AR

TICLE

1 Núcleo de Informação, Políticas Públicas e Inclusão Social (NIPPIS), LIS/ICICT/ FIOCRUZ/FMP/FASE. R. Barão do Rio Branco 1003, Centro. 25680-120 Petrópolis RJ Brasil. crisrabelais@gmail.com. 2 Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social no Rio de Janeiro. Petrópolis RJ Brasil.

Social protection and public policy for vulnerable populations:

an assessment of the Continuous Cash Benefit Program

of Welfare in Brazil

Abstract This paper describes the historical de-velopment and profile of Continuous Cash Benefit (BPC) applicants, intended for poor elderly and people with disabilities, which, since 2009, uses el-igibility criteria based on the International Clas-sification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) of the WHO and is aligned with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Dis-abilities. The behavior of benefits was determined from the analysis the coefficients of the general and non-judicial grants between 1998 and 2014. The profile was established for the years 2010 and 2014 according to situation of acceptance, age, gender and ICF components. The average annual growth of the coefficient was higher from 2000 to 2010, prior to the adoption of the biopsy-chosocial eligibility model, and the coefficient of non-judicial grants increased until 2010, falling thereafter. The deferrals acceptance /rejections ra-tio was higher among children and among those facing severe or total environmental barriers, limitations, constraints and bodily changes. The implementation of the biopsychosocial evaluation model did not cause an increased rate of grants and results evidence the need for flexibility in the eligibility criteria.

Key words International Classification of Func-tioning, Functioning Disability and Health, Dis-ability evaluation, Social protection, Social vul-nerability

Cristina Maria Rabelais Duarte 1

Miguel Abud Marcelino 1,2

Cristiano Siqueira Boccolini 1

Patrícia de Moraes Mello Boccolini 1

D

uar

te CMR

Introduction

This paper aims to describe the historical devel-opment and the profile of Continuos Cash Bene-fit (BPC) applicants, which integrates the Brazil-ian social protection policy.

The establishment of social protection sys-tems ssys-tems from a public action aimed at pro-tecting society from the effects of the classic risks that produce dependence and insecurity: illness, old age, disability, unemployment and exclusion. The role of social protection systems in economic development, also a stability factor for countries

with improved systems1, has also been

recog-nized.

In Brazil, BPC is a constitutional right set forth in Article 203, which provides for “the as-surance of a minimum monthly benefit wage to the disabled person and the elderly who can pro-vide proof of their own inability to cater for their own survival or have this need met by their own family”. It is a benefit intended for a segment in a situation of dependence and social insecurity.

In the current institutional design, the BPC integrates the Basic Social Protection of the Uni-fied Welfare System (SUAS), coordinated by the Ministry of Social Development (MDS) and geared to the population in situation of social vulnerability, understood as arising from poverty,

deprivation and/or weak affective relationships2.

Eligibility for the BPC implies the evaluation according to income criteria and defining char-acteristics of the target populations: advanced age or disability, which have been considered quite restrictive in their cutoff points and re-viewed over the years in the benefit regulations, following changes in policies and regulations

aimed at this target audience3. However, these

changes refer only to age and the characteriza-tion of disability, since the income limit remains the same since the establishment of the benefit – monthly per capita family income less than ¼ of minimum wage.

The minimum age required for the elderly, initially set at 70 years, changed to 67 in 1998 and 65 in 2004. The characterization of disability is much more complex and controversial, especially in light of advances in the conceptualization and assurance of social rights to people with disabil-ities.

Regarding the design, the proposal of a new paradigm to address disability was carried out at the international level, initially with the WHO’s dissemination of the International Classification

of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)4,

published in Brazil in 2003, and embodied in the enactment of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006 in New York, approved and enacted in Brazil with the status of

Constitutional Amendment5 with Legislative

De-cree 186/2008 and DeDe-cree 6.949/20096.

In the context of BPC, the international in-fluence has materialized in the review of the

dis-ability assessment model to access the benefit7.

Until 1997, the grant built on the evaluation and report issued by a SUS or INSS service manned by a multi-professional team. As of August 1997, the evaluation became the sole responsibility of INSS Medical Expertise. Access to the benefit re-quired meeting the criteria of per capita house-hold income and characterization of disability, understood as incapacity to work and live inde-pendently. The criteria for granting and review-ing BPC remained effectively guided by the

bio-medical conception until 20093,8,9.

The new paradigm was set by Decree No. 6.214/2007, establishing new eligibility criteria.

The Joint MDS/INSS Ordinance Nº 1/200910 set

forth the tools and criteria for the biopsychoso-cial assessment of disability to access PCB, built on the biopsychosocial model of the ICF and in line with the UN Convention. Then, evaluation was carried out by Social Workers and Medical Experts of the INSS. The second version of the disability assessment tools was implemented in

201111 and the third version in 201512.

There is a profound change in the disability concept represented by the biopsychosocial mod-el proposed by the ICF and the UN Convention and its incorporation into the benefit eligibility model was an unprecedented advance in the his-tory of social protection and public policy aimed at people with disabilities in a social vulnerability situation in the country.

However, discrimination, invisibility and

in-equality still persist6,13. Take, for example,

differ-ences in the situation of poverty and social ex-clusion that mark persons with some type of

dis-ability identified in the 2010 census14 in relation

to the general population. Among those over 15 years of age, 61% had no schooling or complete elementary education. The more serious the deficiencies, the more important the exclusion. Among people with total or severe disabilities over 10 years of occupation, 14% had no income and 42% earned up to one minimum wage, while for non-disabled persons, these figures were 6% and 31%, respectively.

impor-e C

ole

tiv

a,

22(11):3515-3526,

2017

tance of non-contributory welfare benefits such as BPC, associated with social inclusion policies. Despite the relevance of the benefit as a Brazilian basic protection component, the eligibility cri-teria have been repeatedly questioned, since the adoption of such a narrow income limit hinders access by a significant portion of the population

in a situation of poverty3.

The growing phenomenon of the benefit’s

grant judicialization3,15-17 has evidenced the need

to revise the criteria for the characterization of dependency and vulnerability, especially consid-ering the impacts of aging and disability on the household budget. These expenditures, called “catastrophic expenditures” in the literature in-crease or deepen the risk of poverty for the whole

family group3. In 2015, 30% of benefits were

granted in court, according to data reported by

the National Welfare Office (MDS)18.

In fact, two movements were decisive for the levels of access to BPC since its inception: the trend of age and disability criteria regulation and action of the judiciary, identifying protective gaps in the poor assurance of access to BPC for

the elderly and people with disabilities3.

Taking into account the adoption of the bio-psychosocial eligibility model as of 2009, the re-sults of this paper discussed in light of the liter-ature produced on the topic are shown in three sections. In the first, the disabled person evalu-ation model for the access to the BPC is exam-ined; in the second, we sought to identify possi-ble changes in the pace of granting new benefits, evaluating the trend between 1998 and 2014; and, in the final part, the profile of disabled per-sons applying for BPC in the validity of the new evaluation model is described.

Methods

This is a descriptive, observational study based on secondary data. Considering that the evalu-ation for the granting of BPC became the exclu-sive responsibility of the INSS in August 1997, the behavior of benefits was determined for the period from 1998 to 2014, based on the analysis of the coefficient of benefits granted to persons with disabilities (PwD) in the population aged 0-64 years (per 10,000 inhabitants), correspond-ing to the entry of new benefits into the social security system (http://www1.previdencia.gov. br/aeps2006/15_01_01_02_01.asp).

In the numerator of the coefficient, the num-ber of benefits granted to people with disabilities

provided by DATAPREV in the Social Security Historical Database, known as the “People with

Disability Support” was used19. The population

from zero to 64 years, estimated by the IBGE Foundation (http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/ deftohtm.exe?ibge/cnv/poptbr.def) was consid-ered as denominator. Using the same formula and excluding from the numerator the judicially

granted benefits20, the coefficient of non-judicial

grants for the period from 2004 to 2014 was also calculated. The population older than 65 years was disregarded since it was eligible for BPC for the elderly, and the number of grants to people with disabilities in this age group was nonexis-tent or residual.

Initially, a descriptive analysis of the behavior of the grant coefficients was performed during the study period. The trend analysis was then performed through the Join Point Regression free access program of the National Cancer

Insti-tute21, version 4.4.0.0, dated January 4, 2017.

The joinpoint analysis was developed accord-ing to the segmented linear regression method, with estimated inflection points, in order to de-termine whether these and the estimated trends are statistically significant. The joinpoint analysis identifies the timing of trend changes (inflec-tion points) and calculates the Annual Percent-age Change (APC) in each trend segment, with a 95% confidence interval (CI). APC values can range from minus to plus infinity (negative num-bers reflecting a decreasing trend, and positive, an increasing trend), with zero being equivalent to lack of trend.

The deferral profile was analyzed during the validity of the new model for the evaluation of the disabled person for 2010 and 2014, entirely under the validity of a single version of the eval-uation tool, considering the ratio of deferrals according to age, ICF components and gender, the latter being analyzed only for 2014 due to the large proportion of ignored records in 2010.

The ICF components – Environmental Fac-tors barriers, Bodily Functions change and lim-ited and restricted Activities and Participation – were considered according to the results of social and medical evaluation, expressed through qual-ifiers ranging from none to total, according to the measurement proposed by the classification.

The deferral ratio was calculated by dividing the number of benefits granted by the number of denied benefits and multiplying the result by 100.

Information on the deferrals profile was ob-tained on a structured basis within the research

re-D

uar

te CMR

duced functionality - People with Disabilities and the Elderly”, based on data provided by the MDS. In this case, only the benefits with full medical and social assessment were included in the analy-sis. Some differences are observed in the number of registrations of benefits granted (in the His-torical Database of Social Security) and deferred (on the basis structured by said research proj-ect). They are probably due to differences in the update of existing databases in the two sources. From 2010 to 2014, the lowest difference (0.8%) was observed in 2010 and the highest (4.9%) in 2012.

A Brazilian Ethics in Research Committee ap-proved the study.

The biopsychosocial disability assessment model for access to BPC

In terms of its regulation, the BPC was imple-mented by the Welfare Organic Law (LOAS), Law Nº 8.742, of December 7, 1993, with significant amendments made by Laws Nº 12.435, dated July 6, 2011 and Nº 12.470, dated August 31, 2011. Regulation was enacted by Decree Nº 6.214/2007 and subsequent amendments, and the most re-cent is Decree Nº 8.805, dated July 2016.

The biopsychosocial evaluation model for el-igibility to BPC came into force in August 2009 as a result of the work of a multi-professional and multi-sectoral group, established to align the eli-gibility criteria adopted at the time to the concept of disability proposed by international

frame-works22. It was developed based on the ICF and

in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The biopsychosocial model submitted by the ICF/WHO transcends bodily changes, focusing on the interaction between the various realms of

health (biological, individual and social)4,23.

Dif-ferent grades of functionality and disability stem from the interaction between a health condition (disease, trauma and injury) and context factors (environmental and personal factors). Total dis-ability and functionality are two extremes of a continuum, in which individuals are positioned dynamically – which changes due to age, or to specific events that occur throughout life, pro-ducing permanent or temporary situations, ac-cording to the concrete result of the interaction between their physical and psychological condi-tions and their surrounding environment.

According to the biopsychosocial perspective, disability is born from specific social contexts and is defined by the barriers faced by individuals

in performing basic or more complex daily tasks required for independent living. It is important to emphasize that this is an approach applicable to a wide range of acute and chronic health situ-ations and conditions, in interaction with the en-vironment, not restricted to structural losses or functions traditionally considered as disabilities.

The UN Convention, which is the result of the participation of governments, civil insti-tutions and people with disabilities around the world, recognizes that disability is an evolving concept and conceptualizes “people with disabil-ities”, formalizing the term. In the Brazilian Por-tuguese version, people with disabilities include those with “physical, mental, intellectual or long-term sensory impairments, which in interaction with the various barriers obstruct their full and effective participation in society, in equal

condi-tions with other people”24.

In Brazil, the concept established by the Con-vention is explicitly adopted in the BPC regula-tory framework and, since 2009, the benefits el-igibility evaluation model includes two steps: 1) assessment of household income declared, from registration, by technician or social security an-alyst, in a specific registration system; 2) assess-ment of disability performed by social worker and medical expert.

The disability assessment is based on the Medical-Expert and Social Disability Assessment Tool for Access to BPC, organized into compo-nents, domains and classification units selected from the ICF, in two modalities: for people under 16 years and those aged 16 years and over. Expert Doctors evaluate 18 domains, related to changes in the bodily functions and medical aspects-re-lated limitations and restrictions. Social workers evaluate nine domains related to environmental barriers and limitations and restrictions related to the social context.

The result of the evaluation produces a final qualifier for each of the three tool components, quantifying the intensity of environmental bar-riers, the limitations and restrictions on activities and participation and changes in bodily func-tions/structures, in five levels: none, light, mod-erate, severe or total.

e C

ole

tiv

a,

22(11):3515-3526,

2017

The remaining combinations, with the respective deferral results are systematized in Chart 1.

Considering the above, it is worth emphasiz-ing two aspects regardemphasiz-ing the current disability assessment model for access to BPC: 1) only ap-plicants with bodily changes and moderate or severe long-term limitations and restrictions are eligible for benefit; 2) despite the introduction of social assessment in the model, the result of the medical-expert evaluation has greater weight in the final result.

Model controversies point to the prepon-derance of medical evaluation and to the grant restriction due to long-term impediments.

Sil-va and Diniz9 draw the attention to the current

LOAS wording that excluded the requirement of lack of capacity for independent living and work that existed in the original wording of the device, aligning it with the contemporary language of the Convention, but reversed the positive meaning of change by qualifying the long-term impediment with the requirement to produce effects for two years. They rightly argue that the text of the Con-vention and therefore of the Federal Constitution does not reduce fundamental rights to the dura-tion of bodily impediments.

In fact, socially vulnerable individuals who, because of a temporary change in their health

status cannot cater for their basic needs25, may be

qualified with temporary impairments, it should be noted, in the expanded ICF conception. Once they are not covered by (contributory) social in-surance, they are not covered by the BPC and re-main without social protection.

Expanded access to this segment can be achieved by replacing the two-year fixation by an

evaluation of the duration of the impediment by medical experts and social workers, based on the individual needs of applicants, with reassessment forecast according to the deadline stipulated in each case, or automatic cessation of the benefit in situations with foreseeable terms.

It is worth noting that, as underlined by the World Disability Report, in addition to tempo-rary welfare benefits, greater flexibility in pay-ments and options to keep benefits on hold while people enter the labor market can have positive effects on the employability of people with dis-abilities by making them, at the same time, feel encouraged to work and safe because they know

that they can still use the benefit26 if they do not

succeed.

The biopsychosocial model and the granting of benefits: the 1998-2014 trend

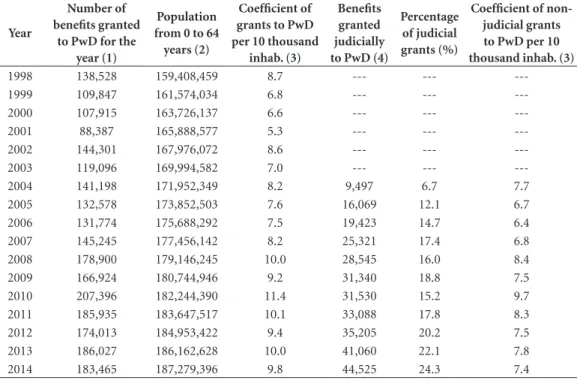

The grant coefficient ranged from 8.7 to 11.4 in the period 1998-2010. From 2010 to 2014, the coefficient declined to 9.8 in 2014 after a small increase in 2013 (Table 1).

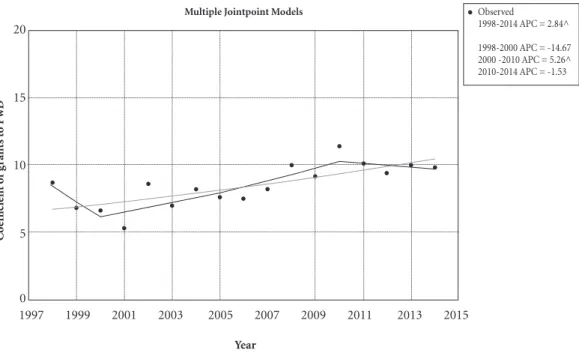

The new disability evaluation model came into effect in the second half of 2009. The join-point method (Figure 1) analysis revealed a sig-nificant increased trend of the grant coefficient from 1998 to 2004, at a yearly rate of 2.84%. An alternative model, which takes the years of 2000 and 2010 as inflection points, revealed that, when the medical disability assessment model was in place under the exclusive responsibility of INSS medical experts, a non-significant yearly decline of 14.67 % was reported in the first two years of the series – which may have been due to the

elim-Chart 1. Matrix of combinations between the results of social and medical-expert evaluation of disabled person, according to biopsychosocial model of assessment to the BPC.

Changes in body functions / structures *

Limited activities and restricted participation

None Light Moderate Severe Total

None No No No No No

Light No No No No No

Moderate No No No Yes Yes

Yes

(only if environmental hurdles are severe or total)

Severe No No Yes Yes Yes

Total No No Yes Yes Yes

NOTE: The Yes or No categories correspond to the condition of deferral in relation to the combination of the final qualifiers, in compliance with the requirements set forth in article 20 of Law 8.742/93, which defines a person with a disability.

* Terminology introduced from the 3rd version of the tools in 2015 (used here for the correct understanding of what is effectively evaluated in the component).

D

uar

te CMR

ination of the grant based on a report issued by a SUS service – followed by a significant yearly increase of 5.26% up to 2010. The upward trend seems to have reversed in the last four years of the series, after, therefore, the adoption of the new model, since the coefficient showed a slight (not significant) yearly decline of 1.53% compared to the maximum peak of 2010, but remained stable at levels similar to 2008, the last year of the exclu-sively medical evaluation.

Judicially granted benefits (Table 1) increased steadily between 2004 and 2014, when the pro-portion of court grants exceeded 24%. The trend towards policy judicialization has a strong im-pact on the grant levels, which is evident from the coefficient of non-judicial grants, which showed inverse but not significant trends before and af-ter 2010: annual increase of 4.21% from 2004 to 2010 and annual decrease of 3.58% from 2010 to 2014, a relatively greater decrease than that shown by the general grants (Figure 2).

The results indicate that the benefits granting rate did not increase with the incorporation of social eligibility criteria. On the contrary, the im-plementation of the new model was followed by stabilization and slight decline in the coefficient

of beneficiaries. However, a few more years of observation of the series are required to confirm whether 2010 was a significant turning point in the granting of benefits or not.

No studies were found on the effects of the new evaluation model on BPC grants for

peo-ple with disabilities. However, Santos27 draws the

attention to the milestone of adopting a biopsy-chosocial perspective in the assessment of BPC, one of the first policies to adopt in its entirety the concept of disabled persons in the 2006 Con-vention.

On the other hand, one of the objectives of BPC is to address poverty in the segment

served28-30 and, for some years, studies have been

pointing to its effects on inequality. Soares et

al.30 evaluated the 2004 PNAD and concluded

that the benefit is high enough to remove a sig-nificant number of families from poverty.

Vian-na and Teixeira29, on the other hand, in a study

on the role of non-contributory benefits in the fight against poverty in 2005 argues that, while the number of benefits grew annually, they still fell short of what seemed necessary to cope with poverty. The problem would therefore lie in the coverage achieved by the policy.

Table 1. Development of the coefficient of total and non-judicial (per 10.000 inhabitants) of the Continued Cash Benefit Programme of Social Assistance (BPC) in Brazil, from 1998 to 2014.

Year

Number of benefits granted

to PwD for the year (1)

Population from 0 to 64

years (2)

Coefficient of grants to PwD per 10 thousand

inhab. (3)

Benefits granted judicially to PwD (4)

Percentage of judicial grants (%)

Coefficient of non-judicial grants to PwD per 10 thousand inhab. (3)

1998 138,528 159,408,459 8.7 --- ---

---1999 109,847 161,574,034 6.8 --- ---

---2000 107,915 163,726,137 6.6 --- ---

---2001 88,387 165,888,577 5.3 --- ---

---2002 144,301 167,976,072 8.6 --- ---

---2003 119,096 169,994,582 7.0 --- ---

---2004 141,198 171,952,349 8.2 9,497 6.7 7.7

2005 132,578 173,852,503 7.6 16,069 12.1 6.7

2006 131,774 175,688,292 7.5 19,423 14.7 6.4

2007 145,245 177,456,142 8.2 25,321 17.4 6.8

2008 178,900 179,146,245 10.0 28,545 16.0 8.4

2009 166,924 180,744,946 9.2 31,340 18.8 7.5

2010 207,396 182,244,390 11.4 31,530 15.2 9.7

2011 185,935 183,647,517 10.1 33,088 17.8 8.3

2012 174,013 184,953,422 9.4 35,205 20.2 7.5

2013 186,027 186,162,628 10.0 41,060 22.1 7.8

2014 183,465 187,279,396 9.8 44,525 24.3 7.4

e C

ole

tiv

a,

22(11):3515-3526,

2017

Figure 1. Coefficient of grants per 10,000 inhabitants observed and expected through the join point method and annual rate of change, by time segment. Brazil, 1998 to 2014.

^ Indicates annual percentage change (APC) other than zero (α = 0.05).

Source: Own elaboration based on data collected in the Historical Database of Social Security (available at: http://www3.dataprev. gov.br/infologo/) and IBGE – Population Estimates (available at: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf. def).

C

o

efficie

nt o

f g

rants t

o PwD

Multiple Jointpoint Models

Year

Figure 2. Coefficient of non-judicial grants per 10,000 inhabitants observed and expected through the join point method and annual rate of change, by time segment. Brazil, 1998 to 2014.

^ Indicates annual percentage change (APC) other than zero (α = 0.05).

Source: Own elaboration based on data collected in the 2015 BPC Bulletin published by the Ministry of Social Development (available at: http://www.mds.gov.br) and IBGE – Population Estimates (available at: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm. exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf.def).

C

o

efficie

nt o

f no

n-j

udicial g

rants t

o PwD

Multiple Jointpoint Models

Year

2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015

9.6 10 10.4

9.2

8 8.4 8.8

7.6

6.4 6.8 7.2

6

2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014

Observed 2004-2010 APC = 4.21 2010-2014 APC = -3.58

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015

0 5 10 15 20

Observed

1998-2014 APC = 2.84^

D

uar

te CMR

Although results of this study show annu-al growth of the benefit coefficient, they still do not authorize a review of author’s observations. Despite the developing design of the disability concept and the eligibility criteria, BPC may not be able to reach sufficient coverage of the target population. However, the lack of population data on the number of people with disabilities be-longing to families with a household per capita income lower than ¼ minimum wage – the target population of the program – makes a conclusive evaluation impossible. Notwithstanding, the im-pact of the BPC is far from negligible. In 2015, 4.2 million Brazilians received from the public coffers a monthly minimum wage, representing a

total of R$ 39.6 billion injected into the market20,

which have effectively contributed to a reduced

inequality over the years28,29,31.

The expanded judicial grants corroborate the assessment that the BPC has not fulfilled its role in basic social protection, excluding signifi-cant portions of the population in a situation of

poverty from basic social rights. Silveira et al.3

argue that the progressive judicialization impos-es a normative deliberation on the easing of the benefits granting conditions, because it further expands the inequity gap in the access to rights, since its implementation depends on the appli-cants’ access to justice and the individual under-standing of each judge or court on the specific situations of the applicants.

Authors point out that the decision handed down in 2013 by the Federal Supreme Court, re-garding the insufficient income criterion to gauge the vulnerability of BPC applicants is still await-ing decision. Despite raisawait-ing a discussion about new criteria among benefit managing agencies, based on concepts of dependency and autonomy and considering a wider range of socioeconomic vulnerabilities, the most recent legal tool – De-cree Nº 8.805/2016 – did not accept the access flexibility rule for claimants with income higher than ¼ of the minimum wage, which keeps legal uncertainty for these cases.

The pattern of BPC deferral in the validity of the medical-social evaluation model

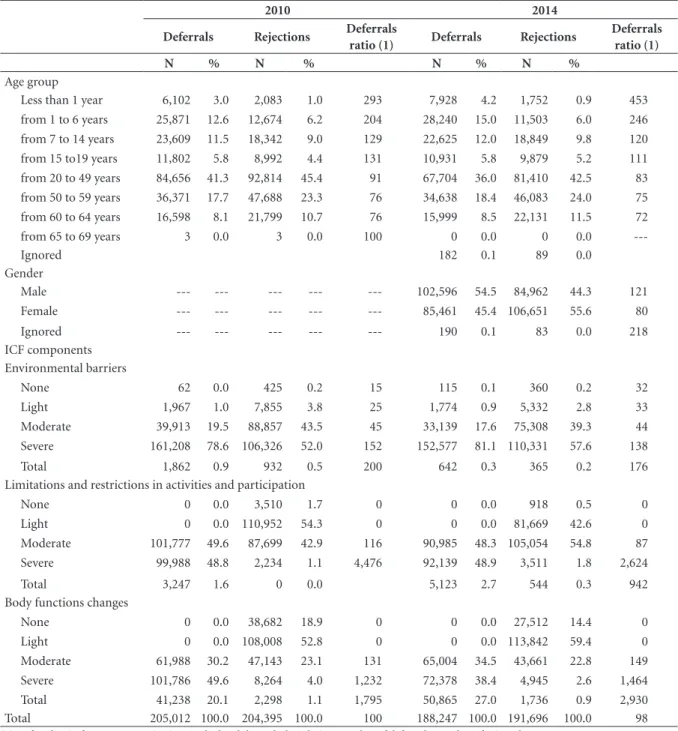

The general pattern of deferrals (Table 2) re-veals a higher proportion among men – ratio of deferrals is 1.5 times higher than among wom-en – and among the youngest people, especially those under 1 year of age.

It is important to highlight the change in the pattern observed in children under 1 year: the

de-ferral ratio increased 1.5 times in 2014 compared to 2010. While the possibility of this significant increase is due to modifications in the second version of the form, which increased the odds of deferrals, these findings indicate the need for fur-ther study, especially considering possible

sequel-ae due to the Zika virus3, before the change of the

microcephaly pattern in Brazil was characterized by the Ministry of Health, which occurred from

201532.

The analysis of the profile of BPC applicant, considering ICF components, contributes to unraveling how the broader social and cultural dynamics, in connection with individual aspects, define a situation of vulnerability in the field of health, in an approach that seeks to overcome risk-anchored practices and capture interfer-ence between the multiple realms involved in the

health-disease process33. In addition, it reveals

difficulties faced by both those whose benefit has been deferred and those with rejected ones, and it is fundamental, in the case of the latter, to guide policies directed at a segment not covered by the BPC.

The main defining factors of deferral are the limited and restricted activities and participation and bodily functions changes. Among those de-ferred, severe or total classifications prevail, and in the case of dismissals, limitations and restric-tions are of lower intensity and bodily changes are light or moderate. Ninety to one hundred percent of applicants with serious or total im-pairments had their benefit granted. In 2014, the deferral ratio decreased for those with more severe limitations and restrictions. On the other hand, the deferral ratio increased for individuals with greater bodily functions changes.

A large proportion of evaluated people faces significant environmental barriers. While there are differences in the profile of the deferred and rejected, this is the component in which discrep-ancies are smaller: if moderate barriers are taken into account, almost all applicants experienced moderate or severe environmental barriers in the two years of the series – about 99% of those de-ferred and 96 to 97% of those rejected.

net-e C

ole

tiv

a,

22(11):3515-3526,

2017

works and relationships, attitudinal barriers and difficulties in accessing services and policies. The more important the barriers, the greater the de-pendency and vulnerability, pushed to the limit by poverty.

The association between poverty, disability and social exclusion is recognized in

internation-al literature34. In Brazil, the National Health

Sur-vey, whose data were collected in 2013, provides some important clues about the vulnerability to

Table 2. Proportionate distribution of the requirements of the Continued Cash Benefit Programme of Welfare (BPC), by age range, status and deferral ratio - Brazil, 2010 and 2014.

2010 2014

Deferrals Rejections Deferrals

ratio (1) Deferrals Rejections

Deferrals ratio (1)

N % N % N % N %

Age group

Less than 1 year 6,102 3.0 2,083 1.0 293 7,928 4.2 1,752 0.9 453

from 1 to 6 years 25,871 12.6 12,674 6.2 204 28,240 15.0 11,503 6.0 246

from 7 to 14 years 23,609 11.5 18,342 9.0 129 22,625 12.0 18,849 9.8 120

from 15 to19 years 11,802 5.8 8,992 4.4 131 10,931 5.8 9,879 5.2 111

from 20 to 49 years 84,656 41.3 92,814 45.4 91 67,704 36.0 81,410 42.5 83

from 50 to 59 years 36,371 17.7 47,688 23.3 76 34,638 18.4 46,083 24.0 75

from 60 to 64 years 16,598 8.1 21,799 10.7 76 15,999 8.5 22,131 11.5 72

from 65 to 69 years 3 0.0 3 0.0 100 0 0.0 0 0.0

---Ignored 182 0.1 89 0.0

Gender

Male --- --- --- --- --- 102,596 54.5 84,962 44.3 121

Female --- --- --- --- --- 85,461 45.4 106,651 55.6 80

Ignored --- --- --- --- --- 190 0.1 83 0.0 218

ICF components Environmental barriers

None 62 0.0 425 0.2 15 115 0.1 360 0.2 32

Light 1,967 1.0 7,855 3.8 25 1,774 0.9 5,332 2.8 33

Moderate 39,913 19.5 88,857 43.5 45 33,139 17.6 75,308 39.3 44

Severe 161,208 78.6 106,326 52.0 152 152,577 81.1 110,331 57.6 138

Total 1,862 0.9 932 0.5 200 642 0.3 365 0.2 176

Limitations and restrictions in activities and participation

None 0 0.0 3,510 1.7 0 0 0.0 918 0.5 0

Light 0 0.0 110,952 54.3 0 0 0.0 81,669 42.6 0

Moderate 101,777 49.6 87,699 42.9 116 90,985 48.3 105,054 54.8 87

Severe 99,988 48.8 2,234 1.1 4,476 92,139 48.9 3,511 1.8 2,624

Total 3,247 1.6 0 0.0 5,123 2.7 544 0.3 942

Body functions changes

None 0 0.0 38,682 18.9 0 0 0.0 27,512 14.4 0

Light 0 0.0 108,008 52.8 0 0 0.0 113,842 59.4 0

Moderate 61,988 30.2 47,143 23.1 131 65,004 34.5 43,661 22.8 149

Severe 101,786 49.6 8,264 4.0 1,232 72,378 38.4 4,945 2.6 1,464

Total 41,238 20.1 2,298 1.1 1,795 50,865 27.0 1,736 0.9 2,930

Total 205,012 100.0 204,395 100.0 100 188,247 100.0 191,696 100.0 98

(1) Deferral ratio for every 100 Rejections. Calculated through the relation: number of deferred / number of rejected x 100.

D

uar

te CMR

which people with chronic diseases or disabilities are subjected, in the traditional conception of the term. The prevalence of higher intensity lim-itations of regular activities is higher among the

poorer, elder, less educated and women35. As

Cav-alcante and Goldson36 emphasize, people with

disabilities are the poorest of the poor and will remain at risk of worsening poverty and subject to worse impairments unless they are the subject of public protection and social inclusion poli-cies. Thus, it is fundamental to mobilize govern-mental and non-governgovern-mental agencies, activist groups and empowered and organized families and disabled people.

Final considerations

The implementation of the biopsychosocial model for the assessment of disability was a step forward from the biological concept in force until 2009. Its adoption did not inflate the BPC grants coefficient, as the trend analysis showed. Conversely, from the viewpoint of social protec-tion, the reduced pace of grants after its adop-tion, more exacerbated when considering only non-judicial grants, evidences, as argued, the need to relax the dependency and vulnerability

assessment criteria, especially those directed to those who earn more than ¼ of minimum wage, under penalty of the policy reinforcing inequities instead of minimizing them.

The profile of applicants highlighted the vul-nerability they are subjected to, especially con-sidering the large proportion of those facing the most severe environmental barriers, underscor-ing, as discussed, the need to establish public pol-icies aimed at segments not served by the BPC.

Consistent with the design of the model implemented in 2009, the highest deferral ratio was found among those who experienced envi-ronmental barriers, limitations, restrictions and severe or complete bodily changes. All those who were considered with limitations and restrictions and non-existent or minor bodily changes had their benefit denied.

e C

ole

tiv

a,

22(11):3515-3526,

2017

Collaborations

CMR Duarte participated in all stages; MA Marcelino participated in the design, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical review and approval of the version to be published; CS Boccolini and PMM Boccolini participated in the design, methodology and approval of the version to be published.

References

1. Viana AL, Elias PE, Ibañez N, organizadores. Proteção Social. Dilemas e Desafios. São Paulo: Hucitec; 2005. 2. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social (MDS).

Proteção Social Básica [Internet]. 2017 [acessado 2017 Mar 24]. Disponível em: http://www.mds.gov.br/suas/ guia_protecao.

3. Silveira FG, Jaccoud L, Mesquita AC, Passos L, Natali-no MA. Deficiência e dependência Natali-no debate sobre a elegibilidade ao BPC [Internet]. Brasília: IPEA; 2016. (Nota Técnica). Report Nº 31. [acessado 2017 Ago 11]. Disponível em: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bit-stream/11058/7338/1/NT_n31_Disoc.pdf

4. Centro Brasileiro de Classificação de Doenças. Classifi-cação Internacional de Funcionalidade, Incapacidade e Saúde. São Paulo: Edusp - Editora da Universidade de São Paulo; 2003.

5. Brasil GF. Portal da legislação. Tratados equivalentes a Emendas Constitucionais [Internet]. [acessado 2017 Ago 11]. Disponível em: http://www4.planalto.gov.br/ legislacao/portal-legis/internacional/tratados-equiva-lentes-a-emendas-constitucionais-1

6. Maior I. Breve trajetória histórica do movimento das pessoas com deficiência [Internet] 2010; [acessado 2017 Maio 10]. Disponível em: http://violenciaedefi-ciencia.sedpcd.sp.gov.br/pdf/textosApoio/Texto2.pdf 7. Santos WR. Assistência social e deficiência no Brasil: o

reflexo do debate internacional dos direitos das pessoas com deficiência. Serv. Soc. Rev. [periódico na Internet]. 2010; 13(1):80 [acessado 2017 Ago 14]. Disponível em: http://www.uel.br/revistas/uel/index.php/ssrevista/ar-ticle/view/10440

8. Bim MCS, Murofuse NT. Benefício de Prestação Con-tinuada e perícia médica previdenciária: limitações do processo. Serv. Soc. Soc. 2014; (118):339-365.

9. Silva JLP, Diniz D. Mínimo social e igualdade : deficiên-cia, perícia e benefício assistencial na LOAS. R Katál [periódico na Internet]. 2012; 15(2):262-269. [acessa-do 2017 Ago 10]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/ pdf/rk/v15n2/11.pdf

Acknowledgments

The data on the deferral profile were produced

under the Public Policy Improvement for People

with Reduced Functionality – People with Disabili-ties and the Elderly project (TED FIOCRUZ-MDS 02/2014 and Technical-Scientific Cooperation Term FIOCRUZ-FOG 50/2015). The opinions, assumptions and conclusions or recommenda-tions expressed in this material are the responsi-bility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the MDS.

We thank Nilson do Rosário Costa for his careful review and suggestions for the text.

10. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Com-bate à Fome; Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social. Por-taria Conjunta MDS/INSS No 1, de 29 de maio de 2009. Institui instrumentos para avaliação da deficiência e do grau de incapacidade de pessoas com deficiência requerentes ao Benefício de Prestação Continuada da Assistência Social - BPC. Diário Oficial da União 2009; 01 jun e 02 jun.

11. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Com-bate à Fome; Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social. Por-taria Conjunta MDS/INSS nº 1, de 24 de maio de 2011. Estabelece os critérios, procedimentos e instrumentos para a avaliação social e médico-pericial da deficiência e do grau de incapacidade das pessoas com deficiência requerentes do Benefício de Presta. Diário Oficial da União 2011; 26 maio.

12. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Com-bate à Fome; Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social. Por-taria Conjunta INSS/MDS no 2 de 30/03/2015. Dispõe sobre critérios, procedimentos e instrumentos para a avaliação social e médica da pessoa com deficiência para acesso ao Benefício de Prestação Continuada. Diário Oficial da União 2015; 9 abr.

13. Nogueira GC, Schoeller SD, Ramos FRS, Padilha MI, Brehmer LCF, Marques AMFB. Perfil das pessoas com deficiência física e Políticas Públicas: a distância entre intenções e gestos. Cien Saude Colet [periódico na Internet]. 2016; 21(10):3131-3142. [acessado 2017 Ago 13]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/ v21n10/1413-8123-csc-21-10-3131.pdf

D

uar

te CMR

15. Silva NL. A judicialização do Benefício de Prestação Continuada da Assistência Social. Serv Soc Soc [periódi-co na Internet]. 2012; 111(jul./set.):555-575. [acessado 2017 Jun 25]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ sssoc/n111/a09.pdf

16. Coppetti CSL, Crispim MA. O Processo de judici-alização do Benefício de Prestação Continuada da Assistência Social (BPC) - 2004 a 2014. In: 39º Anais do Encontro Anual da ANPOCS 26 a 30 de outubro de 2015 [Internet]. Caxambú; 2015. Disponível em: http:// www.anpocs.com/index.php/papers-39-encontro/spg/ spg16?format=html

17. Costa NR, Marcelino MA, Duarte CMR, Uhr D. Proteção social e pessoa com deficiência no Brasil. Cien Saude Colet [periódico na Internet]. 2016; 21(10):3037-3048. [acessado 2017 Maio 13]. Disponível em: http://www. scielo.br/pdf/csc/v21n10/1413-8123-csc-21-10-3037. pdf

18. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Com-bate a Fome (MDS). Benefícios concedidos judicial-mente, quantidade e percentual sobre o total de con-cessões, por espécie, Brasil, 1996 a 2017. Brasília: MDS; 2017. [mimeo]

19. Brasil. Ministério da Previdêcia Social. Aeps Infologo. Base de dados históricos da Previdência Social [Inter-net]. [acessado 2017 Fev 10]. Disponível em: http:// www3.dataprev.gov.br/infologo/

20. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Com-bate à Fome . Boletim BPC 2015. Benefício de Prestação Continuada da Assistência Social [Internet]. Brasília, DF; 2015. [acessado 2017 Abr 13]. Disponível em: http://www.mds.gov.br

21. National Cancer Institute. Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences. Joinpoint Trend Analysis Soft-ware [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Jun 10]. Available from: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ 22. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e

Com-bate à Fome (MDS). Avaliação de pessoas com deficiên-cia para acesso ao Banefício de Prestação Continuada da Assistência Social. Um novo instrumento baseado na Classificação Internacional de Funcionalidade, Incapaci-dade e Saúde. Brasília: MDS; 2007.

23. Sampaio RF, Mancini MC, Gonçalves GGP, Bittencourt NFN, Miranda AD, Fonseca ST. Aplicação da Classifi-cação Internacional de Funcionalidade, Incapacidade e Saude (CIF) na prática clínica do fisioterapeuta. Rev. Bras. Fisioter. [periódico na Internet] 2005; 9(2):129-136 [acessado 2017 Abr 13]. Disponível em: http://files. fisioterapiafap.webnode.com/200000012-316bc3265d/ CIF%20BASES.pdf

24. United Nations (UN). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol [Inter-net]. New York: UN; 2006. [cited 2017 Jun 10]. Avail-able from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.as-p?navid=15&pid=150

25. Žganec N, Laklija M, Babic, Milic M. Access To Social Rights and Persons With Disabilities. Drus Istraz [serial on the Internet]. 2012; 21(1 (115)):59-78 [cited 2017 Jun 10]. Available from: http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php ?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=118342

26. World Report on Disability (WHO) [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 Apr 08]. Available from: http://www.who. int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf

27. Santos W. Deficiência como restrição de participação social: desafios para avaliação a partir da Lei Brasilei-ra de Inclusão. Cien Saude Colet [periódico na Inter-net] 2016; 21(10):3007-3016 [acessado 2017 Ago 12]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v21n10/ 1413-8123-csc-21-10-3007.pdf

28. Brasil. Decreto nº 6.214, de 26 de setembro de 2007. Regulamenta o benefício de prestação continuada da assistência social devido à pessoa com deficiência e ao idoso de que trata a Lei no 8.742, de 7 de dezembro de 1993, e a Lei nº 10.741, de 1º de outubro de 2003, acresce parágrafo ao art. 162 do Decreto no 3.048, de 6 de maio de 1999, e dá outras providências. Diário Ofi-cial da União 2007; 28 set.

29. Vianna ML, Teixeira W. Seguridade social e combate à pobreza no Brasil: o papel dos benefícios não con-tributivos. In: Viana ALA, Elias PEM, Ibañez N, orga-nizadores. Proteção Social: dilemas e desafios. São Paulo: Hucitec; 2005. p. 89-122.

30. Soares FV, Soares S, Medeiros M, Osório RG. Pro-gramas de transferência de renda no Brasil: impactos sobre a desigualdade [Internet]. Brasília; 2006. (Tex-tos para Discussão nº 1228) [acessado 2017 Abr 17]. Disponível em: http://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/index. php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4374 31. World Bank Group. Salvaguardas Contra a Reversão

dos Ganhos Sociais Durante a Crise Econômica no Brasil [Internet] 2017 [acessado 2017 Jun 20]. Dis-ponível em: https://nacoesunidas.org/wp-content/up-loads/2017/02/NovosPobresBrasil_Portuguese.pdf 32. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde (MS). Portaria nº 1813,

de 11 de novembro de 2015. Declara Emergência em Saúde Pública de Importância Nacional (ESPIN) por alteração no padrão de ocorrência de microcefalias no Brasil. Diário Oficial da União 2015; 12 nov.

33. Oviedo RAM, Czeresnia D. O conceito de vulnerabi-lidade e seu caráter biossocial. Interface (Botucatu) [periódico na Internet] 2015;19(53):237-250 [acessado 2017 Jun 15]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ icse/2015nahead/1807-5762-icse-1807-576220140436. pdf

34. Greek National Confederation of Disabled People. Eu-ropean Disability Forum. Disability and Social Exclu-sion in the European Union Final study report [Inter-net]. Athenas; 2002 [cited 2017 Jun 22]. Available from: http://sid.usal.es/idocs/F8/FDO7040/disability_and_ social_exclusion_report.pdf

35. Boccolini PMM, Duarte CMR, Marcelino MA, Boc-colini CS. Desigualdades sociais nas limitações causas por doenças crônicas e deficiências no Brasil:Pesqui-sa Nacional de Saúde-2013. Ciên Saúde Colet 2017; 22(11):3537-3546.

36. Cavalcante FG, Goldson E. Análise da situação da po-breza e da violência entre crianças e jovens com defi-ciência nas Américas – uma proposta de agenda. Cien Saude Colet [periódico na Internet]. 2009; 14(1):7-20 [acessado 2017 Jun 25]. Disponível em: http://www. scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413 -81232009000100003&lng=en&nrm= iso &tlng=en

Article submitted 15/05/2017 Approved 03/07/2017