www.rpped.com.br

REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Functional

performance

of

school

children

diagnosed

with

developmental

delay

up

to

two

years

of

age

Lílian

de

Fátima

Dornelas

a,∗,

Lívia

de

Castro

Magalhães

baPrefeituraMunicipaldeUberlândia,Uberlândia,MG,Brazil

bDepartamentodeTerapiaOcupacional,EscoladeEducac¸ãoFísica,Fisioterapia,Educac¸ãoFísica(EFFTO),UniversidadeFederal

deMinasGerais(UFMG),BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil

Received7January2015;accepted26May2015 Availableonline20October2015

KEYWORDS

Evaluation;

Childdevelopment;

Students

Abstract

Objective: Tocomparethefunctionalperformanceofstudentsdiagnosedwithdevelopmental delay(DD)uptotwoyearsofagewithpeersexhibitingtypicaldevelopment.

Methods: Cross-sectionalstudywithfunctionalperformanceassessmentofchildrendiagnosed withDDuptotwoyearsofagecomparedtothosewithtypicaldevelopmentatseventoeight yearsofage.Eachgroupconsistedof45children,selectedbynon-randomsampling,evaluated formotorskills,qualityofhomeenvironment,schoolparticipationandperformance.ANOVA andtheBinomialtestfortwoproportionswereusedtoassessdifferencesbetweengroups.

Results: ThegroupwithDDhadlowermotorskillswhencomparedtothetypicalgroup.While 66.7%ofchildreninthetypicalgroupshowedadequateschoolparticipation,receivingaidin cognitiveandbehavioraltaskssimilartothatofferedtootherchildrenatthesamelevel,only 22.2%ofchildrenwithDDshowedthesameperformance.Although53.3%ofthechildrenwith DDachievedanacademicperformanceexpectedfortheschoollevel,therewerelimitationsin someactivities.Onlytwoindicatorsoffamilyenvironment,diversityandactivitieswithparents athome,showedstatisticallysignificantdifferencebetweenthegroups,withadvantagebeing shownforthetypicalgroup.

Conclusions: ChildrenwithDDhavepersistentdifficulties atschoolage,withmotordeficit, restrictionsinschoolactivityperformanceandlowparticipationintheschoolcontext,aswellas significantlylowerfunctionalperformancewhencomparedtochildrenwithoutDD.Asystematic monitoringofthispopulationisrecommendedtoidentifyneedsandminimizefutureproblems. ©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:liliandefatima@hotmail.com(L.F.Dornelas).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2015.10.001

2359-3482/©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Avaliac¸ão; Desenvolvimento infantil;

Escolares

Desempenhofuncionaldeescolaresquereceberamdiagnósticodeatraso

dodesenvolvimentoneuropsicomotoratéosdoisanos

Resumo

Objetivo: Compararodesempenhofuncionaldeescolaresquereceberamdiagnósticodeatraso dodesenvolvimentoneuropsicomotor(ADNPM)atédoisanoscomparescomdesenvolvimento típico.

Métodos: Estudotransversal comavaliac¸ãododesempenhofuncionalemcrianc¸as que rece-beram diagnóstico de ADNPM até os dois anos e em crianc¸as com desenvolvimento típico nasidadesdeseteeoitoanos.Cadagrupofoiconstituídopor45crianc¸as,selecionadaspor amostragemnão aleatória,avaliadas quantoàcoordenac¸ãomotora,qualidade doambiente familiar,participac¸ãoedesempenhonaescola.OstestesAnovaebinomialparaduasproporc¸ões foramusadosparaverificardiferenc¸aentreosgrupos.

Resultados: OgrupocomADNPMobtevedesempenhomotorinferiorquandocomparadocom ogrupo típico.Enquanto 66,7%dascrianc¸as dogrupotípico tiveramparticipac¸ãoadequada naescola, receberamauxílionastarefas cognitivasecomportamentaissimilar aooferecido àsdemaiscrianc¸asdomesmonível,apenas22,2%crianc¸ascomatrasoapresentaramomesmo desempenho.Embora53,3%dascrianc¸ascomatrasotenhamatingidodesempenhoacadêmico esperadoparaonívelescolar,houvelimitac¸õesemalgumasatividades.Apenasdoisindicadores doambientefamiliar,diversidadeeatividadecomospaisemcasamostraramdiferenc¸a esta-tisticamentesignificativaentreosgrupos,comvantagemparaogrupotípico.

Conclusões: Crianc¸ascomADNPMapresentamdificuldadespersistentesnaidadeescolar,com déficitmotor,restric¸õesnodesempenhodeatividadesescolaresebaixaparticipac¸ãono con-texto escolar,alémdedesempenhofuncionalsignificativamenteinferioraodecrianc¸as sem históriadeatraso.Recomenda-seoacompanhamentosistemáticodessapopulac¸ãopara identi-ficarnecessidadeseminimizarproblemasfuturos.

©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteéumartigo OpenAccesssobalicençaCCBY(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.pt).

Introduction

Developmentaldelay(DD)isaconditioninwhichthechildis

notdevelopingand/ordoesnotachieveskillsconsistentwith

whatisexpectedfortheirage.1Althoughtheterm‘‘delay’’

gives the impression of a relatively benigncondition that improveswithage,many ofthosechildrendonotreceive follow-upwithsystematic assessmentsand haveproblems at schoolage andadult life.2 Infact,it is estimated that

60---70%ofchildrenbornwithriskconditionswillrequire sup-portfromspecialeducationservicesinelementaryandhigh school,andthereisevidencethatgapsinthedevelopment of childrenabout toenterschool mayimpairtheir school performanceandfutureopportunities.3

Studies4,5 on the development outcome at school age

indicate that DD has an effect on a complex range of symptoms, without a defined disease profile, and thus it isimportanttoobtaininformationaboutwhatthechildis capableofdoinginadailycontext,tobetterunderstandits consequences.Althoughitisrecommendedthattheuseof theterm‘‘DD’’berestrictedtothefirstfiveyearsoflife,6

inBrazilitsuseiscommonthroughoutchildhoodand adoles-cence,withoutabetterunderstandingofthedevelopment outcomeofthesechildren,especiallyregardingfunctional performance in the school context. We should therefore investigatetheoutcomeofthesechildreninterms offinal diagnosis,aswell asthe impactof thedelayonthe func-tionalandacademicperformance.

AsexplainedbytheInternationalClassificationof Func-tioning, Disability and Health---ICF---WHO (World Health Organization),7inordertounderstandtheimpactofahealth

conditionsuchasDDonthechild’slife,itisimportantto per-formanextensiveassessmenttoobtaininformationnotonly aboutbasicbodyfunctions,butalsoontheactivityand par-ticipationindifferentcontexts.Inthisstudy,theICF---WHO modelwasusedtoguidetheprocessofassessingchildren withahistory ofDD anddescribethechild’sperformance intheschoolcontext.Theaimofthestudywastocompare thefunctionalperformanceofstudentswhowerediagnosed withDD upto two yearsof age, withthat of peers with typicaldevelopment.

Method

Thiswasacross-sectionalstudytoevaluatethefunctional

performanceof students whowere diagnosed withDD up

totwoyearsofageandthosewithtypicaldevelopmentat

seventoeightyearsofage,selectedbynon-random

samp-lingandmatchedforage,genderandfamilyincome.Each

group consisted of 45 children and the subjects with DD

were recruited from Associac¸ão de Assistência à Crianc¸a

Deficiente de Minas Gerais (AACD/MG); their peers were

selectedfromthesameschoolswherethechildrenfromthe

AACD/MGisspecializedintreatingindividualswith phys-icaldisabilities.Babieswhohavepre-,peri-,andpostnatal

complicationsand/ordevelopmentalproblemsarereferred

byphysiciansfrombasichealthunitsorhospitalsandbythe

parents,beingevaluatedbytheAACD/MGteam,who

ver-ifytheneedforintervention.ThediagnosisofDDisbased

onaclinicalassessmentcarriedoutbythephysicianofthe

institution, throughneurological assessment. As the term

‘‘DD’’ is not found in the ICD-10, in order tobe treated

at the institution, these children are classified according

tothe categoriesof ChapterVI(NervousSystemDiseases)

--- code:G00-G99,specificallyin thesubcategory closerto

theterm,UnspecifiedCerebralPalsy---code:G80.9.After

medicalassessment,childrenarereferredtooverall

assess-ment,inwhich themultidisciplinaryteam,consisting ofa

physiotherapist, speech therapist, psychologist and

occu-pational therapist, makes the direct clinical observation,

describesthechild’sdevelopment,discussesthecasewith

thephysiciananddefineswhetherthechildwillbenefitfrom

interventionandwhattherapiesarenecessary.Allchildren

admittedtotheAACDundergoaninitialmedicalevaluation,

aswellasafinalevaluation,whentheymeetthecriteriafor

discharge.Assessmentsarepredominantlyclinical,without

theuseofstandardizedtests.ChildrenwithDDadmittedat

AACDusuallyexhibitmotordelayandhaveweekly

consulta-tionswithphysicaltherapy,hydrotherapyandoccupational

therapyprofessionalstoacquiretypicalgait,whentheyare

dischargedfromcare.EventhoughtheAACD/MGdoesnot

providealongitudinalfollow-upprogramforthesechildren,

astheyhave nophysicaldisability,theymayreturntothe

institutiontoreceiverecommendationsortoundergo

ther-apieswithspecificgoals,albeitintheshortterm.Thereis

nospecific follow-upprogramfor thispopulation,andthe

returnvisitsdependontheparents’decision.

Inthiscontext,eligiblechildrenforthestudywere

iden-tifiedthrough the review of medical files withthe G80.9

codefromICD-10,fromAugust2001toAugust2009,inthe

AACD/MGfilingsector.Theinitiallistcontained329records

thatwerescreened,accordingtotheinclusionandexclusion

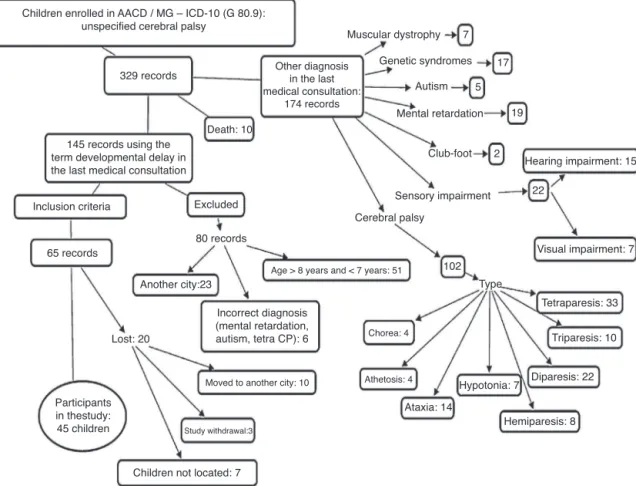

criteria,until45studyparticipantswereobtained,asshown inFig.1.Theinclusioncriteriawerechildrenofboth gen-ders,bornbetweenJanuary2003andApril2006,livinginthe cityofUberlândia(MG),diagnosedwithDD,whichhadpre-, peri-,andpostnatalcomplications,withnoevident neuro-logicaland/ororthopedicdisorders,malformations,aswell asvisual or hearingimpairments. The studyonly included children who had,in the last medicalevaluation, typical gait,theoneswhoweredischargedfromtherapeuticcare, attendedschoolregularlyandwhose parents or guardians signed theinformed consentform(ICF), authorizingtheir participationin thestudy.Childrenwereexcludediftheir diagnosis changed to cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, autism,mentalretardationorsyndromes, aswellasthose whoremainedwithadiagnosisofDD,buthadevident neu-rologicaland/or orthopedicdisorders,malformations,and visualorhearingimpairment.

The children with typical developmentwere recruited fromthesameschoolsthecasesfromAACD/MGattended. Therecruitment ofeach child fromthetypicalgroup was carriedoutinthesameclassroom ofeachchilddiagnosed withDD.The authors, afterreceiving parentalconsentof the child with DD, went to the school and made contact

with the teacher. Each teacher was asked to identify, in therollcall,studentsofthesamegenderandageasthose diagnosedwithDD.Afterthechildrenwereidentified,they werechosenbydrawinglots,andaninvitationletter(ICF) was sent tothe parent/guardian. Along with the ICF, the parent/guardianansweredabriefquestionnaireabout the development history in order to ensure that the child fit thegroupprofile.Onlychildren whoseICFswerereturned withtheparents’/guardian’ssignatureandwiththe ques-tionnaireanswered by parents/guardians wereevaluated; otherwise, the teacher choseanother studentby drawing lots.Childrenwereexcludediftheyhad,accordingtothe questionnaire,adiagnosisofspecificneurologicalorgenetic disordersand risk factorssuch asprematurity and/or low birth weight, hearing and visual impairments, as well as orthopedicproblems (fractureofthelowerlimbsand oth-ers),continuoususeofanticonvulsants,prolongedillnessin thethreemonthsprior tothetest, historyofgrade repe-titionanddifficultiesthatrequiredpedagogicalsupportor somekindofspecializedtherapy(physicaltherapy,speech therapy,psychologicalsupport,occupationaltherapy).

Thefollowingtoolswereusedintheresearch:

• Semi-structuredsystemfordataextractionfromrecords of DD children from the AACD/MG. Information was obtainedaboutthechild’shistory(gestationalage,birth weight and neonatal conditions), medical diagnosis on enteringtheinstitutionandtheoneregisteredinthelast consultation in the unit, parents/guardian information (maternalandpaternalschooling,familyincome),school data(name,address,telephone,teacherandgrade),as wellasrehabilitationaspects(child’sinitialandfinal eval-uationsmadebytherehabilitationteamandthetherapies performedduringtheinterventionperiod).Astheinitial andfinalevaluationsofeachchildismadedescriptively, theinformationwascategorizedintothreecomponents: (a)motor,fortheevaluationofthephysicaltherapy sec-tor;(B)activity,fortheoccupationaltherapysector,and (c)participation,for thepsychology sector assessment; theinformationofeachcomponentwascodedtoindicate whether the child’s developmental level was delayed, suspected or appropriate. Data collection from medi-calrecordswasperformedbytworesearchers,whohad beenpreviouslytrainedwith20records,obtainingagood Kappaagreementindex(0.63---0.79).

Children enrolled in AACD / MG – ICD-10 (G 80.9): unspecified cerebral palsy

329 records

Death: 10

Muscular dystrophy

Genetic syndromes

Autism

Mental retardation Other diagnosis

in the last medical consultation:

174 records

Incorrect diagnosis (mental retardation, autism, tetra CP): 6

Club-foot

Sensory impairment

Hearing impairment: 15

Visual impairment: 7

Tetraparesis: 33

Triparesis: 10

Diparesis: 22

Hemiparesis: 8 Hypotonia: 7

Ataxia: 14 Athetosis: 4

Chorea: 4 Cerebral palsy

7

17

5

2

22

102

19

Excluded Inclusion criteria

65 records

Another city:23

Lost: 20

Study withdrawal:3 Participants

in thestudy: 45 children

145 records using the term developmental delay in the last medical consultation

Moved to another city: 10

Age > 8 years and < 7 years: 51

Children not located: 7 80 records

Type

Figure1 Screeningofpatients’recordstoselecttheparticipantsintheDDgroup.

masteryoftheskillsexpectedfortheschoolyear---

pre-sentedpre-syllabicleveland/orgrading.

• MovementAssessmentBatteryforChildren---MABC-28:

It is a standardized test toidentify motor coordination disorders in children aged4---16 years old, divided into three areas: manualdexterity, hand grasping, throwing andbalance.Thesumofscoresforeachcategoryprovides astandardizedscore,andthesumofthethreecategories providesthetotalscore,whichisconvertedtopercentile. Acut-off≤15%indicatespossiblemotorimpairment,and ascore≤5%indicatesdefinitivemotordeficits.Children withscore≤5%wereconsideredashavingmotor coordi-nation problemsorsignsofDevelopmentalCoordination Disorder (DCD); ascoreof 6---15%,suspectedcases, and children with a score >15% were considered as having normalmotorperformance.

• School Function Assessment --- SFA9: This is a

ques-tionnaire to assess functional performance and the participation of children aged5---12 years in the school environment, consisting of three parts: participationin differentschoolenvironments,assistancewithtasksand taskperformance.TherawSFAscoresareconvertedinto ascaleof0---100,withthelatterbeingthehighestpoint or a fully operational degree in the assessed area. SFA resultscanbeinterpretedintwoways,atthebasicand advancedlevels.Forthisstudy,weusedthebasiclevel, whichshowsifthechild’sfunctionintheschool environ-mentisasexpectedforchildrenofthesameageandat thesameschoolyear.

• FamilyEnvironmentResourceInventory---FERI10:Itisa

questionnaireusedtoassessresourcesofthefamily envi-ronment, divided into threeareas: material resources, activities that signal family life stability and parent-ingpractices. To obtainthe relativescorein 10 points, the following formula wasused: raw score/topic maxi-mumscore×10,inwhichtherawscoreisthenumberof checkeditemsandthemaximumscoreisthetotal num-berofitems,exceptintopics8---10,whichhavespecific scores.Therelativescoreisusefultocomparethescores betweeninventoryitems.

DatawerecollectedfromJanuary2010toJanuary2012. Allchildren whoparticipatedin thisstudy wereevaluated byMABC-2test,theSFAandFERIquestionnaires,anda clas-sification of school performance was made based on the teachers’reports. The MABC-2 is one of the most widely used tests in research for the diagnosis of DCD and was usedinthisstudy toevaluatethe children’smotor devel-opment.The MABC-2 hasgoodlevels oftest-retest (0.75) andinter-raterreliability(0.70)11,12;ithasbeenusedin

dif-ferentcountriesandthereisevidenceofscorevalidityfor Brazilianchildren.13 AsMABC-2 isaperformance test,the

inter-rater reliabilitywas verified before data collection, yieldinganindexof0.80(IntraclassCorrelation).

standardizedforBrazilianchildren,North-Americanstudies supportthe validityand reliabilityof thistool.14 TheFERI

hasshowntobeusefultodifferentiatefamilyenvironment characteristics of children with different levels of school performance and behavior problems and has appropriate parametersoftest-retestreliability(0.92---1.00),aswellas goodinternal consistency(0.84).15 Althoughthisinventory

doesnothaveacut-off,ithasbeenusedinBraziltocompare groupsofchildren.

All children lived in the city of Uberlândia (MG), and all were evaluatedby the first author,previously trained to apply the tests and questionnaires. The SFA question-naireandinformationaboutschool performance(grading) wereappliedtogetherwiththechild’steacherinthechild’s school. On that visit, the first author explained to the teacheraboutthedrawingofonechild’snameinthesame classroomthechildwithDDattended.Thesechildrenwere subsequentlyevaluatedaftertheybroughtthesignedICF.

Thefirstauthorvisited35schools(20municipalschools, eightstateschools,sixprivateandonefederalschool)as, of the 45 children from the DD group, only ten students attendedthesameschool.Toenterthemunicipalschools, theresearcherhadtoobtaintheconsentfromthe Educa-tionSecretariat of theUberlândia MunicipalGovernment. Intheotherschools(state,federalandprivate),individual contactwasmade,andallschools receivedthe documen-tation demonstratingthat the children with DD had their parents’ permission (ICF) andthe study had the approval fromtheInstitutionalReviewBoardofAACD(No.09/2010) andtheInstitutionalReviewBoardofUniversidadeFederal deMinasGerais(COEP/UFMGNo.ETIC0482.0.203.000-10). The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 17.0, was used for data analysis. The descriptionofthegroupswasmadebymeasuresofcentral tendency(meanandstandarddeviation)orfrequency.The Shapiro-Wilk’snormalitytestwasapplied,whichfoundthat mostof the variableshad anormal distributionand thus, parametrictestswerechosen.AnalysisofVariance(ANOVA) wasusedforinferentialstatistics,aimingtoidentifypossible differencesbetweenthegroupsDDandtypicaldevelopment regardingthequantitativevariablesofmotorperformance, environmental resource and participation at school. The Binomial test for two proportions wasused for the cate-gorical variable performance in the academic content. A significancelevel≤0.05wasconsideredforallanalyses.

Results

Of the65 children from AACD/MG diagnosedwith DD, 45

(69.3%)participatedin thestudy,whereastheothers(20;

30.7%)werelostduetostudywithdrawal,movingtoanother

cityandchildrennotbeingfound.Therefore,theDDgroup

consistedof45childrendiagnosedwithDD,andthetypical

group consisted of 45 children with typical development,

selectedbynon-randomsampling,matchedbygender,age

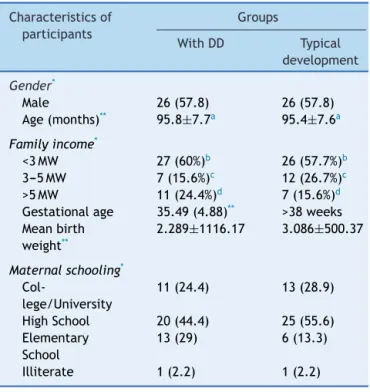

andhouseholdincome.Table1showsthedescriptive

infor-mationofthegroups.

IntheDD group,23(51.1%)children wereborn prema-turely,withgestationalagerangingfrom24to36weeks;in the neonatalperiod, 17 (37.8%) hadjaundice, 13 (28.9%) had seizures, 14 (31.1%) reported the need for oxygen

Table1 Characteristicsofchildrenwithdelayed neuropsy-chomotor development (DD) and typical development at schoolage.

Characteristicsof participants

Groups

WithDD Typical development

Gender*

Male 26(57.8) 26(57.8)

Age(months)** 95.8±7.7a 95.4±7.6a

Familyincome*

<3MW 27(60%)b 26(57.7%)b

3---5MW 7(15.6%)c 12(26.7%)c

>5MW 11(24.4%)d 7(15.6%)d

Gestationalage 35.49(4.88)** >38weeks

Meanbirth weight**

2.289±1116.17 3.086±500.37

Maternalschooling*

Col-lege/University

11(24.4) 13(28.9)

HighSchool 20(44.4) 25(55.6)

Elementary School

13(29) 6(13.3)

Illiterate 1(2.2) 1(2.2)

MW,minimumwages. n=45ineachgroup.

a p=0.794. b p=0.830. c p=0.197. d p=0.292.

* Frequency(percentage)ofchildrenineachcategory. ** Mean±standarddeviation.

supplementation, and 12 (26.7%) had signs of perinatal

hypoxia. Thetypicaldevelopmentgroupconsisted of

chil-dren born at term, with no record of relevant neonatal

complications.

ThechildrenfromtheDDgroupcommonlyhad,asinitial

developmentcharacteristics, motor delay (24;55.6%) and

suspectedlevelofdevelopmentintheareasofactivity(27;

60%)andparticipation(27;60%).The endofthe

multidis-ciplinaryintervention, whichlastedonaverage2.61±1.96

years,wasmainlyduetothefactthatmotordevelopment

hadbeenconsideredappropriateforage(41;91.1%).

Therewasameandifferencebetweenthe groupswith

statisticalsignificanceinallMABC-2areas(Table2).TheDD grouphadlowerperformanceinalltestdomains,withmost children from this group (28; 62.2%) showing motor diffi-culty,whilefour(8.9%)wereatriskformotordifficulty.In thetypicalgroup,five(11.1%)childrenhadmotordifficulty andsix(13.3%)wereatriskformotordifficulty.

Table2 Comparisonsbetweenpercentilesofmotorperformanceforthegroupswithdevelopmentaldelay(DD)andtypical development.

MABC-2 Mean±SD Minimum---maximum p-valuea

WithDD Typical WithDD Typical

Manualdexterity 20.1±26.2 48.7±31.2 0.5---98 2---99.9 <0.001

Throwingandgrasping 19.8±21.2 30±23.5 0.5---91 1---91 0.034

Balance 14±21.8 33.2±26 0.1---95 2---99 <0.001

Totalmotor 13.2±21.6 34.3±27 0.1---91 2---98 <0.001

MABC-2,movementassessmentbatteryforchildren;SD,standarddeviation;n,45ineachgroup. a ANOVA.

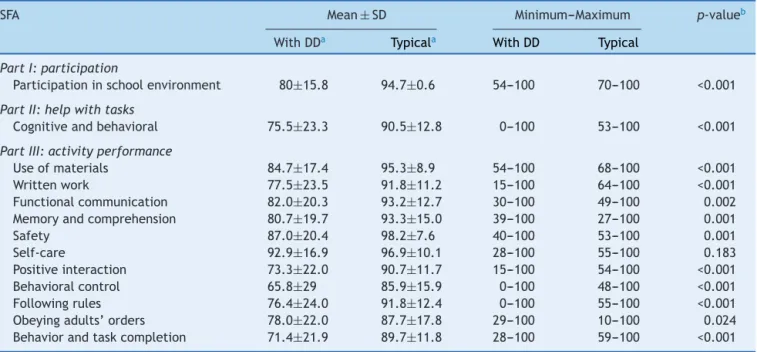

Table3 Comparativedataintheschoolparticipationquestionnairescoreforgroupswithdevelopmentaldelay(DD)andtypical development.

SFA Mean±SD Minimum---Maximum p-valueb

WithDDa Typicala WithDD Typical

PartI:participation

Participationinschoolenvironment 80±15.8 94.7±0.6 54---100 70---100 <0.001

PartII:helpwithtasks

Cognitiveandbehavioral 75.5±23.3 90.5±12.8 0---100 53---100 <0.001

PartIII:activityperformance

Useofmaterials 84.7±17.4 95.3±8.9 54---100 68---100 <0.001

Writtenwork 77.5±23.5 91.8±11.2 15---100 64---100 <0.001

Functionalcommunication 82.0±20.3 93.2±12.7 30---100 49---100 0.002 Memoryandcomprehension 80.7±19.7 93.3±15.0 39---100 27---100 0.001

Safety 87.0±20.4 98.2±7.6 40---100 53---100 0.001

Self-care 92.9±16.9 96.9±10.1 28---100 55---100 0.183

Positiveinteraction 73.3±22.0 90.7±11.7 15---100 54---100 <0.001 Behavioralcontrol 65.8±29 85.9±15.9 0---100 48---100 <0.001

Followingrules 76.4±24.0 91.8±12.4 0---100 55---100 <0.001

Obeyingadults’orders 78.0±22.0 87.7±17.8 29---100 10---100 0.024 Behaviorandtaskcompletion 71.4±21.9 89.7±11.8 28---100 59---100 <0.001

SFA,schoolfunctionassessment;SD,standarddeviation;n,45ineachgroup. a Meanrawdatatransformedtoascaleof0---100.

b ANOVA.

typical development group showed a consistent, superior

performanceinalltaskswhencomparedwiththeDDgroup.

ChildrenfromtheDDgrouphadlimitedperformance,

espe-cially in activities that required positive interaction (26;

57.8%),behavioralcontrol(26;57.8%)andcompletingtasks

(28;62.2%)(Table3).

Regarding academic performance, there were differ-ences between thegroups, with statisticalsignificance at levelsI(p=0.001)andII(p=0.008).Most(38;84.5%)ofthe childrenfromthetypicaldevelopmentgroupshowed mas-teryoftheacademic content(levelI---alphabeticand/or excellentgrading),andtherest(6,13.3%---levelII: syllabic-alphabetic or syllabic, good grading; 1, 2.2% --- level III: pre-syllabicand/or fairgrading) werein thedevelopment phase.Inthe DD group,most (24;53.3%)achievedlevel I andlevelII (17;37.8%),withonlyfour(8.9%)childrenstill receivingfairgrading.

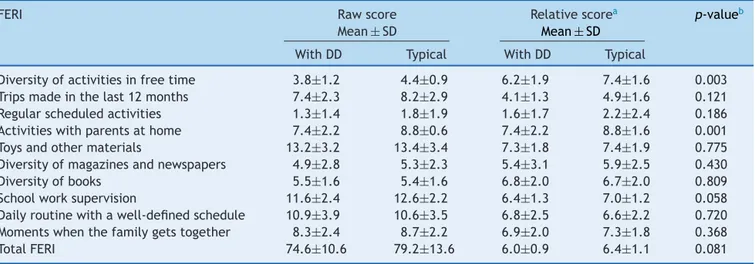

AsindicatedinTable4,althoughthereisadifferencein themeans betweengroups regarding theFERIitems,only twoindicators reachedstatisticalsignificance(p≤0.05).In

theDDgroup, childrenwereless activeintheirfree time andsharedfeweractivitieswiththeirparentsathome.

Discussion

AlthoughthetermDDiswidelyusedinBrazilianliterature,

littleis knownabout the outcome of thesechildren. This

study demonstrates that children with a diagnosis of DD

attaineduptotwoyearsofageshow,atschoolage,motor

limitations,restrictionsinschoolactivityperformance,low

participationinthe schoolcontext andsignificantlylower

functional performance when compared to the children

without a history of delay.Although children persist with

thedelay,thefunctionaloutcomewasbetterthanthemotor

one,suggestingthepossibilityofadaptation,whichis

con-sistentwiththeWHO---ICFperspective7thattheassociation

Table4 ComparativedataoftheFamilyEnvironmentResourceInventory(FERI)forgroupswithdevelopmentaldelay(DD)and typicaldevelopment.

FERI Rawscore

Mean±SD

Relativescorea

Mean±SD

p-valueb

WithDD Typical WithDD Typical

Diversityofactivitiesinfreetime 3.8±1.2 4.4±0.9 6.2±1.9 7.4±1.6 0.003 Tripsmadeinthelast12months 7.4±2.3 8.2±2.9 4.1±1.3 4.9±1.6 0.121 Regularscheduledactivities 1.3±1.4 1.8±1.9 1.6±1.7 2.2±2.4 0.186 Activitieswithparentsathome 7.4±2.2 8.8±0.6 7.4±2.2 8.8±1.6 0.001 Toysandothermaterials 13.2±3.2 13.4±3.4 7.3±1.8 7.4±1.9 0.775 Diversityofmagazinesandnewspapers 4.9±2.8 5.3±2.3 5.4±3.1 5.9±2.5 0.430

Diversityofbooks 5.5±1.6 5.4±1.6 6.8±2.0 6.7±2.0 0.809

Schoolworksupervision 11.6±2.4 12.6±2.2 6.4±1.3 7.0±1.2 0.058 Dailyroutinewithawell-definedschedule 10.9±3.9 10.6±3.5 6.8±2.5 6.6±2.2 0.720 Momentswhenthefamilygetstogether 8.3±2.4 8.7±2.2 6.9±2.0 7.3±1.8 0.368

TotalFERI 74.6±10.6 79.2±13.6 6.0±0.9 6.4±1.1 0.081

SD,standarddeviation;n,45ineachgroup.

aRelativescore:meanrawdatatransformedtoascalefrom0to10. b ANOVA,relativescore.

Itisknownthattheriskfactorsfordelayaremultipleand

theaccretionofconditionscandetermineahigherimpacton

childdevelopment.16,17ChildrenfromtheDDgroupincluded

in this study came from low-income families, with most familiesreceivinglessthanthreeminimumwages,andthe majorityofthe mothershadonlyhigh-schoollevel educa-tion.Additionally,51.1%ofchildrenintheDD grouphada historyofprematurity,lowbirthweightandneonatal neu-rologicalcomplications. Although one cannotexclude the effectofotherfactorsnotassessedontheoutcomeofthe DDgroup,biologicalrisk,representedespeciallyby prema-turity,was decisiveon theother factors. As discussed by someauthors,18,19in spiteofthelowinvestmentin

deter-miningtheetiology,manystudiesindicatebiologicalfactors as determinants of most DD cases. In the study of Srour etal.,20 for instance,which investigatedthe causeofthe

delaythroughclinicalandlaboratorytests,theetiologyof 77% of the cases wasidentified, and brain malformation, hypoxic-ischemicencephalopathyandchromosomal abnor-malitieswerethemostcommoncauses.

Thehighfrequency(62.2%)ofmotordisordersatschool age found in the DD group corroborates the literature. A meta-analysisby Williams et al.,21 includingstudies on

school children born prematurely, indicated a prevalence ofupto40.5%ofmotoralterationsversus6%inthegeneral population.Althoughthetypicalgroupalsoincludeschildren withmotordifficulties(11.1%),thefrequencywascloseto thatexpectedforthegeneralpopulation,asobservedinthe studybyGoyenandLui22 who,whenassessingpretermand

full-terminfantswiththeMABC-2test,foundaprevalence ofmotordeficitof42%inthepretermand8%inthefull-term infants.

As for school performance,measured by the academic contentdomain according tothe teacher’sassessment, it was observed that just a little over half (53.3%) of the children from the DD group had excellent grading, indi-cating advancement in the literacy process. It is worthy notingthat,evenin thepresenceofmotor alterations,as mentionedbefore,thesechildrenachievedmasteryofthe academiccontent.Eventhoughthechildrenpersistedwith

thedelay,thefunctionaloutcomewasbetterthanthemotor one,suggestingthatchildrenareabletoadaptorthatitis possibletomodifytheenvironmenttofacilitate participa-tionandlearning.5

ChildrenfromtheDDgroup,however,hadworsescoresin allareasofschoolparticipationintheSFAandonly22.2%of them,versus66.7%inthetypicaldevelopmentgroup, effec-tivelyparticipatedintheschoolenvironment,without the needforextrahelpincognitiveandbehavioraltasks.Riou etal.5alsofoundthatonly17%ofchildrenwithDD

partic-ipatedin the classroom without help. Possibly, the motor delay, asrecorded in this study,had more impacton the performance of the necessary activities to participate in class(e.g.handling materials,written work) thanon aca-demic performance measured byliteracy, which does not necessarilyrequirethemotorcomponent.

Thestudy’slimitationsincludetheuseofimportedtests, withoutfullyvalidatedcut-offsfortheBrazilianpopulation, usingtheteachers’reportstoclassifytheacademic perfor-mance,andthefactthatitisaconveniencesample.Foreign testshavebeenroutinelyusedinBrazilianstudies,andthe MBC-2wasrecentlyvalidated.13Additionally,carewastaken

to collect comparative data. As many children in the DD grouphadliteracyproblems,itwouldbeimportantto per-forma language assessment, whichshould beincluded in futurestudies.Teachers’reportswereusedinotherstudies, suchastheonebyPritchardetal.,23which,when

compar-ing thequalitative teacher’sevaluationwithstandardized measurements,foundthatthereportdetectedtwotothree times morechildren likelyto have learningdifficulties. It is recommendedthat futurestudies leave the rehabilita-tion center contextto includea broader population from basic health units,in ordertoinvestigate theoutcome of milderandmorevariedcasesofDD,asitcanprovide neces-sarystatisticalpowertodetectdifferencesinenvironmental factors.

asignoffutureconditionsthatshouldbebettermonitored anddiagnosedasearlyaspossible.Themonitoringshouldbe performedatleastuntilschoolage,inordertoidentifythe needsastheyarise,minimizingproblemsatschoolageand adulthood.Sporadicevaluationscanhelpprofessionalsand parentsunderstandwhatishappening,soadequatesupport canbeprovidedtothechilduptothe‘‘finaldiagnosis’’ defi-nition,asthe‘‘DD’’termshouldbeusedonlyasatemporary diagnosis.

Funding

CNPq---No.483652-2011-3.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorshavenoconflictsofinteresttodeclare.

References

1.ShevellMI. Global developmentaldelayand mental retarda-tionorintellectualdisability:conceptualization,evaluationand etiology.PediatrClinNorthAm.2008;55:1071---84.

2.Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Platt RW, Webster R, Birnbaum R. Developmentalfunctionaloutcomesatschoolageofpreschool children with global developmental delay. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:254---65.

3.MannJR,CrawfordMS,WilsonL,McDermottS.Doesrace influ-enceageofdiagnosisforchildrenwithdevelopmentaldelay?J DisabilHealth.2008;1:157---62.

4.Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Platt RW, Webster R, Birnbaum R. Developmental functional outcomes in children with global developmentaldelayordevelopmentallanguageimpairment. DevMedChildNeurol.2005;47:678---83.

5.RiouE,GhoshS,FrancouerE,ShevellMI.Globaldevelopmental delayanditsrelationshiptolatercognitiveskills.DevMedChild Neurol.2009;2:145---50.

6.ShevellMI,AshwalS,DonleyD,FlintJ,GingoldM,HirtzD,etal. Practiceparameter:evaluationofthechildwithglobal develop-mentaldelay:reportoftheQualityStandardsSubcommitteeof theAmericanAcademyofNeurologyandThePractice Commit-teeoftheChildNeurologySociety.Neurology.2003;60:367---79. 7.Organizac¸ãoMundialdeSaúde.CIF:Classificac¸ãoInternacional deFuncionalidade,IncapacidadeeSaúde.Traduc¸ãodoCentro ColaboradordaOrganizac¸ãoMundialdaSaúdeparaaFamíliade Classificac¸õesInternacionais.SãoPaulo:EDUSP;2003.

8.Henderson SE, Sugden DA,Barnett A. Movement assessment batteryforchildren-2(MABC-2).2nded.SanAntonio,TX:The PsychologicalCorporation;2007.

9.CosterWJ,DeeneyT,HaltiwangerJ,HaleyS.Schoolfunction assessment.SanAntonio:Pearson;1998.

10.MarturanoEM.OInventáriodeRecursosdoAmbienteFamiliar ---RAF.PsicolReflexCrit.2006;19:498---506.

11.VanWelvelde H,WeerdtW, De CockP,Smits-EngelsmanBC. Aspectsofthevalidityofthemovementassessmentbatteryfor children.HumMovSci.2004;23:49---60.

12.WilsonPH.Practitionerreview:approachestoassessmentand treatmentofchildrenwithDCD:anevaluativereview.JChild PsycholPsychiatry.2005;46:806---23.

13.ValentiniNC,RamalhoNH,OliveiraNA.Movementassessment batteryforchildren-2:translation,reliability,andvalidityfor Brazilianchildren.ResDevDisabil.2014;35:733---40.

14.Hwang JL, Davies PL, Taylor WJ, Gavin WJ. Validation of schoolfunctionassessmentwithprimaryschoolchildren.OTJR. 2002;22:48---58.

15.D’Ávila-BacarjiKM,MarturanoEM,EliasLC.Recursose adver-sidades no ambiente familiar de crianc¸as com desempenho escolarpobre.Paideia.2005;15:43---55.

16.HalpernR,BarrosFC,HortaBL,VictoraCG.Estadode desen-volvimentoaos12mesesdeidadedeacordocompesoaonascer erendafamiliar:umacomparac¸ãodeduascoortesde nascimen-tosnoBrasil.CadSaúdePública.2008;24:444---50.

17.Moura DR, Costa JC, Santos IS, Barros AJ, Matijasevich A, HalpernR,etal.Naturalhistoryofsuspecteddevelopmental delaybetween 12and24monthsofageinthe2004 Pelotas birthcohort.JPaediatrChildHealth.2010;46:329---36. 18.Mc Donald L, RennieA, Tolmie J, GallowayP, McWulliam R.

Investigationofglobaldevelopmentaldelay.ArchDisabilChild. 2006;91:701---5.

19.MarturanoEM,FerreiraMC,D’Avila-BacarjiKM.Anevaluation scaleoffamilyenvironmentfortheidentificationofchildrenat riskofschoolfailure.PsycholRep.2005;96:307---21.

20.Srour M, Mazer B, Shevell MI. Analysis of clinical features predictingetiologicyieldintheassessmentofglobal develop-mentaldelay.Pediatrics.2006;118:118---39.

21.Williams J, Lee KJ, Anderson PJ. Prevalence of motor-skill impairment in preterm children who do not develop cere-bral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:232---7.

22.Goyen TA, Lui K. Developmental coordination disorder in ‘‘apparentlynormal’’schoolchildrenbornextremelypreterm. ArchDisChild.2009;94:298---302.