanLinschotenR, AlmusaE,HamiltonB,etal.Hamstringreinjuriesoccuratthe samelocationandearlyafterreturntosport:adescriptive studyofMRI-confirmedreinjuries.AmJSportsMed. 2016;44(8):2112–21.

20.PrunaR,ArtellsR,LundbladM,MaffulliN.Genetic biomarkersinnon-contactmuscleinjuriesinelitesoccer players.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc.2016;(April),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-4081-6[Epubaheadof print].

21.CarmichaelJ,PackhamI,TrikhaSP,WoodDG.Avulsionofthe proximalhamstringorigin.Surgicaltechnique.JBoneJoint SurgAm.2009;91Suppl2:249–56.

22.PollockN,PatelA,ChakravertyJ,SuokasA,JamesSL, ChakravertyR.Timetoreturntofulltrainingisdelayedand recurrencerateishigherinintratendinous(‘c’)acute hamstringinjuryinelitetrackandfieldathletes:clinical applicationoftheBritishAthleticsMuscleInjury Classification.BrJSportsMed.2016;50(5):305–10.

23.EkstrandJ,HealyJC,WaldénM,LeeJC,EnglishB,HägglundM. Hamstringmuscleinjuriesinprofessionalfootball:the correlationofMRIfindingswithreturntoplay.BrJSports Med.2012;46(2):112–7.

24.EkstrandJ,AsklingC,MagnussonH,MithoeferK.Returnto playafterthighmuscleinjuryinelitefootballplayers: implementationandvalidationoftheMunichmuscleinjury classification.BrJSportsMed.2013;47(12):769–74.

25.GrassiA,QuagliaA,CanataGL,ZaffagniniS.Anupdateon thegradingofmuscleinjuries:anarrativereviewfrom clinicaltocomprehensivesystems.Joints.2016;4(1): 39–46.

26.PollockN,JamesSL,LeeJC,ChakravertyR.Britishathletics muscleinjuryclassification:anewgradingsystem.BrJSports Med.2014;48(18):1347–51.

27.PeetronsP.Ultrasoundofmuscles.EurRadiol. 2002;12(1):35–43.

28.Mueller-WohlfahrtHW,HaenselL,MithoeferK,EkstrandJ, EnglishB,McNallyS,etal.Terminologyandclassificationof muscleinjuriesinsport:theMunichconsensusstatement.Br JSportsMed.2013;47(6):342–50.

29.AHamidMS,MohamedAliMR,YusofA,GeorgeJ,LeeLP. Platelet-richplasmainjectionsforthetreatmentofhamstring injuries:arandomizedcontrolledtrial.AmJSportsMed. 2014;42(10):2410–8.

30.TanksleyJA,WernerBC,MaR,HoganMV,MillerMD.What’s newinsportsmedicine.JBoneJointSurgAm.

2015;97(8):682–90.

31.KonE,FilardoG,DiMartinoA,MarcacciM.Platelet-rich plasma(PRP)totreatsportsinjuries:evidencetosupportits use.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc.2011;19(4): 516–27.

32.ZanonG,CombiF,CombiA,PerticariniL,SammarchiL, BenazzoF.Platelet-richplasmainthetreatmentofacute hamstringinjuriesinprofessionalfootballplayers.Joints. 2016;4(1):17–23.

33.RossiLA,MolinaRómoliAR,BertonaAltieriBA,BurgosFlor JA,ScordoWE.Doesplatelet-richplasmadecreasetimeto returntosportsinacutemuscletear?Arandomized controlledtrial.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc. 2016;(April),http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-4129-7

[Epubaheadofprint].

34.ReurinkG,GoudswaardGJ,MoenMH,WeirA,VerhaarJA, Bierma-ZeinstraSM,etal.DutchHamstringInjectionTherapy (HIT)studyinvestigatorsplatelet-richplasmainjectionsin acutemuscleinjury.NEnglJMed.2014;370(26):7–2546.

35.TeradaS,OtaS,KobayashiM,KobayashiT,MifuneY, TakayamaK,etal.Useofanantifibroticagentimprovesthe effectofplatelet-richplasmaonmusclehealingafterinjury.J BoneJointSurgAm.2013;95(11):980–8.

36.ShethU,SimunovicN,KleinG,FuF,EinhornTA,Schemitsch E,etal.Efficacyofautologousplatelet-richplasmausefor orthopaedicindications:ameta-analysis.JBoneJointSurg Am.2012;94(4):298–307.

37.ClokeD,MooreO,ShahT,RushtonS,ShirleyMD,DeehanDJ. Thighmuscleinjuriesinyouthsoccer:predictorsofrecovery. AmJSportsMed.2012;40(2):433–9.

38.DuhigS,ShieldAJ,OparD,GabbettTJ,FergusonC,Williams M.Effectofhigh-speedrunningonhamstringstraininjury risk.BrJSportsMed.2016;50(24):1536–40.

39.DautyM,MenuP,Fouasson-ChaillouxA,FerréolS,DuboisC. Predictionofhamstringinjuryinprofessionalsoccerplayers byisokineticmeasurements.MusclesLigamentsTendonsJ. 2016;6(1):116–23.

40.SchacheAG,CrossleyKM,MacindoeIG,FahrnerBB,Pandy MG.Canaclinicaltestofhamstringstrengthidentifyfootball playersatriskofhamstringstrain?KneeSurgSports TraumatolArthrosc.2011;19(1):38–41.

41.MendiguchiaJ,Martinez-RuizE,MorinJB,SamozinoP, EdouardP,AlcarazPE,etal.Effectsofhamstring-emphasized neuromusculartrainingonstrengthandsprintingmechanics infootballplayers.ScandJMedSciSports.2015;25(6): e621–9.

42.PorterT,RushtonA.Theefficacyofexerciseinpreventing injuryinadultmalefootball:asystematicreviewof randomisedcontrolledtrials.SportsMedOpen.2015;1(1):4.

43.BourneMN,OparDA,WilliamsMD,AlNajjarA,ShieldAJ. MuscleactivationpatternsintheNordichamstringexercise: impactofpriorstraininjury.ScandJMedSciSports. 2016;26(6):666–74.

44.BourneMN,WilliamsMD,OparDA,AlNajjarA,KerrGK, ShieldAJ.Impactofexerciseselectiononhamstringmuscle activation.BrJSportsMed.2017;51(13):1021–8.

45.BrancaccioP,MaffulliN,BuonauroR,LimongelliFM.Serum enzymemonitoringinsportsmedicine.ClinSportsMed. 2008;27(1):1–18.