Pedro Poças Reis da Silva

January 2018

Value Co-creation in Sharing Systems:

Airbnb Guests' Participation in Value

Co-creation Practices

Pedro Poças Reis da Silva

V

alue Co-creation in Sharing Sys

tems:

Airbnb Guests' Participation in Value Co-creation Practices

UMinho|2018

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Economia e Gestão

Pedro Poças Reis da Silva

January 2018

Value Co-creation in Sharing Systems:

Airbnb Guests' Participation in Value

Co-creation Practices

Supervisor

Professor Vasco Eiriz

Masters Dissertation

Master in Marketing and Strategy

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Economia e Gestão

DECLARATION

Name: Pedro Poças Reis da Silva E-mail: pedroreissilva@outlook.pt

Title of dissertation: Value Co-creation in Sharing Systems: Airbnb Guests’ Participation in Value Co-creation Practices

Supervisor:

Professor Vasco Eiriz

Conclusion year: 2018

Master in Marketing and Stategy

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA DISSERTAÇÃO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE;

University of Minho, 29/01/2018

iii

Personal Note

This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of José de Castro Poças, my godfather, whose joyful and inspiring presence has always been a warm light in the lives of his family and friends. You will always be missed.

It is my belief that organizations - people who come together in order to meet shared goals – constitute the main force driving change in the world. Today, we face the challenge of keeping up with change itself. This alarming idea that the world is changing at such a crescent pace was why I decided to pursue research in a relevant present-day topic such as the one of this dissertation.

Amidst all the possibilities that this advent of technology brings, we shouldn’t ignore this concern: These very same tools that connect us are often what keeps us further apart from each other. They don’t bond us. Bonds are nourished (co-nourished, one might say). During my young life, I’ve found no better way to nourish these bonds than with honest gratitude. From the pressure of reconciling work and study to sustaining such a life-restricting injury, this has been a long and bumpy road, often far away from those I love. Please, allow me to take this space to show my gratitude to those who made it possible for me to reach this far, for these are my co-creators:

To my supervisor, Professor Vasco Eiriz, for his continuous support, advice, critics, and encouragement, all of which were decisive for this project to meet its goals.

To Professor Joaquim Silva, from whom I first came to know about value co-creation, for providing me with interesting and critical advice over conducting research on the topic.

To the entire team of Clínica Eduardo Salgado, especially, Filipa Silva and Liliana Bastos for providing me with the proper care for me to recover and heal from my injuries.

To the entire team of EDIT VALUE®, for welcoming me as their intern. Special thanks to

Nuno Pinto Bastos and Bruna Dias for their lessons, comprehension, and support.

To my friends from CEB – Clube de Escalada de Braga, especially, Filipe “Shore” Costa for his ability to inspire people and encourage them to reach higher heights.

To my fellow colleagues, for their companionship and support.

To my family, especially my dear parents, for their loving support and always working hard to give the possibilities to develop myself and live a happier life.

v

Abstract

Value creation in Sharing Systems: Airbnb Guests’ Participation in Value Co-creation Practices

Sharing systems, i.e.,systems of economic actors who participate in a flow of exchange enabled or managed by a physical or virtual platform, have captured the interest of the industry and academia, for its disruptive innovation, growth curves, flexible supply and potential to extract value from underused resources. Given its novelty, marketing research on such systems is underwhelming. Timely, marketing researchers, have been expressing a growing interest in the active role that a consumer plays in his/her own value creation. The notion of consumer value co-creation and its ground on SD-logic has propelled researchers into a new marketing paradigm, that reveals itself to be an adequate lens to study a new breed of business models and markets such as sharing systems. This dissertation explores the marketing implications of guests participating in value co-creationfor the Airbnb system. As such, it aims at meeting the following research goals:

1. Evaluate the participation of guests in value co-creation in Airbnb experiences; 2. Evaluate the participation of guests in value co-destruction in Airbnb experiences.

We conducted an online questionnaire to Portuguese Airbnb’ guests and obtained 101 valid answers. We found that though guests participate in some value co-creation processes and practices, and to some extent, value co-destruction, participation in isolated practices/processes has an insignificant relationship with satisfaction and the likelihood of choosing a sharing system again constructs. We also found participation in co-creation to be relatively homogenous across age, gender, duration and house sharing, and found small differences among group size and travel goal. We conduct a critical analysis of our results and comparing them with existing literature for further elaboration. This study finds that single practices alone or all-encompassing processes may hold poor significance in value determination for the consumer and the firm. It also includes a practice and processes approach and suggests practices may hold more analytical power for marketers. As such, it provides the academia with suggestions and directions for conducting research on this topic. For the industry, this study informs decision makers, practitioners and entrepreneurs on the idiosyncrasies of designing, managing and promoting sharing systems with value co-creation in mind. The study endures the limitation of the infancy state of research in value co-creation (namely the lack of problem-focused developed scales), the use of a convenience sample and consumer bias.

KEY-WORDS: value co-creation, practices, value co-destruction, Airbnb, guests, sharing economy, collaborative consumption, satisfaction, marketing, service marketing, service-dominant logic, service design

vii

Resumo

Cocriação de Valor em Sistemas de Partilha: A Participação de Hóspedes do Airbnb em Práticas de Cocriação de Valor

Os sistemas de partilha, constituídos por agentes económicos que participam num fluxo de trocas permitido ou gerido por uma plataforma física ou virtual,captaram a atenção da indústria e da academia, pela sua inovação disruptiva, curvas de crescimento, fornecimento flexível e potencial para criar valor através de recursos subutilizados. Dada a sua novidade, a pesquisa de marketing em tais contextos ainda não foi devidamente explorada. Oportunamente, os investigadores de marketing têm mostrado um interesse crescente no papel ativo que o consumidor tem na sua criação de valor. A noção de cocriação de valor e a service-dominant logic (SD-logic) impulsionou os investigadores em direção a um novo paradigma de pesquisa de marketing, que se revela como uma lente apropriada para estudar este novo tipo de sistemas. Esta dissertação explora as implicações de marketing dos hóspedes participarem em cocriação de valor para os próprios e para o sistema do Airbnb. Deste modo, procura cumprir os seguintes objetivos: 1. Avaliar a participação dos hóspedes na cocriação de valor em experiências de Airbnb;

2. Avaliar a participação dos hóspedes na codestruição de valor em experiências de Airbnb.

Realizamos um questionário online a hóspedes portugueses do Airbnb e obtemos 101 respostas válidas. Descobrimos que apesar dos hóspedes participarem nos processos e práticas de cocriação que testamos, a sua participação parece ter uma relação insignificante com os construtos de satisfação e probabilidade de voltar a escolher um sistema de partilha. Descobrimos ainda que a participação é relativamente homogénea em termos de idade, género, duração, partilha de habitação, e encontramos pequenas diferenças por objetivo de viagem e tamanho de grupo. Este estudo propõe que práticas isoladas ou processos gerais de cocriação podem ter uma relação demasiado fraca para ser medida de acordo com os métodos e critérios atuais. Também inclui a abordagem de práticas e processos que podem ter mais poder analítico para praticantes de marketing. Neste seguimento, propõe sugestões e direções para elaborar investigação neste tópico. Para a indústria, este estudo informa decisores, praticantes, e empreendedores sobre as idiossincrasias de desenhar, gerir e promover sistemas de partilha tendo em conta a cocriação de valor. As limitações do estudo devem-se ao estado subdesenvolvido da investigação em cocriação, (nomeadamente, a falta de escalas desenvolvidas e testadas), o uso de uma amostra de conveniência e o enviesamento do consumidor.

PALAVRAS CHAVE:cocriação de valor, práticas, codestruição de valor, Airbnb, hóspedes, economia da partilha, consumo colaborativo, satisfação, marketing, marketing de serviços, service-dominant logic, design do serviço

ix

Index

Personal Note ...iii

Abstract ... v Resumo ... vii List of Figures ... xi List of Tables ... xi 1. Introduction ... 1 1.1 Introduction ... 1

1.2 Framing and justification for the chosen topic ... 1

1.3 Objectives and methodology... 6

1.4 Structure ... 8

2. Value Co-creation ... 11

2.1 Introduction ... 11

2.2 From value to value co-creation in marketing ... 11

2.3 Value co-creation conceptual formulation ... 13

2.4 Dimensions and measuring... 18

2.5 Value co-creation practices approach ... 20

2.6 Conclusion ... 22

3. Sharing Systems ... 23

3.1 Introduction ... 23

3.2 Defining sharing systems ... 23

3.3 Distinctive characteristics and dynamics ... 26

3.4 Conclusion ... 33

4. Research Context and Conceptual Model ... 35

4.1 Introduction ... 35

4.2 Airbnb as a sharing system ... 35

4.3 Value co-creation in Airbnb ... 39

4.4 Goals, hypothesis, and model ... 44

4.5 Conclusion ... 51

5. Methodology ... 53

5.1 Introduction ... 53

5.2 Research paradigm ... 53

5.3Methods and sampling ... 55

5.4 Questionnaire design ... 57

x

5.6 Conclusion ... 62

6. Results ... 63

6.1 Introduction ... 63

6.2 Sample ... 63

6.3 Results of value co-creation processes... 67

6.4 Results of value co-creation practices ... 69

6.5 Results of value co-destruction ... 71

6.6 Results of satisfaction with sharing option ... 74

6.7 Results of choosing a sharing option again ... 77

6.8 Conclusion ... 81

7. Discussion and Conclusion ... 83

7.1 Introduction ... 83

7.2 Participation on value co-creation and satisfaction ... 83

7.3 Participation in value co-destruction ... 88

7.4 Contributions to research ... 92

7.5 Limitations ... 93

7.6 Future research ... 94

Bibliography ... 95

Appendix I – Questionnaire (Portuguese) ... 105

Appendix II – Questionnaire (English) ... 109

Appendix III – Cross-tabulation analysis (consumer variables) ... 113

Appendix IV – Cross-tabulation analysis (experience variables) ... 117

xi

List of Figures

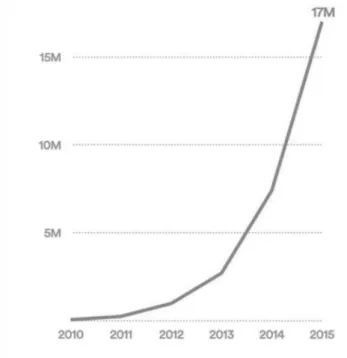

Figure 1 - Airbnb growth numbers ... 3

Figure 2 - Number of Airbnb guests over the summer ... 4

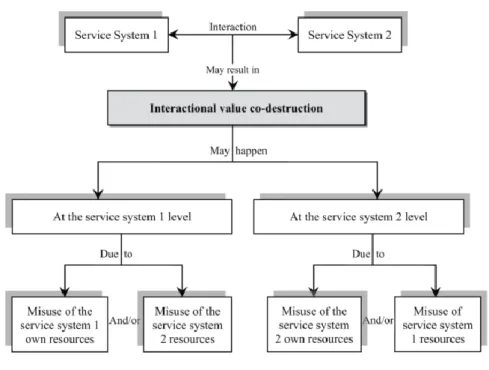

Figure 3 - Co-destruction logic ... 16

Figure 4 - Antecedents and consequences of value co-creation ... 19

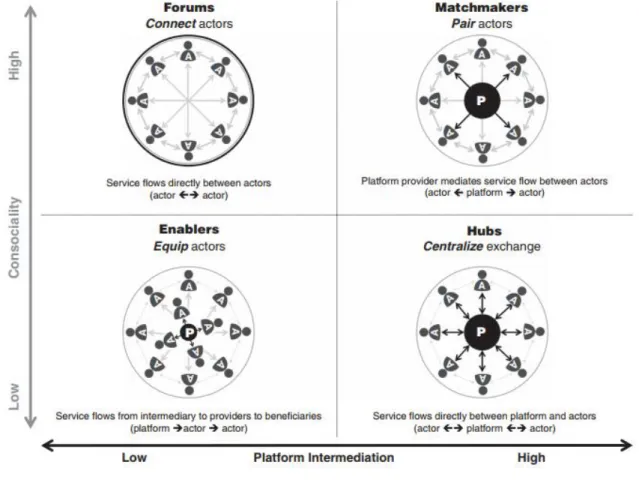

Figure 5 - Different types of sharing systems according to consociality and platform intermediation ... 28

Figure 6 - Mohlmann's model ... 31

Figure 7 - Representation of traditional goods logic versus service-domant logic formulation of Airbnb system ... 42

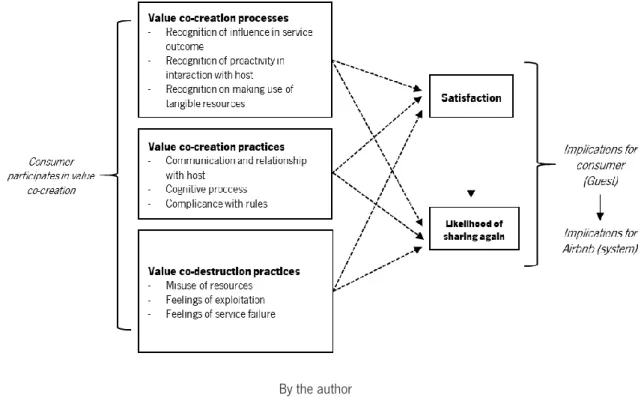

Figure 8 - Representation of the implications of value co-creation in Airbnb conceptual model ... 51

List of Tables

Table 1 - SD-logic's premises and axioms ... 14Table 2 - Gronroos and Voima’s value co-creation spheres ... 18

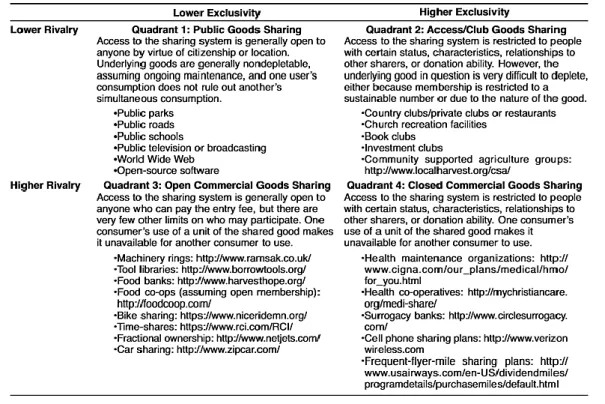

Table 3 - Types of sharing systems, according to exclusivity and rivalry ... 27

Table 4 - Summary of elements and actors in a sharing system ... 32

Table 5 - Airbnb's sharing system elements and actors ... 38

Table 7 - Research goals and hypothesis ... 48

Table 8 - Items (in English)... 59

Table 9 - Research goals, hypothesis, and tests ... 60

Table 10 - Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample ... 64

Table 11 - Last time used Airbnb ... 64

Table 12 - Number of nights... 65

Table 13 - Number of people by accommodation ... 66

Table 14 - Destinations ... 66

Table 15 - District of origin ... 67

Table 16 - Value co-creation items ... 68

Table 17 - Value co-creation processes per Gender ... 69

Table 18 - Value co-creation processes per Number of people per accommodation ... 69

Table 19 - Value co-creation practices items ... 70

Table 20 - Value co-creation practices per Number of people per accommodation ... 71

Table 21 - Value co-destruction items ... 72

Table 22 - Value co-destruction per Gender ... 73

Table 23 - Value co-destruction per Number of people per accommodation ... 73

Table 24 - Value co-destruction per Travel goal ... 73

Table 25 - Total satisfaction ... 74

Table 26 - Satisfaction with sharing option per Gender ... 74

Table 27 - Satisfaction with sharing option per Number of people per accommodation ... 75

Table 28 - Satisfaction with sharing option per Travel goal ... 75

Table 29 - Satisfaction with sharing option correlations coefficients ... 76

Table 30 - Satisfaction with sharing option items ... 77

Table 31 - Total likelihood of choosing a sharing option again ... 78

Table 32 - Choosing a sharing option again per Gender ... 78

Table 33 - Choosing a sharing option again per Number of people per accommodation... 78

Table 34 - Choosing a sharing option again per Travel goal ... 79

Table 35 - Choosing sharing option again correlations coefficients ... 79

Table 36 - Likelihood of choosing a sharing option again items ... 80

1

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduction

The goal of this chapter is to introduce the reader to the dissertation’s content. This chapter will elaborate on the background of the topic, the goals of research and the structure of the document. In section 1.2 we address the topic’s background and the framing for this research project, as well as the motivations for the topic. In section 1.3 we explain the research goals. In section 1.4 we explain how the document is structured, providing a global view of the dissertation’s content.

1.2 Framing and justification for the chosen topic

The preference for this topic was strongly motivated by the market share growth of sharing systems that was felt across multiple industries, over the last decade, which that caught the attention of researchers, firms, media reporters and government institutions (Botsman & Rogers, 2010; Cheng, 2016; EU, 2016; Lamberton & Rose, 2012; PwC, 2015). First, we take a look at how sharing systems came to be and what its impacts in the accommodation industry were.

It is a common notion among anthropologists, that the history of man and human behavior, institutions and cultures, have been heavily shaped and driven by the technological development of societies (Harari, 2014).

One of the recent most impactful developments in communication technology was the surge of the Internet in the 1980’s and its mainstream adoption in 1990’s, which strongly affected the method and speed of information dissemination, across the world (Leiner et al., 2009). The last two decades were marked by an increase in the usability and accessibility of the Internet, as network signals become broadly available at reduced costs and mobile devices began to house faster computer chips for data processing and user-friendly interfaces, allowing access to be portable and affordable (Hampton, Livio, & Sessions Goulet, 2010; Internet Society, 2015; Schrock, 2015).

2

Thanks to these advances, the monetary costs and individual effort for two people to connect with each other have become rather insignificant in developed societies. Given the low costs of operation, an online based business can now serve as an intermediary between two people without ever making physical contact with each other, or supporting costs with active employee-consumer contact, as digital platforms and servers now serve as interfaces for these processes.

When we look at the travel and accommodation market, we see a striking example of the effect that the internet had on markets that used to heavily rely on intermediaries. In 2000, Ryanair was a pioneer in allowing their passengers to book flights through an online platform, gaining control over price, and reducing costs with travel agents (Ryanair, 2018). Online search engine based-businesses like Booking.com made hotels and hostels reservation popular worldwide. Together, these events contributed to the growth of online travel and booking.

Airbnb decided to take a different approach. While other platforms had hotels or hostels (traditional accommodation offers) as suppliers, Airbnb targeted traditional homes and ordinary people as resources for their supply line. With low effort and costs, a room, a flat or a home could be transformed into an accommodation offer. As it was online-based it could be easily scaled to any city in the world.

Due to its features, Airbnb doesn’t seem to meet the ordinary label of a supplier, nor does it fit the label of a “search engine”, but is often described as an example of “sharing economy” or “collaborative consumption” (Botsman & Rogers, 2010).

Used in this context, these terms refer to businesses or organizations that share a collection of features such as the reliance on under-utilized resources, the existence of a moderator, the existence of exchanges between two distinct user groups and easy access to the system, granted by online platforms. In this dissertation, we adopt a more formal stance on the conception of this type of business as we explore it under the definition of “sharing systems” and elaborated upon it based on existing academic literature (Chapter 3).

For Credit Suisse, examples of these businesses can be found across multiple industries, including:

– “transportation (e.g. Uber, Lyft, Blablacar, Didi Kuaidi), accommodation (Airbnb, Kozaza, Couchsurfing), household services (TaskRabbit, Care.com), deliveries (Postmates, Instacart), retail commerce (eBay, Etsy, Taobao), consumer loans (Lending Club, Prosper), currency exchange (TransferWise, Currency Fair), project

3

finance (Kickstarter), computer programming (oDesk, Freelancer)” (Farronato & Levin, 2015, p. 6)

In a study contracted by the European Commission, PwC estimates that the impact of sharing systems in 2015 was 3.6 billion euros in the European Union, having surveyed the accommodation, passenger transportation, household services, professional and technical services, and collaborative finance markets (Daveiro & Vaughan, 2016; EU, 2016).

Among the examples of sharing systems, the most prominent are Airbnb and Uber, both of which have benefited from rapid growth curves, causing commotions in their respective industries. These attributes make them a major subject of interest of the academia and the industry.

Ever since its founding in 2008, Airbnb has been growing at an accelerated pace. According to the The Wall Street Journal, Airbnb has grown from making 1 million of US dollars revenue in 2009 to around 900 million of US dollars in 2015 (see Figure 1).

Adapted from Winkler (2015)

4

During 2010 and 2015, the number of summer guests on Airbnb has grown 353 times over, according to the company (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Number of Airbnb guests over the summer

Adapted from Airbnb (2015)

Airbnb growth pattern meet the definition of disruptive innovation. According to Bower and Christensen (1995), disruptive innovation is when an offers that has a different set of attributes than established offers is introduced at the lower end of a market and then relentlessly moves up, eventually displacing established competitors. According to Airbnb, 35% of the people who travel on the service say they would not have traveled or stayed as long but for Airbnb (Airbnb, 2018c).

The hospitality industry has undergone significant changes due to the entrance of sharing system-type players, like HomeAway or Couchsurfing, that much like Airbnb provide low-cost accommodation offers that have disrupted the market. The higher number of accommodation offers, now means cities have larger tourist capacity which results in benefits for tourism-related industries.

Airbnb’s disruptive effects are several. For instance, Zervas, Proserpio, and Byers, (2017) find that the introduction of Airbnb in the state of Texas has changed consumer patterns. In response to the increase in competition, traditional accommodation offers have lowered their price, which in turn has attracted tourists.

5

Across the world, the growing number of this kind of accommodation offers have caught the attention of policymakers due to possible gentrification that these services cause (McCartney, 2017; Zee, 2016) and legal authorities due to their propensity to avoid reporting incomes for taxes purposes or breaking local legislation. In this context, Airbnb has fought legal battles in cities like Barcelona (Badcock, 2016) and San Francisco (Somerville & Levine, 2017). Cities like London, Paris, New York, and Amsterdam have imposed maximum and a minimum number of renting days (Locklear, 2018).

In Portugal, the rise in the number of accommodations due to electronic platforms has pressured policymakers to submit changes to the national and local laws (Turismo de Portugal, 2017; Villalobos, 2017). Hosts in countries like Portugal and Spain have found in Airbnb as a way to recover from the economic crisis (Silva, 2015).

Given the economic, social and legal impact that this type of service has had on society, it is imperative that researchers begin to understand how individuals interact with these systems. Standing by Anderson (1983), marketing science can benefit by focusing on theoretic developments and providing contributions for society as a whole.

Consumer research is one among the many possible avenues in marketing research. However, as we dive deep into consumer research we find that consumers are by no means an easy entity to research about. The consumer is a heterogeneous and ever-changing entity that frequently engages in non-rational behaviors.

Marketing science itself has been undergoing significant developments since the 1990’s. Over the last decades, the service-dominant logic paradigm (SD-logic) has been gaining acceptance as a theoretical framework that better explains value creation in an exchange between two actors, as opposed to the traditional logic of exchange.

This paradigm asserts that value is created by the results of the actions of several actors, including the beneficiary, through the employment of skills and use of resources. In this line of research, the impact of customer’s actions and interactions with the service provider are a major subject of interest.

Considering consumers actions in service design is not new, but SD-logic paradigm provides framing for a line of research that surpasses intellectual limitations of traditional marketing logic. This way, value co-creation can inject new life into stagnant industries by providing business with a tool for innovation, through consumer actions-centered service design (Prahalad &

6

Ramaswamy, 2004; Yu & Sangiorgi, 2017). For França and Ferreira (2016) firms oriented to customers’ value co-creation will most likely achieve competitive advantage. This way, research in SD-logic and co-creation has the potential to be much beneficial for the academia and the industry. We will cover literature on value co-creation in Chapter 2.

Marketing current research priorities include deepening studies on value co-creation, namely the effects of consumers taking a more active and collaborative role in value creation. Researchers agree that consumers play a more active and collaborative role in the service process (Alves, Fernandes & Raposo, 2015) and as such, research that asks sector-related questions on this topic needs to be conducted (Anderson et al., 2013; Moeller et al., 2013).

Due to its novelty, marketing research problems on sharing systems haven’t been thoroughly studied. Hence, this research provides an opportunity to apply marketing theory of value co-creation to the study of sharing systems. This dissertation will explore the marketing implications of the active and collaborative role that consumers play in an accommodation sharing system.

Up until now, the relationship between value co-creation theory and sharing systems has only been softly alluded to, and practical studies on the topic are missing from the literature.

1.3 Objectives and methodology

We distinguish between two types of objectives in the dissertation. The general objective is the overreaching goal of the dissertation’s writing, which includes the reason why the dissertation is written on this topic. The specific objectives, we call goals of research, as they refer to the research gaps that we found in the Literature Review part of the dissertation. The goals of research establish the reason for why we conduct an empirical study. In this study, we gather data that allows the study to provide a contribution to the existing research lines that concern the topic.

The general objective of the dissertation is to demonstrate an application of value co-creation and SD-logic framing to a sharing system context. It was achieved through the elaboration of a review of the literature on relevant topics, the execution of a quantitative study of participation on value co-creation in the Airbnb, online accommodation service platform and a subsequent critical discussion.

7

The dissertation has two goals of research, which will be presented in the following paragraphs.

1. Evaluate the participation of guests in value co-creation in Airbnb experiences;

This study pans in on the concept of “participation in value co-creation” (Chan, Yim, & Lam, 2010; Echeverri & Skålén, 2011; Mccoll-kennedy, Vargo, Dagger, Sweeney, & Kasteren, 2012), which is implied to have heterogeneous and context-sensitive qualities (França & Ferreira, 2016; Grönroos, 2006; Wieland, Koskela-Huotari, & Vargo, 2016), and attempts to evaluate its value for the user and the service system.

We choose to use two interpretations of value co-creation, as practices (Silva & Simões, 2016) and as processes. We study the importance of the participation for the outcome and its variation along marketing variables.

We aim at shedding light on the implications of value co-creation opportunities for “customers’ value creation but also their future purchasing” that Gronroos and Voima (2013, p. 147) allude in their article. We evaluate the type relation of value co-creation and satisfaction (Navarro, Llinares, & Garzon, 2016; Vega-Vazquez, Ángeles Revilla-Camacho, & Cossío-Silva, 2013) in an attempt to address the value for the consumer of participating in such activities or processes. As the main drivers of choosing sharing systems are uncertain (Lamberton & Rose, 2012), we use the “likelihood of choosing a sharing option again” measure, to infer the impact of value co-creation on the sharing system. So, these results will allow us to understand whether value co-creation practices are important for an Airbnb guest and/or for the firm.

As for the Research Goal 2:

2. Evaluate the participation of guests in value co-destruction in Airbnb experiences.

This study attempts to answers the several calls that have been made to address the negative elements of consumer value co-creation (Cova & Dalli, 2009; Echeverri & Skålén, 2011; Plé & Cáceres, 2010), by including the expansive view of value co-destruction.

8

While most studies consider the impact of positive value-co-creation, value co-destruction has been largely overlooked. Value co-destruction has been thought as unavoidable, and it is important to understand its role in the value creation processes.

In this study, we attempt to evaluate the participation of consumers in value co-destruction type of activities and practices. We study whether consumers report participating or feeling the effects of these practices and its variation along marketing variables.

Like value co-creation, we also evaluate whether value co-destruction has a relationship with satisfaction or choosing a sharing option again.

1.4 Structure

This dissertation is organized into four parts, which include seven chapters. The first part is the Introduction, which consists of Chapter 1. The second part is the Literature Review, composed of Chapter 2, 3 and 4. The third part is the Empirical Study is made of Chapter 5 and 6. The final part Discussion and Conclusion, which consists of Chapter 7. Each chapter begins with a brief introductory section that informs the reader about the chapter’s goals, it’s topics and its structure. In the first chapter, Introduction, the topic, its context and the global and specific objectives are presented, alongside the dissertations structure and organization. In this section, we present the background of the topics that will be further expanded upon the Literature Review and describe goals and the structure of the dissertation.

In the Literature Review, we go over the most relevant articles published in scientific journals and explore concepts that concern the gist and background of the dissertation. In Chapter 2, Value Co-creation, we address the concept of value co-creation, its evolution, meaning and current research efforts on the topic. In Chapter 3, Sharing Systems, we explore the topic of sharing systems has a type of business with specific characteristics which has been causing significant effects on market competition, consumer pattern and regulation. It ends with Chapter 4, which acts as a bridge chapter between the Literature Review and the Methodology. In this chapter, we adopt the concepts found and developed in the Literature Review and apply to the study’s context, Airbnb.

9

In the Empirical Study, we describe the research work that was developed during the Dissertation’s timeframe. In Chapter 5, Methodology, we describe the decisions that concern the quality of data gathering, treatment, and interpretation and how the empirical study was designed. In Chapter 6, we present the present the quantitative results which serve the basis of the discussion, which takes place in the next chapter.

In the Discussion and Conclusion, which consists of Chapter 7, we argue on how the data supports the study’s hypothesis to answer the research goals, comment of the meaning of results and theorize over the possible influences of value co-creation in a sharing system. We compare the study’s results with other’s author's theories and assumptions. We also explore the study’s limitations and provide suggestions for future work on this line of research and topic.

11

2. Value Co-creation

2.1 Introduction

Chapter 2 begins the Literature Review by exploring literature on value co-creation. The goal of this chapter is to present existing value co-creation literature, select a consistent theory formulation and present instruments for measuring participation in value co-creation.

In section 2.2 we will explore the classic portrayal of value in marketing before the value co-creation concept was initially proposed. In section 2.3 we will address existing conceptions of value co-creation, mainly through the service-dominant logic research stream and discuss adjacent concepts such as co-production, value-in-use and value co-destruction. In section 2.4 we will explore existing empirical value co-creation models and frameworks. In section 2.5 we discuss value co-creation practices as a research tool. In section 2.6 we present the conclusion of the chapter.

2.2 From value to value co-creation in marketing

In order to understand value co-creation, it is important to review the historic notion of value in marketing, as the former is often conceptualized and associated with a departure or improvement over the latter’s conception (Grönroos, 2006; Gronroos & Voima, 2013; Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, 2000; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004; Ranjan & Read, 2014; Vargo & Lusch, 2004). The questions of what value is and where does it lies has been a major subject of debate throughout marketing history (Dixon, 1990; Grönroos, 2006; Rust, 1998; Vargo & Lusch, 2004).

Two streams of thought emerge when exploring the possible rationales beyond value, one being the use value and other being the exchange value (Dixon, 1990).

Per Dixon, the exchange value perspective can be traced back to economist Adam Smith who associates the concept of value with prices and wealth creation. When practitioners and researchers use this perspective, they consider that marketing “adds value” by enabling more exchanges through the rearrangement of resources, time and place. The act of “exchange” is

12

associated with the creation of value because when actors engage in an exchange each party gains something more valuable than what they give (Henry as cited in Dixon, 1990). This rationale, which is long embed in marketing terminology, very often leads to the idea that the marketing purpose ends when the exchange is concluded.

On the other hand, use value refers to the actual benefits that consumers get from the goods or service. In this perspective, the creation of value is associated with the usefulness of an offer and satisfaction of needs. So, through this rationale, the role of marketing is to provide and improve offers that provide satisfaction and usefulness to the consumer. For Grönroos (2006), use value appears to be the dominant view of marketing research today.

While both perspectives on the meaning value may seem applicable to different contexts, this discussion has implications for the rather, more meaningful, measurement of value. When using exchange value logic, value can be measured by the value-in-exchange (the amount of money that the customer paid for an offer), or value-added measures (the amount of money that the company earns with a product). By the use value perspective, end-user properties such as needs, expectation, satisfaction, and utility are the elements that need to be measured to determine the value creation of an offer.

As the researchers focus swift from the exchange to the use value perspective, a link between satisfaction and worth of mouth was found (Anderson, 1998), which added to the merit and worth of using use value attributes in firms.

The discussion of value in marketing was reignited when the value co-creation notion was first proposed. The original ideas for the concept were first introduced in Prahalad and Ramaswamy's (2000) article, which include the realization that companies, buyers, suppliers no longer play fixed roles, the idea that competence for companies can be sourced from the customer and, the comment that, internet customer communities exert significant influence on the market.

While the article’s ideas and contributions are later followed by additional papers, no conceptual scheme was introduced at the time that justified a different treatment for this notion of value co-creation, something that we later find in the service-dominant logic research line.

This first notion of value co-creation led to a follow up by researchers that provide a much broader and fuller understanding of a paradigm shift in marketing logic and what it can mean for the industry (Gronroos & Voima, 2013; Ranjan & Read, 2014; Vargo & Lusch, 2004), both of which are addressed in the following section.

13

2.3 Value co-creation conceptual formulation

The most significant mark in the development of the value co-creation concept comes in the form of the proposal of service-dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004), which is credited as one of the most influential articles concerning value-co-creation (Alves et al., 2015; Ballantyne, Williams, & Aitken, 2011; Galvagno, Dalli, & Galvagno, 2014; Grönroos, 2006; Laamanen & Skalén, 2015; Ranjan & Read, 2014).

Vargo and Lusch (2004) propose what is known as service-dominant logic (SD-logic), an overarching marketing and business paradigm that proposes a new perspective on marketing. Since his inception, SD-logic has been the subject of a continuing debate (Grönroos, 2006; Leroy, Cova, & Salle, 2013; Lusch & Vargo, 2011; Vargo & Lusch, 2008, 2015).

In SD-logic, “service provision rather than goods is fundamental to economic exchange”. This logic directly opposes the “traditional goods-centered dominant logic” (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, p. 7), in several key points, such as the unit of exchange, the role of goods and customer, the meaning of value and firm interaction. SD-logic can be applied not only to marketing but also to value networks and constellations (Vargo & Lusch, 2008).

In conventional goods logics, the service is reduced to a mere complement of the product and doesn’t take in consideration customer’s actions as a source of value (the “passive customer”). In light of Vargo and Lusch’s work, the service is seen as an inclusive concept that includes any kind of commercial offers, and is defined “as the application of specialized competencies (knowledge and skills) through deeds, processes, and performances for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself” (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, p. 2). Also, the consumer’s role is stated to be as “a value cocreator of the service” and “value is perceived and determined by the consumer on the basis of ‘value in use’ (p. 7).

SD-logic was initially laid out in eight assumptions, which they call fundamental premises (FP). Later, Vargo & Lusch, (2015; 2008) update their premises formulation. Their fundamental premises, as of 2015, are presented in Table 1.

14

Table 1 – SD-logic's premises and axioms

Premises Description

FP1* Service is the fundamental basis of exchange (Axiom 1) FP2 Indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of

Exchange

FP3 Goods are a distribution mechanism for service provision

FP4 Operant resources are the fundamental source of strategic benefit FP5 All economies are service economies

FP6* Value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary (Axiom 2) FP7 Actors cannot deliver value but can participate in the creation and offering of value

propositions

FP8 A service-centered view is inherently beneficiary oriented and relational FP9* All social and economic actors are resource integrators (axiom 3) FP10* Value is always uniquely and phenomenological determined

by the beneficiary (Axiom 4)

FP11* Value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements (Axiom 5)

* The premixes marked with (*) were later renamed axioms in 2015

Adapted from (Vargo & Lusch, 2015)

For a better understanding of the context in which value is co-created, we will identify three points of the premises, that directly or indirectly provide a further conceptualization of value-co creation following SD-logic formulation:

i) A company provides a service in exchange for a service of the customer (FP1). This implies that while the customers’ employs “specialized skills and knowledge” (Vargo & Lusch, 2008, p. 6) to the benefit of both the customer and firm, the customer also does the same for his benefit and that of the firm. FP2 describes that means of how this is achieved: Goods and money exchange can be considered a service delivery.

ii) Goods have value following value-in-use logics (FP3). This implies that the value that any offer or good has is subjectively determined by the customer (FP10). While never extensively

15

explored in SD-logic, measures such as utility and satisfaction have been related to value co-creation (Ranjan & Read, 2014).

iii) Through FP6 the authors meant that the “beneficiary is always a party to its own value creation” (Vargo & Lusch, 2015, p. 9) but also simultaneous as a multi-actor phenomenon. Across the SD-logic formulation of Vargo and Lusch work, this appears to be the consistent definition of value co-creation: the characterization of value-creation as a multi-actor phenomenon, where the beneficiary and the service provider are both responsible for each and the other’s value-creation (Vargo & Lusch, 2015).

This formulation, implies that value creation (the use perspective) by the customer is both influenced by the customer interaction with the firm, and the customer’s own specialized skills and knowledge, which is also validated by Gronroos and Ravald, 2011: “Value for customers means that after they have been assisted by a self-service process (cooking a meal or withdrawing cash from an ATM) or a full-service process (eating out at a restaurant or withdrawing cash over the counter in a bank) they are or feel better off than before” and Grönroos (2006), who states while the firm’s role is to make resources available for money, and customers can also be sole-creators of value, as they use resources in a way that creates value for them.

So, where the “use value” notion asserts focus on the consumer benefits of the service/product, value-co-creation asserts its focus on the idea that the value determination is heavily affected by the actions/skills/mental state/resources of the beneficiary (and other actors involved in the exchange), expanding beyond previous notions of value, which were limited to characterizing value as a way of measuring the performance of a single party.

The main point of discussion of value co-creation was whether it was a phenomenon that was exclusive to some contexts (Gronroos & Voima, 2013), as in specific activities or processes or that customers are value co-creators by default (Vargo & Lusch, 2015, p. 9).

For Gronroos & Voima, (2013) value co-creation occurs during a direct interaction between a consumer and a provider, and that the firm’s role is to facilitate value creation, criticizing the view that value co-creation is “an all-encompassing process (…) which leads to the conclusion that everything is value creation and everyone co-creates value”(p. 144). In Vargo and Lusch 2015’s article, they consider that value is not individual nor dyadic but determined by a wide range of actors.

16

While most literature describes positive value co-creation there is a surprising lack of attention to the idea that value co-creation can also explain negative outcomes (Cova & Dalli, 2009; Gronroos & Ravald, 2011; Plé & Cáceres, 2010).

For Cova & Dalli (2009) applying some forms of what would appear to be value co-creation practices can lead to service providers transferring work for the customer that would otherwise be done by the company. This can be perceived as “exploiting the customer” to do some task of a service he is paying for, without receiving any benefit.

From Plé and Cáceres (2010)

For Plé and Cáceres (2010), value co-destruction for at least one of the parties occurs when one party fails to integrate or apply resources in a manner that is appropriate and expected by the party (see Figure 3). Gronroos and Ravald, (2011) provide a practical example of this: “if a good does not work, the value-creating process makes the customer worse off rather than better off” (p. 18).

Reflection on SD-logic is not complete without acknowledging its critics. As the SD-logic framing is assumed as being open-sourced (Lusch & Vargo, 2011; Vargo & Lusch, 2008), many authors have provided contributions by expanding and debating each other’s concepts, very often causing ambiguity and equivocal remarks (Ranjan & Read, 2014).

17

Ballantyne et al. (2011) remark that while SD-logic doesn’t bring anything new to the table, it provides “a new pattern of ideas for our times, based in part on antecedent concepts drawn from earlier scholars and from many disciplines.”.

Perhaps the most important aspects of SD-logic are its adaptable and compatible nature with other research streams and disciplines, as it doesn’t deny or rejects previous research, and tries to build upon it. Combining complementary approaches in applied research can be of benefit for research on value co-creation, (Kuppelwieser & Finsterwalder, 2016; Mccoll-kennedy, et al, 2012). The many-to-many marketing perspective, the post-modern marketing perspective, (Alves et al., 2015) consumer culture theory (Vargo & Lusch, 2008), practice theory (Vargo & Lusch, 2015) offer complementary approaches that put emphasis and develop other aspects of value-co-creation.

In fact, in their recent update to SD-logic formulation (Vargo & Lusch, 2015), the authors have drawn insight and addressed feedback and criticism in order to provide a more positive lens to the theory that can be applied to a larger range of contexts outside marketing and Business Sciences.

Given the different angles of value co-creation, as an effort to improve clarity and avoid redundancy, we will present the definitions of value co-creation -related terms that are used in this study:

i. Value co-creation refers to the notion that multiple actors (including the customer, but also others like other consumers) influence the value (in the value in use perspective) of an offer;

ii. Consumer value co-creation refers to when the customer actions, mindset or skill’ influence (negatively and positively) the value creation of the offer;

iii. Value co-creation practices, to be expanded upon in section 2.5, refer to the specific actions and interactions, physical or mental, that the consumer takes that results in consumer value co-creation.

In the following section, we will expand on how these occurrences can be studied, by examining existence research on dimensions and measuring.

18

2.4 Dimensions and measuring

As we begin to explore conceptual theorization on value co-creation we came across different directions of conceptualization and research.

One of the main points from which research tends to diverge is treating as value co-creation as an “all-encompassing process (…) which leads to the conclusion that everything is value creation and everyone co-creates value”, which Gronroos and Voima, (2013) criticize as being of less analytical use.

The other option is restricting where value co-creation opportunities exist and where the locus of value creation exists. This is spheres approach, in which three “areas” of service experience and interaction should subject to evaluation (Gronroos & Ravald, 2011; Gronroos & Voima, 2013): a provider sphere, where the opportunity for value creation is created by the service provider, including planning and designing the service to allow for customer collaboration; a joint sphere where the service provider and the customer interact in joint value creation; and, a consumer sphere, where the customer, without interacting with the service provider creates value (see Fig. 2).

From Gronroos and Voima (2013)

Similarly, Ranjan and Read’s (2014) study offers a key investigation into the antecedents and consequences of the value co-creation and of the first scale proposes on the concept. They found that authors conceptualize two dimensions of value-creation in their studies: value

19

production and value-in-use. In this sense, the value-in-use term is used to describe value co-creation during consumption or usage of an offer, differing from Dixon’s value-in-use notion. So, we found this study’s notion of value-in-use to match our definition of consumer value co-creation.

Figure 4 - Antecedents and consequences of value co-creation

Adapted from Ranjan and Read (2014)

Value co-production refers to actions that involve both the firm and the customer (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). Co-production can be broken down into three constructs: (1) equity -empowering customers and enabling joint actions for co-creation and sharing control over resources; (2) interaction - interaction and synchronous engagement is a source of value, an enabler of social practices, and allows for feedback and involvement; and (3) knowledge (sharing) - a flow of information, inventiveness, knowledge, ideas, and creativity that lead to a higher value creation as compared to what would be achieved by working independently.

20

Gronroos and Ravald’s (2011) notion of value-in-use is that “value for customers is created during use of resources” (p. 8). Ranjan and Read, (2014) break down the value-in-use concept in three constructs: experience, relationship, and personalization. The value-in-use stream matches the consumer sphere matches value-in-use.

Context appears as a significant aspect of value co-creation. For Grönroos (2006), context is a governing factor when deciding which marketing logic to use.

For Chandler and Vargo (2011) customer value co-creation efforts are a function of its simultaneous embeddedness within complex networks and service ecosystems.

The roles that the customer takes differ across types of service offerings. The customer’s proneness to perform activities with or without the service provider is a key characteristic variable when analyzing business in the context of co-creation (Moeller et al., 2013).

From the firm point of view, while most theoretical studies focus on the benefits of understanding value co-creation, none seem to refer to the implications of business that rely on it, versus others who don’t, when choosing to buy between substitutable offers. França and Ferreira (2016) suggest that firms oriented to customers’ value co-creation will most likely achieve competitive advantage.

Efforts to expand the value co-creation lexicon and conceptual boundaries are still ongoing, as Vargo and Lusch (2015) further propose additional concepts, a notion of institutions. However, we don’t find additional frameworks that in a significant way contribute to the analytical merit of value co-creation.

While we have taken notice of a shy effort on developing scales, research on value co-creation is still in an early stage. On the other hand, researchers have found success by conducting qualitative research that focuses on context-sensitive actions that the consumer participates in. We look into existing examples these studies in the following section.

2.5 Value co-creation practices approach

Due to the ongoing discussing surrounding value co-creation conceptual formulation, few studies have provided empirical research on the topic. Remarkable examples of such studies include

21

Mccoll-kennedy et al. (2012); Echeverri and Skålén (2011); and Salomonson, Åberg, and Allwood (2012).

Across different contexts, a common approach these studies take is to identify and labels sets of practical activities and actions, which are thought to be essential for consumer value co-creation (Silva & Simões, 2016; Vargo & Lusch, 2015; Vargo, Wieland, & Akaka, 2015). In this sense, value co-creation practices approach stands out as one of the most suitable for an empirical study on value co-creation in a specific context.

Silva and Simões (2016) define practices as:

“interconnected set of more or less routinized actions and interactions performed by customers-practitioners with materials and service systems, understood as resources, that are manifested by bodily and mental activities, which carry, apply and integrate know-how, resources and images, and are oriented to life goals” (Silva & Simões, 2016)

Consistent with the previous definition, example of these activities, which have been employed by existing studies, include: cooperating, collating information, colearning, connecting, combining complementary solutions [adapted], cerebral activities, coproduction activities (Mccoll-kennedy et al., 2012); informing, welcoming, charging, delivering, and helping (Echeverri & Skålén, 2011); communication, understanding, agreement, customer-employee interaction (Salomonson et al., 2012)

While Mccoll-kennedy et al. (2012) and Echeverri and Skålén (2011) directly study the consumer, Salomonson et al. (2012) zoom in on a specific value co-creation practice, which is employee-customer communication. However, unlike the previous two, the latter focus on the service provider side. Regarding the customer, they find that they co-created value by expressing, reacting and communicating with the employee on an interaction level.

Regarding the problem of value co-creation literature being underdeveloped, Echeverri & Skålén (2011) draw insights from practical studies in their study. While Mccoll-kennedy et al. (2012) suggest that their framework (“practice styles”) can be applied to other sectors.

This concludes the literature review on the topic of value co-creation. Additional articles that specifically concern the goals of research, hypothesis, and context are elaborated upon in Chapter 4.

22

2.6 Conclusion

This chapter provides an overview of the literature about the value co-creation research and its applicability. We conclude that value co-creation theory, while in an early stage of development, holds potential to reshape both the industry and marketing research. While SD-logic lenses and its different dimensions provide growing contributions for understanding the surrounding conceptual environment of value co-creation, the lack of o substantial number of empirical studies on the topic, impose a limit on transferability of any kind of empirical study. It’s important to distinguish between the value co-creation notion, which it’s understood as the notion that multiple actors influence the “use” value of an offer, and consumer value co-creation, which refers to when the customer actions, mindset or skill’ influence (negatively and positively) the value creation of the offer. Another important take is the distinction between value co-creation as processes and value co-creation as practices that divides researchers. In the following chapter, we will review literature on sharing systems.

23

3. Sharing Systems

3.1 Introduction

Chapter 3 explores existing academic literature on sharing systems as an important area of research that concerns the academia, the industry, and governing institutions. The goal of this chapter is to explain sharing systems, defining the phenomena and its boundaries, identify its characteristics and present literature contributes to formulating the context of research.

Section 3.2 describes several conceptualizations of a sharing system in order to reach a stricto sensu definition to be used for the rest of the study. Section 3.3 describes types of sharing systems, its characteristics, its different actors, and its dynamic, according to the main relevant studies on the topic. Section 3.4 presents the main conclusions of the chapter.

3.2 Defining sharing systems

Researchers have yet to reach a general, consensual conceptual definition of what we refer to in this dissertation as sharing systems (Perren & Kozinets, 2018). The phenomena has been referred to most popularly as “collaborative consumption” and “sharing economy” (Belk, 2014; Botsman & Rogers, 2010), but also as “access based consumption” (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012), “commercial sharing systems” (Lamberton & Rose, 2012), “collaborative economy” (EU, 2016) and more recently, “lateral exchange markets” (Perren & Kozinets, 2018).

In 2016, the European Union defined “collaborative economy” as “business models where activities are facilitated by collaborative platforms that create an open marketplace for the temporary use of goods or services often provided by private individuals” (EU, 2016, p. 3).

Belk (2014) defines “collaborative consumption” as “people coordinating the acquisition and distribution of a resource for a fee or other compensation”. He explains that “by including other compensation, the definition also encompasses bartering, trading, and swapping, which involve giving and receiving non-monetary compensation”. Alternatively, Benoit, Baker, Bolton, Gruber, & Kandampully (2017), define collaborative consumption as a “market-based relationship

24

between a platform, a peer service provider, and customers in which no ownership transfer happens”.

Lamberton and Rose (2012), conceptualize “commercial sharing systems” as a “marketer-managed systems that provide customers with the opportunity to enjoy product benefits without ownership”.

Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012), define access-based consumption as “transactions that may be market-mediated in which no transfer of ownership takes place”.

Perren and Kozinets (2018), prefer the conception of “lateral exchange market”, which they define as “a market formed through an intermediating technology platform that facilitates exchange activities among a network of equivalently positioned economic actors“.

Very often, authors describe sharing system as a categorical type of businesses, of which Airbnb and Uber are prominently used as examples. Other times, authors allude to an image of a new transformative or semi-transformative paradigm in markets named “sharing economy”, “collaborative economy” and “access economy”. We understand this conflictual use of the terms as different perspectives, that rely on different scales of observation (Desjeux, 1996). For clearance, we understand the first to the be the object of research this research project intends to study, while the latter refers to macro circumstances that, though taken in consideration, aren’t the focal point of the theories and assumptions we review in the chapter.

The definitions of the authors we reviewed present different takes on the same social phenomena but tend to highlight the importance of certain elements of the systems they conceptualize. According to Scaraboto (2015), the multiple terms and definitions can also correspond to different forms of collaboration, that follow overlapping logics. This creates a contrast with traditional consumption where producers and consumers have a clearly defined role and the process is the exchange of a good for a monetary fee.

Given the hazy conceptual definition, the boundaries of the concept often seem vague and imprecise, especially when we attempt to compile the existent literature into one consistent conception. For this reason, we find it important to define what we consider a sharing system to be.

In this study, sharing systems is a formulation of a group of business/organization and its users, which we define as systems of economic actors who participate in a flow of exchange enabled or managed by a physical or virtual platform. In this definition we included the idea that

25

technological platforms or an intermediator (Benoit et al., 2017; EU, 2016; Perren & Kozinets, 2018) are required for sharing systems and that the platform’s role is to enable and moderate the flow of exchange between user groups who willingly participate in the system. The flow of exchange encompasses both the notion resources sharing (Belk, 2011) and access to resources (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012), but may also include other forms of exchange like trading.

Our notion of sharing systems refers to a conceptualization of a system constituted by multiple elements, which include a moderator, economic actors, dynamics, and rules, whose idiosyncrasies are explored in the following section.

We opt to use “sharing system” throughout the dissertation for two reasons. First, the word system is frequently used in scientific research to describes a limited set of interacting actors and elements that are more or less defined. Sharing appears frequently throughout literature as a term that alludes to the variety of forms of exchanges that users in the systems may engage in. Secondly, the preference to use this term comes from the fact that it doesn’t appear to be associated with any political agenda or movement, neither does it insinuates unproven transformative paradigms, both of which we would like to avoid for the sake of reducing bias in the research.

After establishing this definition, we find it necessary to distinguish between value co-creation and sharing systems due to semantic similarities (namely, the notion of cooperation and collaboration between actors present in value co-creation and sharing systems) and similar associations (namely, both are associated with a “break-away” type of logic from the rationale governing “conventional” economic thought).

While Belk, (2014) briefly associates value co-creation and sharing systems, it seems evident that the two are not the same:

- Where SD-logic tries to be seen as a “lens through which to look at social and economic exchange phenomena so they can potentially be seen more clearly” (Vargo & Lusch, 2008, p. 9), sharing systems aims to evoke an image of a category of specific business models which share some commonalities, like Airbnb and Uber (Botsman & Rogers, 2010).

- While practices and opportunities of value co-creation can be present in multiple contexts, sharing systems is, inevitably, one among those contexts. For Grönroos (2006) the service logic fits better the context of most companies’ offer’s today. Keeping this notion in mind, we are prone to find similarities because SD-logic is an

26

adequate framing to examine value creation in the context of sharing systems, given their focus on how rethinking the exchange process between economic actors. In this argument, SD-logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2015) is capable of comprehensively describing the logic of value creation, the unique exchange mechanism, and the roles that actors take in the context of sharing systems. The argument of how SD-logic provides a proper explanation of the dynamics of exchange and value creation in sharing system as is expanded in Chapter 4, using the case of Airbnb.

In the following section, we will expand upon the characteristics and dynamics that are a staple of sharing systems, according to existent studies.

3.3 Distinctive characteristics and dynamics

Sharing systems became possible as the broad access to the Internet created networks and resource pools that are easily and widely reachable for consumption (Botsman & Rogers, 2010). In fact, almost every article, book or chapter we reviewed implicitly or explicitly denotes the importance of the Internet for sharing systems to exists. While sharing and collaboration used to be types of exchanges exclusively carried out personally and locally, now it has become a larger, global, phenomenon which has been recognized as a driving force behind fast-growing ventures whose business models promote digitally enabled transactions between individuals (Belk, 2014, p. 1596).

In sharing systems, access to the good replaces ownership of the good as the unit of exchange (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Belk, 2014; Botsman & Rogers, 2010). From this perspective, we find that this framing of access is compatible with SD-logic’s premise of service being the unit of exchange. In this case, providing access is seen as a service.

A sharing system is composed of different actors and elements. The European Union classifies three kinds of actors in sharing systems:

(i) service providers who share assets, resources, time and/or skills — these can be private individuals offering services on an occasional basis (‘peers’) or service providers acting in their professional capacity ("professional services providers"); (ii)

27

users of these; and (iii) intermediaries that connect — via an online platform — providers with users and that facilitate transactions between them. (EU, 2016, p. 3) Researchers have taken note of the similarities but also of the variabilities across sharing systems. Lamberton and Rose (2012), propose different types of sharing systems (see Table 3) by drawing upon concepts from the public goods literature to classify different types of shared offers on the basis of consumer rivalry and exclusivity.

Rivalry refers to the amount that consumers compete against consumers for a limited supply of the shared product. Exclusivity is the degree to which access to the product can be controlled and restricted to the consumers.

Table 3 – Types of sharing systems, according to exclusivity and rivalry

From Lamberton and Rose (2012)

Lamberton and Rose’s interpretation of sharing system is a more broad one, as it also includes public goods or services (Q1). However, the remaining quadrants all seem descriptive of what its expected is our notion of sharing systems (especially Q2 and Q3).

28

Like in Lambert and Rose’s formulation, we expect to exist rivalry in the system due to limited resources and therefore, we also expect some degree of exclusivity. Consistent with this reasoning, sharing systems are found to need rules and a governing system, as people can behave negatively when no rules are enforced (Hartl, Hofmann, & Kirchler, 2015).

We find Perren and Kozinets (2018, pp. 26-27) classification of sharing systems to be more helpful, as its focus is on the different types of interaction between economic actors. They classify four types of sharing systems according to the criteria of “consociality” and platform intermediation.

Consociality refers to the “physical and/or virtual copresence of social actors in a network, which provides an opportunity for social interaction between them”, as defined by Perren and Kozinets (2018, p. 23). Platform intermediation refers to the use of a software platform through which an intermediary manages and coordinates the exchange between connected actors, aiming at incentivizing trustworthy behavior.

Figure 5 - Different types of sharing systems according to consociality and platform intermediation

29

The four types are forums (e.g. Craigslist), matchmakers (e.g. Airbnb, Uber), enablers (e.g. Kickstarter, eBay) and hubs (e.g. Lending Club), which are defined and illustrated as seen in Figure 5.

A particularity with sharing systems is that the actors can play a wide range of roles and engage in different types of exchanges: commercial exchange, gift-giving,intracommunity giving, sharing, donationware and creative commons (Scaraboto, 2015). In the same way, they can even switch roles.

Providers monetizing access to assets that are underutilized have become a primary characteristic of sharing systems (Cusumano, 2015). While economical gain has been thought as the primary motivation behind sharing systems (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; 2015) due to enabling the use of underutilized assets, sharing systems have also been a subject interest from an ecological perspective (Cheng, 2016; Hamari, Sjöklint, & Ukkonen, 2016), because it may enable contributions to solve issues related to the “tragedy of the commons” (Hardin, 1968) that refer to resource-scarcity.

Sharing systems are usually mentioned as an example of innovation. In fact, most sharing systems tend to follow some aspect of Innovation type at the market level, as most technological platforms (e.g. Airbnb, Uber, Cabify) can be considered as product/marketing innovation, per Oslo’s Manual definitions (OECD, 2005). As most platforms enable a new kind of access to the offers, it meets Oslo’s manual definitions of process innovation, a new or significantly improved production or delivery method, as users can access and supply resources through online inputs. At the same time, the can also, cumulative be labeled as a marketing innovation, as the online platform nature of the system, opens the opportunity for the creation of algorithms of searching, matching, pricing, and promotion, that brings significantly improved changes to the market. Of course, the success of these innovation depends on the case.

For Zervas et al. (2017), the success of sharing systems can be attributed not only to technological innovation but also to the flexible supply of the users who own resources. This flexible supply line allows them to get in and out of the platform with only a few inputs in the platform, bearing no consequences to the business relationship with the platform.

The relatively easy access by the consumers and providers is deemed as a defining characteristic of sharing systems. Bardhi and (2012; 2015) argue that the success of these