Ana Luiza Curi HallalI

Sabina Léa Davidson GotliebII

Liz Maria de AlmeidaIII

Letícia CasadoIII

I Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Pública. Faculdade de Saúde Pública (FSP). Universidade de São Paulo (USP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil

II Departamento de Epidemiologia. FSP-USP. São Paulo, SP, Brasil

III Divisão de Epidemiologia. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil.

Correspondence: Ana Luiza Curi Hallal R. Felipe Schmidt, 774 – Centro 88010-002 Florianópolis, SC, Brasil E-mail: anacuri@gmail.com Received: 11/17/2008 Revised: 3/2/2009 Approved: 4/14/2009

Prevalence and risk factors

associated with smoking among

school children, Southern Brazil

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To estimate the prevalence of smoking among students and associated factors.

METHODS: Secondary data from the Vigescola Survey, conducted in the cities of Curitiba, Florianópolis and Porto Alegre (Southern Brazil) between 2002 and 2004, were used. Sample comprised 3,690 school children, aged between 13 and 15 years, and enrolled in the 7th and 8th grades of primary school and 1st grade of high school, in public and private schools. Weighted proportions and odds ratio (OR) were estimated and multiple logistic regression was used to analyze results.

RESULTS: Smoking prevalence rates were 10.7% (95% CI: 10.2;11.3) in Florianópolis, 12.6% (95% CI: 12.4;12.9) in Curitiba and 17.7% (95% CI: 17.4;18.0) in Porto Alegre. Risk factors associated with smoking among schoolchildren in Curitiba were: female sex (OR=1.49), smoking father (OR=1.59), smoking friends (OR=3.46), exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke outside the home (OR=3.26), and having some object with cigarette brand logos (OR=3.29). In Florianópolis, variables associated with smoking were: female schoolchildren (OR=1.26), having smoking friends (OR=9.31), exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke at home (OR=2.03) and outside the home (OR=1.45) and having seen advertisements on posters (OR=1.82). In Porto Alegre, variables associated with tobacco use among school children were: female sex (OR=1.57), aged between 14 years (OR=1.77) and 15 years (OR=2.89), smoking friends (OR=9.12), exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke at home (OR=1.87) and outside the home (OR=1.77) and having some object with cigarette brand logos (OR=2.83).

CONCLUSIONS: Smoking prevalence among school children aged between

13 and 15 years is high. Factors signiicantly associated with it and common to

the three capitals were as follows: having smoking friends and being exposed to environmental smoke outside the home.

DESCRIPTORS: Smoking, epidemiology. Adolescent. Students. Risk Factors. Cross-Sectional Studies.

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco is the main avoidable cause of death worldwide. Each year,

approxi-mately ive million people die from tobacco-related diseases and, if the current

trend of consumption continues, it is estimated that there will be eight million deaths per year by 2030, of which 80% will occur in developing countries.17

tobacco use among both adults and adolescents were inexistent, developed the Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS). This system aims to help 193 WHO member states to collect data on tobacco use and, in this way, improve the capacity that countries have to plan, implement and assess smoking prevention and control programs.4

The Inquérito de Tabagismo em Escolares (Vigescola),

also known as Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS)

and Encuesta Mundial sobre Tabaquismo en Jóvenes

(EMTJ) in English and Spanish, respectively, is one of the components of this surveillance system. In Brazil,

the Vigescola was applied for the irst time in 2002.3

The present study aimed to estimate the smoking preva-lence in students the some factors associated.

METHODS

In a cross-sectional study, secondary data from the

Inquérito de Tabagismo em Escolares (Vigescola),

performed in the cities of Curitiba (PR) and Porto Alegre (RS), in 2002, and in Florianópolis (SC), Southern Brazil, in 2004, were analyzed. In Curitiba and Florianópolis, sample selection was made in day classes exclusively, while in Porto Alegre, in day and evening classes.

Students aged between 13 and 15 years were analyzed, all enrolled in grades 7 and 8 of primary education and grade 1 of secondary education in public and private schools. The probability of a school belonging to the sample was proportional to the number of students enrolled in the above mentioned classes. In each of the

schools selected, from one to ive classes, depending

on the school population size, were randomly selected, using systematic random sampling.4

All students from the classes selected who were present on the day the questionnaire was applied were invited to participate, regardless of their age,4 totaling

4,844 students. Of these, 3,690 (76.2%) students aged between 13 and 15 years were analyzed.

Information for Vigescola was collected using an anonymous, self-reported questionnaire.3,4 Variables

analyzed were school children’s tobacco consumption habit, sex, age and school grade; parents’ and friends’ tobacco consumption habit; exposure to second-hand smoke in and outside the home and exposure to anti-smoking messages and cigarette advertisements. Students who, at the moment of completing the questio-nnaire, answered that they had smoked on one or more days on the last 30 days were considered smokers. School children were grouped into two categories in terms of smoking habits of friends: those who reported some, most or all their friends smoked and others who

reported having no smoking friends. Students who answered that, on the last seven days, people smoked in their presence on one or more days, whether in or outside the home, were considered to be exposed to second-hand smoking. In terms of exposure to the media, students who reported having seen messages associated with cigarettes on the last 30 days were considered exposed.

Response rate of schools in Curitiba was 92.0%; among students, 82.9%; and the overall rate was 76.2%. In Florianópolis, these values were 96.0%, 84.1% and 80.8%, respectively, while in Porto Alegre, 96.0%, 87.1% and 83.6%, respectively.

Considering the values of response rates observed, in addition to the fact that schools, classes and individuals studied did not show the same probability to participate in the sample, weighted estimates were used.

Multiple logistic regression was applied to ind out

the factors associated with smoking.8 The dependent

variable was presence of smoking and the reference category for each independent variable was lower risk of smoking, in the age group analyzed, according to the literature on the subject. Odds ratio (OR) was the association measure estimated. In addition, 95%

conidence intervals were adopted.

First, univariate analysis was performed to assess the effect of each variable individually, when variables that showed a descriptive p value of up to 0.25, i.e. p<25% in the univariate model of binary logistic regression, were selected for the model.6

Joint analysis of factors selected in the previous stage was performed using stepwise forward logistic regression. The modeling process began with the “sex” variable, and the remaining variables were included

in the model, one by one, until the inal model was

achieved.8

There was statistical signiicance when the descriptive p value observed was lower than or equal to 0.10, i.e. p ≤ 10%. The p value adopted aimed to identify signiicant

factors common to the three capitals. Thus, the variable

whose p value was p ≤10% was considered statistically signiicant in relation to the reference category.

The Vigescola project was approved by the Research

Ethics Committee of Faculdade de Saúde Pública da

Universidade de São Paulo (São Paulo University

School of Public Health).

RESULTS

The proportion of participants compared to the total

Vigescola sample varied among capitals: 84.2% in

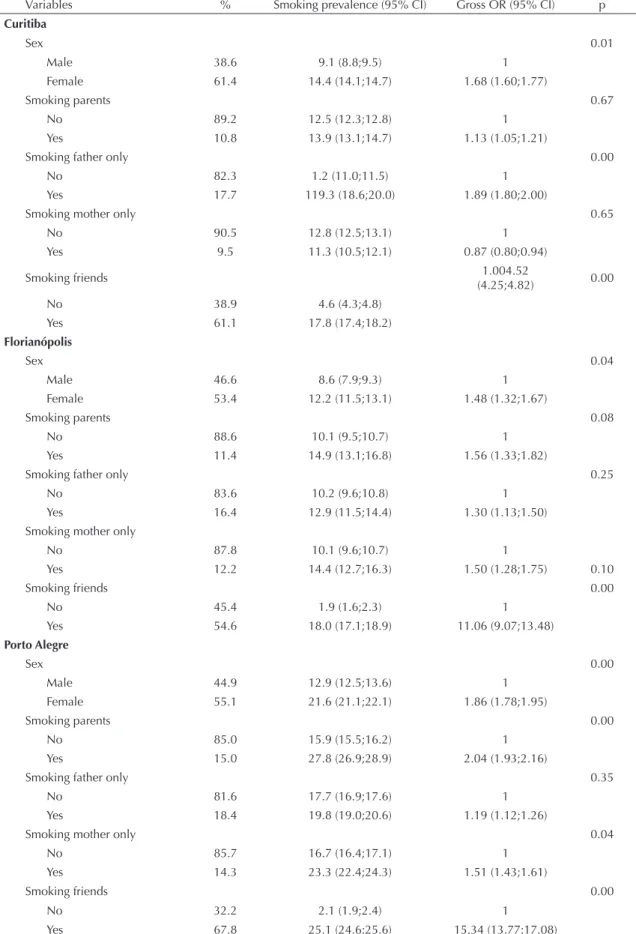

Table 1. Proportional distribution of school children, smoking prevalence and gross OR with respective 95% confidence intervals, according to sex, smoking in the family and among friends. Municipalities of Curitiba, Florianópolis and Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil, 2002-2004.

Variables % Smoking prevalence (95% CI) Gross OR (95% CI) p

Curitiba

Sex 0.01

Male 38.6 9.1 (8.8;9.5) 1

Female 61.4 14.4 (14.1;14.7) 1.68 (1.60;1.77)

Smoking parents 0.67

No 89.2 12.5 (12.3;12.8) 1

Yes 10.8 13.9 (13.1;14.7) 1.13 (1.05;1.21)

Smoking father only 0.00

No 82.3 1.2 (11.0;11.5) 1

Yes 17.7 119.3 (18.6;20.0) 1.89 (1.80;2.00)

Smoking mother only 0.65

No 90.5 12.8 (12.5;13.1) 1

Yes 9.5 11.3 (10.5;12.1) 0.87 (0.80;0.94)

Smoking friends 1.004.52

(4.25;4.82) 0.00

No 38.9 4.6 (4.3;4.8)

Yes 61.1 17.8 (17.4;18.2)

Florianópolis

Sex 0.04

Male 46.6 8.6 (7.9;9.3) 1

Female 53.4 12.2 (11.5;13.1) 1.48 (1.32;1.67)

Smoking parents 0.08

No 88.6 10.1 (9.5;10.7) 1

Yes 11.4 14.9 (13.1;16.8) 1.56 (1.33;1.82)

Smoking father only 0.25

No 83.6 10.2 (9.6;10.8) 1

Yes 16.4 12.9 (11.5;14.4) 1.30 (1.13;1.50) Smoking mother only

No 87.8 10.1 (9.6;10.7) 1

Yes 12.2 14.4 (12.7;16.3) 1.50 (1.28;1.75) 0.10

Smoking friends 0.00

No 45.4 1.9 (1.6;2.3) 1

Yes 54.6 18.0 (17.1;18.9) 11.06 (9.07;13.48)

Porto Alegre

Sex 0.00

Male 44.9 12.9 (12.5;13.6) 1

Female 55.1 21.6 (21.1;22.1) 1.86 (1.78;1.95)

Smoking parents 0.00

No 85.0 15.9 (15.5;16.2) 1

Yes 15.0 27.8 (26.9;28.9) 2.04 (1.93;2.16)

Smoking father only 0.35

No 81.6 17.7 (16.9;17.6) 1

Yes 18.4 19.8 (19.0;20.6) 1.19 (1.12;1.26)

Smoking mother only 0.04

No 85.7 16.7 (16.4;17.1) 1

Yes 14.3 23.3 (22.4;24.3) 1.51 (1.43;1.61)

Smoking friends 0.00

No 32.2 2.1 (1.9;2.4) 1

Table 2. Proportional distribution of school children, smoking prevalence and gross OR and respective 95% confidence intervals, according to exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke and exposure to tobacco-related advertising. Municipalities of Curitiba, Florianópolis and Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil, 2002-2004.

Variable % Smoking prevalence (95% CI) Gross OR (95% CI) p

Curitiba

Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home 0.01

No 59.6 10.6 (10.3;10.9) 1

Yes 40.4 15.7 (15.2;16.1) 1.57 (1.50;1.64)

Exposure to tobacco smoke outside the home 0.00

No 39.7 5.2 (5.0;5.5) 1

Yes 60.3 17.5 (17.2;17.9) 3.86 (3.63;4.09)

Has seen anti-smoking messages 0.29

No 7.9 9.0 (8.3;9.8) 1

Yes 92.1 12.9 (12.6;13.2) 0.67 (0.61;0.74)

Has seen actors smoking 0.08

No 1.7 26.5(23.9;29.1) 1

Yes 98.3 12.3 (12.1;12.6) 0.39 (0.34;0.45)

Has seen advertisements on posters 0.14

No 15.6 9.2 (8.7;9.8) 1

Yes 84.4 13.2 (12.9;13.5) 1.50 (1.40;1.60)

Has seen advertisements on newspapers/

magazines 0.11

No 29.7 13.3 (13.4;14.0) 1

Yes 70.3 10.2 (9.8;10.7) 1.39 (1.32;1.46)

Has some object with a cigarette brand logo 0.00

No 94.4 11.5 (11.2;11.7) 1

Yes 5.6 33.4 (31.9;34.9) 3.87 (3.60;4.15)

Has been offered free cigarettes 0.03

No 92.0 12.0 (11.7;12.2) 1

Yes 8.0 20.2 (19.1;21.3) 1.86 (1.73;2.00)

Florianópolis

Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home 0.00

No 61.6 6.6 (6.0;7.2) 1

Yes 38.4 17.3 (16.3;18.4) 2.98 (2.65;3.35)

Exposure to tobacco smoke outside the home 0.00

No 46.4 6.0 (5.4;6.7) 1

Yes 53.6 14.5 (13.7;15.4) 2.66 (2.34;3.02)

Has seen anti-smoking messages 0.55

No 11.0 9.2 (7.8;10.9) 1

Yes 89.0 10.9 (10.3;11.5) 0.83 (0.63;1.01)

Has seen actors smoking 0.42

No 2.6 6.4 (4.1;9.9) 1

Yes 97.4 10.9 (10.4;11.5) 1.80 (1.14;2.83)

Has seen advertisements on posters 0.01

No 23.6 6.2 (5.4;7.2) 1

Yes 76.4 11.9 (11.3;12.6) 2.04 (1.73;2.40)

Has seen advertisements on newspaper/

magazines 0.70

No 43.3 10.4 (9.6;11.2) 1

Yes 56.7 11.0 (10.3;11.8) 1.07 (0.96;1.20)

Smoking prevalence ratios and respective conidence

intervals in school children aged between 13 and 15 years were 10.7% (95% CI: 10.2;11.3) in Florianópolis, 12.6% (95% CI: 12.4;12.9) in Curitiba and 17.7%(95% CI: 17.4;18.0) in Porto Alegre. By analyzing smoking prevalence according to sex, the proportion of smokers was found to be higher in females, in the three capitals studied (Table 1).

More than half of the students reported having smoking friends. Smoking prevalence was higher among students who had smoking friends, when compared to those who did not (Table 1).

The proportion of school children who reported being exposed to second-hand smoking in the home varied from 48.2% (95% CI: 47.8;48.6), in Porto Alegre, to

38.4% (95% CI: 37.6;39.3), in Florianópolis. As regards exposure to second-hand smoking outside the home, the proportion of school children exposed varied from 62.2% (95% CI: 61.8;62.6), in Porto Alegre, to 53.6% (95% CI: 52.7;54.5), in Florianópolis. In all cities, smoking prevalence in school children exposed to second-hand smoking, both in and outside the home, was higher than that observed in school children who were not exposed (Table 2).

In the three capitals, more than seven out of every ten students interviewed reported having seen cigarette advertisements on posters on the last 30 days (Table 2). As regards the factors associated with smoking in students, a higher probability of being a smoker was observed in female students (OR=1.49), with

Table 2 continuation

Variable % Smoking prevalence (95% CI) Gross OR (95% CI) p

Has some object with a cigarette brand logo 0.00

No 95.1 10.0 (9.4;10.5) 1

Yes 4.9 22.8 (19.6;26.4) 2.66 (2.19;3.25)

Has been offered free cigarettes 0.00

No 93.4 9.6 (9.0;10.1) 1

Yes 6.6 23.0 (20.2;26.1) 2.83 (2.38;3.37)

Porto Alegre

Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home 0.00

No 51.8 10.5 (10.1;10.8) 1

Yes 48.2 25.5 (24.9;26.0) 2.93 (2.79;3.07)

Exposure to tobacco smoke outside the home 0.00

No 37.8 7.5 (7.2;7.9) 1

Yes 62.2 23.8 (23.4;24.3) 3.83 (3.61;4.07)

Has seen anti-smoking messages 0.62

No 8.5 19.4 (18.2;20.6) 1

Yes 91.5 17.4 (17.1;17.8) 1.14 (1.05;1.23)

Has seen actors smoking 0.35

No 4.4 22.5 (20.8;24.3) 1

Yes 95.6 17.5 (17.1;17.8) 0.73 (0.66;0.81)

Has seen advertisements on posters 0.61

No 12.0 19.2 (18.2;20.2) 1

Yes 88.0 17.5 (17.2;17.9) 0.89 (0.84;0.96)

Has seen advertisements on newspapers/

magazines 0.47

No 28.1 16.4 (15.8;17.0) 1

Yes 71.9 18.2 (17.8;18.6) 1.13 (1.07;1.19)

Has some object with a cigarette brand logo 0.00

No 91.1 15.5 (15.2;15.8) 1

Yes 8.9 40.8 (39.4;42.3) 3.77 (3.53;4.02)

Has been offered free cigarettes 0.00

No 90.6 16.3 (16.0;16.7) 1

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with smoking in school children. Municipalities of Curitiba, Florianópolis and Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil, 2002; 2004.

Variable Adjusted OR (95% CI) p

Curitiba

Sex 0.06

Male 1

Female 1.49 (0.89;2.00)

Smoking father only 0.04

No 1

Yes 1.59 (1.02;2.41)

Smoking friends 0.00

No 1

Yes 3.46 (2.11;5.79)

Exposure to tobacco smoke outside the home 0.00

No 1

Yes 3.26 (1.71;4.44)

Has some object with a cigarette brand logo 0.00

No 1

Yes 3.29 (1.81;5.80)

Florianópolis

Sex 0.25

Male 1

Female 1.26 (0.84;1.89)

Smoking friends 0.00

No 1

Yes 9.31 (4.77;18.15)

Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home 0.00

No 1

Yes 2.03 (1.34;3.06)

Exposure to tobacco smoke outside the home 0.10

No 1

Yes 1.45 (0.93;2.28)

Has seen advertisements on posters 0.04

No 1

Yes 1.82 (1.04;3.16)

Porto Alegre

Sex 0.00

Male 1

Female 1.57 (1.11;2.19)

Age (years) 0.00

13 1

14 1.77 (1.06;2.82)

15 2.89 (1.77;4.58)

Smoking friends 0.00

No 1

Yes 9.12 (4.48;18.74)

a smoking father (OR=1.59), with smoking friends (OR=3.46), exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke (OR=3.26) and having some object with a cigarette brand logo (OR=3.29). In Florianópolis, variables

signi-icantly associated with smoking were: being female

(OR=1.26), having smoking friends (OR=9.31), being exposed to second-hand tobacco smoking in (OR=2.03) and outside the home (OR=1.45), and having seen advertisement on posters (OR=1.82). In Porto Alegre, variables associated with tobacco use among students were: being female (OR=1.57), being aged 14 years (OR=1.77) and 15 years (OR=2.89), having smoking friends (OR=9.12), being exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke in (OR=1.87) and outside the home (OR=1.77) and having some object with a cigarette brand logo (OR=2.83) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The presence of a high smoking prevalence among school children in Southern Brazil, especially in the

city of Porto Alegre, had already been identiied in

other studies.3

The smoking survey applied to students in 2000 and 2007, in 151 locations (140 WHO member countries and 11 territories/regions), showed that 9.5% of them were smokers.14 By comparing WHO regions, the highest

prevalence was observed in Europe (19.2%), followed by the Americas (14.3%). In the latter, it is in the southern part of South America (Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Southern Brazil) where the highest smoking rates are found, with the greatest proportion of smoking students in the city of Santiago, Chile (33.9%).14

In the present study, the smoking prevalence among

females was signiicantly higher than that among males.

The current increase in the proportion of smokers among

women relects, in part, the tobacco industry strategy

to create advertisements aimed at satisfying women’s wishes, in their different life stages.13 Thus, the brands

geared to young women emphasize companionship,

self-conidence, freedom and independence.1

In the three capitals studied, more than half of school children reported having a smoking friend, and such characteristic is among the main risk factors for smoking in this age group.5,9,10,12 In a systematic

review on smoking prevalence and risk factors among adolescents in South America, the smoking habit among siblings and friends were the main risk factors.10

There was a high frequency of secondhand smoke exposure among youth in the three capitals of Southern Brazil, even though this country has extensive legis-lation aimed at protecting people against exposure to secondhand smoke. The main federal laws in effect in Brazil are: Law n. 9,294,a from July 15th, 1996,

and Decree n. 2,018, from October 1st, 1996, which

regulates Law n. 9,294/96 and deines the concepts

of common indoor areas and exclusive, designated smoking areas. In addition, there is Law n. 10,167, from December 27th, 2000, which changes Law n.

9,294/96 and prohibits the use of tobacco-derived smoking products in aircrafts and other public transport vehicles, and Inter-Ministerial Decree n. 1,498, from August 22nd, 2002, which recommends that health and

educational institutions implement programs on passive smoking-free environments.7

Scientiic evidence indicates there is no safe level of

exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and that the adoption of smoke-free environments is the only effective way to protect the population from the harmful effects of exposure to secondhand smoke. Ventilation and designated smoking areas, equipped with an inde-pendent ventilation system, do not reduce exposure to

Tabela 3 continuation

Variable Adjusted OR (95% CI) p

Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home 0.00

No 1

Yes 1.87 (1.33;2.69)

Exposure to tobacco smoke outside the home 0.01

No 1

Yes 1.77 (1.16;2.72)

Has some object with a cigarette brand logo 0.00

No 1

Yes 2.83 (1.83;4.64)

safe levels and are not recommended. Thus, the WHO encourages member countries to create, implement and enforce laws that require that all indoor public and working environments be completely smoking-free, consequently promoting universal protection.15,17 In

addition, it encourages educational strategies to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke at home.16

Adolescents living in the capitals of the Southern states of Brazil were highly exposed to tobacco advertising, given the great proportion of teenagers who reported having seen cigarette advertisements on posters, newspapers or magazines, despite Federal Law n. 10,167, from December 28th, 2000, prohibiting the

advertising of tobacco-derived products in magazines, newspapers, television, radio and billboards. The law prohibits advertising through electronic means or that which is hired and indirect, publicity in stadiums, ballrooms, stages or similar locations, and sponsor-ship of international sporting and cultural events by tobacco companies.7 Results similar to those found in

Southern Brazil, showing a high number of adolescents who reported having seen cigarette advertisements on the last 30 days, were also observed in other capitals of the country.3 One possible explanation would be

that adolescents who reported having seen cigarette advertisements or promotions on posters, newspapers or magazines are remembering advertising at points of sale, which is not prohibited by federal law. This situation serves as a warning to authorities about the need to extend advertising prohibition to points of sale. Considering the fact that the three surveys analyzed in this study were made in 2002 and 2004, close to the implementation of Federal Law n. 10,167 (2000), the impact of this law will be better assessed when surveys are repeated in these cities.

Complete advertising restriction of tobacco products is a measure included in smoking control and preven-tion programs2,11 and among the six political measures

recommended by the WHO to revert the worldwide tobacco epidemic.15-17

Results from the Vigescola are subject to certain limitations. The cross-sectional design of this study, in which outcome and risk factors are observed at the same moment, may include reversed causality bias. In addition, the sample is representative of school children aged between 13 and 15 years present in the classrooms, on the day the questionnaire was applied, and who accepted to participate in the research. Yet another restriction was the fact that Vigescola results were based on data provided by students, without vali-dation, and where actual tobacco consumption could have been over- or underestimated. Another important factor to be considered is that the questionnaire was applied in a school environment, a situation that may have increased the possibility of a student omitting their smoking status; however, the questionnaire characteristics (self-reported and anonymous) may have contributed to reduce such omission. Moreover, in Curitiba and Florianópolis, the survey was restricted to day school classes; thus, students enrolled in grades 7 and 8 of primary education and grade 1 of secondary education in night schools may not have been adequa-tely represented.

In conclusion, smoking prevalence in school children living in the capitals of Southern Brazil is high and

the factors signiicantly associated with smoking are:

1. Anderson SJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Emotions for sale: cigarette advertising and women’s psychosocial needs.

Tob Control. 2005;14(2):127-35. DOI: 10.1136/

tc.2004.009076

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs - 2007. Atlanta; 2007.

3. De Almeida LM, Cavalcante TM, Casado L, Fernandes EM, Warren CW, Peruga A, et al. Linking Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC): the case for Brazil. Prev Med. 2008;47(Supl I):S4-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.017

4. Global Tobacco Surveillance System Collaborating Group. Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS): purpose, production, and potential. J Sch Health.

2005;75(1):15-24. DOI: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005. tb00004.

5. Hoffman B, Sussman S, Unger J, Valente TW. Peer Influences on adolescent cigarette smoking: a theoretical review of the literature.

Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(1):103-55. DOI:

10.1080/10826080500368892

6. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Johw Wiley & Sons; 1989.

7. Iglesias R, Jha P, Pinto M, Costa e Silva VL, Godinho J. Controle do tabagismo no Brasil. Washington: World Bank; 2007.

8. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE, Nizam A. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. 3.ed. Pacific Grove: Duxbury Press; 1988.

9. Malcon MC, Menezes AMB, Chatkin M. Prevalência e fatores de risco para tabagismo em adolescentes. Rev

Saude Publica. 2003;37(1):1-7. DOI:

10.1590/S0034-89102003000100003

10. Malcon MC, Menezes AMB, Mata MFS, Chatkin M, Victora CG. Prevalência e fatores de risco para tabagismo em adolescentes na América do Sul: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Rev Panam Salud

Publica. 2003;13(4):222-8. DOI:

10.1590/S1020-49892003000300004

11. National Cancer Policy Board. State programs can reduce tobacco use. Washington; 2000.

12. United States. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among young people. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta; 1994.

13. Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S, Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group. Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):749-53. DOI: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(06)68192-0

14. Warren CW, Jones NR, Peruga A, Chauvin J, Baptiste JP, Costa de Silva VL, et al. Global Youth Tobacco Surveillance: 2000 to 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(1):1-28.

15. World Health Organization. Framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva; 2003.

16. World Health Organization. Protection from exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke. Policy recommendations. Geneva; 2007.

17. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER packaged. Geneva; 2008.

REFERENCES