2018;26e2968

DOI: 10.1590/1518-8345.2099.2968 www.eerp.usp.br/rlae

Cross-cultural validation of the Child Adolescent Teasing Scale for

Colombian students

Objective: to carry out the cross-cultural validation of the instrument “Child Adolescent Teasing

Scale” for the Colombian student population. Method: methodological study carried out with

students aged 8 to 15, from public and private educational institutions in the municipality of

Ibagué, Colombia. The form for the characterization of students and the Child Adolescent Teasing

Scale were used. Results: the cross-cultural adaptation process was organized in seven steps:

comparison of the Spanish version of the instrument with the original English version,

back-translation, consensus version, face validity and terminology adjustment by students, face and

content validity by experts, assessment committee for the final version, pilot test and reliability.

Conclusion: the version adapted to the Spanish spoken in Colombia of the Child Adolescent Teasing

Scale (Escala de burlas para niños y adolescentes), which assesses the frequency and distress

caused by teasing, showed desirable results in terms of validity and reliability.

Descriptors: Bullying; Validation Studies; Surveys and Questionnaires; School Nursing; Nursing;

Nursing Methodology Research.

How to cite this article

Briñez Ariza KJ, Caro Castillo CV, Echevarria-Guanilo ME, Do Prado ML, Kempfer SS. Cross-cultural validation

of the Child Adolescent Teasing Scale for Colombian students. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2018;26e2968.

[Access ___ __ ____]; Available in: ___________________ . DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2099.2968

year day

month URL

Karol Johanna Briñez Ariza

1Clara Virginia Caro Castillo

2María Elena Echevarría-Guanilo

3Marta Lenise Do Prado

4Silvana Silveira Kempfer

51 MSc, Nursing. Doctor Degree Student, Nursing, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Bog, Colombia. Researcher. Doctor Degree

Sponsorship: Beca Colciencias Colombia para el Doctorado en Enfermeria.

2 PhD. Full Professor, Nursing, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Bog, Colombia. 3 PhD, Nursing. Professor, Nursing, Universidad Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, SC, Brazil.

Introduction

Research in pediatric and adolescent nursing

seeks to deepen the knowledge of phenomena related

to health care by promoting studies that fill the gaps identified in the scientific literature and that aim to

contribute to: new perspectives and alternatives for

the resolution of problems affecting their health and

welfare, as well as the welfare of their family.

One of the most prevalent phenomena in today’s

society, first described more than three decades ago, is the bullying among students. It is defined as the

exposure of a student to the repetitive negative actions

by another or more students, or difference in power,

with the intent to cause damage or discomfort through

words, physical contact or other forms, such as gestures,

exclusion and defamation(1-2).

The American National Association of School Nurses

defines bullying as persistent and repetitive dynamic

patterns of verbal and/or nonverbal behaviors directed

by one child or more children to another, who deliberately

attempt to cause physical, verbal or emotional abuse in

the presence of actual or perceived difference in power(3).

It has been associated with a number of damages

and consequences for the health of children and

adolescents, and has become internationally recognized

as a public health problem(4).

The problem mentioned above has negative

consequences for victims, such as inability to defend

themselves, powerlessness, sadness, crying, fear, loss

of concentration and suicidal ideation(5). Depression,

anxiety and low self-esteem affect normal development

in learning processes and their integration and adaptation

in the school setting(6). Association between bullying

and different variables: Depression (p<0.01)(7)

, sleep

problems (p<0.05), nervousness (p<0.05), restlessness

(p<0.05), feelings of discomfort (p<0.05) and dizziness

(p<0.05)(8). Psychosomatic disorders in victims

(p=0.0001)(9). Physical injuries (p<0.001), symptoms of

illness (p<0.001) and somatic complaints (p<0.001)(10).

Chromosomal changes in the telomeres (p=0.020), which

are biomarkers of childhood stress and cell aging(11).

According to this scenario, it is necessary to

implement strategies through assessment methods for the

early identification of students who experience teasing,

because of their risk of becoming victims of bullying.

There are several instruments, such as the

Questionnaire for the Ombudsman’s report on school

violence(12) and the “Bullying-Cali”(13), used for older

schoolchildren.

Many of the instruments originally available were

published in languages other than Spanish, which

requires for the study in the Colombian context that the

instruments be submitted to the processes of cultural

adaptation, through the development of the translation

and validation stages(14). Thus, the instrument can be

used in a different culture from which it was developed.

In this way, an instrument that could be used for

students from the age of eight and that assessed the

causes of teasing in all risk categories was searched,

and these criteria have been met by the Child Adolescent

Teasing Scale(15).

For the reasons described above, this study aimed

to answer the question: What is the validity of the Child

Adolescent Teasing Scale for the Colombian student

population? It has been proposed in order to: determine

the validity of the Child Adolescent Teasing Scale for the

Colombian student population.

Method

This is a methodological study developed with

students aged from 8 to 15, from public and private

educational institutions in the municipality of Ibagué,

Tolima (Colombia). Inclusion criteria: belong to the

grades between the third grade of elementary school

and the eighth grade of secondary school, and present

the authorization signed by their parents.

Description of the instruments. Two instruments

were applied: The form for the characterization of

students and the Child Adolescent Teasing Scale.

Form for the characterization of students

Developed by the main author, it asked about

variables such as sex, age, grade, type of educational

institution; it was applied during the stages of meeting

with the students: focal groups for the version by

students and pilot test.

The Child Adolescent Teasing Scale (CATS)

It is composed of 32 items and assesses four teasing

categories: physical aspect (items 11 and 21), personality

and behavior (items 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 12, 16, 20, 22, 24, 26,

27, family and home environment (items 2, 9, 10, 17,

19, 25, 29), and school-related factors (items 4, 5, 13,

14, 15, 18, 23, 28, 32). These categories are organized

into two subscales: frequency and distress. The frequency

item is assessed on a Likert-type scale, with the following

response options: never (1) sometimes (2) often (3) and

very often (4). The distress subscale assesses how much

it bothers to be teased, and each item is assessed on a

Likert-type scale, with the following response options: not

at all (1), very little (2), more or less (3), very much (4).

This scale scores values ranging from 32 to 128 for each

subscale and from 64 to 256 for the full scale. The higher

the value, the greater the teasing experienced by children

and adolescents at school.

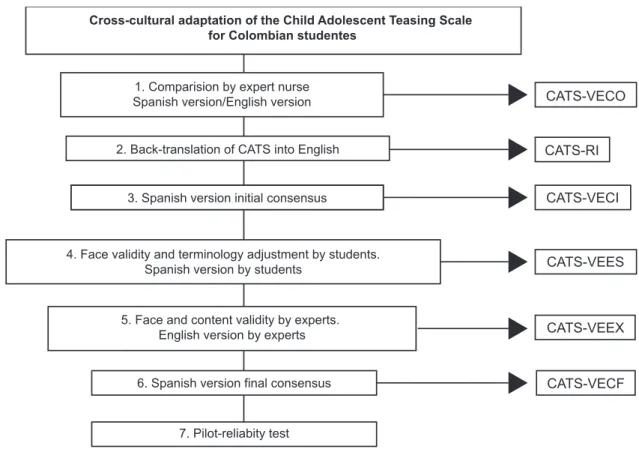

Cross-cultural adaptation process

The cross-cultural adaptation process was

organized into seven stages(14): Comparison of the

Spanish version of CATS with the original English version,

back-translation, consensus version, face validity and

terminology adjustment by students, face and content

validity by experts, assessment committee for the final version, pilot test and reliability (see figure 1).

Comparison of the Spanish version of CATS with

the original English version. The author received the

authorization, the original English version and a Spanish

version, which was translated by her for Mexico and

Puerto Rico. The objective was to make the necessary

adjustments of CATS to the Spanish spoken in Colombia.

Words and sentences were compared. A nurse with a

good command of the English and Spanish languages

and expertise in the validation of assessment instruments

participated in this stage (CATS-VECO).

Cross-cultural adaptation of the Child Adolescent Teasing Scale for Colombian studentes

1. Comparision by expert nurse Spanish version/English version

2. Back-translation of CATS into English

3. Spanish version initial consensus

5. Face and content validity by experts. English version by experts

7. Pilot-reliabity test 6. Spanish version final consensus 4. Face validity and terminology adjustment by students.

Spanish version by students

CATS-VECO

CATS-RI

CATS-VECI

CATS-VEES

CATS-VEEX

CATS-VECF

Figure 1 – Process of cross-cultural adaptation of CATS to the Spanish spoken in Colombia, 2015-2016

Back-translation. The objective was to translate the

version resulting from the first stage into the original

language of the instrument. This procedure was carried

out by an English native speaker translator who

back-translated it from Spanish into English (CATS-RI).

Initial consensus version (CATS-VECI). The objective

was to define a version for students that included the

adjustments recommended in the two previous stages

(CATS-VECO and CATS-RI). It was achieved through a

meeting between the supervisor of the doctoral thesis,

the principal researcher and the nurse who participated

in the first stage for the consensus version.

Face validity and terminology adjustment by students.

The objective was to get the verbal manifestations of “how

students aged 8 to 10 spoke and said those phrases” in

their everyday Colombian language, so that the scale could

be understood by older students. This was accomplished

through a qualitative strategy according to the target

population, through five focal groups and by presenting

transitional and key questions were applied. It was

concluded with refreshments served to the participants and

feedback. Audio recording and transcription were performed

for analysis. Changes were made and the modified version

was proposed (CATS-VEES).

Face and content validity by experts. The objective

was to get the assessment of CATS by six experts from

Colombian Universities with experience in adapting

assessment instruments, professional experience and

experience in pediatric research and bullying. Each

expert completed the “expert judgment” form(16),

which contained a consent for its use, and assessed five categories regarding content validity: semantic

equivalence, clarity, consistency, relevance and adequacy with scores ranging from 1 (does not fulfill its function) to 4 (high level of qualification). As for face

validity, the writing, precision and clarity of language of

each item were evaluated, with a score of 0 (does not fulfill) and 1 (fulfill). This has allowed for suggestions that resulted in a modified version (CATS-VEEX).

Final consensus version (CATS-VECF). The objective

was to make the decisions for the adjustment of the items, according to the suggestions made in the fourth and fifth

stages. Consensus was reached by a committee composed

of the main researcher, the supervisor of the thesis due to

her professional experience with students, and a statistician

who performed and interpreted the Kappa statistical test.

The interpretation of the results of Kappa test was based

on a theoretical reference(17), where the strength of the

Kappa coefficient is as follows: poor (0.00); slight

(0.01-0.20); fair (0.21-0.40); moderate (0.41-0.60); substantial

(0.61-0.80); almost perfect (0.81-1.00).

Pilot test. The objective was to check the

understandability of the items and instructions for

completing the instruments, calculation of completing

time, need for help, and materials to make the pertinent modifications and corrections. The main researcher and

the research assistant provided a CATS scale and a black

pen for each student, which was positioned in a separate

and individual place. For reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was

calculated. Values higher than 0.50 were considered as

high (possible variation from 0 to 1)(18).

Ethical considerations

According to Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian

Ministry of Health, this research was considered to be

of minimal risk. The Ethical Committee of the Faculty of

Nursing of the National University of Colombia approved the

study, and authorization to perform it was obtained from the

Health and Education Secretariat of Ibagué. Authorizations

were requested to the parents of the students through

informed consent, and to the students through an informed

consent, and authorizations were also requested to the

professionals to participate.

Results

Comparison of the Spanish version of CATS

The original English version was compared with the

Spanish version, generating a version for students

(CATS-VECO). The adjustments were made in the instructions

and statements that contained the words “to bother” and

“to annoy”; which were replaced by “to tease”, the word

most used in Colombia. The terminology was considered

understandable, however, it was considered important

that the instrument was submitted to face validity by

Colombian students.

Face and content validity by students

The focal groups consisted of 42 students aged

8 to 10, from the third grade of elementary school of

a public educational institution in Bogotá, with low

socioeconomic status, of which 11 were female and 14

male; and of a private educational institution of Ibagué,

with high socioeconomic status, of which nine were

female and eight were male.

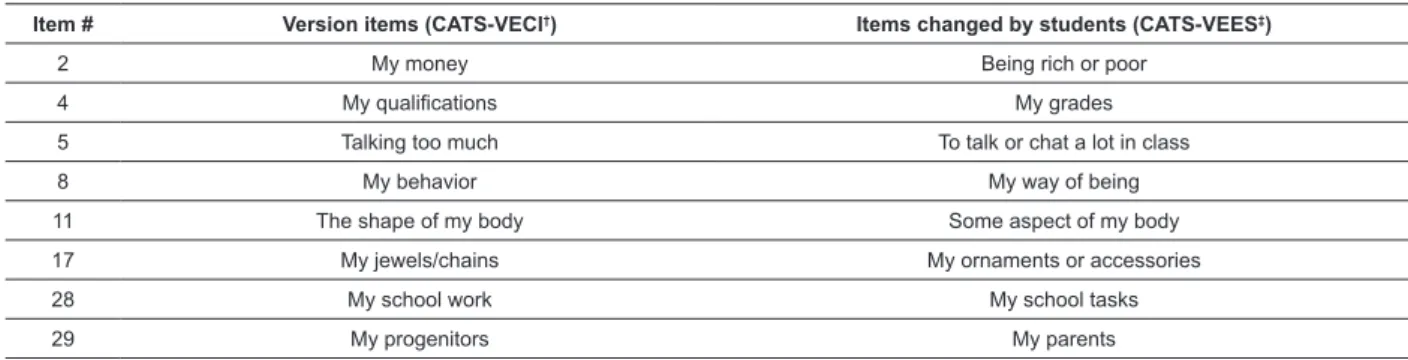

The 32 items (CATS-VECO) were presented to the

students and adjusted to their language according to their

everyday speech. The proposals by the focal group were

put to the vote, and during the discussion, they decided

which phrase was the clearest and most appropriate. The

statements of eight items were not changed because they

were easily understood. All the words in the statements of

eight other items had to be replaced by synonyms most

commonly used in Colombia (Table 1).

The remaining 16 items required adjustment of

the words in the statements, resulting in a different

and more updated wording, or the addition of a word

suggested as a synonym, or adjustments to indicate

that it was related to something specific. The

Table 1 – Change of all 8-item words of the Spanish version of CATS*, Bogotá and Ibagué, Colombia, 2015-2016

Item # Version items (CATS-VECI†) Items changed by students (CATS-VEES‡)

2 My money Being rich or poor

4 My qualifications My grades

5 Talking too much To talk or chat a lot in class

8 My behavior My way of being

11 The shape of my body Some aspect of my body

17 My jewels/chains My ornaments or accessories

28 My school work My school tasks

29 My progenitors My parents

*CATS: Child Adolescent Teasing Scale. †CATS-VECI: Spanish version initial consensus. ‡CATS-VEES: Spanish version by students.

Table 2 – Adjustments suggested by students of some words in the 16 statements of the items of CATS*. Bogotá and

Ibagué, Colombia, 2015-2016

Item # Version item (CATS-VECI†)

Items changed by students (CATS-VEES‡) Item #

Version item (CATS-VECI†)

Items changed by students (CATS-VEES‡)

3 “How intelligent and prepared I am”

“How intelligent I am”; 20 “For being studious” “For being a nerd or studious”

9 “The brand of shoes

that I use” “The brand of my shoes” 22 “For being a coward” “For being a coward or a chicken”

10 “With whom I live” “People that I live with”; 23 “How well I do at school” “How well I do in the studies”

12 “Behave myself

strangely or differently” “Behave myself differently”

25 “My things” “My things or personal items”

14 “My way of speaking” “My way to speak” 25 “Be a fool” “They tell me that I am a fool or a

loser”

15 “Get in trouble” “Get into a tight spot” 27 “Be shy or too quiet” “Be shy or quiet”

16 “Behave myself as gay” “They tell me that I am gay or lesbian”

30 “The music that I like to

listen to” “The music that I like”

19 “How my family is “My family” 32 “Sports I participate in and

do not participate in” those that I do not practice or play”“Sports that I practice or play and

*CATS: Child Adolescent Teasing Scale. †CATS-VECI: Spanish version initial consensus. ‡CATS-VEES: Spanish version by students.

Validity by experts

The CATS-VECO and CATS-VEES versions

were provided to the selected experts. Among the

assessments, three items required clarity and wording

adjustment: from “too much talking” to too much

talk, “my jewels/chains” to my accessories and “get in

trouble” to get into a tight spot. Three items were not

clear to the experts, but to students, “Not being good at

sports” “Shy or quiet” and “Having strange or different

friends”. The experts approved the 16 items changed in

the wording by students.

The Kappa index showed substantial agreement

for the indicators: semantic equivalence: 0.72, clarity

0.65, consistency 0.71, relevance 0.79; and moderate

agreement in the adequacy indicator: 0.56. Regarding

face validity, the agreement percentage among experts

was calculated and showed that 84.9% of the items

complied with the wording, accuracy and clarity in

relation to the language. Based on these results, the

CATS-VEEX version was proposed.

Final consensus version

The necessary adjustments were made after

identifying the items that were recognized by students

as semantically different, but that did not alter their

conceptual equivalence. In addition, the items were

compared with the assessments made by experts in

order to proceed the necessary adjustments of CATS,

which would be used in the main study. No items were

removed. The CATS-VECF version was proposed.

Pilot test

In this process, 19 students aged 11 to 13,

from the sixth grade of elementary school of a private

educational institution of Ibagué, with medium

male, participated. The understandability of the items

and the ease of completion by students was confirmed

and the time spent for completing it ranged from 10 to

15 minutes. In this stage, the reliability of the scale was

calculated using the Cronbach’s alpha, with a result of

0.89 for the frequency subscale, 0.95 for the distress

subscale, and 0.95 for the full scale. These values were

considered as high(18).

Discussion

Nursing is a discipline called to work on the

phenomenon of teasing and bullying, as stated by the

National Association of School Nurses of the United

States(19). It plays an important and decisive role in

the early identification and implementation of bullying

prevention strategies by screening the cases with this

kind of problem and, therefore, helping to promote the

health of students and their families.

Scientific literature describes several instruments

used in research, but few with validity and reliability.

For this reason, the cross-cultural adaptation of a

nursing measurement instrument was carried out, which

measures the frequency of teasing and how much it

bothers the student who receives it, and an appropriate

methodological quality has been demonstrated(20-22).

In the process of cross-cultural adaptation of CATS, a scientific and suggested methodology was

used to ensure the comparability between the results of

Colombian students and those of previous versions(14,22).

The qualitative strategy with the focal groups was

fundamental to achieve, among the Colombian students

aged 8 to 10 years, with different socioeconomic status

and type of educational institution, the understandability

of CATS by older students. For this reason, the age

interval for application of the instrument was enlarged,

ranging from 8 to 15 years in the present study.

It is important to mention that the experts qualified

three items of the face validity as unclear or with

inappropriate wording; however, these items were clearly

understood by students. The above refers to the value

that the participation of a group of students similar to

the group that will be investigated has, providing validity

to the results and compliance with the requirements for

an ethical research with children, avoiding biases due to

the perspective of adults.

The validity by experts provided a perspective from the point of view of a researcher with scientific

knowledge, and from a professional with practical

care experience and ability with students, which has

contributed significantly considering different points

of view and lines of thought. This process has been

shown to be important in achieving understandability

and cultural coherence in the search for semantic and

content equivalence(23-24).

The suggested adjustments were related to the

wording of the items and to the observations that were

analyzed from the students’ point of view, as an interface

between two visions. The importance of the participation

of these groups for the validation of scales is confirmed

by references in the literature(25).

The psychometric tests used in this study show

the high level of consistency of the results of the Child

Adolescent Teasing Scale (CATS) due to its reliability. The

interpretation of the results of the two subscales showed

that they were classified as high, indicating that the

assessment provided by this scale is reliable. In terms of

validity, the Kappa coefficient for the semantic equivalence,

clarity, consistency and relevance ranged from 0.61 to

0.80, indicating a substantial agreement, and the adequacy

showed a moderate agreement, ranging from 0.41 to 0.60,

which allowed to conclude that the proportion of times that

the evaluators agreed was high(26-27).

As limitations, some authors mention the need to

start from the official translation of the original version.

For this, the Spanish version of the instrument provided

by the author was submitted to different validity

and adaptation processes, such as back-translation,

assessment by an expert nurse, validity by students and

validity by experts. In addition, it was compared with

the original English version.

Although the objective of this study was to carry out

a qualitative assessment in terms of understandability of

the items by representatives of the same population to

which CATS would be applied, the Cronbach’s alpha was

calculated to achieve reliability, clarifying that due to the

small sample size, additional studies could support the

psychometric properties of CATS.

Regarding the number of subjects in the pilot

sample, there are different opinions, some suggest 30

to 40 people(14), or 5 to 10 people(22), because the most

important is to achieve understandability on: questions

and answers, format of the applied instrument, or

problems of the questionnaire(28). This study was carried

out with 19 students, a group that can be an important

sample to check the clarity, feasibility and practicality of

the instrument. However, further publications will present

With regard to the phenomenon of school bullying,

so widespread, health professionals are advised to

perform an interdisciplinary work, since the ultimate

goal is the health of students; and the implementation

of actions to identify children at risk of bullying, who

require care in relation to their health.

Conclusion

The cross-cultural adaptation of the Nursing

Instrument Child Adolescent Teasing Scale (CATS)

for its application in Colombian students aged 8 to

15 was carried out. This version was adapted to the

Spanish spoken in Colombia, with the participation

of students, by means of the focal group strategy,

as well as a pilot test. The participants had high

and low socioeconomic statuses, and experts in

research on bullying also participated in this study.

The adapted version showed desirable results in terms

of validity and reliability, which make it possible to point

out CATS as a valid and reliable instrument to be applied

among students with the aim of identifying the frequency

and distress caused by bullying, and it is available for

use in future investigations.

References

1. Liu J GN. Childhood Bullying: A Review of Constructs,

Concepts, and Nursing Implications. Public Health Nurs.

2011; 28(6):556–68. doi: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/

j.1525-1446.2011.00972.x

2. Olweus D, Breivik, K. Plight of Victims of School Bullying:

The Opposite of Being.In: Handbook of Child

Well-Being [Internet]. 2014 [cited Sep 26, 2016]. p. 2593–616.

Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/

978-90-481-9063-8_100

3. Jacobson G, Riesch SK, Temkin BM, Kedrowski KM,

Kluba N. Students Feeling Unsafe in School: Fifth Graders’

Experiences. J Sch Nurs. [Internet]. 2011 [cited March 6,

2014];27(2):149–59. Available from: http://jsn.sagepub.

com/cgi/doi/10.1177/1059840510386612

4. Srabstein J, Leventhal B. Prevention of bullying-related

morbidity and mortality: a call for public health policies.

Bull World Health Organ. [Internet]. 2010 jun 1 [cited

March 5, 2014]; 88(6):403. Available from: http://www.

who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/6/10-077123.pdf

5. Kvarme LG, Helseth S, Saeteren B, Natvig GK. School

children’s experience of being bullied - and how they

envisage their dream day: School children’s experience of

being bullied. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010; 24(4):791–8. doi:

http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00777.x

6. Martínez J.G. El manual de convivencia y la prevención

del bullying: diagnóstico, estrategias y recomendaciones.

Primera. Bogotá, Colombia: Magisterio; 2014. 273 p.

7. Gomes M, Davis B, Baker S SE. Correlation of the

Experience of Peer Relational Aggression Victimization and

Depression among African American Adolescent Females.

J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2009; 22(4):175–181. doi:

http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00196.x

8. Karatas H, Ozturk C. Relationship Between Bullying

and Health Problems in Primary School Children. Asian

Nurs Res [Internet]. 2011 Jun [cited March 12, 2014];

5(2):81–7. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.

com/retrieve/pii/S1976131711600169

9. Gini G, Pozzoli T G. Association Between Bullying and

Psychosomatic Problems: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics.

[Internet]. 2009 Mar 1 [cited March 26, 2014]; 123(3):

1059–65. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.

org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2008-1215.

10. Vernberg E.M, Nelson T.D, Fonagy P, Twemlow

D.W. Victimization, Aggression, and Visits to the School

Nurse for Somatic Complaints, Illnesses, and Physical

Injuries. Pediatrics. [Internet]. 2011 April [cited March 12,

2014]; 127(5):842–8. Available from: http://pediatrics.

aappublications.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2009-3415

11. Shalev I, Moffitt T.E, Sudgen, K, Williams B., Houts

R.M, Danese A, Mill J, Arseneault L, Caspi A.I. Exposure

to violence during childhood is associated with telomere

erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study.

Mol Psychiatry. [Internet]. 2013 May [cited Nov 10, 2014];

18(5):576–81. Available from: http://www.nature.com/

doifinder/10.1038/mp.2012.32

12. Hoyos O, Aparicio J, Córdoba P. Caracterización del

maltrato entre iguales en una muestra de colegios de

Barranquilla. Psicol Desde el Caribe. [Internet]. 2005

dic;(16). Disponible en: http://rcientificas.uninorte.edu.

co/index.php/psicologia/article/viewFile/1906/1245

13. Paredes M, Alvarez M, Lega L, Vernon A. Estudio

exploratorio sobre el fenómeno del “Bullying” en la ciudad

de Cali, Colombia. Rev Larinoamericana Cienc Soc Niñez

Juv. [Internet]. 2008; 6(1):295–317. Disponible en:

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rlcs/v6n1/v6n1a10.pdf

14. Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Bosi M.

Guidelines for the process of Cross-Cultural adaptation

of self-report measures. Spine. [Internet]. 2000;

25(24):3186–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.

Received: Jun 06th 2017 Accepted: Sep 22th 2017

Copyright © 2018 Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons (CC BY).

This license lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work, even commercially, as long as they credit you for the original creation. This is the most accommodating of licenses offered. Recommended for maximum dissemination and use of licensed materials.

Corresponding Author: Karol Johanna Briñez Ariza Universidad Nacional de Colombia Edificio nuevo de la Facultad de Enfermeria Av. Carrera 30 No. 45-03

Ciudad Universitaria - Edificio nuevo de Enfermeria Oficina 305-306. Bogota, Colombia.

E-mail: kjbrineza@unal.edu.co

15. Horowitz J, Vessey J, Carlson K, Bradley J, Montoya

C, McCullough, David J. Teasing and Bullying Experiences

of Middle School Students. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc.

[Internet]. 2004 ago 1 [cited March 26, 2014]; 10(4):165–72.

Available from: http://www.ingentaselect.com/

rpsv/cgi-bin/gi?ini=xref&body=linker&reqdoi=10.1177/

1078390304267862

16. Escobar J, Cuervo A. Validez de contenido y juicio de

expertos: una aproximación a su utilización. Av En Medición.

[Internet]. 2008;6(1):27–36. Disponible en: http://www. humanas.unal.edu.co/psicometria/files/7113/8574/5708/

Articulo3_Juicio_de_expertos_27-36.pdf

17. Cerda J, Villaroel L. Evaluación de la concordancia

inter-observador en investigación pediátrica: Coeficiente

de Kappa. Bioestadística. 2008;79(1):54–8.

18. Bowling A. Measuring health: a review of quality of life

measurement scales [Internet]. Maidenhead, Berkshire,

England; New York, NY: Open University Press; 2005

[cited Oct 31, 2016]. Available from: http://public.eblib.

com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=287844

19. National Association of School Nurses. Bullying

Prevention in Schools [Internet]. 2014 [cited

Jun 7, 2014]. Available from: http://www.nasn.

org/PolicyAdvocacy/PositionPapersandReports/

NASNPositionStatementsFullView/tabid/462/ArticleId/638/

Bullying-Prevention-in-Schools-Adopted-January-2014

20. Vessey J, Strout T, DiFazio R, Walker A. Measuring the

Youth Bullying Experience: A Systematic Review of the

Psychometric Properties of Available Instruments. J Sch

Health. 2014; 84(12):819–43. doi: 10.1111/josh.12210.

21. Vessey J, Horowitz J, Carlson K, Duffy M.J.A.

Psychometric Evaluation of the Child-Adolescent

Teasing Scale. J Sch Health. 2008. doi: http://doi.wiley.

com/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00312.x

22. Lauffer A, Solé L, Bernstein S, Lopes MH, Francisconi

CF. Cómo minimizar errores al realizar la adaptación

transcultural y la validación de los cuestionarios sobre

calidad de vida: aspectos prácticos. Rev Gastroenterol

México. [Internet]. 2013 Jul [Acceso 16 sept 2016];

78(3):159–76. Disponible en: http://linkinghub.elsevier.

com/retrieve/pii/S0375090613000529

23. Gjersing L, Caplehorn JR, Clausen T. Cross-cultural

adaptation of research instruments: language, setting,

time and statistical considerations. BMC Med Res Methodol.

[Internet]. 2010 dic [cited Sep 11, 2016]; 10(1). Available

from: http://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/

articles/10.1186/1471-2288-10-13

24. Caro-Bautista J, Morilla-Herrera JC, Villa-Estrada F,

Cuevas-Fernández-Gallego M, Lupiáñez-Pérez I,

Morales-Asencio JM. Adaptación cultural al español y validación

psicométrica del Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities

measure (SDSCA) en personas con diabetes mellitus tipo

2. Aten Primaria. [Internet]. 2016 ago [Acceso 7 nov

2016]; 48(7):458–67. Disponible en: http://linkinghub.

elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0212656715003388

25. Sawicki GS, Garvey KC, Toomey SL, Williams KA,

Chen Y, Hargraves JL, et al. Development and Validation of

the Adolescent Assessment of Preparation for Transition:

A Novel Patient Experience Measure. J Adolesc Health.

[Internet]. 2015 Sep [cited Nov 7, 2016]; 57(3):282–7.

Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/ pii/S1054139X15002499

26. Alexandre NMC, Coluci MZO. Validade de conteúdo

nos processos de construção e adaptação de instrumentos

de medidas. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2011; 16(7):3061–8.

doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232011000800006.

27. Hernández H, R, Fernández C, Baptista P. Metodología

de la investigación. México, D.F.: McGraw-Hill Education;

2014.

28. Ferreira L, Nogueira A, Betanho M, Gomes M. Guia da

AAOS/IWH: sugestões para adaptação transcultural de

escalas. Aval Psicológica. [Internet]. 2014; 13(3):457–61.

Available from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/avp/v13n3/