Ambergris as an overlooked historical marine resource: its biology and role as a global economic commodity

Cristina Brito (1,2), Vera L. Jordão (2) & Graham J. Pierce (3, 4)

(1) CHAM (Portuguese Centre for Global History), FCSH – NOVA /UAc, 1069-061 Lisbon, Portugal. cristina.brito@escolademar.pt

(2) Escola de Mar, TEC LABS, Campus FCUL, Campo Grande, 17494-016 Lisbon, Portugal. (3) CESAM & Departamento de Biologia, Universidade de Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal. (4) Oceanlab, University of Aberdeen, Main Street, Newburgh, Aberdeenshire, AB41 6AA, UK

Abstract

Ambergris is a rare substance produced in the intestines of sperm whales. It appears to result from an irritation caused by the beaks of the cephalopods on which they feed. The link between ambergris and whales, if not the mechanism by which ambergris is produced, has been addressed throughout history but, due to contradictory reports and fanciful explanations regarding its origin, only recently has been widely accepted. Since ancient times ambergris has been used for medicinal purposes and in perfumes, but its supposed exotic properties are an important reason for the European demand for this substance. Accounts about ambergris from places where Europeans sailed since the 15th century are numerous. In the 16th and 17th centuries there were no laws dictating who owned the ambergris found on beaches and many pieces were sold or traded, legally or illegally, from overseas to Europe. However, this product was always obtained in relatively small quantities. Recently, with the advent of industrial whaling dedicated to sperm whaling conducted by several nations in various parts of the world during the 19th and 20th centuries, ambergris acquired an importance of its own and was sold at very high prices. In the Azores, ambergris from hunted sperm whales was documented; the same applies for Madeira and the Portuguese mainland. Nevertheless being a product typically reported in whaling data and related to the economic exploitation of the sea, it is through the historical sources that its importance is clearly demonstrated.

Introduction: Ambergris, a product of sperm whales

“Não me pareceu também coisa fora de propósito tratar aqui algumas coisas das Baleias e do âmbar que dizem que procede delas”

“It also did not seem out of place to address some topics about Whales and the amber that some say comes from them”

Pero de Magalhães Gândavo, 16th century

Finding ambergris ashore on beaches is not a common event nowadays, and when it happens it is usually newsworthy. Today, when ambergris is found it gives rise to headlines such as “whale vomit found” or “a rare substance encountered on a beach” or even “floating gold ashore”. These examples reflect both the value of ambergris and the interest it generates among the general public, phenomena which, in fact, are not recent and be can tracked back centuries, with encounters with this mysterious material on beaches from all over the world being frequently reported. However the precise origin of ambergris was long shrouded in mystery.

Ambergris is a rare and extremely valuable odoriferous fatty substance that forms only in the stomach and intestines of the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), the largest of all odontocetes, and is later regurgitated or defecated. Sperm whales have a cosmopolitan distribution and for that reason ambergris may be found in waters of all over the world -although probably less so nowadays than before whaling due to depletion of sperm whales. The word “ambergris” comes from the old French ambre gris or grey amber as opposed to ambre jaune or yellow amber, which refers to the true resinous amber. The respective animal and vegetable origins of the two were discovered only in modern times (Clarke 2006; Rice 2009) and both were originally known as matter of unknown origin cast up by the sea.

The designation comes from an old Arabic word “andar” or “ambar”, which was used by the Byzantine-Greek physician Aetius as “ampar” and entered the English and Roman languages from the Spanish word “ambar” or “ambeur”, the French “ambre” and the Italian “ambra”. The original Arabic expression referring to “ambergris”, the grey amber, was “(h)ambar”, and, as seen above, this was commonly Latinized as “ambra” (Borschberg, 2001; Langenheim, 2003). Herein lies one of the main obstacles to unlocking the early modern economic and environmental history of ambergris and its trade. Historically, ambergris has

been confused with fossilized amber resin, and both were extensively traded by European seafaring nations, with the Far East (Borschberg, 2001). However, the importance of ambergris both in eastern and western cultures and economies has been evident since, at least, the medieval period.

Ambergris has been used since Ancient times for several purposes, including as incense, an aphrodisiac, laxative, spice, candles, as well as for cosmetics and medicines (Rice, 2009),. Ambergris was introduced into the western world by the Arabs, and its most common use since the Middle Ages has been as a key ingredient in the perfume industry and in medicine (Romero, 2006). It was prevalent as an important natural substance until the nineteenth century due to its aromatic properties (Monardes, 1989). Its use in perfumery is related with its physico-chemical characteristics, as ambergris is an animal-based substance that consists of a mixture of cholesterol and steroids with fixative properties (Langenheim, 2003). Most pieces of ambergris are in the form of an irregular roundish solid but easily breaks up. In colour they are pale yellowish to light grey on the inside, while the outer surface is dark brown with a varnished appearance. Fresh ambergris has the highly distinctive pungent odour of sperm whale faeces, but aged pieces have an almost pleasant musty or even musky aroma. The chemical properties of ambergris have been briefly reviewed by several authors; it is a non-volatile solid consisting mainly of a mixture of waxy, unsaturated, high molecular-weight alcohols (e.g. Rice, 2009).

The circumstances that induce the production of ambergris are still poorly understood but it is considered to result from the irritation provoked by the beaks (mandibles) of the whales’ cephalopod prey (Romero, 2006), although it can also occur when any non-digestible material passes to the intestine instead of being regurgitated (as would be more usual) (Clarke, 2006). This mechanism appears to be the most plausible given the rarity of this process, which apparently occurs in only one in 100 sperm whales (Clarke, 2006). Probably most ambergris is voided during defecation, unless they become too large to pass through the anus and in which case they are typically found in the large intestine or rectum if a sperm whale is captured. All these features make ambergris (Fig. 1) a rather rare natural substance. However, since it is less dense than sea water, so that it can be found floating at the surface of the oceans or washed up on beaches. Until its true provenance was determined, which only happened during the 20th century, the debate on its origin had been going on for centuries.

In the present paper we will address the early modern discussion on the origin of ambergris, and its historical use and economic value. This will be mostly supported by Portuguese written sources.

1. Early modern accounts on the origin of ambergris.

From the few edited works from the late medieval tradition referring to ambergris, it is worth highlighting Hortus Sanitatis printed by Jacob Meydenbach (1491) and translated into several languages. The edition consulted is an incunabulum found at the Library of Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid. According to J. Gomez Pérez’s catalog (1972/73), this is a printed version by Juan Priss, made in Strasburg before October 21st 1497. This will be referred to here as Hortus Sanitatis (1497).

Hortus Sanitatis (1497) was one of the most popular herbaria of its time, displaying representations and descriptions of living beings in this period of transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It is an extremely rich compilation of information, but also contains “misinformation”, mixing plants with animals as well as reality with the legendary. Rich in images, each volume has its own frontispiece and each chapter is also headed by an illustration. When it was published it served as an encyclopaedia of knowledge and folklore of plants, animals and minerals, combining natural history with themes traditionally found in herbaria and included the description of many mythical creatures. The section dedicated to animals includes significant detail of several marine animals with numerous woodcuts. However, here too, there is confusion between what is real and what is imaginary with equivalent entries for real and mythological creatures, in terms of their relative importance. Although this work clearly had a “scientific” purpose, with practical and direct application to medicine, it also addresses various events that are typical from the tradition of the medieval bestiaries.

Ambergris has its own entry in Hortus Sanitatis, as it has in several other medieval herbaria (Fig. 2). It states that this substance, according to some previous authors, is the fruit or the sap of a tree that grows in the sea, whilst according to others it is produced by a fish or is sea foam. The author of Hortus Sanitatis, besides these two hypotheses, also refers to ambergris as being generated underneath the ocean much like fungus grows on the earth. In an attempt to represent all these possibilities, an image related to these written descriptions shows a tree growing in the sea, a fish and a piece of ambergris .

By the 16th century the contributions of Portuguese travellers and explorers started to become known in Europe (Costa, 2009), and ambergris was amongst the exotic novelties found in the Atlantic and the New World. Interest in, and particularly the economic value of, this natural product as well as the lack of knowledge about its origin gave rise to fanciful

explanations, some of which prevailed for some time in these accounts. Although some writers believed ambergris came from whales, several others (e.g. Anonymous, 1842) attested that amber was produced at the bottom of the sea and rejected the “erroneous” view that it came from whales:

«It is like the production of amber, on which there were so many wrong opinions, as experience has shown, accrediting whales with what is produced on the bottom of the sea.»

Pêro de Magalhães Gandavo, referring to this natural product, writes in his chapter “De alguns peixes notáveis, baleias e âmbar que há nestas partes” abundantly about its possible origins, its different types and applications (Gândavo, 1980):

«It also did not seem out of place to address some topics about Whales and the amber that some say comes from them. (...) And many believe that this amber is nothing but whale dung: and it is called so by the local Indians in their own language, without means for better words. Others say, that it is sperm from the same Whale: but what is known to be correct (leaving these and other incorrect opinions aside) is that this fluid is born on the bottom of the sea, normally not everywhere: only on some parts of it, where nature sees fit. And being this liquid food for the whales, it is said that since it is so abundant, they get drunk and what washes off to the beaches is the excess they toss. And if it is not like this and it comes from the same whales through any of the previous ways that have been mentioned, it is believed to also exist in any other coast of these Kingdoms, for it can form in every part of sea. Moreover in this province that I speak of, an experiment has been done on many that came to shore and inside their bowels, a lot of amber was found, a piece already digested, for they had eaten it some time before. And in others it was found in their mouths still fresh and in all its perfection, it seemed like they had just eaten it that same moment before they died. The dung, when expelled, has no resemblance to amber, and it is not considered to be less digested than that of other animals. It seems clear, that the first opinion is not true, and the second cannot be either; because the sperm of these whales, which they call “balso”, which exists in great quantity in the sea, is said to be helpful in wounds and for that it is known to everyone that sails. This amber when it comes out, is loose like soap and scentless: but after a few days it hardens, and after that it becomes odoriferous as we all know. There are however two qualities of amber, one

brownish that they call grey and another one black: the brown is very fine and estimated to be of great value in all parts of the world: the black has lower odour carats, and it is used for very few things according to what has been done with it: but both are sold in this province, and nowadays some residents have enriched and enrich every hour as it is seen.»

In fact, throughout Portuguese coeval historiography, there are many hypotheses for the origin of this natural product. Garcia da Orta mentions it in “Do ambre” (Orta, 1987):

«Orta – Some have said it is whale sperm, and others say it is dung of a sea animal or it is sea foam, others have said a fountain discharged it from the bottom of the sea, and this one seemed better and closer to the truth. Avicena and Serapiam say it is generated in the sea (…) and when the sea is tempestuous it throws rocks out of itself and with them it tosses the amber, and this opinion is also according to the truth (…)».

The author (Orta, 1987) continues:

«Orta – Avicena and Serapiam say more, that some is swallowed by a fish they call “azel”, that dies after eating it, and being found under the sea, the men in the region grab forks and catch it, and take the amber, which is not good, and if some is [good] it is the one found near the ridge, and this one they say is good and pure; and this depends on the time it stays in the womb or near the ridge. Ruano – And what do you think about that, is it likely?

Orta - No (…) it is not to be believed that the fish will seek the so-called amber, because it will kill it: moreover, the amber is worthy of princes, that fish is likely poisonous, and the amber is so harmfull to it that will kill it [the fish].»

Carolus Clusius, in 1574, was the first author to deduce from the inclusions of squid beaks in ambergris that it was a product of the digestive tract of whales (Clusius, 1605; Rice, 2009). By 1667, eighteen different theories existed on this matter and various animals were considered producers of this substance – including seals, crocodiles and even birds. There were also several theories about the possibility of vegetable origin (A detailed revision of the several possible origins of ambergris can be found in Clarke, 2006). But since the 18th century the fact that ambergris was being found inside hunted sperm whales (Boylston, 1724) provided a definitive link to these animals. Although confirming that ambergris was found inside the sperm whale, Boylston (1724) concludes with the following sentence “Whether or not (from the Account above) the Ambergris be naturally, or accidentally produced in that Fish, I leave to the Learned to determine”, which indicates all the uncertainties surrounding this substance.

The subject is also discussed by other authors of the time (e.g. Dudley, 1724) stating: “Many and various have been the Opinions even of the learned World, as to the Origin and Nature of this precious Perfume”. Descriptions of ambergris found in sperm whales and the association of the matter with squid beaks start to be more frequent from this time onwards, probably related to the increased development of the European and American offshore whaling (Fawkener, 1791).

However, in the 19th century, in the middle of the scientific revolution taking place at that time (Darwin, Pasteur etc.) speculation on the origin and formation of ambergris was reaching its peak (Clarke, 2006; Read, 2013). Later, in the middle 20th century, ambergris was referred as “a very valuable product extracted from the sperm whale, was referred to as a consequence of a disease that originated in the large intestine and was expelled once in a while in the animal’s stool” (Cruz, 1945).

There were a number of hypotheses on how ambergris is formed. These include congealed froth of the sea, sulphurous and bituminous springs, a form of clay, congealed gum, resin from trees driving their roots into the sea, fragrant marine fungi or truffles, congealed dragon spittle, hardened sea sponge, bird guano, bee hives washed into the sea, fish liver, congealed whale semen, and excrement from fish or marine mammals. Most authors supported one variant or another of the bituminous spring theory and, in general, the whale was not seen as the creator of ambergris, but rather a metabolic destroyer of it (Borschberg, 2001).

The manner in which ambergris was traditionally harvested as flotsam, as well as the aforementioned confusion with fossilized resin amber, spawned a host of curious and sometimes baffling interpretations as to its origin. The empirical observation that ambergris was somehow linked to whales is featured in many explanations (reviews in Dannenfeldt, 1982; Clarke, 2006) but, throughout the written history of this substance, this is often ignored in favour of more acceptable, but sometimes quite fantastic, alternatives (Borschberg, 2001).

2. Atlantic and Indian sources for ambergris.

Given that sperm whales are typically a cosmopolitan species, meaning that they live in all of the world’s oceans, ambergris might be found along any coast all over the world (Clarke, 2006) as well as on the open sea. However, of course, it is more likely to be found in areas where sperm whales are most abundant, so it is quite probable that the Portuguese came

across this natural product frequently on their travels throughout the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

There are several accounts of ambergris, as well as black amber (piece of amber with a dark and not grey colour) which is also formed in the sperm whales intestines, across the seas and lands that the Portuguese navigated and explored, from African coasts to Brazil and several Atlantic islands (Coelho, 1990):

«(…) and sometimes amber is also found, and on many occasions more than two quintais were obtained». Quintais is a measure of unit equivalent to 100 kilograms, so 2 quintais I the same as 200 kilograms.

Frutuoso (2005) also mentions the occurrence of ambergris “nas cousas que outros dizem das duas ilhas de Forteventura e Lanzarote”:

« (…) these xilmeiros are poor cow breeders and shepherds in that flat and sandy land covered with low bushes, populated with huts, where these men settled with their women and children, accustomed to search for whale amber along the shore.»

Further on, when he “briefly tells the truth about the discovery of the islands of Cabo Verde” (Frutuoso, 2005):

«There is another island, named Santa Luzia, (...) it produces a lot of amber.» Some 16th and 17th Century Portuguese documents and reports mention ambergris from African coasts and the Atlantic archipelagos, as mentioned above, but such records are particularly common for Brazilian shores.

For instance, in the work Diálogos, by Brandão (1943), the subject of whales and the origin of ambergris arise:

«Alviano – I haven’t seen you talk about the whales, which surely are abundant considering the ambergris they throw to the shore.

Brandonio – Yes, they are (…) But thinking the whales throw the ambergris to the shore is a clear mistake; such a thing doesn’t happen, for the reason why it washes ashore is none other than that those same whales and other big fishes pick it up and eat it on the deep ocean waters, where it is born in big reefs, and with the strength needed to break it apart, some pieces get loose, some big, others small, and then the sea washes them to shore, where they are found; but a few days ago I was assured of something that happened on the limits of Rio Grande, indeed true, which contradicts everything I have said, about the origin of ambergris.

Alviano – Don’t keep it a secret then.

Brandonio – Two trustworthy men said they have seen, on the beaches of Rio Grande, on Cabo Negro, (...) [something like] a bread the size of an arm and as thick as one, that the sea had washed to shore, which ended with two twigs, one already broken and another one with some dry leaves, similar to those of the cypress tree, and spread along this piece, much like resin on a tree, three or four ounces of very good ambergris, for it seems that it is also generated in trees similar to that bread, on the bottom of the seas, producing ambergris much like resin is produced. If that is so, those who thought it originated in reefs are wrong, and those who said it was resin are right; the bread found confirms this.»

Such was the interest in this product and its frequency of occurrence on the shores of Brazil that several other authors mention it. Gândavo describes the numerous hypotheses about its formation and mentions that it is frequently found and enriches those who find it (Gândavo, 1980). Cardim (1980) also refers to whales and amber in Brazil:

«(…) so many times you see forty, or fifty of them [whales] together, it means they throw out the ambergris they find on the sea, on which they also feed, and that is why you can find some of it along this shore; others say that same sea washes it to shore with the storms and it is common to find some after a big storm. All animals feed on this amber, and much effort is needed after the storms to prevent it from being all eaten.»

Through time, two types of ambergris were known in Brazil, one white or grey (gris) and one black, both intestinal concretions exclusive to the sperm whale. The first one, more valuable and of great quality, could be found along the coast from Jaguariba to Ceará, whilst the second, a lot less aromatic and consequently less valuable, could be found from Pernambuco to Baía. In the Tupi language it was called “pirá-oçú-repotí”, which literally translated means “big fish dung”.

Salvador (1889) finished his chapter on whaling by addressing the ambergris around Bahia:

«But having killed so many whales, no amber was found in any of them, which is said to be their food, and they weren’t of the same size and species of another one that was found dead a few years ago in Bahia, with twelve

arrobas of very good ambergris in its mouth and intestines, not considering what the whale had vomited on the beach.»1

This citation is extremely important considering that Frei Vicente do Salvador shows some doubts regarding the fact that not all whale species can produce ambergris. This product is not found in most hunted whales (most probably right or humpback whales), only in sperm whales, which are also large whales, but have very different feeding habits (they are toothed whales and feed mostly on cephalopods). A number of toothed whale (Odontocete) species are largely teuthophagous, to a greater or lesser extent specialising on cephalopods, including the sperm whale, pygmy and dwarf sperm whales (Kogia spp.), bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus), pilot whales (Globicephala spp.), several species of beaked whales (Ziphiidae) and Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus). Many of these species can sometimes take fish prey and, ironically, this is probably best documented in sperm whales (e.g. Martin & Clarke, 1986). What does seem clear is that cephalopod beaks, being composed of chitin, are the least digestible part of the diets of these Odontocete species and that the beaks continue to accumulate in the stomach long after other remains of their prey have been digested.] Sperm whales eat squid of a wide range of sizes, from the giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) to squids that are only a few centimetres in the body (mantle length) like Histioteuthis spp. In the northern northeast Atlantic a high proportion of their diet appear to comprise a single squid species Gonatus fabricii (typical mantle length 20-25 cm) (e.g. Clarke, 1980; Santos et al., 2002).

Referring to the properties of ambergris, in 1580 Monardes (1989) dedicated a whole chapter to ambergris, its characteristics and medicinal uses, in his work regarding medicinal products brought from the western Indies. Monardes (1989) addresses the problem of its origin and discusses several known opinions such as the possibility that it is “the seed of the whale”, also presenting his own theory:

«(…) it is a kind of cement that exhales from fountains in special parts of the deepest sea, as we know they exist for such things like petroleum, naphtha, sulphur and many other.»

By this time, ambergris was widely used, not just in Europe but, of course, also throughout Asia (Borschberg, 2001). Garcia da Orta’s third colloquium, entitled “Colóquio Terceiro do Ambre” and entirely dedicated to amber, addresses the origin of this substance (Frade, 1963). As mentioned before, some say it was whale sperm, while others believed it to be animal dung or “a source that came from the bottom of the sea”, and Orta accepted this last hypothesis. The count of Ficalho, commenting on Orta’s words regarding ambergris, mentions

that it is produced in the sperm whale’s intestinal end, in the form of a concretion, which can be extracted or is expelled by the animal when it is being harpooned. Another work (Almaça, 1998) that also discusses the colloquia of this great Portuguese naturalist from the Renaissance also mentions some curiosities regarding this product, namely that a piece of ambergris the size of a man had been found and, many times, pieces of ambergris were filled with bird beaks (presumably, squid beaks) or shellfish shells.

This work on Asia’s natural history makes several references to ambergris, its occurrence and characteristics, as we have seen before, but also mentions different kinds of ambergris and its qualities. Orta (1987) writes in one of his dialogues:

«Ruano – Does it exist in places other than Ethiopia and its coast?

Orta – Some is found in Timor, but very little and in small amounts; I am told it has also been found in Brazil; and a piece was found in Setúbal in the 30s; but you can’t take these small findings for granted, since they happen rarely and in small amounts.

Ruano – So tell me, why can’t it be whale sperm or dung?

Orta – That doesn’t make sense, because the whale and its oil, which I have seen, smell very badly, not like amber; and besides there are whales in many capes and no amber is found, just like on the Coast of Spain and Galicia; and for the same reason it is proved that it is not sea foam, otherwise wherever there were shallow waters and wind there would be sea foam, and what is said about it being eaten by fish I refuted and have proven before that it is false (…) Ruano – Which one is the best choice?

Orta – The whiter the better, obviously, either brownish, or with seams of various colours, some white and others brownish, and very light weighted; and to prove this, if you stick a pin in it, the one that leaks more oil through the hole is the best. The black one is very bad, I had a piece that I bought cheap, and it only had a light scent (…)».

The author talks about this subject in several other sections of his Colloquia, which demonstrates the importance of the subject and the product in several oceanic regions where it occurred and not only the Atlantic Ocean.

Luis de Camões also mentions the Indian Ocean’s ambergris and its properties. In two different parts of the “Lusíadas”, Luís de Camões refers to the grey mass or amber. In Canto VI, stanza 25: “The house is filled with scents from the rich mass/which is born on the sea, and smelling it reminisces of Arabia”. In Canto X, stanza 137: “Other islands, in a sea also ruled/by

you, located on the coast of sandy Africa/from which the most perfect scent is exhaled by/the precious mass, hidden from the world”. The mass to which the poet and other ancient Portuguese authors refer is ambergris, a substance frequently used in perfumery until the middle of the twentieth century proceeding from the sperm whale’s intestines: «it is a concretion or calculus that forms within them» (Osório, 1906). Considering it was found floating on the seas of the eastern coast of Africa and not knowing where it came from, many, like Luis de Camões, thought it was born in the sea. Alves (1994) also mentions that the ambergris is a solid, oily substance with musky scent, used as perfume and medicine. He also states that ambergris from Sofala, on the Arabian and Ethiopian coasts (in less quantity on the latter location) sharpens comprehension, freshen the memory and is also good to relieve or cure spasm, paralysis and gout.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, documents and commercial intelligence reports rarely, if ever, mention the presence of ambergris in insular Southeast Asia. Nevertheless, in Southeast Asia, this substance was found around the coastal regions of Borneo, Celebes, the Moluccas, and Timor. Some Dutch sources also mention the northern coast of New Guinea as a hotspot for finding ambergris. Ambergris found around insular Southeast Asia received far less attention. Aside from the description by Garcia da Orta about the availability of Timorese ambergris, there are only a few other sources (Borschberg, 2001).

3. Use and value of ambergris.

Ambergris is just one of many animal products that have been exploited for medical purposes throughout history (Lev, 2003, 2006). In fact, since ancient times animals and products derived from different organs of their bodies have constituted part of the inventory of medical substances used in various cultures. But besides its applications, ranging across pharmacology and perfumery through food and drink flavouring (Borschberg, 2001), its high value is also due to its rarity. Contrary to the prevalent notion, ambergris is hardly ever found on beaches. In the present work, we found only about twenty five historical events of ambergris (being found by chance ashore or floating or inside whales) from Portuguese sources spanning over five centuries. Most ambergris is recovered directly from whale carcasses (Rice, 2009).

Ambergris is not of local occurrence, even though it has been occasionally found, over centuries, on European shores, such as Portugal, Spain, France and England. It is rather exotic, in most of the places where it is typically used as an important remedy. From the 10th to the

18th century it was said that ambergris may cure sore throat, heart disease, paralysis, cough, cardiac diseases and hysteria (Lev, 2006). In addition, it was commonly used as perfume and scent fixer. It was really very valuable, since ancient times in the Mediterranean world, and through the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe (Read, 2013) up to the 20th century, all around the world (both in industrial cultures as well as in indigenous ones). Present day medical uses of ambergris are documented and, for instance, in the Levant, it is used as a potency reinforcement and kidney disease treatment most probably due to its diuretic and laxative properties (Lev, 2003).

As an exotic animal substance, ambergris was imported from distant lands via distinct trade routes, most of which were true monopolies of commerce (Lev, 2006). It was brought from Asia, and Africa by sea and land, but also from the Americas; it was a merchandise in transit at several ports all over the world, being bought and sold by Western traders who shipped it on to Europe where is was in high demand.

Due to being rarely found and its high value (e.g. Romero, 2006), each time someone encountered ambergris on beaches the event would be recorded (Coelho, 1990):

«Further ahead lies the Island of Tamara, or Island of Amber, given that great amounts of it were found, some fifty years ago, by a certain man named Braz da Costa de Saldanha, born in the city of Lagos, a poor man that sailed an old boat with very few men, whom he sent out to land to collect some wood, and the sailors, without realizing, brought back a boat filled with amber, thinking it was a kind of resin used to caulk the ships, and the poor man benefitted so little from it, although it is said it weighed more than two quintais, which the man spent in the first few years (…)».

Another example for the West African coast (Coelho, 1990):

«There (Roza Island, Guiné) amber has been found frequently and in large amounts, as stated by captain Manoel de Mello, my uncle, who once bought eighty-four pounds2 out of the two quintais found, and on another occasion he bought ten [pounds], on both occasions there were many buyers, who bought it so cheap, especially the first time, that they could say they had found it themselves. This good [the amber] is worthy of good remarks, because on my first year in Guiné [the amber] provided what I needed to begin my life, selling there a dress I brought from my parent’s house in exchange for amber, and this

was the first of all things I got in Guiné, without needing to be taken care of or supported by a relative.»

Another description from Brazil (Gândavo, 1980):

«Amber is also found throughout this coast, tossed by the sea on stormy days with spring tides, and many people send their slaves to the beach to collect it, and sometimes it happens that some of them get rich from what their slaves find, as well as what they collect from the Indians, depending on luck and fate..»

Again, Brandão extensively describes the characteristics and occurrence of ambergris as well as its importance to people and its high economic value. Several Portuguese living in Brazilian coastal areas sent their servants to the beaches to look for this valuable product, and even though many did not immediately acknowledge its value, there were always those who understood its importance and used it as merchandise or for exchange.. A long description by Brandão (1943) allows us to understand the economic importance of amber (both grey and black) to the Portuguese communities in Brazil. This natural product was eagerly sought, had great commercial value, producing significant financial returns for the time (Brandão, 1943):

«Many enrich in this Brazil with sums of amber, found on the beach, some in great quantities, others in small; a certain resident saw so much of it that he doubted it was really amber, and so he identified it as tallow or resin, and with it he started caulking a boat he had kept on a shipyard, and he continued to work on it until some of his companions, seeing him so busy, told him he was mistaken, and even though he had already spent a lot, he still had plenty left.» The author continues (Brandão, 1943):

«However, before I answer what you asked, I will tell you a story of what happened a few days ago in this County about the origin of amber. A man went fishing to a bay located in the Captaincy of Rio Grande, and wanting to sail on a raft, he didn’t have a rock he could use as an anchor, and looking around towards the beach he saw one that seemed appropriate for the task, and after grabbing it he tied a rope around it and sailed away; arriving at the site he wanted, he threw the anchor, which floated as if it was made of cork; and since that rock couldn’t be used as an anchor, for it floated, he returned to the beach at the same time a friend was arriving, also to fish on another raft, and telling him what had happened with that floating rock, the other one, more clever than him, told him he needn’t worry, because he wasn’t feeling well and wasn’t

going to fish, so he gave him his own anchor. The first one accepted the offer and sailed off to fish with it, leaving behind that floating rock in the hands of the second, who immediately recognized it as amber, and he disappeared carrying it, benefitting from its value, because it weighed almost one arroba.» Another example, also for Brazil, appears in Frei Vicente do Salvador when the author refers to Martim Soares Moreno, captain of Ceará, to whom the king attributed the Order of Santiago and provided a small stipend, mentioning another of his wordplays: “(…) that is why God gives you a lot of amber (in Portuguese, “âmbar”) along that beach, with which you can easily kill the hunger (“hambre”)”. This is a pun on the old words for amber and hunger: “that is why God gives you a lot of amber (“ambre”) along that beach, with which you can easily kill the hunger (“hambre).

It was an extremely valuable product, for example a value of £9000 in 1612 was attributed to a piece of approximately 36 kilograms found on a beach in Bermudas (Romero, 2006). No laws existed to dictate ownership of amber found on the beach, so it belonged to whoever found it. Several pieces were sold or traded, legal or illegally, as they were found.

Its high value was also due to the important medicinal properties it possessed that were commonly applied (Monardes, 1989):

«(…) a passenger from Florida gave him a very good piece of ambergris, saying he had obtained it in Florida, I took the piece and broke it, and ambergris poured from inside it, with very good colour, while the outside was black, I asked him where he had found it and he said it was from the coast of Florida: and the Indians were those who collected it the most: because they used it, for their pleasures and contentment, applying the oil on their faces, and other parts of their bodies, for its nice scent: it surprises me to see such good amber coming from our Western Indies (…) that they now bring such great ambergris, so valuable in the world, used for the body’s health, and needed to heal or treat so many different illnesses, as we will address: it’s something very useful to men as treatments, embellishment and pleasure.»

During the 16th and 17th centuries it was of royal interest in Europe (Hansen, 2010), and was commonly used as a prestigious gift (Cazeils, 2000). For that reason its value increased exponentially and as early as the 16th century, in Portugal, ambergris is mentioned in inventories of wills, together with gold and silver (ANTT, 1574). Moreover, several charters from the 16th century indicate that the Portuguese Queen should receive all the ambergris, as well as seed pearls, musk, cloths, porcelain, spices, ginger and other goods, coming from overseas.

In 1511, a charter provided for the receiver of the Casa da Índia to deliver the Queen all the ambergris and pearls that had recently come from India (ANTT, 1574). Another one, from 1573, indicated that the large amount of 98 ounces and 2/8 of ambergris (corresponding to 2.778 kilograms) coming from India to the Queen, was worth 300525 réis (ANTT, 1574). Réis is a old Portuguese currency that lived until the beginning of the 20th century; direct conversion to present-day currency would give the value of 1.5 Euro, however due to inflation and long term changes in economical patterns the real value would be around the 10.000 Euro. From all charters found, more than five kilograms of ambergris were delivered to the Queen during this period. Leite (1938) indicates that, from 1587 to 1594, the Jesuits in Brazil sent to European amount of ambergris that all together rendered a large sum of money that they used for the purchase of books.

Since that time, and moving forward to the large-scale commercial whaling in the late 19th century (both during offshore and land-based whaling), ambergris remained scarce and prices were generally conditioned by the demand of traders or buyers (Borschberg , 2001) as it was sought by nobles, collectors, druggists (Fawkener, 1791), apothecaries and perfumers (Cazeils, 2000). Undoubtedly wealth has been gained through ambergris, not only on tropical shores but also along the North America and European coasts, and even northward toward the polar seas. Another reference to the value of ambergris comes from a ship’s doctor who sailed on a factory ship to the south Atlantic in the 1950s. He refers to the catching target (“quota” here as a target and not a limit) set by the company, of 131000 barrels of oil and 3200 tons of by-products; they mainly targeted baleen whales (Robertson, 1956):

«For example, one pound of ambergris, if we were lucky enough to kill any sperm whales with bad guts, would count the same as a ton of meat—meal toward the quota, but since ambergris was worth at the time a little more than the fine ounce of gold, it was not a bad exchange, from the owners’ point of view, for a ton of meat.»

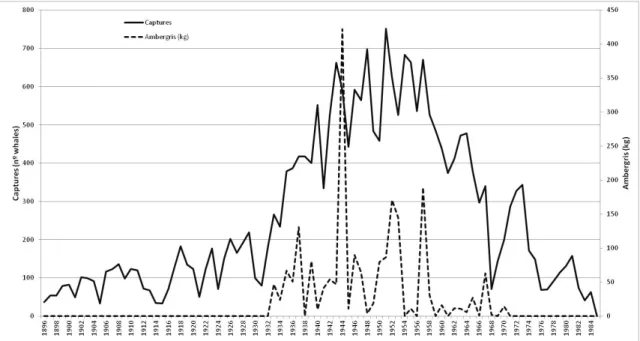

Ambergris was sometimes found on cargo lists and merchant records in the modern period (Borschberg, 2001). However, the only modern fishery in which every whale landed was thoroughly searched for ambergris was that which operated from the island of San Miguel in the Azores from 1934 to 1953. There, ambergris was found in only 19 of 1933 whales or in 0.98% of the cases (Clarke, 2006). Data from the national fishing statistics (Anonymous, 1899, 1897-1942, 1943-1964, 1965-1968, 1969-1985) are available for the entire land-based whaling period in the Azores (Brito, 2011), which includes all the years between 1896 and 1985 (Fig. 3 and 4).

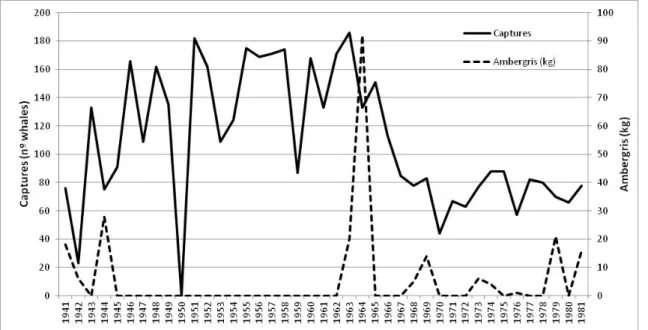

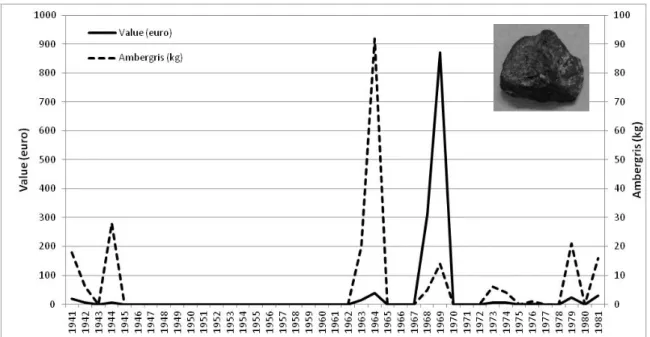

In the Madeira archipelago, land-based whaling occurred over a shorter period during the 20th century, from 1941 to 1981, and, again, ambergris was obtained (Fig. 5 and 6).

In the Portuguese mainland, land-based whaling also took place, during two separate periods in the 20th century, between the years 1925 and 1927 and between 1944 and 1951. In this fishery both sperm and baleen whales were captured, and for most years we cannot account for the exact number of sperm whales captured (except for the years marked with an arrow in the figure), and consequently the amount of ambergris obtained was much less than in the islands (Fig. 7).

According to data for the Portuguese archipelagos, and with just one exception, during the 20th century the value of ambergris peaked when it was scarcer (for example, the peaks in 1948 and 1966 for the Azores, and the 1969 peak for Madeira). This product was obtained in relatively small quantities (for instance, in the Azores between 1948 and 1970, approximately 750 kg were obtained from the capture of more than 23000 whales) and for that reason it was sold at very high prices. As a comparison, in Spain, the value of ambergris increased 18 times from 1968 to the end of whaling in 1980 (Hansen, 2010). As in other local or global markets, at any given moment in history, a short supply and a high demand lead to a strong economic valuation of a product. This is what happened with ambergris that, despite a very low level of production compared to oil and meat during the whaling period, was one of the most profitable products obtained from this activity (Hansen, 2010). However, it is difficult to establish if there was a direct exploitation, a market or an organized trade in early modern and modern times strictly directed focused on ambergris. It seems more plausible that over the centuries, and in particular regions, there were particular points in time when this product was harvested and from which an occasional trade with a considerable profit resulted. Thus, whenever and wherever ambergris was available it entered the established trading routes for exotic and highly sought-after products.

Discussion: The global dimensions of ambergris and the importance of its trade

In many ways an “ethereal” substance, ambergris is rarely found in the wild and it has left few material traces over time. As in the case for several other products or substances arriving from the overseas (Norton, 2008), and during most of the 16th century, ambergris did not appear as a systematic import, nor was it commonly registered in trade records. Nevertheless, it is known for being the second most treasured commodity coming from sea, after the pearls.

We have however, numerous written records and discussions on its origin, of its geographic presence, its use in several places and cultures and its ecological and economic importance. The undeniable link of ambergris to whales (specifically sperm whales) is present throughout its history, despite numerous contradictory reports and perhaps fanciful explanations. References appear from Clusius (1605), with the testimony of Marel which refer to its origin in the intestines of whales as a result of digestion of cephalopods, their primary prey, to Melville when the author mentions the popular applications of ambergris. Clearly, t he importance of ambergris in the culture and economy of the East and West since Antiquity and the Middle Ages is evident, and its most common use throughout history was as a key ingredient in the production of medicines and perfumes.

Ambergris has had, historically, great importance due to its typical applications but also due to its medical properties and exotic nature. Very valuable and highly valued, also due to its rarity, ambergris was always sought by those who wish to study and collect nature (Findlen, 1996; Ogilvie, 2006) as well as by those who wish to profit from it. Moreover, ambergris emerged as one of the few products European traders, and particularly the Portuguese, could supply with good and reliable profit margins over time. Even though outrageously priced and lucrative as this commodity might have been, its supply was consistently scarce, and the overall profit from the trade in ambergris was dwarfed by the gains from other bulk merchandises such as textiles and spices (Borschberg, 2001).

Accounts of ambergris reaching Europe from all oceanic coasts where the Portuguese and other European nations sailed over the centuries were numerous and very curious, as they remain today. Early modern accounts refer mostly to the fantastic and mythological aspects of the product. In recent times, with some frequency, newspapers are reporting unusual events of lucky people discovering ambergris on beaches all around the world. The interest in this natural product, as well as the historical ignorance regarding its origin gave rise to many amazing stories, some of which persisted for some time and, true, this curiosity still persists. However, even today, it is the economic value that makes it really attractive for those who find it.

Obtaining ambergris, in most cases, is an activity of pure fortune. It is not a dedicated activity of harvesting the natural resources; it is not fishing nor hunting nor capture. Simply collecting, in fact, casual gathering of what the sea and its large animals have to offer, even though at times whale guts could be actively searched for ambergris.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, there were no laws dictating who owned the ambergris found on beaches. By that time, whales were a “royal fish”, and so all that came from them and

might be found at the sea or shorelines, should also have belonged to the Crown. However if it was found, pieces of ambergris were quickly stored and marketed by those who knew and recognized its value. Pieces were sold or traded, but there was no system of trade implemented and ambergris was not often recorded when traded.

More recently, with the advent of industrial whaling in the 19th and 20th centuries dedicated to the capture of whales and carried out by several nations in various regions of the Atlantic, ambergris has acquired a value in itself and its presence became more regular in reports of whaling activities. However, until its use had become obsolete by the middle 20th century, its trade happened in a non-systematic manner.

Nowadays, with international mechanisms for the conservation of large whales and the worldwide ban on catching whales (with some exceptions of varying legality), we can only expect sporadic and fortuitous encounters with this natural material when pieces of ambergris are found on a beach (or recovered from a stranded whale). That is, at least, until the natural populations of sperm whales recover their former high abundance (see Whitehead, 2002 for a discussion of abundance of sperm whales over time), and until these giants of the seas can consume sufficient prey to excrete large pieces of ambergris.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the help and comments of Dante Teixeira as well as the comments of two reviewers. CB was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through a post-doctoral fellowship (SFRH/BPD/63433/2009). GJP thanks the University of Aveiro and Caixa Geral de Depósitos (Portugal) for financial support.

References

Almaça C. (1998) Baleias, Focas e Peixes-Bois na História Natural Portuguesa. Lisboa: Museu Bocage.

Anonymous (1842) Relação do novo caminho que fez por terra e mar, vindo da Índia para Portugal, no anno de 1663, o Padre Manuel Godinho da Companhia de Jesus. 2nd edition. Lisboa: Sociedade Propagadora dos Conhecimentos Úteis.

Anonymous (1943-1964) Industrial Statistics. Lisbon: National Institute of Statistics. Anonymous (1961) Circular do Grémio dos Armadores da Pesca da Baleia. Lisboa.

Anonymous (1965-1968) Agriculture and feeding statistics. Lisbon: National Institute of Statistics.

Anonymous (1969-1985) Fishing Statistics. Lisbon: National Institute of Statistics.

Anonymous (1897-1942) Statistics of the maritime fisheries of the continent and adjacent islands. Ministry of Navy: Imprensa Nacional de Lisboa.

Anonymous (1899) Annual statistics of Portugal. General Direction of Statistics: Imprensa Nacional Lisboa.

ANTT (1574) Inventário e conta que deu Diogo da Rocha de Sá, do dinheiro, âmbar, prata e maius fazenda que tinha recebido de Mem de Sá’, Cartório dos Jesuítas, Mç 6, Nº 5.

Alves M.S. (1994) Dicionário de Camões. Lisboa: Universitária Editora.

Borschberg P. (2001) O comércio de âmbar cinzento asiático na época moderna, séculos XV a XVIII. Fundação Oriente 8, 5.

Boylston (1724-1725) Ambergris found in whales. Communicated by Dr. Boylston of Boston in New-England. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 33, 193.

Brandão A.F. (1943) Diálogos das Grandezas do Brasil. 2nd edition. Academia Brasileira, with notes by Rodolfo Garcia and introduction Jaime Cortesão. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Dois Mundos Editora, Lda.

Brito C. (2011) Medieval and early modern whaling in Portugal. Anthrozoos 24 (3), 287-300. Cardim F. (1980) [1540?-1625] Tratados da terra e gente do Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Ed. Itatiaia, Universidade de São Paulo

Cazeils N. (2000) Dix siécles de pêche à la baleine, Éditions Ouest-France.

Clarke M.R. (1980) Cephalopoda in the diet of sperm whales of the southern hemisphere and their bearing on sperm whale biology. Discovery Rep 37, l-324.

Clarke R. (2006) The origin of ambergris. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 5, 7. Clusius C. (1605) Exoticorum libri decem. quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum...: Item Petri Belloni Observationes, Reprod. de la ed. de: Anvers : Ex officina Plantiniana Raphelengii. Coelho F.L. (1990) Duas descrições seiscentistas da Guiné. Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa da História.

Costa P.F. (2009) Secrecy, ostentation, and the illustration of exotic animals in sixteenth-century Portugal.

Annals of Science, 66 (1): 59-82.

Cruz F. (1945) A pesca da baleia. Boletim da Pesca 9, 31.

Dannenfeldt K.H. (1982) Ambergris: The search for its origin. Isis 73 (268), 382-197.

Dudley P. (1724-1725) An essay upon the natural history of whales, with a particular account of the ambergris found in the sperma ceti whale. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 33, 256-269.

Fawkener W. (1791-1725) On the production of ambergris. A communication from the committee of council appointed for the consideration of all matters relating to trade and foreign plantations; With a prefatory letter from William Fawkener. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 81, 43-47.

Findlen P. (1996) Possessing nature: Museums, collecting, and scientific culture in early modern Italy. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Frade F. (1963) Os animais e os seus produtos nos Colóquios de Garcia de Orta. Garcia da Orta, Revista da Junta de Investigação do Ultramar, 11 (4), 712-713.

Frutuoso G. (2005) [1522-1591] Saudades da Terra. Ponta Delgada: Instituto Cultural de Ponta Delgada.

Gândavo P.M. (1980) [1550-1557] Tratado da terra do Brasil; História da Província Santa Cruz. Belo Horizonte: Ed. Itatiaia, Universidade de São Paulo.

Hansen F.V. (2010) Los balleneros en Galicia (siglos XIII al XX). Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza, Colección Galicia Histórica.

Hortus Sanitatis (1497) De herbis et plantis. De animalibus & reptilibus. De fluvibus et

volatilibus. De avibus et volatibus. De piscibus et natatilibus. De lapidibus et in terra veris nascen tibus… Tabula Medicinalis cum Directório Generali per Omnes Tractatus. Estrasburgo: Johannes Pruess.

Langenheim J.H. (2003) Plant Resins: Chemistry, evolution, ecology and Ethnobotany. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press.

Leite S. (1938-1950) História da Companhia de Jesus no Brasil. Lisboa & Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Portugália & Civilização Brasileira.

Lev E. (2003) Traditional healing with animals (zootherapy): medieval to present-day Levantine practice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 85, 107-118.

Lev E. (2006) Healing with animals in the Levant from the 10th to the 18th century. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2, 11.

Martin A.R. and Clarke M.R. (1986) The diet of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) captured between Iceland and Greenland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 66 (4)79-790.

Monardes N. (1989) [1565-1574] La historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Índias Occidentales. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, D.L.

Norton M. (2008) Sacred gifts, profane pleasures: A history of tobacco and chocolate in the Atlantic world. Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press.

Ogilvie B.W. (2006) The Science of Describing. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago

Press.

Orta G. (1987)[1563] Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da Índia, Facsimile reprodution of the 1891 edition directed by Conde de Ficalho. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, Casa da Moeda.

Osório B. (1906) A fauna dos Lusíadas. , Jornal Sciencias Mathematicas Physicas e Naturaes, Academia das Sciencias 27, 197.

Read S. (2013) Ambergris and early modern languages of scent. The Seventeenth Century, 28 (2): 221-237.

Rice D.W. (2009) Ambergris. In Perrin W.F., Wursig B. and Thewissen J.G.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, pp. 28-29.

Robertson R.R. (1956) Of whales and men. MacMillan and Co Ltd.

Romero A. (2006) More private gain that public good: whale and ambergris exploitation in 17th century Bermuda. Bermuda Journal of Archaeology and maritime History 17, 6.

Salvador F.V. (1889) [1627] História do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Publicação da Biblioteca Nacional. Santos M.B., Pierce G.J., García Hartmann M., Smeenk C., Addink M.J., Kuiken T., Reid R.J., Patterson I.A.P., Lordan C., Rogan E. and Mente E. (2002) Additional notes on stomach contents of sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus stranded in the NE Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 82, 501-507.

Whitehead H. (2002) Estimates of the current global population size and historical trajectory for sperm whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series 242, 295–304.

Figures

Figure 2 – Representation of amber growing in a tree from the bottom of the sea in Hortus Sanitatis (1491). Courtesy of the Library of the National Museum of Natural History, Madrid.

Figure 3 – Number of captured sperm whales and amount (in kilograms) of ambergris obtained during the period of the Azorean land-based whaling.

Figure 4 – Amount (in kilograms) of ambergris obtained during the period of the Azorean land-based whaling and its value converted from old Portuguese currencies to Euros. Small lump of ambergris obtained in Azorean whaling activities; courtesy of the Sperm Whale and Squids Museum by Malcolm Clarke (Portugal).

Figure 5 - Number of captured sperm whales and amount (in kilograms) of ambergris obtained during the period of the Madeira land-based whaling.

Figure 6 – Amount (in kilograms) of ambergris obtained during the period of the Madeira land-based whaling and its value converted from old Portuguese currencies to Euro. Small lump of ambergris obtained in Madeira whaling activities; courtesy of the Madeira Whaling Museum (Portugal).

Figure 7 - Number of captured whales and amount (in kilograms) of ambergris obtained during the period of the Portugal mainland-based whaling. Note: Data for years marked with an arrow refer only to number of captured sperm whales, data for all the other years refer both to sperm and baleen whales.