Rita de Cássia Pereira FernandesI

Fernando Martins CarvalhoI

Ada Ávila AssunçãoII

Annibal Muniz Silvany NetoI

I Departamento de Medicina Preventiva e Social. Faculdade de Medicina da Bahia. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Salvador, BA, Brasil

II Departamento de Medicina Preventiva e Social. Faculdade de Medicina. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil

Correspondence:

Rita de Cássia Pereira Fernandes Faculdade de Medicina da Bahia Av. Reitor Miguel Calmon, s/n, Vale do Canela

40110-905 Salvador, BA, Brasil E-mail: ritafernandes@ufba.br Received: 11/6/2007 Revised: 8/11/2008 Approved: 9/29/2008

Interactions between physical

and psychosocial demands of

work associated to low back pain

Interação entre demandas

físicas e psicossociais na

ocorrência de lombalgia

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To examine the interaction between physical and psychosocial demands of work associated to low back pain.

METHODS: Cross-sectional study carried out in a stratifi ed proportional random sample of 577 plastic industry workers in the metropolitan area of the city of Salvador, Northeast Brazil in 2002. An anonymous standard questionnaire was administered in the workplace by trained interviewers. Physical demands at work were self-rated on a 6-point numeric scale, with anchors at each end of the scale. Factor analysis was carried out on 11 physical demand variables to identify underlying factors. Psychosocial work demands were measured by demand, control and social support questions. Multivariate analysis was performed using the likelihood ratio test.

RESULTS: The factor analysis identifi ed two physical work demand factors: material handling (factor 1) and repetitiveness (factor 2). The multiple logistic regression analysis showed that factor 1 was positively associated with low back pain (OR=2.35, 95% CI 1.50;3.66). No interaction was found between physical and psychosocial work demands but both were independently associated to low back pain.

CONCLUSIONS: The study found independent effects of physical and psychosocial work demands on low back pain prevalence and emphasizes the importance of physical demands especially of material handling involving trunk bending forward and trunk rotation regardless of age, gender, and body fi tness.

Systematic literature reviews have found evidences of a relationship between low back pain and material handling including load lifting and carrying, whole-body vibration, frequent trunk bending forward and rotation, and heavy physical exertion.2,5,13,18,22 Several

cross-sectional studies have suggested a relationship between low back pain and static postures (e.g. stand-ing in one place for long periods) and repetitiveness, but the results are so far limited.5,18,22

Psychosocial demands have also been identifi ed as risk factors for low back pain.3,5,6,9,24 Low job satisfaction,

poor social support at work, and high work pace are the risk factors most often mentioned. It is believed that the effect of psychosocial factors on musculosk-eletal disorders is generally partially or completely independent of physical factors.2 Psychosocial

fac-tors are usually described as organizational facfac-tors at work, but according to Huang et al9 (2002), they

refl ect structural aspects of the work process and can be better understood as “qualities of the organizational

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: Analisar a interação entre demandas físicas e psicossociais no trabalho sobre a ocorrência de lombalgia em trabalhadores.

MÉTODOS: Estudo transversal com amostra aleatória, estratificada, proporcional de 577 trabalhadores da indústria de plásticos da região metropolitana de Salvador (BA), realizado em 2002. Questionário padronizado, anônimo, foi administrado no local de trabalho por entrevistadores treinados. As demandas físicas foram medidas pelo auto-registro de trabalhadores com uma escala numérica de seis pontos, com âncoras nas extremidades. A análise de fator foi realizada com 11 variáveis de demandas físicas, a fi m de identifi car os fatores subjacentes. As demandas psicossociais no trabalho foram medidas por meio de questões sobre demanda psicológica, controle e suporte social. Realizou-se análise de regressão logística, utilizando o teste da razão de verossimilhança.

RESULTADOS: A análise de fator identifi cou dois fatores de demandas físicas no trabalho: fator 1, caracterizando manuseio de carga; fator 2, caracterizando repetitividade. Resultados da regressão logística múltipla mostraram que o fator 1 estava associado com lombalgia (OR=2,35, IC 95% 1,50; 3,66). Não houve associação estatística entre demandas físicas e psicossociais no trabalho, mas ambas atuaram de forma independente no desfecho.

CONCLUSÕES: Os achados mostraram que para ocorrência de lombalgias houve efeitos independentes e importantes para demandas psicossociais e físicas no trabalho, com destaque para: manuseio de carga, inclinação e rotação de tronco na ocorrência de lombalgia, mesmo considerando a idade, sexo e condicionamento físico.

DESCRITORES: Estresse Psicológico. Dor Lombar, epidemiologia. Esforço Físico Transtornos Traumáticos Cumulativos. Saúde do Trabalhador. Estudos Transversais.

INTRODUCTION

environment subjectively experienced by workers. In the present study, this distinction was considered and used for defi ning psychosocial factors.

Some models suggest that psychosocial demands infl u-ence the effects of physical demands on the musculo-skeletal system (increasing the duration or intensity of exposure) while others highlight the role of psycho-social demands through the effects of psychological distress (physiological, psychological, and behavioral reactions) that would directly affect the development of musculoskeletal disorders through a neuroendocrine pathway.3,9 Westgaard24 (2000) carried out studies on

a Portuguese version of Karasek’s book,14 translated by Araujo T, 2000. (not published)

to physical demands has been well documented. However, it is not clear whether the associated pain originated in these situations is caused by sustained muscular activity. It is also possible that exposure to psychological stressors exerts a direct effect on workers’ perception and reporting of musculoskeletal symptom. Some models have proposed that individual factors (coping ability and personality type) combined with work organization factors are determinants of the responses to psychological stressors and to their effects on the musculoskeletal system.3,9,22

Karasek et al15 (1998) devised a model for studying job

strain based on the notions of decision latitude (control), psychological demands, and social support at work: I – Control at work refers to the use of skills and decision au-thority; II - Psychological demands include time pressure and level of concentration required, task interruptions and need to wait for other team members to complete one’s job. The control-demand model was expanded by Johnson (1986, referred by Karasek et al15 1998) with

the inclusion of social support, that includes coworker support and supervisor support. This is one of the most widely used models in studies of stress at work.9

These models explaining the role of physical and psychosocial work demands have contributed with knowledge on musculoskeletal disorders in general and specifi cally to the studies on low back pain, recognized as a major public health problem. However, it remains unclear whether there is a synergistic action between physical and psychosocial work demands.

Epidemiologic studies investigating interactions be-tween physical and psychosocial demands associated to low back pain are still scarce in the literature.19,22

The objective of the present study was to assess the interaction between physical and psychosocial work demands associated to the occurrence of low back pain among plastic industry workers.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study including all production workers from maintenance and operation departments of all 14 plastic factories with more than 35 employees in the metropolitan area of the city of Salvador, North-east Brazil, 2002. Workers in administrative depart-ments were excluded. A stratifi ed proportional random sample was selected from 1,177 eligible workers. The proportional stratifi cation is the number of subjects by factory maintaining the same proportion of the target population in the sample.

The minimum sample size was estimated at 557 subjects considering a precision of 4%, a 95% signifi cance level, an expected low back pain prevalence of 50.0% and

a design effect of 1.4. It was decided to sample more than the minimum sample size to include potential refusals. All employees of each company from maintenance and operation departments were eligible. The selected workers who were temporarily away from work were contacted to participate in the study. A total of 577 workers, males and females, were studied.

Data was collected at each participating company during a regular working day. A pre-tested question-naire was used and subjects’ privacy was assured. All interviewers were trained, including explanations of each item of the questionnaire and answer options. They participated in simulated interviews and in a pilot study when they interviewed workers during a working day.

The questionnaire comprised questions about so-ciodemographic factors; occupational history in the current company and former ones, including formal and informal jobs, the regular working day, and the number of hours worked in the last week, questions on physical work demands, information on workstation characteristics; psychosocial demands (Karasek 1985,14

2000a); lifestyle factors including smoking, medicine

consumption, alcohol use and domestic and family responsibilities; physical activities and sports; infor-mation on musculoskeletal disorders; and other health information (e.g. past history of fractures, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypothyroidism.

The questionnaire used for assessing musculoskeletal disorders was a Portuguese translation of the question-naire proposed by Kuorinka & Forcier18 (1995). The

questionnaire is an expanded version of the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ17) with the

inclusion of questions that evaluate severity, duration and frequency of symptoms in all the investigated body areas to improve the specifi city of NMQ.

The outcome included reporting of low back pain or discomfort (pain symptoms, numbness, tingling, burn-ing, and swelling), with or without accompanying pain in other body areas, occurring in the previous twelve months, that lasted at least one week or occurred at least once a month and was not caused by an acute injury, and meeting one of following conditions: current symptom severity rating of 3 or greater (0–5 scale), or sought medical care, missing work (offi cial or unoffi cial), light or restricted work (offi cial or unoffi cial) or changed jobs due to these problems.18

were partly based on the instrument proposed by Cail et al (1995),a and others were specially designed for

this study.

Physical demand items included: repetitive movements with the hands, force exerted with arms or hands, general body posture including sitting, standing, walking, arm posture including hands above shoulder, trunk posture such as trunk bending forward or trunk rotation, material handling, and hand use. Spearman’s rank order correlation coeffi cients were calculated for all 11 physical work demand items, followed by factor analysis that was carried out to identify underlying factors, reduce the number of variables and prevent variable redundancies. The initial extraction was made through the main components of the model and fac-tors were obtained without rotation.16 The resulting

factors were used as the main independent variables for physical work demand.

Psychosocial work demands were measured using the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ14) scales for

psycho-logical demands, decision latitude, and social support. A composite score on “psychosocial demands at work” was obtained based on the scores of all three scales. High psychosocial exposure criteria were high mental demands, low job control, and low social support. At least two of these criteria for high psychosocial expo-sure had to be met to be in this group. Low psychosocial exposure criteria were low mental demands, high job control, and high social support. At least two of these criteria for low psychosocial exposure had to be met to be in this group.7 JCQ questions on job satisfaction

were also included in the study and translated by the main author (RCPF) of this study.

The main independent variable was physical work demands, i.e., the resulting factor 1 from the factor analysis that characterized physical demands of mate-rial handling. Covariates were included in the analysis: psychosocial work demands, the resulting factor 2 from the factor analysis that characterized physical demands of repetitiveness, job dissatisfaction, years of work, work overtime, age, gender, education, marital status, having children younger than two years old, domestic work, body fi tness, obesity or overweight, smoking habit and alcohol use.

The multivariate analysis to test the hypothesis of an existing interaction between physical and psychosocial demands was performed through unconditional logistic regression. The model fi rst included an initial selection of covariates based on the biological plausibility of the involved associations and based on univariate logistic regressions according to the literature available on low back pain. The variables fi rst selected for logistic

regression, using the likelihood ratio test, besides the main independent variable, physical demands of mate-rial handling were psychosocial demands, physical demands of repetitiveness, years of work, job dissat-isfaction, education, obesity or overweight, domestic work, body fi tness, and frequent alcohol consumption. A backward stepwise method was used for variable selection. A confounder was a variable that produced 15% or more change in the measure of the main as-sociation or in the width of the confi dence interval when removed from the maximum model. Interactions were analyzed through the statistical selection of the product term using the likelihood ratio test, one by one, in a model that contained the remaining independent variables and the product term. The product terms selected were included in the maximum model. Effect modifi er would be that making a signifi cant contribu-tion to prediccontribu-tion (α = 0.20) in the likelihood ratio test, corresponding to comparisons between the maximum model and reduced model, in which the product term of the variable under analysis had been deleted. The goodness-of-fi t test and residual analysis were used for logistic regression.8

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Com-mittee of Instituto de Saúde Coletiva at Universidade Federal da Bahia. All participants signed a free consent form before answering the questionnaire. They were informed about the study objectives and public institu-tions involved in this research project and interviewers assured them that their employers were contacted to allow their access to the workplaces but that their em-ployers were not involved in this research. This aspect was considered particularly relevant for controlling information bias. They were also explained the study confi dentiality and non-identifi cation of information, and voluntary participation.

RESULTS

Males accounted for 69.0% of the sample. The preva-lence of low back pain was 21.2% among women and 21.4% among men.

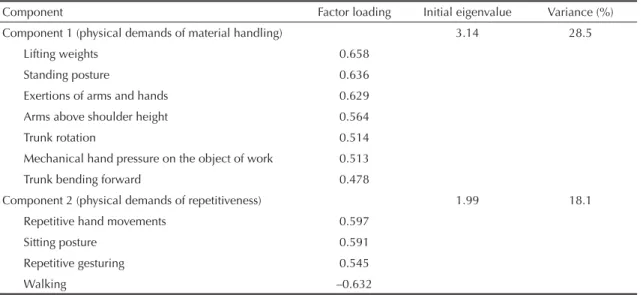

The factor analysis with 11 variables of physical ex-posure resulted in two factors. Their composition, in a decreasing order of the loads presented by each vari-able, was as follows (Table 1): Factor 1 characterized physical demands of material handling and correlates: lifting weights, standing posture, exertions of arms and hands, arms above shoulder height, trunk rotation, me-chanical hand pressure on the object of work, and trunk bending. Factor 2 characterized static trunk posture during repetitive work with the hands: repetitive hand movements, sitting posture, no walking.

Table 2 shows that workers exposed to physical demands of material handling (manual material handling) were more likely to have higher education, were predominantly married or lived with partner. There were no differences between exposed and non-exposed workers to physical demands of material handling regarding age, frequent alcohol consump-tion, gender, smoking habit, body fi tness, and obesity or overweight. There were no differences between exposed and non-exposed to physical demands of material handling as for domestic work, overtime, and exposure to physical demands of repetitiveness (physical demands of repetitiveness, factor 2). How-ever, exposed workers had higher job dissatisfaction, reported higher psychosocial demands and more years of work. The distribution of covariates according to exposure status was assessed to identify potential confounders or effect modifi ers.

Prevalence, prevalence ratios and 95% confi dence intervals for isolated and combined effects of physical work demands of material handling and psychosocial demands on low back pain are described in Table 3. In spite of higher prevalence of low back pain in the presence of the two exposures, the results did not show any interaction.

Tables 4 and 5 show the results of the multiple logis-tic regression analysis. The goodness-of-fi t test and residual analysis showed a good adjustment of the

fi nal model.

No interaction between physical and psychosocial demands (likelihood ratio test, p>0.20) was found (Table 5). Low back pain was 2.35-fold more likely in those exposed at higher levels to physical demands of material handling than those exposed at lower levels (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Physical work demands were positively associated with low back pain. The study fi ndings do not support the hypothesis that psychosocial work demands interact on a multiplicative or additive scale with physical demands causing low back pain. These demands, psychosocial and physical, are independent associated factors with low back pain.

Exploring interaction is very important in the study of musculoskeletal disorders, but few studies have focused on it.22 Although how these risk factors

inter-act remains as a contemporary issue,19,20 studies have

not shown a statistic interaction between physical and psychosocial work demands and the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders. Advances have been made, especially showing an association between psychoso-cial demands and musculoskeletal disorders, and in measuring the exposure to physical work demands. However, these demands have been mostly identifi ed as independent risk factors for low back pain, as cor-roborated in the present study.

Huang et al (2003)10 found independent effects of

psychosocial and physical demands and they “empha-size the need to consider both biomechanical factors and specifi c work organization factors, particularly time pressure, in reducing musculoskeletal-related morbidity”.

Non-occupational covariates, such as sociodemo-graphic (age, education, gender, marital status), lifestyle and domestic work variables, and physical activity, were included in the analysis. This is a strength of this study as the literature3,4,22 shows that most studies on

musculoskeletal disorders have neglected these poten-tial confounders.

Table 1. Results of factor analysis of physical work demands. Salvador, Northeast Brazil, 2002.

Component Factor loading Initial eigenvalue Variance (%)

Component 1 (physical demands of material handling) 3.14 28.5

Lifting weights 0.658

Standing posture 0.636

Exertions of arms and hands 0.629

Arms above shoulder height 0.564

Trunk rotation 0.514

Mechanical hand pressure on the object of work 0.513

Trunk bending forward 0.478

Component 2 (physical demands of repetitiveness) 1.99 18.1

Repetitive hand movements 0.597

Sitting posture 0.591

Repetitive gesturing 0.545

Bongers et al (1993)3 pointed out to the need of

analyz-ing the concurrent effect of psychological demands, control and social support. The validity of studies that

analyzed the effect of physical demands on low back pain without taking into account psychosocial demands are deeply questioned.

Table 2. Exposed and non-exposed workers according to of sociodemographic, lifestyle, domestic work, and occupational

variables. Salvador, Northeast Brazil, 2002.

Variable

Physical demands of material handling

Exposed n=285 Non-exposed n=284 p-value

n % n %

Age

≤30 144 50.5 155 54.6 0.33

>30 141 49.5 129 45.4

Education (years)

≥11 182 63.9 149 52.5 0.01

<11 103 36.1 135 47.52

Alcohol consumption

<1 time/week 182 64.1 177 63.4 0.73

≥1 time/week 102 35.9 102 36.6

Gender

Male 205 71.9 187 65.8 0.11

Female 80 28.1 97 34.2

Smoking

No 253 88.8 247 87.0 0.51

Yes 32 11.2 37 13.0

Body fi tness

Good to excellent 140 49.3 136 48.1 0.76

Poor to moderate 144 50.7 147 51.9

Marital status

Single or living alone 98 34.4 125 44.2 0.01

Married 187 65.6 158 55.8

Overweight or obesity

No 177 63.4 180 66.9 0.50

Yes 102 36.6 89 33.1

Hours of domestic work

<15 212 74.6 229 80.6 0.09

≥15 72 25.4 55 19.4

Job dissatisfaction

No 141 50.4 179 63.9 0.02

Yes 139 49.6 101 36.4

Psychosocial demands

No 110 42.8 147 57.2 0.02

Yes 164 60.1 109 39.9

Physical demands of repetitiveness

No 133 46.80 151 53.2 0.14

Yes 152 53.3 133 46.8

Years of work

<13 124 43.8 147 52.5 0.05

≥13 159 56.2 133 47.5

Overtime

No 86 30.3 82 28.9 0.58

The questions used to measure exposure to physical work demands allowed obtaining a measure of expo-sure for each subject by using a numeric six-point scale with anchors at the end of the scale. This scale does not require the absolute measure of exposure, which is diffi cult to be being quantifi ed by the worker, but it indicates the highest and the lowest level of exposure through the anchors. The most general formulation of the questions (“repetitive movements”, “exertions of arms and hands”) seems to have allowed workers to give the best answers concerning their perception about the exposure. This option aimed to minimize validity problems that have been identifi ed in some questions and their response scales, as Stock et al (2005)23 have suggested in their systematic review on

reproducibility and validity of questions measuring physical work demands.

Material handling is referred as a paramount risk factor to low back pain, as well as frequent trunk bending

forward and rotation. However, evidences of the as-sociation between low back pain and repetitiveness are not consistent.22 The results of the present study

corroborate the literature: low back was associated with physical demands of material handling but not with physical demands of repetitiveness in the multivariate

fi nal model. Only the covariate psychosocial demands remained in the fi nal model, besides physical demands of material handling, as a predictor of low back pain. These results support the idea that intervention pro-grams should seek to reduce exposure to material handling and consequently prevent low back pain. Longitudinal studies confirmed that psychosocial factors are major determinants of subsequent low back pain. High psychological demand (high pace of work), low social support, and low job satisfaction are more strongly associated to low back pain than low control.22 In the present study, there was no

inter-action between physical and psychosocial demands,

Table 3. Prevalence, prevalence ratios and 95% confi dence intervals for the combined effects of physical and psychosocial work demands on low back pain. Salvador, Northeast Brazil, 2002.

Variable n Prevalence (%) Prevalence ratio 95% CI

PDMH=0, PD=0 147 10.2 1.00

-PDMH=0, PD=1 109 19.1 1.87 (1.01;3.46)

PDMH=1, PD=0 164 22.0 2.16 (1.19;3.91)

PDMH=1, PD=1 110 34.8 3.41 (2.02;5.75)

PDMH: Physical demands of material handling 0= lower exposure, 1=higher exposure PD: Psychosocial demands 0= low psychosocial exposure, 1=high psychosocial exposure

Table 5. Results of the logistic regression on the association between physical work demands and low back pain. Salvador, Northeast Brazil, 2002.

Final model/Variable (n=530) OR (95% CI) 1-β

Dependent: low back pain

Independent: physical demands of material handling 2,35a (1,50;3,66) >99%

a Result adjusted for psychosocial demands.

Table 4. Interaction analysis in logistic regression of physical work demands and psychosocial demands on low back pain, Salvador, Northeast Brazil, 2002.

Model / Variable –2 log L d.f. model Likelihood ratio testχ2

Maximum model

Dependent: low back pain

Independent: physical work demands of material

handling, psychosocial demands, PDMH x PDa 530.924 3 28.609

Model after removing product term (PDMH x PDa)

Dependent: low back pain

Independent: physical work demands of material

handling, psychosocial demands 530.967 2 28.566

a Complete model includes the potential factor for interaction, psychosocial demands, with the corresponding product term;

χ2 = chi-square; p>0.20. No interaction was found.

but both physical and psychosocial demands were independently associated to low back pain. The fi nd-ing of the association between psychosocial demands and musculoskeletal disorders is consistent with that reported in the literature.12,21,22

The present study determined the prevalence of low back pain in occupational active workers, providing an estimate of morbidity concurrently occurring with daily work activities.

Health information based on workers’ self-report, a common procedure in epidemiologic studies, can motivate some criticism concerning loss of objectiv-ity. However, self-reporting is the main approach to study symptomatic disorders, especially considering the subjective nature of symptoms of low back pain. Other methods of clinical evaluation such as physi-cal examination have also limitations. The physiphysi-cal examination does not always allow a diagnosis and its validity can be questioned as there is no gold standard method for comparison.1

Considering the particular characteristics and the nature of relationships in the work environment, it is neces-sary to consider that such confl icting relationships can compromise the validity of data. In this event, morbid-ity may be overestimated, as well as exposure, when workers negatively evaluate work conditions. This is a potential limitation of the present study. However, some procedures were adopted during data collection to minimize information bias. All subjects were informed about the independence of the research study and in-vestigators from their employers and that the study was sponsored by public agencies. Assuring privacy and anonymity contributed to avoid information bias. In the

questionnaire, questions on the main dependent variable – presence of musculoskeletal disorders – were followed by other several questions on morbidity, such as the presence of other diseases, to minimize the likelihood of workers associating musculoskeletal disorders as the main focus of the study related to their occupation. A selection bias, the healthy worker’s effect, could have distorted the study fi ndings. However, bias due to healthy recruiting is unlikely to be relevant since only internal comparisons to the studied population were performed. Survival healthy worker’s effect could occur due to 1) transference of workers from one to another occupation, inside the company; 2) sick leave; or 3) worker’s dismissal. To minimize bias due to sick leave, the study population included all employed workers, either in activity or temporarily away from work for sick leave.

Therefore, results support the recommendation of changes in work organization, including management choices, supervision methods, work teams, especially ensuring cooperative work with social support, reduc-tion of work pace, and increased workers’ control of work conditions, to reduce disease burden of occupa-tional low back pain.11

Intervention programs to reduce occupational risk fac-tors can stop the progress of low back pain to disability and more severe disorders that prevent individuals from working.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Baron S, Hales T, Hurrel J. Evaluation of symptom 1.

surveys for occupational musculoskeletal disorders.

Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):609-17. DOI: 10.1002/ (SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<609::AID-AJIM5>3.0.CO;2-E

B

2. ernard BP, editor. Musculoskeletal disorders and

workplace factors: a critical review of epidemiologic evidence for work related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, upper extremity, and low back. Cincinnati, Oh: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 1997. (NIOSH publication, 97-141).

Bongers PM, de Winter CR, Kompier MA, 3.

Hildebrandt VH. Psychosocial factors at work and

musculoskeletal disease. Scand J Work Environ

Health. 1993;19(5):297-312.

B

4. uckle PW. Work factors and upper limb disorders.

BMJ. 1997;315(22):1360-3.

Burdorf A, Sorock G. Positive and negative evidence of 5.

risk factors for back disorders. J Work Environ Health.

1997;23(4):243-56.

Devereux JJ, Buckle PW, Vlachonikolis I. Interactions 6.

between physical and psychosocial risk factors at work increase the risk of back disorders: an epidemiological

approach. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56(5):343-53.

Devereux JJ, Vlachonikolis IG, Buckle PW. 7.

Epidemiological study to investigate potential interaction between physical and psychosocial factors at work that may increase the risk of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorder of the neck and upper

limb. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59(4):269-77. DOI:

10.1136/oem.59.4.269

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 8.

New York: Wiley Interscience; 2000.

Huang GD, Feuerstein M, Sauter SL. Occupational 9.

stress and work-related upper extremity disorders:

concepts and models. Am J Ind Med.

2002;41(5):298-314. DOI:10.1002/ajim.10045

Huang GD, Feuerstein M, Kop WJ, Schor K, Arroyo F. 10.

Individual and combined impacts of biomechanical and work organization factors in work-related

musculoskeletal symptoms. Am J Ind Med.

2003;43(5):495-506. DOI: 10.1002/ajim.10212

Huang GD, Feuerstein M. Identifying work 11.

organization targets for a work-related

musculoskeletal symptom prevention program. J

Occup Rehabil. 2004;14(1):13-30. DOI:10.1023/ B:JOOR.0000015008.25177.8b

Ijzelenberg W, Molenaar D, Burdorf A. Different 12.

risk factors for musculoskeletal complaints and

musculoskeletal sickness absence. Scand J Work

Environ Health. 2004;30(1):56-63.

Jansen JP, Morgenstern H, Burdorf A. Dose response 13.

relations between occupatinal exposures to physical and psychosocial factors and the risk of low back

pain. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(12):972-9. DOI:

10.1136/oem.2003.012245

Karasek R. Job Content Instrument: questionnaire 14.

and user’s guide. Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Amherst; 1985.

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, 15.

Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative

assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J

Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322-35. DOI: 10.1037/1076-8998.3.4.322

K

16. leinbaum, DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE. Applied regression analysis and other multivariabel methods. Boston: PWS-Kent; 1988.

Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-17.

Sørensen F, Andersson G, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal

symptoms. Appl Ergon. 1987;18(3):233-7. DOI:

10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X

Kuorinka I, Forcier L, editors. Work related 18.

musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs): a reference book for prevention. London: Taylor & Francis; 1995.

Marras WS, Cutlip RG, Burt SE, Waters TR. National 19.

occupational research agenda (NORA) future directions in occupational musculoskeletal disorder

health research. Appl Ergon. 2008;40(1);15-22. DOI:

10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.018

Martin F, Matthias P. Factors associated with the 20.

subject’s ability to quantify their lumbar fl exion

demands at work. Int J Environ Health Res.

2006;16(1):69-79. DOI: 10.1080/09603120500398522

Nahit ES, Hunt IM, Lunt M, Dunn G, Silman AJ, 21.

Macfarlane GJ. Effects of psychosocial and individual psychological factors on the onset of musculoskeletal

pain: common and site-specifi c effects. Ann Rheum

Dis. 2003;62(8):755-60. DOI:10.1136/ard.62.8.755

National Research Council; Institute of Medicine. 22.

Musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace: low back and upper extremities. Panel on musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace. Washington, DC: National Academy; 2001.

Stock S, Fernandes RCP, Delisle A, Vézina N. 23.

Reliability and validity of workers’ self-reports of

physical work demands. Scand J Work Environ Health.

2005;31(6):409-37.

Westgaard RH. Work-related musculoskeletal 24.

complaints: some ergonomics challenges upon the

start of a new century. Appl Ergon. 2000;31(6):569-80.

DOI: 10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00036-3

REFERENCES